Abstract

Retinal neovascularization (RNV) is a leading cause of blindness. Although anti-VEGF therapy remains the first-line treatment for RNV, a subset of patients exhibits poor or no response to anti-VEGF agents. Therefore, exploring alternative therapeutic strategies is imperative. Rac1, a small GTPase, has been reported to regulate angiogenesis through multiple signaling pathways. Nevertheless, the precise role of Rac1 in RNV progression remains unclear. Our study demonstrates that NSC23766, a Rac1 activation inhibitor, effectively attenuates VEGF-induced angiogenic responses in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs), including proliferation, migration, invasion, and tube formation. Furthermore, phalloidin staining revealed that NSC23766 significantly inhibits VEGF-induced cytoskeleton rearrangement in HRMECs while modulating phosphorylation levels of LIMK and cofilin. Western blot analysis reveals that VEGF-induced VEGFR2 phosphorylation activates Rac1 in a time-dependent manner. Further investigation demonstrates that NSC23766 suppresses VEGFR2 phosphorylation by blocking Rac1 activation. Based on these findings, we propose the existence of a positive feedback loop between Rac1 and VEGFR2. Notably, in an oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model, intravitreal injection of NSC23766 significantly attenuated RNV progression. Therefore, our findings suggest that NSC23766 is a potential therapeutic strategy for RNV by disrupting the positive feedback loop between Rac1 and VEGFR2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinal neovascularization (RNV) is a leading cause of blindness. A series of ocular diseases contribute to RNV, including retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)1, age-related macular degeneration (AMD)2, and diabetic retinopathy (DR)3. Pathologically, the invasion of new vessels into the retina damages the normal retinal anatomical structure, and the compromise of photoreceptor cells (cones and rods) further contributes to patients’ vision loss2,3. Intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF drugs (e.g., ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept) is the first-line treatment for RNV4. However, a subset of patients shows no response to anti-VEGF therapy, suggesting the involvement of additional pathogenic factors in RNV4. Consequently, the targeting of additional pathogenic cytokines may serve as an alternative therapeutic approach for patients who show no response to anti-VEGF treatments.

Angiogenesis involves contributions from multiple cell types. Endothelial cells (ECs), which line the interior of blood vessels, play a central role in this process. The biological functions of ECs - including migration, proliferation, invasion, and tube formation - are essential for angiogenesis. Enhanced EC migration, proliferation, and invasion capabilities promote angiogenesis5. The reorganization of the cytoskeleton enables ECs to form lamellipodia and guides their migration toward VEGF-induced angiogenic sprouting sites6. Among the signaling pathways regulating angiogenesis, VEGF/VEGFR2 has been identified as the dominant signaling pathway leading to RNV7. VEGF undergoes alternative exon splicing to generate multiple isoforms, with VEGF165 being the predominant physiological isoform7. Upon binding to the extracellular domain of VEGFR2, VEGF induces receptor dimerization and phosphorylation at multiple tyrosine residues (including Y1175, Y951, and Y1214). Notably, phosphorylation at Y1175 is particularly crucial for downstream pathway activation and the enhancement of EC biological functions that promote angiogenesis8,9. Numerous cytokines have been identified as regulators of biological functions through the VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway. For instance, junctional adhesion molecule-like protein promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer10, soluble E-cadherin exacerbates vessels permeability via VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling in acute lung injury11. Despite these findings, the factors involved in VEGF/VEGFR2-mediated angiogenesis regulation are complex, and the molecular mechanisms contributing to VEGF165-induced phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Y1175 remain largely unknown. The complexity of VEGF signaling pathways provides crucial explanations for patients who show no response to anti-VEGF treatments.

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), a member of the Rho family of small GTPases, regulates cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration by cycling between GTP-bound (active) and GDP-bound (inactive) states in the cytoplasm12. Rac1 plays critical roles in tumor-associated biological processes, including cell proliferation, migration, mesenchymal transition, and angiogenesis13. Previous studies have demonstrated that Rac1 participates in angiogenesis-related signaling pathways, such as NOX/ROS, DLL4/Notch, and YAP/TAZ signaling pathways14,15, Rac1 additionally upregulates VEGF expression by inhibiting p53 degradation in tumor cells16. However, the molecular crosstalk between Rac1 activation and VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathways remains to be fully characterized. Further research has revealed that Rac1 is essential for embryonic development; genetic ablation of Rac1 leads to embryonic lethality due to defective vascularization17. Despite, Rac1 has been established role in physiological and tumor angiogenesis, the functional contributions and molecular mechanisms of Rac1 in pathological retinal neovascularization remain poorly understood.

