Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to unprecedented transformation of consumer behaviors. Despite the abundance of research on this subject, less is known about why and how consumers processed health information and subsequently decided to purchase food during the pandemic. This study employed a survey questionnaire to collect the data. The sample size consisted of 590 consumers in China. The data were analyzed via SPSS and SmartPLS version 3.2.9 to explore the relationships among variables. The results showed that health information-seeking behavior has a significant impact on healthy food product purchasing intention. Similarly, health-related internet use also has a positive impact on health information seeking. Moreover, the impact of motivation for healthy eating on health information seeking is significant. The results indicate a significant moderating role of social influence (i.e., interaction between health information seeking and healthy food product purchasing intention). Multigroup analysis revealed differences between income and age in terms of health-related internet use and purchasing intention. This study assessed healthy food product purchasing intention in a timely manner by incorporating health communication. variables and social influence into consumer behavior research in the context of COVID-19. It thus expands the extant literature and provides insights into the knowledge and practices concerned.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overwhelming information, high death rates, fear and anxiety stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic have posed various challenges to individuals’ health and well-being. To cope with this problem, relevant government bodies have implemented social isolation or lockdown policies and encouraged people to practice hygienic measures. As a result of the pandemic, fears among consumers have triggered the adoption of multiple coping strategies and adaptation methods1. Consequently, people began focusing more on their physical bodies and existing medical conditions. As Aydemir and Ulusu2 opined, this pandemic has been a timely reminder of the importance of strengthening the immune system and the adverse health effects of global climate change on public health.

Health food products have become increasingly popular among Chinese consumers in recent years. According to a survey among Chinese respondents in February 2021, approximately 30% spent 300 to 500 Chinese yuan on health and functional food products per month3. Another report in 2019 found that approximately 641.2 thousand metric tons of functional food were produced in China, an increase from approximately 587.5 thousand metric tons the year before. The demand for health and functional food was approximately 636 thousand metric tons, representing a rough supply-demand equilibrium4. People are more concerned with their health and conscious about healthy food preferences. Likewise, Chinese grocery shopping patterns have changed, focusing more on healthy and nutritional food. This demonstrates a high and intensified demand for healthy and functional products among Chinese consumers amid the pandemic.

In health communication, the internet has emerged as a pivotal medium for individual health, with the widespread availability of information, egalitarian access, affordances, instantaneous interaction, customisation, and anonymity5,6. Health-related internet use may also be attributable to deliberate health information seeking, health literacy, and subsequent behaviours7. However, recapping the literature, Health Communication Knowledge has not been widely applied to examining consumer behaviours. This gap is exacerbated by severe COVID-19, which engenders questions such as how people perceive their health status, whether it fuels information-seeking and subsequently affects consumer health in food product purchasing, and how these factors are associated. With this in mind, this study aims to unravel the determinants of purchasing healthy food products during COVID-19.

This study contributes to the current literature and research in two key ways. First, this study commits to bringing Health Commun. variables into the consumer behaviour field. This attempt is significant, as a multidisciplinary perspective could help gauge why and how consumers are prone to buy certain items. Second, this study attempts to add more evidence to the relatively limited body of literature on the direct and indirect determinants of purchasing intention and the moderating impact of social influence. Considering that China is a collective society where people highly value the opinions of others, our incorporation of social influence as a moderator is particularly appropriate and imperative8,9. This could also help delve into the purchasing intention in a particular setting. Overall, it is indispensable to investigate how media, motivation, and other variables affect healthy food product purchasing intention amid the pandemic. This study revealed the marketing mechanism, which in turn helps advertisers calibrate their strategies. Based on the discussion provided above, there exists a gap in the literature that this study aims to fill by examining: the impact of perceived health risks, health-related internet use and motivation for healthy eating on health-seeking information. Further, the study also examines the impact of health-seeking information on health food product purchasing with the moderating role of social influence.

Theoretical foundation

The overarching framework of this study is The Hierarchy of Effects Model (HOE). The HOE model is a response hierarchy model that describes the process of consumers’ response to information and systematically illustrates the transformation process from consumers’ ignorance of a product to the actual purchase behaviour10,11. It includes the following elements: awareness, knowledge, liking, preference, conviction, and purchase12. Awareness represents the initial hierarchy stage, where consumers become cognizant of a product, service, or idea13. This stage is often achieved through advertising, word-of-mouth, or exposure to information. Knowledge follows awareness and involves consumers seeking information to understand the offering’s features, benefits, and attributes. Information-seeking and research are everyday activities during this stage14. Liking signifies the development of a positive attitude or preference for the product or idea. Factors such as personal preferences, brand reputation, and emotional connections come into play here. Preference denotes that consumers start to favour the product or idea over alternatives15. This stage involves comparing options and choosing based on personal preferences and needs. Conviction reflects establishing a firm belief or confidence in the selected product or idea. It signifies that consumers are committed to their decisions and are less susceptible to external influences. The final stage of the hierarchy is the actual purchase or action, where consumers translate their intentions and beliefs into a concrete decision to buy or engage with the offering.

Also, this study employs Cultivation Theory to support the HOE. It was developed by Gerbner and Gross16, who assume that repeated and extensive watching of television influences people’s conceptions of reality to reflect what they see on television. This influence is reflected in the following two levels of effects: “first-order” effects (general beliefs about the everyday world, such as the prevalence of violence) and “second-order” effects (specific attitudes, for example, attitudes toward personal safety). More recent applications and references to Cultivation Theory have similarly posited that repeated and extensive exposure to mass media, online and social media content depicting the world as a dangerous place similarly influences people’s conceptions of, and feelings about, reality to reflect how it is depicted in media and social media17,18.

