Abstract

The gut–brain axis plays a critical role in maintaining neuronal integrity and influencing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here, we investigated how commonly consumed dietary fibers modulate gut microbiota, lipid metabolism, and AD pathology in 5xFAD mice. Male mice were fed either fiber-free (FF) or fiber-plus (FP; 1% cellulose, 2% pectin, 2% inulin) diets for five months, followed by integrated analyses of gut microbiota (16 S rRNA sequencing), fecal lipid metabolites (LC–MS/MS), and neuropathological and behavioral outcomes. FP diets markedly altered microbial composition, characterized by increases in Muribaculaceae, Ileibacterium, and Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group and reductions in Faecalibaculum and Coriobacteriaceae UCG-002. Fecal lipidomics revealed significant shifts in phospholipids and long-chain fatty acids, while short-chain fatty acid levels showed only modest, taxa-specific changes. Functionally, FP-fed AD mice exhibited reduced amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition, lower microglial activation, improved microglial morphology, and a decreased cortical and hippocampal Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. Moreover, FP diets enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis, preserved synaptic protein expression, and improved cognitive performance in object recognition and Y-maze tasks. FP supplementation also mitigated the increased intestinal permeability observed in AD mice. Together, these findings demonstrate that dietary fiber modulates the microbiome–lipid axis and attenuates AD-related pathology through mechanisms extending beyond SCFA production, supporting dietary interventions as a promising strategy for AD prevention and therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by clinically progressive cognitive decline, memory loss, and cerebral atrophy1. While its precise mechanisms remain elusive, the deposition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, tau neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation are hallmarks. Emerging evidence points to the involvement of systemic factors as well, including gut microbiota and lipid metabolism in AD pathogenesis2,3.

The gut microbiota, a diverse community of trillions of microorganisms, is engaged in metabolic regulation, immune function, and neurological health, among other functions4,5,6. Dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, is associated with obesity, diabetes, and other pathologies7,8. Gut dysbiosis exacerbates AD pathology through increased gut permeability, systemic inflammation, and the gut-brain axis9.

In parallel to other perturbations, dysregulation of lipid metabolism is linked to Aβ production, tau hyperphosphorylation, and neuroinflammation, contributing to AD progression10,11,12. Moreover, interest in the modulation of lipid metabolism by the gut microbiota has grown in recent years13,14. Changes in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), and sphingomyelin (SM) occur early in AD13,15,16,17.

Dietary fiber, known for its health benefits by modulating gut microbiota and reducing systemic inflammation, has a potential role in AD18,19. Soluble fibers promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria and lead to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which possess anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties20,21. In addition, in response to dietary fibers, gut microbiota influences lipid metabolism beyond SCFAs22 by regulating bile acid metabolism and phospholipid synthesis that, in turn, influence brain lipid homeostasis and neuroinflammation23,24.

Resistant starch and other specialized fibers enhance SCFA production and improve cognitive function in AD models25,26. However, these studies employed fibers that were not commonly consumed in daily diets and often at supra-physiological doses27,28, which may limit their translational relevance. Moreover, while SCFA production is well-studied, less is known about how dietary fiber at physiologically relevant levels regulates phospholipids, sphingolipids, and free fatty acids (FFAs), contributing to sustaining neuronal membrane integrity and synaptic plasticity29,30,31.

The present study was therefore designed to investigate whether supplementation with commonly consumed dietary fibers, provided at doses reflecting typical nutritional intake, could modulate AD pathology and cognitive outcomes in the 5xFAD transgenic mouse model. Specifically, we aimed to assess how fiber-driven alterations in gut microbiota composition influence lipid metabolism, including SCFAs and beyond, and whether these changes impact AD-related neuropathology and behavior. By focusing on fibers of dietary relevance and feasible intake levels, this work seeks to provide novel insights into the gut microbiome–lipid axis in AD and to highlight the translational potential of dietary fiber as an accessible intervention strategy.

Materials and methods

Animal models and experimental design

5xFAD male heterozygous transgenic mice (C57BL/6 background) and their wild-type (WT) littermates were used. Mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. After weaning at 1 month of age, both 5xFAD and WT littermate mice were switched to custom diets based on an established formulation32 used with either a diet rich in fiber (fiber plus diet, FP, TD.130715, Envigo) or a diet free of fiber (fiber free diet, FF, TD.00278, Envigo) (Supplementary Table 1). The FF diet was designed to reduce fecal output by using highly digestible ingredients and excluding significant fiber sources. The energy distribution of the diet was approximately 19.3% protein, 64.8% carbohydrates, and 5.1% fat. For the FP diet, modifications were made by adding 1% cellulose, 2% pectin, and 2% inulin, which were substituted for some of the dextrose content, while all other components remained the same. Mice were maintained on these diets until 6 months of age. A total of 64 mice were included in the study, with the following distribution among experimental groups: FFWT (n = 26), FPWT (n = 14), FFAD (n = 12), and FPAD (n = 12).

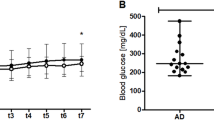

Fecal samples were collected at 4 and 6 months of age (after 3 and 5 months of dietary intervention, respectively) and were immediately frozen at -80 °C for microbiome (6-month age sample only) and lipidomic analysis (both 4- and 6-month age samples used). For baseline comparison, fecal samples from 1-month-old pups with standard chow diet right before entering formula diet feeding were also collected and later sent for lipidomics analysis. The experimental endpoint was at 6 months of age, at which time behavioral tests and biological sample collection were performed. Before sacrifice, mouse body weight was measured. Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of diet and no diet × genotype interaction, although genotype itself exerted a modest but significant effect, with AD mice displaying slightly lower body weights compared to WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 1). All procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations. Euthanasia was performed using carbon dioxide (CO₂) inhalation followed by decapitation using a guillotine to ensure rapid and humane termination. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans (IACUC Protocol #: 3762), and efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. This study follows the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) for reporting animal research.

Gut microbiota analysis

Fecal DNA was extracted using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). The 16 S rRNA gene V4 region was amplified and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 250 bp). Raw sequences were processed using the DADA2 pipeline in QIIME2, and taxonomic classification was performed against the SILVA v138 database. Alpha and beta diversity metrics were calculated in QIIME2. The sequencing and bioinformatics analyses were performed by the LSU Health Sciences Center Microbial Genomics Resource Group (http://metagenomics.lsuhsc.edu/), following established protocols33.

Behavioral testing

At 6 months of age, cognitive function and memory were assessed using the novel object recognition (NOR) test and the Y-maze spontaneous alternation test.

Novel object recognition (NOR) test

This test was conducted using a protocol based on modifications to the habituation phase34. The apparatus used was an open-field box (50 × 50 cm, Maze Engineers, Catalog #3201). Mice at 6 months of age underwent a habituation session in an empty arena, followed by a familiarization phase with two identical objects. Twenty-four hours later, one object was replaced with a novel object for the test phase. Exploration time was recorded, and the recognition index (RI) was calculated as the percentage of time spent exploring the novel object relative to the total exploration time. Data were analyzed using Anymaze software (Stoelting Co.), and the RI was used as an indicator of cognitive performance.

Y-maze spontaneous alternation test

This test was performed as described in Ohno et al.35 with minor modifications. The Y-maze apparatus (Maze Engineers) was constructed based on the specifications shown in the provided schematic: each arm measured 35 inches in length, 7 inches in width, and 35 inches in height, with a 120° angle between the arms. Mice were placed in the center of the maze and allowed to explore freely for 8 min. The sequence and total number of arm entries were recorded. An arm entry was considered valid when the mouse’s hind paws completely entered the arm. The percentage of spontaneous alternation was calculated as the number of triads (entries into all three arms in a row) divided by the maximum possible alternations (the total number of arm entries minus two) multiplied by 100. Behavior was recorded using a Logitech HD1080 video camera and analyzed using Anymaze software for tracking and computational analysis. The total number of arm entries and the percentage of spontaneous alternation were used as indicators of spatial working memory performance.

