Abstract

Skin disease diagnosis remains challenging in remote areas due to limited access to dermatology specialists and unreliable internet connectivity. Edge AI offers a potential solution by offloading the inference process from cloud servers to mobile devices. This research proposes a novel Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation (MTAKD) framework to optimize small model performance for mobile edge deployment. MTAKD uses dynamic teacher agreement as an indicator of knowledge reliability and weights multiple knowledge sources for each input. MTAKD integrates three novel algorithms, such as Agreement Weighted Knowledge Distillation for prediction knowledge, Attention Agreement Knowledge Distillation for spatial attention guidance, and Relational Agreement Knowledge Distillation for embedding relations. MTAKD achieves mean accuracies of 87.53% on the ISIC 2019 dataset and 44.75% on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset, outperforming the highest accuracy on benchmark frameworks by 0.75 and 1.1%. In addition, the student model demonstrates improved explainability, with insertion metric scores of 0.6796 AUC on ISIC 2019 and 0.1724 AUC on Fitzpatrick17k-C. Deployment on a mobile prototype demonstrates significant efficiency gains with 49.8 times smaller size and 352 times faster inference. These results support the proposed MTAKD as an effective and practical solution for edge AI skin disease diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dermatological care has become increasingly challenging because many skin diseases share similar visual features. Limited access to dermatology specialists in remote areas often results in less accurate diagnoses by general practitioners1. AI-powered teledermatology has emerged as a promising tool to assist general practitioners in improving diagnostic accuracy2. However, cloud-based teledermatology depends on a server connection to generate diagnostic results. This became a challenge in remote areas where internet access is often limited. Edge AI has become a promising solution by offloading the inference process directly to mobile devices3.

Teledermatology using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) approach can perform diagnosis based on skin disease images. However, CNN models often have large model sizes, making them challenging to deploy on mobile devices4. Recent research has focused on using smaller architectures for mobile deployment, but these models often show lower diagnostic performance. Model compression addresses this challenge by reducing the size of large models with minimal performance trade-off5.

The known model compression methods are pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation. Pruning reduces the model size by removing unnecessary parameters that have minimal impact on model performance6. Quantization compresses the model by reducing the precision of model weights7. Both approaches reduce the compressed model capacity and limit performance improvements over the uncompressed model. Knowledge distillation takes a different approach by training a smaller student model using the knowledge of a larger teacher model8. The student model not only can retain the accuracy of the teacher model but also potentially surpass it. This is possible because the student model learns from the ground truth labels and the soft labels provided by the teacher. These soft labels help the student model generalize better by learning the relationship between classes9.

Most existing research on knowledge distillation focuses on a single teacher framework to enhance the knowledge transfer10,11. However, this approach limits the diversity of knowledge that could be obtained from different teacher architectures. Although multi-teacher approaches have been explored, the strategies commonly rely on uniform averaging12 or static weighting based on individual teacher characteristics13. These approaches overlook the differences in output among teachers, which can result in conflicting or inconsistent guidance for the student model. The major limitation is the failure to consider agreement among teacher predictions, since it reflects knowledge reliability. This highlights a critical gap in current knowledge distillation research and shows the need for a more reliable multi-teacher framework.

This research aims to address the identified research gap by developing a knowledge distillation framework that weights the agreement among teacher models. The objective is to provide more consistent information that improves the quality of knowledge transferred to the student. The proposed framework will be validated using two skin disease datasets that include both dermoscopic and clinical images. The results were evaluated using a mobile application prototype to demonstrate the practicality of deployment on mobile devices.

This research contributes by developing a novel framework called Multi-Teacher Agreement Knowledge Distillation (MTAKD) to optimize knowledge transfer using agreement weighting across teacher predictions. The framework integrates three novel algorithms to extract agreement-based knowledge from teacher models. These algorithms include Agreement Weighted Knowledge Distillation (AWKD) to extract knowledge from softened logits at the output layer, Attention Agreement Knowledge Distillation (AAKD) to capture spatial focus from attention maps derived from feature representations, and Relational Agreement Knowledge Distillation (RAKD) to learn relational knowledge from the embedding representations. The contribution also includes the development of a mobile prototype to evaluate the student model performance on mobile devices. This research outcome will advance the deployment of efficient AI models for skin disease diagnosis in remote areas with limited connectivity.

Related work

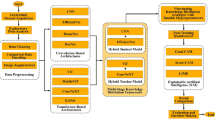

Recent research has explored knowledge distillation to compress large teacher models into smaller student models. Figure 1 presents a visual summary of recent knowledge distillation methods categorized by teacher type and knowledge source. The classical Hinton knowledge distillation framework proposed the use of soft targets from a single teacher to train a smaller student model8. Subsequent research has extended the original approach by allowing the student model to learn not only from the output predictions but also from other sources of knowledge. These include knowledge from intermediate representations14, deep feature representations15, relational information in vector embedding spaces16, and features from the semantic feature layer that capture richer semantic context17. Other approaches also use contrastive distillation with instance discrimination to align student and teacher embeddings18.

Recent research has also explored explainability approaches to enhance the learning process of the student model. This approach guides the smaller student model to focus on the most relevant features. The research using this approach includes using attention maps derived from teacher activations19,20, utilizing attention heatmaps generated through Grad-CAM21, using class attention transfer to guide the student by aligning the spatial attention of the student model with class-specific activation maps from the teacher22, and using classification loss to create attention maps that guide the student to focus on regions it struggles to learn23. The explainability approach not only can improve the model performance but also can enhance explainability guided by the teacher model.

While the single teacher approach is improving the student model performance, several studies are using the multiple teacher model to improve the knowledge quality. The approach used such as using the average of the output prediction from multiple teacher models12, weighting the teacher prediction based on the individual teacher characteristics13, assigning weights to each teacher based on the input sample24, extracting knowledge from a mixture of experts25, and reducing the gap between the model capacity using the assistant model26. These multi-teacher strategies offer richer guidance by providing diverse perspectives from different teacher models. However, most existing methods do not consider the consistency and agreement between teacher outputs. This can lead to noise in the form of conflicting predictions.

Recent research in medical image classification has demonstrated the effectiveness of knowledge distillation. It shows that knowledge distillation can maintain, or even improve, performance in classification tasks. The approaches explored include incorporating attention maps into the distillation process, which improved student model accuracy by 1.52% on the PAD-UFES-20 skin disease dataset27. The use of vision transformers as teacher models has also proven effective, with improved classification performance of 0.79% in leukocyte microscopy images28. A dual-student collaborative learning approach enhanced student model performance by 0.56% on the HAM10000 dataset11, while hybrid student models trained from CNN-based teachers facilitated better knowledge transfer between architectures, improving the student accuracy by 0.36%29. Using incremental learning with a proposed embedding distillation approach has also been shown to improve the accuracy of the student model30. More recently, research on skin disease proposed the Self-Supervised Diverse Knowledge Distillation (SSD-KD) framework10. That work demonstrated improved student performance in skin disease classification using the ISIC 2019 dataset and was successfully deployed on mobile platforms31. These research developments serve as a foundation for designing the proposed framework.

Methods

Multi-teacher agreement knowledge distillation

Recent research has shown that averaging the predictions from multiple teachers often results in higher student accuracy compared to using a single teacher12. However, in a multi-teacher approach, teacher predictions can vary significantly. Some teachers may produce highly confident predictions, which limits the transfer of soft inter-class relationships8,32. In such cases, the knowledge distillation loss degenerates into a form similar to cross-entropy. Although temperature scaling has been used to mitigate this issue in the single-teacher approach, the optimal temperature varies across teachers in a multi-teacher approach. As a result, highly confident outliers may dominate the aggregated prediction.

