Abstract

The meniscus is a crescent-shaped knee structure that helps stabilize the joint. This study investigates the molecular mechanism of photobiomodulation (PBM) at various wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710 and 1064 nm) and energy densities (3, 15, 30 and 60 J/cm2) affects mitochondrial function and cell proliferation in Meniscus-derived stem cells (MeSCs). We used LED light to irradiate human MeSCs and assessed intracellular calcium (Ca2⁺), cytochrome C oxidase (CCO) activity, nitric oxide (NO) concentrations, cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and cell proliferation. The results showed that intracellular Ca2⁺ levels and ROS production increased as PBM energy density increased, whereas CCO activity and NO concentration remained unchanged. Irradiation at 700–710 and 1064 nm with energy densities of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 improved proliferation and of MeSCs, with the most significant effect at 15 J/cm2. However, all other PBM conditions reduced mitochondrial function and proliferative capacity. Inhibition of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) Ca2+ channel reduced PBM-induced elevations in Ca2+ and ROS at all wavelengths and prevented the associated changes in proliferation. These findings establish a dose-dependent effect of PBM on MeSCs mediated by TRPV1-Ca2⁺-ROS signaling and support its potential application in cytotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The meniscus is a cartilaginous component of the knee joint that transmits load. However, it is highly susceptible to sports injuries and has poor self-repairing ability1,2. Continued deterioration of the meniscus frequently results in wear and tear and degeneration of the knee cartilage, in turn leading to osteoarthritis. Some patients may also require total knee replacement surgery. While the prevalence of meniscus injuries is typically higher in middle-aged and older adults, it is increasing in young adults1,3. Surgery is the most commonly used medical intervention for meniscus injuries, but the success rate tends to be low4, often resulting in an unstable mechanical structure that renders the patient susceptible to osteoarthritis, which severely affects their quality of life and ability to work, resulting in a significant loss of labor force in society. Meniscus injuries impose a heavy economic burden on patients, as treatment and recovery costs are difficult to reduce in the short term4,5.

Regenerative medicine, which utilizes stem cells, holds great promise for developing new treatment technologies for meniscal repair. Research on meniscus repair has focused primarily on stem cell injection therapy1,3,6. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) injections are not associated with any safety issues or side effects7,8. Although the number of clinical trials on the efficacy of MSC therapy is limited, early clinical results have been encouraging9,10. This study investigated meniscus-derived stem cells (MeSCs), a specific MSC type found primarily in the lateral one-third of the menisci, known as the Red-Red zone, and which can undergo self-repair due to their blood supply11,12. It is hypothesized that MeSCs, due to their tissue-specific origin, may be better adapted to the meniscal microenvironment than MSCs from other sources10,13. MeSCs resemble MSCs in their morphological characteristics, having the same cell phenotype (CD14+, CD29+, CD44+, CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, and CD45-), and osteogenic, lipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation potential11,14. A previous findings indicate that DMEM-low glucose is the most suitable basic culture medium for MeSC culture, as it supports higher proliferative and migratory capacities15. Achieving successful survival and expansion of cells from meniscal tissue remains challenging for two main reasons. First, the harvested tissue for isolating MeSCs as seed cells for cytotherapy is limited in quantity. Second, the tissue has often been exposed to pathologically harsh microenvironmental conditions, which may impair MeSC viability. Optimization of pretreatment strategies during in vitro expansion would therefore be advantageous for meniscal repair. It is hypothesized that PBM can promote MeSC proliferation and reduce cellular senescence, therefore serving as an effective pretreatment approach for MeSCs in cytotherapy.

Photobiomodulation (PBM) is a non-invasive therapeutic modality that employs lasers or low-intensity light-emitting diodes (LEDs). It can be usedclinically to promote wound healing in various tissues16, and used in cytotherapy research for pretreat the seed cells to promoteproliferation, migration, differentiation potential and the pluripotency16. Studies have shown that it can influence cell proliferation, osteogenic/adipogenic/chondrogenic differentiation, and migration of MSCs in vitro17,18. Therefore, this study hypothesized that analogous effects in MeSCs may result in effective preliminary treatment for meniscus injuries. While the effects of PBM on various stem cell types have been investigated, the mechanisms underlying these effects remain unclear.

To date, research on the underlying mechanisms of PBM remains insufficient. Although four principal hypotheses have been proposed to explain its core mechanisms, their precise contributions are still being studied: (1) Cytochrome c oxidase (CCO) activity: PBM may increase CCO activity, elevating mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and ATP production. This process activates signaling pathways and stimulates the release of growth factors. (2) Nitric oxide (NO): NO can inhibit CCO activity by non-covalent binding to the CuB site of the enzyme, whereas photon-induced dissociation of this complex restores CCO activity. (3) Intracellular calcium (Ca2+): PBM can activate photosensitive ion channels, promoting Ca2+ influx and increasing intracellular calcium concentrations. This increase contributes to transcription factor activation and subsequent effects on proliferation, differentiation, and migration.Despite these hypotheses, most PBM studies have not provided systematic experimental evidence to validate these hypotheses. Some evidence suggests that specific hypotheses may apply to certain cell types while excluding others. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms by which PBM exerts its effects vary across different cell types. For example, studies in human adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) revealed that 980-nm near-infrared (NIR) light increases cell viability and ATP production primarily through elevated Ca2+ levels, rather than direct CCO activation. On the other hand, 810-nm irradiation appears to act through a different mechanism, although the details remain unclear19. Another study demonstrated that LED illumination at 670, 728, 770, 830, and 880 nm increases neuronal metabolism by activating CCO20. However, studies on fibroblasts indicate that PBM-mediated proliferation and metabolic stimulation are not dependent on CCO21. The NO hypothesis also remains debated. Research suggests that PBM can alter the levels of various forms of NO, either promoting or inhibiting cellular functions, but direct experimental support is limited21. In comparison, several studies provide evidence that PBM increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production through increased Ca2+ levels, distinguishing this pathway from the CCO- and NO-related mechanisms22,23,24,25.

A previous study explored the effects of PBM on MeSCs but did not compare differences between different PBM wavelength or examine underlying mechanisms26. The present study aimed to investigate the mechanisms associated with the effects of PBM on mitochondrial function and cell proliferation. We investigated whether the effect of PBM on MeSCs involves increased CCO activity, up-regulation of NO, or enhanced Ca2+ levels. We used LED light of varying wavelengths and energy densities to irradiate human MeSCs or mitochondria isolated from MeSCs, and examined Ca2+ and CCO activity using colorimetric methods. The concentrations of NO were assessed using the improved Griess method, cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays, ΔΨm via fluorescence, ROS by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), and proliferation via cell counting. We discovered that the primary mechanism by which PBM affects MeSCs is the upregulate intracellular Ca2+ by activating the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) Ca2+ channel. In contrast, the changes in CCO activity and the rise in NO concentration were not directly associated with the effects of PBM. As no previous studies have compared the effects of different irradiation parameters on MeSCs, four wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm) and four energy densities (3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2) were randomly selected as exposure parameters in this study.

