Abstract

Seven compounds were isolated from ethyl acetate extract of Alcea rosea and were examined for their cytotoxicity against HCT116, HT29 and SW480 colon cancer cells. It was found that two compounds (C4 and C5) exhibited strong anti-colon cancer activities. These two compounds were used to study their properties that include MTT activity (with IC50 of C4 as 74.71, 129.0 and 131.4 µg/ml in HCT116, HT29 and SW480 respectively, whereas IC50 of C5 as 128.1, 168.4 and 225.8 µg/ml in HCT116, HT29 and SW480 cells respectively), colony formation activity, wound healing activity, spheroid formation activity, DAPI-PI staining, acridine-orange and ethidium bromide staining, ROS measurement, and rhodamine-123 staining in both HCT116 and HT29 colon cancer cells. Both the compounds showed significant increase in apoptosis as visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol/propidium iodide (DAPI-PI) and acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EtBr) staining. The induction of apoptosis was further confirmed by the expressions of cleaved PARP and caspase 3. ROS generation and its effect on MMP were measured by staining cells with Dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and Rhodamine. Expression levels of EMT associated markers like Cyclin D1, Slug, Vimentin, and E-Cadherin were also studied. Both the compounds down regulate protein levels of Slug, Cyclin D1, and Vimentin in a concentration-dependent manner. Eeffect of C4 and C5 compounds on key signaling protein like Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh were evaluated. Additionally, mRNA levels of these genes were also analyzed. C4 exhibited the best binding affinity when docked with Shh and Wnt3a and Notch1. Similarly, C5 exhibited − 8.8, -8.2 and − 7.6 kcal⋅mol− 1 with Shh, Wnt3a and Notch1. The present findings provide insight and immense scientific support and integrity to a piece of indigenous knowledge. However, validation in living organisms is necessary before progressing to clinical trials and advancing it into a marketable pharmaceutical product.

Similar content being viewed by others

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has complex molecular and clinical features. The most prevalent variant of CRC, making up around 95% of cases, is adenocarcinoma1. It develops from the glandular cells that line the colon or rectum. This disease is impacted by both hereditary and environmental factors. Understanding the genes involved in CRC is crucial for unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis, which may be crucial for developing targeted therapies. The wnt/β-Catenin pathway is reported to be involved in the initiation, progression, and metastasis of CRC. Aberrant upregulation of this pathway through genetic alterations leads to transcriptional activation of downstream target genes involved in proliferation, survival, as well as buildup of β-catenin levels in cells. On the other hand, the NOTCH pathway is important in the progress and evolution of CRC. NOTCH signaling controls a large number of biochemical activities viz., cell fate determination, proliferation, and differentiation. The signaling mechanism is highly conserved and is concerned with cell-to-cell communication and tissue development. It is triggered by exchange of NOTCH receptors (NOTCH1-4) on neighboring cells with ligands (DLL1-4 and JAGGED1/2)2. The Hedgehog (Hh)/GLI pathway has become known as a major character in CRC initiation and progression. The Hh/GLI pathway modulates an array of biological activities e.g., cell differentiation, cell growth as well as tissue patterning. The Hh/GLI signaling mechanism is vital in tissue homeostasis and embryonic development. It is induced by the attaching of Hedgehog ligands (Desert Hh, Indian Hh, and Sonic Hh) to the PTCH (Patched) receptor3. The Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways are integral to CRC progression, driving proliferation, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Targeting these pathways holds therapeutic promise in mitigating CRC progression1,4,5.

Surgery and chemotherapeutic interventions are the most commonly used methods for the treatment of colon cancer. However, the development and identification of plant derived compounds which are capable of killing or inhibiting transformed cells promoting carcinogenesis without inducing toxic effects or being toxic to the normal cells are of utmost significance6. Thus, supplements derived from plants are receiving due recognition as the most potent approach to lessen the burden of colorectal cancer-associated mortality7.

Phytochemicals are comprehensively being explored globally for their potential health benefits, including their role in the treatment of CRC. They possess diverse properties that can contribute to the prevention and treatment of CRC8. Alcea rosea L. belongs to the Malvaceae family and is used to treat renal and uterine inflammation, gastrointestinal infections with diarrhea and vomiting, renal and urethra infections, hepatitis, malaria, arthritis, and snake bites in folk medicine9. The plant has a variety of biological functions which include anticancer10, antiurolithiatic, diuretic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective9, analgesic and antibacterial activities11,12. Alcea rosea was selected due to its historical medicinal use and rich composition of bioactive compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which are essential in countering CRC progression10,13. In the present study anti colorectal cancer potential of Alcea rosea was investigated. Chromatographic and spectroscopic methods were used of identify bioactive compounds of the experimental plants. Molecular mechanism and signaling pathways involved in anti-CRC effect of the isolated metabolites were also investigated.

Results

MTT assay

For checking the cytotoxicity of isolated compounds on CRC cells, MTT assay was performed. Briefly cells were treated with designated concentrations (50–600 µg/ml) for a period of 48 h. As shown in (Fig. 1) compounds C4 and C5 led to a significant decrease in cell viability. Upon determination of IC50 values of C4 and C5 in CRC cells using nonlinear regression method in GraphPad prism, C4 exhibited an IC50 value of 74.71, 129.0 and 131.4 µg/ml in HCT116 (Fig. 1A), HT29 (Fig. 1C) and SW480 (Fig. 1E) cells respectively, whereas C5 exhibited an IC50 value of 128.1, 168.4 and 225.8 µg/ml in HCT116 (Fig. 1B), HT29 (Fig. 1D) and SW480 (Fig. 1F) cells respectively. while other compounds (C1, C2, C3, C6 and C7) showed non-significant inhibition response on cell viability in HCT116, HT29 and SW480 cells. In terms of sensitivity towards the C4 and C5, HCT116 cells were more sensitive to C4 and C5 treatment followed by HT29 and SW480 cells respectively. These results demonstrate that C4 and C5 exhibit a strong anticancer potential across the CRC cell lines tested. However, the sensitivity may vary.