These limitations motivate the use of agreement-based weighting in the proposed Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation (MTAKD) framework, as shown in Fig. 2. MTAKD stabilizes teacher prediction aggregation to optimize the overall knowledge transfer process. Unlike the static weighted teacher approach, which applies fixed weights to teacher models, the proposed MTAKD assigns adaptive weights for each training sample. This approach ensures the teacher’s contributions dynamically reflect the agreement among teachers. The framework utilizes agreement from multiple teacher models with diverse architectures to provide richer and more informative guidance for the student model. MTAKD assigns dynamic weights to each teacher model for every training sample. Teachers with higher agreement with others are given larger weights, while those with lower agreement are assigned smaller weights.

In addition to learning from teacher predictions, the framework combines supervision from ground-truth labels into the training process. It extracts knowledge using three novel algorithms specialized for multi-teacher knowledge transfer. Agreement Weighted Knowledge Distillation (AWKD) learns from teacher predictions. Attention Agreement Knowledge Distillation (AAKD) aligns spatial focus. Relational Agreement Knowledge Distillation (RAKD) transfers relational information. These integrated algorithms improve the student learning process and help build a more accurate and efficient model.

Agreement weighted knowledge distillation (AWKD)

Teacher models in a multi-teacher approach often differ in predictive uncertainty, confidence prediction, and inductive biases from their architectures. As a result, uniform averaging is not optimal, as it assumes equal reliability across teachers. Previous research has shown that when individual estimators have different variances, inverse-variance weighting yields lower estimation error than uniform averaging33. Building on this principle, this research proposes Agreement Weighted Knowledge Distillation (AWKD) that assigns weights based on the degree of agreement among teachers, rather than treating all teachers as equally reliable. The theoretical basis of the algorithm also draws from robust statistics, where bounded influence functions limit the effect of outliers34. The formulation of agreement scores is adopted from the z-score method for outlier detection to identify unusual deviations relative to the mean and standard deviation35. Although the z-score standard deviation is unbounded, the exponential inverse-variance weighting formula ensures that large deviations receive exponentially small weight. This calculation results in the weights summing to one and ensures that the contribution of any single teacher remains bounded. By prioritizing agreement among teachers, AWKD reduces the impact of noisy and overconfident predictions. This provides a more reliable knowledge than a uniform average.

AWKD using the agreement score among teacher models. This score reflects the agreement of teacher prediction outputs for the ground-truth class. The agreement score is used to weight each teacher’s contribution. By prioritizing consistent information across teachers, AWKD captures better inter-class relationships and reduces the influence of teachers with divergent outputs. Importantly, this approach is distinct from confidence-based weighting, where assigning a dominant weight to an overconfident teacher prediction can reduce the informative soft inter-class relationships that are crucial for knowledge distillation. Figure 3 presents the visualization of the multi-teacher agreement score. Teachers with high agreement with others are assigned the greater agreement score, while those with lower agreement receive a smaller score.

The algorithm begins by extracting logits on the output layer to calculate softened softmax probabilities. The centroid among teacher probabilities is calculated using an adapted centroid formula. This value is derived from the softened probabilities corresponding to the ground-truth label. The ground-truth label probability is chosen as the most direct indicator of whether the teachers have agreement on the correct class. Importantly, the weights are then applied to the full teacher distribution, which ensures the student still benefits from softened inter-class relationships that are essential for knowledge distillation.

The algorithm then continues by calculating the variation among teacher models. This variation quantifies the deviation of the probability value provided by each teacher from the centroid. The variation formula is adapted using a standard deviation calculation. Equation (1) presents the centroid computation among teacher models, while Eq. (2) presents the variation computation based on the deviation of probabilities across teacher models.

Where \(\:{\mu\:}_{i}\) denotes the centroid among teacher models, \(\:T\) is the number of teachers and \(\:{P}_{y}^{t}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) represents the softened probability for the ground-truth label from the teacher model \(\:t\), and the variation among teacher models is denoted by \(\:{\sigma\:}_{i}\). The algorithm then calculates the agreement score among teacher models using the centroid and the variation. The agreement score is obtained by measuring the absolute difference between the prediction probability of the teacher model and the centroid value. The value was then normalized using the teacher prediction variation. A negative exponential function is used to convert the result into an agreement score. This makes the teachers with closer predictions to the agreement receive a higher score. The score is then normalized to produce the multi-teacher agreement weights. Normalization is performed by dividing each agreement score by the total agreement scores from all teacher models. Multi-teacher agreement weight is used to weight probabilities from all teacher models. This weighted probability reflects the contribution of each teacher based on the level of agreement. Equation (3) presents the agreement score calculation for each teacher model, Eq. (4) presents the computation of the multi-teacher agreement weight, and Eq. (5) presents the computation of softened probabilities using multi-teacher agreement weighting.

The agreement score \(\:{A}_{i}^{t}\) is obtained for each teacher model \(\:t\) to compute the multi-teacher agreement weight \(\:{w}_{i}^{t}\). The AWKD loss is calculated using the Kullback–Leibler divergence between output from the student model and the weighted teacher probabilities \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{p}}_{c}\left({x}_{i},\:Temp\right)\) softened by temperature \(\:Temp\). Equation (6) presents the computation of the AWKD loss.

AWKD loss \(\:{L}_{AWKD}\:\)is calculated over a batch \(\:B\) by comparing class-wise probabilities \(\:C\) from the softened probabilities output of the student model \(\:{p}_{c}^{s}\left({x}_{i},Temp\right)\) and the weighted probability outputs of the teacher models. The loss guides the student model to mimic the teacher’s agreement probability distribution. It helps the student model learn more consistent information about the relationships between classes. Algorithm 1 shows the pseudocode for calculating AWKD loss.

Where X denotes the input batch, Y is the ground-truth label, T[] is the array of teacher models, S is the student model, and Temp is the temperature parameter. SoftenedSoftmax is the function that calculates softmax with temperature. Centroid refers to the function that calculates the centroid among teacher models as defined in Eq. (1). Variance is the function that calculates the deviation of probabilities across teacher models as defined in Eq. (2). AgreeScore is the function that calculates the teacher agreement score defined in Eq. (3). AgreeWeight is the function that calculates the multi-teacher agreement weight as shown in Eq. (4). WeightedProb is the function that calculates the weighted teacher probabilities using the formula from Eq. (5). KLLoss is the function that calculates the AWKD loss using the Kullback–Leibler divergence as defined in Eq. (6).

Attention agreement knowledge distillation (AAKD)

The Attention Agreement Knowledge Distillation (AAKD) algorithm captures spatial information by extracting attention maps from feature maps. By utilizing a multi-teacher agreement approach, this algorithm improves attention transfer over the single-teacher approach20. The algorithm’s theoretical justification uses the same foundation as AWKD to weight the attention map with the multi-teacher agreement weight. Figure 4 presents the visualization of the multi-teacher attention map weighting process. The weighted teacher attention map resulting from this process is a more representative attention map for the output results.

The algorithm begins by extracting the feature map from the convolution layer and aggregating values across channels to form the attention map. The attention map is then normalized to adjust for different scales across models. Equation (7) presents the attention map calculation from the feature map, while Eq. (8) presents the normalization of the attention map20.

\(\:M\left({x}_{i}\right)\:\)denotes the attention map obtained from feature maps \(\:{f}_{d}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) by aggregating values across channels \(\:D\). The normalized attention map \(\:{M}^{norm}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is calculated by applying Euclidean normalization. The normalization scales the attention values by the square root of the sum of squared elements across spatial dimensions \(\:H\) and \(\:W\). The attention map normalization is applied to the student model and all teacher models. The algorithm then continues by calculating the weighted teacher attention maps by aggregating the normalized attention maps scaled by the multi-teacher agreement weight calculated in Eq. (4). Equation (9) presents the computation of the weighted teacher attention maps.

