Abstract

Ketamine-induced cystitis (KC) manifests as lower urinary tract symptoms stemming from prolonged ketamine abuse, yet its precise pathogenesis remains unclear. It is widely recognized that gut microbiota dysregulation can trigger metabolic aberrations in many diseases. This study aimed to address the dearth of knowledge regarding the functional characteristics of gut microbiota and their metabolites in KC, and to explore the underlying mechanisms of KC from the perspective of the gut-bladder axis. Metagenomic and untargeted metabolomic analyses were employed to elucidate critical features of gut microbiota and metabolism in KC rats. Metagenomic sequencing revealed significant gut microbiota dysregulation, characterized by discrepancies in 46 bacterial taxa at the species level, including Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, Erysipelotrichaceae bacterium OPF54, Firmicutes bacterium CAG: 424, and Phocaeicola sartorii. Untargeted metabolomics identified 13 dysregulated metabolites, encompassing Stachydrine, Quinoline, Sedanolide, and others. Correlation analyses among differential gut microbiota, metabolites, and bladder inflammatory factors in KC rats suggested a potential interconnectivity between these factors. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory property of Stachydrine was experimentally validated using an in vitro model. These findings collectively indicate that KC rats exhibit alterations in gut microbiota composition and metabolites profiles, establishing a preliminary association among gut microbiota, metabolites, and KC pathogenesis. Finally, validation of the anti-inflammatory effects of Stachydrine provides insight into a potential pathogenic pathway involving gut–bladder axis crosstalk, in which dysregulation of gut microbiota and metabolites contributes to the development of KC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ketamine, a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex antagonist, is clinically valued for its analgesic and antidepressant effects at therapeutic doses, providing relief for surgical patients and treating psychiatric disorders1,2. However, since the 1980s, its ability to induce euphoric and hallucinogenic properties has led to widespread recreational use, particularly among young populations3,4. Long-term ketamine abuse frequently triggers a spectrum of lower urinary tract symptoms, including pollakiuria, urinary urgency, nocturia, and dysuria. This cluster of symptoms is clinically defined as ketamine-induced cystitis (KC)5. Although previous studies have linked KC pathogenesis to multiple factors, such as inflammatory activation6, oxidative stress7, and autophagic dysregulation, the precise underlying mechanism remains unclear2,8,9. Current clinical management for KC primarily relies on ketamine cessation and symptomatic relief medications. Regrettably, there are limited therapeutic options to ameliorate the disease or reverse pathological changes. In severe cases of long-term abuse, radical interventions (e.g., cystectomy) may be necessary, which severely impairs patients’ quality of life and places a substantial burden on healthcare systems10. Therefore, elucidating the pathogenesis of KC and identifying effective therapeutic targets are urgently needed to address this unmet clinical challenge.

The human body hosts an estimated 100 trillion gut microbiota-approximately ten times the number of human cells11. The relationship between the host and gut microbiota is a complex form of symbiosis. The intestinal epithelium and its secreted mucus provide a suitable environment for microbial colon ization. In return, the microbiota fulfill indispensable physiological functions, including decomposing dietary components indigestible by the human body, synthesizing beneficial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and vitamins), and acting as a defensive barrier against pathogen invasion12. Consequently, gut microbial metabolism constitutes an integral part of host metabolic homeostasis, exerting far-reaching effects on overall health. Importantly, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that the composition and structure of gut microbiota undergo perturbations in the context of various pathological conditions or metabolic dysregulations, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis13,14,15.

In recent years, advancements in 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomic sequencing technologies have significantly deepened understanding of the composition and structure complexity of the gut microbiota. Concurrently, research investigating the associations between gut microbiota and various diseases has garnered substantial attention16. Accumulating evidence has confirmed that gut microbiota and their metabolites play a critical role in the regulation of multiple diseases. This bidirectional crosstalk is commonly termed “the intestinal microbiota-gut-target organ axis”, with well-characterized examples including the intestinal microbiota-gut-lung axis17, the intestinal microbiota-gut-brain axis18, and the intestinal microbiota-gut-liver axis19. Within the field of urology, investigations into the interplay between the gut and urinary system have been on the rise. Some studies have demonstrated the bidirectional regulation between the gut and urinary system organs, leading to the proposal of concepts such as the gut-kidney axis20, and the gut-bladder axis21. Building upon the established role of gut microbiota in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and their documented interactions with distant organs-coupled with a growing body of evidence highlighting the critical involvement of gut microbiota and their metabolites in the development and progression of bladder diseases22,23,24, we hypothesize that gut microbiota and their metabolites contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of KC through the gut-bladder axis. However, current research on the involvement of intestinal microbiota and metabolites in cystitis remains limited, and the underlying mechanisms governing these interactions remain incompletely elucidated.

Advancements in metagenomic sequencing and untargeted metabolomics have enabled a more in-depth exploration of the relationship between gut microbiota, metabolites, and KC. Compared to 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomic sequencing provides a higher resolution, revealing both functional and taxonomic differences in gut microbiota at the species level25. Meanwhile, untargeted metabolomics allows for comprehensive profiling of alterations in small-molecule metabolite profiles, providing insights into the metabolic perturbations linked to KC26.

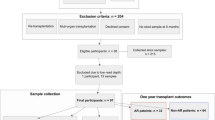

This study aims to characterize gut microbiota composition and metabolites in a rat model of KC using metagenomic sequencing and untargeted metabolomics (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we seek to elucidate the crosstalk mechanisms between gut microbiota and KC within the framework of the gut-bladder axis. By dissecting these interactions, this study intends to deepen our understanding of KC pathogenesis and potentially identify novel therapeutic targets.

Materials and methods

Sample collection, processing and experimental procedures

Animal grouping and medication administration

15 female Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (weighing 200 ± 5 g, n = 15) were obtained from the Animal Center of Guangxi Medical University. After one week of adaptive housing, the rats were randomly allocated to three groups: control, low-dose ketamine (LK), and high-dose ketamine (HK). The sample size was determined based on previous literature reports and experience27. Rats in the control group received intraperitoneal injection of normal saline, while those in the LK and HK groups received intraperitoneal injections of ketamine solution at 5 mg/kg/day and 25 mg/kg/day, respectively. The dosing regimen and duration (12 weeks) were established based on previous literature and pilot experiments28,29,30. Body weights were measured weekly, and ketamine doses were adjusted accordingly to maintain consistent weight and avoid under- or over-dosing throughout the study. Initially, 15 rats were randomly allocated to three groups (n = 5 per group): control, LK, and HK. Unfortunately, rats in the control (n = 1) and LK (n = 1) groups died unexpectedly during the experiment due to causes unrelated to ketamine administration. As a result, the final group sizes were 4 rats in the control group, 4 in the LK group, and 5 in the HK group. After 12 weeks of treatment, fecal samples were collected from all rats. Subsequently, all rats were anesthetized via inhalation of 4% isoflurane until reaching a deep anesthetic state (confirmed by the absence of corneal reflex and loss of response to paw pinch). Following anesthesia, blood was collected from the orbital venous plexus. The rats were then euthanized by cervical dislocation, after which subsequent samples (including bladder and intestinal tissues) were harvested. All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Department of Urology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, in accordance with the institution’s ethical guidelines (Approval Number: 2024-E552-01). Ketamine was sourced from Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. All methods were carried out according to relevant guidelines and regulations and are reported under the ARRIVE guidelines.