MTT assay of compounds C4 and C5 on HCT116 (A, B), HT29 (C, D) and SW480 (E, F) cell lines for a period of 48 h. Among all the three colorectal cancer cell lines C4 showed the maximum percentage inhibition on HCT116 with Ic50 of 74.71 µg/ml and least inhibition was observed in case of compound C5 on SW480 cells with IC50 of 225.8 µg/ml. The results were determined using nonlinear regression method in GraphPad prism, version 10.1.0 (316).

C4 and C5 induce apoptosis in CRC cell lines

To evaluate the apoptotic nature of these potential isolates in CRC cell lines. we treated HCT116 cells with 50 µg/ml of C4 and 110 µg/ml of C5 respectively, whereas HT29 cells were treated with 110 µg/ml of C4 and 150 µg/ml of C5 respectively for 24 h. A significant increase in apoptosis was observed as visualized by DAPI-PI (Fig. 2) and AO-EtBr staining (Fig. 3). In terms of sensitivity, C4 exhibited more apoptotic capability than C5 in both HCT116 and HT29 cells. This induction of apoptosis by C4 and C5 in HCT116 and HT29 cell lines was further confirmed by the extent of cleaved PARP (Fig. 4A, B) and cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 4C, D). Administration of C4 to HCT116 cells and HT29 cells led to 3.7 and 3.6 fold increase in cleaved PARP (Fig. 4A, B) and 2.5 and 3.1 fold increase in cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 4C, D), respectively. Similar trend was observed for C5, 3.1 and 2.9 fold increase in cleaved PARP (Fig. 4A, B) and 2.3 and 2.6 fold increases in cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 4C, D), respectively. Suggesting both the compounds viz. C4 and C5 promoted significant increase in apoptotic cell population upon administration. A strong correlation was observed between the reduction in Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh levels and the inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis, with C4 demonstrating greater efficacy. This supports the hypothesis that the magnitude of pathway inhibition by C4 and C5 underpins their differential anticancer effects.

HCT116 and HT29 cells were incuded to undego apoptosis via compounds C4 and C5. HCT116 and HT29 cells were cultured in the presence of 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) for a duration of 24 h. After 24 h of incubation, we treated the cells with various concentrations viz. 50 µg/ml of C4 and 110 µg/ml of C5 respectively in HCT116 cells, whereas HT29 cells were treated with 110 µg/ml of C4 and 150 µg/ml of C5 respectively. The cells were observed under Olympus IX53 imaging microscope after being stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)(1 µg/ml) at 24 h after treatment. The analysis revealed a marked escalation in both the quantity and dimension of apoptotic features in cells treated with C4 and C5 in comparison to the control group.

C4 and C5 compounds induce apoptosis in HCT116 and HT29 cell lines (AO/EtBr). Dual staining of the HCT116 and HT29 cells showing cells in early and late apoptotic stage. A significant increase in apoptosis was observed as visualized by AO-EtBr staining. In terms of sensitivity, C4 exhibited more apoptotic capability than C5 in both HCT116 and HT29 cells.

Effect of C4 and C5 on ROS and MMP of CRC cell lines

ROS generation and its effect on MMP were measured by staining cells with DCFH-DA and Rhodamine-123 (Rh-123) respectively (Fig. 5). An increase in ROS generation by 1.88 and 1.89-fold was observed in HCT116 and HT29 cell lines by C4, respectively (Fig. 5 A). Similarly, C5 showed 1.72 and 1.70 fold increase in ROS generation in HCT116 and HT29 (Fig. 5A). C4 and C5 induced decrement in MMP in HCT116 (2.1 and 1.9 folds, respectively) and HT29 cells (3.2 and 2.3 folds, respectively) was also observed (Fig. 5B). The specificity of apoptosis induction by C4 and C5 was confirmed through DMSO controls, indicating that ROS-mediated apoptosis was directly attributable to the compounds rather than nonspecific cellular stress.

C4 and C5 compounds induce intracellular ROS production in HCT16 and HT29 cells. (A) HCT116 and HT29 cells were cultured for a periodof 24 h in a medium enriched with 10% FBS. At 24 h, cells were treated with various concentrations viz. 50 µg/ml of C4 and 110 µg/ml of C5 respectively in HCT116 cells, whereas HT29 cells were treated with 110 µg/ml of C4 and 150 µg/ml of C5 respectively. At 24 h cells were stained with DCFH-DA and visualise uner Yokogawa CQ1 Confocal Imaging Cytometer to determine the ROS levels. The quantification of green signals was performed with the Image-J software. Using the mean of three investigations, fluorescent data were normalized with the positive control. (B) After treatment with C4 and C5 with varying concentrations (50 µg/ml of C4 and 110 µg/ml of C5 respectively in HCT116 cells, whereas HT29 cells were treated with 110 µg/ml of C4 and 150 µg/ml of C5 respectively) disrupts mitochondrial membrane permeability (MMP) for an additional 24 h.

Effect of C4 and C5 on Colony, spheroid formation and cell migration in CRC cell lines.

