Abstract

Limited research has examined long-term training adaptations in elite Deaf athletes. This three-year longitudinal observational study characterized anthropometric and physical performance changes in the Polish Deaf National Basketball Team preparing for the Deaflympics (2019–2021). Eleven male athletes (age 26.9 ± 6.3 years) underwent annual assessments of body composition and performance, including countermovement jumps (CMJ, ACMJ), spike jump (SPJ), sprint speed (0–5 m, 0–20 m), and estimated VO₂max. A control group of physically inactive Deaf students (n = 15; age 21.1 ± 1.6 years) was also evaluated. Friedman ANOVA revealed stable body composition across seasons (p > 0.05; W = 0.01–0.22), except for a moderate increase in left-leg fat-free mass (p = 0.025; W = 0.33). While jump performance remained unchanged (p > 0.05; d = 0.18–0.32), sprint performance declined significantly (0–5 m: χ²(2) = 20.18, p < 0.001; 0–20 m: χ²(2) = 14.59, p = 0.001). Compared with inactive peers, players demonstrated superior physical capacity, including higher fat-free mass (d = 2.12), greater jump power (d = 3.46), and faster sprint times (d = − 1.03 to − 1.07), with a mean 2021 VO₂max of 47.3 ± 6.1 ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹. In conclusion, these elite athletes maintained morphology and power but showed declining sprint performance, likely due to COVID-19 disruptions. This study provides the first longitudinal evidence of performance trajectories in elite Deaf basketball players, underscoring the need for individualized, acceleration-focused monitoring to sustain long-term neuromuscular performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the growing participation of Deaf athletes in organized sports, scientific understanding of their physical and motor characteristics remains limited. Most available studies are cross-sectional, based on small samples, and offer only fragmented insights into how systematic training influences performance development in Deaf athletes. Longitudinal research tracking morphological and functional adaptation is virtually non-existent, leaving a major gap in our knowledge of how structured training shapes their athletic progression. Although evidence indicates that regular training enhances the physical capacities of Deaf athletes, subtle but consistent performance differences persist compared with hearing peers. Several factors may contribute to these disparities. Physiological studies suggest that Deaf individuals may exhibit less developed respiratory function, possibly due to the reduced use of respiratory muscles for speech-related activities such as speaking or singing1. Another important issue concerns potential abnormalities within the vestibular system, responsible for detecting head position and maintaining balance2. Because the auditory and vestibular systems are anatomically interrelated – both located within the inner ear and transmitting information through cranial nerve VIII – damage to structures such as the cochlea or semicircular canals can impair vestibular function and balance control3,4,5,6,7. Consequently, hearing impairment may be associated with balance deficits, sensory integration challenges, and delays in motor development8,9. Chilosi et al.10 found that children with severe or profound hearing loss often experience difficulties with static and dynamic balance, coordination, and movement speed, though these can sometimes be compensated by enhanced visual processing11. Recent findings by Szulc and Buśko12 indicate that among Deaf girls aged 14–18 – both football players and physically inactive schoolgirls – selected biomechanical variables may be influenced not only by training experience but also by proprioception and musculoskeletal compensation. Similarly, Rajendran and Glory-Roy13 observed slower development of certain motor skills in individuals with hearing impairment. As early as 1975, Matczak14 noted that although Deaf children can achieve comparable fitness levels to hearing peers, they typically require a longer training period to reach these benchmarks. In addition to physiological considerations, social and communication barriers further hinder athletic development. Integration within sports environments dominated by hearing athletes poses unique challenges, particularly when communication relies primarily on sign language. Limited access to effective coach–athlete communication and instructional feedback may reduce training efficiency and learning opportunities. Consequently, beyond physiological or neuromotor factors, communication constraints constitute an additional determinant of performance disparities in Deaf populations. Empirical comparisons between Deaf and hearing athletes highlight both progress and persistence of differences. Szulc15 reported that the morphobiomechanical characteristics of Deaf soccer players differed only slightly (4–15%) from those of hearing athletes. Although the relative lower-limb peak torque was somewhat lower in Deaf players, their values exceeded those of untrained Deaf individuals, indicating substantial training benefits. Similarly, vertical jump power was about 19% lower in Deaf than hearing players, yet still higher than in inactive Deaf peers. These findings suggest that structured training substantially enhances motor performance, even if it does not entirely eliminate the gap with hearing athletes. Comparable trends have been documented in swimming and team sports. Deaf swimmers typically demonstrate slower mean velocities and longer race times than hearing competitors16. In basketball, Szulc and Sandurska17 reported that while Deaf tournaments increasingly resemble high-level hearing competitions, performance differentials persist when both groups compete directly. Analyses of Deaf basketball world championships18 and studies from Lithuania19 and Turkey20 consistently show that although training promotes measurable progress, biomechanical and technical disparities remain. Other research has examined isolated components such as balance21, repeated jumping22, and proprioception23, as well as psychological and neuromotor factors including shooting anxiety23 and repeated sprint ability24. Suner-Keklik et al.25 analyzed shoulder muscle strength and endurance in Deaf basketball players and compared these variables with those of hearing counterparts. However, almost all these studies are cross-sectional and lack follow-up assessments, preventing evaluation of how training-induced adaptations evolve over time.

Recent evidence from hearing populations underscores why longitudinal analysis is crucial. A systematic review by Cao et al.26 showed that functional training (FT) enhances multiple components of physical fitness in basketball players – such as muscle strength, linear speed, cardiovascular endurance, flexibility, balance, and muscular endurance – but yields inconsistent improvements in explosive power, change-of-direction speed, and basketball-specific skills. These inconsistencies were attributed to differences in training duration, frequency, and baseline performance levels. Thus, even in well-studied hearing populations, the mechanisms through which systematic, functionally oriented training translates into sport-specific performance remain unclear. For Deaf athletes, these adaptations may be further influenced by sensory and communication factors, emphasizing the importance of long-term, evidence-based evaluation of training effects.

Overall, available research suggests that Deaf athletes can achieve morphological and motor profiles approaching those of hearing athletes. Yet, to date, no longitudinal studies have documented how these attributes change with sustained training exposure in elite Deaf players. Understanding these processes is essential for optimizing training programs, guiding talent development, and promoting equitable inclusion of Deaf athletes in competitive sport.

