Abstract

In this study, we introduce a coupled fractional system consisting of two fluctuating-mass oscillators with time delay and investigate their collective resonant behaviors. First, we achieve complete synchronization between the average behaviors of these oscillators. We then derive the exact analytical expression for the output amplitude gain, and based on this, we observe generalized stochastic resonance (GSR) in the system. We further examine how GSR behavior depends on system parameters, demonstrating that coupling strength, fractional order, and time delay are crucial in facilitating and optimizing its intensity. Finally, numerical simulations are conducted to validate the analytical results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stochastic resonance (SR) is a fascinating and counterintuitive phenomenon in nonlinear physics, where noise can enhance a system’s sensitivity to weak signals under certain conditions. Initially proposed by Benzi et al.1 to explain Earth’s glacial cycles, SR has since gained widespread attention in fields like neuroscience, biology, information theory, and economics2,3. Over time, research has challenged the traditional belief that nonlinearity, periodic signals, and noise are essential for SR4, leading to increased exploration of SR in linear systems influenced by multiplicative noise5,6,7,8,9. The concept of SR has also evolved. While classical SR describes a non-monotonic relationship between the signal-to-noise ratio and noise intensity, generalized stochastic resonance (GSR), introduced by Gitterman9, refers to a non-monotonic dependence of output signals (or functions like moments and autocorrelation) on noise characteristics. For instance, Ref.10 demonstrates that the transport speed of the two-headed molecular motor depends nonmonotonically on both the fractional order and the coupling factor, indicating the emergence of GSR. Importantly, the simulation results reveal inverse transport in the overdamped fractional coupling Brownian motor model, a phenomenon not observed in the conventional Brownian motor. Additionally, Refs.11,12,13 have developed the fault diagnosis methods leveraging the GSR mechanism in the context of a linear oscillator.

Advancements in experimental techniques have enabled the observation of anomalous diffusion processes across various fields14,15,16,17. For instance, Min et al.18 showed that the memory kernel follows a power-law decay within the generalized Langevin equation (GLE) framework. Beyond the GLE, numerous fractional oscillator (FO) models19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 have been devised, where fractional calculus captures long memory and long-range dependencies. These models have revealed a range of intriguing phenomena, including memory-induced inverse transport19, memory-enhanced energetic stability20, memory-induced SR21,22 and superharmonic SR23, among various other phenomena.

In viscoelastic media, random collisions and adhesions of surrounding molecules induce fluctuations in a Brownian particle’s mass6, leading to the development of linear FO models with mass fluctuation28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Specifically, Refs.28,29,30 examine the SR phenomena triggered by dichotomous, trichotomous, and tempered Mittag-Leffler noise, respectively, while Refs.31,32 delve into SR induced by signal-modulated noise. Additionally, Ref.33 focuses primarily on the influence of time delay on resonance behavior. These models have shown that mass fluctuations, combined with system memory, diversify SR phenomena.

Since particles are rarely isolated in real-world systems, coupled models are essential to accurately describe systems with finite or infinite coupled elements35,36,37. Recently, Yang et al.36 conducted an investigation into SR and synchronization of globally coupled systems, utilizing the exact steady-state solutions and related stability criteria. Following this, Zhong et al.37 defined the mean field, obtained the synchronization behavior, and studied the collective SR behavior of globally coupled fractional Langevin equations. Consequently, within the context of variable mass, researchers are increasingly intrigued by the exploration of SR behaviors in coupled fractional systems that exhibit mass fluctuations38,39. For example, Yu et al.38 achieved the complete synchronization, and investigated the SR of two coupled fractional harmonic oscillators featuring a dichotomous fluctuating mass. Similarly, Lin et al.39 introduced a model of two coupled oscillators with fluctuating masses and a tempered Mittag-Leffler memory kernel, exploring their collective resonant behaviors. Collectively, these studies have revealed that both coupling strength and fractional order significantly impact SR behavior, playing a pivotal role in modulating SR phenomena.

Considering the finite transmission speeds of matter, energy, and information, time delay is also crucial in dynamic systems within complex environments40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Recently, there has been an in-depth investigation into the effects of time delay on the GSR phenomena in FO models, specifically focusing on random mass33, random damping49,51, and random frequency52. Moreover, it is imperative to further explore SR in coupled systems with time delay and to comprehend its effects. He et al.53 studied collective resonant behavior in coupled time-delayed fractional oscillators with fluctuating frequencies. However, the combined effects of time delay and mass fluctuation in coupled fractional systems have been largely overlooked.Actually, the Brownian particles coupled in viscoelastic medium possess a variable mass as mentioned earlier, at the same time, and are simultaneously subjected to an external potential force that incorporates a time delay. To address this, we introduce a novel model of coupled fractional oscillators with mass fluctuation and time delay, and investigate their collective resonant behaviors through theoretical analysis and numerical simulations.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In “System model” section, we introduce the fractional model of coupled oscillators with time delay. “Analytical results” section derives complete synchronization and presents the analytical expression for the steady-state output amplitude. “Collective resonant behaviors” section discusses the analytical results, and “Numerical simulations” section presents the numerical simulations. Finally, “Conclusion” section concludes with a summary.