Methods

MeSC culture

Meniscus tissue samples were obtained from a male human donor who underwent total knee arthroplasty at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University (Ethics approval No. EFY202500050). Informed consent was obtained from the donor. The donors were recruited from male patients at the age range of 66–75 years who had been diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis, with no evidence of rheumatoid arthritis, acute post-traumatic osteoarthritis, or gout. The collection of human samples adhered to the National and International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS) and the Guideline for Stem Cell Research & Therapy. The surface phenotypes of the cells were assessed using flow cytometry, and the cells’ ability to differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages was determined. The results confirmed similar characteristics to those of MSCs and were in agreement with the findings of other studies27,28,29.

The cells were cultured in low-glucose DMEM (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, A5256501, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM GlutaMAX (Solarbio, Beijing, China) within a humidified incubator (37 ℃, 5% CO2). Cells from the third passage were harvested and seeded into 35-mm culture dishes and grown to 80% confluence. The culture medium was replaced 24 h after initial seeding and subsequently every three days. For passaging, the cell monolayer was digested with 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C for 2 min. All the assays in this study were repeated six times independently.

Cell irradiation

Cells were divided into sixteen groups treated with varying energy densities (0, 3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2) and different wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm) once. Cells without irradiation served as the control group.

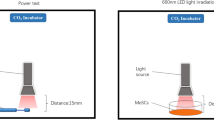

The light source used for irradiation was a Flashlight K31 Series Research Light Source device (CZLIGHT Sdn Bhd, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). The output power at the material irradiation distance was determined with an SM206E (for testing 400–405, 500–505, and 700–710 nm) and SM206-NIR (for testing 1064 nm) photo power meter (Xin Bao Sdn Bhd, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). Irradiation was conducted in a CO2 temperature-controlled incubator at 37 °C. The Light-Emitting Diode (LED) light source was maintained at a distance of 17 mm from the cells during irradiation, and the spot size was 35 mm in diameter (Fig. 1). The power meter was used to determine the power density (W/cm2) in the area of light exposure, and the required irradiation time was calculated using the following formula:

Irradiation of cells. MeSCs were cultured for three passages. (a) The power density (W/cm2) in the area of light exposure was measured with a power meter, and the irradiation time for each energy density (0, 3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2) was calculated using Formula 2. (b) The MeSCs were irradiated accordingly.

The measured power density results and irradiation times of the cells are shown in Table 1.

Ca2+ measurements

The levels of calcium were assessed at 4 h after irradiation using a kit (ab102505, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) as recommended. 24 h after irradiation, the cells were detached from the culture dishes with trypsin (without EDTA, SM-2003, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and washed with DMEM(Low-glucose). Resuspend with DMEM (containing calcium ions), let it stand for 30 min, then centrifuge at 350g for 1 min to remove DMEM. Then, 2 × 106 cells were resuspended in 500 μL of the provided assay buffer, utrasonic cell lysis in ice, and were centrifuged at 15,600×g for 4 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, mixed with the chromogenic reagent, and incubated in the dark for 10 min. Absorbances at 575 nm were measured in a microplate reader (Varioskan Flash 3001; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The standard curve was compiled using standard solutions with known concentrations which were provided by the manufacturer. The concentrations of the standards were plotted on the X-axis, with absorbances on the Y-axis. The curve fitting method was used to fit the data points to obtain the equation of the standard curve. The concentration of the samples was calculated using the standard curve. The relative Ca2+ levels were then calculated for each experimental group relative to the control group for statistical analyses.

CCO activity measurement

Mitochondria were isolated from cells 12 h after irradiation using a mitochondrial isolation kit (ab65320, Abcam). CCO activity was measured at 12 h after irradiation in the isolated mitochondrial fractions with a commercial assay kit (ab239711, Abcam). The mitochondrial suspension was adjusted to 0.2 µg/µL in the supplied assay buffer, and 10 µL of the sample was added to each well of a microplate. The reaction was initiated by adding the substrate solution, and enzymatic kinetics were monitored by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 550 nm (A550) for 30 min at 37 °C with a microplate reader. CCO activity was calculated from the linear rate of absorbance decrease and normalized to total mitochondrial protein content.

NO concentration measurements

The NO concentrations were measured at 12 h after irradiation using a kit (ab272517, Abcam) as directed. Cells were harvested and centrifuged as described above, with the resulting supernatant used for the NO assay. The sample was mixed with the working reagent and incubated for 10 min at 60 °C, followed by centrifugation at 150 × g for 1 min. The absorbance of the supernatant at 540 nm was read in the microplate reader. The NO concentrations were determined from a standard curve compiled with standards provided by the manufacturer.

Measurement of ROS by ELISA

The levels of ROS were assessed at 6 h after irradiation using an ELISA kit (MBS166870, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were harvested as described above and were resuspended to a concentration of 4 × 106 cells in 100 μL of cell lysis buffer. After incubation with shaking at 2–8 °C for 30 min and centrifugation at 13,000×g for 10 min at 2–8 °C, the ROS levels in the supernatants were measured, recording absorbances at 450 nm in the microplate reader.

MTT assay for cell viability

The levels of MTT were assessed at 12 h after irradiation. Irradiated and non-irradiated cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/well in 100 µL medium and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. A solution containing 0.5 mg/mL 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h in the dark. The medium with MTT was then removed from the wells and replaced with DMSO (Solarbio) to solubilize the formazan crystals. Formazan formation was measured spectrophotometrically (Flx 800, Fluorescence Microplate Reader) at 570 and 630 nm, and the net ΔA (570–630) nm was used as an index of mitochondrial function. The results were expressed as a percentage of the control, which was assigned 100% activity.

ΔΨm measurement

The levels of ΔΨm were assessed at 12 h after irradiation using a JC-10 ΔΨm kit (MAK160, Sigma). Irradiated cells were prepared as above. JC-10 Dye Loading Solution was prepared by adding 50 μL of 100 × JC-10 to 5 mL of Assay Buffer A. The cells were treated with 10 μL of 10 × test compounds to induce apoptosis. Negative (vehicle only) and 4HR-treated samples were set up in parallel. Cells were incubated for 24 h. The JC-10 Dye Loading Solution (50 μL per well) was then added to each well and incubated for 30 min in the dark in a 5% CO2 and 37 °C incubator. Assay Buffer B (50 µL) was then added to each well. Fluorescence intensities were measured at 490 and 540 nm in a Multiskan FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The ratio of red/green fluorescence was used to determine the ΔΨm.

Cell proliferation

To evaluate the proliferation of MeSCs after irradiation, passage 3 cells were seeded at 1,500 viable cells/cm2 into 35-mm culture dishes and incubated under standard conditions. The medium was replaced after 24 h and every 3 days thereafter. Cells were then plated at the original seeding density every 10 days.