Sample collection and data preprocess

Following the 12-week treatment period, fresh fecal samples were collected. To ensure sterility during collection, individual rats were housed in a clean, sanitized cage prior to sampling. Fecal samples were obtained by gently massaging the abdomen to stimulate defecation and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analysis. For untargeted metabolomic analysis, fecal samples were analyzed using a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany) coupled with an Orbitrap Q Exactive™HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) (See details in “Untargeted metabolomics” section Untargeted metabolomics). For metagenomic analysis, DNA was extracted from fecal samples, followed by metagenomic sequencing. To prepare libraries compatible with Illumina sequencing, the extracted DNA was fragmented using sonication to a size of approximately 350 base pairs (bp) suitable for Illumina sequencing. This was followed by additional PCR amplification, size selection, and purification. The constructed library was then quantified using a Qubit® and real-time PCR for accurate measurement and analyzed using a bioanalyzer to assess size distribution. Based on the effective library concentration and required data amount, qualified libraries were pooled and sequenced on Illumina sequencing platforms (See details in “Metagenomics” section Metagenomics).

Blood samples were subsequently collected from the orbital venous plexus of rats under deep inhalation anesthesia with 4% isoflurane. The collected blood was centrifuged at 4 °C to separate and isolate serum. Following blood sampling, rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation according to institutional guidelines. A necropsy was performed, and bladder and colon tissues were carefully dissected and collected. A portion of each tissue sample was allocated for histological examination using Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, Alcian blue-periodic acid Schiff (AB-PAS) staining, and immunohistochemistry (IHC). The remaining tissue samples were stored at -80 °C for future experimental analyses.

H&E staining, AB-PAS staining and IHC

Histological examinations were performed on bladder and colon tissues from all experimental groups. H&E staining was performed to evaluate general tissue morphology in both bladder and colon tissues. Additionally, AB-PAS staining was applied to colon tissues for more detailed histological assessment. For bladder tissues, IHC was carried out to detect the expression levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Reagents and equipment for H&E and AB-PAS staining were obtained from Servicebio (Wuhan, China). Reagents and equipment for IHC staining and image acquisition were provided by Aifang Biological (Changsha, China).

Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF staining was performed to detect the expression of Zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) and Mucin 2 (MUC-2) in colon tissue sections. Antibodies, reagents, and equipment for the IF procedure were obtained from Servicebio (Wuhan, China). The intensity of IF signals for ZO-1 and MUC-2 was quantified using ImageJ software and normalized for subsequent analysis.

Measurement of IL-1β and TNF-α in the serum

Serum concentrations of IL-1β and TNF-α were quantified using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Mlbio, Shanghai) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol31.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from bladder tissue using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The extracted RNA was then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Beijing, China). Quantitative analysis of gene expression was performed using the Fast Start Essential DNA Green Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, USA) on a LightCycler 96 real-time PCR instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Relative mRNA quantities were determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Cell culture and treatment

The SV-HUC-1 cell line, obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, was cultured in Ham’s F-12 K medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, China) and Penicillin–Streptomycin Liquid (Solarbio, Beijing) under controlled conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). When the cells reached approximately 80% confluency, the culture medium was replaced for all experimental groups. Cells in the control group were treated with phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS). For the ketamine, Stachydrine and Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) groups, cells were exposed to 2 mmol/L ketamine solution. Stachydrine was purchased from Solarbio (Solarbio, Beijing). PQQ was purchased from Aladdin (Aladdin, Shanghai)27. Additionally, the Stachydrine and PQQ groups were further supplemented with their respective test compounds (32 μmol/L Stachydrine, 32 nmol/L PQQ), with the final concentration of ketamine maintained at 2 mmol/L to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of stachydrine and PQQ. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, RNA was extracted from all groups for subsequent RT-qPCR analysis.

Data analysis and statistical methods

Untargeted metabolomics

The raw data files were processed to perform peak alignment, peak picking, and quantitation for each metabolite. The raw quantitative results were normalized using the formula: sample raw quantitation value / (The sum of sample metabolite quantitation value/The sum of quality control (QC) 1 sample metabolite quantitation value). Finally, metabolites with a coefficient of variation (CV) < 30% in QC samples were retained as the final identified results for subsequent analyses. Pearson correlation coefficients between QC samples were calculated based on the relative quantitative values of the metabolites. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to visualize the overall metabolic profiles and identify group separation. To identify metabolites associated with the observed phenotypic variations, Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) analysis was utilized. Metabolites with VIP scores > 1 and statistically significant differential abundance (p < 0.05) were selected for subsequent visualization in a heatmap analysis. These significantly altered metabolites subsequently underwent K-means clustering analysis to elucidate potential pathway co-regulation pathways. Finally, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (Version: 2023.02) was used to explore the functional roles and associated pathways of these significant metabolites32,33,34.

Metagenomics

Raw data obtained from sequencing were preprocessed to generate clean data for subsequent analyses. The specific processing steps were as follows: (a) removing reads containing low-quality bases (quality score ≤ 38) exceeding a certain proportion (default setting: 40 bp); (b) removing reads with N bases reaching a certain proportion (default setting: 10 bp); (c) removing reads with overlap with adapters exceeding a certain threshold (default setting: 15 bp). After preprocessing, the clean data were assembled using the MEGAHIT software and the assembled Scaffolds were split at the junctions containing N bases to generate Scaftigs without N bases. Next, Open Reading Frame (ORF) prediction was performed on Scaftigs (≥ 500 bp) from each sample using MetaGeneMark (http://topaz.gatech.edu/GeneMark/), followed by filtering of sequences shorter than 100 nucleotide (nt) and redundancy reduction was applied to the ORF prediction results using the CD-HIT software (http://www.bioinformatics.org/cd-hit) to construct an initial gene catalogue.

