Abstract

The scarcity of effective biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for predicting disease onset and progression in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a major challenge. Conventional drug discovery approaches have been unsuccessful in providing efficient interventions due to their ‘one-size-fits-all’ nature. As an alternative, personalised drug development holds promise to pre-select responders and identifying suitable indicators of drug efficacy. In this exploratory study, we have established a pipeline with the potential to guide patient stratification studies before clinical trials. This pipeline uses 2D and 3D in vitro models of monocyte-derived microglia-like cells (MDMi) from AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients, and matched healthy control (HC) individuals. By profiling cytokine responses in these models using multidimensional analyses, we have observed that the 3D model offers a more defined separation of profiles between individuals based on disease status. While this pilot study focuses on AD and MCI, future investigations incorporating other neurodegenerative disorders will be necessary to validate the pipeline’s findings and demonstrate its broader applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias becoming increasingly prevalent, there is a pressing medical need to develop effective therapeutic strategies. Approved interventions in recent years, such as the controversial anti-amyloid drug aducanumab, have been extremely scarce and their efficacy in providing cognitive benefits is being questioned1. The limited success in drug approval can be attributed to complex molecular disease drivers, inaccurate diagnostic criteria, and inefficient biomarkers of disease onset and progression2,3.

Current clinical testing approaches for assessing new therapeutics in AD also come with important caveats. These challenges include the variability in treatment responses to drug and placebo among participants, the use of inappropriate statistical methodologies to assess drug effect size, and a lack of correlation between biomarker changes and cognitive improvement1,4. Furthermore, ineffective preclinical AD drug efficacy studies contribute to a flawed drug development pipeline due to their poor rigour, reproducibility, predictive value, and limited translation into clinical outcomes. These limitations are partly attributed to the shortcomings of currently used preclinical model systems, including animal and cell disease models, which inadequately recapitulate human disease processes5. To address these challenges, there is a need for more informative preclinical studies that differentiate between asymptomatic individuals and patients at various disease stages. Such studies may lead to improved subject selection in subsequent clinical trials and the identification of more predictive drug efficacy targets with translational relevance to patients.

Novel technologies have emerged to improve preclinical drug testing for AD. One such tool is the monocyte-derived microglia-like cell model (MDMi)6,7. MDMi offer several advantages over other human microglia cell models, such as their cost-effective and rapid derivation from easily accessible blood samples, and have shown improved characteristics when differentiated in a more physiologically relevant 3D model8,9. Furthermore, MDMi permit the longitudinal assessment of patient-specific drug responses, allowing for the simultaneous monitoring of drug effects across patients10. Additionally, MDMi exhibit disease-specific features associated with neurodegenerative diseases, validating their use as an in vitro platform for preclinical drug studies targeting neuroinflammation7,11,12,13.

Here, we present a pilot pipeline that uses 2D and 3D MDMi models derived from healthy donors, and patients with AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Our approach uses multidimensional analysis to stratify patient profiles and identify potential responders for subsequent clinical drug trials. Although this study is limited to AD and MCI cohorts, expanding the analysis to include other neurodegenerative diseases will be critical for validating the pipeline’s specificity. We validated this pipeline with two FDA-approved microglia-targeted drugs: minocycline and IC14. Minocycline, a well-known anti-inflammatory drug, has shown effectiveness in rodent and immortalised microglial models but has failed in clinical testing for AD patients14,15,16. IC14, an anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody, is currently under clinical investigation for treating inflammation related to SARS-Cov-2 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and has potential for repurposing in AD patients17,18,19. We have identified differences in MDMi drug responses, which could aid in predicting the efficacy of new compounds before clinical evaluation and provide insights into disease progression. Overall, this pipeline holds promise for pre-selecting patients along with validating and predicting candidate drugs before clinical trials, thus yielding informative biomarkers of drug efficacy in a personalised manner.

Methods

Study cohorts

Young healthy donors with no clinical symptoms (Table 1) were recruited at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute (QIMRB), Queensland, Australia.

