Abstract

The 3C-like protease (3CLpro) is essential in the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle and a promising target for antiviral drug discovery, as no similar proteases exist in humans. This study aimed to identify effective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors among FDA-approved drugs. Previous computational analysis revealed several drugs with high binding affinity to the 3CLpro active site. In vitro enzymatic assays confirmed that ten of these drugs effectively inhibited the enzyme. To evaluate their impact on viral replication, we used non-infectious SARS-CoV-2 sub-genomic replicons in lung and intestinal cells. Amcinonide, eltrombopag, lumacaftor, candesartan, and nelfinavir inhibited replication at low micromolar concentrations. Lumacaftor showed IC50 values of 964 nM in Caco-2 cells and 458 nM in Calu-3 cells, while candesartan had IC50 values of 714 nM and 1.05 µM, respectively. Furthermore, dual combination experiments revealed that amcinonide, pimozide, lumacaftor, and eltrombopag acted as potent inhibitors at nanomolar concentrations when combined with candesartan. This study highlights lumacaftor, candesartan, and nelfinavir as effective inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro and emphasizes their potential for repurposing as antiviral treatments. These findings support future clinical trials and may lead to breakthroughs in COVID-19 treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 main protease, known as 3CLpro (also referred to as Mpro or nsp5), is a crucial enzyme involved in viral replication and transcription1. After membrane fusion, the genomic RNA (gRNA) of SARS-CoV-2 is released into the cytosol of the host cell, where it contains two large replicase ORFs, ORF1a and ORF1b2,3. These ORFs encode two N-terminal polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, respectively2,3. 3CLpro primarily cleaves these polyproteins at over 11 conserved sites, facilitating the release of non-structural proteins (nsps). These nsps play a role in the production of subgenomic RNA, which encodes four major structural proteins and other auxiliary proteins.

Multiple alignments of the amino acid sequences for the 3CLpro enzyme from SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, HKU4, and SARS-CoV-2 have revealed that the catalytic amino acid pair (Cys145 and His41) is conserved across these viruses. The crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2’s 3CLpro enzyme confirms that the positions of this catalytic pair are preserved, similar to those observed in other coronaviruses family (PDB IDs: 6Y84, 6Y2E, 6LU7, 7BQY)4. Since no human protease shares a similar structure with 3CLpro, it represents an attractive target for SARS-CoV-2 therapy5.

Efforts to develop drugs against the globally impactful SARS-CoV-2 virus began immediately after its emergence. Approaches such as high-throughput molecular screening, computer-aided drug design, and drug repurposing have been used to target various stages of the coronavirus life cycle by focusing on interaction sites or, when applicable, active sites of viral proteins3,6,7,8,9,10,11. Most of the reported 3CLpro inhibitors are peptide-based molecules that covalently bind to Cys14511,12,13. Although these covalent inhibitors are effective, they may cause side effects due to off-target binding14. Conversely, some non-covalent inhibitors with lower affinity have also been reported15,16. Since drug development is both time-consuming and expensive, repurposing FDA-approved drugs for new diseases like COVID-19 can offer substantial savings in time and cost. In our previous in silico studies, we targeted the active site of the 3CLpro enzyme, which includes the catalytic amino acids His41 and Cys145. We calculated the binding energies of 3498 FDA-approved drug molecules to this target site using docking followed by molecular dynamics simulations17 (Table 1).

The limited accessibility of BSL3 laboratories, required for live SARS-CoV-2 experiments, and the associated high costs, effort, and biosafety risks, hinder research and drug development. To overcome these challenges, synthetic replication systems with high biosafety levels are used, allowing work in BSL2 labs. These systems replicate viral genomic material while preventing the formation of infectious particles, thus enabling safe handling. Reporter genes, such as luciferase (LUC) or green fluorescent protein (GFP), can be included in the synthetic genome to monitor viral replication in cells. To accelerate SARS-CoV-2 drug development, various groups have designed and demonstrated the functionality of subgenomic replicons18,19,20,21,22.

In this study, we aimed to identify inhibitors of 3CLpro, and consequently SARS-CoV-2, by repurposing well-tolerated, widely used drugs, guided by our previous computational studies17. To this end, we tested 27 FDA-approved drugs using in vitro enzymatic assays and biosafe SARS-CoV-2 replicon assays in Calu-3 (human lung adenocarcinoma) and Caco-2 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) cell lines. Our results revealed that ten drugs effectively inhibited 3CLpro activity. Notably, including amcinonide, eltrombopag, lumacaftor, candesartan, and nelfinavir, significantly suppressed SARS-CoV-2 replication at micromolar concentrations in both cell lines. Lumacaftor and candesartan, in particular, demonstrated potent antiviral activity with IC50 values in the nanomolar range. Furthermore, combination therapies enhanced the antiviral efficacy of these drugs, underscoring their potential for therapeutic use against SARS-CoV-2.

Materials and methods

Identification of candidate drugs

The binding energies of drugs to the active site of 3CLpro were analyzed using computational and structural biology methods, with the results published by our group17. Based on these findings, 27 widely used drugs with the highest binding affinities were selected as potential inhibitors. For clarity and readability in the graphs, the drugs are referred to by their code names, as listed in Table 1.

Cell lines and culture conditions

Calu-3 (Human Lung Adenocarcinoma, ATCC HTB-55), Caco-2 (Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma, ATCC HTB-37) and Huh7 (Human Hepatocellular, obtained from Ege University, Department of Bioengineering, Animal Cell Culture Stocks) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (PES, Gibco; 10,000 U/ml penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin), and filtered through a 0.22 μm sterile filter (Millipore). Cell cultures were grown in an 85% humidified incubator at 37 °C supplied with 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured with Trypsin/EDTA (0.25%:0.02%, PAN Biotech) when they reach confluency.

Cell viability assay

In Calu-3 and Caco-2 cell lines, the non-toxic doses of the molecules were determined using the xCelligence RTCA-DP real-time cell analysis system (Acea Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), which enables continuous and real-time monitoring of cell proliferation and death based on the electrical impedance response23. Cells were seeded in 16-well e-plates at a density of 15 × 10³ cells per well for the Calu-3 and 10 × 10³ cells per well for the Caco-2 cell line. Following cell seeding, the e-plates were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in a sterile laminar flow hood, and then placed in the xCelligence-DP device and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The xCelligence-DP device has been instructed to take measurements every 15 min. After 24 h (corresponding to one-third of the cell proliferation phase), the medium in the e-plates was replaced with medium containing all molecules at concentrations of 50, 10, 2, and 0.4 µM (2 replica for each cell line). Measurements were taken every 15 min for 72 h. The graphs of cell index values dependent on dose and time were directly transferred to the computer screen. Graphs obtained based on the specified concentrations and ~ 100 h of time were analyzed to determine the safe dose ranges for each molecule.