This study reveals that VEGF-induced enhancement of HRMEC proliferation, migration, invasion, tube formation, and cytoskeletal reorganization was inhibited by NSC23766-mediated Rac1 inactivation. In HRMECs, Rac1 activity is essential for VEGF-induced VEGFR2 phosphorylation; inhibition of Rac1 with NSC23766 significantly reduced VEGF-triggered VEGFR2 phosphorylation. Furthermore, the LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway, which regulates cytoskeletal reorganization, was disrupted by NSC23766, as evidenced by suppressed VEGF-induced phosphorylation of LIMK and cofilin. In vivo, intravitreal administration of NSC23766 reduced retinal neovascularization area in the oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model. These findings suggest that Rac1 inhibition represents a potential therapeutic strategy for RNV.

Methods

Major reagents

Anti-VEGF receptor 1, Anti-VEGF receptor 2, Anti-phospho-VEGF receptor 2 (pTyr 1175), Anti-LIMK 1, Anti-phospho-LIMK 1 (pThr508), Anti-Cofilin, Anti-phospho-Cofilin (pSer3), Anti-AKT, Anti-phospho-AKT, Anti-β-Actin antibodies are purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Trask Lane, Danvers, MA). the secondary antibodies of the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Beyotime (shanghai, China), protein signals were detected by BeyoECL star which was purchased from Beyotime (shanghai, China). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Recombinant Human VEGF (VEFF-A165 isoform) protein was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Basement Membrane Matrix was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY). The gelatin used for pre-coated cell culture dishes was purchased from leagene (Beijing, China). The specific Rac inhibitor NSC23766 was obtained from GLPBIO (Montclair, CA, USA). Rac1 activity was examined using Rac1 activations assay kit which was derived from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Griffonia simplicifolia lectin I-isolectin B4 (GSL I-B4) (FITC-conjugated; Invitrogen, Burlingame, CA) was used to visualize retinal vasculature.

Cell culture

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) were obtained from BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China). The cells were cultured in EGMTM-2 Endothelial Cell Growth Medium-2 (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) in 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes. All cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, with the medium replaced every two days. Upon reaching confluence, HRMECs were passaged, and experiments were conducted using cells between passages 3 and 7. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University (Approval No. HYLL-2021-132) and conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975). All procedures were performed following applicable institutional guidelines and regulations.

Western blotting assay

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 30 min on ice. The lysates were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were collected and mixed with 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, followed by boiling for 8 min. Protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with rapid blocking buffer at room temperature for 20 min, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C (all primary antibodies were diluted at 1:1000). The next day, membranes were washed three times with PBST (5 min per wash) and then incubated with either anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. After additional PBST washes (three times, 5 min each), protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescent Western blot detection reagents and the grayscale intensity of protein bands was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0, National Institutes of Health, USA).

NSC23766 cytotoxicity assay

HRMECs were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well. Upon reaching 80% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with EGM-2 containing specified concentrations of NSC23766 (0, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 µmol/L). After 48 h of treatment, cell viability was assessed using a CCK-8 assay kit (Biosharp, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell proliferation assay

HRMECs were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3,000 cells per well (five replicate wells per condition). After cell attachment, cultures were serum-starved overnight in endothelial basal medium. The following day, designated experimental groups were pretreated with 200 µmol/L NSC23766 for 10 min before stimulation with recombinant human VEGF165 (final concentration: 20 ng/mL; R&D Systems). The culture medium was refreshed every 48 h. After 4 days of treatment, cell viability was assessed using a CCK-8 assay kit (Biosharp, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with absorbance measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Wound healing assay

HRMECs were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured to confluence (three replicate wells per condition). Following overnight serum starvation, a uniform scratch wound was created in each well using a 200 µL sterile pipette tip. After removing detached cells with PBS washing, designated groups were pretreated with 200 µmol/L NSC23766 for 10 min prior to VEGF stimulation (20 ng/mL in growth factor-free EGM-2). Cells were continuously cultured in 1%FBS growth factor-free EGM-2 medium. Cell migration was monitored for 24 h, with images captured at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h time points using phase-contrast microscopy (Olympus, Japan). The wound closure area was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0, National Institutes of Health, USA).

Tube formation assay

The 96-well plates were pre-coated with 50 µL of Growth Factor Reduced Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning, NY, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. HRMECs were then seeded onto the coated plates at a density of 6,000 cells per well. Designated groups were pretreated with 200 µmol/L NSC23766 for 10 min prior to VEGF stimulation (20 ng/mL in growth factor-free EGM-2). After 6 h of incubation, tube formation was imaged by phase-contrast microscopy (Olympus, Japan). The tube length was quantitatively analyzed using the ImageJ Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin (Version 1.0).

Invasion assay

Cell invasion was evaluated using a transwell assay. The upper chambers were coated with Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel matrix (1:8 dilution in cold serum-free medium; Corning) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After matrix polymerization, HRMECs (30,000 cells/well) were suspended in growth factor-reduced EGM-2 medium without FBS and seeded in the upper chamber. The lower chambers contained: EGM-2 with 5% FBS, EGM-2 with 5% FBS + 20 ng/mL VEGF165, EGM-2 with 5% FBS + 200 µmol/L NSC23766, EGM-2 with 5% FBS + 20 ng/mL VEGF165 + 200 µmol/L NSC23766. Following 24 h incubation at 37 °C, transwell chamber was washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (10 min), the cells were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. non-invading cells were removed from the upper membrane surface using cotton swabs. Invaded cells on the lower surface were imaged under a microscope. Five random fields were selected and the numbers of invaded cells were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0, National Institutes of Health, USA).

