Abstract

Accurate biological dose assessment is critical in radiation emergencies, particularly in cases of low-dose exposure. The dicentric chromosome assay (DCA) is the gold standard for biodosimetry, but conventional Giemsa staining often presents challenges in identifying centromeres, especially in morphologically distorted metaphase cells. In this study, we constructed dose-response calibration curves using both Giemsa and centromere-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) staining across two dose ranges (0–5 and 0–1 Gy) according to ISO 19238:2023 guidelines. The centromere-FISH-based curves demonstrated improved statistical validity, satisfying Poisson distribution requirements across all dose points and achieving lower minimum detectable doses of 47–94 mGy, compared to 87–127 mGy obtained with Giemsa staining. Furthermore, dose estimation of blinded samples showed higher accuracy and reliability using centromere-FISH-based curves, particularly at low-dose levels (0.05–0.2 Gy). These findings suggest that centromere-FISH staining enhances the sensitivity and accuracy of DCA, supporting its application as an effective method for biodosimetry following low-dose radiation exposure. Furthermore, we propose applying the 0–1 Gy or 0–5 Gy calibration curve to improve the estimation accuracy for low-dose exposure and enable flexible application in radiation exposure incidents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radiation exposure incidents can occur in various settings, including nuclear power plants, medical radiotherapy facilities, industrial radiography units, and research laboratories. These events may result from natural disasters, equipment malfunctions, human error, or intentional acts such as terrorism1,2. Depending on the radiation dose, exposed individuals may experience a wide range of health effects. High-dose exposure can cause acute symptoms such as skin burns, nausea, fatigue, and, in severe cases, death3,4. In contrast, low-dose exposure may not produce immediate symptoms but is associated with an increased long-term risk of cancer, leukemia, and cardiovascular diseases5,6,7. Rapid and accurate dose assessment is essential for effective medical response and triage following radiation incidents. This can be achieved using physical dosimeters and biological dosimetry, both of which are critical for evaluating health risks and guiding treatment. Furthermore, long-term health monitoring and follow-up care are necessary to manage the potential delayed effects of radiation exposure8,9,10. Notably, most radiation incidents involve low-dose exposures of less than 1 Gy7,10,11,12, highlighting the importance of accurate low-dose assessments for long-term risk evaluation and clinical management.

Biological dosimetry accounts for individual variability in radiation sensitivity, allowing personalized assessment and management following exposure12,13,14. This personalized approach supports tailored healthcare decisions and long-term monitoring strategies12,15. Among the various biological dosimetry techniques developed for the rapid assessment of both low- and high-dose exposures, the dicentric chromosome assay (DCA) remains the most reliable and internationally standardized method12,16. DCA is widely used for estimating doses ranging from 0.1 to 5 Gy after acute radiation exposure12,16, although emerging studies have reported its applicability in detecting dicentric chromosomes even after chronic or low-dose exposure17. For example, Abe et al. reported that in individuals exposed to low-dose radiation (0.01–0.1 Gy), the frequency of dicentric chromosomes ranged from 0.001 to 0.002 with Giemsa staining and 0.001–0.003 with centromere-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) staining but did not show a clear dose-dependent increase within this range. This suggests that the sensitivity of current detection methods remains limited for very low-dose exposures17. Consequently, there is a critical need to improve dose–response curve (DRC) accuracy to reliably assess low-dose radiation exposure below 0.1 Gy12,18,19.

A dicentric chromosome, characterized by the presence of two centromeres, is an unstable aberration that serves as a key biomarker of radiation exposure20,21,22. Accurate identification of dicentric chromosomes in metaphase cells is essential for reliable dose estimation in biological dosimetry. Giemsa staining is widely employed in DCA due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness; however, its diagnostic utility may be limited under suboptimal sample conditions, where chromosome morphology can be ambiguous12,23. Common issues include excessively long or overlapping chromosomes, chromosomes with shapes resembling dicentric structures, and fragments that are difficult to distinguish from short chromosomes24,25. These ambiguities can hinder centromere recognition and increase the likelihood of misclassification, even among experienced scorers. The EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 guidelines recommend analyzing 1,000 metaphase cells or scoring until 100 dicentric chromosomes are identified for dose estimation12,22. However, ISO 19238:2023 guidelines recommend evaluating 3,000–5,000 metaphase cells for exposures ≤ 1 Gy and retaining the 100-dicentric cell criterion for higher doses24. This update underscores the need for greater statistical confidence at low doses. Furthermore, each metaphase cell must be verified to contain 46 centromere-positive chromosomes to ensure accurate analysis12,24. In low-dose exposure scenarios, errors in dicentric chromosome identification can lead to either underestimation or overestimation of the absorbed dose, highlighting the importance of precise interpretation. Recent advancements in FISH using centromere-specific probes have improved centromere visualization, enhancing the reliability of dicentric detection16,26,27. In samples exposed to low-dose radiation, a large number of metaphase cells must be analyzed, whereas high-dose radiation often results in poorly preserved chromosomal morphology. Therefore, the application of FISH staining in DRCs construction may improve the accuracy and sensitivity of low-dose radiation exposure assessments.

The Dong Nam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (DIRAMS) has implemented a biodosimetry system to evaluate radiation exposure among populations residing near nuclear power plants20. Previous efforts have focused on establishing DRCs using DCA with Giemsa staining and translocation analysis via FISH staining20. Building upon these foundations, the present study aimed to enhance the accuracy of dose estimation, particularly in the low-dose range, by optimizing DRCs through DCA with centromere-FISH staining. Given the growing concerns regarding low-dose radiation exposure in communities near nuclear facilities, this approach may provide a more sensitive and reliable risk assessment method.

