Abstract

Individuals with left-hemisphere damage (LHD), right-hemisphere damage (RHD), dementia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and healthy controls are characterized by overlapping clinical profiles affecting communication and social interaction. Language provides a rich, non-invasive window into neurological health, yet objective and scalable methods to automatically differentiate between conditions with are lacking. This method aims to develop comprehensive neurolinguistic measures of these conditions, develop a machine learning multiclass screening and language assessment model (NeuroScreen) and offer a large comparative database of measures for other studies to build upon. We combined one of the largest databases, comprising 291 linguistic biomarkers calculated from speech samples produced by 1,394 participants: 536 individuals with aphasia secondary to LHD, 193 individuals with dementia, 107 individuals with MCI, 38 individuals with RHD, 58 individuals with TBI, and 498 Healthy Controls. Employing natural language processing (NLP) via the Open Brain AI platform (http://openbrainai.com), we extracted multiple linguistic features from the speech samples, including readability, lexical richness, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics. A Deep Neural Network architecture (DNN) classifies these conditions from linguistic features with high accuracy (up to 91%). A linear mixed-effects model approach was employed to determine the biomarkers of the neurological conditions, revealing distinct, quantitative neurolinguistic properties: LHD and TBI show widespread deficits in syntax and phonology; MCI is characterized by fine-grained simplification; patients with dementia present with specific lexico-semantic impairments; and RHD shows the most preserved profile. Ultimately, the outcomes provide an automatic detection and classification model of key neurological conditions affecting language, along with a novel set of validated neurological markers for facilitating differential diagnosis, remote monitoring, and personalized neurological care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Language is a distinctively human cognitive system that enables individuals to communicate, share information, and socialize. It includes a complex interplay of spoken, written, and signed modalities, drawing on multiple linguistic subsystems, including phonology (the sound structure of words), morphology (the internal structure of words), syntax (rules governing sentence structure), semantics (meaning), and pragmatics (the social use of language)1,2. Even simple tasks, such as ordering a meal, rely on the integration of these linguistic processes. Language is not only central to social participation but is also tightly linked to broader cognitive functions, including memory, attention, and executive functioning3,4. Consequently, when language is disrupted due to neurological conditions such as left hemisphere damage (LHD), right hemisphere damage (LHD), dementia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or traumatic brain injury (TBI), the consequences extend beyond isolated cognitive deficits to independence, social participation, and overall quality of life. Yet, despite the critical role of language in human functioning, assessing and monitoring language functioning in clinical practice and properly treating it remains challenging.

The distinct underlying pathologies of LHD, RHD, dementia, MCI, and TBI produce unique behavioral profiles by differentially affecting receptive and expressive language5,6 (Table 1). These can serve as early linguistic markers that characterize these patients7. Neurological research has shown that LHD primarily impacts language and other cognitive functions8,9,10. RHD can impair spatial awareness, emotions, and nonverbal and pragmatic communication11,12,13,14,15. Both LHD and RHD can language deficits, but the specific nature of these deficits differs16,17,18,19. MCI, an early cognitive decline, is typically amnestic in nature (affecting memory), but also typically impacts language and other critical cognitive domains, such as attention, and executive functions20,21,22,23,24,25. Dementia is a progressive deterioration of the brain health due to neurodegeneration, affecting multiple cognitive domains, such as memory, language, attention, and movement26,27,28. TBI is a heterogeneous disorder, resulting in open or closed head trauma by an external force, such as a blow to the head, a fall, a car accident, and a penetrating injury. It can range from mild (e.g., concussion) to severe, with varying degrees of physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral effects29.

Conventional language assessment tools

Conventional language assessment tools, including structured tasks (e.g., Philadelphia Naming Test30, Boston Naming Test31, standardized batteries Western aphasia battery (revised) (WAB-R)32, Quick Aphasia Battery (QAB)33 and the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE)34, and patient- and clinician-rated evaluations35,36,37, are widely used to support diagnosis and guide treatment decisions. These methods often provide a narrow window into specific abilities like object naming, overlooking the multidimensional nature of everyday communication. Furthermore, their time-intensive and stressful nature makes them ill-suited for widespread screening. Clinicians may instead use general neurocognitive screeners like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)38,39,40, but these still require in-person assessment and may not be sensitive enough to detect subtle language impairments characteristic of conditions like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This creates a critical challenge for early detection and prognosis. A powerful solution lies in combining large-scale language corpora with computational methods such as Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Machine Learning (ML). This approach can enable automated screening and provide a deeper, comparative understanding of these conditions against each other and normative data from healthy individuals.

We address a critical limitation in neurolinguistics—the tendency to study conditions in isolation—by creating a unified analytical framework. Analyzing connected speech and discourse—how individuals use language in natural, extended communication—is widely regarded by researchers and clinicians as a best practice for assessing language abilities41. This approach captures real-world communicative competence and can reveal subtle linguistic deficits that standardized, isolated tasks often overlook. However, despite its advantages, discourse analysis remains underused in clinical practice due to its time-intensive nature, lack of scalable and standardized tools, and the manual effort required for transcription and coding42. Moreover, traditional assessments are typically conducted in controlled clinical environments, which may not reflect an individual’s everyday communication patterns, thereby limiting ecological validity. Consequently, subtle or early-stage language impairments—especially those associated with heterogeneous conditions such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early dementia—often go undetected until more pronounced cognitive or functional decline is evident.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), NLP, ML, and automated speech analysis have opened new possibilities for addressing these limitations. By leveraging AI-driven approaches to extract and quantify linguistic features from spontaneous speech, we and others have demonstrated their potential for objective, reproducible, and ecologically valid measures of language production from transcripts or audio files21,43,44,45. These computational methods can quantify automatically domains of language disorder—spanning lexical diversity46, phonological structure47,48, morphological patterns9,10,49,50,51,52, syntactic complexity53,54,55,56,57, semantic content, and readability58,59,60,61—represent a promising class of digital biomarkers with the potential to support early detection45,62,63, differential diagnosis21,43,64,65,66, and ongoing monitoring of neurological conditions67,68,69. Despite that these studies demonstrates that automated language analysis holds significant promise as a digital health tool, several challenges must be addressed before it can be fully integrated into clinical practice.

Automated language analysis is progressively recognized as a digital health tool70,71, yet its clinical translation is constrained by several critical gaps. For these computational tools to improve patient outcomes in a meaningful way, they must first move beyond the current landscape of proof-of-concept studies, which often use small, homogenous datasets from isolated clinical populations but rely on rigorous validation across large, diverse, and multi-condition populations is essential. This validation must also establish robust normative data from healthy controls, enabling clinicians to benchmark an individual’s performance to accurately assess pathology and severity. Also, the development of sophisticated computational pipelines must be paired with a focus on practical application: creating scalable, automated, and openly accessible tools that can integrate seamlessly into clinical workflows to reduce clinician burden and enhance diagnostic precision. Addressing these interconnected challenges is the essential next step toward realizing language as a clinically actionable digital biomarker.

Study aims

This study has an overarching aim to advance a novel paradigm for neurological assessment to corroborate existing neurological assessments and to establish spoken language as a scalable and clinical digital biomarker by evaluate a comprehensive set of measures from the key linguistic domains, readability, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and lexicon (Supplementary Data 1 offers a detailed description see also the Methods section).