The weighted teacher attention map \(\:{M}_{t}^{weighted}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is compared with the student attention map using cosine similarity to compute the AAKD loss. Cosine similarity is used because the student model is encouraged to mimic the attention distribution pattern based on directional similarity rather than exact value matching. This approach is suitable for medical imaging because skin lesions often exhibit morphological diversity. Such variation makes exact value matching hard, given the architectural differences between the smaller student model and the larger combined teacher models. Forcing the student to follow the absolute value of the teacher’s attention map would overburden its limited capacity and lead to unstable training. It could also introduce gradient competition with other losses. In contrast, cosine similarity helps the student to align with the directional similarity of clinically meaningful regions from the teacher’s model with less burden. Equation (10) presents the computation of the AAKD loss.

AAKD loss \(\:{L}_{AAKD}\:\)is calculated over a batch \(\:B\) by comparing the values at each spatial location \(\:H\) and \(\:W\) between the student attention map and the weighted teacher attention map \(\:{M}_{t}^{weighted}\left({x}_{i}\right)\). The loss guides the student model to mimic the focused region in the teacher’s agreement attention map. This approach helps the student with fewer parameters focus on the meaningful regions in the feature map. Algorithm 2 shows the pseudocode for calculating AAKD loss. Where X denotes the input batch, Y is the ground-truth label, T[] is the array of teacher models, S is the student model, and W is the multi-teacher agreement weight calculated using Eq. (4). FeatureExtractor refers to the function used to extract the feature map, while AttentionMap reduces the feature map channels as defined in Eq. (7). NormalizedAttentionMap is the function that normalizes the attention map using Eq. (8). WeightedTeacherAtt computes the weighted teacher attention maps as defined in Eq. (9). CosineSimilarityLoss is a function to calculate the AAKD loss using cosine similarity as defined in Eq. (10).

Relational agreement knowledge distillation (RAKD)

The Relational Agreement Knowledge Distillation (RAKD) algorithm is designed to learn the relational patterns of the embeddings at the pooling layer. These patterns contain distance and angular relationships. The concept was introduced in Relational Knowledge Distillation (RKD)16 with a single-teacher model. RAKD improves this approach by using multiple teacher models with agreement among teachers as an indicator of knowledge reliability. The algorithm is theoretically justified by employing the same foundation as AWKD, in which multi-teacher distances and angular relations are weighted using the multi-teacher agreement weight. Figure 5 illustrates the pairwise distance and angular relations from multi-teacher embeddings that are weighted to guide the student.

The algorithm begins by extracting the embedding for each input and comparing it with others to calculate pairwise distances. The distances are then normalized due to the different scale values of the model architectures. Equation (11) presents the pairwise distance calculation between two embeddings, while Eq. (12) presents the pairwise distance normalization24.

Where \(\:d\left({e}_{i},{e}_{j}\right)\) denotes the vector distance between the embedding \(\:{e}_{i}\) and \(\:{e}_{j}\). The normalized distance \(\:{\psi\:}_{d}\left({e}_{i},\:{e}_{j}\right)\) is calculated by dividing the distance by the average of all embedding distances in the training batch \(\:B\). The angular relationship is measured by calculating angles between three embeddings. These relationships map the positions of the embeddings within the feature space relative to each other. Equation (13) presents the angular relationship calculation between three embeddings16.

Angle \(\:{\psi\:}_{a}\left({e}_{i},\:{e}_{j},\:{e}_{k}\right)\:\)represents the cosine of the angle between the two vectors \(\:{e}_{i}-\:{e}_{j}\) and \(\:{e}_{k}-\:{e}_{j}\) from three embeddings. The distance and angular relationships are computed for all input combinations in the student model and all teacher models. The multi-teacher agreement weight from Eq. (4) is applied as the weighting factor for each teacher model. The loss is measured based on the differences between the student model and the weighted agreement of the teacher models using Huber loss. Equation (14) presents the computation of RAKD distance loss, while Eq. (15) presents the computation of RAKD angular loss. Both losses are combined as the RAKD loss in Eq. (16).

The RAKD loss is computed by balancing the distance loss \(\:{L}_{RAKD}^{d}\) and angular loss \(\:{L}_{RAKD}^{a}\) using the hyperparameter coefficients \(\:{\lambda\:}_{RAKD}^{d}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{RAKD}^{a}\). Both distance and angular losses are calculated by averaging the Huber loss \(\:H\) across all combinations over the batch \(\:B\), weighted with the multi-teacher agreement weight \(\:{w}_{i}^{t}\). The weighted relationships among the teacher models help guide the student model to learn the embedding relations for each input. Algorithm 3 shows the pseudocode for calculating RAKD loss. Where X denotes the input batch, Y is the ground-truth label, T[] is the array of teacher models, S is the student model, and W is the multi-teacher agreement weight calculated using Eq. (4). EmbeddingExtractor refers to the function used to extract the embedding at the pooling layer. DistanceHuberLoss is the function that computes the Huber loss based on the distance between the student and weighted teacher embeddings as defined in Eqs. (11), (12), and (14). AngularHuberLoss calculates the Huber loss from the angular difference between student and teacher embeddings as defined in Eqs. (13) and (15). WeightedLoss combines the distance and angular losses to compute the final RAKD loss as defined in Eq. (16).

Loss integration

To prevent the risk of misleading knowledge when multiple teacher prediction aligns on the same incorrect class prediction, the loss integrates with cross-entropy loss to guide the student toward ground-truth consistency. Multiple loss terms are combined using hyperparameter coefficients to balance their contributions. These coefficients also help reduce conflicts between losses, minimizing gradient competition, and avoiding unstable convergence during training. Equation (17) presents the computation of MTAKD loss.

Where \(\:{\lambda\:}_{AWKD}\), \(\:{\lambda\:}_{AAKD}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{RAKD}\) denote hyperparameter to balance the AWKD, AAKD, and RAKD loss, respectively. This formulation enables the training process to be adjusted based on the reliability of each knowledge source. Such an adjustment is beneficial as it provides flexibility in different scenarios.

Experimental design and dataset

The proposed framework was evaluated using an ablation experiment to assess the contribution of each algorithm. The experiment started with training the student model using the proposed framework. The student model was then evaluated on an edge AI teledermatology application prototype. The focus of this evaluation is to highlight the improvements achieved by the proposed framework and its practical applicability. Figure 6 shows the flowchart of the evaluation process.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MTAKD framework, comparisons were made with existing knowledge distillation frameworks. Hinton et al. knowledge distillation (Hinton-KD) framework is included as the classical baseline that established knowledge distillation8. Attention transfer knowledge distillation (AT-KD) is selected because it represents attention-based knowledge distillation to transfer feature knowledge and compare the benefit of transferring spatial attention20. Relational Knowledge Distillation (RKD) is chosen as this framework focuses on transferring relational knowledge between training samples16. Both AT-KD and RKD are trained with additional dark knowledge, as it represents the highest performing result in the research. In addition, the Self-Supervised Diverse Knowledge Distillation (SSD-KD) framework is included as a recent development in skin disease classification that combines self-supervised learning with diverse knowledge distillation losses10. The approach using the uniform average on multi-teacher models (Averaging-KD) is considered because it is the most common strategy for multi-teacher settings and provides a direct reference for evaluating the contribution of the proposed MTAKD framework12. Finally, the Confidence-Aware Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation (CA-MKD) is included because it introduces confidence-based weighting based on the teacher confidence prediction to the ground-truth label, serving as an important comparator for the multi-teacher weighting approach13. Together, these frameworks cover the major categories of knowledge distillation to provide a strong and balanced benchmark. All frameworks were implemented under the same experimental environment, model design, loss coefficients, temperature, dataset split, and data augmentation to ensure fair and consistent comparison.