Pull-down of active Rac1

Rac1 activity was measured using a Rac1 Activation Assay Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, HRMECs at 90% confluence were treated with either 20 ng/mL VEGF165 or 20 ng/mL + VEGF165 200 µmol/L NSC23766 for specified durations (0, 5, 10, 20, or 30 min). Cells were then lysed in 200 µL of Mg²⁺ lysis buffer (MLB). For input controls, 30 µL aliquots of lysate from each experimental group were mixed with 30 µL of 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiled for 5 min. The remaining lysates were incubated with 10 µg of PAK-1 PBD agarose beads (per 0.5 mL lysate) at 4 °C for 1 h with gentle agitation. After incubation, the agarose beads were collected by centrifugation at 7,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The beads were then washed three times with MLB buffer and finally resuspended in 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, followed by boiling for 5 min. Control samples were prepared by incubating lysates from untreated cells with either 100 µM GTPγS (positive control) or 1 mM GDP (negative control). Active GTP-bound Rac1 was detected by western blot analysis using anti-Rac1 antibody.

Immunofluorescence staining

HREMCs were seeded onto glass coverslips at a density of 2,000 cells/well and waited for 30 min allowed to adhere. After cell attachment, the medium was replaced with basal EGM-2 medium, followed by treatment with 20 ng/mL VEGF, 200 µmol/L NSC23766 or 20 ng/mL VEGF + 200 µmol/L NSC23766 for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min. Next, nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubating the cells with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h to stain F-actin, followed by three 5 min PBS washes. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1:100 dilution) for 5 min and washed again three times with PBS (5 min each). Finally, coverslips were sealed with anti-fluorescence quenching sealing tablets. F-actin was visualized and imaged using a confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan).

OIR mouse model

Six–eight-week-old C57BL/6J mice (male and female, weighing 20–25 g) were obtained from Hunan Silaike Jingda Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd (Hunan, China). Mice were paired at a 1:3 male-to-female ratio for pup production. To ensure adequate breastfeeding for each pup, litter sizes were standardized to six pups. Postnatal day 7 (P7) C57BL/6J mouse litters were exposed to hyperoxia (75 ± 2% oxygen) for 5 days until P12 and then returned to normoxia. At P17 (5 days post-normoxia), retinal vasculature was assessed by isolectin B4 (IB4) staining of whole-mount retinas. On P12, intravitreal injections were performed as follows: Pups were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Eyelids were gently separated with a sterile needle, pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide eye drops, and topical proparacaine was applied for additional ocular anesthesia. Using a microsurgical microscope (Olympus MVX10, Japan), 1 µL of either NSC23766 (200 µmol/mL) or PBS was delivered via a 34-gauge Hamilton needle. Post-injection, eyes were treated with triple antibiotic ointment (neomycin/polymyxin B/bacitracin). At P17, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and enucleated eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and the mice under 6 g were excluded from the experiments. Retinal whole mounts were incubated with IB4 at room temperature for 24 h, and images were acquired using an Olympus MVX10 MacroView microscope.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.1.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). For comparisons between two groups, an unpaired Student’s t-test was employed. For comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

200 µmol/L NSC23766 showed no cytotoxicity in HRMECs

To determine the non-cytotoxic concentration range of NSC23766 in HRMECs, we performed CCK-8 assays. The results showed that NSC23766 concentrations up to 200 µmol/L did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity, whereas concentrations exceeding 200 µmol/L significantly reduced cell viability (Fig. 1). Therefore, we selected 200 µmol/L NSC23766 for subsequent experiments, as this concentration effectively inhibited Rac1 activity while maintaining cell viability.

NSC23766 inhibited Rac1 activation upon VEGF165 stimulation

VEGF165 is a key mediator of RNV. To mimic RNV conditions in vitro, HRMECs were cultured in medium containing VEGF165. To investigate Rac1 activation under VEGF stimulation and the inhibitory effect of NSC23766, we measured Rac1 activity by assessing GTP-bound Rac1 levels in HRMECs treated with either VEGF165 (20 ng/mL) or VEGF165 + NSC23766 (200 µmol/L) at specific time points (0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min). The results demonstrated that VEGF165 stimulation increased the GTP-Rac1/total Rac1 ratio in a time-dependent manner, peaking at 20 min. Notably, NSC23766 treatment significantly attenuated the VEGF165-induced increase in GTP-Rac1/total Rac1 ratio (Fig. 2).

