Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the commonly lethal malignancies worldwide and represents a major global health-care challenge. We have previously demonstrated that plumbagin (PLB) could inhibit the development of tumor in liver, but the mechanism is still not fully clear. Here we identified a transcription repressor-homeobox containing 1 (HMBOX1) as a regulator in the development of HCC.Knockdown of HMBOX1 resulted into expansive of tumor cells, while overexpression led to growth inhibition. Mechanistically, PLB promoted HMBOX1 expression, leading to inactivation of PI3K/Akt-mTOR of liver cancer cells. Moreover, PLB also inhibited tumor formation in a xenograft transplantation model via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. Collectively, our results suggested that HMBOX1 played a key role in PLB-induced inhibition of HCC growth through PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes the most prevalent type of primary liver malignancy and ranks as the fourth principal source of cancer-associated mortality worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that over one million people will suffer from primary liver cancer by 20301. Despite ongoing advancements in therapeutic approaches, the 5-year survival rate is still unsatisfactory (~ 18%), indicating the poor prognosis of this disease2. Therefore, further elucidation of the molecular mechanism of hepatoma and novel anticancer agents will help to improve the quality of life of those patients.

Plumbagin, a naturally occurring naphthoquinone, is a main component of Chinese herb Plumbago zeylanica L. Recently, plumbagin has been attracted much attention due to its diverse biological activities, such as antiviral and antimicrobial infection, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activities3,4. Nevertheless, the most attractive feature is its ability of anti-tumor. For example, we and others have shown that PLB could inhibit the growth and expansion of various cancer cell both in vitro and in vivo through multifarious regulation, including prostate, melanoma, ovarian, esophageal, colon, promyelocytic leukemia and liver3,4,5,6,7,8,9. However, the molecular mechanism that controls these pleiotropic effects on different cancer cells needs further research independently.

We have demonstrated that PLB could inhibit HCC growth by excessive ROS-mediated DNA damage and modulation of ATM-p53, PI3K/Akt signaling pathway7,8. However, the molecular mechanism is still incompletely clear. Here we used CRISPR/Cas9 system to screen and identify a transcription repressor-homeobox containing 1 (HMBOX1) as a regulator in the development of HCC. Our results showed that PLB upregulated transcriptional and protein level of HMBOX1, leading to HCC growth inhibition via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. This study suggested that HMBOX1 may serve as a therapeutic target for PLB, promoting its potential for clinical application in HCC therapy.

Methods and materials

Reagents and antibodies

Plumbagin (PLB, 5-Hydroxy-2-Methyl-1,4-Naphthoquinone) was purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (#481-42-5, Merck KGaA,, USA).Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was obtained from Servicebio (#G4103,Wuhan, China). Annexin V/PI apoptosis detection kit was provided by Shanghai Pumai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (#9312842,Shanghai, China). High-sugar DMEM (#PYG0131) was provided from Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Crystal violet dye (#G1063), puromycin(#P8230), skim milk(#D8340), and penicillin‒streptomycin solution(#P1400) were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS, #A122063) was procured from Gemini Therapeutics, Inc. (Delaware, USA). The GeCKOv2 library plasmid was obtained from Addgene (#1000000048,Watertown, USA). The BCA protein assay kit was acquired from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Methanol and ethanol were procured from Shanghai LingFeng Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Tween 20, and glycine was procured from Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The HMBOX1 (#16123-1-AP), PI3K (#60225-1-Ig), AKT (#60203-2-Ig), p-AKT (Ser473)(#80455-1-RR), mTOR (#66888-1-Ig), p-mTOR (Ser2448) (#67778-1-Ig), Cleaved Caspase 3(#25128-1-AP) and GAPDH (#60004-1-Ig) antibodies were from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Wuhan, China); and p-PI3K (#4228T) antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Boston, USA); Bcl-2 (#AF0060) and Bax (#AF5120) antibody was from Beyotime Biotech Inc. (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture and treatment

Huh-7 and HCCLM3 cell lines were obtained from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures and cultured as we previously described7,8. Briefly, cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution. Cells were exposed to PLB range from 0 ~ 10 µM. Their activities and colony assays were conducted as we did before7. For apoptosis detection, cells were labeled utilizing Annexin V-FITC and PI. The rate of apoptosis was then quantified via flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter, USA), and the resulting data was further analyzed by CytExpert2.0 software.

