Abstract

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of global mortality, with lung, colon, skin, and breast cancers contributing significantly to the disease burden. Accurate and timely classification of histopathological images is critical for effective diagnosis and treatment planning. However, existing deep learning models for histopathology often achieve strong results but remain limited to single-cancer classification, lack generalizability across datasets, and provide little transparency for clinical use. To address these gaps, we propose CancerDet-Net, a comprehensive unified framework capable of classifying nine histopathological subtypes across four major cancer types. CancerDet-Net integrates separable convolutional layers, Vision Transformer (ViT) blocks with local-window sparse self-attention, and a Hierarchical Multi-Scale Gated Attention Mechanism (HMSGA), combined through Cross-Scale Feature (CSF) Fusion. Unlike prior approaches, our model not only achieves top-performing accuracy (98.51%) but also incorporates explainable AI (XAI) visualizations and is deployed via both a web-based platform and Android app for real-time clinical use. This combination of multi-cancer generalization, interpretability, and deployment readiness establishes CancerDet-Net as a distinctive contribution to AI-driven digital pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, with nearly 10 million deaths reported in 2020 alone, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)1. Histopathological image analysis remains the gold standard for diagnosis, as it allows pathologists to examine cellular and tissue structures in detail2. Despite its importance, this process is manual, time-consuming, and dependent on expert interpretation, which creates bottlenecks in both resource-rich and resource-limited healthcare settings. These challenges highlight the need for automated, scalable systems that can assist in reliable and timely cancer diagnosis.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning (DL), have transformed medical image analysis. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and other architectures have shown strong performance in classifying histopathological images for specific cancer types such as breast, lung, skin, and colon3,4,5,6,7,8. However, existing models typically focus on a single cancer type, which restricts their applicability in real-world clinical workflows where diverse cancer subtypes must be identified simultaneously. Furthermore, many of these approaches struggle to generalize across variations in tissue morphology and staining conditions, leading to inconsistent results. Another persistent limitation is the lack of interpretability: most DL models function as “black boxes,” providing predictions without sufficient explanations, which reduces clinical trust9. These shortcomings underscore three critical research gaps: (i) the absence of a unified multi-cancer framework, (ii) limited interpretability of current models, and (iii) insufficient progress toward real-world deployment.

To address these gaps, the key contributions of this work are: we propose CancerDet-Net, a unified DL model that simultaneously classifies four major cancer types (skin, breast, lung, colon) across nine histopathological subtypes. The architecture combines several innovations—a module, ViT blocks with local-window sparse self-attention, and a CSF fusion mechanism—to capture both fine-grained cellular details and global tissue context. We also integrate XAI techniques (LIME and Grad-CAM) to provide visual rationales for the model’s predictions, enhancing clinical trust. Finally, we deploy CancerDet-Net via a web interface and an Android application for real-time, accessible use in diverse clinical settings.

Literature review

DL has significantly advanced cancer histopathology classification, with studies employing CNNs, hybrid models, transformers, and ensemble strategies to improve diagnostic accuracy10,11,12,13. While many approaches report high performance on specific datasets, challenges remain overfitting, reliance on small or imbalanced datasets, limited generalizability across multiple cancer types, and lack of interpretability14. Many works also focus on binary or single-class tasks, limiting clinical applicability, though recent research has begun to explore multi-class and multi-cancer frameworks15,16.

Ensemble-based strategies have shown promise. Differential-evolution-optimized CNN ensembles have boosted brain tumour detection17, Cervi-Net improved cervical cancer classification18, and ensemble pipelines enhanced diabetic retinopathy diagnosis19. Multimodal integration has also emerged, such as combining radiology, histopathology, and genomics for ccRCC prognosis20. Lightweight designs, including ShallowMRI21 and FOLC-Net22, address efficiency and adaptability while maintaining accuracy.

Transformer-based histopathology methods such as CLAM, TransMIL, and Gigapath23,24 achieve strong performance at whole-slide or multiple-instance levels, but they require massive datasets and high computational cost, and focus less on fine-grained local features. In contrast, CancerDet-Net operates at the patch level, coupling with local-window ViT blocks to capture both lesion details and contextual structure in a computationally efficient and interpretable manner.

To illustrate the research landscape, Table 1 summarizes recent classification studies organized by dataset. It highlights methods, achieved accuracy, and noted limitations across datasets such as WBCD25,26, IDC + BreaKHis27, ISIC31,32,33,34,35,36,37, LC2500038,39,40,41,42, IQ-OTH/NCCD43,44,45, Colon46,47,48, and Lung49,50,51,52,53. Existing models often remain dataset-specific, lack multi-scale fusion, or act as black-boxes with limited interpretability. CancerDet-Net advances beyond these by combining HMSGA and transformer modules with cross-scale fusion into a unified framework that supports robust multi-cancer classification and real-world deployment via web and mobile platforms.

Proposed methodology

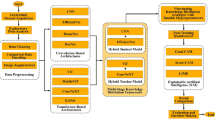

The abstract visualization of the experimental process used in this study for multi-cancer classification using histopathological images is illustrated in Fig. 1. The study begins with the acquisition of histopathological images spanning four major cancer types (lung, colon, skin, and breast) drawn from multiple publicly available datasets. All images undergo standard pre-processing, including normalization, resizing, and augmentation, to ensure uniform quality and improve generalization. The processed images are then fed into CancerDet-Net, a unified framework that integrates separable CNN layers, HMSGA, and local-window ViT blocks to extract both fine-grained and contextual features. To enhance interpretability, predictions are further analyzed with LIME54 and Grad-CAM55, providing visual explanations of the model’s decision-making. Performance is evaluated across datasets using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, enabling a comprehensive assessment of robustness and generalizability.

Datasets description and pre-processing

In this study, four major cancer types: skin, lung, colon, and breast were analyzed using three publicly available histopathological image datasets. The LC25000 dataset56 provides high-resolution images of lung and colon cancers alongside benign tissue, offering clean labeling and consistency for machine learning tasks. The ISIC 2019 dataset57, curated by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration, contains dermatoscopic images across nine diagnostic categories and serves as a global benchmark for skin cancer detection. The BreakHis dataset58, released by P&D Laboratory in Brazil, includes breast cancer microscopy images with binary and multiclass annotations. To ensure uniform model input, all images were rescaled and normalized before training. Each dataset followed its standard training-validation protocol. In this study, each dataset (LC25000, ISIC 2019, and BreakHis) was first evaluated independently, and then two customized multi-cancer datasets (7-class and 9-class) were constructed to test the model’s generalizability. Thus, results are reported both for individual datasets and for the unified multi-cancer setting, ensuring clarity in the evaluation protocol. Dataset characteristics are summarized in Table 2, and Fig. 2 represents sample images from the cancer dataset. In addition to evaluating each dataset independently, we created two merged datasets to simulate a multi-cancer scenario: a 7-class dataset (lung, colon, skin cancers) and a 9-class dataset (lung, colon, skin, and breast cancers). These combined datasets allowed us to test CancerDet-Net’s ability to handle multiple cancer types simultaneously. The class composition of these merged sets is outlined in Table 3.

All histopathological images were pre-processed to ensure consistency and optimize learning. The pipeline included resizing to 128 × 128 pixels, normalizing pixel values to the range (0–1), and splitting the data into training, validation, and testing sets at a 75–15–10% ratio. Class distributions were balanced in LC25000, ISIC-2019, and the merged Nine-Cancer dataset, while BreakHis exhibited benign/malignant and magnification-level imbalance. To mitigate this, we employed stratified patient-level splits, on-the-fly augmentation of minority classes (flips, small rotations, brightness jitter), and macro-averaged evaluation metrics. Augmentation equalized class exposure per epoch, eliminating the need for class weighting.

