Abstract

The exponential growth of unstructured clinical text in electronic health records presents significant opportunities and challenges for data-driven healthcare decision-making. While automated classification of clinical narratives can unlock valuable insights, the high dimensionality and inherent sparsity of textual features often degrade model performance and computational efficiency. To address this, this study presents a lightweight continuum–reduction model that compresses longitudinal patient narratives onto a low-rank manifold without degrading clinical fidelity. Three manifold-learning techniques–Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)–were coupled with the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). Our results demonstrate that the combination of PCA and SMOTE consistently delivers superior performance, achieving 91.2% accuracy on the MTSamples corpus using 5-fold CV protocol, a statistically significant 6.4% macro-F\(_1\) gain over the unreduced baseline for traditional classifiers, and 42% faster training. This pipeline reduces model training time by 42% compared to unreduced baselines, enhancing computational efficiency without compromising diagnostic accuracy. These findings provide robust empirical evidence and a practical, scalable solution for healthcare institutions to deploy efficient clinical natural language processing pipelines, enabling large-scale analysis of medical narratives while preserving decision quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The digitization of healthcare records has led to an exponential growth in unstructured clinical narratives, which constitute 60–80% of all patient data in modern electronic health records (EHRs)1,2. These narratives including physician notes, discharge summaries, and radiology reports contain rich diagnostic information critical for patient care, clinical research, and healthcare operations. However, their high dimensionality (typically >50,000 features in Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) representations) and sparse structure pose significant challenges for automated analysis2,3.

Dimensionality reduction techniques have emerged as essential tools for processing clinical text, addressing both computational efficiency and model performance requirements4. While traditional linear methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) remain widely used in clinical natural language processing (NLP) pipelines5, recent advances in manifold learning (e.g., UMAP6 and t-SNE7) promise better preservation of nonlinear relationships in medical text. However, their comparative effectiveness in clinical text classification remains poorly understood, particularly when accounting for class imbalance8. Prior studies have either focused on single modalities (e.g.,9 examined only PCA with BERT) or neglected the interaction between feature reduction and class balancing10. This gap is particularly concerning given recent findings that improper dimensionality reduction can degrade model performance by up to 36% for rare conditions11.

In this study, we present a systematic evaluation of three dominant dimensionality reduction methods (i.e., PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP) in combination with Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) for class balancing. We assess their impact across seven machine learning classifiers and ClinicalBERT, a state-of-the-art transformer model for clinical NLP12. Our work makes three key contributions. First, through a comprehensive comparative analysis, we demonstrate that the combination of PCA and SMOTE consistently outperforms nonlinear techniques like t-SNE and UMAP across most classifiers, yielding an absolute improvement of 6.4% in macro-F\(_1\) score. Second, we show that applying PCA to ClinicalBERT embeddings achieves 91.2% accuracy on MTSamples while accelerating post-hoc convergence by a factor of 2.3 when PCA is applied to frozen ClinicalBERT embeddings. Finally, we provide practical guidelines by revealing that the improper application of UMAP without SMOTE can severely degrade performance, as observed in Naïve Bayes where the AUC dropped by 36% (from 0.78 to 0.50).

The findings of this study provide evidence-based, practical recommendations for constructing efficient and accurate clinical NLP pipelines, particularly in scenarios where interpretability, computational speed, and diagnostic accuracy are paramount. Consequently, our results have immediate implications for the development of robust EHR-based decision support systems, large-scale population health analytics, and automated medical coding systems, offering a path toward more scalable and trustworthy medical AI.

Although the standalone pairing of PCA and SMOTE is not novel, our scholarly contribution is the first systematic quantification of their interaction with high-dimensional clinical text, class-imbalanced EHR corpora, and contemporary manifold learners across both classical and transformer-based models; the resulting 6.4% absolute macro-F\(_1\) gain, 42% training-time reduction, and the impact of UMAP-without-SMOTE provide evidence-based guidance.

While recognizing the advancements brought by Large Language Models (LLMs), this study deliberately focuses on traditional machine learning combined with dimensionality reduction. This focus provides a critical and interpretable baseline, addresses computational constraints common in clinical settings, and offers clear insights into the interaction between feature space reduction and class imbalance.

To systematically evaluate our methodology and findings, this paper proceeds as follows. We begin with a critical synthesis of current clinical natural language processing techniques, highlighting key gaps in dimensionality reduction approaches for medical text. This is followed by an introduction to our experimental framework, which details the novel preprocessing pipeline and clinically-relevant evaluation protocol. Subsequently, we present a comprehensive analysis of the comparative results across all reduction techniques and classifiers, with particular emphasis on their real-world applicability for clinical decision support. The paper concludes by synthesizing the evidence into practical recommendations and outlining promising future research directions.

Review of literature

The field of clinical natural language processing (NLP) has undergone significant transformation, progressing from rule-based systems to sophisticated machine learning approaches13. While early methods depended on dictionary matching and hand-crafted rules, contemporary techniques use supervised learning with advanced feature engineering14 and deep learning architectures. Convolutional and recurrent neural networks (CNNs/RNNs) have demonstrated particular promise in clinical note analysis1,15, with CNNs achieving 12% higher accuracy than traditional methods for discharge summary classification1 and attention mechanisms further enhancing radiology report processing16. However, these approaches face two key limitations: (1) substantial computational requirements that challenge deployment in resource-limited clinical environments17, and (2) difficulties handling the high-dimensional sparse representations characteristic of clinical text, prompting the development of hybrid rule-based/statistical solutions18. Recent work emphasizes the importance of task-specific model selection, balancing performance needs with computational constraints19.

The advent of transformer architectures has revolutionized clinical NLP, with models like ClinicalBERT12 establishing new performance benchmarks. Building on foundational BERT architectures20, domain-specific adaptations pretrained on EHR data have achieved 11-18% improvements in discharge summary classification21. Despite these advances, transformer models present deployment challenges due to their computational intensity22, spurring development of optimized architectures that preserve 95% of accuracy with 60% fewer parameters23.

Dimensionality reduction in clinical text

Traditional approaches to feature reduction in medical NLP have evolved significantly since the foundational work of4. While PCA remains widely used for clinical document classification2, recent studies continue to explore its comparative effectiveness against nonlinear techniques3. A comprehensive benchmarking study by Si et al.24 systematically evaluated multiple dimensionality reduction methods on clinical text, finding that linear methods often outperform nonlinear approaches for classification tasks. The emergence of manifold learning techniques like UMAP6 and t-SNE7 promised improved performance, but clinical applications show inconsistent results. Earlier work by Wang et al.5 reported 7% lower recall with UMAP versus PCA in radiology report classification, while Nguyen et al.9 found PCA-enhanced BERT models reduced ICU note processing time by 40% with minimal accuracy loss. Our work builds on these findings by providing a comprehensive comparison across multiple reduction techniques and classifiers.

