Abstract

To implement China’s strategic goal of “tailored and categorized approaches” for carbon reduction and enhance urban resilience under climate change pressures, systematic analysis is urgently needed to develop targeted urban emission reduction pathways. Utilizing panel data from 19 Chinese first-tier cities from 2002 to 2023, this study employs the XGBoost-SHAP interpretable machine learning model to investigate the driving effects of eight factors on carbon emissions:economic development level (PGDP), population size (POP), industrial structure (IS), technological innovation (TI), energy intensity (EI), urban form (D), public transportation (PT), and new digital infrastructure (DI). The K-means clustering algorithm is used to categorize the 19 cities into five types, enabling an in-depth analysis of the heterogeneous characteristics of carbon emission drivers across different city types. The main findings are as follows: (1) Population size (POP), energy intensity (EI), technological innovation (TI), public transportation (PT), and economic development level (PGDP) are significant factors influencing carbon emissions in first-tier cities, while the overall impact of new digital infrastructure (DI) remains ambiguous due to its dual role in increasing energy consumption and enabling energy-saving reforms. (2) The influence of individual drivers on carbon emissions exhibits significant heterogeneity across city types. Energy intensity (EI) has a substantial impact on carbon emissions in all five city types, whereas the effects of population size (POP), technological innovation (TI), and public transportation (PT) vary considerably depending on the city type. Based on the findings, this study proposes policy recommendations focusing on systematic governance of key elements, differentiated emission reduction strategies integrating resilience-building, and the establishment of a collaborative governance system to facilitate urban green transformation and enhance comprehensive resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Chinese government work report in 2025 emphasizes the necessity to synergistically promote carbon and pollution reduction alongside green growth expansion, accelerating the overall green transformation of economic and social development. By 2024, China’s GDP reached 134.91 trillion yuan, marking a 5.0% increase from the previous year and solidifying its position as the world’s second-largest economy. Despite long-standing prioritization of energy conservation and carbon reduction through initiatives like “carbon peaking and carbon neutrality”, “beautiful China construction”, and “comprehensive green transformation”, emission reduction challenges persist. According to International Energy Agency (IEA) statistics, China’s total carbon emissions amounted to 12.6 billion metric tons in 2024, approximately one-third of the global total. This underscores the substantial effort still required to achieve China’s “carbon peak and carbon neutrality” goals.

Cities, as centres of human socio-economic activity, account for approximately 75% of the nation’s total carbon emissions, making them the primary arena for energy conservation, emission reduction, and low-carbon development1. Notably, major Chinese cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, despite occupying only 2.6% of the national land area, generate approximately 33% of China’s GDP. Consequently, these cities play a pivotal role within the national economic development framework. However, the high concentration of economic activities, high-density population distribution, and high-intensity energy consumption in these major Chinese cities results in them contributing approximately 35% of the nation’s total CO2 emissions. Consequently, their carbon emission intensity per unit spatial area is significantly higher than that of medium-sized and small cities2. Precise identification of carbon emission driving factors in these major cities is therefore vital for achieving substantive national carbon mitigation breakthroughs. Significant disparities in developmental stages, economic levels, and spatial morphology among cities result in pronounced heterogeneity in urban carbon emission drivers3. Against this backdrop, precisely identifying driving factors in China’s first-tier cities and analyzing their heterogeneity across city types has become a critical research imperative, holding significant importance for facilitating China’s parallel advancement of high-quality economic development and high-standard environmental protection.

Current academic research on carbon emissions focuses on three primary aspects: first, the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics, explored across national4, provincial5 and regional6 scale using methods like Dagum Gini coefficient7, spatial autocorrelation indices8 and the natural breakpoint method9. Some scholars found that Chinese cities showed significant spatial aggregation characteristics through Gini coefficient10 and spatial autocorrelation analysis11,12. Second, identifying driving factors. A plethora of earlier studies have confirmed that conventional socio-economic factors, including population size13, economic growth14, industrial structure15, scientific and technological innovation16, energy consumption17, urban form18 and public transport19, are the pivotal factors affecting carbon emissions among Chinese provinces, cities and regions. In recent years, with the deep integration and synergistic application of new digital infrastructure alongside technologies such as big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence, this emerging digital infrastructure is progressively enabling resource sharing among cities through optimized factor allocation and the restructuring of economic geography. The transformations driven by digitalization are emerging as a new engine accelerating economic recovery and low-carbon transition20. For instance, Du et al.21 confirmed that digital infrastructure primarily reduces corporate carbon emissions by enhancing energy efficiency and boosting green technological innovation within enterprises. Chen et al.22 utilized panel data from 275 Chinese cities spanning 2010–2020 to discover that digital infrastructure significantly improves carbon emission efficiency, with this effect being more pronounced in central and resource-based cities. Third, the identification method of carbon emission drivers. Scholars usually adopt factor decomposition methods such as Kaya constant equation23, exponential decomposition method24 and general equilibrium method25 to group the drivers of carbon emissions into five categories: structural, economic, technological, social and demographic, and explore the effect of each factor on carbon emissions with the help of econometric models such as the STIRPAT model26 and panel quantile regression27. However, when dealing with numerous driving factors and complex variable relationships with substantial interaction effects, such methods tend to overlook the influence of underlying factors on carbon emissions, consequently leading to incomplete identification of driving factors28. In contrast, the XGBoost algorithm can directly learn and capture complex nonlinear relationships and interaction effects between various drivers and carbon emissions from the data, without requiring predefined functional forms. Furthermore, the SHAP framework deconstructs this “black-box” model to not only quantify the overall impact intensity of each factor on carbon emissions but also provide local explanations for individual samples. This precisely reveals the synergistic or antagonistic interactions among different factors within the context of specific cities29,30. This approach, which combines predictive accuracy with model interpretability, offers a more powerful analytical tool for precisely identifying the multidimensional drivers of carbon emissions. It effectively addresses the limitations of econometric models and factor decomposition methods, providing a new technical pathway for precisely identifying the drivers of carbon emissions in this study.

