Abstract

For individuals with dyskinesia, postoperative walking rehabilitation is crucial, and lower limb exoskeletons provide effective training assistance. This paper proposes a method for designing a lower limb exoskeleton based on sensor feedback and human-robot gait simulation. Firstly, a mathematical model of lower limb motion and an exoskeleton robot model are designed based on hip/knee joint motion and gait mechanisms. Secondly, gait simulation is performed via human-robot coupling, with a comparative analysis of lower limb muscle dynamics during walking. Hip/knee motion data is converted into motion function curves for dynamic simulation verification. Subsequently, a brushless motor drive control system for the lower limb exoskeleton is developed using Simulink, and simulation experiments are conducted for position, speed, and torque control. Finally, patient walking experiments using membrane pressure and pose sensors analyze hip/knee and plantar pressure data, enabling output adjustment feedback and closed-loop torque control of the exoskeleton.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) syndrome is characterized by structural abnormalities of the hip joint, leading to persistent pain and restricted mobility. It is a significant contributor to hip discomfort and early-onset osteoarthritis, particularly in the young and middle-aged population1,2. Given its high prevalence and notable clinical impact3, targeted lower limb rehabilitation is crucial. However, traditional rehabilitation tools, such as crutches and rehabilitation handrails, rely heavily on upper limb strength. The weakness of the upper limbs in patients often results in excessive weight-bearing on the lower limbs, weakening the rehabilitation effect and failing to meet the precise rehabilitation needs of FAI patients.

In contrast, active exoskeleton robots can adapt to environmental changes and effectively assist individuals with lower limb dysfunction in improving mobility, enhancing muscle strength, and maintaining bone density. This technology has made significant progress in the medical field4, with representative products including HAL5, ReWalk6, Honda SMA7, and the lightweight and efficient GEMS II8. The driving technology has evolved from hydraulic/pneumatic systems to electric and intelligent systems, from Hardiman I9 and EXPOS10 to Series Elastic Actuator (SEA) robots11, ultimately achieving mechatronic intelligent control12. These developments provide technical support for precise lower limb rehabilitation. Modern powered exoskeletons are rapidly advancing towards intelligence, lightweight design, and precision.

This study aims to design an intelligent lower limb rehabilitation robot tailored for FAI patients based on OpenSim gait simulation software. On one hand, it will simulate the movement dynamics and gait muscle strength characteristics of FAI patients to explore the efficacy of assistive forces. On the other hand, the integration of sensors will create a specialized gait database for FAI, enhancing the device’s adaptability to individual patient differences.

Lower limb movement mechanism

Gait motion and spatio-temporal characterization

Gait, which describes walking posture, provides insights into body configuration and dynamics. In this study, we will focus on analyzing the sagittal plane13 gait trends of the lower limbs, noting their periodic characteristics during stable walking14. As illustrated in Fig. 1.

Gait cycles are defined as the movement from one foot’s heel making contact with the ground to the ground once more, primarily involving two stages: support and swing15. Approximately 60% of the cycle is dedicated to the support phase, which encompasses both single and double-foot support, with the single-foot support being divided into intermediate and final stages. Two instances of bipedal support take place, each constituting roughly 10% of the cycle. The swing stage, constituting roughly 40% of the cycle, spans from toe elevation to heel contact with the ground, segmented into three stages: initial, intermediate, and concluding phases16.

Characterization of hip and knee motion

The fundamental structure of the hip joint, akin to a standard ball and socket joint, is found at the tight junction of the femoral head and the acetabulum17.As illustrated in Fig. 2.

Comprising the distal femur, proximal tibia, and patella, the knee joint is a multifaceted hinge joint. Accurately depicting the movement path of the human lower limb’s gait depends on the coordinated movement of the hip and knee. As depicted in Fig. 3.

Research on human anatomy18 has meticulously detailed that the hip joint is capable of executing three fundamental types of movement: flexion and extension, which typically span from 0° to 120°; internal and external rotation, ranging approximately from − 45° to 45°; and abduction and adduction, which can vary between − 30° to 30° and − 20° to 20°, respectively. In contrast, the movement pattern of the knee joint is relatively uniform, primarily characterized by its substantial range of flexion and extension, which can reach up to 135° from full extension (0°). This flexibility is vital for facilitating lower extremity activities such as walking and jogging.

