Abstract

Aviation engines, as vital aircraft components, encounter challenges in Condition Monitoring (CM) signal fault diagnosis, including low accuracy and poor real-time performance. To tackle these, by integrating an Auto-Encoder (AE) and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU), this study proposes an AE-BiGRU-based fault signal feature extraction model for aviation engines. Then, an ISMA-SVM-based aviation engine CM signal fault diagnosis method is introduced, employing the Improved Slime Mould Algorithm (ISMA) to optimize Support Vector Machine (SVM) parameters. The findings reveal that in function optimization, the ISMA exhibits stronger variance reduction in both unimodal and multimodal functions, particularly in the latter. In terms of fault diagnosis, the model performs excellently in precision (0.90), recall (0.95), and F1 score (0.92), achieving the best performance in the C-MAPSS dataset prediction. Case applications show their advantages in extracting weak fault signals and identifying fault frequencies, enhancing aviation engine fault diagnosis, safeguarding health status, and aiding damage repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aircraft engines are the core components of airplanes, and their manufacturing capabilities reflect a country’s industrial and technological level as well as comprehensive national strength, which is crucial to national security and great power status. However, aircraft engines have complex structures and are composed of numerous precision components, making them prone to failure under harsh working conditions, and the failure modes are diverse1,2,3. Due to its long research cycle, high manufacturing difficulty, and wide range of industries involved, ensuring its health status is extremely important. In history, the maintenance of aircraft engines has gone through stages from post maintenance to regular preventive maintenance, but these solutions have problems such as low reliability, waste of manpower, and high maintenance costs4. Therefore, improving the maintenance strategy of aircraft engines is particularly urgent. In recent years, Prognostics Health Management (PHM) technology has shown significant value in the aviation industry of developed countries as an evolutionary direction for predictive maintenance paradigms. This technology can significantly reduce the life cycle cost of aircraft engines by accurately evaluating equipment status while simultaneously improving system reliability and operational safety. Its unique advantage lies in the ability to dynamically optimize maintenance decision cycles and spare parts configuration strategies. This characteristic has made it a research hotspot in military aircraft maintenance and management, and has been validated by defense departments of multiple countries, including the US military, demonstrating great potential for promoting innovation in aviation equipment support models5,6,7. PHM technology belongs to the discipline of systems engineering. The design of aviation PHM focuses on equipment safety, task completion rate, equipment integrity, and support costs, and can be divided into two main parts: fault diagnosis and health management8. However, with the continuous growth of technology, aviation engines are becoming increasingly intelligent and systematic. With the advancement of testing technology, the monitoring data of aircraft engine status are growing exponentially, and the corresponding PHM technology also needs to develop towards intelligence9,10. Many scholars have researched this issue.

To promote the health management of aviation engines, Fentaye A D et al. proposed a gas turbine fault detection method utilizing a modular convolutional neural network. The proposed method achieved an accuracy rate of over 96% in detecting and isolating multiple gas path faults. In addition, sharing diagnostic tasks with a modular architecture was considered to be associated with significantly improving diagnostic accuracy11. To address the trend of aircraft engine degradation, Wu J et al. proposed a fault diagnosis model for aircraft engines that integrates an improved bidirectional long short-term memory network and convolutional block attention. This model could be directly applied to raw monitoring data without the need for additional algorithms to extract fault degradation features. Comparative analysis with other models showed that the precision of classification was superior, which was practically meaningful for enhancing the reliability of aircraft engine operation and predicting remaining service life12. Given the importance of continuously improving aircraft engine diagnostic system algorithms, Pérez Ruiz J L et al. proposed a gas path monitoring and diagnostic framework. This framework was benchmarked using the propulsion diagnostic method developed by NASA. It utilized fleet mean and single-engine baseline models to calculate feature vectors. This method outperformed all other diagnostic solutions13. To promote the development of fault prediction technology, Arias Chao M et al. created a brand new real dataset. This dataset contained complete trajectory information of aircraft engines from normal operation to failure in real flight environments. In addition, the dataset al.so provided detailed annotations on the health status of the engine, including classification information for various fault categories14. To enhance the precision of Aircraft Engine Fault (AEF) diagnosis, Lu F et al. designed a hybrid extended Kalman filter. This filter was designed to detect engine performance abnormalities and adapt to sensor failures. This method could achieve real-time state estimation of aircraft engines in distributed systems with packet loss15. To improve the health management level of aircraft engines, Mallikarjuna PB et al. proposed two Deep Learning (DL) models to classify the state of gearboxes as advantages and disadvantages. These models were applied to the time and frequency domains of aircraft gearbox vibration data, using a publicly available dataset of aircraft gearbox vibration to assess the performance. Compared with the frequency domain, LSTM and Bi-LSTM have achieved highly reliable accuracy in the time domain and are suitable for health monitoring of aircraft gearbox systems16. To improve the intelligent fault diagnosis level of aircraft engines, Zhang K et al. proposed a DL-based method for diagnosing surge faults in aircraft engines based on the analysis of the surge mechanism. DL technology has shown good performance in diagnosing surge faults in aircraft engines, and this method achieved a classification accuracy of over 99% on the test set through network training17. To enhance the accuracy of industrial fault diagnosis, Ullah N et al. developed an innovative approach that combines advanced image processing techniques with machine learning methods for milling machine fault classification. The results demonstrated significant improvements in fault identification performance, outperforming existing state-of-the-art methods18. To improve the efficiency of high-precision tool fault diagnosis in industrial environments with limited data resources, Siddique M F et al. developed a hybrid fault diagnosis framework for milling tools based on the Canny edge detection algorithm. The results demonstrated that the framework achieved an accuracy rate of 99.78%, exhibited strong anti-noise interference capability, and maintained stable diagnostic performance under varying working conditions19. To reduce downtime and maintenance costs for centrifugal pumps, Siddique M F et al. proposed a fault diagnosis method combining wavelet coherence analysis with Stockwell transform histograms. The results showed that this approach achieved classification accuracy rates of 100%,99.86%, and 99.92% across different datasets, significantly outperforming traditional fault detection methods20.

In summary, although intelligent algorithms have made some progress in intelligent diagnosis and health management of aircraft engines, they still face multiple challenges. The primary issue is the high complexity of the algorithm, which affects its real-time performance. Secondly, the accuracy of identifying specific fault modes still needs to be improved, especially in the complex situation of multimodal composite faults. Furthermore, these algorithms have a strong dependence on data and perform poorly in robustness when faced with incomplete or noisy data. Finally, model training often needs numerous annotated data points as support. However, aircraft engine failure data are scarce and difficult to obtain. This situation seriously restricts the practical application of intelligent algorithms, which in turn affects the efficiency and accuracy of aircraft engine damage repair. Based on this, this study first proposes a fault signal feature extraction model for Condition Monitoring (CM) of aircraft engines based on AE-BiGRU, which combines Auto-Encoder (AE) and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU). Then, this study combines the Improved Slime Mold Algorithm (ISMA) with Support Vector Machine (SVM) as the classifier to propose a fault diagnosis method for Aircraft Engine CM Signals (AE-CMS) based on ISMA-SVM.