Results

Improvement of unstable chromosome analysis using centromere-FISH staining

Giemsa staining is widely used to detect unstable chromosomal aberrations, including dicentric chromosomes, rings, and fragments, owing to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. We confirmed that, in well-spread metaphase cells, the clear visualization of centromeres allows the accurate identification of dicentric chromosomes (Fig. 1A). However, achieving uniformly well-spread and morphologically intact metaphases remains challenging, and some cells must be excluded from analysis. When chromosomes are overly short, elongated, or overlapping, even experienced cytogeneticists may struggle to distinguish individual centromeres, complicating the classification of normal and abnormal chromosomes (Fig. 1B). To address these limitations, FISH with centromere-specific probes was applied to enhance centromere visibility. DAPI (blue) staining visualized all chromosomes, while centromere-FISH signals provided clearer centromere identification. As shown in Fig. 2A, FISH improved classification accuracy in well-preserved chromosomes and enabled the reliable detection of dicentrics, fragments, and rings, even in morphologically ambiguous metaphases (Fig. 2B).

Radiation-induced chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes visualized by Giemsa staining. (A) Normal chromosomes (yellow circle) and radiation-induced abnormal chromosomes—dicentric chromosomes (red circle), ring chromosomes (blue circle), and fragments (green circle)—in well-spread metaphase cells, and (B) poorly spread metaphase cells (red circle).

Radiation-induced chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes visualized by centromere fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) staining. (A) Radiation-induced abnormal chromosomes, dicentric chromosomes (green circles) and ring chromosomes (red circles), in well-spread metaphase cells. (B) Poorly spread metaphase cells (yellow circles).

To quantitatively assess the effectiveness of centromere-FISH staining in metaphase cell selection, 10,000 DAPI-stained metaphase images were randomly selected and independently evaluated by two cytogenetic experts under two conditions: with and without centromere signals (Fig. 3). No significant interobserver variation in the number of rejected cells across the staining conditions was observed (Fig. 3A and B). However, an analysis of the averaged data revealed a marked difference in classification accuracy: centromere-stained images yielded only 152 ambiguous cases (1.52%) that were rejected, whereas DAPI images without centromere staining resulted in 611 rejected cells (6.11%) (Fig. 3C and D). Thus, centromere-FISH reduced the rejection rate of metaphase images by approximately four times. These findings demonstrate that centromere-FISH staining facilitates faster and more accurate identification of metaphase cells with all 46 centromeres, thereby improving the efficiency of dicentric chromosome analysis. Additionally, an increased number of acceptable metaphase cells per slide may reduce the number of slides required per sample, further optimizing the laboratory workflow.

Evaluation of metaphase cell selection efficiency with and without centromere staining by two independent scorers. (A) Inter-scorer variation in identifying metaphase cells from centromere-stained images. (B) Inter-scorer variation in identifying metaphase cells from unstained images. Statistical significance assessed by Z-score. (C) Comparison of the average (%) of rejected cells between centromere-stained and unstained metaphase cells across the three scorers. (D) Representative images of metaphase cells with and without centromere probe staining.

Enhanced detection of radiation-induced unstable chromosomes with increasing dose using centromere-FISH staining

To evaluate the effectiveness of centromere-FISH staining in detecting radiation-induced unstable chromosomal aberrations, we compared the frequencies of dicentric chromosomes, rings, and fragments identified using either conventional Giemsa staining or centromere-FISH staining at various radiation doses. As shown in Fig. 4, centromere-FISH staining yielded consistently higher frequencies of detected unstable chromosomes than Giemsa staining. This was evident in dicentric chromosomes (Fig. 4A), rings (Fig. 4B), and fragments (Fig. 4C), particularly at higher radiation doses. Statistically significant differences were observed in the frequencies of dicentric chromosomes at 3 Gy and 4 Gy (p < 0.05), and for fragments at 0.8 Gy and 3 Gy (p < 0.05). Although the difference in detection was not statistically significant at most lower dose levels, centromere-FISH staining still showed higher mean frequencies, even at doses of 0.2 Gy or below (Fig. 4D). Individual analyses of each donor (S-1 and S-2) showed comparable trends, supporting the overall findings (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results indicate that centromere-FISH staining improves the sensitivity of unstable chromosome detection, particularly at moderate-to-high radiation doses. Moreover, it enhances the consistency and accuracy of dicentric chromosome identification, even at low doses, which is critical for the reliable construction of DRCs in biological dosimetry.

Comparison of unstable chromosome aberration frequencies between Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining in lymphocytes exposed to 0–5 Gy of radiation from two healthy donors. (A) Frequency of dicentric chromosomes in pooled data from two donors analyzed using Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining. (B) Frequency of ring chromosomes in pooled data from two donors. (C) Frequency of fragments in pooled data from two donors. (D) Comparison of dicentric chromosome frequency between Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining in the low-dose range (0–0.2 Gy) for the pooled data.

Optimization of the DRCs using dicentric chromosome analysis based on centromere-FISH staining in the 0–5 Gy range

To evaluate the utility of centromere-FISH staining in optimizing DRCs, we applied two analytical criteria: EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 and ISO 19238:202312,24. According to these guidelines, 1,000 or 3,000 metaphase cells were analyzed for doses ≤ 1 Gy, and 100 dicentric chromosomes were scored for doses > 1 Gy. Additionally, the ISO 19238:2023 recommends constructing DRCs from pooled data of at least two healthy donors with a minimum of five dose points below 1 Gy, including 0 Gy.

In this study, irradiated blood samples from two healthy individuals were prepared with a dose range of 0 to 5 Gy, and DRCs were generated through dicentric chromosome analysis at 12 dose points, including eight doses below 1 Gy. Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining were independently applied to the same samples. As presented in Supplementary Table S1, dicentric chromosome frequency and distribution were assessed using metaphase cell counts from both individuals, with 1,000 or 3,000 cells for doses below 1 Gy under both staining conditions. At 0 Gy, no significant differences in background dicentric chromosome frequency (0.000 ~ 0.001) were observed between the two donors under either Giemsa or centromere-FISH staining, indicating comparable baseline chromosomal stability (data not shown).The frequency differences between the 1,000- and 3,000-cell analyses were minimal for both Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining. Furthermore, centromere-FISH staining consistently exhibited slightly higher dicentric chromosome frequencies across all dose levels than Giemsa staining. The Poisson distribution was confirmed for each dose condition, with all u-values falling within the acceptable range of −1.96 to 1.96 (Supplementary Table S1).