To assess proliferation, the number of viable MeSCs at the end of each passage were counted via the trypan blue exclusion method. The number of cells that doubled (NCPD) and the cell population doubling time (CPDT) were then calculated using the following formulae30,31,32:

where Nt and Ni are the cell numbers at a specific time point t (Day 10) and at initial seeding (Day 0), respectively. The experiment was performed with six replicates. The NCPD and CPDT values were used to assess the proliferation of MeSCs. Passage 3 cells were chosen for experiments because they provide high purity and strong proliferative capacity while minimizing senescence-related changes. At this stage, cells typically preserve essential biological properties such as differentiation potential and immunosuppressive function, which may decline in higher passages due to increased oxidative stress, cellular aging, and reduced multipotency.

ELISA

Total Bcl-2, total CXCR-4, total Cyclin D1, total Bax, total Caspase-3, total Caspase-9, total p21, total p16, and total p53 were quantified using commercially available ELISA kits (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). MeSCs were harvested from 6-well plates or T25 flasks 48 h after irradiation by trypsinization and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cell pellets (4 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 100 μL lysis buffer, incubated on ice (2–8 °C) with shaking for 30 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 2–8 °C. The resulting cell lysates were collected and immediately analyzed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. ELISA absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (FLx800; Agilent, CA, USA).

Standard solutions provided by the manufacturer were used to generate standard curves. Absorbance values obtained from the microplate reader were plotted as the concentration of each standard (X-axis) against its corresponding signal intensity (Y-axis). A curve-fitting method was applied to obtain the standard curve equation, which was then used to determine protein concentrations. Relative expression levels were normalized to the control group for statistical comparison. Experiments were performed in six independent replicates.

Cell senescence assay

In the MTT, ΔΨm measurement and cell proliferation results of this study, we find that the light at the wavelengths of 700–710 and 1064 nm at energy levels of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 increased cell viability, ΔΨm, and proliferation. To verify the effects of 700–710 nm and 1064 nm PBM on alleviating cell senescence, passage 3 cells were seeded on 35 mm cell culture dishes with the density of 4,500 viable cells per cm2, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium 24 h after initial seeding and the cells were irradiated by PBM (3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 of 700–710 nm and1064nm), and then the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every three days until they reached 80% confluence. To passage the cells, MeSCs were separated from the monolayer using 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C for 2 min. One dish was subdivided into three dishes, and the culture continued until passage 6 SA-β-Gal activity was assessed using commercially available ELISA kits (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for the cell senescence assay. The tests were conducted following the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. The experiment was performed in six independent replicates.

Inhibition of Ca2+ channels

By detecting Ca2+, CCO, and NO after irradiation, we found that the upregulation of Ca2+ may be the primary mechanism of PBM on MeSCs. Previous studies have shown that PBM affects Ca2+ in ADSCs through transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) ion channel19. Therefore, we attempted to use a TRPV1 inhibitor to verify the effect of PBM on Ca2+. Capsazepine (CPZ) is a selective inhibitor of the TRPV1 ion channel. CPZ was dissolved in DMSO, and concentrations of 5 μM (2000-fold dilution in culture medium) were used (final DMSO concentration < 0.5%). For the proliferation assay, passage 3 MeSCs were seeded at a fixed density of 1500 viable cells/cm2 into 35-mm cell culture dishes, and were pretreated with CPZ for 24 h, followed by irradiation with 15 J/cm2 PBM of all four wavelengths. The MeSCs were then grown in culture medium for 10 days. For the other assays, a fixed number of 5.0 × 104 cells/well were seeded into 35-mm cell culture dishes, pretreated with CPZ for 24 h, and irradiated with 15 J/cm2 PBM at all four wavelengths. Ca2+, ROS, MTT, ΔΨm, and proliferation assays were then performed as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 27 (IBM, Chicago, IL, US). For data presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality, and Mauchly’s test was applied to verify the sphericity assumption. Based on these assessments, group differences were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) when assumptions were satisfied, or Friedman’s test when assumptions were violated. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied for all analyses. For the data presented in Fig. 11, results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical tests were selected based on data characteristics: the Mann–Whitney U test was used when distributions deviated significantly from normality (assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test) or when variances were unequal (assessed using Levene’s test), while one-way ANOVA was used otherwise. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

This study investigated the mechanism by which PBM affects MeSCs. Four wavelengths of LED light were selected for the experiment: 400–405, 500–505, 700‒710, and 1064 nm. MeSCs were exposed to these wavelengths at four different energy densities, namely, 3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2.

PBM upregulates Ca2+ levels in MeSCs

The results indicated that exposure to LED light led to significant increases in the Ca2⁺ concentrations across all energy densities and wavelengths. At a fixed wavelength, Ca2+ levels rose progressively with increasing energy density. At a fixed energy density, the increase in Ca2+ at 400–405 and 500–505 nm was greater than that observed at 700–710 and 1064 nm (Fig. 2).

Ca2+ concentrations in MeSCs after irradiation. The Ca2+ levels in all PBM-treated groups were significantly higher than those in the control group. Relative levels were calculated relative to levels in the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and the mean value of every sample was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other irradiated groups. The mean value of each irradiated group was compared to the control group and all other irradiated groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

PBM does not affect CCO activities in MeSCs

This study utilized a colorimetric method to assess the impact of PBM on CCO activity in the MeSC mitochondria. The results indicated that CCO activities in MeSCs exposed to various wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm) and different energy densities (3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2) did not change significantly (p > 0.1) (Fig. 3).

CCO activities in MeSCs after irradiation. The CCO activities did not differ significantly between the PBM-treated and control groups. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and the mean value of every sample was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other irradiated groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

PBM does not affect NO concentrations in MeSCs

The production of NO was determined by nitrate reduction to nitrite using the improved Griess method. The results indicated NO levels in MeSCs exposed to wavelengths of 400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm at energy densities of 3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2 did not differ significantly (p > 0.1) (Fig. 4).

NO levels in MeSCs after irradiation. The NO concentrations in the PBM-treated groups did not differ significantly from those in the control group. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and the mean value of every sample was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other irradiated groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

PBM increases ROS levels in MeSCs

The levels of ROS in PBM-irradiated MeSCs were measured by ELISA. At a fixed wavelength, ROS levels increased progressively with increasing energy density. At a fixed energy density, increases at 400–405 and 500–505 nm was higher than at 700–710 and 1064 nm (Fig. 5). This pattern was consistent with the findings for Ca2+ (Fig. 5).

ROS levels in MeSCs after irradiation. ROS levels in all PBM-irradiated groups were significantly higher than those in the control group. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and the mean value of every sample was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other irradiated groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

Cell viability was increased in the 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 groups at 700–710 and 1064 nm PBM but was reduced in other groups

This study used MTT assays to assess cell viability in MeSCs following PBM irradiation. Light at 400–505 and 500–505 nm was found to inhibit cell viability at all energy densities, while irradiation at 700–710 and 1064 nm promoted cell viability at 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 (Fig. 6).