In vitro 3CLpro enzymatic activity assay

Using non-toxic doses of the identified molecules, we investigated their ability to inhibit the in vitro enzymatic activity of the virus’s main protease, 3CLpro, using the 3CL Protease (SARS-CoV-2) Assay Kit (Bioscience Catalog No: 78042-2). The 3CLpro enzymatic activity assay was performed in 384-well black opaque plates (BPS Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), with each experiment conducted in duplicate. The steps of the protocol are as follows: (1) DTT was added to the 3CL Protease Buffer solution to achieve a final concentration of 1 mM. (2) The 3CL protease enzyme was dissolved in the solution prepared in step 1 to achieve a final concentration of 1.5 ng/µL. (3) 10 µL of the enzyme solution prepared in step 2 was added to the wells to be tested. (4) The GC376 molecule (protease inhibitor) used as a positive control was dissolved in water to a final concentration of 1000 µM, and 2.5 µL was added to the wells. To obtain readings for “blank”, only 10 µL of enzyme buffer solution was added. (5) For each molecule with different concentrations to be investigated, 2.5 µL was added to the wells. The total amount of DMSO added to the wells was kept at or below 1%. (6) As a control group, a mixture of DMSO and water was added to the wells at a volume of 2.5 µL. (7) The enzyme containing molecules were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. (8) The 10 mM 3CL protease substrate was diluted 1:125 with the solution prepared in step 1, and 12.5 µL was added to each well (resulting in a final substrate concentration of 40 µM). (9) The plate was covered with optical film and incubated at room temperature with shaking for 4 h. Subsequently, fluorescence intensity was measured for 6 h with excitation at 360 nm and emission at 460 nm using Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments). The most suitable temperature for the experiment was optimized as 28 °C. Readings from the “blank” wells were subtracted from other values, and the results were normalized to the control.

Initially, the in vitro protease activity of all molecules was analyzed at a concentration of 50 µM. Subsequently, 10 molecules that inhibited the activity by 50% or more were identified. To evaluate the effectiveness of these molecules at lower doses and calculate their IC50 values, dose-dependent (25, 5, and 1 µM) in vitro enzymatic activity tests were performed (to investigate the dose-dependent effects of the drugs, the main stock drug solution was diluted to the specified concentrations, ensuring that the amount of DMSO in each well remained consistent). Using GraphPad software (version 8.0.2, CA, USA) module of enzyme kinetics analysis (inhibitor vs. normalized response) by fitting a Hill curve, the IC50 values of the molecules were calculated.

The 10 molecules identified as having inhibitory activity were tested in combinations starting from their IC50 values and decreasing in dose. For each combination experiment, the dose of one molecule was kept constant at its IC50 value, while the dose of the other molecule was reduced by a factor of three, and three different doses were tested. Subsequently, the dose of the first drug was reduced by a factor of three from its IC50 value, and the dose of the second drug was similarly reduced by a factor of three for testing.

SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic replicon

The ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid and VSV-G plasmid, generated by replacing the ORF region of the synthetic genome with sequences encoding Gaussia luciferase (luc) and green fluorescent protein (GFP), is generously gifted from Prof. Manicassamy from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Iowa, USA. This single-cycle infectious SARS-CoV-2 viral replicon particle system (ΔS-VRP) with a luciferase and green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter enables studies under BSL2 conditions18.

Generation of ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid

Using a bacterial artificial chromosome, the spike gene of SARS-CoV-2 was replaced with a dual reporter system comprising Luc and GFP18. This modification allows the ΔS-Luc-GFP genome to undergo normal transcription and replication following transfection into cells; however, due to the absence of the spike gene, it is incapable of producing infectious virus particles. Consequently, the formation of infectious particles containing the ΔS-Luc-GFP genome necessitates the expression of the spike protein or another viral glycoprotein/protein in the producer cells. Infectious VRPs [ΔS-VRP(G)] were rescued by co-transfecting the ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid with a VSV-G expression plasmid into a mixture of Huh7 cells. The protocol for this system is detailed as follows:

The ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid and VSV-G plasmid were transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells made competent with calcium chloride. The competent cells were allowed to thaw on ice. 50 µl of competent cells were added to 30 ng of plasmid and incubated on ice for 30 min. Following a 45-second heat shock at 42 °C, the cells were placed back on ice for an additional 10 min. Subsequently, 800 µl of room temperature LB medium was added to the DNA-competent cell mixture, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm for 1 h. After incubation, the cells were plated on LB agar plates containing 5 µg/ml chloramphenicol for the ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid and 100 µg/ml ampicillin for the VSV-G plasmid, and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Glycerol stocks were prepared from the transformed plasmids for long-term storage. The ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid plasmid was purified using the QIAGEN® Large-Construct Kit (CAT. No. 12462, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN Large-Construct Kit Protocol).

Amplification of ΔS-VRP (G)

One day prior to transfection, Huh-7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 4 × 105 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. On the following day, when the cells reached 70–80% confluence, they were transfected with 3.5 µg of ΔS-Luc-GFP bacmid and 0.5 µg of VSV-G plasmid using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (InvitrogenTM,Thermo Scientific). To assess transfection efficiency, 3.0 µg of pcdna and 0.5 µg of eGFP plasmid were used as a positive control. In the DNA-containing medium, 8 µl of P3000™ (equivalent to twice the total plasmid amount) was added and mixed thoroughly. The Lipofectamine™ 3000 solution was then combined with the DNA solution in a 1:1 ratio and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The resulting DNA-Lipofectamine mixture was added dropwise to each well and incubated for 5 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 5 hours, the transfection medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% heat-inactivated FBS. To evaluate transfection efficiency and monitor the spread of the ΔS virus, GFP and luciferase expression in the supernatant were regularly assessed. 48–72 h after the initial transfection, the cells were re-transfected with 2 µg of VSV-G plasmid using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (InvitrogenTM,Thermo Scientific). 48 h after the second transfection (VSV-G), the cell supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 1750 g for 10 min (Beckman Coulter Allegra X-30R). The resulting ΔS-VRP(G) stocks were labeled and stored at -80 °C for further amplification.