Healthy control (HC), Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) donors (Table 2) were recruited through the Prospective Imaging Studying of Aging: Genes, Brain and Behaviour study (PISA) at QIMRB. The recruitment strategy consisted of online cognitive assessments, genome-wide genotyping, multi-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and neuropsychological testing20. HC participants showed no cognitive alteration and were classified based on their genetic risk to develop AD. Those with low risk did not carry APOE ε4 and were in the lowest quintile of the AD PRS (polygenic risk score) no-APOE (APOE region excluded), which accounts for additional AD genetic risk variants. Experiments adhered to the ethical guidelines on human research outlined by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) and have been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees (HREC) of QIMRB and the University of Queensland. The donors’ informed consent was obtained before participation in the study.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from blood

PBMCs were isolated from peripheral venous blood samples within 2 h of blood withdrawal6. SepMate™ tubes (StemCell Technologies, BC, Canada) were used for the isolation according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PBMCs were washed twice with PBS containing 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and subsequently frozen in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and 90% (v/v) heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) (ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA).

Generation of 2D and 3D MDMi cultures

MDMi generation in 2D was performed as described in6,7. Briefly, PBMCs were seeded onto Matrigel-coated (Corning, NY, USA) plates and monocytes (adherent cells) were cultured in serum-free RPMI-1640 GlutaMAX medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 0.1 μg/mL of interleukin (IL)−34 (IL-34) (Lonza, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland), 0.01 μg/mL of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Lonza, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 14 days.

MDMi generation in 3D was performed as described in7. Briefly, PBMCs-derived monocytes were mixed with Matrigel, which had been previously diluted in culture medium at a 1:3 ratio. Matrigel-cell mixtures were then cultured in serum-free RPMI-1640 GlutaMAX medium containing 0.1 μg/mL IL-34 and 0.01 μg/mL GM-CSF for 35 days.

We quantified the percentage and reproducibility of monocyte conversion into MDMi across multiple donors (n = 6). Monocytes, comprising 6% to 10% of total PBMCs, consistently achieved a conversion rate of approximately 99%, with minimal apoptosis (less than 1% caspase 3/7 positivity by day 14). This high conversion efficiency was reproducible across replicates, demonstrating the robustness of the differentiation process (Fig. S1A-C).

Bright field images were captured using the Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope with 5.1MP CMOS digital camera.

Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy imaging

MDMi were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min in 2D or overnight in 3D, and then washed twice with PBS. Permeabilisation was performed with 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS for 10 min in 2D and 30 min in 3D, followed by blocking overnight at 4 °C with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) in PBS. Primary anti-IBA1 antibody (#019–19741, Wako) was diluted 1:500 in blocking solution and incubated at 4 °C overnight in 2D or 24 h in 3D. An Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (#A-11034, ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA) diluted in blocking solution was incubated at RT for 2 h in 2D or 5 h in 3D. Up to five washes were performed with 0.1% Triton-X 100 in PBS following primary and secondary antibody incubations. Cell nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/mL Hoechst solution (#33342, ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA). Immunofluorescence images were captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM-780, Carl Zeiss) and processed using the Zeiss ZEN software.

pHrodo-labelled E. coli bead phagocytosis by 2D MDMi

Phagocytosis in 2D was examined using live cell imaging on the IncuCyte ZOOM (Essen BioSciences, MI, USA). Sonicated fluorescent pHrodo-labelled E. coli particles (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) were added to 2D MDMi cultures. Cytochalasin D (10 µM), an inhibitor of actin polymerisation, was added 10 min before the assay to block phagocytosis (Fig. S1D, E). Particle uptake was visualised by capturing images every hour with a 10X objective using standard phase contrast and red fluorescence settings.

Synaptosome isolation and live cell imaging of phagocytosis by 3D MDMi

Synaptosomes were isolated from ReNcell VM-derived cultures, which were directed towards a neuronal lineage for 60 days. The Syn-PER Synaptic Protein Extraction Reagent protocol (#87793, ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA) was followed. Briefly, 2 mL of ice-cold Syn-PER reagent were added to a confluent T75 flask containing ReNcell VM-derived neurons. After scraping the flask surface, the cell lysate was collected and centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 10 min at 4ºC. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4ºC, resulting in a pellet of synaptosomes. The synaptosome pellet was then resuspended in 100 μL Syn-PER reagent and protein concentration was quantitated using a Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (#23225, ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA). For live cell imaging of synaptosome phagocytosis in 3D MDMi, synaptosomes were tagged using the CellVue Claret Far Red Fluorescent dye (#Miniclaret, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), as per manufacturer’s instructions. Tagged synaptosomes were added at 10 µg/well to 3D MDMi cultured for 35 days in black optical 96-well plates. Cultures were scanned using EVOS FL Auto 2 (ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA). Multiple Z-stack planes were imaged every 3 h for 7 days using a 20X objective. A total of 10 fields of view were scanned per well.