Cell viability in MeSCs after irradiation. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other groups irradiated by the same wavelength. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

Effects of irradiation on mitochondrial membrane potentials

Irradiation of 400–405 and 500–505 nm reduced the ΔΨm across all energy densities (Fig. 7a, b). In contrast, light at the wavelengths of 700–710 and 1064 nm at energy levels of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 increased the ΔΨm. However, an energy density of 60 J/cm2 led to a decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 7).

ΔΨm in MeSCs after irradiation. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and the mean value of every sample was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other irradiated groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

Proliferation in MeSCs following irradiation

Exposure to light at the wavelengths of 400–405 and 500–505 nm resulted in a decrease in NCPD and an increase in CPDT values at all energy densities (Fig. 8a, b). In contrast, light at wavelengths of 700–710 and 1064 nm applied at energy densities of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 induced a rise in NCPD and a decrease in CPDT (Fig. 8c, d). At an energy density of 15 J/cm2, NCPD reached its highest level, while CPDT was reduced to its lowest level. However, when the energy density was increased to 60 J/cm2, NCPD decreased while CPDT increased (Fig. 8c, d).

NCPD and CPDT values in MeSCs after irradiation. (a) NCPD represents the number of cell doublings occurring within a specified time period, and is used to assess cell proliferation. (b) CPDT refers to the time required for a cell population to double in number, serving as a measure of growth rate. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and the mean value was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using either the Mann–Whitney non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. Mean values of each irradiated group were compared with both the control group and all other irradiated groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

Effects of irradiation on cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and cellular senescence-associated proteins in MeSCs

To investigate the effects of PBM on apoptosis, cellular senescence, and the expression of cell cycle-related proteins in MeSCs, ELISA assays were performed. Expression levels of Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, CXCR-4, Bax, and Caspase were measured in the 15 J/cm2 groups exposed to different wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm). At 400–405 and 500–505 nm, Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, and CXCR-4 were significantly downregulated (Fig. 9a–c), whereas Bax, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, p21, p53, and p16 were significantly upregulated (Fig. 9d–i). At 700–710 and 1064 nm, Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, and CXCR-4 were significantly upregulated (Fig. 9a–c), while Bax, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, p21, p53, and p16 were significantly downregulated (Fig. 9d–i).

Analysis of the levels of proteins after irradiation of 15 J/cm2 PBM. Protein expression was measured with ELISA at 48 h after irradiation. Relative levels were expressed as changes compared with the control group. Cells were obtained from a single donor, and six independent replicates were performed. The mean value of each irradiated group was compared with the control group and all other groups irradiated at the same wavelength. Groups were compared using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

PBM at 700–710 nm and 1064 nm with energy densities of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 alleviated cellular senescence in MeSCs

Previous studies have shown that PBM can decelerate cellular aging33. Based on MTT, ΔΨm, and cell counting results indicating that irradiation at 700–710 and 1064 nm with 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 was beneficial to MeSCs, ELISA was used to measure the senescence marker β-GAL in passage 6 MeSCs. β-GAL levels in all PBM-treated groups were lower than in the control group, with the most significant downregulation observed in the 15 J/cm2 group (Fig. 10).

Effect of PBM on the senescence of passage 6 MeSCs. Relative β-GAL levels in all PBM-treated groups were significantly lower than in the control group. Relative levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates, and mean values were used for group comparisons. Groups were compared using either Friedman’s non-parametric test or repeated-measures ANOVA. The mean value of each irradiated group was compared with that of the control group. ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Inhibition of TRPV1 blocks the effect of PBM on MeSCs

To investigate the role of TRPV1 in controlling Ca2+ levels in MeSCs and explore the relationship between Ca2+ levels and alterations in cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, cell proliferation and cell cycle/cell apoptosis/cell senescence, cells were treated with the TRPV1 inhibitor CPZ. The above results indicate that wavelengths of 700–710 nm and 1064 nm at an energy density of 15 J/cm2 significantly enhanced the mitochondrial function and proliferation capacity of MeSCs. Additionally, applying 15 J/cm2 across all groups led to an increase in Ca2⁺ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels. Consequently, we selected various wavelengths at 15 J/cm2 to investigate the effect of the TRPV1 inhibitor on MeSCs. The MeSCs were irradiated with LED light at various wavelengths, with a power density of 15 J/cm2. The results demonstrated that CPZ blocked the effects of PBM on Ca2+ levels, ROS levels, cell viability, ΔΨm, cell proliferation, and the regulation of Bcl-2, Bax, Cyclin D1, CXCR-4, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, p16, p21, and p53 (Fig. 11).

Ca2+ concentrations, ROS levels, cell viability (MTT), ΔΨm, ATP levels, NCPD, CPDT and protein expression levels following incubation with a TRPV1 inhibitor (CPZ). The TRPV1 inhibitor (CPZ) was incubated with MeSCs, followed by irradiation with 15 J/cm2 of light at wavelengths 400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm. The Ca2+ concentration, ROS concentration, cell viability (MTT), ΔΨm, NCPD and CPDT values, and protein expression levels were compared between the 15 J/cm2-TRPV1 inhibitor and 15 J/cm2 groups. Relative levels of Ca2+ concentration, ROS concentration, cell viability, ΔΨm and protein expression levels were calculated as the relative change from the control group. The experiment was performed with six replicates and the mean value of every sample was use for group comparisons. Group comparisons were performed using either the Mann–Whitney non-parametric test or one-way ANOVA. The mean value of each 15 J/cm2-TRPV1 inhibitor groups was compared with the mean values of 15 J/cm2 groups. n = 6, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, MeSCs were exposed to LED light at specific energy densities (3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2) and wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm). The aim was to detect the effects of various types of LED light on CCO activities, NO levels, ΔΨm, cell viability, ROS, and cell proliferation. The results indicated no significant effects on CCO activities and NO levels at any of the PBM wavelengths and energy densities. However, MeSCs irradiated with 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 at 700–710 and 1064 nm showed slightly increased levels of Ca2+ and ROS, and increased cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cell proliferation. All other light groups resulted in increases in the Ca2+ and ROS concentrations in MeSCs, with reduced levels of cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cell proliferation.

Despite the positive outcomes reported after application of PBM in various cell types34, the mechanism by which PBM influences cells has not been clarified21. The proposed mechanisms include photon absorption by CCO, an increase in NO, and a rise in ROS35. These mechanisms can lead to alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential, cell viability, and ATP production, subsequently influencing cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, metabolism, senescence, and the activities of antioxidant enzymes36. However, there have been few experimental studies verifying the mechanisms underlying PBM effects. For instance, most PBM research on MSCs has primarily focused on the promotion of proliferation, differentiation, and migration, with very few studies exploring the specific mechanisms through which PBM impacts cells21,37. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms of PBM that have been identified have only been verified in a few cell types, and the effects on other cells remain unknown. Therefore, in any PBM research involving cell types, it is essential to conduct a comprehensive and in-depth exploration of the fundamental molecular mechanisms, such as measurements of CCO, NO, and Ca2⁺.