Therefore, the present study aimed to:

-

1.

Examine longitudinal changes in the anthropometric, body composition, and motor characteristics of elite Deaf basketball players across three consecutive training years (2019–2021); and.

-

2.

Compare these parameters with those of physically inactive Deaf peers and reference data from hearing athletes.

We hypothesized that:

-

1.

Systematic multi-year training would lead to favorable adaptations in body composition and neuromuscular performance (i.e., increased muscle mass, improved jump height, and stable or enhanced sprint performance) among elite Deaf basketball players.

-

2.

Despite these adaptations, certain performance domains – particularly aerobic endurance and sprint acceleration – would remain more variable and potentially decline during periods of disrupted training continuity, such as those associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

3.

The progressive improvements observed over the three-year period would contribute to narrowing, though not entirely eliminating, the performance gap between Deaf and hearing basketball players reported in the literature.

Materials and methods

Participants

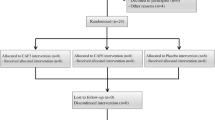

The study included all available male Deaf basketball players from the Polish national team who completed longitudinal anthropometric and performance assessments between 2019 and 2021 (n = 11). Because this represented a complete cohort of a rare athletic population, an a priori power analysis was not feasible. All eligible athletes meeting the inclusion criteria were therefore recruited to maximize the representativeness of this unique sample.

To evaluate the adequacy of the sample, a post hoc estimation of statistical power was conducted based on within-subject effect sizes derived from Friedman’s χ² statistics and corresponding Cohen’s dz values. The required sample size for paired comparisons was estimated using standard equations incorporating the expected effect size, within-subject correlation (r), significance level (α), and statistical power (1–β). Assuming α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and r = 0.5, the number of participants required to detect effects of comparable magnitude ranged from approximately n ≈ 7 for variables showing large effects (e.g., thigh mid-circumference, Kendall’s W = 0.22) to n > 200 for variables with very small effects (e.g., thigh maximum, W = 0.01). Moderate effects (W = 0.11–0.13; e.g., waist or hip circumference) would require 14–25 participants. For performance outcomes, large effects were noted for sprint times (t(0–5 m), t(0–20 m); W = 0.92 and 0.66), indicating that the current sample size provided adequate sensitivity for detecting meaningful within-subject changes in sprint performance. Conversely, small effects in power-related variables (maximum jump power, elevation of the body’s center of mass, and countermovement depth; d = 0.18–0.32) would require approximately n = 77–240 to achieve comparable power. These estimations confirm that the present study was sufficiently powered to detect large effects but underpowered for small ones. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted as exploratory, and the reported effect sizes considered as pilot data to inform future confirmatory research in Deaf athlete populations.

The first testing session took place during a national training camp preceding the 2019 Deaf Basketball World Championships in Lublin, with subsequent assessments conducted during training camps preparing for the 2021 Deaflympic Games (postponed to 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic). National lockdowns in Poland between March 2020 and mid-2021 disrupted organized sports and restricted indoor physical activity, affecting training continuity but not study completion. Deaf sports, operating with limited institutional support, were particularly impacted by these restrictions27.

A total of 11 elite Deaf basketball players met the inclusion criteria (mean age: 26.91 ± 6.27 years; range: 19–38 years; height: 185.92 ± 5.29 cm; body mass: 84.22 ± 7.37 kg). All participants were right-hand dominant, and ten reported right-leg dominance. Inclusion criteria were: (1) confirmed hearing loss > 55 dB in the better ear, in accordance with International Committee of Sports for the Deaf (ICSD) regulations28; (2) continuous membership in the national team throughout all three study years; (3) regular participation in training camps and team practices (minimum three sessions per week); and (4) absence of injuries or neurological disorders within the month preceding testing. Exclusion criteria included: (1) irregular participation in national-team activities; (2) interruptions in training continuity due to illness or injury; or (3) incomplete longitudinal data.

Audiometric testing confirmed mean hearing thresholds of 108 ± 14 dB (right ear) and 94 ± 23 dB (left ear). None of the players used cochlear implants. The athletes had an average of 13.70 ± 4.30 years of competitive experience in sports clubs and 8.30 ± 4.10 years of tenure on the national team.

For comparative purposes, a control group of 15 physically inactive Deaf male students (DS) was recruited from the School and Educational Center for the Deaf in Bydgoszcz (mean age: 21.07 ± 1.62 years; height: 176.50 ± 6.22 cm). This group represented a heterogeneous Deaf population, including individuals with residual hearing and one participant using a cochlear implant. To ensure uniform measurement conditions, the external component of the implant was removed during testing. Inclusion criteria for the control group were: (1) diagnosed moderate-to-profound hearing loss; (2) no history of systematic sports training or competitive activity during the preceding two years, verified by a physical-education teacher; and (3) absence of musculoskeletal or neurological disorders. The control group provided reference data on morphological and motor characteristics typical of non-athletic Deaf individuals, allowing differentiation between training-related and sensory-related effects. Although the control group was younger than the athlete cohort, it provided valuable reference data representing the morphological and motor characteristics of the non-athletic Deaf population. All between-group comparisons were interpreted with caution due to this age difference.

All body composition and anthropometric measurements were conducted in the morning before breakfast. Vertical jump and sprint tests were performed during a training session after 10:00 a.m., with two trials of each test separated by a 3–5-minute recovery period. The Beep Test was conducted the following day. Due to high training demands and limited time during national team camps in 2019 and 2020, coaches did not authorize administration of the Beep Test during those years.

All participants were fully informed about the study procedures and provided written informed consent prior to testing. For participants requiring communication support, a sign-language interpreter assisted in explaining the study aims, procedures, and participant rights to ensure complete understanding. During testing, a strength and conditioning coach was present to supervise all physical performance assessments. To maintain methodological consistency, all measurements were conducted by the same investigator under identical environmental and procedural conditions.