This provides a two-fold aim. The first aim is to develop a multi-class machine learning approach for neurological screening (NeuroScreen) that can discriminate patients from Healthy Controls (HCs) and the subtype individual patient subgroups from each other. Ultimately, the MLs aim to answer two primary research questions (1) How well do the models distinguish patients and healthy controls? And (2) How well does the ML model distinguish each sub-group in the data? By answering these two questions, we will be able to determine how well the models can be employed in real-life scenarios for detecting patients and in the clinic to subtype patients, and which of them with high confidence. To achieve aim we have developed an end-to-end AI-driven procedure to analyze a large and diverse database of over 9,900 speech samples based on an end-to-end ML model that combines NLP pipelines that employ Open Brain AI61, a platform we have developed to extract the linguistic features. Subsequently, we preprocessed and standardized the calculated measures and passed them to a set of ML models, namely Random Forrest, Support Vector Machine, Logistic Regression, and Deep Neural Networks. These models were tuned through hyperparameter tuning and evaluated.

(2) The second aim is to provide explainable measures, namely the linguistic signatures of five major neurological conditions (LHD, RHD, dementia, MCI, and TBI). This is critical to understanding the effects of each condition on language and to providing therapeutic targets for novel clinical approaches. In other words, we will determine (1) Which linguistic measures differ most due to diagnostic groups? (2) Which are the distinctive features for each neurological condition compared to HC? And (3) What do language measures reveal for each patient group? To achieve this aim, we developed (generalized) linear mixed effect models while controlling for the effects of task and the participant.

This computational approach moves beyond prior research by leveraging ecologically valid data from everyday communicative tasks to create a comprehensive, multi-faceted portrait of how language changes in response to brain injury and disease, aiding in differential diagnosis, particularly for disorders with overlapping symptoms like MCI and early dementia, and offering a non-invasive, low burden means for monitoring disease progression and treatment response over time. Ultimately, this research contributes to the digital transformation of clinical practice by providing a validated set of open-access linguistic biomarkers, this study creates new opportunities for remote, low-burden monitoring of neurological health, supporting a future of more accessible, data-driven, and personalized care.

Methodology

Participants

The individuals for this study were drawn from Neural Databank collected and developed by the second author72, now part of the Aphasia Bank, and data from the TalkBank consortium (https://talkbank.org), which following a similar protocol. Each clinical bank (e.g., AphasiaBank, RHDBank) has an established discourse protocol that elicits a variety of discourse genres73.

-

(i)

Aphasia Bank: The database contains spoken discourse samples from individuals with LHD and control participants, designed to study language production and its neural foundations. The research emphasizes connected speech (discourse) rather than single words or isolated sentences. Participants completed a full discourse protocol twice within a short timeframe to assess the test–retest reliability and stability of discourse measures. The participants contain both people with LHD (536 individuals) and HCs (359 individuals)72.

-

(ii)

Right Hemisphere Damage Bank (RHD Bank): This is a specialized database focused on communication in individuals with RHD. The database serves as a resource for understanding and treating communication disorders following RHD, particularly focusing on pragmatic language abilities, discourse coherence, and real-world communication challenges74. This bank includes 38 individuals with RHD and 40 Healthy Controls.

-

(iii)

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI Bank): This is a multimedia database focused on studying communication disorders in individuals with TBI. TBIBank protocol includes discourse tasks such as the Cinderella story retell, following similar methodology to other TalkBank databases. The protocol consists of discourse genres including personal narratives, picture descriptions, story retelling, and procedural discourse. TBIBank is a longitudinal study in which brain injured people are videoed at 6 different time points post injury performing a uniform set of tasks, with the goal of identifying recovery patterns. The database enables automated language analysis, diagnostic profiling, comparative evaluation of treatment effects, and profiling of recovery patterns in TBI populations, supporting both research and clinical applications in understanding cognitive-communication disorders following brain injury. This bank includes 58 individuals with TBI.

-

(iv)

Dementia Bank—Delaware MCI dataset: This corpus is part of DementiaBank and includes language productions by 71 adults with MCI, from the Delaware Corpus and Baycrest Centre Corpus. This data contributes to early detection of subtle changes in language and cognition and provide insight into MCI subtypes based on discourse profiles75. The MCI Delaware corpus contains mostly individuals with amnestic MCI, were the language-variant should not be predominant. However, they have language differences from HCs66.

-

(v)

Dementia Bank—Pitt Study (Pitt Study): A comprehensive description of this dataset is provided in Becker, Boiler76.Briefly, the study includes a picture description task from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination77, a widely used diagnostic tool for detecting language abnormalities. In this task, participants were shown the “Cookie Theft” picture stimulus and instructed to describe everything they observed. Their responses were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. This study includes 193 individuals with Dementia and 99 Healthy Controls.

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of linguistic measures across various diagnostic groups by combining data from multiple discourse tasks (see Supplementary Data 1). Our primary analysis provides a consolidated overview of these linguistic features (Table 2; Supplementary Data 2, provides a more comprehensive data breakdown of Data Count by Group, Project, and Task). Recognizing that different tasks may elicit distinct communication patterns, we have preemptively accounted for potential task-specific effects within our statistical models by adding the task in the random effects. To ensure full transparency and to allow for a more granular examination of these variations, we provide a detailed breakdown of the linguistic signatures for each task in the Supplementary Tables.

Participants participated in different tasks providing often more than one samples, the analysis is based on 9955 language samples drawn from multiple clinical databases produced by the individuals reported in Table 3 (see also, Table 2 and Supplementary Data 2). These databases exhibit significant clinical heterogeneity. For instance, the LHD database contains participant groups classified by subtype, including anomic, Wernicke’s, and Broca’s aphasia. The Pitt study’s dementia subgroup (N = 193) further illustrates this diversity; it is composed primarily of patients with dementia (91%), who present with lower average Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of 17–18, alongside individuals with MCI. We chose to incorporate these databases in their entirety for several reasons. This approach maintains the ecological validity of the data, ensuring our findings reflect the natural heterogeneity of clinical populations. Furthermore, it preserves the integrity of these standard corpora, which is crucial for the reproducibility and comparability of our results within the wider research community.

Measures

Texts were automatically preprocessed using a python algorithm to remove TalkBank’s Computerized Language Analysis CHAT/CLAN coding, labels, and tags (e.g., prosodic markers, time-aligned tiers with annotations, CHAT metadata) and prepare clean texts for further analysis. Subsequently, the text samples were analyzed using Open Brain AI (http://openbrainai.com; Fig. 1), a custom clinical linguistics platform developed by the first author61 to facilitate automatic audio and linguistic analysis of texts. Unlike generic computational models, Open Brain AI was designed specifically for phenotyping of language features through a clinical lens, enabling hypothesis-driven research into speech pathology and neurogenic communication disorders. The platform calculates linguistic metrics in real-time as participants type or as clinicians transcribe speech samples, enabling immediate quantitative analysis of discourse features relevant to neurological conditions. Additional analysis modules accessible via the toolbar include syntactic complexity measures, semantic density calculations, and comparative normative data. This example demonstrates the platform’s capability to automatically extract objective linguistic measures from naturalistic discourse samples, facilitating evidence-based assessment of communication disorders across various neurological populations. Open Brain AI executed a cascade of NLP techniques. Core NLP steps included tokenization (segmenting text into individual words or tokens), part-of-speech tagging (assigning a grammatical category to each token), and dependency parsing (identifying the grammatical relationships between words and the syntactic structure of sentences). For each extracted feature, both raw counts and ratios (to normalize for variations in text length) are computed. These quantitative linguistic data were automatically exported by our computational platform as spreadsheet files, ready for statistical analysis (Fig. 2).