The novelty of the proposed method is demonstrated through three key aspects. (1) The dynamic fusion mechanism of AE-BiGRU: Unlike traditional approaches that employ fixed-weight concatenation between AEs and BiGRUs, this study introduces dynamically adjusted weight coefficients to continuously balance the fusion weights between temporal features (AE outputs) and dimensionality-reduction features (BiGRU outputs). This mechanism automatically enhances the importance of AE outputs in noisy signals while prioritizing BiGRU outputs in stable signals.(2) The collaborative optimization theory of ISMA: Traditional SMA contraction mechanisms often fall into local optima. By integrating Lévy flight dynamics with contraction formulas, this study improves position updates by leveraging Lévy flight’s long-tail characteristics to expand search space while retaining SMA’s local convergence advantages.(3) The innovative end-to-end framework: While existing methods typically separate feature extraction from parameter optimization, this study establishes an end-to-end architecture combining Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) denoising, AE-BiGRU features, ISMA classification, and SVM. The integrated loss function for feature extraction and parameter optimization achieves synergistic optimization, better meeting real-time diagnostic requirements in aero-engine applications.

This study aims to increase the precision and efficiency of AEF diagnosis, providing more reliable technical support for aircraft engine damage repair. In addition, this study also expands the application scope of ISMA, which can provide useful references and inspirations for fault diagnosis in other fields.

Methods and materials

Construction of AE-CMS feature extraction model based on AE-BIGRU

Aircraft engine CM is crucial for ensuring aviation safety, providing important data for refined maintenance and inventory management for aviation enterprises and manufacturers. The advancement of artificial intelligence technology has made engine fault prediction technology the core of prediction and health management systems, and it is undergoing systematic upgrades. However, the existing diagnostic system still faces multiple challenges, especially in complex working conditions where signal interference is significant, leading to the masking of feature information and becoming a technical challenge that restricts diagnostic accuracy. In practical applications, multi-source heterogeneous interference causes the health status information of devices in the original CM signal to be obscured by noise. This results in the collapse of feature space dimensions, reduces the distinguishability of fault features, and increases the risk of operation and maintenance decisions21. Therefore, this study uses the VMD algorithm to reconstruct the CM signal, improve signal quality, and eliminate interference information. The VMD algorithm reconstructs the original signal by minimizing the modal bandwidth and constraining the modal sum, achieving signal optimization as given by Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), u is the modal component, \(\omega\) is the frequency center of each individual component, and k is the number of modes. * denotes the convolution operation, \(\delta (t)\) denotes the Dirac δ function, j denotes the imaginary unit, and \({\partial _t}\) denotes the time derivative. The norm used in the formula is the L2 norm, i.e., the Euclidean norm. However, directly using VMD algorithm to analyze CM signals may affect diagnostic accuracy due to ignoring noise22. Therefore, this study adopts the Wavelet Thresholding (WT) method to denoise the signal in the wavelet domain. The expression of WT is shown in Eq. (2).

In Eq. (2), \(\psi (t)\) is the wavelet basis function, \(\tau\) means the translation, \(W{T_f}(a,\tau )\) is the wavelet coefficient, and a is the scaling. In the process of applying WT to denoise various Intrinsic Mode Function (IMF) components, this study further discusses the similarity between each IMF component and the original signal. By calculating the correlation coefficient between them, this similarity can be quantified. Subsequently, this study selects IMF components with high correlation coefficients with the original signal and uses these components to reconstruct the CM signal. This process achieves effective reconstruction of AE-CMSs based on VMD technology, as shown in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

After using VMD to select relevant IMF components to reconstruct AE-CMS, to solve the computational complexity, storage requirements, and feature redundancy problems caused by high dimensionality, this study uses AE for dimensionality reduction processing23,24. AE maps data to a hidden layer through an encoder to achieve lossy compression while preserving key features, and then reconstructs the output \({x_i}\) through a decoder. The training objective is to minimize the reconstruction error, and the resulting reconstruction error function L is shown in Eq. (3).

In Eq. (3), n is the dimension of the sample. Finally, by calculating the gradient of reconstruction error and applying the backpropagation algorithm to update network parameters, AE can learn the compressed representation of data, achieve data dimensionality reduction, and preserve important information. To improve the accuracy of feature extraction for CM signal fault signals, this study uses BiGRU to extract the internal temporal features of CM signals, and utilizes its bidirectional dependency relationship capture ability to enhance its feature extraction performance. The final output \({y_t}\) of BiGRU at time t is shown in Eq. (4).

In Eq. (4), \({x_t}\) denotes the initial input. \({\vec {h}_{t - 1}}\) and \({\mathop h\limits^{ \leftarrow } _{t+1}}\) are the hidden layer output during forward-propagation and backpropagation. \({W_a}\) and \({W_b}\) are their weights. \({b_t}\) and f are the bias term and activation function of the output layer. Finally, the study designs a dynamic fusion of AE and BiGRU. The calculation formula of dynamic weight \(\alpha\) is shown in Eq. (5).

In Eq. (5), x represents the input signal, while \({\left\| {x - AE(x)} \right\|_2}\) denotes the reconstruction error of the AE. When signal noise is high (resulting in large reconstruction errors), \(\alpha\) approaches zero, causing the model to prioritize BiGRU temporal features. Conversely, when signals are stable (with small reconstruction errors), \(\alpha\) approaches 1, emphasizing the AE’s dimensionality reduction capabilities. The expression for the fused feature F is detailed in Eq. (6).

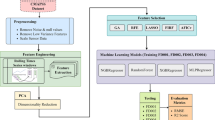

In Eq. (6), \({F_{AE}}\) represents the AE dimensionality reduction feature, and \({F_{BiGRU}}\) represents the BiGRU time series feature. An AE-BiGRU-based signal feature extraction model for aircraft engine CM is obtained. The model structure is shown in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2, after AE extracts key features from audio data, the model inputs them into BiGRU for temporal feature learning, integrating the advantages of both and improving the feature extraction capability of AE-CMSs. Compared with traditional feature extraction algorithms such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and WT, the AE-BiGRU algorithm offers significant advantages. PCA is a linear dimensionality reduction method that projects raw data into a lower-dimensional space through orthogonal transformations, retaining key information. However, PCA is limited to handling linear relationships and can effectively extract temporal features and deeper information from complex nonlinear data, such as CM signals of aircraft engines. While WT can handle nonlinear signals, it primarily focuses on time-frequency analysis and has limited capability in capturing long-term dependencies within the signal. The AE-BiGRU algorithm combines the dimensionality reduction capabilities of AE with the temporal feature extraction capabilities of BiGRU. AE can map high-dimensional CM signal data to a lower-dimensional hidden layer, achieving lossy compression while retaining key features. BiGRU can consider both past and future information, better capturing the temporal dependencies within the signal.

Optimization design of SMA algorithm considering Lévy distribution

After completing the feature extraction of AE-CMS, this study combines ISMA and SVM as classifiers to propose an AEF diagnosis model based on ISMA-SVM. Firstly, the Lévy distribution is introduced to improve the SMA. The heavy-tailed nature of the Lévy distribution enables long-distance jumps, which helps the algorithm avoid getting stuck in local optima. In the SMA, incorporating the Lévy flight model allows slime molds to more frequently escape from local optima and explore other potential optimal regions. The Lévy flight model, as a special form of random walk, has a power-law distribution of step size and infinite variance. Compared with traditional Brownian motion, it has stronger exploration ability, allowing slime molds to adopt more effective random walk strategies. The Lévy flight model increases the information entropy during the search process, allowing the algorithm to collect more information and improve search efficiency. Lastly, from a convergence theory standpoint, the Lévy flight model helps improve the convergence speed and accuracy of the SMA. The above theoretical analysis indicates that the Lévy flight model can effectively enhance the performance of the SMA, making it more suitable for use in the fault diagnosis of aircraft engines. The traditional SMA is an optimization algorithm that imitates the exploration and path-finding behavior of Slime Molds (SMs) in the process of searching for nutrients and food25,26. The process of the traditional SMA is displayed in Fig. 3.