For all continuous variables (anthropometry, body composition, jump and sprint performance), means and standard deviations (X̅ ± SD) were calculated. For categorical variables (e.g., hand and leg dominance), frequencies and percentages were computed. Longitudinal changes between 2019 and 2021 were analyzed using Friedman ANOVA, reporting χ²(df) and Kendall’s W as a measure of effect size. Comparisons between basketball players and inactive Deaf participants (DS) were conducted using Cohen’s d. Test–retest reliability for jumps and sprint measures was evaluated using ICC, Pearson’s correlation (r), standard error of measurement (SEM), and minimal detectable change (MDC95). Correlations between lower-limb explosive power (CMJ Pw_max) and sprint performance (0–5 m) were analyzed with Pearson’s r. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using standard statistical software.

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee (Approval No. 330/2014) with authorization for continuation until the end of 2022 and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements were conducted according to the International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment29. A Siber Hegner anthropometer (Switzerland) and a Gulick tape measure were used. Reference points for circumference and length measurements were carefully marked. Each measurement was taken twice, and the mean value was recorded.

The following anthropometric parameters were measured:

-

Body height [cm]: Measured from the vertex to the base of the feet in an upright position, with the head aligned in the Frankfurt plane.

-

Waist [cm]: Waist circumference was measured horizontally at the narrowest point between the costal margin and the iliac crest.

-

Hip [cm]: Hip circumference was measured at the point of greatest posterior protuberance of the buttocks, with the tape held horizontal.

-

T_MAX [cm]: Maximum thigh circumference was measured with the tape placed perpendicular to the long axis of the thigh, slightly below the gluteal fold, with both limbs evenly loaded.

-

T_MID [cm]: The thigh circumference at mid-length was measured halfway between the trochanter and the lateral condyle of the femur, with the tape placed perpendicular to the long axis.

-

Calf [cm]: Maximum calf circumference, measured horizontally at the greatest girth of the calf muscle, with the participant in a standing position and body weight evenly distributed on both feet. (new paragraph/next line) Additionally, the chest circumference difference (CH_D) [cm] was assessed as a functional parameter. It was calculated as the difference between chest circumference measured at the level of the xiphoid process at maximal inspiration and maximal expiration.

Segmental body composition

Body mass and segmental body composition were assessed using a Tanita BC-418 MA bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with eight tactile electrodes for whole-body and segmental analysis. Measurements were performed in accordance with the standardized procedures described by Kyle et al.30,31 and Szulc32. All assessments were conducted in the morning hours under controlled laboratory conditions, with participants barefoot and wearing light sports clothing. Subjects were instructed to refrain from eating, caffeine consumption, and vigorous physical activity for at least 12 h before testing. Prior to measurement, each participant’s age, sex, and height were entered into the analyzer’s software. Recorded parameters included:

-

Body mass [kg].

-

BMI [kg/m²].

-

FAT%: Percentage of body fat.

-

Fat mass [kg].

-

FFM (Fat-Free Mass) [kg].

-

TRUNK Fat mass [kg]: Fat mass localized in the torso.

-

RL-FFM and LL-FFM [kg]: Fat-free masses in the right and left lower limbs, respectively.

Lower limb power and jump performance

The power output of the lower extremities and the vertical displacement of the body’s center of mass were measured using a force plate (JBA, Zb. Staniak, Poland) integrated with MVJ v.3.4 software (JBA, Poland).

Participants performed three maximal repetitions of each of the following vertical jump tests:

-

Counter-Movement Jump (CMJ): A vertical jump initiated from a standing erect position, preceded by a rapid downward movement (countermovement) involving a back-and-forth arm swing and lowering of the body’s center of mass (COM) before take-off.

-

Akimbo Counter-Movement Jump (ACMJ): A vertical jump performed from an upright stance with hands placed on the hips (akimbo), involving a rapid downward movement (countermovement) and lowering of the body’s COM prior to take-off, with no contribution from the upper limbs.

-

Spike Jump (SPJ): A vertical jump executed after a 3–4 step run-up before take-off. Each jump trial was preceded by a standardized dynamic warm-up, consisting of 5 min of light running, dynamic stretching, and mobility exercises specific to lower-limb activation. Subsequently, participants performed two submaximal familiarization trials to ensure proper technique and reduce intra-individual variability. For the CMJ, participants started from a static upright standing position, with feet shoulder-width apart and hands free to perform a natural arm swing. For the ACMJ, the starting position was identical except that participants were required to keep their hands firmly placed on their hips throughout the entire movement.Upon the examiner’s verbal command combined with a simultaneous visual hand signal (to ensure clear communication for Deaf participants), athletes performed a rapid, self-paced downward countermovement immediately followed by a maximal vertical take-off. The depth of the countermovement was self-selected but a trunk forward lean not exceeding ~ 20° from vertical. Participants were instructed to perform each jump with maximal effort and to land with both feet on the measurement platform. To minimize fatigue effects, a 30-second rest interval was provided between repetitions and a 2-minute rest between jump types. All tests were conducted under identical indoor conditions, on the same measurement platform, and using standardized footwear. The following variables were calculated on the basis of ground reaction force data recorded by the force plate33:

-

Pw_max [W]: Maximum power output during the jump.

-

H_max [m]: Maximum elevation of the body’s center of mass.

-

D_BML [m]: Depth of lowering of the body’s center of mass prior to take-off from the platform.

-

D_SPJ [m]: Depth of lowering of the body’s center of mass after landing in the SPJ, determined from ground reaction force data.

Data for the vertical jump test in 2020 were not collected due to equipment failure, and the next testing session was conducted only after the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted. Because the missingness affected the entire measurement period, no data imputation was performed. Multiple imputation was considered methodologically inappropriate, as it assumes that data are missing at random (MAR). Therefore, analyses for jump-related variables were based solely on the actual measurements obtained in 2019 and 2021.