Subsequently, clean data from each sample were mapped to the initial gene catalogue using Bowtie2 (parameters: -end-to-end, -sensitive, -I 200, -X 400), and the number of reads mapped to each gene was calculated. Genes with mapped reads ≤ 2 in each sample were filtered out to obtain the final gene catalogue (Unigenes) for subsequent analyses, based on which gut microbiota taxonomic annotation was further performed using the Non-Redundant Protein Sequence Database database (Version: 2023.03) of NCBI. To investigate the complexity of species diversity within the samples, α-diversity analysis was employed using four indices: Ace, Chao1, Shannon and Simpson. β-diversity analysis, analyzed using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) and Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS), was used to identify distinctions in species variety among samples. For functional and differential analyses, the metagenomic sequencing data and the KEGG database (Version: 2023.02) were employed for functional prediction of the gut microbiota32,33,34. Differences in bacteria and in functional pathways between groups at each taxonomic levels were then computed using Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) implemented in the LEfSe software35.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.0, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess significant differences in cytokine levels within bladder tissue and serum across all groups. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and variance homogeneity was assessed using the Welch’s ANOVA test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were then calculated to evaluate potential correlations between cytokines, differentially abundant gut microbiota, and metabolites within each group. The correlation coefficient (r) and false discovery rate (FDR) values were used to describe the strength and significance of these correlations, respectively. The Benjamini—Hochberg method was employed for FDR correction. Finally, a network visualization was generated using Cytoscape 3.10.2 to effectively depict these relationships36.

Results

Ketamine-induced cystitis in rats

To verify the successful establishment of the KC rat model, we evaluated pathological changes and inflammatory factors expression in bladder tissues. H&E staining demonstrated that, compared with the control group, the arrangement and structure of the bladder epithelial mucosa were disrupted in both the LK and HK groups. Additionally, the HK group exhibited atrophy of bladder epithelium. In both the LK and HK groups, varying degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration and vascular proliferation were observed in the mucosal and submucosal layers of the bladder (Fig. 2A). IHC further demonstrated increased protein expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in the LK and HK groups (Fig. 2B). To support these findings, RT-qPCR was employed to quantify changes in mRNA expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in bladder tissues of the three groups. Compared with the control group, we observed significant upregulation of both inflammatory factors in the LK and HK groups, with a more pronounced effect in the HK group (TNF-α: LK: 1.275 ± 0.03651, HK: 2.672 ± 0.3753; LK vs. control: p = 0.0136, HK vs. control: p = 0.0266, LK vs. HK: p = 0.043. IL-1β: LK: 1.371 ± 0.1441, HK: 1.804 ± 0.05886; HK vs. control: p = 0.0001. Figure 2C). Based on previous literature reporting elevated serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in patients with KC37, we utilized ELISA to detect changes in these serum inflammatory factors across the three groups. Consistent with the changes observed in bladder tissue, the serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β exhibited similar trends across the three groups (TNF-α: LK: 460.5 ± 8.797, HK: 504.7 ± 14.97; LK vs. control: p = 0.0038, HK vs. control: p = 0.0071. IL-1β: LK: 124.2 ± 5.787, HK: 155.7 ± 5.601; LK vs. control: p = 0.0002, HK vs. control: p < 0.0001, LK vs. HK: p = 0.0185; Fig. 2D).

Ketamine-induced cystitis in rats. (A) H&E staining of the bladder (10 and 20 × , animals in the control, LK, and HK groups). (B) IHC of TNF-α and IL-1β (10 ×) in each group. (C) TNF-α and IL-1β expression in the bladder tissue of each group. (D) Serum TNF-α and IL-1β expression in each group. The points represent individual measurements, and the bars represent the maximum and minimum values. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance was assessed using the Welch’s ANOVA test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with the control group.

Intestinal structure and functional impairment in KC rats

Based on previous observations of altered intestinal environments in various bladder diseases, including compromised structural and functional integrity of the intestinal wall38, we investigated potential changes in the colons of our KC rat model. H&E staining revealed varying degrees of inflammatory changes, such as inflammatory cell infiltration, in the colonic epithelium of the LK and HK groups compared with the control group (Fig. 3A). AB-PAS staining demonstrated a reduction in the abundance of goblet cells and shortened colonic gland length in both the LK and HK groups compared to the control group (Fig. 3B). IF staining for ZO-1 and MUC-2 demonstrated lower expression levels of these proteins in the LK and HK groups than in the control group (Fig. 3C, D). Quantitative analysis of the IF data confirmed significantly lower fluorescence intensity of ZO-1 and MUC-2 in the LK and HK groups compared with the control group, indicating compromised intestinal structure and function in KC rats (ZO-1: LK: 0.8223 ± 0.04637, HK: 0.7444 ± 0.02982; LK vs. control: p = 0.0108, HK vs. control: p = 0.001. MUC-2: LK: 0.7827 ± 0.01738, HK: 0.5824 ± 0.03394; HK vs. control: p = 0.003; Fig. 3E, F).

Intestinal structure and function injury in KC rats. (A) H&E staining of the colon in each group (5 and 10 ×). (B) AB-PAS staining of the colon in each group (10 and 20 ×). (C) IF of ZO-1 in the colon. (D) IF of MUC-2 in the colon. (E) Relative quantification of IF intensity of ZO-1. (F) Relative quantification of IF intensity of MUC-2. The points represent individual measurements, and the bars represent the maximum and minimum values. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance was assessed using the Welch’s ANOVA test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with the control group.