System model

Fluctuating-mass fractional oscillator with time delay

Considering a Brownian particle in viscoelastic medium, the particle’s variable mass can be formulated as \(m(t) = m[1 + \xi (t)]\). In such a scenario, the motion of particle can be described by the fractional Langevin equation (FLE)6:

Furthermore, in the simplest linear case, the fractional oscillator with fluctuating mass and time delay, can be described by the following FLE33:

where x(t) denotes the particle’s displacement at time t. m is mass of the particle, \(\gamma\) is the damping coefficient, \(\omega ^2\) represents the system’s inherent frequency, \(\tau\) is the time delay, and A and \(\Omega\) are the amplitude and frequency of the external driving force, respectively. Here, \(\xi (t)\) signifies the particle’s mass fluctuation, whereas \(\zeta (t)\) represents the internal system noise. The viscous damping force associated with the memory effect is defined by the fractional derivatives expressed in the \(\alpha\)-order Caputo form:

The mass fluctuation \(\xi (t)\) is modeled as symmetric dichotomous noise, where \(\xi (t)\) takes two values \(\{-\sigma ,\sigma \}\) with equal probabilities \(P_\textrm{s}(-\sigma ) = P_\textrm{s}(\sigma ) = 0.5\). Its statistical properties are given by:

where \(\lambda\) is the correlation rate and \(\sigma ^2\) represents the noise intensity. To ensure the mass m(t) remains positive, the noise intensity is constrained to \(0 < \sigma ^2 < 1\).

The internal noise \(\zeta (t)\) is modeled as fractional Gaussian noise (fGn) and follows the generalized second fluctuation-dissipation theorem54:

where \(\kappa _\textrm{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature. Given that \(\xi (t)\) and \(\zeta (t)\) arise from different physical origins, they are assumed to be uncorrelated:

Coupled fluctuating-mass fractional oscillators with time delay

This paper investigates a system of two coupled Brownian particles exhibiting adhesive behavior in an external time-delayed potential field, given by \(U(x) = \omega ^2 x^2(t - \tau )/2\), \(i = 1,2.\) Assuming that the oscillators are linearly connected, we further explore their dynamics under the fluctuating-mass regime. Specifically, we mathematically describe the behavior of these coupled fractional oscillators, incorporating time delay and a periodic driving force, as follows:

where \(x_i(t)\) denotes the displacement of the ith particle at time t, \(\varepsilon\) represents the coupling strength of the linear coupling forces \(\pm \varepsilon [x_2(t) - x_1(t)]\), and the remaining parameters are defined in accordance with Eq. (2). According to the above-mentioned physics background, the mass fluctuations \(\xi _1(t)\) and \(\xi _2(t)\) are reasonably supposed to be uncorrelated, i.e., \(\langle \xi _i(t)\xi _j(t')\rangle = \delta _{ij}\sigma ^2\textrm{e}^{-\lambda |t-t'|}\), \(i,j = 1,2\). Additionally, the internal Gaussian noises \(\zeta _i(t)\) and the external multiplicative noises \(\xi _j(t)\) are supposed to be uncorrelated, i.e., \(\langle \zeta _i(t)\xi _j(t')\rangle = 0\), \(i,j = 1,2\), for them to have different origins. It is noteworthy that, in the case when \(\tau = 0\) and \(0 < \alpha \le 1\), our model-described by Eq. (6) simplifies to a system of two coupled fractional oscillators with fluctuating mass, driven by a periodic cosine source. This particular scenario has been previously studied by Yu et al.38. Furthermore, when \(\varepsilon = 0\), our model transforms into a fractional time-delayed oscillator with mass fluctuation, a particular scenario that was investigated by Tian et al.33. Additionally, when \(\varepsilon = 0\), \(\tau = 0\) and \(\alpha = 1\), our model further simplifies to the conventional linear oscillator with mass fluctuation, a scenario that was previously studied by Gitterman and Shapiro6.

To derive a time-delay-free equivalent system, we perform an O(\(\tau ^2\)) Taylor expansion around \(\tau = 0\) for the term \(x_i(t - \tau )\), yielding the following approximations for the fractional Langevin equations:

Equation (7) provide an approximation to Eq. (6) in cases where the time delay is small.

In the following section, we will explore the complete synchronization between the average behavior of the coupled fractional oscillators with fluctuating mass and time delay. Additionally, we will derive the first-order moment of the system’s stationary-state response analytically.

Analytical results

Complete synchronization

To investigate the collective resonant behaviors of the two coupled fluctuating-mass fractional oscillators with small time delays described by Eq. (6), it is crucial to determine whether the average behaviors of the two particles are synchronous. This requires computing \(\langle x_1(t) - x_2(t)\rangle\). In our model, \(\xi _1(t)\) and \(\xi _2(t)\) represent symmetric dichotomous noises, while \(x_1(t)\) and \(x_2(t)\) are functions of these noises. As a preliminary step, we employ the well-known Shapiro-Loginov procedure55 and its generalized forms38:

These formulas play a pivotal role in the subsequent calculation process.

Next, we obtain the following by subtracting Eq. (7b) from Eq. (7a):

Next, we perform three distinct operations on Eq. (12): (I) averaging with respect to the noise, (II) multiplying by \(\left( \xi _1(t) + \xi _2(t)\right)\) and subsequently averaging, and (III) multiplying by \(\xi _1(t)\xi _2(t)\) followed by averaging. Throughout these operations, we employ the Shapiro-Loginov formulas provided in Eqs. (8)–(11), which allow us to derive the following three equations:

and

Furthermore, we multiply Eqs. (7a) and (7b) by \(\xi _1(t)\) and \(\xi _2(t)\), respectively, and then subtract the two resulting equations from each other. Next, we compute the average of this newly derived equation and once again utilize the Shapiro-Loginov formulas provided in Eqs. (8)–(11). Through these steps, we obtain

At this stage, we have derived a set of closed equations (Eqs. 13–16) involving four new variables: \(y_1 \triangleq \langle x_1(t) - x_2(t)\rangle\), \(y_2 \triangleq \langle \xi _1(t)x_1(t) - \xi _2(t)x_2(t)\rangle\), \(y_3 \triangleq \langle \xi _2(t)x_1(t) - \xi _1(t)x_2(t)\rangle\), and \(y_4 \triangleq \langle \xi _1(t)\xi _2(t)(x_1(t) - x_2(t))\rangle\). Using Laplace transform to the above closed equations, we obtain

where \(Y_i(s) = \mathscr {L}(y_i(t)) = \int _0^{+\infty }y_i(t)\textrm{e}^{-st}\textrm{d}t\), \(i = 1,\cdots ,4\), and the related coefficients are detailed in “Appendix A” for reference.