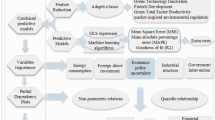

In summary, this study focuses on China’s first-tier cities and employs the XGBoost-SHAP interpretable machine learning model to investigate the impact of eight factors on urban carbon emissions: population size, economic development level, industrial structure, technological innovation, energy intensity, urban form, public transportation, and new digital infrastructure. Using the K-Means clustering algorithm, the 19 first-tier cities are categorized into five types, enabling an in-depth analysis of the heterogeneous characteristics of carbon emission drivers across different city categories. This aims to provide a scientific basis for formulating targeted emission reduction strategies and supporting urban green transformation. The marginal contributions of this study are primarily threefold: (1) In terms of variable selection, while existing research typically incorporates traditional socioeconomic factors such as economic development level, population size, industrial structure, technological innovation, energy intensity, urban form, and public transportation into the carbon emission driver analysis framework, this study innovatively introduces the emerging variable of new digital infrastructure. This inclusion recognizes that with the deep integration of new digital infrastructures—such as artificial intelligence and computing centers—into urban development, they have become crucial forces shaping new urban forms and increasingly exert significant influence on urban carbon emissions. (2) Regarding research methodology, the XGBoost-SHAP interpretable machine learning model adopted in this study has become a mainstream approach for evaluating driving factors due to its high accuracy and strong adaptability. Compared to commonly used factor decomposition methods and econometric models in academia, this model effectively overcomes overfitting issues in high-dimensional data scenarios, thereby providing more reliable technical support for analyzing carbon emission drivers. (3) In exploring the heterogeneity of urban carbon emission drivers, traditional studies often classify city types based on geographical location or economic strength, which can overlook intrinsic characteristics of the samples. This study applies the K-Means clustering algorithm to categorize cities according to their internal correlations and feature similarities, resulting in a city typology that better reflects real-world conditions. This approach more accurately reveals the heterogeneous characteristics of carbon emission drivers across different city types and offers theoretical support for developing differentiated emission reduction strategies. The framework diagram for this paper is shown in Fig. 1.

Methodology and data sources

Study area

This study is based on the “2024 New First-Tier Cities Attractiveness Ranking” released by the New First-Tier Cities Research Institute of Yicai. It selects four first-tier cities and 15 new first-tier cities from the published list as research subjects, specifically including 19 cities: Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuxi, Suzhou, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Qingdao, Zhengzhou, Wuhan, Changsha, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Chongqing, Chengdu, Xi’an, Dongguan, and Hefei. The ranking’s evaluation system comprises five key dimensions: concentration of commercial resources, city centrality, resident activity, new economic competitiveness, and future potential, which collectively reflect the comprehensive development level of the sampled cities in an objective manner. Furthermore, the sample cities demonstrate significant representativeness in terms of economic development and population size (as shown in Table 1). The per capita GDP of all selected cities exceeds the national average (91,814 yuan), underscoring their role as “leading geese” in China’s economic development. Concurrently, most of these cities are characterized by high population density, such as Chongqing (31.91 million) and Shanghai (24.87 million), making them primary contributors to energy consumption and carbon emissions. Against this backdrop, systematically analyzing the driving factors of their carbon emissions holds substantial theoretical and practical significance for advancing the national “Dual Carbon” goals.

XGBoost-SHAP model

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) is an enhanced gradient boosting decision tree algorithm proposed by chen et al.31. Compared to traditional gradient boosting, XGBoost improves computational efficiency and performance through several optimizations32. The objective function of XGBoost consists of a loss function and a regularisation term. Among them, the loss function is used to evaluate the error between the predicted value and the true value of the model, and optimize the model by minimizing the loss; the regularization term effectively controls the complexity of the model by constraining the total number of leaf nodes and the sum of squares of leaf node weights of the decision tree, so as to avoid overfitting the model. The optimal function of XGBoost is shown in Eq. (1).

Despite efficiently processing high-dimensional data and automatically filtering features, XGBoost’s complexity often renders it a “black-box model”, obscuring individual feature contributions33. The introduction of the SHAP value can effectively solve the interpretability limitation of the XGBoost algorithm, which was first proposed by Lloyd Shapley as a mathematical method to equitably distribute spending among players34. Based on this, Lundberg and Lee constructed the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework for interpreting the output of any machine learning model35, which, by fairly quantifying the contribution of each feature to the prediction result, not only clearly identifies the effect of individual features on the target variable, but also reveals the potential inter-feature interaction effects, with both local and global interpretability.The higher the SHAP value, the greater the contribution of the feature to the model prediction results.The formula for calculating the SHAP value is shown in Eq. (2)36.

Integrating XGBoost with SHAP not only serves to reduce model complexity, but also enables in-depth analysis of the impact effects of different factors on the target variable across a range of scenarios. This model has been extensively applied in diverse research fields, including bioinformatics and agriculture, and its reliability and credibility have been extensively validated. Consequently, this study employs the XGBoost-SHAP model to investigate the impact effects of these factors on carbon emissions in Chinese megacities and to examine the heterogeneity in their effects across different city types.

where T denotes the number of leaf nodes in the tree; Gj denotes the sum of first-order partial derivatives of the samples contained in leaf node j; and Hj denotes the sum of second-order partial derivatives of the samples contained in leaf node j.

where φi denotes the contribution of the i-th feature; N denotes the set of all features; S represents the subset of the given predicted features; f(S ∪ {i}) and f(S) represent the model prediction results with or without the i-th feature, respectively.