C4 and C5 exhibited a significant reduction in colony forming potential of CRC cells (Fig. 6). C4 reduced the colony formation to 80.18% and 72.22% in HCT116 and HT29 cells, respectively, as compared to untreated cells. Reduction was found to be 66.06% and 55.56%, respectively on treating the cells with C5. Concomitant with these findings, decreased spheroid forming potential in HCT116 and HT29 cells upon treatment with C4 and C5 was also observed (Fig. 7). The effect of C4 and C5 on the wound healing potential was also investigated (Fig. 8). Post 48 h of treatment with C4, more than 92% reduction in cell migration of both colon cancer cell lines was observed as compared to untreated cells. Similarly, post 48 h of treatment with C5, 84.74% (HCT116 cells) and 77.26% (HT29) reduction in cell migration. Thus, C4 exhibited more potent anti-wound healing potential as compared to compound C5.

(A) Colony formation assay was performed on proliferating HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with 50 µg/ml of C4 and 110 µg/ml of C5, whereas HT29 cells were treated with 110 µg/ml of C4 and 150 µg/ml of C5 respectively. The treatment of CRC cells with C4 and C5 exhibited significant reduction in colony forming potential of CRC cells. Whereas the treatment of HCT116 and HT29 with C4 led to 80.18% and 72.22% reduction respectively in percentage of colonies as compared to untreated cells. While treatment of HCT116 and HT29 with C5 led to 66.06% and 55.56% reduction respectively in percentage of colonies as compared to untreated cells. (B) Values are expressed as ± SD, *p ≤ 0.0001.

we observed a decreased spheroid forming potential in HCT116 and HT29 cells upon treatment with C4 and C5. Suggesting C4 and C5 exert a significant inhibitory effect on tumor development. (A) As compared to control C4 and C5 exhibited a significant decrease in spheroid forming potential of HCT116 cells on day 3, day 7 and day 14. (B) C4 and C5 exhibited a significant decrease in spheroid forming potential of HT29 cells on day 3, day 7 and day 14 as compared to control.

Therapeutic potential of C4 and C5 on cellular migration of HCT116 and HT29 cells was accessedusing wound healing assay. (A) After 48 h of treatment, as compared to control, C4 and C5 exhibited a significant decrease in migration of HCT116 cells. (B) After 48 h of treatment, as compared to control, C4 and C5 exhibited a significant decrease in migration of HT29 cells.

Effect of C4 and C5 on EMT associated markers in CRC cell lines

The effect of C4 and C5 compounds on the expression levels of EMT associated markers like Cyclin D1, Slug, Vimentin, and E-Cadherin (Fig. 9) was determined, we further assessed the effect of C4 and C5 on the expression levels of Snail (Supplementary Fig. 1) and N-Cadherin (Supplementary Fig. 2), thereby providing more validation to our findings. The expression of cyclin D1, Slug and vimentin was found to be decreased in the range 1.3–2.9 in CRC cell lines due to administration of C4 and C5 (Fig. 9 E, F). On the other hand, C4 and C5 induced increase in the levels of E-cadherin in both the cancer cell lines (Fig. 9 G, H). The downregulation of EMT markers by C4 and C5 is directly linked to decreased migration and invasion, as observed in wound healing and spheroid formation assays. By inhibiting Slug, Vimentin, and Cyclin D1, C4 and C5 impair the cellular mechanisms that facilitate metastasis, reinforcing their role in reducing metastatic potential in CRC cells.

C4 and C5 targets CRC related signaling pathways

Our next step was to evaluate the effect of C4 and C5 compounds on key signaling protein levels in colorectal cancer cell lines. It was observed that C4 and C5 significantly reduced the protein levels of Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh. HCT116 and HT29 cells showed a significant decrement of 2.7 and 3.0 folds, respectively, due to C4 treatment whereas C5 resulted in a 1.7 and 1.5 folds, respectively, decrease in protein levels of Wnt3a (Fig. 10 A, B). Levels of Notch1 (Fig. 10 C, D) and Shh (Fig. 10 E, F) also decreased as compared to the control with better results being shown by C4. Concomitant with these changes in protein levels we observed a significant decrease in mRNA levels of these genes when treated with C4 and C5 for 24 h (Fig. 11).

Molecular docking

C4 and C5 were docked against protein targets of Wnt3a (7DRT), Notch1 (5FMA) and Shh (3HO5). The compounds with the least binding energy (kcal/mol) and root mean square deviation (RMSD) conformation were considered as the most suitable pose for docking. The results of binding energies for docking experiments are shown in Table 1. C4 produced the binding energy of − 9.1, − 8.5, − 9.8 kcal/mol when docked with Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh, respectively. Similarly, C5 showed binding energy of − 8.2, − 7.6 and − 8.8 kcal/mol when docked with Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh, respectively. In-silico analysis of these two compounds were discretely interacted with three target proteins viz., Wnt3a, Notch1 and Shh and the 2D and 3D interactions exhibiting good docking scores (Fig. 12). It was observed that C4 exhibited markedly best docking score of − 9.8 against Shh as compared with C5 which showed docking score of − 8.8. The side chain residues of Wnt3a [chain A (Gln75, Gln78, Cys88 and Thr90)], Notch1 [chain A (Arg176, Gln177 and Asp178)] and Shh [chain H (Lys45, Glu53, Ser135, Tyr174, Glu176 and His182)] formed hydrogen bonds with C4. Similarly, the side chain residues of Wnt3a [chain A (Arg82, Thr296, Asp305 and Cys307)], Notch1 [chain A (Cys182, Lys185, Gly187, Cys189 and Gly193)] and Shh [chain H (Glu89, Arg123, Asp147, Arg153 and Ala179)] formed hydrogen bonds with C5 (Fig. 12; Table 2).