This model has derived relationships from various theories. The Extended Health Belief Model (EHBM) rationalises the influence of media on beliefs/perceptions. The Health Belief Model (HBM), initially developed by Rosenstock and later refined by Maiman and Becker, outlines five key aspects of patients’ health beliefs. According to the model, health-related decisions are influenced by individuals’ perceptions of their susceptibility to and the severity of a health issue, the perceived benefits and barriers to taking action, and the triggers that prompt action. The model was later expanded to include the concept of self-efficacy, forming the Extended Health Belief Model (EHBM). This extended model operates on the premise that individuals will engage in health-related behaviours if they believe an adverse health outcome can be prevented, expect that the recommended action will help avoid the issue, and have confidence in their ability to perform it successfully. The EHBM has been used in various contexts, such as prevention efforts like smoking cessation and managing illness behaviours like taking medication. In the current study, we have tested the underpinnings that assume the individual’s action of purchasing functional production due to their perceptions of their susceptibility to and the severity of COVID-19. However, this research is not to measure the constructs of the HBM directly but rather to use it as a theoretical underpinning to contextualize and explain the relationship between health information-seeking behavior and purchasing intention during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cultivation theory and the Extended Health Belief Model (EHBM) collectively help to hypothesise the perceived health risks depicted by media, which can affect consumers at various stages of the HOE model. During the awareness and knowledge stages, media portrayal of health risks may heighten consumers’ perceived susceptibility and severity of health issues, aligning with the EHBM’s focus on perceived susceptibility and severity as motivators for action. This heightened perception prompts consumers to seek more health-related information, consistent with the knowledge stage of the HOE model, where individuals acquire information about product features and benefits.

As consumers move to the liking and preference stages, the positive attitudes towards healthy behaviours fostered by the EHBM (due to the perceived benefits of taking action and reduced perceived barriers) intersect with the HOE model, leading to a stronger preference for healthier food products. Cultivation Theory further suggests that ongoing media exposure reinforces these attitudes and beliefs, thereby solidifying consumers’ commitment to healthy eating behaviors in the conviction stage of the HOE model.

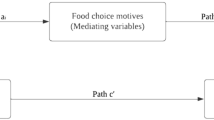

Finally, the perceived health risks highlighted by media, as explained by Cultivation Theory, and the motivational aspects of the EHBM influence consumers’ final purchase decisions. Health information seeking, driven by media portrayals and supported by the EHBM’s emphasis on actionable health information, serves as a mediator in the HOE model, linking perceived risks to purchasing intentions. As a moderator, social influence can amplify this relationship by affecting how health information and perceived risks influence purchasing intentions, depending on societal norms and peer recommendations. The conceptual framework for better visualization of the relationships is presented in Figure.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Self-perceived health risk

Health has been defined as the “state of complete mental, social and physical well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”19. Self-perceived health risk is the perception of an individual’s well-being and health, and it is primarily a subjective factor that depicts the opinion on one’s health status based on multiple dimensions20. Research has indicated that self-perceived health is an imperial indicator for morbidity, mortality, disability, functional decline, and usage of health services5,21,22. An individual’s health is influenced by mental health, physical health, overall functionality, and environmental, social, and demographic factors23. However, less association has been built between self-perceived health and consumer behaviours.

Against the backdrop of COVID-19, “health” has become a buzzword in every field. Studies have indicated that lifestyles since the pandemic have significantly altered people’s shopping behaviours24. As people were increasingly concerned about getting infected, the pandemic has induced fear and raised concerns about their health. Fear mainly influenced the perception of health risk by people across the globe, which ultimately increased health information seeking25. Individuals often seek information about COVID-19 to prevent the contraction of the disease, especially those who have previously been affected. Their objective is to safeguard themselves from a potential recurrence of the infection, driven by the apprehension of experiencing a more severe illness upon subsequent exposure. This apprehension also prompts individuals to recognise gaps in their knowledge, motivating them to pursue further information on the topic26. Moreover, the meta-analysis by Huang et al.27showed that fear or self-perceived health risk can effectively increase health information seeking to curb the effects of COVID-19. Other available studies also suggest a strong connection between fear and self-concern for health and health information-seeking behaviour28,29.

The construct of self-perceived health risk indicates behavioural decisions and reflects their concern and fear. The present study proposes that increased self-perceived health risk leads to an adequate search for health information. Even though health information-seeking behaviours have been studied in drug-taking, dangerous items and so forth, the association between health information-seeking and self-perceived health risk has yet to be studied in the presence of the COVID pandemic. Based on the discussion, it is hypothesised that:

H1: Perceived health risk is positively related to seeking health information.

Health media use and information seeking

Health information seeking is the behaviour that leads people to search for information related to their health in light of preconditions or suspected conditions30,31. Although previous studies have shown a significantly high incidence of people seeking health-related information through the Internet32,33,34, since the onset of COVID-19, people have been increasingly conscious of their health and safety and thus seek health information online35. The restrictions on the movement of people have caused them to shift toward the Internet to obtain answers to their health-related questions36, thereby empowering the Internet as a source of information related to health.

Information-seeking behaviours have intensified due to people’s perceptions of health risks. Individuals also use this information to purchase products relevant to their health5,33,35. Moreover, the literature has lent credence that the knowledge of product healthiness and nutrition impacts the purchase of products37. This behaviour has been magnified due to the impact of COVID-19 since people are heavily concerned about their health38. Claims of nutrition and healthiness of a food product are used to promote health-related aspects. Furthermore, through knowledge of the products, consumers’ perceptions regarding the healthiness of products are modified. With a high perception of the nutrition and healthiness of a product, there is a high possibility of purchasing the products. Consumers with more knowledge would spend more time looking at the products’ health information, and nutrition claims39,40. Based on the evidence from the literature, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: Health-related internet use is positively related to health information seeking.

H3: Health information seeking is positively related to purchasing health food products.

Motivation for healthy eating

Eating is a behaviour related to psychological, social, physiological, and genetic factors that influence meal preferences, habits, and food selection41,42. Developing and maintaining healthy eating habits contribute to long, healthy lives free of disabilities43,44. Numerous factors, such as mental health, accessibility to options, personality, and cognitive capacity, influence the decisions and preferences around food intake45,46. The motivation behind these decisions varies from individual to individual44. Nevertheless, motivation initiates and maintains activity, and it is seen as a target variable of simultaneously enhancing food behaviours and health guidance47.