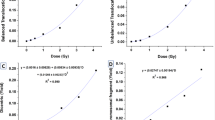

DRCs were generated using the linear-quadratic model (Y = C + αD + βD²). Although both staining methods showed similar curve shapes under the 1,000- and 3,000-cell conditions, centromere-FISH staining produced a noticeably steeper slope at higher doses owing to an elevated β-coefficient (Fig. 5A; Table 1). According to ISO 19238:2023, the minimum detectable dose (MDD)—defined as the lowest radiation dose that can be reliably distinguished from background—was calculated using Dose Estimate version 5.2 based on the observed dicentric chromosome yields, following the method of Lloyd et al.28. Centromere-FISH-based DRCs yielded lower MDDs (72 mGy [95% CI, 1–192 mGy] and 90 mGy [95% CI, 7–214 mGy]) than Giemsa-based curves (89 mGy [95% CI, 5–234 mGy] and 121 mGy [95% CI, 16–271 mGy]). Although partial overlap was observed between the 95% upper and lower confidence limits of the two methods, the consistently lower MDDs and narrower intervals for the centromere-FISH curves indicate meaningful improvements in detection sensitivity and precision in the low-dose range. These results confirm that centromere-FISH-based DRCs not only satisfy ISO 19238:2023 requirements but also enhance the quantitative accuracy of dose estimation, particularly below 100 mGy.

Dose–response curves for dicentric chromosomes analyzed using Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining in human lymphocytes from two healthy donors. (A) Dose–response curves for dicentric chromosome frequency obtained from 0–5 Gy-irradiated samples. G2-DRC-1 and F2-DRC-1 represent curves generated from 1,000 metaphase cells analyzed using Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining, respectively; G2-DRC-2 and F2-DRC-2 represent curves generated from 3,000 metaphase cells. (B) Dose–response curves for dicentric chromosome frequency in the low-dose range (0–1 Gy). G2-DRC-1-L and F2-DRC-1-L indicate 1,000 metaphase cell analyses using Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining, respectively; G2-DRC-2-L and F2-DRC-2-L indicate 3,000 metaphase cell analyses.

Optimization of the DRCs using dicentric chromosome analysis based on centromere-FISH staining in the 0–1 Gy range

To further enhance sensitivity in low-dose radiation assessment, we constructed DRCs using eight calibration points within the 0–1 Gy range for both Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining methods. These DRCs were compared with those previously established using 12 calibration points of 0–5 Gy, focusing on differences in the MDD and their 95% confidence limits. As shown in Fig. 5B; Table 2, slope patterns of 0–1 Gy DRCs closely mirrored those observed in the broader 0–5 Gy analysis for both staining protocols. For Giemsa staining, the MDD for G2-DRC-1-L was 87 mGy (95% CI, 3–233 mGy), which was a slight reduction from the 89 mGy (95% CI, 5–234 mGy) obtained in the 0–5 Gy curve. Under the 3,000-cell condition, the MDD for G2-DRC-2-L was 85 mGy (95% CI, 3–226 mGy), which was substantially lower than the 121 mGy (95% CI, 16–271 mGy) in the 0–5 Gy range (Tables 1 and 2). Centromere-FISH staining demonstrated even greater improvement in detection sensitivity. MDDs for F2-DRC-1-L and F2-DRC-2-L were 47 mGy (95% CI, 4–142 mGy) and 52 mGy (95% CI, 3–157 mGy), markedly lower than those for F2-DRC-1 (72 mGy [95% CI, 1–192 mGy]) and F2-DRC-2 (90 mGy [95% CI, 7–214 mGy]) in the full-dose range. There was partial overlap between the 95% upper and lower confidence limits of the two methods; however, the consistently lower MDD values and narrower confidence intervals exhibited by centromere-FISH indicated improved statistical precision and sensitivity in the low-dose region. Collectively, these results indicate that optimizing DRC construction within the 0–1 Gy range enhances the detection limit and quantitative accuracy of centromere-FISH staining compared with Giemsa, thereby improving its suitability for low-dose biodosimetry.

Validation of the DRCs through estimated dose assessment of blinded samples

To validate the reliability of the established DRCs, we assessed the estimated radiation doses of five blinded samples irradiated at known doses (0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 Gy). Dose estimations were performed using Dose Estimate version 5.2, applying DRC equations derived from both Giemsa staining (G2-DRC-1, G2-DRC-2, G2-DRC-1-L, and G2-DRC-2-L) and centromere-FISH staining (F2-DRC-1, F2-DRC-2, F2-DRC-1-L, and F2-DRC-2-L). The accuracy of each estimation was determined by whether the estimated dose fell within the 95% confidence interval (CI) relative to the actual known dose. If the 95% lower confidence limit was negative, it was considered zero (Supplementary Table S3).

For the Giemsa-based 0–5 Gy curves (G2-DRC-1 and G2-DRC-2), the estimated dose for the 0.05 Gy sample was a negative value, corresponding to the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval, indicating an inaccurate dose estimation for this sample. Contrastingly, the remaining blinded samples (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 Gy) were all estimated within the acceptable confidence interval. Notably, the centromere-FISH-based 0–5 Gy curves (F2-DRC-1 and F2-DRC-2) successfully estimated all five blinded samples within the 95% CI range (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 6). A similar trend was observed in the low-dose (0–1 Gy) DRC validation. Giemsa-based curves (G2-DRC-1-L and G2-DRC-2-L) failed to accurately estimate the 0.05 Gy sample, whereas the other four samples were within range. However, centromere-FISH-based low-dose curves (F2-DRC-1-L and F2-DRC-2-L) correctly estimated all five blinded doses within the 95% CI (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 6). We quantitatively compared optimized (centromere-FISH–based) and conventional (Giemsa-based) dose–response curves using blinded samples < 0.5 Gy. As shown in Supplementary Table S4, centromere-FISH–based curves in the 0–1 Gy range (F2-DRC-1-L and F2-DRC-2-L) yielded the smallest differences between actual and estimated doses. To further assess statistical performance at low doses, odds ratios (ORs, zero dose: suspected dose) were calculated as recommended in the EPR-Biodosimetry guideline. At 0.05 Gy and at 0.1 Gy, centromere-FISH showed higher OR values (7.0–11.6 and 219.5–513.8, respectively) than Giemsa (1.3–3.5 and 135.9–314.4, respectively), indicating enhanced discriminative ability between background and exposed samples (Supplementary Table S3). Collectively, these results indicate that, compared with conventional Giemsa staining, the centromere-FISH approach provides improved sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy for low-dose radiation biodosimetry.