Treatment of MDMi with LPS and drugs

LPS (O55:B5, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was dissolved in RPMI-1640 GlutaMAX medium and stored at −20 °C, as per manufacturer’s instructions. For MDMi treatment, LPS was added to 2D and 3D MDMi at a concentration of 10 ng/mL for 24 h. Treatments with the FDA-approved drugs minocycline and IC14 were performed in 2D MDMi after 14 days of culture, and in 3D MDMi after 35 days of culture. Drug concentrations were optimised in 2D cultures, as 3D cultures withstand higher drug concentrations. Minocycline (#252859, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was reconstituted in DMSO and used at 1 μM for 24 h. IC14 (kindly provided by Implicit Bioscience) was used at 0.05 ng/mL for 24 h. DMSO was used as vehicle control for minocycline treatments. An IgG4 antibody (#403702, Australian Biosearch, WA, Australia) was used as isotype control for IC14 treatment. To assess the capacity of minocycline and IC14 to reduce LPS-induced inflammation in 2D and 3D MDMi, drugs or the respective vehicle controls were added for 1 h in 2D cultures, or 2 h in 3D cultures, prior to LPS exposure. Following drug pre-treatment, cultures were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS. Cultures were harvested for downstream analysis after 24 h of LPS incubation.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was extracted using a Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (#R2050, Zymo Research, CA, USA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Conversion to cDNA was carried out using a SensiFAST cDNA synthesis kit (#BIO-65054, Bioline, London, UK). For qRT-PCR, cDNA was diluted 1:10 and combined with SensiFAST SYBR® Lo-ROX master mix (#BIO-94005, Bioline, London, UK) and gene-specific primers (Table S2). The qRT-PCR runs were performed as triplicates on the Applied Biosystems ViiA 7 system (ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA). For data normalisation, the endogenous control 18S was used as a housekeeping gene. Relative gene expression levels were calculated by normalising delta cycle threshold (ΔCt) values to 18S.

Multiplex bead-based immunoassay

Cytokine protein secretion was detected in conditioned medium using the LEGENDplex™ Human Inflammation kit (#740809, BioLegend, CA, USA). Conditioned medium was incubated with a cocktail of antibody-conjugated capture beads, followed by the addition of biotinylated detection antibodies and streptavidin–phycoerythrin (SA-PE). The fluorescent signal intensity of the capture bead-analyte-detection antibody-SA-PE sandwiches correlated with the concentration of cytokines in the samples. Signals were acquired on a BD LSR Fortessa 4A (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) using FACSDiva software, and analysed using Qognit (BioLegend, CA, USA). Cytokine concentrations (pg/mL) were normalised to cell density. When cytokines were undetected, concentrations were calculated by dividing the limit of detection (LOD) by square root of 2.

LDH assay

The CytoTox-ONE Homogeneous Membrane Integrity Assay (#G7890, Promega, WI, USA) was used to determine drug cytotoxicity on MDMi. Briefly, culture medium from untreated, vehicle (DMSO)- and drug-treated MDMi cultures was collected and mixed (1:1 ratio) with CytoTox-ONE reagent in an opaque 96-well black plate (#137101, ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA). The plate was incubated for 10 min at RT and the resulting fluorescence signal (excitation 560 nm/emission 590 nm) was measured in a BioTek Synergy H4 plate reader (ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA), using automatic gain adjustment. To estimate a maximum LDH release control, the kit’s lysis solution (9% (w/v) TritonX-100/water) was added to untreated MDMi and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 15 min. LDH release (as %) was calculated as (experimental—culture medium background)/(maximum LDH release—culture medium background)*100.

Statistical analysis

For cohort-based analyses, GraphPad Prism software version 9 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used. Data were presented as bar graphs with mean ± SEM or SD. Cytokine responses from young donors to increasing drug concentrations were averaged and compared using repeated-measures one-way ANOVA. To measure drug efficacy in the cohorts, drug responses were calculated relative to LPS-stimulated responses and log-transformed and efficacy was tested using one-sample t-test against a null hypothesis (log(relative change) = 0).