Extant research indicates that both internal and external motivations are imperative to conform to a lifestyle directed by healthy food options42,44. The motivation for healthy eating inspires individuals to search for information related to their nutritional requirements, thus inspiring health information seeking. The interest in the nutritional value of food products and the ability of individuals to comprehend this information is essential in modelling their information-seeking behaviours. Moreover, according to studies conducted in the United States, there is a strong association between the motivation for healthy eating and the information-seeking behaviours of people48,49. Furthermore, the literature has shown that people with solid convictions regarding their capacity to obtain and implement health information into practice are positively associated with improved health. The information-seeking behaviors of these individuals are more active30,50. Consequently, it is postulated in the current study that:

H4: Motivation for healthy eating is positively related to health information seeking.

Social influence as the moderator

Holbrook51defined value as “a belief about some desirable end-state that transcends specific situations and guides the selection of behaviour.” Relatedly, the concept of social influence pertains to the influence of social norms and values on people’s decision-making processes. The social context influences consumer behaviors and perceptions, especially regarding food products, and it tends to be normative and informational. The social context guides consumers to make informed choices through credible purchase sources52.

The concept of social influence is popular because it demonstrates and exposition of the striking psychological phenomenon most commonly observed as a direct response to explicit social factors. It is suggested that people are more likely to comply with a particular form of response due to a specific form of request or communication. Through social influence, the target being influenced is expected or determined to perform and act in a certain manner due to being influenced by the surroundings or in communication with surrounding people53.

Furthermore, social influence shapes people’s behaviors, minimising the uncertainty associated with their decisions and imitating similar decisions made and repeated by several people. This effect shows that social influence can occur through observing other people’s actions in the consumer decision process54. Parshakov et al.55studied Google search trends in 138 different countries to analyse culture’s influence on seeking health-related information during COVID-19, considering the socio-economic factors. The results showed that culture had a significant impact on health search behaviour. It is pertinent to analyse this behaviour in a collectivist society where the adoption patterns are intertwined. It is particularly salient in China, a collectivistic society, where people value family and others’ perceptions and adhere to social norms56.

Based on the reviewed literature, the current study suggests that during the COVID-19 pandemic, wherein perceived health risk and uncertainty increased, the association between gathering information on healthy food and buying products can be influenced by social influence. Specifically, the positive and high impact of social factors would lead to the purchase of products. In contrast, the negative and low social influence may result in a decreased inclination toward healthy food product purchasing. Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H5: Social influence will moderate the relationship between health information seeking and health food product purchasing. The higher the social influence, the more inclination there is to purchase.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework.

Methods

Procedure

This quantitative study collected data using computer-assisted online surveys administered in mainland China from 10 June 2023 to 21 October 2023. In China, online surveys have increased over time due to their easy access and ability to provide a sufficient response rate. However, due to technological constraints, social and cultural norms, and language barriers, Chinese-based platforms are mainly used for these online surveys. One widely used online platform is Wen Juanxing, which has 2.6 million members. Furthermore, online surveys in China have gained more attention due to the higher use of the Internet and social networking sites. Young people in China are growing up with Web 2.0 technologies, which provide them access to an ever-increasing array of flexible applications, portable digital devices, and online resources (CNNIC, 2017). Wen Juanxing was employed to obtain data to control sample homogeneity and better response rates18. Wen Juanxing has members all over China and has access to the broader population. However, the researchers set specific criteria to gain responses from the intended sample. Several filter questions were adopted to ensure the questionnaire respondents’ suitability. The respondents proceeded with the questionnaire only if they provided an affirmative answer to the following questions: ‘Did you have two or more online shopping experiences in the last month?’ and ‘Did you have experience buying health and functional products online during COVID-19?’. Also, the operationalisation of functional and health products is clearly stated at the top of the questionnaire: In this study, functional and health products refer to consumer goods designed to provide specific health benefits or enhance overall well-being. It includes but is not limited to Dietary supplements, Nutraceuticals, Herbal and Natural Remedies, etc.

Respondents who gave consent to participate in the survey willingly clicked the ‘continue’ button. Subsequently, it directed respondents to complete the self-administered questionnaire. The relevant Ethics Review Committee approved the study protocol. Respondents’ informed consent was also obtained.

Sample size

The sample size of the current study was calculated using G*Power 3.1, an analytical software program for sample size determination57,58. Power analysis “A-priori: Compute required sample size – given α, power and effect size” was selected for this research, where the effect size was fixed at 0.15 alpha, error probability 0.05, and power (1–β error probability) was set at 0.95. The number of predictors for the current study is 5. Hence, the minimum sample size for the current study was 138. Thus, the 590 responses were deemed valid for generating statistical results.

Measures

This study adopted items from the prior literature that have been widely used and proven to have high validity and reliability. Self-perceived health status was measured by asking, “How do you rate your health in general?” They were asked to rate their health status according to one of five answers: very bad, bad, fair, good, very good, adapted from Svendsen, Bak59. Health-related internet use was measured and adapted from Ahadzadeh, Pahlevan Sharif60and Jiang and Beaudoin5with a 5-point scale from ‘Never’ to ‘Always.’ The Motivation for Healthy Eating measurement was adapted from44, and social influence was adapted from52. Finally, health food purchasing intention was adapted from61, and a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ was used to measure items. All items can be seen in Appendix A.

Data analysis

SPSS 27 is applied to perform descriptive statistical analysis. Subsequently, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) is applied to examine the associations between all the constructs examined by Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM has been a popular statistical technique in consumer behavior62,63. We chose PLS-SEM due to its several advantages over CB-SEM. As a prediction-oriented method, PLS-SEM is more suitable for theory development, which is the purpose of this study. Additionally, it is the most suitable approach with known limitations for developing and estimating the causal relationships of a complex structural model with higher-order and formative constructs69.

