Abstract

Cognitive impairment (CI) is a common complication in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), but its relationship with long-term glycemic control remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the associations between mean hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, HbA1c control status, HbA1c fluctuations, and CI in Chinese adults aged 45 years and older with T2DM using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). A total of 797 participants with HbA1c measurements from 2011 to 2015 and cognitive function assessments in 2018 were included. Logistic regression models and restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis were applied, adjusting for potential confounders. Higher mean HbA1c levels (≥ 9%) were significantly associated with an increased risk of CI, particularly in global cognition and episodic memory (OR 4.03 (1.45–11.20) for global cognition; OR 2.92 (1.02–8.38) for episodic memory). RCS analysis revealed a U-shaped relationship between mean HbA1c and CI, indicating that both excessively low and high HbA1c levels elevate CI risk. Uncontrolled HbA1c levels (≥ 8%) were also linked to higher CI risk compared to stable HbA1c levels. Maintaining HbA1c levels below 8% may significantly reduce CI risk in T2DM patients, highlighting the importance of personalized glycemic management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has reached epidemic proportions globally, affecting an estimated 463 million adults in 2019, and this number is projected to rise to 700 million by 20451. In China, the prevalence of diabetes has increased sharply to 12.8% among adults, making it one of the most pressing public health challenges in the country2. This rapid growth in diabetes prevalence has been accompanied by a surge in related complications, particularly cognitive impairment (CI), which has garnered substantial attention3. Individuals with T2DM face a significantly higher risk of developing mild CI and dementia compared to the general population4,5,6. A recent meta-analysis involving 17 studies and 4,380 elderly diabetic patients found that the incidence of CI in this population was 48% (95% confidence interval: 0.40–0.55)7. This heightened risk can have profound implications for patients’ quality of life and imposes an additional burden on healthcare systems. Thus, understanding the factors that contribute to CI in individuals with T2DM is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent or delay cognitive decline.

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), also known as glycated hemoglobin, is a standard indicator used to assess long-term blood glucose levels over a period of approximately three months8. Compared to fasting or random blood glucose levels, which are subject to daily fluctuations, HbA1c provides a more stable measure of overall glycemic status. It is widely used to monitor diabetes management, and assess the risk of diabetes-related complications8,9. Previous studies have shown that elevated HbA1c levels are associated with an increased risk of CI9. However, recent research suggests that both excessively high and low HbA1c levels may contribute to cognitive decline, indicating a potential U-shaped relationship between HbA1c and cognitive function9. Additionally, HbA1c fluctuations, defined as fluctuations in HbA1c levels over time, has emerged as a potential predictor of adverse health outcomes, including diabetes complications and CI10. Despite these findings, limited research has explored the impact of long-term average HbA1c levels and HbA1c fluctuations on cognitive function, particularly in non-Western populations.

With the rising prevalence of T2DM and its complications in China, there is an urgent need to clarify the role of long-term average HbA1c levels and HbA1c fluctuations in CI among Chinese adults. Most existing studies have focused on cross-sectional relationships or relied on HbA1c measurements from a single time point, limiting their ability to capture long-term glycemic patterns and dynamic changes in glucose control over time11,12. Moreover, research specifically targeting Chinese populations remains scarce, and few studies have examined the impact of both long-term average HbA1c and its fluctuations on cognitive outcomes.

To address these research gaps, we used data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative cohort that provides comprehensive information on demographics, health outcomes, and laboratory indicators. We investigated the association between mean HbA1c levels (measured in 2011 and 2015), HbA1c fluctuations (measured in 2011 and 2015), and CI (assessed in 2018) among T2DM patients aged 45 years and older using restricted cubic splines (RCS) and logistic regression models. Additionally, we used logistic regression models to evaluate the impact of HbA1c control status in 2015 on CI.

Results

Participants characteristics

The study population comprised 797 participants, including 514 with normal cognitive function and 283 with CI (Tables 1 and 2). The mean age was 58.56 ± 7.88 years, with the CI group being significantly older (61.07 ± 7.92 years) than those with normal cognition (57.18 ± 7.51 years, p < 0.001). Education levels also differed notably, with a higher proportion of individuals in the CI group classified as illiterate or having only completed primary school (90.46%) compared to the normal cognition group (50.78%, p < 0.001). While health behaviors such as smoking did not show significant differences between the groups, sleep patterns revealed notable disparities; individuals in the CI group reported poorer sleep duration (p < 0.01). Furthermore, CI was associated with higher prevalence rates of depression, arthritis, and other chronic diseases (Table 1).