K-means clustering algorithm

To explore the drivers of carbon emissions in 19 first-tier cities, this paper uses the K-means clustering algorithm (a data clustering method) to scientifically classify the cities. Unlike traditional classification based on geographic location or economic strength, the K-means clustering algorithm can explore potential correlations and differences between cities based on their intrinsic characteristics. It can also separate similar cities as a class and separate those with low similarity, ensuring accurate results37. The K-means clustering algorithm was proposed by MacQueen in 1967 and is used by academics due to its simplicity and efficiency38. The elbow method is used to determine the number of clusters (K). As K increases, the sample division becomes more refined, the aggregation of each cluster improves, and the sum of squares of errors (SSE) decreases. When K is smaller than the number of clusters, the SSE decreases significantly. When K equals the true number of clusters, the SSE drops abruptly, then stabilises as K increases. The formula for calculating the SSE is shown in Eq. (3)38. This paper uses sample clustering to classify 19 first-tier cities in China. High-similarity cities are grouped into one category, then combined with the SHAP algorithm to interpret the XGBoost model. This is used to explore the heterogeneity characteristics of drivers of carbon emissions in different types of cities and provide a basis for developing accurate emission reduction strategies.

where P denotes the position of the point. mi is the position of the centre point.

Factor selection

Based on related studies22,40,41, eight indicators were selected as carbon emission drivers:

-

(1)

Economic development level (PGDP). Research shows a non-linear relationship between economic development and carbon emissions, showing an “U” shape42. Carbon emissions increase with economic growth until a certain level is reached, after which they decrease. This study uses urban per capita GDP as a measure of urban economic development.

-

(2)

Population size (POP).The population is a key variable in urban carbon emissions. Changes in population size directly impact residents’ consumption, and therefore urban carbon emissions. An increase in population size typically leads to higher demand, and greater carbon emissions43. This study uses the annual population count as a proxy for urban population size.

-

(3)

Industrial structure (IS).Urban industrial structure significantly impacts carbon emissions. Transitioning from primary to secondary industry increases emissions due to high energy consumption. Conversely, moving from secondary to tertiary industry reduces emissions as the secondary industry’s share declines. This paper uses the secondary industry’s output value as a percentage of regional GDP (IS) to measure city industrial structure.

-

(4)

Energy intensity (EI).Energy efficiency and consumption structures are a hot research topic in low-carbon and green economy. Energy intensity is the ratio of energy consumption to economic output. Higher energy intensity means more energy consumed per unit of economic output. Burning large amounts of fossil fuels leads to higher carbon emissions. This study converts the total energy consumption of each city to the unit of standard coal using a discounted coal coefficient. This eliminates the measurement bias caused by the difference of energy types. The energy intensity of each city is calculated by dividing the converted total energy consumption by the city’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is then incorporated into the framework of analysing the drivers of carbon emissions.

-

(5)

Technological innovation (TI).Green technological innovation promotes the economical use of resources by improving products, services and production methods, reducing carbon emissions and improving environmental performance44. Patent-related indicators are used to measure green technological innovation, including the number of patent applications and the number of patents granted. The latter is a better measure of actual innovation capacity45. This paper uses the number of green patent grants as a measure of urban technological innovation.

-

(6)

Urban form (D).Urban form reflects the physical attributes of urban space over time. It can be portrayed as the geometric spatial characteristics of various material elements depending on the urban land layout and transport network46. The impact of compact urban form on urban carbon emissions is twofold. Some studies have empirically proved that compact and low-dispersed urban form helps to reduce urban carbon dioxide emissions47. However, some scholars argue that the more compact the urban spatial form, the greater the regional carbon dioxide emissions, thereby exacerbating the urban heat island effect48. Therefore, exploring the impact of urban form on urban carbon emissions is crucial for Chinese cities to achieve the goal of “double carbon”. This paper refers to the study of Fang et al.49 to calculate the degree of urban compactness (D) to measure urban form.

-

(7)

Public transportation (PT).Developing urban public transport is crucial for reducing urban carbon emissions. Building a low-carbon, environmentally friendly public transport system is a key part of the sustainable urban development strategy and the promotion of an ecological civilisation. Promoting green travel modes and reducing the use of private cars can effectively reduce carbon emissions in urban transport. With this in mind, this paper uses the number of buses per 10,000 people as an indicator of urban public transport.

-

(8)

New digital infrastructure (DI). The construction of new digital infrastructure can improve efficiency and reduce regulatory costs, optimising industrial structure and encouraging green technological innovation, and thus helping to reduce carbon emissions50,51. In this paper, we calculate the development level of new digital infrastructure in cities using Huang et al. as reference.

Data sources

Carbon emission (CE) data were sourced primarily from the EDGAR Global Atmospheric Research Emissions Database. Urban energy consumption data came from city statistical yearbooks. The discounted coal coefficient was sourced from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook. Data for other variables were primarily drawn from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook (2003–2024), provincial/municipal yearbooks, and statistical bulletins. For missing urban form and energy intensity data in certain cities for specific years (approximately 5% missing), this study employs multiple imputation using SPSS 27.0 software. This method effectively handles randomly missing data, avoiding sample size loss from direct deletion of missing cases. It helps maintain statistical power, ensuring stable and reliable parameter estimates, particularly suited for the limited sample size in this panel data analysis. Table 2 presents the definitions, units, and sources of each variable. To eliminate the impact of differing dimensions among variables and enhance result reliability, all variables underwent Z-score standardization prior to empirical analysis. This method transforms raw data into new sequences with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, effectively improving the convergence speed and performance stability of subsequent machine learning models. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 3.