Additionally, research on the impact of PBM on MeSCs is limited. To the best of our knowledge, there are only one report addressing the influence of PBM on MeSCs, and it served as a preliminary exploration of this topic38. The study did not analyze differences in effects among multiple wavelengths of PBM, nor did it investigate fundamental mechanisms. MeSCs are a specific type of MSC, and many previous studies have confirmed the positive effects of PBM on MSCs. Therefore, this study hypothesized that similar or even superior effects in MeSCs could serve as an optimal preliminary treatment for meniscal cytotherapy. The two most critical parameters of PBM are the wavelength and energy density. Previous studies on the effects of PBM on MSCs have used a wide range of wavelengths (from 400 to 1200 nm) and energy densities (from 0.14 to 300 J/cm2)37,39. We randomly selected four wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 700–710, and 1064 nm) and four energy densities (3, 15, 30 J, and 60 J/cm2) from previous reports for our experiments. This approach aimed to facilitate a comprehensive and in-depth exploration of the effects.

The enzyme CCO is expressed in the mitochondria. Two accepted explanations for its role in PBM are as follows: (1) red and near-infrared light can influence the photodissociation of NO from CCO. This process allows oxygen to interact with its site in the binuclear center formed by cytochrome a3 and copper (CuB), leading to an increase in ATP production40. (2) CCO can reduce oxygen to water in the electron transport chain, resulting in increased ATP production by the mitochondria, thus promoting energy metabolism and ROS, and NO production35. It has been found that PBM can influence the activity of CCO in various cell types, including skin fibroblasts41, neurons42, muscle cells43, retinal cells44, and liver cells45. However, while many studies have reported the effects of PBM on these cells, most have relied on the findings of other investigations to speculate that PBM acts through CCO. Very few studies have directly investigated and shown changes in CCO activity resulting from PBM. Recent findings have called into question the dominant role of CCO in photobiomodulation mechanisms. For example, Lima et al.46 developed mouse fibroblast cell models lacking CCO to investigate the effects of 670-nm PBM. They showed that PBM promoted proliferation in these cells, suggesting that the mechanism by which 670-nm PBM influences cells is not solely dependent on CCO. To our knowledge, there is currently no direct experimental evidence showing that PBM affects any type of MSC through CCO. The present findings indicate that the CCO activity in MeSCs, when exposed to all tested wavelengths (400–405, 500–505, 710, and 1064 nm) and energy densities (3, 15, 30, and 60 J/cm2), did not change significantly (Fig. 3). Therefore, we can preliminarily conclude that PBM does not influence MeSCs via CCO.

Nitric oxide can bind to ROS to reduce oxidative stress-mediated damage to cell membranes, proteins, and DNA40. Additionally, it can activate growth factor signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation40. At lower concentrations, NO can bind competitively to hemoglobin A3 and reversibly inhibit CCO activity47. PBM increases the intracellular concentration of NO by promoting the decomposition of nitrite into NO, enhancing the activity of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and dissociating NO from the CuB site to generate free NO40. Although numerous studies have reported the effects of PBM on MSC proliferation, differentiation, and migration, there is limited direct experimental evidence indicating that PBM influences cell function through NO. Lipovsky et al.48. studied the effects of exposure of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) to visible light in the 400–800 nm range. They found that PBM increased intracellular concentrations of NO and ROS, and promoted the proliferation of BMSCs. However, they did not investigate the reasons for the observed increase in NO concentration. Holder et al.49 used 653-nm LED light to irradiate human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). The application of PBM led to increased levels of NO, ATP, cell viability, and cell proliferation. However, the NO levels stimulated by the LED did not decrease due to inhibition of NO synthase. While the authors speculated that the increase in NO concentration induced by PBM was related to CCO, they did not consider other potential factors accounting for NO production. Rajendran et al.50 used 660-nm PBM to irradiate human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs). This treatment resulted in increases in NO concentrations, elevated levels of ROS, enhanced cell proliferation and migration, and reductions in cell apoptosis. However, the study did not investigate the underlying reasons for the increase in NO concentration. The findings of the present study indicate that PBM, regardless of wavelength and energy density, did not lead to significant changes in NO concentrations (Fig. 4). Thus, it can be preliminarily concluded that PBM does not influence MeSCs through NO.

Ca2⁺ regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and senescence through various signaling pathways51,52,53. The results of this study indicate that PBM at all wavelengths and energy densities led to increased Ca2⁺ concentrations. Specifically, the groups treated with light at wavelengths of 700–710 and 1064 nm, at energy densities of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2, experienced smaller increases in Ca2⁺ levels. In contrast, the other treatment groups showed larger increases in Ca2⁺ levels. Additionally, the 700–710 and 1064 nm light groups at the same energy densities exhibited significant increases in cell proliferation, cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cell cycle protein expression. Conversely, the other groups showed significant decreases in these parameters (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9).

The calcium-permeable ion channel TRPV1 enables the entry of calcium ions into the cell, resulting in increased intracellular Ca2+54. TRPV1 can be activated by light of various wavelengths, including blue, green, red, and near-infrared55,56. Research indicates that PBM can influence the proliferation and differentiation of ADSCs by enhancing Ca2+ levels through the TRPV1 channel57. A study found that PBM at wavelengths of 415, 540, and 980 nm activated the TRPV1 channel, increased intracellular calcium levels, markedly up-regulated ROS production, and promoted osteogenic differentiation while inhibiting cell proliferation. In contrast, PBM at wavelengths of 660 and 810 nm up-regulated ROS, increased ATP and ΔΨm levels, and promoted cell proliferation but had no significant effect on osteogenic differentiation58. To investigate the relationship between raised Ca2⁺ levels and ROS concentrations, as well as cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cell proliferation, we introduced a TRPV1 inhibitor into the MeSC culture medium and exposed the cells to PBM irradiation. The results indicated that the TRPV1 inhibitor reduced Ca2⁺ levels across all experimental groups. As a result, the differences in cell proliferation, cell viability, and ΔΨm, between the experimental groups and the control group were significantly reduced. To further explore the cause of the Ca2⁺ elevation, the TRPV1 inhibitor was included in the MeSCs culture medium and the cells were exposed to PBM at different wavelengths, delivering a dose of 15 J/cm2 (Fig. 10). The results indicated that the TRPV1 inhibitor effectively reduced both Ca2+ and ROS concentrations in all experimental groups. Additionally, the observed changes in cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and proliferation capacity were reduced in all groups treated with the TRPV1 inhibitor. Therefore, we propose that the primary mechanism by which PBM affects MeSCs may involve the regulation of Ca2+ levels by TRPV1, leading to an increase in ROS production; however, this process appears to be unrelated to CCO and NO.