Speed and sprint performance

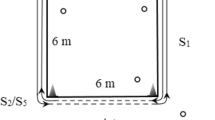

Sprint performance was evaluated using the Fusion Sport SmartSpeed PRO timing system (Fusion Sport, Sumner, QLD, Australia) to measure short-distance acceleration and linear sprint speed. Participants completed two maximal sprints over a 20 m distance, with intermediate timing at 5 m to assess initial acceleration. The starting position was standardized at approximately 50 cm behind the first photocell, allowing athletes to adopt a self-selected, two-point stance. Timing gates were positioned at 0 m, 5 m, and 20 m, and sprint times were automatically recorded with a precision of 0.001 s. Each participant performed two trials, separated by a 3-minute passive recovery period, and the fastest sprint time was retained for further analysis. Prior to testing, all athletes completed a standardized 10-minute dynamic warm-up consisting of jogging, mobility drills, and progressive acceleration runs. All assessments were conducted indoors on a synthetic sports surface under consistent environmental conditions. The same investigator supervised all trials to ensure procedural reliability and measurement consistency.

Cardiorespiratory endurance (Beep Test)

Endurance was evaluated using a 20 m multistage shuttle run (Beep Test) using the Fusion Sport SmartSpeed PRO. Recorded parameters were:

Because of the intensive training schedule of the national team, the Beep Test was administered only in 2021. Standardized instructions and verbal encouragement were provided to maximize participant effort while maintaining safety. Reference values for aerobic capacity (VO₂max = 44 ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹) and endurance performance (distance = 1850 m) were derived from previously published data37, obtained from 12 male university-level basketball players aged 19–22 years attending a sports academy. These reference values were used as normative benchmarks in one-sample t-tests to assess the relative aerobic performance of the Deaf basketball players. The Beep Test was not administered to this group of Deaf students.

Statistical analyses

This study involved longitudinal data collected from the same group of participants over three consecutive years (2019–2021; n = 11). The primary objective was to assess within-subject changes over time. Due to the small sample size and potential deviations from normality, the Friedman test was applied as a nonparametric alternative to repeated-measures ANOVA, accompanied by the Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) to evaluate the consistency of rankings across time points. Bonferroni - adjusted post hoc tests were conducted following significant results to identify year-to-year differences while controlling for Type I error.

In 2020, due to a malfunction of the dynamometry platform, vertical jump tests (CMJ, ACMJ, SPJ) were not performed. For these variables, comparisons between available years (2019 vs. 2021) were conducted using paired-sample t tests or, when assumptions were not met, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. A one-sample t test was used to compare the measured VO₂max and total distance covered with reference values (44 ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹ and 1850 m, respectively).

Effect sizes were interpreted according to standard thresholds:

-

Kendall’s W: ≤ 0.10 (small), 0.10–0.30 (moderate), ≥ 0.30 (strong agreement),

-

η² (eta squared) – 0.01 (small), 0.06 (medium), 0.14 (large).

To evaluate the reliability of sprint and vertical jump measures obtained with the force plate, test–retest analyses were performed38. The following indices were calculated:

-

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): < 0.50 poor, 0.50–0.75 moderate, 0.75–0.90 good, > 0.90 excellent.

-

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r).

-

Standard Error of Measurement (SEM).

-

Minimal Detectable Change (MDC95).

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc., USA), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Missing data and factors affecting data collection

During the longitudinal study (2019–2021), data collection was partially constrained by national-team training schedules and external circumstances. Specifically, the 20 m multistage shuttle run (Beep Test) was not administered in 2019 and 2020 due to coaching priorities related to preparation for the 2019 Deaf Basketball World Championships and the implementation of high-load training programs in 2020. In 2021, the postponement of the Deaflympic Games to 2022 allowed the coaching staff to authorize this demanding endurance test.

For safety reasons, endurance testing was not conducted among the physically inactive Deaf control group, precluding direct comparisons of VO₂max and maximal distance between athletes and non-athletes. Moreover, the age difference between the basketball players (mean 26.91 ± 6.27 years) and the control group (mean 21.07 ± 1.62 years) introduced developmental and training-related disparities that may have influenced anthropometric and performance outcomes.

The study period overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted training routines and competition schedules, particularly in 2020. These contextual factors, including pandemic-related restrictions and variations in training availability, should be considered when interpreting longitudinal changes and between-group comparisons27,39.

Results

Anthropometry

No significant longitudinal changes were observed in the anthropometric variables between 2019 and 2021 (Friedman ANOVA: all p > 0.05; χ² = 0.18–4.91; Kendall’s W = 0.01–0.22). Overall, the athletes’ body dimensions remained stable, indicating the absence of measurable somatic adaptations despite continued training. This pattern aligns with the morphological plateau typically seen in mature, high-performance athletes. Small-to-moderate effect sizes suggest minor fluctuations rather than true developmental change.

Individual responses showed some variability, particularly in thigh mid-circumference (T_MID), where certain athletes exhibited slight gains while others showed minor decreases. This highlights inter-individual differences in adaptation, even when group-level changes are non-significant.

Compared with physically inactive Deaf students (DS), basketball players had slightly higher mean circumferences at most sites, especially in the thigh region. Although these differences were not statistically significant (Cohen’s d = 0.14–0.59, all p > 0.05), moderate effect sizes suggest that regular sports participation may contribute to modest increases in lower-limb muscle girth (Table 1).

The reliability of repeated measurements was confirmed by low coefficients of variation and consistent Kendall’s W values (0.01–0.22), supporting the robustness of the longitudinal dataset. Despite small observed effects, the overall pattern of morphological stability provides a reliable baseline for interpreting subsequent biomechanical and performance outcomes.

Body composition

Across the three competitive seasons (2019–2021), the players’ body composition profiles remained generally stable. No significant longitudinal changes were observed in body mass index (BMI), total body fat percentage (FAT%), fat mass, fat-free mass (FFM), or trunk fat mass (Friedman ANOVA: all p > 0.05; χ² = 0.33–1.27; W = 0.02–0.11). A single significant increase was noted for left-leg fat-free mass (LL-FFM; p = 0.03), with a small-to-moderate effect size (W = 0.33), suggesting minor localized muscular adaptation. Low Kendall’s W values across most variables confirmed strong consistency of repeated measures and indicated that the athletes maintained a stable morphological profile typical of well-trained, physically mature individuals.

Although group-level changes were minimal, individual responses showed some variability. For example, certain players exhibited slight gains in FFM or lower-limb muscle mass, while others remained unchanged or decreased marginally. These inter-individual differences highlight that even in a homogeneous, elite cohort, adaptations to training may vary among athletes.