For donor-specific analyses, R package (version 4.1.0) was used. Cytokine responses were log-transformed. A Kruskal–Wallis test was used to examine differences between cohorts in drug responses. Spearman correlation was used for correlation analyses. For multivariate analyses, missing values were imputed with the mean of the log-transformed relevant cytokine values and data were centred and scaled. Principal component analysis (PCA) was visualised using plots where enclosing ellipses were estimated using Khachiyan algorithm. Hierarchical clustering was preformed using Euclidian distance and complete linkage clustering and visualised using heatmaps. For ranking analyses, mean cytokine and donor responses were ranked based on geometric mean fold change. Drug-mediated reduction of inflammation was presented as a percentage change from LPS-treated responses.

Results

MDMi in 2D and 3D models recapitulate key markers of microglial cell identity and phagocytic function

MDMi established from blood-derived monocytes in 2D and 3D models acquired a ramified morphology characteristic of brain microglia, as shown by phase contrast imaging and immunostaining with the pan-microglial marker IBA1 (Fig. 1A). To characterise the differentiation of MDMi from monocytes between the two models, we compared the mRNA expression of bona fide microglia markers at the longitudinal level. We observed a significant upregulation of IBA1, P2RY12, PROS1, GPR34, GAS6, C1QA, TREM2 and TMEM119 after 14 days of differentiation in 3D compared to 2D (Fig. 1B). This shows that the 3D culture environment enhances the microglia-like transcriptomic signature of MDMi, in agreement with our previous findings7. Lastly, we confirmed that MDMi exhibit phagocytic competence, as demonstrated by the uptake of pHrodo-labelled E. coli particles in 2D (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1), and the engulfment and subsequent digestion of membrane-tagged synaptosomes in 3D (Fig. 1D).

Microglial marker expression and phagocytic function in 2D and 3D MDMi models. (A) Phase contrast and immunofluorescence images of 2D and 3D MDMi derived from young healthy individuals. Scale bars are 50 μm. (B) Time course of mRNA expression levels of IBA1, P2RY12, PROS1, GPR34, GAS6, C1QA, TREM2 and TMEM119 in monocytes (n = 8 donors), 2D (n = 5–6 donors) and 3D (n = 5–7 donors) MDMi differentiated for 7 and 14 days. Two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test, significance shows 2D vs 3D; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) Representative phase contrast images of the uptake of pHrodo‐labelled E.coli particles (red) by 2D MDMi throughout a 1 h, 5 h and 10 h time course. Scale bars are 300 μm. (D) Representative phase contrast images of the uptake of membrane-tagged synaptosomes (red) by 3D MDMi. Synaptosome uptake occurs at 3 h (white arrowhead), followed by intracellular degradation occurring after 6-9 h (yellow arrowheads). Scale bars are 100 μm.

Together, MDMi recapitulate signature features of microglial cell identity and function, with the 3D model improving these characteristics over its 2D counterpart. Given the advantages of MDMi as a clinically relevant in vitro platform, we next aimed to assess if the 3D model would prove more informative to pre-select drug responsive patients for clinical trials.

Mean drug responses show no difference between cohorts of healthy individuals and dementia patients

To evaluate the capacity of 2D and 3D models of MDMi to discriminate drug responses between dementia patients at different disease stages, we established MDMi derived from a cohort of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (n = 3 donors) and AD (n = 3 donors) patients, and a cohort of matched healthy control (HC) individuals (n = 6 donors) (Fig. 2A). HC individuals were matched for age, sex, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype with the patient cohorts, and were recruited based on their genetic risk to develop late-onset AD (20). Donor demographic and clinical details are provided in Table 2. The cytokine inflammatory profiles (mRNA expression and protein secretion) of MDMi from all cohorts were subsequently characterised following exposure to LPS and treatment with the anti-inflammatory drugs minocycline and IC14 (Fig. 2A).

Study design and drug efficacy analysis in the study cohorts. (A) MDMi from three cohorts of individuals (healthy control, HC; mild cognitive impairment, MCI; and Alzheimer’s disease, AD) were generated in 2D and 3D models. Following induction of inflammation with LPS, the cytokine profiles of MDMi in response to drugs (i.e., minocycline 1 μM and IC14 0.05 ng/mL) were characterised at the mRNA expression and protein secretion levels. These profiles were then compared between individuals using multidimensional analyses. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) plots showing the clustering of cohort-specific MDMi cytokine profiles in untreated (baseline), after LPS alone (LPS) or after LPS with drugs (minocycline, IC14, or isotype control) treatments. (C) Cytokine responses (mRNA includes n = 7 cytokines; and secretion includes n = 12 cytokines) to minocycline and IC14 separated by cohort. Values were calculated as fold change to LPS (for minocycline) or LPS with isotype (for IC14), represented with dotted lines. Responses above and below the fold change indicate pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effect, respectively. One-sample t-test performed on log-transformed data in C; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (red arrows). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and include 6 donors (n = 6) in HC, 3 donors (n = 3) in MCI; and 3 donors (n = 3) in AD.

