Abstract

Comprehensive studies on the acute toxicity and safety profiles of therapeutic doses of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP in the bone tissue and bone marrow of animals are limited, particularly when 166Ho produced in low-power reactors is used. These bone-specific complexes were synthesized through the coordination of 166Ho3+ ions in a neutral buffer. Acute toxicity studies were conducted at a dose of 1850 MBq/kg over 14 days, whereas safety assessments were performed at therapeutic doses of 18.5, 37, and 74 MBq/kg over 30 days in ICR mice. Hematological, biochemical, and histopathological toxicities were evaluated. 166Ho was obtained with high specific activities and radionuclide purity. These radiolabeled ligands were prepared with high radiochemical purity. No unexpected acute toxicity was observed. In the study groups, there were no significant signs of toxicity in the hematological, biochemical, or histopathological evaluations. However, a minimal reduction in osteocytes and osteoblasts in the bone marrow was noted. Notably, densely active hematopoiesis and progenitor clusters, including megakaryocytes, myeloblasts, and lymphoblasts, were observed in the bone marrow of the femurs and sternums. These findings provide valuable insights into the safety profiles of these radiolabeled ligands for bone and bone marrow, supporting further preclinical evaluations and domestic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of cancer is steadily increasing. According to Globocan 2022, there are an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer-related deaths worldwide1. Bone metastasis is a significant concern and occurs in 70–80% of all cancers, including breast, prostate, thyroid, lung, and kidney cancers; malignant melanoma; and head and neck, gastrointestinal, and ovarian cancers2,3,4. Bone metastases are often accompanied by pain due to complications such as bone destruction and cancer cell invasion5. The various treatment methods for bone metastases include chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiotherapy, bisphosphonates, and pain-relief medications6,7,8. Radiopharmaceutical-based cancer treatment is a relatively new therapeutic approach that is gaining recognition and commercial acceptance9.

For pain relief in patients with bone metastases, radiopharmaceutical therapy that directly targets metastatic bone damage is effective and widely applied clinically. To reach these damaged areas, radionuclides need to be attached to phosphonates2,10. EDTMP (ethylene-diamine-tetramethylene phosphonic acid) and DOTMP (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetramethylene phosphonate) are ligands that form coordination bonds with metal radioactive isotopes and localize on endosteal bone, where they are absorbed into the bone marrow endosteal11,12. To date, there are numerous reports on the use of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP for treating pain from bone metastases and for bone marrow treatment in patients with multiple myelomas. Notable examples include studies by Bayouth et al., Joseph et al., and Ueno et al., as well as other clinical trials, such as NTC00039754 and NCT000082298,11–16. In the past decade, several clinical reports have focused on radioactive drugs such as 32P, 89SrCl2, 153Sm-EDTMP, 153Sm-DOTMP, 177Lu-EDTMP, and 166Ho-DOTMP11,16,17. In addition, the radioactive beta-emitting isotopes used to treat bone pain include 32P, 89Sr, 166Ho, 153Sm, 177Lu, and 143Pr, along with alpha-emitting radioisotopes such as 223Ra, 211At, and 225Ac10,17,18,19.

166Ho is a radioactive isotope with many advantages due to its beta emission, with energies of 1.85 MeV (51%) and 1.77 MeV (48%). Additionally, 166Ho emits gamma rays with an energy of 80 keV (6.2%) and has a half-life of 26.8 h, making it suitable for imaging and treatment monitoring8,13,20. Furthermore, the emission range of β− from 166Ho in tissues is 2 mm, with a maximum depth of 10.2 mm21. Despite their advantages, few commercial products are available; for example, 166Ho-Scout microspheres are used for liver cancer treatment in Europe, and 166Ho-Chitosan is approved for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy in Korea16. 166Ho forms stable complexes with EDTMP and DOTMP, showing high stability in both in vitro and in vivo studies22,23. Owing to its rapid concentration in bones, fast clearance from the blood, and minimal retention in soft tissues, its toxicity is minimal15. For the applications similar to 153Sm-EDTMP (Lexidronam), which has been FDA-approved since 1997 but is difficult to import due to its 1.9-day half-life and high cost11, the domestic production of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP is appropriate and beneficial for local patients as a complementary alternative. In addition, 166Ho’s higher energy (Eβmean 0.66 MeV vs. 0.22 MeV for 153Sm) enhances therapeutic efficacy, requiring lower doses compared to 153Sm, which may benefit patients needing repeated treatments21. Besides, 89SrCl2 (approved as Metastron) has also been widely used for bone pain palliation, demonstrating clinical pain response rates comparable to 153Sm-EDTMP20. On the other hand, 166Ho-based radiopharmaceuticals provide better imaging quality in SPECT because it is within the optimal energy range for gamma camera detection, has less scatter, and allows for better dosimetry calculations24. 166Ho can be produced in a moderate-flux research reactor, whereas 153Sm requires a high-flux reactor, making labelled 166Ho more accessible in countries without high-flux neutron sources21.

While many clinical studies have been conducted on these labeled compounds in humans, a comprehensive preclinical safety evaluation in animals is lacking. To support regulatory drug registration, in this study, we meticulously investigated the production method of 166Ho using a local nuclear reactor, labeled it with ligands to prepare 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP, and performed quality control and preclinical evaluations, including assessments of acute radiotoxicity and safety assessment in animal tissues and bone marrow.

Results

Characterization of 166Ho, 166Ho-EDTMP, and 166Ho-DOTMP.