The solutions of Eq. (17) can be presented as

Applying the inverse Laplace transformation technique, we obtain

where \(H_{ij}(s)\) and \(H_{ik}(s)\) are the Laplace transforms of \(h_{ij}(t)\) and \(h_{ik}(t)\), respectively, for \(i,j,k = 1,\cdots , 4\). In the long-time limit as \(t \rightarrow +\infty\), the functions \(h_{ij}(t)\) and \(h_{ik}(t)\), for \(i,j,k = 1,\cdots ,4\) tend to zero only if

In this paper, we presume that condition (20) is satisfied. Consequently, the influence of the initial conditions \(y_i(0), \dot{y}_i(0)\) progressively vanishes as \(t \rightarrow +\infty\). Hence, the asymptotic form of \(y_i(t)\), for \(i = 1,\cdots ,4\), can be expressed as follows:

which can be rewritten as

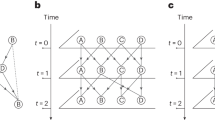

The equations denoted as Eq. (22) indicate that, in the long-time region, the average behaviors of the two particles become completely synchronous. Furthermore, Eq. (20) is interpreted as the synchronism condition, which is illustrated in the parameter set \(\tau -\alpha\) in Fig. 1, where the blue and white regions are delineated to differentiate between synchronism and asynchronism. This is one of the primary findings of this paper. Additionally, the results expressed in Eq. (22) demonstrate that, in the long-time limit, the average of the mean field is equivalent to the average displacement of any single particle. Specifically, \(\langle (x_1(t) + x_2(t))/2\rangle _{\textrm{as}} = \langle x_1(t) \rangle _{\textrm{as}} = \langle x_2(t)\rangle _{\textrm{as}}\). This conclusion validates the appropriateness of studying the mean field through the averages \(\langle x_i(t)\rangle\), \(i = 1,2\). Therefore, in the following subsection, we focus our analysis solely on the stationary state response of the first particle, \(\langle x_1(t)\rangle _{\textrm{as}}\), which represents another key result of this paper.

First-order moment of system stationary state response

To analyze the stationary state response of the coupled time-delayed system described by Eq. (6), we perform a series of four distinct operations on Eq. (7a): (I) averaging with respect to the noise, (II) multiplying by \(\xi _1(t)\) and averaging, (III) multiplying by \(\xi _2(t)\) and averaging, and (IV) multiplying by \(\xi _1(t)\xi _2(t)\) and averaging. Subsequently, we employ the concept of “complete synchronization,” as presented in Eq. (22), along with the Shapiro-Loginov formulas detailed in Eqs. (8)–(11). By doing so, we derive a set of closed equations that incorporate four new variables:

where \(z_1 \triangleq \langle x_1(t)\rangle\), \(z_2 \triangleq \langle \xi _1(t)x_1(t)\rangle\), \(z_3 \triangleq \langle \xi _2(t)x_1(t)\rangle\), \(z_4 \triangleq \langle \xi _1(t)\xi _2(t)x_1(t)\rangle\). By using the Laplace transform to Eq. (23), we obtain

where \(Z_i(s) = \mathscr {L}(z_i(t)) = \int _0^{+\infty }z_i(t)e^{-st}\textrm{d}t\), \(i = 1,\cdots ,4\), and the related coefficients are detailed in “Appendix B” for reference.

Although the solutions to Eq. (24) can be uniformly obtained, it is sufficient to focus on \(Z_1(s)\) in the long-time limit to derive the stationary state response of the system, which is given by

where

Applying inverse Laplace transform to Eq. (25), we obtain

where \(h_{1}(t)\), \(h_{1m}(t)\) and \(h_{1n}(t)\) respectively represents the inverse Laplace transform of \(H_{1}(s)\), \(H_{1m}(s)\) and \(H_{1n}(s)\), \(m,n = 1,\cdots ,4\). Similarly, when condition is met as described below:

the functions \(h_{1m}(t)\) and \(h_{1n}(t)\), for \(m,n = 1,\cdots ,4\) approach zero, as \(t \rightarrow \infty\). Furthermore,the influence of the initial conditions on \(\langle x(t)\rangle _\textrm{as}\) will vanish. In this paper, we assume that the conditions (20) and (27) are satisfied. Consequently, \(\langle x(t)\rangle _\textrm{as}\) can be asymptotically expressed in a simplified form:

where \(A_\textrm{as}\) and \(\varphi _\textrm{as}\) represent the amplitude and phase shift of \(\langle x(t)\rangle _\textrm{as}\), respectively. More specifically, \(A_\textrm{as}\) and \(\varphi _\textrm{as}\) can be written as

and

where j denotes the imaginary unit, and the corresponding coefficients are detailed in “Appendix C” for reference.

