Abstract

This study aimed to develop and validate machine learning models to predict sarcopenia risk in stroke patients and to identify the most relevant clinical features associated with its occurrence. In this prospective study, 425 stroke patients were enrolled between October 2024 and April 2025. Patients from Kunming First People’s Hospital (n = 308) formed the training cohort, while those from Kunming Yan’an Hospital (n = 117) comprised the validation cohort. Feature selection was performed using a random forest algorithm. Five machine learning models—logistic regression, decision tree, random forest, naïve Bayes, and gradient boosting—were developed and evaluated using accuracy, recall, precision, specificity, F1 score, and area under the curve (AUC). SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were applied to the best-performing model to interpret key predictors. Of the 425 patients, 145 (34.1%) were diagnosed with sarcopenia. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed between the sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia groups across multiple clinical variables. The random forest model demonstrated the best predictive performance across all metrics. SHAP analysis revealed BMI, serum albumin, age, uric acid, creatinine, hemoglobin, calcium, triglycerides, C-reactive protein, total protein, and urea as the most influential predictors, reflecting nutritional, metabolic, and inflammatory status. The random forest model achieved superior performance in predicting sarcopenia risk after stroke. Combining machine learning with SHAP interpretability offers a robust and explainable framework for early identification and personalized management of post-stroke sarcopenia, supporting precision geriatric care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke remains one of the leading causes of long-term disability worldwide, with approximately 50% of survivors experiencing persistent functional impairment and 15–30% developing severe disabilities1. Growing attention has been directed toward the impact of stroke on skeletal muscle health, as neurological deficits and reduced mobility can accelerate muscle atrophy, impair strength, and decrease physical performance2. Sarcopenia, defined as the progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function, is highly prevalent among older adults3. Stroke-associated sarcopenia (SAS) represents a subtype of secondary sarcopenia characterized by muscle degeneration resulting from stroke-related neurological injury, inflammation3, and long-term physical inactivity4. SAS not only increases the risk of falls, fractures, and adverse clinical outcomes but also delays rehabilitation progress and imposes a substantial burden on healthcare systems5.

Currently, the clinical identification of SAS primarily relies on muscle strength testing and physical performance assessments. However, these approaches may fail to capture early or subtle muscle deterioration, limiting their utility for timely risk stratification and early interventions6. Consequently, accurate predictive tools are needed to facilitate early recognition of high-risk patients and guide individualized rehabilitation strategies.

In recent years, several studies have attempted to develop predictive models for stroke-related sarcopenia using traditional or basic machine-learning approaches. A Chinese study using a logistic regression model reported an AUC of 0.835. More recently, another study applying logistic regression, random forest, and XGBoost yielded only modest performance, with AUCs of 0.805, 0.796, and 0.780, respectively7. Although these studies provide preliminary evidence supporting the feasibility of predictive modeling, they consistently suffer from several limitations: most rely on a single modeling strategy, lack external validation, and provide limited interpretability, making it difficult for clinicians to understand how individual predictors contribute to model outputs. These methodological constraints restrict the clinical applicability of current models. To address these gaps, our study systematically compares five mainstream machine-learning algorithms, incorporates external cohort validation, and applies SHAP interpretability analysis to enhance transparency and provide clinically meaningful insights for early risk identification of stroke-related sarcopenia. To address these gaps, the present study integrates five mainstream machine learning (ML) algorithms to construct predictive models for SAS risk, systematically compares their predictive performance, and—most importantly—incorporates SHAP-based interpretability to elucidate the relative contribution of each feature. By enhancing model transparency and generalizability, this approach aims to support early screening and tailored intervention strategies for stroke patients at high risk of developing sarcopenia.

Methods

Study population

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit stroke patients from two tertiary hospitals in Kunming, China, between October 2024 and April 2025.The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients diagnosed with hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, including both first-ever and recurrent cases; (2) Age ≥ 60 years; (3) Clinically stable condition; (4) Provision of written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Pre-existing sarcopenia before admission, defined by a SARC-F score > 48; (2) Severe coma, intellectual disability, psychiatric disorders, or cognitive impairment preventing cooperation with body composition analysis; (3) History of major psychiatric illness or severe systemic disease; (4) Severe comorbidities such as heart failure, renal failure, malignancy, or end-stage organ disease; (5) Severe upper limb spasticity or pain that interfered with grip strength testing.