Compared with physically inactive Deaf students (DS), basketball players had markedly greater total FFM (p < 0.001, d = 2.12) and substantially higher lower-limb muscle mass – right leg (RL-FFM; p = 0.003, d = 1.33) and left leg (LL-FFM; p < 0.001, d = 1.77) – corresponding to very large effect sizes. These differences illustrate the pronounced influence of long-term basketball training on lower-limb musculature, consistent with the sport’s biomechanical demands involving repeated sprinting, jumping, and change-of-direction movements. Conversely, mean FAT% and total fat mass were lower in the basketball group than in DS, though these differences were not statistically significant (all p > 0.05). Nonetheless, the observed trends align with typical sport-specific adaptations arising from sustained endurance and resistance training.

Collectively, these findings indicate that Deaf basketball players maintain a stable, well-developed somatic profile characterized by high muscle mass, particularly in the lower limbs, reflecting the effects of long-term, systematic high-level training (Table 2).

Lower limb power assessments

Deaf basketball players exhibited markedly superior neuromuscular performance compared with physically inactive Deaf students (DS) across all jump types – countermovement jump (CMJ), akimbo countermovement jump (ACMJ), and spike jump (SPJ). They generated significantly higher maximum power output (Pw_max), greater jump height (H_max), and deeper center-of-mass lowering during the preparatory and landing phases (D_BML, D_SPJ) (all p < 0.001), with large to extreme effect sizes (Table 3). These results indicate a distinctly enhanced lower-limb power capacity and different movement strategies compared to non-athletic peers. In the CMJ test, players reached a mean Pw_max of 3362.1 ± 383.3 W, compared to 1900.5 ± 451.6 W in the control group (p < 0.001, d = 3.46). Similarly, in the SPJ, Pw_max was 4353.2 ± 643.6 W versus 2443.2 ± 550.5 W (p < 0.001, d = 3.20). Extremely large differences were also observed for the center-of-mass lowering depth variables (D_BML, D_SPJ; d > 1.0), suggesting that trained athletes utilized deeper eccentric loading and greater energy absorption during jump execution. No significant longitudinal differences were found between 2019 and 2021 for any jump parameters (all p > 0.05), indicating consistent neuromuscular characteristics over time despite the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A moderate, positive, but non-significant correlation was noted between CMJ Pw_max in 2019 and 2021 (r = 0.47, p = 0.15), implying partial preservation of individual power ranking but increased interindividual variability post-pandemic – likely reflecting uneven training access and conditioning continuity. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, test–retest analyses confirmed good-to-excellent reliability for all jump types and parameters (ICC = 0.78–0.97). The highest reliability was observed for Pw_max in SPJ (ICC = 0.97 in 2019; 0.93 in 2021) and H_max in CMJ and SPJ (ICC ≥ 0.91). Relatively low SEM and MDC95 values further demonstrated the precision and stability of repeated measurements. These reliability indices validate the robustness of the assessment protocol and the consistency of athletes’ motor performance across testing sessions.

Overall, Deaf basketball players maintained stable, high-level explosive power capacities over the three-year observation period, distinctly outperforming inactive Deaf peers. Their superior lower-limb strength, jump mechanics, and movement strategy adaptations reflect the neuromuscular demands of elite basketball training and competition.

All parameters showed good-to-excellent reliability (ICC = 0.78–0.97) with strong correlations (r ≥ 0.80) and low SEM/MDC95, confirming high measurement precision and reproducibility. Reliability remained stable across years, underscoring consistent test conditions and motor control in repeated assessments.

Sprint performance

Longitudinal analysis revealed modest but significant within-subject declines in short-distance sprint performance between 2019 and 2021. Both the 0–5 m (χ²(2) = 20.18, p < 0.001, W = 0.92) and 0–20 m sprints (χ²(2) = 14.59, p = 0.001, W = 0.66) showed systematic increases in mean sprint times, indicating consistent slowing over the three-year period (Table 6). Mean times rose from 1.021 ± 0.049 s to 1.106 ± 0.061 s (0–5 m) and from 3.016 ± 0.105 s to 3.127 ± 0.122 s (0–20 m). This pattern likely reflects reduced exposure to sprint-specific training during COVID-19 restrictions rather than true declines in maximal performance capacity.

Despite this small regression, Deaf basketball players consistently outperformed physically inactive Deaf students (DS) at both distances – 0–5 m: p = 0.035, d = − 1.03; 0–20 m: p = 0.019, d = − 1.07 – indicating large effects favoring trained athletes. These results confirm superior acceleration and sprinting ability in elite Deaf basketball players, comparable to hearing athletes of similar competitive level.

Test–retest reliability across all study years was good to excellent (ICC = 0.88–0.97; r = 0.88–0.97) with low SEM (0.016–0.124 s) and MDC₉₅ (0.044–0.344 s), confirming high measurement precision and reproducibility (Table 7). These metrics indicate that observed changes represent true performance variations rather than measurement artifacts.

Correlation analyses further clarified temporal stability. In the 0–5 m sprint, a very strong correlation was observed between 2019 and 2020 (r = 0.91), indicating consistent individual rankings under normal training conditions. Stability declined after the onset of the pandemic (2020–2021: r = 0.84; 2019–2021: r = 0.66, p = 0.027). A similar pattern was observed for the 0–20 m sprint (2019–2020: r = 0.93, p < 0.001; 2020–2021: r = 0.71, p ≈ 0.02; 2019–2021: r = 0.65, p ≈ 0.04), indicating moderate long-term stability and suggesting that COVID-related training disruptions affected inter-individual performance consistency and partially altered ranking order.

Overall, Deaf basketball players maintained sprint capacities significantly higher than inactive Deaf peers, despite minor longitudinal slowing. The findings underscore the resilience of speed-related performance and the athletes’ effective adaptation to prolonged training constraints and external disruptions, highlighting their maintained competitive advantage in acceleration and short-distance sprinting.