Associations between mean HbA1c and cognitive impairment

CI may be influenced by factors such as physical activity, sleep, obesity, kidney disease, and cardiovascular conditions13,14. However, for diabetic patients, glycemic control and stability may have a greater impact on cognitive function (Table 2). To examine the effects of early long-term HbA1c levels, physical activity, and sleep on later cognitive function, we analyzed data from individuals who had HbA1c measurements in both 2011 and 2015 and underwent cognitive assessments in 2018. We calculated the mean HbA1c from 2011 to 2015 and used multivariate logistic regression models to evaluate its impact on CI in 2018, adjusting for physical activity, sleep, CVD, CKD, and depression (Table 3).

In the unadjusted (crude) model, mean HbA1c showed no significant effect on global cognition, episodic memory, and mental intactness (Table 3). However, in Adjusted Model 1, which controlled for age, sex, residence, education, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI, showed a positive association between global cognition and mean HbA1c in the group with mean HbA1c ≥ 9% (using 5.6% ≤ mean HbA1c < 6.5% as the reference; OR: 2.21 (1.15, 4.26), p = 0.02) (Table 3).

Adjusted Model 2, which additionally controlled for hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung disease, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, and CKD, demonstrated a significant positive association between mean HbA1c ≥ 9% and global cognition (2.49 (1.26, 4.91), p = 0.01) as well as episodic memory (2.18 (1.10, 4.29), p = 0.03), compared to the reference group (Table 3).

In Adjusted Model 3, which further included variables such as depression, sleep, and physical activity, individuals with mean HbA1c ≥ 9% showed a significantly higher risk of impairment in both global cognition (4.03 (1.45, 11.20), p = 0.01) and episodic memory (2.92 (1.02, 8.38), p = 0.049) compared to the reference group (Table 3; Fig. 1A and B). No significant associations were observed for lower mean HbA1c levels (< 5.6% or 6.5% ≤ mean HbA1c < 9%). In this model, higher education, being male, and living in urban areas were associated with a reduced risk of global CI. Conversely, sleeping less than 5 h per night was linked to a higher risk of impairment in episodic memory and mental intactness (Table 3; Fig. 1B, and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Association Between Mean HbA1c Levels and Cognitive Impairment in Global Cognition and Episodic Memory. Forest plots showing the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between mean HbA1c levels and cognitive impairment in (A) global cognition and (B) episodic memory. Analyses are based on Model 3, adjusted for baseline age, sex, residence, education, smoking, drinking, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung diseases, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, CKD, depression, sleep duration, and physical activity. HbA1c levels are categorized as < 5.6%, 6.5–6.9%, and ≥ 9%, with 5.6–6.4% as the reference category. The x-axis represents ORs, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

We know that excessively low glycemic control in diabetic patients can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and the relationship between HbA1c and CI may not be linear. Therefore, we employed an RCS analysis to investigate the non-linear relationship between mean HbA1c and CI.

Figure 2 demonstrates the relationship between mean HbA1c levels and the probability of CI across different cognitive domains under various adjustment models (Fig. 2A-L). In the crude model, the probability of CI increases linearly with rising HbA1c levels. However, after adjusting for age, sex, lifestyle factors, and comorbidities in Model 3, a U-shaped association emerges. The lowest risk of CI is observed at mean HbA1c levels around 6.15%, with the risk increasing significantly at both lower and higher mean HbA1c levels (Fig. 2D, H, and L). This U-shaped pattern is consistent across global cognition, episodic memory, and mental intactness, suggesting that both insufficient and excessive glycemic control are associated with higher CI risk.

Association between mean HbA1c levels and probability of cognitive impairment in different cognitive domains across models. Panels (A-D) show associations between mean HbA1c levels and probability of cognitive impairment in global cognition; (E-H) in episodic memory; and (I-L) in mental intactness. Models include: Crude Model (A,E,I); Model 1 (B,F,J), adjusted for age, sex, residence, education, smoking, drinking, and BMI; Model 2 (C,G,K), further adjusted for hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung diseases, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, and CKD; and Model 3 (D,H,L), additionally adjusted for depression, sleep, and physical activity. The green line indicates estimated probabilities of cognitive impairment, with 95% CIs shaded in light green. The median HbA1c of 6.15% is marked by the black dashed line. P-values for overall association and non-linearity are shown in each panel (p < 0.001 for non-linearity).

Based on the findings in Fig. 2, we stratified mean HbA1c levels into four quartiles and used Q2 as the reference group for multivariate logistic regression analysis (Supplementary Table 1). In Model 3, participants in both the lowest quartile (Q1) and the highest quartile (Q4) had a significantly higher risk of CI in global cognition compared to the reference group, with a 149% increase in Q1 and a 231% increase in Q4, further supporting the observed U-shaped association between mean HbA1c and CI (Fig. 3). However, no significant differences were observed between HbA1c quartiles in the mental intactness or episodic memory models, or in other models of global cognition, suggesting that the relationship between HbA1c levels and CI may vary across different cognitive domains (Supplementary Table 1).