Scale-up production of ΔS-VRP(G) stocks

One day prior to transfection, Huh-7 cells were passaged into 100 mm dishes at 70–80% density (~ 4 × 106 cells) for the next day. The following day, 10 µg of VSV-G plasmid was transfected into cells using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (InvitrogenTM,Thermo Scientific) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 5 h. After 5 h, the transfection medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The next day, VSV-G-transfected Huh-7 cells were infected with 0.5 ml of ΔS-VRP(G) in 4.5 ml of DMEM with 2% FBS, and incubated at 37 °C for 2–3 h with periodic shaking every 20 min. After incubation, the medium was replaced with 12 ml of DMEM containing 2% FBS. Cells were monitored for GFP expression and cytopathic effects, and luciferase activity in the supernatants was assessed. 24–48 h post-infection, the supernatants were collected, centrifuged at 1750 g for 10 min (Beckman Coulter Allegra X-30R) and the pellets were discarded. The supernatants were then stored in 15 ml Falcon tubes at -80 °C.

Rescue and amplification of ΔS-VRP(G)

One day before infection, Calu-3 and Caco-2 cells were seeded according to the experimental plan. For Caco-2, 1.2 × 105 cells/well were seeded in 12-well and 6 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates. For Calu-3, 2 × 105 cells/well were seeded in 12-well and 6 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates. Following day, medium was removed from the cells, and they were infected with ΔS-VRP(G) (500 µl per well for 12-well; 300 µl per well for 24-well plates) for 2–3 h. During this time, the test molecules and their doses were prepared in DMEM containing 2% FBS. After the 2–3 h incubation, the cells were carefully washed twice with PBS and fresh DMEM containing 2% FBS was added. 16–18 h post-infection, nano-luc luciferase readings for each molecule dose and its replicates (n = 2) were obtained using a 96-well plate. Prior to this, Coelenterazine h (Nanolight Technology, D-Luciferin - CAT #301–500) was added (1:400) to pre-warmed ‘Renilla Salt’ solution and mixed. The resulting mixture (50 µl per well) was added to each well, and Nano-luc readings were quickly acquired using the BioTek Cytation 5 system. The results were analyzed by normalizing to the control.

Docking, molecular dynamics simulation and interaction analyses

All calculations and methods were performed as previously described with some differences8,17,24. The high-resolution structure with PDB ID 6y84 was used as a template for the 3CLpro protein25.

The GC376 molecule has been shown to bind to the enzyme by forming a covalent bond with Cys145 and hydrogen bonds with other amino acids in the active site, with its binding site for 3CLpro located at the N-terminus. Docking simulations were conducted on the GC376 binding pocket, with the grid box set at the center of amino acid residues His41, Met49, Asn142, Gly143, Cys145, Glu166, Leu167 and Gln189, having dimensions of 22 × 24 × 24 ų. Docking was performed using AutoDock Vina (v. 1.1.2)26.

Solvation of the drug–3CLpro complexes was achieved by surrounding the systems with TIP3P water molecules, positioned at a distance of 15 Å from the outermost protein atom, using the VMD Tk-console27. To mimic physiological conditions, the solubilized protein systems were neutralized and subsequently ionized with sodium and chloride ions to achieve a final ionic concentration of 150 mM. Following minimization, the systems underwent gradual heating and equilibration in the NPT ensemble for 1.4 ns, with constraints applied to the Cα atoms of all amino acids. These constraints were initially set at 2 kcal/mol/Ų and systematically reduced by 0.5 kcal/mol/Ų every 0.4 ns during the equilibration. Subsequently, 100 ns production simulations were carried out for each selected inhibitor–3CLpro complex at 310 K and 1 atm pressure with a 2 fs time step. Temperature and pressure were controlled using the Langevin thermostat and barostat, respectively. The force calculations included Van der Waals interactions with a 12 Å cutoff, while long-range electrostatic interactions were handled via the particle mesh Ewald method. All MD simulations employed the CHARMM36m force field28 implemented through the NAMD software package29. Topology and force-field parameters for the drug molecules were generated using the CHARMM-GUI online server30.

Protein–inhibitor interactions were analyzed as follows: The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of Cα atoms was calculated using the RMSD tool in VMD, with the initial frame of the production simulation serving as the reference. The frequency of contacts between the drug and neighboring amino acid residues was analyzed to identify binding residues, using the Timeline plugin in VMD. Visualization and figure preparation of protein–drug complexes were conducted using VMD27 and PyMOL 2.5.0 (open source; http://pymol.sourceforge.net/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was calculated for each condition compared to the control group using one-way ANOVA (non-parametric) test. Data were represented with mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0005; ****p < 0.0001.

Results

Real-time cytotoxicity and cell index measurements

The non-toxic maximum concentration for the 27 selected molecules, which will be used in subsequent cell culture studies with Calu-3 and Caco-2 cell lines, was determined using the xCELLigence RTCA-DP system. The basic principle of this system is based on the phenomenon that as the number of cells adhering to the e-plate surface with gold electrodes increases, the resistance against the current increases, and as the number of adhered cells decreases, the resistance correspondingly decreases. Through the xCELLigence RTCA-DP system, cell proliferation and cell death can be recorded in real-time and continuously. Detailed results for each drug were provided in Figures S1 and S2.

Among 27 drugs tested on the Calu-3 cell line, cell proliferation generally increased up to a concentration of 50 µM. Comparing the cell index values obtained after drug treatment with the control, it was observed that no cytostatic effect occurred. However, pimozide (B11) at 50 µM, ciclesonide (B12) at 50 µM, darifenacin (B25) at 25 and 50 µM after a certain period, and eltrombopag (Elt) at 50 µM reduced cell proliferation compared to the control (Figure S1). Therefore, these toxic concentrations were excluded from subsequent in vitro protease assays. Similarly, in the 27 drugs tested on the Caco-2 cell line, cell proliferation generally increased up to a concentration of 50 µM. Comparing the cell index values obtained after drug treatment with the control, no cytostatic effect was observed. However, ciclesonide (B12), simeprevir (B18), and eltrombopag (Elt) exhibited toxic effects at 50 µM, halting cell proliferation (Figure S2). These concentrations were not used in further in vitro studies and cell culture experiments.

Effect of drugs on in vitro 3CLpro enzymatic assay

The effect of the selected molecules on 3CLpro enzyme activity was assessed using the 3CLpro enzymatic assay kit (Bioscience Catalog No: 78042-2). The experiments were carried out in a 384-well plate format, with each assay performed in duplicate. The GC376 inhibitor served as the positive control, while the 3CLpro enzyme treated solely with DMSO acted as the negative control. In this assay, the 3CLpro enzyme cleaves the substrate as it becomes active, producing a fluorescent signal that can be quantified. The tested molecules were added to the wells, ensuring that the DMSO concentration did not exceed 1%.