Effects of NSC23766 on GTP-Rac1 Expression in HRMECs with or without VEGF Stimulation. (A) Changes in GTP-Rac1 (activated Rac1) expression in HRMECs following VEGF stimulation (20 ng/mL) at different time points, and the inhibitory effect of NSC23766 on GTP-Rac1 levels under VEGF (50 ng/mL) stimulation (original blots are presented in Supplementary Material 1). (B) Quantification of GTP-Rac1 band intensity by Western blotting. (C) Quantification of Total-Rac1 band intensity by Western blotting. All values are displayed as mean ± SEM. ns: no significant difference, ***: P < 0.001, ****: P < 0.0001, unpaired t test between two groups; one-way ANOVA for more than two groups.

NSC23766 suppressed the VEGF-enhanced angiogenic capacity of HRMECs

Angiogenesis is characterized by enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion, and tube formation capacity of endothelial cells (ECs)18. To investigate the role of NSC23766 in RNV through Rac1 activity inhibition, this study examined NSC23766-induced alterations in HRMECs proliferation, migration, invasion, and tube formation capabilities. The results demonstrated that VEGF stimulation significantly enhanced HRMECs proliferation, migration, invasion, and tube formation capabilities compared to normal medium-treated controls. However, in HRMECs treated with VEGF + NSC23766, these VEGF-induced pro-angiogenic effects were suppressed. Additionally, HRMECs treated with NSC23766 alone also exhibited reduced angiogenic capacity relative to normal medium-treated controls (Fig. 3).

Effects of NSC23766 on proliferation, migration, invasion and tube formation of HRMECs with or without VEGF Stimulation. (A) Quantification of cell proliferation by CCK-8 assay, assessing the effect of NSC23766 on HRMECs proliferation. (B) Representative images of wound healing assays in HRMECs at 0, 12, and 24 h. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Representative images of transwell assays in HRMECs. Scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Representative images of tube formation in HRMECs treated with NSC23766. Scale bar: 200 μm. (E) Quantification of wound closure rate (%) and statistical analysis. (F) Quantification and statistical analysis of invaded HRMECs. (G) Quantification and statistical analysis of branching length in tube formation assays. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, ***: P < 0.001, ****: P < 0.0001, multiple-group comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Rac1 activity regulates cytoskeletal rearrangement in HRMECs through the LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway

Rac1 has been reported to regulate cytoskeletal rearrangement and lamellipodia formation in cells through the LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway, processes that mediate cellular migration and invasion capabilities19. To investigate Rac1-mediated cytoskeletal alterations in HRMECs, we performed immunofluorescence staining using RITC-labeled phalloidin to visualize F-actin, followed by confocal microscopy imaging. The results revealed that in control HRMECs (normal medium treatment), F-actin was primarily localized at the cell membrane, with minimal cytoplasmic distribution. VEGF165 stimulation significantly enhanced F-actin fluorescence intensity and induced prominent cytoplasmic redistribution. In contrast, NSC23766 treatment alone markedly reduced F-actin fluorescence compared to controls. Furthermore, co-treatment with VEGF165 and NSC23766 not only attenuated the VEGF-induced F-actin enhancement but also reversed the cytoplasmic F-actin accumulation observed with VEGF165 treatment alone (Fig. 4A, C).

To further elucidate the mechanism by which Rac1 regulates cytoskeletal rearrangement in HRMECs, we examined phosphorylation levels of LIMK and cofilin using Western blot analysis. The results demonstrated that VEGF165 stimulation significantly increased the ratios of p-LIMK/total LIMK and p-cofilin/total cofilin compared to normal medium-treated controls. Notably, NSC23766 treatment effectively reversed these VEGF165-induced increases in phosphorylation ratios (Fig. 4B, D, E).

NSC23766 suppressed VEGF165-induced cytoskeletal reorganization in HRMECs via the LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images showing F-actin staining (phalloidin, green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in HRMECs. White arrows indicate VEGF165-induced F-actin reorganization and its modulation by NSC23766 treatment. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) the Western blotting assays test the protein expression of p-LIMK, LIMK, p-cofilin, cofilin and β-actin in HRMECs after treatment with VEGF165 (20 ng/mL) for 10 min and NSC23766 (200 µmol/mL) (original blots are presented in Supplementary Material 1). (C) Quantification and statistical analysis of F-actin fluorescence intensity (green channel) in (A) (D) Quantification and statistical analysis of Western blot band intensities for p-LIMK/total LIMK ratio are shown in (B) (E) Quantification and statistical analysis of Western blot band intensities for p-cofilin/total cofilin ratio are shown in B. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, ***: P < 0.001, multiple-group comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Rac1 activity modulates VEGF165-induced phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Y1175 in HRMECs

Phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Y1175 represents a key mechanism in RNV pathogenesis9. Previous experiments in our study have demonstrated that VEGF165 activates both Rac1 and VEGFR2 in a time-dependent manner to regulate the angiogenic capacity of HRMECs. To further investigate Rac1’s regulatory role in RNV, we examined VEGFR2 phosphorylation status in HRMECs using Western blot analysis following NSC23766 treatment. Our results demonstrated that VEGF165 significantly upregulated p-VEGFR2 (Y1175) levels, while Rac1 activity inhibition with NSC23766 effectively attenuated this VEGF-induced phosphorylation (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that Rac1 activity is required for VEGF165-mediated VEGFR2 phosphorylation at Y1175.