Results

This study used SPSS 26 to perform preliminary analysis. Structural equation modelling partial least squares (SEM-PLS) was employed to test the research model. This study used Smart PLS version 3.2.9 to examine the proposed research model. Following the recommendations by Hair et al. (2017), data were analysed and interpreted in two stages, namely, the assessment of the measurement and the structural model. Prior to PLS assessment, a priori and post hoc procedures were performed to address common method bias64. Harman’s single-factor test was applied in SPSS to detect CMV issues. The results showed an 18.91% variance, below the suggested threshold of 50%. Hence, CMV is not an issue in this study.

Measurement model

The measurement model is evaluated based on convergent validity and discriminant validity. The convergent validity is examined through Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extraction (AVE). As shown in Table 1, the results illustrate that all the components carry factor loadings greater than 0.7, which is satisfactory. Cronbach’s alpha is an internal consistency measure considered a reliable measure of scale reliability65. A Cronbach’s alpha between 0.7 and 0.9 is regarded as satisfactory; in contrast, an alpha below 0.7 denotes low internal consistency, while an alpha above 0.9 indicates data redundancy66. AVE has a threshold of 0.5 and CR at 0.7, above which the measures are deemed satisfactory67,68. As seen in Table 1, most values meet the minimal requirements (excluding IDR with the value of Cronbach’s alpha 0.59), indicating that overall CR was also achieved69. The value for self-perceived health is 1 for all tests because it is measured by only one item. Taken together, the reliability and accuracy of the data are confirmed.

The discriminant validity in the measurement model was examined through the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) test as suggested by Henseler, Ringle70. If the constructs are conceptually similar, a threshold value of 0.90 exists for structural models, and according to Hair, Risher71, below the threshold of 0.85 means that the construct differs from one another empirically. The results in Table 2 demonstrate that all variables have an HTMT ratio below 0.85, which suggests that all constructs are empirically different. The Fornell and Larcker criteria were also tested to double-check the discriminant validity. Table 3shows that all the constructs are similar to their items and distinct from all the other constructs72. Hence, concerns about discriminant validity are removed.

Structural model

After determining the goodness of the data, the structural model assessment was conducted. The hypotheses were assessed by bootstrapping with 5000 sub-samples following the non-parametric guidelines. Figure 2 shows the structural model.

The hypotheses were assessed by bootstrapping with 5,000 subsamples through structural equation modelling (see Table 3). The impact of health-related internet use (HIU) has a significant positive impact on health information seeking (HIS) (β = 0.472, p < 0.001), supporting H2. The impact of health information seeking (HIS) on Healthy Food Product Purchasing Intention (HPPI) is significant (β = 0.322, p < 0.001), and H3 is supported. Moreover, motivation for healthy eating (MHE) positively and significantly impacts HIS (β = 0.166, p < 0.001), lending support to H4.

The R-squared value for HIS is 0.307, and the R-squared adjusted is 0.302. This means that the observed data fit the regression model by 30.7% and adjusted R-squared by 30.2%. The values of HPPI indicate that they fit the model by 14% if R-squared is considered and 13.6%, if R-squared adjusted, is taken into account.

Next, the effect size is evaluated through F-square. This can be explained by the effect size or the measured variance that explains each variable in the model. The values below or equal to 0.02 are small effects, values between 0.02 and 0.15 are considered medium effects, and values above 0.35 are large effects. According to Table 4, all effects are small except for the effect of HIU on HIS, which is the medium.

Last, the predictive relevance (Q2 predict) was evaluated using the blindfolding function on Smart PLS. The values presented in Table 4 are HIS (0.156) and HPPI (0.094). HIS lends more support to the model’s predictive capacity on the endogenous variables. Therefore, it is surmised that the current model involving health information seeking as the predictor can predict customers’ intentions and behaviour in the given context.

To test H5, moderation analysis was performed with Health Information Seeking (HIS) as the independent variable and Healthy Food Product Purchasing Intention (HPPI) and Social Influence (SI) as moderators. The result demonstrates a significant positive interaction between HIS and SI toward HPPI (β = 0.176, p < 0.001); therefore, H5 is supported. The significant result of the interaction term was further investigated using simple slope analysis on Smart PLS. Figure 3 demonstrates an increasing trend in the relationship between HIS and HPPI due to SI.

The acceptable range for the SRMR index is between 0 and 0.08 REF (may want to cite study here). As seen in Table 5, SRMR values are within the threshold for the saturated model while slightly over it for the estimated model. A value greater than 0.9 for NFI denotes a good fit; hence, the above values indicate a weak model. Although all the values seem small, they are believed to be substantively significant for the study’s implications73.

Multigroup analysis

The questionnaire was designed to collect data on the respondents’ demographics, such as age, income, education and gender. Data were collected about the age groups 18–25, 26–30, 31–40 and 41–45 years. The respondent’s income was also collected by asking them to which income category (ranging from 0 to 5000, 5000–10000, 10001–15000, 15001–20000, 20001 and above) a respondent belonged. The question of education contained the categories of undergraduate, graduate, specialist and other. Gender was categorised as male or female.

In addition, investigations determined if the variables of interest used in the above analysis differ by age, gender, income, and education groups. MANOVA showed no significant difference in variables across age, income and education except for HPPI and HIU. A significant difference in HPPI in different income groups was observed, where F (4,427) = 5.09, p = 0.000, and Wilks’ Λ = 0.954.

HPPI also differed in age groups, F(4,427) = 2.93, p = 0.020, Wilks’ Λ = 0.973. The purchasing intention score for healthy food products (HPPI) significantly differs among income and age groups.

HIU differed by income group; F (4,427) = 7.19, p = 0.000, Wilks’ Λ = 0.937, age; F(4,427) = 3.04, p = 0.017, Wilks’ Λ = 0.972, education; F(3,428) = 3.38, p = 0.018, Wilks’ Λ = 0.977 and gender F = 5.29, p = 0.029. Health-related internet use (HIU) thus differs significantly among age, income, education categories, and gender. ANOVA was used to observe the difference in HIU between males and females. The analysis showed that HIS, SF and SI do not differ across socioeconomic groups. Based on multigroup analysis, we have seen the direction of the relationship of different socioeconomic groups with HPPI and HIU.