Minocycline and IC14 working concentrations (1 μM and 0.05 ng/mL, respectively) were optimised using MDMi from young HC donors (< 50 years old) (Table 1) by testing the effects of a range of doses on cell viability, toxicity, and modulation of LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine expression (Fig. S2). We used IgG4 as an isotype control to ensure that the effects observed with IC14 were specific. To confirm that MDMi responded to treatments with LPS and drugs, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) and observed a clear separation of MDMi cytokine profiles between baseline (untreated) and post-LPS or drug treatment conditions (Fig. 2B). We next assessed the efficacy of minocycline and IC14 in reducing LPS-induced inflammation by averaging MDMi cytokine responses in each cohort (Fig. 2C). We observed limited cytokine reduction, likely caused by the high inter-patient variability within the cohorts (Fig. 2C, Fig. S3, Fig. S4). Such heterogeneity may mask the presence of selective responders. Moreover, we observed that drug responses were not consistent between 2D and 3D models despite being established from the same pool of monocytes. This shows the strong dependence of MDMi physiology on extracellular cues.

Together, our results show that a cohort-based analysis provides a low-resolution representation for testing drug responses in vitro and comparing individuals with different disease status, thereby hampering the utility of MDMi models to identify and stratify responders.

Donor-specific multidimensional analysis of cytokine profiles in 3D MDMi reveals segregation between healthy individuals and dementia patients

We next compared individual cytokine profiles (measured as mRNA expression or protein secretion) at baseline and post-drug treatment by using multidimensional analysis. As expected, we found that baseline cytokine levels were consistently lower in both 2D and 3D models as compared to treatment conditions (with LPS or LPS and drugs) (Fig. S5). Notably, hierarchical clustering and PCA of baseline cytokine profiles revealed a more distinct separation between healthy and patient cohorts in 3D than in 2D (Fig. 3A). This would suggest that cytokine profiles in 3D models might have a greater predictive power for selecting individuals prior to drug evaluation. Individual cytokine profiling following treatment with minocycline showed trends towards separate clustering between patient and heathy individual profiles only in 3D (Fig. 3B). Such clustering was not evident when MDMi were treated with IC14 (Fig. 3C), indicating that cytokine profiles are drug-specific. A Kruskal–Wallis test identified TGF-β and IL-18 mRNA expression in 3D models for minocycline and IC14, respectively, as the most significant (P < 0.05) drug responses differentiating cohorts (Table S1, Fig. S6). Other notable differential responses (0.05 < P < 0.1) included IL-12p70 secretion (2D, minocycline), IFN-γ and IL-18 (2D, IC14), and IL-6 mRNA expression (3D, minocycline) (Fig. S6).

Separation of individual cytokine profiles based on disease status in 2D and 3D models. Heatmaps of cytokine responses (mRNA and secretion) in HC, MCI and AD individuals with hierarchical clustering of donor profiles (n = 12) and cytokine responses (total n = 19, which includes n = 12 cytokines for secretion analyses and n = 7 cytokines for mRNA analyses) at (A) baseline, and following treatment with (B) minocycline and (C) IC14 in 2D and 3D models. Heatmap values were normalised to LPS (minocycline) or LPS with isotype (IC14), log-transformed and scaled. PCA analyses, presented as plots below each heatmap, included all normalised cytokine response values (n = 19) from each donor. Black circles in A and B include individuals with similar profiles.

Overall, our analyses demonstrate a better ability of the 3D model to distinguish cytokine profiles between healthy individuals and dementia patients at the in vitro level. Indeed, this segregation is more evident by modulating cytokine responses with minocycline. Hence, we conclude that the 3D model reflects differences between disease status better than 2D.