Genome-scale Cas9-mediated screening

The Human GeCKOv2 CRISPR Knockout pooled library was used to identify genes responsible for plumbagin treatment in HCC cells.The workflow of this plumbagin screen at Huh-7 cells was shown in Fig. 2A, which is based on Zhang’s study design10,11. First,1 × 108 Huh-7 cells underwent infection with the combined lentiviral GeCKO v2 library, with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) at 0.3. Following a 5-day post-infection, cells were subjected to puromycin selection (1 µg/ml) for 7 days to establish a pool of mutant cells. The modified Huh-7 cells were divided into two groups, one of which were kept in complete medium containing 4 µM plumbagin for 7 days. The other group was cultured in complete medium containing an equivalent amount of DMSO (vehicle). Following the treatment process, a minimum of 3 × 107 cells were harvested for genomic DNA isolation, which was performed with TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (#DP304, TIANGEN, China). The sgRNA sequences underwent amplification utilizing NEB Q5®High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases(#M0493,New England Biolabs, USA), and the generated amplicons were retrieved from 2% agarose gels employing an EasyPure Quick Gel Extraction Kit (#EG101,TransGen Biotech, China). Subsequently, these samples underwent high-throughput amplicon sequencing conducted by Novogene Technology (Beijing, China). The sgRNA enumeration and evaluation were executed utilizing the MAGeCK tool12,13.

Establishment of the HMBOX1 knockout cell line

The sgRNAs targeting HMBOX1 from the GeCKO v2 library were engineered and inserted into the lentiCRISPRv2 vector. The HMBOX1-sgRNAs sequences were GACGAGGGAGTCGATTTACC; TCCCGAATGCTGCGTCTGTG; ACCAGCCCCCATTCCAATAG. The nontargeting sgRNA (NC-sgRNAs) was generated as control (TTATCGCGTAGTGCTGACGT). In brief, Huh-7 cells underwent transduction with the lentiviral CRISPRv2 system harboring sgRNAs directed at HMBOX1 or NC guides. Puromycin (1 µg/ml) was introduced one day post-transduction for 7 days. HMBOX1 protein levels were evaluated via Western blot analysis.

RT-qPCR and western blot

The complete RNA was procured utilizing TRIzol reagent (#9109, TaKaRa, Japan) and then transformed into complementary DNA employing a reverse transcription kit (#RR036A, TaKaRa, Japan). qPCR was performed using the TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (#RR820A, TaKaRa, Japan) with Lightcycler 480II(Roche, Switzerland). Primer sequences:

HMBOX1-forward: 5′-CTTCAGCGACTTCGGCGTA-3′ and HMBOX1-reverse: 5′-ATCATAACTGTTGCTAGGTGACG-3′; GAPDH-forward: 5′-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3′ and GAPDH-reverse: 5′- GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3′. Cellular protein extracts were obtained utilizing RIPA buffer (#P0013C, Beyotime, China).The protein expression was determined by western blotting using anti-PI3K(1:5000), anti-p-PI3K (1:1000), anti-AKT (1:5000), anti-p-AKT (1:5000), anti-mTOR (1:5000), anti-p-mTOR (1:2000), anti-HMBOX1 (1:1000), anti-Bcl-2(1:1000), anti-Bax(1:1000), anti-cleaved caspase 3(1:1000) and anti-GAPDH(1:5000) antibody. Primary antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies ) followed by a Amersham Imager 600 image acquisition system (GE Healthcare, USA).