NSC23766 suppressed VEGF165-induced phosphorylation of VEGFR2 (Y1175) in HRMECs. (A) the Western blotting assays test the protein expression of p-VEGFR2 (Y1175), VEGFR2 and β-actin in HRMECs after treatment with VEGF165 (20 ng/mL) for 10 min and NSC23766 (200 µmol/mL) (original blots are presented in Supplementary Material 1). (B) Quantification and statistical analysis of Western blot band intensities for p-VEGFR2/total VEGFR2 ratio are shown in B. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, ****: P < 0.0001, multiple-group comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

NSC23766 suppressed RNV in the OIR mouse model

In vivo, the oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model was employed to evaluate the function of NSC23766 on RNV progression (Fig. 6A). The OIR model was successfully established, as evidenced by retinal whole-mount analysis: P12 OIR mice exhibited extensive central non-perfusion areas (Fig. 6B), while P17 OIR mice displayed significant pathological neovascularization (Fig. 6C). These characteristic phenotypic changes confirmed proper model establishment. In the OIR model, P12 mice received intravitreal administration of 1 µL NSC23766 (200 µmol/L). Retinal whole-mounts harvested at P17 were stained with isolectin B4 to assess retinal vasculature. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that NSC23766-treated OIR mice exhibited a reduction in pathological neovascular areas and avascular areas compared to PBS-injected controls (Fig. 7). These findings establish Rac1 activation as a critical driver of pathological RNV, and identify NSC23766-mediated Rac1 inhibition as a promising therapeutic strategy for RNV.

Schematic of generating OIR mouse model. (A) C57BL/6J mouse litters (P7) were exposed to hyperoxia (75 ± 2% oxygen) for 5 days until P12, followed by return to normoxia. NSC23766 was administered via intravitreal injection at P12. (B) The P12 mouse presented extensive non-perfusion areas. (C) The P17 mouse exhibited extensive pathological neovascularization. (Created in https://BioRender.com) (The results of the retinal whole-mount analysis are described in the Supplementary Materials.)

Effect of NSC23766 on Retinal Neovascularization in the OIR Mouse Model. (A) IB4 staining of retinal whole mounts from OIR treated with NSC23766 and PBS, withe areas indicate the pathological neovascularization (NV) areas and avascular areas. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Quantification and statistical analysis of NV area in OIR mouse treated with NSC23766 and PBS. (C) Quantification and statistical analysis of Avascular area in OIR mouse treated with NSC23766 and PBS. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **: P < 0.01, ****: P < 0.0001, two group comparisons were analyzed by unpaired t test.

Discussion

The VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway represents a primary mechanism driving RNV, establishing anti-VEGF therapy as the first-line treatment. However, approximately 40% of patients exhibit limited response to anti-VEGF agents20. Consequently, targeting alternative pathogenic cytokines has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for patients who show no response to anti-VEGF treatments. Alternative therapeutic approaches targeting cytokines such as angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) which activates the TIE-2 signaling pathway to reduce vascular permeability in RNV21 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)22,23. However, preclinical studies suggest these strategies have not demonstrated superior efficacy compared to conventional anti-VEGF therapies. Rac1 plays a pivotal role in cellular biological functions13 and participates in angiogenesis through multiple signaling pathways, including DLL4/NOTCH, YAP/TAZ, and NOX/ROS signaling24,25,26,27,28. However, the precise function and molecular mechanisms of Rac1 in RNV progression remain incompletely understood.