Immunofluorescence staining

Coronal sections were prepared from the right hemisphere of fixed brains and processed for immunofluorescence staining. Frozen coronal sections (40 μm thickness) were cut using a Shandon cryotome (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) from rostral to caudal regions of the brain. Sections were collected and stored in cryoprotectant solution (25% glycerol and 25% ethylene glycol in PBS) in 12-well plates until further use.

Before staining, brain sections were washed 3X with PBS to remove the cryoprotectant. Immunostaining was performed by incubating the sections with primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 in PBS containing 2% BSA, 2% goat or donkey serum, and 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-T). The primary antibodies used were anti-Aβ 6E10 (Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA), anti-Aβ42 (ThermoFisher Scientific), anti-Aβ40 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Iba1 (Wako, Richmond, VA, USA) and anti-DCX (doublecortin) (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-tubulin β III (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and anti-MAP2 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The next day, sections were washed 3X with PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated species-specific secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 3 h at room temperature. After secondary antibody incubation, sections were counterstained with Hoechst 33,258 (ThermoFisher Scientific) for nuclei visualization. Sections were then mounted on glass slides using Fluoromount-G (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) and cover-slipped.

Imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 700 Confocal Laser microscope system (Zeiss, Richmond, VA, USA). Image analysis was conducted to quantify amyloid plaque density, microglial proliferation, and hippocampal neurogenesis using methods previously described36,37.

Aβ42/40 ratio analysis

Quantification of Aβ40 and Aβ42 immunofluorescence was performed in the hippocampus and cortex. Regions of interest were outlined based on DAPI counterstaining, and mean fluorescence intensities of Aβ40, Aβ42, and total Aβ were extracted using ImageJ. Intensities were normalized to total Aβ within each section, and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was calculated for each animal. Average values per mouse were used for statistical comparisons between groups.

Microglia morphometric analysis

Microglial morphology was assessed in the hippocampus and cortex based on previously published methods38,39,40. For each group, three mice were analyzed. From each mouse, three 40-µm brain sections were obtained, and in each section, cells were imaged using a 40× confocal objective, and Z-stacks were acquired and projected to maximum intensity. 3–5 microglia per section were selected and binary isolated using ImageJ. Selection criteria included intact morphology and absence of overlap with neighboring cells. Specifically, in cortex FFWT n = 34, FPWT n = 40, FFAD n = 47, FPAD n = 39; in hippocampus FFWT n = 33, FPWT n = 36, FFAD n = 31, FPAD n = 32; with sampling balanced across animals to avoid bias.

Individual microglia were segmented in ImageJ/Fiji, and morphometric parameters were quantified using the Skeleton, FracLac, and Sholl Analysis plugins. Skeleton analysis provided total branch length, number of branches, and number of endpoints. FracLac analysis measured fractal dimension, lacunarity, density, span ratio, circularity, and soma size. Sholl analysis was performed on binary images with concentric circles drawn at 0.1 μm intervals from the soma center, and the number of intersections was quantified to evaluate arborization complexity. Group means were calculated per animal for statistical comparisons.

Western blot analysis

Hippocampal tissue was dissected from the left hemisphere and snap-frozen for later protein extraction and Western blot analysis. Hippocampal lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein (20 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against Synapsin or β-actin (loading control) (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence and quantified by densitometry using ImageQuant software. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin.

Gut permeability assay

Gut permeability was assessed using a fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (FITC-Dextran) assay41 with slight modification. FITC-Dextran 4000 (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 100 mg/ml and administered to mice via oral gavage at a dose of 44 mg per 100 g body weight. Mice were fasted for 4 h prior to administration. Four hours after FITC-Dextran administration, blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture under isoflurane anesthesia (4% for induction, 3% for maintenance). Approximately 300–400 µl of blood was collected from each mouse using heparinized syringes. Plasma was obtained by centrifuging the blood samples at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the plasma was stored at -80 °C until further analysis. Plasma samples were diluted 1:1 with PBS, and 100 µl of the diluted plasma was added in duplicate to a black 96-well microplate. FITC fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax Plate Reader M5 (Molecular Devices) with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 528 nm. A standard curve was generated using serial dilutions of FITC-Dextran (ranging from 125 ng/ml to 8,000 ng/ml), and the concentration of FITC-Dextran in the plasma was calculated from this standard curve. Results from this assay were used to assess gut permeability, with increased levels of FITC-Dextran in the plasma indicating higher gut permeability.

Lipidomic analysis

Lipids were extracted from 25 mg of fecal material by a modified Folch method42. Briefly, feces were homogenized in normal saline and mixed with chloroform (2:1). The mixtures were vortexed and centrifuged. After centrifugation, the lipid-containing lower liquid phase was carefully collected, dried under nitrogen (N₂), and resuspended in methanol for further analysis.

Phospholipids and sphingolipids analysis: Untargeted lipidomics were used to analyze phospholipids, sphingolipids, and glycerolipids. An aliquot of the extracted lipids was resuspended in a mixture of acetonitrile (CH₃CN), chloroform (CHCl₃), and methanol (MeOH) and injected into a Waters™ Aquity i-Class UPLC system coupled to a G2-XS QTof system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Data were acquired in MSE mode, using a high-to-low collision energy range to capture both precursor ions and fragments. Lipids were identified using MS-DIAL software, and molecular species were quantified as a percentage of the total lipid content in each sample.

Very Long-Chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (VLC-PUFAs): Both free and total VLC-PUFAs (after base hydrolysis) were identified and quantified using a Waters™ Premier HPLC system coupled to a TQ-Absolute mass spectrometer. The system operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Chromatographic separation was performed using an Acquity Premier CSH C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Lipid standards (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) were used for tuning and optimization.

Short-Chain fatty acids: Fecal samples were homogenized in methanol and derivatized for increased sensitivity using 2-picolylamine derivatization. The derivatized SCFAs were quantified using a Waters™ Premier HPLC system coupled to a TQ-Absolute mass spectrometer equipped with an Acquity BEH C18 column. The LC-MS system was operated in MRM mode.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise specified, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with genotype (WT vs. AD) and diet (FF vs. FP) as factors, followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparisons test to determine pairwise differences. This approach was applied to datasets with four groups (FFWT, FPWT, FFAD, FPAD). For microbial relative abundance data not conforming to normal distribution, group differences were first assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests with false discovery rate (FDR) correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. β-diversity was assessed using PERMANOVA (permutational multivariate ANOVA) based on distance matrices (e.g., Bray–Curtis). Sholl analysis of microglia morphology was evaluated using two-way repeated measures ANOVA with factors of group and distance from soma. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied for all analyses. Sample sizes (n) are reported in figure legends.

Results

Dietary fiber modulates gut microbiota composition

At the Phylum level, gut microbial composition showed clear differences across dietary and genotype groups. Relative abundance pie graph revealed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidota were the dominant phyla, with notable contributions from Actinobacteriota and Proteobacteria. Within these, importantly, Actinobacteriota abundance was significantly reduced in both FPAD and FPWT groups compared to their fiber-free counterparts (Fig. 1a).

Dietary fiber modulates gut microbiota composition in WT and AD mice. (a) Relative abundance of gut microbial communities across four experimental groups (FFWT, FPWT, FFAD, FPAD). Top: pie charts summarizing community composition at the Phylum level (taxonomic level 2) using group means; Bottom: stacked bar plots showing at the Genus level (taxonomic level 6) the relative abundance of the most prevalent genera. Notably, Actinobacteriota, an important phylum, was significantly reduced by fiber supplementation in both WT and AD mice. p < 0.01 (FPWT vs. FFWT and FPAD vs. FFAD), two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. (b) Relative abundance of selected genera with robust abundance and significant differences between groups. Ileibacterium and Muribaculaceae were consistently increased by fiber supplementation (FP vs. FF) in both WT and AD mice, whereas Faecalibaculum was reduced. Rikenella and Dubosiella were elevated in AD mice but suppressed by fiber supplementation (FPAD vs. FFAD). Bacteroides exhibited opposite responses to fiber in WT versus AD backgrounds. * p < 0.05 (FFAD vs. FFWT), ** p < 0.05 (FPAD vs. FFAD), p values for microbial abundance comparisons were obtained using two-way ANOVA (for normally distributed data) or Kruskal–Wallis followed by Mann–Whitney U test with FDR correction (for non-normally distributed data). (c) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity showing distinct clustering of microbial communities by both genotype and diet. Notably, FFAD and FPAD groups formed clearly separated clusters. Group separation was statistically validated by PERMANOVA (p < 0.05). Sample sizes: FFWT (n = 26), FPWT (n = 14), FFAD (n = 10), FPAD (n = 10).