Relationship between explosive power and sprint performance

To further explore the relationship between neuromuscular performance and sprint ability, correlation analyses were performed between lower-limb explosive power (CMJ Power_max) and sprint time over 0–5 m. In 2019, a strong and statistically significant negative correlation was found (r = − 0.74, p ≈ 0.01), indicating that athletes with higher CMJ power achieved faster sprint times (i.e., shorter durations). This result reflects a close association between lower-limb power output and short-distance acceleration under regular training conditions. In contrast, in 2021 (after the COVID-19 pandemic), the correlation between Power_max and 0–5 m sprint performance weakened to a moderate level (r = − 0.56, p ≈ 0.08) and did not reach statistical significance. This attenuation suggests that pandemic-related interruptions and reduced access to structured training may have diminished the transfer efficiency between vertical power and sprint acceleration.

Cardiorespiratory endurance

In 2021, the 20 m multistage shuttle run (Beep Test) was performed by nine athletes from the 5 × 5 team. The mean distance covered was 1720.0 ± 398.4 m (range: 1100–2340 m), corresponding to a mean estimated VO₂max of 47.29 ± 6.14 ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹ (range: 37.4–56.5 ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹). Based on Huciński et al.37, the reference VO₂max for amateur basketball players was set at 44 ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹. One-sample t-tests indicated no significant differences from the reference values for VO₂max (t = 1.607, p = 0.147) or distance covered (reference = 1850 m; t = − 0.979, p = 0.356). Endurance measurements were not conducted in inactive Deaf students due to safety considerations, precluding direct group comparisons.

Discussion

This longitudinal study examined anthropometric, body composition, and neuromuscular characteristics of elite Deaf basketball players from the Polish National Team over a three-year preparation period for the 2021 Deaflympics. The study period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused significant training disruptions through national lockdowns between March 2020 and mid-2021, restricting organized sports activities and affecting training continuity. Table 8 summarizes the assessments, measurement years, participant groups, and sample sizes.

Biological significance of anthropometric indicators

Relationships between lower-limb morphology, muscle mass, explosive power, and sprint performance were analyzed in 2019 and 2021. In 2019, thigh circumference (T_MAX) showed a very strong positive correlation with right lower-limb fat-free mass (RL-FFM; r = 0.87, p < 0.01), a moderate positive correlation with maximal jump power (Pw_max; r = 0.63, p = 0.04), and a moderate negative correlation with 0–5 m sprint time (r = − 0.58, p ≈ 0.06). These results suggest that larger and more muscular thighs contribute to higher explosive power and faster short-distance acceleration.

Following COVID-19-related training interruptions, correlations between T_MAX and Pw_max (r = 0.52, p ≈ 0.09) and sprint time (r = − 0.46, p ≈ 0.13) decreased in 2021, although the relationship with RL-FFM remained strong (r = 0.78, p < 0.01). This indicates that structural adaptations in thigh musculature were largely preserved, but functional translation into explosive performance was partially affected, likely due to reduced training specificity, neuromuscular coordination, and potential psychosocial factors such as motivation or training engagement, which were not assessed. Minor declines may also reflect natural aging effects. Differences between Deaf basketball players and physically inactive Deaf students likely reflect long-term training adaptations and greater physical maturity.

Interpretation in context of existing literature

Across three years, body mass, BMI, fat percentage, fat mass, and fat-free mass remained stable, indicating that the national team’s training program effectively maintained morphological profiles despite pandemic-related disruptions24. As no direct records of training volume or subjective athlete responses were collected in 2020–2021, performance fluctuations should be interpreted as contextual rather than causal.

Consistent with prior research in Deaf athletes12,15, basketball players in this study demonstrated substantially higher fat-free mass, lower fat mass, and superior functional performance – lower-limb power, jump height, and sprint speed – relative to inactive peers, with large-to-extreme effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.9–3.5). These outcomes align with findings from hearing basketball players, highlighting that complex, plyometric, and velocity-based training enhances explosive performance12,25,26.

Despite these gains, Deaf athletes remained generally shorter, lighter, and exhibited lower aerobic capacity and slower sprint times than professional hearing players (Table 9). These persistent gaps emphasize the need for system-level support, including qualified strength and conditioning staff, interpreters familiar with sport-specific terminology, technology-assisted feedback, and psychosocial support to optimize training adherence.

Practical implications for training and athlete development

A positive association between knowledge and practice was observed. The biological findings above inform coaching strategies: enhancing performance in Deaf basketball players may require targeted interventions emphasizing explosive strength, sprint acceleration, and aerobic–anaerobic conditioning. Incorporating complex training protocols combining heavy-resistance exercises with high-velocity or plyometric movements may optimize neuromuscular potentiation. Individualized programs considering anthropometric constraints and emphasizing technical and tactical skill development are recommended, especially when integrating Deaf athletes into higher-level competitions. Continuous biomechanical monitoring and athlete feedback, including subjective perception of training load, can inform adaptive adjustments to ensure training intensity and volume match each athlete’s capacity.

Limitations and caveats

This study has several limitations:

-

1.

Small sample size (n = 11) limits statistical power and external validity; results are exploratory.

-

2.

Malfunction of the dynamometric platform in 2020 disrupted vertical jump data, highlighting the need for redundant measurement systems in future studies.

-

3.

Absence of endurance testing in 2019–2020 reduces temporal consistency; comparisons across years should be interpreted cautiously.

-

4.

The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on performance outcomes, while evident, remains contextual rather than causally established due to the observational nature of this study.

-

5.

Endurance comparisons with physically inactive Deaf students were omitted for safety reasons, limiting between-group analysis.

-

6.

Comparisons with hearing athletes relied on published data with heterogeneous methods, competitive levels, and demographics, limiting direct inference.

-

7.

No data on psychological or subjective athlete responses were collected, which could influence training adherence and performance outcomes.

Study aims and hypotheses

The primary aim was to examine longitudinal changes in anthropometric, body composition, and motor characteristics of elite Deaf basketball players during three years of preparation for the Deaflympics. The secondary aim was to compare these parameters with inactive Deaf peers and hearing basketball players.

Hypothesis 1

Multi-year systematic training would enhance body composition and neuromuscular performance. Partially supported – players maintained or slightly improved body composition and jump performance, indicating sustained neuromuscular capacity with continuous structured training.