Minor movements or degrees of freedom (DOFs) at the hip and knee, such as circumduction or axial rotation beyond the aforementioned ranges, generally exert minimal influence on standard walking and movement patterns, and therefore, they are not typically regarded as primary DOFs in biomechanical analyses. As quantitatively depicted in Table 1, the hip and knee joints exhibit distinct and substantial ranges of motion in every direction of freedom, highlighting the complexity and diversity of human locomotor kinematics.

According to the preceding chart, the hip joint predominantly undergoes flexion and extension while walking and running, along with minor abduction, adduction, and rotation. Flexion and extension should be confined to a 60° range, with minimal movement in other directions. Flexion and extension primarily control the knee joint, yet the magnitude is greater, allowing for the disregard of both internal and external rotational movements.

Motion mathematical modeling of intelligent lower limb exoskeleton systems

Modified D-H method of motion model construction

The purpose of analyzing the kinematic model of the lower limb exoskeleton is to determine and scrutinize the operational link between the angles of joints and the spatial locations of moving linkage mechanisms19.Typically, gait analysis occurs in a two-dimensional framework, with all kinematic analysis computations confined to the sagittal plane. For determining kinematics, the MDH (Modified D-H coordinate system) technique was employed. The movement of the human lower extremity is reduced to a sequential linkage of three connecting joints, with the parameters linking these two joints depicted in Fig. 4.

The human lower limb is simplified to a tripartite link as shown in Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5:

x0y0,x1y1,x2y2,x3y3——global, Hip joint, Knee joint, Ankle joint coordinate system.

θ1, θ2, θ3——hip, knee, and ankle rotations in the sagittal plane.

L1,L2,L3——thigh, calf, foot segment.

Ψ——Angle between ankle-hip and thigh L1.

φ——Angle between the sole of the foot and x0y0.

P——the sole of the foot.

Positive kinematics analysis of lower limb intelligent lower limb exoskeleton systems

FK involves deducing the end-effector’s movement from the robot’s joint motion, specifically its position and orientation based on joint coordinates.

In the Table 2:

\(\:{\alpha\:}_{i-1}\)(rad)——Around the\(\:{\:x}_{i-1}\) axis, \(\:{Z}_{i-1}\) rotates to the angle\(\:\:{Z}_{i}\).

\(\:{a}_{i-1}\)(mm)——From the axis, moves the distance to \(\:{Z}_{i}\).

\(\:{d}_{i}\)(mm)—— Along the axis, move the distance to \(\:{x}_{i}\).

\(\:{\theta\:}_{i}\)(°)—— Around the axis, the angle of rotation to \(\:{x}_{i}\).

Table 2’s data is integrated into the transformation matrix equation for the adjacent coordinate system in the enhanced DH parameter approach.

By substituting the improved parameters in the D-H table into Formula 1, the rotation matrix \(\:{}_{1}{}^{0}T\) can be obtained, which is shown as follows:

The transformation matrix (_3^0)T for the whole system is:

(5) The parameters in Eq. 2 are:

The information about the position of the endpoint P on the bar 3 is

PX, PY of endpoint P in X0Y0 can be deduced from Eq. 5.

Preceding analysis indicates precise inference of human plantar position/posture from hip/knee movement details.

Inverse kinematics analysis of lower limb intelligent lower limb exoskeleton systems

IK calculates robot’s joint coords based on end-effector’s pos/orient in a triangle formed by thigh, calf to initial endpoints20 (Fig. 6). Cosine theorem aids derivation/analysis (Eq. 6).

In Eq. 6, θ₂ & ψ values are determined, Since θ2 represents the rotation angle of the lower leg joint relative to the thigh joint, with counterclockwise rotation defined as the positive direction, anatomical considerations dictate that θ2 should assume a negative value. θ₁ & θ₃ are then inferred via trigonometric geo relations in Eq. 7.

L1,L2——The length of the thighs and calves.

θ1, θ2——The rotational angles of the hip joint and knee joint on the sagittal plane.

\(x,y\)——The coordinate position at the end of the ankle.

Ψ——Angle between ankle-hip and thigh L1.

φ——The angle between the foot base and the hip reference coordinate system.

From Eq. 7, analyzing P’s global (x, y) infers joint angles accurately. MATLAB modeled tripartite system, validating FK & IK as shown in Fig. 6.