The 3D model reveals higher drug responsiveness in MCI compared to AD patients

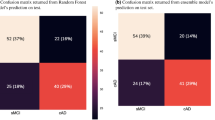

Given the more informative capacity of the 3D model to distinguish between cytokine profiles of healthy controls and patients, we next sought to compare the potential drug responders defined by both 2D and 3D models for subsequent clinical trials. To this end, we ranked the means of the cytokine responses to drugs from each individual in the cohorts by combining both mRNA expression and secretion readouts (Fig. 4A, B). Top-ranked responders were those that showed a minimum 20% cytokine reduction compared to LPS or LPS and isotype control (Fig. 4A, B; Supplementary datasets 1 and 2). This 20% cut-off was chosen based on the results of a randomised controlled trial that showed an average 20% reduction of IFN-γ and IL-10 plasma levels in depression patients following treatment with minocycline for 4 weeks21.

Ranking of individual drug responses from 2D and 3D models. (A, B) HC, MCI and AD individuals ranked based on minocycline- or IC14-mediated reduction of their cytokine profiles compared to LPS stimulation (horizontal black line). Data were normalised to LPS or LPS with isotype, log-transformed (log2) and presented as mean ± SD. Individuals showing at least a 20% reduction of inflammation (horizontal red line) are framed (i.e., top-ranked individuals). (C, D) Cytokine responses (n = 38, which includes specific cytokine readouts [mRNA (n = 7 cytokines) or secretion (n = 12 cytokines) for 2D (n = 19 cytokines including both readouts) or 3D (n = 19 cytokines including both readouts) model systems] ranked based on mean reduction compared to LPS stimulation (black vertical line). Data were normalised to LPS or LPS with isotype, log-transformed (log2) and presented as mean ± SD. Mean responses that show at least a 20% inflammatory reduction (red vertical line) are framed (i.e., top-ranked responses).

Top-ranked responders differed between model systems for both drugs, with AD patient responders being selected by the 2D model only (Fig. 4A, B). In contrast, the 3D model revealed two candidate responders in the MCI cohort for minocycline (Fig. 4A), with the rest of top responders being healthy controls for both minocycline and IC14 (Fig. 4A, B). By stratifying individual drug responses based on cytokine readout, we observed that the drug-mediated reduction in the top responders selected by the 3D model came from both mRNA and secretion readouts (i.e., MCI_1 and MCI_2 for minocycline; HC_2 and HC_3 for IC14) (Fig. S7).

We next aimed to compare the most informative cytokine responses of drug efficacy between MCI and AD cohorts. Our ranking analysis showed a broader spectrum of cytokine responses exhibiting at least a 20% reduction of LPS-induced inflammation in MCI compared to AD (Fig. 4C, D; Supplementary datasets 3 and 4). Of note, the number of top-ranked cytokines in the HC cohort was similar to MCI (Fig. S8; Supplementary datasets 3 and 4). This suggests that AD patients have a limited responsiveness to minocycline and IC14, and points towards potential candidate cytokine readouts with informative power to estimate drug efficacy in vitro based on disease status.

Lastly, we performed correlation analyses to determine if the drug responses we have described were correlated with known risk factors for AD. We did not observe any significant correlation with age, APOE genotype, and brain amyloid-β burden (Fig. S9, S10, S11), likely due to the low sample size of our cohorts. Therefore, further research is warranted to confirm potential correlations between in vitro drug responses with disease risk factors or other patient clinical features.

Discussion

The lack of success in developing effective therapeutics for AD and other neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases highlights the need for more robust drug development approaches. The genetic and biological heterogeneity among patients results in diverse pathophysiological profiles that can be effectively addressed through precision medicine strategies. Therefore, implementing precision drug development approaches may enhance the success of new therapeutics for neurodegeneration22. Due to the lack of effective biomarkers of disease progression in neurodegenerative patients, it is challenging to trial new candidate compounds on the right patients. A patient-specific in vitro model that reflects the disease status of the patient at a particular point in time could be highly beneficial to pre-test candidate compounds and determine the responsiveness of the patient for improved outcomes in clinical trials. Moreover, such a model would be beneficial to predict the progression to advanced disease stages by identifying key biomarkers or molecular pathways at the cellular level.