The 166Ho radionuclide was produced in-house as 166HoCl3. The spectra revealed gamma emission at 80.6 keV (6.2%) and 1379.4 keV (0.9%), along with X-rays at 48.2 keV (2.8%) and 49.1 keV (5.0%)13. 166Ho emits high-energy beta particles with maximum energies (Eβmax) of 1854 keV and 1774 keV, making it suitable for radionuclide therapy16, as shown in Fig. 1a. The radionuclide purity of 166Ho exceeded 99.9%. The radioactivity of the obtained 166HoCl3 solution was 19.70 ± 1.44 GBq/mL (0.264 mM/mL) using a Capintec ISOMED 2000 (USA). The specific activity of 166HoCl3 was 451.44 ± 33.53 MBq/mg, with a radiochemical purity of 99.62 ± 0.34 at calibration and experimentation (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1a&b). EDTMP and DOTMP were labeled with 166Ho under optimized conditions21,22, including a molar ratio of 20:1 for EDTMP and 30:1 for DOTMP, pH 7.0, a 15-minute reaction time, and room temperature, which are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The radiochemical purities of 166Ho-EDTMP (Fig. 1b) and 166Ho-DOTMP (Fig. 1c) were greater than 98%. Both complexes demonstrated stability in 0.9% NaCl, 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and 0.05% HSA, as shown in Fig. S1c&d. The EDTMP and DOTMP molecules contain four oxygen atoms in phosphonate groups and nitrogen atoms in amine groups, which participate in complexation with 166Ho10, as shown in Fig. 1d. Detailed characterization of the preparation batches revealed that the concentrations of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP were 372.3 ± 2.3 MBq/mL and 374.6 ± 3.7 MBq/mL, respectively. Their radiochemical purities were 99.10 ± 0.55% and 99.35 ± 0.35%, with specific activities of 8.55 ± 0.62 and 4.53 ± 0.33 MBq/mg, respectively. At molar ratios of 1:20 and 1:30, together with mean efficacies of 99.10% and 99.35%, the average number of holmium atoms per EDTMP or DOTMP molecule was estimated to be 0.0495 and 0.0331, respectively, similar to the calculation method for 90Y/131I25,26, as shown in Table 1. This 3–5% ratio may reduce the risk of bone marrow toxicity from the high-energy beta emission of 166Ho. The abovementioned results confirm the high radiochemical purity, stability, and specific activity of radiolabeled 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP.

Characterization of 166Ho, 166Ho-EDTMP, and 166Ho-DOTMP. (a) Energy spectrum of 166Ho, gamma photons with 80 keV and 1379 keV, and X-rays with 48.2, 49.1 and 55.48 keV (low-energy gamma). (b, c) Radiochemical purities of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP were determined via PC using Whatman No. 1 paper as the stationary phase and ammonia: methanol: water (1:10:20, v/v/v) as the mobile phase, and radioautography. Chromatograms were analyzed via OptiQuant 5 software; 166Ho remained at the origin, Rf = 0.0–0.25, and 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP migrated to the front, Rf = 0.75–1.00. (d) Hypothetical chemical structures of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP.

Acute radiotoxicity results

Body weight changes

We administered a single dose of 37.0 MBq of either 166Ho-EDTMP or 166Ho-DOTMP to the mice. This dose corresponds to 100 times the normal therapeutic dose27, with specific activities of 9.02 MBq/mg and 4.77 MBq/mg, respectively. A significant weight increase was observed in the treated groups of both males and females, as shown in Supplementary Table S2. On Day 1, there were no significant differences in weight between the 166Ho-EDTMP- and 166Ho-DOTMP-injected groups (P > 0.05, row factor, P = 0.4274; ordinary two-way ANOVA). By Day 14, all the groups exhibited significant weight gain–with **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 in the control group and treated group, respectively–except for the female group injected with 166Ho-EDTMP (P = 0.0686, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test)28.

Hematological and biochemical analysis

In general, the hematological and biochemical parameters of the 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP groups at 24 h postinjection (p.i.) did not differ significantly from those of the control groups (P > 0.05, two-way ANOVA). On Day 14, the platelet count (PLT) in the 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP female groups was significantly lower than that in the control female groups (row factor: P = 0.0089; column factor: P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA). No significant differences were detected (P > 0.05) in cholesterol, albumin, or protein levels. A significant decrease in creatinine levels was noted in male and female mice injected with 166Ho-DOTMP on Day 14 (P = 0.0125 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) levels were significantly lower in the 166Ho-EDTMP group than in the control group (P = 0.0036), whereas the 166Ho-DOTMP group presented significantly higher levels than did the control group (P = 0.0007). Glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) levels in the 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP female groups were significantly lower than those in the control female group (P = 0.0059 and P = 0.0065, respectively). The results are presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3. These results may be associated with the mild hepatitis and tubulointerstitial nephritis observed in mice treated with 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP29.

Hematological (a) and biochemical (b) analysis on Day 14 after the injection of 0 (0.9% NaCl) or 1850 MBq/kg 166Ho-EDTMP or 166Ho-DOTMP. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, with n = 4–5 for each group. The group marked with an asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference compared with the corresponding control group (P < 0.05).

Histopathological analysis

In the treatment groups, no significant lesions, necrosis or malignancy were found in the mice injected with 166Ho-EDTMP or 166Ho-DOTMP.

Histological analysis of tissues from 60 mice on Day 1 revealed mild inflammatory changes in the livers of 4 out of 20 male mice in the 166Ho-EDTMP group. In the 166Ho-DOTMP group, mild reactive inflammation of liver tissues was observed in 4 out of 20 mice (3 males and 1 female). No abnormal histological findings were detected in the kidneys or spleen tissues, and no mice died during this period.

Histopathological examination of tissue samples from 30 mice on Day 14 revealed mild chronic hepatitis in 4 out of 10 mice (2 males and 2 females) in the 166Ho-EDTMP group. In the 166Ho-DOTMP group, 2 out of 10 mice (1 male and 1 female) exhibited tubulointerstitial nephritis. Hemorrhage and an increased density of macrophages were observed in the spleen of one female mouse treated with 166Ho-DOTMP (Fig. 3). Four mice, accounting for 4.4%, including 2 males injected with 166Ho-EDTMP and 1 male and 1 female injected with 166Ho-DOTMP, died during the experiment; however, no abnormalities were detected in their tissues. At a dose of 3.7 MBq per mouse, no histopathological differences were observed in the liver, kidneys, spleen, or femur across all groups during microscopic evaluation, except for mild hepatocyte inflammation and occasional hemorrhage in the kidneys and spleen in 1–2 mice on Day 14. Notably, no significant abnormalities were detected in the femurs.