Results and discussion

Analysis of carbon emission drivers in China’s first-tier cities

An XGBoost model for predicting urban carbon emissions was constructed using Python 3.9 (scikit-learn and xgboost libraries). Hyperparameters were optimized via Grid Search with fivefold cross-validation, yielding optimal settings: learning_rate = 0.05, max_depth = 4, n_estimators = 200, reg_alpha = 0.1, reg_lambda = 1. This model achieved a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.212, significantly lower than 0.500, demonstrating high predictive accuracy and robust explanatory capability. Subsequently, to investigate the extent to which each driving factor influences urban carbon emissions, this study further employs the SHAP algorithm to conduct an interpretability analysis on the optimal XGBoost model. This yields SHAP values for each driving factor (as shown in Fig. 2a), where the magnitude of the SHAP value intuitively reflects the impact of each factor on carbon emissions in first-tier cities. As shown in the driver importance ranking in Fig. 2a, among all factors, POP exerts the most significant influence on carbon emissions in China’s first-tier cities, with a SHAP value of 0.294. This indicates that among all factors considered by the model, population size causes the predicted carbon emissions to deviate from the baseline by 0.294 standard deviations. This result aligns closely with the reality that highly dense populations in first-tier cities drive surges in energy consumption for production and daily life, significantly boosting carbon emissions. Next in importance are EI, TI, PT, and PGDP, with corresponding SHAP values of 0.274, 0.260, 0.167, and 0.142. These figures indicate that these factors exert varying degrees of influence on urban carbon emissions. In contrast, IS, D, and DI exert relatively limited impacts on carbon emissions in first-tier cities.

Figure 2b illustrates the directional effect of each factor. Positive SHAP values indicate factors promoting emissions; negative values indicate inhibition. Red/blue points represent high/low feature values. Most sample points for POP, PGDP, EI, and IS are concentrated in the positive SHAP range and mostly in red, indicating that population growth, economic expansion, energy intensity, and the increase of the secondary industry proportion will exacerbate urban carbon emissions.The reason is that as the population of first-tier cities grows, so does demand for housing, transport and living consumption. This contributes to the rise in energy consumption and carbon emissions.At the same time, during the economic expansion phase, the proportion of secondary industry will increase significantly, prompting the expansion of high energy-consuming industries such as iron and steel, chemical industry, building materials, etc., thus consuming a large amount of energy during the production process, resulting in the overall carbon emissions of the city to climb. On the contrary, the sample points for TI, PT and D are mainly distributed in the blue zone of the negative SHAP value, which implies that improving technological innovation, public transport and decentralised urban form can effectively curb urban carbon emissions. However, for the digital infrastructure (DI), sample points are uniformly distributed in the positive and negative SHAP regions, and the overall impact is small, indicating no obvious directionality of the new digital infrastructure on urban carbon emissions. This is due to new digital infrastructures, e.g. 5G base stations and data centres, still being developed. Data centres and other facilities consume energy, potentially increasing emissions, but the DI can also empower traditional industries to make energy-saving reforms, reducing emissions. This interaction makes the comprehensive impact of DI on urban carbon emissions unclear at present.

Analysis of K-means clustering results

To scientifically determine the optimal number of clusters for 19 first-tier cities, this study employs the K-means clustering algorithm and evaluates the trend of the sum of squares within clusters (SSE) as the number of clusters K varies (Fig. 3). The fundamental principle of this method is that as K increases, samples are partitioned more finely, causing SSE to gradually decrease. However, when K exceeds the true number of clusters, the rate of SSE decline significantly slows, forming an “elbow” pattern that indicates the optimal number of clusters. Figure 3 shows that when K increases from 1 to 4, SSE ranges between 99 and 160, demonstrating a noticeable decrease. However, when K = 5, SSE drops to 77, and the subsequent decline becomes markedly flatter. This indicates that further increasing the number of clusters offers limited contribution to improving aggregation. Therefore, K = 5 is considered the optimal number of clusters, effectively distinguishing different types of urban characteristics while ensuring high aggregation of samples within clusters. Based on the above analysis, this study categorizes the 19 first-tier cities into five types, with the specific classification results presented in Table 4.

-

(1)

Category I(Ningbo): As the economic and chemical centre of the southern Yangtze Delta, Ningbo has long relied on petrochemicals and energy to drive its economic growth. In 2023, the value-added output of Ningbo’s secondary industry accounted for 45.8% of its total output, exceeding the average level of 35.8% across the first-tier cities by 10% points. This structure results in disproportionate industrial energy consumption and elevated carbon emissions. Ningbo’s pronounced divergence from the other 18 cities is the key reason for its distinct categorisation.

-

(2)

Category II(Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing, Suzhou, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Chongqing): Among these, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangzhou, and Chongqing are nationally designated central cities. These urban centers exhibit substantial economic scales and high population densities, with their economic output ranking among the highest within the cohort of first-tier cities nationally. For instance, 2023 data indicate that these seven cities collectively accounted for 44.5% of the aggregate GDP of all national first-tier cities, with a combined year-end population exceeding 120 million. The immense population size drives a substantial increase in daily residential energy consumption. Consequently, total urban carbon emissions persistently remain elevated, forming a characteristic “dual-high” profile: high economic output coupled with high carbon emissions. While generating substantial economic value, these cities simultaneously face significant emission reduction pressure.

-

(3)

Category Ⅲ (Wuxi, Hangzhou, Qingdao, Zhengzhou, Changsha, Chengdu, Xi’an, Hefei): Predominantly provincial capitals.Exhibits “steady progress and comprehensive coordination” in economy, population, and emissions. In economic terms, the combined total of the GDP of these cities is expected to account for approximately 30% of the total GDP of the first-tier cities in China in 2023. The economic strength of these cities is classified as mid-level, and their industrial structure is characterised by diversification, with the synergistic development of emerging and traditional industries. With regard to carbon emissions, it is estimated that the total carbon emissions of these cities in 2023 will account for approximately 26.7% of the first-tier cities in China. This is considered to be at an intermediate level among the five types of cities. Furthermore, the carrying capacity of resources and the environment is relatively stable, achieving a satisfactory balance between economic growth and ecological protection.