In this study, we elucidated the functional role and molecular mechanism of Rac1 activity in HRMECs and its contribution to RNV progression. As a member of the Rho GTPase protein family, Rac1 is ubiquitously expressed in various cell types and mediates lamellipodia formation during cell migration. HRMECs play a pivotal role in RNV pathogenesis, where enhanced HRMECs migration serves as a promoting factor for neovascularization. Given that VEGF is a key mediator of RNV, we stimulated HRMECs with VEGF165 in vitro to recapitulate the pathological angiogenesis observed in RNV. We demonstrated that VEGF165 stimulation significantly enhanced HRMECs migration. However, treatment with NSC23766, a selective Rac1-GEF interaction inhibitor, suppressed this VEGF165-induced migratory response. Previous studies have demonstrated that Rac1 mediates tumor cell migration and metastasis29. Waldeck-Weiermair et al. reported that Rac1 knockdown in endothelial cells (ECs) also inhibits ECs migration30. Our results corroborate these observations, indicating that VEGF-induced HRMECs migration occurs in a Rac1-dependent manner. Beyond characterizing Rac1’s function in VEGF-induced HRMECs migration, we systematically evaluated its contributions to three others critical angiogenic processes: cell proliferation, Matrigel invasion, and tube formation capacity. Our results demonstrated that VEGF165 significantly enhanced HRMECs proliferation, invasion, and tube formation capacity. Notably, NSC23766 treatment effectively reversed these VEGF165-induced angiogenic effects. Rac1 has been reported to regulate cellular proliferation and invasion in various tumor cells. Specifically, Matsumura et al. demonstrated that Rac1 promotes tumor proliferation in multiple myeloma via a p53-independent pathway, where Rac1 inhibition suppresses cell cycle progression and induces tumor cell apoptosis31. Similarly, in mammary epithelial cells, Rac1 has been shown to facilitate G1-phase progression through cyclin D1 upregulation32. Cell invasion capability depends on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-mediated degradation of the extracellular matrix. Zhou et al. demonstrated that reduced Rac1 activity downregulates MMP-9 expression in colorectal cancer, consequently suppressing tumor cell invasiveness33. Furthermore, Rac1 activity contributes to the invasive process of choroidal vessels into the retina34. However, the role of Rac1 in HRMECs remains poorly characterized. In this study, we demonstrate that Rac1 activity is essential for mediating the angiogenic functions of HRMECs, including migration, proliferation, invasion, and tube formation. Notably, pharmacological inhibition of Rac1 using NSC23766 effectively attenuates VEGF-induced enhancement of these angiogenic processes.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Rac1 regulates cytoskeletal reorganization through the LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway. Cofilin, which depolymerizes actin filaments to prevent cytoskeletal assembly, is inactivated when phosphorylated by LIMK. Rac1-activated LIMK phosphorylates cofilin, thereby promoting cytoskeletal formation35,36. To examine Rac1-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization in HRMECs, we performed fluorescence staining using RITC-labeled phalloidin to visualize F-actin. Our results demonstrated that VEGF165 stimulation significantly increased F-actin fluorescence intensity and induced marked cytoplasmic redistribution. Notably, NSC23766 treatment effectively inhibited these VEGF165-induced alterations in F-actin organization. Furthermore, Western blot analysis revealed that NSC23766 significantly attenuated VEGF165-induced phosphorylation of both LIMK and cofilin in this study. Therefore, we propose that Rac1 mediates VEGF-induced cytoskeletal reorganization in HRMECs. In our previous study, we observed that Rac1 activation induced the formation of flat pseudopodia at one edge of retinal pigment epithelial cells37. However, this distinct morphological change was not evident in HRMECs, potentially due to cell type-specific differences or insufficient observation duration.

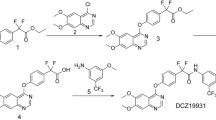

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of Rac1 in angiogenesis of HRMECs. (Created in https://BioRender.com)

VEGFR2 serves as the primary receptor in ECs, and phosphorylation at its Y1175 residue activates downstream signaling pathways (including Erk/MAPK and PI3K/AKT) to promote angiogenesis7. To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which Rac1 regulates VEGF165-induced angiogenesis, we performed Western blot analysis to examine the relationship between Rac1 and VEGFR2. Our results demonstrated that NSC23766 significantly inhibited VEGF165-induced phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Y1175, indicating that Rac1 activity plays an essential role in VEGF-mediated VEGFR2 activation. Lai et al. demonstrated that Rac1 knockdown using shRNA in tumor models downregulated VEGF and HIF-2α expression, consequently suppressing tumor angiogenesis38, However, whether Rac1 activity influences VEGFR2 phosphorylation levels remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that Rac1 activity modulates VEGF-induced VEGFR2 phosphorylation in HRMECs. Previous studies have reported that VEGF/VEGFR2 activates Rac1 through Vav2, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)39, Our results further demonstrated that VEGF activates Rac1 in a time-dependent manner. Collectively, these findings support the existence of a positive feedback loop between Rac1 and VEGFR2, wherein VEGFR2 phosphorylation at Y1175 activates Rac1, which in turn enhances VEGFR2 phosphorylation. However, the precise molecular mechanism by which Rac1 regulates VEGFR2 phosphorylation remains unclear. Davila et al. demonstrated that Rac1 knockout results in perinuclear accumulation of VEGF-A, with minimal extracellular secretion, suggesting Rac1 plays a critical role in VEGF-A trafficking and release40, Rac1 also mediates reactive oxygen species (ROS) production through NADPH oxidase24. Current literature suggests that Rac1 may regulate VEGFR2 phosphorylation through coordinated control of both VEGF-A secretion and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation.