Relationship between mean HbA1c quartiles and global cognitive impairment. Forest plot showing ORs and 95% CIs for the association between mean HbA1c levels and global cognitive impairment. The analysis is adjusted for baseline age, sex, residence, education level, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung diseases, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, CKD, depression, sleep duration, and physical activity. HbA1c levels are categorized into quartiles: Q1 (< 5.6), Q3 (6.5–6.9), and Q4 (≥ 9), with Q2 (5.6–6.4) as the reference. Significant associations (p < 0.05) are noted.

Associations between HbA1c average real variability and cognitive impairment

In addition to mean HbA1c levels, we examined whether HbA1c average real variability (ARV) was associated with CI. RCS analysis was used to explore the relationship between ARV and various cognitive function indicators. In the crude model, Model 1, and Model 2, ARV values ranging from negative to zero were associated with minimal changes in the risk of CI for both episodic memory and mental intactness (Fig. 4). However, for global cognition, the risk gradually decreased as ARV approached zero. In all models for mental intactness, when ARV values exceeded zero, the risk of CI increased proportionally with the rise in ARV. Furthermore, in Model 3, the probability of CI for episodic memory, mental intactness, and global cognition increased significantly as ARV rose above the lowest point, and the rate of increase was notably higher than the rate of decline observed in the ARV < 0 range (Fig. 4). Supplementary Fig. 2 further corroborates these findings, showing that for global cognition, the probability of CI decreases as ARV ranges from negative to zero, but once ARV exceeds zero, the risk steadily increases with higher ARV values. Quartile-based logistic regression analysis of ARV showed no statistically significant associations in any of the cognitive function models.

Association between HbA1c average real variability (ARV) index and probability of cognitive impairment in different cognitive domains across models. Panels (A-D) show associations between HbA1c ARV index and probability of cognitive impairment in global cognition; (E-H) in episodic memory; and (I-L) in mental intactness. The models are as defined in Fig. 2. Green lines indicate estimated probabilities of cognitive impairment, with 95% CIs shaded in light green. P-values for overall association and non-linearity are shown in each panel.

Associations between HbA1C control status and cognitive impairment

Previous studies have defined uncontrolled HbA1c as greater than 8%. In our analysis, individuals with an HbA1c level greater than 8% in 2015 were classified as “uncontrolled,” those with HbA1c levels > 6.5% in 2011 and < 6.5% in 2015 were classified as “controlled,” and individuals with HbA1c levels below 6.5% in both 2011 and 2015 were designated as the control group. We conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the association between HbA1c control status and CI15. We did not find significant differences between the various HbA1c control status groups in any of the models for episodic memory and mental intactness (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 5). However, in Model 3 for global cognition, the risk of CI in the uncontrolled group was significantly elevated (OR: 2.47 (1.15, 5.28); p = 0.02) (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 5). Additionally, while the uncontrolled group showed a significant association with CI in the other models, but the odds ratios remained high, with all OR values exceeding 1.

Association between HbA1c control status and global cognitive impairment. Forest plot displaying ORs and 95% CIs for the association between different HbA1c control status categories and global cognitive impairment. Categories include: “stable HbA1c” (HbA1c_2011 < 6.5% and HbA1c_2015 < 6.5%), “uncontrolled” (HbA1c_2015 ≥ 8.0%), “controlled” (HbA1c_2011 ≥ 6.5% and HbA1c_2015 < 6.5%), and “minimal change” (all other cases). Analyses are adjusted for baseline age, sex, residence, education level, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung diseases, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, CKD, depression, sleep duration, and physical activity, with p-values < 0.05 considered significant. The reference group includes participants with stable HbA1c levels (< 6.5% in both 2011 and 2015).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the associations between mean HbA1c levels, HbA1c control status, HbA1c fluctuations, and CI among Chinese adults aged 45 years and older using data from the CHARLS. Our findings indicate that higher long-term mean HbA1c levels are significantly associated with an increased risk of CI, particularly in global cognition and episodic memory. Notably, we identified a U-shaped relationship between mean HbA1c levels and CI, indicating that both excessively low and high HbA1c levels may be detrimental to cognitive function. A similar U-shaped association was found between HbA1c ARV and CI; however, the changes were not as significant, suggesting that large fluctuations in HbA1c levels may still contribute to CI Additionally, we found that uncontrolled HbA1c levels (≥ 8%) were associated with an elevated risk of CI.