With this pilot study, we sought to maximise the unique characteristics of 2D and 3D monocyte-derived microglia (MDMi) as patient-specific in vitro cell models that capture disease features7 and are generated with peripheral cells that have been exposed to disease-related plasma biomarkers. Using MDMi derived from dementia patients (MCI and AD), we hypothesised that in vitro drug response profiling using the right patient-derived cellular model can distinguish between patients at different disease stages and identify potential responders for subsequent clinical testing. Indeed, our results showed that the 3D MDMi model separates AD patient cytokine profiles from those of matched healthy individuals and identifies differential drug efficacy between dementia patients with milder (MCI) and more severe (AD) symptoms. The absence of samples from other neurodegenerative diseases currently limits the ability to conclusively establish the specificity of this pipeline for AD. However, the pipeline suggests broad applicability for improving clinical translation in other neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases. Future studies incorporating a wider range of these disorders are essential to validate and strengthen our findings.

While our study provides valuable insights into leveraging in vitro studies to promote personalised strategies in the AD preclinical research landscape, several limitations should be considered. The development of our pipeline, based on small sample sizes in the MCI and AD cohorts (n = 3 patients per cohort), reduces statistical power and compromises the robustness of our conclusions. This constraint may impact the translatability of our findings to larger cohorts. In addition, relying on inflammatory stimuli with low physiological relevance like LPS may not fully capture the multifaceted neuroinflammatory aspects of AD. Therefore, we highlight the need for larger, more genetically diverse cohorts and the examination of alternative stimuli, such as tau and amyloid-β, which are more directly related to AD pathology. Additionally, by using MDMi mono-culture models and therefore focusing solely on microglia, our study overlooks interactions with other CNS cell types, such as astrocytes and neurons, which play pivotal roles in neuroinflammation. The exclusion of these cell types might oversimplify the complex cellular crosstalk occurring in the brain during AD pathology.

Despite these limitations, our study opens avenues for new lines of investigation to design new drug and biomarker discovery approaches for AD. Our limited understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving AD onset and progression has challenged the identification of biomarker tools with robust predictive power23. To address this shortcoming, the inflammatory profiles of MDMi from patients with various disease severities and high-risk, asymptomatic individuals could inform improved diagnosis strategies and guide the implementation of personalised prevention trials or therapeutic interventions at early disease stages. In our study, healthy control individuals had low non-APOE-associated genetic risk and were negative for brain amyloid-β deposition. A comparison of cytokine profiles between these low-risk individuals and another healthy cohort with increased genetic risk and positive for brain amyloid-β deposition could be valuable.

Besides the potential to discriminate asymptomatic individuals with different risk levels, our pipeline may also predict disease progression in patients with mild symptoms. We observed that the cytokine profiles of certain individuals clustered more closely with individuals from other cohorts than their own. Although this could be attributed to high inter-individual variability, further investigation with larger cohorts (at least 20 individuals per cohort) is needed to determine if inter-cohort similarities reflect the conversion of healthy controls to patients or the progression from mild to more severe disease stages. Elucidating this aspect would be crucial to define the predictive ability of our pipeline and could provide better preclinical approaches to monitor disease onset and progression.

To conclude, we present a pilot in vitro pipeline using AD patient-specific cells that shows potential to enhance patient stratification and responder selection in preclinical studies and paves the way for investigating new prediction strategies of disease onset and progression.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Knopman, D. S., Jones, D. T. & Greicius, M. D. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimers Dement. 17(4), 696–701 (2021).

Dujardin, S. et al. Tau molecular diversity contributes to clinical heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 26(8), 1256–1263 (2020).

Dubois, B. et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol. 20(6), 484–496 (2021).

Temp, A. G. M. et al. A Bayesian perspective on Biogen’s aducanumab trial. Alzheimers Dement. 18(11), 2341–2351 (2022).

Shineman, D. W. et al. Accelerating drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease: Best practices for preclinical animal studies. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 3(5), 28 (2011).

Quek, H. et al. A robust approach to differentiate human monocyte-derived microglia from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. STAR Protoc. 3(4), 101747 (2022).

Cuní-López, C. et al. Advanced patient-specific microglia cell models for pre-clinical studies in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 21(1), 50 (2024).

Cuní-López, C., Stewart, R., Quek, H. & White, A. R. Recent advances in microglia modelling to address translational outcomes in neurodegenerative diseases. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11101662 (2022).

Cuní-López, C., Stewart, R., White, A. R. & Quek, H. 3D in vitro modelling of human patient microglia: A focus on clinical translation and drug development in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neuroimmunol. 375, 578017 (2023).