Discussion

Colorectal cancer is a multifaceted disease affected by, environmental and genetic factors, standing as a significant public health challenge. Environmental elements, including dietary habits and lifestyle choices, further modulate CRC risk14. High fat and low fibre rich diet, sedentary lifestyles, and inflammatory bowel diseases increase susceptibility to CRC. This disease is intricately linked to inflammation, acting as a crucial driver in its onset and advancement. The intricate relationship between inflammatory processes and the progression of CRC involves the initiation of diverse signaling pathways, including but not limited to STAT3 and NF-κB, further enhancing the oncogenic potential of colorectal cells15. Recent research underscores interventions addressing both the cancer and the underlying inflammatory conditions for a more comprehensive approach to treatment15,16.

Plant-based compounds are very well known to reduce colon cancer in many ways. Medicinal plants contain many bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, polyphenols etc. which can reduce tumor cell proliferation by several mechanisms, such as blocking cell cycle checkpoints and promoting apoptosis17. Traditional medicines have been used globally to treat cancers because of their anti-cancer effects, antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory properties, anti-mutagenic effects, and anti-angiogenic effects11,12. Alcea rosea, a folklore medicinal herb has been used to treat various diseases like inflammation, gastrointestinal infections, renal and urethra infections, hepatitis, malaria, arthritis. The anticancer properties of C4 and C5 align with the traditional use of Alcea rosea in treating inflammatory conditions, suggesting that its anti-inflammatory effects may contribute to the observed reduction in CRC cell viability and tumor progression9,11. This work has been undertaken in response to our preliminary work where Alcea rosea ethyl acetate extract has demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects against CRC cells, preventing further cell division while simultaneously triggering apoptosis. The extract modulated the key signaling pathways involved in CRC development, including the Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt pathways13. In this backdrop, 7 compounds were isolated from AREA and analyzed these compounds on colorectal cancer cell lines by MTT assay and observed that two compounds (C4 and C5) showed strong anticancer activities and we further analyzed these two compounds on various crucial parameters in colon cancer including key signaling pathways. Compounds from Alcea rosea, such as C4 and C5, demonstrate anticancer properties similar to other plant-derived compounds like curcumin and resveratrol. While curcumin targets NF-κB and resveratrol modulates AMPK, Alcea rosea compounds exert their effects by inhibiting Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh pathways, suggesting comparable but distinct mechanisms of action against CRC7,17. Although prolonged exposure to anticancer agents can induce resistance, the simultaneous inhibition of Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh by C4 and C5 may reduce the likelihood of adaptive resistance. Short-term treatments with C4 and C5 over 48 h showed no signs of resistance, but future studies will focus on evaluating potential resistance mechanisms over extended periods6,7. Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may influence the efficacy of plant-derived bioactive compounds. Flavonoids like Kaempferol undergo gut microbial metabolism, potentially enhancing their anticancer properties, highlighting the need for future studies to explore the interactions between C4 and C5 and gut microbiome in CRC treatment15,18.

The Wnt3a gene plays a pivotal role in CRC, influencing key cellular processes through the Wnt signaling pathway. Dysregulation of Wnt3a, often characterized by over-expression, activates downstream targets like β-catenin, fostering uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumor development18,4. This aberration is prevalent in a significant proportion of CRC cases, underscoring Wnt3a’s clinical significance in tumorigenesis5. Our study revealed a notable dose-dependent decrease in both mRNA and protein levels of Wnt3a in both HCT116 and HT29 cells following treatment with C4 and C5 isolated from the ethyl acetate extract of Alcea rosea. Various researchers have documented that many plant compounds mediate anti-cancer effect by decreasing Wnt3a protein and mRNA levels19,20,21.

The Notch1 gene plays a pivotal role in CRC progression, influencing crucial cellular processes like cell fate determination and viability3,2. Disruption of Notch signaling, primarily mediated by Notch1, is implicated in both CRC initiation and metastasis22. This is due to Notch1’s involvement in maintaining the delicate balance of intestinal homeostasis and its dysregulation in CRC development4. Aberrant Notch1 signaling contributes to uncontrolled cell growth and enhanced viability of cancerous cells23. Our study revealed a notable dose-dependent decrease in both mRNA and protein levels of Notch1 in both HCT116 and HT29 cells following treatment with C4 and C5. Compelling evidence from recent studies paints a promising picture of diverse plant metabolites, including curcumin from turmeric, geniposide from gardenia, and betulinic acid from white birch, exhibiting anti-colorectal cancer properties by down-regulating Notch1 signaling at protein as well as mRNA levels24,25,26.

The highly conserved Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling cascade critically regulates colorectal cancer development, influencing crucial cellular processes like proliferation and differentiation. Shh signaling maintains the delicate balance of intestinal stem cell renewal and differentiation, ensuring healthy tissue homeostasis27. However, dysregulation of this pathway has emerged as a key driver in CRC initiation and progression28,29. Emerging research highlights the crucial function of Shh alterations in colorectal tumorigenesis. Studies reveal that Shh over expression and aberrant activation of downstream effectors like Gli1 contribute to uncontrolled cell growth, enhanced survival, and tumor formation in CRC2,30. C4 and C5, which exhibited a remarkable dose-dependent reduction in both Shh protein and mRNA levels in both HCT116 as well as HT29 cells. Driven by the need for diverse Shh inhibitors, our study investigated Alcea rosea, a relatively unexplored plant, for the isolation of novel compounds (C4 and C5) with anticancer and Shh-suppressing potential, which may be a promising for colorectal cancer treatment. The simultaneous modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Shh pathways by C4 and C5 could significantly reshape the tumor microenvironment by impairing cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance, angiogenesis, and promoting immune activation. This could lead to a more differentiated tumor phenotype, reduced metastasis, and enhanced immune surveillance, collectively inhibiting tumor growth and progression1,2,3. C4 and C5 likely target key mediators within the Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways, such as β-catenin, NICD, and Gli proteins, contributing to the observed reductions in cancer cell viability and invasiveness. Future studies will investigate potential crosstalk between these pathways to uncover synergistic effects25,26. Reduced Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh levels translate into decreased β-catenin, NICD, and Gli activity, contributing to lower proliferation, increased apoptosis, and enhanced tumor differentiation, collectively impairing CRC progression4.