At the Genus level, several taxa displayed marked shifts between groups. Analysis of selected genera with robust abundance and significant differences showed that Ileibacterium, Muribaculaceae (increase) and Faecalibaculum (decrease) were consistently altered by dietary fiber in both WT and AD mice, whereas Rikenella and Dubosiella were increased in AD mice but reduced by fiber supplementation (FPAD vs. FFAD). In contrast, Bacteroides exhibited opposite responses to fiber supplementation in WT and AD backgrounds (Fig. 1a & b). Additional genera, including Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (increase) and Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002 (decrease), also showed fiber-dependent changes in both WT and AD mice. For a comprehensive list of genera significantly altered across different comparisons, please refer to Supplementary Table 2.

Beta diversity analysis based on Bray–Curtis distances revealed distinct clustering according to dietary groups, with FP- and FF-fed mice forming separate clusters (Fig. 1c). A degree of separation between WT and AD mice was also observed within the same diet groups. Alpha diversity analysis using Faith’s phylogenetic diversity indicated higher diversity in FPAD compared to FFAD mice, whereas no significant differences were observed between FPWT and FFWT groups (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Cognitive function improvement with FP diet

To assess the impact of dietary fiber on cognitive performance, we conducted behavioral tests in 5xFAD mice. In the novel object recognition (NOR) test, FPAD mice showed a significantly higher preference for the novel object compared with FFAD mice, indicating improved recognition memory (Fig. 2a & b). In the Y-maze test, FPAD mice exhibited higher spontaneous alternation rates than FF-fed AD mice, reflecting enhanced spatial memory performance (Fig. 2c). Importantly, total travel distance during the Y-maze task did not differ significantly among groups (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that the observed cognitive improvements were not attributable to alterations in locomotor activity. These results demonstrate that FP supplementation improves both recognition and spatial memory in AD mice.

A fiber-supplemented diet improves recognition and spatial memory in 5xFAD mice. (a) Novel object recognition (NOR) test. FPAD mice exhibited a higher NOR index compared with FFAD mice, indicating improved recognition memory. (b) Representative track plot maps trace from NOR testing across groups. (c) Y-maze spontaneous alternation test. FPAD mice showed a higher alternation percentage compared with FFAD mice, reflecting enhanced spatial working memory. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (factors: genotype and diet) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, FFAD vs. FFWT; **p < 0.05, FPAD vs. FFAD. Sample size: n = 12 for each group.

Dietary fiber attenuates Aβ pathology and microgliosis in 5xFAD mice

Immunofluorescence staining revealed widespread Aβ deposition in the hippocampus and cortical regions of FFAD mice. Fiber supplementation markedly reduced both Aβ40 and Aβ42 signals (Fig. 3), with a more pronounced reduction of Aβ42. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was significantly decreased in both cortex and hippocampus of FPAD mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Dietary fiber reduces Aβ40 and Aβ42 deposition in 5xFAD mouse brain. Representative immunofluorescence images of Aβ species in brain sections from 6-month-old FFAD and FPAD mice. (a) Staining for total Aβ (red) and Aβ40 (green) in whole hemisphere, hippocampus, somatosensory cortex, and entorhinal cortex. (b) Staining for total Aβ (red) and Aβ42 (green) in the same brain regions. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Yellow boxes in hemisphere panels indicate regions magnified below. Scale bars: 300 μm (hemisphere), 50 μm (hippocampus and cortex). Quantification of Aβ burden and Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a. Data represent n = 5 mice per group, with four sections per brain region per mouse analyzed.

To further evaluate Aβ burden and microgliosis, whole hippocampus and whole cortex quantification were performed for total Aβ and Iba1, respectively (Fig. 4). As expected, Aβ levels were significantly higher in AD mice compared to WT controls. Importantly, FPAD mice exhibited a robust reduction of cortical and hippocampal Aβ intensity compared to FFAD mice (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Similarly, Iba1 immunoreactivity was elevated in FFAD brains but was significantly reduced in FPAD mice, indicating suppression of microglial activation (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

Fiber supplementation attenuates Aβ burden and microgliosis in cortex and hippocampus of 5xFAD mice. Representative immunofluorescence images of total Aβ (red) and Iba1⁺ microglia (green) in brain sections from 6-month-old mice. (a) Wild-type (FFWT and FPWT) groups. (b) 5xFAD (FFAD and FPAD) groups. Images include whole hemisphere, hippocampus, somatosensory cortex, and entorhinal cortex. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Yellow boxes in hemisphere panels indicate regions magnified below. Scale bars: 300 μm (hemisphere), 50 μm (hippocampus and cortex). Quantification of Aβ burden and Iba1 immunoreactivity is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4b and 4c. Data represent n = 5 mice per group, with four sections per brain region per mouse analyzed.

Morphometric analysis of microglial structure provided further evidence for fiber-mediated attenuation of AD-associated pathology (Fig. 5). Microglia from the cortex and hippocampus of FFAD mice showed a dystrophic and reactive phenotype characterized by reduced total branch length, branch number, and endpoints, together with enlarged soma size. By contrast, microglia from the same areas in FPAD mice exhibited a more ramified morphology, with significantly greater branching complexity, higher fractal dimension, and increased arborization in Sholl analysis, accompanied by smaller soma size. These data indicate that fiber supplementation mitigates Aβ pathology and microglial activation in AD brains.

Microglial morphometric analysis in cortex and hippocampus of WT and 5xFAD mice fed fiber-free (FF) or fiber-plus (FP) diets. (a) Representative binary-isolated microglia from cortex (top) and hippocampus (bottom), showing reduced branching and dystrophic morphology in FFAD mice, with restoration of more complex arborization in FPAD mice. (b, c) Quantitative morphometric parameters in cortex (b) and hippocampus (c). Confocal z-stack images (40×, maximum projections) were processed in ImageJ to isolate individual cells, followed by analysis using dedicated plugins: Skeleton analysis (total branch length, number of branches, number of endpoints), FracLac (fractal dimension, density, span ratio, lacunarity, circularity), and Sholl analysis (number of intersections across concentric circles at 0.1 μm intervals from soma center). Soma size was also measured. For cortical analysis, total cells quantified were FFWT n = 34, FPWT n = 40, FFAD n = 47, FPAD n = 39; for hippocampus: FFWT n = 33, FPWT n = 36, FFAD n = 31, FPAD n = 32. Cells were collected from 3 mice per group (3 sections per mouse, 3–5 cells per section), with sampling balanced across groups. Statistical analysis: Unless otherwise indicated, two-way ANOVA (factors: genotype and diet) with Tukey’s post hoc test was applied. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, FFAD vs. FFWT; **p < 0.05, FPAD vs. FFAD. Sholl analysis was evaluated separately using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (within-subject factor: distance from soma), which revealed a significant separation of FFAD curves from the other three groups (p < 0.01).

Neuroprotection by FP diets in 5xFAD mice

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) declines in AD, contributing to cognitive deficits43,44. In this study, we examined whether an FP diet could promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus of 5xFAD mice using DCX (doublecortin) staining to identify newly generated neurons. FPAD mice displayed increased DCX + neurons in the dentate gyrus compared to FFAD mice (Fig. 6), suggesting enhanced neurogenesis. The observed increase in hippocampal neurogenesis may partially explain the improved memory performance in the FP-fed AD mice, further supporting the role of dietary fiber in modulating brain plasticity. Dietary fiber also demonstrated neuroprotective effects in hippocampus reflected in β-tubulin III and MAP2 neuronal marker staining that show better preserved dendritic fibers in CA1 region of FP diet-fed mice hippocampus relative to FF-fed counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 5). Additionally, in the hilus of the dentate gyrus, FP-fed mice exhibited a denser network of MAP-2-positive neurons and dendritic fibers (Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting that dietary fiber promotes neuronal connectivity and hippocampal integrity in AD models.