Finally, we define the output amplitude gain (OAG), denoted as G, which is expressed as

In the upcoming section, we will explore and discuss the collective resonant behaviors of the system.

Collective resonant behaviors

. In this section, we focus on analyzing the collective resonant behaviors of the two coupled fractional fluctuating-mass oscillators with time delay, specifically in terms of OAG G (see Eq. 31). Our primary emphasis is on the synergistic effects of the coupling strength \(\varepsilon\), fractional order \(\alpha\), time delay \(\tau\), and noise parameters (\(\sigma ^2,\lambda\)) on the non-monotonic resonant behaviors, referred to as GSR behaviors.

GSR phenomena of \(G(\Omega )\): (a) parameter set \(\alpha\)–\(\gamma\) without time delay \(\tau = 0\); (b) parameter set \(\alpha\)–\(\gamma\) with time delay \(\tau = 0.1\); (c) maximal extremum in parameter set \(\alpha -\gamma\) with time delay \(\tau = 0.1\) (yellow represents maximal extremum 3, whereas blue signifies 0); (d) \(G(\Omega )\) for different \(\tau\) with \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\alpha = 0.5\); (e) \(G(\Omega )\) for different \(\alpha\) with \(\gamma = 0.2\), \(\tau = 0.1\); (f) \(G(\Omega )\) for different \(\gamma\) with \(\alpha = 0.3\), \(\tau = 0.1\). The other parameters are set as \(m = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\varepsilon = 1.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.5\), \(\lambda = 0.5\).

Firstly, we investigate the GSR behaviors of \(G(\Omega )\) across varying values of \(\gamma\), \(\alpha\) and \(\tau\). In Fig. 2, we present the parameter set \(\gamma - \alpha\) where GSR phenomena of \(G(\Omega )\) emerge, alongside the corresponding curves of \(G(\Omega )\) at selected representative points within this parameter set. In Fig. 2a, the unshaded region signifies the area where the GSR phenomenon is not possible, while the shaded regions indicate where GSR phenomena of \(G(\Omega )\) occur. Notably, one peak and two peaks appear in the curves of \(G(\Omega )\) in the light and dark gray regions, respectively.

When comparing Fig. 2a (\(\tau = 0\)) with Fig. 2b (\(\tau = 0.1\)), it becomes evident that the inclusion of time delay introduces more diverse and intricate dynamics, including the emergence of triple-peak GSR phenomena within the black region. The time delay in the external potential field force, denoted as \(\omega ^2 x_i(t - \tau )\), for \(i = 1,2,\) introduces nonlinearity into the system, thereby generating complex dynamical behaviors. Moreover, Fig. 2c displays the maximal extremum under the same parameters as in Fig. 2b. As observed, the maximal extrema exhibit a decreasing trend with increasing \(\gamma\), highlighting the dampening effect of \(\gamma\) on the GSR intensity. Intuitively, an increase in \(\gamma\) results in a corresponding increase in the viscous damping force \(\gamma \hspace{0.05cm} _0^C D_t^{\alpha } x_i(t)\), leading to a weakening of the GSR intensity.

In Fig. 2d, we illustrate an example using the point \(\alpha = 0.5\) and \(\gamma = 1\), corresponding to the single-peak GSR region depicted in Fig. 2a and the double-peak GSR region shown in Fig. 2b, respectively. As \(\tau\) increases, we observe an increase in the peak value along with a slight rightward shift in the peak position. Indeed, a larger value of \(\tau\) indicates a more pronounced memory effect in the time-delayed system. Consequently, energy accumulates due to this memory effect, leading to an enhancement of the GSR intensity as \(\tau\) increases. To delve deeper into our analysis, we select \(\gamma = 0.2\) (marked by a vertical red line) and \(\alpha = 0.3\) (marked by a horizontal red line) from Fig. 2b as representative cases. We then analyze the effects of \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) on \(G(\Omega )\) in Fig. 2e,f, respectively. As \(\alpha\) (or \(\gamma\)) increases, the GSR patterns transition from triple-peaks GSR to single-peak GSR. As expected, a larger damping term leads to a reduction in the maximum peak of \(G(\Omega )\). These results align with the observations made in Fig. 2b,c.

In the coupled time-delayed fractional system described by Eq. (6), the two particles experience a pair of interaction forces \(F_{1,2} = \pm \varepsilon (x_2 - x_1)\), known as “coupling forces”. These forces, \(F_1\) and \(F_2\), are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction, compelling the two particles to move toward each other. As \(\varepsilon\) approaches zero, the coupling forces gradually diminish, and the particles behave independently. Conversely, when \(\varepsilon\) attains a sufficiently large value \(\varepsilon ^{*}\), \(F_1\) and \(F_2\) become significant, causing the particles to move in unison (see Fig. 3a).

(a) The coupling force on the two particles; (b) \(G(\varepsilon )\) for different \(\alpha\) with \(\tau = 0.1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\Omega = 1.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.5\), \(\lambda = 0.1\); (c) \(G(\varepsilon )\) for different \(\tau\) with \(\alpha = 0.5\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\Omega = 1.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.5\), \(\lambda = 0.1\); (d) \(G(\varepsilon )\) for different \(\sigma ^2\) with \(\alpha = 0.5\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.5\), \(\Omega = 0.8\pi\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.04\), \(\lambda = 0.1\).