While Vision Transformers have shown promising results in classification tasks, they still face challenges in computational complexity and model size36. These limitations make them unsuitable for edge computing, where low-resource and lightweight models are needed. For this reason, transformer-based knowledge distillation frameworks were not included in the comparison. Moreover, including transformer-based teacher models would introduce bias into the comparison, as their substantially different architectures and sizes could transfer knowledge to the student model in a fundamentally different way.

Student model training began with the data collection to gather data from the ISIC 2019 and Fitzpatrick17k-C datasets. The ISIC 2019 dataset consists of dermoscopic skin disease images, which require a special optical device for image capture. In contrast, the Fitzpatrick17k-C contains clinical images captured using a standard camera. This dataset presents a more challenging scenario, as the images are not focused solely on the lesion but also capture a broader skin region. The dataset also presents an additional challenge with various lighting conditions and background noise. The use of both datasets in this research is to validate the efficiency of the MTAKD framework in handling both dermoscopic and clinical images. Figure 7 shows the sample data from the ISIC 2019 dataset and the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset.

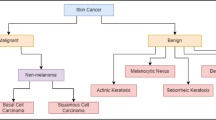

The ISIC 2019 is a multi-class dataset that categorizes skin diseases into eight classes from a total of 25,331 images37,38,39. Each image focuses on the skin lesion with the surrounding skin as the background. The challenge for this dataset is high visual similarity between the lesions, and it often still contains artifacts such as body hairs. Compared to the more recent ISIC dataset, ISIC 2019 presents a larger number of skin disease labels. This setting is advantageous for highlighting the efficiency of the proposed framework. The ISIC 2019 is imbalanced with significant variation in class distribution. Melanocytic nevi have the highest proportion at 50.83%, while dermatofibroma has the lowest at only 0.94%.

Recent research has developed various models using the ISIC 2019 dataset. Research comparing multiple pretrained models has shown an accuracy of 74.91%42. Another approach using a custom architecture achieved 83% accuracy43. The SSD-KD knowledge distillation framework achieved 84.6% accuracy10, and an enhanced SSD-KD version utilizing a large-parameter teacher model achieved the highest accuracy of 86.73%31.

The clinical images from the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset are classified into 114 classes from a total of 11,394 images40,41. The Fitzpatrick17k-C is a cleaned version of the original Fitzpatrick17k dataset. The challenge of this dataset is that the images are not focused solely on the skin lesions but often include broader body regions. The other challenge is that the image quality, image sizes, and lighting conditions vary significantly. In addition, the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset contains six types of Fitzpatrick scale to classify skin phototypes based on skin reactivity against ultraviolet. This means the dataset itself contains a wide range of skin colors from very fair skin to darker skin color. This dataset is also imbalanced and further complicated by a large number of classes with significant variation in class distribution, sometimes containing as few as 20 images. Psoriasis has the highest proportion at 4.7%, while disseminated actinic porokeratosis has the lowest at only 0.18%. These factors present challenges for classification and typically result in lower accuracy compared to the ISIC 2019 dataset.

The model for the Fitzpatrick17k dataset was initially created using VGG-16, which achieved 20.2% accuracy41. Fitzpatrick17k-C achieved a higher accuracy of 22.25% using the same architecture40. The highest accuracy was achieved by research using the large-parameter RegNetY32GF architecture, which reached 43.89% accuracy31. Due to the difficulty of this dataset, other research has focused on a smaller number of classes. For example, creating an AI model using a custom architecture for classifying 16 classes focused on specific country standardization achieved 51% accuracy44 and other research focusing on classifying six Fitzpatrick skin scales achieved an accuracy of 66.9%45. These low accuracies from recent research demonstrate the difficulty of the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset.

To further investigate the observed performance gap between ISIC 2019 and Fitzpatrick17k-C, this research utilizes the Difficulty Measurement (DIME) as a supporting tool to quantify the classification difficulty in the datasets46. Figure 8 presents the DIME scores across seven datasets, such as ISIC 2020, HAM 10,000, DermaMNIST, ISIC 2018, ISIC 2019, Fitzpatrick17k, and Fitzpatrick17k-C. The lowest DIME score is observed for the ISIC 2020 dataset, which includes two classes of benign and malignant, indicating low difficulty. The ISIC 2019 shows a DIME score of 0.253, the highest among dermoscopic datasets. In contrast, Fitzpatrick17k-C resulted in the highest overall DIME score at 0.752, followed by Fitzpatrick17k at 0.708. These findings suggest that clinical image datasets such as Fitzpatrick17k-C pose greater classification challenges due to some factors, such as diverse skin tones, variable lighting conditions, and a severe class imbalance.

Data preprocessing and training data augmentation

The experiment uses a 224 × 224 image input for all student and teacher models. During the data preprocessing process, all images from both datasets are resized into the required input size with three channels. The images were then separated into a 70% training set, a 15% validation set, and a 15% test set using stratified sampling. The stratified sampling is critical to preserve the same class distribution in each set, particularly in Fitzpatrick17k-C, where class imbalance is severe. The training and validation sets are used during the model training process, while the test set is used to evaluate model performance on unseen data. The resized images are stored in the folders and are loaded dynamically during the training process. Each folder name is mapped to a class label and used as a reference during model training.

Data augmentation is used to address the imbalance in both the ISIC 2019 and the Fitzpatrick17k-C datasets. It also helps to improve generalization for better model performance. The augmentation process is performed in real time during the training process. This applied only to the training set, while validation and test sets retain the original images. This process is run by multiple parallel calls to optimize the resources.

The augmentation process includes random rotation within a range of −30 to 30 degrees, random horizontal flipping, and zooming with a spatial scaling factor ranging from − 0.3 to 0.3. Images are also processed with random translation with a maximum shift of 30% for both vertical and horizontal axes. Brightness adjustment is applied to modify the pixel intensity in the range − 0.4 to 0.4. The same training set with identical augmentation, as well as the same validation and test sets, was also applied to the teacher model. This approach is intended to prevent model bias and data leakage during the knowledge transfer.

Model design and training

The student model uses the MobileNetV2 architecture as a lightweight model. This model is well-suited for mobile devices with low memory and computation capacity. Its efficiency is achieved through inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks that minimize resource usage47. The teacher models consist of six architectures, such as RegNetY32GF, DenseNet201, Xception, InceptionV3, NASNetMobile, and EfficientNetV2B0. RegNetY32GF is the largest variant in the RegNet family, extending the residual design with systematic scaling. DenseNet201 is the large model in the DenseNet family, using dense connectivity to improve feature reuse. InceptionV3 introduces inception modules to capture multi-scale features. Xception adapts the inception design by replacing standard convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions. NASNetMobile represents a search-based architecture discovered through neural architecture search. Finally, EfficientNetV2B0 applies compound scaling across depth, width, and resolution to improve efficiency.

These teacher models vary from very large to smaller parameter architectures to offer diverse knowledge perspectives during the student training process. While most multi-teacher knowledge distillation research uses fewer than six teachers and relies mainly on mid-sized to compact models10,12, this research goes beyond prior research by adding more teacher models with very large to compact models. This selection combines residual, dense, inception, search-based, and compound-scaled architecture designs to ensure the proposed MTAKD is validated under diverse architectures rather than a single architecture. All of the models use a pre-trained model on the ImageNet dataset and use it as a feature extractor by excluding the original classification layers. The feature extraction layers of all models are set to be trainable during the training process.

The classification head is connected to the preceding feature extraction layer using a global average pooling layer, followed by a fully connected layer with 512 units and ReLU activation. This layer is integrated with both kernel and bias regularization, using a regularization factor of 0.01. This approach reduces overfitting and improves the generalization of the model. Finally, the model is connected to an output layer configured according to the number of classes in each dataset. This experiment applies the same classification head to both student and teacher models to ensure a consistent basis for evaluating performance improvements.