In Fig. 3, SMA achieves optimization by simulating the propagation of waves in a biological oscillator to obtain feedback mechanisms. Its oscillation mode exhibits better search capability in the engineering field, but there is a risk of local optima. To improve this deficiency, the optimization algorithm introduces a random walk model based on the Lévy stable distribution. This enhances the global search ability through the long tail jump characteristic, effectively improves the convergence efficiency, and reduces the possibility of dropping into a local extremum. The distribution of this model follows a power-law formula, as shown in Eq. (7).

In Eq. (7), \(f(x)\) is a Lévy stable distribution. \(\alpha\) is a random number with a value range of (0,2]. The calculation process of a random number is shown in Eq. (8).

In Eq. (8), u and v are parameters that follow a standard normal distribution. \(\phi\) is obtained based on \(\alpha\) and the standard gamma function. Assuming the standard gamma function is G, the calculation process is shown in Eq. (9).

Figure 4 shows the iteration trajectory of the Lévy flight model, demonstrating the motion of the model in one iteration out of 250 iterations. The trajectory of each run shows significant differences. Based on this feature, the Lévy flight model theoretically can help swarm intelligence optimization algorithms further avoid the problem of local optima.

In Fig. 4, the trajectories in different colors represent the movement paths of individual entities (or cycles) within 250 iterations of the Lévy flight model. The heavy-tailed characteristic of Lévy flight enables trajectories to exhibit long-distance jumps (such as significant leapfrogging regions), enhancing the algorithm’s global search capability. Compared with traditional random walks, this approach more effectively explores potential optimal solution areas, thereby facilitating efficient optimization of SVM parameters in aircraft engine fault diagnosis. During the process of finding the optimal path, the SMA first needs to use a contraction formula to simulate the scenario where the SM colony approaches food. Assuming \(\vec {x}(t+1)\) is the location of the SM community in the \((t+1)\) generation. \({\vec {x}_b}\) is the single point location with the highest current odor concentration. \({\vec {x}_A}\) and \({\vec {x}_B}\) are casually selected positions of SMs. \(\vec {W}\) denotes the weight of SM. The contraction process is shown in Eq. (10).

In Eq. (10), both \(\vec {v}b\) and \(\vec {v}c\) are parameters, where the value range of \(\vec {v}b\) is linearly reduced from 1 to 0 for \(\vec {v}c\). r is the judgment condition. p is a classification criterion, calculated as shown in Eq. (11).

In Eq. (11), \(S(i)\) is the fitness of the SM at the current location. \(DF\) denotes the optimal fitness given by the maximum Number of Iterations (NoI). The value of \(\vec {v}b\) is shown in Eq. (12).

In Eq. (12), a is a number obtained based on the maximum NoI set by the SMA, as shown in Eq. (13).

In Eq. (13), \(t\hbox{max}\) is the maximum NoI, while t is the current NoI. Additionally, it is needed to define the weight of the SM in the shrinkage formula, as shown in Eq. (14).

In Eq. (14), \(BF\) is the best fitness obtained through iteration up to the current point, while \(wF\) is the worst fitness gained at this point. \(specific\,condition\) is a condition of the formula, representing the population of SMs with fitness in the top half of the current position. \(other\,condition\) is a population whose fitness is not in the top half. After detecting food, SM will try to go to places with higher food concentration, that is, place with higher weight27,28. According to this feature, the update of SM position is shown in Eq. (15).

After constructing the contraction mode of the SMA, the Lévy flight model can be applied to the SMA to improve its convergence performance. During the search process, Lévy flight can maximize the efficiency of resource search, thereby increasing algorithm efficiency. The Lévy flight model is used to replace the traditional uniform distribution, so the position update rule of the SMA is changed, as shown in Eq. (16).

In Eq. (16), \(\varepsilon\) is a parameter with a fixed value of 0.01. \(\otimes\) is Hadamard accumulation. In the optimized position update formula, Lévy flight determines its random compensation. Under the new location update rule, the new location update formula is shown in Eq. (17).

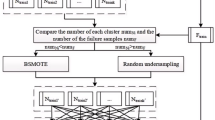

In Eq. (17), f represents the current fitness, \({f_{b{\text{est}}}}\) represents the optimal fitness, and \({f_{w{\text{orst}}}}\) represents the worst fitness. After the above optimization design, the ISMA is obtained, and its process is shown in Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5, the population size, initial position, and maximum iteration value of the SM are initialized first. Each individual parameter, fitness, and algorithm weight is calculated and iterated. In the algorithm running process, two random SM positions are first generated, and then iterative actions are completed by continuously calculating fitness values and arranging them according to size. Finally, the algorithm updates the optimal position and fitness through weights, and determines whether the algorithm has iterated to the optimal result based on factors such as size, dimension, and NoI. When the iteration result meets the conditions, the algorithm outputs the final result. The input data for weight calculation include various parameters and fitness values. These data are input into the “Weight Calculation” module, as indicated by the arrows added in Fig. 5.

In the ISMA, the parameter ε is set to 0.01 to maintain appropriate randomness during the search process and prevent premature convergence to local optima. The parameter α (Lévy index) in the Lévy flight model is set to 1.5 based on the characteristics of the Lévy distribution, which enables long-tail jumps during the search process and enhances the algorithm’s global search capability. These parameters are determined through extensive experimentation and comparative analysis, aiming to balance the algorithm’s convergence speed and global search capability.

Design of AE-CMS fault diagnosis model based on ISMA-SVM

In the AEF model, the classifier used is a supervised learning model built on SVM, which is used for classification and regression analysis. It achieves data classification by searching for an optimal hyperplane in high-dimensional space, maximizing the distance between two types of sample points from that plane. When choosing fault diagnosis classification algorithms, although newer methods such as XGBoost and LightGBM, as well as more complex DL models, can be used, the selection of SVM as the classifier in this study is based on multiple rational considerations. Although integrated learning algorithms like XGBoost and LightGBM can enhance performance through decision tree aggregation, they exhibit limitations in aircraft engine fault diagnosis. These algorithms tend to overfit when handling scarce fault data and demonstrate poor generalization capabilities. When processing time-series fault signals, their performance falls short compared to models specifically designed for time-series data or those effectively utilizing kernel functions29. Although DL models excel at handling large-scale datasets and complex features, they require a significant amount of computing resources and time, have slow inference speeds, cannot meet real-time requirements, and lack interpretability, making them unsuitable for high security scenarios30,31. In contrast, SVM performs well in small sample scenarios because it avoids overfitting, uses kernel functions to handle nonlinear relationships to reveal complex fault features, and provides simplicity and strong interpretability. All these qualities make it particularly suitable for aircraft engine fault diagnosis. Therefore, after comprehensive evaluation of these factors, this study selects SVM as the classifier and optimizes its parameters through the ISMA to further enhance classification performance. The loss function diagram of SVM algorithm is shown in Fig. 6.

The SVM algorithm in Fig. 6 is different from traditional regression methods. The goal is to find a hyperplane that places most of the data points within an “ε-band” centered on the hyperplane, while minimizing prediction error. SVM processes nonlinear data by introducing kernel functions, mapping nonlinear problems in a low-dimensional space to a high-dimensional space, making them linearly separable in the high-dimensional space. Among numerous kernel functions, Radial Basis Function (RBF) has good performance and a low error rate. Therefore, this study chooses RBF as the kernel function of SVM, as shown in Eq. (18).

