Abstract

Melanoma is an aggressive skin cancer associated with a poor prognosis, making survival time a primary concern for patients. This study applies five machine learning models to predict survival rates for melanoma patients, aiming to improve prognostic accuracy and support clinical decision-making. Melanoma patient data were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Five machine learning models—Random Forest, Decision Tree, XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM—were applied to predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates for melanoma patients. The CatBoost model was selected for its superior performance and evaluated using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), confusion matrix, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA) to assess its accuracy and clinical utility. This study analyzed data from 4,875 patients with cutaneous melanoma, incorporating thirteen demographic and clinical variables to develop survival prediction models using five machine learning algorithms. Among these, the CatBoost model demonstrated the best overall performance and stability following five-fold cross-validation. The model achieved AUC values of 0.7577, 0.7595, and 0.7557 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival predictions, respectively. Decision Curve Analysis further confirmed its clinical utility, while consistent precision across both training and test sets indicated robust generalization and reliable predictive capability. These findings highlight the CatBoost model’s potential as a practical and accurate tool for assessing melanoma prognosis and supporting individualized clinical decision-making. This model provides clinicians with an effective tool for early intervention, which may ultimately contribute to improved patient survival outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer originating from melanocytes, poses a significant global health challenge due to its high potential for metastasis and variable prognosis1,2. Despite advances in treatment, patient outcomes remain dependent on factors such as tumor stage, location, and individual patient characteristics3,4. Accurate survival predictions are essential for guiding clinical decision-making and personalizing treatment plans, which ultimately improve patient care.

This study utilizes data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, a comprehensive resource managed by the National Cancer Institute that provides data on cancer incidence, treatment, and survival in the United States. Leveraging SEER data, we developed a multivariable predictive model that incorporates key prognostic factors such as Breslow Thickness, Mitotic Rate, lymph node involvement, tumor size (Measured Basal Diameter), primary tumor site, and age at diagnosis to predict survival outcomes for melanoma patients5,6,7,8,9. These variables have been recognized as significant indicators of melanoma prognosis, as Breslow Thickness measures tumor invasion depth10, Mitotic Rate reflects cellular proliferation11, and lymph node involvement indicates potential metastasis. The primary tumor site and patient age further influence treatment choices and survival outcomes.

To enhance predictive accuracy, we implemented five machine learning algorithms: Random Forest, Decision Tree, XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM, focusing on 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival predictions. CatBoost, in particular, is a gradient boosting algorithm known for its precision, scalability, and efficient handling of categorical features, making it a strong choice for survival prediction in cancer patients12,13. Our model aims to support clinicians by improving prognostic assessments, enabling early interventions for high-risk patients, and advancing understanding of melanoma biology. The potential of machine learning for personalized treatment planning, risk stratification, and future melanoma prognosis and treatment research has been highlighted14,15.

Methods

Data source and patient selection

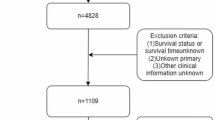

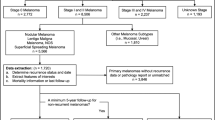

The data of patients with cutaneous melanoma were obtained from the SEER database, a public database and research resource established by the National Cancer Institute of the United States16,17. Based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3/WHO 2008), patients diagnosed with melanoma between 2000 and 2021 with primary site codes C44.3-44.9 were included. Cases were excluded if information was incomplete, including Age recode, Sex, Year of diagnosis, LDH Pretreatment, Breslow Thickness, Mitotic Rate, Ulceration, CS lymph nodes, Marital Status, Median household income, Site recode, Race recode, Primary Site, Survival months, and SEER cause-specific death classification. Ultimately, a total of 4,875 eligible patients with cutaneous melanoma were included in this study for further analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the study design and patient flowchart.