Proposed CancerDet-Net model

The overall CancerDet-Net architecture illustrated in Fig. 3 consists of four main components operating in parallel: (1) a HMSGA branch, (2) a Convolutional Feature Extractor (CFE) branch, (3) two ViT branch with local-window self-attention, and (4) a classification head. Each branch extracts complementary features: HMSGA focuses on multi-scale spatial attention, CFE on efficient convolutional feature maps with channel attention, and ViT on global contextual features. The outputs from these branches are concatenated and fused (via the HMSGA module and a CSF fusion mechanism) to produce a final representation, which the classification head uses to predict the cancer subtype.

Proposed CancerDet-Net model architecture. The network combines separable convolutional layers with multi-scale branches, each enhanced by local-window ViT blocks. Outputs are fused through an HMSGA module and refined with CSF Fusion, before global pooling and classification into nine cancer subtypes.

Hierarchical multi-scale gated attention branch

The HMSGA block is a foundational component of our model, designed to address the challenge of multi-scale feature extraction and effective spatial attention in histopathological image analysis. This block leverages parallel convolutions, localized self-attention, and adaptive gating to robustly capture and emphasize relevant pathological patterns across varying spatial resolutions. HMSGA adaptively reweights CSFs, theoretically ensuring better representation of heterogeneous histopathological patterns.

-

Multi-Scale Convolutional Feature Extraction: Given an input tensor \(\:(X\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:C})\), where \(\:\left(H\right)\), (W), and (C) denote the height, width, and number of channels, respectively. The HMSGA block employs three parallel convolutional operations with kernel sizes \(\:(3\:\times\:3)\), \(\:(5\:\times\:5)\), and \(\:(7\:\times\:7)\). These convolutions use strides 1, 2, and 3, respectively, to extract multi-resolution feature maps:

$$\:[{s}_{1}={\text{Conv}}_{3\times\:3,\hspace{0.17em}\text{stride}=1}\left(X\right)\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:{C}_{1}}]$$$$\:[{s}_{2}={\text{Conv}}_{5\times\:5,\hspace{0.17em}\text{stride}=2}\left(X\right)\in\:{R}^{\frac{H}{2}\times\:\frac{W}{2}\times\:{C}_{2}}]$$$$\:[{s}_{3}={\text{Conv}}_{7\times\:7,\hspace{0.17em}\text{stride}=3}\left(X\right)\in\:{R}^{\frac{H}{3}\times\:\frac{W}{3}\times\:{C}_{3}}]$$Each \(\:\left({s}_{i}\right)\) encodes contextual information at a distinct spatial scale, capturing fine to coarse details vital for recognizing complex tissue structures. To unify these representations, spatial alignment is performed by resizing \(\:\left({s}_{2}\right)\) and \(\:\left({s}_{3}\right)\) to the dimensions of \(\:\left({s}_{1}\right)\) (\(\:(H\:\times\:W)\)) using an interpolation function \(\:\left(\mathcal{R}\left(\cdot\:\right)\right)\):

$$\:[\stackrel{\sim}{{s}_{2}}=\mathcal{R}\left({s}_{2}\right)\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:{C}_{2}},\hspace{1em}\stackrel{\sim}{{s}_{3}}=\mathcal{R}\left({s}_{3}\right)\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:{C}_{3}}]$$The aligned feature maps are then concatenated channel-wise:

$$\:[S=\text{Concat}\left({s}_{1},\stackrel{\sim}{{s}_{2}},\stackrel{\sim}{{s}_{3}}\right)\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:\left({C}_{1}+{C}_{2}+{C}_{3}\right)}]$$This fusion creates a comprehensive multi-scale representation integrating localized and global context.

-

Normalization and Local-window Attention: To stabilize gradients and enhance convergence, layer normalization \(\:\left(\text{LN}\left(\cdot\:\right)\right)\) is applied:

$$\:[{S}_{\text{nr}}=\text{LN}\left(S\right)]$$The normalized feature tensor is partitioned into non-overlapping local-windows of size \(\:(M\:\times\:M)\). Within each window \(\:(w\subset\:{S}_{\text{nr}})\), a Local-Window Attention (LWA) mechanism computes self-attention to model intra-window dependencies:

$$\:[{\text{Attention}}_{w}\left({Q}_{w},{K}_{w},{V}_{w}\right)=\text{Softmax}\left(\frac{{Q}_{w}{K}_{w}^{{\top\:}}}{\sqrt{d}}\right){V}_{w}]$$where \(\:\left({Q}_{w}\right)\), \(\:\left({K}_{w}\right)\), and \(\:\left({V}_{w}\right)\) are the query, key, and value matrices derived from the feature embeddings of window \(w\), and \(d\) is the projection dimension. This localized attention balances computational efficiency and effective spatial context modelling, critical for identifying subtle cellular variations.

-

Dynamic Gating Mechanism: The output from the local attention module \(\:\left(A\right)\) undergoes a dynamic gating process to emphasize diagnostically significant features while suppressing irrelevant noise. The gating function is parameterized by learnable weights \(\:\left({W}_{g}\right)\) and biases \(\:\left({b}_{g}\right)\), and computes a gating map \(\:\left(G\right)\) via a sigmoid activation:

$$\:[G={\upsigma\:}\left({W}_{g}A+{b}_{g}\right),\hspace{1em}{\upsigma\:}\left(z\right)=\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-z}}]$$The gated feature output \(\:\left(F\right)\) is then:

$$\:[F=G\odot\:A]$$where \(\:(\odot\:)\) denotes element-wise multiplication. This adaptivity allows the network to selectively focus on spatial regions critical for accurate cancer detection.

The HMSGA block effectively integrates multi-scale convolutional features, localized attention, and adaptive gating to enhance the representational richness of histopathological images. By combining multi-resolution feature extraction with efficient spatial attention and dynamic feature selection, it enables the model to capture both fine-grained cellular details and broader tissue patterns. The cross-scale fusion mechanism further refines the feature maps, ensuring the network focuses precisely on diagnostically relevant regions, thereby significantly improving classification performance on complex cancer datasets.

Convolutional feature extractor branch

The CFE branch adopts an efficient convolutional architecture optimized specifically for medical imaging applications. The design aims to balance computational efficiency with rich feature representation, which is critical for capturing subtle histopathological patterns.

-

Separable Convolutional Layers for Efficient Feature Extraction: The CFE branch starts by applying depth-wise separable convolutions, which decompose standard convolution into two steps: depth-wise convolution and pointwise convolution. Given an input tensor \(\:(X\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:C})\), A depthwise separable convolution is defined as:

$$\:[Y={\text{Conv}}_{\text{pointwise}}\left({\text{Conv}}_{\text{depth-wise}}\left(X\right)\right)]$$The depth-wise convolution applies a single convolutional filter per input channel, significantly reducing computation compared to traditional convolution. The pointwise convolution (a (1 × 1) convolution) then linearly combines the output channels, allowing interactions across channels and increasing expressiveness. This factorization reduces the number of parameters and computations while preserving the ability to extract detailed features, making it well-suited for large histopathology images where efficiency is important.

-

Batch Normalization for Training Stability: Each separable convolution is followed by a batch normalization (BN) layer, which normalizes the activations to stabilize and accelerate training. Given an activation \(\:\left(a\right)\), batch normalization computes:

$$\:[\widehat{a}=\frac{a-{{\upmu\:}}_{B}}{\sqrt{{{\upsigma\:}}_{B}^{2}+{\epsilon}}},\hspace{1em}\text{BN}\left(a\right)={\upgamma\:}\widehat{a}+{\upbeta\:}]$$where \(\:\left({{\upmu\:}}_{B}\right)\) and \(\:\left({{\upsigma\:}}_{B}^{2}\right)\) are the mean and variance computed over the batch, \(\:\left({\epsilon}\right)\) is a small constant for numerical stability, and \(\:({\upgamma\:},\:{\upbeta\:})\) are learnable parameters for scaling and shifting.