Discussion

Biological dosimetry using DCA depends heavily on the precise identification of dicentric chromosomes from a minimum of 1,000 metaphase cells per blinded sample, which requires clear visualization of centromeres to ensure reliable scoring12. Although Giemsa staining remains widely used owing to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness12,29, achieving consistent chromosome morphology across samples remains a persistent challenge. In both our previous20 and present studies, we observed that Giemsa-stained metaphase images, despite being analyzed by two cytogenetic experts with over five years of DCA experience, often exhibited morphological distortions such as elongated, contracted, or overlapping chromosomes. These issues, particularly evident in high-dose samples (≥ 2 Gy), frequently impaired the discrimination of normal versus dicentric chromosomes and led to the exclusion of a substantial number of metaphase cells. Given that biodosimetry guidelines recommend scoring either 1,000 metaphase cells or 100 dicentric chromosomes per sample12,24, there is a pressing need for methods that enhance centromere distinction to minimize cell rejection and improve scoring accuracy and efficiency. FISH, a molecular cytogenetic technique that utilizes fluorescent probes to detect specific DNA sequences on chromosomes30,31, offers a solution to this limitation. In particular, centromere-specific probes enhance chromosome identification by targeting repetitive DNA regions at the centromere, aiding in the detection of structural rearrangements and aneuploidy32. In biodosimetry, centromere-FISH staining significantly improves the visualization and identification of unstable chromosomal aberrations, including dicentric chromosomes, rings, and fragments, thereby offering a more accurate and efficient alternative to conventional Giemsa staining33. Our findings support the adoption of centromere-FISH staining as a refined methodological approach that enhances centromere clarity and strengthens the overall reliability of biological dose assessment, particularly under challenging imaging conditions or at high radiation doses.

Low-dose radiation exposure, commonly encountered in occupational environments or through medical procedures such as diagnostic X-rays and computed tomography scans, is associated with increased risks of cancer, leukemia, and cardiovascular diseases34,35,36. Therefore, an accurate assessment of such exposures is essential for both public health protection and individual medical management. In biological dosimetry, the detection limit is defined as the minimum dose of radiation that can be reliably distinguished from the background with statistical confidence. According to international standards, such as EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 and ISO 19238:2023, the recommended detection limit for DCA is approximately 0.1 Gy12,24. However, recent ex vivo studies using cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes have shown a dose-dependent increase in chromosomal aberrations at much lower doses, even as low as 0.01–0.02 Gy17. The Abe group established DRCs in the 0–1 Gy range, reporting a relatively consistent background frequency of 0.001 and noting that centromere-FISH staining slightly improved detection sensitivity over conventional Giemsa staining in the low-dose range. Specifically, their findings indicated a dicentric chromosome frequency of 0.002–0.006 with centromere-FISH, compared to 0.002–0.004 with Giemsa in the low dose range of 0.05–0.2 Gy17. In this study, we aimed to illustrate the novelty of our approach compared with previous research on dicentric chromosome analysis using FISH. Unlike Shi et al.37, who primarily emphasized advantages of centromere-FISH for high-dose analysis, our research focused on demonstrating the quantitative applicability and statistical robustness of centromere-FISH in the low-dose region (≤ 1 Gy). Furthermore, Abe et al.17 reported limited accuracy of FISH at low doses and its difficulty for large-scale application; our study addressed these issues by establishing optimized low-dose (0–1 Gy) dose–response curves and conducting quantitative validation using blinded samples < 0.1 Gy (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). By evaluating the MDDs, estimation accuracy, and ORs as statistical measures of sensitivity and specificity in accordance with ISO 19238:2023, we confirmed that centromere-FISH–based biodosimetry reduces statistical uncertainty and improves discrimination between background and low-dose exposures. These findings demonstrate the enhanced detection sensitivity, reproducibility, and statistical reliability of centromere-FISH–based calibration in the sub-0.1 Gy range, supporting its potential as a standardized and practical approach for low-dose radiation assessment.

Establishing laboratory-specific DRCs is a critical requirement for accurate biodosimetry using DCA, as emphasized in several international guidelines10,12,17,20,22,36,38,39. The EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 guideline12,22 previously recommended scoring 1,000 metaphase cells at doses below 1 Gy. However, recognizing the need for improved statistical uncertainty, ISO 19238:202324 recommends scoring a minimum of 3,000 metaphase cells per dose point, including at least two healthy donors, and using at least five dose points below 1 Gy. In dose–response curve construction using DCA, it is essential to confirm that the distribution of dicentric chromosomes at each dose level follows a Poisson distribution, as indicated by a u-value within the range of − 1.96 < u < 1.96. This statistical criterion ensures that the observed variance is consistent with the expected random distribution of dicentric chromosomes. If a particular dose point fails to meet this criterion (i.e., the u-value falls outside the acceptable range), it suggests that the data at that dose may exhibit overdispersion or underdispersion, indicating a potential deviation from the assumed biological randomness. Such deviations can compromise the statistical reliability of the dose–response curve, potentially affecting the accuracy of dose estimation12,24. In our previous study, pooled data from five healthy donors stained with Giemsa across the 0–5 Gy range failed to meet Poisson distribution criteria at 0.5 and 5 Gy (u < − 1.96), indicating limitations in dose estimation reliability at these points20. In the present study, we constructed DRCs from 12 irradiated blood samples (0–5 Gy) obtained from two healthy donors using both Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining. In accordance with the ISO 19238:2023 recommendations, eight dose points below 1 Gy were included, and each sample was analyzed using 1,000 and 3,000 metaphase cells per dose. All resulting DRCs, regardless of the staining method or the number of cells analyzed, satisfied the Poisson distribution criteria across all dose levels. Notably, in the low-dose range, where the frequency of dicentric chromosomes is low, the measurement uncertainty tends to increase owing to statistical variability. To address this, analyzing a larger number of metaphase cells, such as the 3,000-cell criterion recommended by the ISO 19238:2023 standard, is crucial for improving the reliability of dose estimation. In our findings, the standard errors (SE) of dicentric chromosome frequencies between 0.1 and 1 Gy were slightly lower when based on 3,000 metaphase cells compared to 1,000 cells. These findings support the updated ISO guidelines and highlight the critical role of increasing the analyzed cell counts in enhancing the precision and confidence of dose estimation, particularly in the low-dose range, where accurate biological dose assessment is essential. According to IAEA and ISO 19238:2023 guidelines, blood samples from at least three donors are recommended to minimize inter-individual variability when constructing dose–response curves. In this study, calibration curves were generated using blood samples from two healthy donors that satisfied all experimental and quality control requirements. We suggest that this study primarily aimed to compare Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining using identical donor samples to demonstrate the methodological feasibility and analytical efficiency of the FISH approach. Future research should expand the number of donors to develop multi-donor calibration curves, thereby optimizing the centromere-FISH–based dose–response model and strengthening its applicability in biodosimetry.