Intuitively, there may exist an optimum \(\varepsilon\) between these two scenarios that maximizes the OAG G. As expected, G exhibits a non-monotonic trend with increasing \(\varepsilon\), as shown in Fig. 3, indicating the occurrence of the GSR phenomenon. Furthermore, all \(G(\varepsilon )\) curves tend toward a fixed value, illustrating that further increases in \(\varepsilon\) exert minimal influence on the particles’ motion. More specifically, Fig. 3b reveals that a decrease in \(\alpha\) leads to an elevation in the peak value of \(G(\varepsilon )\), accompanied by a notable leftward shift in the peak position. In Fig. 3c, the resonance peak of \(G(\varepsilon )\) is observed to ascend with an increase in \(\tau\), while the peak position remains unchanged. Consequently, enhancing system memory, reducing \(\alpha\), or increasing \(\tau\) can augment the maxima of \(G(\varepsilon )\). In Fig. 3d, the resonance peak of \(G(\varepsilon )\) becomes sharper and shifts toward zero as the noise intensity \(\sigma ^2\) increases. In simpler terms, an improvement in the system memory facilitates the accumulation of noise energy, thereby bolstering the intensity of the GSR.

Next, we primarily explore the relationship between G and the system memory parameters, specifically the fractional order \(\alpha\) and time delay \(\tau\). Notably, as illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, all the curves exhibit a distinct peak, signifying the occurrence of GSR phenomena. Upon examining Figs. 4a and 5a, it becomes evident that as \(\varepsilon\) increases, the peak values of both \(G(\alpha )\) and \(G(\tau )\) diminish. Concurrently, the peak positions shift towards conditions indicative of weaker system memory, characterized by larger \(\alpha\) values and smaller \(\tau\) values. Furthermore, both \(G(\alpha )\) and \(G(\tau )\) converge towards a constant limit, as demonstrated in Fig. 3.

GSR phenomena of \(G(\alpha )\) for different \(\varepsilon\) and \(\tau\): (a) \(\tau = 0.1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\Omega = 1.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.1\), \(\lambda = 0.1\); (b) \(\varepsilon = 1.0\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 2.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.0001\), \(\lambda = 0.3\).

GSR phenomena of \(G(\tau )\) for different \(\varepsilon\) and \(\alpha\): (a) \(\alpha = 0.4\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.1\), \(\lambda = 0.5\); (b) \(\varepsilon = 1.0\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 2.0\), \(\omega = 1.5\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.01\), \(\lambda = 0.5\).

Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4b, when \(\tau\) increases, the peak value of \(G(\alpha )\) rises, with the peak position shifting towards larger \(\alpha\) values. Conversely, in Fig. 5b, as \(\alpha\) increases, the peak value of \(G(\tau )\) initially decreases and then rises again, with the peak position moving towards larger \(\tau\) values. The analysis of Figs. 4b and 5b reveals that there exists a minimum system memory with an optimal combination of \(\alpha\) and \(\tau\) that induces the best match between the system and noise when other system parameters are fixed. Consequently, the peak position \(\alpha _\textrm{cr}\) (\(\tau _\textrm{cr}\)) shifts rightward as \(\tau\) (\(\alpha\)) increases. In essence, the enhancement of memory resulting from an increase in \(\tau\) counteracts the attenuation of memory caused by an increase in \(\alpha\), and vice versa.

Finally, we present the graphs of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) and \(G(\lambda )\) in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively, to investigate the influence of the noise parameters on the OAG G. The curves for both \(G(\sigma ^2)\) and \(G(\lambda )\) exhibit non-monotonic behavior, indicating the presence of GSR phenomena. In Fig. 6a, the peak value of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) demonstrates a non-monotonic trend, initially increasing and then decreasing as \(\varepsilon\) increases, while the peak position shifts to the right. This observation suggests that an optimal coupling strength \(\varepsilon\) can amplify the GSR intensity of \(G(\sigma ^2)\). Similarly, in Fig. 6b, the peak value of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) initially decreases and subsequently increases as \(\gamma\) increases, and the peak position shifts to the left.

GSR phenomena of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) for different \(\varepsilon\), \(\alpha\), \(\tau\) and \(\gamma\): (a) \(\alpha = 0.1\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\lambda = 0.5\); (b) \(\alpha = 0.3\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\), \(\lambda = 0.5\); (c) \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\lambda = 0.5\); (d) \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\alpha = 0.2\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\lambda = 0.5\).

Upon examining Fig. 6c,d, it becomes evident that the peak value of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) diminishes and the peak position shifts leftward when the system memory is weakened, either by increasing \(\alpha\) or decreasing \(\tau\). Notably, the GSR phenomenon disappears when the system memory becomes sufficiently weak, such as when \(\alpha > 0.4\) or \(\tau < 0.04\). In other words, the GSR phenomenon is not observed in either the integer-order coupled oscillator and the coupled fractional oscillators without time delay38. Additionally, stronger memory facilitates the transfer of noise energy to periodic signals, thereby enhancing the GSR intensity.

Moreover, in Fig. 7a, the peak value of \(G(\lambda )\) decreases and eventually stabilizes as \(\varepsilon\) increases, while the peak position shifts slightly to the right. In Fig. 7b, as \(\sigma ^2\) increases, the minima of \(G(\lambda )\) decreases and the inhibited valley becomes progressively sharper. Similar to the trends observed in Fig. 6c,d, \(G(\lambda )\) exhibits comparable variations as \(\alpha\) and \(\tau\) increase in Fig. 7c,d, respectively. Both fractional order \(\alpha\) and time delay \(\tau\) reflect the memory characteristics of the system, albeit with opposing effects. Meanwhile, the noise correlation rate \(\lambda\) reflects the memory characteristics of the noise, where a larger \(\lambda\) indicates weaker noise memory. It is important to emphasize that under the same parameter conditions, the GSR phenomenon is absent in both the integer-order coupled oscillator (when \(\alpha = 1\), as illustrated in Fig. 7c) and the coupled fractional oscillators without time delay (when \(\tau = 0\), as shown in Fig. 7d).