Study variables

This study incorporated multiple demographic and clinical factors known to influence melanoma prognosis, including age, sex, year of diagnosis, LDH pretreatment level, Breslow thickness, mitotic rate, ulceration status, lymph node involvement, marital status, median household income, tumor site, and race. These variables were selected to establish a comprehensive framework for analyzing patient survival. Several key variables—LDH pretreatment level (88.6%), Breslow thickness (64.03%), and mitotic rate (93.42%)—had high proportions of missing data. To preserve sample size and maintain cohort representativeness, cases were not excluded. Instead, missing values for these variables were imputed using a random forest algorithm. The imputed data were used for model training, while cases with complete or minimally imputed data were reserved for testing. Model performance was assessed using five-fold cross-validation. This approach minimized potential bias from data exclusion, improved robustness, and enhanced generalizability when analyzing heterogeneous or incomplete clinical data. Survival months and SEER cause-specific death classification served as outcome variables for assessing melanoma-specific survival.

CatBoost model

CatBoost, a machine learning algorithm based on gradient boosting decision trees, is known for its high accuracy, performance, and scalability, particularly when handling categorical features14,15,18. This study employs CatBoost, along with other machine learning algorithms, to build predictive models for melanoma patient survival. A brief overview of the fundamental principles underlying each algorithm is provided in Supplementary Text 1. To ensure robust model performance, we used five-fold cross-validation on the training set, optimizing model parameters through repeated adjustments to enhance stability. Furthermore, an independent test set was reserved to validate model performance, thereby assessing the generalizability of the developed models.

The primary objective of this study is to create a reliable machine learning model that can predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival outcomes for patients with cutaneous melanoma. By leveraging advanced machine learning techniques, we aim to improve survival prognosis and support clinical decision-making. This approach underscores the potential of machine learning in developing precise prognostic models that accommodate complex, multifactorial clinical data, thereby advancing the field of melanoma research and aiding in personalized patient management.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we summarized the basic characteristics of melanoma patients by presenting categorical variables as counts (n) and percentages (%), while continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or median (range) for non-normally distributed data. Differences between the training and test sets were evaluated using the chi-square test for categorical variables, and t-tests or Z-tests for continuous variables, depending on the data distribution. Statistical significance of these differences was determined by p-values, allowing us to assess any notable variations between the two datasets.

To develop prognostic models for melanoma patients, we utilized five machine learning algorithms: Random Forest, Decision Tree, XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM. We evaluated the models’ predictive performance through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and confusion matrices, calculating the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) to measure the accuracy of each model. Additionally, precision, a key metric from the confusion matrix, was calculated to further assess model performance. Calibration curves and decision curve analysis (DCA) were also conducted to evaluate the reliability and clinical utility of each model, providing a comprehensive assessment of their prognostic value for melanoma survival predictions.

Results

Patient characteristics

The following factors were included as explanatory variables: age at diagnosis, race, sex, Breslow Thickness, LDH Pretreatment Level, Mitotic Rate, lymph node involvement, ulceration status, marital status, and median household income (Table 1). The study cohort consisted of 4,875 patients diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma, divided into training (n = 3,900) and test sets (n = 975) for model development and evaluation. The average age at diagnosis across all patients was approximately 60–64 years, with no significant differences observed between the training (60–64 years) and test sets (60–64 years). The majority of patients were male (65.4%) and White (96.7%), while other racial groups, including Black, AI/AN, and A/PI, represented less than 4% of the cohort. Notably, a large proportion of patients had missing LDH Pretreatment data (88.6%), with only 6.11% presenting high levels. Breslow Thickness data was also frequently missing (64.03%), and 28.65% of patients had no measurable tumor or mass.