Higher mean value of HbA1c (≥ 9%) was associated with CI in T2DM patients. Huang’s cross-sectional research demonstrated that each 1% rise in HbA1c levels was significantly associated with a 0.21-point decline in Mini Mental State Examination scores and a 0.11-point reduction in Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores11. A study use data from the UK Biobank, they found patients with both a longer diabetes duration (≥ 10 years) and poor glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 8%) exhibited the highest risk of all-cause dementia, with a 107% increased risk compared to those with a shorter diabetes duration (< 10 years) and better glycemic control (HbA1c < 8%)16. Apart from CI, chronic hyperglycemia can also increase the risk of series diseases (like atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetic nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy)17,18. Therefore, achieving optimal glycemic control is a crucial strategy for minimizing these chronic complications. The American Diabetes Association recommends maintaining HbA1c levels below 7% in nonpregnant adults without apparent risk of hypoglycemic19.

Our study further demonstrated that increased HbA1c fluctuations may be associated with a higher risk of CI in patients with T2DM aged 45 years and older, which is consistent with findings from previous studies. A large-scale study conducted in the United States, involving over 170,000 individuals with T2DM, found that those in the second to fifth quintiles of HbA1c fluctuations, measured by either SD or coefficient of variation (CV), had a 20–50% higher risk of developing dementia compared to those in the lowest quintile of HbA1c fluctuations20. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 577,592 diabetic patients reported that each unit increase in HbA1c fluctuations, as indicated by CV and SD, was associated with a 6% and 19% increased risk of dementia, respectively10. HbA1c fluctuations may contribute to CI through biological mechanisms involving glycemic variability, which induces oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction21,22. These processes impair the cerebral microvasculature, leading to neuronal damage and cognitive decline. Additionally, hypoglycemic episodes associated with glycemic variability can exacerbate brain injury through glucose deprivation23,24,25. These mechanisms are supported by research linking HbA1c variability to an increased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications, including dementia, as well as lower hippocampal volume in both diabetic and non-diabetic populations26,27. Further evidence highlights the potential risks of substantial changes in glycemic control. For example, Lee et al. reported that a reduction in HbA1c of more than 10% within one year was associated with an elevated risk of dementia in T2DM patients aged 65 years and older28. Similarly, Turnbull et al. demonstrated that intensive glucose-lowering therapy increased the incidence of severe hypoglycemia and mortality29. These findings, along with our observed U-shaped relationship between mean HbA1c levels, ARV, and CI, underscore the need for personalized glycemic management. Our results indicate that both the lowest and highest quartiles of mean HbA1c were associated with an increased risk of CI, highlighting that maintaining stable HbA1c levels is crucial for reducing the risk of adverse cognitive outcomes in diabetic populations.

Consistent with previous studies16,30, we also found that poor HbA1c control was associated with an increased risk of CI. Specifically, individuals with HbA1c levels above 8% in 2015 (the “uncontrolled” group) had a significantly higher risk of CI in global cognition compared to those with stable HbA1c levels. In contrast, there was no significant difference in cognitive function between individuals in the HbA1c controlled group and those in the stable HbA1c group. These findings support the idea that inadequate HbA1c control such as sustained hyperglycemia or consistently elevated HbA1c levels (≥ 8%) can accelerate CI, likely due to chronic exposure to elevated glucose levels, increased oxidative stress, and vascular damage3,31.

Here we found less education, female, living in rural, aging, arthritis, and sleep below 5 h are risk factors for CI occur, these are consistent with previous studies32,33,34,35. In addition to these protentional risk factors, CI can also be influenced by various modifiable risk factors that include hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, social isolation, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury and air pollution33. Prevention strategies should focus on improving education in early life, managing hypertension and diabetes, promoting physical and social activities, and addressing hearing loss in mid-life. Additionally, reducing exposure to air pollution, avoiding smoking and alcohol misuse, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle are crucial. Interventions targeting these risk factors could theoretically prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases globally33.