Fiber-rich diet preserves adult hippocampal neurogenesis in 5xFAD mice. Representative immunofluorescent images of DCX (green) with or without DAPI counterstaining (blue) in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus from 6-month-old WT and 5xFAD mice under fiber-free (FF) or fiber-plus (FP) diets. Quantification of DCX⁺ newborn neurons per region of interest (ROI) revealed a marked reduction in FFAD mice, which was significantly rescued by FP diet (right panel). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 5 mice per group. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (factors: genotype and diet) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, FFAD vs. FFWT; **p < 0.05, FPAD vs. FFAD. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Synaptic loss is a hallmark of AD and closely correlates with cognitive decline45. To assess whether an FP diet affects synaptic integrity, we measured synapsin-1 (SYN1) expression in the hippocampus using Western blotting. Our results showed that FPAD mice had higher SYN1 levels compared to FF-fed AD mice (Supplementary Figs. 6 & 7).

Together, these findings emphasize the capacity of dietary fiber to modulate hippocampal architecture, enhance neuronal regeneration, and preserve neural connectivity, providing a mechanistic link between dietary interventions and neuroprotection in AD.

Gut permeability improvement with FP diet

Increased gut permeability, or “leaky gut,” has been associated with systemic inflammation and neurodegeneration, including AD46,47. To assess the effect of dietary fiber on gut permeability, we performed a FITC-dextran permeability assay. AD mice fed with fiber free diet (FFAD) exhibited markedly higher intestinal permeability compared to WT controls (FFWT), as evidenced by elevated FITC-dextran concentrations in the serum (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, dietary fiber supplementation significantly attenuated this increase, with FPAD mice showing reduced gut permeability compared to FFAD mice. These findings indicate that dietary fiber helps maintain gut barrier integrity in AD, which may contribute to its anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects.

Fecal lipid analysis: phospholipids, FFAs, and SCFAs

To further investigate the metabolic effects of an FP diet, we performed lipidomic analysis on fecal samples, focusing on phospholipids, FFAs, total fatty acids (TFA), and SCFAs.

Fecal phospholipids (PE, SM, PC, LPC, TG, DG) showed changes after transitioning from the standard chow diet to custom diets, although no differences were observed between FP and FF groups. Phospholipid ratios exhibited distinct patterns: the LPC/PC ratio increased between 4 and 6 months across all groups, while FP diets elevated PE/PC and SM/PC ratios compared to FF diets, suggesting enhanced phospholipid metabolism under FP conditions. These effects were absent in WT mice, indicating potential AD-specific responses. The TG/DG ratio significantly decreased following the diet transition, reflecting changes in lipid metabolic dynamics (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Fecal lipidomic profiles in WT and AD mice across diets and ages. Fecal lipids were extracted using a modified Folch method and analyzed via untargeted lipidomics. Bar graphs show the relative abundance of triglycerides (TG), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), phosphatidylcholines (PC), sphingomyelins (SM), phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), and diacylglycerols (DG). White bars with red circles indicate WT mice, and purple bars with blue circles indicate AD mice. At 1 month (1 M), WT and AD mice (n = 8/group) were analyzed while maintained on standard chow diet, serving as the baseline prior to dietary intervention. Mice were fed custom fiber-free (FF) or fiber-plus (FP) diets for 3 or 5 months (4 and 6 months of age), respectively (n = 3–4/group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA (factors: genotype and diet) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, with comparisons indicated by black connecting lines.

On FFAs, FP-fed AD mice at 6 months exhibited higher DHA and EPA levels compared to FF-fed AD mice, alongside increased AA levels, highlighting complex lipid profile changes. Transitioning to custom diets resulted in increased DHA, EPA, AA, and 24:6 n3 (tetracosahexaenoic acid; THA) levels, with a concurrent decrease in FA 18:3 n3 (alpha-linolenic acid; ALA) (Fig. 8). TFA changes were more limited; however, 22:5 n3 (EPA) levels increased post-transition and between 4 and 6 months, suggesting a time-dependent regulatory effect (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Effects of diet and genotype on fecal free fatty acid (FFA) profiles. Fecal FFAs were extracted using a modified Folch method and analyzed via untargeted lipidomics. Panels show the relative abundance of major FFAs (DHA, EPA, arachidonic acid [AA], FA 18:3 n3, 22:5 n3, and 24:6 n3) across groups: WT and AD mice at 1 month of age on standard chow diet (baseline), and at 4 or 6 months of age after transition to custom fiber-free (FF) or fiber-plus (FP) diets. White bars with red circles indicate WT mice, purple bars with blue circles indicate AD mice. Sample sizes were n = 8 for 1-month chow-fed WT and AD groups, and n = 3–4 mice/group for 3- and 5-month (4 and 6 months of age) custom diet groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, with brackets indicating the groups compared.

SCFAs, including 2-methylbutyric acid, butyric acid, and isobutyric acid, showed distinct patterns in response to diet and age. 2-methylbutyric acid was markedly elevated when mice were switched from standard chow to the FF diet, but this increase was not observed when switched to the FP diet. Moreover, FP-fed mice consistently showed reduced levels of 2-methylbutyric acid compared with FF-fed counterparts, in AD groups while a notable trend in WT was observed as well (Supplementary Fig. 11). In contrast, butyrate and isobutyrate exhibited time-dependent increases, with higher levels observed at 6 months compared to 4 months across all groups, independent of diet or genotype (Supplementary Fig. 11). Notably, despite the prevailing notion that dietary fiber exerts its effects primarily through classical SCFAs (acetate, propionate, and butyrate), our fiber-supplemented diets did not significantly alter the levels of these canonical metabolites compared with fiber-free controls.

Collectively, the fecal lipid analysis demonstrates that dietary interventions and time modulate gut lipid profiles, with distinct responses observed across phospholipids, free fatty acids, and SCFAs. Transitioning from a standard chow diet to custom FP and FF diets led to pronounced changes in lipid composition, with FP diets showing enhanced levels of neuroprotective lipids such as DHA and EPA, particularly in AD mice. Time-dependent effects, including increases in LPC/PC ratios, butyric acid, and 22:5 n3, suggest additional age or developmental influences on lipid metabolism. These findings underscore the complexity of diet-gut-lipid interactions, highlighting their potential relevance to AD pathology.

Discussion

AD is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration, primarily driven by Aβ plaque deposition, tau misfolding, aggregation, neurofibrillary tangles, neuroinflammation, and lipid metabolism dysregulation11,45,48,49. In recent years, the gut-brain axis has emerged as a significant factor in AD pathophysiology50,51, with increased emphasis on dietary interventions, such as fiber intake, that modulate gut microbiota and subsequent brain health outcomes52,53. Here, we have uncovered that an FP diet supplemented with fibers, including pectin and inulin, regulates gut microbiota, lipid metabolism, AD pathology (including Aβ deposition, microglia activation, and neurodegeneration), and cognitive function in 5xFAD mice.

This fiber composition (1% cellulose, 2% pectin, and 2% inulin) was selected based on a previously published study32, where this combination was shown to effectively modulate gut microbiota and promote SCFA production. Cellulose was included as a non-fermentable bulking agent to aid intestinal transit. The total fiber content (~ 5%) is comparable to the crude fiber level typically present in conventional chow diets, providing physiological relevance while maintaining experimental control. Importantly, the FF and FP diets are otherwise identical in composition, allowing us to specifically assess the effects of dietary fiber without the confounding variability inherent in chow diets that contain undefined components. This design therefore provides a relevant and controlled framework to examine how dietary fiber influences gut microbiota, lipid metabolism, and AD pathology.