Microscopy images of the liver, kidney, spleen and femur tissues of the mice in all the groups (n = 5) observed on Day 14 after 0.9% NaCl, 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP injection. Tissues were stained with H&E and imaged (on an Olympus microscope, DP74, magnification 400×). White arrow: mild liver inflammation and mild internephritis area. Gray arrow: mild necrotizing hepatitis and hemorrhage. Black arrow: macrophages.

Safety profile of mice injected with 166Ho-EDTMP or 166Ho-DOTMP for 30 days

Clinical observations

Five mice, accounting for 7.1% of the study population, died. This included three mice injected with 166Ho-EDTMP (one male at 37 MBq/kg, and one female and one male at 74 MBq/kg) and two mice injected with 166Ho-DOTMP (one male at 37 MBq/kg and one female at 74 MBq/kg). All remaining mice appeared healthy, were agile, and ate and drank normally. There were no unusual changes in appearance, behavior, or locomotor activity, and no clinical signs of toxicity were observed.

Body weight measurements

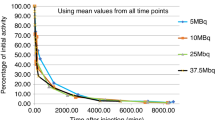

For the female groups injected with 166Ho-EDTMP, the initial body weights were recorded as follows: 19.88 ± 1.93 g (0.9% NaCl), 17.50 ± 1.67 g (18.5 MBq/kg), 16.84 ± 1.35 g (37 MBq/kg), and 21.16 ± 1.48 g (74 MBq/kg). On Day 30, the weights were 29.08 ± 4.72 g, 27.80 ± 6.57 g, 25.20 ± 3.19 g, and 25.57 ± 5.67 g, respectively. The difference in mean weight from the control group on Day 30 was not significant, except for the 37 MBq/kg group (P = 0.0015, two-way ANOVA). Similarly, for the male groups injected with 166Ho-EDTMP, the initial body weights were 22.30 ± 0.84 g, 21.96 ± 1.59 g, 24.40 ± 3.65 g, and 22.44 ± 1.76 g, respectively. On Day 30, the weights were 34.77 ± 3.26 g, 28.17 ± 7.71 g, 33.06 ± 6.67 g, and 28.70 ± 6.51 g, respectively. The differences from the control group were generally insignificant, except for the 18.5 MBq 166Ho-EDTMP group (P = 0.0383, two-way ANOVA), which is shown in Fig. 4a.

Body and spleen weight analysis of the mice on Day 30 after 0 (0.9% NaCl), 18.5, 37.0 and 74.0 MBq/kg 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP-injected doses, n = 4–5, mean ± SD. (a) Body weights of the mice in the 0.9% NaCl and 166Ho-EDTMP-injected groups. There were no significant differences in weight (P = 0.7255, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (b) Body weights of the mice in the 0.9% NaCl and 166Ho-DOTMP-injected groups. There were significant differences in weight decrease (P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA). (c) Spleen weights of the mice in the 0.9% NaCl, 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP-injected groups. There were no significant differences in spleen weight (P = 0.4010, two-way ANOVA).

For the female groups injected with 166Ho-DOTMP, the initial body weights were recorded as follows: 19.88 ± 1.93 g (0.9% NaCl), 23.36 ± 6.65 g (18.5 MBq/kg), 18.94 ± 2.81 g (37 MBq/kg), and 16.94 ± 0.94 g (74 MBq/kg). On Day 30, the weights were 29.08 ± 4.72 g, 25.32 ± 1.17 g, 24.15 ± 1.19 g, and 28.90 ± 6.55 g, respectively. The mean weight differences from those of the control group on Day 30 were not significant, except for those of the 18.5 MBq/kg group (P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA) and the 37 MBq/kg group (P = 0.0011, two-way ANOVA). Similarly, for the male groups treated with 166Ho-DOTMP, the initial body weights were 22.30 ± 0.84 g (0.9% NaCl), 22.36 ± 2.52 g (18.5 MBq/kg), 19.94 ± 2.88 g (37 MBq/kg), and 17.22 ± 0.47 g (74 MBq/kg). On Day 30, the weights were 34.77 ± 3.26 g, 24.30 ± 3.66 g, 29.54 ± 4.92 g, and 26.16 ± 2.30 g, respectively. Significant mean weight differences from those of the control group were observed in all treatment groups (P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA), as shown in Fig. 4b.

Spleen weight measurements

For the female groups injected with 0.9% NaCl and the three treatment groups, the spleen weights on Day 30 were 187 ± 62 mg, 117 ± 23 mg, 110 ± 25 mg, and 124 ± 36 mg (mean ± SD), respectively. The differences among the three treatment groups and the control female group were not significant, except for the NaCl group and the 37 MBq/kg 166Ho-EDTMP group, which presented a weight difference of 152.3 mg (P = 0.0213, two-way ANOVA). For the male groups injected with 0.9% NaCl and the three treatment groups, the initial spleen weights were 158 ± 75 mg, 108 ± 24 mg, 116 ± 14 mg, and 113 ± 23 mg (mean ± SD), respectively, as shown in Fig. 4c.

Hematological and biochemical parameters

The hematological parameters of the groups injected with radioactive substances were not significantly different from those of the control groups (P > 0.05). However, an increase in the white blood cell (WBC) count was noted in the male group receiving 37 MBq/kg 166Ho-EDTMP and the female group receiving 74 MBq/kg 166Ho-DOTMP, despite the P value being 0.6979 (ordinary one-way ANOVA). There was a significant increase in hematocrit (HCT) levels in the female groups receiving 37 and 74 MBq/kg 166Ho-DOTMP (P = 0.0411 and 0.0351, two-way ANOVA). Additionally, the PLT was significantly reduced in the 74 MBq/kg 166Ho-DOTMP male group (*P = 0.0092, two-way ANOVA). The results are shown in Table 2. Although there was a mild increase in HCT and a slight decrease in thrombocytopenia, this increase was observed only in one group. The levels of biochemical parameters, including GOT and GPT, in the radioactive-injected groups were not significantly different from those in the control groups, with P values of 0.3322 and 0.3579, respectively.