Previous studies have reported that PBM can upregulate the expression of cell survival and cell cycle genes while downregulating the expression of apoptosis genes in various cell types59. However, only a few studies have addressed changes in cell survival, cell cycle, and apoptosis proteins in MSCs. In this study, protein expression was measured using ELISA. PBM at 15 J/cm2 with wavelengths of 700–710 and 1064 nm increased the levels of cell survival and cell cycle proteins (Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, CXCR-4) and reduced the levels of apoptosis-related proteins (Bax, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, p16, p21, p53). Wavelengths of 400–405 and 500–505 nm produced the opposite effect (Fig. 9). In TRPV1 inhibition experiments, CPZ blocked the PBM-mediated regulation of these proteins (Fig. 11g–o). These findings suggest that PBM may regulate ROS levels through the TRPV1 calcium channel, affecting cell proliferation and senescence by upregulating cell survival and cell cycle proteins while reducing apoptosis-associated proteins.

ROS are byproducts of cellular oxygen metabolism. Mitochondria have an antioxidant enzyme system that helps clear excessive ROS, maintaining their levels at low concentrations and preventing damage to cells. This system is crucial for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and occurs through various signaling pathways60. PBM can enhance mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP production, and cell viability by slight increases in the ROS concentrations. This process promotes stem cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. However, excessive increases in ROS can lead to oxidative stress and decreased cell viability61. Previous reports indicate that the increase in ROS caused by PBM may be due to the stimulation of CCO. However, these studies have rarely provided direct experimental evidence that PBM increases ROS concentrations in cells through CCO17,18. Experimental evidence regarding the direct effect of PBM on ROS through increased CCO activity have focused primarily on neurons62 and fibroblasts63. Existing reports on the effect of PBM on MSCs through CCO are largely based on indirect experimental evidence suggesting that PBM upregulates CCO activity21,24,37, and there has been no direct experimental confirmation of this supposition. The results of this study indicate that light at 400–405 and 500–505 nm significantly increased ROS at all energy densities. This exposure reduced the proliferation of MeSCs (Fig. 8) and downregulated cell viability (Fig. 6), ΔΨm (Fig. 7) and cell cycle protein expression (Fig. 9). In contrast, light at 700–710 and 1064 nm with energy levels of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 caused only a slight increase in ROS while promoting cell viability (Fig. 6), cell cycle protein expression (Fig. 7), and cell cycle protein expression (Fig. 9). However, light at an energy density of 60 J/cm2 resulted in a significant increase in ROS, which inhibited MeSC proliferation (Fig. 8) and downregulated cell viability (Fig. 6), ΔΨm (Fig. 7), and cell cycle protein expression (Figs. 8, 9). The findings indicate that light at wavelengths of 700–710 and 1064 nm, with energy densities of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 respectively, enhances mitochondrial function and promotes the proliferation of MeSCs. These wavelengths and energy densities are therefore ideal for improving the effectiveness of MeSC cell therapy. A comparison of the results for Ca2⁺ (Fig. 2) and ROS (Fig. 5) reveals that the patterns of upregulation and downregulation for both Ca2⁺ and ROS are synchronous. In addition, our results showed that the effects of PBM on mitochondrial function and proliferation were consistent with the “Biphasic Dose Response” phenomenon. "Biphasic Dose Response" is a phenomenon in the fields of pharmacology and radiobiology. In this phenomenon, a low dose of a medicine or irradiation can provide beneficial stimulation to an organism. For example, a low dose can promote growth and extend lifespan. However, an excessively high dose can produce inhibitory or toxic effects. The results showed that mitochondrial function and cell proliferation are promoted by PBM when the up-regulation of Ca2+ and ROS was within the appropriate range (Ca2⁺, 5.4–19.0% and ROS, 3.2–15.7%), mitochondrial function and cell proliferation were promoted by PBM; when the up-regulation of Ca2+ and ROS was too great (Ca2⁺, 34.6–54.8% and ROS, 34.5–45.7%), mitochondrial function and cell proliferation were enhanced and inhibited by PBM. This phenomenon has been observed in numerous other PBM studies55. This study identified 1064 nm 15 J/cm2 as the optimal PBM parameter for MeSCs proliferation and reduced cellular senescence. The mechanism involves TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ upregulation, which increases ROS concentration. These findings provide preliminary insights into the effects of PBM at different wavelengths and energy densities on the proliferation and cellular senescence of MeSCs. Additionally, they begin to address the current gap in research regarding the molecular mechanisms by which PBM influences MeSCs.

The β-GAL assay results confirmed the effectiveness of PBM in alleviating senescence progression in MeSCs (Fig. 3). Expression levels of senescence-related proteins, including Caspase-3, Caspase-9, p21, p16, and p53, were lower in PBM-treated groups (3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 at 700–710 nm and 1064 nm), indicating that PBM alleviated senescence in MeSCs by down-regulating senescence-associated proteins.

This study has several limitations. The cells used were from an older donor with meniscus injury, which may have resulted in lower cell viability than those from younger, healthier donors. The current study did not collect meniscus tissue from young donors because this would require donors who have experienced severe acute meniscus injuries, which are challenging to find. Furthermore, stem cells cultivated in 2D and 3D environments may exhibit divergent characteristics, potentially influencing the results of experimental studies. To obtain more comprehensive and reliable results, it would be necessary to isolate and culture young-donor-derived MeSCs and test their response to PBM in 2D and 3D culture environments. We were unable to test the mitochondria-bound water hypothesis of the PBM mechanism due to unreliable experimental methods. Addressing these issues will be important in future studies.

Conclusion

In this study, the mechanism by which PBM affects MeSCs and promotes proliferation was investigated. Exposure to 700–710 and 1064 nm light at energy densities of 3, 15, and 30 J/cm2 resulted in moderate increases in Ca2+ and ROS levels, accompanied by elevated cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, cell proliferation, and cell cycle protein expression, along with downregulated expression of apoptosis- and senescence-related proteins. Other irradiation conditions induced more significant increases in Ca2+ and ROS, which were associated with reduced cell viability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cell proliferation, as well as increased expression of apoptosis- and senescence-related proteins. PBM at all tested wavelengths and energy densities did not affect CCO activity or NO concentration. Inhibition of TRPV1 reduced PBM-induced upregulations in Ca2+ and ROS and thus alleviated changes in mitochondrial function, proliferation, and the expression of cell cycle, apoptosis, and senescence-related proteins in MeSCs. Overall, the effect of PBM on MeSCs appears to be primarily due to the upregulation of Ca2⁺ mediated by activation of TRPV1, leading to an increase in ROS levels, and this effect does not seem to be directly related to CCO activity or NO concentration. The effects of PBM on mitochondrial function and proliferation were consistent with the “Biphasic Dose Response” phenomenon. When the energy density is lower than 15 J/cm2, PBM can increase intracellular ROS concentration by up-regulating Ca2⁺, thereby promoting the proliferation of MeSCs. However, when the energy density exceeds 15 J/cm2, a more significant upregulation of Ca2⁺ leads to excessive ROS, which counteracts the positive effect of PBM on MeSCs and even inhibits their proliferation. These results provide a theoretical basis and preliminary reference for the use of PBM as a cell and processing tool for MeSC therapy. Further in-depth investigations into the molecular mechanisms associated with PBM and the optimal parameters for application in MeSCs are required.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 27 (IBM, Chicago, IL, US). For data presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality, and Mauchly’s test was applied to verify the sphericity assumption. Based on these assessments, group differences were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) when assumptions were satisfied, or Friedman’s test when assumptions were violated. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied for all analyses. For the data presented in Fig. 11, results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical tests were selected based on data characteristics: the Mann–Whitney U test was used when distributions deviated significantly from normality (assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test) or when variances were unequal (assessed using Levene’s test), while one-way ANOVA was used otherwise. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Luvsannyam, E., Jain, M. S., Leitao, A. R., Maikawa, N. & Leitao, A. E. Meniscus tear: Pathology, incidence, and management. Cureus 14, e25121 (2022).

