Abstract

Background

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) is a widespread and aggressive malignancy where early and accurate detection is essential for improving patient outcomes. Traditional diagnostic methods relying on histopathological examination are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and susceptible to subjective interpretation. Moreover, inter-observer variability can further compromise diagnostic consistency, leading to delays in timely intervention. In recent years, advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and computer-aided diagnostic systems have shown transformative potential in medical imaging, enabling faster, objective, and reproducible detection of complex disease patterns. Particularly, deep learning–based models have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in histopathological analysis, making them promising tools for OSCC diagnosis and early clinical decision-making. Methods: This study introduces a Deep Visual Detection System (DVDS) designed to automate OSCC detection using histopathological images. Three convolutional neural network (CNN) models—EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50—were trained and evaluated on two publicly available datasets: the Kaggle Oral Cancer Detection dataset containing 5192 images labeled as Normal or OSCC, and the NDB-UFES dataset comprising 3763 images categorized into OSCC, leukoplakia with dysplasia, and leukoplakia without dysplasia. Data augmentation techniques were employed to mitigate class imbalance and enhance model generalization, while advanced image preprocessing methods and training strategies such as EarlyStopping and ReduceLROnPlateau were applied to ensure stable convergence. Results Among the models tested, EfficientNetB3 consistently delivered superior performance across both datasets. On the binary classification task, it achieved a test accuracy of 97.05%, with precision, recall, and F1-score all at 97.05%, specificity of 97.17%, and sensitivity of 96.92%. On the multi-class NDB-UFES dataset, it again outperformed the other models, attaining a 97.16% accuracy, matching precision, recall, and F1-score, and specificity of 98.58%. In contrast, DenseNet121 and ResNet50 showed substantially lower accuracy scores in both experiments. Conclusion: These results highlight the importance of model architecture and preprocessing in medical image classification tasks. The proposed Deep Visual Detection System (DVDS), built upon EfficientNetB3, demonstrates high reliability and robustness, suggesting strong potential for deployment in clinical settings to aid pathologists in rapid and consistent OSCC diagnosis. This approach could significantly streamline diagnostic workflows and support early intervention strategies, ultimately enhancing patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral cancer remains one of the most prevalent forms of cancer globally, ranking sixth among the most common types. Specifically, oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) constitutes nearly 90% of the aggressive cases, posing significant health risks to affected individuals1. The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights that approximately 657,000 new cases of oral cancer are diagnosed each year globally, leading to more than 330,000 fatalities annually. This alarming statistic underscores the severe impact of OSCC, especially prevalent in developing countries across South and Southeast Asia, where incidence rates are nearly double the global average. India, in particular, accounts for one-third of the global OSCC cases, emphasizing a substantial healthcare burden in the region. Likewise, Pakistan, oral cancer represents the most frequent cancer among males and ranks second among females, indicating a critical public health challenge2.

Further epidemiological studies reveal a significant gender disparity in oral cancer incidence, with men being approximately 2.5 times more likely to develop the disease compared to women. This discrepancy largely results from lifestyle factors such as tobacco use and alcohol consumption3. Even in developed nations, the incidence is notably rising. For example, in the United States, the American Cancer Society’s 2023 survey projected around 54,540 new cases and approximately 7,400 deaths annually, demonstrating the escalating burden of OSCC despite advanced healthcare infrastructure4. Additionally, the GLOBOCAN 2022 database indicated oral cancer constituted 1.9% of all cancers in 2022, resulting in about 188,230 deaths worldwide5. These statistics strongly advocate for more effective detection methods and treatment options, especially in regions heavily affected by this malignancy1.

OSCC typically originates from the squamous cells lining the mouth’s internal surfaces, including the tongue, gums, lips, and cheeks. Annually, this cancer records around 350,000 to 400,000 new cases globally, primarily affecting men and closely associated with risk factors such as tobacco and alcohol usage, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infections6. Although OSCC ranks sixth in global cancer incidence, it becomes the eighth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. Due to a lack of distinct early symptoms, diagnosis relies on lesion characteristics such as size, color, texture and patient habits like smoking and alcohol intake7. Unfortunately, OSCC often presents at advanced stages, hindering treatment effectiveness and resulting in a poor five-year survival rate of approximately 50%8. This delay in detection also escalates healthcare costs, estimated at over $2 billion annually due to the tumor’s complex and diverse nature9.

The early detection of OSCC critically enhances patient outcomes, potentially elevating the five-year survival rate from approximately 20–30% at advanced stages to nearly 80% when detected early10. Rapid and precise diagnosis supports personalized treatment strategies, such as surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy11,12. However, conventional diagnostic methods face notable limitations, including substantial reliance on expert pathologists, time-consuming processes, and considerable susceptibility to errors arising from subjective evaluations influenced by factors such as staining quality and microscope type13,14. Such variability can result in delayed or incorrect diagnoses, significantly impacting the effectiveness of subsequent clinical interventions11.

In addressing these diagnostic challenges, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and computer-aided diagnostic systems are increasingly shaping modern healthcare, offering transformative potential for the early detection and management of cancers, including OSCC. In particular, deep learning (DL) has shown great promise15,16. Unlike traditional machine learning, DL techniques, including deep neural networks (DNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), enable automated feature extraction directly from raw data, significantly improving classification accuracy and diagnostic reliability17,18. Such DL models demonstrate superior performance, particularly in medical imaging applications19,20, as they inherently overcome limitations associated with manual feature selection and offer rapid inference critical for timely clinical decisions21.

CNN architectures, specifically, are extensively used for OSCC detection, leveraging multiple convolutional layers to perform complex feature extraction, followed by dense layers dedicated to the classification tasks22,23. The CNN structure optimizes accuracy through parameters adjusted during training, effectively recognizing distinctive image features indicative of malignancy24,25. Among various CNN architectures explored, EfficientNet, ResNet, and DenseNet stand out due to their robust performance. EfficientNet, introduced by Tan and Le26, incorporates compound scaling across width, depth, and resolution dimensions, delivering high classification accuracy while minimizing computational resources27,28. EfficientNetB3, specifically, is optimal for OSCC detection due to its balanced scaling approach, improved feature extraction capability, rapid inference speed, and lower computational costs compared to earlier versions29. Moreover, EfficientNetB3 was preferred over newer variants such as EfficientNetV2 and Vision Transformer (ViT) because it offers an ideal trade-off between performance and computational efficiency, making it more suitable for histopathological image analysis with limited data availability30.

Similarly, ResNet, significantly enhances deep network performance through residual connections, effectively combating issues such as vanishing gradients common in deep neural architectures31. ResNet50, a popular variant within this family, particularly suits OSCC detection due to its sophisticated 50-layer architecture, exceptional feature extraction capabilities, computational efficiency, and strong validation across diverse medical imaging tasks32,33.

DenseNet, introduced by Huang et al.34, employs densely connected networks that maximize feature reuse, minimize parameter redundancy, and ensure stable gradient flow. DenseNet121, the most popular variant, demonstrates high accuracy with fewer parameters, improved computational efficiency, and excellent performance in medical imaging tasks. These attributes make DenseNet121 highly suitable for precise detection of OSCC35,36.

The primary contributions of this research are as follows:

-

We present Deep Visual Detection System (DVDS), a deep learning framework for automatic OSCC detection using histopathological images.

-

Built on EfficientNetB3, the model balances high accuracy with computational efficiency for medical image classification.

-

Evaluated on two public datasets: Kaggle (binary) and NDB-UFES (multi-class: OSCC, leukoplakia with/without dysplasia).

-

Applied image preprocessing (histogram equalization, normalization, augmentation) and training techniques (EarlyStopping, ReduceLROnPlateau) for improved performance.