Our study revealed significant microbial composition changes in mice fed with fiber supplemented diet. At the phylum level, we observed a marked reduction of Actinobacteriota in both WT and AD mice after fiber supplementation, suggesting that fiber intake reshapes microbial communities even at higher taxonomic levels. More differential changes were revealed at the genus level by FP diet. For example, Muribaculaceae and Ileibacterium were robustly increased in both WT and AD mice under FP diets. Both taxa are recognized for their capacity to utilize complex polysaccharides and contribute to SCFA production, suggesting that their enrichment may underlie fiber-driven metabolic and anti-inflammatory benefits54,55,56. Notably, similar features of a “youth-like” gut microbiome have also been observed in the oldest documented centenarian that reached 117 years of age, where enrichment of Bifidobacterium and reduced pro-inflammatory signatures were linked to healthy aging57. By contrast, Faecalibaculum was consistently reduced following FP supplementation. While this genus is often abundant in rodent gut microbiota, previous studies have associated its overrepresentation with intestinal inflammation and metabolic imbalance, and it is known to be associated with depression like symptoms58, raising the possibility that its suppression reflects a shift toward a healthier microbial community. Interestingly, A similar pattern of changes in microbial abundance was observed in a recent study using a traditional Chinese medicine intervention for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), where Ileibacterium enrichment and Faecalibaculum suppression were associated with improved gut barrier integrity, metabolic homeostasis, and potentially inosine-mediated protective pathways59. Moreover, Rikenella and Dubosiella, which were enriched in AD mice, were markedly decreased under FP diets. Both taxa have been implicated in pro-inflammatory responses and AD-associated microbiota dysbiosis, suggesting that their reduction may represent a microbiota-mediated mechanism contributing to the attenuation of neuroinflammation50,60. Particularly, Rikenella has been suggested to be a biomarker for AD in a study using APP/PS1 mice61. However, recent work reported that Dubosiella, although enriched in AD mice, may exert compensatory effects by modulating cortical palmitoleic acid, a metabolite with anti-inflammatory and metabolic protective properties, suggesting that the role of this genus in AD is complex and potentially context-dependent62. Moreover, Bacteroides showed divergent responses: enriched in FP-fed WT mice but reduced in FP-fed AD mice. This context-dependent behavior is consistent with the dual role of Bacteroides, which can serve as beneficial commensals in healthy hosts but may exacerbate pathology under AD conditions63. Finally, additional fiber-responsive taxa, including Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002, also exhibited consistent modulation in both WT and AD backgrounds. Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group has been identified as a fiber-responsive beneficial genus and biomarker for better prognosis in stroke patients64; while Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002 was implicated in intestinal barrier disruption and pro-inflammatory responses65. It is worth noting that AD mice exhibited slightly lower body weights compared to WT mice, consistent with a genotype effect. However, as dietary intervention did not alter body weight and all microbiome and metabolic analyses were performed within genotype-matched comparisons, this difference does not affect the interpretation of fiber-specific effects. Together, these results support the concept that FP diets selectively remodel gut microbiota across both phylum and genus levels, thereby promoting a microbial environment favorable for metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects. Consistent with these compositional changes, FP supplementation also enhanced overall microbial diversity, particularly restoring reduced α-diversity in AD mice and driving clear β-diversity separation between FP- and FF-fed groups. However, the roles of individual taxa remain complex and, in many cases, context-dependent and controversial. Thus, while our findings point to reproducible microbial shifts associated with fiber intake, further mechanistic studies are required to delineate the precise functional contributions of these taxa.

Behavioral assessments demonstrated improved cognitive function in FP-fed AD mice. In both the NOR and Y-maze tests, these mice showed enhanced recognition and spatial memory, confirming the protective effects of dietary fiber. In addition to cognitive improvements, our study provides direct evidence that dietary fiber supplementation mitigates hallmark AD pathology in 5xFAD mice. We observed a significant reduction in Aβ deposition and microgliosis, together with restoration of the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. Importantly, we adopted an analytical approach in which Aβ42 and Aβ40 staining intensities were normalized to total Aβ load, thereby minimizing variability due to antibody sensitivity differences. Within the context of immunofluorescence histology, this strategy offers an advantage over conventional comparisons of raw signal intensities, as it provides a more internally controlled estimate of the relative burden of Aβ species in defined brain regions66. Moreover, detailed morphological analyses of microglia revealed that fiber supplementation attenuated the transition toward an activated amoeboid phenotype, preserving more ramified structures. The observed improvements in cognitive performance align with reduced Aβ deposition and microgliosis in the brain, reinforcing the role of dietary interventions in modulating AD pathology. These results are consistent with findings from other studies showing that dietary fibers can reduce amyloid burden and promote synaptic plasticity, potentially through anti-inflammatory and neuroprotection-promoting pathways19. Additionally, hippocampal neurogenesis, as evidenced by increased DCX + neurons, was significantly enhanced in FPAD mice. Neurogenesis is often impaired in AD43,44, and the ability of dietary fiber to promote new neuron formation further supports its neuroprotective potential. Another key finding was the improvement in gut permeability in FP-fed mice, as evidenced by reduced FITC-dextran leakage. This suggests that dietary fiber helps maintain gut barrier integrity, which is crucial in preventing systemic inflammation—a known contributor to AD progression67,68. Gut permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut,” has been implicated in exacerbating neuroinflammation by allowing pro-inflammatory molecules to enter circulation and affect the brain46,47,69.

Contrary to previous reports, we found a lack of substantial changes in major SCFA levels in fecal samples of FP-fed mice, which is in contrast with other studies using different types of fibers25,26. Several factors could explain this discrepancy. First, previous studies showing substantial SCFA increases often used significantly higher levels of fibers like Agave tequilana-derived fructans or resistant starch, which are more easily fermented by the gut microbiota into SCFAs26. In our study, we use pectin and inulin, two commonly consumed soluble fibers with complementary properties70. Pectin is a soluble fiber found in fruits like apples and citrus, known for its gel-forming properties and slower fermentation rates49,71,72. Its main benefit lies in enhancing gut barrier integrity and reducing inflammation by interacting with mucosal layers and immune cells73,74. Pectin promotes gut health even in cases where SCFA levels do not increase72. This is relevant to our findings, as the absence of notable SCFA changes suggests that pectin’s SCFA-independent effects, such as improving gut permeability and reducing systemic inflammation, may play a key role in the observed neuroprotective effects. In line with this concept, other interventions targeting gut health, such as gallic acid supplementation, have also been shown to ameliorate intestinal inflammation by modulating the microbiota, enhancing barrier integrity, and reducing pro-inflammatory signaling75. Such effects may be mediated by microbial metabolites and chemokine regulation rather than SCFA alone. Inulin, a prebiotic fiber found in plants like chicory root, is more fermentable than pectin and can stimulate the growth of beneficial gut bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus71,76,77,78. These bacteria, although capable of producing SCFAs like acetate and butyrate, are also involved in broader metabolic processes, including the modulation of lipid metabolism79,80. Our study revealed changes in fecal lipids, particularly increases in DHA and EPA, which suggests that inulin may have influenced lipid absorption and metabolism, contributing to the beneficial effects on neuroinflammation and cognitive function. The decision to use this combination of fibers reflects a strategic focus on exploring SCFA-independent mechanisms that involve gut permeability, lipid metabolism, and immune modulation81,82. This approach allowed us to investigate whether dietary fibers could impact AD pathology through pathways beyond traditional SCFA production, offering new insights into how fiber can modulate brain health and neuroprotection. Another factor is the high content of dextrose monohydrate in our diet, which might have influenced gut microbial fermentation. Sugar is an energy source for microbes, potentially diverting their focus from fiber fermentation to sugar metabolism. Studies have shown that high-sugar diets can suppress SCFA production by altering microbial composition, reducing the abundance of fiber-fermenting bacteria83,84. This may explain why we did not observe the expected SCFA increases despite a fiber-rich diet. Lastly, despite dietary fiber replacing part of the sugar content in FP diet, the fiber-to-sugar ratio was still relatively lower compared to other studies where FP content led to significant SCFA production. The competing effects of high sugar likely reduced the fiber’s fermentative impact, leading to lower SCFA levels.