User interface of the Open Brain AI text analysis platform61 for neuropsychological assessment. The web-based platform provides real-time linguistic analysis of narrative discourse samples. The interface displays a text editor (top panel) containing a participant’s narrative description of the “Cat Rescue” picture stimulus, commonly used in aphasia and cognitive assessment batteries. The lower panel shows automated lexical measures including character count (643), word count (161), sentence count (17), and function word analysis (93 total function words, ratio 0.578).

NeuroScreen machine learning pipeline architecture for automated neurological assessment. The comprehensive workflow shows the development and validation of a diagnostic system that analyzes language production to distinguish between neurological conditions. Input data comprises speech and text samples from participants across six diagnostic groups: Left Hemisphere Damage (LHD), Right Hemisphere Damage (RHD), Dementia, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), and Healthy Controls. Language production tasks undergo automated linguistic feature extraction across six domains: Lexicon (vocabulary richness), Phonology (speech sound patterns), Morphology (word formation), Syntax (grammatical structure), Semantics (meaning content), and Readability (text complexity). The preprocessing pipeline includes quality control checks, speaker leakage detection, correlated feature removal, mean imputation for missing values, z-score standardization, and principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction (retaining 95% variance). Five machine learning algorithms are systematically evaluated: Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Gradient Boosting (GB), and Deep Neural Network (DNN). Model optimization employs hyperparameter tuning with GroupKFold cross-validation and randomized/halving grid search. Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) addresses class imbalance. The validated models comprise the NeuroScreen diagnostic tool for objective, automated neurological assessment based on quantitative linguistic analysis.

From these foundational analyses, a comprehensive suite of linguistic measures was automatically extracted, quantifying aspects of (Supplementary Data 1 offers a detailed list of the measures):

-

(i)

Readability. Readability of text productions in patients with neurological conditions is a measure that has been evaluated for the first time concerning all these conditions in this study. Metrics assessing text complexity and perceived ease of understanding for a reader. Readability metrics include the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Tests, Gunning Fog Index, and SMOG Index58,59,60,61 quantify how easy a text can be to be read and understood by a reader. It is typically influenced by factors such as sentence length, word complexity, and the overall structure of the text. Overall, we expect that patient speech should be simpler and more readable than that of healthy individuals.

-

(ii)

Lexicon and Lexical Information. We have designed features related to the vocabulary richness, diversity, and usage within the text. This includes measures like Type-Token Ratio, counts of content versus function words, and average word length. These measures explain the distribution of words and relationships between types and tokens that can quantify how words are used in different contexts and how they contribute to the overall meaning of a text such as lexical diversity measures46.

-

(iii)

Phonology. Characteristics of sound structure, such as counts of words by syllable Number: (e.g., one-syllable, two-syllable words) and the distribution of various Consonant (C) and Vowel (V) syllable structures (e.g., CV, CVC, CCVC). We designed these measures to quantify how users employ speech sounds, the sound combinations, and the complexity of syllables. Comparing these measures across patients with different language impairments can reveal characteristics that pertain to the effects of impairment on the cognitive representation of sounds and speech production47,48.

-

(i)

Morphology. Analysis of word structure, encompassing both the distribution of parts of speech (e.g., counts and ratios of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and inflectional categories (e.g., tense, Number: Gender: case). Morphological measures quantify the structure and form of words, the distribution of parts of speech, and inflectional categories, such as tense, Number, Gender, and Case. Comparing patients with morphology impairments can reveal pathologies, like agrammatism and anomia9,10,49,50,51,52.

-

(ii)

Syntax. Measures of sentence structure and grammatical complexity. This included quantification of various phrase types (e.g., Noun Phrases, Verb Phrases, Prepositional Phrases), analysis of core syntactic dependencies and relations (e.g., nominal subjects, direct objects, adverbial clause modifiers), and overall sentence complexity metrics (e.g., Average Sentence Length, T-units, and syntactic tree depth/Yngve load). These measures quantify impairments of sentence structure (e.g., subject-verb-object order), grammatical rules (e.g., agreement between subject and verb), and phrase structure (e.g., noun phrases, verb phrases)53,54,55,56,57.

-

(iii)

Semantics. Primarily focused on Named Entity Recognition (NER), which involves identifying and categorizing named entities in text into predefined classes such as persons, organizations, locations, dates, and quantities.

These grammatical analyses utilized the Universal Dependencies framework for standardized annotation78 and custom made metrics, which were systematically selected using both established measures based on established theoretical frameworks in clinical linguistics and their demonstrated sensitivity to pathological language changes in neurogenic communication disorders (like counts of nouns and verbs) and novel measures that aim to encompass microstructural elements (phonology, morphology), macrostructural components (syntax, semantics), and pragmatic dimensions.

Thus, these measures aim to provide a comprehensive characterization of language impairments that aligns with current models of linguistic breakdown in clinical populations. By capturing this full spectrum of linguistic variation, the analysis framework enables detection of subtle but clinically significant changes that might be overlooked by assessments targeting only isolated linguistic domains. A complete list of all measures and their detailed operational definitions is provided in Supplementary Data 1. Given this large feature set, the analyses presented in this paper prioritize a subset of measures selected for their demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing between the diagnostic groups (LHD, Dementia, MCI, RHS, TBI) and Healthy Controls, as well as differentiating the clinical groups from one another. An exhaustive output of all statistical results for every measure is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Visualizing linguistic performance across diagnostic groups

To explore patterns in linguistic performance across diagnostic groups, we conducted an unsupervised dimensionality reduction analysis. We standardized all linguistic variables (mean = 0, SD = 1) to ensure equal weighting. We applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA)79 to identify the main axes of variation in the data and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)80,81 to generate a nonlinear, two-dimensional embedding that preserves local similarities. UMAP was configured with n neighbors = 15 and min dist = 0.1, and both methods used a random seed for reproducibility. To enhance interpretability, extreme outliers (beyond 1.5 × IQR in the reduced dimensions) were excluded from visualizations (retaining 8,927 and 9,791 participants for PCA and UMAP, respectively). The resulting embeddings were colored by clinical diagnosis to assess the degree of separation or overlap among groups.

Machine learning pipelines

We designed a machine learning pipeline to classify a speaker’s diagnosis into one of six categories based on statistical features derived from language productions on tasks, namely patient with LHD, RHD, dementia, MCI, TBI, and HCs. The pipeline is designed to manage speaker-dependent data, address class imbalance, and a provide comprehensive, comparative evaluation of multiple machine learning (ML) models, namely include Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression, Gradient Boosting, and a Deep Neural Network (DNN). The entire process, from data preparation to model evaluation, was conducted in a Python environment utilizing pandas for data manipulation82, scikit-learn83 and imbalanced-learn84 for machine learning algorithms. The deep learning component was build using Tensorflow85.

Data preparation and cohort definition

The core of our methodology is built upon the principle of speaker-independent validation, which is crucial for developing models that can generalize to new, unseen individuals rather than memorizing characteristics of specific speakers in the training set. To facilitate this, a designated speaker identifier column was used to group data points belonging to the same individual. The dataset was then partitioned into features and the target variable.