In Eq. (18), g is the kernel parameter and x is the support vector. In fault diagnosis, how to select the RBF parameters and penalty parameters of SVM to achieve better results still needs to be solved. When SVM does not effectively select parameters, the accuracy of fault diagnosis will be greatly affected, thereby affecting the detection results and providing incorrect information. In response to this issue, this study takes the penalty parameters and RBF parameters of SVM as individuals of SMs, and obtains the optimal SVM parameters through mutual cooperation among SMs. This study uses the proposed ISMA to optimize these two parameters and constructs an ISMA-SVM fault diagnosis model. Figure 7 shows the specific process.

In Fig. 7, this study utilizes ISMA to optimize SVM parameters for AEF diagnosis. Firstly, a systematic preprocessing is carried out on the collected AEF data. This includes data normalization, labeling, and reasonable partitioning of the dataset. Subsequently, various parameters of the ISMA are set to ensure its effective operation. Next, the fitness of the initial population is calculated, which is achieved by comparing the classification accuracy to preliminarily determine the optimal solution in the population. On this basis, this study continuously updates the position of the SM based on changes in the NoI and calculates the fitness of the reverse solution. By comparison, the solution with better fitness can be selected to update the global optima. When the NoI reaches the preset requirement or the fitness of the optima meets the conditions, the algorithm iteration terminates and outputs the global optima. This optimal solution will be used as the optimal parameter for SVM to test the effectiveness on the test samples. In the aviation engine fault diagnosis model, the ISMA-SVM approach offers several innovations over other hybrid methods, such as WOA-SVM and PSO-SVM. The ISMA enhances its global search capability by incorporating the Lévy flight model, which significantly improves the algorithm’s convergence efficiency and reduces the likelihood of getting stuck in local optima. Additionally, the ISMA can more effectively identify the global optimal solution when optimizing the SVM parameters, thereby improving the accuracy of fault diagnosis. The code of ISMA-SVM model construction and diagnosis process is shown in Table 1.

Compared to traditional optimization algorithms such as Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Simulated Annealing (SA), the ISMA demonstrates superior global search capabilities and faster convergence rates. GA, an optimization algorithm based on evolutionary theory, employs operations like selection, crossover, and mutation to find the optimal solution. However, GA is prone to getting stuck at local optima when tackling complex problems and has a relatively slow convergence rate. In contrast, the SA algorithm simulates the annealing process of metals to find the optimal solution, offering some global search capabilities. However, it requires continuous temperature parameter adjustments during the search process, which increases computational complexity.

The time complexity of the ISMA-SVM method is analyzed in two stages. In the AE-BiGRU feature extraction stage, the training time complexity of the AE primarily depends on its network structure and data volume. Assuming the number of neurons in the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer of the AE is \({n_1}\), \({n_2}\) and \({n_3}\), with N samples and \({T_1}\) iterations, the time complexity is approximately \(O\left( {{T_1} \times N \times \left( {{n_1} \times {n_2}+{n_2} \times {n_3}} \right)} \right)\). The time complexity of the BiGRU is influenced by the sequence length L and the hidden layer dimension d. If the NoI is \({T_2}\), the time complexity is approximately \(O\left( {{T_2} \times N \times L \times {d^2}} \right)\). Therefore, the total time complexity of the AE-BiGRU feature extraction stage is \(O\left( {{T_1} \times N \times \left( {{n_1} \times {n_2}+{n_2} \times {n_3}} \right)+{T_2} \times N \times L \times {d^2}} \right)\).

During the ISMA optimization of SVM parameters, the time complexity of the ISMA primarily depends on the population size M, the maximum NoI \({T_3}\), and the problem dimension D. In each iteration, the fitness value of each individual must be calculated. Assuming the time complexity for calculating fitness is \(O\left( f \right)\), the time complexity of the ISMA is approximately \(O\left( {{T_3} \times M \times f} \right)\). The time complexity of SVM training is related to the number of samples N and the feature dimension d, which is approximately \(O\left( {{N^2} \times d} \right)\) (for quadratic programming problems). Therefore, the total time complexity of the ISMA optimization of SVM parameters is \(O\left( {{T_3} \times M \times f+{N^2} \times d} \right)\).

Results

Dataset construction and algorithm performance analysis

AEF diagnosis, two datasets are selected for experimental analysis. One is the publicly available dataset C-MAPSS. This dataset contains simulation data of multiple aircraft engines running until failure, covering different operating conditions and failure modes. It occupies a vital position in the research of AEF diagnosis and is an essential resource in aircraft engine health management. The study utilizes the C-MAPSS dataset (comprising 4 fault modes, 6 operating conditions, and full lifecycle temporal data of engines). Through stratified sampling based on fault types (4 categories), operating conditions (6 types), and temporal integrity (≥ 50 time steps), 1,200 representative samples are selected (including 400 normal operation samples and 800 fault condition samples covering all engine IDs). After labeling and normalization, the data are divided into training set (720 samples) and test set (480 samples) in a 3:2 ratio. The second is to use GasTurb engine modeling software to obtain a dataset of turbofan engine faults. Specifically, the dual-axle turbofan engine model is chosen to simulate the engine’s operation under various conditions. The engine’s air path performance is characterized by eight health indicators, including efficiency and flow indices. Degradation in turbofan engine performance can lead to changes in measurement parameters, and sensor parameters also reflect these performance changes. When simulating faults, for compressor failures, the efficiency index is set to vary between 0.85 and 0.95 (the normal efficiency index is assumed to be 1, and this range indicates a decrease in efficiency), with the flow index varying between 0.9 and 1.0 (the flow index also fluctuates due to the fault). For fan failures, the efficiency index is set to vary between 0.8 and 0.9, and the flow index is set to vary between 0.85 and 0.95. For turbine failures, the efficiency index is set to vary between 0.75 and 0.85, and the flow index is set to vary between 0.8 and 0.9. By adjusting these indices, fault data samples are generated, each containing 34 feature parameters (the number of features is determined by considering multiple factors such as engine operating parameters and performance indicators). These samples are then labeled and divided into training and test sets, with a ratio of 3:2.

The self-built simulation dataset can simulate the fault situation of aircraft engines to a certain extent, but it cannot completely replace the real experimental dataset. Real experimental datasets include various complex factors in actual operations, such as environmental noise and sensor errors, which are difficult to replicate in simulation datasets. However, in the research of aircraft engine fault diagnosis, it is often difficult to obtain real experimental data, and the amount of data is limited. In such cases, self-built simulation datasets can serve as a supplement for preliminary algorithm validation and parameter tuning. O. Nave used real aviation engine fault datasets for fault diagnosis research, and the results showed that training and testing based on real datasets can more accurately reflect the performance of algorithms in practical applications. Table 2 shows the parameters of the experimental setup.

The codebase for this research project is developed in Python, utilizing industry-standard machine learning and deep learning frameworks such as scikit-learn and TensorFlow. The architecture features a well-structured workflow encompassing data preprocessing, model construction, training, and evaluation. Upon request, the codebase can be made available to facilitate replication of experimental results and support further research endeavors. The sensitivity analysis of key hyperparameters was carried out, and the results are shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, the AE iteration count and BiGRU hidden layer dimensions were determined through systematic grid search with step sizes of 200 and 16 respectively, with optimal values corresponding to the smallest accuracy fluctuations (± 1.2% and ± 2.3%). The ISMA population size was determined through five empirical control experiments, with 30 iterations showing the highest and most stable accuracy. The SVM parameter C was automatically optimized by ISMA, achieving an accuracy fluctuation of only ± 0.9%. All parameter adjustments are documented in the parameter configuration files provided in the supplementary materials, ensuring strong reproducibility. For engine vibration signals, using 44.1 kHz a higher sampling rate than commonly used 22.05 kHz in aviation can prevent high-frequency fault pulse distortion. The 1-second window is used to divide continuous time signals into independent samples, covering the single pulse cycle of typical engine faults.