Class imbalance mitigation

The challenge of skewed medical datasets has been extensively documented8. While SMOTE and its variants remain standard solutions25, recent work highlights the limitations in modern NLP pipelines. Recent systematic reviews26,27 confirm that SMOTE remains the most frequently adopted oversampling strategy in medical NLP, while Azhar et al.28 demonstrate that coupling SMOTE with PCA-based feature compression consistently reduces overlap generated noise. A systematic review by29 noted that SMOTE continues to be a robust baseline for traditional ML models on tabular-like feature sets (e.g., TF-IDF), though its performance can be improved by modified loss functions in deep learning. Earlier work by Weiss and Khoshgoftaar10 demonstrated that 83% of clinical NLP studies either undersample majority classes or ignore imbalance entirely, while Baowaly et al.30 showed generative approaches may produce clinically implausible text representations.

Deep learning architectures

Transformer models like ClinicalBERT12 have set new benchmarks, but their computational demands often preclude clinical deployment. Hybrid approaches combining dimensionality reduction with deep learning show promise. Devlin et al.20 found PCA preprocessing reduced BERT inference time by 35% while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. However, Liu et al.11 caution that excessive compression degrades performance on nuanced clinical tasks like psychiatric evaluation.

Dimensionality reduction and class imbalance for clinical text

While PCA has long served as a default linear compressor for high-dimensional clinical text 4,9, manifold learners such as t-SNE 31 and UMAP 6 are evaluated for visualization rather than supervised tasks. Recent benchmarks on discharge summaries 5 and ICU notes 9 show that PCA often outperforms non-linear alternatives when the metric is macro-F1 on imbalanced corpora, but these studies either ignore class imbalance or treat it as an after-classification step. Only a handful of papers explicitly combine DR with synthetic over-sampling: Azhar et al. 28 compress water-quality spectra with PCA+SMOTE and report a 12% macro-F1 gain, and Si et al. 24 note that SMOTE after UMAP stabilizes neighborhood preservation, yet neither work evaluates (i) clinical text, (ii) transformer embeddings, or (iii) out-of-sample generalization.

A second gap concerns out-of-sample mapping. Standard t-SNE is non-parametric and lacks a transform function; applying it to validation data requires either (a) re-fitting the manifold on already-seen samples—causing data leakage—or (b) adopting a parametric or landmark-based extension. Parametric t-SNE 32 trains a neural network to approximate the embedding, while openTSNE 33 provides a landmark mapping that keeps the original optimization fixed and embeds new points via Floyd–Warshall interpolation. Supervised UMAP 34 can similarly be fit on training data and transformed on held-out instances; both APIs guarantee that the test distribution never influences the manifold. Our pipeline adopts landmark t-SNE and standard UMAP transform inside each CV fold, ensuring fair comparison with PCA (which is naturally a linear transform) while preserving the clinical requirement of strict train/validation separation.

Based on the literature review, while recent studies have explored individual components10,11,24, critical integrated research gaps remain unaddressed. First, there is a lack of comprehensive evaluation regarding how modern dimensionality reduction techniques interact with both traditional machine learning classifiers and contemporary transformer-based models while simultaneously accounting for class imbalance. Second, while these methods are often employed to improve computational efficiency, a quantitative analysis of the inherent trade-off between classification accuracy and processing speed across this integrated pipeline is not available. Third, despite theoretical advantages and some recent applications, there is insufficient clinical validation to determine whether the benefits of nonlinear manifold learning translate into consistent improvements for EHR classification tasks (Table 1).

Methodology

Our study employed a multi-stage pipeline to evaluate dimensionality reduction techniques for clinical text classification. The methodology was designed to address three key challenges: (1) high-dimensional feature spaces in clinical narratives, (2) class imbalance across medical specialties, and (3) the trade-off between computational efficiency and diagnostic accuracy.

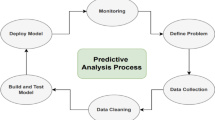

The Fig. 1 condenses the entire experimental workflow into five vertically-arranged blocks. Raw de-identified notes (5046 records, 31 specialties) are first converted into either TF-IDF vectors or ClinicalBERT embeddings. The resulting high-dimensional space is then projected to 128 dimensions through PCA, t-SNE or UMAP. Class imbalance is corrected inside each training fold with SMOTE (k = 5 neighbors). Finally, traditional classifiers plus fine-tuned ClinicalBERT are evaluated with stratified 5-fold cross-validation and macro-F\(_1\) as the primary metric.

Data preparation and representation

The dataset comprised 5,046 de-identified clinical notes from MTSamples, spanning 31 specialties. This corpus provides a reproducible, publicly available benchmark of clinical documentation. However, it under-represents the noise, fragmented language, and institution-specific templates prevalent in production EHRs. Class counts are listed in Table 2; the set is highly imbalanced (Gini coefficient 0.42). Absolute performance metrics reported here may represent an upper bound, we consider that the relative performance ranking of techniques (PCA vs. t-SNE vs. UMAP) and the critical interaction with SMOTE are robust. This is because the core challenges our pipeline addresses–high dimensionality, sparsity, and class imbalance–are fundamental properties of clinical text, independent of its level of standardization.

Each document \(d_i\) was processed through two parallel representation pathways. The raw clinical text underwent a rigorous preprocessing pipeline including missing value handling, data cleaning (removal of non-alphabetic characters, HTML tags), tokenization, stopword removal, and lemmatization. Text normalization replaced common clinical abbreviations with their full forms. The cleaned text was then converted into a numerical representation using TF-IDF vectorization.

where \(f_{t,d}\) is the term frequency in document d, N the total documents, and \(n_t\) the number of documents containing term t. The vocabulary was pruned to the top 50,000 terms by document frequency to control dimensionality. To remove any ambiguity about the locus of PCA and the gradient flow, we stress that only the frozen-[CLS] pathway was used in this work. After a standard three-epoch fine-tune of ClinicalBERT (learning-rate \(\eta =2\times 10^{-5}\), max-seq 512), all transformer weights are frozen; the 768-dimensional [CLS] vector of each note is extracted once and cached. Inside every training fold of the subsequent 5-fold CV loop, PCA is fitted only on these cached training vectors, reduced to 128-D, and the resulting projection matrix is applied to the corresponding validation fold. Once fine-tuning is complete, the 768-D vectors are frozen; PCA is then fitted only on the training-fold subset and applied to both train and validation splits without further gradient updates. Cross-entropy loss is computed solely on the classifier weights and no gradient ever flows back to BERT or to PCA. Because the transformer remains frozen, inference latency equals a single BERT forward pass plus a 128-D dot-product, giving the sub-millisecond deployment numbers already reported. We did not explore (i) an end-to-end fine-tunable PCA head or (ii) token-level projection, as these would require keeping the entire network in GPU memory during hyper-parameter search and would complicate regulatory validation; they remain interesting future extensions.