Clinical variables such as the Mitotic Rate and lymph node status were largely unreported, with 93.42% of patients missing mitotic rate information and only 17.82% having documented lymph node involvement. Ulceration status was similarly sparse, with 6.48% of cases confirmed to have ulceration. Marital status data indicated that the majority were married (57.75%), followed by single (19.61%) and widowed (11.47%) patients. The median household income for the cohort was $72,499.5, with a range of $6,000 to $132,000. All patients had skin as the primary site, with the most frequent code being C44.9 (74.85%). Statistically significant differences were identified between the training and test sets for LDH pretreatment levels (P < 0.0001), Breslow Thickness (P < 0.0001), and marital status (P = 0.0002), suggesting potential disparities in the clinical and demographic distributions across these subsets. The primary outcome variables assessed in this study included survival months and overall survival, serving as essential endpoints for the analysis.

Feature predictor selection

Using the CatBoost algorithm, we quantified the relative importance of clinical and demographic variables in predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival among patients with cutaneous melanoma (Fig. 2). In the 1-year model, Mitotic Rate (31.75) and LDH Pretreatment (12.55) were the most influential predictors, followed by Year of Diagnosis (9.34), Primary Site (9.27), CS Lymph Nodes (7.32), and Breslow Thickness (6.85). Age recode (6.61) and Ulceration (5.59) showed moderate contributions, whereas Sex (5.22), Marital Status (4.91), Race recode (0.36), Median Household Income (0.23), and Site recode (0.00) had minimal effects. Comparable patterns were observed in the 3-year and 5-year models, where Mitotic Rate remained the strongest predictor (29.58 and 28.57, respectively), with LDH Pretreatment (11.93–11.30) and Age recode (13.79) maintaining high relevance. Across all timepoints, clinical indicators—particularly Mitotic Rate, LDH Pretreatment, and Age recode—consistently outperformed demographic factors, underscoring their central role in melanoma prognosis.

Construction of AI prognostic model

A total of 4,875 eligible melanoma patients were randomly divided into training and test sets. To preserve data completeness and cohort representativeness, cases with missing values were retained, and missing clinical variables were imputed using a random forest method. The training set incorporated all imputed data, while the test set included cases with complete data or only a single imputed feature. Model development employed five-fold cross-validation for repeated tuning and optimization. The final CatBoost model used optimized hyperparameters: subsample = 1.0, learning_rate = 0.01, l2_leaf_reg = 20, iterations = 1,000, depth = 6, colsample_bylevel = 0.6, border_count = 32, bootstrap_type = “Bernoulli,” and boosting_type = “Ordered.” Model performance was evaluated on the test set using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis, Area Under the Curve (AUC), confusion matrix, calibration curves, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) to comprehensively assess predictive accuracy and clinical utility.

Evaluating predictive models for estimating the prognosis of patients with melanoma

As shown in Fig. 3, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analyses demonstrated consistent predictive accuracy of the CatBoost algorithm across 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival models under five-fold cross-validation. The 1-year model (Fig. 3A) achieved an AUC of 0.7577, reflecting moderate predictive performance, while the 3-year model (Fig. 3B) attained the highest AUC of 0.7595, indicating strong generalizability. The 5-year model (Fig. 3C) yielded an AUC of 0.7557, confirming reliable long-term prediction capability. Collectively, the AUC values ranging from 0.7557 to 0.7595 highlight the model’s stable and consistent performance across survival periods, with the 3-year model demonstrating the best overall discrimination for melanoma prognosis.

As shown in Table 2, five machine learning models—Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), XGBoost, CatBoost, and LightGBM—were evaluated for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival prediction. In the training set, CatBoost achieved the highest AUCs of 0.8895, 0.8730, and 0.8667, respectively, demonstrating strong in-sample performance. In the test set, CatBoost maintained superior generalization with AUCs of 0.6979, 0.6975, and 0.7101 for the corresponding timeframes. These results highlight CatBoost’s consistent advantage over other algorithms, confirming its robust predictive accuracy and generalizability for melanoma survival estimation across both short- and long-term outcomes.