Beyond their independent effects, factors such as education, sex, and sleep time may interact with glycemic control mechanisms to further influence cognitive outcomes36,37,38,39. Lower education levels and poor sleep quality are associated with impaired glycemic control40,41,42,43. For example, insufficient sleep and sleep fragmentation can reduce insulin sensitivity by 20–30%, disrupt glucose metabolism, and increase the risk of diabetes43. Similarly, individuals with higher educational attainment and better health literacy are more likely to achieve good glycemic control due to improved understanding of health education and instructions40. However, this relationship may be confounded by socioeconomic factors such as household income and educational background. Sex-related hormonal differences also play a role in the interplay between glycemic control and CI. Testosterone levels are significantly lower in men with T2DM and higher in women with T2DM compared to controls. Prospective studies indicate that higher testosterone levels reduce T2DM risk in men but may increase diabetes risk in women44. These hormonal variations can modulate HbA1c levels and their downstream effects on cognitive outcomes. In summary, lower education, poor sleep quality, and sex-related hormonal differences may not only act as independent risk factors for CI but also interact with glycemic control mechanisms. For instance, reduced health literacy and poor sleep patterns can worsen glycemic control, while hormonal variations could modulate HbA1c levels and their impact on cognition.

Our study has several limitations. First, our strict inclusion criteria prevented us from further stratifying the total population by age, particularly the old adults (< 60 years: 445; ≥60 years: 352), (< 60 years: 445 individuals; ≥60 years: 352 individuals), despite aging being a known risk factor for CI. Second, the unexpected lack of association between hypertension, smoking, drinking and CI in our study may be partly attributable to sample size limitations. Third, the absence of HbA1c measurements between 2015 and 2018 limits our ability to fully capture glycemic control dynamics during this period, which may affect the generalizability of our findings, particularly for individuals with substantial changes in glycemic control post-2015. Fourth, although previous studies have suggested that disease duration may contribute to CI risk, we were unable to examine this factor due to CHARLS design. Fifth, the MMSE and TICS, while reliable tools for assessing global cognitive function, may have limited sensitivity in detecting early-stage cognitive decline, particularly in individuals with T2DM who often exhibit subtle deficits in executive function and attention45. Future research could benefit from incorporating more sensitive tools, such as the Diabetes-Specific Dementia Risk Score (DSDRS), to better capture early cognitive changes in this population45,46,47,48. Additionally, not all participants reported their sleep patterns or some other covariates. A complete case analysis was performed, and consistent results across models suggest that missing data did not significantly influence the observed relationship between HbA1c levels and cognitive impairment. Nonetheless, a major strength of our study is its large, population-based sample with long-term follow-up in China. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between HbA1c fluctuations and CI among middle-aged and elderly diabetic patients in Chinese population. Moreover, stringent quality control and quality assurance measures were implemented at every stage of the CHARLS, ensuring the high quality and reliability of our findings.

In conclusion, our prospective cohort study demonstrated that both low and high HbA1c levels, as well as large HbA1c fluctuations, are associated with an increased risk of CI in patients with T2DM. Our findings suggest that maintaining stable glycemic control, with a HbA1c consistently under 8%, may significantly reduce the risk of CI in patients with T2DM.

Methods

Study population

This study used data from the CHARLS, an ongoing national survey that began in 2011 with a baseline sample of 17,708 participants. CHARLS covers 450 urban and rural communities across 28 provinces in China and collects comprehensive information on demographics, health outcomes, family structure, and laboratory indicators, including blood samples49. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. For this analysis, data from three waves of CHARLS—2011 (baseline), 2015, and 2018—were included.

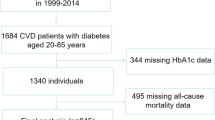

We started with 19,744 individuals who had dementia scores from the 2018 wave. 13,420 participants had HbA1c data from 2015, and 11,847 had HbA1c data from 2011. Among them, 6,930 participants had HbA1c measurements in both 2011 and 2015, along with dementia scores in 2018. We further restricted the sample to those aged 45 years and older and the dementia scores values, excluding 133 individuals under 45, 1336 individuals are missing detailed scoring values. resulting in 5461 participants. After removing 4,664 participants with missing diabetes data or without T2DM, a final sample of 797 individuals remained (Supplement Fig. 3).

Assessment of cognitive function

Cognitive function was assessed in 2018 using the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which includes two key dimensions: episodic memory and mental intactness. Episodic memory was evaluated through immediate and delayed recall tasks. Participants were asked to recall 10 Chinese words immediately after presentation (immediate recall) and again after a 5-minute interval (delayed recall), with each correct recall scored as one point, resulting in a total episodic memory score ranging from 0 to 20.

Mental intactness was assessed using the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS) and a visuospatial ability task. The TICS included items such as identifying the current date (year, month, day), current season, day of the week, and performing serial subtractions of 7 from 100 (up to five times). Visuospatial ability was evaluated by asking participants to replicate a figure shown by the interviewer. Correct responses were scored as 1, while incorrect responses received a score of 0. The total mental intactness score ranged from 0 to 11. Global cognition scores were calculated by summing the episodic memory and mental intactness scores, with a possible range of 0 to 31, where higher scores indicate better cognitive function50.