-

(4)

Category IV (Beijing): As a national political, cultural, international communication, and sci-tech innovation center, Beijing has amassed the country’s preeminent scientific and educational resources, and its innovation capacity is among the highest in the country. The industrial structure is characterised by a predominance of knowledge-intensive and high value-added services, with the tertiary industry contributing 84.8 per cent of GDP in 2023. Moreover, the city of Beijing has persisted in its endeavours to establish novel digital infrastructure. It has accomplished the establishment of 5G network coverage throughout the entire region and has erected substantial arithmetic facilities, including the Beijing Digital Economy Arithmetic Centre, which boasts arithmetic capabilities that are at the forefront of the nation. Consequently, Beijing’s technological innovation capacity and level of new digital infrastructure both exhibit clear advantages across the five categories of cities, providing substantial support for low-carbon development.

-

(5)

Category V(Shenzhen, Dongguan): Leveraging high levels of technological innovation, these cities focus on developing low-carbon, high-value-added industries such as electronic information and new energy, establishing distinct advantages in low-carbon industrial clusters. Concurrently, both cities actively advance the construction of new digital infrastructure, including data centers and artificial intelligence. For instance, Shenzhen has deployed over 65,000 5G base stations, achieving comprehensive 5G network coverage. Dongguan, utilizing the Huawei Songshan Lake Base, drives the intelligent transformation of its power grid. This enables intelligent dispatching, transmission, transformation, and distribution across the entire power network, thereby realizing intelligent urban operational management. These measures effectively reduce energy consumption intensity, resulting in significantly lower carbon emissions compared to cities in the other four categories.

Analysis of carbon emission drivers in different types of cities

The present study is an extension of the preceding research, which involved the classification of 19 first-tier cities into five distinct categories. Utilizing the XGBoost-SHAP model, the current study undertakes a more profound examination of the carbon emission drivers that are characteristic of each city category. The model quantitatively analyses the importance of each factor and reveals the direction of its role on urban carbon emissions, as demonstrated in Figs. 4 and 5.

-

(1)

For category I city (Figs. 4a, 5a), EI is the most significant driver of urban carbon emissions, with a SHAP value of 0.264.This indicates that an increase of one standard deviation in EI leads to an average increase of 0.264 standard deviations in predicted carbon emissions. Most of its sample points appear red and are concentrated in the positive SHAP value range. This indicates that energy consumption per unit of economic output significantly drives up urban carbon emissions. This primarily stems from Ningbo’s industrial structure, which is dominated by heavy industry and manufacturing. These sectors generally rely on high-energy-consumption production models. This results in low energy utilization efficiency and consequently keeps carbon emissions per unit of GDP persistently high. TI follows with a SHAP value of 0.200. Its sample points are predominantly blue and reside in the negative SHAP value range. This indicates a negative correlation between technological innovation and urban carbon emissions. In other words, higher levels of technological innovation exert stronger suppression on carbon emissions. However, Ningbo’s current level of technological innovation remains medium to low, preventing technological emission reductions from achieving sufficient economies of scale to offset the positive driving effect of energy intensity. PT ranked third with a SHAP value of 0.147. Most of its sample points were red and fell within the negative SHAP value range. This signifies that improving public transportation infrastructure reduces urban carbon emissions.

-

(2)

For category Ⅱ cities (Figs. 4b, 5b), POP, TI, and EI exert dominant influences on urban carbon emissions, with SHAP values of 0.340, 0.267, and 0.252 respectively. Notably, most data points for POP and EI appear in red and cluster within the positive SHAP value range, indicating these factors significantly promote urban carbon emissions. The massive population base drives continuous growth in residential energy consumption for household electricity and transportation. Meanwhile, cities like Tianjin, Nanjing, Chongqing, and Wuhan are dominated by heavy chemical industries, with high-energy-consuming sectors such as steel and chemicals accounting for a significantly higher proportion than in the other four city categories. These industries not only feature complex production processes and high energy intensity but also lag in technological innovation and energy efficiency improvements, resulting in persistently high energy consumption per unit of GDP. In contrast, the sample points for TI are primarily concentrated in the negative range of SHAP values, indicating its inhibitory effect on urban carbon emissions. This is because technological innovation drives green industrial upgrading and optimizes production processes, effectively enhancing energy utilization efficiency and helping cities reduce carbon emissions at the source of production.

-

(3)

For category III cities (Figs. 4c, 5c), EI, TI, and POP are significant drivers of urban carbon emissions, with SHAP values of 0.285, 0.228, and 0.197, respectively. The sample points for all three factors are predominantly concentrated within the positive SHAP value range, indicating their overall promotional effect on carbon emissions at the current developmental stage. Specifically, these cities have generated substantial population agglomeration effects by functioning as regional development hubs and providing high-quality public resources. Population growth directly increases energy consumption in residential, transportation, and daily living sectors, thereby driving carbon emission growth. Additionally, their continued reliance on energy-intensive sectors within the industrial structure has prevented fundamental improvements in energy efficiency, making EI a significant contributor to carbon emissions. Notably, TI also exhibits a positive correlation with emissions, possibly due to the absence of systematic emission reduction capabilities of green technologies at this stage. Alternatively, the processes of manufacturing equipment and upgrading infrastructure that accompany technological investments may generate additional emissions. This phenomenon reflects incomplete decoupling between innovation and emission reduction.

-

(4)

For category IV cities (Figs. 4d, 5d), PT, POP, and EI significantly influence urban carbon emissions, with SHAP values of 0.327, 0.236, and 0.231 respectively. Data distribution shows that most PT sample points fall within the negative SHAP value range, indicating its significant suppression effect on urban carbon emissions. Such cities effectively guide residents toward green travel by establishing high-density, low-energy public transit networks, thereby substantially reducing carbon emissions in the transportation sector. Additionally, POP and EI promote urban carbon emissions. Continuous population growth drives simultaneous surges in electricity demand for urban operations and daily residential energy consumption (e.g., electricity and gas), directly leading to significant increases in carbon emissions. Moreover, Beijing’s technology-service-dominated industrial structure, while rapidly developing, often involves large-scale construction of energy-intensive infrastructure like data centers and supercomputing facilities. This may trigger phased increases in energy consumption, objectively promoting carbon emissions. However, as new digital infrastructure matures, the technology-service sector’s dependence on energy will gradually decrease. The low-carbon effects of technological innovation will also progressively emerge, ultimately driving carbon emissions downward.