The maximum non-toxic doses, determined from toxicity analyses, were used to screen for potential inhibitors. Molecules exhibiting inhibitory properties were subsequently tested at serially decreasing concentrations to calculate their IC50 values. To ensure consistency across wells, the primary stock solutions were diluted to maintain a uniform DMSO concentration.

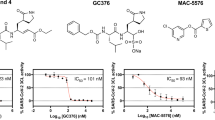

The inhibitory effects of the molecules were normalized against the reaction rate obtained from the DMSO-treated 3CLpro enzyme. The single-dose screening indicated that 10 molecules (Cnd, Elt, B2, B5, B7, B9, B11, B21, B22, and B23) inhibited in vitro protease activity by 50% or more (Fig. 1). To determine the IC50 values for these compounds, dose-dependent analyses were performed using the in vitro enzymatic activity assay. The dose-dependent inhibitory profiles for these 10 molecules are shown in Fig. 2A. IC50 values were calculated using enzyme kinetics analysis (inhibitor vs. normalized response) by fitting a Hill curve in GraphPad Prism (Fig. 2B). Among the tested drugs, B5 (0.30 µM), Elt (7.5 µM), Cnd (15.6 µM), B22 (13.7 µM), and B21 (28.8 µM) exhibited the lowest IC50 values (Table 2). (Note: although B11 demonstrated toxic effects at 50 µM, this concentration was included in the IC50 determination as the upper dose).

Effects of 27 selected molecules at a single dose (50 µM) on in vitro 3CLpro enzymatic activity. Enzymatic activity was normalized to the control group (DMSO), which was set at 100. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 2, with duplicates). The enzymatic activity rate was determined by dividing the fluorescence readings—recorded during the linear phase of product formation—by the corresponding time intervals. All other values were normalized to the control group, with its activity defined as 100.

Combinatory effect of inhibitor molecules on in vitro 3CLpro activity

Since the drugs can bind to the enzyme’s target site in different conformations, it was hypothesized that two drugs could synergistically block the enzyme more effectively at lower doses. Therefore, the 3CLpro enzyme was treated with combinations of molecules demonstrating inhibitory activity. The synergistic inhibitory effect on 3CLpro was assessed by combining molecules starting from their individually determined IC50 values and testing them at decreasing doses. The top five molecules showing the best efficacy on their own—B5 (IC50 = 0.3 µM), B22 (13.7 µM), B21 (28.8 µM), Elt (7.5 µM), and Cnd (15.6 µM)—were selected for combination studies. The following ten combinations were tested: B5/B22, B5/B21, B5/Elt, B5/Cnd, B22/B21, B22/Elt, B22/Cnd, B21/Elt, B21/Cnd, and Elt/Cnd. For each combination experiment, one molecule’s dose was kept constant at its IC50 value, while the other molecule’s dose was decreased by a factor of 3 across three concentrations. The roles were then reversed, with the first drug’s dose reduced by a factor of 3 and the other drug similarly tested at its IC50 value and decreasing concentrations. For example, in the B5/Elt combination, 7.5, 2.5, and 0.8 µM doses of Elt were tested for each 0.3-0.1-0.033 µM doses of B5. For combinations where inhibition dropped below 40% after dose reduction (B5/B22, B5/Cnd, B5/B21, Elt/B21, B22/Cnd), further lower doses were not tested (Figure S3). The normalized enzymatic activity values of 3CLpro relative to the control group at the specified concentrations are displayed as a bar graph (Fig. 3A). The in vitro enzymatic activity of 3CLpro for the combination experiments is presented as a heat map (Fig. 3B). Combinations of B5/Elt, B22/Elt, Elt/Cnd, and B22/B21 drugs resulted in 50% or greater inhibition at specific doses.

Impact of inhibitors in combinations on 3CLpro activity. (A) Combined effect of B5, B22, B21, Elt and Cnd molecules, known to inhibit protease activity, at varying concentrations. In each experiment, the control group (DMSO-treated) was normalized to 100. The bar graphs depict enzymatic activity values relative to this control group across different concentrations of the specified molecules. Statistical significance was calculated for each condition compared to the control group using one-way ANOVA (non-parametric) test. (Data represent mean and the standard error of the mean ± SEM, n = 2 with duplicates (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0005; ****p < 0.0001). (B) The inhibitory effects of molecular combinations were depicted as a heatmap. Values within the boxes represent 3CLpro activity, where darker colors with lower numbers indicate higher inhibition, and lighter colors with higher numbers indicate lower inhibition. A value of 100 on the heatmap corresponds to the enzymatic activity in the control group (DMSO).

To quantify these effects, the IC50 values for the molecules were calculated using enzyme kinetics analysis (inhibitor vs. normalized response) in GraphPad Prism by fitting Hill curves. The IC50 calculations took into account the inhibition observed at decreasing doses of one molecule while the other molecule’s dose remained constant. Thus, the IC50 value of the varying molecule was calculated in the presence of the non-varying molecule. The curves obtained from these analyses are shown in Fig. 4 and IC50 values are presented in Table 3. These IC50 values in Table 3 were determined by keeping the molecules listed horizontally constant while varying the doses of the molecules listed in the columns. In the combination experiments, the IC50 values of the molecules decreased by approximately 2–6 times compared to their values when used individually, indicating that their efficacy improved with combined use. Next, the effect of the best inhibitor candidate drugs on the replication of SARS-CoV-2 was tested in cell culture conditions.

Representation of nonlinear regression with the log inhibitor vs. normalized response, with the Hill slope set to -1.0 for in vitro combination experiments. Inhibition was measured for B5 at decreasing doses (0.3, 0.1, 0.033 µM) while Elt was kept constant at 7.5 µM; for Elt at decreasing doses (7.5, 2.5, 0.8 µM) while B5 was kept constant at 0.3 µM; for B22 at decreasing doses (13.7, 4.6, 1.5 µM) while Elt was kept constant at 7.5 µM; for Elt at decreasing doses (7.5, 2.5, 0.8 µM) while B22 was kept constant at 13.7 µM; for Cnd at decreasing doses (15.6, 5.2, 1.7 µM) while Elt was kept constant at 7.5 µM; and for Elt at decreasing doses (7.5, 2.5, 0.8 µM) while Cnd was kept constant at 15.6 µM.