In the dynamic arena of cancer research, in silico molecular docking has emerged as a powerful computational tool, spearheading the fight against CRC. This innovative technique, fuelled by the precision of algorithms, simulates the intricate interplay between small molecules, potential drug heroes, and their protein partners within cancer cells31. By dissecting this molecular ballet, in silico docking unlocks a wealth of insights, predicting how effectively these molecules might bind and interact with their target proteins. Armed with its ability to decipher binding affinities and interaction modes, it empowers researchers to design novel drugs or refine existing ones with pinpoint accuracy, paving the way for more targeted and potent therapeutics32. In the present study, C4 exhibited the best binding affinity, mediated by a high-affinity binding interaction with Shh, when docked with Wnt3a followed by when docked with Notch1. Similarly, C5 exhibited the best docking affinity, mediated by a high-affinity binding interaction with Shh, Wnt3a followed by Notch1. Previously, Elengoe and co-workers documented that Allicin exhibited a binding affinity of -4.968 kcal⋅mol− 1 when docked with p53, Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate exhibited a binding score of -6.490 kcal⋅mol− 1 when docked with APC, and Gingerol showed binding affinity of -6.034 kcal⋅mol− 1 when docked with EGFR33. Our observations indicate that C4 and C5 show superior docking affinities with Shh and Wnt3a, followed by Notch1, compared to the findings of Elengoe et al. This suggests that C4 and C5 possess potent anti-colorectal cancer activity.

Materials and methods

Plant material collection and extraction

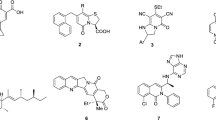

The seeds of Alcea rosea were collected from different geographical locations of Kashmir Valley, India in the month of April 2020. A voucher specimen (KASH-Bot/ku/AR-707-IA) was deposited in the herbarium at the (COPT) Centre of Plant Taxonomy, Department of Botany, University of Kashmir. The seeds were shade-dried and pulverized to powder by utilizing an electric grinder. The powdered sample (5.3 kg) was successively extracted using soxhlet (60 –85 °C) with various solvents for 72 h to obtain hexane (ARH), ethyl acetate (AREA), ethanol (ARE), methanol (ARM) and aqueous (ARAQ) extracts. These extracts were filtered and dried using rotary evaporator. Thereafter, the acquired dried extracts were stored at 4 °C in the refrigerator till further use. Purification of compounds from the active extracts was carried through column chromatography and structure elucidation of the isolated compounds was done by HRMS, NMR, and RP-HPLC13,26.

MTT assay

With minimal alterations, the MTT assay was performed according to the protocol described by Marković34. The human colon cancer cell lines HCT116, HT29, and SW480 were procured from the NCCS (National Centre for Cell Science), Pune, India and were cultured in DMEM with additional supplements of 100 µg/ml penicillin, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, and streptomycin 100 µg/ml (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). Optimal growth conditions for the cultures were achieved in a Galaxy 170 R CO2 incubator (New Brunswick), precisely maintaining 5% CO2, 95% relative humidity, and 37 °C. All the cell lines used in this experiment were between 3 and 20 passages. Seven pure compounds obtained from column chromatography of Alcea rosea Ethyl Acetate extract (AREA) was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the overall quantity of DMSO utilized equaled or fell below 0.1% of the cell growth media volume. In these assessments, HT29 (3500 cells/well), HCT116 cells (2,500 cells/well), and SW480 (2500 cells/well) were planted in plates with 96 wells. Following a 24-hour period, different concentrations (18.67–56.45 µg/ml) of pure compounds were applied to the cells in each well. The medium of cell growth was changed with a volume of 100 µl of recently prepared media 24 and 48 h after treatment. After 72 h, the cell growth media were replenished with 100 µl of fresh media with 50 µg of MTT. Following the period of incubation at 37 °C for 4 h in a CO2 incubator, MTT-containing media was withdrawn, and the reduced formazan dye was completely dissolved in each well by introducing 100 µl of DMSO. Followed by gentle mixing, an ELISA microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance at a wavelength of 570 nm. The focus on C4 and C5 stems from MTT assay results, where these compounds exhibited significant cytotoxicity against CRC cells, unlike the other five isolated compounds, indicating their potential as lead therapeutic agents.

Colony formation assay

We examined the effect of compounds 4 and 5 on the colony forming potential of CRC cell lines HCT116 and HT29. Initially, cellular entities were seeded in six-well plates35, at a density ranging from 1000 to 1500 cells per well. Following 48-hour incubation, fresh media containing the respective compounds were added. The examination was conducted over a span of 14 to 18 days, with regular medium and compound replenishment every three days to maintain treatment efficacy. Colonies were monitored using an inverted microscope until they reached a substantial size. Once achieved, the colonies underwent fixation using 3.7% paraformaldehyde solution (in PBS) and were subjected to staining with crystal violet at a concentration of 0.05%. Images of the plates were captured, and colony counting was performed utilizing the ImageJ application. Each cell category and compound treatment were independently replicated three times to ensure reliability.

Wound healing assay

To evaluate the migratory behavior of HCT116 and HT29 cell lines in the presence or absence of compounds, cells were seeded in a 12-well plate until they reached 70% confluency and then permitted to adhere overnight. Afterward, we created uniform wounds in the cell monolayer using scratch inserts. Following 24-hour incubation, with gentle precision, the embedded scratch inserts were carefully extracted, and subsequently rinsed with PBS. To quantify cell migration, the cells were fixed using 3.7% paraformaldehyde and images of the cells were captured. The cell movement into the wound site was analyzed using the ImageJ software36.