To ensure that the model evaluation provides a realistic estimate of performance on new individuals, a strict speaker-independent splitting protocol was enforced. The dataset was divided randomly into a training set (80%) and a hold-out test set (20%) using the GroupShuffleSplit strategy. This method guarantees that all data points from any given speaker are confined to only one of the sets (either training or testing), completely preventing data leakage between them. This approach is critical for assessing the model’s ability to generalize beyond the specific speakers it was trained on.

Preprocessing and feature engineering pipeline

A multi-step preprocessing pipeline was applied sequentially to the data. Crucially, all preprocessing steps were fitted only on the training data to prevent information from the test set from influencing the training process. The same fitted transformers were then used to transform both the training and test sets.

-

(i)

Missing values in the feature set were managed by imputing them with the mean of their respective columns, calculated from the training data.

-

(ii)

To reduce multicollinearity and model complexity, highly correlated features were removed. A Pearson correlation matrix was computed on the training set, and for any pair of features with a correlation coefficient and we evaluated various threshold features, for correlations greater than 0.90, one of the features was discarded.

-

(iii)

The features were standardized by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance using the StandardScaler83. This transformation ensures that features with larger scales do not disproportionately influence model training, which is particularly important for distance-based algorithms like SVM and regularization models like Logistic Regression.

-

(iv)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed as the final feature engineering step. PCA transforms the standardized features into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components. The number of components was chosen to retain 95% of the original variance in the training data, effectively reducing noise and the dimensionality of the feature space while preserving most of the relevant information.

Model training, imbalance handling, and hyperparameter optimization

We have evaluated five distinct classification models to explore a range of algorithmic approaches: Logistic Regression (LG), Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM) with an RBF kernel, Gradient Boosting, and a feedforward Deep Neural Network (DNN). We selected these models to allow for a comprehensive analysis of the dataset and selection of a model that explain the data. More specifically, the following models were selected:

-

1.

LG is a fundamental linear classification algorithm. It works by fitting a linear equation to the features and then applying a logistic function (or sigmoid function) to the output to return a probability between 0 and 1. This probability is then used to predict the class. LG serves as a baseline model86.

-

2.

RFs is an ensemble learning method; it constructs many individual decision trees during training. It can capture complex, non-linear relationships in the data without requiring explicit transformations. It is generally robust to overfitting, especially when compared to a single decision tree as it averages the predictions of many trees87.

-

3.

SVM models detect the optimal hyperplane (or decision boundary) that best separates the classes in the feature space. SVM can model both linear and non-linear boundary by mapping the data into a higher-dimensional space, with good generalization performance on unseen data88.

-

4.

GB is another powerful ensemble technique like the RFs, which builds models sequentially. It starts with a simple model and then iteratively adds new decision trees that are specifically trained to correct the errors made by the previous ones. RFs, however, build trees independently and in parallel whereas GBs are sequential with an error-correcting approach leading to more powerful and flexible model86.

-

5.

DNN consists of an input layer, multiple “hidden” layers of interconnected nodes (neurons), and an output layer. The network learns to detect complex patterns and features by adjusting the connection weights between neurons during training. The DNN approach can uncover patterns in the data than the other, more traditional machine learning models might miss89.

The data exhibited an imbalanced class distribution as there are fewer patients with MCI, RHD, and TBI, than patients with dementia, LHD, and HC. To mitigate the risk of models becoming biased towards the majority class, we integrated the SMOTE directly into our modeling pipeline90. For each model, a pipeline was constructed with SMOTE as the initial step. This approach ensures that over-sampling is performed correctly within each cross-validation fold: SMOTE is fitted and applied only to the training data partition of a fold, generating synthetic samples for the minority classes before the classifier is trained. The validation partition of the fold remains in its original, imbalanced state, providing an unbiased evaluation of the model’s performance. This in-pipeline application of SMOTE is crucial for preventing data leakage and obtaining a reliable estimate of model generalizability. We defined a custom DynamicSMOTE class to automatically adjust the k neighbors parameter, preventing errors in cross-validation folds where a minority class had very few samples.

To identify the optimal set of hyperparameters for each model, we employed a hybrid search strategy using a participant-aware data partitioning with GroupKFold cross-validation (with 5 folds) to maintain speaker independence. For the traditional models (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM, Gradient Boosting), we used HalvingRandomSearchCV. This efficient method starts by evaluating many hyperparameter combinations on a small subset of the data and iteratively prunes fewer promising candidates, allocating more resources to the best-performing ones.

For the computationally intensive Deep Neural Network (DNN), we used RandomizedSearchCV to sample a fixed number of hyperparameter combinations from the search space. The performance of each combination was evaluated based on its default scoring metric. The best hyperparameters for SMOTE’s k neighbors parameter were also determined during this search. The DNN architecture was also part of the hyperparameter search. Key parameters tuned included the number of hidden layers, the number of neurons, the dropout rate, batch size, and the learning rate for the Adam optimizer. An “early stopping callback” was used to prevent overfitting by halting training when performance on the loss function stopped improving.

Model evaluation

After hyperparameter tuning, the best-performing version of each model was evaluated on the completely unseen hold-out test set. Model performance was assessed using a comprehensive set of metrics to provide a holistic view of their classification capabilities:

-

1.

Accuracy is the percentage of predictions that were correct out of all predictions made. If your model correctly predicts 85 out of 100 cases, your accuracy is 85%.

-

2.

Balanced Accuracy solves this problem by averaging the accuracy within each class. It calculates the recall (true positive rate) for each class separately, then takes the average. In other words, the balanced accuracy is defined as the average of sensitivity (true-positive rate) and specificity (true-negative rate) for the two classes in a binary classification “Patient vs. Healthy Control (HC)”, the Specificity (HC Recall) (1) and the Sensitivity (Patient Recall) (2) is calculated. Then the Balanced Accuracy is the sum of the Specificity and Sensitivity divided by two (2), the number of classes in a binary classification.

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\text{Specificity}} = \frac{{\text{number of true HCs correctly predicted as HC}}}{{\text{Total number of HCs}}}} \\ \end{array}$$(1)$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\text{Sensitivity / Recall}} = \frac{{\text{number of patient samples (any subtype) predicted as patient}}}{{\text{Total number of patient samples}}}} \\ \end{array}$$(2) -

3.

F1-Score (Weighted) addresses the trade-off between recall (2) and precision (3). The F1-score is the harmonic mean of these two, giving you a single number that balances both concerns. The weighted version calculates F1-scores for each class and then averages them based on how many samples each class has, making it appropriate for imbalanced datasets.

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {Precision = \frac{True Positives}{{True Positives + False Positives}} = \frac{actual positives among all predicted ones}{{predicted positives}}} \\ \end{array}$$(3) -

4.

Cohen’s Kappa measures how much better your model performs compared to random chance. It is particularly valuable because it accounts for the possibility that some correct predictions might just be lucky guesses. Kappa values range from − 1 to 1: 1.0: Perfect agreement beyond chance and 0.0: Agreement is no better than random chance; Negative values mean worse than random chance.

-

5.

AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve). The ROC curve plots your model’s true positive rate against its false positive rate across all possible classification thresholds. The AUC-ROC tells you how well your model can distinguish between classes. AUC = 1.0: Perfect classifier.

-

6.

AUC-PR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve). ROC curves can often be optimistic on imbalanced datasets, precision-recall curves focus specifically on the positive class performance. This makes AUC-PR especially valuable when you care more about correctly identifying the minority class. The PR curve plots precision against recall at different thresholds. AUC-PR is particularly informative for imbalanced data.