Impact of in vitro inhibitor molecules on SARS-CoV-2 replicon replication in cell culture

To better understand the effects of inhibitory molecules identified through in vitro assays on SARS-CoV-2 replication in cell culture, we employed a subgenomic replicon of the virus. This system, a single-cycle infectious SARS-CoV-2 viral replicon particle (ΔS-VRP) with luciferase and green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporters, allows for studies under BSL2 conditions18. We assessed the impact of these molecules on SARS-CoV-2 replication in two different cell types, Calu-3 and Caco-2 cells. The synergistically most effective molecules determined through in vitro assays—B5, B11, B21, B22, Elt, and Cnd— were tested in this cell-based assay. As detailed in the method section, the SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic replicon was introduced into Calu-3 and Caco-2 cells. 4-h post-transfection, the wells were treated with the selected molecules with doses ranging from slightly above the IC50 values, starting from 5 µM and serially diluted fivefold down to 1, 0.2, 0.04, and 0.008 µM (5000, 1000, 200, 40, and 8 nM). The compounds were diluted from the main stock using serial dilution to ensure the same amount of solvent (DMSO) in all wells, with the final DMSO concentration not exceeding 0.5%. The same amount of DMSO was added to control wells as in the drug-treated wells. 18-hours after drug treatment, the cells were collected, and luciferase activity was measured. Non-transfected cells served as the negative control. Luciferase readings were normalized relative to the DMSO control group and reported accordingly (Fig. 5). The IC50 values of the molecules were determined by fitting a Hill curve to enzyme kinetics data (inhibitor vs. normalized response) using GraphPad Prism software (Table 4) (Figure S4).

Effect of 3CLpro inhibitors on the replication of SARS-CoV-2 replicon in (A) Calu-3 (B) Caco-2 cell line. Luciferase readings were normalized to the control group (DMSO) and set as 100. Cells that were not transfected with the SARS-CoV-2 replicon was named as Untreated group. Statistical significance was calculated for each condition compared to the control group using one-way ANOVA (non-parametric) test. Data represent mean and the standard error of the mean ± SEM, n = 4–5 (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0005; ****p < 0.0001.

The B22 molecule/drug exhibited activity below the micromolar range, with an IC50 of 458 nM in the Calu-3 (Fig. 5A) and 964 nM in the Caco-2 cell line (Fig. 5B). The Cnd drug showed an IC50 value of 714 nM in the Caco-2. In the Calu-3 cell line, the same drug reached an IC50 value at a low micromolar concentration (1.05 µM). Other drugs tested on this experimental setup showed 2–5 µM IC50 values (Table 4).

Evaluating the combined effects of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitory drugs in Calu-3 and Caco-2 cells

The best inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replicon replication in single-drug tests in Calu-3 and Caco-2 cell lines—B5, B11, B22, Cnd, and Elt—were selected for combination studies. The following combinations were tested at four different doses each: B22-Cnd, B22-B5, Cnd-B5, Cnd-B11, Cnd-B21, Cnd-Elt, and Elt-B5. In each experiment, 16 doses were tested, as exemplified for the B22-B5 combination (Figure S5). When cells were treated with two drugs, DMSO was added at a concentration not exceeding 0.5%. Since the highest IC50 in the single-drug tests was around 5 µM (Table 4), and to ensure consistency across experiments, the highest dose in the combination studies was set at 5 µM, followed by four serial dilutions at a fivefold decrease. The doses tested were 5, 1, 0.2, and 0.04 µM (5000, 1000, 200, and 40 nM). The obtained data were normalized to control readings (cells treated only with DMSO) and presented as bar graphs (Fig. 6). To ensure that no potentially effective drug combinations were missed, the following pairs were tested at a single dose in both cell lines: Elt/B11, Elt/B21, Elt/B22, B5/B11, B5/B21, B11/B21, B11/B22, and B21/B22 (Figure S6).

(A) Effect of selected molecules in combination on the replication of SARS-CoV-2 replicon in Caco-2 cell lines. Luciferase readings were normalized to the control group (DMSO) and set as 100. Cells that were not transfected with the SARS-CoV-2 replicon was named as Untreated group. Statistical significance was calculated for each condition compared to the control group using one-way ANOVA (non-parametric) test. Data represent mean and the standard error of the mean ± SEM, n = 4–5 (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0005; ****p < 0.0001). (B) The inhibitory effects of molecular combinations were depicted as a heatmap. Values within the boxes represent replication level of SARS-CoV-2 replicon in Caco-2 cell line, where darker colors with lower numbers indicate higher inhibition, and lighter colors with higher numbers indicate lower inhibition. A value of 100 on the heatmap corresponds to the replication in the control group (DMSO). (C) Effect of selected molecules in combination on the replication of SARS-CoV-2 replicon in Calu-3 cell lines. Luciferase readings were normalized to the control group (DMSO) and set as 100. Cells that were not transfected with the SARS-CoV-2 replicon were named as Untreated group. Statistical significance was calculated for each condition compared to the control group using one-way ANOVA (non-parametric) test. Data represent mean and the standard error of the mean ± SEM, n = 4–5 (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0005). (D) The inhibitory effects of molecular combinations were depicted as a heatmap. Values within the boxes represent replication level of SARS-CoV-2 replicon in Calu-3 cell line, where darker colors with lower numbers indicate higher inhibition, and lighter colors with higher numbers indicate lower inhibition. A value of 100 on the heatmap corresponds to the replication in the control group (DMSO).

According to these results, in the presence of a specific dose of Cnd (candesartan), the molecules B5 (amcinonide), B11 (pimozide), B22 (lumacaftor), and Elt (eltrombopag) can exhibit activity at the nanomolar (nM) level in Caco-2 cells, while B11 (pimozide) and Elt (eltrombopag) can do so in Calu-3 cells. Although the concentration of Cnd (candesartan) remains at the micromolar (µM) level, the activity of the other molecules has been reduced to the nanomolar range.

Binding mode of inhibitory molecules on 3CLpro

The way a ligand binds to a protein’s active site and the strength of this binding directly impact the drug’s efficacy. To explore this structure-function relationship, the 2D structures of inhibitory molecules were analyzed using PyMOL and LigPlot + software. The 2D structures of six inhibitory drugs—candesartan, eltrombopag, amcinonide, pimozide, nelfinavir, and lumacaftor—identified in the study are shown in Figure S7. Analysis of the docking results for these six drugs from our previous study17 revealed that they interact with the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 primarily through their carboxyl groups (-COOH) (Fig. 7A). Carboxyl groups are thought to enhance binding stability by forming strong interactions via hydrogen bonds and electrostatic forces. In addition to carboxyl groups, eltrombopag, nelfinavir, and pimozide also interact with the enzyme’s active site through amino groups (-NH2) or amide groups (-CONH-). These groups form hydrogen bonds and establish polar interactions, which are believed to strengthen drug-enzyme binding.

