Abstract

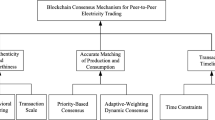

Integration of renewable-energy (RE) sources of energy into local microgrids, decentralised energy markets using blockchain based peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading is gaining more traction due to its ability to enable transparent, autonomous, and secure transactions among distributed energy resources (DERs). Due to the large variety in microgrid topologies and their respective operational constraints, a key challenge to obtaining the most effective trading framework is the choice of blockchain consensus protocol that suits a given microgrid type. Choice of consensus mechanism solely affects the reliability and security of a network. This paper presents a quantitative comprehensive evaluation of various blockchain consensus mechanisms such as Proof-of-Work (PoW), Proof-of-Stake (PoS), Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS), Proof-of-Elapsed-Time (PoET), Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT), Raft, and Tendermint to determine their suitability for P2P energy trading in microgrids. Various metrics such as fault tolerance, energy efficiency, latency, throughput and consensus time were evaluated for multiple consensus mechanisms through simulations. This paper also studies node-scaling impact on the protocols and presents a final decision framework to match the suitable protocol with various microgrid topologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing transformation of traditional utility-driven grids to decentralised microgrids and smart grids, there is an urgent need for a mechanism to manage and optimise the flow of power within microgrids1,2,3 . Peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading is one such mechanism that can manage multidirectional power flow efficiently. It enables users to exchange excess power generated through renewable energy (RE) with peers, thus reducing the reliance on centralised utility grids, and thereby enhancing local microgrid stability by balancing the demand-supply curve4,5,6. Consequently, there has been a significant increase in academic and commercial interest in research related to P2P energy trading. In just 7 years (2017 - 2023), the number of peer-reviewed articles has increased almost eight times, with more than 450 articles indexed in 2023 alone7. Figure 1 depicts the expanding research scenario pertaining to P2P energy trading8. This trend is also being observed by governments and policymakers in many countries like Australia, Germany, Japan and the United States of America9. These developments have also impacted the markets significantly, increasing the investment in this sector. The global microgrid hardware market is valued at 43 billion dollars and is projected to reach 236 billion by 2034 with a cumulative growth rate of up to 18.5%.

Number of journal articles related to P2P energy trading indexed in Scopus8.

However, such trading mechanisms require enhanced resilience against cyberattacks, trust among peers, transparency, and tamper-proof transaction data. Blockchain is one such technology that can bridge all these gaps and facilitate cyber-secure, trusted, transparent, and tamper-resilient P2P trading. Blockchain is a decentralised, distributed, and immutable book of records (or a ledger) into which data can only be added upon consensus among all peers and not modified. Any attempts to maliciously modify the data on a blockchain would require enormous computing power to hack into all the peers on the network simultaneously, since each node has a real-time ledger of all the transactions happening in the network. Because of all the above features, blockchain technology is increasingly being deployed in the energy markets. There has been a recent surge in the energy trading software and services market, which is valued at 7.5 billion dollars and is projected to reach 12.4 billion by 203010, of which blockchain-based pilot projects occupy up to 3.1 billion dollars11. Figure 2 shows the rapid expansion of research in this area.

Literature trend: blockchain-enabled microgrids12.

Operational data from pilot projects highlights the sheer volume of transactions that the future trading mechanisms must hold. TraceX, an energy marketplace run by PowerLedger, cleared almost 1.2 million renewable energy certificate trades in January 2025 alone, which is equal to almost 167 GWh of green energy being transacted in a single month13. This shows that P2P trading ledgers require high scalability and low transaction times. All these factors are controlled by consensus mechanisms, algorithms based on which the distributed peers agree on the next state of the blockchain. There are various consensus protocols that exist and are very different from each other. Selecting the right consensus mechanism is of utmost importance, as it is the backbone of the entire network14. Otherwise, there would be a multitude of issues like throughput bottlenecks, excess latency, cost and energy overhead, weaker security, and poor scalability. For example, a suburban feeder with 250 rooftop solar households can generate up to 100 transactions per second during rapid irradiance swings; a proof of work (PoW) based blockchain can handle only up to 7 transactions per second (TPS), leading to a pile-up of transactions, thus creating a throughput bottleneck. There are other consensus mechanisms that can even handle up to 32000 TPS without any issues in their working, which would be an oversell for a 100 TPS trade.

Similarly, some consensus mechanisms like HotStuff require only 150–250 ms for transaction approval, whereas proof-of-stake (PoS) chains require as high as 2–4 min, leading to excessive latency. Power consumption of certain mechanisms (PoW) is very high, almost as much as 700 kW annually. This further increases the overall power consumption of the network participants, which goes against the main motive for energy trading15. Due to this enormous diversity, there is not a single consensus protocol that is the best for all microgrid topologies. The most optimal consensus algorithm for a given microgrid topology depends on the transaction frequency, regulatory risks, and a viable energy-to-computation ratio. Despite the abundance of literature in this area, there is a significant gap in identifying the best consensus protocol for a given microgrid application. This paper aims to bridge that gap by comparing major consensus protocols using a simulation environment. Various attributes such as throughput, latency, scalability, energy efficiency, security, finality, fault tolerance, and consensus time are tested for consensus protocols, and the best protocol for a given microgrid situation is analyzed. The working of consensus protocols is simulated in Python and then the results are plotted and tabulated to arrive at the best conclusion.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. “Consensus mechanisms” gives a detailed explanation about various consensus protocols considered and their working. “Methodology” refers to the methodology employed to calculate the various parameters discussed above. The simulation details are explained in detail in “Simulation setup”, whereas “Results and analysis” encapsulates the results obtained from the simulations and discusses the final application frameworks for each consensus protocol. “Conclusion and future scope” finally concludes all the findings of the manuscript and gives a direction for future applications of the manuscript.