Assessment tools

General information questionnaire

A self-designed questionnaire was developed by the research team based on study objectives. Data collected included age, sex, smoking status, alcohol use, duration of bed rest, body mass index (BMI), presence of anxiety or depression, stroke type (ischemic or hemorrhagic), history of stroke, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease), pulmonary infections, fracture history, fall history, dysphagia, aphasia, muscle weakness, nasogastric tube use, and laboratory data serum albumin, total protein, C-reactive protein, serum calcium, urea, creatinine, uric acid, hemoglobin, triglycerides.

Diagnosis of sarcopenia

Sarcopenia was diagnosed according to the criteria proposed by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia9 Diagnostic criteria included: (1)Low muscle mass: appendicular skeletal muscle mass index (SMI) ≤ 7.0 kg/m2 for men and < 5.4 kg/m2 for women; (2) Low muscle strength: handgrip strength < 28 kg for men and < 18 kg for women; (3) Poor physical performance: 6-m gait speed < 1.0 m/s. A diagnosis of sarcopenia was made if criterion (1) was met, along with either (2), (3), or both.

National institutes of health stroke scale (NIHSS)

The NIHSS, developed by Brott et al. in 198910, was used to assess the severity of neurological impairment in stroke patients. The scale includes 11 items, covering level of consciousness, visual fields, facial palsy, limb movements, language, attention, and other domains. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 4, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 42. Higher scores indicate more severe neurological deficits. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.939, indicating high internal consistency. The NIHSS is widely used in both clinical and research settings for stroke assessment.

Glasgow coma scale (GCS)

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), developed by Teasdale and Jennett in 1974, was used to assess consciousness and neurological function. The scale comprises three components: eye-opening, verbal response, and motor response. Each component is scored separately (eye-opening: 1–4, verbal response: 1–5, motor response: 1–6), yielding a total score range of 3–15. Higher scores indicate a more alert state of consciousness. The GCS demonstrated good reliability and validity in the stroke population in this study11.

Activities of daily living (ADL) scale

The ADL scale, originally developed by Katz et al. in 1963, was employed to evaluate the basic self-care ability of participants. The scale includes six items: feeding, dressing, toileting, bathing, mobility, and transferring. Each item is scored based on the degree of independence: 1 (complete dependence), 2 (partial dependence), or 3 (complete independence). The total score ranges from 6 to 18, with higher scores indicating greater functional independence. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.978, suggesting excellent internal consistency12.

Data collection and quality control

Data were collected through a combination of paper-based questionnaires and in-person clinical assessments conducted at participating hospitals. Each hospital designated a trained investigator responsible for overseeing the data collection process. The questionnaire included items assessing demographic characteristics, medical history, lifestyle factors, and relevant clinical symptoms. Clinical assessments involved standardized measurements such as blood pressure, height, weight, and other relevant parameters, depending on the study’s objectives. Standardized instructions were provided to all participants prior to questionnaire completion to ensure responses were informed, voluntary, and anonymous. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of all participating hospitals, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Upon completion, all questionnaires were returned to the central research team. Data were independently reviewed and double-entered into a secured database to minimize input errors. Invalid or incomplete questionnaires—such as those with excessively short completion times, missing data, or patterned/duplicate responses—were identified and excluded from the final analysis.

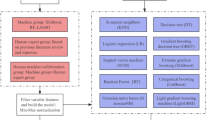

Machine learning model parameters

To ensure reproducibility, the hyperparameters of all machine learning models used in this study (Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Naive Bayes, and Gradient Boosting) were summarized in Supplementary Table 1. All models were implemented using scikit-learn with default settings unless otherwise specified. The max_iter parameter of Logistic Regression was set to 1000 to ensure convergence. Additionally, confusion matrices were generated for all five machine-learning models to evaluate the distribution of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives in both the training and external validation cohorts. To further examine potential multicollinearity among the selected predictors, pairwise correlations were evaluated, and no strong correlations were identified (all |r|< 0.7).

Results

General characteristics of participants and prevalence of sarcopenia

A total of 456 questionnaires were collected, of which 425 were deemed valid, yielding a valid response rate of 93.2%. Among the 425 included stroke patients, 145 (34.1%) were diagnosed with stroke-related sarcopenia (SAS) based on the AWGS diagnostic criteria, while the remaining 280 were classified as non-sarcopenic. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are presented (Table 1).