The model sets the hip joint rotation angle\({\theta _1}= - 20^\circ\),knee joint rotation angle\({\theta _2}=20^\circ\),and ankle joint rotation angle\({\theta _3}= - 25^\circ\). Combined with the characteristic link length parameters\({L_1}=0.5m\),\({L_2}=0.3m\),\({L_3}=0m\), these values are substituted into formula 5 to obtain the coordinate of the end effector\({\text{X}}=0.7698m\),\({\text{Y}}=0.1294m\).This result is consistent with the experimental results\({\text{X}}=0.772m\),\({\text{Y}}=0.127m\), thereby proving the correctness of the model.This methodology ensures precise control over the motion process, thereby facilitating high-precision tracking and adjustment of the motion trajectories of robotic arms or robots.

Structure of intelligent lower limb exoskeleton system

Structural design and optimization

Based on human motion analysis & triple-link lower limb model, we developed an intelligent lower limb exoskeleton robot (Fig. 7).

The lower limb exoskeleton robot consists of 5 parts: backpack, hip/knee actuation, control, & power units. STM32F4 drives HT6010-J36 motor for thigh reciprocal/rotational motion (20°-75°) in hip joint. Rotary vice allows inward thigh rotation & abduction. STM32F4 MCU controls motor drive based on sensor signals. Made of lightweight Al alloy 6061 & carbon fiber (Fig. 8).

Internal limiters in hip joints restrict max rotational angle. Knee joint uses torsion spring for assisted movement.

Control system design

According to Brannstrom’s staging theory21, the rehabilitation process progresses through three sequential phases: the flaccid phase (initial stage) characterized by complete loss of voluntary control in the affected lower limb requiring full external assistance; the spastic phase (intermediate stage) marked by partial voluntary movement control necessitating repetitive gait training with rehabilitation devices to enhance central pattern generation and gradual motor function recovery; and the recovery phase (final stage) featuring significantly reduced spasticity, improved range of motion, and therapeutic focus on muscle strengthening and gait refinement for advanced functional restoration.

As illustrated in Fig. 9.The system employs a hierarchical control architecture comprising supervisory, execution, and sensory layers for multidimensional robotic rehabilitation control. The supervisory layer serves as the central decision-making unit for human-machine interaction and data management, transmitting commands to the execution layer. The execution layer decomposes motion trajectories and drives joint movements using biomechanically-adjusted motion profiles with fuzzy PID control for precise torque/speed regulation. The sensory layer integrates hip/knee position data, plantar pressure, and motor parameters to provide real-time feedback, ensuring training safety and efficacy. This architecture enables intelligent human-robot interaction and novel control methodologies for lower-limb exoskeletons.

Gait simulation experiment of intelligent lower limb exoskeleton system

Simulation and analysis of hip and knee gait based on open sim

OpenSim, an open-source platform, specializes in developing, sharing, & analyzing musculoskeletal & dynamic motion simulations, widely applied in medical device design, orthopedics, & rehab science22.The Open Sim gait simulation process is illustrated in Fig. 10.

This study adopts gait2392 model for lower limb kinematics simulation, with model scaling involving precise mass adjustments23. Figure 11 depicts model adaptation from 1.75 m/75kg to 1.73 m/65kg, with marker points fine-tuned for accuracy. RMS < 0.04 & max error < 0.05 significantly enhance model practicality & precision.

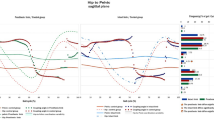

Within OpenSim, IK aims to infer joint angles from experimental data24. IK Tool25 loads kinematic data onto the scaled model, accurately replicating experimental body coordinates. This method mirrors joint angle variations. IK analysis, followed by OpenSim’s Plot function, visualizes hip, knee, & ankle angles over time, enabling dynamic angle observation (Fig. 12).

3-sec IK analysis illustrates hip, knee, & ankle angle dynamics. Sharp markers indicate modeling & placement issues. Static optimization & residual reduction boost precision. By decomposing joint moments into muscle forces & minimizing activations, optimization enhances inverse dynamics26. Residual reduction aims to eliminate non-physical balancing forces stemming from modeling & processing errors27. The algorithm refined IK curves by error elimination. Pre- & post-optimization comparisons (Fig. 13) underscore its impact on precision & reliability.