Spheroid formation assay

HCT116 and HT29 cells were planted as an individual-cell dispersion, with 2500 cells per well, onto ultralow attachment 6-well plates. The culture medium used was DMEM/F12 enhanced with B27 supplement and SingleQuot™. After overnight incubation, the cells were treated with compounds C4 (18.67–32.25 µg/ml) and C5 (32.02–42.1 µg/ml) and maintained in culture for 14 days. The resulting cell spheres were visualized utilizing a phase-contrast inverted microscope from Nikon37.

DAPI/PI staining

HCT116 and HT29 cells were exposed to compounds C4 and C5 for duration of 48 h. Subsequently, the cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde followed by 2X PBS washing. To visualize cell nuclei, DAPI was used, while dead cells were identified using propidium iodide (PI) staining. The stained cells were then examined under a Floid™ Cell Imaging System (Thermo Scientific, USA)38.

Acridine orange and ethidium bromide staining

DNA-binding dyes, acridine orange (AO) and ethidium bromide (EtBr) were used for this assay. HCT116 and HT29 cells were initially seeded in a 12-well plate and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to compounds C4 and C5 and further incubated for 48 h. For staining, a mixture of AO (100 µg/mL) as well as EtBr (100 µg/mL) in 1x PBS was applied to each well, followed by a 5-minute incubation at room temperature. The stained cells were then visualized under a Floid™ Cell Imaging System (Thermo Scientific, USA)39.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

The impact of isolated compounds was evaluated on the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in HCT116 and HT29 cells. In 12-well plates cells were cultured and exposed to aforementioned compounds for duration of 48 h. To visualize ROS levels, the cells were stained with 10 µM DCFH-DA for duration of 30 min in a dark environment. Subsequently, by using the Floid™ Cell Imaging Station (Thermo Scientific, USA) to observe the fluorescence corresponding to ROS the cells were captured. The images were then analyzed in Image-J software for the determination of changes in ROS40.

Rhodamine-123 staining assay (MMP)

The membrane potential of the mitochondria was evaluated using Rhodamine 123. Aforementioned CRC cells were cultured on plates having 24-wells and exposed to compounds C4 and C5 for 48 h. After treatment, the cells were stained using Rhodamine-123 at a concentration of 10 µM for duration of 15 min at a temperature of 37 ℃ in the absence of light. Subsequently, the cells were rinsed three times with 1x PBS and alterations in the potential of the mitochondrial membrane were visualized using the FLoid™ Cell Imaging Station (Thermo Scientific, USA). Furthermore, post-staining, the intensity of fluorescence was quantified utilizing Image-J software for the determination of changes in MMP41.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

HCT and HT29 cells were seeded on 6 cm dishes followed by treatment with compounds C4 and C5 for 48 h. Post-treatment cells were collected at 1X ice-cold PBS and total RNA was isolated utilizing TRIzol reagent. The complimentary first strand cDNA was synthesized using a revert aid cDNA synthesis kit. After that, the relative mRNA levels of the interesting genes were determined by performing qPCR using SYBR Green 2X PCR master mix (Thermo™ USA) in a light cycler 480-II (ROCHE).

Western blotting and cell lysis

Following the methodology outlined by Nile and coworkers42, HCT116 and HT29 cells subjected to C4 and C5 compounds and were rinsed two times with PBS cooled on ice, gathered in small centrifuge tubes, and subjected to lysis using NP-40 lysis buffer kept at low temperature (20% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4,5 mM NaF, 1 mM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride, and a protease inhibitor cocktail 10 µl/ml of lysis buffer, and 2 mM EDTA for a duration of 30 min. The lysed cells were centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was collected and preserved at -80 ◦C for future utilization. Equivalent amounts of protein (30–100 µg), as quantified by the Bradford method, were segregated using 10–15% SDS-PAGE, depending upon the size of the target protein. Prior to transferring proteins, the PVDF membrane was initially treated with methanol for activation and subsequently washed with double-distilled water. This was succeeded by the transfer of proteins onto it by semidry transfer method utilizing semidry transfer apparatus (Hoefer TE77XP, USA). The transfer buffer comprised of 3 different buffers viz. cathode (pH 9.4), anode-I (pH 10.4), and anode-II (pH 10.4). The blocked membrane was left overnight to incubate with a primary antibody, which was diluted in a 3% BSA solution at a temperature of 4 ◦C. On the following day, the membrane underwent three washes with a washing buffer containing 0.05% Tween-PBS and was then subjected to incubation with a secondary antibody. The membrane underwent an additional three washes and was then subjected to the detection of signals utilizing Licor equipment. Quantitative analysis for all the blots was conducted through densitometry using ImageJ software.

Molecular docking study

The Protein Data Bank RCSB (https://www.rcsb.org/) was used to acquire the structures of selected proteins viz., Wnt-3a, SHH, Notch-1 in PDB format. Structures of isolated compounds from Alcea rosea ethyl acetate extract were obtained from PubChem online (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and each compound was converted to PDBQT file format using AutoDock tools (1.5.6)43 and Discovery studio 2021 (BIOVIA)44, resulting in an input Journal Pre-proof 9 compound/ligand file for docking study in AutoDock Vina. For the aforementioned compounds, 54 maximal conformations were created in the BIOVIA Discovery studio. Auto Dock tools version 1.5.6 was employed to calculate the docking score for relevant ligand and protein interactions. After docking, the optimal poses were screened by looking at binding energy (kcal/mol) and cluster number. BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer was used to investigate both hydrophobic and hydrophilic molecular interactions.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed at least thrice. Statistical significance was determined through one-way ANOVA, utilizing the capabilities of both Microsoft Excel version 2311 and GraphPad Prism version 10.1.2 software. p-values falling below the threshold of 0.05 were considered statistically significant and * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001, and **** = P < 0.0001 highly significant.