-

7.

Confusion matrices were generated for each model to visualize the distribution of correct and incorrect predictions across the different classes. For tree-based models (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting), feature importance scores were calculated and visualized to provide insights into the most influential principal components for classification. Finally, the best overall model, along with the fitted preprocessing transformers, was saved for potential future deployment.

Statistics

To assess the influence of clinical diagnosis on each linguistic outcome variable, we utilized an automated mixed-effects modeling pipeline. This analysis included participants from the five diagnostic groups (LHD, Dementia, MCI, RHS, TBI) and the Healthy Control (HC) group. The pipeline, developed in R91 was designed to be flexible, data-driven, and robust to violations of statistical assumptions common in linguistic data.

For each linguistic variable, a mixed-effects model was implemented. Diagnosis was specified as a fixed effect to determine its influence on the outcome.

As discussed earlier there is variation in the subgroups within the participants and the tasks they perform, to appropriately account for the non-independence of data arising from the study design, and given the complexity of the databases, two random intercepts were included in the model:

-

1.

The (1 | Speaker) term addresses that multiple observations (i.e., linguistic measures from one or more tasks) originate from the same individual. By including a random intercept for each speaker, the model accounts for individual-specific baseline differences in linguistic performance, thereby modeling the repeated measures dimension of the data.

-

2.

The (1 | Task) term addresses the inherent variability across different elicitation tasks (e.g., “Cinderella,” “Flood,” and “Cookie Theft,” as listed in Table 1). Given that the study design involved diverse groups of participants undertaking varying subsets of these tasks, this random intercept allows the model to estimate an average deviation from the overall mean for each specific task. This effectively controls for baseline differences in how tasks might elicit certain linguistic features, regardless of the speaker or their diagnosis.

These random effects structure is robust to the unbalanced nature of task administration (i.e., not all participants completed all tasks, and tasks were not fully crossed with participants). It allows for the estimation of the fixed effect of ‘Diagnosis’ while simultaneously partitioning out variance attributable to individual speakers and specific tasks. The general model structure was:

The analytical pipeline systematically selected the most appropriate statistical model based on the distribution of each dependent variable. This adaptive process involved fitting Gaussian Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMMs) for continuous variables, using robust LMMs if residual diagnostics (via the DHARMa package92) indicated violations of model assumptions, and employing Generalized Linear Mixed-Effects Models (GLMMs) with appropriate distributions (e.g., binomial, Poisson, or negative binomial) for binary or count data, including checks for overdispersion and zero-inflation. If a suitable model could not be fitted through these steps, a rank-based LMM was applied as a robust fallback. (Further details on the specific model selection criteria and R packages, such as lmerTest93 and robustlmm94.

When a significant main effect of ‘Diagnosis’ was found (typically p < 0.05), post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted between all diagnostic groups using estimated marginal means (via the emmeans package95). Tukey’s method was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. Group means and confidence intervals are reported to aid in the interpretation of these differences.

To create a ranked list of linguistic signatures, a key statistic from the post-hoc analysis of your mixed-effects models. A larger z-ratio indicates a more robust and statistically significant difference. It simultaneously accounts for the size of the difference and the precision of the measurement. We use the absolute value of the z-ratio for ranking because we are interested in the magnitude of the difference, regardless of whether a feature’s value increased or decreased. This allows us to directly compare the most impactful features across all groups. The direction of the change (increase or decrease) is then indicated separately in the table with arrows.

Results

We examined the distinct linguistic production of each group on a comprehensive set of linguistic automated measures spanning lexical, morphological, phonological, readability, semantic, and syntactic domains. Figure 3 shows a UMAP plot illustrating the distribution of linguistic profiles across six clinical groups. (It uses all data, that is before dimensionality reduction.) Centroids (marked with 'x') separate HCs, patients with LHD, Dementia, from the three other conditions (that is, patients with TBI, RHD, and MCI), which show significant overlap indicating that individual language abilities vary widely within each diagnosis and often resemble those of other three diagnostic categories. To study the linguistic differences of the diagnostic groups in detail, we conducted a supervised ML analysis and designed regression mixed effect models.

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) visualization of linguistic profiles across diagnostic groups. This plot represents the non-linear dimensionality reduction of linguistic features extracted from speech samples (covering syntax, morphology, phonology, semantics, lexicon, and readability). (A) The axes (UMAP1 and UMAP2) are dimensionless coordinates derived to preserve the local neighborhood structure of the high-dimensional data; absolute values are arbitrary, but proximity between points indicates similarity in the overall linguistic phenotype. (B) Colored points represent individual participants. The 'X' markers indicate the centroid (geometric mean) for each diagnostic group, and shaded ellipses illustrate the general distribution. (C) The spatial separation of Left Hemisphere Damage (LHD) and Dementia from Healthy Controls (HC) reflects their distinct and severe linguistic deficits (e.g., syntactic simplification and lexical retrieval issues). Conversely, the significant overlap of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Right Hemisphere Damage (RHD), and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) with the HC cluster indicates that these conditions manifest with subtler linguistic deviations and higher individual variability, often preserving core structural language elements. (Trustworthiness: 0.868).

Two-stage hierarchical classification system for distinguishing neurological patients from healthy controls and subsequent patient subgroup classification. The flowchart illustrates a binary decision tree where test samples are first classified as either patient or healthy control (HC), followed by multi-class classification of patient samples into specific neurological conditions. The first stage achieves high performance with F1 scores of 96% for patient detection. Patients are subsequently classified into Left Hemisphere Damage (LHD, F1 = 96%), Dementia (F1 = 86%), or Other Neurological Conditions including Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), and Right Hemisphere Damage (RHD) (F1 = 82%).

To investigate the global structure of linguistic variations across diagnostic groups, we performed a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis80,81. Figure 3 displays the two-dimensional embedding of the comprehensive linguistic profiles (derived from the extracted linguistic features) for all participants. Interpretation of the UMAP Projection Unlike linear projections (e.g., PCA), the axes in Fig. 3 (UMAP 1 and UMAP 2) do not correspond to specific, single linguistic variables. Instead, they represent non-linear, dimensionless coordinates that preserve the local neighborhood structure of the high-dimensional data. Consequently, the proximity between data points indicates the similarity of their overall linguistic profiles: points clustered closely together represent individuals with highly similar speech patterns across the domains of morphology, syntax, lexicon, and phonology. The ‘X’ markers indicate the centroids (geometric centers) of each diagnostic group, illustrating the average location of that group’s linguistic profile in the projected space.

The distribution observed in Fig. 3 is a direct result of the feature selection process, where we retained robust, non-redundant measures across all linguistic levels. This multidimensional approach reveals three primary patterns of distribution. Firstly, the distinct clusters in LHD and Dementia show that the LHD group forms a distinct cluster significantly separated from the HCx. This separation aligns with the severe deficits in syntax and phonology (e.g., reduced complex syllable structures and functional words) identified in our statistical analysis. Similarly, the Dementia group separates from HCs, driven by their specific lexico-semantic impairments.