Histopathological findings

Tissues were examined using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, a standard technique for pathological analysis32. Microphotographs of the tissues collected from the mice on Day 30 revealed that, concerning liver pathology, no significant lesions, necrosis, or malignancies were present in either treatment group. However, mild reactive inflammation was observed in 15 out of 58 mice (25.8%) across both sexes in the treated groups (Fig. 5b and c). Similarly, the kidneys showed no significant lesions, although mild tubulointerstitial nephritis was detected in 11 out of 58 mice (18.9%), as shown in Fig. 5e and f. Moreover, the spleen tissue appeared normal, with balanced red and white pulp regions and normal vascular distribution (Fig. 5h and i). These findings suggest a potential tissue response to the treatments, with the specific doses administered correlating with the observed mild effects. In terms of the pathohistology of the femurs and sternums on Day 30, minimal to mild depletion of osteocytes and osteoblasts in the femurs (13 mice) and sternums (5 mice) of the 166Ho-EDTMP group, and in the femurs (10 mice) and sternums (7 mice) of the 166Ho-DOTMP group. Additionally, a few instances of peri-trabecular fibrosis at minimal levels were observed in three and two mice, respectively, as summarized in Table S4. The osteocytes were mostly healthy within their lacunae, showing no vacuolization or pyknotic nuclei. Osteoblasts at 400× magnification, which are not prominent along the trabecular or cortical bone, reflect reduced bone remodeling activity (Fig. 5k, l). In addition, there was dense hematopoietic cellularity in the bone marrow, as shown in Fig. 5 with a gray arrow.

Microscopy images of tissues from control and study mice, highlighting observations made 30 days after injection. The liver, kidney, spleen and decalcified bone tissues were stained with H&E and imaged via an Olympus microscope (DP74, 100× and 400× magnification). White arrow: mild inflammation in tissues. Gray arrow: depletion of osteoblasts. The black arrow indicates osseous lesions. Blue arrow: At 100× magnification, the bone marrow is densely populated with hematopoietic cells. Blue arrowheads: At 400× magnification, dense hematopoietic cellularity in the bone marrow was observed. (a) Liver tissue of male mice in the control group injected with 0.9% NaCl. (b) Liver tissue of female mice injected with 37 MBq/kg EDTMP. (c) Liver tissue from a male mouse injected with 37 MBq/kg DOTMP. (d) Kidney tissue from a male injected with 0.9% NaCl. (e) Kidney tissue from a female injected with 74 MBq/kg EDTMP. (f) Kidney tissue from a male injected with 74 MBq/kg DOTMP. (g) Spleen tissue from a male injected with 0.9% NaCl. (h) Spleen tissue from a male injected with 74 MBq/kg EDTMP. (i) Female spleen tissue injected with 74 MBq/kg DOTMP. (j) Femur tissue from a male injected with 0.9% NaCl. (k) Femur tissue from a male injected with 74 MBq/kg EDTMP. (l) Femur tissue, female, injected with 74 MBq/kg DOTMP. (m) Sternum tissue, male, injected with 0.9% NaCl. (n) Sternum tissue, female, injected with 37 MBq/kg EDTMP. (o) Sternum tissue, male, injected with 74 MBq/kg DOTMP.

In addition, the bone marrow in Fig. 6 shows active hematopoiesis, with no significant suppression or abnormalities. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, the sternal bone marrow was clearly identifiable and well preserved. The bone marrow areas exhibited large cells, with their density gradually increasing in correlation with the injection dose. Specifically, the percentages of these cells in the 166Ho-EDTMP-injected groups at doses of 18.5, 37, and 74 MBq/kg were 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. Similarly, the percentages of observed cells in the 166Ho-DOTMP-injected groups at doses of 18.5, 37, and 74 MBq were 10%, 15%, and 20%, respectively. These large cells may include megakaryocytes, lymphoblasts, and myeloblasts and are characterized by multilobulated nuclei containing 1–2 or 3–5 lobes, along with scant cytoplasm and round or slightly irregular shapes33,34. The cell nuclei appeared normal, without hyperchromasia or fragmentation, indicating an absence of radiation-induced apoptosis. Megakaryocytes were visible, suggesting preserved platelet precursor activity. No signs of infiltration by extramedullary cells were observed. Cancer metastases, osteoblastomas, osteofibromas, and osteosarcomas were not detected.

Microscopy images of the bone marrow from the femur and sternum, which represent bone tissues from the male and female groups (n = 5), injected with different doses of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP. Observations were made on Day 30 postinjection, with the tissues decalcified, H&E stained, and photomicrographed using an Olympus DP74 microscope at 400× magnification. White arrow: Megakaryocyte, a large hematopoietic cell characterized by a multilobed nucleus. Gray arrow: Lymphoblast cell, identified by its 1–2 nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and round or slightly irregular nucleus. Black arrow: Myeloblast cells, large hematopoietic precursor cells with scant cytoplasm, round or slightly irregular nuclei, fine chromatin, and 3–5 nucleoli.

These findings suggest that while the bone marrow remains functional and healthy, there might be slight suppression of osteoblast activity, possibly due to the radiopharmaceutical’s impact on bone remodeling processes.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the radiotoxic effects of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP on hematotoxicity and histology, particularly in the pathohistological analysis of femurs and sternums in ICR mice, revealed no significant abnormalities, although further investigation is needed.