Conclusion

In light of the experimental findings and the above discussion, we conclude that Alcea rosea possesses significant anti-colorectal cancer potential. The lack of documented toxicity associated with Alcea rosea despite its long-standing use in traditional medicine serves as a testament to its safety. Based on our study we subjected ethyl acetate extract of Alcea rosea (AREA) for isolation of active compounds which yielded 7 fractions out of which only 2 fractions (C4 and C5) exhibited a significant concentration-dependent inhibitory effect on MTT activity, colony formation activity, wound healing activity, spheroid formation activity, DAPI-PI staining, acridine-orange and ethidium bromide staining, ROS measurement and rhodamine-123 staining in both HCT116 and HT29 colon cancer cells. Furthermore, C4 and C5 exhibited a marked reduction in protein and mRNA levels of Wnt3a, Notch1, and Shh. Moreover, protein levels of Slug, Cyclin D1, and Vimentin were significantly decreased in a concentration-dependent manner in both HCT116 and HT29 cells. Additionally, the administration of C4 and C5 led to a notable upregulation of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3, and E-cadherin, as measured by western blot analysis. We conclude that the constituents present in the ethyl acetate extract of Alcea rosea will serve as best therapeutic agents against the colon cancer and in future, these compounds will be subjected for their structural elucidations and their additional in vitro and in vivo experiments will be helpful for validating and optimizing the findings of this study. Future work will focus on validating molecular targets through RNAi or CRISPR, optimizing the structure of C4 and C5 to enhance bioavailability, and evaluating their efficacy in preclinical models such as patient-derived xenografts (PDX). Combination studies with existing therapies may further enhance their therapeutic potential.

Data availability

Data will be available on the reasonable request. For further inquiries contact corresponding author Dr Showkat Ahmad Ganie.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

Alcea rosea

- TLC:

-

Thin layer chromatography

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide

- HCT116:

-

Human colorectal carcinoma cell line

- HT29:

-

Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line

- DAPI:

-

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- NOTCH:

-

Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- AO:

-

Acridine orange

References

Pothuraju, R. et al. Colorectal cancer murine models: Initiation to metastasis. Cancer Lett., 216704 (2024).

Brisset, M., Mehlen, P., Meurette, O. & Hollande, F. Notch receptor/ligand diversity: Contribution to colorectal cancer stem cell heterogeneity. Front. Cell. Dev. Biology. 11, 1231416 (2023).

Ebrahimi, N. et al. Cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer: Signaling pathways involved in stemness and therapy resistance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 182, 103920 (2023).

Zhang, X., Dong, N. & Hu, X. Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 23, 880–896 (2023).

Pereira, F., Fernández-Barral, A., Larriba, M. J., Barbáchano, A. & González‐Sancho, J. M. From molecular basis to clinical insights: A challenging future for the vitamin D endocrine system in colorectal cancer. FEBS J. (2023).

Wang, Z., Liu, Y. & Asemi, Z. Quercetin and microRNA interplay in apoptosis regulation: A new therapeutic strategy for cancer? Curr. Med. Chem. (2024).

Nguyen, T. N. et al. Research on chemical constituents, anti-bacterial and anti-cancer effects of components isolated from Zingiber officinale Roscoe from Vietnam. Plant. Sci. Today. 11, 156–165 (2024).

Pogorzelska, A. et al. Antitumor and antimetastatic effects of dietary sulforaphane in a triple-negative breast cancer models. Sci. Rep. 14, 16016 (2024).

Hussain, L., Akash, M. S. H., Tahir, M., Rehman, K. & Ahmed, K. Z. Hepatoprotective effects of methanolic extract of Alcea rosea against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. ||| Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 9, 322–327 (2014).

Abdel-Salam, N. A. et al. Flavonoids of Alcea rosea L. and their immune stimulant, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities on hepatocellular carcinoma HepG-2 cell line. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 702–706 (2018).

Dar, P. A., Ali, F., Sheikh, I. A., Ganie, S. A. & Dar, T. A. Amelioration of hyperglycaemia and modulation of antioxidant status by Alcea rosea seeds in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Pharm. Biol. 55, 1849–1855 (2017).

Lim, T. Edible Medicinal and Non Medicinal Plants: Volume 8, Flowers 292–299 (Springer, 2014).

Dar, K. B. et al. Immunomodulatory efficacy of Cousinia Thomsonii CB Clarke in ameliorating inflammatory cascade expressions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 300, 115727 (2023).

Wang, M., Chen, S., He, X., Yuan, Y. & Wei, X. Targeting inflammation as cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17, 13 (2024).

Tahawy, L. T. L. The Microbiome and cancer unveiling the microbe-tumor crosstalk. Acta Sci. Microbiol. (ISSN: 2581–3226) 7 (2024).

He, R. et al. Unveiling the immune symphony: Decoding colorectal cancer metastasis through immune interactions. Front. Immunol. 15, 1362709 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Sulforaphane, a dietary component of broccoli/broccoli sprouts, inhibits breast cancer stem cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 2580–2590 (2010).

Pan, H. et al. The odontoblastic differentiation of dental mesenchymal stem cells: Molecular regulation mechanism and related genetic syndromes. Front. Cell. Dev. Biology. 11, 1174579 (2023).

Sher, A. et al. In vitro analysis of cytotoxic activities of monotheca buxifolia targeting WNT/β-catenin genes in breast cancer cells. Plants 12, 1147 (2023).