Consensus mechanisms

As discussed above in “Introduction”, any update to the blockchain requires a consensus among the network participants. A consensus mechanism is a coordination protocol that helps nodes in a network to agree on the next state of the chain16. This mechanism decides whether a new block can be added to the chain and also approves transactions. The peer proposing new blocks into the system is governed by the consensus protocol chosen, which directly affects transaction throughput, energy efficiency of the chain, and chain latency. These mechanisms also control how the agreement among peers pertaining to the block proposal is reached and also verify the legitimacy of the proposal17,18. There are various consensus mechanisms and this paper compares the seven majorly used protocols as shown in Fig. 3

Proof-of-work

Introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 200819, this protocol is the first blockchain consensus protocol and has been used in the Bitcoin blockchain ever since. To mine new blocks in this protocol, the miner must solve a cryptographic puzzle and achieve the target hash set by the chain. This involves extensive computing power to perform multiple trials and achieve the correct solution through which a new block is added. The miner who solves the puzzle faster than the others gets to mine a block. The workflow of block creation in PoW chains is explained below in Algorithm 1

where, Mempool is an assembly of transactions gathered by the miners in a descending order of gas fee assigned. From this pool of transactions, miners usually select the one with the highest gas fee and configure the block header with a parent hash, transaction list for the block, and nonce. The data in the block header is used to make the block hash. A new block is added only if the block hash is lesser than the target hash decided by the chain before hand20. Due to the computing-intensive process involved in block mining, PoW chains require a lot of time to complete one transaction, leading to transaction blockages as the number of nodes increase. This in turn leads to low throughput and high latency of these chains. There is a very high chance of several miners combining their respective computation powers together and making a centralised mining pool which makes the chain vulnerable. PoW chains also consume a lot of power to solve the mining puzzles, thus increasing the carbon footprint of the system.

Proof-of-stake (PoS)

The wasteful computing-intensive process is replaced by economic stakes in PoS blockchains. Block-proposal rights and voting weight in this protocol are directly proportional to stake value of the peer21. Any malicious activity results in slashing, thereby confiscating a significant portion or the entirety of the stake, which results in lower security costs. PoS is used in the Ethereum chain, where the minimum requirement to start mining a new block is 32 ETH. The block creation process in PoS chains are shown below in Fig. 4.

As mentioned above, validators are those users who stake 32 ETH for block creation, and their IDs are stored in Beacon Chain’s validator registry. In this protocol, there is a slot during which one block can be proposed and it lasts for 12 seconds. At the beginning of each slot, PoS uses a random function to select a validator as the block proposer. Along with the proposer, another set of 128 validators are randomly selected to form an attestation committee that is responsible for validating the block proposed by the proposer in that assigned slot. These committee members are selected using a shuffling algorithm. Then, the proposer collects a set of transactions from the Mempool and constructs a new block and signs it using a private key. This new block consists of metadata, transaction details and the state transitions. After signing the block by using a private key, this block is broad-casted to the entire network using a gossip protocol. Once the committee members receive the block, the validity of the block is checked and if valid, these members also sign using their private key and block hash and then broadcast their attestations into the network. These attestations serve as votes and the block is finalised only when at least two-thirds of the entire ETH staked by the validators votes in favor of creating the block in two consecutive epochs (One epoch is equal to 32 slots). Table 1 reveals that PoS addresses most of the limitations that PoW brings to the table while maintaining security through economic incentives rather than computational power. Though both PoW and PoS chains face centralisation risks in the form of miner pools and stake concentration respectively, PoS chains are better suited for power consumption-constrained microgrid environments through deterministic finality.

Delegated PoS (DPoS)

This mechanism was introduced in 2014 by Daniel Larimer and is used in popular blockchain platforms like EOS, Lisk and BitShares. This protocol is more scalable compared to its counterparts, especially in high-frequency and permissioned blockchains. The stakeholders in this protocol vote to elect a fixed number of delegates who are responsible for proposing and validating new blocks into the chain. The voting weight of stakeholders is proportional to their stake in the chain and these voters can vote for multiple delegates. 21 delegates with the most number of votes are elected as active witnesses for the current round of block proposal. Then, these witnesses are ordered into a 21-slot round by a random function, where each slot lasts for up to 0.5 s22.

During these assigned time slots, each witness must sign and publish a block and if they fail to comply, they will not be able to create a block in this round and also face penalties that lead to a loss of their reputation. A block is completely finalised and irreversible only when at least two-thirds of the witnesses have built their blocks on top of it directly, all within a second under normal conditions. This mechanism primarily works on the reputation of the witnesses, and if any malicious user is noted, his reputation tanks and he loses his stake. Algorithm 2 depicts the block creation process in a DPoS blockchain.

Proof-of-elapsed time (PoET)

PoET was introduced first in the Hyperledger Sawtooth blockchain by Intel. This mechanism has a random leader election similar to PoW chains but uses trusted execution environments (TEE) like the software guard extensions (SGX) developed by Intel as leverage instead of computing power. Each validator is assigned a random wait time by this protocol and the validator whose time period expires first gets to create a new block in the chain23. The randomness is generated in the SGX enclave ensuring its security from malicious actors. The workflow of this protocol is depicted in Algorithm 3

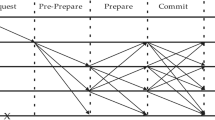

Practical byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT)

This is one of the oldest consensus mechanisms proposed by Castro and Liskov in 1999 for optimising performance in asynchronous systems. This mechanism works on a deterministic consensus mechanism rather than a probabilistic approach. It uses three rounds of message exchanges between nodes and remains functional as long as lesser than one-third of the nodes are faulty24,25. Workflow for block creation in PBFT chains is shown in Algorithm 4.

Raft

Introduced by Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout in 2014, this protocol was designed for implementation in distributed systems. There are three phases in the workflow of this protocol :

-

Leader election : a random node becomes a candidate for a leader election at the start of a new term and becomes a leader if he gets the majority of votes. He remains the leader for the entirety of the term

-

Log replication : the transaction requests are accepted by the leader and then appended to the local log of the leader. Along with this, the leader also broadcasts this entry to all the followers, and the new log entry is committed if the majority of followers have received the entry. The committed entries are then added to the state machine of the followers.

-

Consistency: if any follower lags behind, the leader can update the logs incrementally to help the follower catch up.

Figure 5 represents the workflow in Raft consensus algorithm. As soon as the client makes a request for a new block, the leader of the current term appends the proposed block into their local log of the blockchain and then propagates that appended log to the follower nodes and then waits for the majority of followers to append the new block onto their respective local logs of the chain. If majority of the followers append the block, then the block is considered valid and is appended onto the state machine of the entire blockchain. This message is then carried to the client by the leader. If majority attestation fails, then the leader retries the propagation as long as he is elected. If the leader crashes or loses his leadership before the log is committed onto the chain, then any log entry that is not replicated by the majority of followers is discarded and then a new leader is elected.

Methodology

All the protocols explained above in “Consensus mechanisms” are tested for several metrics like throughput, latency, scalability, energy efficiency, security, and fault tolerance26,27. The performance metrics and the formulation behind them are explained further in this section.

Throughput (transactions per second (TPS))

Throughout quantifies the productivity of a blockchain under steady state. For example, throughput can be thought as the capacity of a toll on a highway—higher the number of lanes (bigger blocksize), more the number of cars passing through (transactions). A blockchain with a low throught is similar to having a single toll booth on a highway and gets blocked if there is a lot of traffic (transaction backlog). For example, a Bitcoin blockchain processes roughly 7 transactions per second and the remaining transactions require a waiting period os almost an hour to get processed with high confidence confirmation. It is defined as the number of transactions processed by the blockchain in a given observation time window, as shown in Eq. (1)

Where \(N_{committed}\) is the number of transactions committed into the blockchain during the time interval \(\Delta t\). Most blockchains, batch up a set of transactions into a single block, and therefore the maximum throughput that can be achieved by a blockchain is defined in Eq. (2), assuming that every block is fully packed with transactions, all the transactions in the block are homogeneous and that there is no block reorganisation, orphaning or failure.

TPS of a particular blockchain is affected by the time taken for blocks and votes to reach all peers and validators, bandwidth of the gossip protocol, mempool saturation, delays in reaching a consensus and the time taken to reach finality28. In P2P energy trading systems, energy offers, bids, and settlements are coded as transactions and require near real-time processing without any delay because any delay would clog the entire network.

Latency

The total time observed by the end user between submitting a transaction and receiving confirmation about its irreversible commitment into the chain is called latency. It is basically the wait time for a transaction akin to waiting for the confirmation receipt from an online shopping transaction. Latency consists of three sub-components, such as :

-

Propagation delay (\(L_{prop}\)) : this is the time taken for a transaction to reach all the peers in the network. This time is fully dependent on the efficiency of the gossip protocol and increases with an increase in the number of nodes in the network.

-

Consensus delay (\(L_{cons}\)): this is the time between receiving a transaction and reaching a consensus on its next state. In different blockchains, it means different things. Like in PoW, it is the time to mine a block, whereas in PoS, it is the time required for a transaction to be selected and confirmed via voting.

-

Confirmation delay (\(L_{conf}\)): the time taken for a transaction to finally process the transaction after the consensus is achieved.

Total latency is defined as shown below in (3)

Several factors influencing the latency of a block include network size, complexity of the protocol, block creation intervals, faulty nodes or forked chains, and leader re-elections in some protocols. In an energy market context, latency determines the speed of bid matching and any delays in this case would lead to a mismatch of prices and load imbalance. For example, consider a household placing a bid to buy extra power at a certain price. If the blockchain takes too long to confirm the trade, by the time the trade is finalised, the available power or the prices might have changed within that time. This can cause mis-priced trades or load imbalances due to shortages of power in some cases. A low latency blockchain can match bids and offers in real-time, so the transactions are confirmed without any noticeable delay.

Scalability

The capacity of a consensus mechanism to maintain its performance and accuracy despite system expansion is known as scalability. It is evaluated by observing performance metrics like TPS, latency, fault tolerance and energy consumption as the scale of the system increases29,30. A system can be scaled in multiple ways as shown in Table 2.

Any scalable protocol must have the per-node resource cost increasing linearly with the scale of the chain. To quantify the scalability of a system, its elasticity is calculated. Elasticity E is defined as the ratio between relative change in TPS and relative change in the number of validators as shown in Eq. (4).

where, \(\Delta TPS\) is the change observed in TPS and \(\Delta n\) is the change in validator count.

Once computed, if

-

\(E \approx 1\): near-linear scalability—throughput increases proportionally with node count

-

\(E < 1\): sublinear scalability—performance gains diminish as nodes are added

-

\(E > 1\): superlinear scalability—rare and typically due to parallelisation or sharding

Scalability of a blockchain protocol is extremely important because P2P trading networks have a huge amount of peers and node count keeps increasing as more people want to participate in the trade. Having good scalability ensures proper functionality of the entire system as the energy ecosystem becomes more distributed and data extensive. Consider a microgrid consisting of 100 homes that generate 10 transactions per second. If the network is expanded to 1000 houses (10x the number of nodes), a truly scalable blockchain should ideally be able to handle 100 TPS (10x the original TPS) with only a proportional increase in the reource per node.

Energy efficiency

The amount of electricity consumed per transaction is called energy efficiency of a protocol. It is defines as shown below in Eq. (5)

where, \(P_{total}\) is the total power consumed by all the consensus nodes, \(\Delta t\) is the time in which the transactions were committed and \(N_{committed}\) is the number of transactions committed into the chain during \(\Delta t\). Energy efficiency of a protocol is especially important when it comes to microgrids because higher power consumption leads to reduced battery life, increased carbon foot print, and increased dependence on the grid thereby counter-impacting the motives of a microgrid. For example, in a microgrid executing 1000 transactions per day, if a blockchain consumes 1kWh power per transaction, then for an entire day, the consumption would be 1000 kWh in just overhead costs and is extremely high (enough to power dozens of homes ).

Finality

Finality of a transaction is reached when it is committed to the block and that decision cannot be reversed. There are two kinds of finality :

-

Probabilistic finality : in protocols that work on a longest chain basis, each additional block added on top of a chain reduces the chance of being overtaken by a competing fork (another alternating chain) vying to enter the network. The probability of reorganisation of the protocol after blocks are added is defined by :

$$\begin{aligned} \Pr [\text {reorg}] \approx \sum _{i=0}^{k} \left( \frac{\beta }{1 - \beta } \right) ^i \left( {\begin{array}{c}k\\ i\end{array}}\right) (1 - \beta )^{k - i} \end{aligned}$$(6)Where k is the number of blocks added to the chain by an honest network, \(\beta\) is the block production power of the attacker, i is the number of blocks mined by the adversary that is usually in the range of 0 to k, and \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}k\\ i\end{array}}\right)\) is a binomial coefficient that represents the number of ways to choose i blocks out of k. The above formula in Eq. 6 estimates the probability that an attacker can create a chain longer than the one made by a honest network and invalidate the previously confirmed transaction. If k is high, then the probability of an attacker catching up to the honest chain is very less. However, if the attacker’s power (\(\beta\)) is high, then the probability of the attacker winning and forking the chain is very high.

-

Deterministic finality: used in Byzantine fault tolerance (BFT)-based protocols, in this method, finality is guaranteed when at least \(2f+1\) validators sign off on the proposed block, where f is the maximum number of faulty validators that can be tolerated by the system. f is calculated as shown in Eq. (7).

$$\begin{aligned} f = \frac{n-1}{3} \end{aligned}$$(7)where n is the total number of validators in the chain. For example, in a chain with 100 validators, the system can tolerate up to 33 faulty validators and for a block to be finalised, at least 67 validators need to sign off.

The differences between probabilistic and deterministic finality are shown in Table 3

In a P2P trading scenario, finality ensures the execution of permanent trades, and prevents roll-back of trades to eliminate double-spending and fraud.

Fault tolerance

Fault tolerance of a protocol depicts how many fault nodes can be tolerated by the network without endangering its accuracy. Any BFT style protocol stems from the fischer-lynch-patterson (FLP) theorem for distributed systems that influences the design of deterministic finality based protocols. FLP theorem states that “In an asynchronous distributed system, no deterministic consensus protocol can guarantee both safety and liveness if even one node may fail”. It basically means that it is impossible to achieve safety, liveness and fault tolerance simultaneously in an asynchronous system. Therefore, all the BFT based protocols assume a partial synchrony where, system is asynchronous, but after some time, can behave synchronously, delivering reliable messages on time. Under this partial synchrony, BFT protocols are bounded by the below mentioned assumption in Eq. (8)

where, n is the total number of validators in a network and f is the maximum number of faulty nodes that can be tolerated by a system. This metric is an important parameter with regards to P2P energy trading because smart meter outages and internet failures are a common risk in microgrids, along with market manipulations and hence a highly fault tolerant system is required in a P2P energy trading scenario.

Consensus time

The time required to achieve consensus on the next state of a blockchain network is known as consensus time and is represented by \(T_{cons}\). Equation (9) quantifies the consensus time for all blockchain networks as mentioned below :

where, R is the number of sequential message rounds required to finalise a block, \(RTT_{net}\) is the median round-trip time for messages between validators, also known as network communication delay, \(C_{crypto}\) is the cumulative cryptographic overhead or the time to generate and verify digital signatures of the validators and \(C_{exec}\) is the time required to process block transactions and to update the next state of the chain. The three main components of the above quantification are

-

\(R\times {RTT}_{net}\) (communication time): every consensus protocol discussed above in section 2 requires sequential messaging rounds to finalise a block where, messages are sent across the network and replies are received from all over the network in each round. The average time taken to complete the above-mentioned process is calculated by \(RTT_{net}\).

-

\(C_{crypto}\) (cryptographic processing time): each validator must sign the messages received digitally and also verify the signatures made by other validators. The time required to complete this entire process is called cryptographic processing time.

-

\(C_{exec}\) (execution time): after achieving consensus, the validators must process the approved transactions inside a block and update the state of the chain and this process must be completed before finalising the block. The time taken to execute this state transition is called execution time.

Faster consensus times are necessary in P2P energy trading due to the immense volume of transactions and any delay would impact prices, load-shifting windows and may lead to a destabilized grid. The above-explained metric were quantitatively calculated for all the protocols mentioned in “Consensus mechanisms” using a simulated environment and then the results were compared for a decision making regarding the suitability of each protocol.

Computational complexity

Computational complexity measures how the resource usage of an algorithm grows with input size and is represented in asymptotic “Big-O” notation. Computational costs of consensus protocols vary vastly. In PoW chains, miners must hash their block data with changing nonce values until they fine a target hash. The expected number of hash attempts grows with the difficulty of the puzzle. In contrast, due to the pseudo-random choice of validators in PoS chains, the complexity varies linearly with number of transactions or validators. For blockchain systems, input can be the number of nodes, or number of transactions or even the difficulty of cryptographic puzzles. Transaction complexity in most blockchain is o(1) because each node verifies the transaction individually. Whereas puzzle complexity exists only in PoW chains where obtaining a target hash is the puzzle to be solved.

Block creation complexity

-

PoW : let the difficulty of ht cryptographic puzzle be D. So the expected work to be done to mine a new block is directly proportional to the difficulty D. PoW chains have a block creation complexity of O(D).

-

PoS : a validator is selected randomly and this process is of O(1) complexity. This validator then signs and broadcasts over the network through a gossip protocol of complexity O(n).

-

DPoS : leader election is of O(1) complexity, but consensus among delegates is of \(O(d^2)\) (d - number of delegates, typically, \(d<<n\)) due to the multiple vote system used for block creation.

-

PoET: the block creation is of O(1) complexity whereas, block broadcasting is of O(n).

-

PBFT: in the pre-prepare broadcast, complexity is O(n), then in prepare and commit where follower nodes broadcast among themselves, the complexity is \(O(\sim n(n-1))\). Totally for the entire block creation, complexity is \(O(n^2)\)

-

Raft: Leader election is of O(n) and the message complexity is the same.

Simulation setup

The main objective of this paper is to compare the metrics mentioned in section 3 systematically for all the consensus mechanism mentioned above. Each protocol was simulated according to the block creation mechanism mentioned in “Consensus mechanisms” and then tested for different metrics.

Simulation framework

Simulations were executed on a workstation with an i7-8700 CPU Intel Core, 16GB RAM and a 512 GBSSD in Ubuntu 20.04 LTS operating system. All the experiments were run in Python 3.11 inside a Jupyter Notebook environment and were executed to reflect validator performance under general conditions. Each protocol was modeled with the characteristics shown in Table 4.

The following assumptions were made in the simulations to provide a realistically controlled environment :

-

Network latency : \(RTT_{net}\) was set between 100 ms and 300 ms, depending on geographical node dispersion and node count in the chain

-

Validator power: all validators were assumed to have equal computational and networking power except in the case of leaders since they perform slightly more work than the other nodes.

-

Block size and transaction rate : block size was fixed at 1 MB and average transaction size was fixed at 250 bytes.

Simulation execution procedure

Figure 6 represents the simulation workflow of the proposed model.

During the initialisation phase, all nodes were assigned their given roles and node IDs, after which a P2P network is created using a random geometric graph that models the interconnection of validators based on network proximity. After this, block creation process begins and is different for each protocol as mentioned in “Consensus mechanisms”. In this step, message exchanges are simulated with assumed RTT delays to show real-time communication costs and are succeeded by sequential voting rounds as per the protocol under study. Transactions are then finalised after completion of the voting process and then different kinds of faults as shown in Table 5 are injected into the system and its ability to maintain safety is tested.

After checking for fault tolerance, the system is then scaled to check the performance of the key metrics mentioned in “Methodology” and the data from each of the steps is collected and logged to generate info-graphic results of the simulation in the following section .

Results and analysis

Data obtained from the simulation was tabulated to be represented info-graphically in this section. Figure 7 shows the performance of consensus protocols when tested for TPS. It is observed that PoET and Raft have higher throughput when compared to other protocols like PoW and PBFT that have some of the lowest throughput rates. DPoS is also observed to have high TPS due to its deterministic scheduling of delegates, rather than a competitive approach, thereby eliminating leader selection delays. Low TPS blockchains like PoW, are heavily limited by their mining difficulty and nonce search operations. In Fig. 8, when observed for latency, PoW was found to have the highest latency due to its probabilistic finality, while PoET has the least latency. Other than PoET, there are several other low-latency blockchains like DPoS, PBFT, in which blocks are finalized immediately after quorum approval and do not need multiple confirmations from the block. Due to this feature, the time taken for a block to be added decreases significantly.

Coming to power consumption, PoW chains were found to consume the most electricity, as shown in Fig. 9 due to their extensive computing-based block creation approach. This leads to a large carbon footprint that is detrimental to the environment and also contradicts the main goal of integrating blockchain into the energy market. There is a drastic difference between PoW chains and the other consensus mechanisms, because unlike PoW chains, the other chains mentioned work on either a stake-based or schedule-based block creation process and require computing power only for minimal tasks like voting or signing on the new block.

The next metric tested is consensus time and it follows the pattern observed in the latency curve as shown in Fig. 10. PoW was found to have the highest consensus time due to network propagation delays and uncertain mining times. The lowest consensus time was found in DPoS due to the fixed set of validators that are elected and given a pre-scheduled order in which blocks will be created, eliminating the need for competition, negotiation or random leader elections.

Table 6 shows the fault tolerance of various consensus mechanisms for a set of 100 nodes in the entire chain. In the case of PoW, the fault tolerance is zero because if an attacker controls more than 50% of the computing power, he can fork the chain, and the attackers cannot be detected or even punished in the chain. Whereas, in PoS and DPoS, multiple stakeholders can collude and control a stake high enough to censor the chain and would be detected only after damage is done. Therefore, in PoW,PoS, and DPoS, even one faulty node cannot be tolerated. However, PBFT can tolerate up to 33 faulty nodes in a chain with 100 nodes, as shown in Eq. (7). Similarly, Tendermint can also tolerate upto 33 faulty nodes since it is built on BFT-style consensus.

The next algorithm Raft, can tolerate only crash faults and can function smoothly only under the condition that \(n \ge 2f+1\). Meaning, the total number of nodes (n) must always be greater than or equal to twice the number of faulty nodes (f) plus 1. From which we can calculate the number of faulty nodes within a total node count of 100. The total number of faulty nodes that can be tolerated by Raft consensus mechanism is shown below in Eq. (10).

Finally, since PoET is based on SGX hardware and does not require the same voting mechanism as PBFT, the fault tolerance is based on SGX failure probability and is said to be 40%. Therefore, in a 100 nodes, the protocol can tolerate up to 40 faulty nodes.

Node scaling results

In the previous section, all the results were verified for a fixed number of nodes and that does not give the complete idea about working of the chain with regards to P2P energy trading or even microgrids because, the nodes keep increasing in a microgrid and these performance metrics need to be tested with node scaling to check their actual performance in a microgrid scenario. In this section, the nodes were exponentially increased and then the performance metrics were tabulated for a real-time analysis. Table 7 encapsulates the node scaling analysis for all the consensus protocols under consideration for smaller intervals of node increments upto 2500 nodes. Figure 11 shows the effect of node scaling on the latency of all protocols. PoW was found to have the highest latency across all network sizes, reflecting its reliance on computing power to solve mining puzzles, thereby making PoW chains unfit for large network scale operations. There was moderate growth observed in PoS due to its slow proposer selection under large-scale node density whereas, DPoS was observed to have an almost flat latency curve due to the prior scheduling of block proposals that is not affected by the node count. However, the same trend was not observed in PBFT which shows a quadratic growth in latency due to the communication complexity present in multi-phase voting rounds. There was an acceptable mild increase observed in PoET, Raft, and Tendermint that is suitable for growing microgrid applications.

Next in Fig. 12, changes in throughput with an increase in the number of nodes is recorded. PoW chains have a constant throughput of almost 6-7 TPS whereas, PoS chains experience an average dip in TPS due to delays in voting. DPoS, Raft and PoET sustained high TPS with very minimal degradation due to the low computational complexity in their block creation mechanisms. Lastly, PBFT and Tendermint collapsed due to the voting overheads that choke block production. Fig. 13 shows how power consumption changes with the number of nodes in a network. PoS, DPoS, and PoET had a well maintained flat power consumption curve due to the minimal cryptographic work for block production whereas, PoW had the highest power consumption unaffected by node number due to high dependence on mining and computing power that does not change with changes in number of nodes. Power consumption in PBFT chains exhibits a quadratic growth due to their three-phase messaging protocol that requires \(3n^2\) messages per a single consensus round during which all nodes have to remain active to validate messages from all other nodes and cannot get into idle power saving modes. In Raft chains, power consumption rises linearly due to the periodic heartbeat messages sent by the leader to all other follower nodes and the broadcasting of log replication entries.

The effect of node scaling on consensus time is observed in Fig. 14. DPoS is observed to have a stable consensus time is approximately 1.5 to 2 seconds despite node scaling whereas PoW has a very high consensus time and PoS is found to have a steady expansion as the node count increases due to increasing coordination delays between validators. PBFT has a sharp rise in consensus time due to delayed message synchronisation in high node-density networks. Tendermint and PoET grew slightly and Raft maintained sub-linear scaling.

Figure 15 shows the changes in fault tolerance with respect to increasing network volume, and it is seen that PoW, PoS, and DPoS had zero fault tolerance despite increases in node volume, whereas Raft, PBFT, and Tendermint scaled linearly due to their protocol design explained above. Lastly, PoET is found to have a moderate increase due to its reliance on trusted SGX hardware. Table 8 gives the statistics for various performance metrics for consensus protocols scaled upto 10000 nodes.

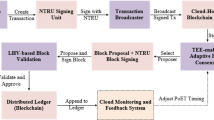

Decision framework for microgrids

Blockchain based P2P energy trading in microgrid16.

In blockchain-based P2P energy trading systems as shown in Fig. 16, microgrids play a vital role and act as the foundation where power exchange, load balancing, multidirectional power flow, and distributed control take place. These microgrids are heterogeneous in terms of control, architecture, scale, consumption patterns, and proportion of energy derived from DERs. Therefore, the decision to select a suitable consensus protocol must be derived by considering all the above-mentioned parameters. Table 9 encapsulates all the results obtained and recommends a suitable microgrid framework for each of these protocols based on their performance metrics and attributes. Government or audit-critical grids are generally centralised inter-microgrid or large-scale microgrid systems that are operated by government agencies or utility-scale energy distributors with a modest DER penetration and a very large node count ranging between 1000 and 10,000 participants with a daily energy demand of over several thousand kilowatt-hours. In these grids, transparency, immutability, legal compliance, and forensic verifiability are more important than operational speed and power consumption. Therefore, PoW is the most suitable in this scenario due to its high tamper resistance, and trusted finality despite its high power consumption. Immutability and fork resilience in PoW are of utmost importance for government-backed subsidies and forensic billing.

In urban and semi-urban areas, smart meters are rapidly being deployed to monitor consumer electricity usage and to support dynamic pricing mechanisms. These systems generally comprise of 200–1000 nodes and a moderate DER penetration of up to 30–60 % and have a distributed control model because smart meters function and report individually but are connected and synchronised to the grid level aggregators occasionally. The power demand in these microgrids is usually between 2000 and 10,000 kWh/day. In such settings, PoS is the most useful because it provides an excellent balance of security, energy efficiency, and stability. Smart meters often operate with consistent up-time and reasonable internet connectivity, and in these conditions, PoS works well while keeping energy costs minimal. The moderate throughput of PoS chains is sufficient for the 15-minute interval or even hourly transactions, and its stake-based validation ensures robustness in semi-trusted distributed systems like large smart-meter meshes. DPoS has very high throughput and low latency despite node scaling but the power in this chain is held by the very few elected validators and is suitable for federated regional energy co-operatives (co-ops) that handle over 1000-5000 participants. These co-ops are gaining more traction due to their ability to manage bulk DER generation across neighborhoods and districts. They can handle a very high DER penetration (40–70%) and usually have a federated control mechanism with a power consumption of up to 50,000 kWh. The federated nature of the system justifies the centralised consensus in DPoS systems, thereby allowing for efficient performance without sacrificing democratic control.

Next, PBFT is suitable for small gated communities with less than 50 nodes because of its poor scalability and strong fault tolerance. In gated community-based networks, participants are stable and security against malicious nodes is of critical importance and therefore PBFT is the best-suited protocol in this case. Raft and Tendermint have a combination of excellent throughput, very low consensus time and very high energy efficiency and therefore are best for medium-sized distributed energy resource (DER) clusters that require operational efficiency between semi-trusted participants. Lastly, PoET is suited for low-power rural IoT-enabled microgrids due to its dependence on trusted hardware, low latency, high energy efficiency and a moderate throughput. The mapping to protocols with recommended microgrid types balances the trade-offs between electricity costs, throughput, number of nodes/participants, and trust assumptions, thereby ensuring that a particular blockchain complements the operational dynamics of an energy trading mechanism suited for its performance.

All blockchains use digital signatures and hash-chained ledgers to prevent data tampering and repudiation. Public blockchains like PoW, PoS, and DPoS have their transactions broadcast to every node in the network and the entire ledger of transactions is visible to everyone. Participant identities are pseudonymous and therefore no real names or addresses are shown. But the transaction details like amount of energy traded, money exchanged and timestamps are clearly visible. Data integrity is protected by cryptographic signatures and the consensus algorithm (miners or validators must solve PoW puzzles or stake coins), but confidentiality is not provided: any on-chain data can be read by all network participants. In contrast, private blockchains like PBFT and Raft operate among a known set of participants who are authenticated via certificates that are issued by a trusted authority and the network communication is secured by transport layer security (TLS).

Conclusion and future scope

A comprehensive and quantitative analysis of the performance of various consensus protocols under various node conditions has been done successfully in this manuscript. The consensus protocols, namely, PoW, PoS, DPoS, PBFT, Raft, Tendermint and PoET have been considered for this study and were tested for parameters like latency, scalability, fault tolerance, power consumption, consensus time and TPS to assess their suitability for different microgrid operations. It is found through the results that there is one best consensus mechanism for all microgrid types. The performances of these protocols differ, and each of these protocols is suited for different microgrid types due to their unique algorithms. Protocols like PBFT and Tendermint that offer deterministic finality and robust fault tolerance are more preferable in small to medium microgrid ecosystems whereas, protocols like DPoS and Raft have exceptional scalability and low consensus times and are more suitable in large-scale federated energy networks and DER clusters. This study also helps map each consensus protocol to their appropriate microgrid type to enhance system performance and also to provide a clear framework for researchers and policymakers. While the proposed work captures relative trends, it does not reflect the real-world heterogenous network delays in microgrids, complex market mechanisms and also the unpredictble power generation from RE.Further research can be done in the area of combining two or more different protocols to further enhance the chances of obtaining a better fault resilient, secure, and energy efficient blockchain.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chekired, D. A. E., Dhaou, S., Khoukhi, L. & Mouftah, H. T. Dynamic pricing model for EV charging-discharging service based on cloud computing scheduling. In 2017 13th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC). 1010–1015. https://doi.org/10.1109/IWCMC.2017.7986424 (2017).

Alghamdi, T. G., Said, D. & Mouftah, H. T. Decentralized energy storage system for EVs charging and discharging in smart cities context. In ICC 2019 - 2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC). 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8761138 (2019).

Khabbouchi, I., Said, D., Oukaira, A., Mellal, I. & Khoukhi, L. Machine learning and game-theoretic model for advanced wind energy management protocol (AWEMP). Energies 16, 2179. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16052179 (2023).

Aloqaily, O. I., Al-Anbagi, I., Said, D. & Mouftah, H. T. Flexible charging and discharging algorithm for electric vehicles in smart grid environment. In 2016 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC). 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/WCNC.2016.7565123 (2016).

Said, D. & Elloumi, M. A new false data injection detection protocol based machine learning for p2p energy transaction between CEVs. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Electrical Sciences and Technologies in Maghreb (CISTEM). 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISTEM55808.2022.10044067 (2022).

Alghamdi, T. G., Said, D. & Mouftah, H. T. Decentralized game-theoretic approach for D-EVSE based on renewable energy in smart cities. In ICC 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC). 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC40277.2020.9148718 (2020).

Lampropoulos, G. Blockchain in smart grids: A bibliometric analysis and scientific mapping study. J 7, 19–47 (2024).

Scopus Database. Analytics on peer-to-peer energy trading research publications. https://www.scopus.com/term/analyzer.uri?sort=plf-f&src=s &sid=bcfa1c1b2362dddb8f4e12201327f60a &sot=a &sdt=a &sl=42 &s=TITLE-ABS-KEY(peer+to+peer+energy+trading) &origin=resultslist &count=10 &analyzeResults=Analyze+results (2025). Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Peer-to-peer electricity trading: Innovation landscape brief. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2020/Jul/IRENA_Peer-to-peer_electricity_trading_2020.pdf (2020). Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

Precedence Research. Microgrid market size to hit around USD 133.61 billion by 2032. https://www.precedenceresearch.com/microgrid-market (2025). Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

GlobeNewswire. Microgrid markets forecast to exceed us\$163 billion in total revenues by 2033: Industry competition intelligence featuring ABB, Siemens, GE, Eaton, Exelon, Honeywell, Schneider Electric. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/03/25/3048500/28124/en/ (2025). Accessed 29 April 2025.

Scopus Database. Analytics on peer-to-peer energy trading using blockchain research publications. https://www.scopus.com/term/analyzer.uri?sort=plf-f&src=s &sid=bcfa1c1b2362dddb8f4e12201327f60a &sot=a &sdt=a &sl=75 &s=TITLE-ABS-KEY(peer+AND+to+AND+peer+AND+energy+AND+trading+using+blockchain) &origin=resultslist &count=10 &analyzeResults=Analyze+results (2025). Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

Powerledger. Revolutionizing renewable energy certification. https://powerledger.io/media/revolutionizing-renewable-energy-certification-how-technology-is-shaping-the-26-5-billion-rec-market/ (2025). Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

Xiao, Y., Zhang, N., Lou, W. & Hou, Y. T. A survey of distributed consensus protocols for blockchain networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 22, 1432–1465. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2020.2969706 (2020).

Naz, S. & Lee, S. U.-J. Why the new consensus mechanism is needed in blockchain technology? In 2020 Second International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA). 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1109/BCCA50787.2020.9274461 (2020).

Bhavana, G. et al. Applications of blockchain technology in peer-to-peer energy markets and green hydrogen supply chains: a topical review. Sci. Rep. 14, 21954 (2024).

Alzoubi, Y. I. & Mishra, A. Blockchain consensus mechanisms comparison in fog computing: A systematic review. ICT Exp. 10, 342–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icte.2024.02.008 (2024).

Lashkari, B. & Musilek, P. A comprehensive review of blockchain consensus mechanisms. IEEE Access 9, 43620–43652 (2021).

Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin Whitepaper. Vol. 9. 15. https://bitcoin. org/bitcoin. pdf. Accessed 17 Jul 2019 (2008).

Buterin, V. et al. Ethereum white paper. GitHub Reposit. 1, 5–7 (2013).

Pavloff, U., Amoussou-Guenou, Y. & Tucci-Piergiovanni, S. Incentive compatibility of ethereum’s pos consensus protocol. In 28th International Conference on Principles of Distributed Systems (OPODIS 2024). Vol. 7–1 (Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, 2025).

Saad, S. M. S. & Radzi, R. Z. R. M. Comparative review of the blockchain consensus algorithm between proof of stake (POS) and delegated proof of stake (DPOS). Int. J. Innov. Comput. 10 (2020).

Bowman, M., Das, D., Mandal, A. & Montgomery, H. On elapsed time consensus protocols. In Progress in Cryptology–INDOCRYPT 2021: 22nd International Conference on Cryptology in India, Jaipur, India, December 12–15, 2021, Proceedings 22. 559–583 (Springer, 2021).

Meshcheryakov, Y., Melman, A., Evsutin, O., Morozov, V. & Koucheryavy, Y. On performance of PBFT blockchain consensus algorithm for IOT-applications with constrained devices. IEEE Access 9, 80559–80570 (2021).

Yadav, A. K. et al. A comparative study on consensus mechanism with security threats and future scopes: Blockchain. Comput. Commun. 201, 102–115 (2023).

Auhl, Z., Chilamkurti, N., Alhadad, R. & Heyne, W. A comparative study of consensus mechanisms in blockchain for IOT networks. Electronics 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11172694 (2022).

Bamakan, S. M. H., Motavali, A. & Babaei Bondarti, A. A survey of blockchain consensus algorithms performance evaluation criteria. Expert Syst. Appl. 154, 113385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113385 (2020).

Tangem. Measuring blockchain speeds: What is TPS? https://tangem.com/en/blog/post/measuring-blockchain-speeds-what-is-tps/ (2024). Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

Croman, K. et al. On scaling decentralized blockchains (a position paper) (2016).

Chen, B. et al. A Comprehensive Survey of Blockchain Scalability: Shaping Inner-chain and Inter-chain Perspectives. Vol. 2409. 02968 (2024).

Gaži, P. Proof of Stake, 1–3 (Springer, 2019).

Li, W., Deng, X., Liu, J., Yu, Z. & Lou, X. Delegated proof of stake consensus mechanism based on community discovery and credit incentive. Entropy 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/e25091320 (2023).

Castro, M. & Liskov, B. Practical byzantine fault tolerance. In Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI). 173–186 (USENIX Association, 1999).

Ongaro, D. & Ousterhout, J. In search of an understandable consensus algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2014 USENIX Annual Technical Conference. 305–320 (2014).

Buchman, E., Kwon, J. & Milosevic, Z. The latest gossip on bft consensus. In Technical Report. CoRR. arXiv:1807.04938 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. On security analysis of proof-of-elapsed-time (poet). In Stabilization, Safety, and Security of Distributed Systems (Spirakis, P. & Tsigas, P. Eds.). 282–297 (Springer, 2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi (Amma), Chancellor, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, for her inspiration and for providing financial support for the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study, conception, and design. all authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Authors transfer to Springer the publication rights and warrant that our contribution is original.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhavana, G.B., Anand, R., Ramprabhakar, J. et al. Comparative evaluation and simulation of blockchain consensus mechanisms for secure and scalable peer to peer energy trading in microgrids. Sci Rep 15, 43546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27431-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27431-w