The RRA eliminates GRF imbalance, enhancing model dynamic coherence. Post-RRA, joint angle curves refine, aligning with real motion patterns.The 3-second simulation revealed periodic motion patterns in the hip (-28° to 13°) and knee joints (-67° to 3.5°), with the proposed method demonstrating significantly higher precision than conventional tabular estimation approaches, thereby offering more reliable data for robotics research.

Human-machine coupling modeling of intelligent lower limb exoskeleton system

For human-robot model coupling, revising the 2392 model’s source code to incorporate an exoskeleton geometric model is crucial. Integration is facilitated by the bodyset and attach commands28. The integration process is outlined in Fig. 14. Precise adjustments to positional parameters and scaling factors are essential for alignment with human anthropometrics, as shown in Fig. 15.

The walking data was input into the human-machine coupling model for simulation verification, and the results are shown in Fig. 16.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of coupled model muscle control

This study applies CMC to decipher muscle excitation, enabling dynamic musculoskeletal model movements to precisely track predefined kinematic paths under external loads29. Analysis compares muscle force variations in lower limbs during walking (Fig. 17).

As shown in Fig. 17, soleus & gastrocnemius muscles exhibited robust activation during gait, contrasting the strength of biceps femoris & R. gluteus maximus. Figure 18 presents a simulation comparing pre- & post-human usage muscle forces.

As shown in Fig. 18, the intelligent lower-extremity exoskeleton markedly reduced primary muscle strength, indicating effective force reduction during walking and essential mobility assistance. Pre- vs. post-robot use analysis indicated ~ 60% muscle force reduction.

Research on dynamic simulation of intelligent lower limb exoskeleton system

Construction of human hip and knee joint kinematics function

In OpenSim, IK captured hip & knee joint angle data, transferred to Matlab for curve fitting, elucidating temporal functional relationships. Compared with polynomial interpolation, the eight-term Fourier series demonstrates superior performance in fitting periodic curves, as evidenced by adjusted R² values exceeding 0.99 for all four fitted curves. This indicates excellent model-data agreement, as depicted in Fig. 19.

The eight-term Fourier function formula is presented in Eq. 8.

Using the right hip joint as a case study, we present its corresponding fitting function.

The coefficients are as follows: A0 is -3.079. a0 to a8 are − 0.2911, -1.576, -3.536, 0.2471, 0.794, 0.8891, -0.7193, and 0.5661, respectively. b0 to b8 are − 0.9948, 6.44, 17.61, -5.08, 5.609, 0.4399, 0.3051, and 2.285, respectively. w is 1.651.

The Adjusted R-square method modifies the standard R-square value by incorporating adjustments for sample quantity and the count of independent variables, enhancing the accuracy of the model’s fit30. Research found modified R-squared > 0.99 for all four curves, indicating strong model-data alignment.

Dynamic simulation of intelligent lower limb exoskeleton system

We initialized the system state using the hip and knee joint configurations derived from the fitted function at t = 0 s as the reference starting point. The model was configured with revolute joints at both the hip and knee, while the lumbar segment remained fixed. Under natural gravitational acceleration (g = 9.81 m/s²), we simulated 3 s of dynamic motion and quantitatively analyzed the resulting kinematic variations.(Fig. 20).

ADAMS post-processing analyzed hip and knee moment dynamics, validating the method’s effectiveness (Fig. 21). Peak moments were: left hip 65.724 Nm (avg. 7.292 Nm), right hip 59.583 Nm (avg. 10.430 Nm), left knee 16.377 Nm (avg. 5.362 Nm), right knee 23.259 Nm (avg. 7.104 Nm). Max torques were below motor torque, ensuring sufficient power, with max avg. power P = 13.612 W < motor’s rated power. Peak immediate power outputs of left and right hip joints were 88.177 W and 90.645 W, respectively, aligning with motors’ max power (Fig. 22). Avg. The simulation results are consistent with the peak torque of human joints ranging from 60 to 80 NM, and during walking, the peak power is approximately 60 to 150 W.

Simulation of lower limb exoskeleton control system based on fuzzy PID

Construction of lower limb exoskeleton control simulation system

The lower-limb rehabilitation robot uses a brushless DC (BLDC) motor, comprising three main components: the motor body (stator and rotor), the electronic commutation circuit (logic commutation and position signal units), and position sensors (stator and rotor sensors)31.The system’s equivalent circuit is shown in the Fig. 23.

The mathematical model of the Y-connected brushless DC motor system is represented by its Laplace-transformed transfer function32.