The training process for the teacher models was conducted for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32. Parameters were updated using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001. To enhance convergence stability, the SGD optimizer was used alongside Nesterov Accelerated Gradient (NAG) momentum set to 0.95. Cross-entropy loss was used as the classification loss function, with label smoothing of 0.1 applied to reduce overconfident predictions from the teacher models. The learning rate was reduced by a factor of 0.1 when the validation loss did not improve for two consecutive epochs. Early stopping was applied if the validation loss failed to improve for three consecutive epochs.

The student model was trained for 150 epochs with a batch size of 32. The SGD optimizer was used with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and NAG momentum of 0.97. The learning rate was reduced by a callback with a reduction factor of 0.3 and a minimum learning rate of 0.0001, triggered when the validation loss did not improve for 15 consecutive epochs. The AWKD loss coefficient was set to 0.6. The model also learned from ground-truth labels with a complementary coefficient of 0.4. The AAKD loss coefficient was assigned a small coefficient of 0.01 to maintain balance with other loss components and prevent it from dominating the training dynamics due to its position in the lower layers of the network. The RAKD loss coefficient was set to 0.3 to balance its contribution to the other losses.

Evaluation metrics and experimental environment

Model classification performance was evaluated using four standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of model performance. Accuracy measures the percentage of overall correct predictions made when classifying skin diseases. Precision measures the percentage of correct predictions among all images that the model classified to a specific class. Precision shows the ability to reduce false positives, which is important to minimize misclassification between similar skin disease images. Recall measures the percentage of correctly predicted images among all images that belong to a specific class. Recall presents the ability to reduce false negatives that can fail to recognize certain types of skin disease. F1-score measures the balance between precision and recall. This reflects the ability to maintain consistent accuracy across all classes.

Each model was trained five times (\(\:n\) = 5) to calculate the mean of the performance. The performance variance was calculated using the standard deviation. This ensures the results are stable and accurate. Student’s t-test was used to compare the results with a significance level of \(\:p\) < 0.05 as the threshold to validate whether the improvement is statistically significant. This statistical analysis supports the empirical reliability of the proposed framework.

The experiment also evaluates the Explainable AI (XAI) aspect from the attention map trained with the proposed framework. The metrics used are insertion metrics and deletion metrics48. These metrics are an unsupervised evaluation method used in Explainable AI to measure the impact of a model prediction when important regions in a skin disease image are either deleted or inserted. The values are computed based on the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of model prediction scores during the progressive insertion or deletion of regions ranked by their saliency scores. An insertion score close to one indicates a high-quality attention map, where the highlighted skin regions have strong positive contributions to the model prediction. In contrast, a deletion score close to zero indicates that removing important skin regions significantly degrades the prediction. This is a sign that a high-quality attention map has successfully identified highly relevant areas.

Edge computing was evaluated using a mobile application prototype with inference time and model size metrics. Inference time was calculated in milliseconds, measuring the time required for the inference process. The model size was calculated in kilobytes, measuring the memory space needed to load the model for inference. The inference process running on mobile devices was measured over 100 iterations to produce the mean and standard deviation results. These metrics demonstrated the practicality of the proposed framework for deployment on mobile devices.

The model training for both the teacher and student models was conducted using TensorFlow with Python and converted to TFLite as mobile models. The training was performed on a Windows workstation with an AMD Ryzen 9 9950 × 3D processor, 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 5090 GPU. The mobile device used is a smartphone running Android based on the Exynos 7884B, with 2 GB of memory and a Mali-G71 GPU. According to recent AI benchmark research from 132 smartphones, the Exynos 7884 ranks 122nd49. Another research evaluating memory capacity across 30 devices placed the 2 GB configuration at 25th50. These benchmarks indicate that the smartphone used for this experiment is a device with limited hardware resources and reflects usage conditions commonly found in remote areas.

Results

Teacher models and baseline student model

The experiment used a student model and various teacher models pretrained on the ImageNet dataset. MobileNetV2 is used as a student model due to its small size. It contains approximately 2.9 million parameters to cope with the computational constraints of edge deployment. Meanwhile, several pre-trained models ranging from large to small models are designed as the teacher model. The six teacher models include RegNetY32GF, DenseNet201, Xception, InceptionV3, NASNetMobile, and EfficientNetV2B0. To benchmark the proposed framework, the highest accuracy among the teacher models setting is used as the teacher model in the single-teacher benchmark framework.

Table 1 presents the performance of each pre-trained model on the classification task using the ISIC 2019 dataset. MobileNetV2 is included in the table as a baseline student model for comparison and was not used as a teacher model in the distillation process. The results show RegNetY32GF achieved the highest mean accuracy of 86.48% due to its large number of parameters. The model also demonstrated consistent performance across precision, recall, and F1-score. DenseNet201 provided a balanced trade-off between model size and performance. This model achieved the second-highest mean accuracy of 85.37% with a parameter size approximately 7.4 times smaller than RegNetY32GF. MobileNetV2 served as the baseline student model and had the lowest number of parameters. This model was trained without knowledge distillation and recorded the lowest mean accuracy of 80.17%. This model had a mean performance gap of 6.31% compared to RegNetY32GF.

RegNetY32GF demonstrates superior performance compared to other pre-trained models on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset. Table 2 presents the classification performance on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset. The model also recorded the highest precision at 47.52%, recall at 45.86%, and F1-score at 45.31%. The second-highest accuracy model is DenseNet201, which achieved an accuracy of 42.33%. This model provides a balanced trade-off for both datasets. MobileNetV2 achieved an accuracy of 35.07%. This baseline student model has a 10.79% accuracy gap compared to the highest accuracy teacher model.

The model performance shows consistently high performance of RegNetY32GF across both datasets at the cost of a significantly larger number of parameters. DenseNet201 demonstrates an optimal trade-off between performance and number of parameters. Meanwhile, the smallest pre-trained model, MobileNetV2, shows limited ability to achieve good classification performance compared to others. This evidence highlights the potential of KD to enhance the performance of smaller pre-trained models.

Performance of the proposed Multi-Teacher agreement knowledge distillation framework

The proposed Multi-Teacher Agreement Knowledge Distillation (MTAKD) framework was evaluated to demonstrate its effectiveness in improving the performance of the baseline student model. The evaluation was conducted on both the ISIC 2019 and Fitzpatrick17k-C datasets. The results were compared with several knowledge distillation frameworks, including Hinton-KD, AT-KD, RKD, SSD-KD, Averaging-KD, and CA-MKD. These frameworks represent classical, attention-based, relational, multi-teacher, self-supervised, and confidence-weighted approaches. The selection of these frameworks provides a comprehensive benchmark for assessing the proposed framework.

Table 3 presents a detailed performance comparison across multiple frameworks on the ISIC 2019 dataset. The proposed MTAKD framework achieved the best results across all metrics, reaching an accuracy of 87.53%. This represents an accuracy improvement of 1.04% over Hinton-KD as the classical knowledge distillation framework. The AT-KD framework method resulted in a lower accuracy than Hinton-KD. This decline may be due to the attention loss formulation that uses the squared L2 distance between the normalized attention maps of teacher and student. Enforcing the student to follow the absolute value of the high-capacity teacher attention map would overburden its limited capacity. In contrast, the MTAKD framework uses cosine similarity in its AAKD loss, allowing the student to align with the attention direction of the teacher’s attention without matching its absolute value. This approach reduces the burden on the limited-capacity student model.