Xenograft tumor model

BALB/c nu mice (male, 4 ~ 6-week-old, body weights 16 ~ 20 g) were purchased from the Experimental animal Center, Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (EAC-GXTCMU) and maintained in a pathogen-free facility at a controlled temperature (23–25 °C), under a 12 h light and dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. The cage and bedding were changed once a week. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocol approved by Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine Institutional Welfare and Ethical Committee (Approval No. DW20230324-116) and in line with the ARRIVE criteria14. 5 × 106 Huh-7 cells were injected into the left subcutaneous back of nude mice.Six days after the inoculation, mice were randomized into 2 groups (n = 6 per group): control group (0.9% saline) and plumbagin treatment groups(4 mg/kg three per week). For another subcutaneous transplant tumor model, 5 × 106 NC-sgRNA and HMBOX1-sgRNA Huh-7 cells were respectively resuspended in 100 µL of PBS and then injected into the left subcutaneous back of nude mice(n = 12). Six days after the inoculation, the NC-sgRNA tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into 2 groups, NC-sgRNA, NC-sgRNA + plumbagin, with 6 mice in each group.Also, the HMBOX1-sgRNA tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into 2 groups, HMBOX1-sgRNA, HMBOX1-sgRNA + plumbagin groups, with 6 mice in each group.NC-sgRNA + plumbagin and HMBOX1-sgRNA + plumbagin groups mice were intraperitoneally injected with plumbagin at a dose of 4 mg/kg three per week, and the other two groups were injected with the same amount of 0.9% saline. The tumor size and the weight of mice were measured every two days.Tumor volumes were calculated as below: V (cm3) = width2 (cm2) × length (cm)/2. After the nude mice bearing tumors were sacrificed, the xenografts were were removed and weighed.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The tumor specimens were preserved in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. The growths were subsequently encased in paraffin blocks. Tissue slices underwent deparaffinization, rehydration, and were immersed in 0.01 M sodium citrate to facilitate antigen recovery. Inherent peroxidase activity was neutralized. The samples were then exposed to anti-HMBOX1, p-mTOR, p-PI3K, p-AKT, Bax and Ki67 antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The tumor slices were processed with biotinylated secondary antibodies and a streptavidin-biotin complex (Zsbio, Beijing, China). Visualization was achieved utilizing DAB (Boster, Wuhan, China). Representative images were captured utilizing an Olympus device (Nikon Instruments, Melvil). The immunohistochemical pictures were examined using Image-Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) to determine the average optical density (AOD). The outcomes were computed utilizing the subsequent equation: AOD = integrated optical density (IOD)/Area.

Statistical analysis

The findings are displayed as the average ± tandard deviations (SD) from three distinct trials. Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing a two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad). A p-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. *p < 0.05.

Results

PLB inhibited HCC growth in vitro and in vivo

To examine the cytotoxic effects of PLB on HCC cells, we initially evaluated its impacts on cellular viability in Huh-7 and LM3 cell lines. Here we found that PLB inhibited cellular viability in both cell lines in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Moreover, PLB dramatically induced apoptosis in Huh-7 and LM3 cells (Fig. 1B). The western blotting results showed that PLB treatment increases pro-apoptotic-regulated protein (Bax) and apoptotic executionior (cleaved caspase3) protein levels in a dose-dependent manner, while the level of the anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2) was progressively downregulated(Supplementary Figure S1).Next, we evaluated the effects of PLB on cellular colonies in HCC cells. PLB significantly inhibited colony formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Finally, we established a subcutaneous tumor xenograft model using Huh-7 cells. Consistent with the decreased colony formation, PLB treatment markedly decreased the volume and weights of the xenograft tumors (Fig. 1D,E). These results demonstrated that PLB could promote apoptosis in HCC cells and inhibit the growth of HCC cells in vitro and in vivo.

Plumbagin inhibits HCC growth in vitro and in vivo. (A) cellular viability of Huh-7 and LM3 cell lines treated with PLB or not. (B) Flow cytometric analysis for apoptosis in Huh-7 and LM3 cell lines treated with PLB or not. (C) Colony formation assays of Huh-7 and LM3 cells treated with PLB or not. (D) Representative images of tumor formation from control and PLB-treated mice. (E) Analysis of tumor volume and weights in D. Results are presented as means ± SD, n ≥ 3, *P < 0.05.