The ordinary least square regression results in Table 6 show that the purchasing score for healthy food products is higher for higher income groups, which is evident by their purchasing power. People in the 31–40 age group have a higher probability of purchasing healthier food products than those in the 18–25 age group due to being more health conscious in older age. Health-related internet use is higher for higher-income groups, as well as for females.

Discussion and conclusion

The functional food market is burgeoning across the world. However, the mechanism of purchasing intention still needs to be explored further. Thus, this study examines the determinants that drive people to buy healthy and functional food in China. Recapping the results, this study found that health-related internet use positively impacts people’s health information seeking, subsequently influencing health food purchasing intention. This is important because, under high media exposure in an uncertain situation, people are more likely to search for relevant information to buy something or restrict their behaviour74,75. Moreover, as anticipated, health-related internet usage and motivation for healthy eating are associated with health information seeking, which aligns with prior studies5,76,77. This result indicates that motivation is a driving factor of actual media use and seeking behaviour. In this study, learning health information is one of the most important needs. Therefore, when people have the motivation and believe that the Internet can satisfy their health needs, they are more likely to use it in subsequent health behaviours.

Moreover, it found a significant relationship between health information-seeking behaviour and healthy food product purchasing intention. This is consistent with the findings from Zhu, Yao78, arguing that there is a close relationship between consumers’ risk perception, information seeking and purchasing intention. This study contributes to the literature in the Health Commun. field in a specific context (COVID-19).

Few studies have been conducted on food purchasing behavior and experiences, but their scope differs. For example, a study in Bangkok, Thailand, showed food purchasing behaviour after introducing food delivery apps through a technology adoption model. Khalid79studied the purchase intentions and organic food consumption being influenced by the corporate image of the business, whereas another study investigated the influence of culinary presentations to tourists on their food buying experience80.

However, this study builds the pathway from health-related internet use and motivation for healthy eating to health information seeking. This is important because it unravels the predictors/mechanisms before seeking information and then purchasing products, which previous studies have failed to capture81,82. Interestingly, social influence plays a significant moderating role in interacting health information seeking and health food purchasing intention. As China is a collectivistic society where a strong hierarchy is emphasized within an interdependent collective, its people follow instructions closely from their superiors83,84. This leads to a culturally nuanced approach to communication and information processing, as suggested by various studies that have highlighted culture’s role in influencing the way individuals perceive and process information within their environment85,86,87,88. In this work, the assessment was made on not only how social influence affects an individual’s information processing, but also how it affects an individual’s behavior-changing after information processing and seeking multiple disciplinary perspectives. Meanwhile, there is a dearth of research on the abovementioned information within the context of pandemics or epidemics. Although there are contradictory findings regarding social influence, this study explores its functionality in a pandemic context, as cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping an individual’s intention and behavior18,89,90. While these findings are constrained in the communication and public health field, this study adds new evidence in the marketing and advertising discipline. Lastly, this study bridges the connectedness between a traditional communication theory (Cultivation Theory) and an advertising theory (HOE) and Extended Health Belief Model, the integration of theories and the combination elements from different theoretical perspectives to create a more comprehensive framework that can explain complex phenomena better than existing theories can on their own. Also, this helps to delve into the multidisciplinary knowledge in understanding decision-making mechanism.

Limitations and recommendations

This study has some limitations that may provide further direction for future research. First, the study is contextualized in China, which may not allow for generalizability across countries. Hence, future studies should endeavor to make comparisons across different research contexts. Second, the study was conducted when COVID-19 still posed a deadly threat to humankind. Despite the government’s efforts to alleviate its negative impact and resume business activities, previous efforts might not have fully elucidated consumer behavior during the post-pandemic era. As such, this also requires further investigation in the future.

There are certain limitations of every study which are important to report. Firstly, this study was conducted in China, which makes its findings specific to the Chinese context. The results cannot be generalized to other countries’ contexts, especially those with significantly different cultural backgrounds or non-pandemic conditions. The specific socio-economic conditions and pandemic-related factors present in China at the time of the study may have influenced the findings. These factors might not be present or might manifest differently in other countries, thus affecting the generalizability of the results across different cultural contexts or beyond pandemic conditions However, countries similar to the Chinese cultures may use this study’s findings for policy formulation and better understating of online food behaviors. Secondly, the study utilized an online questionnaire and collected data at one point in time, which introduces potential biases inherent in online surveys, such as self-selection bias. In particular, cross-sectional design could not capture the prolonged effects, which leads to generalizability issues. Future research could improve upon this by employing a longitudinal approach to analyze changes in online food decisions and behaviors over time in China and other countries. Third, a bigger sample size may yield different results and provide a holistic understanding of this study’s variables. Lastly, this study did not incorporate control variables, future studies can identify control variables that have the potential to change the relationship between independent variables and dependent variables.

Implications

This study contains some theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, it extends the applicability of the Cultivation Theory, HOE framework and EHBM to explain healthy and functional food purchasing intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a novel and important context. This study implies that the amount of online health-related information, motivation, and social influence in times of uncertainty might affect people’s decisions to buy products. Although this study does not test/measure specific variables from each theory, particular HBM. It helps understand the psychological mechanisms that drive individuals to seek health-related information and make purchasing decisions, particularly in the face of a health crisis. This model posits that individuals’ health-related behaviors are influenced by their perceptions of susceptibility to a health issue, the perceived severity of the issue, perceived benefits and barriers to taking action, and the cues that trigger behavior. Although we do not directly measure each of these constructs, they serve as critical elements in explaining how consumers’ health beliefs shape their decisions during the pandemic. In the context of COVID-19, individuals who perceive themselves as being at high risk of infection (susceptibility) and those who believe in the seriousness of potential health outcomes (severity) are more likely to actively seek health-related information. This information-seeking behavior can lead to higher motivation for purchasing functional food products that are perceived to boost immunity or promote better health outcomes. Consumers’ evaluations of the potential benefits (e.g., improving health or preventing illness) versus the barriers (e.g., higher costs or availability) of purchasing functional foods play a critical role in their purchasing decisions. The EHBM framework helps explain how individuals rationalize these factors in the face of the pandemic, particularly when they believe that functional foods can offer tangible health benefits. Social and media influences, in the form of public health campaigns, peer recommendations, or heightened media coverage on the benefits of healthy food, act as cues to action that prompt consumers to engage in health-seeking behaviors. These cues align with the EHBM’s emphasis on external stimuli that trigger behavior changes, such as the decision to purchase health and functional food products. The model complements the Cultivation Theory and HOE framework, offering deeper insights into the health motivations and behaviors of consumers during uncertain times. This integration adds theoretical depth to our analysis by linking perceived health risks with behavioral outcomes. Thus, the integration of theories offers a comprehensive understanding of the psychological and behavioral processes that drive health-related decision-making.