We produced 166Ho in-house to ensure availability and reliability, because of its short half-life of only 26.8 h and the challenges of importation. Using neutron activation in a low-power reactor at a flux of 2.3 × 1013n/cm²/s, which is similar to the flux studied by Bayouth et al. and Bahrami-Samani et al.13,22, we successfully prepared 166Ho with a reasonably high specific activity of up to 2.84 GBq/mg Ho3+, and a holmium concentration of 0.264 mM, meeting the requirement of 2.42 mM as per the authors13,14. 166Ho is a promising radionuclide for theranostic applications because of its high-energy beta emission, which provides excellent therapeutic efficacy, and gamma emission, which is suitable for diagnostic imaging13,14,15,16. Additionally, the beta particles from 166Ho have a penetration depth of approximately 2.2 mm in soft tissue, with over 90% of the radiation deposited within tissues21. This characteristic enables targeted radiation delivery to the bone and bone marrow while sparing normal tissues15,16. The bone marrow receives β⁻ irradiation mainly from trabecular bone regions such as the femur, tibia, humerus, and skull, confirming that marrow dose primarily originates from bone-associated sources35. Liganded 166Ho emits β⁻ radiation delivering the highest dose within ~ 2 mm from the bone surface, decreasing at ~ 10 mm (~ 200–1000 cells)36. Owing to its short half-life governed by decay law N(t) = N₀e − λt, 166Ho limits radiation exposure to the bone marrow. Moreover, pain palliation efficacy depends not only on β⁻ penetration depth but also on energy deposition, biodistribution, and bone affinity. For example,166Ho, 188Re, 89Sr, 153Sm, and 177Lu, with β⁻ ranges of 10, 11, 8, 3, and 2 mm, have shown clinical pain response rates of 35–91%, 70–80%, 60–95%, 62–74%, and 77–95%, respectively8,10,16,37. Nevertheless, the potential risks should also be considered, including transient myelosuppression (reduced WBC or PLT counts) and localized dose heterogeneity within trabecular bone that may cause focal marrow exposure. The alternative radionuclides with lower β⁻ energy, such as 153Sm-EDTMP, 89Sr, or 177Lu-EDTMP, may offer safer and effective options for bone pain palliation, as summarized in Supplementary Table S5. The primary reason for selecting EDTMP and DOTMP in this study is their high affinity for inorganic salts in bones, such as calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite, which are specific to bone tissue. Secondly, they can be easily labeled with 166Ho10. Furthermore, the combination of 166Ho with EDTMP and DOTMP demonstrates high therapeutic efficiency in managing bone pain associated with metastatic bone disease21.

In terms of acute toxicity, we administered a dose of 37 MBq per mouse corresponds to a 117.8-fold increase over the minimum clinical dose (1.1 GBq/70 kg patient) used in prior studies15, which is consistent with the ICH M3(R2) guidelines for preclinical toxicology requiring high-dose safety margins. The ligands were used at 205 mg/kg (EDTMP) and 387 mg/kg (DOTMP), which remain within safe limits to 12.3-fold the clinical dose for NOAEL (No Observed Adverse Effect Level) in animals27. These doses did not lead to significant abnormalities in health, body weight, hematological or biochemical parameters, or severe organ damage. Minor changes, such as decreased platelet counts in the 166Ho-EDTMP group, increased creatinine levels, and variations in GOT and GPT levels, were noted in isolated cases and are expected to recover over time, similar to observations with 153Sm-EDTMP16. Histopathological analysis revealed mild chronic hepatitis and interstitial nephritis in the 14-day group, which is consistent with studies involving beta and alpha radionuclides such as 153Sm, 177Lu, 223Ra and 211At16,18,42. These findings align with the NOAEL criteria for safety pharmacology studies42.

During the 30-day observation period at therapeutic doses (18.5, 37, and 74 MBq/kg), no signs of bone marrow toxicity or health deterioration were observed in ICR mice. The doses used in the experiment were based on previous studies, such as 37 MBq/kg for 153Sm-EDTMP30 and 177Lu-EDTMP and 22.2 MBq/kg for 166Ho-DOTMP (Bayouth et al.)14. In our proposed therapeutic scheme, an activity of 18.5 MBq/kg, approximately half of the standard dose used for 153Sm-EDTMP, is expected to support the potential of 166Ho as a viable alternative for bone pain therapy. Compared with those treated with 166Ho-DOTMP, the weight gain of the mice treated with 166Ho-EDTMP was greater, suggesting a more favorable safety profile. All the treated groups presented a slight reduction in relative spleen weight, reflecting immune cell activity in response to the radiopharmaceuticals. Clinical studies with 153Sm-EDTMP have been reported to cause transient decreases in WBC (91–131 × 109/L) and hemoglobin (8.5–8.9 g/dL) during weeks 2–4 at 3.7–37 MBq/kg30,31. In contract, 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP maintained WBC (3.6–8.5 × 109/L), hemoglobin (12.5–15.1 g/dL), and PLT (545–787 × 109/L) within normal limits, confirming good systemic safety.

Histological analysis revealed reduced osteocytes and osteoblasts in the femurs and sternums, likely due to the effects of beta-irradiation on bone tissue43. At doses of 37–74 MBq/kg, these findings indicate mild and localized bone responses without irreversible damage. However, bone regeneration and proliferation were observed, indicating recovery. It is reasonable that the biological half-life of 166Ho-DOTMP is approximately 44 h, with a sevenfold greater concentration in trabecular bone than in cortical bone, which could explain the localized effects of radiation14.

Interestingly, bone marrow analysis revealed that large, round cells constituted approximately 30% of the marrow at a dose of 74 MBq/kg for 166Ho-EDTMP, whereas they constituted approximately 20% for 166Ho-DOTMP at the same dose. This difference is attributed to the absorption of 166Ho-EDTMP in the bone marrow of 166Ho-EDTMP being 3.47 times greater than that of 166Ho-DOTMP, as reported by Pedraza-Lopez et al.16. At 18.5 MBq/kg, the density of these cells was approximately 10%. The increase in dose correlated with a greater density of large cells, likely due to increased radiation absorption and marrow cell response43. Treatment of human multiple myeloma with 166Ho-DOTMP showed that the absorbed dose to red bone marrow and bone surface were 0.517 and 0.920 mGy/MBq, respectively (56%). In comparation, 153Sm-EDTMP injection, the absorbed dose ratio between red bone marrow and trabecular bone was 46% (1.86 and 2.32 mGy/MBq, respectively), while FDA data reported 1.54 and 6.76 mGy/MBq (23%), respectively12,30,46. The observed cells included megakaryocytes, lymphoblasts, and myeloblasts, their progenitors of lymphocytes, hematopoietic stem cells, progenitor cells and macrophages, which revealed that active hematopoiesis and hematopoietic precursors and megakaryocytes were preserved33. This may be explained by the significant fluctuation in PLT reduction in the high-dose 74 MBq/kg 166Ho-DOTMP injection group, as well as inflammatory rupture and the restoration of blood cells following the reduction processes in the early stages after radiopharmaceutical injection. This is also possibly due to radiolabeled compounds inducing molecular changes in the bone marrow microenvironment36. The drawbacks can be mitigated by leveraging the fact that bone marrow is not the dose-limiting organ, allowing repeated administrations at lower doses compared to 153Sm. Moreover, treatment with 166Ho has been shown to permit rapid recovery of both lymphoid and myeloid cell lineages38.