In the research of aircraft engine fault diagnosis, to ensure the generalization ability of the model and the reliability of the evaluation results, while avoiding overfitting, hierarchical 10-fold cross-validation is adopted. The dataset is stratified according to fault type proportions and randomly divided into 10 folds. Each fold serves as a training set with 9 folds as validation sets, with this process repeated three times and the averages calculated. The cross-validation results are presented in Table 4.

As shown in Table 4, the performance of each model on the C-MAPSS dataset and the self-built simulation dataset is consistent with previous results. Through the independent sample t-test, the significance of inter-group differences was verified: in the comparison between ISMA-SVM and SVM, WOA-SVM and SMA-SVM, the p value was all < 0.05 (the lowest was 0.0005), indicating that the performance improvement was statistically significant and random error interference was excluded. The ISMA-SVM model outperforms other models in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score across both datasets. For instance, on the C-MAPSS dataset, the ISMA-SVM model achieves an accuracy of 97.24%, which is about 13% higher than the SVM model, indicating that the ISMA-SVM model avoids overfitting and demonstrates superior generalization and fault diagnosis capabilities. On the self-built simulation dataset, the ISMA-SVM model also performs exceptionally well, leading in all metrics, further confirming its effectiveness. Furthermore, the 10-fold F1 score of ISMA-SVM averages 0.96 with a standard deviation ± 0.01, demonstrating stable generalization capability. The SVM model mitigates overfitting by restricting the penalty parameter C within [0.1, 100], while the AE-BiGRU training employs an early stopping mechanism (termination when validation loss stagnates for 10 consecutive rounds) to further reduce overfitting risks.

Traditional SMA, Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), and PSO are selected for comparison in ISMA performance testing. Mean and standard deviation are selected as evaluation indicators. The unimodal functions f1 and f2, as well as the multimodal functions mf1 and mf2, are used as benchmark test functions. Under the unimodal function, the test results of each algorithm run independently 30 times are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 (a) and (b) show the test results under unimodal functions f1 and f2. Here, the average fitness of the algorithm, i.e., the speed at which the standard deviation converges, is utilized to evaluate the performance under different functions. For objective evaluation, in addition to studying algorithms, SMA, PSO, and WOA are also used as comparisons in testing under unimodal functions. From the image, the standard deviation convergence of the research algorithm is the fastest under different functions, and there is a significant gap compared to other algorithms, p<0.05. Under unimodal functions, the standard deviation of WOA and PSO decreases very slowly, and the converged variance is also much higher than that of SMA, p<0.05. Under function f1, the standard deviation of both the research algorithm and SMA is lower than 10–300, but ISMA has already reached this standard at the 400th iteration, while SMA is later than 400 iterations. Under function f2, the standard deviation of ISMA decreases more slowly. When iterating to 500, the standard deviation of ISMA is lower than that of other algorithms, p<0.05. The testing of each algorithm under multimodal functions is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9 (a) and (b) show the performance of each algorithm under multimodal functions mf1 and mf2. Under multimodal functions, the standard deviation reduction ability of all functions is stronger than that under unimodal functions. The descent speed and amplitude of SMA and ISMAs are much higher than those of other two algorithms, p<0.05. In addition, the performance of SMA and research algorithms under multimodal functions is closer to that under unimodal functions. This is because SMA is easier to handle multimodal functions, resulting in a faster speed and higher optimization difficulty in obtaining the optimal solution, whileLévy flight may be difficult to further optimize for this situation.

In the performance testing of the ISMA-SVM model, this study selects the typical dataset, Ionosphere from the UCI database, for experimentation. The ionosphere is a publicly available dataset commonly used in machine learning, particularly in classification problems. The ionosphere contains 351 samples, each with 34 continuous features. This study divides the training and testing sets in a 3:2 ratio. The confusion matrix results of PSO-SVM, WOA-SVM, SMA-SVM, and ISMA-SVM models are listed in Table 5.

In Table 5, the PSO-SVM model has high False Positives (FP) and False Negatives (FN) in the CM signal fault diagnosis task. The performance of WOA-SVM is limited, with high FP and FN. SMA-SVM performs well with low FP and FN. The research model performs the best, with the lowest FP and FN, an ACC of 0.90, a recall of 0.95, and an F1 score of 0.92, indicating the best overall performance.

To more intuitively compare the calculation efficiency of different methods, experimental tests are carried out. The experimental dataset C-MAPSS is used to record the running time of different methods, and the results are shown in Table 6.

As shown in Table 6, the running time of all three methods increases with the increase in data volume. However, at the same data scale, the ISMA-SVM method has a relatively shorter running time and a smaller standard deviation, indicating its advantages in computational efficiency and stability. This is mainly due to the fast convergence of ISMA, which allows it to find the optimal SVM parameters with fewer iterations, thereby reducing the overall computation time. On the C-MAPSS dataset, the ISMA-SVM was compared with a deep learning end-to-end model (CNN-LSTM hybrid model) to highlight the trade-off between accuracy and interpretability. The comparison results are shown in Table 7.

As shown in Table 7, CNN-LSTM outperforms ISMA-SVM by only 0.88% and 0.81% in accuracy and recall rates respectively, but scores 5.3 points lower in interpretability metrics, making it difficult to trace fault characteristics clearly. Notably, CNN-LSTM requires 2,000 training datasets to achieve stable performance – 2.78 times more than ISMA-SVM. In small-sample scenarios (fewer than 500 training datasets), ISMA-SVM demonstrates an 8.3% higher accuracy rate than CNN-LSTM, proving its greater practical value in balancing accuracy and interpretability.

Finally, the computational cost and scalability of the ISMA-SVM model were tested on a large real-world engine dataset. This dataset is sourced from a Chinese enterprise specializing in civil aviation transportation (the specific name is temporarily not disclosed due to confidentiality agreements). This dataset is based on the engine health management system of 50 narrow body aircraft of the same model under the company, with a time span from January 2024 to June 2025. It stores a total of 5000–20,000 valid samples (each sample contains 10 min of continuous operation of multi-sensor time-series data), and has undergone data anonymization to remove sensitive information such as flight numbers and takeoff and landing airports, retaining only technical parameters related to engine status. The test results are shown in Table 8.

As shown in Table 8, the ISMA-SVM maintains a sTable 106.9%−111.6% increase in single-diagnosis time with growing data volume, significantly lower than PSO-SVM’s 126.0%−134.7%. Its memory usage consistently stays 8.1%−16.8% lower than PSO-SVM’s. Remarkably, even when processing 20,000 data sets, ISMA-SVM can still complete diagnoses 185.2s in-memory, demonstrating robust scalability across large-scale real-world datasets.

Simulation analysis of AEF diagnosis model

To validate the effectiveness of the ISMA-SVM, the publicly available dataset C-MAPSS for aircraft engines is validated. The maximum NoI for all algorithms is 50, and the population size is 30. The prediction results of SVM optimized by each algorithm are shown in Fig. 10.

In Fig. 10 (a), SVM has 7 samples with classification errors and mistakenly classifies them as Class 1 faulty components. In Fig. 10 (b), WOA-SVM has three samples with classification errors, all of which are mistakenly classified as Class 1 faulty components. In Fig. 10 (c), SMA-SVM has two samples with classification errors, one of which is mistakenly classified as a fault component in category 1 and the other as a fault component in category 2. In Fig. 10 (d), one sample of ISMA-SVM has a classification error and is mistakenly classified into two types of faulty components. This indicates that ISMA-SVM achieves the best fault classification results compared to other models. Subsequently, a self-built simulation dataset is used for validation, as shown in Fig. 11.