Where:

Ld—Single-phase equivalent inductance,Ld= 2La;

J—Rotor moment of inertia,kgm2;

rd—Equivalent circuit resistance,rd=2R1;

B—Viscous friction coefficient;

KT—Motor torque constant;

Ke—Back electromotive force constant.

The transfer function can be derived from the specific parameters of the brushless motor HT6010-J36.

Tracking experiment of lower limb exoskeleton motion signal based on fuzzy PID

This study employs a seven-level fuzzy set {NB, NM, NS, ZO, PS, PM, PB} to construct a dual-input triple-output fuzzy PID controller based on error E (discretized over [-6,6]) and its rate of change EC. The system utilizes Gaussian membership functions for inputs to achieve rapid response, while adopting triangular membership functions for outputs to ensure regulation precision. Through 49 fuzzy rules, the controller realizes adaptive tuning of PID parameters (Kp, Ki, Kd), with Kp sharing the domain of E, and Ki/Kd linked to EC,As shown in Fig. 24. This hybrid membership function design effectively balances dynamic response speed and steady-state accuracy.

As shown in Fig. 25. Based on the above transfer function, a brushless DC motor system was constructed. The tracking performance of the right hip joint position angle and step signals under fuzzy PID and traditional PID control was compared, as shown in the figure, to evaluate the performance of both control strategies33. The simulated right hip joint position function was incorporated into the simulation model, establishing a comparative simulation platform for fuzzy PID and PID control systems.

As shown in Fig. 26.Both conventional and fuzzy PID controllers achieved a 0.06 s settling time. The conventional PID exhibited ~ 5% overshoot, while the fuzzy PID achieved zero overshoot with negligible steady-state error. Though sharing similar rise times (~ 0.04 s), the fuzzy PID demonstrated smoother dynamics by eliminating initial overshoot.

As shown in Fig. 27 the conventional PID showed ± 5° peak tracking error with 0.05 s phase lag, whereas the fuzzy PID reduced errors to within ± 2° and virtually eliminated lag (< 0.01 s). During rapid transitions (0.8–1.0 s), oscillation amplitudes decreased by > 60%. Results confirm the fuzzy PID’s adaptive tuning enhances nonlinear system precision (60% error reduction) and response (80% lag improvement), proving ideal for high-accuracy motion control.

Simulation experiment of lower extremity exoskeleton motor system

The exoskeleton operating conditions are set for the brushless motor to start and reach a constant speed, with the speed maintained during load increase. A brushless motor control system is built in Simulink, as shown in the Fig. 28. The experiment is set with a rated speed of 50 rpm, and the load is increased from 5 N·m to 10 N·m within 0.04 s.

The results, as shown in the Fig. 29, demonstrate that after fuzzy PID control, the motor torque response is smoother, the speed reaches the rated value faster, and the driving performance is more precise and stable.

Membrane pressure gait sensor system

Structure of membrane pressure gait sensor system

The system utilizes the Gaitboter module from ICC, CAS34 for lower limb gait analysis, incorporating advanced sensor technology (Fig. 30). Core components include thin-film pressure sensors, accelerometers, and gyroscopes34. Eight plantar sensors capture pressure variations, six-axis inertial sensors35track foot speed and angular velocity, and hip and knee sensors collect posture data. MCU and BLE facilitate real-time data reception and processing, ensuring comprehensive gait analysis36.

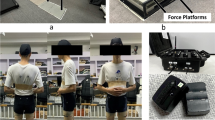

Experimental methods and procedures

To ensure the reliability of gait data, the experiment was conducted in a smooth corridor measuring 12 m in length and 2.2 m in width. Participants included one healthy individual and three patients with lower limb injuries (age 26 ± 5 years, BMI 22.8 ± 1.5) from Peking University Third Hospital. Due to space constraints, the analysis was conducted based on data from one patient.All participants wore standardized plantar pressure shoes and were equipped with 9-axis inertial sensors on their hip/knee joints. Data were processed using a three-dimensional gait analysis system, which synchronously captured dynamic parameters from plantar pressure sensors and pose parameters from joint sensors, ultimately generating a gait database. The database was constructed using extensive clinical experimental data. This study specifically analyzes three representative postoperative patients alongside healthy control subjects, with the experimental results demonstrating gait characteristics typical of normal-stature patients following surgery, thereby ensuring generalizability.