CI was defined as a global cognition score of less than 1151,52,53. Additionally, participants with scores in the lowest quartile for either mental intactness (< 2.75) or episodic memory (< 5) were also classified as CI51.

The MMSE and TICS were chosen for their reliability and validity in assessing cognitive impairment, particularly in large-scale epidemiological studies. The MMSE offers a comprehensive evaluation of cognitive domains, while the TICS is suitable for non-face-to-face assessments. Both tools have been widely applied in research on T2DM populations, ensuring their relevance to the study context54.

HbA1c-related indicators

Since HbA1c offers a more accurate reflection of average blood glucose levels over the past three months compared to random blood glucose measurements, we used the mean HbA1c levels from 2011 to 2015 to evaluate blood glucose control over the three-year period.

HbA1c fluctuations were defined as fluctuations in HbA1c values between 2011 and 2015. We assessed these fluctuations using three metrics: (1) Fluctuations Independent of the Mean (VIM), (2) Average Real variability (ARV), and (3) Standard Deviation (SD) of HbA1c changes between baseline and follow-up visits. ARV, which represents the average absolute difference between consecutive values, was calculated as ARV = HbA1c_2015 - HbA1c_2011. VIM was determined using the formula: VIM = abs (ARV) / mean HbA1c. The SD was calculated using the formula:

Given that the standard for blood glucose control in diabetic patients is an HbA1c level below 6.5% and a random blood glucose level of 11.1 mmol/L corresponds to an HbA1c of approximately 9%, we established the following categories based on mean HbA1c levels: <5.6%, 5.6–6.5%, 6.5–9%, and ≥ 9%.

HbA1c thresholds of 6.5% and 8.0% were used to classify controlled and uncontrolled HbA1c levels, respectively30. Accordingly, we defined the following HbA1c control status categories: stable HbA1c (HbA1c_2011 < 6.5% and HbA1c_2015 < 6.5%), uncontrolled (HbA1c_2015 ≥ 8.0%), controlled (HbA1c_2011 ≥ 6.5% and HbA1c_2015 < 6.5%), and minimal change (all other cases).

Covariates

In this study, we collected baseline data from 2011 on various covariates, including demographic information such as age, education, and residence (rural or urban). Due to the small number of individuals with only primary or college education in the CI group, we combined education levels into two categories: ‘illiterate or primary school’ and ‘middle school or above.’

Health behaviors were assessed, including smoking status (no/yes), drinking status (no/yes), and physical activity levels, which were classified as none, mild, moderate, or vigorous. Physical activity values were defined based on individuals’ weekly engagement in various activities. If any activity variable (mild, moderate, or vigorous) was missing, the physical activity value was set to NA. It was classified as “mild” if only mild activity was reported, “Moderate” for only moderate activity, “Vigorous” for vigorous activity, and “None” if no activities were reported.

We collected health conditions, including hypertension, cancer, chronic lung diseases, heart disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease (CKD), arthritis, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (CVD)—which encompasses stroke, angina, heart attack, heart failure, coronary heart disease, or other heart problems. Depression was assessed using the CESD10, with a total score greater than 10 indicating the presence of depressive symptoms. Medication use for lipid-lowering drugs was also recorded. Sleep patterns were categorized as less than 5 h, 5 to 7 h, 7 to 9 h, and more than 9 h each night. Laboratory measurements included C-reactive protein (CRP), glucose, creatinine, cystatin C, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), uric acid (UA), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides (TG), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median ± interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and as counts (percentages) for categorical variables. Differences between the CI group and the normal cognition group were assessed using the Student’s t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or χ2 test, as appropriate.

Mean HbA1c levels and HbA1c control status were categorized into four groups based on HbA1c control in 2011 and 2015 and included as categorical variables in the models. Logistic regression analysis was then used to evaluate the association between mean HbA1c levels and CI. Three multivariable models were constructed to account for potential confounders. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, residence, education, smoking status, drinking status, and BMI. Model 2 included additional adjustments for hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung diseases, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, and CKD. Model 3 further adjusted for depression, sleep, and physical activity.

A Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) model was employed to investigate the non-linear relationship between mean HbA1c and CI. Covariates included in the RCS models were age, sex, residence, education, smoking status, drinking status, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lung diseases, CVD, lipid-lowering drugs, arthritis, CKD, depression, sleep, and physical activity. Non-linearity was evaluated using a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.0). All tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). The dataset can be accessed and downloaded from the official CHARLS website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn) upon completion of the registration and application process. The dataset generated during this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Saeedi, P. et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107843 (2019).

Mao, W., Yip, C. W. & Chen, W. Complications of diabetes in China: Health system and economic implications. BMC Public Health 19, 269 (2019).