-

Squeeze and Excitation Blocks for Channel Recalibration: To enhance the network’s sensitivity to the most informative feature channels, each convolutional block is paired with a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module. The SE block performs adaptive recalibration through two operations:

-

Squeeze: Global average pooling compresses spatial dimensions, producing a channel descriptor vector \(\:(z\in\:{R}^{C})\):

$$\:[{z}_{c}=\frac{1}{H\times\:W}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{H}{\sum\:}_{j=1}^{W}{X}_{i,j,c}]$$ -

Excitation: A gating mechanism learns channel-wise weights using two fully connected layers with a bottleneck to reduce complexity, applying nonlinearities and sigmoid activation:

$$\:[s={\upsigma\:}\left({W}_{2}\cdot\:{\updelta\:}\left({W}_{1}z\right)\right)]$$where \(\:\left({\updelta\:}\left(\cdot\:\right)\right)\) is a ReLU activation, \(\:\left({\upsigma\:}\left(\cdot\:\right)\right)\) is the sigmoid function, and \(\:({W}_{1}\), \(\:{W}_{2})\) are weight matrices. The output \(\:\left(s\right)\:\)contains learned importance scores for each channel.

The original feature map is rescaled channel-wise:

$$\:[\stackrel{\sim}{{X}_{i,j,c}}={s}_{c}\cdot\:{X}_{i,j,c}]$$This operation allows the network to emphasize channels critical for detecting diagnostic features such as nuclear pleomorphism, cytoplasmic texture, and tissue architecture.

-

-

Stacked Convolution-SE Blocks for Deep Feature Representation: The CFE branch stacks multiple modules consisting of separable convolution, batch normalization, and SE blocks. This deep stacking enables learning increasingly complex and abstract representations of local histopathological patterns. Such a layered design improves the model’s ability to discriminate subtle variations critical for cancer grading and classification.

In summary, the CFE branch efficiently extracts rich local features through depth-wise separable convolutions combined with batch normalization for stable training. The integration of SE blocks enables adaptive channel-wise feature recalibration, focusing the model on diagnostically relevant signals. By stacking these modules, the CFE branch builds a robust hierarchical feature representation that complements other model components in capturing the complexity of histopathological images.

Vision transformer branch

The ViT branch introduces transformer-based modules designed to capture long-range dependencies and model global contextual relationships across the entire histopathological image. This branch is composed of two sequential blocks that progressively refine and enhance the feature representations.

-

ViT Block 1-Initial Refinement: The first step in this block is applying layer normalization (LN) to the input tensor \(\:\left(X\right)\):

$$\:[{X}_{\text{nr}}=\text{LN}\left(X\right)]$$Layer normalization standardizes the input features across the channels, stabilizing the distribution of activations and improving convergence during training. By normalizing the input, the network reduces internal covariate shift and facilitates more effective learning.

The normalized tensor \(\:\left({X}_{\text{nr}}\right)\) is then processed by the LWA module:

$$\:[A=\text{LWA}\left({X}_{\text{nr}}\right)]$$Here, the feature map is partitioned into smaller, non-overlapping local-windows. Within each window, self-attention is computed, enabling the model to focus on relevant spatial regions while maintaining computational efficiency. This mechanism allows the network to capture fine-grained local interactions and approximate global context by aggregating attention across windows.

To mitigate overfitting and improve generalization, dropout regularization is applied:

$$\:[{A}_{\text{do}}=\text{Dropout}\left(A\right)]$$Dropout randomly zeros out elements of the attention output during training, which prevents the network from relying too heavily on specific features and encourages robustness. A residual connection is then employed to add the original input \(\:\left(X\right)\) back to the scaled attention output:

$$\:[{R}_{1}=X+{\upalpha\:}\cdot\:{A}_{\text{do}}]$$Here, \(\:\left({\upalpha\:}\right)\) is a learnable parameter that controls the contribution of the attention output. This skip connection helps preserve the original input signal, facilitates gradient flow during backpropagation, and stabilizes training by preventing vanishing gradients. The combined output \(\:\left({R}_{1}\right)\) thus represents a refined feature map that integrates both the original input and the locally-attended contextual information.

-

ViT Block 2-Deep Enhancement: The second block builds deeper semantic representations by sequentially applying convolutional operations combined with nonlinear activations:

$$\:{Y}_{1}=\text{GELU}\left({\text{Conv}}_{1\times\:1}\left({R}_{1}\right)\right),$$$$\:{Y}_{2}=\text{GELU}\left({\text{Conv}}_{3\times\:3}\left({Y}_{1}\right)\right),$$$$\:{Y}_{3}=\text{GELU}\left({\text{Conv}}_{1\times\:1}\left({Y}_{2}\right)\right)$$The \(\:(1\:\times\:1)\) convolutions act as channel-wise feature transformers, adjusting the feature dimensionality and enabling complex cross-channel interactions, while the \(\:(3\:\times\:3)\) convolution captures spatial patterns and context within the refined feature map. The GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) activation function introduces smooth nonlinearities that improve gradient flow and overall learning dynamics. Following these convolutions, additional layer normalization is applied to further stabilize feature distributions. Stochastic depth regularization is incorporated next, where residual branches are randomly dropped during training:

$$\:[{R}_{2}={R}_{1}+{\upbeta\:}\cdot\:\text{StochasticDepth}\left({Y}_{3}\right)]$$Here, \(\:\left({\upbeta\:}\right)\) is a scaling factor controlling the residual contribution. Stochastic depth serves as an effective form of model regularization, reducing overfitting by encouraging the network to learn more robust features and improving generalization.

The residual connection combines the input to this block \(\:\left({R}_{1}\right)\) with the regularized convolutional output, allowing gradients to propagate efficiently and preserving lower-level features while incorporating deeper semantic information. Together, these two ViT blocks enable the network to learn hierarchical and context-rich features essential for accurately identifying large-scale structural abnormalities in histopathological images, such as gland formations, stromal invasion, and architectural distortions. This comprehensive representation significantly enhances the model’s ability to distinguish complex cancer patterns in tissue samples.

Feature fusion and classification head

After the independent processing of input features by the three distinct branches-HMSGA, CFE, and ViT-their extracted feature representations are combined through a carefully designed fusion mechanism to enable effective multi-scale and multi-context learning, which is essential for robust cancer classification.

-

Feature Fusion: The fusion strategy begins with the direct integration of the gated multi-scale features obtained from the HMSGA branch. These features encapsulate rich spatial information at various resolutions, reflecting fine local details and broader context. Simultaneously, the outputs of the CFE and ViT branches, which tend to be high-dimensional feature maps, are subjected to Global Average Pooling (GAP). This pooling operation condenses each feature map into a compact vector by averaging spatial dimensions, thereby reducing the feature dimensionality and facilitating efficient fusion. Formally, the pooled vectors are represented as:

$$\:[{V}_{CFE}=\text{GAP}{F}_{\text{CE}},\hspace{1em}{v}_{\text{V}}=\text{GAP}\left({F}_{\text{V}}\right)]$$The final fused feature vector is constructed by concatenating the flattened HMSGA output with the GAP vectors from the CFE and ViT branches:

$$\:[{V}_{fused}=\text{Concat\:(}{O}_{HMSGA},{V}_{CFE},{V}_{\text{ViT}}]$$This fusion creates a balanced representation that captures complementary information: local textures and fine details HMSGA, channel-wise recalibration and deep convolutional features CFE, and global structural context ViT. By integrating these diverse feature modalities, the model is better equipped to discriminate complex histopathological patterns.