-

(5)

For category V cities (Figs. 4e, 5e), POP, EI, and PT are key factors influencing urban carbon emissions, with SHAP values of 0.539, 0.333, and 0.244 respectively. Data distribution shows that most sample points for POP, EI, and PT fall within the negative SHAP value range, indicating these factors exert a significant suppressing effect on urban carbon emissions. Specifically, these cities have effectively guided residents toward green commuting by establishing high-density, low-energy public transit networks, thereby substantially reducing carbon emissions in the transportation sector. While population concentration typically increases energy demand, these cities have achieved a “decoupling” between population growth and carbon emissions through compact spatial layouts and efficient infrastructure sharing. Furthermore, cities like Shenzhen and Dongguan have actively phased out energy-intensive industries while vigorously promoting energy-saving technologies and clean energy applications. This has driven a sustained decline in energy consumption per unit of GDP, enabling economic growth with lower energy inputs and effectively curbing urban carbon emissions. Consequently, due to the synergistic effects of factors such as POP, EI, and PT, Category V cities exhibit significantly lower carbon emission levels than the other four categories.

Robustness test

To eliminate potential interference from the pandemic period on empirical results, this study excluded data from 2020 to 2022 and conducted robustness tests, with results presented in Figs. 6, 7 and 8. The tests indicate that after removing outliers during the pandemic period, the direction and relative importance of each driving factor on carbon emissions in first-tier cities remained largely unchanged. These findings are highly consistent with the benchmark model conclusions, further validating the robustness and reliability of this study’s findings.

Conclusions

This study utilises the XGBoost-SHAP model to analyse the impact of eight key driving factors on carbon emissions in 19 Chinese first-tier cities from 2002 to 2023. The driving factors encompass the following: economic development level (PGDP), population size (POP), industrial structure (IS), technological innovation (TI), energy intensity (EI), urban form (D), public transportation (PT) and new digital infrastructure (DI). Furthermore, moving beyond traditional classification methods based on geographical location or economic strength, this paper utilizes the K-means clustering algorithm to categorize the 19 first-tier cities into five distinct types, facilitating an in-depth analysis of the heterogeneous characteristics of carbon emission drivers across different city categories.

-

(1)

Analysis of the driving factors for carbon emissions across the national first-tier cities reveals that POP, EI, TI, PT, and PGDP are key determinants influencing urban carbon emissions. Among these, POP, PGDP, and EI exert positive effects, exacerbating urban carbon emissions. Conversely, TI and PT significantly mitigate urban carbon emissions.

-

(2)

With regard to the factors that influence carbon emissions in different types of cities, the effect of each factor on the carbon emissions of each city exhibits significant heterogeneity characteristics. Of these, EI has a significant impact on carbon emissions in all five types of city, but the driving direction of carbon emissions in different types of city is clearly differentiated. In category I, II and III cities, an increase in energy intensity has been shown to exacerbate urban carbon emissions. Conversely, in category IV and V cities, a negative correlation has been demonstrated between energy intensity and urban carbon emissions. Furthermore, POP exerts a more substantial influence on carbon emissions in category II, III, IV and V cities; PT can have a considerable impact on carbon emissions in category I, II and V cities; and TI plays a pivotal role in the process of carbon emission changes in category I, Ⅱ and III cities.

Recommendations

-

(1)

Implement systematic emissions reduction by targeting five core drivers.

Carbon emissions in first-tier cities are primarily influenced by population size, energy intensity, technological innovation, public transportation, and economic development levels. Therefore, a systematic emissions reduction strategy must focus on these five drivers. First, establish a dedicated carbon reduction fund. Following the approach of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which raised over $2.7 billion in nature-based finance through the Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN), diversify funding sources, attract social capital, and prioritize investments in clean energy R&D and energy-saving technological innovation. Second, optimize the layout of public service facilities to create convenient, low-carbon living zones. For densely populated first-tier cities with high daily mobility demands, reference can be made to Jiulongpo District, Chongqing’s plan to “weave a dense network of new energy supercharging facilities.” This involves increasing bus stop density, optimizing routes, and ensuring seamless integration between rail transit and public buses. For living amenities, rationally allocate public service facilities such as shopping malls, medical centers, and educational institutions to shorten residents’ travel distances and reduce carbon emissions from daily life. Third, guide industrial structure transformation toward low-carbon development based on urban economic levels, prioritizing support for green industries while reducing the share of high-energy-consuming sectors.

-

(2)

Promote targeted emission reductions and implement differentiated pathways for cities.

Given the significant differences in carbon emission drivers across various city types, tailored measures should be adopted based on local conditions. For instance, Ningbo should establish a dynamic energy consumption early-warning mechanism for key industries, strictly control the energy intensity of high-energy-consuming sectors such as steel and chemicals, and subject enterprises exceeding limits to focused oversight and rectification. Cities like Tianjin and Shanghai should strengthen green technology innovation, increase policy support and funding for emerging industries such as energy conservation, environmental protection, and new energy, and promote industrial structure upgrades toward low-carbon and high-end sectors. Cities like Wuxi and Hangzhou should fully leverage the emission reduction potential of public transportation, accelerate the development of a green transportation system anchored by rail transit and supplemented by surface buses, guide citizens toward eco-friendly commuting, and alleviate carbon pressure from population concentration. Beijing should leverage cutting-edge technologies like cloud computing and artificial intelligence to cultivate knowledge-intensive service industries such as industrial IoT and next-generation information technology, building low-energy, high-value-added low-carbon service clusters. Shenzhen and Dongguan need to consolidate their technological innovation advantages, accelerate the commercialization of low-carbon technologies, and strengthen industry-academia-research integration.