HMBOX1 was screened as a regulator for HCC growth

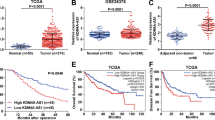

To further explore how PLB controlled HCC growth, we performed genome-wide screening by using a CRISPR/Cas9 knockout library in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 2A). We utilized the Human GeCKO v2 CRISPR library A10, which contains 65,386 distinct sgRNAs targeting 19,052 protein-coding genes and 1864 microRNAs, to establish a pool of mutant cells. Subsequently, the mutant cells were exposed to PLB or DMSO for 7 days, facilitating both positive and negative screening processes. DMSO-treated cells functioned as a control. We postulated that knockout of a PLB-sensitive crucial gene would protect HCC cells from PLB-mediated cell death or growth inhibition. In the context of PLB exposure, cells harboring sgRNA targeting PLB-sensitive genes would undergo positive selection within the mutant cell population. Consequently, their associated sgRNA would experience depletion in the library, a phenomenon detectable through next-generation sequencing techniques. Illumina’s next-generation sequencing was employed to analyze the amplicons. The Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR‒Cas9 Knockout (MAGeCK) algorithm was utilized to detect enriched or depleted gRNAs by comparing the DMSO-treated and PLB-treated samples12,13. The top 10 candidates were identified for enrichment analysis (Fig. 2B). The enrichment analysis identified potential genes whose alterations resulted in PLB resistance, suggesting that these genes may serve a function for HCC sensitivity to PLB.Meanwhile, when analyzing the expression of the top 10 genes in the TCGA database of liver cancer tissues, we noticed that only HMBOX1 is significantly downregulated in HCC tissues collected by TCGA (Supplementary Fig. S2; Fig. 2D). Moreover, HMBOX1 targeting sgRNAs were dramatically increased in plumbagin-treated cells, implying that loss of HMBOX1 might resist HCC cells to plumbagin treatment(Fig. 2C). Additionally, we analyzed the protein level of HMBOX1 between normal people and patients with tumors collected in CPTAC database, and found that HMBOX1 was downregulated in those patients with tumors (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results indicated that HMBOX1 may play an important role in PLB-induced cytotoxicity against cancer cells.

HMBOX1 is shown as a target for PLB-mediated anti-tumor effects by CRISPR screening. (A) Experimental protocol in the high-throughput genetic screenings. (B) Scatter plot showing significant genes in positive selection analysis. (C) Schematic diagram shows targeting sgRNAs against HMBOX1 enriched in PLB-treated cells. (D,E) Box plots illustrating HMBOX1 expression profiles in TCGA hepatic tissues (D) and CPTAC liver cancer (E). Data were statistically analyzed by the ULCAN website.

HMBOX1 mediated the PLB-induced inhibitory effects on Huh-7 cells

To confirm the screening results, we used sgRNAs targeting knockdown of HMBOX1 to detect the effects of PLB on the growth of Huh-7 cell lines. Results from RT-qPCR and Western blotting showed that HMBOX1 was downregulated by sgRNAs (Fig. 3A), leading to higher cellular activities and colonies compared with the negative control (NC) group (Fig. 3B,C). However, overexpression of HMBOX1 resulted in less cellular viability and colonies (Fig. 3D–F).

Regulation of HMBOX1 in Huh-7 cell growth depend on PI3K/Akt/m-TOR pathway. (A) Representative images for immunoblotting and quantitative analysis with targeting silence of HMBOX1 or not. (B,C) Representative images of cellular activities (B), colonies formation and numbers (C) under the condition of knockdown of HMBOX1. (D) Representative images for immunoblotting in presence of overexpression of HMBOX1 or not. (E,F) Representative images of cellular activities (E) and colonies (F) in presence of HMBOX1-overexpression. (G) Representative images for immunoblotting and quantitative analysis for mTOR, Akt, PI3K and their phosphorylation level treated with silence or overexpression of HMBOX1. Data are presented as means ± SD, n ≥ 3, *P<0.05.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade is involved in PLB-induced antitumor activity8, and HMBOX1 had been shown to regulates the growth and metastasis of cancer partly through the PI3K/Akt pathway15. Here we also found that knockdown of HMBOX1 activated PI3K/Akt, wherein overexpression inactivated the pathway (Fig. 3G). Taken together, these results indicated that HMBOX1 have a significant role in the emergence of PLB-induced resistance in Huh-7 cells.