Hypothesis 2

Aerobic endurance and sprint performance would exhibit greater variability during COVID-19 restrictions. Supported – sprint performance declined modestly, reflecting sensitivity of high-velocity movements to reduced training load and sport-specific drills.

Hypothesis 3

Training would reduce, but not eliminate, performance gaps with hearing athletes. Partially supported – body composition and explosive power were competitive, but aerobic capacity and sprint speed remained lower. Differences may reflect physiological and contextual factors, including limited coaching access and communication barriers.

These outcomes confirm the adaptive potential of Deaf athletes under systematic training while highlighting the need for optimization in domains sensitive to interruptions.

Future research directions

Future studies should:

-

1.

Recruit larger, multinational Deaf cohorts with stratification by age, sex, and competitive level to enhance generalizability and allow robust cross-cultural and developmental comparisons.

-

2.

Design longitudinal interventions combining resistance, plyometric, and high-intensity interval training, specifying training frequency, intensity, and progression to determine the most effective protocols for improving explosive power, sprint speed, and aerobic capacity in Deaf athletes.

-

3.

Investigate sensory limitations and communication modalities, such as visual vs. tactile feedback, and their impact on neuromotor adaptations, learning rates, and training responsiveness.

-

4.

Include matched hearing athlete control groups under identical testing protocols to enable direct comparisons of training adaptations, recovery kinetics, and performance determinants.

-

5.

Integrate technology-assisted feedback tools, e.g., wearable motion sensors, real-time visual cues, and video-based kinematic analysis, to optimize skill acquisition, monitor individual training loads, and assess subjective perceptions of effort and fatigue.

-

6.

Examine psychological and subjective responses to structured training, including motivation, perceived exertion, and engagement, to identify barriers and facilitators of high-performance adaptation.

-

7.

Implement multi-year follow-ups to track performance trajectories, injury incidence, and retention of adaptations, supporting evidence-based, inclusive training guidelines and promoting sustainable high-performance outcomes in Deaf athletes.

Future studies with larger multi-center samples could further validate these findings and enhance their applicability across diverse Deaf athlete populations.

Conclusion

This longitudinal study presents the first multi-year (2019–2021) characterization of anthropometric and physical performance profiles in elite Deaf basketball players. The findings demonstrate that structured, systematic training effectively maintains body composition and neuromuscular performance, while also highlighting specific vulnerabilities in sprint acceleration, which is particularly sensitive to training interruptions such as those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compared with physically inactive Deaf peers, the athletes showed superior fat-free mass, lower body fat, and enhanced jumping and sprinting abilities, confirming the benefits of sustained, long-term athletic engagement. Performance gaps relative to hearing athletes remained, particularly in explosive power and aerobic capacity, emphasizing the need for tailored training strategies to bridge these differences.

The study’s longitudinal, multi-measure approach provides actionable insights for coaches and practitioners, enabling individualized athlete monitoring and performance profiling. Short-sprint and high-intensity conditioning should be prioritized, especially following periods of disrupted preparation, while structured interventions targeting endurance and neuromuscular power can help optimize competitive readiness.

Beyond basketball, these results have broader implications for Deaf sport and other contexts where athletes face sensory or environmental constraints. They underscore the importance of inclusive, evidence-based training programs that combine physiological, technical, and psychosocial considerations to support high-performance development. These findings offer the first multi-year dataset for Deaf basketball athletes, supporting evidence-based training design.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Jonsson, O. & Gustafsson, D. Spirometry and lung function in children with congenital deafness. Acta Paediatr. 94, 723–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01971.x (2005).

Tuncer, D. & Gurses, N. The effects of core stabilization excercises on respiratory muscle strength, respiratory functions, and postural control in children with hearing loss: a randomized controlled trial. Ear Hear. 45 (2), 306–315 (2024).

Carpenter, M. G. & Campos, J. L. The effects of hearing loss on balance: A critical review. Ear Hear. 41, 107S–119S (2020).

Greenwald, G. B. & Gurley, J. M. Balance and vestibular function. NeuroRehabilitation 32, 433–435 (2013).

Martin, W., Jelsma, J. & Rogers, C. Motor proficiency and dynamic visual acuity in children with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 76 (10), 1520–1525 (2012).

Schwab, B. & Kontorinis, G. Influencing factors on the vestibular function of deaf children and adolescents–evaluation by means of dynamic posturography. Open. Otorhinolaryngol. J. 5, 1–9 (2011).

Carpenter, M. G. & Campos, J. L. The effects of hearing loss on balance: a critical review. Ear Hear. 41, S107–S119. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000929 (2020).

Veiskarami, P., Roozbahani, M., Saedi, S. & Ghadampour, E. Comparing fine and gross motor development in normal hearing children, rehabilitated, and non-rehabilitated hearing-impared children. Auditory Vestib. Res. 31 (3), 208–217 (2022).

Nosko, M., Troianovska, M., Ciślicka, M. & Stancu, M. Motor skill development in schoolchildren with hearing impairments during physical education in general secondary schools. Pedagogy Phys. Cult. Sports. 29 (5), 379–388 (2025).

Chilosi, A. M. et al. Neurodevelopmental disorders in children with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss: a clinical study. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 52 (9), 856–862 (2010).

López-Crespo, G., Daza, M. T. & Méndez-López, M. Visual working memory in deaf children with diverse communication modes: improvement by differential outcomes. Res. Dev. Disabil. 33, 362–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.022 (2012).

Szulc, A. M. & Buśko, K. Effect of regular soccer training on morphological and motor characteristics of deaf girls aged 14–18 years: a comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 21523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08025-y (2025).

Rajendran, V. & Roy, F. G. Comparison of health related quality of life of primary school deaf children with and without motor impairment. Ital. J. Pediatr. 36, 75 (2010).

Maszczak, T. Rozwój fizyczny i sprawność fizyczna dzieci głuchych w Polsce [Physical development and fitness of deaf children in Poland]. Józef Piłsudski Univ of Physical Education in Warsaw. Ph.D thesis, p.166 (1974).

Szulc, A. M. Morphological and Motor Characteristics of Male and Female Polish Deaf National Team Football Players. Kazimierz Wielki Univ. Press, p. 114 (2020).