-

Classification Head: The fused feature vector \(\:\left({V}_{fused}\right)\) serves as input to the classification head, which is composed of two fully connected (dense) layers with interleaved dropout layers. The dropout layers help regularize the model, preventing overfitting by randomly deactivating neurons during training. The sequence of operations is defined as:

$$\:{h}_{1}=\text{DropoutDense}\left({v}_{\text{fsd},{d}_{1}}\right)$$$$\:{h}_{2}=\text{Dropout}\left(\text{Dense}\left({h}_{1},{d}_{2}\right)\right)$$$$\:\widehat{y}=\text{Softmax}\left({h}_{2}\right)$$Here, \(\:\left({d}_{1}\right)\) and \(\:\left({d}_{2}\right)\) denote the dimensionality of the first and second dense layers, respectively, and \(\:\left(\widehat{\varvec{y}}\right)\) is the output probability distribution over the \(\:\left(\:K\:\right)\) cancer classes. The softmax activation ensures that the output probabilities sum to one, enabling the model to make a clear and interpretable classification decision. This modular design of the classification head not only enhances model robustness but also aids generalization across varied histopathological samples, making it clinically viable and interpretable.

Mathematical formulation and workflow of CancerDet-Net

Let the input histopathological image be represented as a three-dimensional tensor:

where (H), (W), and (C) denote the height, width, and number of color channels (RGB) of the image, respectively. This tensor forms the initial input to the CancerDet-Net framework, which is architecturally composed of three primary parallel branches designed to extract diverse and complementary feature representations: the HMSGA HMSGA branch, the CFE branch, and the ViT ViT branch.

-

Feature Extraction Across Parallel Branches: Each branch \(\:\left({\mathcal{F}}_{\mathcal{i}}\left(\cdot\:\right)\right)\) independently processes the input tensor \(\:\left(X\right)\) to extract features with distinct characteristics:

The HMSGA branch, \(\:\left({\mathcal{F}}_{HMSGA}\left(X\right)\right)\), focuses on extracting multi-scale spatial features and applying adaptive gating to emphasize diagnostically relevant regions, producing a feature map:

$$\:[{\mathcal{F}}_{HMSGA}\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:{D}_{1}}]$$where \(\:\left({D}_{1}\right)\) represents the depth or number of feature channels.

The CFE branch, \(\:\left({\mathcal{F}}_{CFA}\left(X\right)\right)\), applies separable convolutions and channel recalibration via squeeze-and-excitation mechanisms to extract efficient and discriminative convolutional features:

$$\:[{\mathcal{F}}_{CFA}\in\:{R}^{{H}^{{\prime\:}}\times\:{W}^{{\prime\:}}\times\:{D}_{2}}]$$Note that due to stride convolutions and pooling operations, \(\:({H}^{{\prime\:}}\le\:H)\) and \(\:({W}^{{\prime\:}}\le\:W)\), reflecting spatial dimension reduction. The ViT branch consists of two sequential transformer blocks, each further refining the feature representations with attention mechanisms capturing long-range dependencies:

$$\:[{F}_{\text{V}}^{\left(1\right)}={\mathcal{F}}_{\text{V}}^{\left(1\right)}\left(X\right)\in\:{R}^{{H}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\times\:{W}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\times\:{D}_{3}}]$$$$\:[{F}_{\text{V}}^{\left(2\right)}={\mathcal{F}}_{\text{V}}^{\left(2\right)}\left({F}_{\text{V}}^{\left(1\right)}\right)\in\:{R}^{{H}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\times\:{W}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\times\:{D}_{4}}]$$Here, \(\:\left({H}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\right)\) and \(\:\left({W}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\right)\) denote spatial dimensions after transformer processing, potentially down-sampled or altered by patch embedding operations.

This architectural division facilitates learning specialized features: HMSGA captures fine-to-coarse spatial hierarchies and important regions; CFE extracts compact convolutional embeddings focusing on texture and channel dependencies; ViT models contextual information over large spatial extents through self-attention.

-

Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Vector Generation: To enable effective fusion and reduce computational complexity, the feature maps from the CFE and ViT branches undergo spatial dimensionality reduction through Global Average Pooling (GAP). GAP aggregates each feature channel by averaging over spatial dimensions, converting feature maps into fixed-size vectors:

$$\:[{V}_{CFE}=\text{GAP}{\varvec{F}}_{\text{CE}}\in\:{R}^{{D}_{2}},\hspace{1em}\text{where}\hspace{1em}{v}_{\text{CFE},c}=\frac{1}{{H}^{{\prime\:}}{W}^{{\prime\:}}}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{{H}^{{\prime\:}}}{\sum\:}_{j=1}^{{W}^{{\prime\:}}}{\varvec{F}}_{\text{CE}\varvec{i},\varvec{j},\varvec{c}}]$$$$\:[{\varvec{v}}_{\text{V}}=\text{GAP}\left({\varvec{F}}_{\text{V}}^{\left(2\right)}\right)\in\:{R}^{{D}_{4}},\hspace{1em}\text{where}\hspace{1em}{v}_{\text{ViT},c}=\frac{1}{{H}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}{W}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}}{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{{H}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}}{\sum\:}_{j=1}^{{W}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}}{\varvec{F}}_{\text{V},\varvec{i},\varvec{j},\varvec{c}}^{\left(2\right)}]$$Meanwhile, the HMSGA feature map preserves spatial granularity to retain detailed information about local structures. It is flattened into a one-dimensional vector encompassing all spatial locations and channels:

$$\:[\mathbf{f}\text{H}\text{M}\text{S}\text{G}\text{A}\:=\text{Flatten}{\varvec{F}}_{\text{HSA}}\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:{D}_{1}}]$$Flattening retains the spatial and channel-wise detail but increases dimensionality, which is addressed later through the classification head.

-

Feature Concatenation and Fusion: The three feature vectors-flattened HMSGA output and GAP-reduced CFE and ViT vectors—are concatenated along the channel dimension to produce a unified and comprehensive feature representation:

$$\:[{F}_{\text{cna}}=\text{Concat}(\text{f}\text{H}\text{M}\text{S}\text{G}\text{A},{v}_{\text{C}\text{F}\text{E},}{V}_{VT})\in\:{R}^{M}]\:,\:where\:[M=H\times\:W\times\:{D}_{1}+{D}_{2}+{D}_{4}]$$This concatenation fuses detailed spatial features with abstracted channel-wise and contextual features, facilitating rich joint representations for classification.

-

Classification Head and Output Prediction: The fused feature vector \(\:\left({\varvec{F}}_{\text{cna}}\right)\) is passed through a multilayer perceptron consisting of two fully connected (dense) layers, each followed by dropout for regularization:

$$\:[{\varvec{h}}_{1}=\text{Dropout}\left(\sigma\:\left({\varvec{W}}_{1}{\varvec{F}}_{\text{cna}}+{\varvec{b}}_{1}\right)\right)]$$$$\:[{\varvec{h}}_{2}=\text{Dropout}\left(\sigma\:\left({\varvec{W}}_{2}{\varvec{h}}_{1}+{\varvec{b}}_{2}\right)\right)]$$$$\:[\widehat{\varvec{y}}=\text{Softmax}\left({\varvec{W}}_{3}{\varvec{h}}_{2}+{\varvec{b}}_{3}\right)]$$where \(\:\left({\varvec{W}}_{\varvec{i}}\right)\) and \(\:\left({\varvec{b}}_{\varvec{i}}\right)\) represent learnable weights and biases of the dense layers, \(\:\left(\sigma\:\left(\cdot\:\right)\right)\) is a nonlinear activation function such as ReLU or GELU, and \(\:(\widehat{\varvec{y}}\in\:{R}^{K})\) is the final predicted probability vector over \(\:\left(K\right)\) cancer classes.

Prior attention-based models such as CLAM and TransMIL, primarily rely on single-stream attention or multiple instances learning without explicit multi-scale feature refinement. Similarly, Swin and DeiT employ hierarchical or windowed attention but lack explicit cross-scale fusion, often leading to either high computational cost (global MHSA) or insufficient contextual integration (pure local-window). In contrast, CancerDet-Net introduces an HMSGA block that combines multi-branch CNN feature extraction with local-window attention and lightweight cross-attention gating. This design explicitly fuses fine lesion details with broader tissue context, enabling robust multi-cancer classification. As demonstrated in our ablation studies, this mechanism achieves higher accuracy and efficiency compared to axial, linearized, or full global attention, while remaining interpretable and deployable.