The original clinical data collection protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital. The experimental gait data were sourced from the “Clinical Application of Gait Analysis Technology for Brain Stroke Using Integrated Sound and Motion Sensors” project, with the corresponding ethical approval obtained. Since this study only utilized fully anonymized secondary data without involving new participant interventions, no additional ethical approval was required for the analysis.

Analysis of experimental results

Plantar pressure data analysis

Figure 31 depicts the pressure variation curves within the left and right foot segments of an average individual over 0.8 s during normal walking. In standard walking, the support points are primarily at the heel and toe, with peak pressures denoted as \(\:{P1}_{left}\),\(\:{P2}_{left}\) ,\(\:{P3}_{left}\) and \(\:{P1}_{right}\),\(\:{P2}_{right}\), \(\:{P3}_{right}\)for the left and right heel, mid-foot, and toe, respectively. To evaluate plantar pressure variation, Eq. 10 presents the differential ratio formula for the left foot heel, mid-foot, and toe. Peak pressures for heels, midfeet, and toes are established, and pressure difference weights are computed to assess sole pressure distribution. The auxiliary drive demand is assessed by examining the pressure proportion between left and right foot segments, with a specific formula provided for the left foot heel, midfoot, and toe.

The left-right foot discrepancy is measured as an f-9fraction compared to a standard value spectrum, with deviations indicating stress that may cause pelvic tilt. A flexible moment-drive is applied to the affected hip motor. Figure 31 compares the plantar pressure curves between three patient groups and healthy subjects.

Figure 32 shows irregular plantar pressure fluctuations in the patient, with notable heel-midfoot pressure disparity between left & right feet. Outcomes derived using the formula are presented in Table 3.

Analysis of the data in Table 3 reveals significant abnormalities in the plantar pressure distribution of Patient 1. The differential percentages for the left forefoot (21.7%), midfoot (55.5%), and heel (53.3%) markedly exceed the normal reference values (forefoot: 11.4%; midfoot: 28.6%; heel: 8.5%), while the right midfoot and heel show relatively smaller deviations. This pressure pattern indicates a pronounced bilateral lower-limb load imbalance, with excessive weight-bearing on the left side, suggesting potential left pelvic tilt and compensatory loading on the left limb. Based on these biomechanical characteristics, it is recommended to adjust the lower-limb exoskeleton assistance strategy by enhancing left hip joint torque output and optimizing hip fixation parameters to improve bilateral load distribution.

Hip and knee gait assessment

By utilizing the positional data from the hip/knee sensor, the movement amplitude of the hip/knee joint can be determined in each direction of freedom. To facilitate the analysis, a collection of standard human motion trend data is chosen for comparative purposes, as depicted in Fig. 33.

Analysis of Fig. 33 demonstrates close alignment between measured left/right foot trajectories and reference values, confirming normal gait coordination. Hip extension angles (20° left, 30° right; reference: 40°) showed reduced but physiological ranges, while flexion peaks matched the 40° reference. Knee extension (10° left, 20° right; reference: 30°) exhibited conservative yet functional ranges, with left flexion (60°) matching and right flexion (50°) approaching the reference (60°). These results validate the system’s accuracy in capturing normative gait kinematics within clinically acceptable tolerances. Figure 34 presents hip and knee posture data obtained from a patient at Beijing Third Hospital using the device.

Analysis of Fig. 34 identifies three key gait abnormalities: reduced left hip abduction, elevated right knee valgus, and delayed left knee extension, suggesting gluteal weakness and ligament laxity that compromise stability and load distribution. Corresponding exoskeleton optimizations include: progressive hip abduction assistance for pelvic stability, real-time feedback-controlled valgus damping to prevent overcorrection, and phase-delay compensation algorithms for normalized knee extension timing. These adaptive modifications synchronize with gait cycles to enable precise biomechanical compensation while maintaining na tural movement patterns.

Spatiotemporal parameter analysis of gait

During the Gaitboter study, we collected spatio-temporal walking parameters (Fig. 35). Using these & patient’s lower limb data, joint torsion velocity was recalculated for precise motor speed calibration.

The Jacobi matrix inverse calculates theoretical hip joint velocity from foot velocity, establishing a database. Analysis compares patients’ foot speed to database’s velocity, aiding in fine-tuning drive motor speed.