Quarshie, J. T. et al. Cryptolepine suppresses colorectal cancer cell proliferation, stemness, and metastatic processes by inhibiting WNT/β-Catenin signaling. Pharmaceuticals 16, 1026 (2023).

Kombiyil, S. & Sivasithamparam, N. D. In vitro anti-cancer effect of Crataegus oxyacantha berry extract on hormone receptor positive and triple negative breast cancers via regulation of canonical wnt signaling pathway. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195, 2687–2708 (2023).

Liu, A. et al. PRMT5 methylating SMAD4 activates TGF-β signaling and promotes colorectal cancer metastasis. Oncogene 42, 1572–1584 (2023).

Liao, J. et al. Long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) H19: An essential developmental regulator with expanding roles in cancer, stem cell differentiation, and metabolic diseases. Genes Dis. 10, 1351–1366 (2023).

Tong, Q. & Wu, Z. Curcumin inhibits colon cancer malignant progression and promotes T cell killing by regulating miR-206 expression. Clin. Anat. 37, 2–11 (2024).

Kimura, Y., Sumiyoshi, M. & Taniguchi, M. Geniposide prevents tumor growth by inhibiting colonic interleukin-1β and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 via down-regulated expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and thymocyte selection-associated high mobility box proteins TOX/TOX2 in azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 118, 110077 (2023).

Chen, J. L. et al. Betulinic acid inhibits the stemness of gastric cancer cells by regulating the GRP78-TGF-β1 signaling pathway and macrophage polarization. Molecules 28, 1725 (2023).

Zhong, X. et al. Glutamine metabolism in tumor metastasis: Genes, mechanisms and the therapeutic targets. Heliyon (2023).

Alshahrani, S. H. et al. LncRNA-miRNA interaction is involved in colorectal cancer pathogenesis by modulating diverse signaling pathways. Pathology-Research Pract., 154898 (2023).

Guo, Q. et al. Tumor microenvironment of cancer stem cells: Perspectives on cancer stem cell targeting. Genes Dis. 11, 101043 (2024).

Varlı, M. et al. 1′-O-methyl-averantin isolated from the endolichenic fungus Jackrogersella sp. EL001672 suppresses colorectal cancer stemness via sonic hedgehog and notch signaling. Sci. Rep. 13, 2811 (2023).

Tur Razia, I. et al. Recent trends in computer-aided drug design for anti-cancer drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 23, 2844–2862 (2023).

Tapera, M. et al. Molecular hybrids integrated with imidazole and hydrazone structural motifs: Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Liq. 391, 123242 (2023).

Elengoe, A. & Sebestian, E. In silico molecular modelling and docking of allicin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate and gingerol against colon cancer cell proteins. Asia Pac. J. Mol. Biol. Biotechnol., 51–67 (2020).

Marković, T. et al. Insights into molecular mechanisms of anticancer activity of Juniperus communis essential oil in HeLa and HCT 116 cells. Plants 13, 2351 (2024).

Mehraj, U. et al. Adapalene and doxorubicin synergistically promote apoptosis of TNBC cells by hyperactivation of the ERK1/2 pathway through ROS induction. Front. Oncol. 12, 938052 (2022).

Kaleağasıoğlu, F. & Berger, M. R. Differential effects of erufosine on proliferation, wound healing and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 31, 1407–1416 (2014).

Kulesza, J., Paluszkiewicz, E. & Augustin, E. Cellular effects of selected unsymmetrical bisacridines on the multicellular tumor spheroids of HCT116 Colon and A549 Lung Cancer cells in comparison to monolayer cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 15780 (2023).

Song, J. et al. Active compound of Pharbitis Semen (Pharbitis nil seeds) suppressed KRAS-driven colorectal cancer and restored muscle cell function during cancer progression. Molecules 25, 2864 (2020).

Mostafa, Y. S. et al. L-glutaminase synthesis by marine Halomonas meridiana isolated from the red sea and its efficiency against colorectal cancer cell lines. Molecules 26, 1963 (2021).

Guha, S. et al. Crude extract of Ruellia tuberosa L. flower induces intracellular ROS, promotes DNA damage and apoptosis in Triple negative breast Cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol., 118389 (2024).

Kowaltowski, A. J. & Abdulkader, F. How and when to measure mitochondrial inner membrane potentials. Biophys. J. (2024).

Nile, A. et al. Cinnamaldehyde-Rich cinnamon extract induces cell death in colon cancer cell lines HCT 116 and HT-29. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8191 (2023).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Nosiri, C. I., Anyanwu, C., Ike, W. U., Okpara, I. J. & Nwaogwugwu, C. J. (ASPET, 2024).

Acknowledgements

I am deeply thankful for the support and grant provided by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) with grant No. (52/07/2020 (B)-Bio/BMS) and the authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through small group research project under grant No. RGP1/133/45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. A. P: Writing- original draft, Software, Experimental work, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. I. A. M. and S. A.: Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. B.A.B.: formal analysis. M. U. H.: Formal analysis, validation. G.S.Z.: Formal analysis. N.B.: Formal analysis. S. V.: Data curation, Conceptualization, Supervision. S. A. G.: Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parry, R.A., Mir, I.A., Bhat, B.A. et al. Exploring the cytotoxic effects of bioactive compounds from Alcea rosea against stem cell driven colon carcinogenesis. Sci Rep 15, 5892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89714-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89714-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Restoring apoptosis in breast cancer via peptide mediated disruption of survivin IAP interaction

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

AXL tyrosine kinase inhibitor TP-0903 induces ROS trigger neuroblastoma cell apoptosis via targeting the miR-335-3p/DKK1 expression

Cell Death Discovery (2025)

-

Honeybee associated Aspergillus niger AW17 as a source of selective anticancer compounds with cytotoxicity evaluation in human cancer cell lines

Scientific Reports (2025)