Interestingly, although classical SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate remained largely unchanged across dietary groups, we identified notable shifts in non-canonical SCFAs. Among these, 2-methylbutyric acid emerged as the most fiber-sensitive metabolite: its levels were markedly elevated in mice switched from standard chow to the FF diet, but this increase was absent in those switched to the FP diet. Furthermore, FP-fed mice consistently displayed lower 2-methylbutyric acid compared to their FF-fed counterparts. This pattern suggests that dietary fiber may redirect microbial metabolism away from protein fermentation toward carbohydrate utilization, thereby reducing the generation of potentially detrimental protein-derived metabolites. Since 2-methylbutyric acid is a branched-chain SCFA derived primarily from fermentation of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) like valine and isoleucine, its suppression with fiber supplementation likely reflects a shift away from amino acid fermentation. Although the precise physiological roles of 2-methylbutyric acid remain incompletely understood, its reproducible reduction with fiber intake highlights it as a potential metabolic marker of fiber status in the gut. In contrast, butyrate and isobutyrate exhibited consistent age-associated increases, with significantly higher levels at 6 months compared to 4 months, independent of diet or genotype. These findings suggest that while our fiber-supplemented diets did not markedly alter the canonical SCFA pool, they exerted a selective effect on branched-chain SCFA metabolism, particularly restraining the elevation of 2-methylbutyric acid linked to fiber deficiency.

Additional alterations in lipid metabolism were observed, particularly the increase in DHA and EPA levels in fecal samples. These omega-3 fatty acids are well-known for their anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, which are critical in the context of AD85,86. Both DHA and EPA are associated with reducing neuroinflammation and amyloidosis, improving synaptic function and cognitive outcomes87,88,89,90,91. The presence of soybean oil in our diet likely provided the necessary PUFA precursors—linoleic acid (LA) and ALA—which are metabolized into DHA and EPA92. The observed increase in these fatty acids suggests that the FP diet modulated lipid metabolism, favoring anti-inflammatory lipid profiles. A higher DHA is crucial, as DHA reduces neuroinflammation93. This modulation of lipid metabolism could represent a SCFA-independent mechanism through which dietary fiber exerts neuroprotection. Previous studies have demonstrated that microbial metabolites can cross into systemic circulation and impact brain lipid composition, blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, and neuroinflammation94. In particular, SCFAs like butyrate have been shown to regulate BBB function and modulate inflammatory signaling in neurodegenerative conditions95. The increased DHA and EPA levels observed in FP-fed AD mice may similarly contribute to neuroprotection by modulating inflammatory pathways and supporting synaptic membrane composition. In addition, the recent multi-omics study identified a positive association between Dubosiella abundance and cortical palmitoleic acid (a monounsaturated fatty acid with anti-inflammatory properties) in AD mice, suggesting that microbiota–lipid interactions beyond SCFAs may represent an underexplored but important mechanism in AD pathophysiology62.

The time-dependent increase in certain lipids, such as 22:5 n3 (docosapentaenoic acid; DPA), a long-chain omega-3 fatty acid that serves as an intermediary in the metabolic pathway from EPA (20:5 n3) to DHA96, across all groups highlights the influence of age or developmental processes on lipid metabolism. This finding suggests that intrinsic host factors, such as age-related changes in gut microbiota or lipid metabolic pathways, may interact with dietary interventions to shape lipid profiles. Furthermore, the differential responses between FP and FF diets underscore the dietary modulation of specific lipid classes, including SCFAs and PUFAs. Interestingly, the genotype-specific effects observed in AD mice suggest that disease-related alterations in gut microbiota or host lipid metabolism might amplify dietary impacts.

Moreover, changes in the phospholipid ratios (e.g., PE/PC and SM/PC ratios) suggest that dietary fiber may have influenced membrane fluidity and structural integrity. PC and SM are crucial components of neuronal membranes, and their modulation may affect membrane stability, signaling, and synaptic function97,98. The increase in SM/PC ratio observed in our study could be indicative of modulatory changes in membrane composition, enhancing neuronal resilience against AD-related damage16.

The gut-brain-lipid axis emerges as a key pathway in understanding the link between dietary interventions and neurodegenerative diseases. The observed elevation in DHA, EPA, and butyrate under FP diets aligns with their known roles in reducing neuroinflammation and promoting neuronal health. However, the concurrent increase in AA under FP diets highlights the complexity of lipid interactions, as AA serves as a substrate for cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) pathways, giving rise to prostaglandins and leukotrienes that drive pro-inflammatory signaling, while also generating lipoxins and other mediators that contribute to the resolution of inflammation and tissue homeostasis99. Thus, the observed increase in AA in FPAD mice may reflect dietary modulation of lipid metabolism with potential consequences for the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory eicosanoids. These findings suggest that dietary modulation of gut microbiota and lipid metabolism could provide a therapeutic avenue for managing AD, particularly by targeting specific lipid pathways to enhance anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects.

While our study provides insights into the effects of dietary fiber on lipid metabolism and AD pathology, several limitations warrant further investigation. For example, although 16 S rRNA sequencing provided reliable information on microbiota composition, it does not fully resolve microbial functional capacity; integration of shotgun metagenomics with metabolomics will be important in future studies. Adding an antibiotic-treated group followed by fecal microbiota transplantation experiments would more directly establish causality between microbial changes and host outcomes. Also, the relatively low fiber-to-sugar ratio in our diet may have diminished the potential SCFA increases, which raises the question of whether different fiber compositions or higher fiber doses could have yielded different outcomes. Future studies should explore the effects of various fiber types and doses on both SCFA production and lipid metabolism in the context of AD.

Another limitation of our study is the lack of liver tissue data, which precluded analysis of hepatic lipid metabolism. Considering the established crosstalk between the gut microbiota and host lipid metabolism, particularly through microbial metabolites such as SCFAs and bile acids, the liver represents a downstream organ that may be affected by dietary fiber intervention. Alterations in hepatic lipid processing, lipogenesis, or inflammation could play a role in mediating the systemic effects observed in our study. We suggest that future studies should include liver profiling—both histological and molecular—to better define the gut–liver–brain axis in the context of neurodegeneration. Additionally, the study is limited by the fact that intestinal samples were not collected, preventing direct assessment of tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1, occludin, claudin). Future studies should incorporate such molecular markers to complement the functional permeability assay.

It should be acknowledged that the 5xFAD transgenic mouse model, while widely used, represents an aggressive form of AD driven by multiple familial mutations, which may not fully capture the multifactorial and sporadic nature of human disease. Nevertheless, this model recapitulates key pathological features, such as early amyloid deposition and neuroinflammation, allowing for controlled assessment of dietary interventions. Our findings, therefore, provide proof-of-concept evidence that dietary fiber supplementation can modulate gut microbiota and lipid metabolism in ways that may be relevant to human AD, although further validation in clinical studies is needed. Furthermore, our experiments were all performed in male mice, which represents another limitation, as sex-specific differences in gut microbiota and AD pathology have been reported.

Finally, while we observed changes in DHA and EPA, future research should focus on elucidating these pathways, particularly the interaction between gut microbiota and lipid metabolism in the brain. Direct measurements of circulating and brain lipid levels, coupled with mechanistic studies on gut microbiota-lipid interactions, would provide insights into the gut-brain-lipid axis. Additionally, exploring the therapeutic potential of bioactive lipid supplementation or microbiota-targeted interventions could pave the way for personalized strategies to mitigate AD pathology.

Conclusion

In summary, dietary fiber supplementation with pectin and inulin reshaped gut microbiota, remodeled lipid metabolism, improved gut barrier function, and attenuated key AD hallmarks, including Aβ deposition, microglial activation, and impaired neurogenesis. While SCFA levels remained unchanged, shifts in other lipid metabolites suggest alternative protective mechanisms beyond classical fermentation. These findings identify common dietary fibers, at physiologically relevant doses, as modifiers of the gut–brain axis with translational potential for AD prevention and therapy.

Data availability

The gut microbiome sequencing datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession PRJNA1219705 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1219705). All other data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

No custom code was generated during the analysis of the microbiota sequencing data. All bioinformatics analyses were performed using standard software tools, including QIIME2 and Illumina BaseSpace.

References

Sheppard, O. & Coleman, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Etiology, neuropathology and pathogenesis. in Alzheimer’s Disease: Drug Discovery (ed Huang, X.) (Exon, Brisbane (AU), (2020).

Seo, D. O. & Holtzman, D. M. Current Understanding of the alzheimer’s disease-associated Microbiome and therapeutic strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 86–94 (2024).