Hyperparameter settings

Table 4 summarizes the optimized hyperparameters for CancerDet-Net. The model uses a 128 × 128 input size and combines separable convolutions, local-window sparse self-attention (radius 2), and hierarchical gated attention for robust feature extraction. Starting with 64 filters, channels increase progressively. The multi-classification output is trained over 25 epochs with Adam optimizer (learning rate 1 × 10−4) and stochastic depth dropout of 0.1 to mitigate overfitting. These settings were selected based on comprehensive performance evaluations. Hyperparameters such as filter sizes, attention heads, and layer dimensions were carefully selected to balance computational efficiency and classification accuracy. These parameters can be further tuned to optimize performance for specific datasets or tasks.

Explainability of the model using XAI techniques

To evaluate the interpretability of CancerDet-Net, we applied Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) to one representative image from each cancer type: skin, lung, colon, and breast. LIME approximates the model’s local behaviour by fitting an interpretable surrogate model around a given prediction. Let \(\:(f:{R}^{n}\to\:{R}^{k})\:\)denote the CancerDet-Net classifier, where \(\:(\varvec{x}\in\:{R}^{n})\) is the input image and \(\:\left(f\left(\varvec{x}\right)\right)\) yields the class probability. LIME constructs a local surrogate model \(\:\left(g\left({\varvec{x}}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\right)\) by solving the following optimization:

Here, \(\:\left(\mathcal{L}\left(f,g,{\pi\:}_{\varvec{x}}\right)\right)\) measures the fidelity between the black-box model f and the interpretable model g in the local neighbourhood of \(\:\left(\varvec{x}\right)\), weighted by a proximity function \(\:\left({\pi\:}_{\varvec{x}}\right)\), and \(\:\left({\Omega\:}\left(g\right)\right)\) penalizes the complexity of g to maintain interpretability. Figure 4 illustrates the LIME-based visual explanations, highlighting the super pixels that most influence the model’s predictions. These results confirm that CancerDet-Net attends to relevant localized features, enhancing its transparency and reliability for clinical use. In addition to LIME, we employed Grad-CAM to further enhance model interpretability by generating class-discriminative heatmaps. Grad-CAM works by calculating how much each feature map in a selected convolutional layer influences the target class score. It then combines these feature maps using importance weights to highlight the regions that contribute most to the prediction. The ReLU operation is applied to ensure that only positively influential features are visualized. This method allows us to identify the areas within the input image that are most responsible for the network’s decisions, providing an additional layer of transparency. Figure 5 illustrates Grad-CAM visualizations across different cancer types, clearly highlighting the model’s focus areas. This combination of high-performance classification via CancerDet-Net and interpretability through LIME and Grad-CAM underscores the robustness and transparency of our approach.

Performance evaluation metrics

To evaluate CancerDet-Net, we used standard multi-class metrics: precision, recall, macro F1-score, and accuracy. Precision reflects the ability to avoid false positives, recall indicates sensitivity to true cases, and the macro F1-score balances both while giving equal weight to all classes. Accuracy captures overall correctness by measuring the proportion of correctly classified samples. Mathematically, precision averaged across all classes is expressed as:

where \(\:\left(T{P}_{i}\right)\) and \(\:\left(F{P}_{i}\right)\) denote the number of true positives and false positives for class i, and N is the total number of classes. Similarly, the macro recall is computed as:

with \(\:\left(F{N}_{i}\right)\) representing the false negatives for class i. The macro F1 score, balancing precision and recall, is calculated by:

Lastly, overall accuracy is defined as:

where \(\:\left(T{N}_{i}\right)\) represents the true negatives for class i.

Results and discussion

Baseline comparison

Table 5 presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed CancerDet-Net model against eight well-established pretrained architectures: InceptionV359, MobileNetV260, Xception61, VGG1662, DenseNet12163, ResNet5064, EfficientNetB065, and ShuffleNetV266. Among the baseline models, Xception performed best (95.55% accuracy, precision/recall/F1 all 95.55%), followed by VGG16 (94.95% accuracy) and InceptionV3 (94.67%). Deeper networks like DenseNet121 and ResNet50 reached ~ 92–93% accuracy, while lightweight models (EfficientNetB0, ShuffleNetV2) trailed (88–81%), likely due to their emphasis on efficiency over accuracy. While Xception and VGG16 performed strongly, CancerDet-Net’s higher precision and recall demonstrate its superior ability to balance sensitivity and specificity across diverse cancer types.

Confusion matrix and classification report analysis

Figure 6 illustrates the confusion matrix summarizing the classification results of CancerDet-Net across nine histopathological cancer categories, including benign and malignant subtypes of breast, skin, colon, and lung cancers. The model exhibits excellent overall performance, with perfect classification observed for both benign and malignant skin cancer classes, highlighting its strong discriminatory power for these categories. Minor misclassifications occur between benign and malignant breast cancer samples, with 10 benign instances predicted as malignant and 14 malignant cases labelled as benign, indicating subtle feature overlaps. Similarly, slight confusion is noted between colon adenocarcinoma and normal colon classes. Lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma classes demonstrate some misclassification, with 23 adenocarcinoma samples predicted as squamous cell carcinoma and 10 cases of the reverse, reflecting the histopathological similarity between these subtypes. These results confirm the high accuracy and robustness of CancerDet-Net while identifying specific areas for refinement to improve differentiation of closely related cancer types.

The per-class heatmap in Fig. 7 illustrates that CancerDet-Net achieves consistently high precision, recall, and F1-scores across all nine cancer subtypes. Most categories, including colon and lung cancers, reached perfect scores, while skin cancer subtypes displayed slightly lower but still strong performance (F1 ≈ 0.95–0.96). This balance indicates that the model not only excels on well-represented classes but also maintains robustness in more challenging cases with subtle morphological differences.

ROC curve analysis

ROC and AUC curves were generated using the held-out test set predictions, with true positive and false positive rates calculated across all thresholds. Results are reported per cancer subtype and macro-averaged for overall performance. The multi-class ROC curves illustrated in Fig. 8 demonstrate excellent discriminative ability. Each cancer subtype’s ROC curve had an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 1.00, meaning the model separated positive and negative instances of each class almost perfectly in the test set. This nearly perfect AUC indicates that for each cancer category, CancerDet-Net assigns consistently higher scores to true positives over false positives.

Misclassification analysis

Although CancerDet-Net achieved strong overall performance, a closer inspection of misclassifications revealed several recurring error patterns. Figure 9 presents representative examples with Grad-CAM visualizations for both predicted and ground-truth classes. In some cases, the model relied on spurious artifacts or background context, for example, attention concentrated on slide borders, illumination bands, or hair-like structures rather than lesion morphology, leading to benign samples being misclassified as malignant. Other errors arose from weak or diffuse evidence, where attention was scattered and class probabilities were nearly indistinguishable, consistent with genuinely ambiguous histological appearances. A third category involved mismatched evidence, in which the predicted attribution map highlighted non-diagnostic regions while ignoring the discriminative lesion core, resulting in malignant cases incorrectly labelled as benign. More specifically, In Fig. 9, examples (a) and (i) illustrate this artifact-focus issue, (b, c, d, f) show diffuse attention in ambiguous cases, and (e, g, h) show attention missing the lesion core.

Statistical analysis and robustness evaluation

To further validate the reliability of CancerDet-Net, we conducted additional statistical analyses beyond single-run accuracy reporting. Table 6 summarizes mean performance values across multiple independent runs, along with standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals, demonstrating the stability of the proposed model. We also report calibration measures, including Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and Brier score, which confirm that CancerDet-Net produces well-calibrated probabilities suitable for clinical decision support. Comparative baselines (ViT, DeiT, and Swin) are included for fairness, showing that CancerDet-Net consistently achieves higher macro-F1, balanced accuracy, and AUC values with lower variability.