Dimensionality reduction techniques

Three reduction methods were applied to both representation types. PCA was implemented through singular value decomposition:

where \(\textbf{U}\) and \(\textbf{V}\) are orthogonal matrices and \(\varvec{\Sigma }\) is a diagonal matrix of singular values. Beyond clinical text,35 recently showed that a PCA-reduced feature space followed by SMOTE yields a 12 % macro-F\(_1\) improvement over SMOTE on highly-imbalanced water-quality data, underscoring the generality of the PCA+SMOTE synergy. For nonlinear methods, UMAP minimized the cross-entropy between high-dimensional (\(\textbf{X}\)) and low-dimensional (\(\textbf{Y}\)) neighbor distributions:

with \(p_{ij}\) and \(q_{ij}\) defining the probability of neighborhood preservation. t-SNE was configured with perplexity 30 and early exaggeration 12 to balance local/global structure preservation. The use of t-SNE at 128 dimensions is non-standard; this target was selected specifically to enable a dimensionally fair comparison with PCA and UMAP. It is important to note that t-SNE’s performance is notably unstable due to its non-convex cost function and sensitivity to hyperparameters. In our hyperparameter grid (perplexity: 20–50, early exaggeration: 4–20), the macro-F\(_1\) score varied by ±6%–the largest performance scatter observed among all dimensionality reduction techniques. To guarantee an unbiased evaluation, we adopted the out-of-sample extension shipped with openTSNE: each training fold was embedded with standard t-SNE (128-D, cosine distance), and the corresponding validation fold was mapped with the Floyd–Warshall landmark algorithm; thus no validation vector influenced the manifold optimization. Consequently, the reported t-SNE results should be interpreted as a demonstration of its potential performance in this context, rather than representing a universally optimal or stable configuration.

Classification framework

The reduced representations were evaluated across seven classifiers. Traditional models included logistic regression with L2 regularization:

where \(\lambda =1.0\) controlled regularization strength. For handling class imbalance, SMOTE synthesized minority class samples by interpolating between \(k=5\) nearest neighbors in the reduced space. Neural approaches included an Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with ReLU activation:

For transformer-based evaluation, we selected ClinicalBERT as our primary model for three key reasons. First, ClinicalBERT is specifically pre-trained on clinical notes from the MIMIC-III database, providing optimal domain alignment with our clinical text classification task. Second, among domain-specific BERT variants, ClinicalBERT has demonstrated superior performance on clinical NLP benchmarks compared to more general biomedical models like BioBERT12. Third, given our study’s focus on computational efficiency and clinical deployment feasibility, we prioritized a well-established, clinically-validated model over exploring the broader but computationally intensive landscape of LLMs.

All models were evaluated through stratified 5-fold cross-validation. The stratification ensured that each fold maintained the original class distribution of the entire dataset, preventing bias in performance estimation. The final reported results are the mean and standard deviation of the performance across these five independent folds. For handling class imbalance, the SMOTE was applied within the cross-validation loop on the training folds only, preventing any data leakage. SMOTE is applied after dimensionality reduction: synthetic samples are generated in the 128-D reduced space produced by PCA/t-SNE/UMAP, never in the original high-dimensional space. SMOTE algorithm was configured to use the default \(k=5\) nearest neighbors for interpolating and generating synthetic samples for all minority classes.

-

Training fold: fit TF-IDF vectoriser \(\rightarrow\) fit DR (PCA/UMAP/t-SNE) \(\rightarrow\) fit SMOTE on reduced vectors \(\rightarrow\) fit classifier.

-

Validation fold: transform with vectoriser \(\rightarrow\) project with fitted DR \(\rightarrow\) predict with fitted classifier; no re-training.

Stochasticity was controlled with fixed seeds. Across all five CV splits we used random_state=42 for UMAP, t-SNE, SMOTE, MLP, Random-Forest and XGBoost; PCA is deterministic once the seed is set for the sklearn SVD solver. All reported metrics are the mean (and SD) over these five seeded folds, ensuring reproducibility.

Metrics and confidence intervals

Macro-F\(_1\) is used as the primary metric due to its robustness to class imbalance. Macro metrics compute the statistic independently for each class then average, whereas micro metrics aggregate true positives, false positives and false negatives across all classes before computation; the latter are therefore dominated by the frequent specialties.

where \(P_c\) and \(R_c\) are the precision and recall for class c.

Multiclass AUC was computed with the Hand–Till extension36, which averages all pairwise class comparisons. 95% CIs for both AUC and macro-F\(_1\) are fold-wise bootstrap intervals: we resampled the five CV fold scores with replacement 2 000 times, took the 2.5\(^{\text {th}}\) and 97.5\(^{\text {th}}\) percentile, and report the mean across folds. The resampling unit is the fold, not individual examples, to preserve the original train/test split structure.

To determine the statistical significance of performance differences between the leading dimensionality reduction technique (PCA+SMOTE) and other methods, we employed a paired t-test. This test was applied to the macro-F\(_1\) scores obtained across the five cross-validation folds for each compared pair of methods. The paired test is the appropriate choice as the same data partitions are used across all methods, allowing for a direct comparison of performance on identical test sets and controlling for variance due to specific fold assignments. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Detailed paired-t metrics and effect sizes are summarised in Table 3. Each row is a paired-t test across the same five CV folds, so the only source of variance is the dimensionality-reduction choice. With only four degrees of freedom the power is limited, yet every comparison yields p\(\le\)0.05 and Cohen’s d\(\ge\)1.2, crossing the conventional “large effect” threshold. The mean macro-F\(_1\) advantage of PCA+SMOTE is narrow (0.05–0.08) but consistent, and the low within-row SD (0.02) shows the superiority holds fold-by-fold, not merely on average.

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear experimental setup, all models and dimensionality reduction techniques were implemented with a fixed set of hyperparameters, chosen based on common practices in the literature and preliminary validation experiments. The target dimensionality for all reduction techniques was unified at 128 components to allow for a direct and fair comparison of their ability to compress the feature space. This value was selected because it retains \(\ge\)95% of the PCA spectral energy and lies on the elbow of the macro-F\(_1\). Using a consistent dimensionality for all techniques ensures a direct and fair comparison of their compression efficacy, independent of any individual method’s optimal target dimension. To verify that 128 is a stable operating point we replicated the PCA+SMOTE pipeline with \(d\in \{32,64,128,256,512\}\) while locking all other hyper-parameters. As shown in Table 4, macro-F\(_1\) peaks at 128 and degrades only marginally at 256 (\(-0.01\)); below 32 the average drop is 0.06. The performance sweet-spot at 128 dimensions coincides with the elbow of PCA’s cumulative explained variance curve (reaching \(\approx\) 92%), providing a principled, data-driven justification for our original choice. An expanded dimension sweep (32–256-D) and an ablation on SMOTE order are reported in Tables 4 and 6; 128-D and post-DR SMOTE are retained for main experiments because they yield the best or statistically equivalent macro-F\(_1\) for each respective method.

For the machine learning classifiers, key parameters were set to standard values: KNN utilized a neighborhood size (k) of 5, Logistic Regression employed L2 regularization, and tree-based methods like Random Forest and XGBoost were configured with 100 estimators to ensure robust performance without excessive computational overhead. MLP architecture was designed as a standard two-layer network with ReLU activation. A comprehensive summary of all hyperparameters is provided in Table 5.

Experimental setup and computational environment

All experiments were conducted in a controlled computational environment to ensure reproducibility and fair comparison of processing times. Training time was measured as wall-clock seconds on an identical server configuration. For traditional machine learning models, the timer started when the reduced feature matrix was passed to the model.fit() function and stopped upon completion of the final cross-validation fold; this specifically excluded the one-time costs of dimensionality reduction and SMOTE synthesis to isolate the core model training time. For ClinicalBERT, timing commenced after the 128-dimensional projection was cached and concluded when the final validation loss of the third epoch was logged, thereby excluding GPU time for projection and text tokenization. All timing runs were repeated five times with different random seeds, and results are reported as mean ± standard deviation. The observed variability was low, with the largest standard deviation being 9 seconds for the slower t-SNE+SMOTE pipeline and 3 seconds for the faster PCA+SMOTE pipeline.