To functionally characterize Rac1’s contribution to RNV pathogenesis in vivo, we established an OIR mouse model. Our results demonstrated that intravitreal administration of NSC23766 significantly suppressed pathological angiogenesis and decreased avascular areas in OIR mice compared to control mice. The reduction in the avascular area by NSC23766 is attributed to its inhibition of pathological and ineffective neovascularization, which in turn promotes the repair and reperfusion of normal retinal blood vessels, ultimately leading to a decrease in the avascular areas. Tan et al. demonstrated that Rac1 knockdown in mouse embryos resulted in mid-gestational lethality, with Rac1-deficient embryos exhibiting severe major vascular malformations and complete absence of small branching vessels41. Similarly, Mohammad et al. reported that inhibition of Vav2, a Rac1-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), induced retinal capillary cell damage and subsequent vascular leakage in the retina42. Nohata et al. performed endothelial-specific Rac1 knockdown in mice, observed significantly delayed retinal vascular development at 8 weeks compared to wild-type controls17. Collectively, these studies establish Rac1 as a crucial regulator of physiological vascular development. However, its role in pathological RNV remains unexplored. Our findings demonstrate that Rac1 inhibition effectively suppresses pathological RNV formation. Furthermore, NSC23766 may represent a potential therapeutic adjunct to anti-VEGF treatment for progressive RNV disorders.

In summary, this study demonstrates that Rac1 mediates angiogenesis by promoting proliferation, migration, invasion, and tube formation in VEGF-stimulated HRMECs in vitro. Rac1 also regulates actin cytoskeletal reorganization via upregulation of the LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway. Furthermore, we identified a positive feedback loop between VEGFR2 and Rac1, wherein VEGF/VEGFR2-induced Rac1 activation potentiates VEGFR2 signaling to amplify angiogenic responses (Fig. 8). Importantly, using an OIR mouse model, we established the critical role of Rac1 in pathological RNV. These findings collectively suggest Rac1 as a promising therapeutic target for RNV diseases. This study also has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the precise molecular mechanism by which Rac1 regulates VEGFR2 phosphorylation remains unclear, computational methods are a valuable tool for gaining mechanistic insights in future studies43. Second, the potential side effects of NSC23766 as a therapeutic intervention for RNV require further investigation. Third, the comparative efficacy between Rac1 inhibition and anti-VEGF therapy has not been conclusively established.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chan-Ling, T. et al. Pathophysiology, screening and treatment of ROP: A multi-disciplinary perspective. Prog Retin Eye Res. 62, 77–119 (2018).

Fleckenstein, M., Schmitz-Valckenberg, S. & Chakravarthy, U. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Rev. Jama 331, 147–157. (2024).

Stitt, A. W. et al. The progress in Understanding and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 51, 156–186 (2016).

Wallsh, J. O. & Gallemore, R. P. Anti-VEGF-Resistant retinal diseases: A review of the latest treatment options. Cells 10 (2021).

Naito, H., Iba, T. & Takakura, N. Mechanisms of new blood-vessel formation and proliferative heterogeneity of endothelial cells. Int. Immunol. 32, 295–305 (2020).

Bai, W. et al. Targeting FSCN1 with an oral small-molecule inhibitor for treating ocular neovascularization. J. Transl Med. 21, 555 (2023).

Apte, R. S., Chen, D. S. & Ferrara, N. VEGF in signaling and disease: beyond discovery and development. Cell 176, 1248–1264 (2019).

Simons, M., Gordon, E. & Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 611–625 (2016).

Corti, F. & Simons, M. Modulation of VEGF receptor 2 signaling by protein phosphatases. Pharmacol. Res. 115, 107–123 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Targeting JAML promotes normalization of tumour blood vessels to antagonize tumour progression via FAK/SRC and VEGF/VEGFR2 signalling pathways. Life Sci. 368, 123474 (2025).

Yao, L. et al. Soluble E-cadherin contributes to inflammation in acute lung injury via VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling. Cell. Commun. Signal. 23, 113 (2025).

Uemura, A. & Fukushima, Y. Rho GTPases in retinal vascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021).

Bid, H. K. et al. RAC1: an emerging therapeutic option for targeting cancer angiogenesis and metastasis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 1925–1934 (2013).

Saha, S. K. et al. KRT19 directly interacts with β-catenin/RAC1 complex to regulate NUMB-dependent NOTCH signaling pathway and breast cancer properties. Oncogene 36, 332–349 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. YAP/TAZ orchestrate VEGF signaling during developmental angiogenesis. Dev. Cell. 42, 462–478e7 (2017).

Marinković, G. et al. The Ins and outs of small GTPase Rac1 in the vasculature. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 354, 91–102 (2015).

Nohata, N. et al. Temporal-specific roles of Rac1 during vascular development and retinal angiogenesis. Dev. Biol. 411, 183–194 (2016).

Zeng, Z. et al. Genome editing VEGFA prevents corneal neovascularization in vivo. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 11, e2401710 (2024).

Prunier, C. et al. LIM kinases: Cofilin and beyond. Oncotarget 8, 41749–41763 (2017).