Importantly, no signs of abnormal proliferation, clustering, or tumors were detected, and no significant reductions in WBC, red blood cell (RBC), or PLT counts were detected. While H&E staining provided valuable insights, additional diagnostic methods, such as immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, cytological analysis, genetic testing, or special staining, are recommended for more precise identification of cell types and abnormalities32. In summary, histopathological findings confirmed mild, localized bone and marrow changes. 166Ho-DOTMP exhibited greater stability, less osteoblastic fibrosis, and better marrow preservation than 166Ho-EDTMP, supporting its potential as the preferred therapeutic candidate.

Methods

Ethics declarations

This study was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All animal care and experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the animal ethics committee of the Dalat Nuclear Research Institute and complied with the relevant guidelines for the care and use of animals. Animal experiments were performed following internationally recognized standards. The subjects were male and female ICR mice, aged 6–7 weeks, with albino coats sourced from the Ho Chi Minh City Biotechnology Center, Vietnam. The mice were housed in an environment with filtered air and maintained at a temperature of 22.05 ± 2.97 °C, a relative humidity of 55 ± 20%, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 8:00 a.m. and off at 8:00 p.m.). Food and water were provided according to the supplier’s guidelines.

Preparation of 166Ho, 166Ho-DOTMP, and 166Ho-DOTMP

166Ho was prepared in a custom nuclear reactor via a thermal neutron capture reaction 165Ho(n,γ)166Ho at a thermal neutron flux of 2.3 × 1013 n.cm− 2.s− 1 for a period of 100–132 h. To produce 166Ho, 200 mg of natural 165Ho (100% abundance, Sigma Aldrich, USA) in oxide form was irradiated, followed by a cooling period of 24 h. The irradiated 165Ho2O3 was then dissolved in 4.0 mL of 0.05 N HCl to obtain a 166HoCl3 solution10,13,21. The radioisotope 166Ho was identified using high-purity germanium (HPGe) gamma spectrometry (Dspec GC1518, Canberra, USA). The radioactivity of the solution was measured (Capintec, USA), and radiochemical purity was tested using paper chromatography (PC) (Advantec, Japan) on Whatman No.1 paper as the stationary phase using 10 mM DTPA (pH 4) and 10% ammonium acetate: methanol (1:1, v/v) as mobile phase. Radioactivity distribution on the chromatograms was analyzed using a radioautography system (Cyclone, PerkinElmer).To prepare 166Ho-EDTMP, as described previously10,21 with optimized results, 336 mg of EDTMP (TCI, Japan) was dissolved in 1.1 mL of 2 N NaOH, and distilled water was added to a final volume of 2.918 mL (pH 7.0, concentration 115.13 mg/mL or 0.264 mM/mL). Then, 146.0 µL of 166HoCl3 solution (3.025 MBq, ~ 6.371 mg Ho3+, 0.264 mM) was added, resulting in a 1:20 molar ratio. The mixture was incubated for 15 min at 24 °C. The radiochemical purity of 166Ho-EDTMP was tested via a PC using Whatman No. 1 paper as the stationary phase and ammonia: methanol: water (1:10:20, v/v/v) as the mobile phase, and the product was filtered through a 0.2 μm sterile filter (Sartorius, Germany). Similarly, to prepare 166Ho-DOTMP, 634 mg of DOTMP (BLD Pharma, China) was dissolved in 2.5 mL of 2 N NaOH, and distilled water was added to a final volume of 4.380 mL (pH 7.0). Then, 146.0 µL of 166HoCl3 solution was added, achieving a 1:30 molar ratio. The radiochemical purity of 166Ho-DOTMP was also tested using a PC10,22.

Acute toxicity tests

Acute toxicity testing was conducted in accordance with the single-dose toxicity test method outlined by the European Medicines Agency for the application of therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals16. The in vivo toxicology tests were performed in compliance with Good Laboratory Practice. Typically, 90 mice (45 males and 45 females, with a mean weight of 19.21 ± 1.99 g) were divided into three equal groups and fasted for 3 h prior to the experiment. The groups consisted of 30 saline-injected mice, 30 mice injected with 166Ho-EDTMP, and 30 mice injected with 166Ho-DOTMP. Each mouse received a dose of 100 µl of 166Ho-EDTMP or 166Ho-DOTMP (1850 MBq/kg; 37 MBq 166Ho; 4.10 mg of EDTMP or 7.75 mg of DOTMP) via tail vein injection. At 24 h postinjection, 10 animals of each sex were randomly selected for analysis, while the remaining 5 animals of each sex were assessed after 14 days. The body weights of the mice were measured. The mice were euthanized via a combination of ketamine and xylazine. Blood samples were collected for hematological analysis using a hematology analyzer (XN-1000, Sysmex, Japan) and for biochemical analysis via a biochemistry analyzer (AU 680, Beckman Coulter, Japan). Liver, kidney, spleen, and femur tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathological examination32,43.

Safety assessment of mice injected with 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP

We conducted a safety assessment on 70 male and female mice, with a mean weight of 20.37 ± 3.01 g, which were divided into seven groups of 10 mice each (5 males and 5 females). The intravenous injection consisted of seven doses, including 6 doses of 100 µl per mouse of 370 kBq 166Ho-EDTMP/166Ho-DOTMP (41.07 µg EDTMP/77.54 µg DOTMP), 740 kBq 166Ho-EDTMP/166Ho-DOTMP (82.14 µg EDTMP/155.08 µg DOTMP) and 1480 kBq 166Ho-EDTMP/166Ho-DOTMP (164.28 µg EDTMP/310.16 µg DOTMP), alongside one group receiving 100 µl of 0.9% saline per mouse.