(A) Visualization of docking simulations of inhibitors with the crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (PDB ID: 6Y84) using PyMOL. Candesartan (Cnd) is colored blue, eltrombopag (Elt) is orange, amcinonide (B5) is purple, pimozide (B11) is green, nelfinavir (B21) is pink, and lumacaftor (B22) is yellow. 3CLpro was shown in white ribbons, red sticks represent the catalytic amino acids His41 and Cys145. (B) Interaction of inhibitor molecules with the protein shown using LigPlot+. The following inhibitors are depicted: (1) Candesartan (Cnd), (2) Eltrombopag (Elt), (3) Amcinonide (B5), (4) Pimozide (B11), (5) Nelfinavir (B21), (6) Lumacaftor (B22). Nitrogen (N) is shown in blue, oxygen (O) in red, carbon (C) in green, phosphorus (P) in pink, and sulfur (S) in yellow. Phosphorus atoms are highlighted in brick red to indicate hydrophobic residues. Red dashed lines represent hydrophobic interactions, while black lines denote covalent bonds within the chemical structure of the ligand. (C) RMSD analysis of MD simulations. RMSD of Cα atoms of 3CLpro were plotted and labeled as “RMSD of Protein”. RMSD of all atoms of inhibitors in inhibitor-3CLpro simulations were plotted and labeled as “RMSD of Inhibitors”. (D) Interaction frequency of inhibitors with amino acids in the active site of 3CLpro throughout the 100 ns simulation obtained from VMD timeline plugin.

To gain insights into the amino acids near the drugs in the active site of 3CLpro, a 2D visualization of the docking results was performed, and the interactions of the inhibitory molecules with amino acids were analyzed in detail using LigPlot+ software (Fig. 7B). His41, Met49, Glu166, and Gln189 are amino acids that interact with all the molecules. The imidazole ring in the histidine side chain forms hydrophobic interactions through hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions, depending on its protonation state. The sulfur-containing side chain of methionine supports molecule binding through hydrophobic interactions. Glutamine and glutamate influence the binding site’s polarity by forming hydrogen bonds with their polar and charged side chains. Consequently, these amino acids play a crucial role in facilitating the binding of inhibitor molecules to the active site of 3CLpro.

To gain deeper insights into the binding modes of the selected drugs within the active site of 3CLpro, we conducted 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for the enzyme-molecule complexes. As a reference, GC376—a well-characterized 3CLpro inhibitor with a defined binding mode—was also simulated for comparison13,31. Although GC376 is a covalent inhibitor of 3CLpro, we conducted docking studies to calculate its binding energy for comparative purposes. The binding energies of GC376 and our repurposed drugs were found to be comparable (Table 1).

Conformational changes in 3CLpro were initially assessed by calculating and visualizing the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the Cα atoms across all simulation trajectories (Fig. 7C). All protein simulations reached equilibrium with RMSD values stabilizing around 2–3 Å. To further evaluate the molecular dynamics of the ligands, RMSD analyses were performed for all ligands (Fig. 7C). Except for candesartan, all ligands exhibited low RMSD values in the range of 3–4 Å, indicating stable retention of their docking conformations throughout the simulations. In contrast, candesartan displayed RMSD fluctuations between 2 and 7 Å, suggesting that it sampled multiple conformations during the simulation. A detailed visual inspection of the candesartan-3CLpro complex revealed that the benzimidazole group of candesartan consistently maintained its binding mode within the active site. However, other molecular regions, including the 5-phenyl-1 H-tetrazole and cyclohexyl groups flanking the benzimidazole, adopted diverse conformations during the simulation.

To evaluate the retention of all drugs within the active site, we used the timeline plugin in VMD to analyze and visualize interactions between the drugs and key amino acids in the active site. GC376-3CLpro simulations served as a control, and the binding interactions within the active site were first analyzed and visualized (Fig. 7D). GC376 demonstrated strong and consistent interactions with His41, Asn142, Gly143, Cys145, Glu166, and Gln189, along with transient interactions with Met49 and Leu167. Subsequently, the interactions of the other drugs with these critical amino acids were analyzed (Fig. 7D). Timeline plots revealed that candesartan, amcinonide, lumacaftor, and pimozide strongly and consistently interacted with His41, Met49, Glu166, Leu167, and Gln189. Notably, candesartan also formed tight interactions with Asn142, Gly143, and Cys145. On the other hand, nelfinavir and eltrombopag displayed fluctuating interactions with most of these amino acids, except for Leu167.

Collectively, our MD simulation analyses indicate that the binding and interaction modes of the repurposed drugs closely resemble those of GC376, highlighting their potential as effective 3CLpro inhibitors.

Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro enzyme is regarded as one of the most crucial drug targets for COVID-19 due to its vital role in the viral life cycle and the absence of a similar enzyme in humans. The active site of 3CLpro has been identified, and various structural and functional studies have pinpointed potential drug candidates as 3CLpro inhibitors3,7,9,12,13,16,17. Additionally, according to the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), the FDA has approved certain antiviral drugs (paxlovid, remdesivir, molnupiravir) for mild to moderate COVID-19 cases based on patient age32. In this study, we report potential SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors among well-tolerated FDA-approved drugs by leveraging computational tools, in vitro enzymatic assays, and cell-based analyses. Based on our previous computational results we selected top 27 molecules having best binding affinities to 3CLpro (Table 1)17. After determining the non-toxic doses of these molecules in Caco-2 and Calu-3 cell lines for use in subsequent analyses, we conducted in vitro enzymatic assays. Several molecules (B2, B5, B7, B9, B11, B21, B22, B23, Cnd, and Elt) inhibited 3CLpro activity by 50% or more at their maximum non-toxic doses (Figs. 1 and 2). Analysis of 10 different combinations of the best inhibitory molecules revealed that combinations such as Elt-B5, Elt-B22, and Elt-Cnd were more effective than individual treatments (Fig. 3).