MTAKD also showed a gain of 1.02% over the RKD and 0.78% over SSD-KD. MTAKD improves 0.76% over the Averaging-KD approach, which shows the proposed agreement-weighting can reduce the influence of teachers with divergent outputs to achieve better inter-class relationships. Lastly, MTAKD improved accuracy by 0.75% over CA-MKD, as the highest performing benchmark framework. These gains are statistically significant, indicated by \(\:p\)-values below 0.05 with \(\:n\) = 5.

Performance comparison of knowledge distillation frameworks on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset is shown in Table 4. The results in this dataset show a consistent trend with the ISIC 2019 results. The proposed MTAKD framework achieved the highest accuracy of 44.75%, and this was reflected across all metrics. Compared to Hinton-KD, MTAKD achieved an improvement of 3.61%, while also outperforming RKD by 3.55% and SSD-KD by 3.44%. The multi-teacher frameworks of Averaging-KD and CA-MKD performed better than the single-teacher approaches. Although CA-MKD achieved higher accuracy than Averaging-KD, the framework has lower precision. The MTAKD framework achieved a 1.1% improvement over CA-MKD, as the highest performing benchmark framework. The improvement achieved by MTAKD in Fitzpatrick17k-C was also statistically significant, as indicated by \(\:p\)-values below 0.05 with \(\:n=5\). This result confirms that MTAKD consistently outperforms existing approaches in both accuracy and other evaluation metrics on both skin disease datasets.

To further validate the role of each MTAKD component, an ablation study was conducted by isolating AAKD, RAKD, and AWKD. The ablation also evaluates their incremental combinations. In the ablation, each component was added with cross-entropy as classification task guidance to train the model. The ablation result in the ISIC 2019 dataset is shown in Table 5. Compared to the cross-entropy baseline, AAKD improves accuracy by 3.83%, RAKD by 5.55%, and AWKD achieves the highest individual component improvement of 6.96%. The AWKD provides a stronger and more direct impact on the accuracy, as it focuses on transferring the inter-class knowledge to the output layer. In contrast, AAKD and RAKD act as complementary sources of knowledge on the feature and embedding level. The result of incremental combinations confirms this complementary effect. Adding AAKD to AWKD increased accuracy by 0.14%, while adding RAKD to AWKD increased accuracy by 0.18%. The final integration of AWKD, AAKD, and RAKD shows the highest accuracy and other metrics by capturing knowledge at output, feature, and embedding levels.

Table 6 presents the ablation results of the MTAKD component on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset. Compared with the cross-entropy baseline, AAKD improves accuracy by 2.99%, RAKD by 3.52%, and AWKD achieves the highest individual component improvement of 9.22%. These results follow a similar trend to those observed on ISIC 2019, with AWKD as the main contributor to knowledge transfer. Adding AAKD to AWKD increased accuracy by 0.20%, while adding RAKD to AWKD increased accuracy by 0.28%. The full integration of AWKD, AAKD, and RAKD also shows the highest overall accuracy. The larger improvement observed in Fitzpatrick17k-C is partly due to its lower cross-entropy baseline accuracy, which provides greater room for improvement. In addition, Fitzpatrick17k-C includes 114 classes compared to only 8 classes in ISIC 2019. This greater class diversity enables the multi-teacher agreement to capture richer inter-class relationships for more effective knowledge transfer.

Based on the comparison with benchmark frameworks, the proposed MTAKD framework consistently outperforms existing approaches across both datasets. The ablation results further confirm that each component provides improvements. AWKD provides the largest contribution, while AAKD and RAKD give complementary knowledge enhancements. By integrating agreement knowledge from six diverse teacher models, the framework improves the student model by providing more consistent and informative knowledge. The consistent results across dermoscopic and clinical datasets demonstrate that the proposed framework is well-suited for edge AI in skin disease diagnosis.

MTAKD evaluation from the explainable AI perspective

The proposed MTAKD was further evaluated in the Explainable AI (XAI) aspect. This assesses how well the student model identifies the important region of the input image. The experiment focuses on utilizing attention maps obtained from the forward pass during model inference. These attention maps highlight spatial areas that contribute most to the output prediction. The experiment uses insertion and deletion metrics as an unsupervised XAI assessment48. These metrics are calculated from the Area Under the Curve (AUC) when inserting and deleting regions in 100-step order by the most salient pixel. The higher insertion metric and the lower deletion metric indicate better model explainability. Figure 9 shows the visual comparison of attention maps generated by Averaging-KD and the proposed MTAKD. Based on the visualization, the attention map generated by the MTAKD framework shows a more focused region compared to the Averaging-KD attention map. This indicates that MTAKD helps the student model highlight relevant features to improve interpretability.

Table 7 shows the detailed explainability performance of various knowledge distillation frameworks on the ISIC 2019 dataset. MTAKD achieved the highest insertion AUC of 0.6796 and the lowest deletion AUC of 0.4090. These correspond to improvements of 9.77% in insertion and 11.85% in deletion compared with the Averaging-KD framework, which recorded the second-best performance. These results validate the effectiveness of the MTAKD framework in guiding the student model to focus on the most relevant regions through teacher agreement.

Explainability performance comparison of knowledge distillation frameworks on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset is shown in Table 8. Compared with ISIC 2019, all frameworks in Fitzpatrick17k-C exhibit lower explainability performance due to the higher complexity of clinical images and the lower accuracy achieved on this dataset. However, the results also follow the same relative improvement trend as the ISIC 2019. The proposed MTAKD framework achieved the highest insertion AUC of 0.1724 and the lowest deletion AUC of 0.0582. These represent an improvement of 28.75% in insertion and 27.61% in deletion compared with the Averaging-KD framework, which achieved the second-best performance.

The proposed MTAKD framework demonstrated improved explainability performance on both datasets compared to the other frameworks. Statistical t-tests with \(\:n=5\) confirm that the improvements are statistically significant, showing \(\:p\)-values below 0.05 in all comparisons. The framework not only improves model accuracy performance but also enhances the XAI aspect. The agreement of teacher knowledge in feature maps helps guide the student model feature map through Attention Agreement Knowledge Distillation (AAKD) to provide better explainability. These results reinforce the practicality of the proposed framework, as the attention map can be generated during forward pass inference on mobile devices without requiring heavy calculation.

Edge AI prototype deployment

To evaluate the practicality of real-world deployment of the proposed MTAKD, the student model was deployed on mobile devices using an edge AI application prototype. This evaluation assessed inference time and memory required for running skin disease inference on mobile devices. The student model was converted into the TFLite mobile model. The TFLite mobile model reduced the size by removing any metadata that was not required for mobile inference. To demonstrate the usability of attention maps on mobile devices, the prototype also overlays the input image with the attention map output. This enhances both the practicality and explainability of the proposed framework.

Figure 10 shows screen captures from the mobile application prototype used in this evaluation. The prototype demonstrates inference running directly on the mobile device using the student model of the MTAKD framework. It infers both images captured using a dermatoscope and those taken with a phone camera. The output displays a red attention map overlay on the original input image. This red overlay highlights important regions relevant to the diagnosis. The diagnosis results present the top three predicted skin diseases along with their confidence percentages.

The prototype was then used to evaluate model size and inference time. Table 9 presents the performance of MTAKD compared with other teacher models. The model requires only 11,230 KB with an inference time of 105 ms, making it 49.8 times smaller and 352 times faster inference time compared to the largest teacher model. Figure 11 shows the position of MTAKD compared to other models. The proposed framework delivers the fastest inference time, the smallest model size, and achieves the highest accuracy. MTAKD positions in the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset are shown in Fig. 12. The MTAKD framework achieves the second-highest accuracy of 44.75%, 1.11% lower than the highest accuracy model of RegNetY32GF. However, it offers the fastest inference time and requires the smallest memory among all models. These results demonstrate the efficiency of MTAKD in balancing the trade-off between accuracy, size, and speed.