For model development, the dataset was randomly divided into a modeling cohort and an external validation cohort using stratified sampling based on the outcome variable. The modeling cohort consisted of 280 participants, while the external validation cohort included 145 participants. Comparison of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between the two cohorts showed no significant differences across major variables, indicating good balance and comparability between the training and validation sets (Table 2). This ensured that the subsequent evaluation of model performance was conducted on a representative and unbiased cohort.

Feature selection for stroke-related sarcopenia risk factors

To identify key predictors of stroke-related sarcopenia, a random forest (RF) algorithm was employed to rank the importance of all candidate variables. Features with importance scores exceeding the average threshold value (0.031) were selected for model inclusion. This cutoff was chosen to balance variable interpretability and model complexity in practical applications. Based on the importance ranking, 12 key features were retained for model development: BMI, serum albumin, age, uric acid, hemoglobin, creatinine, calcium ions, NIHSS score, total protein, triglycerides, CRP, and urea. The results of feature selection are illustrated (Fig. 1). Correlation analysis confirmed that no excessive multicollinearity existed among the selected predictors.

Development and evaluation of predictive models for stroke-related sarcopenia

In this study, five machine learning algorithms were applied to construct predictive models for assessing the risk of sarcopenia in stroke patients. All models were trained using the modeling cohort and evaluated in an independent validation cohort to assess generalizability. As shown Fig. 2, the RF and GB models demonstrated the best performance in the training set, with area under the ROC curve values of 0.967and 0.943, respectively—both significantly outperforming the other models. Notably, the RF model achieved superior performance across several key classification metrics, including F1-score, accuracy, and recall, indicating strong overall predictive capability. Although the GB model exhibited a slightly higher AUC than RF in the validation set, the RF model demonstrated more consistent and robust performance across both datasets. Therefore, the Random Forest model was selected as the optimal predictive model for stroke-related sarcopenia in this study. The detailed performance metrics of all models are summarized (Table 3). In addition, to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of model performance, the confusion matrices for all five algorithms in both the modeling and external validation cohorts have been included in the Supplementary Materials (Figs. S1and S2). These matrices clearly illustrate the classification behavior of each model and help identify potential misclassification patterns.

Interpretability analysis of the stroke-related sarcopenia prediction model

Contribution of key features to model prediction

To enhance the interpretability of the model, SHAP analysis was applied to the RF model to assess the importance and directional impact of each feature in predicting stroke-related sarcopenia. The distribution of SHAP values for the 12 selected features is presented (Fig. 3). The results indicated that lower values of BMI and serum albumin were consistently associated with higher SHAP values, highlighting the critical role of poor nutritional status in sarcopenia risk. Similarly, higher SHAP values were observed in older individuals, reinforcing age as a strong independent risk factor. While some variables exhibited relatively lower average contributions, they still demonstrated substantial SHAP values in certain individuals, suggesting their potential relevance in personalized risk assessment.

Relationships between key variables and model predictions

Figure 4 presents SHAP dependence plots for the top six continuous variables ranked by feature importance: BMI, serum albumin, age, uric acid, creatinine, and hemoglobin. The x-axis represents the actual observed values of each variable, while the y-axis indicates the corresponding SHAP values, which reflect each variable’s magnitude and direction of influence on the model’s prediction. Figure 4A, B reveal a generally negative correlation between SHAP values and both BMI and serum albumin levels, suggesting that lower values of these variables significantly increase the predicted risk of sarcopenia—highlighting their close association with poor nutritional status. As shown (Fig. 4C), age exhibits a clear positive correlation with SHAP values, indicating that older age is a strong positive predictor of sarcopenia risk. In Fig. 4D, E, increases in uric acid and creatinine levels are associated with declining SHAP values, possibly reflecting underlying metabolic dysfunction or impaired muscle metabolism. Finally, Fig. 4F shows that lower hemoglobin levels correspond to higher SHAP values, implying that anemia may contribute to an elevated likelihood of sarcopenia in stroke patients.