McCrimmon, R. J., Ryan, C. M. & Frier, B. M. Diabetes and cognitive dysfunction. Lancet 379, 2291–2299 (2012).

Biessels, G. J. & Despa, F. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes mellitus: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 591–604 (2018).

Reijmer, Y. D., van den Berg, E., Ruis, C., Kappelle, L. J. & Biessels, G. J. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 26, 507–519 (2010).

van den Berg, E., de Craen, A. J., Biessels, G. J., Gussekloo, J. & Westendorp, R. G. The impact of diabetes mellitus on cognitive decline in the oldest of the old: A prospective population-based study. Diabetologia 49, 2015–2023 (2006).

Chen, J. F., Zhang, Y. P., Han, J. X., Wang, Y. D. & Fu, G. F. Systematic evaluation of the prevalence of cognitive impairment in elderly patients with diabetes in China. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 225, 107557 (2023).

Welsh, K. J., Kirkman, M. S. & Sacks, D. B. Role of glycated proteins in the diagnosis and management of diabetes: Research gaps and future directions. Diabetes Care 39, 1299–1306 (2016).

Zheng, F., Yan, L., Yang, Z., Zhong, B. & Xie, W. HbA(1c), diabetes and cognitive decline: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Diabetologia 61, 839–848 (2018).

Song, J., Bai, H., Xu, H., Xing, Y. & Chen, S. HbA1c variability and the risk of dementia in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 7706330 (2022).

Huang, L., Yang, L., Shen, X. & Yan, S. Relationship between glycated hemoglobin A1c and cognitive function in nondemented elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Metab. Brain Dis. 31, 347–353 (2016).

Gao, Y. et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment with type 2 diabetes mellitus among elderly people in China: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 62, 138–142 (2016).

Etgen, T. et al. Physical activity and incident cognitive impairment in elderly persons: The INVADE study. Arch. Intern. Med. 170, 186–193 (2010).

Tsapanou, A. et al. Sleep problems as predictors of cognitive decline in essential tremor: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Sleep Med. 116, 13–18 (2024).

Bender, R. Introduction to the use of regression models in epidemiology. Methods Mol. Biol. 471, 179–195 (2009).

Li, F. R. et al. Influence of diabetes duration and glycemic control on dementia: A cohort study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 2062–2070 (2021).

Kunutsor, S. K. et al. Glycaemic control and macrovascular and microvascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials investigating intensive glucose-lowering strategies in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 2069–2081 (2024).

Kranenburg, G. et al. The relation between HbA1c and cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without vascular disease. Diabetes Care 38, 1930–1936 (2015).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. 6. Glycemic targets: Standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46, S97–S110 (2023).

Moran, C. et al. HbA(1c) variability associated with dementia risk in people with type 2 diabetes. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 5561–5569 (2024).

Monnier, L., Colette, C. & Owens, D. R. Glycemic variability: The third component of the dysglycemia in diabetes. Is it important? How to measure it? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2, 1094–1100 (2008).

Scott, E. S. et al., Long-term glycemic variability and vascular complications in type 2 diabetes: Post hoc analysis of the FIELD study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, e3638-e3649 (2020).

Cameron, N. E., Eaton, S. E., Cotter, M. A. & Tesfaye, S. Vascular factors and metabolic interactions in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia 44, 1973–1988 (2001).

Rehni, A. K., Cho, S. & Dave, K. R. Ischemic brain injury in diabetes and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Neurochem. Int. 152, 105219 (2022).

Whitmer, R. A., Karter, A. J., Yaffe, K., Quesenberry, C. P. Jr. & Selby, J. V. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 301, 1565–1572 (2009).

Jang, J. Y., Moon, S., Cho, S., Cho, K. H. & Oh, C. M. Visit-to-visit HbA1c and glucose variability and the risks of macrovascular and microvascular events in the general population. Sci. Rep. 9, 1374 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Visit-to-visit HbA1c variability, dementia, and hippocampal atrophy among adults without diabetes. Exp. Gerontol. 178, 112225 (2023).

Lee, A. T. C. et al. Higher dementia incidence in older adults with type 2 diabetes and large reduction in HbA1c. Age Ageing 48, 838–844 (2019).

Control, G. et al. Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 52, 2288–2298 (2009).

Sheng, C. S. et al. Prognostic significance of long-term HbA(1c) variability for all-cause mortality in the ACCORD Trial. Diabetes Care 43, 1185–1190 (2020).

Little, K. et al. Common pathways in dementia and diabetic retinopathy: Understanding the mechanisms of diabetes-related cognitive decline. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 50–71 (2022).