The consistent performance across dermoscopic and clinical datasets reflects the adaptability to various image conditions. This further reinforces the suitability of the proposed MTAKD framework for mobile deployment. By compressing the model size, ensuring fast inference time, high accuracy, and providing more explainable outputs, this framework fulfills the requirements for edge AI models for skin disease diagnosis. The ability to run directly on low-resource devices and provide on-device visual explanations supports its practical use in remote areas. This can assist general practitioners by offering interpretable visual regions that complement their clinical judgment.

Discussion

The experimental results of the proposed Multi-Teacher Agreement Knowledge Distillation (MTAKD) framework reveal its efficiency in improving model performance and deployment feasibility. MTAKD uses the agreement among teachers as an indicator of knowledge reliability and weights the prediction output from each teacher for every sample. This approach guides the student model using more consistent weighted predictions. By integrating three novel algorithms, the framework successfully addresses several challenges related to model performance, model size, inference time, and explainability for limited-resource devices. These outcomes confirm that the proposed framework is suitable for practical deployment in edge AI for skin disease diagnosis.

Each component of the MTAKD framework contributed to the performance improvement. As the main knowledge source, the Agreement Weighted Knowledge Distillation (AWKD) guides the student model to learn from more reliable agreement-based teacher predictions. The Attention Agreement Knowledge Distillation (AAKD) enhances the feature map to focus on important regions from the attention map. This approach improves the explainability aspect of the student model as measured by insertion and deletion metrics. The Relational Agreement Knowledge Distillation (RAKD) completes the framework by guiding the student model based on the relationships between data. This integrated approach demonstrated increasing student model performance, as shown by the ablation results.

MTAKD also outperforms the benchmark frameworks on both datasets. MTAKD achieved the highest accuracy with the highest margin of 0.75%. This result is also reflected in other metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score. The same trend is also seen in the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset. The MTAKD framework improved by 1.1% in mean accuracy compared to the highest accuracy in benchmark frameworks. These results confirm that teacher agreement provides more informative and richer knowledge to the student model.

While the performance gains may appear modest, prior research in knowledge distillation has shown that even small improvements can be valuable, and the proposed MTAKD framework consistently achieves performance gains across both datasets. From a clinical value perspective, the improvement percentages translate into a substantial number of additional correctly classified cases when applied at scale in clinical environments. For malignant skin lesions with cases like melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, each additional correct classification may represent an earlier detection that can directly influence patient survival. In this context, the gain in the proposed MTAKD framework can translate into meaningful improvements in survival outcomes and hold significant clinical value. From the perspective of general practitioners in rural teledermatology, incremental improvements reduce false negatives that risk missed diagnoses and false positives that may lead to unnecessary referrals. Both outcomes are critical in healthcare settings where access to dermatology specialists is limited. More importantly, these performance gains were achieved in the small student model under strict model-size constraints, highlighting its value for clinical applicability.

The accuracy of Fitzpatrick17k-C remains much lower than on ISIC 2019. This gap can be attributed to the dataset characteristics. Fitzpatrick17k-C contains 114 classes with severe imbalance and a smaller sample size per class, while ISIC 2019 has only 8 classes with larger representation. Moreover, Fitzpatrick17k-C consists of clinical images with six diverse skin tones of Fitzpatrick17k scales, variable lighting, and many background regions that are not focused only on the diseases. These challenges are consistent with DIME evaluation, where Fitzpatrick17k-C shows more complex feature distributions, resulting in more than twice the scores compared to the ISIC 2019 dataset. Even with this difficulty, the MTAKD framework still achieves higher performance compared to the other frameworks.

In addition to improving model performance, the MTAKD framework also succeeds in improving the explainability performance. This is reflected by higher insertion scores and lower deletion scores across both datasets. These results mean that the attention maps generated by the student model trained with MTAKD highlight more relevant pixels. The lightweight nature of attention map generation, combined with the improved overall performance, further enhances the explainability of AI in edge mobile deployments.

The practicality of deploying the MTAKD framework on edge devices is demonstrated using a mobile application prototype. The student model achieves a 49.8 times smaller size and 352 times faster inference time compared to the largest teacher model. The MTAKD framework achieves the fastest inference time, smallest model size, and highest accuracy of 87.53% on the ISIC 2019 dataset. A similar result is also observed on the Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset, where it achieves the second-best accuracy, just behind the largest teacher model. The prototype shows that the application can run inference smoothly on mobile devices without any internet connection. The inference results also show an overlay of the attention map to provide more explainability to general practitioners.

While prediction agreement among teachers generally indicates reliable knowledge, there remains a potential limitation if multiple teachers converge on the same incorrect prediction. In such cases, the agreement itself may amplify misleading knowledge. The MTAKD framework mitigates this risk by combining agreement-weighted teacher supervision with ground-truth cross-entropy loss to ensure the student remains anchored by the true label. Despite this, the effectiveness of the framework still depends on having strong and diverse teacher models, since underperforming teachers can reduce the quality of the knowledge transferred to the student model.

Although this research focuses on knowledge distillation algorithm development, future work can include clinical validation and expert evaluation to better assess real-world impacts. Future research may also explore performance optimization and practical deployment of edge AI in clinical settings. Adopting federated learning by utilizing knowledge distillation can improve patient privacy. Enhancing the teacher model loss functions to better capture class relationships could provide richer knowledge for the student model. Additionally, using vision transformers as teacher models may improve the quality of knowledge because of better feature representation. Finally, integrating explainable AI with language models to generate descriptive justifications for diagnosis can further improve the reasoning behind the diagnosis.

Conclusion

This research finding fills the research gap by proposing the MTAKD framework, which considers agreement among teacher predictions. The results prove that the model successfully outperforms previously established KD benchmark frameworks not only in classification performance but also in explainability performance.

With respect to the research objective within the application domain, the deployed proposed MTAKD framework on the application prototype, further verifies the practical solution for providing an edge AI solution for skin disease diagnosis. This approach can serve as a potential solution to the scarcity of dermatology specialists in remote rural areas.

Data availability

Both datasets used in this research are publicly accessible. The ISIC 2019 dataset is available at: https://challenge.isic-archive.com/data. The Fitzpatrick17k-C dataset can be accessed at: https://github.com/mattgroh/fitzpatrick17k, and the cleaned version CSV is available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12739457.

References

Coustasse, A., Sarkar, R., Abodunde, B., Metzger, B. J. & Slater, C. M. Use of teledermatology to improve dermatological access in rural areas. Telemedicine e-Health. 25, 1022–1032 (2019).

Zama, D. et al. Perspectives and challenges of telemedicine and artificial intelligence in pediatric dermatology. Children 11, 1401 (2024).

Vasconcelos, M. J. M. et al. Improving teledermatology referral with Edge-AI: mobile app to foster skin lesion imaging standardization. in 158–179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20664-1_9

Daoudi, S., Bellebna, M. E. A., Elbahri, M., Mazari, S. & Alaoui, N. Running convolutional neural network on tiny devices. in International Conference on Advances in Electronics, Control and Communication Systems (ICAECCS) 1–5 (IEEE, 2023). 1–5 (IEEE, 2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAECCS56710.2023.10105032

Deng, B. L., Li, G., Han, S., Shi, L. & Xie, Y. Model compression and hardware acceleration for neural networks: a comprehensive survey. Proc. IEEE. 108, 485–532 (2020).

Han, S., Pool, J., Tran, J. & Dally, W. J. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural networks. (2015).

Zhang, R. & Chung, A. C. S. EfficientQ: an efficient and accurate post-training neural network quantization method for medical image segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 97, 103277 (2024).

Hinton, G., Vinyals, O. & Dean J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. (2015).