SHAP-based interpretations of individual predictions

Figure 5 displays SHAP force plots for two individual stroke patients, illustrating the contribution and direction of each feature in the prediction of sarcopenia risk. These visualizations offer a detailed, patient-specific explanation of how the model arrives at its final output. In the left panel, the baseline prediction probability was 0.347, which increased to 0.82 after accounting for multiple contributing factors, leading the model to classify the patient as high-risk. Among these features, BMI (17.8) emerged as the most influential positive contributor (SHAP + 0.37), followed by hemoglobin, age, and uric acid, all of which provided additional upward influence on the prediction. In contrast, creatinine and total protein had modest negative contributions, slightly lowering the risk score. In the right panel, the final prediction decreased from the baseline to 0.02, primarily due to negative contributions from BMI, age, uric acid, and creatinine, resulting in a low-risk classification. Overall, the SHAP force plots clearly illustrate how individual variables influence the model’s prediction trajectory, making explicit both the direction and magnitude of each variable’s effect. These findings highlight the model’s strong interpretability and clinical transparency at the individual patient level.

Discussion

Elevated risk of sarcopenia among stroke patients

The findings of this study revealed that 34.1% of stroke patients met the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, a prevalence notably higher than that observed in patients with cardiovascular disease13, diabetes14, respiratory system15. This suggests that stroke survivors represent a particularly high-risk population for sarcopenia, consistent with the findings reported by Yao16. The underlying mechanisms contributing to sarcopenia in stroke patients are multifactorial. They may include reduced physical activity due to motor dysfunction, acute-phase systemic inflammation, and inadequate nutritional intake. In addition, stroke predominantly affects the elderly, who typically have lower baseline muscle reserves and are more likely to suffer from comorbid chronic conditions such as coronary artery disease and hypertension, further accelerating muscle mass loss17,18.

Moreover, the lack of effective rehabilitation interventions during the post-stroke recovery period can exacerbate the progression of sarcopenia. Therefore, early identification of high-risk individuals is essential to improve rehabilitation outcomes and enhance quality of life. Against this background, our study aimed to apply machine learning algorithms to develop robust prediction models and to identify the key factors contributing to stroke-related sarcopenia, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for personalized risk stratification and targeted intervention strategies.

Performance of machine learning models in predicting stroke-related sarcopenia

To enhance model efficiency and minimize the influence of redundant variables, a RF algorithm was employed to perform initial feature selection19. Compared with traditional feature selection methods, RF is capable of capturing complex non-linear interactions among variables and demonstrates strong robustness to outliers and noise, while preserving model interpretability. Through this process, a total of 12 key variables were identified as strongly associated with sarcopenia: BMI, serum albumin, age, uric acid, serum creatinine, hemoglobin, calcium ion, NIHSS score, triglycerides, CRP, total protein, and urea. Based on these selected features, five machine learning models were developed: LR, DT, RF, NB, and GB. All models were trained using five-fold cross-validation and subsequently evaluated on an independent validation set to assess their generalizability. Among the five models, the RF model demonstrated superior performance in both the training and validation cohorts, with higher accuracy, recall, and F1 scores, alongside better robustness and interpretability. As such, the RF model was selected as the optimal predictive tool in this study for identifying sarcopenia risk in stroke patients.

In addition, we observed inconsistent performance of the Naïve Bayes (NB) model, which showed relatively poor discrimination in the training cohort but performed noticeably better in the external validation cohort. This discrepancy is largely attributable to the class imbalance between the two datasets, as the modeling set contained a lower proportion of sarcopenia cases than the validation set. Because NB relies on prior probability estimation, its performance is more susceptible to shifts in class distribution. Furthermore, the selected predictors did not exhibit strong intercorrelations, indicating a low risk of multicollinearity and ensuring that the divergent performance of NB was not caused by feature redundancy. The confusion matrices generated for both the training and validation sets (Supplementary Fig. S1) provided additional insight into class-level errors. The NB model exhibited higher false-negative rates in the training cohort but yielded more balanced predictions in the external validation dataset. These findings highlight the importance of examining misclassification patterns—rather than relying solely on global metrics such as accuracy or AUC—when assessing model robustness. In comparison with previously published models, the predictive performance of our machine-learning framework demonstrates several notable advantages. A Chinese study using a logistic regression model reported an AUC of 0.835, while another study applying both logistic regression and decision tree algorithms achieved AUCs of 0.959 and 0.892, respectively. Although these models demonstrated acceptable discriminative ability, they relied on single modeling approaches and lacked external validation. More recently, a study employing random forest and XGBoost reported relatively modest AUCs of 0.796 and 0.780, suggesting limited generalizability of these basic machine-learning applications7. In contrast, our RF model maintained consistently strong and balanced predictive performance in both the training and external validation cohorts, demonstrating improved robustness over existing models. Furthermore, by incorporating SHAP-based interpretability, our study provides transparent and clinically meaningful insights into feature contributions—an aspect largely absent in previous research—thereby reinforcing the novelty and practical applicability of our approach.