Following the in vitro enzymatic assays targeting 3CLpro, we proceeded with cell culture studies to evaluate the impact of the identified drug candidates on SARS-CoV-2 replication. At this stage, we employed a specialized SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic replicon in which the spike protein was replaced with Luc and GFP genes, and the envelope, membrane, and intergenic regions were substituted with a neomycin resistance gene18. This replicon enabled us to perform the studies under BSL-2 laboratory conditions. We then tested the drugs that demonstrated inhibitory effects in the enzymatic assays on SARS-CoV-2 replication across Calu-3 and Caco-2 cell lines (Fig. 5). Individual analyses of selected drugs using the SARS-CoV-2 replicon revealed that lumacaftor (B22) and candesartan (Cnd) had IC50 values in the sub-micromolar range in both cell lines (Table 4). Other effective drugs, amcinonide (B5), pimozide (B11), and eltrombopag (Elt), displayed IC50 values between 2 and 5 µM. Subsequent combination trials with these drugs in the same experimental setup demonstrated that combining 5 µM candesartan with 200 − 40 nM of amcinonide, pimozide, lumacaftor, or eltrombopag resulted in 50% or more inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in Caco-2 cells (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the combination of candesartan with 200 nM pimozide and eltrombopag achieved 50% inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in Calu-3 cells (Fig. 6B).

The differential behavior of molecules in various cell lines could be related to differences in the types and amounts of proteins expressed between the two cell lines. Drug transport proteins and metabolizing enzymes are key determinants of intracellular drug distribution33: uptake transporters increase intracellular drug concentrations34,35, while efflux transporters36,37 and enzymes38, reduce the intracellular levels of the compounds. Additionally, the proliferation rate, cell cycle stage, and unique genetic and phenotypic characteristics of each cell line can influence how cells respond to the drug. Different cell lines may express varying isoforms of the target molecule in different amounts34, which can alter drug binding efficiency and, consequently, its biological effect39.

In line with our findings several in silico and in vitro studies reported the activity of amcinonide, pimozide, lumacaftor, eltrombopag and candesartan. For example, in a computational study targeting 3CLpro using molecular docking, 55 FDA/EMA-approved molecules containing aromatic rings or large hydrophobic groups were screened. The experimental analyses of selected drugs on 3CLpro activity reported pimozide’s IC50 value as 42.5 µM. In the same study, follow-up microneutralization assays using the basic compound pimozide, along with two other identified molecules (bepridil and ebastine), demonstrated significant inhibition of SARS-CoV-2-induced cytopathic effects in live virus studies conducted in the kidney epithelial cell line (Vero E6) isolated from the African green monkey and in human A549 cells (A549/ACE2)40. In another study, pimozide was reported to inhibit pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 in HEK293T-ACE2-TMPRSS2 cells with an IC50 value of 4.5 µM41. Additionally, several computational studies have reported that pimozide may exhibit activity as a SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor42,43.

The study highlights that the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators lumacaftor and ivacaftor inhibit SARS-CoV-2 growth in lung cells and mouse models. Disrupted CFTR expression in infected lung tissues was linked to alveolar edema, while treatments with these modulators restored CFTR levels, inhibited the virus, and improved survival rates44.

A case report published early in the COVID-19 pandemic described a patient who fully recovered from COVID-19 after treatment with eltrombopag45. The patient was an 83-year-old woman diagnosed with COVID-19, hemolytic anemia, severe immune thrombocytopenia, and bilateral pneumonia. Her thrombocytopenia did not respond to first-line treatments, including immunoglobulins, corticosteroids, and platelet transfusions. However, she fully recovered after treatment with eltrombopag. In another case, vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) occurred following the administration of an adenoviral COVID-19 vaccine. A 64-year-old woman developed severe thrombocytopenia and multiple thrombotic events after receiving the ChAdOx1-S vaccine. Her condition was unresponsive to standard therapies, but after treatment with eltrombopag, her platelet levels normalized, underscoring its potential in managing refractory thrombocytopenia in VITT46.

An early study during the COVID-19 pandemic suggested that candesartan could be a potential treatment for COVID-19 based on RNA sequencing data47. The study compared transcriptomic analyses of neurons treated with candesartan after glutamate-induced injury to transcriptional signatures from primary human bronchial epithelial cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, as well as lung and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from deceased COVID-19 patients. The RNA-Seq results indicated that candesartan modulates the expression of genes involved in inflammatory pathways and may reduce cytokine storms. By inhibiting the angiotensin II type 1 receptor, candesartan could help mitigate the excessive immune response and inflammation seen in severe COVID-19 cases47. Another computational study using free energy perturbation methods identified candesartan as a potential 3CLpro inhibitor48. Although a subsequent study using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based enzymatic assay did not confirm candesartan’s inhibitory activity49, our in vitro and cell-based assays validated its effectiveness against 3CLpro and SARS-CoV-2 replication.

Given their affordability and widespread use, eltrombopag, candesartan, pimozide, lumacaftor, and amcinonide could be employed individually or in combination as adjuncts to existing treatment protocols for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Due to their specific protein targets, these drugs are likely to exert antiviral effects during the early to mid-stages of infection, disrupting the viral replication cycle. For in vivo experiments and clinical trials, particularly in long COVID patients, these drugs should be prioritized based on their primary effects within different patient subgroups.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the manuscript (and in the Supplementary Information files).

References

Mengist, H. M., Fan, X. & Jin, T. Designing of improved drugs for COVID-19: Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease M(pro). Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5(1), 67 (2020).

Rut, W. et al. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors and activity-based probes for patient-sample imaging. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17(2), 222–228 (2021).

Jin, Z. et al. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 582(7811), 289–293 (2020).

Jin, Z. M. et al. Structure of M-pro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 582(7811), 289 (2020).

Lei, S. et al. Small molecules in the treatment of COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Targ. Ther. 7(1), 387 (2022).

Arutyunova, E. et al. N-terminal finger stabilizes the S1 Pocket for the reversible feline drug GC376 in the SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 433(13), 167003 (2021).

Dai, W. et al. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science 368(6497), 1331–1335 (2020).

Gul, S. In silico drug repositioning against human NRP1 to block SARS-CoV-2 host entry. Turk. J. Biol. 45(4), 442–458 (2021).

Iketani, S. et al. Lead compounds for the development of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 2016 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 181(4), 894–904 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved alpha-ketoamide inhibitors. Science 368(6489), 409–412 (2020).

Boras, B. et al. Preclinical characterization of an intravenous coronavirus 3CL protease inhibitor for the potential treatment of COVID19. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 6055 (2021).

Fu, L. F. et al. Both boceprevir and GC376 efficaciously inhibit SARS-CoV-2 by targeting its main protease. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1–8 (2020).