Simão, D. O., Vieira, V. S., Tosatti, J. A. G., Gomes, K. B. & Lipids Gut Microbiota, and the complex relationship with alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Nutrients 15, 4661 (2023).

Socała, K. et al. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 172, 105840 (2021).

Afzaal, M. et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 13, 999001 (2022).

Chen, Y., Zhou, J. & Wang, L. Role and mechanism of gut microbiota in human disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 625913 (2021).

Susmitha, G. & Kumar, R. Role of microbial dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 229, 109478 (2023).

Hur, K. Y. & Lee, M. S. Gut microbiota and metabolic disorders. Diabetes Metab. J. 39, 198–203 (2015).

Goyal, D., Ali, S. A. & Singh, R. K. Emerging role of gut microbiota in modulation of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration with emphasis on alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 106, 110112 (2021).

Do, K. V. et al. Elovanoids counteract oligomeric β-amyloid-induced gene expression and protect photoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 116, 24317–24325 (2019).

Yin, F. Lipid metabolism and alzheimer’s disease: clinical evidence, mechanistic link and therapeutic promise. FEBS J. 290, 1420–1453 (2023).

Chew, H., Solomon, V. A. & Fonteh, A. N. Involvement of lipids in alzheimer’s disease pathology and potential therapies. Front. Physiol. 11, 598 (2020).

Luo, Y. X., Yang, L. L. & Yao, X. Q. Gut microbiota-host lipid crosstalk in alzheimer’s disease: implications for disease progression and therapeutics. Mol. Neurodegener. 19, 35 (2024).

Brown, E. M., Clardy, J. & Xavier, R. J. Gut Microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell. Host Microbe. 31, 173–186 (2023).

Zhu, H., Lu, R., Zhou, Q., Du, Z. & Jiang, Y. Relationship between sphingomyelin and risk of alzheimer’s disease: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 7, 1289–1297 (2023).

Akyol, S. et al. Lipid profiling of alzheimer’s disease brain highlights enrichment in Glycerol(phospho)lipid, and sphingolipid metabolism. Cells 10, 2591 (2021).

Alessenko, A. V. & Albi, E. Exploring sphingolipid implications in neurodegeneration. Front. Neurol. 11, 437 (2020).

Prokopidis, K., Giannos, P., Ispoglou, T., Witard, O. C. & Isanejad, M. Dietary fiber intake is associated with cognitive function in older adults: data from the National health and nutrition examination survey. Am. J. Med. 135, e257–e262 (2022).

Frausto, D. M., Forsyth, C. B., Keshavarzian, A. & Voigt, R. M. Dietary regulation of Gut-Brain axis in alzheimer’s disease: importance of microbiota metabolites. Front. Neurosci. 15, 736814 (2021).

Vinelli, V. et al. Effects of dietary fibers on Short-Chain fatty acids and gut microbiota composition in healthy adults: A systematic review. Nutrients 14, 2559 (2022).

Xu, T. et al. The regulatory roles of dietary fibers on host health via gut microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 62, 36–42 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. Dietary cellulose prevents gut inflammation by modulating lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 11, 944–961 (2020).

Makki, K. et al. 6α-hydroxylated bile acids mediate TGR5 signalling to improve glucose metabolism upon dietary fiber supplementation in mice. Gut 72, 314–324 (2023).

Jie, F., Yang, X., Wu, L., Wang, M. & Lu, B. Linking phytosterols and oxyphytosterols from food to brain health: origins, effects, and underlying mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 3613–3630 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Dietary fiber and microbiota metabolite receptors enhance cognition and alleviate disease in the 5xFAD mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 43, 6460–6475 (2023).

Cuervo-Zanatta, D. et al. Dietary fiber modulates the release of gut bacterial products preventing cognitive decline in an alzheimer’s mouse model. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 43, 1595–1618 (2023).

García-Villalba, W. G. et al. Agave fructans: a review of their technological functionality and extraction processes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 60, 1265–1273 (2023).

Gałkowska, D., Kapuśniak, K. & Juszczak, L. Chemically modified starches as food additives. Molecules 28, 7543 (2023).

Wallis, T. P. & Meunier, F. A. Phospholipase modulation of synaptic membrane landscape: driving force behind memory formation? Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 16, a041405 (2024).

Bazan, N. G. Docosanoids and elovanoids from omega-3 fatty acids are pro-homeostatic modulators of inflammatory responses, cell damage and neuroprotection. Mol. Aspects Med. 64, 18–33 (2018).

Kalinichenko, L. S., Gulbins, E., Kornhuber, J. & Müller, C. P. Sphingolipid control of cognitive functions in health and disease. Prog Lipid Res. 86, 101162 (2022).

Sivaprakasam, S. et al. An essential role of Ffar2 (Gpr43) in dietary fibre-mediated promotion of healthy composition of gut microbiota and suppression of intestinal carcinogenesis. Oncogenesis 5, e238 (2016).

Saleh, Z. M. et al. Limosilactobacillus reuteri ameliorates maternal separation stress in newborn mice and alters subsequent adult behaviour. Benef Microbes. 16, 221–235 (2024).

Leger, M. et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2531–2537 (2013).

Ohno, M. et al. BACE1 deficiency rescues memory deficits and cholinergic dysfunction in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 41, 27–33 (2004).

Chen, R. et al. Monoacylglycerol lipase is a therapeutic target for alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Rep. 2, 1329–1339 (2012).

Zhao, Y. et al. Wnt3a, a protein secreted by mesenchymal stem cells is neuroprotective and promotes neurocognitive recovery following traumatic brain injury. Stem Cells. 34, 1263–1272 (2016).

Young, K. & Morrison, H. Quantifying microglia morphology from photomicrographs of immunohistochemistry prepared tissue using ImageJ. J. Vis. Exp. 57648 https://doi.org/10.3791/57648 (2018).

Green, T. R. F., Murphy, S. M. & Rowe, R. K. Comparisons of quantitative approaches for assessing microglial morphology reveal inconsistencies, ecological fallacy, and a need for standardization. Sci. Rep. 12, 18196 (2022).

Chen, K. et al. Quantitative analysis of microglia morphological changes in the hypothalamus of chronically stressed rats. Brain Res. Bull. 206, 110861 (2024).

Volynets, V. et al. Assessment of the intestinal barrier with five different permeability tests in healthy C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 61, 737–746 (2016).

Kraus, D., Yang, Q. & Kahn, B. B. Lipid extraction from mouse feces. Bio Protoc. 5, e1375 (2015).

Choi, S. H. & Tanzi, R. E. Adult neurogenesis in alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus 33, 307–321 (2023).

Salta, E. et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in alzheimer’s disease: A roadmap to clinical relevance. Cell. Stem Cell. 30, 120–136 (2023).

Ju, Y. & Tam, K. Y. Pathological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res. 17, 543–549 (2022).

Zhao, Y. & Lukiw, W. J. Bacteroidetes neurotoxins and inflammatory neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 9100–9107 (2018).

Zhao, Y., Jaber, V. & Lukiw, W. J. Secretory products of the human GI tract Microbiome and their potential impact on alzheimer’s disease (AD): detection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in AD hippocampus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 318 (2017).

Bazan, N. G., Molina, M. F. & Gordon, W. C. Docosahexaenoic acid signalolipidomics in nutrition: significance in aging, neuroinflammation, macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 31, 321–351 (2011).

Guo, T. et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 40 (2020).

Harach, T. et al. Reduction of Abeta amyloid pathology in APPPS1 Transgenic mice in the absence of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 7, 41802 (2017).

Vogt, N. M. et al. Gut Microbiome alterations in alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 7, 13537 (2017).

Cronin, P., Joyce, S. A., O’Toole, P. W. & O’Connor, E. M. Dietary fibre modulates the gut microbiota. Nutrients 13, 1655 (2021).

Ticinesi, A. et al. Interaction between diet and microbiota in the pathophysiology of alzheimer’s disease: focus on polyphenols and dietary fibers. J. Alzheimers Dis. 86, 961–982 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Exploration of the muribaculaceae family in the gut microbiota: Diversity, Metabolism, and function. Nutrients 16, 2660 (2024).