The calibration curve is a fundamental component of DCA in biological dosimetry, as it enables the estimation of radiation dose in exposed samples, with the MDD representing the lowest radiation dose that can be reliably quantified12,24. Although the EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 guideline specified a standardized detection limit of 0.1 Gy, ISO 19238:2023 guideline recommends that laboratories determine their own MDD based on internally established calibration curves12,24. To improve sensitivity in low-dose radiation assessment, we evaluated the MDD using various DRCs derived from both Giemsa and centromere-FISH staining, applying 1,000 and 3,000 metaphase cells per dose point and performing analyses using the Dose Estimation 5.2 software. Among the DRCs generated across the 0–5 Gy range, those based on centromere-FISH staining (F2-DRC-1 and F2-DRC-2) showed consistently lower MDD than those based on Giemsa staining (G2-DRC-1 and G2-DRC-2). This trend remained consistent within the 0–1 Gy low-dose range. Using the Dose Estimate Software version 5.240, we calculated the MDD based on the 0–1 Gy dose–response curves proposed by the Abe group. The MDD for Giemsa staining was 253 mGy, whereas that for centromere-FISH staining was significantly lower at 131 mGy, indicating the superior sensitivity of the centromere-FISH method. Similarly, in our study, the centromere-FISH-based curves optimized for the 0–1 Gy range (F2-DRC-1-L and F2-DRC-2-L) achieved even lower MDDs of 47 mGy and 53 mGy, respectively, further highlighting their enhanced sensitivity and reliability for low-dose radiation biodosimetry.

Accurate dose estimation is a cornerstone of biological dosimetry, as both overestimation and underestimation can lead to significant misinterpretation of an individual’s radiation exposure. To ensure reliable results, dose assessments must be conducted within the MDD range established using the laboratory’s calibration curve, and the uncertainty associated with these estimates should be clearly presented using 95% CIs. This is especially critical for low-dose exposure, where estimated values may approach the lower boundary of detection, making the 95% lower limit a key factor in interpretative accuracy12,24. In this study, we validated the performance of our calibration curves by estimating the radiation doses for blinded samples (0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 Gy) and by assessing whether the results fell within the 95% CI of each curve. When using the 0–5 Gy calibration curves, the Giemsa-based curves (G2-DRC-1 and G2-DRC-2) failed to estimate the 0.05 Gy sample within the 95% CI, whereas the centromere-FISH-based curves (F2-DRC-1 and F2-DRC-2) successfully captured all blinded doses, including 0.05 Gy, within their respective 95% CIs. To further evaluate the estimation accuracy in the low-dose region, we applied calibration curves restricted to the 0–1 Gy range. The centromere-FISH-based curves (F2-DRC-1-L and F2-DRC-2-L) again provided reliable estimations for all blinded doses, including 0.05 Gy, unlike the Giemsa-based low-dose curves (G2-DRC-1-L and G2-DRC-2-L). In addition, by quantitatively comparing differences between the actual and estimated doses for blinded samples < 0.5 Gy, we found that the centromere-FISH–based calibration curves exhibited the smallest estimation errors within the 0–1 Gy range, demonstrating superior accuracy compared with the Giemsa-based curves. These improvements resulted from enhanced curve fitting, which is reflected by lower residual variance, smaller standard errors of α and β, and narrower 95% confidence intervals. Sensitivity and specificity were further evaluated using ORs, which assess the likelihood that dicentric chromosome frequencies result from radiation rather than from background variation. According to the EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 guideline12, OR analysis provides a useful measure of low-dose discrimination. At 0.05 and 0.1 Gy, centromere-FISH-based curves yielded moderately higher ORs than Giemsa-based curves, indicating improved low-dose detection. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the optimized centromere-FISH calibration provides more accurate, sensitive, and statistically reliable dose estimation in the low-dose region, indicating its potential as an approach to improve the precision of biological dosimetry.