Next, we explored whether HMBOX1 was involved in PLB-induced inhibitory effects on Huh-7 cells. Our immunoblotting results showed that HMBOX1 was increased both in gene and protein level in a dose-depend manner (Fig. 4A,B), leading to inhibitory effects of Huh-7 cell growth. However, transfection with sgRNA against HMBOX1 resulted in higher cell growth (Fig. 4C,D). Moreover, PLB activated PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in a dose-depend manner (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, knockdown of HMBOX1 increased the phosphorylation activities of PI3K/Akt/mTOR cascade kinases (Fig. 4F), which was consistent with the previous description. These data suggested that HMBOX1 regulates tumor growth partly via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and may function as a tumor suppressor in HCC tumor formation.

PLB-induced increase in HMBOX1 inhibits Huh-7 cell growth via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. (A,B) Gene and protein level of HMBOX1 responded to PLB stimulation. (C,D) Representative images of cellular activities (C), colonies formation and numbers (D) in presence with PLB, HMBOX1 knockdown or not. (E) Representative images for immunoblotting and quantitative analysis for mTOR, Akt, PI3K and their phosphorylation level treated with PLB or not. (F) Representative images for immunoblotting and quantitative analysis for HMBOX1, mTOR, Akt, PI3K and their phosphorylation level treated with PLB, and/or HMBOX1-sgRNA or not. Data are presented as means ± SD, n ≥ 3, *P < 0.05 vs. control group or 0µM group, #P < 0.05 vs. PLB group.

Knockdown of HMBOX1 attenuated plumbagin’s anti-HCC effects in vivo

To assess the role of HMBOX1 in PLB-induced anti-tumor activities in vivo, NC-sgRNA or HMBOX1-sgRNA Huh-7 cells were transplanted into BALB/c nu mice to induce subcutaneous tumor xenograft model. Once tumors developed, the NC-sgRNA tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into 2 groups (6 mice pre group) : control group and PLB treatment group. The HMBOX1-sgRNA tumor-bearing nude mice were also grouped in the same way. In accordance with previous in vitro results, knockdown of HBMOX1 by sgRNA increased the tumor size compared with NC group, while concurrent treatment with PLB significantly decreased the tumor size (Fig. 5A–C). No changes in body weight were detected in all groups (Fig. 5D). Notably, only PLB injection showed the greatest inhibitory effects of tumor formation. In addition, PLB treatment markedly diminished the levels of Ki-67, p-mTOR, p-PI3K and p-AKT, while increasing the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax. Conversely, knockdown of HMBOX1 restored the levels of p-mTOR, p-PI3K, and p-AKT, and reduced Bax expression, as visualized by IHC staining (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these findings indicated that HMBOX1 was involved in the PLB-induced suppression of hepatoma tumor growth through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway.

Knockdown of HMBOX1 aggravates tumorigenesis in vivo via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. (A) Representative images of tumors from Huh-7 xenograft mice pretreated with PLB and/or HMBOX1-sgRNA alone or combined. n = 6 in each group. (B–D) Representative images of tumor volume (B), weight (C), and body weight(D) in the indicated group. (E) IHC analysis of Ki67, HMBOX1, p-mTOR, p-PI3K, p-AKT and Bax in HCC tumor tissues. The expression levels of target proteins were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software to calculate the average optical density. Scale bars: 50 μm. Results are presented as means ± SD, *P < 0.05 vs. control group, #P < 0.05 vs. PLB group.

Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the most common cancers worldwide and still represents a major global health-care challenge16. We have demonstrated that PLB could inhibit HCC growth via inactivation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR8, but the regulatory factors upstream of this pathway are still of mystery. In this work, we employed a whole-genome CRISPR/Cas9 knockout library to screen genes that participate in PLB induced anti-cancer effects and identified the transcription factor HMBOX1 as an important regulator for HCC growth. We showed that HMBOX1 deficiency activated mTOR/PI3K/Akt signaling, whereas its overexpression inhibited HCC growth. These results indicated that PLB’s impact on the mTOR/PI3K/Akt pathway was dependent on HMBOX1.