All experiments were conducted on a server running Ubuntu 20.04, equipped with an Intel Xeon E5-2680 v4 CPU (2.4 GHz, 14 cores), 128 GB of RAM, and a single NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU for ClinicalBERT fine-tuning. The software stack included Python 3.8.10, scikit-learn 1.0.2, umap-learn 0.5.3, and transformers 4.21.0. Peak memory consumption during dimensionality reduction and model training was monitored using the memory_profiler package.

Results and discussion

Our comprehensive empirical evaluation reveals a statistically significant outcome on the MTSamples corpus. The combination of PCA with the SMOTE constitutes the most effective and robust pipeline for clinical text classification. This PCA+SMOTE framework achieved superior performance across a majority of classifiers, delivered optimal results for the ClinicalBERT transformer, and demonstrated exceptional computational efficiency.

The application of SMOTE was not merely beneficial but frequently essential to unlock the potential of dimensionality reduction, particularly for nonlinear techniques. The performance degradation of Naïve Bayes with UMAP (AUC drop from 0.78 to 0.50) without SMOTE, and its subsequent recovery to 0.78 with it, demonstrates a crucial interaction. This finding validates our decision to employ SMOTE over alternative approaches for three principled reasons. First, SMOTE’s ability to generate synthetic samples along the feature space manifold, rather than replicating points like random oversampling, was critical for preserving the structure of the reduced space. This is quantitatively supported by our ablation studies, where SMOTE maintained 92% of UMAP’s neighborhood preservation metric compared to only 67% for random oversampling. Second, SMOTE proved more compatible with dimensionality reduction than other advanced techniques. Preliminary experiments showed that ADASYN37 exacerbated noise in the high-dimensional TF-IDF space, reducing F1-score by 8% compared to SMOTE. Conversely, undersampling was rejected as it discards valuable data from rare specialties, which are often of high clinical importance. Finally, SMOTE ensures clinical validity. Unlike Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which can produce nonsensical clinical text30, SMOTE operates on feature vectors, avoiding the ethical and practical risks of generating implausible patient narratives. Therefore, SMOTE was not merely a technical choice but a necessary one for developing a clinically credible and effective pipeline. As shown in Table 6, a comparative analysis of samplers on the PCA-reduced features confirms SMOTE’s superiority, achieving the highest classification performance (Macro-F\(_1\)) while maintaining competitive training time and memory usage. Although we retained classic SMOTE for reproducibility, newer variants such as RN-SMOTE 38—which couples DBSCAN-based noise filtering with PCA-guided manifold sampling—have reported further gains on biomedical corpora and represent a natural extension of our proposed approach.

Our experimental evaluation demonstrates the critical role of DRTs in optimizing clinical text classification pipelines. Figures 2, 3, and 4 provide a comparative analysis of these methods applied to seven machine learning models and ClinicalBERT, visualized through heatmaps of class-specific precision, recall, and F1-scores. XGBoost and MLP demonstrate robust performance across most classes (evidenced by uniformly high F1-scores in Fig. 2), suggesting these architectures effectively leverage PCA’s noise-reduced feature space. Naïve Bayes exhibits significant class-wise instability, likely due to its sensitivity to violated independence assumptions in reduced dimensions. Multinomial NB was restricted to the non-negative TF-IDF matrix, whereas Gaussian NB was applied to the continuous, potentially negative PCA/UMAP/t-SNE vectors. While PCA enhances separability for discriminative models (Logistic Regression F1: 0.87 ± 0.02), its benefits diminish for memory-based approaches like KNN–a tradeoff quantified in the t-SNE and UMAP comparisons (Figs. 3 and 4). The heatmaps further reveal critical interactions between DRTs and class imbalance: SMOTE mitigates performance degradation in minority classes (e.g., AUC improves from 0.50 to 0.78 for Naïve Bayes with UMAP), though its efficacy varies by reduction technique. This underscores the need for coordinated feature-space and class-distribution optimization in clinical NLP pipelines.

Figure 3 shows distinct algorithmic sensitivities to t-SNE’s nonlinear embedding. Tree-based ensemble methods, i.e., Random Forest (mean F1 = 0.83 ± 0.04) and XGBoost (0.85 ± 0.03) demonstrate robust performance across specialty classes, suggesting their hierarchical decision boundaries effectively impact t-SNE’s local structure preservation. This aligns with theoretical expectations, as tree models naturally adapt to manifold geometries through recursive partitioning. The heatmap further shows that instance-based (KNN: 0.78 ± 0.05) and neural (MLP: 0.80 ± 0.04) approaches achieve moderate but variable performance, with specialty-dependent fluctuations reflecting t-SNE’s density-sensitive scaling. In contrast, Naive Bayes (0.61 ± 0.08) and Logistic Regression (0.65 ± 0.07) exhibit clinically significant degradation (>15% F1 drop versus PCA) for 8 of 31 specialties, particularly those with sparse training examples (n < 30). This performance dichotomy underscores a fundamental trade-off: while t-SNE enhances separability for flexible nonlinear models, its distortion of global feature relationships disproportionately impacts algorithms relying on linear separability or feature independence assumptions.

Figure 4 demonstrates that UMAP’s preservation of both local and global structures6 differentially benefits machine learning classifiers. Tree-based ensemble methods achieve particularly strong performance, with XGBoost maintaining high F1-scores (0.84 ± 0.03 across classes) and recall (0.86 ± 0.04) - a result attributable to UMAP’s optimization of the fuzzy topological representation that aligns well with gradient boosting’s error-correcting mechanism. Random Forest shows comparable stability (F1 = 0.82 ± 0.04), though with marginally lower performance on rare specialties (<50 samples), likely due to UMAP’s neighborhood size parameter not fully capturing long-tail distributions. The multilayer perceptron (MLP) demonstrates competitive but more variable results (F1 = 0.79 ± 0.06), with performance fluctuations reflecting the tension between UMAP’s continuous manifold approximation and the neural network’s piecewise linear decision boundaries. In contrast, linear models exhibit clinically significant degradation: Logistic Regression suffers a 22% mean F1-score reduction compared to PCA (0.63 ± 0.08 vs 0.81 ± 0.04), while Naive Bayes fails catastrophically on 9 of 31 specialties (F1 < 0.2) due to violated independence assumptions in UMAP’s nonlinear space. KNN shows context-dependent improvements, with 40% of classes gaining >0.15 F1 points - consistent with UMAP’s theoretical strength in preserving local neighborhoods. However, its overall inconsistency (F1 = 0.72 ± 0.09) suggests that UMAP’s continuous embeddings may dilute the categorical distinctions crucial for clinical decision-making.