Centromere-FISH staining offers clear advantages in accuracy and sensitivity; however, several practical limitations should be acknowledged, including higher reagent costs, specialized expertise, and longer turnaround time compared with Giemsa staining. These challenges can be mitigated through the use of automated systems and parallel hybridization—where multiple slides are hybridized simultaneously under identical conditions—a technical approach that enhances time efficiency and experimental consistency by enabling high-throughput processing while maintaining uniformity across samples. Additionally, a tiered Giemsa–FISH workflow can balance speed and accuracy for large-scale biodosimetry. This two-step Giemsa–centromere-FISH strategy maintains high analytical throughput and reliable centromere identification, enhancing scalability for emergency or large-scale biodosimetry. Because this study represents a methodological validation under controlled conditions, future work should focus on cost–benefit evaluation and workflow optimization to assess the practicality of centromere-FISH for routine biodosimetry operations and large-scale radiation response scenarios.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that constructing calibration curves using centromere-FISH staining, following ISO 19238:2023 guidelines, improves the statistical reliability and sensitivity of dicentric chromosome analysis, especially for low-dose exposure. This study also suggests that while the 0–5 Gy dose-response curve is commonly used for dose estimation in radiation-exposed samples, selecting a more flexible option, such as the 0–1 Gy curve, may be more appropriate in cases of low estimated doses. Nevertheless, this study should be regarded as a proof-of-concept validation conducted under controlled laboratory conditions rather than the establishment of a method ready for operational deployment. To strengthen reproducibility and broader applicability, future research will involve inter-laboratory validation and expanded sample cohorts across diverse populations. These collaborative efforts will be essential to establish the centromere-FISH approach as a standardized tool for both routine and emergency biodosimetry.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Dongnam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (DIRAMS) for all experimental procedures (approval no. D-1602-002-001). Prior to inclusion in the study, informed consent was obtained from all participants under the supervision of the IRB of the DIRAMS via signing of a consent form containing the necessary details about the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Sample preparation

Blood samples were collected from two healthy donors (two males aged 32–38 years) to establish DRCs for dicentric chromosome analysis. Additionally, blinded samples were obtained from four healthy donors (four males aged 29–61 years). All donors were healthy, had no history of radiation exposure within the previous 3 months, and had no known prior exposure to clastogenic agents such as chemotherapy or environmental mutagens. Irradiation was performed using a calibrated ⁶⁰Co gamma irradiator (Gamma Beam X-200, Best Theratronics Ltd., Canada) located at DIRAMS. The irradiator was dosimetrically verified prior to use with a Farmer-type ionization chamber (TM30013, PTW, Germany) traceable to national standards through a KOLAS-accredited laboratory. The dose rate at the irradiation position was 0.7965 ± 0.0035 Gy/min with a 10 cm × 10 cm field at a source-to-surface distance (SSD) of 100 cm and a depth of 5 cm in a water phantom maintained at 37 °C. Whole-blood samples (5 mL each) were placed in 15-mL polypropylene conical tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and submerged in the water phantom covered with tissue-equivalent poly (methyl methacrylate). The phantom was gently rotated during exposure to ensure dose uniformity and prevent blood sedimentation. Irradiation doses of 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 Gy were delivered at an effective dose rate of approximately 0.1 Gy/min. Blinded samples were irradiated under identical conditions at 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 Gy. Following irradiation, blood samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h before lymphocyte culture. Each tube received 10.5 mL of culture medium (RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS and 1% antibiotics) and 2% phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 24 h, treated with Colcemid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for an additional 24 h, and harvested after hypotonic treatment (0.075 M KCl, 37 °C, 15 min). Cells were fixed in freshly prepared methanol: acetic acid (3:1) and stored for slide preparation.

Staining

We prepared metaphase slides using a HANABI-PVI Metaphase Spreader (ADS BioTec, Chiba, Japan) from the fixed cell suspension for two different staining methods. For Giemsa staining, slides were immersed in a 5% Giemsa solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 min, washed with distilled water, and air-dried. For centromere-FISH staining, 10 µL of a centromere probe mixture was added to each prepared slide according to the manufacturers’ protocols, which was then covered with a glass coverslip. The mixture consisted of equal volumes of an All Human Centromere (AHC, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) probe and an XCP pan-centromere probe (MetaSystems, Altlussheim, Germany), combined to ensure complete centromere labeling across all 46 chromosomes. Both probes were incubated at 75 °C for 5 min and immediately cooled on ice for 30 s. After sealing and drying the coverslip, the slide was incubated overnight (~ 18 h) at 37 °C in a ThermoBrite automatic slide hybridizer (TopBrite, Locarno, Switzerland). Following coverslip removal, the slide was sequentially washed with 0.4× SSC at 72 °C for 2 min and 2× SSC/0.05% Tween-20 at room temperature for 30 s. No additional blocking agents were required, because the commercial hybridization buffer contained DNA blockers to minimize non-specific binding. The slide was then briefly rinsed with distilled water to prevent crystal formation and air-dried at room temperature. Finally, slides were mounted using an antifade-mountant with DAPI (MetaSystems GmbH, Altlussheim, Germany). To validate the hybridization performance, each probe and the mixed-probe solution were tested separately. Two independent scorers analyzed 200 randomly selected metaphase images per condition to confirm complete centromere labeling across all 46 chromosomes. The mixed-probe condition achieved a mean hybridization efficiency of 98% with an error rate below 2%, while single-probe staining yielded approximately 80% efficiency (data not shown). Based on these results, the optimized dual-probe protocol was adopted for all donor and blinded sample analyses.

Scoring

The slides were captured in AutoCapt mode using an AXIO Imager Z2 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with CCD cameras and Metafer 4 software (MetaSystems GmbH, Altlussheim, Germany). Metaphase cells were scanned at a low magnification (10×). Images deemed appropriate for scoring were captured at high magnification (63×) and exported as JPG files for Giemsa staining or MCI files for centromere-FISH staining. For each dose per donor, 1000–3,000 metaphases were recorded for absorbed doses under 1 Gy, or metaphases containing more than 100 dicentrics for absorbed doses over 1 Gy, according to EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 and ISO 19238:202312,24. At 0 Gy, 5,000 metaphases per donor were examined to ensure statistical reliability. Additionally, 1,000 metaphases were analyzed for each blinded sample. All samples were independently evaluated by two experienced biodosimetrists to ensure scoring reliability through cross-verification20,40. Identical scoring and exclusion criteria were applied to Giemsa- and centromere-FISH–stained metaphases in accordance with ISO 19238:2023 and IAEA EPR-Biodosimetry 2011. Only metaphases in which all 46 centromeres were distinctly visible were included. In Giemsa-stained slides, complete chromosomes with visible centromeric constrictions were confirmed; in centromere-FISH images, discrete fluorescent centromeric signals were verified for all chromosomes. A dicentric chromosome was defined as one containing two distinct centromeres connected by continuous chromatin. Cells in which chromosomes overlapped, were poorly spread, or showed unclear centromere distinction were excluded from scoring to ensure accurate identification of dicentrics. Centromere-FISH was applied using the same scoring criteria as Giemsa staining and was employed solely to enhance centromere visualization without modifying the fundamental scoring principles. Other chromosomal aberrations, including fragments and rings, were also recorded Other chromosomal aberrations, including fragments and rings, were also recorded.