In summary, the system’s memory effect, influenced by a decrease in \(\alpha\) or an increase in \(\tau\), necessitates a higher noise correlation rate to counteract. We conclude that \(\varepsilon\), \(\alpha\), and \(\tau\) play crucial roles in modulating the GSR intensity of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) and \(G(\lambda )\).

GSR phenomena of \(G(\lambda )\) for different \(\varepsilon\), \(\alpha\) and \(\tau\): (a) \(\alpha = 0.4\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.1\); (b) \(\alpha = 0.2\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.3\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\); (c) \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\tau = 0.05\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.1\); (d) \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\alpha = 0.4\), \(m = 1.0\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 2.0\), \(\Omega = 2.0\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.1\).

Numerical simulations

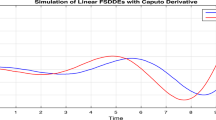

In this section, we conduct numerical simulations using both the predictor-corrector approach56 and the Monte Carlo method to validate the accuracy of the analytical result presented in Eq. (31). In Fig. 8, we first provide the comparison between the analytical and numerical results of the first-order moment of system stationary state response \(\langle x(t)\rangle _\textrm{as}\) with different driving frequencies \(\Omega = 0.2\pi\), \(0.4\pi\), and \(0.6\pi\). We carry out different number of independent realizations to compute the average value, and set the total simulation time to 100 seconds, with a time step of \(h = 0.01\) seconds. Obviously, as the number of simulations increases, i.e., \(M = 200\), the averaged numerical trajectories match well with the analytical result after a short transition time.

In Fig. 9, we further compares the analytical and numerical results of G with respect to different system parameters. Fig. 9a demonstrates a high level of agreement between the theoretical and numerical results for \(\tau < 0.2\). This consistency further confirms the validity of the analytical solution for the coupled fluctuating-mass fractional system with a small time delay. Moreover, in Fig. 9b–f, we consider the effects of system parameters \(\alpha\), \(\Omega\), \(\varepsilon\), \(\sigma\), and \(\lambda\). It is observed that for a small time delay (\(\tau = 0.1\)), the numerical results align closely with the analytical results within an acceptable error range.

The comparison between the analytical and numerical results of the first-order moment of system stationary state response \(\langle x(t)\rangle _\textrm{as}\) with different driving frequencies: (a) \(\Omega = 0.2\pi\), (b) \(\Omega = 0.4\pi\), (c) \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\). The other parameters are set as \(m = 1\), \(\alpha = 0.5\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 1.5\), \(\omega = 2\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\sigma = 0.3\), \(\lambda = 0.5\), \(A = 1\).

The comparison between the analytical and numerical results of G versus system parameters: (a) \(G(\tau )\) with \(\gamma = 2.0\), \(\omega = 1.5\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\sigma = 0.1\), \(\lambda = 0.5\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\); (b) \(G(\alpha )\) with \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 2.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\sigma = 0.01\), \(\lambda = 0.3\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\); (c) \(G(\Omega )\) with \(\alpha = 0.5\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.5\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\sigma = 0.2\), \(\lambda = 0.1\). (d) \(G(\varepsilon )\) with \(\alpha = 0.5\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.5\), \(\sigma = 0.2\), \(\lambda = 0.1\), \(\Omega = 0.8\pi\); (e) \(G(\sigma )\) with \(\alpha = 0.3\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 1.0\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\lambda = 0.5\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\). (f) \(G(\lambda )\) with \(\alpha = 0.2\), \(\tau = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 1.3\), \(\omega = 1.0\), \(\varepsilon = 1\), \(\sigma ^2 = 0.1\), \(\Omega = 0.6\pi\). The other parameters are set as \(m = 1\), \(A = 1\), \(M = 500\).

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced a system consisting of two coupled fluctuating-mass fractional oscillators with time delay. Our primary objective was to investigate the collective resonant behaviors of this system, specifically focusing on the impacts of coupling strength \(\varepsilon\), fractional order \(\alpha\), and time delay \(\tau\). By leveraging the stochastic average method, we achieved complete synchronization between the average behaviors of the two oscillators and derived the analytical expression for the OAG G.

Based on our analytical results, we observed a rich variety of GSR phenomena in the coupled fractional time-delayed system. We further explored the intricate dependencies of these GSR phenomena on several system parameters. Notably, we found that the introduction of time delay \(\tau\) leads to the emergence of more diverse GSR phenomena, including the triple-peaks GSR phenomenon. Moreover, enhancing the system memory (by decreasing \(\alpha\) or increasing \(\tau\)) amplifies the intensity of the GSR in \(G(\varepsilon )\). Interestingly, \(\varepsilon\) exerts a similar influence on the GSR phenomena observed in both \(G(\alpha )\) and \(G(\tau )\).

It is important to emphasize that \(\varepsilon\), \(\alpha\), and \(\tau\) play pivotal roles in governing the GSR behaviors of \(G(\sigma ^2)\) and \(G(\lambda )\) by facilitating their emergence and optimizing their intensity. To validate the accuracy and reliability of our analytical results, we conducted numerical simulations. The close agreement between the analytical and numerical findings confirms the robustness of our analysis.