Disorder of gut microbiota in KC rats

To further explore the potential association between intestinal dysregulation and gut microbiota in KC, we performed metagenomic analysis on fecal samples collected from the KC rats. First, α-diversity analysis was conducted at the species level to assess species richness and evenness within each group (Fig. 4A). The Ace and Chao1 indices, reflecting species abundance, were significantly higher in the control group than in the LK and HK groups (Ace: LK: 5491 ± 121.7, HK: 5062 ± 164.5; LK vs. control: p = 0.0441, HK vs. control: p = 0.0089; Chao1: LK: 5549 ± 120.1, HK: 5075 ± 172.7; LK vs. control: p = 0.0443, HK vs. control: p = 0.0092). In contrast, the Shannon and Simpson indices, which measure species diversity, did not show significant differences among the groups. Subsequently, β-diversity analysis was performed at the species level to compare the overall microbial community composition across the three groups (Fig. 4B). PCoA revealed distinct clustering patterns among the control, LK, and HK groups, with PCoA1 and PCoA2 explaining 33.82% and 26.24% of the variation, respectively. Similarly, Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis demonstrated clear separation among the three groups, further confirming significant shifts in gut microbiota composition in KC rats (Stress = 0.051). Both PCoA and NMDS were generated based on the Bray–Curtis distance metric, and their p-values and F-values were listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Composition of gut microbiota in KC rats. (A) α-diversity analysis. (B) PCoA and NMDS analysis. (C) Tree cluster Bray–Curtis distance analysis showed the top 10 species in relative abundance at the phylum level. (D) Top 10 species in relative abundance at the genus level. (E) Top 10 species in relative abundance at the species level. (F) Dominant differential microbiota in each group at the species level. LDA score > 4 and p-value < 0.05. The length of the bar graph represents the effect size of the differential species. The points represent individual measurements, and the bars represent the maximum and minimum values. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance was assessed using the Welch’s ANOVA test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared with the control group.

To further characterize the taxonomic composition of the gut microbiota, a phylogenetic tree based on Bray–Curtis distance was constructed for the top 10 most abundant phyla (Fig. 4C). This analysis revealed a clear separation among the control, LK, and HK groups, indicating distinct microbial communities across the three groups. The legend identifies the top 10 most abundant phyla in each group. Notably, Bacillota and Bacteroidota were the dominant phyla, accounting for approximately 70% of the total bacterial abundance. Additional analyses were conducted to investigate the relative abundance of bacterial taxa at the genus level (Fig. 4D) and species level (Fig. 4E). At the genus level, Bacteroides was the most abundant genus, with relative abundances of 23.12% (control group), 28.38% (LK group), and 48.50% (HK group), respectively. At the species level, the dominant species were identified as Lachnospiraceae bacterium and Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, with relative abundances of 34.86% (control group), 41.56% (LK group), 23.58% (HK group) and 0.23% (control group), 89.16% (LK group), 10.61% (HK group), respectively.

To identify microbiota with differential abundance across taxonomic levels, LEfSe analysis was conducted on enriched taxa at all levels (Fig. 4F). The Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) score threshold was set to 4.0 to highlight species with significant differences between the three groups. By leveraging the high resolution of metagenomic sequencing, LEfSe analysis revealed the enrichment of specific bacterial taxa in the LK or HK groups compared with the control group. Notably, these enriched taxa included some previously reported pro-inflammatory species such as Desulfovibrio and Treponema39,40. In contrast, beneficial microbiota, such as Lactobacillus intestinalis and Roseburia hominis, which are known for their protective and reparative effects on the gut, exhibited reduced abundance compared with the control group41,42. Collectively, these findings suggest that the gut microbiota is disrupted in KC rats, which may contribute to the observed gut injury and increased permeability.

Prediction of intestinal microbial function in KC rats

To elucidate the functional consequences of changes in gut microbiota composition in KC rats, KEGG enrichment analysis was performed on the annotated microbial sequences. At KEGG level 2 (broad functional categories), the top 10 enriched pathways included carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, translation, membrane transport, metabolism of cofactors and vitamins, energy metabolism, glycan biosynthesis and metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, replication and repair, and signal transduction (Fig. 5A). Similarly, at KEGG level 3, the most significantly enriched pathways included ABC transporters, ribosomes, the two-component system, purine metabolism, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, starch and sucrose metabolism, quorum sensing, pyrimidine metabolism, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that the gut microbiota in KC rats not only contributes to various nutritional metabolic processes but potentially plays a role in the synthesis and metabolism of essential cell cycle-related substances. To characterize functional alterations associated with KC progression, a LEfSe analysis was performed to identify differentially enriched KEGG pathways (LDA score > 2.5 and p-value < 0.05). As visualized in a functional clustering heatmap (Fig. 5C), distinct functional differences between the control group and the HK were highlighted. Additionally, the LK group exhibited a functional profile that appeared to be intermediate between those functions of the control and HK groups. The contribution degree of each enriched differential function was further analyzed (Fig. 5D). We found that both the LK and HK groups demonstrated enrichment in multiple pathways associated with diverse metabolic processes, including fatty acid biosynthesis, glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism, pyruvate metabolism, valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis, as well as histidine metabolism. This functional analysis underscores the intimate association between the gut microbiota and metabolic processes in the context of this study. The observed functional shifts provide insights into the potential mechanisms by which the gut microbiota may influence host metabolism under different ketamine treatment conditions.

Prediction of intestinal microbial function in KC rats. (A) Distributions of relative abundances of KEGG level 2 pathway categories in control, LK, and HK groups. (B) Distributions of relative abundances of KEGG level 3 pathway categories in control, LK, and HK groups. (C) Abundance clustering heatmap of differentially enriched functions at KEGG level 3. (D) Differentially enriched functions of each group at KEGG level 3.

Changes in the fecal metabolic profile of KC rats

Building on the metagenomic functional prediction, which suggests a close link between gut microbiota and metabolism in KC, untargeted metabolomic analysis was performed on fecal samples from the KC rats to investigate the potential crosstalk between gut microbiota and KC. The Pearson correlation coefficients of QC samples were all close to 1, indicating that the entire detection process had good stability and high data quality (Supplementary Fig. 1). Figure 6A depicts the class-level distribution of the annotated metabolites. PCA of the entire metabolite profile revealed clear separation among the three groups, with PC1 and PC2 explaining 24.49% and 16.37% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, ANOVA identified 104 differential metabolites. The relative abundance of these metabolites was normalized via z-score standardization and then clustered into four distinct groups by K-means clustering (Fig. 6C). A heatmap visualization of the K-means clustering results is presented in Fig. 6D. Functional enrichment analysis of the differential metabolites using KEGG revealed that these metabolites are primarily enriched in pathways related to vitamin B6 metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, primary bile acid biosynthesis, and bile secretion (Fig. 6E). Scatter plots were generated using the ImageGP platform (https://www.bic.ac.cn/BIC/#/) for further analysis43.

Changes in the fecal metabolic profile of KC rats. (A) The proportion of the metabolites that were annotated in class I. (B) PCA analysis of total metabolites. (C) Line plot of K-Means classification results. (D) Heatmap of K-Means clustering of differential metabolites. (E) KEGG analysis of differential metabolites.