CRISPR/Cas9 library gene editing technology was utilized to discover new targets and reveal potential mechanisms under various diseases and designated treatment conditions17,18,19. To identify the potential mechanisms of PLB in HCC, we used the GeCKO v2 screening library strategy for screening as previously described10,20,21 and validated the effect of HMBOX1 in PLB treatment by sgRNAs. HMBOX1 is a novel transcription repressor featuring with an atypical homologous domain at its N-terminus, sharing homology with hepatocyte nuclear Factor 1 (HNF1)22,23. Many homologous domain proteins are transcription factors that play important roles in embryogenesis and tumorigenesis. Researches have demonstrated that HMBOX1 decreased in invasive tumors and cancer cells than in normal tissues and cells, and knockdown of HMBOX1 promoted tumor expansion in ovarian cancer and osteosarcoma, indicating that HMBOX1 may act as a tumor suppressor15,24. Additionally, Zhao et al. demonstrated that HMBOX1-knockout mice exhibit exacerbated liver injury25, suggesting that HMBOX1 may also play key roles in liver diseases. Here we found that HMBOX1 was downregulated in HCC tissues collected by TCGA and knocking-down HMBOX1 expression enhanced Huh-7 cell proliferation. However, both PLB-induced and overexpressed HMBOX1 promoted apoptosis of Huh-7 cells, while knockdown of HMBOX1 attenuated the anticancer effects of PLB, confirming the important roles of HMBOX1 in PLB-induced HCC growth inhibition. Moreover, Zhou et al. suggested that downregulation of HMBOX1was strongly associated with cervical cancer cell radiosensitivity26. Accordingly, it is reasonable that HMBOX1 is essential for PLB-mediated therapeutic benefits in liver cancer.

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling serves as the primary intracellular signaling route involved in modulating cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, metabolism, and angiogenesis through interactions with pertinent upstream and downstream molecules, and it exhibits dysregulation in numerous cancer types27,28. This pathway is overexpressed in nearly 50% of HCC, and its abnormal activation affects a wide range of biological processes, leading to tumorigenesis and progression. Therefore, blocking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is considered as a potential strategy for tumor treatment. In this study, we observed that PLB increased HMBOX1 expression and decreased phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR in HCC cells, which was consistent with our another research29. Collectively, it is likely that PLB inhibits HCC growth through HMBOX1-mediated inactivation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. However, further researches are required to uncover the elaborate mechanism of HMBOX1 and to facilitate its clinical application in liver cancer.

Conclusion

Our research pinpointed HMBOX1 as a crucial gene linked to PLB toxicity in HCC through the use of genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 library screening, potentially offering a significant reference for utilizing natural compounds as anticancer agents. Plumbagin inhibits the development of HCC in vivo and in vitro by enhancing HMBOX1 expression and thus negatively regulate the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. This investigation revealed the important role of HMBOX1 in PLB’s anti-cancer effects for the first time and shed lights on the significance of this transcription regulator for PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway regulation. A limitation of this study is the need for other HCC cell lines to further validate this mechanism.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Alawyia, B. & Constantinou, C. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a narrative review on current knowledge and future prospects. Curr. Treat. Opt. Oncol. 24 (7), 711–724 (2023).

Vogel, A., Meyer, T., Sapisochin, G., Salem, R. & Saborowski, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 400 (10360), 1345–1362 (2022).

Xu, Z. et al. Research hotspots and trends of plumbagin: A bibliometric perspective. Med. (Baltim). 104 (9), e41726 (2025).

Panda, S. S. & Biswal, B. K. The phytochemical plumbagin: mechanism behind its pleiotropic nature and potential as an anticancer treatment. Arch. Toxicol. 98 (11), 3585–3601 (2024).

Roy, A. Plumbagin: A potential anti-cancer compound. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 21 (6), 731–737 (2021).