-

Achieved 97.05% (binary) and 97.16% (multi-class) accuracy, outperforming DenseNet121 and ResNet50 across all metrics.

-

DVDS demonstrates strong clinical potential for accurate, consistent, and rapid OSCC diagnosis.

This paper is organized as follows: Section “Related work” reviews related work in deep learning for medical image analysis. Section "Employed datasets" details the employed datasets. Section “”Methodology" explains the methodology, including preprocessing, model architecture, and training strategies. Section "Results" presents the results, while Section "Discussions" offers a detailed discussion and performance comparison. Section "Conclusion" concludes the study, and Section "Future work" outlines future research directions.

Related work

Oral cancer remains one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide, largely due to its late-stage diagnosis, emphasizing the critical need for enhanced early detection techniques37. Recent advancements in deep learning (DL), especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have substantially improved diagnostic capabilities. For instance, a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (FJWO-DCNN) trained on the BAHNO NMDS dataset achieved 93% accuracy, although generalization concerns persist due to limited dataset size. Another significant study leveraged transfer learning with AlexNet to classify oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) biopsy images, reporting an accuracy of 90.06%, underscoring the efficacy of pretrained networks in medical imaging tasks38. Further developments in DL have incorporated multimodal imaging, significantly enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Liana et al. combined brightfield and fluorescence microscopy techniques, applying a Co-Attention Fusion Network (CAFNet), which attained an accuracy of 91.79%, surpassing human diagnostic performance39. Yang et al. utilized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a three-stage DL model for detecting cervical lymph node metastasis (LNM) in OSCC patients, achieving a notable AUC of 0.97, thereby substantially reducing rates of occult metastasis40. Mario et al. integrated DL with Case-Based Reasoning (CBR), achieving 92% accuracy in lesion classification using a redesigned Faster R-CNN architecture validated through a publicly accessible dataset41.

Studies comparing CNNs to traditional machine learning methods like SVM and KNN indicate superior performance by CNNs, achieving up to 97.21% accuracy in segmentation and classification tasks42. Additionally, 3D CNN models have proven more effective than traditional 2D CNNs in analyzing spatial and temporal imaging data for early OSCC detection43. Navarun et al. noted performance issues when entirely replacing CNN layers during transfer learning, suggesting partial layer training as a more efficient alternative for smaller datasets44. Other investigations using fuzzy classifiers reached an accuracy of 95.70%45, CNN achieved 78.20% in cervical lymph node diagnosis46, and fluorescent confocal microscopy images provided accuracy up to 77.89%47. Hyperspectral image-based CNN approaches reported an accuracy of 94.5%48, and CNN successfully differentiated oral cancer types on MRI images with 96.50% accuracy49. Meanwhile, feature extraction methods using SVM classifiers yielded 91.64% accuracy in oral cancer diagnosis50.

Predictive modeling using Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) for oral cancer risk demonstrated promising results, reaching an accuracy of 78.95%, suggesting significant potential for clinical use51. Deep learning applied to histopathological data has notably improved classification accuracy, clearly distinguishing OSCC from leukoplakia with an accuracy rate of 83.24%52. Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy (CLE) combined with DL techniques also showed excellent diagnostic accuracy (88.3%), highlighting clinical applicability53. Prognostic predictions using machine learning have shown effectiveness in forecasting clinical outcomes, with decision tree and logistic regression methods achieving accuracies between 60 to 76% for disease progression and survival outcomes54,55. DenseNet201 consistently demonstrated high OSCC detection accuracy at 91.25%56.

Custom CNN architectures leveraging ResNet50 and DenseNet201 for feature extraction reported up to 92% classification accuracy57. Gradient-weighted class activation mapping and handheld imaging devices achieved significant diagnostic accuracies up to 86.38%, overcoming challenges posed by varied imaging conditions58,59. Moreover, 3D CNN-based algorithms demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional 2D CNN methods, offering better early detection accuracy60. Integration of gene-expression profiles and clinical data using machine learning algorithms like XGBoost predicted OSCC patient survival outcomes with an accuracy of 82%61.

Transfer learning consistently achieved high diagnostic accuracy above 90%, proving effective across diverse datasets62,63. Faster R-CNN models delivered reliable lesion detection with an F1 score of 79.31%64. Studies evaluating various CNN models such as EfficientNetB3, DenseNet201, and Vision Transformers (ViT) regularly demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy levels, generally exceeding 90%, despite persistent challenges such as interpretability, class imbalance, and generalizability65. ViT models, in particular, achieved remarkable classification accuracy, up to 97%, indicating robust performance even under dataset constraints66.

In conclusion, the application of deep learning and artificial intelligence methods has greatly advanced oral cancer detection and prognosis. Ongoing innovations in multimodal data integration and model optimization promise further improvements, ultimately enhancing clinical decision-making and patient outcomes.

Challenges noted in recent research

The previous research studies exhibit the following challenges:

-

Most studies used limited or single-source datasets, reducing model generalizability across diverse clinical settings37,67,68

-

Many approaches relied on time-consuming or computationally expensive methods, limiting real-time applicability58,60

-

Reported accuracies were often low with incomplete or inconsistent performance metrics61,64

-

External validation and class-wise performance evaluation were frequently missing, limiting insight into model reliability69

-

Focus remained on binary classification, ignoring multi-class or stage-specific detection of OSCC58,61.

The proposed work directly addresses these challenges by utilizing multi-source datasets, comprehensive evaluation metrics, and optimized deep learning architectures to enhance model generalizability and diagnostic reliability.

Employed datasets

Two histopathological image datasets were used in this study: the Kaggle OSCC Detection Dataset and the NDB-UFES Oral Cancer Dataset. A summary comparison of both datasets is provided below.

Kaggle OSCC dataset

The Kaggle dataset consists of 1,224 original histopathological images (100× and 400× magnification), later expanded through augmentation to a total of 5,192 images. These images include normal epithelium and OSCC tissue samples collected from 230 patients. The dataset is publicly accessible on Kaggle under the CC0: Public Domain license, allowing unrestricted use for research, including CNN-based histopathological image classification70. Table 1 presents Kaggle OSCC dataset.

-

a.

Data Collection: Tissue samples were collected and prepared by medical experts, followed by image acquisition using a Leica ICC50 HD microscope at 100× and 400× magnifications. To enhance cellular and structural details, all slides were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), ensuring clear visualization of histopathological features. Figure 1 shows sample images from the OSCC dataset.

-

b.

Data Division: The dataset, comprising Normal and OSCC classes, was split into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) sets using stratified sampling to preserve class balance. This ensured fair training, tuning, and evaluation while reducing overfitting. Table 2 summarizes the class wise division of the Kaggle Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma dataset for training, validation, and test.

Figure 2 illustrates the class balance in the oral cancer dataset, with roughly 52% OSCC and 48% Normal cases.

-

c.

Data Preprocessing: Preprocessing ensured input consistency, improved model performance, and minimized overfitting. It involved image resizing, enhancement, and augmentation.

-

d.

Image Resizing: Images were resized to 300 × 300 for EfficientNetB3 and 224 × 224 for DenseNet121 and ResNet50 to meet model input requirements while preserving key histological features.

-

e.

Data Augmentation: Horizontal flipping was applied to the training set to enhance robustness and prevent overfitting. No augmentation was applied to validation or test sets, and test set shuffling was disabled for consistent evaluation.

NDB-UFES OSCC dataset

This dataset includes 237 original images annotated with demographic and clinical data, collected between 2010–2021 at UFES, Brazil. It comprises three categories: OSCC, leukoplakia with dysplasia, and leukoplakia without dysplasia60. The dataset is openly accessible via the Mendeley Data Repository for research use71. Table 3 presents details of NDB-UFES OSCC Dataset.