Correlations of KC, differential metabolites and gut microbiota

LEfSe analysis identified a total of 46 representative differentially abundant microbiota at the species level across the three groups, including Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, Erysipelotrichaceae bacterium OPF54, Firmicutes bacterium CAG: 424, Phocaeicola sartorii and so on. Notably, the control group harbored 19 dominant microbial species, while the LK and HK groups harbored 16 and 11 dominant microbial species, respectively. Spearman’s correlation analysis and FDR correction were employed to assess the relationship between the RT-qPCR results for TNF-α and IL-1β in the bladder tissue of KC rats and 46 KC-associated differential microbiota (Fig. 7A). This analysis revealed significant positive or negative correlations between these inflammatory factors and 22 of the 46 differential microbiota (pFDR < 0.05). 13 differential metabolites exhibiting significant changes across all three groups were further selected from the 104 identified metabolites. Similar to the microbiota analysis, Spearman’s correlation analysis and FDR correction were performed to evaluate the relationship between these 13 differential metabolites and the RT-qPCR results of TNF-α and IL-1β in the bladder tissue of KC rats (Fig. 7B; pFDR < 0.05). Six of the 13 metabolites displayed significant correlations with the inflammatory factors. Among these, 2-[5-(2-hydroxypropyl)oxolan-2-yl]propanoic acid, 4-[(4-phenethyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)sulfonyl]-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole, DL-Stachydrine, Quinoline, and Sedanolide all exhibited negative correlations with inflammatory factor levels, suggesting a potential protective role. Conversely, N-(1-benzylpiperidin-4-yl)-5-methoxy-1H-indole-2-carboxamide exhibited a positive correlation with inflammatory factor levels. Finally, statistically significant differential metabolites (n = 6) and differential microbiota (n = 22) were combined to perform Spearman’s correlation analysis and FDR correction (Fig. 7C; pFDR < 0.05). Further network analysis was performed to elucidate the intricate relationships between inflammatory factors, the identified differential metabolites and the differential gut microbiota, which showed correlations of KC, differential metabolites and gut microbiota (Fig. 7D). In the network of Fig. 7D, the central red rectangles in the center represent the inflammatory factors, the green rectangles indicate metabolites and the outermost blue rectangles represent gut microbiota. Dashed blue lines represent the negative correlation, the solid red lines represents the positive correlation, and the thickness of the line indicates the degree of correlation.

Correlations of KC, differential metabolites, and gut microbiota. (A) The correlation between TNF-α, IL-1β, and 46 differential microbiota. The direction of the elliptical shape and color represents the positive and negative correlation coefficient, the area on behalf of the correlation coefficient. (B) The correlation between TNF-α, IL-1β, and 13 differential metabolites. (C) The correlation between KC-related differential metabolites and KC-related differential microbiota. (D) Correlation network between KC-related inflammatory factors (n = 2), statistically significant differential metabolites metabolites (n = 6) and differential microbiota (n = 12). (E) Validation of anti-inflammatory effects of Stachydrine and PQQ in vitro (n = 3). Spearman and ANOVA analysis of variance, and the bars represent the means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Validation of anti-inflammatory effects of metabolites

Correlation analysis identified several metabolites that exhibited negative correlations with inflammatory factors. Based on these findings, we purchased Stachydrine, which is already commercially available, and investigated its potential anti-inflammatory effects via in vitro experiments, as reported previously44,45. Additionally, PQQ, a compound with established anti-inflammatory effects, was included for comparison46. To validate the anti-inflammatory efficacy of these metabolites in the context of KC, we established a KC cell model using the SV-HUC-1 cell line and measured the levels of inflammatory factors. RT-qPCR results demonstrated that ketamine treatment increased inflammatory responses in SV-HUC-1 cells. Conversely, Stachydrine and PQQ significantly reduced the elevated levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, suggesting their potential therapeutic effects in KC by mitigating inflammation (TNF-α: Ketamine: 2.791 ± 0.3456, Stachydrine: 1.220 ± 0.05766, PQQ: 1.330 ± 0.1940; Ketamine vs. control: p = 0.0011, Ketamine vs. Stachydrine: p = 0.0024, Ketamine vs. PQQ: p = 0.0038. IL-1β: Ketamine: 3.012 ± 0.2465, Stachydrine: 1.076 ± 0.08595, PQQ: 1.104 ± 0.1303; Ketamine vs. control: p < 0.0001, Ketamine vs. Stachydrine: p < 0.0001, Ketamine vs. PQQ: p < 0.0001. Figure 7E).

Discussion

This study demonstrated alterations in gut microbiota composition and metabolite profiles in KC rats. These alterations in gut microbiota composition likely influenced the composition of fecal metabolites to some extent. Therefore, correlation analysis was employed to elucidate the relationships among differential microbiota, altered metabolism, and KC. Untargeted metabolomics revealed negative correlations between certain metabolites, such as DL-Stachydrine, which possesses well-documented anti-inflammatory properties and inflammatory factors44,45. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of Stachydrine and PQQ were validated in a KC cell model established using the SV-HUC-1 cell line. Collectively, these data suggest that gut microbiota composition and metabolites may influence KC development via the gut-bladder axis. This study provides novel insights into the contribution of gut-bladder axis to KC pathogenesis and identifies potential therapeutic targets for the disease.

Our KC rat model not only exhibited pathological changes in bladder tissue but also revealed structural and functional abnormalities within the colon tissue. This gut-bladder comorbidity suggests a potential communication pathway, possibly mediated by the gut-bladder axis. The observed intestinal dysbiosis in KC rats further supports this hypothesis. Research on the gut-bladder axis has increased significantly in recent years, although the precise mechanisms remain under investigation. Studies have consistently demonstrated disruptions in intestinal function and the gut microbiota composition in various bladder diseases, particularly bladder cancer. For example, a case–control study by He et al. reported compromised intestinal structural integrity of the intestine in bladder cancer patients. Furthermore, their fecal analysis revealed a decrease in the abundance of Clostridium cluster XI and Prevotella, as well as a reduction in butyric acid concentration, compared to healthy controls38. Additionally, a metagenomic and metabolomic analysis of fecal samples from bladder cancer patients in China identified shifts in both gut microbiota composition and metabolite fecal profiles47. Beyond observational studies, recent Mendelian randomization analyses have linked specific gut microbiota, such as Bifidobacterium, Actinobacteria, and Ruminococcustorques, to an increased risk of bladder cancer48,49. While research on gut function and gut microbiota alterations in cystitis is limited, recent evidence suggests an association between intestinal dysfunction, microbial imbalances, recurrent cystitis and overactive bladder50,51. In addition, enteric-derived bacteria are established pathogenic factors in urinary tract infections (UTIs)52. Worby et al. proposed that disruption of the gut-bladder axis is a key factor influencing susceptibility to UTIs. Increased intestinal permeability is widely believed to facilitate the translocation and colonization of Escherichia coli in the adjacent urinary tract and bladder53, ultimately contributing to the development of UTI. Studies have shown a correlation between the abundance of enteric Escherichia coli in patients with UTI and the progression of Escherichia coli-mediated UTIs54,55. Further supporting the existence and importance of the gut-bladder axis, Tariq et al. demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile infection resulted in a reduced frequency of recurrent UTIs56.