Szulc, A. M. & Sandurska, E. Deaflympic games 2017 vs. Olympic games 2016 – male swimming competition, analysis of the age, reaction time, speed and final time. Acta Kinesiol. 18, 12–19 (2024).

Szulc, A. M. & Sandurska, E. Deaf and hearing basketball National teams at the 2019 world championships: discriminant analysis of game-related statistics between the winning and the defeated. Acta Kinesiol. 15 (1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.51371/issn.1840-2976.2021.15.S1.12 (2020).

Szulc, A. M. World Deaf Basketball Championships 2015 and 2019 and FIBA World Cup Comparative Analysis of Individual Statistics. Kazimierz Wielki Univ. Press, p. 244 (2021).

Milašius, K., Rūtenis, P., Rūta, D. & Algimantas, S. Body and functional capacity of Lithuanian deaf basketball team players and characteristics of game indices. Balt J. Sport Health Sci. 4 (95), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.33607/bjshs.v4i95.133 (2014).

Makaracı, Y., Soslu, R., Özer, Ö. & Uysal, A. Center of pressure-based postural sway differences on parallel and single leg stance in olympic deaf basketball and volleyball players. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 17 (6), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.2142558.279 (2021).

Soslu, R., Özer, Ö., Uysal, A. & Pamuk, Ö. Deaf and non-deaf basketball and volleyball players’ multi-faceted difference on repeated countermovement jump performances: height, force and acceleration. Front. Sports Act. Living. 4, 941629. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.941629 (2022).

Cobanoglu, G. et al. Static balance and proprioception evaluation in deaf National basketball players. Balt J. Health Phys. Act. 13 (1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.29359/BJHPA.13.1.02 (2021).

Graib, G., Qablan, S. A. & Aldmour, H. A. Effect of some personal attributes – anxiety and tension – on the level of performance of basketball aiming skills for deaf players in Jordan. Eur Sci. J. 8 (6), 100–119 (2012).

Paulauskas, R. & Paulauskienė, R. Development of repeated sprint ability in Lithuanian deaf basketball players. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference on Kinesiology; May 10–14; Opatija, Croatia; editors-in-chief Dragan Milanović et al.; Zagreb: University of Zagreb. (2017).

Suner-Keklik, S. et al. Comparison of shoulder muscle strength of deaf and healthy basketball players. Int. J. Disabil. Sports Health Sci. 3 (1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.33438/ijdshs.694943 (2020).

Cao, S., Liu, J., Wang, Z. & Geok, S. K. The effects of functional training on physical fitness and skill-related performance among basketball players: a systematic review. Front. Physiol. 15, 1391394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1391394 (2024).

Ważny, K. Legal aspects of sport during the COVID-19 pandemic - case study of Poland in the global context. J. Phys. Educ. Sport. 21 (2), 1276–1283 (2021).

Deaflympics Accessed September 29,. Deaflympics Regulations. Avaible at: (2025). https://www.deaflympics.com/icsd/deaflympics-regulations

Petri, F., Campa, F., Holway, F., Pengue, L. & Arrones, L. ISAK-based anthropometric standards for elite male and female soccer players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 12, 69 (2024).

Kyle, U. G. et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis – Part I: review of principles and methods. Clin. Nutr. 23 (5), 1226–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2004.06.004 (2004).

Kyle, U. G. et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis – Part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin. Nutr. 23 (6), 1430–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2004.09.012 (2004).

Szulc, A. M. Biofizyczne i środowiskowe Podstawy analizy składu ciała metodą BIA. J. Health Sci. 3, 410–427 (2013).

Gajewski, J., Michalski, R., Buśko, K., Mazur-Różycka, J. & Staniak, Z. Countermovement depth – a variable which clarifies the relationship between the maximum power output and height of a vertical jump. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 20 (1), 127–134 (2018).

Altmann, S. et al. Assessing maximal sprinting speed in soccer - criterion validity of commonly used devices. Sci. Med. Footb. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2024.2441321 (2024).

Léger, L. A. Lambert. J. A maximal multistage 20-m shuttle run test to predict VO2max. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 49 (1), 1–12 (1982).

Mayorga-Vega, D., Aguilar-Soto, P. & Viciana, J. Criterion-related validity of the 20-m shuttle run test for estimating cardiorespiratory fitness: a meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. Med. 14 (3), 536–547 (2015).

Huciński, T. & Tymański, R. Smul’skij, V. Factors of the structure of anaerobic–aerobic productivity of basketball players at the stage of special basic Preparation. Pedagog Psychol. Med. -Biol Probl. Phys. Train. Sport. 8, 175–178 (2009).

Stachelski, R. A. et al. Therapeutic exercise in plantar fasciitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 14 (1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.32098/mltj.01.2024.04 (2024).

Jurecka, A., Skucińska, P. & Gądek, A. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic on physical activity, mental health and quality of life in professional athletes-a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (17), 9423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179423 (2021).

Chaouachi, A. et al. Lower limb maximal dynamic strength and agility determinants in elite basketball players. J. Strength. Cond Res. 23 (5), 1570–1577. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a4e7f0 (2009).

Cabarkapa, D., Krsman, D., Cabarkapa, D. V., Philipp, N. M. & Fry, A. C. Physical and performance characteristics of 3 × 3 professional male basketball players. Sports 11 (1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11010017 (2023).

Alemdaroğlu, U. The relationship between muscle strength, anaerobic performance, agility, sprint ability and vertical jump performance in professional basketball players. J. Hum. Kinet. 31, 149–158 (2012).

Cabarkapa, D. et al. Comparison of vertical jump and sprint performances between 3×3 and 5×5 elite professional male basketball players. Front. Sports Act. Living. 6, 1394739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2024.139473911 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all Polish Deaf Sport Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. S conceived the study; A. S. collected the data; (A) S. and I. (B) analyzed the data and wrote the initial manuscript draft; I.B. and A. S. contributed to the draft updates. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The research protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee (Approval No. 330/2014, dated April 29, 2014) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szulc, A.M., Balatoni, I. Longitudinal anthropometric and physical performance adaptations in the Polish Deaf National basketball team during a three-year preparation for the deaflympics. Sci Rep 16, 4516 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34693-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34693-x