Sarfraz, F., Arani, E. & Zonooz, B. Knowledge distillation beyond model compression. in 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR) 6136–6143 (IEEE, 2021). 6136–6143 (IEEE, 2021). (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR48806.2021.9413016

Wang, Y. et al. SSD-KD: A self-supervised diverse knowledge distillation method for lightweight skin lesion classification using dermoscopic images. Med. Image Anal. 84, 102693 (2023).

Niyaz, U., Sambyal, A. S. & Bathula, D. R. Leveraging different learning styles for improved knowledge distillation in biomedical imaging. Comput. Biol. Med. 168, 107764 (2024).

You, S., Xu, C., Xu, C. & Tao, D. Learning from multiple teacher networks. in Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 1285–1294ACM, New York, NY, USA, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3097983.3098135

Zhang, H., Chen, D. & Wang, C. Confidence-aware multi-teacher knowledge distillation. in ICASSP –2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 4498–4502 (IEEE, 2022). 4498–4502 (IEEE, 2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9747534

Li, G. et al. Multistage feature fusion knowledge distillation. Sci. Rep. 14, 13373 (2024).

Chen, W. C., Chang, C. C. & Lee, C. R. Knowledge distillation with feature maps for image classification. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science 200–215Springer, Cham, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20893-6_13

Park, W., Kim, D., Lu, Y. & Cho, M. Relational knowledge distillation. in 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 3962–3971IEEE, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.00409

Wang, G. H., Ge, Y. & Wu, J. Distilling knowledge by mimicking features. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1–1 https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3103973 (2021).

Bao, Z., Zhu, D., Du, L. & Li, Y. A contrast enhanced representation normalization approach to knowledge distillation. Sci. Rep. 15, 13197 (2025).

Yang, G., Yu, S., Sheng, Y. & Yang, H. Attention and feature transfer based knowledge distillation. Sci. Rep. 13, 18369 (2023).

Zagoruyko, S. & Komodakis, N. Paying more attention to attention: improving the performance of convolutional neural networks via attention transfer. (2017).

Zeyu, D. et al. A Grad-CAM-based knowledge distillation method for the detection of tuberculosis. in. International Conference on Information Management (ICIM) 72–77 (IEEE, 2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIM58774.2023.00019

Guo, Z., Yan, H., Li, H. & Lin, X. Class attention transfer based knowledge distillation. in 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11868–11877IEEE, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01142

Wang, T. et al. Attention-guided knowledge distillation for efficient single-stage detector. in. IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME) 1–6 (IEEE, 2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICME51207.2021.9428177

Wang, Y. & Xu, Y. Relation-based multi-teacher knowledge distillation. in International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024). 1–6 (IEEE, 2024). (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN60899.2024.10650189

Xie, Z. et al. MoDE: A mixture-of-experts model with mutual distillation among the experts. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 38, 16067–16075 (2024).

Ganta, D. P., Gupta, H., Das & Sheng, V. S. Knowledge distillation via weighted ensemble of teaching assistants. in IEEE International Conference on Big Knowledge (ICBK) 30–37 (IEEE, 2021). 30–37 (IEEE, 2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICKG52313.2021.00014

Ashwath, V. A., Ayyagari, A. S., Deebakkarthi, C. R. & Arun, R. A. Building of computationally effective deep learning models using attention-guided knowledge distillation. in 12th International Conference on Advanced Computing (ICoAC) 1–8 (IEEE, 2023). 1–8 (IEEE, 2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICoAC59537.2023.10249491

Leng, B., Leng, M., Ge, M. & Dong, W. Knowledge distillation-based deep learning classification network for peripheral blood leukocytes. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 75, 103590 (2022).

EL-Assiouti, O. S., Hamed, G., Khattab, D. & Ebied, H. M. HDKD: hybrid data-efficient knowledge distillation network for medical image classification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109430 (2024).

Meseguer, P., del Amor, R. & Naranjo, V. M. I. C. I. L. Multiple-instance class-incremental learning for skin cancer whole slide images. Artif. Intell. Med. 152, 102870 (2024).

Winata, A., Afny Catur Andryani, N. & Santoso Gunawan, A. Ford Lumban Gaol, and. Diverse representation knowledge distillation for efficient edge AI teledermatology in skin disease diagnosis. IEEE Access. 13, 106618–106633 (2025).

Chandrasegaran, K., Tran, N. T., Zhao, Y. & Cheung, N. M. Revisiting label smoothing and knowledge distillation compatibility: what was missing? (2022).

Shahar, D. J. Minimizing the variance of a weighted average. Open. J. Stat. 07, 216–224 (2017).

Hampel, F. R. Robust Statistics: the Approach Based on Influence Functions (Wiley, 2007).

Iglewicz, B. & Hoaglin, D. C. How To Detect and Handle Outliers (ASQC Quality, 1993).

Maurício, J., Domingues, I. & Bernardino, J. Comparing vision Transformers and convolutional neural networks for image classification: a literature review. Appl. Sci. 13, 5521 (2023).

Tschandl, P., Rosendahl, C. & Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data. 5, 180161 (2018).

Codella, N. C. F. et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: a challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). (2017).

Hernández-Pérez, C. et al. BCN20000: dermoscopic lesions in the wild. Sci. Data. 11, 641 (2024).

Abhishek, K., Jain, A. & Hamarneh, G. Investigating the Quality of DermaMNIST and Fitzpatrick17k Dermatological Image Datasets. (2024).

Groh, M. et al. Evaluating deep neural networks trained on clinical images in dermatology with the Fitzpatrick 17k dataset. (2021).https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW53098.2021.00201

Aljohani, K. & Turki, T. Automatic classification of melanoma skin cancer with deep convolutional neural networks. AI 3, 512–525 (2022).

Chen, K., Chen, S., Wang, G., Wang, C. & CGPNet Enhancing medical image classification through channel grouping and partial convolution network. in IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom) 1827–1834 (IEEE, 2023). 1827–1834 (IEEE, 2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/TrustCom60117.2023.00248

Matthew, S. et al. Empirical study on modified Pre-Trained CNN architectures for Fitzpatrick17k skin diseases prediction modelling. J. Comput. Sci. 21, 1504–1511 (2025).

Dominguez, M. & Finnell, J. T. Unsupervised SoftOtsuNet augmentation for clinical dermatology image classifiers. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 329–338 (2023). (2023).

Zhang, P., Wang, H., Naik, N. & Xiong, C. & richard socher. DIME: an information-theoretic difficulty measure for AI Datasets. in NeurIPS 2020 Workshop: Deep Learning through Information Geometry (2020).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L. C. MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4510–4520 (IEEE, 2018). 4510–4520 (IEEE, 2018). (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00474

Petsiuk, V., Das, A. & Saenko, K. RISE: randomized input sampling for explanation of black-box models. (2018).

Ignatov, A. et al. AI Benchmark: All about deep learning on smartphones in 2019. in. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW) 3617–3635 (IEEE, 2019). (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW.2019.00447

Ignatov, A. et al. AI benchmark: running deep neural networks on android smartphones. in 288–314 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11021-5_19

Funding

This research was funded based on JST CREST under funding ID JPMJCR20D1, with Ford Lumban Gaol and Tokuro Matsuo as the grant recipients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.W.; Methodology: A.W., N.A.C.A., and F.L.G.; Software: A.W.; Investigation: A.W.; Validation: A.W.; Formal analysis: A.W., and N.A.C.A.; Writing – original draft: A.W.; Writing – review and editing: N.A.C.A., A.A.S.G., F.L.G., and T.M.; Supervision: A.A.S.G., F.L.G., and T.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Winata, A., Andryani, N.A.C., Gunawan, A.A.S. et al. MTAKD: multi-teacher agreement knowledge distillation for edge AI skin disease diagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 44314 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27038-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27038-1