Yin, Z. et al. Anticancer effects and mechanisms of action of plumbagin: review of research advances. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 6940953 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Plumbagin exhibits genotoxicity and induces G2/M cell cycle arrest via ROS-mediated oxidative stress and activation of ATM-p53 signaling pathway in hepatocellular cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(7) (2023).

Wei, Y. et al. Computational and in vitro analysis of plumbagin’s molecular mechanism for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 594833 (2021).

Wang, B., Kong, W., Lv, L. & Wang, Z. Plumbagin induces ferroptosis in colon cancer cells by regulating p53-related SLC7A11 expression. Heliyon 10 (7), e28364 (2024).

Shalem, O. et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 343 (6166), 84–87 (2014).

Sanjana, N. E., Shalem, O. & Zhang, F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods. 11 (8), 783–784 (2014).

Li, W. et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 15 (12), 554 (2014).

Fang, P., De Souza, C., Minn, K. & Chien, J. Genome-scale CRISPR knockout screen identifies TIGAR as a modifier of PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Commun. Biol. 2, 335 (2019).

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D. G. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 1 (2), 94–99 (2010).

Chen, S. et al. WTAP promotes osteosarcoma tumorigenesis by repressing HMBOX1 expression in an m(6)A-dependent manner. Cell. Death Dis. 11 (8), 659 (2020).

Rumgay, H. et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 77 (6), 1598–1606 (2022).

Wang, T., Wei, J. J., Sabatini, D. M. & Lander, E. S. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science 343 (6166), 80–84 (2014).

Chen, X. et al. The application of CRISPR/Cas9-based genome-wide screening to disease research. Mol. Cell. Probes. 79, 102004 (2025).

Ali, A. et al. From gene editing to tumor eradication: the CRISPR revolution in cancer therapy. Prog Biophys. Mol. Biol. 196, 114–131 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Genome-scale CRISPR screening for potential targets of ginsenoside compound K. Cell. Death Dis. 11 (1), 39 (2020).

Wan, T. R. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies NFkappaB and c-MET as druggable targets to sensitize lenvatinib treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19 (7), 101502 (2025).

Dai, J. et al. Recombinant expression of a novel human transcriptional repressor HMBOX1 and Preparation of anti-HMBOX1 monoclonal antibody. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 6 (4), 261–268 (2009).

Holland, P. W., Booth, H. A. & Bruford, E. A. Classification and nomenclature of all human homeobox genes. BMC Biol. 5, 47 (2007).

Yu, Y. L. et al. Low expression level of HMBOX1 in high-grade serous ovarian cancer accelerates cell proliferation by inhibiting cell apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 501 (2), 380–386 (2018).

Zhao, H. et al. HMBOX1 in hepatocytes attenuates LPS/D-GalN-induced liver injury by inhibiting macrophage infiltration and activation. Mol. Immunol. 101, 303–311 (2018).

Zhou, S. et al. Knockdown of homeobox containing 1 increases the radiosensitivity of cervical cancer cells through telomere shortening. Oncol. Rep. 38 (1), 515–521 (2017).

Tian, L. Y., Smit, D. J. & Jucker, M. The role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(3) (2023).

Peng, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, C., Mei, W. & Zeng, C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its role in cancer therapeutics: are we making headway? Front. Oncol. 12, 819128 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Plumbagin induces autophagy and apoptosis of SMMC-7721 cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 (6), 9820–9830 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi (2023GXNSFBA026081,2019GXNSFDA245003,2024JJA140721), the third batch of “Qihuang Project” high-level talent team cultivation project of Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (202402),the Research Launching Fund Project from Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine Introduced the Doctoral in 2020 (2020BS027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W.: Methodology, validation, writing—original draft, funding acquisition; T.C.: Data curation and, methodology, validation; H.L., Y.M.: Data curation and, validation; H.L.: Visualization, writing—original draft, funding acquisition; Y.D.: Validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; S.D.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocol approved by Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine Institutional Welfare and Ethical Committee (Approval No. DW20230324-116).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Y., Cheng, T., Liu, H. et al. HMBOX1 plays a critical role in plumbagin-induced growth inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci Rep 16, 3909 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33875-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33875-x