The general health and body weight of the mice were monitored over 30 days. At the end of the study, the mice were euthanized using ketamine and xylazine. Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture and collected in EDTA tubes for analysis. The hematological and biochemical parameters measured included RBC, WBC, PLT, HCT, HGB, GOT, and GPT43,44. Tissue samples such as liver, kidney, spleen, sternum, and femur samples were collected, preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin blocks. The liver was collected from the largest lobes, and the spleen and kidneys were collected as whole organs. The femur included the articular cartilage, epiphysis, physis, and marrow cavity. Femurs and sternums were cleaned of muscles, ligaments, and tendons and then decalcified and embedded in paraffin. The longitudinally trimmed femoral and sternal samples were sectioned at 4.0 μm, stained with H&E, and examined under light microscopy magnification.

Bone lesions were observed according to the International Harmonization of Nomenclature and Diagnostic Criteria for Lesions in Rats and Mice criteria32. Histopathological diagnostics were conducted on the basis of expert observations, and the results were compared with those of controls. Histological observations were graded via a five-point scale45.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the means ± SDs or means ± SEMs, and a P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s or Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests, was used to analyze body weight and weight gain data. Student’s t test was used to estimate differences in body weight and hematological and biochemical parameters. Chromatograms were analyzed using OptiQuant 5 software.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrated that both 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP provide important data on acute radiotoxicity at high doses, particularly in bone tissue and bone marrow radiotoxicity observations at therapeutic doses. At a dose of 3.7 MBq per mouse, no acute toxicity was observed after 14 days of follow-up. Additionally, at doses ranging from 0.37 to 1.48 MBq per mouse, no indications of bone marrow toxicity or significant adverse effects were noted in ICR mice over 30 days. Notably, an increase in active hematopoiesis was observed in the bone marrow. While these results suggest minimal radiotoxicity, further studies are needed to optimize the formulation and assess long-term effects in both preclinical and clinical settings, particularly regarding pain relief in patients with bone metastases, where 166Ho may serve as an appropriate alternative palliative option.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.2183 (2024).

Yang, Z., Yue, Z., Ma, X. & Xu, Z. Calcium homeostasis: A potential vicious cycle of bone metastasis in breast cancers. Front. Oncol. 10 (293). https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00293 (2020).

Askari, E., Harsini, S., Vahidfar, N., Divband, G. & Sadeghi, R. 177 Lu-EDTMP for metastatic bone pain palliation: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 35, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1089/cbr.2020.4323 (2020).

Francisco, D. C. G. L., Adriana Alexandre, S., Tavaresb, A. A., S., G. M. & Tavares, J. M. R. Palliative treatment of metastatic bone pain with radiopharmaceuticals: a perspective beyond Strontium-89 and Samarium-153. Appl. Rad Isot. 110, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2016.01.003 (2016).

Mehlen, P. & Puisieux, A. Metastasis: a question of life or death. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1886 (2006).

Agarwal, K. K., Singla, S., Arora, G. & Bal, C. 177Lu-EDTMP for palliation of pain from bone metastasesin patients with prostate and breast cancer: a phase II study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 42, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-014-2862-z (2014).

Perez-Garcia, J., Munoz-Couselo, E. & Cortes, J. Bone metastases: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. EJC Suppl. 11, 254–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcsup.2013.07.035 (2013).

Manafi-Farid, R. et al. Targeted palliative radionuclide therapy for metastatic bone pain. J. Clin. Med. 9, 2622 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Carrier systems of radiopharmaceuticals and the application in cancer therapy. Cell. Death Discovery. 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-023-01778-3 (2024).

IAEA. Pain palliation of bone metastases: Production, quality control and dosimetry of radiopharmaceuticals. Radioisotopes Radiopharmaceuticals Ser. Technical Reports Series No. 9 (2023).

Anderson, P. & Nuñez, R. Samarium Lexidronam (153Sm-EDTMP): skeletal radiation for osteoblastic bone metastases and osteosarcoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 7 (11), 1517–1527 (2007).

Breitz, H. B. et al. 166Ho-DOTMP Radiation-Absorbed dose Estimation for skeletal targeted radiotherapy. J. Nucl. Med. 47, 534–542 (2006).

Bayouth, J. E. & Macey, D. J. Quantitative imaging of holmium-166 with an anger camera. Phys. Med. Bid. 39, 265–279 (1994).

Bayouth, J. E. et al. Pharmacokinetics, dosimetry and toxicity of holmium-166 DOTMP for bone marrow ablation in multiple myeloma. J. Nucl. Med. 36, 730–737 (1995).

Rajendran, J. G. et al. High-Dose 166Ho-DOTMP in myeloablative treatment of multiple myeloma: Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, and absorbed dose Estimation. J. Nucl. Med. 43 (10), 1383–1390 (2002).

Klaassen, N. J. et al. The various therapeutic applications of the medical isotope holmium-166: a narrative review. EJNMMI Radioph Chem. 4, 19 (2019).

Shirvani-Arani, S., Ranjbar, H. & Bahrami-Samani, A. Optimal production and purification of n.c.a.143Pr as a promising palliative agent for the treatment of metastatic bone pain. Sci. Rep. 14, 13483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64321-z (2024).

Sudo, H. T. et al. Preclinical evaluation of the acute radiotoxicity of the α-Emitting Molecular-Targeted therapeutic agent 211At-MABG for the treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma in normal mice. Transl Oncol. 12, 879–888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2019.04.008 (2019).

George, S., Lisa, B., Michael, R. M. & Jessie, R. N. Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: clinical advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 19, 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-020-0073-9 (2020).

Zimmerman, B. E. A new evaluation of the decay data for 166Ho. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 207, 111230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2024.111230 (2024).

Tan, H. Y. et al. Neutron-activated theranostic radionuclides for nuclear medicine. Nucl. Med. Biol. 90, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2020.09.005 (2020).