Conclusion

This paper presents a design methodology for a lower limb exoskeleton targeting rehabilitation of patients with movement disorders. Through systematic investigation of dynamic gait mechanisms in lower extremities, a corresponding mathematical model was established and analyzed to develop an intelligent lightweight exoskeleton. Innovatively integrating human biomechanical models with exoskeleton prototypes through the OpenSim platform enabled precise quantification of assistance effects on lower limb muscle groups. A transfer function was derived based on brushless motor kinematic models, with comparative simulations demonstrating superior trajectory tracking performance of fuzzy PID algorithms over classical PID controllers, as evidenced by torque and rotational speed curves. The system incorporates thin-film pressure gait sensors for real-time data acquisition, enabling active exoskeleton assistance and intelligent functionality. A comprehensive gait motion database was concurrently established to support adaptive rehabilitation strategies. The proposed framework demonstrates significant potential in enhancing assistive device responsiveness and rehabilitation efficacy through systematic electromechanical integration and data-driven control optimization.

Data availability

All data associated with this study are available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/CppHardLearner/lower-Limb-intelligent-Rehabilitation-Robot-codes.git.

References

Dimmick, S., Stevens, K. J., Brazier, D. & Anderson, S. E. Femoroacetabular impingement. Radiologic Clin. 51 (3), 337–352 (2013).

Ganz, R. et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Research®. 417, 112–120 (2003).

Minkara, A. A., Westermann, R. W., Rosneck, J. & Lynch, T. S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after hip arthroscopy in femoroacetabular impingement. Am. J. Sports Med. 47 (2), 488–500 (2019).

Tijjani, I., Kumar, S. & Boukheddimi, M. A survey on design and control of lower extremity exoskeletons for bipedal walking. Appl. Sci. 12 (5), 2395 (2022).

Sankai, Y. Leading edge of cybernics: Robot suit hal. In 2006 SICE-ICASE International Joint Conference P-1. (IEEE, 2006).

Esquenazi, A., Talaty, M., Packel, A. & Saulino, M. The rewalk powered exoskeleton to restore ambulatory function to individuals with thoracic-level motor-complete spinal cord injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91 (11), 911–921 (2012).

Kitatani, R. et al. Reduction in energy expenditure during walking using an automated Stride assistance device in healthy young adults. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95 (11), 2128–2133 (2014).

Seo, K., Lee, J. & Park, Y. J. Autonomous hip exoskeleton saves metabolic cost of walking uphill. In 2017 International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR) 246–251. (IEEE, 2017).

Aliman, N., Ramli, R. & Haris, S. M. Design and development of lower limb exoskeletons: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 95, 102–116 (2017).

Kong, K. & Jeon, D. Design and control of an exoskeleton for the elderly and patients. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 11 (4), 428–432 (2006).

Kim, S. & Bae, J. Development of a lower extremity exoskeleton system for human-robot interaction. In 2014 11th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI) 132–135. (IEEE, 2014).

Hayashi, Y. & Kiguchi, K. A lower-limb power-assist robot with perception-assist. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics 1–6. (IEEE, 2011).

Xia, T. et al. Design and analysis of human lower limb powered exoskeleton. Mach. Tools Hydraulics. 46 (3), 28–32 (2018).

Yang, S. & Kong, L. Research on characteristic extraction of human gait. In 2009 3rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering 1–4. (IEEE, 2009).

Zhang, J., Cai, Y. & Liu, Q. Study on the influence of wearable lower limb exoskeleton on gait characteristics. Sheng Wu Yi Xue gong. Cheng Xue Za zhi = J. Biomedical Eng. = Shengwu Yixue Gongchengxue Zazhi. 36 (5), 785–794 (2019).

Perry, J., Davids, J. R. & S. T. K, & Gait analysis: normal and pathological function. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 12 (6), 815 (1992).

Martini, F. H., Nath, J. L. & Bartholomew, E. F. Fundamentals of Anatomy & Physiology. (Accessed 09 July 2024). https://www.pearson.com/en-us/subject-catalog/p/fundamentals-of-anatomy--physiology/P200000006829?view=educator (Pearson Education, Limited, 2017).

Ai, H. Human Anatomy and Physiology 4–5 (Science Press, 2015).

Lei, Z. Research on Human Lower Limb Powered Exoskeleton Model (Shaanxi University of Science and Technology, 2016).

Wu, G. Structural Analysis and Research of Lower Limb Exoskeleton Based on Biomechanics (Jilin University, 2024).