Analysis of key predictive factors for stroke-related sarcopenia

SHAP analysis based on the RF model identified BMI, serum albumin, age, uric acid, serum creatinine, hemoglobin, calcium ion, NIHSS score, triglycerides, CRP, total protein, and urea as the most important variables contributing to sarcopenia prediction. These features span multiple physiological domains, including nutritional status, metabolic function, inflammatory activity, and overall physiological condition.

In terms of nutrition-related factors, lower levels of serum albumin and total protein suggest a high likelihood of malnutrition, which is a well-established contributor to muscle wasting and sarcopenia20. A low BMI reflects underweight status, which is often accompanied by loss of both fat and lean muscle mass, ultimately impairing muscle strength and physical function21. Interestingly, the model also flagged some individuals with a high BMI as being at elevated risk for sarcopenia, suggesting the presence of sarcopenic obesity—a condition in which excess body fat may mask underlying skeletal muscle loss22. This highlights the limitation of using BMI alone for clinical risk assessment and underscores the need for integrating body composition analysis to improve diagnostic precision. From a metabolic perspective, lower cholesterol and triglyceride levels, both indicative of reduced energy reserves or disrupted lipid metabolism, may negatively impact muscle protein synthesis23. Inflammatory and metabolic markers such as CRP, urea, creatinine, and uric acid also ranked highly in model importance. Elevated CRP levels, a classical marker of systemic inflammation, are known to inhibit muscle protein synthesis and promote catabolism24. Uric acid, creatinine, and urea levels reflect renal and muscle metabolic by-products, suggesting possible impairment in muscle metabolism25,26.Among the hematological and electrolyte indicators, low hemoglobin levels were associated with increased sarcopenia risk, likely due to compromised oxygen delivery to muscle tissue and reduced endurance capacity27. Additionally, calcium, a critical mediator of neuromuscular signaling, may contribute to muscle dysfunction if depleted28. Age, a non-modifiable risk factor, was identified as a strong positive predictor of sarcopenia in the model, reaffirming that older adults are particularly vulnerable29. This association may be linked to age-related declines in hormone levels, persistent low-grade inflammation, and reduced physical activity. Importantly, SHAP force plots revealed distinct variable contribution pathways between high-risk and low-risk individuals, reinforcing the model’s effectiveness in capturing personalized risk profiles30. This interpretability enhances clinical applicability and provides a foundation for tailoring targeted interventions.

In summary, the key variables identified in this study offer a multidimensional perspective on the pathogenesis of stroke-related sarcopenia and support the development of personalized risk stratification, early intervention, and rehabilitation strategies in clinical practice.

Conclusions

This study developed five machine learning models to predict the risk of sarcopenia among stroke patients. Among these, the RF model demonstrated superior performance across multiple evaluation metrics compared to traditional models such as LR, DT, NB, and GB. The application of machine learning offers a novel and efficient approach to identifying high-risk individuals for stroke-related sarcopenia and provides insights into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. These findings may support the development of personalized prevention strategies and precision rehabilitation plans.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively limited, which may affect the generalizability of the model. Second, although the model incorporated a broad range of physiological and biochemical indicators, certain potentially relevant variables—such as body composition metrics, hormone levels, and physical activity data—were not included. Future research should focus on expanding the sample size, enriching the feature set, and conducting external validation across multiple clinical centers and geographic regions. Such efforts will help to further enhance the model’s robustness, generalizability, and clinical utility.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barthels, D. & Das, H. Current advances in ischemic stroke research and therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1866, 165260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.09.012 (2020).

Krahn, G. L. WHO World report on disability: A review. Disabil. Health J. 4, 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2011.05.001 (2011).

He, X. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia in patients with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 48, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-03143-z (2024).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. & Sayer, A. A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 393, 2636–2646. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31138-9 (2019).

Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459–480, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30499-x (2019).

Motyer, R., Asadi, H., Thornton, J., Nicholson, P. & Kok, H. K. Current evidence for endovascular therapy in stroke and remaining uncertainties. J. Intern. Med. 283, 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12653 (2018).

Yan, H. et al. Personalised screening tool for early detection of sarcopenia in stroke patients: A machine learning-based comparative study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 37, 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-025-02945-5 (2025).