Luo, A. et al. Visual interpretable MRI fine grading of meniscus injury for intelligent assisted diagnosis and treatment. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 97 (2024).

Wiley, T. J. et al. Return to play following meniscal repair. Clin. Sports Med. 39, 185–196 (2020).

Faucett, S. C. et al. Meniscus root repair vs meniscectomy or nonoperative management to prevent knee osteoarthritis after medial meniscus root tears: Clinical and economic effectiveness. Am. J. Sports Med. 47, 762–769 (2019).

Centeno, C. J. et al. Regeneration of meniscus cartilage in a knee treated with percutaneously implanted autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Med. Hypotheses 71, 900–908 (2008).

van de Graaf, V. A. et al. Effect of early surgery vs physical therapy on knee function among patients with nonobstructive meniscal tears: The ESCAPE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 320, 1328–1337 (2018).

Sekiya, I. et al. Additional use of synovial mesenchymal stem cell transplantation following surgical repair of a complex degenerative tear of the medial meniscus of the knee: A case report. Cell Transpl. 28, 1445–1454 (2019).

Onoi, Y. et al. Second-look arthroscopic findings of cartilage and meniscus repair after injection of adipose-derived regenerative cells in knee osteoarthrits: Report of two cases. Regen. Ther. 11, 212–216 (2019).

Suzuki, S. et al. Morphological changes in synovial mesenchymal stem cells during their adhesion to the meniscus. Lab. Invest. 100, 916–927 (2020).

Ding, G., Du, J., Hu, X. & Ao, Y. Mesenchymal stem cells from different sources in meniscus repair and regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 796367 (2022).

Shen, W. et al. Intra-articular injection of human meniscus stem/progenitor cells promotes meniscus regeneration and ameliorates osteoarthritis through stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4-mediated homing. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 3, 387–394 (2014).

Korpershoek, J. V et al. Selection of highly proliferative and multipotent meniscus progenitors through differential adhesion to fibronectin: A novel approach in meniscus tissue engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021).

Bian, Y., Wang, H., Zhao, X. & Weng, X. Meniscus repair: Up-to-date advances in stem cell-based therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 13, 207 (2022).

Ding, Z. & Huang, H. Mesenchymal stem cells in rabbit meniscus and bone marrow exhibit a similar feature but a heterogeneous multi-differentiation potential: Superiority of meniscus as a cell source for meniscus repair Evolutionary developmental biology and morphology. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 16, 1–14 (2015).

Duangprom, S., Kheolamai, P., Tantrawatpan, C. & Manochantr, S. High glucose inhibits proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 15, 22512 (2025).

Mandal, B. B., Park, S. H., Gil, E. S. & Kaplan, D. L. Stem cell-based meniscus tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 17, 2749–2761 (2011).

Mohamad, S. A., Milward, M. R., Hadis, M. A., Kuehne, S. A. & Cooper, P. R. Photobiomodulation of mineralisation in mesenchymal stem cells. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 20, 699–714 (2021).

Shi, Z., Li, S., Chen, W. & Yan, H. The effect of blue and green light on human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for promoting proliferation and wound healing. Sci. Rep. 15, 14787 (2025).

Wang, Y., Huang, Y.-Y., Wang, Y., Lyu, P. & Hamblin, M. R. Photobiomodulation of human adipose-derived stem cells using 810nm and 980nm lasers operates via different mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 1861, 441–449 (2017).

Wong-Riley, M. T. T. et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: Role of cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4761–4771 (2005).

Quirk, B. J. & Whelan, H. T. What lies at the heart of photobiomodulation: Light, cytochrome C oxidase, and nitric oxide-review of the evidence. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 38, 527–530 (2020).

Al-Hallak, M. A. G., Karkoutly, M., Hsaian, J. A. & Aljoujou, A. A. Effect of combined antimicrobial photodynamic therapy and photobiomodulation therapy in the management of recurrent herpes labialis: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 15, 16264 (2025).

Wang, Q., Chang, H., Shen, Q., Li, Y. & Xing, D. Photobiomodulation therapy for thrombocytopenia by upregulating thrombopoietin expression via the ROS-dependent Src/ERK/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Thromb. Haemost. 19, 2029–2043 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sirt5 desuccinylates Cdc42 to mediate osteoclastogenesis and bone remodeling in mice. Genes Dis. 11, 101002 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Vitamin C alleviates rheumatoid arthritis by modulating gut microbiota balance. Biosci. Trends 18, 187–194 (2024).

Ma, C. et al. Photobiomodulation promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and increases P-Akt levels in vitro. Sci. Rep. 15, 17844 (2025).

Verdonk, P. C. M. et al. Characterisation of human knee meniscus cell phenotype. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 13, 548–560 (2005).

Chahla, J. et al. Assessing the resident progenitor cell population and the vascularity of the adult human meniscus. Arthroscopy 37, 252–265 (2021).

Lee, J., Jang, S., Kwon, J., Oh, T. I. & Lee, E. Comparative evaluation of synovial multipotent stem cells and meniscal chondrocytes for capability of fibrocartilage reconstruction. Cartilage 13, 980S-990S (2021).

Yang, Y.-H.K., Ogando, C. R., Wang See, C., Chang, T.-Y. & Barabino, G. A. Changes in phenotype and differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells aging in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9, 131 (2018).

Oh, M. S. et al. Transcriptomic changes in human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells across culture passages. Genes 15, 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15121626 (2024).

Baharlooi, H., Salehi, Z., Minbashi Moeini, M., Rezaei, N. & Azimi, M. Immunomodulatory potential of human mesenchymal stem cells and their exosomes on multiple sclerosis. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 12, 389–397 (2022).