Zhou, D., Kei, N. & Cheung, P. C. K. Prebiotic oat β-glucan ameliorates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis in a dose-dependent manner. Food Bioscience. 71, 107154 (2025).

He, L. et al. Hericium Erinaceus peptide KSPLY protects gastric mucosal barrier and reshapes gastric microbiota in mice. J. Funct. Foods. 133, 106983 (2025).

Santos-Pujol, E. et al. The multiomics blueprint of the individual with the most extreme lifespan. Cell Rep. Medicine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102368

Wang, S. et al. Ingestion of faecalibaculum rodentium causes depression-like phenotypes in resilient Ephx2 knock-out mice: A role of brain-gut-microbiota axis via the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve. J. Affect. Disord. 292, 565–573 (2021).

Qiu, J. et al. Xie Zhuo Tiao Zhi formula modulates intestinal microbiota and liver purine metabolism to suppress hepatic steatosis and pyroptosis in NAFLD therapy. Phytomedicine 121, 155111 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. Organophosphate insecticide malathion induces alzheimer’s Disease-Like cognitive impairment in mice: evidence of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain axis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 21966–21977 (2024).

Feng, M. et al. Gut microbiota May be involved in alzheimer’s disease pathology by dysregulating pyrimidine metabolism in APP/PS1 mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 967747 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Gut microbiota-driven metabolic alterations reveal gut-brain communication in alzheimer’s disease model mice. Gut Microbes. 16, 2302310 (2024).

Wasén, C. et al. Bacteroidota inhibit microglia clearance of amyloid-beta and promote plaque deposition in alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat. Commun. 15, 3872 (2024).

Zhu, A. et al. Causal effects of gut microbiota on the prognosis of ischemic stroke: evidence from a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1346371 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Li, D., Xie, F., Muhetaer, G. & Zhang, H. The cause-and-effect relationship between gut microbiota abundance and carcinoid syndrome: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1291699 (2023).

Andersson, E. et al. Soluble cerebral Aβ protofibrils link Aβ plaque pathology to changes in CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios, neurofilament light and Tau in alzheimer’s disease model mice. Nat. Aging. 5, 366–375 (2025).

He, J. et al. Intestinal changes in permeability, tight junction and mucin synthesis in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 52, 113 (2023).

Pellegrini, C. et al. The intestinal barrier in disorders of the central nervous system. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 66–80 (2023).

Doney, E., Cadoret, A., Dion-Albert, L., Lebel, M. & Menard, C. Inflammation-driven brain and gut barrier dysfunction in stress and mood disorders. Eur. J. Neurosci. 55, 2851–2894 (2022).

Popoola-Akinola, O. O., Raji, T. J. & Olawoye, B. Lignocellulose, dietary fibre, inulin and their potential application in food. Heliyon 8, e10459 (2022).

El-Nashar, H. A. S., Taleb, M., El-Shazly, M., Zhao, C. & Farag, M. A. Polysaccharides (pectin, mucilage, and Fructan inulin) and their fermented products: A critical analysis of their biochemical, gut interactions, and biological functions as antidiabetic agents. Phytother Res. 38, 662–693 (2024).

Pascale, N., Gu, F., Larsen, N., Jespersen, L. & Respondek, F. The potential of pectins to modulate the human gut microbiota evaluated by in vitro fermentation: A systematic review. Nutrients 14, 3629 (2022).

Beukema, M., Faas, M. M. & de Vos, P. The effects of different dietary fiber pectin structures on the Gastrointestinal immune barrier: impact via gut microbiota and direct effects on immune cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 1364–1376 (2020).

Dang, G. et al. Pectin supplement alleviates gut injury potentially through improving gut microbiota community in piglets. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1069694 (2022).

Tian, B. et al. Gallic acid ameliorated chronic DSS-Induced colitis through gut microbiota Modulation, intestinal barrier Improvement, and inflammation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 69, e70024 (2025).

Tawfick, M. M., Xie, H., Zhao, C., Shao, P. & Farag, M. A. Inulin Fructans in diet: role in gut homeostasis, immunity, health outcomes and potential therapeutics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 208, 948–961 (2022).

van Trijp, M. P. H. et al. Fermentation kinetics of selected dietary fibers by human small intestinal microbiota depend on the type of fiber and subject. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 64, e2000455 (2020).

Le Bastard, Q. et al. The effects of inulin on gut microbial composition: a systematic review of evidence from human studies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39, 403–413 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Lactobacillus rhamnosus alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet through modulation of different gut microbiota-dependent pathways. Food Funct. 11, 6115–6127 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Effect of Lactobacillus casei on lipid metabolism and intestinal microflora in patients with alcoholic liver injury. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 75, 1227–1236 (2021).

Pontifex, M. G. et al. Differential influence of soluble dietary fibres on intestinal and hepatic carbohydrate response. Nutrients 13, 4278 (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Inulin fermentable fiber ameliorates type I diabetes via IL22 and Short-Chain fatty acids in experimental models. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 983–1000 (2021).

Deehan, E. C. et al. Precision Microbiome modulation with discrete dietary fiber structures directs Short-Chain fatty acid production. Cell. Host Microbe. 27, 389–404e6 (2020).

Laffin, M. et al. A high-sugar diet rapidly enhances susceptibility to colitis via depletion of luminal short-chain fatty acids in mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 12294 (2019).

Wood, A. H. R., Chappell, H. F. & Zulyniak, M. A. Dietary and supplemental long-chain omega-3 fatty acids as moderators of cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nutr. 61, 589–604 (2022).

Hartnett, K. B. et al. Potential neuroprotective effects of dietary Omega-3 fatty acids on stress in alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 13, 1096 (2023).

Liu, S., Gao, J., Zhu, M., Liu, K. & Zhang, H. L. Gut microbiota and dysbiosis in alzheimer’s disease: implications for pathogenesis and treatment. Mol. Neurobiol. 57, 5026–5043 (2020).

Serini, S. et al. EPA and DHA differentially affect in vitro inflammatory cytokine release by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from alzheimer’s patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 9, 913–923 (2012).

Yassine, H. N. et al. Association of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation with alzheimer disease stage in Apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers: A review. JAMA Neurol. 74, 339–347 (2017).

Ciccone, L. et al. Omega-3 PUFAs as a dietary supplement in senile systemic amyloidosis. Nutrients 15, 749 (2023).

Di Miceli, M., Bosch-Bouju, C. & Layé, S. PUFA and their derivatives in neurotransmission and synapses: a new hallmark of synaptopathies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1–16 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665120000129 (2020).

Kim, O. Y. & Song, J. Important roles of Linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid in regulating cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric issues in metabolic-related dementia. Life Sci. 337, 122356 (2024).

Bazan, N. G. Neuroprotectin D1-mediated anti-inflammatory and survival signaling in stroke, retinal degenerations, and alzheimer’s disease. J. Lipid Res. 50, S400–405 (2009). Suppl.

Fock, E. & Parnova, R. Mechanisms of Blood-Brain barrier protection by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain fatty acids. Cells 12, 657 (2023).

Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A. & Frozza, R. L. The role of Short-Chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-Brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 25 (2020).

Kaur, G., Cameron-Smith, D., Garg, M. & Sinclair, A. J. Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3): a review of its biological effects. Prog Lipid Res. 50, 28–34 (2011).

Roy, P., Tomassoni, D., Nittari, G., Traini, E. & Amenta, F. Effects of choline containing phospholipids on the neurovascular unit: A review. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 988759 (2022).

Maruoka, M. & Suzuki, J. Regulation of phospholipid dynamics in brain. Neurosci. Res. 167, 30–37 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 94 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This paper is in memory of the late Dr. Walter J. Lukiw, who actively participated in this study. We would like to thank Rasangi Perera for the mass spectrometry analysis and Ms. Liz McGehee for her assistance with editing and revising the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Joe W. and Dorothy Dorsett Brown Foundation 2020 Healthy Aging Initiative, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant award number R01AG038834, and the Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat (EENT) Foundation of New Orleans.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NGB, YZ, and WJL conceived the idea for the study. The experimental design was developed by YZ, WJL, and NGB. Experiments were conducted and analyzed by YZ and CMT. The manuscript was written by NGB and YZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions