Abstract

Climate polarization threatens the food production stabilization and economic development worldwide. As a major agricultural producer, China faces increasing risks to its food security. This study examines the effects of accumulated temperature and precipitation anomaly level on food production resilience, with crop diversity potentially playing a moderating role. To this end, it uses fixed-effects and moderating-effects models based on official statistics from 31 Chinese administrative regions (2010–2022). First, China’s overall resilience in food production has shown an upward trend, fluctuating from 0.376 in 2010 to 0.435 in 2022. Second, accumulated temperature has a suppressing effect on food production resilience at the 5% significance level, while precipitation anomalies have a similar effect at the 10% significance level. This inhibitory effect is most pronounced in major food-producing areas, while it is less severe in major food-consuming areas and in regions with production-consumption balanced areas. Third, crop diversity has an important moderating role, mitigating the negative impact of precipitation anomalies on food production resilience, statistically significant at 10% level; conversely, its role in moderating accumulated temperature is insignificant. To cope with climate shocks and safeguard food production security, the study proposes policy recommendations in three areas: building a climate-smart agricultural system, optimizing the application of crop diversity, and implementing targeted zoning strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food and food security are fundamental to people’s well-being, national security, and sustainable development of society and the economy. The escalating intensity and growing frequency of extreme weather events triggered by global warming pose significant risks to food production worldwide1. Extreme weather conditions not only disrupt agricultural production in directly affected regions, but also trigger fluctuations in agricultural exports and ripple effects on food prices in other areas2 through supply–demand transmission mechanisms within global supply chains3. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 indicates that between 713 and 757 million people were undernourished in 2023. In addition, over 2.33 billion people experienced moderate or severe food insecurity, with more than 864 million people facing severe levels of food insecurity4. Meeting the growing nutritional needs of humanity amid resource scarcity and climate extremes is one of the greatest humanitarian challenges in the twenty-first century5.

Developing countries are substantially vulnerable to climate shocks because they rely on agriculture and have limited access to capital, technology, and infrastructure6. As the largest developing country, China faces significant challenges in food security due to its large population and high food demand. Despite steady growth in food production, rapid urbanization and frequent natural disasters continue to threaten food security 7. Therefore, studying China’s food production resilience (FPR) is essential for promoting supply-side structural reform and stabilizing the grain supply–demand balance.

Research on climate change primarily focuses on its impacts on the ecological environment, social life, and agricultural production. Climate change has altered regional evaporation and precipitation patterns, accelerating the degradation of plateau glaciers and permafrost8. Global warming also exhibits clear regional differences, with temperatures increasing two to three times faster than the global average in Eurasia and 3 to 4 times faster in the Arctic and Antarctic Peninsula9. In terms of social impacts, climate change has increased morbidity and mortality from infectious and respiratory diseases, while exacerbating socio-political tensions and conflicts10. In agriculture, while yields may increase in certain regions, declining crop quality could outweigh these gains, ultimately reducing farmers’ incomes11.

On climate change and food production, most research has focused on food access, utilization efficiency, and food security, with relatively little attention to food production resilience. Research indicates that rising temperatures and water stress decrease agricultural productivity by increasing food prices and threatening agricultural livelihoods12. Food production is highly sensitive to climatic anomalies, with droughts or extreme temperatures significantly reducing output. Excessively high temperatures and diurnal temperature variation indices have a significant and negative correlation with corn and soybean yields13. Global investigations show that grain yields are declining in about half of all countries under current climate trends14. Moreover, climate change intensifies the disruption caused by non-climate disasters to global food production systems15, generating complex chain reactions and opening up new avenues for research.

The aforementioned research provides a rich theoretical foundation for exploring the role of climate anomalies in food production resilience, but it still has notable gaps and limitations. (1) Existing literature has primarily investigated the resistance of food production to disasters, with limited research on the sustainability and regenerative capacity of food production. (2) Current research has primarily concentrated on the direct impacts of climatic anomalies on the food system, with little attention paid to how crop diversity plays a regulatory role. To address these gaps, this paper develops an evaluation system for food production resilience indicators. By introducing crop diversity as a moderating variable, it constructs a research framework that examines its role in shaping the impacts of climate change on food production resilience. In this way, this study provides significant contributions in the following three key aspects: (1) It examines the impact of climate change on food production resilience through two dimensions—annual average accumulated temperature and precipitation anomaly level—thus overcoming the limitations of single climate indicators and offering deeper insights into the mechanism of composite climate effects on food production resilience; (2) It analyzes the moderating role of crop diversity in the process of climate change influencing food production resilience, enriching the research perspective; (3) It examines regional variations in climate change impacts on food production resilience and the differing moderating effects of crop diversity, providing both theoretical foundations and empirical evidence to support differentiated approaches to resilience governance.

Theoretical framework and proposed hypotheses

Conceptual definition of food production resilience

“Resilience” originally stems from materials physics, describing a material’s ability to return to its original state after external stress. In the 1970s, ecologist Holling extended the concept to ecology, defining resilience as an ecosystem’s capacity to recover to a stable state and maintain normal functioning after disturbances16. By the early twenty-first century, resilience theory integrated human systems with ecological dynamics, achieving expansion and reinforcement within sociology and economics. It is generally defined as a system’s capacity to withstand disturbances, undergo reorganization, and maintain its essential functions, structure, identity, and feedback loops while navigating change, thereby achieving dynamic objectives17. In economics, resilience has been studied in terms of a system’s capacity to resist recessions, adapt to disruptions, and recover from external shocks such as financial crises, geopolitical conflicts, or public health events, with analyses spanning urban18, regional19, and macroeconomic scales. In agriculture, resilience describes the capacity of food systems to withstand and respond to disruptions in production, supply, and distribution, encompassing three dimensions: socioeconomic, biophysical, and production diversity20. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations defines food production resilience as the food production system’s ability to ensure that all people have access to adequate, safe, and nutritious food during disasters and to fulfill the livelihoods of food system participants in agriculture21. Scholars have decomposed resilience into dimensions of resistance, adaptability, and innovation22, and examined how the food system relies on different factors such as urbanization rate23, digital villages construction, and agricultural insurance coverage24.

How climatic anomalies affect food production resilience

In its Sixth Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases have contributed significantly to climate warming. The surface temperature worldwide during 2011–2020 was 1.1℃ above that during 1850–190025. Climate stress has wide-ranging and profound impacts on both the environment and human society, with particularly notable effects on agricultural production.

Firstly, climate change is reducing both the quantity and quality of food production, while effective irrigation resources continue to dwindle, thereby weakening the food systems’ resistance to external environmental pressures. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events, like torrential rain and heat waves, has severely disrupted agricultural environments and substantially decreased food output26. Research predicts that by the end of the century, nearly all major staple crops, except for rice, are at risk of yield reductions due to extreme climate change. Under high-emission scenarios, projected declines range within 12–27.8% for maize, 13.5–28.2% for wheat, and 22.4–35.6% for soybean27. Rising carbon dioxide emissions, higher temperatures, and increased light intensity have led to shorter crop growth cycles, reduced accumulation of sugars and nutrients, and consequently, low crop quality28. For example, as carbon dioxide concentrations increase, the protein content of wheat grains may decrease by 8.6%29. Climate-driven depletion of alpine snowpacks will reshape downstream hydrological systems, transforming both supply–demand dynamics and seasonal availability of glacial freshwater sources30. Based on statistical modeling, Pinke found that droughts and heat waves, which reduce effective freshwater irrigation resources in Eastern Europe, are degrading soils. Each 1℃ increase in global average temperature will result in a 4.1–6.4% decrease in European wheat production31.

Secondly, climate change has reduced the sustainability of food systems, weakening their adaptability to external environmental changes. Evidence shows that regional climate events have become more pronounced, with erratic rainfall, prolonged droughts, and severe flooding, all of which negatively impact food production32. Less developed regions are often more vulnerable to climate disasters. Farmers in these areas typically have lower incomes, limited knowledge, and restricted capacity to apply technologies that mitigate agricultural climate risks33. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa, highly dependent on agriculture, exhibits low utilization of modern irrigation technologies and is particularly affected by high temperatures and reduced rainfall under global warming34. Climate change increases atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, temperature, and humidity, which exacerbates pest and disease outbreaks in food crops. In order to increase food production, farmers often respond by increasing the application of agricultural chemicals, including pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides35. Excessive use of agrochemicals can result in eutrophication, decreased crop output, soil salinization, and rising soil pH36, creating a vicious cycle of agricultural pollution and declining productivity.

Thirdly, climate change has led to increased fixed asset investment in agriculture and insufficient total power of agricultural machinery, thereby weakening the food system’s regenerative capacity. According to the Cobb–Douglas production function, food output depends on a multifactor combination of land, labor, and capital37. In response to yield losses caused by climate change, farmers often increase inputs of labor, capital, materials, and technology. Agricultural development requires infrastructure, encompassing both tangible assets such as roads, irrigation systems, machinery, and repair facilities, as well as intangible components like credit systems, insurance investments, and cooperatives38. However, climate extremes can damage key agricultural infrastructure and raise storage and transportation costs39. The interaction of climatic factors and soil conditions can lead to waterlogging, which reduces soil permeability, impairs drainage, increases surface runoff and erosion, and heightens susceptibility to compaction. Consequently, root depth is reduced, adversely affecting plant growth. Excess moisture also means that machines can sink into the soil and wheels can slip, reducing the efficiency of agricultural machinery use per unit area40.

Given this analysis, the research proposes the following hypothesis:

H1:

Climate change has a dampening effect on food production resilience.

Moderating effects of crop diversity

To mitigate the impacts of climate change, growers are adapting production strategies to new conditions. Increasing crop diversity is one economically viable adaptation approach, which offers flexible forms and scales, enabling farmers to both withstand disasters and enhance economic returns41. Crop diversity creates a selection effect: the more species present in an ecosystem, the greater the likelihood that at least one will tolerate specific climatic conditions42. Enhancing diversity is crucial for stabilizing food security, as practices such as intercropping and crop rotation can improve overall productivity. Utilizing ecological niche differentiation among crops within the same spatial scenario43 can improve resource use efficiency and promote sustainable agricultural development. Additionally, crop diversity has been indicated to enhance the agricultural output capacity and yield consistency of oilseed cropping systems across diverse settings44.

This analysis introduces the following hypothesis:

H2: Crop diversity mitigates the adverse effects of climate disruption on food production resilience.

Climatic factors such as elevated carbon dioxide levels, rising temperatures, and altered precipitation patterns have expanded the geographical range of pests, increased overwintering survival and generation numbers, and reduced the effectiveness of biological control measures45. Simultaneously, climate change directly affects soil microbial systems; higher temperatures lead to the depletion of soil organic carbon, shifts in bacterial community composition, and declines in fungal abundance. Thawing permafrost may also release novel viruses46. Crop rotation and increased crop diversity reduce pathogen abundance and transmission through the host-absence effect and ecological regulation by antagonistic organisms arising from the decomposition of diverse plant residues within the soil 47. Additionally, higher crop diversity enhances inter-root carbon inputs to the soil microbial community, supporting microbial growth that benefits crop development48. Accordingly, hypothesis H2a is proposed:

H2a: Crop diversity mitigates the adverse impact of rising accumulated temperature on food production resilience.

Reduced precipitation lowers soil moisture, inhibiting plant and microbial activity49, while excessive rainfall during critical crop growth stages disrupts pollination and causes root oxygen deprivation and decay, ultimately reducing yields. Crop diversity mitigates these impacts by enhancing soil quality and microbial activation50. Crop diversity also optimizes agricultural production choices. Crops with diverse root systems of different depths can effectively increase soil voids and precipitation infiltration rates, which can effectively cope with extreme precipitation conditions51. Combining high- and low-level shading systems can protect crops from abnormal precipitation, as the upper canopy reduces soil evaporation and improves soil moisture infiltration41.

Accordingly, Hypothesis H2b is proposed:

H2b: Crop diversity attenuates the detrimental influence of precipitation anomalies on food production resilience.

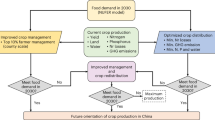

Building on these assumptions, this paper analyzes the disruptive effects of climate change on food production resilience across three aspects: resistance, adaptability, and regenerative capacity. It further examines the moderating role of crop diversity under two climate stressors: accumulated temperature and precipitation anomalies. The study integrates the adverse impacts of climate change with the regulatory effects of crop diversity to assess their combined influence on food production resilience. Figure 1 displays the overall framework.

Research design

Data sources

This research analyzes the impact of climate change on FPR based on panel data from 31 provincial-level administrative regions in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) between 2010 and 2022. Data primarily originate from the Statistical Yearbook of China (National Bureau of Statistics), the FAO database, the National Meteorological Science Data Sharing Service Platform, and local statistical sources. For individual missing data points, interpolation methods were employed to estimate. Additionally, the 31 provinces were categorized into major food-producing areas, major food-consuming areas, and production-consumption balanced areas based on The Outline of Medium-and Long-Term Plan for National Food Security (2008–2020). Specifically, the major food-producing areas encompass 13 provinces: Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Shandong, Anhui, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Henan, Hunan, Sichuan, and Hubei. The major food-consuming areas include 7 provinces: Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Zhejiang, Hainan, Guangdong, and Fujian. The production-consumption balanced areas comprise 11 provinces: Shanxi, Guangxi, Chongqing, Yunnan, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Tibet, Ningxia, and Xinjiang.

Selection and definition of variables

Dependent variable

Food production resilience (FPR) is the dependent variable. Based on the previous studies, this paper defines this variable as the capacity of food production systems to maintain stability and resist various internal and external shocks. To measure FPR, the FAO uses the Resilience Index Measurement and Analysis (RIMA) methodology, which calculates the Food System Resilience Index (FSRI) via factor analysis and a Multi-Indicator Multi-Factor (MIMIC) model, covering production, processing, and markets52. Academically, FPR is often assessed through multidimensional indicator systems, using weighting methods such as entropy, principal component analysis, or analytic hierarchy process to calculate composite indices. Some studies employ the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) framework, evaluating resilience through resistance, recovery, and transformation capacities53. This paper adopts a similar comprehensive approach, dividing FPR into three dimensions: resistance, adaptability, and regenerative capacity. Meanwhile, on relevant research by Zhang Mingdou and Hui Mingwei54, the resistance is categorized into 2 dimensions of production foundation and production capacity. Adaptability is divided into two dimensions: sustainability and recoverability. Regenerative capacity is segmented into 2 dimensions: diverse collaboration and technological progress. A comprehensive evaluation framework for FPR was developed, consisting of three primary indicators, six secondary indicators, and 18 tertiary indicators. Table 1 represents the details.

Independent variable

The independent variables are the mean annual accumulated temperature (AT) and precipitation anomaly magnitude (measured by the absolute value of the standardized precipitation index, abbreviated as |SPI|). Most crops can only grow stably when the average daily temperature is above 10℃. The accumulated temperature refers to the active accumulated temperature, i.e., the sum of temperatures obtained by accumulating the duration of daily average temperature ≥ 10℃ in a year. For the calculation, daily temperature data from major meteorological stations across all provinces were used to determine monthly accumulated temperatures, from which the annual average accumulated temperature was derived for each province55. |SPI| is a kind of climate drought monitoring indicator based on probability statistics. It centers on quantifying the extent to which precipitation deviates from a long-term climate benchmark over a given time period through Gamma distribution fitting and normal normalization. The formulae are as follows:

Assuming that the precipitation \(x\) obeys a Gamma distribution, Eq. (1) represents its probability density function.

where α is the shape parameter, controlling for deviations from the distribution, β shows the scale parameter, reflecting the degree of precipitation variability, \(x\) denotes the annual precipitation, and \(\Gamma \left( \alpha \right)\) signifies the Gamma function.

Equations (2) and (3) represent the calculation of parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) using the method of maximum likelihood estimator (MLE):

where \(x\) is the annual precipitation, \(\overline{x}\) denotes the precipitation time series mean, and \(n\) signifies the time series length.

Equation (4) represents the cumulative probability function.

Given that the Gamma function requires the independent variable to be a positive real number, the actual precipitation data may be zero-valued, according to Eq. (5).

where q is the probability of the occurrence of the value 0 in the precipitation series. Equation (6) shows the Gaussian function used to convert the cumulative probability to a standard normal distribution variable Z (i.e., the SPI value)

where \(\Phi^{ - 1}\) serves as the inverse function of the standard normal distribution. Equation (7) indicates the calculation process using the approximate solution method:

When \(H\left( x \right)\)≤0.5, let \(t = \sqrt {\ln \left( {1/H\left( x \right)^{2} } \right)}\), then

When \(H\left( x \right)\) > 0.5, substituting \(1 - H\left( x \right)\) into Eq. (7) gives the opposite number. The constant values are as follows:

This paper employs |SPI| to reflect the level of precipitation irregularity. Higher absolute values indicate a greater degree of precipitation anomaly. In concrete terms, |SPI| between \(\left[ {0.0,1.0} \right]\) indicates slight abnormality, \(\left[ {1.0,1.5} \right]\) shows moderate abnormality, \(\left[ {1.5,2.0} \right]\) presents severe abnormality, and \(\left| {SPI} \right| > 2.0\) denotes extreme abnormality56.

Moderating variables

Crop diversity is the moderating variable. This investigation utilizes the Simpson Index of Diversity (SID)6 to measure the level of crop diversity in a given region. By quantifying the probability of randomly selecting two individuals from a sample to belong to the same species, a numerical value can be obtained to describe the diversity level of the sample. Specifically, this can be expressed in the formula: \(SID = 1 - \sum {S_{i} }^{2}\), where is the share of crop i in the total planted area. SID ranges between \(\left[ {0,1} \right]\), where a higher index represents a higher diversity of crops and vice versa. The SID focuses diversity assessment more on the contribution of dominant species by weighting species abundance (i.e., crop area share). Within agricultural ecosystems, this approach sensitively captures shifts in the distribution of major crops, providing an accurate reflection of regional crop diversity. This study focused on diversity indices for eight major crops: rice, wheat, maize, sorghum, legumes (soybeans), and tubers (potatoes, sweet potatoes, and cassava).

Control variables

Building upon existing research57, the paper adds additional variables effective in the FPR, including (1) the level of agricultural trade openness, calculated through the proportion of total agricultural exports and imports to total agricultural output; (2) rural electric power facilities, expressed by rural electricity consumption; (3) the proportion of the non-agricultural economy, calculated as the sum of the value added by the secondary and tertiary industries, divided by the regional gross domestic product; (4) the urbanization level, defined by the ratio of the urban resident population to the total; (5) crop cultivation structure, expressed as the ratio of land planted with food crops to that planted with non-food crops; (6) the urban–rural income disparity, qualified by the ratio of urban national income per capita to rural national income. Table 2 presents the description of the variables.

Model construction

FPR index measurement

Entropy value method

-

(1)

Normalization: Eq. (8) represents the positive correlation indicators.

$$Z_{ij} = {{(\mathop x\nolimits_{ij} - \mathop x\nolimits_{\min } )} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{(\mathop x\nolimits_{ij} - \mathop x\nolimits_{\min } )} {(\mathop x\nolimits_{\max } - \mathop x\nolimits_{\min } )}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {(\mathop x\nolimits_{\max } - \mathop x\nolimits_{\min } )}}$$(8)

Equation (9) shows the negative correlation indicators.

-

(2)

Equation (10) presents the calculation of indicator weights.

$$P_{ij} = Z_{ij} /\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{m} {Z_{ij} }$$(10) -

(3)

Eq. (11) indicates the calculation of the metric entropy value.

$$e_{j} = - k\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{m} {P_{ij} } \ln P_{ij}$$(11)

Equation (12) provides the redundancy of information entropy.

-

(4)

Eq. (13) shows the calculation of the indicator weights.

$$W_{j} = d_{j} /\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{n} {d_{j} }$$(13)

Game theory combinatorial empowerment approach

Game theory-based weighting integrates indicator weights derived from multiple methods to determine optimal values. This study used the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and entropy method to measure subjective and objective weights, respectively, which were then optimized via game theory to obtain final indicator weights. Subsequently, it applied a comprehensive evaluation method to measure the food system resilience index. AHP captures decision-makers’ preferences through pairwise comparisons, while entropy quantifies uncertainty in the data. This hybrid approach balances expert judgment with empirical data, enhancing the rationality and robustness of the evaluation58. The calculation procedure is as follows:

The subjective weight vector of AHP is denoted as w1. The objective weight vector of the entropy method is denoted as w2. The weight matrix obtained by both methods is optimized by linear combination to obtain the minimum optimized value:

The first-order derivatives of the matrix are taken and expanded to obtain:

The above equation gives \(\left( {a_{1} ,a_{2} } \right)\), and its normalization obtains the following linear coefficients, \(a_{k}^{*}\).

Equation (17) obtains the final combination weight matrix w*.

Equation (18) shows the composite index of food system resilience.

Benchmark regression model

The FPR index in this study is based on annual observations from 31 provinces. A two-way fixed effects model is employed to capture both provincial heterogeneity and temporal dynamics, providing a robust framework for assessing the marginal impact of climate change on food production resilience. This model also accommodates moderating variables, enabling evaluation of the effectiveness of adaptive measures. Based on the research hypotheses and analytical framework described above, the following two-way fixed effects model is constructed to examine the impact of climate change on food production resilience:

where \({\text{Re}} silience_{it}\) represents the FPR in province i in year t; \(AT_{it}\) and \(|SPI|_{it}\) are, respectively, the average annual accumulated temperature and annual precipitation anomaly index in province i in year t; \(X_{it}\) is control variable; \(u_{i}\) represents the individual fixed effects; \(v_{t}\) shows the time fixed effects; \(\alpha_{0}\) is a constant term; \(\varepsilon_{it}\) indicates a random perturbation term; and \(\alpha_{1}\), \(\alpha_{2}\), and \(\alpha_{3}\) are the parameters to be estimated.

Moderating effects model

Drawing on the models already set up55, the following moderating effects model is constructed:

where \(SID{}_{it}\) represents the crop diversity index of area i in year t; \(SID_{it} \times AT_{it}\) and \(SID_{it} \times |SPI|_{it}\) signify the interaction terms; \(\beta_{0}\) is a constant term; \(\beta_{1}\), \(\beta_{2}\), \(\beta_{3}\), \(\beta_{4}\), \(\beta_{5}\), and \(\gamma\) are the parameters to be estimated.

Results of empirical analysis

Analysis of the present status

Trends in FPR

The FPR of different provinces was visualized using ArcMap 10.8.1. Given that FPR exhibits long-term trends, short-term changes are less apparent. This analysis covers 2010–2022. As shown in Fig. 2, substantial spatial variation exists. Higher FPR is concentrated in major food-producing provinces—Hebei, Henan, Heilongjiang, Shandong, and Sichuan—benefiting from favorable geography, fertile soils, and strong agricultural output, as well as preferential policy support. In contrast, production-consumption balanced areas face natural constraints. For example, Gansu and Ningxia suffer from persistent drought and soil erosion, while Qinghai and Tibet are hindered by high altitude, cold climate, and underdeveloped agricultural infrastructure. Major food-consuming areas such as Shanghai and Tianjin exhibit high economic development but limited arable land; industrial upgrading and urbanization have shifted labor away from agriculture, causing FPR to lag behind economic growth.

Figure 3 displays the time-series evolution characteristics of different regions obtained by homogenizing. FPR fluctuates between 0.25 and 0.55 during the study period. A peak in 2019 likely reflects favorable climatic conditions, absence of droughts and floods during critical growing periods, and increased per-hectare yields. As a whole, the change curve of the country’s FPR level is relatively flat and on an upward trend. It rose from 0.376 to 0.435, probably because agricultural technological progress and policy dissemination in agriculture have improved the adaptability of crops to climate stress. The temporal patterns of FPR in the subregions mirror the national trend, all exhibiting upward trajectories, but with notable spatial variation. The mean value of the major food-producing areas is 0.496 (the whole country: 0.412), which is significantly higher than that of the major food-consuming areas (0.324) and the balanced area (0.368). The main reason may be the obvious differences in resource endowment and institutional environment of each functional sub-region.

Trends in climate change development

Processing the absolute value data of the AT and |SPI| obtains the climate change trend of the whole country from 2010 to 2022, as depicted in Fig. 4. |SPI| experiences peak values in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2021, indicating the prominent degrees of precipitation anomalies in China within these years. AT shows a fluctuating upward trend, ranging between 18.8 and 19.6. Four peak values occur in 2012, 2018, 2019, and 2022, and three low minimum values are in 2010, 2014, and 2021. The primary characteristics of climate change during this period are a general increase in cumulative temperature and erratic precipitation patterns. While higher temperatures can promote a northward shift in crop maturity and increase regional grain yields59, they can also intensify water evaporation and exacerbate pest and disease outbreaks60. Both extreme precipitation and drought events increase the vulnerability of food systems.

Analysis of baseline regression results

The data were used to acquire the baseline regression results, estimating the impacts of climate change on the level of FPR (Table 3). Then, the Driscoll-Kraay test is employed to check the heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional correlation issues. In Table 3, Model 1, including only the independent variable, shows that both AT and precipitation anomaly negatively affect FPR. Model 2, incorporating control variables, reveals that both AT and precipitation anomalies have negative impacts on FPR, which are statistically significant at 5% and 10% levels, respectively. These results indicate that climate change considerably inhibits FPR, thereby supporting Hypothesis H1.

In the control variables, rural electricity consumption has a significant and positive impact on the FPR, indicating that electricity fuels modern agricultural technologies and rural informatization, thereby enhancing the FPR. Urbanization level has a remarkable and negative effect on FPR. This result suggests that increased urbanization accelerates the reallocation of resources, such as shifting land investment from low-value agricultural uses to higher-value industries, resulting in reduced food production61. The gradual shift toward a “food-oriented” cropping structure has a substantial and beneficial effect on FPR. The policy, often coupled with land transfers and large-scale operations, enhances resource use efficiency and farmers’ risk resilience. Several factors may explain why agricultural trade openness, rural electricity consumption, the non-farm economy share, and the urban–rural earnings inequality show insignificant impacts on FPR. China’s minimum purchase price and tariff quota system buffer domestic food production from international price fluctuations. Additionally, growth in the non-farm economy may compensate for agricultural labor shifts through industrial income. Grain subsidy policies help secure farmers’ income, mitigating the impact of the urban–rural income gap on FPR.

Robustness tests

Omitted variable bias

Referring to the method of Wang62, this study constructs different models using existing variables to evaluate the possible erroneous tendency introduced by variables not monitored. First, it develops Models 3 and 5. Model 3 introduces only explanatory variables. Considering that the proportion of the non-farm economy, urbanization level, and cropping structure directly affect the validity of the FPR, Model 5 incorporates these three control variables, so as to estimate coefficients for the predictor variables under the two constrained models \(\beta_{m}\). Second, the research constructs two complete models and introduces other control variables based on Models 3 and 5 to get Models 4 and 6. The estimated coefficients under the two complete models are \(\beta_{n}\). Finally, the coefficient of variation is calculated \(\varepsilon = \left| {{{\beta_{n} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\beta_{n} } {\left( {\beta_{m} - \beta_{n} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {\beta_{m} - \beta_{n} } \right)}}} \right.\). The larger the coefficient is, the more it can indicate that the potential impact of unobserved variables on the parameter estimation of predictor variables is smaller. Table 4 represents the specific test results. The coefficients of variation of AT and |SPI| are much larger than 1, indicating that the estimation results of the explanatory variables are less likely to be affected by the bias of the omitted variables. The results support the robustness of the model estimates.

Replacement models

The FPR values calculated by the indicator system are between \(\left[ {0,1} \right]\), which is consistent with the characteristics of a restricted dependent variable. Therefore, the Tobit model is used to re-estimate Model 2. Column (1) of Table 5 shows the estimation results of the Tobit model. The direction of the influence of the estimated coefficients on the AT and |SPI| in the Tobit model and the baseline regression model remains the same, and the statistical significance does not change significantly, which further verifies the reliability of the baseline regression results.

Rejecting samples

To focus on FPR, the analysis excludes six regions with low food production—Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Hainan, Qinghai, and Tibet. The remaining 325 samples are used for parameter estimation. Column (2) of Table 5 presents the results of the model. Based on the results, the coefficients of AT and |SPI| are negative and significant at 5% level, demonstrating the robustness of the estimates with the reduced sample size.

Replacement of the independent variable

The number of days with maximum daily temperatures exceeding the 90th percentile of a historical baseline (HTD, or extreme high-temperature days) was used as an alternative to accumulated temperature as the independent variable for temperature 63. As shown in column (3) of Table 5, HTD also had a significant and negative effect on crop production resilience, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Moderation effects analysis

To examine the moderating effect of crop diversity, this study incorporates the SID as a moderator and introduces interaction terms into the regression analysis. In Table 6, Model 7 presents the results after including SID and the interaction terms SID × AT and SID ×|SPI| with the independent variables. Precipitation anomalies show a significantly negative effect on FPR at the 5% level, while the interaction with crop diversity is positive and significant at 10% level, indicating that crop diversity mitigates the negative impact of precipitation anomalies on FPR, supporting Hypothesis H2b. The effect of accumulated temperature on FPR is negative and significant at 5% level, but its interaction with crop diversity is insignificant, failing to support Hypothesis H2a. Overall, enhancing crop diversity reduces single-disaster risks, buffers climate shocks, and strengthens the stability and security of food systems, consistent with Hypothesis H2.

SID × AT is insignificant, which may be due to the non-linear and threshold effects of high temperatures on crops. Once a certain temperature is exceeded, all crops are reduced, resulting in the interaction being masked64. The buffering effect of crop diversity is highly dependent on differences in crop functional traits. Even species richness may fail to regulate if crop functional traits converge65. For example, a region with high crop diversity but similarity in key heat tolerance traits (e.g., all C3 crops) fails to show differentiated adaptive responses to increasing AT66.

Analysis of regional heterogeneity

The paper further analyzes the spatial heterogeneity to measure the influence of climatic shocks on the FPR in the three principal functional food zones. As shown in Table 7, in major food-producing areas, AT and |SPI| have negative coefficients, which are statistically significant at 10% and 1% levels, implying the considerable inhibitory effects of climate change on FPR. This is mainly because the main food-producing provinces are located in the Central China region, Northeast China region, and East China region, within climate transition zones (e.g., warm temperate to mesothermal, semi-moist to semi-arid). Small climate changes in these areas can exceed crop adaptation thresholds. The predominance of monoculture staple crops in these regions also increases vulnerability to climatic shocks. In major food-consuming areas, AT has a prominent negative effect on FPR, while |SPI| is insignificant, which can be explained by the limited arable land resources of these areas, including the Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei regions. These regions have advanced urbanization and development, and the heat island effect exacerbates the rise in nighttime temperatures, inhibiting the accumulation of sugar in grain crops. These areas can regulate water demand through facility-based agriculture, buffering the dampening effect of precipitation fluctuations on FPR. The coefficients of AT and |SPI| on FPR in production-consumption balanced areas are insignificant because most of these places are located in arid or high-cold zones, where long-term climatic stresses have contributed to the formation of inherent crop resilience. Drought and cold-resistant technologies for grain cultivation have been promoted. Some examples are drought-tolerant potatoes in Gansu and barley-rape rotation in Tibet’s river valleys. Water conservation projects such as Karez in Xinjiang and rainwater harvesting cellars in Shanxi effectively buffer the effects of climate disruption.

Table 8 represents the spatial differences in the effects of crop diversity in the three regions. The results show that the interaction term coefficient between crop diversity and |SPI| in the major food-producing regions is positive and significant at 10% level, while the interaction term between AT and crop diversity is insignificant. This suggests that crop diversity significantly mitigates the suppressive impact of anomalous precipitation on FPR in the major food-producing areas, but insignificantly moderates the AT. Most main production areas are located in plains with deep soil layers. A three-dimensional pattern of water use is formed through the construction of a “deep-rooted system–shallow-rooted system” multi-type crop vertical complementary system. Together with improvements in irrigation systems, this effectively mitigates the impact of precipitation anomalies. The main crops in these areas are mostly high-light-efficiency crops. As a result of the convergence effect of photosynthetic efficiency, the optimal temperature ranges for photosynthesis among crops are highly overlapping, and the range of temperature adaptation cannot be expanded through crop diversity67. The lack of vertical topographic differentiation in the plains limits the compensation of diversity for AT. The coefficient associated with the AT and FPR interaction item is not significantly positive but significantly negative in major food-consuming areas. The |SPI| and FPR interaction item is insignificant because of the limited and fragmented distribution of arable land in the main consumption area, which hinders the formation of large-scale crop diversity. Even if localized diversification occurs, the total area and spatial continuity are insufficient to effectively diversify the systemic risk of precipitation anomalies. The regulatory effect of crop diversity in production-consumption balanced areas is insignificant. The balanced areas rely more on traditional cultivation modes and lack technological means such as precision irrigation and intelligent monitoring, preventing the full activation of crop diversity’s climate adaptation potential. As young and middle-aged laborers migrate to cities, the farmers tend to simplify the planting structure to reduce labor intensity, further limiting the effectiveness of crop diversity.

Discussion

This study aims to examine the impact of climate change on the food production resilience. Building on a traditional analytical framework, the research develops a comprehensive indicator system to quantify FPR across three dimensions: resistance, adaptability, and regenerative capacity. Using this framework, the study validates the findings of Su Fang et al., which established a food security indicator system using the standardized range method. This system assesses availability, accessibility, usability, and stability, highlighting the negative impact of temperature and precipitation on food security in China55. Furthermore, building on the framework developed by Zhou Mi et al., this paper examines regional differences in food production resilience across China’s three major food-producing regions, which are categorized based on food policies68. These findings resonate with the existing literature, which indicates that climate change results in reduced yields of key food crops13, increased variability in production, and a heightened risk of simultaneous crop failures69. Collectively, these studies highlight the complex relationship between climate change and food production systems70. The extensive research on the effects of climate change on yields and food security provides important support for this study, further underscoring the need to investigate resilience in food production.

Unlike the aforementioned scholars, this study incorporates both heat stress (measured by accumulated temperature) and moisture stress (evaluated through precipitation anomalies) into a composite climate indicator. This integrated approach addresses the limitations associated with relying on a single or simple climatic variable, thereby offering a more holistic assessment of climate-related threats to agricultural productivity. Methodologically, a game-theoretic weighting approach is employed to integrate subjective and objective weights, addressing the limitations of entropy-based methods and enhancing the robustness of FPR measurement. The study further examines heterogeneity in climate impacts across major production regions and the moderating role of crop diversity, revealing interaction mechanisms and marginal effects among climate change, FPR, and crop diversity. These insights offer policymakers evidence for differentiated, region-specific climate governance strategies, improving the feasibility and effectiveness of policy implementation.Although this study yields findings of practical significance, it has several limitations. First, it primarily investigates provincial-level samples in China. Analysis at this scale, based on macroeconomic indicators, may obscure intra-provincial variations and micro-level mechanisms. Future research could refine the sample to finer regional levels, such as cities or counties, to more comprehensively explore the local dynamics and boundary conditions of climate change impacts on food production. Second, this study focuses on macro-level climate variables, leaving the resilience mechanisms for specific types of climate disasters underexplored. Future work could investigate these mechanisms to inform more targeted and precise policy interventions. Third, this study focuses mainly on China. Future research could strengthen international comparative studies to more deeply understand China’s relative position in global FPR and to formulate more effective food security strategies.

Conclusion and implications

Main conclusions

This paper analyzes the mechanism of climate anomalies’ effect on FPR and the mitigating effects of crop diversity through empirical data. The principal conclusions are outlined as follows. First, the overall trend of FPR is upward in Chinese provinces, with the major food-producing areas higher than the national average, the major food-consuming areas, and the balanced areas. Second, AT and |SPI| show a significant and inhibitory effect on FPR. Improving crop diversity can effectively mitigate the inhibitory effect of climate change on FPR, mainly by significantly weakening the negative effect of extreme precipitation, but not that of AT. Third, the inhibitory effect of climate change is most statistically significant in the major food-producing areas. The major food-consuming areas rely significantly on the negative effect of precipitation anomalies, while the effect of AT is insignificant. Neither AT nor precipitation anomalies have significantly negative effects in the balanced areas. The moderating role of crop diversity on FPR is reflected in its mitigation of precipitation anomalies. This effect is most pronounced in the major food-producing areas and is insignificant in the major food-consuming areas and balanced areas.

Policy implications

The following policy implications are relevant for stabilizing food security production:

First, addressing the inhibitory effects of rising AT and precipitation anomalies on the FPR requires implementing many policies, for example, building a climate-smart agricultural production system. Another policy is the establishment of a climate monitoring and early warning platform based on the big data wisdom platform to enhance the ability to forecast and mitigate meteorological disasters. In terms of technological empowerment, the focus should be on developing crop breeding and improvement for flood and drought resistance, as well as smart water management technologies. Regarding engineering prevention and control, initiatives should be undertaken to enhance the multi-dimensional disaster early warning and response system and food production infrastructure, starting with drainage systems, water storage projects, and wind and sand control projects.

Second, regarding the regulatory role of crop diversity, it is crucial to develop policies for the promotion of regionally differentiated crop planting structures. By combining modern biological breeding with traditional cultivation methods, emphasis should be placed on cultivating crops with advantageous traits, such as resistance to humidity, drought, salinity, and alkalinity. Additionally, a systematic promotion system for high-quality seeds should be established. Through policy subsidies, insurance, and other tools, farmers should be encouraged to adopt diversified cultivation practices to enhance the adaptability of food crops to extreme climate stresses. The moderating effect of crop diversity is significant for precipitation anomalies but not for rising accumulated temperatures, indicating that China’s current crop diversity is uneven in responding to different climate stressors. Its capacity to buffer high-temperature stress remains underutilized. Strengthening China’s crop diversity system requires further refinement in variety breeding, cultivation pattern optimization, and technical support.

Third, regionally differentiated food security measures should be implemented. Given the strategic importance of the main producing areas, policy preferences and investments in resources and technology should be strengthened. Emphasis should be placed on supporting the establishment of high-standard farmland and the research and development of superior crop varieties. Agricultural infrastructure and equipment should be upgraded rapidly to enhance the comprehensive grain production capacity. Due to their economic development and high urbanization, the main marketing areas should fully leverage their economic advantages. Focus should be on developing capital- and technology-intensive agriculture, facilitating the integration of new energy technologies in food production systems, promoting intensive and modernized agricultural models, increasing food self-sufficiency, and reducing dependence on foreign food supplies. Since the ecological balance in the production-marketing balance areas is more fragile, the government should increase policy support, especially by collaborating with financial institutions to provide agricultural loans and insurance support for grain farmers. Attempts should be made to strengthen the agricultural industrial route and enhance the market competitiveness of food products.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chou, J. et al. Resilience of Grain Yield in China Under Climate Change Scenarios. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 641122 (2021).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14(5), 054010 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. Global supply chain drivers of scarce water caused by grain production in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 111, 107737 (2025).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. In Brief to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024-Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. (FAO, (2024).

Myers, S. S. et al. Climate Change and Global Food Systems: Potential Impacts on Food Security and Undernutrition. Annu. Rev. Public Health 38(1), 259 (2017).

Birthal, P. S. & Hazrana, J. Crop diversification and resilience of agriculture to climatic shocks: Evidence from India. Agric. Syst. 173, 345–354 (2019).

Yanlei, G. A. O. et al. Impact of urbanization on food security: Evidence from provincial panel data in China. Res. Sci. 41(8), 1461–1474 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Climate change impacts on the topography and ecological environment of the wetlands in the middle reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo-Brahmaputra River. J. Hydrol. 590, 125419 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Climate Change Is Leading to a Convergence of Global Climate Distribution. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL106658 (2024).

Rocque, R. J. et al. Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 11(6), e046333 (2021).

Carter, C. et al. Identifying the economic impacts of climate change on agriculture. Annu. Rev. Res. Eco. 10(1), 361–380 (2018).

Esham, M. et al. Climate change and food security: a Sri Lankan perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 20(3), 1017–1036 (2018).

Dos Santos, C. A. C. et al. Trends of extreme air temperature and precipitation and their impact on corn and soybean yields in Nebraska, USA. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 147(3), 1379–1399 (2022).

Osborne, T. M. & Wheeler, T. R. Evidence for a climate signal in trends of global crop yield variability over the past 50 years. Environ. Res. Lett. 8(2), 024001 (2013).

Piao, Y. Global Food Security under Climate Change: Transmission Mechanism and System Transformation. World Agric. 10, 16–26 (2023).

Holling, C. S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4(1), 1–23 (1973).

Walker, B. et al. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-00650-090205 (2004).

Wu, W. et al. Urban resilience framework: A network-based model to assess the physical system reaction and disaster prevention. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 109, 107619 (2024).

Martin, R. Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. eco. geog. 12(1), 1–32 (2012).

Seekell, D. et al. Resilience in the global food system. Environ. Res. Lett. 12(2), 025010 (2017).

Chen, Y., Zeng, M. & Chen, B. Impact of climate change on the resilience of food production: Research of the moderating effect based on crop diversification. Acta Ecol. Sin 44, 6937–6951 (2024).

Béné, C. et al. Is resilience a useful concept in the context of food security and nutrition programmes? Some conceptual and practical considerations. Food secur. 8, 123–138 (2016).

Hui, J., Yao, C. & Zhaoyang, L. I. U. Spatiotemporal pattern and influencing factors of grain production resilience in China. Econ. Geogr. 43(6), 126–134 (2023).

Chemeris, A., Liu, Y. & Ker, A. P. Insurance subsidies, climate change, and innovation: Implications for crop yield resiliency. Food Policy 108, 102232 (2022).

Calvin K, Dasgupta D, Krinner G, et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds). (IPCC, 2023).

Thompson, M. Climate change challenges for Queensland’s emergency management sector. Australian J. Emerg. Manag. 34(1), 13 (2019).

Hultgren, A. et al. Impacts of climate change on global agriculture accounting for adaptation. Nature 642(8068), 644–652 (2025).

Xie, W., Wei, W. & Cui, Q. The impacts of climate change on the yield of staple crops in China: A Meta-analysis. China Popul. Res. Environ. 29(1), 79–85 (2019).

Asseng, S. et al. Climate change impact and adaptation for wheat protein. Glob. Change Biol. 25(1), 155–173 (2019).

Moradi, E. et al. Assessment of snow cover dynamics and the effects of environmental drivers in High Mountain ecosystems. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 114, 107969 (2025).

Pinke, Z. et al. Climate change and modernization drive structural realignments in European grain production. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 7374 (2022).

Atanga, R. A. & Tankpa, V. Climate change, flood disaster risk and food security nexus in Northern Ghana. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 706721 (2021).

Ju, H. et al. Multi-stakeholder efforts to adapt to climate change in China’s agricultural sector. Sustainability 12(19), 8076 (2020).

Kurukulasuriya, P. et al. Will African agriculture survive climate change?. World Bank Eco. Rev. 20(3), 367–388 (2006).

Raja, B. & Vidya, R. Application of seaweed extracts to mitigate biotic and abiotic stresses in plants. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 29(5), 641–661 (2023).

Prakash, P. et al. Short communication effect of seaweed liquid fertilizer and humic acid formulation on the growth and nutritional quality of Abelmoschus esculentus. Asian J. Crop Sci 10, 48–52 (2018).

Fan, Z., Qin, Z. & Yu, S. Impact of extreme temperature on the resilience of grain production: perspectives on green finance. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 32(5), 896–910 (2024).

Savary, S. et al. Mapping disruption and resilience mechanisms in food systems. Food Secur. 12(4), 695–717 (2020).

Kumar, N. et al. A novel framework for risk assessment and resilience of critical infrastructure towards climate change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 165, 120532 (2021).

Brown, I. Climate change and soil wetness limitations for agriculture: spatial risk assessment framework with application to Scotland. Geoderma 285, 173–184 (2017).

Lin, B. B. Resilience in agriculture through crop diversification: adaptive management for environmental change. Bioscience 61(3), 183–193 (2011).

Renard, D., Mahaut, L. & Noack, F. Crop diversity buffers the impact of droughts and high temperatures on food production. Environ. Res. Lett. 18(4), 045002 (2023).

Jie, Y., Yi, D., Chaofan, Z., Lixin, T. & Runguo, Z. Effects of woody plant diversity on aboveground biomass and its scale dependence in tropical natural forest in Hainan Island of southern China. J. Beijing For. Univ. 46(12), 1–10 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Improving the productivity and stability of oilseed cropping systems through crop diversification. Field Crop Res. 237, 65–73 (2019).

Skendi, S. et al. The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Insect Pests. Insects https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050440 (2021).

Jansson, J. K. & Hofmockel, K. S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18(1), 35–46 (2020).

Munir, S. & Bashir, N. H. Crop diversity and pest management in sustainable agriculture. J. Integr. Agric. 18(9), 1945–1952 (2019).

Lange, M. et al. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 6(1), 6707 (2015).

Cregger, M. A. et al. The impact of precipitation change on nitrogen cycling in a semi-arid ecosystem. Funct. Ecol. 28(6), 1534–1544 (2014).

McDaniel, M. D., Tiemann, L. K. & Grandy, A. S. Does agricultural crop diversity enhance soil microbial biomass and organic matter dynamics? A meta- analysis. Ecol. Appl. 24(3), 560–570 (2014).

Ullah, A. et al. Recognizing production options for pearl millet in Pakistan under changing climate scenarios. J. Integr. Agric. 16(4), 762–773 (2017).

Constas M A, d’Errico M, Hoddinott J F, et al. Resilient food systems–A proposed analytical strategy for empirical applications: Background paper for The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. In: FAO Agricultural Development Economics Working Paper 21-10. (Food & Agriculture Org., 2021)

Liu, J. & Yao, Z. “Storing grain in technology”: internal mechanisms of agricultural new quality productivity enhancing grain production resilience. Res. Agric. Mod. https://doi.org/10.13872/j.1000-0275.2025.0857 (2025).

Zhang, M. D. & Hui, L. W. Spatial disparities and identification of influencing factors on agricultural economic resilience in China. World Agric 1, 36–50 (2022).

Su, F. et al. Impact of climate change on food security in different grain producing areas in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 32(8), 140–152 (2022).

Cai, J. et al. Research on the impact of climate change on green and low-carbon development in agriculture. Ecol. Ind. 170, 113090 (2025).

Mingming, C. & Changhong, N. I. E. Study on food security in China based on evaluation index system. Bulletin Chin. Acad. Sci. (Chin. Ver.) 34(8), 910–919 (2019).

Zhou, F. & Chen, T. Y. A synergetic intuitionistic fuzzy model combining AHP, entropy, and ELECTRE for data fabric solution selection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 58(5), 137 (2025).

Li, E. et al. The possible effects of global warming on cropping systems in China Ⅻ Ⅰ. Precipitation limitation on adjusting maturity cultivars of spring maize and its possible influence on yield in three provinces of northeastern China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 54(18), 3847–3859 (2021).

Wakil, W. et al. Climate change consequences for insect pest management, sustainable agriculture and food security. Entomologia Generalis 45(1), 37–51 (2025).

Ning-lu, C. & Wen-xin, Q. Modeling the effects of urbanization on grain production and consumption in China. J. Integr. Agric. 16(6), 1393–1405 (2017).

Wang, W., Xie, J. & Zhang, L. Regional intergenerational mobility preferences of population migration: micro evidence and impact mechanism. J. Manag. World 35(7), 89–103 (2019).

Guo, K., Ji, Q. & Zhang, D. A dataset to measure global climate physical risk. Data Brief 54, 110502 (2024).

Deryng, D. et al. Global crop yield response to extreme heat stress under multiple climate change futures. Environ. Res. Lett. 9(3), 034011 (2014).

Isbell, F. et al. Biodiversity increases the resistance of ecosystem productivity to climate extremes. Nature 526(7574), 574–577 (2015).

Cadotte, M. W., Carscadden, K. & Mirotchnick, N. Beyond species: functional diversity and the maintenance of ecological processes and services. J. Appl. Ecol. 48(5), 1079–1087 (2011).

Yamori, W., Hikosaka, K. & Way, D. A. Temperature response of photosynthesis in C3, C4, and CAM plants: temperature acclimation and temperature adaptation. Photosynth. Res. 119(1), 101–117 (2014).

Zhou M, Niu H, Wei C, et al. Can the upgrading of agriculture insurance guarantee improve the food production resilience?. Chinese J. Agric. Res. Reg. Plan. 7 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Advances in the study of climate change impact on crop producing risk[J]. J. Nat. Disasters 31, 1–11 (2022).

Vermeulen, S. J., Campbell, B. M. & Ingram, J. S. I. Climate change and food systems[J]. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 37, 195–222 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by China National Social Science Fund Project grant No.23CJY052, Chang’an University Central University Basic Research Business Expenses Special Fund Project grant No.300102114607.

Funding

This research was supported by China National Social Science Fund Project grant No.23CJY052, Chang’an University Central University Basic Research Business Expenses Special Fund Project grant No.300102114607.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jie Cai: Conceptualization and design revision of the original drafts. Xiaoling Zhang & Zhimin Du & Minglong Xian: data analysis and writing revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, J., Zhang, X., Du, Z. et al. Research on the impact of climate change on food production resilience in China. Sci Rep 15, 45578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29661-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29661-4