Figures 11 (a) to (d) show the fault classification results of the SVM, WOA-SVM, SMA-SVM, and ISMA-SVM models. On the simulation dataset, the basic SVM without parameter optimization performs the worst in classification tasks, and the classification performance is not satisfactory. After algorithm optimization, the classification performance of SVM has significantly improved compared to the basic SVM. Among them, ISMA-SVM performs particularly well in classification tasks, with extremely high classification ACC and only 6 misclassifications, fully demonstrating the superiority and ACC in classification performance. The paper compares the fault diagnosis results of ISMA-SVM with those of other commonly used models on C-MAPSS and self-built simulation datasets. The ACC, recall, and F1 score test results of various models are listed in Table 9.

In Table 9, in terms of the selection of the improved SVM algorithm in C-MAPSS, ISMA is significantly better than other swarm intelligence algorithms in optimizing SVM performance. In addition, by comparing the predicted results with other common models, it can be found that ISMA-SVM performs the best in all three evaluation indicators, with an ACC rate of 97.24%, a recall rate of 96.55%, and an F1 score of 96.50%. In the self-built simulation dataset, ISMA-SVM performs the best, with an ACC rate of 96.79%, a recall rate of 96.47%, and an F1 score of 96.44%. This indicates that the ISMA-SVM AEF diagnosis model has superior performance. The depth comparison results of ISMA-SVM model with literature32 and literature33 are shown in Table 10.

As shown in Table 10, compared to literature33, ISMA-SVM demonstrates 3.14% higher accuracy and 26.2% lower computational cost, while supporting near real-time diagnostics. Compared with literature32, it achieves 1.44% higher accuracy and reduces diagnostic time by 27.8% under large-scale data (20,000 samples). Regarding scalability, when the dataset size doubles, the original method’s accuracy decreases by 5.2%−7.8%, whereas ISMA-SVM maintains 1.3% accuracy improvement, proving its superior performance in balancing computational efficiency, scalability, and real-time capabilities.

Example application analysis

To validate the practicality of the proposed method, the fault diagnosis model is integrated into the fault diagnosis system of a certain group’s aviation engine, and the fault of a certain civil aviation engine system in the group is diagnosed. This case focuses on the analysis of fault vibration data collected from a civil aviation engine of a certain group. During the test, the outer rings of the supporting bearings for the L1 and L5 axes suffer minor scratches with a width of 1 mm and a depth of 0.3 mm, as well as larger-scale but only 0.1 mm deep peeling damage, while the other components remain in normal condition. The experiment uses the “ACC2” sensor and records a vibration signal with a sampling frequency of 44.1 kHz for a duration of 204s. Specifically, the signal consists of two stages of uniform rotation (0–47 s and 164–204 s) and one stage of variable speed operation from 47 to 164s. This study selects K-Singular Value Decomposition (K-SVD) and research methods for comparative analysis, and the obtained signal analysis comparison is shown in Fig. 12.

Figures 12 (a)/(b) and (c)/(d) show the signal time-domain waveform and signal squared envelope spectrum under the research method and K-SVD. In Figs. 12 (a) and (b), some transient components can be clearly observed in the time-domain signals extracted by the research method. Through square envelope spectrum analysis of these transient components, it is found that the fault characteristic frequencies of orders 1 to 5 are accurately identified. It is particularly important that the interference frequencies around high-order frequencies are effectively removed, which further confirms that the outer ring of the bearing on shaft L5 has indeed malfunctioned. This validates the effectiveness of the ISMA-SVM in diagnosing faults in aircraft engine transmission systems. In Figs. 12 (c) and (d), the time-domain vibration signals obtained by processing using the K-SVD method maintain high similarity in waveform with the original signal. Further investigation reveals that the interference frequency around the 4th-order Ball Pass Frequency Outer Race (BPFO) is effectively reduced, while the intensity of the 5th-order BPFO also becomes weaker accordingly. The recognition problem of 2nd-order BPFO still exists, and its signal features cannot be effectively identified and analyzed. Compared with the K-SVD method, the research method has significant advantages in extracting weak fault pulse signals and identifying fault characteristic frequencies.

To further validate the proposed fault diagnosis method, the study selects an engine from a certain airline for further verification. This airline operates multiple aircraft equipped with specific engine models. During routine maintenance, it is observed that some engines exhibit performance degradation and abnormal vibrations, but traditional diagnostic methods struggle to accurately identify the type and location of the faults. To improve maintenance efficiency and achieve more precise fault diagnosis, the company adopts the proposed fault diagnosis method to classify the faults. The test results are presented in Table 11.

As shown in Table 11, the p-values for the diagnostic results of all fault types are all below 0.05, indicating that the diagnostic results are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. This result suggests that the effectiveness of the fault diagnosis method is not accidental. For the normal state, the 95% confidence interval is [93.97%, 99.81%], with a diagnostic accuracy of 98% within this range, indicating high reliability in identifying the normal state. The 95% confidence interval for blade damage fault diagnosis is [88.34%, 98.72%], with an accuracy of 95% within this range and a p < 0.05, indicating significant diagnostic effectiveness. The 95% confidence interval for bearing fault diagnosis is relatively wide, but the accuracy of 96.4% is still within this range, with a p < 0.01, indicating strong and stable diagnostic capability for bearing faults. The 95% confidence interval for seal failure diagnosis is [84.36%, 98.47%], with an accuracy of 93.3% within this range and a p < 0.05, indicating that this method also has some diagnostic effect on seal failures. Overall, the fault diagnosis method proposed in this study demonstrates reliability and effectiveness in the fault diagnosis of aviation engines. The research builds a real-time scene based on the actual operation logic of the civil aviation engine, and the hardware adopts the architecture consistent with the enterprise EHM system: eight high-precision sensors (four acceleration, two temperature, two pressure) are deployed in key parts, 44.1 kHz sampling rate is used to collect data, and the data is uploaded to the edge computing gateway (Intel Core i7-12700 H, 16GB memory) via industrial Ethernet, and the model is deployed locally to control the delay. The software adopts a 1-second sliding window (0.5s update) + VMD real-time denoising (mode number 5), a dual mechanism of “threshold triggering (vibration > 2.0 g) + timed triggering (1s/time)” to start diagnosis, and the results are pushed to the terminal in real time, with a total delay threshold of ≤ 80ms. The test scenarios correspond to actual working conditions: constant speed operation (cruise, speed 90% −95%), variable speed operation (climb/descent, speed 40% −90%), and start-up phase (ground start to takeoff, speed 0–90%), covering core scenarios with data fluctuations from low to high. The test results are shown in Table 12.

As shown in Table 12, the ISMA-SVM system demonstrated total diagnostic latency of 43.8ms, 54.3ms under constant-speed and variable-speed operation scenarios, both significantly below the threshold. During startup phases with high data fluctuations, the total latency 64.8ms with a 98.5% compliance rate. Compared to traditional offline diagnosis methods, real-time scenario model inference time increased by only 12.3%−48.6%, with no diagnostic interruptions occurring, fully meeting near-real-time diagnostic requirements.

Discussion

The study proposes an AEF diagnosis method based on ISMA to optimize SVM parameters, which demonstrates advantages in multiple aspects. The experimental results show that the ISMA-SVM model has higher accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score compared to other models such as PSO-SVM, WOA-SVM, SMA-SVM, and base SVM on the public dataset C-MAPSS and self-built simulation dataset. In the fault diagnosis task, the accuracy, recall, and F1 score of ISMA-SVM all reach 0.9 or above. In the C-MAPSS dataset prediction, the accuracy, recall, and F1 score of the ISMA-SVM model reach 97.24%, 96.55%, and 96.44%, respectively. This indicates that the ISMA has significant effects in optimizing SVM parameters and can improve the classification performance of the model.