Model accuracy was further assessed using confusion matrices and calibration curves (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). In the training set, the CatBoost model achieved accuracies of 85%, 84%, and 84% for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival predictions, respectively, while test set accuracies were 70%, 72%, and 73%, reflecting stable yet slightly reduced performance on unseen data. As summarized in Supplementary Table S1, CatBoost outperformed other models in both datasets. Calibration curves demonstrated strong agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities across all timeframes in both the training (Supplementary Figure S2A–C) and test sets (Supplementary Figure S2D–F), confirming the model’s reliability and well-calibrated predictive behavior.

Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) further demonstrated the CatBoost model’s clinical utility across all survival timeframes (Fig. 4). For the 1-year model (Fig. 4A and D), the greatest net benefit was observed at threshold probabilities between 0.1 and 0.6 in the training set and 0.1–0.5 in the test set, reflecting an optimal balance between true and false positives. Similar patterns were observed for the 3- and 5-year models (Fig. 4B, C and E, and 4F), where maximum net benefit occurred within comparable threshold ranges. Beyond 0.6, the net benefit declined as false positives increased. These consistent trends across all models underscore the robustness, reliability, and practical value of the CatBoost algorithm in supporting clinical decision-making for both short- and long-term melanoma survival prediction.

Decision curve analysis curves of the CatBoost model in the training and test. Decision curve analysis curves for (A) 1-year, (B) 3-year, and (C) 5-year prognostic models in the training set and (D) 1-year, (E) 3-year, and (F) 5-year prognostic models in the test set. CatBoost: categorical boosting.

Discussion

This study developed and validated a machine learning model to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival outcomes in patients with cutaneous melanoma using SEER data. Five algorithms—Random Forest, Decision Tree, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—were compared to identify the optimal predictive framework for integrating demographic and clinical variables. The CatBoost model demonstrated the most stable and generalizable performance, achieving AUCs of 0.7577, 0.7595, and 0.7557 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, respectively, indicating consistent predictive accuracy across timeframes.

Leveraging a large, population-based dataset, this study highlights the strength of combining advanced machine learning with clinical data to generate interpretable and robust survival models. CatBoost effectively managed categorical and missing data while minimizing overfitting. Key prognostic factors identified included Mitotic Rate, LDH pretreatment level, Age recode, Year of Diagnosis, and Breslow Thickness. Breslow Thickness remained a dominant predictor of poor outcomes, whereas elevated LDH reflected greater tumor burden. The influence of Year of Diagnosis likely represents indirect effects of advances in diagnostics, treatment, and healthcare access.

Among all algorithms, LightGBM performed best in training, but CatBoost achieved superior generalization on the test set, confirming its robustness. Calibration and Decision Curve Analyses verified that predicted probabilities closely matched observed outcomes and offered consistent net clinical benefit across thresholds. Overall, CatBoost provides a reliable, interpretable, and clinically applicable framework for melanoma survival prediction, supporting individualized risk stratification and evidence-based treatment planning.

Despite the promising results, several limitations should be acknowledged. Key prognostic variables, including pre-treatment LDH (88.6%), Breslow thickness (64.03%), and mitotic rate (93.42%), had high proportions of missing data. These values were imputed using the random forest method to preserve sample size and maintain cohort representativeness; however, such missingness may still affect model robustness and external validity. The SEER database’s predominantly White population (96.7%) also limits generalizability, as differences in genetics, environment, socioeconomic status, and healthcare access may influence outcomes in other groups. Moreover, some predictors, such as year of diagnosis, likely serve as proxies for unmeasured factors—such as socioeconomic conditions, healthcare accessibility, and advances in diagnostic and therapeutic practices—rather than direct biological determinants. Recognizing these as proxy indicators enhances interpretability but underscores the need for caution in causal inference. Future studies should validate the model in multi-ethnic, multi-center cohorts and integrate explainable AI techniques to strengthen generalizability and clinical applicability.