DRCs fitting and dose Estimation

DRCs were established using pooled peripheral blood lymphocyte samples collected from two healthy donors. Blood samples were irradiated with 60Co gamma rays at a dose rate of 0.1 Gy/min across a range of 0–5 Gy. Eight experimental DRCs were constructed under varying staining and analysis conditions as follows (dicentric chromosome frequencies are provided in Supplementary Table S1):

-

G2-DRC-1: Giemsa staining, 0–5 Gy, 1,000 metaphase cells per dose point (EPR-Biodosimetry 2011).

-

G2-DRC-2: Giemsa staining, 0–5 Gy, 3,000 metaphase cells per dose point (ISO 19238:2023).

-

F2-DRC-1: Centromere-FISH staining, 0–5 Gy, 1,000 metaphase cells per dose point (EPR-Biodosimetry 2011).

-

F2-DRC-2: Centromere-FISH staining, 0–5 Gy, 3,000 metaphase cells per dose point (ISO 19238:2023).

-

G2-DRC-1-L: Giemsa staining, 0–1 Gy, 1,000 metaphase cells per dose point (EPR-Biodosimetry 2011).

-

G2-DRC-2-L: Giemsa staining, 0–1 Gy, 3,000 metaphase cells per dose point (ISO 19238:2023).

-

F2-DRC-1-L: Centromere-FISH staining, 0–1 Gy, 1,000 metaphase cells per dose point (EPR-Biodosimetry 2011).

-

F2-DRC-2-L: Centromere-FISH staining, 0–1 Gy, 3,000 metaphase cells per dose (ISO 19238:2023).

All dicentric chromosome analyses were conducted on metaphase cells prepared according to the EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 or ISO 19238:2023. The frequency of chromosomal aberrations (Y) was fitted to the radiation dose (D) using a linear-quadratic model:

where C represents the background value, and α and β are coefficients describing the linear and quadratic contributions of radiation dose, respectively. Curve fitting and coefficient calculations were performed using the Dose Estimate Software version 5.241. The same software was used to estimate the radiation doses of the blinded samples based on each fitted curve. Comparative analyses of dose–response models and curve fitting were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2; R Core Team).

Statistical analysis

For each experimental point, the distribution of dicentric chromosomes among cells was evaluated for adherence to the Poisson model by analyzing the variance-to-mean ratio and performing the u-test. The dispersion index (σ²/y) and its u value were calculated for each radiation dose based on the equation outlined in EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 and the ISO 19238:202312,24. A dispersion index (σ2/y) close to 1 and u values within the ± 1.96 range were considered indicative of conformity to the Poisson distribution. The Poisson distribution test, dispersion index, and odds ratio (OR; zero dose: suspected dose) were computed using the Dose Estimate Software version 5.241. The dose–response relationship was fitted to the linear–quadratic model using the iteratively reweighted least squares method. The goodness of fit of the curve and the statistical significance of the fitted coefficients were assessed using chi-squared (χ²) and F-tests, respectively. Comparative statistical analyses, including Student’s t-test for inter-method comparison and Z-score evaluation for inter-scorer validation, were performed using SPSS software for Windows, Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. These combined statistical approaches, performed in accordance with ISO 19238:2023 and IAEA EPR-Biodosimetry 2011 guidelines, ensured the robust assessment of dose–response relationships and inter-method consistency in dicentric chromosome analysis.

Data availability

All relevant data supporting the principal findings of this study are accessible within the article and the Supplementary Information files or can be requested from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

DiCarlo, A. L. et al. Cellular therapies for treatment of radiation injury: report from a NIH/NIAID and IRSN workshop. Radiat. Res. 188, e54–e75 (2017).

Gale, R. P. Medical and policy considerations for nuclear and radiation accidents, incidents and terrorism. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 24, 496–501 (2017).

Aniebone, V. O. et al. Radiation exposure and health effects on the human body. JCPMS 6, 28–38 (2023).

Martinez-López, W. & Hande, M. P. Advanced Security and Safeguarding in the Nuclear Power Industry- Chap. 4: Health Effects of Exposure To Ionizing Radiation 81–97 (Acad., 2020).

Simon, S. L., Kendall, G. M., Bouffler, S. D. & Little, M. P. The evidence for excess risk of cancer and non-cancer disease at low doses and dose rates. Radiat. Res. 198, 615–624 (2022).

Gillies, M., Haylock, R., Hunter, N. & Zhang, W. Risk of leukemia associated with protracted low-dose radiation exposure: updated results from the National registry for radiation workers study. Radiat. Res. 192, 527–537 (2019).

Kreuzer, M. et al. Low-dose ionising radiation and cardiovascular diseases–Strategies for molecular epidemiological studies in Europe. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 764, 90–100 (2015).

Barquinero, J. F. et al. Lessons from past radiation accidents: critical review of methods addressed to individual dose assessment of potentially exposed people and integration with medical assessment. Environ. Int. 146, 106175 (2021).

Grace, M. B. et al. Rapid radiation dose assessment for radiological public health emergencies: roles of NIAID and BARDA. Health Phys. 98, 172–178 (2010).

Jeong, S. K. et al. Dicentric chromosome assay using a deep learning-based automated system. Sci. Rep. 12, 22097 (2022).

Hauptmann, M. et al. Epidemiological studies of low-dose ionizing radiation and cancer: summary bias assessment and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2020, 188–200 (2020).

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Cytogenetic Dosimetry: Applications in Preparedness for and Response to Radiation Emergencies. Vienna, (2011).