Table 4 shows leukoplakia (61.04%) was more common than OSCC (38.96%) among 77 lesions. Most patients were over 60, with missing data on key risk factors like skin color, tobacco, and alcohol use.

-

a.

Data Collection: Tissue samples were collected through patient biopsies at UFES and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to enhance histopathological features. The slides were examined using Leica DM500 and ICC50 HD microscopes, and each diagnosis was confirmed by two or three oral pathologists. The study was approved by the UFES Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. 5,022,438), with strict adherence to patient confidentiality and ethical standards.

Figure 3 shows the sample images from NDB-UFES OSCC dataset.

-

b.

Data Annotation and Labeling: From 237 expert-labeled images, 3,763 patches (512 × 512) were extracted and categorized as OSCC, With Dysplasia, or Without Dysplasia. Labels were stored in CSV files and used to organize data into class folders. Manual checks ensured labeling accuracy. Table 5 presents Class-Wise Distribution of image patches in the NDB-UFES OSCC Dataset.

-

c.

Data Division: The dataset, divided into Without Dysplasia, With Dysplasia, and OSCC, was split into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing using stratified sampling to maintain class balance. This ensured reliable training and evaluation. Table 6 shows NDB-UFES OSCC dataset before augmentation.

Figure 4 shows imbalance data in the NDB-UFES OSCC dataset, with most samples labeled With Dysplasia, emphasizing the need for augmentation before training.

-

d.

Data Preprocessing: Preprocessing is essential for preparing histopathological images for model training. It ensures consistency in input size, improves performance, and helps prevent overfitting. The preprocessing pipeline in this study involved image resizing, enhancement, and augmentation.

-

e.

Image Resizing: To meet the input requirements of each CNN Model, images were resized accordingly: 300 × 300 pixels for EfficientNetB3, and 224 × 224 pixels for both DenseNet121 and ResNet50. This resizing preserved key tissue structures while enabling efficient model training.

-

f.

Image Enhancement techniques are used to improve image quality & highlight diagnostic features, enhancement techniques specifically hue and saturation adjustments were applied. These adjustments increased contrast and supported better feature learning by the models.

-

g.

Data Augmentation: To address class imbalance, augmentation was applied only to the training set. Techniques included horizontal and vertical flipping, as well as random rotations within a ± 30° range. These methods introduced variation in orientation and structure, improving the model’s generalization. Validation and test sets were left unaltered to ensure fair evaluation. Additionally, shuffling was disabled for the test set to maintain consistency in performance measurement. Figure 5 displays the image enhancement and data augmentation techniques applied to NDB-UFES OSCC dataset. Table 7 presents OSCC NDB-UFES dataset details after data augmentation.

Methodology

This study presents a deep visual detection system for OSCC classification using a fine-tuned EfficientNetB3 model, chosen for its balance of efficiency and performance. The architecture includes a pre-trained base, batch normalization, a regularized dense layer, dropout, and a softmax classifier. DenseNet121 and ResNet50 were also implemented with the same structure and training settings for fair comparison. The methodology covers the training strategy, model configurations, evaluation metrics, and experimental setup. Figure 3 illustrates the complete training workflow.

Training strategy

Figure 6 proposed Deep Visual Detection System Training Strategy and Workflow for OSCC Image Classification.

-

a.

Model Configuration: All three models EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50 were initialized with pre-trained weights from the ImageNet dataset, excluding their top classification layers by setting include_top = False. This allowed for the replacement of the original fully connected layers with custom classification heads tailored to the specific oral cancer classification tasks. A global average pooling layer (pooling = ‘avg’) was then applied to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, effectively decreasing the number of parameters and minimizing the risk of overfitting. On top of each model, a customized set of dense and regularized layers was added to complete the classification pipeline based on the task at hand.

-

b.

Optimizer and Loss: For model optimization, different optimizers were selected based on the individual characteristics and learning behavior of each architecture. The categorical cross-entropy loss function was employed, as it is well-suited for both binary and multi-class classification tasks, allowing for effective learning from labeled image data.

-

c.

Evaluation Metric: Model performance during both training and validation phases was monitored primarily using accuracy as the evaluation metric. This provided a direct measure of the model’s ability to correctly classify input images across all classes.

-

d.

Early Stopping and Learning Rate Scheduling: To prevent overfitting and enhance convergence, early stopping and ReduceLROnPlateau were applied. Training halted if validation loss didn’t improve for 10 consecutive epochs, preserving the best weights. Additionally, the learning rate was reduced by a factor of 0.1 after five stagnant epochs to fine-tune learning in later stages.

-

e.

Training Phases: The training process was divided into four phases to analyze the impact of varying epochs and batch sizes. Phases 1 and 2 involved 10 epochs with batch sizes of 32 and 64, respectively, enabling comparison between small and large updates. Phases 3 and 4 extended training to 20 epochs with the same batch sizes, allowing deeper learning and evaluation under prolonged training conditions.

-

f.

Model Saving: At the end of each training phase, model weights were saved separately for each configuration to preserve progress. Additionally, complete models including both architecture and weights were stored in clearly labeled folders according to epoch and batch size settings (e.g., epochs10-batch32, epochs20-batch64). This structured approach enabled systematic comparison of performance across all training configurations.

Convolutional feature extractor (base model)

1. The initial component of the architecture is a pre-trained base model loaded with ImageNet weights and without the final classification layers. These models are used as feature extractors to learn spatial hierarchies of features from input images. The mathematical representation of the convolution operation in the feature extractor is:

where:

-

\({A}_{i}^{\left(l-1\right)}\) represents the feature map from the \(\left(l-1\right)\) th layer,

-

\({W}_{ij}^{\left(l\right)}\) is the convolution kernel between the \(i\) th and \(j\) th map,

-

\({\beta }_{j}^{\left(l\right)}\) is the bias term,

-

\(g\left(\cdot \right)\) is the non-linear activation function,

-

\(*\) represents the convolution operation.

This process facilitates learning of both low-level (edges, textures) and high-level (shapes, objects) features72.

2. Batch Normalization Layer: To accelerate convergence and stabilize the training process, a Batch Normalization layer is used after the base model. It normalizes the activations using the mean and variance of the current batch:

where:

-

\({\mu }_{B}\) and \({\sigma }_{B}^{2}\) are the mean and variance of the batch,

-

\(\gamma ,\beta\) are learnable parameters,

-

\(\epsilon\) is a small constant to avoid division by zero.

Batch Normalization helps mitigate internal covariate shift and improves gradient flow during backpropagation73.

3. Fully Connected Layer with Regularization: After normalization, a Dense (fully connected) layer is added with ReLU activation and multiple forms of regularization such as L2 weight decay, L1 activation sparsity, and L1 bias constraint. The ReLU activation function is mathematically expressed as:

The output of the dense layer can be defined as:

where \({W}^{\left(l\right)}\) and \({b}^{\left(l\right)}\) are the weight matrix and bias vector for the \(l\) th layer, and \({a}^{\left(l-1\right)}\) is the input from the previous layer74.

4. Dropout Regularization: To reduce the likelihood of overfitting, a Dropout layer is added after the fully connected layer. Dropout randomly disables a portion of neurons during training. This can be represented as:

where \(r\) is a binary mask generated from a Bernoulli distribution with dropout probability \(p\), and \({a}^{\left(l\right)}\) is the activation before dropout75.

5. Output Layer: Softmax Classifier: For multi-class classification, the final layer uses a Softmax activation function to convert the network output into probability values. The softmax function is defined as:

where:

-

\({\theta }_{j}\) is the weight vector for class \(j\),

-

\(x\) is the input to the softmax layer,

-

\(K\) is the total number of classes.