De Vita, E. 10 years into the resurgence of covalent drugs. Fut. Medicinal Chem. 13(2), 193–210 (2021).

Han, S. H. et al. Structure-based optimization of ML300-derived, noncovalent inhibitors targeting the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3CL protease (SARS-CoV-2 3CL). J. Medicinal Chem. 65(4), 2880–2904 (2022).

Lockbaum, G. J. et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in complex with the non-covalent inhibitor ML188. Viruses-Basel 13(2), 174 (2021).

Gul, S. et al. In silico identification of widely used and well-tolerated drugs as potential SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease and viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors for direct use in clinical trials. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39(17), 6772–6791 (2021).

Malicoat, J. et al. Development of a single-cycle infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus replicon particle system for use in biosafety level 2 laboratories. J. Virol. 96(3), e0183721 (2022).

He, X. et al. Generation of SARS-CoV-2 reporter replicon for high-throughput antiviral screening and testing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118(15), e2025866118 (2021).

Jin, Y. Y. et al. A convenient and biosafe replicon with accessory genes of SARS-CoV-2 and its potential application in antiviral drug discovery. Virologica Sinica 36(5), 913–923 (2021).

Adamantidis, A. & de Lecea, L. The hypocretins as sensors for metabolism and arousal. J. Physiol. -London 587(1), 33–40 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-vectored noninfectious replicon of SARS-CoV-2. Antiviral Res. 185, 104974 (2021).

Ke, N. et al. The xCELLigence system for real-time and label-free monitoring of cell viability. Methods Mol. Biol. 740, 33–43 (2011).

Gul, S. et al. Structure-based design and classifications of small molecules regulating the circadian rhythm period. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 18510 (2021).

Owen, C. D., Lukacik, P., Strain-Damerell, C. M., Douangamath, A., Powell, A. J., Fearon, D., Brandao-Neto, J., Crawshaw, A. D., Aragao, D., Williams, M., Flaig, R., Hall, D. R., McAuley, K. E., Mazzorana, M., Stuart, D. I., von Delft, F. & Walsh, M. A., COVID-19 main proteasewith unliganded active site (2019-nCoV, coronavirus disease 2019,SARS-CoV-2). CSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID, 6Y84, 3–7. (2020).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31(2), 455–461 (2010).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14(1), 33–8 (1996).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 14(1), 71–73 (2017).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26(16), 1781–1802 (2005).

Kim, S. et al. CHARMM-GUI ligand reader and modeler for CHARMM force field generation of small molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 38(21), 1879–1886 (2017).

Ma, C. L. et al. Boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 30(8), 678–692 (2020).

NCIRD. Types of COVID-19 Treatment. 2024 07/12/2024 [cited 2024 08/25/2024]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/treatment/index.html.

International Transporter, C., et al., Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., 9(3), 215–36, (2010).

Yabe, Y., Galetin, A. & Houston, J. B. Kinetic characterization of rat hepatic uptake of 16 actively transported drugs. Drug Metab. Dispos. 39(10), 1808–1814 (2011).

Chien, H. C. et al. Rapid method to determine intracellular drug concentrations in cellular uptake assays: Application to metformin in organic cation transporter 1-transfected human embryonic kidney 293 Cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44(3), 356–364 (2016).

Nakagawa, M. et al. Reduced intracellular drug accumulation in the absence of P-glycoprotein (mdr1) overexpression in mitoxantrone-resistant human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 52(22), 6175–6181 (1992).

Korzekwa, K. R. et al. Models to predict unbound intracellular drug concentrations in the presence of transporters. Drug Metab. Dispos. 40(5), 865–876 (2012).

Brown, H. S. et al. Comparative use of isolated hepatocytes and hepatic microsomes for cytochrome P450 inhibition studies: Transporter-enzyme interplay. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38(12), 2139–2146 (2010).

Shi, J. & Mitchison, T. J. Cell death response to anti-mitotic drug treatment in cell culture, mouse tumor model and the clinic. Endocrine-Related Cancer 24(9), T83 (2017).

Vatansever, E. C., et al., Bepridil is potent against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(10), (2021).

Fred, S. M. et al. Antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs reduce viral infection by SARS-CoV-2 and fluoxetine shows antiviral activity against the novel variants. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 755600 (2022).

Alkafaas, S. S., et al., Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of novel insight about the role of acid sphingomyelinase inhibitors in SARS- CoV-2 infectivity. Bmc Public Health, 24(1), (2024).

Sankaran, S. K. & Nair, A. S. Molecular dynamics and docking studies on potentially active natural phytochemicals for targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 41(14), 6459–6475 (2023).

Honrubia, J. M., et al., SARS-CoV-2-mediated lung edema and replication are diminished by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators. Mbio, 14(1), (2023).

Gruden, G., et al., Treatment with eltrombopag of severe immune thrombocytopenia and hemolytic anemia associated with COVID-19 pneumonia: A case report. Therapeutic Adv. Hematol., 12, (2021).

Maraziti, G. & Becattini, C. Eltrombopag for refractory vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. J. Thrombosis Thrombol. 53(4), 954–958 (2022).

Elkahloun, A. G. & Saavedra, J.M. Candesartan could ameliorate the COVID-19 cytokine storm. Biomed. Pharmacother., 131, (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Identify potent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors via accelerated free energy perturbation-based virtual screening of existing drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117(44), 27381–27387 (2020).

Ma, C. & Wang, J. Dipyridamole, chloroquine, montelukast sodium, candesartan, oxytetracycline, and atazanavir are not SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118(8), e2024420118 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a TUBITAK KBAG (221Z267) grant and Research Fund of Istanbul University (FYL-2023-40043). We thank Prof. Manicassamy Balaji (University of Iowa) for the generous gifts of ΔS Luc-GFP bacmid plasmids.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.O. performed in vitro and cell culture experiments, analyzed the data. H.Ş. performed all in silico calculations. I.C. and M.T. performed cell viability assays via xCelligence RTCA-DP real-time cell analysis system. C.A. conceptualized and performed in vitro enzymatic assays. M.C. and I.H.K conceptualized cell culture assays and edited manuscript. A.O. selected widely used and well tolerated drugs, edited manuscript. S.G. conceptualized all experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oruçoğlu, B., Çetin, İ., Şimşek, H. et al. Identification of potential SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors among well-tolerated drugs using drug repurposing and in vitro approaches. Sci Rep 15, 13975 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88388-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88388-4