In a healthy state, the gut microbiota maintains a relatively stable equilibrium with its surrounding environment and secretions57. However, various factors, including disease states and antibiotic administration, can disrupt this delicate balance. Such disruptions can induce a cascade of detrimental effects, including chronic local intestinal inflammation, the intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction, and the proliferation of harmful bacterial strains58. Notably, metabolites serve as crucial intermediaries that facilitate communication between the gut microbiota and distant organs59. Intestinal barrier damage can lead to the influx of gut microbiota-derived metabolites into systemic circulation60,61. Fecal metagenomic sequencing of our KC rats revealed alterations in the abundance of gut microbiota compared with the control group. For instance, at the genus level, the relative abundance of clostridium gradually decreased (Control: LK: HK = 48.85%: 29.04%: 22.11%) with the increasing ketamine exposure. Clostridium is well known for its role in host metabolism, particularly in producing SCFAs that exert anti-inflammatory and gut-protective effects18. The reduction in Clostridium abundance suggests that the stability and function of the host gut environment deteriorate with higher ketamine doses. At the species level, Bifidobacterium pseudolongum (Control: LK: HK = 0.23%: 89.16%: 10.61%) was more abundant in the LK group but less abundant in the HK group. This species is involved in immune regulation and secretes acetate, which exerts anti-inflammatory and antitumor effects. Additionally, inosine derived from Bifidobacterium pseudolongum has been reported to promote Th1 cell differentiation under specific conditions, thereby enhancing immune checkpoint blockade therapy and exerting antitumor effects62. The opportunistic pathogen Dorea sp. CAG:317 (genus Dorea) (Control: LK: HK = 4.92%: 4.50%: 90.58%) exhibited increased abundance in the HK group, mirroring findings from a metagenomic study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome63. Intestinal environmental disorders are primarily characterized by degradation of the intestinal wall structure, often accompanied by a decline in mucin secretion function64. In the present study, reduced expression levels of ZO-1 and MUC-2 in KC rats suggested potential impairment of intestinal barrier function. Furthermore, we observed a downregulation in the abundance of Eubacterium plexicaudatum (Control: LK: HK = 67.30%: 20.52%: 12.18%) in the HK group. This bacterium produces SCFAs, which are essential for human health65. SCFAs, the primary end products of gut microbial fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates, play a critical role in maintaining the integrity of the colonic epithelial structure and enhancing ZO-1 expression, and reinforcing intestinal barrier function66,67. Notably, previous studies have reported reduced SCFA concentrations in bladder diseases, suggesting that the downregulation of SCFAs may be a significant factor in the pathogenesis of these conditions38,53. In this respect, Wang et al. demonstrated that supplementation with butyrate-producing probiotics can ameliorate bladder epithelial injury in mice with bladder cancer68. Interestingly, our study identified an upregulation of certain bacteria associated with SCFA production or promotion in the HK group, including Phocaeicola faecalis (Control: LK: HK = 4.28%: 0.33%: 95.39%), Phocaeicola sartorii (Control: LK: HK = 5.42%: 6.78%: 87.80%), and Bifidobacterium animalis (Control: LK: HK = 0.46%: 30.88%: 68.65%) (Fig. 4F)69,70,71. This seemingly contradictory finding may be explained by the inherent regulatory capacity of the gut, which is highly dependent on the diversity of the intestinal microbiota72. The interplay between different microbial species, characterized by antagonism or cooperation, contributes to the stability of the intestinal environment. While external disturbances can disrupt this homeostasis, leading to an unbalanced state, the system may attempt to return to its initial equilibrium. However, the intensity and duration of external disturbances ultimately determine whether a new balanced state is established or the imbalance progresses toward a disease-associated state73. In light of these considerations, we propose that the increased abundance of probiotic bacteria in the KC group may represent an attempt by the gut and its microbiota to self-regulate and achieve a new equilibrium in response to the chronic inflammatory state associated with KC.

Metabolites serve as critical mediators within the gut-bladder axis, modulating inflammation and immune responses by regulating the expression of downstream cytokines and the activity of immune cells. Among these metabolites, SCFAs are recognized for their immunomodulatory properties, influencing pathways such as NF-κB activation and T regulatory (Treg) cell differentiation, which help balance inflammatory responses. Additionally, SCFAs can modulate macrophage polarization, promoting an anti-inflammatory phenotype associated with increased IL-10 secretion74,75. As previously mentioned, butyrate supplementation has been shown to alleviate bladder injury, potentially by inhibiting the activation of M0 macrophage into M1 macrophages66. Moreover, SCFAs promote the polarization of M2 macrophages in mice, leading to increased secretion of IL-10 and an anti-inflammatory response76. Beyond SCFAs, our study identified Sedanolide, a metabolite that can inhibit the FXR signaling pathway and reshape the intestinal flora by regulating bile acid metabolism77. Additionally, previous research has demonstrated that glycocholic acid inhibits macrophage migration and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines78. Conversely, some metabolites, such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), can exacerbate inflammation by promoting the release of cytokines and chemokines in bladder epithelial cells, thereby facilitating the colonization of Escherichia coli and exacerbating urinary tract infections79. These findings further support the existence of the gut-bladder axis and highlight how metabolites regulate the activity of immune cell activity and the production of inflammatory mediators. Consistently, our study observed elevated IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression in LK and HK groups, suggesting that, gut microbiota-derived metabolites contribute to bladder inflammation by modulating immune signaling pathways in KC rats.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, despite the strict control of experimental conditions and optimization of statistical strategies, the sample size in each group was relatively small. This may result in greater intra-group variability than inter-group variability among certain microbiota or metabolites, thereby precluding the identification of truly differential microbial species or metabolites. Further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to conclusively evaluate the potential of specific microbial microbiota and metabolites as biomarkers for the diagnosis or treatment of KC. Second, the lack of data from KC patients necessitates further investigation into the alterations in intestinal microbiota composition and metabolites in fecal and serum samples from this population. Additionally, this study did not investigate potential changes in serum metabolites profiles. Finally, while this study integrates metabolomic and gut microbiota data in the context of KC, it does not establish a causal link between specific gut microbiota and KC development via the gut-bladder axis. We aim to address this limitation in future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study employed metagenomic and untargeted metabolomic analyses to demonstrate dysregulation of gut microbiota composition and metabolite profiles in KC rats. We further explored the potential crosstalk between gut microbiota and the bladder through the gut-bladder axis, thereby providing novel insights into the intricate relationship between gut microbiota and pathogenesis of KC.