Quek, H. & White, A. R. Patient-specific monocyte-derived microglia as a screening tool for neurodegenerative diseases. Neural. Regen. Res. 18(5), 955–958 (2023).

Quek, H. et al. ALS monocyte-derived microglia-like cells reveal cytoplasmic TDP-43 accumulation, DNA damage, and cell-specific impairment of phagocytosis associated with disease progression. J. Neuroinflammation. 19(1), 58 (2022).

Sellgren, C. M. et al. Increased synapse elimination by microglia in schizophrenia patient-derived models of synaptic pruning. Nat. Neurosci. 22(3), 374–385 (2019).

Rocha, N. P. et al. Microglia activation in basal ganglia is a late event in huntington disease pathophysiology. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000984 (2021).

Scholz, R. et al. Minocycline counter-regulates pro-inflammatory microglia responses in the retina and protects from degeneration. J. neuroinflammation. 12(1), 1–14 (2015).

Scott, G. et al. Minocycline reduces chronic microglial activation after brain trauma but increases neurodegeneration. Brain. 141(2), 459–471 (2018).

Howard, R. et al. Minocycline at 2 different dosages vs placebo for patients with mild alzheimer disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 77(2), 164–174 (2020).

Gelevski, D. et al. Safety and activity of anti-CD14 antibody IC14 (atibuclimab) in ALS: Experience with expanded access protocol. Muscle Nerve https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.27775 (2022).

Henderson, R. D. et al. Phase 1b dose-escalation, safety, and pharmacokinetic study of IC14, a monoclonal antibody against CD14, for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Medicine https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027421 (2021).

I-SPY COVID Consortium. Report of the first seven agents in the I-SPY COVID trial: A phase 2, open label, adaptive platform randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 58, 101889 (2023).

Lupton, M. K. et al. A prospective cohort study of prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: Prospective Imaging Study of Ageing: Genes, Brain and Behaviour (PISA). NeuroImage: Clinical. 29, 102527 (2021).

Nettis, M. A. et al. Augmentation therapy with minocycline in treatment-resistant depression patients with low-grade peripheral inflammation: Results from a double-blind randomised clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 46(5), 939–948 (2021).

Cummings, J., Feldman, H. H. & Scheltens, P. The, “rights” of precision drug development for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 11(1), 76 (2019).

Li, T. R., Yang, Q., Hu, X. & Han, Y. Biomarkers and tools for predicting Alzheimer’s disease in the preclinical stage. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 20(4), 713–737 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Gunter Hartel for his invaluable advice on data analysis. We acknowledge Sun Yifan Emily and Natalie Garden for their assistance with donor blood collection, and the coordinators of the PISA study Professor Michael Breakspear, A/Professor Michelle Lupton, Dr Christine Guo, Jessica Adsett and Madeline Wood. We appreciate the generosity of the QIMRB volunteers and PISA study participants, who have kindly donated blood to this project. We also thank the QIMRB Scientific Services and Sample Processing teams for their support with experimental procedures and collection of samples.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia(NHMRC) (APP1125796), a National Foundation for Medical Research and Innovation (NFMRI) grant, and a US Dept Defense CDMRP ALS grant (W81XWH-22–1-0714) to A.R.W. A.R.W. was supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1118452), and H.Q. was supported by an NHMRC Ideas grant (APP2029183).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C-L., R.S., A.R.W. and H.Q. conceived and designed the study. C.C-L. and H.Q. performed experiments and interpreted data. S.O. performed donor-specific analyses and correlations. G.L.R. and M.W.A. kindly provided IC14. C.C-L. wrote the manuscript and made figures. R.S., A.R.W. and H.Q. interpreted data and provided critical feedback in reviewing and editing. All authors reviewed and commented on the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.L.R. and M.W.A. are employed by Implicit Bioscience. The compound IC14 was received as a gift from Implicit Bioscience for testing purposes. A.R.W. and H.Q. are listed as co-authors on provisional patent PCT/AU2020/050513, titled "Microglial Cells and Methods of Use Thereof," filed with the Council of Queensland Institute of Medical Research. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cuní-López, C., Stewart, R., Okano, S. et al. Exploring a patient-specific in vitro pipeline for stratification and drug response prediction of microglia-based therapeutics. Sci Rep 15, 8296 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92593-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92593-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Modelling sex differences of neurological disorders in vitro

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2025)