Arabadjiev, B., Pankov, R., Vassileva, I., Petrov, L. S. & Buchvarov, I. Photobiomodulation with 590 nm wavelength delays the telomere shortening and replicative senescence of human dermal fibroblasts in vitro. Photobiomod. Photomed. Laser Surg. 38, 656–660 (2020).

Khorsandi, K., Hosseinzadeh, R., Abrahamse, H. & Fekrazad, R. Biological responses of stem cells to photobiomodulation therapy. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 15, 400–413 (2020).

Dhilip Kumar, S. S., Nadene Houreld, N. & Abrahamse, H. Influence of biopolymer based gold nanoparticles and photobiomodulation in in vitro wound healing. Sci. Rep. 15, 15793 (2025).

Dos Santos, S. A. et al. Effects of photobiomodulation therapy on oxidative stress in muscle injury animal models: A systematic review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 5273403 (2017).

Wu, C. et al. Remote photobiomodulation ameliorates behavioral and neuropathological outcomes in a rat model of repeated closed head injury. Transl. Psychiatry 15, 8 (2025).

Uchiki, T. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation mitigates ionizing radiation-induced vascular damage in the murine aorta. Sci. Rep. 15, 35708 (2025).

Kasowanjete, P., Dhilip Kumar, S. S. & Houreld, N. N. A review of photobiomodulation on PI3K/AKT/mTOR in wound healing. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 19, 100215 (2024).

Barolet, A. C., Litvinov, I. V. & Barolet, D. Light-induced nitric oxide release in the skin beyond UVA and blue light: Red & near-infrared wavelengths. Nitric Oxide 117, 16–25 (2021).

Deng, F. et al. Visible light accelerates skin wound healing and alleviates scar formation in mice by adjusting STAT3 signaling. Commun. Biol. 7, 1266 (2024).

Stevens, A. R. et al. Evaluation of transcriptomic changes after photobiomodulation in spinal cord injury. Sci. Rep. 15, 3193 (2025).

Ferlito, M. V. et al. Acute effects of photobiomodulation therapy combined with static magnetic field in C2C12 muscle cells exposed and not exposed to H2O2. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210221 (2024).

Nassisi, M. et al. Short-term efficacy of photobiomodulation in early and intermediate age-related macular degeneration: The PBM4AMD study. Eye 38, 3467–3472 (2024).

Amaroli, A., Clemente Vargas, M. R., Pasquale, C., Raffetto, M. & Ravera, S. Photobiomodulation on isolated mitochondria at 810 nm: First results on the efficiency of the energy conversion process. Sci. Rep. 14, 11060 (2024).

Lima, P. L. V. et al. Photobiomodulation enhancement of cell proliferation at 660 nm does not require cytochrome c oxidase. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 194, 71–75 (2019).

Kashiwagi, S. et al. Photobiomodulation and nitric oxide signaling. Nitric oxide Biol. Chem. 130, 58–68 (2023).

Lipovsky, A., Oron, U., Gedanken, A. & Lubart, R. Low-level visible light (LLVL) irradiation promotes proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. Lasers Med. Sci. 28, 1113–1117 (2013).

Holder, M. J., Milward, M. R., Palin, W. M., Hadis, M. A. & Cooper, P. R. Effects of red light-emitting diode irradiation on dental pulp cells. J. Dent. Res. 91, 961–966 (2012).

Rajendran, N. K., Houreld, N. N. & Abrahamse, H. In vitro wound healing potential of photobiomodulation is possibly mediated by its stimulatory effect on AKT expression in adipose-derived stem cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 6664627 (2021).

de Freitas, L. F. & Hamblin, M. R. Proposed mechanisms of photobiomodulation or low-level light therapy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 22, 7000417 (2016).

Macedo, A. B. et al. Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in dystrophin-deficient muscle cells: Effects on regeneration capacity, inflammation response and oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 10, e0128567 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. TPMS-gyroid scaffold-mediated up-regulation of ITGB1 for enhanced cell adhesion and immune-modulatory osteogenesis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 14, e2404768 (2025).

Faris, P. et al. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) mediates reactive oxygen species-induced Ca2+ entry, mitochondrial dysfunction, and caspase-3/7 activation in primary cultures of metastatic colorectal carcinoma cells. Cell Death Discov. 9, 213 (2023).

Wang, L., Zhang, D. & Schwarz, W. TRPV channels in mast cells as a target for low-level-laser therapy. Cells 3, 662–673 (2014).

Hu, M. et al. PD-1 deficiency disrupts in vivo neural activity in mouse Hippocampus and cortex. Neurobiol. Dis. 213, 107002 (2025).

Wang, Y., Huang, Y. Y., Wang, Y., Lyu, P. & Hamblin, M. R. Photobiomodulation (blue and green light) encourages osteoblastic-differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells: Role of intracellular calcium and light-gated ion channels. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–9 (2016).

Wang, Y., Huang, Y.-Y., Wang, Y., Lyu, P. & Hamblin, M. R. Red (660 nm) or near-infrared (810 nm) photobiomodulation stimulates, while blue (415 nm), green (540 nm) light inhibits proliferation in human adipose-derived stem cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 7781 (2017).

Azarsina, M. et al. Photobiomodulation for stem cell modulation and regenerative medicine -WALT position paper 2025. J. Dent. 159, 105832 (2025).

Perrier, Q. et al. Long-term safety of photobiomodulation exposure to beta cell line and rat islets in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 14, 26874 (2024).

Pasternak-Mnich, K., Kujawa, J., Agier, J. & Kozłowska, E. Impact of photobiomodulation therapy on pro-inflammation functionality of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells – a preliminary study. Sci. Rep. 14, 23111 (2024).

Kao, Y.-C., Lin, G.-Y., Cheng, J.-Y. & Lee, C.-H. Neurite growth induced by red light-caused intracellular reactive oxygen species production through cytochrome c oxidase activation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 241, 112681 (2023).

Hamblin, M. R. Mechanisms and Mitochondrial Redox Signaling in Photobiomodulation. Photochem. Photobiol. 94, 199–212 (2018).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2308200), the Beijing Hospitals Authority High-Level Public Health Technical Talent Development Project (Code: Academic Leader-02–28), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2025LHMS08003), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020KH026), Jinan Municipal Health Commission Science and Technology Plan Project (2024202003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.JB conceptualization; methodology; formal analysis; investigation; writing-original draft; data curation; project administration; funding acquisition. W.XY. funding acquisition. W. ZF. resources. L.XJ. resources. Y.Y. resources. Z.Z. resources. Z.Z.H. Resources. H.T. resources. M.ZJ. resources; funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The human sample isolation procedures were performed following the Guidelines of the National and International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS) and the Guideline for Stem Cell Research & Therapy. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University (Ethics approval No. EFY202500050). Informed consent was obtained from the donor.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, J., Wu, X., Wang, Z. et al. Photobiomodulation stimulates mitochondrial function and cell proliferation in meniscus-derived stem cells (MeSCs) via activation of TRPV1 channel. Sci Rep 15, 43131 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27040-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27040-7