In conclusion, we anticipate that the results obtained from this study will provide significant theoretical support for future research endeavors, particularly in fields such as signal processing and fault diagnosis. By elucidating the intricate relationships between system parameters and GSR phenomena, our findings have the potential to unlock new avenues for exploration and drive advancements in these important areas.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Benzi, R., Sutera, A. & Vulpliani, A. The mechanism of stochastic resonance. J. Phys. A 14, L453-457 (1981).

Gammaitoni, L., Hanggi, P., Jung, P. & Marchesoni, F. Stochastic resonance. J. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 223–287 (1998).

Yang, J., Rajasekar, S. & Sanjuan, M.A.F., Vibrational resonance: A review. Phys. Rep. 1067, 1–62 (2024).

Katrin, L., Romi, M. & Astrid, R. Constructive influence of noise flatness and friction on the resonant behavior of a harmonic oscillator with fluctuating frequency. Phys. Rev. E 79, 051128 (2009).

Gitterman, M. Harmonic oscillator with multiplicative noise: Nonmonotonic dependence on the strength and the rate of dichotomous noise. Phys. Rev. E 67, 057103 (2003).

Gitterman, M. & Shapiro, I. Stochastic resonance in a harmonic oscillator with random mass subject to asymmetric dichotomous noise. J. Stat. Phys. 144, 139–149 (2011).

Burov, S. & Gitterman, M. Noisy oscillator: Random mass and random damping. Phys. Rev. E 94, 052144 (2016).

You, P., Lin, L. & Wang, H. Cooperative mechanism of generalized stochastic resonance in a time-delayed fractional oscillator with random fluctuations on both mass and damping. Chaos Soliton Fractals 135, 109789 (2020).

Gitterman, M. Classical harmonic oscillator with multiplicative noise. Physica A 352, 309–334 (2005).

Lin, L. F., Zhou, X. W. & Ma, H. Subdiffusive transport of fractional two-headed molecular motor. Acta Phys. Sin. 24, 240501 (2013).

Wang, H., Chen, K. & Lin, L. Bearing fault diagnosis based on the active energy conversion of generalized stochastic resonance in fluctuating-frequency linear oscillator. Meas. Sci. Technol. 32, 125017 (2021).

Chen, K., Lu, Y., Lin, L. & Wang, H. A new dynamical method for bearing fault diagnosis based on optimal regulation of resonant behaviors in a fluctuating-mass-induced linear oscillator. Sensors 21, 707 (2021).

Chen, K., Lu, Y., Zhang, R. & Wang, H. The adaptive bearing fault diagnosis based on optimal regulation of generalized SR behaviors in fluctuating-damping induced harmonic oscillator. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 189, 110078 (2023).

Bao, J. D. & Zhuo, Y. Z. Investigation on anomalous diffusion for nuclear fusion reactions. Phys. Rev. C 67, 064606 (2003).

Goychuk, I. Subdiffusive Brownian ratchets rocked by a periodic force. Chem. Phys. 375, 450–457 (2010).

Mankin, R., Laas, K. & Lumi, N. Memory effects for a trapped Brownian particle in viscoelastic shear flows. Phys. Rev. E 88, 042142 (2013).

Ghosh, S., Cherstvya, A. & Metzler, R. Non-universal tracer diffusion in crowded media of non-inert obstacles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 310, 1847–1858 (2015).

Min, W., Luo, G., Cherayil, B. J., Kou, S. C. & Xie, X. S. Observation of a power-law memory kernel for fluctuations within a single protein molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 198302 (2005).

Bai, W. S. M., Peng, H., Tu, Z. & Ma, H. Fractional Brownian motor and its directed transport. Acta Phys. Sin. 21, 210501 (2012).

Mankin, R. & Kekker, A. Memory-enhanced energetic stability for a fractional oscillator with fluctuating frequency. Phys. Rev. E 81, 041122 (2010).

Zhong, S. C., Ma, H., Peng, H. & Zhang, L. Stochastic resonance in a harmonic oscillator with fractional-order external and intrinsic dampings. Nonlinear Dyn. 82, 535 (2015).

Lin, L. F., Chen, C. & Wang, H. Q. Trichotomous noise induced Stochatic resonance in a fractional oscillator with random damping and random frequency. J. Stat. Mech. 2016, 023201 (2016).

Zhang, L., Lai, L., Tu, Z. & Zhong, S. Stochastic and superharmonic stochastic resonances of a confined overdamped harmonic oscillator. Phys. Rev. E 97, 012147 (2018).

He, L., Wu, X. & Zhang, G. Stochastic resonance in coupled fractional-order linear harmonic oscillators with damping fluctuation. Physica A 545, 123345 (2020).

Zhang, G., Wang, H. & Zhang, H. Stochastic resonance research on under-damped nonlinear frequency fluctuation for coupled fractional-order harmonic oscillators. Results Phys. 17, 103058 (2020).

Liu, Y. Y., Sun, Z. K., Yang, X. L. & Xu, W. Asymmetric feedback enhances rhythmicity in damaged systems of coupled fractional oscillators. Commun. Nonlinear Numer. Simulat. 93, 105501 (2021).

Wei, Z., Kumarasamy, S., Ramasamy, M., Rajagopal, K. & Qian, Y. Mixed-mode oscillations and extreme events in fractional-order Bonhoeffer-van der Pol oscillator. Chaos 33, 093136 (2023).

Sauga, A., Mankin, R. & Ainsaar, A. Resonant behavior of a fractional oscillator with fluctuating mass. AIP Conf. Proc. 1487, 224–232 (2012).

Zhong, S., Wei, K., Gao, S. & Ma, H. Trichotomous noise induced resonance behavior for a fractional oscillator with random mass. J. Stat. Phys. 159, 195–209 (2015).