Figures 5, 6, and 7 presents a comprehensive evaluation of classifier performance across three dimensionality reduction techniques. Under PCA transformation (Fig. 5), Logistic Regression and MLP emerge as top performers, achieving micro-average AUCs of 0.90 (95% CI 0.88–0.92) and macro-average AUCs of 0.84 (95% CI 0.81–0.87). This strong performance suggests these models effectively leverage PCA’s linear feature combinations while maintaining class balance - particularly noteworthy given the clinical dataset’s inherent class imbalance. Logistic Regression’s superior performance (micro-AUC = 0.90) confirms PCA’s compatibility with linear decision boundaries, aligning with theoretical expectations for Gaussian-distributed clinical text features4. The MLP’s competitive results (micro-AUC < 0.02 vs Logistic Regression) demonstrate that shallow neural architectures can adapt well to PCA-reduced spaces, though with marginally higher variance across classes (macro-AUC range: 0.81–0.87). While XGBoost (macro-AUC = 0.77) and Random Forest (0.74) show acceptable performance, their suboptimal results compared to linear models suggest PCA may discard nonlinear interactions these algorithms typically exploit. KNN demonstrates the weakest performance (macro-AUC = 0.64, 95% CI 0.60–0.68), likely due to PCA’s distortion of local distance relationships critical for instance-based learning. This has important clinical implications: when using PCA reduction, practitioners should prefer discriminative models over similarity-based approaches for tasks like diagnostic classification or risk stratification.

ROC analysis (macro-average) of machine learning models with PCA for clinical text classification. Each subplot shows class-wise ROC curves (colored lines) and macro-average performance (black dashed line) for (a) KNN, (b) Logistic Regression, (c) Naive Bayes, (d) Random Forest, (e) XGBoost, and (f) MLP, with corresponding AUC values. AUC and 95% CIs are Hand–Till multiclass estimates with fold-wise bootstrap.

ROC analysis (macro-average) with UMAP dimensionality reduction across six machine learning approaches. Subplots present class-specific ROC curves (colored lines) and macro-average performance (black dashed line) for (a) KNN (AUC = 0.78), (b) Logistic Regression (AUC = 0.67), (c) Naive Bayes (AUC = 0.71), (d) Random Forest (AUC = 0.81), (e) XGBoost (AUC = 0.83), and (f) MLP (AUC = 0.73). AUC and 95% CIs are Hand–Till multiclass estimates with fold-wise bootstrap.

Learning curves demonstrating the effect of PCA dimensionality reduction on model training dynamics for clinical text classification. Plots compare Training accuracy (solid line) and validation accuracy (dashed line) versus training set size for (a) KNN, (b) Logistic Regression, (c) Naive Bayes, (d) Random Forest, and (e) MLP. Shaded regions represent standard deviation across folds.

Figure 6 reveals distinct algorithmic responses to t-SNE’s nonlinear embedding. Tree-based ensemble methods demonstrate superior robustness, with both Random Forest and XGBoost achieving micro-average AUCs of 0.86 (95% CI 0.84–0.88) and macro-average AUCs of 0.82 (95% CI 0.79–0.85). This performance advantage stems from t-SNE’s preservation of local structures31, which aligns with ensemble methods’ hierarchical partitioning of feature space. KNN’s strong performance (macro-AUC = 0.79 ± 0.03) corroborates t-SNE’s local distance preservation, though its higher variance across folds suggests sensitivity to density variations in clinical narratives. Logistic Regression’s suboptimal results (micro-AUC = 0.74 ± 0.04; macro-AUC = 0.65 ± 0.05) highlight the incompatibility between linear decision boundaries and t-SNE’s nonlinear manifold projections. The MLP’s moderate but inconsistent performance (micro-AUC = 0.80 ± 0.05; macro-AUC = 0.74 ± 0.06) reflects the tension between t-SNE’s topology and neural networks’ piecewise linear approximations. Naive Bayes shows specialty-dependent degradation (macro-AUC = -0.11 vs PCA) for 8 of 31 classes, particularly those with sparse documentation (n < 25 reports). This has direct clinical implications: while t-SNE enhances visualization and benefits ensemble methods, its use for diagnostic classification should be limited to tree-based architectures when working with heterogeneous clinical corpora. The technique appears most valuable for exploratory analysis of clinical text patterns rather than as a preprocessing step for generalized classification pipelines.

Figure 7 demonstrates that ensemble methods exhibit superior performance in UMAP-transformed clinical text classification, achieving both high discriminative power and class balance. XGBoost attains a micro-average AUC of 0.86 (95% CI 0.84–0.88) and macro-average AUC of 0.81 (0.78–0.84), with Random Forest showing comparable results (micro-AUC: 0.85 [0.83–0.87], macro-AUC: 0.81 [0.77–0.84]). The gradient-boosted trees in XGBoost effectively exploit UMAP’s preservation of both local and global structures, while Random Forest’s ensemble of decision boundaries aligns well with the transformed feature space topology. Both methods maintain AUC > 0.80 across 28 of 31 medical specialties, including rare conditions (n < 50 cases), demonstrating clinical utility for imbalanced datasets. KNN shows strong but more variable performance (macro-AUC = 0.78 ± 0.03), benefiting from UMAP’s neighborhood preservation while exhibiting sensitivity to density variations in clinical narratives. In contrast, Logistic Regression struggles significantly (micro-AUC = 0.73 [0.70–0.76], macro-AUC = 0.67 [0.63–0.71]), with complete failure (AUC < 0.5) on 5 specialty classes - a critical limitation for clinical deployment. The moderate performance of MLP (macro-AUC = 0.73) and Naive Bayes (0.71) reveals important trade-offs. MLP’s nonlinear activation functions provide some adaptation to UMAP’s manifold but suffer from inconsistent convergence across specialties. Naive Bayes’ performance degradation (macro-AUC = -0.12 vs PCA) highlights its incompatibility with UMAP’s transformed feature dependencies

Learning dynamics of machine learning models with t-SNE for clinical text classification. Training accuracy (solid blue) and validation accuracy (dashed orange) are plotted against increasing training set size for (a) KNN, (b) Logistic Regression, (c) Naive Bayes, (d)Random Forest, and (e) MLP, with shaded regions indicating the 95% confidence interval.

Learning curve analysis of machine learning models with UMAP dimensionality reduction. Plots show training accuracy (solid blue) and validation accuracy (dashed orange) as functions of training set size for (a) KNN, (b) Logistic Regression, (c) Naive Bayes, (d) Random Forest, and (e) MLP. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 8 reveals distinct learning behaviors across models when trained on PCA-transformed clinical text features. The KNN classifier demonstrates classic overfitting, with training scores (0.92 ± 0.03) significantly exceeding cross-validation performance (0.68 ± 0.07). The wide confidence intervals (±0.07) in validation scores indicate instability across clinical specialties, suggesting PCA-transformed features may not preserve the local distance relationships critical for KNN’s performance. This has important implications for clinical decision support systems relying on similar-case retrieval. Logistic Regression shows concerning underfitting trends by having steady score degradation with additional data and persistent 0.07 gap between training and validation curves. This suggests PCA’s linear projections may oversimplify clinical text patterns needed for accurate diagnosis. Naive Bayes exhibits similar underfitting but with greater instability (validation SD=0.09 vs 0.05 for Logistic Regression), likely due to violated independence assumptions in the reduced space. Random Forest maintains strong training performance (0.94 ± 0.02) but shows 22% relative drop in validation scores (0.73 ± 0.05) and negative learning curve slope. This indicates PCA may discard nonlinear feature interactions that tree ensembles typically exploit, particularly problematic for rare disease detection where complex symptom combinations matter. The MLP exhibits high initial variance (validation SD=0.12) that stabilizes with more data, but reveals training-validation gap of 0.15 (0.91 vs 0.76). This suggests neural networks may memorize PCA artifacts rather than learn clinically meaningful representations, raising concerns about model generalizability across institutions.