-

(3)

Build a collaborative emission reduction system to promote regional joint governance.

First-tier cities must break down administrative barriers by building a multidimensional collaborative governance system centered on institutional innovation, data interoperability, and industrial synergy to achieve comprehensive carbon emissions control across the entire chain52. On one hand, establish a cross-regional carbon emissions collaborative governance network by creating a unified regional carbon emissions data-sharing platform to monitor city emissions data in real time and establish a joint prevention and control mechanism for risks. Upon detecting abnormal emissions in any city, immediately activate joint response protocols. Concurrently, regularly organize inter-city exchanges on emission reduction technologies and best practices to enhance data interoperability and governance efficiency. Simultaneously, promote low-carbon industrial upgrades through inter-city collaboration, guiding cities to establish industrial cooperation mechanisms. Optimize industrial chain layouts based on each city’s strengths to achieve efficient resource utilization and coordinated emission controls, ultimately forming a new regional emission reduction paradigm characterized by “technological complementarity, resource sharing, and shared responsibility.”

Research outlook

The XGBoost-SHAP framework developed in this study provides an effective tool for analyzing the driving mechanisms of urban carbon emissions. Future research could be deepened in the following aspects: First, the methodology could be extended to key urban agglomerations such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area to investigate the similarities and differences in their carbon emission driving factors and explore coordinated emission reduction pathways. Second, other advanced machine learning models such as Random Forest and LightGBM could be compared to obtain more robust findings or new insights. Third, promoting the application of this approach across multiple scales (e.g., provincial and county levels) and dimensions (e.g., incorporating consumption-based carbon emissions) would help establish a more systematic research framework for understanding the driving factors of carbon emissions.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

Peixue, X. et al. Carbon emission efficiency of 284 cities in China based on machine learning approach: Driving factors and regional heterogeneity. Energy Econ. 129, 107222 (2024).

Wu, R., Xie, Z., Wang, J. & Wang, S. Estimating the environmental Kuznets curve and its influencing factors of CO2 emissions: Insights from development stages and rebound effects. Appl. Geogr. 174, 103475–103475 (2025).

Wang, Z. & Shao, H. Spatiotemporal interactions and influencing factors for carbon emission efficiency of cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 103, 105248 (2024).

Wu, C., Deng, H., Zhao, H. & Xia, Q. Spatiotemporal evolution and convergence patterns of urban carbon emission efficiency in China. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 675–675 (2025).

Wu, J. & Li, K. Analysis of spatial and temporal evolution and driving factors of carbon emission in Shandong Province: Based on the perspective of land use. Environ. Sci. Eur. 36, 171–171 (2024).

Jia, B., Xie, M., Wu, J. & Zhao, J. Towards low carbon urban agglomerations: Spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emission intensity and network linkages in China’s urban agglomerations. Ecol. Ind. 177, 113728–113728 (2025).

Zhu, X. & Shao, X. Spatiotemporal evolution of agricultural carbon emissions intensity in China and analysis of influencing factors. Sci. Rep. 15, 19202–19202 (2025).

Zhao, S., Yu, Z. & Liu, W. Revealing the spatio-temporal coupling coordination characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emissions from urban use and ecosystem service values in China at the municipal scale. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13, 1539909–1539909 (2025).

Xie, P., Wang, S., Liao, J. & Sun, F. Study on spatial–temporal disparities and factors influencing electricity consumption carbon emissions in China. Sustainability 16, 4128 (2024).

Wang, N. et al. Spatial–temporal patterns and influencing factors of carbon emissions in different regions of China. Environ. Res. 276, 121447 (2025).

Liu, C., Hu, S., Wu, S., Song, J. & Li, H. County-level land use carbon emissions in China: Spatiotemporal patterns and impact factors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 105, 105304 (2024).

Yang, X. & Zhu, L. Spatial correlation network of China’s carbon emissions and its influencing factors: Perspective from social network analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 516, 145671–145671 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Examination of spatial and temporal evolution characteristics of carbon emission and influencing factors in territorial spatial functional areas: A case study of the mountainous city Chongqing. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 21, 360–373 (2025).

Yanfang, C., Li, L., Yalin, L. & Sanmang, W. The performance and influencing factors of high-quality development of resource-based cities in the Yellow River basin under reducing pollution and carbon emissions constraints. Resour. Policy 88, 104488 (2024).

Yuan, R. et al. Study on the spatial and temporal evolution of building carbon emissions and influencing factors in the urban agglomeration of the Yangtze river economic belt. Energies 17, 5752–5752 (2024).

Park, G. & Kim, D. Regional carbon emission efficiency analysis and factor decomposition: Cases from South Korea. Energy Rep. 13, 903–913 (2025).

Zhu, Y., Liu, X., Feng, C., Zhang, T. & Wang, X. An empirical study on the evolution and driving factors of energy-related carbon emissions in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Front. Environ. Sci. 13, 1596713–1596713 (2025).

Qin, Y. et al. Assessment of the impact of urban block morphological factors on carbon emissions introducing the different context of local climate zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 119, 106073–106073 (2025).

Li, Z. & Wu, J. Spatial–temporal characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emission in Chengdu–Chongqing area: An urban transportation perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 31, 24425–24445 (2024).

Ma, D., Sun, H., Xia, X., Zhao, Y. & Yang, Z. Digital infrastructure construction, diversified environmental regulation, and dual control of urban carbon emissions—quasi-natural experiment from “broadband China” strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 101280–101295 (2023).

Du, Y. & Li, M. Research on the impact of digital infrastructure construction on enterprise carbon emissions. Sci. Rep. 15, 29989–29989 (2025).

Chen, J., Lv, Y. & Gao, F. Exploring the relationship between digital infrastructure and carbon emission efficiency: New insights from the resource curse and green technology innovation in China. Resour. Policy 98, 105354–105354 (2024).