To assess performance variability, we repeated training with three different random seeds (47, 52, 57). CancerDet-Net achieved highly consistent results, with macro precision, recall, F1-score, and validation accuracy all remaining within a narrow range (0.9843–0.9849). The average macro F1-score across seeds was 0.9845 ± 0.0003, and the average validation accuracy was 0.9845 ± 0.0003, confirming that the reported performance is stable and not dependent on a single initialization. The summary results are shown in Table 7.

Expert validation

To further verify the credibility and robustness of CancerDet-Net, we performed two types of validation beyond conventional metrics.

-

i.

Independent Test Validation: We evaluated the model on an independent set of 50 histopathological images per cancer subtype (450 images in total), spanning lung, colon, skin, and breast cancers. CancerDet-Net achieved an overall accuracy of 97.56%, with most predictions aligning along the diagonal of the confusion matrix. Misclassifications were minimal and occurred primarily between histologically similar classes, reflecting realistic diagnostic challenges. This validation confirmed that the model maintains high reliability across diverse cancer categories. Figure 10 represents the validation confusion matrix for the external dataset.

-

ii.

Web and Mobile Application Validation: To assess deployment robustness, we validated the real-time classification system through the web interface and Android mobile application. Cancer histopathology images were uploaded directly, and predictions were generated within seconds. Across multiple test uploads, the app consistently reproduced classification outcomes with the same reliability as the standalone model, confirming that performance is preserved in fast, user-facing environments. This validation highlights the model’s practical readiness for integration into clinical workflows and its potential to support decision-making in both hospital and remote healthcare settings.

Ablation study

Table 8 presents the performance metrics of the CancerDet-Net model under various configurations and architectural modifications on the Nine Types of Cancer dataset. Metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score provide a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s sensitivity to input resolution and core architectural components. The highest performance is achieved with an input size of 128 × 128, yielding 98.51% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, balancing computational efficiency and classification effectiveness. Reducing input size to 64 × 64 results in a notable drop (94.44% accuracy), while increasing to 224 × 224 slightly improves over 64 × 64 but remains below the optimal configuration. Various attention mechanisms were tested, with local-window attention matching the best overall results, highlighting its effectiveness in modelling localized dependencies. Cross attention and multi-head self-attention also performed well, whereas axial and linearized self-attention showed reduced accuracy. Ablation of the HMSGA, CFE, and ViT blocks progressively degraded performance, confirming the importance of each branch. Using only one ViT block decreased accuracy, but employing two restored peak performances, underscoring the contribution of hierarchical ViT layers. These findings validate the critical role of input configuration and architectural design in maximizing CancerDet-Net’s classification performance.

Unlike prior models that rely on a single attention mechanism, CancerDet-Net integrates local-window attention with an HMSGA block. The HMSGA design incorporates three CNN branches at different strides, followed by normalization, local-window attention, and content-adaptive gating with channel–spatial fusion. Through lightweight cross-attention and gating, this architecture explicitly fuses fine-grained lesion details with broader tissue context. Our ablation experiments demonstrate that this configuration outperforms axial, linearized, and global multi-head self-attention, while being more computationally efficient than full global attention. Table 9 shows the comparative overview of attention mechanisms considered in CancerDet-Net and related models.

Experimental results across individual datasets

We further evaluated the attention mechanisms and input resolutions on each dataset individually in Tables 10 and 11. The local-window attention consistently yielded the highest accuracy on all datasets (skin, breast, lung/colon, and the combined sets), outperforming axial, linear, etc., in each case. Similarly, 128 × 128 input size gave the best or near-best results on each dataset, whereas 64 × 64 was insufficient and 224 × 224 did not provide additional gain proportional to its cost. These findings reinforce that our chosen configuration generalizes well across different cancer types and dataset conditions.

Comparison with previous studies

Table 12 compares our model to a range of existing methods (traditional CNNs, ensembles, and recent deep models) on the same datasets. While many models achieve high accuracy on individual datasets (e.g., up to ~ 99% on LC25000 or BreakHis in some cases), none have been evaluated on the combined multi-cancer tasks (the 7-class or 9-class datasets). CancerDet-Net not only maintains high performance on the individual datasets, but also achieves 97–98% accuracy on the 7-class and 9-class combined tasks, where other methods would typically degrade or have not been reported. To our knowledge, this is the first work to demonstrate such broad generalization across multiple cancers in histopathology.

To ensure transparent and standardized reporting, we performed a self-assessment of our study using the CLAIM (Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging) guidelines. This assessment confirmed that key aspects, including dataset description, model architecture, training procedures, evaluation metrics, error analysis, and interpretability methods, were fully addressed. Certain items such as external clinical validation and demographic reporting were not applicable and are acknowledged as limitations. The full CLAIM checklist mapping is provided in Supplementary Table A1.

Limitations

While CancerDet-Net demonstrates strong performance and practical deployment potential, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study relies on publicly available datasets (LC25000, ISIC 2019, BreakHis), which may not fully represent the variability of real-world clinical settings. External validation using multi-institutional datasets was not performed, limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, although class imbalance was mitigated using augmentation and weighted loss functions, rare cancer subtypes remain underrepresented, which may still influence per-class sensitivity. Third, the model primarily operates on image patches, which may miss broader contextual cues available in whole-slide imaging (WSI); future work should explore gigapixel-level integration. Fourth, despite the inclusion of Grad-CAM and LIME for interpretability, these methods provide post-hoc explanations and may not fully capture the model’s decision process. Cross-dataset validation and prospective clinical trials are needed to confirm robustness. Future work may incorporate k-fold cross-validation for further robustness validation. Finally, while the deployment through web and mobile applications increases accessibility, issues such as data privacy, computational resources in low-power devices, and clinical workflow integration must be addressed before routine adoption.

Model deployment

We developed a cross-platform deployment strategy to enable real-time interaction with CancerDet-Net via both a web application and a mobile app which is illustrated in Figs. 11 and 12. In the WebApp, users upload histopathological images (PNG/JPG/JPEG) through a Streamlit interface, which forwards inputs to the backend where the trained CancerDet-Net model (.h5) is hosted. The system processes images in real time, displays classification results, and generates a downloadable PDF report. Cloud-based deployment ensures scalability and fast inference. For the Mobile App, the model was converted to TensorFlow Lite for lightweight, on-device inference. Built in Android Studio (Kotlin + XML), the app allows users to capture or upload images, processes them locally without internet access, and displays immediate results. This low-latency design makes the tool suitable for real-world use in resource-limited settings. Validation with unseen images of lung, colon, breast, and skin cancers showed consistently accurate predictions with high confidence. Together, the dual deployment strategy web-based with backend inference and mobile-based with on-device inference enhances accessibility and bridges advanced AI-driven cancer diagnostics with practical clinical applications.

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, we introduced CancerDet-Net, a unified DL framework capable of classifying multiple cancer types from histopathology images within a single model. By combining hierarchical multi-scale attention, local-window transformers, and separable CNNs, CancerDet-Net achieved accuracy (~ 98.5%) across nine cancer subtypes spanning skin, breast, lung, and colon cancers. It outperformed conventional single-disease models and demonstrated robust generalization across diverse datasets. The model also provides transparent predictions via LIME and Grad-CAM visualizations, enhancing trust in its decisions. Moreover, we validated that CancerDet-Net can be deployed in real-world scenarios through a web interface and mobile app, enabling real-time cancer classification in both hospital and remote settings. Although CancerDet-Net demonstrates strong performance and deployment readiness, several extensions remain for future exploration. First, external validation on multi-institutional datasets will be crucial to assess generalizability in real-world clinical settings. Second, integration with whole-slide image (WSI) analysis, rather than patch-based classification, may further enhance diagnostic reliability. Third, adaptive learning strategies that allow the model to continuously improve from new data could mitigate domain shift challenges. Fourth, combining histopathology with other modalities such as radiology or genomics may offer richer diagnostic insights. Finally, further optimization for resource-constrained devices will improve accessibility in low-resource healthcare environments84,85.