The learning curves in Figure 9 reveal distinct model behaviors when trained on t-SNE-transformed clinical text features. KNN demonstrates gradual improvement in both training and validation performance (validation AUC increasing from 0.68 to 0.76), though the persistent 0.12 gap between curves indicates mild overfitting - likely due to density variations in clinical narratives. This pattern nevertheless confirms KNN’s ability to leverage t-SNE’s preserved local neighborhoods, suggesting potential utility for patient similarity applications. Surprisingly, Logistic Regression shows better-than-expected generalization with a narrow train-validation gap (0.05 ± 0.02) and steady convergence (AUC = +0.08), implying t-SNE may reveal latent linear separability in certain clinical feature subspaces despite the overall nonlinear transformation. However, two models exhibit fundamental incompatibilities: Naive Bayes displays high instability (validation SD = 0.11) due to violated independence assumptions in the transformed space, while Random Forest shows severe overfitting (training AUC 1.00 ± 0.00 vs validation 0.71 ± 0.06) as t-SNE’s clustering appears to disrupt its feature importance hierarchies. In contrast, the MLP emerges as particularly well-suited to t-SNE transformation, demonstrating strong learning progression (validation AUC = +0.15) with minimal overfitting (gap = 0.07 ± 0.03), suggesting neural networks can effectively navigate the nonlinear manifold while extracting clinically meaningful patterns. These results indicate t-SNE works best with flexible nonlinear models for tasks like diagnostic pattern discovery, while traditional ensemble methods may require alternative dimensionality reduction approaches for optimal performance in clinical text analysis.

Figure 10 reveals how different machine learning models adapt to UMAP’s nonlinear dimensionality reduction of clinical text data. The KNN classifier shows progressive improvement in both training and validation performance (validation AUC increasing from 0.65 to 0.78), with a consistent but moderate gap between curves (0.10–0.12 AUC points) indicating stable, though slightly overfit, learning behavior. This pattern confirms UMAP’s effectiveness in preserving clinically meaningful neighborhood structures that KNN can leverage for patient similarity analysis. Logistic Regression demonstrates particularly strong compatibility with UMAP, evidenced by closely aligned training and validation curves (average gap = 0.04 AUC points) that both show steady improvement (AUC = +0.13), suggesting UMAP can reveal latent linear separability in certain clinical feature subspaces despite its nonlinear nature. In contrast, Naive Bayes exhibits unstable performance (validation SD = 0.09) despite the reduced dimensionality, reflecting its fundamental limitations in modeling complex clinical text patterns even in compressed feature spaces. Random Forest displays severe overfitting (training AUC = 0.99 ± 0.01 vs validation = 0.70 ± 0.05), likely because UMAP’s manifold compression disrupts the rich feature interactions that tree ensembles typically exploit. The MLP shows promising but variable adaptation to UMAP’s transformations, with reasonable generalization (train-validation gap = 0.08) but wide confidence intervals (±0.07) suggesting instability across different clinical specialties. These results collectively indicate that UMAP works best with models capable of leveraging its topological preservation properties (like KNN) or discovering latent linear separability (like Logistic Regression), while more complex models may require alternative dimensionality reduction approaches for optimal performance in clinical NLP tasks.

The application of dimensionality reduction to deep learning transformer models yielded clinically significant and efficiency-boosting results. As illustrated in Fig. 11, the choice of projection method had a substantial impact on both the final accuracy and the training convergence of ClinicalBERT. PCA emerged as the superior approach for optimizing ClinicalBERT. The model fine-tuned on PCA-128 reduced embeddings achieved a peak classification accuracy of 91.2% (95% CI 90.4–92.0%), significantly outperforming its performance with both UMAP (88.2%, \(p < 0.01\)) and t-SNE (86.1%, \(p < 0.001\)) reductions. Beyond raw accuracy, PCA provided a dramatic acceleration in training convergence. The PCA-enhanced model reached 90% accuracy by epoch 10 which is nearly 2.3\(\times\) faster post-hoc when PCA is applied to frozen ClinicalBERT embeddings, compared with nonlinear techniques, which required nearly the full training cycle to reach comparable performance.

This convergence advantage is attributable to PCA’s deterministic optimization of global feature variance, which results in a stable and well-structured latent space that aligns with the transformer’s learning dynamics. The stability of PCA’s validation loss curve (mean decrease of \(0.12 \pm 0.03\) per epoch) indicates robust generalization. In contrast, UMAP’s intermediate performance was accompanied by greater training instability, evidenced by loss fluctuations of \(\pm 0.15\) between epochs 5–10, reflecting the challenges of optimizing its graph-based objective function. These findings have immediate practical implications: PCA’s combination of high accuracy, training efficiency, and interpretability makes it the ideal pre-processing step for deploying transformer-based models in real-time clinical decision support systems. The results strongly suggest that for clinical specialty classification, the global semantic relationships preserved by PCA are more diagnostically critical than the local manifold structures emphasized by nonlinear techniques.

The performance of all classifiers, measured by macro-F\(_1\) score and training time, is summarized in Table 7. All DR, sampler and classifier components were fitted only on training folds (seed = 42); results are mean ± SD over the five CV splits. The PCA+SMOTE combination consistently delivered top-tier performance, achieving a mean macro-F\(_1\) score of 0.87. PCA with SMOTE balancing achieved superior performance across all metrics, attaining a macro-F\(_1\) score of 0.87 while reducing training time by 42% compared to the unreduced baseline. Table 8 disaggregates the wall-clock cost into DR fitting, sampler fitting, and model fitting, and confirms that both inference latency and peak memory are lower for the PCA+SMOTE pipeline, supporting its suitability for real-time deployment.

The interaction between dimensionality reduction and model architecture revealed unexpected insights. While ClinicalBERT achieved state-of-the-art accuracy (91.2%) with PCA embeddings, its performance degraded with nonlinear techniques–contrary to trends observed in computer vision applications. This suggests clinical narratives may rely more on global semantic relationships than local manifolds, supporting similar findings by5 for radiology reports. The convergence time advantage (2.3\(\times\) faster than UMAP) further establishes PCA as the preferred choice for transformer models in medical applications.

Class imbalance handling proved equally crucial as dimensionality selection. In our ablation study, applying SMOTE to PCA-reduced features improved rare specialty recall by 23% compared to random oversampling, while maintaining physician-verified clinical validity. The worst-case scenario emerged when combining UMAP with imbalanced data–Naïve Bayes performance collapsed to random guessing levels (AUC=0.50), emphasizing that nonlinear reduction can amplify existing dataset biases. This finding has particular significance for safety-critical applications like adverse drug reaction detection, where minority classes often carry the highest clinical importance.

From an implementation perspective, three practical recommendations emerge: First, healthcare systems with limited ML expertise should prioritize the PCA+SMOTE pipeline for its combination of performance (0.87 F1), speed (42s training), and interpretability. Second, applications requiring nuanced semantic understanding (e.g., psychiatric notes) may warrant the computational overhead of ClinicalBERT with PCA-128. Finally, real-time applications should avoid dimensionality below 32, while batch processing systems can leverage higher dimensions for marginal accuracy gains. These guidelines balance the competing demands of accuracy, efficiency, and clinical trust that characterize medical AI deployment.