Bahrami-Samani, A. et al. Production, quality control and Pharmacokinetic studies of 166Ho-EDTMP for therapeutic applications. Sci. pharm. 78, 423–433 (2010).

Bagheri, R. et al. Production of Holmium-166 DOTMP: A promising agent for bone marrow ablation in hematologic malignancies. Iran. J. Nucl. Med. 19, 12–20 (2011).

Martina et al. Gamma camera characterization at high holmium-166 activity in liver radioembolization. EJNMMI Phys. 8, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-021-00372-9 (2021).

Nguyen, T. T. et al. Efficacy of nimotuzumab (hR3) conjugated with (131)I or (90)Y in laryngeal carcinoma xenograft mouse model. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 97, 704–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553002.2021.1889703 (2021).

Nguyen, T. M. C. et al. Safety assessment, radioiodination and preclinical evaluation of antinuclear antibody as novel medication for prostate cancer in mouse xenograft model. Scientifc Rep. 13, 18753 (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-45984-6

Koziorowski, J. et al. Position paper on requirements for toxicological studies in the specific case ofradiopharmaceuticals. EJNMMI Radioph Chem. 1, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41181-016-0004-6 (2016).

Assaad, H. I. et al. Rapid publication-ready MS-Word tables for two-way ANOVA. SpringerPlus 4, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0795-z (2015).

Joyce, E., Glasner, P., Ranganathan, S. & Swiatecka, A. Urban tubulointerstitial nephritis: diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Ped Nephr. 32, 577–587 (2017).

Sharma, S., Singh, B., Koul, A. & Mittal, B. R. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of 153Sm-EDTMP and 177Lu-EDTMP for bone pain palliation in patients with skeletal metastases: patients’ pain score analysis and personalized dosimetry. Front. Med. 4, 46–54 (2017).

Sartor, O. Overview of Samarium Sm-153 Lexidronam in the treatment of painful metastatic bone disease. Rev Urol. 6:S3–S12. PMCID: PMC1472939 (2004).

Fossey, S. et al. Nonproliferative and proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse skeletal tissues (Bones, Joints, and Teeth). J. Toxicol. Pathol. 29 (3), 49S–103S. https://doi.org/10.1293/tox.29.3S-2 (2016).

Sim, X., Poncz, M., Gadue, P. & French, D. L. Understanding platelet generation from megakaryocytes: implications for in vitro–derived platelets. Blood 127 (10), 1227–1233. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-08-607929 (2016).

Stone, A. P., Nascimento, T. F. & Barrachina, M. N. The bone marrow niche from the inside out: how megakaryocytes are shaped by and shape hematopoiesis. Blood 139, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021012827 (2022).

Dash, A. & Das, T. Production of therapeutic radionuclides for bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals to Meet clinical exigency and academic research. J. Radioanal Nucl. Chem. 334, 2591–2611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-025-10025-1 (2025).

Goldenberg, D. M., Sharkey, R. M., Barbet, J. & Chatal, J. F. Radioactive Antibodies: Selective Targeting and Treatment of Cancer and Other Diseases (World Scientific Publishing, 2007).

Bensinger, W. et al. 166Ho-DOTMP skeletal targeted radiotherapy with Melphalan and autologous stem cell support for multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 6656. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.22.90140.6656 (2014).

Bagheri, R., Bahrami-Samani, A. & Ghannadi-Maragheh, M. Estimation of radiation absorbed dose in man from 166Ho-EDTMP based on biodistribution data in Wistar rats. Rad Phys. Chem. 187, 109560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109560 (2021).

Sohaib, M., Ahmad, M., Jehangir, M. & Perveen, A. Ethylene Diamine tetramethylene phosphonic acid labeled with various β – Emitting radiometals: labeling optimization and animal biodistribution. Cancer Bioth Radioph 26 (2), (2011).

Garnuszek, P., Pawlak, D., Licinska, I. & Kaminska, A. Evaluation of a freeze-dried kit for DOTMP-based bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals. Appl. Rad Isot. 58, 481–488 (2003).

Alavi, M. et al. Metastatic bone pain palliation using 177Lu-ethylenediaminetetramethylene phosphonic acid. J. Nucl. Med. 2, 109–115 (2015).

Larsen, R. H., Saxtorph, H. & Skydsgaard, M. Radiotoxicity of the Alpha-emitting Bone-seeker 223Ra Injected Intravenously into Mice: Histology, Clinical Chemistry and Hematology. In vivo 20, 325–332 (2006).

Dams-Kozlowska, H. et al. Effects of designer Hyper-Interleukin 11 (H11) on hematopoiesis in myelosuppressed mice. PLoS ONE. 11, e0154520. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154520 (2016).

O’Connell, K. E. et al. Practical murine hematopathology: A comparative review and implications for research. Comp. Med. 65, 96–113 (2015).

Watanabe, A. et al. Specific pathologist responses for standard for exchange of nonclinical data (SEND). J. Toxicol. Pathol. 30, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1293/tox.2017-0019 (2017).

QUADRAMET®, P. & Information https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/020570s008lbl.pdf

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the project of the Vietnamese Ministry of Science and Technology, ĐTCB.09/23/VNCHN. Support was provided by the Nuclear Research Institute, Dalat City, Vietnam.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T.N. conceived the study design, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. H.H.Q.D. produced radioisotopes, performed radiolabeling and data analysis. T.K.G.N., T.N.N. and T.K.G.N. performed the radiolabeling, quality control and biological experiments. T.B.N and T.N.N. produced radioisotopes and performed radiolabeling. N.B.N.D., V.T.L. and H.N.Q.D. were involved in the biology data analysis and contributed to the animal models. N.D.T.L. and T.M.C.N. performed safety assessments and histopathology analysis. All the authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dang, H.H.Q., Nguyen, T.K.G., Nguyen, T.N. et al. Acute radiotoxicity studies and safety assessment of 166Ho-EDTMP and 166Ho-DOTMP for the palliative treatment of bone metastases. Sci Rep 15, 42305 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26098-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26098-7