Ishida, Y. et al. SARC-F as a screening tool for sarcopenia and possible sarcopenia proposed by AWGS 2019 in hospitalized older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 24, 1053–1060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1462-9 (2020).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300-307.e302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012 (2020).

Lyden, P. D., Lu, M., Levine, S. R., Brott, T. G. & Broderick, J. A modified national institutes of health stroke scale for use in stroke clinical trials: preliminary reliability and validity. Stroke 32, 1310–1317. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.32.6.1310 (2001).

Mehta, R. & Chinthapalli, K. Glasgow coma scale explained. BMJ 365, l1296. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1296 (2019).

Devi, J. The scales of functional assessment of activities of daily living in geriatrics. Age Ageing 47, 500–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy050 (2018).

Damluji, A. A. et al. Sarcopenia and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 147, 1534–1553. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.123.064071 (2023).

Sanz-Cánovas, J. et al. Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in elderly patients with frailty and/or sarcopenia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 8677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148677 (2022).

Yan, H. et al. Risk factors of stroke-related sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Aging 6, 1452708. https://doi.org/10.3389/fragi.2025.1452708 (2025).

Yao, R. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of stroke-related sarcopenia at the subacute stage: A case control study. Front. Neurol. 13, 899658. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.899658 (2022).

Landi, F. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia among nursing home older residents. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr035 (2012).

Cho, M. R., Lee, S. & Song, S. K. A review of sarcopenia pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment and future direction. J. Korean Med. Sci. 37, e146. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e146 (2022).

Wallace, M. L. et al. Use and misuse of random forest variable importance metrics in medicine: Demonstrations through incident stroke prediction. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 23, 144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-023-01965-x (2023).

Soeters, P. B., Wolfe, R. R. & Shenkin, A. Hypoalbuminemia: Pathogenesis and clinical significance. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral. Nutr. 43, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpen.1451 (2019).

Janssen, I., Heymsfield, S. B., Wang, Z. M. & Ross, R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(89), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81 (2000).

Bilski, J., Pierzchalski, P., Szczepanik, M., Bonior, J. & Zoladz, J. A. Multifactorial mechanism of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Role of physical exercise. Microbiota Myokines Cells 11, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11010160 (2022).

Yanming, M. et al. Association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and sarcopenia based on NHANES. Sci. Rep. 14, 30166. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81830-z (2024).

Hsu, W. H. et al. Novel metabolic and lipidomic biomarkers of sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 15, 2175–2186. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13567 (2024).

Yim, J., Son, N. H., Kyong, T., Park, Y. & Kim, J. H. Muscle mass has a greater impact on serum creatinine levels in older males than in females. Heliyon 9, e21866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21866 (2023).

Khalil, M. et al. Multidimensional assessment of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in geriatric patients: Creatinine/cystatin c ratio performs better than sarcopenia index. Metabolites 14, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14060306 (2024).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing 39, 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq034 (2010).

Liu, Q. Q. et al. High intensity interval training: A potential method for treating sarcopenia. Clin. Interv. Aging 17, 857–872. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S366245 (2022).

Kwan, P. Sarcopenia, a neurogenic syndrome?. J. Aging Res. 2013, 791679. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/791679 (2013).

Aslam, M. A., Ma, E. B. & Huh, J. Y. Pathophysiology of sarcopenia: Genetic factors and their interplay with environmental factors. Metabolism 149, 155711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155711 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the research librarian for assisting in the development and review of the search strategies.

Funding

This work was supported by the Master’s Degree Candidate Innovation Fund of Kunming Medical University (Grant No. 2025S216) and the Kunming Municipal Health Scientific Research Project (Grant No. 2025-14-02-0010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. conceived and designed the study. J.W., M.M., and J.Z. collected the data. J.W. and X.Y. organized and analyzed the data. J.W. drafted and revised the manuscript and performed the result interpretation. YG supervised the implementation of the study, assessed feasibility, ensured quality control, and provided funding support. All authors contributed to editorial revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kunming First People’s Hospital (Approval No. YLS2024-101) and the Ethics Committee of Kunming Yan’an Hospital (Approval No. 2025-011-01). All research procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their legal guardians included in the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Mu, M., Zhang, J. et al. Development of machine learning-based models for predicting sarcopenia risk in stroke patients and analysis of associated factors. Sci Rep 16, 1490 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31600-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31600-2