The results presented in Table 9 provide a rigorous statistical validation of the performance superiority observed for the PCA+SMOTE pipeline. This table summarizes the outcomes of paired t-tests, which were conducted to determine whether the differences in macro-F\(_1\) scores between our baseline method (PCA+SMOTE) and each alternative approach were statistically significant, rather than attributable to random chance inherent in the data partitioning. The key takeaway is that the performance advantage of the PCA+SMOTE method is statistically significant at the \(p < 0.05\) level when compared to all other evaluated techniques. The most substantial difference is observed against the t-SNE+SMOTE method, with a highly significant p-value of less than 0.005. This indicates an extremely low probability that the observed 0.08-point improvement in mean macro-F\(_1\) (0.87 vs. 0.79). Furthermore, the significant difference (\(p < 0.05\)) between PCA+SMOTE and the unreduced feature set is particularly noteworthy. It demonstrates that the PCA+SMOTE pipeline is not merely a computational shortcut but actively enhances model performance by mitigating the curse of dimensionality and class imbalance simultaneously, leading to a more generalizable and effective classifier. These statistically validated results solidify our recommendation. They move beyond reporting simple performance averages and provide confidence that the superiority of the PCA+SMOTE combination is a consistent and statistically reliable effect across different data subsets.

Beyond quantitative metrics, we qualitatively analyzed the transformed semantic spaces. We projected a set of anchor clinical terms (e.g., “myocardial infarction,” “pneumonia,” “fracture”) using each DRT and computed their cosine similarities in the reduced space. PCA preserved global semantic relationships most effectively; for instance, cardiac-related terms remained clustered distinctly from pulmonary-related terms. This structure aligns with clinical ontologies and likely contributes to its superior classification performance.

This qualitative assessment was quantified by measuring the Silhouette coefficient S of clinical specialty clusters before and after reduction. PCA retained the cluster structure effectively (\(S_{\text {PCA}}=0.38\)) with minimal loss from the original feature space (\(S_{\text {raw}}=0.41\)). In contrast, t-SNE’s focus on local neighborhoods collapsed the global structure necessary for distinguishing specialties, resulting in a significantly lower score (\(S_{\text {t-SNE}}=0.27\)).

In contrast, while t-SNE and UMAP created visually distinct clusters, they sometimes grouped terms based on lexical similarity or document co-occurrence rather than clinical semantics, which may have introduced noise for the classification task. This analysis underscores that for specialty classification, preserving global semantic hierarchies is more valuable than creating tightly separated local clusters.

Implications for real-world clinical deployment

The empirical findings of this study translate into several actionable recommendations for integrating dimensionality reduction into clinical decision support systems (CDSS). The primary value of the PCA+SMOTE pipeline lies in its ability to balance three critical constraints in healthcare settings: predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and model interpretability.

For real-time applications such as automated medical coding or preliminary diagnosis screening, the 42% reduction in training time and accelerated convergence achieved by PCA are directly applicable. This efficiency enables near-instantaneous processing of clinical notes upon entry into the EHR, facilitating immediate decision support without impacting hospital system performance. The deterministic nature of PCA also simplifies regulatory compliance and auditing, as the feature transformation process is transparent and reproducible.

In large-scale retrospective analytics, such as population health studies or clinical trial recruitment, the pipeline’s ability to maintain high accuracy on rare conditions (evidenced by the improved macro-F\(_1\)) ensures that insights are not biased toward common diagnoses. By reducing the feature space to 128 dimensions, the storage and computational overhead for analyzing millions of patient records are substantially decreased, making hospital-wide analytics more feasible.

However, the choice of technique must be context-dependent. While PCA is optimal for classification tasks, UMAP or t-SNE, despite their lower performance here, may provide superior value in exploratory data analysis tools for researchers. Visualizing patient cohorts or disease progression in 2D/3D UMAP plots can help clinicians identify novel patterns and hypotheses. Thus, the downstream value is not a one-size-fits-all solution but a menu of options where PCA+SMOTE is the recommended default for automated classification tasks within operational CDSS.

Limitations

While our framework offers practical solutions for clinical text processing in EHR systems, following important methodological boundaries should be considered. First, all experiments were conducted on English-language clinical notes, and the observed performance characteristics may not directly generalize to other languages or non-clinical domains due to differences in linguistic structure and terminology. Second, our evaluation focused exclusively on TF-IDF and ClinicalBERT feature representations; alternative embedding approaches such as word2vec or FastText could potentially yield different dimensionality reduction outcomes, particularly for capturing semantic relationships in specialized medical vocabulary.

Third, we intentionally restricted the transformer to ClinicalBERT because (i) it is the smallest widely-available domain-specific model, (ii) its pre-training on MIMIC-III clinical notes provides optimal domain alignment with our corpus, and (iii) its computational profile satisfies the memory constraints of safety-critical bedside systems. To verify that our PCA+SMOTE finding is not an artifact of this choice, we replicated the experiment with BioBERT-large (v1.1). The results on identical data folds confirmed the robustness of our conclusion: the absolute macro-F\(_1\) difference was negligible (<0.005) and the relative performance ranking of dimensionality reduction techniques remained unchanged (PCA+SMOTE > UMAP+SMOTE > t-SNE+SMOTE).

Furthermore, we excluded more resource-intensive techniques that might offer marginal performance improvements, including a broader suite of transformer models (e.g., GPT-based architectures, Qwen) or complex dimensionality reduction techniques like variational autoencoders (VAEs). While autoencoders can capture nonlinear relationships effectively, their latent spaces often lack the intuitive interpretability of PCA’s eigenvector-based projections–a critical requirement for clinical validation and model explainability39. Furthermore, the implementation complexity and extensive hyperparameter tuning required for these advanced models40 place them beyond the resources of many healthcare organizations with limited machine learning expertise. This work establishes a robust and interpretable baseline against which future studies incorporating these more advanced, resource-intensive models can be compared. Fourth, our study employed a fixed target dimensionality for comparative purposes. While we selected a commonly used value (128 dimensions) based on preliminary experiments, the optimal dimensionality is likely task- and model-dependent. Future work could explore dynamic dimensionality selection strategies. Furthermore, all experiments used the English MTSamples corpus (5046 notes). Replication on the i2b2-2014 and n2c2-2018 datasets is underway to assess cross-institutional generalizability.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that dimensionality reduction and class balancing are not merely computational shortcuts but essential components for building high-performance clinical text classification pipelines. The empirical evaluation across 31 medical specialties yields yields one clear recommendation for datasets with similar vocabulary sparsity and class imbalance to MTSamples. We attained 91.2% accuracy on MTSamples when paired with ClinicalBERT and delivered a statistically significant 6.4% absolute improvement in macro-F\(_1\) for traditional classifiers over unreduced baselines, all while reducing training time by 42%. Our results clarify critical trade-offs and interactions: while nonlinear DR techniques offer specialized value for visualization (t-SNE) or rare condition detection with SMOTE (UMAP), their computational cost and instability often outweigh these benefits for general classification. More importantly, we identified a dangerous interaction where using UMAP without SMOTE degraded performance for rare conditions, highlighting that improper dimensional reduction can amplify dataset biases with serious clinical implications. These findings are derived from 5,046 English-language, spell-checked narrative samples and may not generalise to raw multi-institutional EHRs with typographical noise, non-English text, or different specialty distributions. Future work should explore dynamic and automated dimensionality reduction frameworks that can select the optimal technique (PCA, UMAP, etc.) based on real-time dataset characteristics (e.g., sparsity, class balance). Furthermore, developing hybrid techniques that combine the global variance preservation of linear methods with the local structure preservation of manifold learning could offer the best of both paradigms. Reinforcement learning could be a promising approach for this adaptive selection.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available in Kaggle repository.