Liu, G. Revision of cytogenetic dosimetry in the IAEA manual 2011 based on data about radio-sensitivity and dose-rate findings contributing. FASEB J. 36, e22621 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Developing gender-specific gene expression biodosimetry using a panel of radiation-responsive genes for determining radiation dose in human peripheral blood. Radiat. Res. 192, 399–409 (2019).

Ainsbury, E. A. et al. The future of biological dosimetry in mass casualty radiation emergency response, personalized radiation risk Estimation and space radiation protection. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 98, 421–427 (2022).

Gnanasekaran, T. S. Cytogenetic biological dosimetry assays: recent developments and updates. Radiat. Oncol. J. 39, 159–166 (2021).

Abe, Y. et al. Dose-response curves for analyzing of dicentric chromosomes and chromosome translocations following doses of 1000 mGy or less, based on irradiated peripheral blood samples from five healthy individuals. J. Radiat. Res. 59, 35–42 (2018).

Oestreicher, U. et al. Automated scoring of dicentric chromosomes differentiates increased radiation sensitivity of young children after low dose CT exposure in vitro. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 94, 1017–1026 (2018).

Bauchinger, M. Quantification of low-level radiation exposure by conventional chromosome aberration analysis. Mutat. Res. 339, 177–189 (1995).

Jeong, S. K. et al. Biological dosimetry dose-response curves for residents living near nuclear power plants in South Korea. Sci. Prog. 106, 368504231198935 (2023).

Edwards, A. A. The use of chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes for biological dosimetry. Radiat. Res. 148 (Supplement), S39–EstimatedDose4 (1997).

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Cytogenetic Analysis for Radiation Dose Assessment: A Manual, Technical Report No. 405. Vienna, (2011).

Patil, S. R., Merrick, S. & Lubs, H. A. Identification of each human chromosome with a modified Giemsa stain. Science 173, 821–822 (1971).

International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Radiological Protection- Performance Criteria for Service Laboratories Performing Biological Dosimetry by Cytogenetics. ISO 19238. Geneva, (2023).

Utsumi, K. R. Scanning electron microscopy of Giemsa-stained chromosomes and surface-spread chromosomes. Chromosoma 86, 683–702 (1982).

M’Kacher, R. et al. High resolution and automatable cytogenetic biodosimetry using in situ telomere and centromere hybridization for the accurate detection of DNA damage: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 5699 (2023).

Castleman, K. R., Schulze, M. & Wu, Q. Automated biodosimetry using digital image analysis of fluorescence in situ hybridization specimens. Radiat. Res. 148 (Supplement), S71–S75 (1997).

Lloyd, D. C., Edwards, A. A. & Szłuińska, M. The minimum detectable dose by biodosimetry in a radiation overexposure. In Radiation Risk Estimates in Normal and Emergency Situations (eds Cigna, A. A. & Durante, M.) 253–258 (Springer Netherlands, 2006).

Goto, K., Akematsu, T., Shimazu, H. & Sugiyama, T. Simple differential Giemsa staining of sister chromatids after treatment with photosensitive dyes and exposure to light and the mechanism of staining. Chromosoma 53, 223–230 (1975).

Price, C. M. Fluorescence in situ hybridization. Blood Rev. 7, 127–134 (1993).

Cui, C., Shu, W. & Li, P. Fluorescence in situ hybridization: Cell-Based genetic diagnostic and research applications. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 4, 89 (2016).

Nietzel, A. et al. A new multicolor-FISH approach for the characterization of marker chromosomes: Centromere-specific multicolor-FISH (cenM-FISH). Hum. Genet. 108, 199–204 (2001).

Karachristou, I. et al. Triage biodosimetry using centromeric/telomeric PNA probes and Giemsa staining to score dicentrics or excess fragments in non-stimulated lymphocyte prematurely condensed chromosomes. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 793, 107–114 (2015).

Fazel, R. et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl. J. Med. 361, 849–857 (2009).

Lee, W. J. et al. Occupational radiation exposure and cancer incidence in a cohort of diagnostic medical radiation workers in South Korea. Occup. Environ. Med. 78, 876–883 (2021).

Adliene, D., Griciene, B., Skovorodko, K., Laurikaitiene, J. & Puiso, J. Occupational radiation exposure of health professionals and cancer risk assessment for Lithuanian nuclear medicine workers. Environ. Res. 183, 109144 (2020).

Shi, L. et al. A modified system for analyzing ionizing radiation-induced chromosome abnormalities. Radiat. Res. 177, 533–538 (2012).

Iwasaki, T., Takashima, Y., Suzuki, T., Yoshida, M. A. & Hayata, I. The dose response of chromosome aberrations in human lymphocytes induced in vitro by very low-dose γ rays. Radiat. Res. 175, 208–213 (2011).

Lusiyanti, Y. et al. Dose-response curve of chromosome aberrations in human lymphocytes induced by gamma-rays. Atom Indo. 39, 124 (2014).

Lee, Y. H. et al. An intercomparison exercise to compare scoring criteria and develop image databank for biodosimetry in South Korea. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 97, 1199–1205 (2021).

Ainsbury, E. A. & Lloyd, D. C. Dose Estimation software for radiation biodosimetry. Health Phys. 98, 290–295 (2010).

Funding

This work was supported by the Dongnam Institute of Radiological & Medical Sciences (DIRAMS) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No.50491 − 2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W. S. J., S. J. O.; methodology, S. K. J., S. J. O., and M. H. J.; blood sample irradiation, Y. R. K., H. J. K., and Y. U.K.; investigation, H. S. C., C. G. L., M. T. P., J. H. B., and J. S. K.; writing—original draft preparation, H. S. C., S. J. O., and M. H. J.; writing—review and editing, W. S. J.; supervision, M. H. J., S. J. O. and W. S. J.; project administration, S. J. O. and W. S. J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeong, M.H., Choi, H.S., Jeong, S.K. et al. Optimized dicentric chromosome dose–response curves with centromere probes improve low-dose radiation biodosimetry. Sci Rep 16, 1722 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31413-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31413-3