This study has some vital practical implications. First, it sheds light on the importance of media exposure, which encourages health marketing managers to improve the visibility of certain brands online. Moreover, the R-squared value of Health Information Seeking (HIS) indicates that the model accounts for 30.7% of the variance in HIS, representing a moderate effect size. This finding suggests that a significant portion of health information-seeking behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to factors such as perceived health risks and social influence. From a practical perspective, this emphasizes the importance of addressing both individual perceptions of health risks and the role of social networks in shaping health behaviors. Health practitioners, policymakers. Furthermore, relevant marketers, practitioners should accentuate cultural factors when deploying branding strategies. The result shows that social influence has a significant moderating effect. It is also evident from the F-squared values that the predictors highlight varying degrees of influence, with social influence having a small to medium effect size, which can affect consumer behavior91,92. Practically, this implies that public health campaigns should incorporate strategies that engage social networks and peer influence. Accentuating cultural factors in branding strategies is essential for marketers and practitioners because it allows them to create more relevant and engaging experiences for their target audience. By considering cultural nuances, values, beliefs, and preferences, marketers can tailor their branding efforts to resonate with specific cultural groups. This approach helps build a stronger connection with consumers, enhances brand perception, and ultimately influences consumer behavior (Jumriani et al., 2022). The policy makers can also benefit from the findings of this study. They can monitor the marketers’ compliance with food safety and regulatory requirements. This will boost the consumer’s confidence to purchase food online. Lastly, based on multigroup analysis, those who are female and in the age range of 31–40 have a higher product purchasing power93, which is a demographic segmentation that mangers and markers should focus on.

Data availability

Data can be provided on reasonable request for academic purposes only from the corresponding author. Questionnaire can be found at https://osf.io/ym8zf/.

References

Kirk, C. P. & Rifkin, L. S. I’ll trade you diamonds for toilet paper: consumer reacting, coping and adapting behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Res. 117, 124–131 (2020).

Aydemir, D. & Ulusu, N. N. Influence of lifestyle parameters–dietary habit, chronic stress and environmental factors, jobs–on the human health in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Disaster Med. Public. 14, e36–e37 (2020).

Slotta, D. Distribution of monthly spending on health and functional food products in China as of February 2021. iiMedia Research (2022).

Ma, Y. Total production volume of health and functional food in China from 2012 to 2019. (2021).

Jiang, S. & Beaudoin, C. E. Health literacy and the internet: an exploratory study on the 2013 HINTS survey. Comput. Hum. Behav. 58, 240–248 (2016).

Park, E. & Kwon, M. Health-related internet use by children and adolescents: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e7731 (2018).

Lomanowska, A. M. & Guitton, M. J. My avatar is pregnant! Representation of pregnancy, birth, and maternity in a virtual world. Comput. Hum. Behav. 31, 322–331 (2014).

Moussaïd, M., Kämmer, J. E., Analytis, P. P. & Neth, H. Social influence and the collective dynamics of opinion formation. PloS One. 8, e78433 (2013).

Varshneya, G., Pandey, S. K. & Das, G. Impact of social influence and green consumption values on purchase intention of organic clothing: a study on collectivist developing economy. Glob Bus. Rev. 18, 478–492 (2017).

Barry, T. E. & Howard, D. J. A review and critique of the hierarchy of effects in advertising. Int. J. Advert. 9, 121–135 (1990).

Barry, T. E. In defence of the hierarchy of effects: a rejoinder to Weilbacher. J. Advertising Res. 42, 44–47 (2002).

Smith, R. E., Chen, J. & Yang, X. The impact of advertising creativity on the hierarchy of effects. J. Advertising. 37, 47–62 (2008).

Wijaya, B. S. The development of hierarchy of effects model in advertising. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 5, 73–85 (2015).

Hutter, K., Hautz, J., Dennhardt, S. & Füller, J. The impact of user interactions in social media on brand awareness and purchase intention: the case of MINI on Facebook. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 22, 342–351 (2013).

Delbaere, M., Michael, B. & Phillips, B. J. Social media influencers: a route to brand engagement for their followers. Psychol. Market. 38, 101–112 (2021).

Gerbner, G. & Gross, L. Living with television: the violence profile. J. Commun. 26, 172–199 (1976).

Tsoy, D., Tirasawasdichai, T. & Kurpayanidi, K. I. Role of social media in shaping public risk perception during COVID-19 pandemic: a theoretical review. Int. J. Manag Sci. Bus. Admin. 7, 35–41 (2021).

Gong, J. et al. Pathways linking media use to wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mediated moderation study. Soc. Media Soc. 8, 20563051221087390 (2022).

World Health Organization. Integrated care for older people: guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity. (2017).

Helvik, A. S., Engedal, K., Bjørkløf, G. H. & Selbæk, G. Factors associated with perceived health in elderly medical inpatients: a particular focus on personal coping recourses. Aging Ment Health. 16, 795–803 (2012).

Isaac, V., McLachlan, C. S., Baune, B. T., Huang, C. T. & Wu, C. Y. Poor self-rated health influences hospital service use in hospitalized inpatients with chronic conditions in Taiwan. Medicine 94, e1477 (2015).