Junhong, H. et al. Multi-factor decomposition and multi-scenario prediction decoupling analysis of China’s carbon emission under dual carbon goal. Sci. Total Environ. 841, 156788–156788 (2022).

Kim, H., Lee, Y., Koo, J. H. & Yeo, M. J. Changes in future carbon dioxide emissions and contributing factors in Southeast Asia under the shared socioeconomic pathways. Energy Sustain. Dev. 86, 101721–101721 (2025).

Xiao, B., Niu, D. & Wu, H. Exploring the impact of determining factors behind CO2 emissions in China: A CGE appraisal. Sci. Total Environ. 581–582, 559–572 (2016).

Zhou, X., Wang, J., He, W., Wei, Q. & Yang, Y. Spatial–temporal distribution and influencing factors of urban carbon emissions under the background of carbon emission reduction: A case study of Guangxi autonomous region. J. Resour. Ecol. 15, 870–879 (2024).

Altaf, A., Anwar, M. A., Shahzad, U. & Bilan, Y. Exploring the nexus among green finance, renewable energy and environmental sustainability: Evidence from OECD economies. Renew. Energy 244, 122589–122589 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Study on carbon emission influencing factors and carbon emission reduction potential in China’s food production industry. Environ. Res. 261, 119702 (2024).

Hang, H. T., Mallick, J., Alqadhi, S., Bindajam, A. A. & Abdo, H. G. Exploring forest fire susceptibility and management strategies in Western Himalaya: Integrating ensemble machine learning and explainable AI for accurate prediction and comprehensive analysis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 35, 103655 (2024).

Song, Z., Cao, S. & Yang, H. An interpretable framework for modeling global solar radiation using tree-based ensemble machine learning and Shapley additive explanations methods. Appl. Energy 364, 123238 (2024).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. CoRR abs/1603.02754 (2016).

Ravid, S.-Z. & Amitai, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Inf. Fus. 81, 84–90 (2022).

Zhao, X., Shao, B., Su, J. & Tian, N. Exploring synergistic evolution of carbon emissions and air pollutants and spatiotemporal heterogeneity of influencing factors in Chinese cities. Sci. Rep. 15, 2657–2657 (2025).

Shapley, L. S., A Value for N-Person Games. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation(1952).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S. I. A Unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Nips (2017)

Xinzhi, Z., Haijia, W., Ziwei, L., Hui, Z. & Wengang, Z. An interpretable model for the susceptibility of rainfall-induced shallow landslides based on SHAP and XGBoost. Geocarto Int. 37, 13419–13450 (2022).

Rui, J. & Cai, C. Plausible or misleading? Evaluating the adaption of the place pulse 2.0 dataset for predicting subjective perception in Chinese urban landscapes. Habitat Int. 157, 103333–103333 (2025).

MacQueen, J. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 1: Statistics.

Sulin, W., Yifan, W. & Shenggang, Y. Study of factors affecting deposit insurance premium rate based on cluster analysis. Theory Pract. Finance Econ. 42, 35–41 (2021).

Xing, M. et al. Toward integrated governance of urban CO2 emissions in China: Connecting the “codes” of global drivers, local causes, and indirect influences from a multi-perspective analysis. Cities 134, 104181 (2023).

Hui, H., Zhaoxi, W., Qingru, G. & Qingjie, G. Analysis of spatial–temporal evolution and influencing factors of carbon emission efficiency in Chinese cities. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1119914 (2023).

Yuanhao, L., Arshad, A., Yuanchun, C. & Xiao, S. The effect of transport infrastructure (road, rail, and air) investments on economic growth and environmental pollution and testing the validity of EKC in China, India, Japan, and Russia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30, 32585–32599 (2023).

Xiaoyan, L., Chunfeng, Z., Xin, L. & Bo, Z. Population change, consumption structure, and carbon emission reduction. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 42, 5–28 (2025).

Xicang, Z., Meng, J. & Dou, H. The impact of green technology innovation on the synergistic effect of pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction. Sci. Technol. Progress Policy 1–13 (2025).

Shaozhou, Q., Shen, L. & Jingbo, C. Do environmental rights trading schemes induce green innovation? Evidence from listed firms in China. Econ. Res. J. 53, 129–143 (2018).

Yan, Q. & Limin, J. Impacts of urban form on transportation carbon emissions from a global perspective. Geogr. Res. 42, 3202–3218 (2023).

Pu, J., Tao, X., Yan, J. & Xia, F. Urban compactness and carbon emissions: A novel insight based on urban scaling law. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 116, 108108–108108 (2026).

Xu, Z. & Rui, J. The mitigating effect of green Space’s spatial and temporal patterns on the urban heat island in the context of urban densification: A case study of Xi’an. Sustain. Cities Soc. 117, 105974–105974 (2024).

Chuanglin, F., Jitao, S., Qiang, Z. & Ming, L. The formation, development and spatial heterogeneity patterns for the structures system of urban agglomerations in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 60, 827–840 (2005).

Nie, J., Shen, J. & Ren, X. Digital infrastructure, new digital infrastructure, and urban carbon emissions: Evidence from China. Atmosphere 16, 199–199 (2025).

Xiao, X., Chang, L. & Shixiang, L. How the digital infrastructure construction affects urban carbon emissions—a quasi-natural experiment from the “Broadband China” policy. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169284 (2024).

Liu, Y., Ouyang, Q. & Lu, C. Exploring the effect of urban position of the inter-urban pollution transfer network on carbon emissions: Evidence from 276 cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 516, 145789–145789 (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province,China(No. 2021JJ30368).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.designed the framework and revised the manuscript.Y.H.completed the first draft.F.Y, H.A and J.L:collected data.Y.X.perfected the manuscript.All authors contributed to this article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., He, Y., Yang, F. et al. An XGBoost-SHAP analysis of the driving factors of carbon emissions in China’s first-tier cities. Sci Rep 16, 1659 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31260-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31260-2