Data availability

The data reported in this study have been deposited in the OMIX, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences under accession number OMIX009697 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/release/OMIX009697) and under accession number CRA024662 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA024662). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Hua Mi, upon reasonable request.

References

Boese, M. et al. Effects of mild closed-head injury and subanesthetic ketamine infusion on microglia, axonal injury, and synaptic density in Sprague-Dawley rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 4287 (2024).

Chen, C.-L., Wu, S.-T., Cha, T.-L., Sun, G.-H. & Meng, E. Molecular pathophysiology and potential therapeutic strategies of ketamine-related cystitis. Biology 11, 502 (2022).

Li, L. & Vlisides, P. E. Ketamine: 50 Years of Modulating the Mind. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 612 (2016).

Orhurhu, V. J., Vashisht, R., Claus, L. E. & Cohen, S. P. Ketamine Toxicity. in StatPearls [Internet] (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Chu, P.S.-K. et al. The destruction of the lower urinary tract by ketamine abuse: A new syndrome?. BJU Int. 102, 1616–1622 (2008).

Jhang, J.-F., Hsu, Y.-H., Jiang, Y.-H. & Kuo, H.-C. Elevated serum IgE may be associated with development of ketamine cystitis. J. Urol. 192, 1249–1256 (2014).

Liu, K.-M. et al. Ketamine-induced ulcerative cystitis and bladder apoptosis involve oxidative stress mediated by mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 309, F318-331 (2015).

Lu, J.-H. et al. Autophagy alters bladder angiogenesis and improves bladder hyperactivity in the pathogenesis of ketamine-induced cystitis in a rat model. Biology 10, 488 (2021).

Chen, C.-H., Lee, M.-H., Chen, Y.-C. & Lin, M.-F. Ketamine-snorting associated cystitis. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 110, 787–791 (2011).

Zhou, J., Scott, C., Miab, Z. R. & Lehmann, C. Current approaches for the treatment of ketamine-induced cystitis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 42, 680–689 (2023).

Bäckhed, F., Ley, R. E., Sonnenburg, J. L., Peterson, D. A. & Gordon, J. I. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307, 1915–1920 (2005).

Miller, T. L. & Wolin, M. J. Pathways of acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal microbial flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 1589–1592 (1996).

Zhang, C. et al. Dietary Modulation of Gut Microbiota Contributes to Alleviation of Both Genetic and Simple Obesity in Children. EBioMedicine 2, 968–984 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Gut microbiome fermentation determines the efficacy of exercise for diabetes prevention. Cell Metab 31, 77-91.e5 (2020).

Milosevic, I. et al. Gut-liver axis, gut microbiota, and its modulation in the management of liver diseases: A review of the literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 395 (2019).

Scheithauer, T. P. M. et al. Gut microbiota as a trigger for metabolic inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Front. Immunol. 11, 571731 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Intestinal microbiota—An unmissable bridge to severe acute pancreatitis-associated acute lung injury. Front. Immunol. 13, 913178 (2022).

Zheng, M. et al. Probiotic Clostridium butyricum ameliorates cognitive impairment in obesity via the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Brain Behav. Immun. 115, 565–587 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Multi-omics reveals diet-induced metabolic disorders and liver inflammation via microbiota-gut-liver axis. J Nutr. Biochem. 111, 109183 (2023).

Nery Neto, J. A. O., Yariwake, V. Y., Câmara, N. O. S. & Andrade-Oliveira, V. Enteroendocrine cells and gut hormones as potential targets in the crossroad of the gut-kidney axis communication. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1248757 (2023).

Leue, C. et al. Functional urological disorders: A sensitized defence response in the bladder-gut-brain axis. Nat. Rev. Urol. 14, 153–163 (2017).

Vaughan, M. H. et al. The urinary microbiome in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J. Urol. 206, 1222–1231 (2021).

Worby, C. J., Olson, B. S., Dodson, K. W., Earl, A. M. & Hultgren, S. J. Establishing the role of the gut microbiota in susceptibility to recurrent urinary tract infections. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e158497 (2022).

Yang, H. J., Kim, D. S., Lee, K. W. & Kim, Y. H. The urinary microbiome; axis crosstalk and short-chain fatty acid. Diagnostics 12, 3119 (2022).

Quince, C., Walker, A. W., Simpson, J. T., Loman, N. J. & Segata, N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 833–844 (2017).

Zheng, Z. et al. Integrated microbiome and metabolome analysis reveals novel urinary microenvironmental signatures in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome patients. J. Transl. Med. 21, 266 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Mitochondrial damage causes inflammation via cGAS-STING signaling in ketamine-induced cystitis. Inflamm. Res. 74, 6 (2025).

Wu, P., Shan, Z., Wang, Q., Huang, J. & Zheng, S. Involvement of mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in urothelium in ketamine-associated urinary dysfunction. Am. J. Med. Sci. 349, 344–351 (2015).

Shen, C.-H. et al. Ketamine-induced bladder dysfunction is associated with extracellular matrix accumulation and impairment of calcium signaling in a mouse model. Mol. Med. Rep. 19, 2716–2728 (2019).

Zhu, Q. et al. Ketamine induced bladder fibrosis through MTDH/P38 MAPK/EMT pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 743682 (2022).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 29–34 (1999).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 12, R60 (2011).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Fan, G.-Y. et al. The immunomodulatory imbalance in patients with ketamine cystitis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, e2329868 (2017).

He, C. et al. Gut microbial composition changes in bladder cancer patients: A case-control study in Harbin China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 29, 395–403 (2020).

Xie, R. et al. Desulfovibrio vulgaris interacts with novel gut epithelial immune receptor LRRC19 and exacerbates colitis. Microbiome 12, 4 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Porphyromonas, treponema, and Mogibacterium promote IL8/IFNγ/TNFα-based pro-inflammation in patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Oral Microbiol. 13, 1851112 (2020).