Compared with the intelligent multi-fault diagnosis method proposed in reference34, the research method has improved the accuracy and comprehensiveness of fault diagnosis. Reference35 mainly focuses on simplifying the multi-fault diagnosis of aircraft fuel systems, while the research method focuses on AEF diagnosis. By introducing the ISMA to optimize SVM parameters, it better adapts to the complex working environment and fault characteristics of aircraft engines. The research method has stronger pertinence and adaptability in dealing with AEF diagnosis problems. The ISMA-SVM model can more effectively extract fault features of aircraft engines and improve the accuracy of fault diagnosis. Compared to this study, the reference method36 has achieved unsatisfactory application results. The ISMA-SVM model has demonstrated excellent performance in AEF diagnosis, providing an effective fault diagnosis method for this field. Furthermore, high accuracy is critical in aircraft engine fault diagnosis and classification. Due to the fact that engines are the core components of aircraft, even minor malfunctions can lead to serious accidents, and aviation standards require an accuracy rate of at least 95%. In this study, the ISMA-SVM model achieves an accuracy rate of 97.24% on the C-MAPSS dataset and 96.79% on a self-built simulation dataset, both exceeding the threshold. This demonstrates the model’s capability to accurately identify fault types, providing reliable decision-making support for maintenance operations while reducing safety risks and economic losses. Additionally, its strong generalization ability allows adaptation to various operating conditions, thereby enhancing overall engine health management.

Overall, the proposed AEF diagnosis method based on ISMA-optimized SVM parameters has reliability and effectiveness, providing a new approach and method for AEF diagnosis.

Conclusion

With the continuous intelligence and systematization of aviation engines, the CM data of aviation engines are growing exponentially, and traditional methods for diagnosing CM signal faults in aviation engines can no longer meet practical needs. In response to the current problems of low ACC and poor real-time performance in the diagnosis of CM signal faults in aircraft engines, this study developed a feature extraction model for AEF signals built on AE-BiGRU. Then, this study combined ISMA and used SVM to propose a fault diagnosis method for AE-CMSs grounded on ISMA-SVM. In function optimization tasks, SMA and its improved versions exhibited stronger variance reduction ability in both unimodal and multimodal functions compared to WOA and PSO, especially in multimodal functions where the advantage was more pronounced. In fault diagnosis tasks, PSO-SVM and WOA-SVM had higher FP and FN, while SMA-SVM performed better. ISMA-SVM performed the best, FP and FN were the lowest, with an ACC of 0.90, a recall of 0.95, and an F1 score of 0.92. In the prediction of C-MAPSS, the ISMA-optimized SVM performed significantly better than other algorithms. ISMA-SVM performed the best in ACC, recall, and F1 score, reaching 97.24%, 96.55%, and 96.44%. In practical applications, compared to other methods, ISMA-SVM had significant advantages in extracting weak fault pulse signals and identifying fault characteristic frequencies, indicating its superior performance in AEF diagnosis. However, the ISMA proposed this time has a strong dependence on data. Future research will focus on simplifying algorithms to improve real-time performance, enhance data robustness, and explore more intelligent algorithm fusion to further improve the efficiency of fault diagnosis.

Limitations and future work

This approach exhibits three critical limitations: First, the application of simulated datasets in aero-engine fault diagnosis research faces inherent limitations. While these datasets can simulate engine failures to some extent, they fail to fully capture the complex operational factors present in real-world scenarios. For instance, actual environments contain diverse noise sources such as mechanical vibrations and electromagnetic interference, which differ in characteristics from those in simulated datasets. Moreover, real engine fault data encompasses more unpredictable failure modes and complex operating conditions, whereas simulated datasets are typically generated based on predefined assumptions and simplified models, resulting in insufficient data diversity. These limitations may impair the generalization capability of models trained on simulated datasets when applied to actual engine fault diagnosis. Such models might misdiagnose certain failure patterns or complex operating conditions not fully represented in simulations, thereby reducing the reliability and accuracy of fault detection systems. Second, its capacity to handle complex operating conditions and fault types remains inadequate. For scenarios involving multi-mode composite faults, diagnostic accuracy and robustness need to be improved. Third, real-time performance faces challenges as increased data volume and heightened diagnostic requirements may lead to diagnostic delays through computational demands.

To address these limitations, four key improvements are proposed:

-

(1)

By using data augmentation techniques, the generation of training data has been enhanced, and combined with transfer learning, pre trained models from other fields have been utilized to overcome data scarcity.

-

(2)

The composite fault characteristics are analyzed in depth, and the physical model is combined with a data-driven model to improve the ability to handle complex situations.

-

(3)

Parallel computing technology is utilized to optimize algorithm architectures, explore effective optimization algorithms, and improve real-time response capabilities.

-

(4)

For multimodal composite faults, integrating multi-sensor data fusion technology can comprehensively utilize various types of data collected by different sensors to capture fault characteristics from multiple perspectives, thereby enhancing diagnostic capabilities. For instance, combining data from vibration sensors, temperature sensors, and pressure sensors enables a more comprehensive understanding of the engine’s operational status. When dealing with noisy or incomplete signals, advanced signal processing techniques such as deep learning-based noise reduction algorithms and signal completion methods can be employed. Deep learning models automatically learn noise patterns and missing data patterns in signals, effectively eliminating noise and completing signals to improve signal quality, thus providing more accurate information for fault diagnosis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(u\) :

-

Modal component

- \(\omega\)(rad/s):

-

Frequency center of each single-component

- \(k\) :

-

Number of modal components

- \(j\) :

-

Imaginary unit

- \(\delta (t)\) :

-

Diracδ-function

- \({\partial _t}\)(s-1):

-

Time derivative

- \(\psi (t)\) :

-

Wavelet basis function

- \(\tau\) :

-

Translation amount

- \(WT_{f} (a,\tau )\) :

-

Wavelet coefficient

- \(a\) :

-

Scaling factor

- \(f(t)\) :

-

Original signal

- \(x_{i}\) :

-

Compressed data by encoder

- \(L\) :

-

Reconstruction error function

- \(n\) :

-

Number of samples

- IMF:

-

Intrinsic Mode Function

- SVM:

-

Support Vector Machine

- ISMA:

-

Improved Slime Mould Algorithm

- AE:

-

Auto-Encoder

- BiGRU:

-

Bidirectional Gated Recurent Unit

- VMD:

-

Variational Mode Decomposition

- \(\vec{x}\) :

-

Position of slime mould

- \(\vec{x}_{B}\) :

-

Position of the highest-concentration food

- \(\vec{x}_{A}\) :

-

Randomly selected slime mould position

- \(r\) :

-

Classification standard

- \(p\) :

-

Calculation result of a formula

- \(S(i)\) :

-

Adaptability of the slime mould at the current position

- DF:

-

Optimal adaptability value given by the maximum number of iterations

- \(\vec{v}b\) :

-

Parameter vector

- \(t\) :

-

Current iteration number

- \(t\max\) :

-

Maximum number of iterations

References

Sahu, D., Dewangan, R. K. & Matharu, S. P. S. Hybrid CNN-LSTM model for fault diagnosis of rolling element bearings with operational defects. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 19 (8), 5737–5748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-024-02165-7 (2025).

Li, B. & Zhao, Y. P. Simultaneous fault diagnosis for aircraft engine using multi-label learning. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 236(7), 1355–1371. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544100211049935 (2022).