Conclusion

This study establishes a robust and interpretable machine learning–based model for melanoma survival prediction, demonstrating that CatBoost effectively balances accuracy, generalizability, and clinical relevance. Utilizing a large population-based dataset and multiple prognostic features, the model delivers consistent survival estimates across 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals, enabling early intervention and individualized treatment planning. Future work should include external, multi-center validation and integrate molecular and genetic markers alongside explainable AI frameworks to enhance interpretability and clinical utility. Overall, these findings underscore the potential of machine learning to improve melanoma prognosis, optimize patient stratification, and advance precision oncology in routine clinical practice.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Nikolaou, V. & Stratigos, A. J. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 170(1), 11–19 (2014).

Helvind, N. M. et al. Incidence of in situ and invasive melanoma in Denmark from 1985 through 2012: a national database study of 24 059 melanoma cases. JAMA Dermatol. 151(10), 1087–1095 (2015).

Gershenwald, J. E. et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eight edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67(6), 472–492 (2017).

Elder, D. E., Karakousis, G. & Scolyer, R. A. Staging for melanoma-toward a new paradigm?. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 112(9), 873–874 (2020).

El Sharouni, M. A. et al. Predicting sentinel node positivity in patients with melanoma: external validation of a risk-prediction calculator (the Melanoma Institute Australia nomogram) using a large European population-based patient cohort. Br. J. Dermatol. 185(2), 412–418 (2021).

Wong, S. L. et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and management of regional lymph nodes in melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 36(4), 399–413 (2018).

Papageorgiou, C. et al. Melanoma: staging and follow-up. Dermatol. Pract. Conceptual. 11(Suppl10) (2021).

Keung, E. Z. & Gershenwald, J. E. The eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system: implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 18(8), 775–784 (2018).

Lallas, K. et al. Clinical, dermatoscopic, histological and molecular predictive factors of distant melanoma metastasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 104458 (2024).

Xia, Q. et al. Prognostic factors in postoperative patients with cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 14(5), 1947 (2024).

Tapoi, D. A. et al. The prognostic value of proliferative activity in cutaneous melanoma: a pilot study evaluating the mitotic rate and Ki67 index to predict patient outcomes. Biomedicines 12(6), 1318 (2024).

Hancock, J. T. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. CatBoost for big data: an interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 7(1), 94 (2020).

Ibrahim, A. A. et al. Comparison of the CatBoost classifier with other machine learning methods. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 11(11) (2020).

Tran, K. A. et al. Deep learning in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment selection. Genome Med. 13, 1–17 (2021).

Nguyen, T. T. et al. Multidimensional machine learning for assessing parameters associated with COVID-19 in Vietnam: validation study. JMIR Formative Res. 7(1), e42895 (2023).

Mocellin, S. & Rossi, C. R. The melanoma molecular map project. Melanoma Res. 18(3), 163–165 (2008).

Gloeckler Ries, L. A. et al. Cancer survival and incidence from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Oncologist 8(6), 541–552 (2003).

Jabeur, S. B. et al. CatBoost model and artificial intelligence techniques for corporate failure prediction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 166, 120658 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund of the Hunan Provincial Education Department (grant no. 23A0643, 23C0430, and 24A0080), the Key Laboratory of 3D Scene Visualization and Intelligent Education in Hunan Province (grant no. 2023TP1038), and the Research Center for Innovative Development of Teacher Education in the New Era.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund of the Hunan Provincial Education Department (grant no. 23A0643, 23C0430, and 24A0080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, EbH, MnT, ZW and JlZ; methodology, EbH, MnT, KbL and HyF; formal analysis, ZxN and KbL; data curation, EbH,MnT and HyF; writing-original draft preparation, EbH and MNT; writing-review and editing, ZW, MnT and JlZ; supervision, ZW and JlZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, E., Tai, M., Nie, Z. et al. Development of a machine learning-based model for prognostic prediction in melanoma. Sci Rep 15, 45628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30377-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30377-8