Machón, M., Vergara, I., Dorronsoro, M., Vrotsou, K. & Larrañaga, I. Self-perceived health in functionally independent older people: associated factors. BMC Geriatr. 16, 1–9 (2016).

Croezen, S., Burdorf, A. & van Lenthe, F. J. Self-perceived health in older europeans: does the choice of survey matter? Eur. J. Public. Health. 26, 686–692 (2016).

Andrianto, N. M., Oktora, K. & Bon, A. T. Understanding Millennial’s Online Buying Behavior During Pandemic Covid-19. in 11th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations ManagementIEOM (2021).

Eder, S. J. et al. Predicting fear and perceived health during the COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning: a cross-national longitudinal study. Plos One. 16, e0247997 (2021).

Li, S. C. S., Lo, S. Y., Wu, T. Y. & Chen, T. L. Information seeking and processing during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Taiwan: examining the effects of emotions and informational subjective norms. Int. J. Environ. Res. He. 19, 9532 (2022).

Huang, F. et al. How fear and collectivism influence public’s preventive intention towards COVID-19 infection: a study based on big data from the social media. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1–9 (2020).

Lee, S. Y. & Hawkins, R. P. Worry as an uncertainty-associated emotion: exploring the role of worry in health information seeking. Health Commun. 31, 926–933 (2016).

Zimbres, T. M. Processing and Effects of Contradictory Health Information. UC Davis (2021).

Eriksson-Backa, K., Enwald, H., Hirvonen, N. & Huvila, I. Health information seeking, beliefs about abilities, and health behaviour among Finnish seniors. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 50, 284–295 (2018).

Deng, Z. & Liu, S. Understanding consumer health information-seeking behavior from the perspective of the risk perception attitude framework and social support in mobile social media websites. Int. J. Med. Inf. 105, 98–109 (2017).

Sillence, E., Blythe, J. M., Briggs, P. & Moss, M. A revised model of trust in internet-based health information and advice: cross-sectional questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e11125 (2019).

Chen, Y. Y., Li, C. M., Liang, J. C. & Tsai, C. C. Health information obtained from the internet and changes in medical decision making: questionnaire development and cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e47 (2018).

Masson, C. L., Chen, I. Q., Levine, J. A., Shopshire, M. S. & Sorensen, J. L. Health-related internet use among opioid treatment patients. Addict. Behav. Rep. 9, 100157 (2019).

Díaz de León Castañeda, C. Martínez Domínguez, M. factors related to internet adoption and its Use to seek Health Information in Mexico. Health Commun. 36, 1768–1775 (2020).

Gianfredi, V., Sandro, P. & Santangelo, O. E. What can internet users’ behaviours reveal about the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic? A systematic review. Public. Health. 198, 44–52 (2021).

Liu, A. & Niyongira, R. Chinese consumers food purchasing behaviors and awareness of food safety. Food Control. 79, 185–191 (2017).

Laguna, L., Fiszman, S., Puerta, P., Chaya, C. & Tárrega, A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 86, 104028 (2020).

Rana, J. & Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: a meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 44, 162–171 (2020).

Steinhauser, J., Janssen, M. & Hamm, U. Who buys products with nutrition and health claims? A purchase simulation with eye tracking on the influence of consumers’ nutrition knowledge and health motivation. Nutrients 11, 2199 (2019).

Rafacz, S. D. Healthy eating: approaching the selection, preparation, and consumption of healthy food as choice behavior. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 42, 647–674 (2019).

Kato, Y., Hu, C., Wang, Y. & Kojima, A. Psychometric validity of the motivation for healthy eating scale (MHES), short version in Japanese. Curr. Psychol. 42, 3258–3267 (2021).

Di Angelantonio, E. et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 388, 776–786 (2016).

Román, N., Rigó, A., Kato, Y., Horváth, Z. & Urbán, R. Cross-cultural comparison of the motivations for healthy eating: investigating the validity and invariance of the motivation for healthy eating scale. Psychol. Health. 36, 367–383 (2021).

Mori, N., Asakura, K. & Sasaki, S. Differential dietary habits among 570 young underweight Japanese women with and without a desire for thinness: a comparison with normal weight counterparts. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 25, 97–107 (2016).

Keller, C. & Siegrist, M. Does personality influence eating styles and food choices? Direct and indirect effects. Appetite 84, 128–138 (2015).

Appleton, K. et al. Liking and consumption of vegetables with more appealing and less appealing sensory properties: associations with attitudes, food neophobia and food choice motivations in European adolescents. Food Qual. Prefer. 75, 179–186 (2019).

Yan, J. et al. Communicating online diet-nutrition information and influencing health behavioral intention: the role of risk perceptions, problem recognition, and situational motivation. J. Health Commun. 23, 624–633 (2018).

Wang, X., Shi, J. & Kong, H. Online health information seeking: a review and meta-analysis. Health Commun. 36, 1163–1175 (2020).

Al Tell, M., Natour, N., Badrasawi, M. & Shawish, E. The relationship between Nutrition Literacy and Nutrition Information seeking attitudes and healthy eating patterns in the Palestinian Society. BMC Public. Health. 23, 165 (2021).

Holbrook, M. B. Introduction to consumer value. In Consumer value 17–44. Routledge (2002).

Loureiro, S. M. C., Costa, I. & Panchapakesan, P. A passion for fashion. Int. J. Retail Distrib. 45, 468–484 (2017).

Flache, A. et al. Models of social influence: towards the next frontiers. JASSS-J Artif. Soc. S. 20, 2 (2017).

Xu, X. et al. The impact of informational incentives and social influence on consumer behavior during Alibaba’s online shopping carnival. Comput. Hum. Behav. 76, 245–254 (2017).

Parshakov, P., Permyakova, T. M. & Zavertiaeva, M. Health Information Search during COVID-19: does Culture Matter? Available SSRN 3625158 (2020).