Cheng, S. & Du, R. Advances in the treatment of motor dysfunction after stroke. Chin. J. Massage Rehabilitation Med. 11 (11), 35–39 (2020).

Delp, S. L., Anderson, F. C., Arnold, A. S., Loan, P., Habib, A., John, C. T., … Thelen,D. G. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 54 (11), 1940–1950. (2007).

Seth, A., Hicks, J. L., Uchida, T. K., Habib, A., Dembia, C. L., Dunne, J. J., … Delp,S. L. OpenSim: Simulating musculoskeletal dynamics and neuromuscular control to study human and animal movement. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14 (7), e1006223. (2018).

Seth, A., Sherman, M., Reinbolt, J. A. & Delp, S. L. OpenSim: a musculoskeletal modeling and simulation framework for in Silico investigations and exchange. Procedia Iutam. 2, 212–232 (2011).

Kainz, H., Graham, D., Edwards, J., Walsh, H. P., Maine, S., Boyd, R. N., … Carty,C. P. Reliability of four models for clinical gait analysis. Gait Posture 54, 325–331. (2017).

Sturdy, J. T., Silverman, A. K. & Pickle, N. T. Automated optimization of residual reduction algorithm parameters in opensim. J. Biomech. 137, 111087 (2022).

Ieshiro, Y. & Itoh, T. Verification of RRA and CMC in OpenSim. In AIP Conference Proceedings 1558 (1), 2155–2158. (American Institute of Physics, 2013).

Zhou, R. Motion Analysis and Simulation of human-robot Coupled Lower Limb Exoskeleton Robot (Lanzhou University of Technology, 2020).

Thelen, D. G., Anderson, F. C. & Delp, S. L. Generating dynamic simulations of movement using computed muscle control. J. Biomech. 36 (3), 321–328 (2003).

Shi, X. F. Research on the Dynamic Performance of Human Lower Limb Exoskeleton Mechanism with Passive Energy Storage (Xi’an University of Technology, 2023).

Guo Wentao, S. et al. &. Fuzzy PID control and modeling simulation of brushless DC motor. Mech. Electr. Eng. Technol. (09),14–18. (2021).

Wang, T. Optimal control methods for robotic arm joint motors, Ph.D. dissertation, Changchun Univ. Technol., Changchun, China. (2023).

Astrie Kusuma Dewi,Muhammad Maura Gomez & Chalidia Nurin Hamdani. PID – fuzzy controller to control system temperature on cooling tower. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1504 (1), 012007–012007. (2025).

Tian, T., Wang, C., Xu, Y., Bai, Y., Wang, J., Long, Z., … Zhou, L. A wearable gait analysis system used in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a case–control study. Diabetes Metab. Syndrome Obesity 14, 1799–1808. (2021).

Wang, Z. & Ji, R. Estimate spatial-temporal parameters of human gait using inertial sensors. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER) 1883–1888. (IEEE, 2015), June.

Wang, C. et al. Estimation of Temporal gait parameters using a wearable microphone-sensor-based system. Sensors 16 (12), 2167 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported in part by General Project of Education of National Social Science Foundation of China and in part by the Research on Educational Robots and Their Teaching System under Grant BIA200191.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and G.Z.; methodology, J.Z. and G.Z.; software, G.Z.; validation, G.Z.,X.J. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, G.Z.; investigation, G.Z. and Y.L.; resources, J.Z. and M.B.; data curation, G.Z.,X.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z., X.J., M.B. and Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, G.Z.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The gait analysis data used in this study were obtained from the Gaitboter system (provided by Beijing Zhongke Huicheng Technology Co., LTD) and PeKing University Third Hospital. All data were fully anonymized prior to analysis, ensuring no identifiable personal information was retained. Since this study did not involve direct interaction with human participants and utilized only pre-existing de-identified data, it does not require ethical approval under applicable regulations (e.g., Declaration of Helsinki or China’s Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research).

Informed consent

All original data collection procedures involving human participants were conducted in compliance with ethical standards, and written informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to data acquisition. However, this secondary analysis did not involve new data collection or individual-level identification, thus falling outside the scope of additional ethical review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Zou, G., Zhao, Q. et al. Lower limb intelligent rehabilitation robot based on human-gait coupling, spatiotemporal gait sensing, and fuzzy PID control. Sci Rep 16, 1926 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31657-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31657-z