Wang, Q.-W. et al. Lactobacillus intestinalis primes epithelial cells to suppress colitis-related Th17 response by host-microbe retinoic acid biosynthesis. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303457 (2023).

Patterson, A. M. et al. Human gut symbiont Roseburia hominis promotes and regulates innate immunity. Front. Immunol. 8, 1166 (2017).

Chen, T., Liu, Y.-X. & Huang, L. ImageGP: An easy-to-use data visualization web server for scientific researchers. iMeta 1, e5 (2022).

Yu, J. et al. Stachydrine relieved the inflammation and promoted the autophagy in diabetes retinopathy through activating the AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 16, 2593–2604 (2023).

Karim, M. R. et al. A network pharmacology and molecular-docking-based approach to identify the probable targets of short-chain fatty-acid-producing microbial metabolites against kidney cancer and inflammation. Biomolecules 13, 1678 (2023).

Sagar, S. et al. Obesity impairs cardiolipin-dependent mitophagy and therapeutic intercellular mitochondrial transfer ability of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 14, 324 (2023).

Qin, C., Chen, Z., Cao, R., Shi, M. & Tian, Y. Integrated analysis of the fecal metagenome and metabolome in bladder cancer in a Chinese population. Genes 13, 1967 (2022).

Mingdong, W., Xiang, G., Yongjun, Q., Mingshuai, W. & Hao, P. Causal associations between gut microbiota and urological tumors: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Cancer 23, 854 (2023).

Yin, Z. et al. A large genetic causal analysis of the gut microbiota and urological cancers: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients 15, 4086 (2023).

Graziani, C. et al. Intestinal permeability and dysbiosis in female patients with recurrent cystitis: A pilot study. J. Pers. Med. 12, 1005 (2022).

Okamoto, T. et al. Altered gut microbiome associated with overactive bladder and daily urinary urgency. World J. Urol. 39, 847–853 (2021).

Foxman, B. Urinary tract infection syndromes: Occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 28, 1–13 (2014).

Worby, C. J. et al. Longitudinal multi-omics analyses link gut microbiome dysbiosis with recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 630–639 (2022).

Lee, J. R. et al. Gut microbial community structure and complications after kidney transplantation: A pilot study. Transplantation 98, 697–705 (2014).

Magruder, M. et al. Gut uropathogen abundance is a risk factor for development of bacteriuria and urinary tract infection. Nat. Commun. 10, 5521 (2019).

Tariq, R. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent clostridium difficile infection reduces recurrent urinary tract infection frequency. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, 1745–1747 (2017).

Peterson, L. W. & Artis, D. Intestinal epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 141–153 (2014).

Cani, P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481 (2008).

Han, Y. Z. et al. Role of gut microbiota, immune imbalance, and allostatic load in the occurrence and development of diabetic kidney disease. J. Diabetes. Res. 2023, 8871677 (2023).

Fang, Q. et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates renal inflammation and fibrosis in rats with diabetic kidney disease. Front. Physiol. 12, 682482 (2021).

Tang, B. et al. Gut microbiota alters host bile acid metabolism to contribute to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 14, 1305 (2023).

Song, Q. et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-generated acetate suppresses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 79, 1352–1365 (2023).

Shin, A. et al. Microbiota-Short Chain Fatty Acid Relationships and Microbial Substrate Preferences Vary Across the Spectrum of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). medRxiv 2024.01.31.24302084 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.31.24302084.

Liu, G. et al. Dietary nucleotides influences intestinal barrier function, immune responses and microbiota in 3-day-old weaned piglets. Int. Immunopharmacol. 117, 109888 (2023).

Breyner, N. M. et al. Oral delivery of pancreatitis-associated protein by Lactococcus lactis displays protective effects in dinitro-benzenesulfonic-acid-induced colitis model and is able to modulate the composition of the microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 4020–4031 (2019).

Liu, B. et al. Butyrate protects rat liver against total hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury with bowel congestion. PLoS ONE 9, e106184 (2014).

Morrison, D. J. & Preston, T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 7, 189–200 (2016).

Wang, Y.-C. et al. Supplementation of probiotic Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum mediates anticancer effect on bladder urothelial cells by regulating butyrate-responsive molecular signatures. Diagnostics 11, 2270 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Novel phocaeicola strain ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Curr. Microbiol. 79, 393 (2022).

Hu, X. et al. GlcNac produced by the gut microbiome enhances host influenza resistance by modulating NK cells. Gut Microbes 15, 2271620 (2023).

Liao, W. et al. Bifidobacterium animalis: the missing link for the cancer-preventive effect of Gynostemma pentaphyllum. Gut Microbes 13, 1847629 (2021).

Flint, H. J., Duncan, S. H. & Louis, P. The impact of nutrition on intestinal bacterial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 38, 59–65 (2017).

Fassarella, M. et al. Gut microbiome stability and resilience: elucidating the response to perturbations in order to modulate gut health. Gut 70, 595–605 (2021).

Lin, M. Y., de Zoete, M. R., van Putten, J. P. M. & Strijbis, K. Redirection of epithelial immune responses by short-chain fatty acids through inhibition of histone deacetylases. Front. Immunol. 6, 554 (2015).

Haghikia, A. et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity 43, 817–829 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Inulin alleviates inflammation of alcoholic liver disease via SCFAs-inducing suppression of M1 and facilitation of M2 macrophages in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 78, 106062 (2020).

Li, S. et al. Sedanolide alleviates DSS-induced colitis by modulating the intestinal FXR-SMPD3 pathway in mice. J. Adv. Res. S2090–1232(24), 00128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.03.026 (2024).

Ge, X., Huang, S., Ren, C. & Zhao, L. Taurocholic acid and glycocholic acid inhibit inflammation and activate Farnesoid x receptor expression in LPS-stimulated Zebrafish and macrophages. Molecules 28, 2005 (2023).

Wu, R., Kumawat, A. K. & Demirel, I. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) mediates increased inflammation and colonization of bladder epithelial cells during a uropathogenic E. coli infection in vitro. Pathogens 12, 523 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University for their support of the present study, and Home for Researchers editorial team (www.home-for-researchers.com) for language editing service.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81860142).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shaohua Chen conceived and designed the study and critically revised the manuscript. Hua Mi provided funds. Jinji Chen and Shengsheng Liang provided technical support. Cheng Li and Chenglong Fan conducted the experiments. Cheng Li and Peng Jiang wrote the article. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Jiang, P., Fan, C. et al. Characteristics of gut microbiota and metabolites in rats with ketamine-induced cystitis. Sci Rep 16, 1801 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31280-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31280-y