Lee, A. et al. Long-term outcomes of treat and extend regimen of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 15, 331–340 (2020).

Hussain, R. M. et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor antagonists: Promising players in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 15, 2653–2665 (2021).

Rosenfeld, P. J. & Feuer, W. J. Lessons from recent phase III trial failures: Don’t design phase III trials based on retrospective subgroup analyses from phase. II Trials Ophthalmol. 125, 1488–1491 (2018).

Puliafito, C. A. & Wykoff, C. C. Looking ahead in retinal disease management: Highlights of the 2019 angiogenesis, exudation and degeneration symposium. Int. J. Retina Vitreous. 5, 22 (2019).

Acevedo, A. & González-Billault, C. Crosstalk between Rac1-mediated actin regulation and ROS production. Free Radic Biol. Med. 116, 101–113 (2018).

Yousefian, M. et al. The natural phenolic compounds as modulators of NADPH oxidases in hypertension. Phytomedicine 55, 200–213 (2019).

Polacheck, W. J. et al. A non-canonical Notch complex regulates adherens junctions and vascular barrier function. Nature 552, 258–262 (2017).

Plouffe, S. W. et al. Characterization of Hippo pathway components by gene inactivation. Mol. Cell. 64, 993–1008 (2016).

Kuroiwa, D. A. K., Malerbi, F. K. & Regatieri, C. V. S. New. Insights Resistant Diabet. Macular Edema Ophthalmol. 244, 485–494. (2021).

Huilcaman, R. et al. Inclusion of ΑVβ3 integrin into extracellular vesicles in a caveolin-1 tyrosine-14- phosphorylation dependent manner and subsequent transfer to recipient melanoma cells promotes migration, invasion and metastasis. Cell. Commun. Signal. 23, 139 (2025).

Waldeck-Weiermair, M. et al. An essential role for EROS in redox-dependent endothelial signal transduction. Redox Biol. 73, 103214 (2024).

Matsumura, I. et al. Role of Rac1 in p53-Related proliferation and drug sensitivity in multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 17. (2025).

Klein, E. A. et al. Joint requirement for Rac and ERK activities underlies the mid-G1 phase induction of Cyclin D1 and S phase entry in both epithelial and mesenchymal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30911–30918 (2008).

Zhou, K. et al. RAC1-GTP promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion of colorectal cancer by activation of STAT3. Lab. Invest. 98, 989–998 (2018).

Ramshekar, A., Wang, H. & Hartnett, M. E. Regulation of Rac1 activation in choroidal endothelial cells: Insights into mechanisms in Age-Related macular degeneration. Cells 10 (2021).

Bu, F. et al. Activation of endothelial ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) improves post-stroke recovery and angiogenesis via activating Pak1 in mice. Exp. Neurol. 322, 113059 (2019).

Alhadidi, Q., Bin Sayeed, M. S. & Shah, Z. A. Cofilin as a promising therapeutic target for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 7, 33–41 (2016).

Huang, X. G. et al. Rac1 modulates the vitreous-induced plasticity of mesenchymal movement in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 41, 779–787 (2013).

Lai, Y. J. et al. Small G protein Rac GTPases regulate the maintenance of glioblastoma stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 8, 18031–18049 (2017).

Abe, K. et al. Vav2 is an activator of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10141–10149 (2000).

Davila, J. et al. Rac1 regulates endometrial secretory function to control placental development. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005458 (2015).

Tan, W. et al. An essential role for Rac1 in endothelial cell function and vascular development. Faseb j. 22, 1829–1838 (2008).

Mohammad, G. et al. Functional regulation of an oxidative stress Mediator, Rac1, in diabetic retinopathy. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 8643–8655 (2019).

Daroch, A., Purohit, R. & MDbDMRP A novel molecular descriptor-based computational model to identify drug-miRNA relationships. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 287, 138580 .(2025)s.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant/Award Number: 82160199). The project supported by Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund [ZDKJ2021038].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. J. T. and X. H. designed the experiments for the work. J. T., D. L., G. Y., H. L. and W. L. conducted experiments and acquired the data. J. T. and Y. L. looked after the software. Y. H. and X. H. provided the resources for the work. Y. H. and X. H. supervised the research. J. T., Y. H. and X. H. reviewed and edited the manuscript. J. T. and D. L. did the project administration. Y. H. and X. H. took care of the funding acquisition for the work. All authors agreed to the final manuscript version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosure

Permission to reproduce material from other sources: No materials reproduced from other sources are included in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

All experiments involving animals in this study were conducted according to the ethical policies and procedures approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University (Protocol number: HYLL-2021-132). The authors confirm that this study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J., Li, D., Yang, G. et al. NSC23766 effectively inhibited retinal neovascularization by disrupting the positive feedback loop between Rac1 and VEGFR2. Sci Rep 15, 40931 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24830-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24830-x