Sahu, D., Dewangan, R. K., Matharu, S. P. S. & Publishing, A. I. P. Rolling element bearing fault diagnosis using machine learning techniques: A review. Proc. Int. Conf. Appl. Mech., Mach. Learn. Adv. Comput. 2745, 030007. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0134211 (2023).

Sahu, D., Dewangan, R. K. & Matharu, S. P. S. Fault diagnosis of rolling element bearing with operationally developed defects using various convolutional neural networks. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 24 (3), 1021–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11668-024-01919-5 (2024).

Ren, C., Ma, L. & Wan, J. Research on civil aircraft fault diagnosis method based on selective integration. IOP Pub Ltd. 1 (4), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2764/1/012076 (2024).

Li, B. & Zhao, Y. P. Multi-label learning using label-specific features for simultaneous fault diagnosis of aircraft engine. J. Aerosp. Eng. Part. G. 236 (10), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544100211049935 (2022).

Mazakova, A., Jomartova, S. & Mazakov, T. The use of artificial intelligence to increase the functional stability of UAV systems. Int. Rev. Aerosp. Eng. 17 (3), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.15866/irease.v17i3.25067 (2024).

Li, J., King, S. & Jennions, I. Intelligent fault diagnosis of an aircraft fuel system using machine learning: A literature review. Mach 11(4), 749–766. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines11040481 (2023).

Miao, Y. et al. Bio-inspired fault diagnosis for aircraft fuel pumps using a cloud-edge system. Biomimetics 8(8), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8080601 (2023).

Feng, Y., Pan, W. & Cheng, L. U. Fault diagnosis and location of hydraulic system of domestic civil aircraft based on logic data. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 40 (4), 732–738. https://doi.org/10.1051/jnwpu/20224040732 (2022).

Fentaye, A. D., Zaccaria, V. & Kyprianidis, K. Aircraft engine performance monitoring and diagnostics based on deep convolutional neural networks. Mach. 9(12), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines9120337 (2021).

Wu, J., Kong, L. & Kang, S. Aircraft engine fault diagnosis model based on 1DCNN-BiLSTM with CBAM. Sens 24(3), 780–799. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24030780 (2024).

Pérez-Ruiz, J. L., Tang, Y. & Loboda, I. Aircraft engine gas-path monitoring and diagnostics framework based on a hybrid fault recognition approach. Aerosp 8(8), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8080232 (2021).

Arias Chao, M., Kulkarni, C. & Goebel, K. Aircraft engine run-to-failure dataset under real flight conditions for prognostics and diagnostics. Data 6(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/data6010005 (2021).

Lu, F., Li, Z. & Huang, J. Hybrid state Estimation for aircraft engine anomaly detection and fault accommodation. AIAA J. 58 (4), 1748–1762. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.J059044 (2020).

Mallikarjuna, P. B., Sreenatha, M. & Manjunath, S. Aircraft gearbox fault diagnosis system: an approach based on deep learning techniques. J. Intell. Syst. 30 (1), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1515/jisys-2019-0237 (2020).

Zhang, K., Lin, B. & Chen, J. Aero-engine surge fault diagnosis using deep neural network. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 42 (1), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.32604/csse.2022.021132 (2022).

Ullah, N., Umar, M. & Kim, J. Y. Enhanced fault diagnosis in milling machines using CWT image augmentation and ant colony optimized AlexNet. Sensors (Basel Switzerland) 24(23), 7466–7478. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24237466 (2024).

Siddique, M. F., Zaman, W. & Umar, M. A hybrid deep learning framework for fault diagnosis in milling machines. Sensors 25(18), 5866–5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25185866 (2025).

Siddique, M. F., Ullah, S. & Kim, J. M. A deep learning approach for fault diagnosis in centrifugal pumps through wavelet coherent analysis and S-Transform scalograms with CNN-KAN. Comput. Mater. Continua 84(2), 3577–3590. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065326 (2025).

Kabashkin, I. The iceberg model for integrated aircraft health monitoring based on AI, blockchain, and data analytics. Electron 13(19), 3822–3535. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13193822 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Wang, J. & Li, X. Extended least squares support vector machine with applications to fault diagnosis of aircraft engine. ISA Trans. 97 (2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2019.08.036 (2020).

Wang, X., Zhang, H. & Du, Z. Multiscale noise reduction attention network for aeroengine bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3268459 (2023).

Qin, Y., Yang, R. P. & Shi, H. Adaptive fast chirplet transform and its application into rolling bearing fault diagnosis under time-varying speed condition. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3282660 (2023).

Li, Z., Ma, J. & Fan, R. Aircraft sensor fault diagnosis based on graphsage and attention mechanism. Sens. 25(3), 1253–1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030809 (2025).

Wang, Z., Wang, Y. & Wang, X. A novel digital twin framework for aeroengine performance diagnosis. Aerospace 10(9), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace10090789 (2023).

Lv, D., Wang, H. & Che, C. Semisupervised fault diagnosis of aeroengine based on denoising autoencoder and deep belief network. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 94 (10), 1772–1779. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEAT-10-2020-0234 (2022).

He, Q. Z., Zhang, W. G., Liu, X. & Li, W. N. Aircraft inertial measurement unit fault diagnosis based on adaptive twostage UKF. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 38 (4), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1051/jnwpu/20203840806 (2020).

Xu, C., Gui, X. & Zhao, Y. Digital twin-assisted multiview reconstruction enhanced domain adaptation graph networks for aero-engine gas path fault diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 24 (13), 21694–21705. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3400249 (2024).

Liu, X., Yingjie, Y. C. & Xiong, L. Intelligent fault diagnosis methods toward gas turbine: A review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 37 (4), 93–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2023.09.024 (2024).

Zhang, B., Wang, W. & He, Y. A hybrid approach combining deep learning and signal processing for bearing fault diagnosis under imbalanced samples and multiple operating conditions. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 13606–13618. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24237466 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Feng, S., Yang, H., Hao, P. & Wang, B. Multi-failure mode reliability analysis method based on intelligent directional search with constraint feedback. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 426, 116995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2024.116995 (2024).

Nave, O. Singularly perturbed vector field method (SPVF) applied to combustion of monodisperse fuel spray. Equ Dyn. Syst. 27, 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12591-017-0373-7 (2019).

Li, J., King, S. & Jennions, I. Intelligent multi-fault diagnosis for a simplified aircraft fuel system. Algorithms 18(2), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18020073 (2025).

Berghout, T. & Benbouzid, M. Diagnosis and prognosis of faults in high-speed aeronautical bearings with a collaborative selection incremental deep transfer learning approach. Appl. Sci. -Basel. 13, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.3390/app131910916 (2023).

Luo, N., Yu, H. & You, Z. Fuzzy logic and neural network-based risk assessment model for import and export enterprises: A review. J. Data Sci. Intell. Syst. 1 (1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewJDSIS32021078 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China: Research on continuous safety analysis technology for civil aircraft (No. U2433213).

Funding

The research is supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China: Research on continuous safety analysis technology for civil aircraft (No. U2433213).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.X. processed the numerical attribute linear programming of communication big data, and the mutual information feature quantity of communication big data numerical attribute was extracted by the cloud extended distributed feature fitting method. X.P. and J.Y. Combined with fuzzy C-means clustering and linear regression analysis, the statistical analysis of big data numerical attribute feature information was carried out, and the associated attribute sample set of communication big data numerical attribute cloud grid distribution was constructed. P.X. and H.W.Z. did the experiments, recorded data, and created manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, P., Yu, J. & Zhang, H. Fault diagnosis using ISMA to optimize SVM parameters for aircraft engine damage repair. Sci Rep 15, 42152 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26237-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26237-0