In contrast, the TBI, MCI, and RHD groups show substantial overlap with each other and the HC group. This visual overlap suggests that while these conditions have unique linguistic markers (as detailed in Table 6), their overall linguistic footprint is less distinct than that of LHD. The wide dispersion of the LHD and TBI clouds relative to the tighter HC cluster illustrates the high variance in these populations—reflecting that brain injury affects language production in heterogeneous ways depending on severity and lesion location. This unsupervised visualization serves as a validation of the supervised ML results presented in subsequent sections, confirming that while LHD and Dementia present strong, separable signals, conditions like MCI and RHD present subtler linguistic deviations that require the high-dimensional discrimination provided by the NeuroScreen models.

How well do the models distinguish patients and healthy controls?

To assess how well the models distinguish patients and HCs, we have collapsed all five patient subtypes into one “Patient” group, and we can compute the results shown in Table 4. The plethora of available data for this classification enabled the models to perform exceptional well. LR is essentially perfect at flagging “Patient” vs. “HC” (balanced accuracy ≈ 99%). The DNN and the SVM both perform close to 95% thresholds; the RF and the GB (were close to 90%). Taking the best ML models into account (LR, DNN, and SVM), two main findings are important. First, all the ML models distinguish patients and HCs; second, the linguistic measures used by the ML models distinguish the groups, so they can function as linguistic markers. Although these are multi-class rather than pure HC vs. Patient, their reported AUC-ROC and AUC-PR reflect overall separability.

How well does the ML model distinguish each sub-group in the data?

Above we collapsed all patients into one group, to determine howe well the model identifies patients from HCs. In this section, we discuss the performance of the models as multiclass classifiers, to determine how well the model distinguishes each group from each individual subgroup.

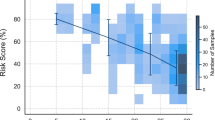

When examining the classifier’s performance on all categories, all models demonstrate robust performance with scores predominantly above 0.8 across most metrics (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 4). For the detection of patients with LHD, all models excel here (F1 ≥ 0.92), with SVM slightly edging out the others (0.96) thanks to near-perfect precision (0.94) and recall (0.99). For patients with dementia LR is most balanced (F1 = 0.88), combining good precision (0.83) with high recall (0.94). The DNN overcalls patients (precision 0.61) despite high recall (0.98), yielding a lower F1. The detection of the HC within the LR again leads (F1 = 0.98), misclassifying only ~ 2% of controls, while the tree‐based models lag (GB 0.85, RF 0.81). For the MCI, SVM outperformed the other models (F1 = 0.60) by balancing 0.63 precision with 0.56 recall. The detection of minority classes was poor, namely patients with RHD (DNN, F = 0.56 and low precision 0.17) comes at poor and TBI (SVM, F1 = 0.58, combining 0.71 precision with 0.50 recall). These suggests either both the need for more data or that language markers are overlapping so that the models are not discriminating these groups well. This will become evident from the following statistical analysis of markers associated with each condition in the following sections.

To address the problem of the minority classes, we collapsed the patient categories with MCI, RHD, and TBI into a category “Other Neurological Conditions”. In this way, the model has an exceptionally good performance, allowing the detection of patients with Dementia, LHD, and HCs and all the minority classes together. In this case, the model-specific performance across all categories. SVM demonstrates consistent performance with balanced precision and recall across LHD (precision: 0.94, recall: 0.99), Dementia (precision: 0.89, recall: 0.83), HC (precision: 0.94, recall: 0.93), and Other neurological conditions (precision: 0.94, recall: 0.72). In contrast, DNN exhibits perfect precision for LHD (1.00) but shows high recall sensitivity for Dementia (0.98) and Other Neurological conditions (0.93) at the cost of reduced precision (0.61 and 0.59, respectively). Support values indicate the sample sizes for each category: LHD (n = 1173), HC (n = 573), Other (n = 211), and Dementia (n = 47), with Dementia representing the smallest patient subgroup.

Which linguistic measures differ most due to diagnostic groups?

Healthy Controls (HC) served as the intercept, and the estimates for each diagnostic group (LHD, Dementia, MCI, RHD, TBI) represent the difference from this HC baseline. The analysis of various linguistic measures reveals that the diagnosis has a statistically significant and often substantial impact across a wide array of speech and language characteristics provides the top features with the largest explanatory power related to neurological condition. The complete results are shown in Appendix 2.

The strength of this impact, however, varies considerably among measures, as indicated by Partial Eta Squared (Partial η2) values for the Diagnosis and the Marginal R-squared (R2 Marginal) for the overall fixed effects of the models is shown in Table 5. All p-values for the reported F-statistics are extremely small (e.g., p < 0.001), indicating high statistical significance for the effect of Diagnosis on these measures. Note that from the presentation below we have removed measures with extremely high Partial η2 values but very low denominator degrees of freedom, suggesting their large effect sizes in this sample should be interpreted with caution due to potential model instability or low power for the inferential test despite the large point estimate of effect, also removed were measures with non-significant effects of diagnosis.

Diagnosis demonstrates a widespread influence on a multitude of linguistic measures. The strongest differentiating features (those with large Partial η2 values and robust model fits) are concentrated in areas of semantic content (especially numerical and definiteness marking), overall lexical production and diversity, counts of various morphological categories (nouns, adjectives, plurals), and basic phonological/syllable structure counts. Additionally, measures of syntactic complexity and certain readability characteristics also show substantial impact.

These findings highlight that the neurological conditions under study manifest with distinct and quantifiable linguistic profiles. The identified measures with the largest effect sizes are prime candidates for inclusion in diagnostic models or for tracking linguistic changes associated with these conditions. The high R2 Marginal values for many of these top-ranking measures further underscore the explanatory power of Diagnosis in accounting for the observed linguistic variations. A substantial number of linguistic measures demonstrated large and robust effects of Diagnosis, indicating these are strong candidates for differentiating between the groups. These involve all the aspects of grammar like phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics, lexical usage, and readability that is text difficulty.

Measures with medium effects (partial η 2 ~ 0.06–0.13)

Beyond the large effects, a broad range of other measures showed medium-sized effects of Diagnosis. These span across all linguistic domains, which we included like the total Number of Function Words (Partial η2 = 0.14), phonology, such as the different syllable types, like VC and CCVCC (Partial η2 = 0.14), morphology including the Number of Verbs (Partial η2 = 0.14), syntax like the number of Complex thematic units (T units), the number of matrix sentences (Root), dependent clauses, and the object of preposition. As discussed below although the readability measures did not make it to the list shown in Table 5, several readability measures remain important as they achieve a Partial η2 between 0.14 and 0.13; these include the Estimated Reading Time (sec), Smog Index, Total Classical Yngve Load, Difficult Words; the latter is a measure based on a standardized dictionary61.

Which are the distinctive features for each neurological condition compared to HC?

In this section, we summarize the high-level “linguistic signatures” that distinguish each group. Table 6 below synthesizes the results for each neurological condition, by highlighting the top ten (10) linguistic features that most strongly distinguish it from Healthy Controls by using the magnitude of the z scores from the post-hoc analysis (emmeans). The complete list of distinctive linguistic features is provided in the Supplementary Table 5.