Lu, L. & Gilmour, R. Culture and conceptions of happiness: individual oriented and social oriented SWB. J. Happiness Stud. 5, 269–291 (2004).

Andrade, C. Sample size and its importance in research. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42, 102–103 (2020).

Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* power software. J. Educ. Eval Health P. 18, 17–17 (2021).

Svendsen, M. T. et al. Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: a large national population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1–12 (2020).

Ahadzadeh, A. S., Sharif, P., Ong, S., Khong, K. W. & F. S. & Integrating Health Belief Model and Technology Acceptance Model: An Investigation of Health-Related Internet Use. J. Med. Int. Res. 17, e45 (2015).

Curvelo, I. C. G., de Morais Watanabe, E. A. & Alfinito, S. Purchase intention of organic food under the influence of attributes, consumer trust and perceived value. Revista De Gestão. 26, 2177–8736 (2019).

Gong, J. et al. Do privacy stress and Brand Trust still Matter? Implications on continuous Online Purchasing Intention in China. Curr. Psychol. 42, 15515–15527 (2022).

Tan, C. N. L. Do millennials’ personalities and smartphone use result in materialism? The mediating role of addiction. Young Consum. 25, 308–328 (2024).

Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y. & Babin, B. J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 69, 3192–3198 (2016).

Purwanto, A. & Sudargini, Y. Partial Least Squares Structural Squation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Analysis for Social and Management Research: A literature review. J. Ind. Eng. Manag Res. 2, 114–123 (2021).

Wadkar, S. K., Singh, K., Chakravarty, R. & Argade, S. D. Assessing the reliability of attitude scale by Cronbach’s alpha. J. Glob Commun. 9, 113–117 (2016).

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M. & Mena, J. A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Market Sci. 40, 414–433 (2012).

Cheung, G. W. & Wang, C. Current approaches for assessing convergent and discriminant validity with SEM: Issues and solutions. in Academy of management proceedings. Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510 (2017).

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M. & Thiele, K. O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Market Sci. 45, 616–632 (2017).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market Sci. 43, 115–135 (2015).

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24 (2019).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L. & Newsted, P. R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 14, 189–217 (2003).

Zheng, D., Luo, Q. & Ritchie, B. W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tourism Manag. 83, 104261 (2021).

Matias, T., Dominski, F. H. & Marks, D. F. Human Needs in COVID-19 Isolation871–882 (SAGE Publications Sage UK, 2020).

Beaudoin, C. E. Explaining the relationship between internet use and interpersonal trust: taking into account motivation and information overload. J. Comput-Mediat Commun. 13, 550–568 (2008).

Renwick, S. Ranking of scenarios, actors and goals of food security: motivation for information seeking by food security decision makers. Environ. Syst. Dec. 40, 444–462 (2020).

Zhu, W., Yao, N. C., Ma, B. & Wang, F. Consumers’ risk perception, information seeking, and intention to purchase genetically modified food: an empirical study in China. Brit Food J. 120, 2182–2194 (2018).

Khalid, B. Entrepreneurial insight of purchase intention and co-developing behavior of organic food consumption. Pol. J. Manag Stud. 24, 142–163 (2021).

Ellison, K., Truman, E. & Elliott, C. Picturing food: the visual style of teen-targeted food marketing. Young Consum. 24, 352–366 (2023).

Mir, I. A. A motivational cognitive mechanism model of online social network advertising acceptance: the role of pre-purchase and ongoing information seeking motivations. J. Creat Commun. 16, 314–330 (2021).

Chung, Y. S., Wu, C. L. & Chiang, W. E. Air passengers’ shopping motivation and information seeking behaviour. J. Air Transp. Manag. 27, 25–28 (2013).

Chahar, B. Psychological contract and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: exploring the interelatedness through Cross Validation. Acad. Strate Manag J. 18, 1–15 (2019).

Thirakulwanicha, A., Dragolea, L. & Fekete-Farkas, M. Gamification and Learning: enhancing and engaging E-learning experience. Glob J. Entre Manag. 1, 16 (2020).

Kickul, J., Lester, S. W. & Belgio, E. Attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of psychological contract breach: a cross cultural comparison of the United States and Hong Kong Chinese. Int. J. Cross Cult. Man. 4, 229–252 (2004).

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., Costa, P., Doden, S., Chang, C. & W. & Psychological contracts: past, present, and future. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psych. 6, 145–169 (2019).

Ting, H., Tham, A. & Gong, J. Responsible Business–A timely introspection and future prospects. Asian J. Bus. Res. 12, 1–7 (2022).

Muangmee, C., Kot, S., Meekaewkunchorn, N., Kassakorn, N. & Khalid, B. Factors determining the behavioral intention of using food delivery apps during COVID-19 pandemics. J. Theor. Appl. El Comm. 16, 1297–1310 (2021).

Stamps, D. L., Mandell, L. & Lucas, R. Relational maintenance, collectivism, and coping strategies among black populations during COVID-19. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 38, 2376–2396 (2021).

Yeonga, S. W., Sandhua, M. K., Tonera, A. M. & Anak, S. Promotion of Education for Sustainable Development among Hospitality and Tourism students: results and challenges during COVID-19. J. Respon Tourism Manag. 1, 18–27 (2021).

Nuseir, M. T. The impact of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) on the online purchase intention of consumers in the islamic countries–a case of (UAE). J. Islamic Market. 10, 759–767 (2019).

Ismagilova, E., Slade, E. L., Rana, N. P. & Dwivedi, Y. K. The effect of electronic word of mouth communications on intention to buy: a meta-analysis. Inf. Syst. Front. 22, 1203–1226 (2020).

Bakewell, C. & Mitchell, V. W. Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles. Int. J. Retail Distrib. 31, 95–106 (2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZG did the first draft. FS and WH did the data analysis . JKG and IA did the review and proofreading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was sought from the Research Ethics Committee at the Krirk University Thailand in this study with protocol No.KRE103694. The research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, Y., Said, F., Haq, W. et al. The impact of health information seeking and social influence on functional food purchase intention. Sci Rep 15, 4212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87343-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87343-7