This function ensures that the sum of all predicted class probabilities is equal to 176.

Employed deep learning models

The three deep learning models used in this study are as follows: EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50.

-

a.

Model 1: EfficientNetB3 Architecture

EfficientNetB3 was selected for its strong balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The model was initialized with ImageNet pre-trained weights and adapted for both binary (Normal vs. OSCC) and multi-class (Without Dysplasia, With Dysplasia, OSCC) classification tasks through transfer learning.

Figures 7 and 8 illustrate the classification pipelines for the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. Before training, images were resized, normalized, and augmented to enhance feature learning and generalization.

The model’s original top layers were replaced with a custom classification head tailored for oral cancer detection, including batch normalization for stability, a dense layer with 256 units and L1/L2 regularization, a dropout layer (rate 0.45), and a final dense layer with softmax activation. It was compiled using the Adamax optimizer (learning rate: 0.0001) and categorical cross-entropy loss, with accuracy as the evaluation metric. To avoid overfitting, early stopping (patience = 10) and ReduceLROnPlateau (factor = 0.1) were applied. The model was trained under four configurations 10 and 20 epochs with batch sizes of 32 and 64 to allow effective tuning across classification tasks.

-

b.

Model 2: DenseNet121 Architecture

DenseNet121 was selected for its ability to promote feature reuse and maintain strong gradient flow across layers, making it highly efficient for medical image classification. The model was initialized with pre-trained ImageNet weights and modified with a custom classification head to handle both binary (Normal vs. OSCC) and multi-class (Without Dysplasia, With Dysplasia, OSCC) classification tasks.

Figures 9 and 10 depict the DenseNet121-based pipeline used for the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. Prior to training, all images underwent standard preprocessing procedures including resizing, normalization, and augmentation to optimize model learning and generalization.

The model’s default top layers were removed and replaced with a tailored classification head optimized for OSCC detection, comprising batch normalization to enhance training stability, a dense layer with 512 units incorporating L1 and L2 regularization, a dropout layer with a 0.45 rate for regularization, and a final dense layer with softmax activation for outputting class probabilities. The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, categorical cross-entropy as the loss function, and accuracy as the evaluation metric. To improve generalization and prevent overfitting, Early Stopping was applied to terminate training based on validation loss stagnation, and ReduceLROnPlateau was employed to dynamically lower the learning rate when necessary. Training was conducted under four different configurations 10 and 20 epochs, each with batch sizes of 32 and 64 across both binary and multi-class classification setups, allowing comprehensive evaluation of model performance under varying conditions.

-

c.

Model 2: ResNet50 Architecture

ResNet50 was chosen for its deep residual learning framework, which utilizes shortcut (skip) connections to effectively combat the vanishing gradient problem, making it well-suited for complex image classification tasks such as oral cancer detection. The model was initialized with pre-trained ImageNet weights, and the top classification layers were removed to allow the integration of a custom head tailored for both binary (Normal vs. OSCC) and multi-class (Without Dysplasia, With Dysplasia, and OSCC) classification tasks.

Figures 11 and 12 demonstrate the ResNet50-based pipeline applied to the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets, respectively. All images were preprocessed through resizing, normalization, and data augmentation to enhance model learning and generalization capabilities.

To adapt ResNet50 for OSCC detection, its original output layers were replaced with a custom classification head comprising batch normalization for training stability, a dense layer with 256 units using L1/L2 regularization, a dropout layer with a rate of 0.3 to reduce overfitting, and a final dense layer with softmax activation to generate probability outputs. The model was compiled using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, employing categorical cross-entropy as the loss function and accuracy as the evaluation metric. To improve generalization and prevent overfitting, Early Stopping was used to halt training upon validation loss stagnation, while ReduceLROnPlateau dynamically lowered the learning rate during periods of no improvement. Training was carried out under four configurations 10 and 20 epochs with batch sizes of 32 and 64 across both binary and multi-class classification tasks, enabling a thorough assessment of model performance under varying training conditions.

Evaluation metrics

To assess the performance of the models in classifying histopathological images as either “Normal” or "OSCC," several evaluation metrics were employed. These metrics provide a comprehensive understanding of the model’s predictive capabilities, especially in the context of medical diagnosis where both false positives and false negatives carry critical implications.

In these evaluations, β represents correctly predicted positive samples, Δ denotes correctly predicted negative samples, ψ indicates incorrectly predicted positive samples, and κ corresponds to incorrectly predicted negative samples.

Accuracy (Eq. 7) indicates the ratio of total correct predictions, where β corresponds to true positives (accurately detected OSCC) and Δ to true negatives (correctly identified Normal cases).

Specificity (Eq. 8) evaluates how effectively the model identifies negative cases. Here, Δ stands for true negatives, while ψ represents false positives (Normal samples misclassified as OSCC).

Recall or Sensitivity (Eq. 9) assesses the model’s ability to detect actual positive cases, with β indicating true positives and κ denoting false negatives (OSCC instances the model failed to detect).

Precision (Eq. 10) defines the accuracy of positive predictions, where β represents true positives and ψ accounts for false positives.

F1 Score (Eq. 11) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both metrics:

Misclassification Rate (Eq. 12) reflects the proportion of incorrect predictions, considering ψ (false positives) and κ (false negatives).

Together, these metrics offer a robust evaluation framework for measuring model accuracy, error tendencies, and diagnostic reliability in both balanced and imbalanced clinical datasets.

Experimental SETUP

All model training, validation, and evaluation procedures were performed on a local system to maintain full control over the experimental workflow and ensure consistency throughout the process.

-

a.

Hardware Specifications

The experiments were executed on a MacBook Pro (2021) running macOS version 15.4. The system was equipped with an Apple M1 Max chip featuring a 10-core CPU and a 32-core integrated GPU. It included 32 GB of unified memory and 1 TB of SSD storage, providing sufficient computational power and storage capacity for deep learning workloads. The device featured a 16.2-inch Retina XDR display with a resolution of 3456 × 2234, and a variety of connectivity options including three Thunderbolt/USB 4 ports, an HDMI port, an SDXC card slot, MagSafe 3 charging, and Touch ID for secure access.

-

b.

Software and Environment Setup

The software environment was set up on macOS using Python 3.9.6, with libraries installed via pip, including Jupyter Lab and deep learning frameworks. All installations and updates were managed through the terminal. Jupyter Lab operated offline, and all scripts covering preprocessing, training, and evaluation were executed locally with datasets stored on the machine, ensuring a stable and reproducible workflow.

Results

This section presents the performance of three deep learning models EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50 for oral cancer classification using a dataset of 5,192 images, divided into 70% training and 30% testing. Models were evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, specificity, sensitivity, and confusion matrix analysis to assess classification capabilities and misclassification trends. All experiments were conducted locally on a MacBook Pro 2021 (Apple M1 Max, 32 GB RAM, 1 TB SSD) using Python 3.9.6 within Jupyter Lab. The dataset comprised two classes: Normal and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC).

EfficientNetB3

EfficientNetB3 was applied to both the Kaggle dataset, involving binary classification (OSCC vs. Normal), and the NDB-UFES dataset, which posed a multiclass classification problem. To ensure the robustness and generalizability of the model, multiple configurations of batch sizes and training epochs were explored.

For the Kaggle dataset, the EfficientNetB3 model was trained under various settings to determine optimal performance. The best results were achieved with a batch size of 64 and 10 training epochs, where the model demonstrated strong capability in differentiating between normal and cancerous tissue. The performance was consistently high across training and validation phases.

In the case of the NDB-UFES dataset, which contained multiple class labels, the model underwent similar experimentation with hyperparameters. The most effective configuration was found with a batch size of 32 and 20 epochs, yielding the highest classification accuracy across all classes.