Lin, L. & Wang, H. Tempered Mittag–Leffler noise-induced resonance behaviors in the generalized Langevin system with random mass. Nonlinear Dyn. 98, 801–817 (2019).

Guo, F., Zhu, C. Y., Cheng, X. F. & Li, H. Stochastic resonance in a fractional harmonic oscillator subject to random mass and signal-modulated noise. Physcia A 459, 86–91 (2016).

Yang, S., Deng, M. & Ren, R. Stochastic resonance of fractional-order Langevin equation driven by periodic modulated noise with mass fluctuation. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 81 (2020).

Tian, Y., Yu, T., He, G., Zhong, L. F. & Stanley, H. E. The resonance behavior in the fractioanl harmonic oscillator with time delay and fluctuating mass. Physica A 545, 123731 (2020).

Huang, X., Lin, L. & Wang, H. Generalized stochastic resonance for a fractional noisy oscillator with random mass and random damping. J. Stat. Phys. 178, 1201–1216 (2020).

Nicolis, C. & Nicolis, G. Coupling-enhanced stochastic resonance. Phys. Rev. E 96, 042214 (2017).

Yang, B., Zhang, X., Zhang, L. & Luo, M. K. Collective behavior of globally coupled Langevin equations with colored noise in the presence of stochastic resonance. Phys. Rev. E 94, 022119 (2016).

Zhong, S., Lv, W., Ma, H. & Zhang, L. Collective stochastic resonance behavior in the globally coupled fractional oscillator. Nonlinear Dyn. 94, 905–923 (2018).

Yu, T., Zhang, L., Ji, Y. & Lai, L. Stochastic resonance of two coupled fractional harmonic oscillators with fluctuating mass. Commun. Nonlinear Numer. Simulat. 72, 26–38 (2019).

Lin, L., He, M. & Wang, H. Collective resonant behaviors in two coupled fluctuating-mass oscillators with tempered Mittage–Leffler memory kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals 154, 111641 (2022).

Maza, D., Mancini, H., Boccaletti, S., Genesio, R. & Arecchi, T. Control of amplitude turbulence in delayed dynamical systems. Int. J. Bifur Chaos 8, 1839–1842 (1998).

Bao, H. & Cao, J. Delay-distribution-dependent state estimation for discrete-time stochastic neural networks with random delay. Neural Netw. 24, 19–28 (2011).

He, M., Xu, W. & Sun, Z. Dynamical complexity and stochastic resonance in a bistable system with time delay. Nonlinear Dyn. 79, 1787–1795 (2015).

Wen, S. F., Shen, Y. J., Yang, S. P. & Wang, J. Dynamical response of Mathieu–Duffing oscillator with fractional-order delayed feedback. Chaos Solitons Fractals 94, 54–62 (2017).

Rajagopal, K., Karthikeyan, A. & Srinivasan, A. Bifurcation and chaos in time delayed fractional order chaotic memfractor oscillator and its sliding mode synchronizetion with uncertainties. Chaos Solitons Fractals 103, 347–356 (2017).

Liu, J. & Wang, Y. Performance investigation of stochastic resonance in bistable systems with time-delayed feedback and three types of asymmetries. Physica A 493, 359–369 (2018).

Yang, T. & Cao, Q. Delay-controlled primary and stochastic resonance of the SD oscillator with stiffness nonlinearities. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 103, 216–235 (2018).

Guo, Q., Sun, Z. K. & Xu, W. Bifurcations in a fractional birhythmic biological system with time delay. Commun. Nonlinear Numer. Simulat. 72, 318–328 (2019).

EI-Borhamy, M. Chaos transition of the generalized fractional duffing oscillator with a generalized time delayed position feedback. Nonlinear Dyn. 101, 2471–2487 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. The impact of memory effect on resonance behavior in a fractional oscillator with small time delay. Physica A 563, 125383 (2021).

Wang, Q., Wu, H. & Yang, Y. The effect of fractional damping and time-delayed feedback on the stochastic resonance of asymmetric SD oscillator. Nonlinear Dyn. 107, 2099–2114 (2022).

Lin, L., Lin, T., Zhang, R. & Wang, H. Generalized stochastic resonance in a time-delay fractional oscillator with damping fluctuation and signal-modulated noise. Chaos Solitons Fractal 170, 113406 (2023).

Zhong, S., Zhang, L., Wang, H., Ma, H. & Luo, M. Nonlinear effect of time delay on the generalized stochastic resonance in a fractional oscillator with multiplicative polynomial noise. Nonlinear Dyn. 89, 1327–1340 (2017).

He, M., Wang, H. & Lin, L. Time-delay effects on the collective resonant behavior in two coupled fractional oscillators with frequency fluctuations. Fractal Fractional 8, 287 (2024).

Kubo, R. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Rep. Prog. Phys. 29, 255–284 (1966).

Shapiro, V. E. & Loginov, V. M. “Formulae of differentiation’’ and their use for solving stochastic equations. Physica A 91, 563–574 (1978).

Deng, W. & Barkai, E. Ergodic properties of fractional Brownian–Langevin motion. Phys. Rev. E 79, 011112 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.72071019), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (No.CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0551), and the Innovation Fund of Fuzhou University of International Studies and Trade (No.FWKQJ2024101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L., Wang, H. Time delay effects on collective resonant behaviors in two coupled fractional oscillators with mass fluctuations. Sci Rep 15, 2335 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86080-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86080-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Competing effect of activity and non-inert crowding on the dynamics of self-propelled tracer particles

Scientific Reports (2025)