Data availability

The merged dataset containing all nine types of cancer is available at: (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/darun04/9-types-of-cancer-histopathological-data-set).

References

World Health Organization. Cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (World Health Organization, 2025).

Gurcan, M. N. et al. Histopathological image analysis: a review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2, 147–171 (2009).

Kumar, P. et al. Evaluation of diagnostic services in rural and remote areas: bottlenecks, success stories, and solutions. J. Surg. Specialties Rural Pract. 6, 32–37 (2025).

Baranwal, N., Doravari, P. & Kachhoria, R. Classification of histopathology images of lung cancer using convolutional neural network (CNN). CRC Press eBooks 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003272694-7 (2022).

Iqbal, S., Qureshi, A. N., Alhussein, M., Aurangzeb, K. & Kadry, S. A novel heteromorphous convolutional neural network for automated assessment of tumors in colon and lung histopathology images. Biomimetics 8, 370–370 (2023).

Provath, M. A. M., Deb, K., Dhar, P. K. & Shimamura, T. Classification of lung and colon cancer histopathological images using global context attention based convolutional neural network. IEEE Access. 11, 110164–110183 (2023).

McCoy, L. G., Brenna, C. T. A., Chen, S. S., Vold, K. & Das, S. Believing in black boxes: machine learning for healthcare does not need explainability to be evidence-based. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 142, 252–257 (2022).

Hirra, I. et al. Breast cancer classification from histopathological images using Patch-Based deep learning modeling. IEEE Access. 9, 24273–24287 (2021).

Hassija, V. et al. Interpreting black-box models: a review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 16, 45–74 (2023).

Ijaz, M. F., Woźniak, M. & Editorial Recent advances in deep learning and medical imaging for cancer treatment. Cancers 16, 700 (2024).

Tiwari, A. et al. The current landscape of artificial intelligence in computational histopathology for cancer diagnosis. Discover Oncol. 16, 1 (2025).

Tsuneki, M. Deep learning models in medical image analysis. J. Oral Biosci. 64, 1 (2022).

Sultan, A. S., Elgharib, M. A., Tavares, T., Jessri, M. & Basile, J. R. The use of artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in oncologic histopathology. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 49, 849–856 (2020).

Lee, Y. & Lee, C. K. Classification of multiple cancer types by multicategory support vector machines using gene expression data. Bioinformatics 19, 1132–1139 (2003).

Abdullah, T. A. A., Zahid, M. S. M. & Ali, W. A review of interpretable ML in healthcare: Taxonomy, applications, challenges, and future directions. Symmetry 13, 2439 (2021).

Dinov, I. D. Methodological challenges and analytic opportunities for modeling and interpreting big healthcare data. GigaScience 5, 1 (2016).

Hekmat, A., Zuping, Z., Bilal, O. & Khan, S. U. R. Differential evolution-driven optimized ensemble network for brain tumor detection. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-025-02629-6 (2025).

Bilal, O., Hekmat, A. & Khan, S. U. R. Automated cervical cancer cell diagnosis via grid search-optimized multi-CNN ensemble networks. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inf. Bioinf. 14, 1 (2025).

Khan, S. U. R., Asim, M. N., Vollmer, S. & Dengel, A. AI-Driven Diabetic Retinopathy Diagnosis Enhancement through Image Processing and Salp Swarm Algorithm-Optimized Ensemble Network. http://arxiv.org/abs/2503.14209 (2025).

Maqsood, H. & Khan, S. U. R. K. MeD-3D: A Multimodal Deep Learning Framework for Precise Recurrence Prediction in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC). http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.07839 (2025).

Khan, S. U. R. et al. ShallowMRI: A novel lightweight CNN with novel attention mechanism for multi brain tumor classification in MRI images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 111, 108425 (2025).

Khan, S. U. R., Asim, M. N., Vollmer, S. & Dengel, A. FOLC-Net: A Federated-Optimized Lightweight Architecture for Enhanced MRI Disease Diagnosis Across Axial, Coronal, and Sagittal Views. http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.06763 (2025).

Lan, Y. C. et al. Ecologically sustainable benchmarking of AI models for histopathology. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 1 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Vision Transformers for computational histopathology. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 1, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1109/rbme.2023.3297604 (2023).

Hoque, R., Das, S., Hoque, M. & Hoque, M. Breast cancer classification using XGBoost. World J. Adv. Res. Reviews. 21, 1985–1994 (2024).

Batool, A. & Byun, Y. C. Enhanced sentiment analysis and topic modeling during the pandemic using automated latent dirichlet allocation. IEEE Access. 12, 81206–81220 (2024).

Kaddes, M., Ayid, Y. M., Elshewey, A. M. & Fouad, Y. Breast cancer classification based on hybrid CNN with LSTM model. Sci. Rep. 15, 1 (2025).

Wani, N. A., Kumar, R. & Bedi, J. Harnessing fusion modeling for enhanced breast cancer classification through interpretable artificial intelligence and in-depth explanations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 136, 108939–108939 (2024).

Prinzi, F., Orlando, A., Gaglio, S. & Vitabile, S. Breast cancer classification through multivariate radiomic time series analysis in DCE-MRI sequences. Expert Syst. Appl. 249, 123557–123557 (2024).

Chakravarthy, S. et al. Multi-class breast cancer classification using CNN features hybridization. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 17, 1 (2024).

Ozdemir, B. & Pacal, I. A robust deep learning framework for multiclass skin cancer classification. Sci. Rep. 15, 1 (2025).

Houssein, E. H. et al. An effective multiclass skin cancer classification approach based on deep convolutional neural network. Cluster Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-024-04540-1 (2024).

Hermosilla, P., Soto, R., Vega, E., Suazo, C. & Ponce, J. Skin cancer detection and classification using neural network algorithms: a systematic review. Diagnostics 14, 454 (2024).

Mukhlif, Y. A. et al. Ant colony and Whale optimization algorithms aided by neural networks for optimum skin lesion diagnosis: a thorough review. Mathematics 12, 1049–1049 (2024).

Yang, G., Luo, S. & Greer, P. Advancements in skin cancer classification: a review of machine learning techniques in clinical image analysis. Multimedia Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-19298-2 (2024).

Naeem, A. & Anees, T. A multiclassification framework for skin cancer detection by the concatenation of Xception and ResNet101. J. Comput. Biomedical Inf. 6, 205–227 (2023).

Imran, T., Alghamdi, A. S. & Alkatheiri, M. S. Enhanced skin cancer classification using deep learning and nature-based feature optimization. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. research/Engineering Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 14, 12702–12710 (2024).

Hasan, M. et al. Vision transformer-based classification for lung and colon cancer using histopathology images. In 2023 International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA) 1300–1304. https://doi.org/10.1109/icmla58977.2023.00196 (2023).

Shahadat, N. Lung and colon cancer histopathological image classification using 1D convolutional channel-based attention networks. Int. FLAIRS Conf. Proc. 37, 1 (2024).

Mengash, H. A. et al. Leveraging marine predators algorithm with deep learning for lung and colon cancer diagnosis. Cancers 15, 1591–1591 (2023).

Khan, S. & Kumar, V. A novel hybrid GRU-CNN and residual bias (RB) based RB-GRU-CNN models for prediction of PTB diagnostic ECG time series data. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 94, 106262 (2024).

Uddin, A. H. et al. Colon and lung cancer classification from multi-modal images using resilient and efficient neural network architectures. Heliyon 10, e30625 (2024).