Figure 13 illustrates the configuration applied for binary classification using the Kaggle dataset, highlighting layers such as batch normalization, dense layers, and dropout for overfitting prevention. Figure 14 displays the architecture used for multiclass classification on the NDB-UFES dataset, emphasizing similar core components optimized for improved generalization across multiple classes.

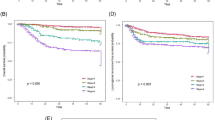

Figure 15 displays similar trends, with losses decreasing to 4.25 (training) and 4.27 (validation), indicating strong alignment between the two sets and minimal overfitting. Accuracy improves steadily, with training accuracy reaching 99.01% and validation accuracy peaking at 97.69%, highlighting stable and efficient learning.

In Fig. 16, both losses steadily decline to around 1.5 (training) and 1.6 (validation), suggesting strong convergence. Accuracy improves sharply during the early epochs and stabilizes at ~ 0.88 (training) and ~ 0.80 (validation), reflecting robust model performance with low signs of overfitting. Table 8 presents EfficientNetB3’s performance on Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. The model achieved high accuracy on both, with slightly better optimization on NDB-UFES due to longer training. Performance remained consistent across all phases, indicating good generalization.

Figure 17 shows the confusion matrix for the same model trained with 10 epochs and a batch size of 64. The model exhibited a well-balanced performance, with high true positives and true negatives, and low false predictions. This configuration demonstrated strong sensitivity and specificity, indicating reliable classification of both cancerous and non-cancerous cases.

Figure 18 demonstrates slightly better performance over the 10-epoch setup. OSCC TPs improved to 163, and false positives reduced. The “With Dysplasia” and “Without Dysplasia” classes maintained high classification precision, indicating better overall learning and generalization. Tables 9 and 10 summarizes confusion matrix results for Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. The Kaggle model (binary classification) showed balanced TP and TN with minimal FP and FN. On the NDB-UFES dataset (multi-class), all classes achieved high TP with low misclassifications, indicating strong class-wise performance and generalization.

Table 11 compares classification performance across the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. Both datasets show high precision, recall, and F1-scores (~ 0.97) for all classes, indicating consistent and balanced classification. NDB-UFES also maintained strong class-wise performance in multi-class setup. Table 12 presents overall performance metrics, where both configurations achieved nearly identical accuracy (~ 0.97), with NDB-UFES showing slightly better specificity, suggesting improved true negative recognition in multi-class classification.

DenseNet121

DenseNet121 was applied to both the Kaggle dataset (binary classification: OSCC vs. Normal) and the NDB-UFES dataset (multi-class classification). To assess the model’s learning behavior and optimize its performance, training was conducted under multiple configurations, varying both epochs and batch sizes.

On the Kaggle dataset, DenseNet121 showed its best results with 20 epochs and a batch size of 64, achieving a test accuracy of 86.9% with balanced training and validation performance. However, on the NDB-UFES dataset, the model struggled with generalization across multiple classes, with training and validation accuracy stabilizing around 54%. Despite consistent training parameters, DenseNet121 underperformed in the multi-class scenario, highlighting its limitations in handling complex class distributions compared to binary classification.

Figures 19 and 20 represent the model summaries of the DenseNet121 architecture used for oral cancer classification. Figure 19 illustrates the configuration applied for binary classification using the Kaggle dataset, showcasing key components such as batch normalization, dense layers, and dropout to mitigate overfitting. Figure 20 presents the architecture used for multiclass classification on the NDB-UFES dataset, incorporating the same structural elements, but adjusted to enhance generalization across multiple class labels.

Figure 21 (20 epochs, batch size 64) shows a consistent decline in both training (to ~ 3.07) and validation loss (to ~ 2.97), indicating stable training. Accuracy curves steadily rise, with training accuracy reaching 89.14% and validation accuracy at 86.51%, confirming effective learning and strong generalization performance. Figure 22 demonstrates erratic early training loss with batch size 64, followed by gradual decline. Validation loss remains more stable. Training accuracy steadily rises, exceeding 0.65, while validation accuracy is less consistent but reaches a similar level, suggesting late-stage stabilization in learning. Table 13 presents DenseNet121’s performance on Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets.

Figure 23 displays the confusion matrix for 20 epochs and batch size 64. The model achieved a balanced performance with high true positives and true negatives. While some false negatives and false positives were still present, this setup showed a strong trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, making it the best among all configurations.

As shown in Fig. 24, classification improves notably for all three categories. The model identified 46 OSCC cases correctly, with 120 misclassified as “With Dysplasia” and only 1 as “Without Dysplasia.” “With Dysplasia” was predicted with high accuracy (256 correct), although 23 were still confused with OSCC and 22 with “Without Dysplasia.” The “Without Dysplasia” class achieved 15 correct predictions, while 73 were misclassified as “With Dysplasia.” Despite some overlap, this configuration shows the strongest performance for OSCC among all versions. Tables 14 and 15 present confusion matrix results for the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. On the Kaggle dataset, DenseNet121 showed moderate TP/TN but high FP/FN, indicating misclassification. On the NDB-UFES dataset, low TP and high FN across classes reflected poor class-wise performance and limited generalization.

Table 16 shows that DenseNet121 performed reasonably on the Kaggle dataset with ~ 0.87 precision and recall, but struggled on the NDB-UFES dataset, especially with OSCC and Without Dysplasia classes, indicating weak multi-class generalization. Table 17 highlights that while the Kaggle setup achieved good overall metrics (accuracy: 0.87), the NDB-UFES configuration saw a major drop in accuracy (0.55), F1-score, and sensitivity, reflecting poor performance in the multi-class scenario.

ResNet50

ResNet50 was evaluated on both the Kaggle (binary) and NDB-UFES (multi-class) datasets using varied training configurations. On Kaggle, the best setup (10 epochs, batch size 64) yielded moderate accuracy (~ 59%) with high loss, showing limited binary classification performance. Similarly, the NDB-UFES setup (20 epochs, batch size 64) resulted in low performance across all metrics. Overall, ResNet50 showed weak generalization for OSCC detection in both tasks.

Figure 25 shows the configuration designed for binary classification using the Kaggle dataset, and Fig. 26 illustrates the architecture adapted for multi-class classification on the NDB-UFES dataset, incorporating components such as batch normalization, dense layers, and dropout to prevent overfitting.

Figure 27 (10 epochs, batch size 64) shows dramatic spikes in validation loss (~ 9.47), despite relatively stable training loss (~ 8.29). Training accuracy rises to 72.22%, and validation to 71.05%, indicating slight improvement but persistent instability in validation.

Figure 28 shows the most stable performance with 20 epochs, batch size 64. Both loss and accuracy curves are smooth, with minimal spikes. Validation loss dips at epoch 4, while best validation accuracy is observed at epoch 7, indicating strong and consistent model performance. Table 18 presents ResNet50’s performance on Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets.

Figure 29 shows results for 10 epochs and batch size 64. The model improved slightly, detecting some normal cases correctly. However, a significant number of OSCC cases were still misclassified as normal, showing moderate sensitivity and limited precision.

Figure 30 exhibits the best overall balance. OSCC had 161 TPs, and both dysplasia classes achieved excellent accuracy (292 and 90 TPs). False positives and negatives are minimal, highlighting this setup as the most reliable and effective among all tested configurations.

Tables 19 and 20 summarize confusion matrix results for the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets using ResNet50. On the Kaggle dataset (binary classification), the model showed low TN and high FP, indicating poor distinction between classes. For the NDB-UFES dataset (multi-class), misclassifications were high across all classes—especially for “Without Dysplasia,” where no true positives were detected reflecting weak class-wise performance and limited generalization.