Kong, J., Zhou, L., Li, X. & Ren, Q. Sleep disorders affect cognitive function in adults: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 21, 133–142 (2023).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 404, 572–628 (2024).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396, 413–446 (2020).

Petersen, L. E. et al. Cognitive impairment in rheumatoid arthritis: Role of lymphocyte subsets, cytokines and neurotrophic factors. Clin. Rheumatol. 37, 1171–1181 (2018).

Kronholm, E. et al. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive functioning in the general population. J. Sleep Res. 18, 436–446 (2009).

Millan-Calenti, J. C. et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: Effects of level of education, age, sex and associated factors. Dement. Geriatr. Cognit. Disord 28, 455–460 (2009).

Benito-Leon, J., Bermejo-Pareja, F., Vega, S. & Louis, E. D. Total daily sleep duration and the risk of dementia: A prospective population-based study. Eur. J. Neurol. 16, 990–997 (2009).

Ferrie, J. E. et al. Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: Findings from the Whitehall II study. Sleep 34, 565–573 (2011).

Chen, G. D., Huang, C. N., Yang, Y. S. & Lew-Ting, C. Y. Patient perception of understanding health education and instructions has moderating effect on glycemic control. BMC Public Health 14, 683 (2014).

Reynolds, D. B., Walker, R. J., Campbell, J. A. & Egede, L. E. Differential effect of race, education, gender, and language discrimination on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 17, 243–247 (2015).

Tsereteli, N. et al. Impact of insufficient sleep on dysregulated blood glucose control under standardised meal conditions. Diabetologia 65, 356–365 (2022).

Reutrakul, S. et al. Impact of sleep and circadian disturbances on glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes. In Diabetes in America (eds. Cowie, C. C. et al.) (Bethesda (MD) of interest. Dr. Reutrakul received speaker honoraria from Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, and Medtronic, and is the recipient of investigator-initiated grant support from Merck. Dr. Punjabi has received research grant support from Philips Respironics and ResMed that is unrelated to the current work. Dr. Van Cauter has served as a consultant for Shire, Philips Respironics, Pfizer, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and is the recipient of investigator-initiated grant support from Shire, Merck, and AstraZeneca, 2018).

Ding, E. L., Song, Y., Malik, V. S. & Liu, S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 295, 1288–1299 (2006).

Ciudin, A. & Simo, R. New methods for the diagnosis and monitoring of cognitive function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1024794 (2022).

Exalto, L. G. et al. Risk score for prediction of 10 year dementia risk in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 1, 183–190 (2013).

Bello-Chavolla, O. Y., Aguilar-Salinas, C. A. & Avila-Funes, J. A. The type 2 diabetes-specific dementia risk score (DSDRS) is associated with frailty, cognitive and functional status amongst Mexican community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 20, 363 (2020).

Ciudin, A. et al. Retinal microperimetry: A new tool for identifying patients with type 2 diabetes at risk for developing Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 66, 3098–3104 (2017).

Zhao, Y. H. et al. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, 2011–2012 National Baseline Users’ Guide, National School of Development (Peking University, Berlin, 2013).

Liu, M. et al. The mediating role of cognition in the relationship between sleep duration and instrumental activities of daily living disability among middle-aged and older Chinese. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 94, 104369 (2021).

Luo, L. et al. Greater variability in HDL-C was associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline in the middle- and elderly Chinese: A cohort study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 125, 105503 (2024).

Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., Langa, K. M. & Weir, D. R. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the aging, demographics, and memory study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 66(Suppl 1), i162-171 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Long-term increase in cholesterol is associated with better cognitive function: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 691423 (2021).

Dong, Y., Kua, Z. J., Khoo, E. Y., Koo, E. H. & Merchant, R. A. The utility of brief cognitive tests for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 17, 889–895 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research utilizes data obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). We acknowledge the efforts of the CHARLS research and field teams for designing and executing the surveys, as well as all the study participants for their valuable contributions. We would also thanks to Zhang Jing (Shanghai Tongren Hospital) for his work on the CHARLS database. His outstanding work, nhanesR package and webpage, makes it easier for us to explore CHARLS database.

Funding

This research was supported by Clinical Research “Climbing” Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Grant No. YYZS2023005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X. and X.H. wrote the main manuscript text and Y.X. prepared figures and tables, X.h. checked the data, figures and tables. R.N. contributed equally to data curation and reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.M. acquired funding, supervised the project, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Y., Hong, X., Neelagar, R. et al. Association between glycated hemoglobin A1c levels, control status, and cognitive function in type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 5011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89374-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89374-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence and impact of microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus on cognitive impairment and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)