Several key patterns emerge from the statistical analysis. Individuals with LHD are characterized by a widespread disruption across multiple linguistic domains. While the most discriminating feature is an increased ratio of verb-modifying word types, the majority of the top-10 features are decreases (↓), reflecting a reduction in phonological complexity (e.g., 5 syllables word, CCVCCC), syntactic structures (Complement of preposition ), and the use of specific word types (Pronoun Type: Relative Pronouns). Individuals with Dementia show a pattern of impairment that is also broad but appears centered on the use of specific content and function words (Verb Type: Modal) and a decrease relative to HCs on measures of phonological complexity (5 syllables word, CCVCCC). Individuals with TBI present a mixed profile of mostly decreases in its top features, suggesting a unique pattern of linguistic disruption with a notable increases in of ratio of Modal Verbs. Individuals with MCI is uniquely distinguished by a strong decrease in measures that associated with increased production complexity like five (5) syllable-words, syllables with complex articulatory patterns (CCVCCC, CCCV) and complex syntactic patterns such as the number of Clausal Modifier of Nouns and Complement of Prepositions. This pattern of decreased production in several of the top-ranking features supports the hypothesis that individuals with MCI more general disruptions in language and domains like memory that can explain their use of simpler patterns. Individuals with RHD shows the most subtle linguistic profile. Its top discriminators are related to the diminished production of the number Comparative Adjectives, Complements of Prepositions and complex syllable patterns (CCVCCC) and phonological structures (5 syllable-words).

A comprehensive list of all statistical comparisons for every measure, is showing in Supplementary Data 6 and the primary linguistic signatures based on measures that resulted in statistical significance are reported in Supplementary Table 9.

Discussion

Language is an extraordinarily complex a distributed network, interfacing with human faculties and cognitive processes such as memory, attention, executive functions, and emotions96,97,98. Damage in brain areas responsible for language or areas affecting these cognitive systems is intrinsically reflected in an individual’s language99. An impaired cognitive function is often the earliest indication of neurological conditions, like mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia, or can designate another acquired damage like left (LHD) and right hemisphere damage (RHD), and traumatic brain injury (TBI) and can manifest as a subtle or severe change in linguistic expression, lexical choice, syntactic structure, acoustic properties, and discourse coherence. This makes speech and language a uniquely rich, non-invasive, and continuously available source of medical information, offering a veritable window into an individual’s brain health and cognitive status. The potential to harness this data for diagnostic and prognostic purposes is immense. Traditional approaches are time-consuming, require controlled clinical settings, and can be stressful to the patients. These drawbacks of traditional methods can be addressed by the recent advancements in Machine Learning (ML) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), demonstrating remarkable capabilities in pattern recognition, data analysis, and predictive modeling. In our previous research, we have already shown that ML techniques can enhance the diagnostic accuracy for neurodegenerative disorders by identifying complex patterns in clinical and neuroimaging data that often elude conventional analytical approaches21,43,44,45. Additionally, this underscores the methodological capacity of AI algorithms to manage and interpret intricate medical data, a capability directly transferable to the complexities of speech. In this study, we employed NLP, ML, and robust statistical approach to extract relevant linguistic information and detect signatures for text productions of patients in a variety of discoursal tasks. That resulted into an analysis of 292 linguistic measures from distinct language domains.

Language discriminates diverse neurological conditions: neuroscreen

Having a high-performing, end-to-end model is critical for its real-world usefulness in a clinical setting. The excellent performance metrics demonstrate that this system is not just a theoretical exercise but a potentially powerful diagnostic tool. The model’s ability to distinguish between patients and healthy controls with up to 99% accuracy is its most crucial feature. This near-perfect performance means the system can function as a reliable screening tool for early detection and characterization of neurological conditions. The model excels at identifying common and distinct conditions like LHD with a 96% F1 score and Dementia with an 88% F1 score. This provides a strong basis as a useful tool in the clinic to advice the diagnostic process. Since the model had difficulty with less linguistically distinct conditions (like MCI, RHD, and TBI), we had grouped them into “Other Neurological Conditions” category. This approach provides a more realistic clinical pipeline, namely first an early diagnosis is being performed to distinguish this group from HCs, then we distinguish patients with dementia and patients that require further specialized neurological examination. In this way the NeuroScreen flags these patients for more specialized expert review at the linguistic level yet, it does not get at propositional, macrostructural, or pragmatic levels, required for find grained distinctions especially between TBI, RHD, and MCI where these conditions are known to differ more readily from HCs. Therefore, while NeuroScreen excels in distinguishing patients from HCs, its diagnostic precision on subtyping between patient groups is not overstated, being a complementary to, not a substitute for, gold-standard assessments (e.g., WAB-R, BDAE).

Clinicians can trust the model to accurately flag individuals who need further evaluation, minimizing the chances of missing a patient with a neurological condition. It automates the initial assessment, saving valuable time for specialists and allowing healthcare systems to screen more people, more quickly. Beyond simply identifying a patient, the model’s strength lies in its ability to differentiate between specific neurological conditions. Knowing which condition a person has is essential for providing the right treatment. In essence, this two-stage, end-to-end performance creates a complete and practical workflow. It reliably filters the general population and then provides a highly accurate differential diagnosis for common conditions while intelligently triaging more complex cases. This makes the system on of the most powerful and scalable tool for clinical decision support21,43,45,62,63,64,65,67,68,69.

The reasons are twofold, we rely on a large dataset and on the large number of computational measures that we have develop and provide within Open Brain AI61 covering a wide range of language domains spanning from textual readability58,59,60,61, Lexicon and Lexical Information46, Phonology47,48, Morphology9,10,49,50,51,52, Syntax53,54,55,56,57, and Semantics. Finaly, this approach demonstrates the importance of these metrics to function as linguistic signatures indicating that symptoms associated with neurological conditions can both facilitate diagnosis and function as therapeutic targets. The characteristics of these language signatures and their patterns are discussed next.

Overall language characteristics

The findings revealed condition-specific distinct patterns of linguistic impairments. The most significant differences were observed in individuals with LH stroke and dementia, TBI, MCI, and finally RHD, which showed the most preserved language.

Concerning the lexical markers and the vocabulary usage, we found that individuals with LHD and TBI showed significant reductions in the number of words produced and lexical diversity. Patients with dementia also exhibited reduced word production and diversity, though to a lesser extent while patients with MCI and RHD lexical profile was closer to that of HCs. Concerning the phonological measurements, such as key syllable patterns and syllable complexity, patients with LHD, TBI, and dementia groups produced fewer words of varying syllable lengths and less complex syllable structures. Patients with RHD produced similar phonological patterns to HCs.

In addition to the lexicon and phonology, key morphological measures that involve both the distribution of part of speech (POS) production and inflectional morphology presented key differences among group in the distribution of these measures100,101,102,103. Patients with LHD and TBI demonstrated widespread reductions in the use of most word classes, including determiners, adjectives, nouns, and verbs. Patients with dementia also showed a decline in the use of several word classes whereas patients with RHD showed relatively minor differences compared to HCs.

In line with earlier findings104,105,106, syntactic complexity was significantly reduced in individuals with LHD and TBI, who produced shorter and structurally simpler sentences. Patients with dementia also showed notable reductions in syntactic complexity. The MCI group presented mostly reductions of the core syntactic measures whereas patients with RHD provided fewer distinct patterns compared to HCs.

The statistical models about the readability of the text, a novel measure that we employed in this study, reveal several important insights about the language production in the patient groups. Individuals with LHD, TBI, and dementia was generally rated as less complex and easier to read by various readability indices. Patients with LHD, TBI, and dementia groups used fewer named entities like cardinal numbers and dates.