Table 21 compares classification performance for ResNet50 across the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets. On the Kaggle dataset, the model achieved moderate recall for OSCC but struggled with Normal class precision, resulting in overall low accuracy (60%). For the NDB-UFES dataset, performance dropped further, especially for the “Without Dysplasia” class, which had zero precision and recall, indicating poor class-wise balance and weak generalization in multi-class classification.

Table 22 presents overall performance metrics for ResNet50 on both datasets. The Kaggle model showed low accuracy (59%) with high sensitivity but very low specificity, indicating frequent false positives. On the NDB-UFES dataset, accuracy remained low (56%) with a slight improvement in specificity, but overall performance reflects weak class discrimination and poor generalization.

Comparison analysis of EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, ResNet50 on Kaggle and NDB-UFES OSCC datasets

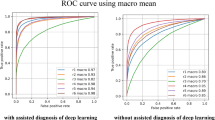

This section provides a detailed comparative evaluation of EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50, analyzing their performance on binary and multi-class OSCC classification using the Kaggle and NDB-UFES datasets presented in Table 23.

Table 23 and Fig. 31 presents the best recorded performance of EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50 across both the Kaggle Binary-Class and NDB-UFES Multiclass datasets. Among all configurations and datasets, EfficientNetB3 consistently outperformed the other models, achieving the highest accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, specificity, and sensitivity.

On the Kaggle dataset, it reached an exceptional 97.05% accuracy, while on the NDB-UFES dataset, it attained 97.16% accuracy, confirming its robustness across binary and multiclass classification tasks. DenseNet121 showed moderate performance, especially on the Kaggle dataset with 86.91% accuracy, but failed to generalize effectively on the more complex NDB-UFES dataset. ResNet50, in contrast, remained the least effective model overall, with limited accuracy and poor metric scores, particularly in multiclass settings. These results strongly support the selection of EfficientNetB3 as the most suitable model for oral cancer detection due to its consistent, reliable, and superior performance across varied data complexities.

Comparative analysis with existing methods

As shown in Table 24, the proposed Deep Visual Detection System (DVDS), leveraging EfficientNetB3 with augmentation, preprocessing, and training callbacks, outperformed all recent methods in oral cancer detection. It achieved the highest accuracy on both Kaggle (97.04%) and NDB-UFES (97.15%) datasets. In comparison, DenseNet121 and ResNet50 delivered notably lower results, confirming DVDS as the most accurate and reliable solution for histopathological OSCC classification.

Discussions

This study developed a Deep Visual Detection System for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) using three CNN architectures: EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50. Evaluations were conducted on the Kaggle OSCC dataset (binary classification) and the NDB-UFES dataset (multi-class classification). Among the models, EfficientNetB3 consistently outperformed the others, achieving 97.05% accuracy on the binary dataset and 97.16% on the multi-class dataset. EfficientNetB3’s superior performance is attributed to its compound scaling strategy, enabling effective feature extraction crucial for medical imaging. DenseNet121 showed potential in specific configurations but suffered from generalization issues, while ResNet50 underperformed overall. Training dynamics such as batch size and epochs notably influenced results for EfficientNetB3 but had limited effect on the other models. By extending the classification task beyond binary labels using a clinically annotated dataset, this research adds to the development of real-world diagnostic tools. However, limitations include the absence of clinical validation, potential class imbalance, and lack of explainability mechanisms. Ethical considerations around fairness and misdiagnosis also remain important concerns.

In particular, the proposed Deep Visual Detection System (DVDS), built on EfficientNetB3 with preprocessing, augmentation, and optimization strategies such as EarlyStopping and ReduceLROnPlateau, demonstrated remarkable robustness across both datasets. The consistent performance of DVDS highlights its potential for integration into clinical workflows, where rapid and accurate diagnosis is critical. Furthermore, the use of two distinct datasets strengthens the generalizability of findings, though validation on larger and more diverse clinical datasets is necessary. Future work could focus on incorporating explainable AI modules and prospective clinical trials to bridge the gap between experimental accuracy and practical deployment.

To translate the proposed Deep Visual Detection System into clinical practice, several steps are necessary. First, clinical validation through large-scale, multi-center studies involving diverse patient cohorts would be required to establish robustness and generalizability. Second, integration into existing pathology workflows demands close collaboration with clinicians to ensure usability, interoperability with hospital information systems, and minimal disruption of established diagnostic routines. Adoption barriers such as data heterogeneity, differences in imaging protocols, regulatory approval processes, and the requirement for interpretability mechanisms also need to be systematically addressed. Additionally, careful attention to ethical, legal, and infrastructural considerations will be vital to avoid bias and ensure equitable deployment across healthcare settings. Future research will therefore focus not only on improving model performance but also on developing strategies for seamless and responsible deployment in real-world healthcare environments.

Conclusion

In pursuit of enhancing automated diagnosis in medical imaging, this work presented a Deep Visual Detection System for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) using three state-of-the-art CNN architectures EfficientNetB3, DenseNet121, and ResNet50 evaluated on two diverse datasets. By addressing both binary and multi-class classification tasks, the research advanced current methodologies in automated OSCC diagnosis. EfficientNetB3 consistently outperformed the other models, achieving 97.05% accuracy on the Kaggle dataset and 97.16% on the NDB-UFES dataset. Its robust performance across evaluation metrics underscores its potential for clinical integration. These findings highlight the critical role of architecture selection, preprocessing, and hyperparameter tuning in medical image analysis. While the results are promising, limitations such as the absence of clinical trials, constrained dataset diversity, and lack of explainability must be addressed. Nonetheless, this work establishes a strong foundation for intelligent, scalable, and reliable OSCC detection. With further validation and deployment, the proposed system particularly the EfficientNetB3 model could become a valuable asset in early cancer diagnostics and patient care.

Future work

To address the identified limitations, future work may incorporate explainability frameworks such as Grad-CAM to enhance interpretability for clinicians. Strategies like advanced augmentation, class-weighted loss functions, or synthetic sampling can help mitigate class imbalance and improve robustness. Moreover, since the present study employed publicly available datasets that may not fully capture the heterogeneity of clinical practice, comprehensive validation across diverse populations, varying imaging protocols, and staining methodologies will be essential to strengthen contextual validity and ensure broader generalizability of the proposed system.

Future directions include:

-

Clinical Validation: Deploying the system in pilot clinical studies to assess real-world performance.

-

Application Development: Creating lightweight, deployable apps using frameworks like TensorFlow Lite for broader accessibility.

-

Explainable AI: Integrating methods like Grad-CAM to enhance clinician trust.

-

Multimodal Integration: Combining image data with patient history for comprehensive diagnostics.

-

Model Generalization: Applying transfer learning and domain adaptation to improve performance across diverse datasets and settings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shabir, A. et al. LWFDTL: lightweight fusion deep transfer learning for oral Squamous cell Carcinoma diagnosis using Histopathological oral Mucosa. Multimed. Tools Appl. 84, 30359–30383 (2025).

Anwar, N. et al. Oral cancer: Clinicopathological features and associated risk factors in a high-risk population presenting to a major tertiary care center in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 15(8), e0236359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236359 (2020).

Gong, H. et al. Identification of cuproptosis-related lncRNAs with the significance in prognosis and immunotherapy of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Comput. Biol. Med. 171, 108198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108198 (2024).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68(6), 394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 (2018).

Li, J., He, H. G., Guan, C., Ding, Y. & Hu, X. Dynamic joint prediction model of severe radiation-induced oral mucositis among nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective longitudinal study. Radiother. Oncol. 209, 110993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2025.110993 (2025).

Uz, U. & Eskiizmir, G. Association between interleukin-6 and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 14(1), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2019.00906 (2021).