Gulsoy, T., Kablan, E. B. & FocalNeXt A ConvNeXt augmented FocalNet architecture for lung cancer classification from CT-scan images. Expert Syst. Appl. 1, 125553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125553 (2024).

Krishnamurthy, S. et al. Three-dimensional lung nodule segmentation and shape variance analysis to detect lung cancer with reduced false positives. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H J. Eng. Med. 230, 58–70 (2015).

Musthafa, M. M., Manimozhi, I., Mahesh, T. R. & Guluwadi, S. Optimizing double-layered convolutional neural networks for efficient lung cancer classification through hyperparameter optimization and advanced image pre-processing techniques. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 24, 1 (2024).

Azar, A. T. et al. Automated system for colon cancer detection and segmentation based on deep learning techniques. Int. J. Sociotechnology Knowl. Dev. 15, 1–28 (2023).

Zheng, H., Zhang, Q., Gong, Y., Liu, Z. & Chen, S. Identification of Prognostic Biomarkers for Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma in Female Nonsmokers Using Machine Learning 323–326. https://doi.org/10.1109/icbase63199.2024.10762221 (2024).

Sangeetha, S. et al. An enhanced multimodal fusion deep learning neural network for lung cancer classification. Syst. Soft Comput. 1, 200068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sasc.2023.200068 (2023).

Gayap, H. T. & Akhloufi, M. A. Deep machine learning for medical diagnosis, application to lung cancer detection: a review. BioMedInformatics 4, 236–284 (2024).

Dawood, H., Nawaz, M., Ilyas, M. U., Nazir, T. & Javed, A. Attention-guided CenterNet deep learning approach for lung cancer detection. Comput. Biol. Med. 186, 109613 (2025).

Nakach, F. Z. & Idri, A. Evgin Goceri. A comprehensive investigation of multimodal deep learning fusion strategies for breast cancer classification. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 1 (2024).

Sobur, A. & Rana, I. C. Advancing cancer classification with hybrid deep learning: image analysis for lung and colon cancer detection. Ssrn.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4853237 (2024).

Wani, N. A., Kumar, R., Bedi, J. & DeepXplainer An interpretable deep learning based approach for lung cancer detection using explainable artificial intelligence. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 243, 107879 (2023).

Garreau, D. & Luxburg, U. Explaining the explainer: A first theoretical analysis of LIME. proceedings.mlr.press 1287–1296. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v108/garreau20a.html (2020).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. openaccess.thecvf.com 618–626. https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_iccv_2017/html/Selvaraju_Grad-CAM_Visual_Explanations_ICCV_2017_paper.html (2017).

Borkowski, A. LC25000. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14998042 (2025).

Cassidy, B., Kendrick, C., Brodzicki, A., Jaworek-Korjakowska, J. & Yap, M. H. Analysis of the ISIC image datasets: Usage, benchmarks and recommendations. Med. Image. Anal. 75, 102305 (2022).

Agarwal, P., Yadav, A. & Mathur, P. Breast cancer prediction on breakhis dataset using deep Cnn and transfer learning model. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2641-8_8 (2021).

Team, K. Keras documentation: InceptionV3. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/inceptionv3/.

Team, K. Keras documentation: MobileNet and MobileNetV2. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/mobilenet/.

Team, K. Keras documentation: Xception. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/xception/.

Keras. Keras documentation: VGG16 and VGG19. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/vgg/.

Team, K. Keras documentation: DenseNet. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/densenet/.

Team, K. Keras documentation: ResNet and ResNetV2. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/resnet/.

Team, K. Keras documentation: EfficientNet B0 to B7. keras.io. https://keras.io/api/applications/efficientnet/.

PyTorch ShuffleNet V2—Torchvision main documentation. Pytorch.org. https://docs.pytorch.org/vision/main/models/shufflenetv2.html (2024).

Masud, M., Sikder, N., Nahid, A. A., Bairagi, A. K. & AlZain, M. A. A machine learning approach to diagnosing lung and colon cancer using a deep learning-based classification framework. Sensors 21, 748 (2021).

Maharaju, R. & Valupadasu, R. Advanced cloud framework for lung cancer diagnosis and severity evaluation in deep learning. In 2025 8th International Conference on Information and Computer Technologies (ICICT) 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1109/icict64582.2025.00072 (2025).

Mehmood, S. et al. Malignancy detection in lung and colon histopathology images using transfer learning with class selective image processing. IEEE Access. 10, 25657–25668 (2022).

Pasha, M. et al. Optimized ensemble learning for lung and colon cancer classification using histopathology images from LC25000 dataset. In 2025 International Conference on Electronics and Renewable Systems (ICEARS) 1874–1879. https://doi.org/10.1109/icears64219.2025.10940322 (2025).

Chhillar, I. & Singh, A. A feature engineering-based machine learning technique to detect and classify lung and colon cancer from histopathological images. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 62, 913–924 (2023).

Dabass, M., Dabass, J., Vashisth, S. & Vig, R. A hybrid U-Net model with attention and advanced convolutional learning modules for simultaneous gland segmentation and cancer grade prediction in colorectal histopathological images. Intelligence-Based Med. 7, 100094 (2023).

Said, R. et al. Innovative deep learning architecture for the classification of lung and colon cancer from histopathology images. Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 2024, 1 (2024).

Kassem, M. A., Hosny, K. M. & Fouad, M. M. Skin lesions classification into eight classes for ISIC 2019 using deep convolutional neural network and transfer learning. IEEE Access 8, 1 (2020).

Javaid, A., Sadiq, M. & Akram, F. Skin cancer classification using image processing and machine learning. IEEE Xplore 439–444. https://doi.org/10.1109/IBCAST51254.2021.9393198 (2021).

Himel, G. M. S. et al. Skin cancer segmentation and classification using vision transformer for automatic analysis in dermatoscopy-based noninvasive digital system. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2024, 1–18 (2024).

Rashid, J., Boulaaras, S. M., Saleem, M. S., Faheem, M. & Shahzad, M. U. A novel transfer learning approach for skin cancer classification on ISIC 2024 3D total body photographs. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 35, 1 (2025).

Xiao, M., Li, Y., Yan, X., Gao, M. & Wang, W. Convolutional Neural Network Classification of Cancer Cytopathology Images: Taking Breast Cancer as an Example 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1145/3653946.3653968 (2024).

Simonyan, E. O., Badejo, J. A. & Weijin, J. S. Histopathological breast cancer classification using CNN. Mater. Today Proc.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.10.154 (2023).

Gül, M. A novel local binary patterns-based approach and proposed CNN model to diagnose breast cancer by analyzing histopathology images. IEEE Access. 13, 39610–39620 (2025).

Eshun, R. B. & Bikdash, M. Kamrul Islam. A deep convolutional neural network for the classification of imbalanced breast cancer dataset. Healthc. Analytics. 5, 100330 (2024).

Yan, Y., Lu, R., Sun, J., Zhang, J. & Zhang, Q. Breast cancer histopathology image classification using transformer with discrete wavelet transform. Med. Eng. Phys. 138, 104317 (2025).

Chikkala, R. B. et al. Enhancing breast cancer diagnosis with bidirectional recurrent neural networks: a novel approach for histopathological image multi-classification. IEEE Access. 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2025.3542989 (2025).

Wu, Y. et al. Recent advances of deep learning for computational histopathology: principles and applications. Cancers 14, 1199 (2022).

Cooper, M. C., Ji, Z. & Krishnan, R. G. Machine learning in computational histopathology: challenges and opportunities. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.23177 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.N. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology design, validation, investigation, data curation, and writing of the original draft. N.J.N. provided essential resources for the study. M.M.I. contributed to validation, original draft writing, review and editing, and overall supervision. M.S.R. and A.B.M.S.A. provided supervision throughout the research process. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nayeem, M., Nisita, N.J., Islam, M. et al. Cross-platform multi-cancer histopathology classification using local-window vision transformers. Sci Rep 15, 40896 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24791-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24791-1