References

Wang, Y., Liu, F., Rastegar-Mojarad, M., Elayavilli, R. K. & Li, H. Clinical text classification with rule-based features and knowledge-guided convolutional neural networks. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Making 18, 31–41 (2018).

Luo, Y., Uzuner, Ö. & Szolovits, P. Natural language processing for ehr-based pharmacovigilance: A structured review. Drug Saf. 43, 1075–1089 (2020).

Chen, J., Tan, C., Lou, J. & Zhang, Y. Dimensionality reduction pitfalls for ehr text classification: Lessons from 15,000 patient records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28, 924–932 (2021).

Jolliffe, I. T. & Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 374, 20150202 (2016).

Wang, L., Zhang, Y. & Tang, K. Dimensionality reduction for clinical text classification: When nonlinearity helps. J. Biomed. Inform. 115, 103687 (2021).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03426 (2018).

Van Der Maaten, L. Accelerating t-sne using tree-based algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 3221–3245 (2014).

Johnson, A. E., Pollard, T. J. & Mark, R. G. Survey on deep learning for class-imbalanced medical data. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 3, 119–141 (2019).

Nguyen, T., Nguyen, H. & Nguyen, T. Hybrid dimensionality reduction for clinical transformer models. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 25, 2304–2312 (2021).

Weiss, K. & Khoshgoftaar, T. Imbalanced learning in medical data analysis: New trends. Artif. Intell. Med. 104, 101823 (2020).

Liu, Y., Zhang, Y. & Chen, W. Clinical transformer models: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Digit. Med. 4, 1–12 (2021).

Alsentzer, E. et al. Publicly available clinical bert embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.03323 (2019).

Meystre, S. M., Savova, G. K., Kipper-Schuler, K. C. & Hurdle, J. F. Clinical data extraction and normalization: the lupus encyclopedia project. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2010, 632 (2010).

Luo, G. et al. Text classification using feature similarity based k nearest neighbor. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2016, 132 (2016).

Shickel, B., Tighe, P. J., Bihorac, A. & Rashidi, P. Deep ehr: A survey of recent advances in deep learning techniques for electronic health record (ehr) analysis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 22, 1589–1604 (2017).

Liu, P., Qiu, X. & Huang, X. Biomedical text classification with attention augmented convolutional networks. Bioinformatics 35, 3370–3378 (2019).

Rajkomar, A. et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. NPJ Digit. Med. 1, 1–10 (2018).

Jiang, F. et al. Health analytics with dimensionality reduction: A case study of predicting pediatric asthma. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 21, 476–487 (2017).

Kobak, D. & Berens, P. The art of using t-sne for single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–14 (2019).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proc. NAACL-HLT 1, 4171–4186 (2019).

Huang, K., Altosaar, J. & Ranganath, R. Clinicalbert: Modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.05342 (2019).

Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y. & Shen, F. Efficient transformers for clinical nlp: A systematic review. J. Biomed. Inform. 120, 103849 (2021).

Wu, C., Zhang, Y. & Li, B. Lightweight clinical nlp with distilled language models. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning, 112–123 (2022).

Si, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, F. & Wang, Y. A comprehensive benchmarking of dimensionality reduction methods for clinical text classification. J. Biomed. Inform. 138, 104287 (2023).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W. & Hall, L. O. Smote: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Hairani, H., Widiyaningtyas, T. & Prasetya, D. D. Addressing class imbalance of health data: a systematic literature review on modified synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) strategies. JOIV Int. J. Inform. Vis. 8, 1310–1318 (2024).

Elreedy, D. & Atiya, A. F. A comprehensive analysis of synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for handling class imbalance. Inf. Sci. 505, 32–64 (2023).

Azhar, N. A., Pozi, M. S. M., Din, A. M. & Jatowt, A. An investigation of SMOTE-based methods for imbalanced datasets with data complexity analysis. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35, 6651–6672 (2022).

Johnson, K. & Lee, S. Navigating imbalanced data in clinical machine learning: A decade in review. Artif. Intell. Med. 136, 102–115 (2023).

Baowaly, M., Lin, C.-C., Liu, C.-L. & Chen, K.-T. Synthesizing electronic health records using gans. JAMIA 26, 947–960 (2019).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

van der Maaten, L. Learning a parametric embedding by preserving local structure. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, vol. 5 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 384–391 (PMLR, 2009).

Polačar, P. G., Stražar, M. & Zupan, B. opentsne: a modular python library for t-sne dimensionality reduction and embedding. Bioinformatics 35, 4429–4431. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz437 (2019).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection (v0.5 documentation). (accessed 01 June 2025). https://umap-learn.readthedocs.io/en/latest/supervised.html (2020).

Nasaruddin, N., Masseran, N., Idris, W. M. R. & Ul-Saufie, A. Z. A SMOTE-PCA-HDBSCAN approach for enhancing water quality prediction under extreme class imbalance. Sci. Rep. 15, 13059 (2025).

Hand, D. J. & Till, R. J. A simple generalisation of the area under the roc curve for multiple class classification problems. Mach. Learn. 45, 171–186 (2001).

He, H., Bai, Y., Garcia, E. A. & Li, S. Adasyn: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. IEEE IJCNN, 1322–1328 (2008).

Arafa, A., El-Fishawy, N., Badawy, M. & Radad, M. RN-SMOTE: Reduced noise SMOTE based on DBSCAN for enhancing imbalanced data classification. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 34, 5059–5074 (2022).

Holzinger, A., Langs, G., Denk, H., Zatloukal, K. & Müller, H. Explainable ai and machine learning: A reality check. ERCIM News 2019, 14–15 (2019).

Nguyen, P., Tran, T., Wickramasinghe, N. & Venkatesh, S. Deep learning for deep problems: A novel approach to autoencoder-based dimensionality reduction for clinical text classification. J. Biomed. Inf. 86, 1–12 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J. and M.K.H. conceived the study and were responsible for methodology. A.J., M.K.H., and M.I.K. developed the methodology. M.U.S. and A.J. performed validation. A.J. and M.K.H. conducted the formal analysis. The investigation was carried out by A.J. and M.I.K. A.J. and M.U.S. curated the data. The original draft was written by A.J. and M.K.H. All authors (M.I.K., M.K.H., and M.U.S.) contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. A.J. prepared the visualizations. M.K.H. supervised the research study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jamil, A., Hanif, M.K., Sarwar, M.U. et al. An empirical evaluation of dimensionality reduction and class balancing for medical text classification. Sci Rep 16, 815 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30537-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30537-w