D’Silva, N. J. & Ward, B. B. Tissue biomarkers for diagnosis and management of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Alpha Omegan. 100(4), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aodf.2007.10.014 (2007).

Speight, P. M., Khurram, S. A. & Kujan, O. Oral potentially malignant disorders: risk of progression to malignancy. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 125(6), 612–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2017.12.011 (2018).

Cheng, Y. et al. The investigation of Nfκb inhibitors to block cell proliferation in OSCC cells lines. Curr. Med. Chem. 32(33), 7314–7326. https://doi.org/10.2174/0109298673309489240816063313 (2025).

Luo, C. et al. Deubiquitinase PSMD7 facilitates pancreatic cancer progression through activating Nocth1 pathway via modifying SOX2 degradation. Cell Biosci. 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-024-01213-9 (2024).

Weckx, A. et al. Time to recurrence and patient survival in recurrent oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 94, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.05.002 (2019).

Alqaraleh, M., Khleifat, K. M., Abu Hajleh, M. N., Farah, H. S. & Ahmed, K. A. Fungal-mediated silver nanoparticle and biochar synergy against colorectal cancer cells and pathogenic bacteria. Antibiotics 12(3), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030597 (2023).

Alhussan, A. A. et al. Classification of breast cancer using transfer learning and advanced Al-Biruni Earth Radius optimization. Biomimetics 8(3), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8030270 (2023).

Karimi, M. et al. Feature selection methods in big medical databases: A comprehensive survey. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Comput. Intell. 2025, 181–209. https://doi.org/10.65278/IJTACI.2025.21 (2025).

Larabi-Marie-Sainte, S. et al. Current techniques for diabetes prediction: Review and case study. Appl. Sci. 9(21), 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214604 (2019).

Malik, W., Javed, R., Tahir, F. & Rasheed, M. A. COVID-19 detection by chest X-ray images through efficient neural network techniques. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Comput. Intell. 2025, 35–56. https://doi.org/10.65278/IJTACI.2025.2 (2025).

Saba, T. Automated lung nodule detection and classification based on multiple classifiers voting. Microsc. Res. Tech. 82(9), 1601–1609 (2019).

Lian, W. Intermediate multimodal information fusion for improved AI-based cancer detection, vol. 37 21 (2016). https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1901563&dswid=-743

Saba, T., Al-Zahrani, S. & Rehman, A. Expert system for offline clinical guidelines and treatment. Life Sci. J. 9(4), 2639–2658 (2012).

Kim, H. E. et al. Transfer learning for medical image classification: a literature review. BMC Med. Imaging. 22(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-022-00793-7 (2022).

Li. F. F., Karpathy, A., Johnson, J. & Yeung, S. TAs A. Cs231n: Convolutional neural networks for visual recognition. Stanford University (2016). URL: http://cs231n.stanford.edu.

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 1(42), 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Nasir, S., Bilal, M. & Khalidi, H. Detection and classification of skin cancer by using CNN-enabled cloud storage data access control algorithm based on blockchain technology. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Comput. Intell. 225, 145–169. https://doi.org/10.65278/IJTACI.2025.31 (2025).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 6105–14 (PMLR, 2019). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/tan19a.html

Alhichri, H., Alswayed, A. S., Bazi, Y., Ammour, N. & Alajlan, N. A. Classification of remote sensing images using EfficientNet-B3 CNN model with attention. IEEE Access 12(9), 14078–14094. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3051085 (2021).

Abd El-Ghany, S., Elmogy, M. & El-Aziz, A. A. Computer-aided diagnosis system for blood diseases using EfficientNet-B3 based on a dynamic learning algorithm. Diagnostics 13(3), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030404 (2023).

Batool, A. & Byun, Y. C. Lightweight EfficientNetB3 model based on depthwise separable convolutions for enhancing classification of leukemia white blood cell images. IEEE Access 12(11), 37203–37215. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3266511 (2023).

Albalawi, E. et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma detection using EfficientNet on histopathological images. Front. Med. 29(10), 1349336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1349336 (2024).

Saba, T., Bokhari, S. T. F., Sharif, M., Yasmin, M. & Raza, M. Fundus image classification methods for the detection of glaucoma: A review. Microsc. Res. Tech. 81(10), 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.23094 (2018).

Panigrahi, S. et al. Classifying histopathological images of oral squamous cell carcinoma using deep transfer learning. Heliyon. 9(3), e13444 (2023).

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V. & Alemi, A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 31(1) (2017). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v31i1.11231

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4700–8 (2017). http://ailab.dongguk.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/densenet.pptx.pdf

Kavyashree, C., Vimala, H. S. & Shreyas, J. Improving oral cancer detection using pretrained model. In 2022 IEEE 6th Conference on Information and Communication Technology (CICT) 1–5 (IEEE, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/CICT56698.2022.9997897

Jégou, S., Drozdzal, M., Vazquez, D., Romero, A. & Bengio, Y. The one hundred layers Tiramisu: Fully convolutional DenseNets for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 11–9 (2017). URL: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2017_workshops/w13/html/Jegou_The_One_Hundred_CVPR_2017_paper.html

Hemalatha, S., Chidambararaj, N. & Motupalli, R. Performance evaluation of oral cancer detection and classification using deep learning approach. In 2022 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI) 1–6 (IEEE, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCAI53970.2022.9752505

Rahman, A. U. et al. Histopathologic oral cancer prediction using oral squamous cell carcinoma biopsy empowered with transfer learning. Sensors 22(10), 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22103833 (2022).

Lian, W., Lindblad, J., Stark, C. R., Hirsch, J. M. & Sladoje, N. Let it shine: Autofluorescence of Papanicolaou-stain improves AI-based cytological oral cancer detection. Comput. Biol. Med. 1(185), 109498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109498 (2025).

Yang, L. et al. Diagnosis of lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma by an MRI-based deep learning model. Oral Oncol. 1(161), 107165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2024.107165 (2025).

Cimino, M. G. et al. Explainable screening of oral cancer via deep learning and case-based reasoning. Smart Health 35, 100538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhl.2025.100538 (2025).

Yadav, R. K., Ujjainkar, P. & Moriwal, R. Oral cancer detection using deep learning approach. In IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS) 1–7 (IEEE, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/SCEECS57921.2023.10062993

Tenali, N., Desu, V. S., Boppa, C., Chintala, V. C. & Guntupalli, B. Oral cancer detection using deep learning techniques. In International Conference on Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application (ICIDCA) 168–175 (IEEE, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIDCA56705.2023.10100045

Das, N., Hussain, E. & Mahanta, L. B. Automated classification of cells into multiple classes in epithelial tissue of oral squamous cell carcinoma using transfer learning and convolutional neural network. Neural Netw. 128, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2020.05.003 (2020).

Krishnan, M. M. R. et al. Automated oral cancer identification using histopathological images: A hybrid feature extraction paradigm. Micron 43(2–3), 352–364 (2012).

Ariji, Y. et al. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography image assessment of cervical lymph node metastasis in patients with oral cancer by using a deep learning system of artificial intelligence. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 127(5), 458–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2018.10.002 (2019).

Shavlokhova, V. et al. Deep learning on oral squamous cell carcinoma ex vivo fluorescent confocal microscopy data: A feasibility study. J. Clin. Med. 10(22), 5326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10225326 (2021).

Jeyaraj, P. R. & Samuel Nadar, E. R. Computer-assisted medical image classification for early diagnosis of oral cancer employing deep learning algorithm. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 145(4), 829–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-02834-7 (2019).