Overall patterns across diagnostic groups

In many clinical contexts, gross differential diagnosis (e.g., stroke vs. neurodegenerative dementia) is often straightforward based on history, imaging, and basic cognitive screening, yet this study tested whether language can serve as a scalable signal to augment established workflows—not only for early screening before individuals reach a specialist, but also for tracking disease progression, monitoring treatment response, and stratifying risk in already-diagnosed populations. This broader potential is critical because many people with cognitive change are never flagged by family, resist specialist visits, face economic or logistical barriers, or live far from tertiary care. Language is produced ubiquitously in daily life and can be captured passively and non-invasively, enabling remote and longitudinal monitoring. With advances in transcription and automatic speech recognition (ASR) embedded in common digital platforms, language-based analytics could help identify individuals with subjective cognitive complaints who are at elevated risk for mild cognitive impairment or dementia, but also characterize evolving disease trajectories, detect meaningful within-person change, and support clinical decision-making over time. This study demonstrates that language can augment detection, monitoring, and management across the continuum of disease—extending cognitive assessment into primary care, telehealth, and other settings beyond specialized neurology clinics. Therefore, these signatures not only aid differential diagnosis but also stratify patients for targeted intervention, aligning with precision medicine approaches in neurorehabilitation. Table 7 associates these linguistic signatures to therapeutic targets, showing their clinical pertinence.

Expectedly, individuals with LHD consistently demonstrated the most extensive and pronounced differences from HCs across nearly all linguistic categories as detailed in the results section. The majority of these were characterized by significantly lower scores (negative estimates), particularly in measures of lexical production and diversity, morphological complexity, phonological output, and syntactic complexity. These findings corroborate our existing understanding about the grammatical difficulties107, reduced lexical diversity46, and impaired phonological output108, but at the same time they offer a broader understanding, given the extensive coverage our measures provide of the language domain and the systematic integration of features spanning the entire linguistic hierarchy—from phonological structures to discourse-level semantics. Unlike traditional clinical assessments that typically focus on isolated linguistic domains (e.g., naming tests for semantics, sentence repetition for syntax), whereas this approach captures the complex interplay between linguistic levels that characterizes real-world communication.

Importantly, the results highlight previously underappreciated compensatory strategies, such as increased reliance on proper nouns, socially salient references (e.g., persons, organizations), and syntactic simplification through appositional and compound modifiers. This suggests that individuals with LHD are not merely producing less language but may be restructuring their output (whether consciously or unconsciously) to maximize communicative success within their impaired linguistic system. Furthermore, the readability metrics provide novel, ecologically relevant evidence that the language produced by individuals with LHD is objectively simpler and more accessible, supporting the interpretation that both deficits and adaptations co-occur in spontaneous language use.

Individuals with TBI also exhibited a broad range of significant differences from HCs, which lies upon with prior evidence that has also found reductions in linguistic output (e.g., total words, content words, unique words), complexity (e.g., Corrected TTR), and various syntactic counts109,110,111. In several measures, the magnitude of these differences was comparable to or, in some specific instances, even exceeded those seen in dementia. At the same time, the TBI group displayed increased lexical diversity and preserved, or even compensatory, use of certain morphological and syntactic features, indicating strategic adaptations rather than uniform linguistic degradation. The semantic profile of TBI also revealed selective vulnerabilities, particularly in numerical and personal references, suggesting domain-specific disruptions in meaning construction rather than global semantic impairment. Importantly, the readability metrics demonstrate that language produced by individuals with TBI is objectively simplified, mirroring patterns seen in aphasia and underscoring the functional consequences of these linguistic changes for everyday communication. Together, these results contribute novel, objective evidence that TBI disrupts language in ways that are both overlapping with and distinct from classical aphasia profiles.

The global cognitive impairment is a hallmark of dementia, this study emphasizes this by demonstrating that spontaneous language production in this group is relatively preserved across many core linguistic domains, particularly in phonology, syntax, and overall lexical productivity (this is the case in amnestic dementia, but not necessarily in primary progressive aphasia, which is not a syndrome studied here). However, subtle but meaningful disruptions emerged in specific areas which echo prior findings, notably reduced lexical diversity112, simplified word choice (e.g., shorter average word length), and decreased use of complex syntactic and semantic structures113,114,115. The readability findings further underscore this pattern, showing a moderate shift toward simpler, more accessible language that likely reflects both cognitive decline and simplification strategies. While the pattern was generally one of decreased scores compared to HCs, the effects were often less pronounced and less uniformly distributed across measures compared to the LHD group, reflecting high variation in this group113,114,115.

Unlike LHD aphasia or TBI, MCI was characterized by a subtler but systematic pattern of linguistic simplification, which has been shown previously, particularly evident in reduced lexical productivity, decreased syntactic complexity, and phonological impairments116,117,118. The findings reveal that even at this early disease stage, individuals with MCI produced fewer total words, content words, and unique word types, accompanied by reductions in sentence length and the use of complex syntactic structures such as dependent clauses and prepositional phrases. Interestingly, lexical diversity (standard TTR) was increased compared to HCs, reflecting a compensatory pattern where speakers produce fewer words overall but rely on a more varied vocabulary within their reduced output. Readability metrics further indicated that MCI speakers produce objectively simpler, more accessible language than HCs, likely reflecting both cognitive constraints and emerging compensatory strategies.

These results provide new, quantitative evidence reinforcing and extending long-standing but often inconsistently documented observations that language production following RHD is relatively preserved in terms of core linguistic structure, but may still exhibit subtle disruptions, particularly in semantic, pragmatic, and higher-order discourse features. The present analyses reveal that individuals with RHD performed comparably to healthy controls across most lexical, phonological, morphological, syntactic, and readability measures, supporting prior research showing that RHD does not typically produce the overt language breakdown observed in left hemisphere stroke or TBI. However, the detection of reduced use of specific structures, such as comparative adjectives, complex syllable patterns, and second-person pronouns, along with a selective reduction in certain semantic categories (e.g., cardinal numbers), highlights that RHD may subtly affect aspects of language tied to complexity, perspective-taking, or relational meaning. These findings align with previous evidence that while RHD does not result in classical aphasia, it can impact elements of discourse organization, inferencing, and pragmatic language, often in ways that evade detection by standard language batteries.

A key insight from these findings is that while language simplification emerges as a common consequence of neurological damage, the specific linguistic signature varies systematically across disorders, reflecting both the nature of the underlying neural disruption and the ways in which language production shifts in response to these deficits. Across conditions such as LHD, TBI, MCI, and dementia, individuals consistently produced simpler language characterized by reduced lexical output, diminished syntactic complexity, and lower readability. Yet, the precise linguistic domains affected, and the nature of these changes differed. For example, individuals with MCI and TBI showed increased lexical diversity within reduced output, while LHD and dementia speakers exhibited greater reliance on proper nouns and socially salient references. These patterns suggest that language production does not decline uniformly but instead reflects a combination of impairment and adaptive linguistic shifts, whether conscious or automatic. Even in the context of cognitive or neural decline, measurable alterations in language use indicate preserved linguistic capacity and potential compensatory processes. Capturing both these deficits and adaptations provides a more complete and clinically informative picture of how language reflects the complex interaction between neural damage, cognitive constraints, and preserved linguistic mechanisms across neurological conditions.

Limitations and future research

Although this study marks a critical starting point for comparing more than one and especially often conditions that are dissimilar in their underlying pathology making this comparison possible there are several that are inherent to this approach. First, for many neurological conditions, especially rare disorders or the initial stages of more common ones like MCI, large-scale speech datasets are lacking, especially for languages other than English, so shared corpora like DementiaBank and TalkBank are crucial.