Palaskar, R., Vyas, R., Khedekar, V., Palaskar, S. & Sahu, P. Transfer learning for oral cancer detection using microscopic images (2020). arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.11610. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2011.11610

Muthu Rama Krishnan, M., Shah, P., Chakraborty, C. & Ray, A. K. Statistical analysis of textural features for improved classification of oral histopathological images. J. Med. Syst. 36(2), 865–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-010-9550-8 (2012).

Alhazmi, A. et al. Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning for prediction of oral cancer risk. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 50(5), 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13157 (2021).

de Lima, L. M. et al. Importance of complementary data to histopathological image analysis of oral leukoplakia and carcinoma using deep neural networks. Intell. Med. 3(4), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imed.2023.01.004 (2023).

Aubreville, M. et al. Automatic classification of cancerous tissue in laser endomicroscopy images of the oral cavity using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 11979. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12320-8 (2017).

Chu, C. S., Lee, N. P., Adeoye, J., Thomson, P. & Choi, S. W. Machine learning and treatment outcome prediction for oral cancer. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 49(10), 977–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13089 (2020).

Alkhadar, H., Macluskey, M., White, S., Ellis, I. & Gardner, A. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for the prediction of five-year survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 50(4), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13135 (2021).

Begum, S. H. & Vidyullatha, P. Deep learning model for automatic detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) using histopathological images. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 13(1), 889–899. https://doi.org/10.12785/ijcds/130170 (2023).

Deo, B. S., Pal, M., Panigrahi, P. K. & Pradhan, A. An ensemble deep learning model with empirical wavelet transform feature for oral cancer histopathological image classification. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-024-00507-y (2024).

Figueroa, K. C. et al. Interpretable deep learning approach for oral cancer classification using guided attention inference network. J. Biomed. Opt. 27(1), 015001. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.27.1.015001 (2022).

Lin, H., Chen, H., Weng, L., Shao, J. & Lin, J. Automatic detection of oral cancer in smartphone-based images using deep learning for early diagnosis. J. Biomed. Opt. 26(8), 086007. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.26.8.086007 (2021).

Xu, S. et al. An early diagnosis of oral cancer based on three-dimensional convolutional neural networks. IEEE Access 7, 158603–158611. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2950286 (2019).

Cao, R., Wu, Q., Li, Q., Yao, M. & Zhou, H. A 3-mRNA-based prognostic signature of survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. PeerJ 7, e7360. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7360 (2019).

Chinnaiyan, R., Shashwat, M., Shashank, S. & Hemanth, P. Convolutional Neural Network Model based analysis and prediction of oral cancer. In 2021 International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA) 1–4 (IEEE, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAECA52838.2021.9675533

Marzouk, R. et al. Deep transfer learning driven oral cancer detection and classification model. Comput. Mater. Contin. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2022.029326 (2022).

Warin, K., Limprasert, W., Suebnukarn, S., Jinaporntham, S. & Jantana, P. Automatic classification and detection of oral cancer in photographic images using deep learning algorithms. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 50(9), 911–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13227 (2021).

Kaur, G. & Sharma, N. Automated detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma using transfer learning models from histopathological images. In 2024 3rd International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICONAT61936.2024.10775135

Hadilou, M. et al. Artificial intelligence based vision transformer application for grading histopathological images of oral epithelial dysplasia: a step towards AI-driven diagnosis. BMC Cancer 25(1), 780. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-025-14193-x (2025).

Prado, R. L., Marsicano, J. A., Frois, A. K. & Brancher, J. D. The use of machine learning to support the diagnosis of oral alterations. Pesq. Bras. Odontoped. Clin. Integr. 25, e240048. https://doi.org/10.1590/pboci.2025.047 (2025).

Justaniah, E. & Alhothali, A. Classifying oral health issues from spectral imaging using convolutional neural network. In 2025 AI-Driven Smart Healthcare for Society 5.0 143–148 (IEEE; 2025). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF64992.2025.10963258

Bansal, K., Bathla, R. K. & Kumar, Y. Deep transfer learning techniques with hybrid optimization in early prediction and diagnosis of different types of oral cancer. Soft Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-022-07246-x (2022).

Krishnan, M. M. et al. Automated oral cancer identification using histopathological images: a hybrid feature extraction paradigm. Micron 43(2–3), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micron.2011.09.016 (2012).

NDB-UFES: An oral cancer and leukoplakia dataset composed of histopathological images and patient data. https://doi.org/10.17632/bbmmm4wgr8.4

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2818–2826 (2016). URL: https://www.cv-foundation.org/openaccess/content_cvpr_2016/html/Szegedy_Rethinking_the_Inception_CVPR_2016_paper.html

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International Conference on Machine Learning 448–456 (PMLR, 2015). Link: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v37/ioffe15.html

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 249–256 (2010). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v9/glorot10a

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15(1), 1929–1958. https://doi.org/10.5555/2627435.2670313 (2014).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Regularization for deep learning. Deep Learn. 1, 224–270 (2016).

Welikala, R. A. et al. Automated detection and classification of oral lesions using deep learning for early detection of oral cancer. IEEE Access. 8, 132677–132693. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3010180 (2020).

Ghosh, A. et al. Deep reinforced neural network model for cyto-spectroscopic analysis of epigenetic markers for automated oral cancer risk prediction. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 224, 104548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemolab.2022.104548 (2022).

Jubair, F. et al. A novel lightweight deep convolutional neural network for early detection of oral cancer. Oral Dis. 28(4), 1123–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13825 (2022).

Maia, B. M. et al. Transformers, convolutional neural networks, and few-shot learning for classification of histopathological images of oral cancer. Expert. Syst. Appl. 241, 122418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122418 (2024).

Tafala, I., Ben-Bouazza, F. E., Edder, A., Manchadi, O. & Jioudi, B. DeepPatchNet: A deep learning model for enhanced screening and diagnosis of oral cancer. Inf. Med. Unlocked https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2025.101658 (2025).

Pham, T. D. Integrating support vector machines and deep learning features for oral cancer histopathology analysis. Biol. Methods Protoc. 10(1), bpaf034. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomethods/bpaf034 (2025).

Uliana, J. J. & Krohling, R. A. Diffusion models applied to skin and oral cancer classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.00026 (2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.00026

Mandal, R. et al. Analysis of supervised learning approaches for identification of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A multimodal approach. Cuest Fisioter. 54(4), 5299–5309 (2025).

Liao, W. et al. HistoMoCo: Momentum contrastive learning pre-training on unlabeled histopathological images for oral squamous cell carcinoma detection. Electronics 14(7), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071252 (2025).

Olivos, M. A., Del Águila, H. M. & López, F. M. Diagnosis of oral cancer using deep learning algorithms. Ingenius. 7(32), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.17163/ings.n32.2024.06 (2024).

Anitha, D., Soujanya, T., Chakraborty, S., Alkhayyat, A. & Revathi, R. Oral cancer detection and classification using deep learning with DenseNet121–CatBoost classifier. In 2024 Second International Conference on Networks, Multimedia and Information Technology (NMITCON) 1–5 (IEEE; 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/NMITCON62075.2024.10698836

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge the fund by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R346). The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of AIDA Lab CCIS Prince Sultan University, Riyadh Saudi Arabia for APC support.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R346), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KA, MA, NA, ARM, AR; methodology: KA, MA, TW, AR; software: MA, NA, TW; validation: KA, MA, TW, FSA, ARM, AR; writing—original draft preparation, KA, MA, TW, FSA, NA, AR; writing—review and editing: KA, MA, TW, FSA, NA, ARM, AR, visualization: KA, TW, NA, ARM, AR; supervision: FSA, ARM, AR; project administration: KA, MA, ARM, AR; funding: FSA, NA, ARM. All authors had approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akram, K., Aslam, M., Waheed, T. et al. Deep visual detection system for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 16, 4219 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34332-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34332-5