Abstract

Persistent lower levels of adiponectin are associated with hyperandrogenism, predisposing PCOS women to NAFLD. This study elucidated the therapeutic potential of a small molecule adiponectin receptor agonist-AdipoRon, utilizing an in-vivo PCOS rat model mimicking the manifestation of PCOS along with hepatosteatosis. Our study demonstrated that Adiporon reduced lipid accumulation in PCOS-associated NAFLD by alleviating insulin resistance & lipogenesis. AdipoRon also reversed hyperandrogenism and adiponectin deficiency in PCOS animals. In addition, AdipoRon was found to restore altered PCOS-induced hepatic circadian gene expression (Bmal1, Clock, Per3, Cry2, Reverba, and Rora). Interestingly, at the epigenetic level, global transcription activation marks, i.e., H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, and H3K36me2, were upregulated in disease conditions. Furthermore, our ChIP data confirmed that circadian genes Bmal1, Reverba, And Rora are epigenetically regulated. ChIP assay data showed an increased H3K36 dimethylation at the Bmal1 and Rora promoter, whereas a significant decrease was observed at the Reverbα promoter in PCOS-associated NAFLD. AdipoRon ameliorated these PCOS-induced epigenetic alterations, modulating the hepatic circadian gene expression. We present the preliminary evidence illustrating the epigenetic modulation of AdipoRon, thereby regulating hepatic circadian gene expression. This study provides insights regarding the therapeutic potential of AdipoRon in PCOS-associated NAFLD, which can be of profound clinical significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, a unique gynecological condition, is the most prevailing endocrinopathy affecting 6–25% of premenopausal women, leading to anovulatory infertility in ∼90–95% of PCOS women1,2. The heterogeneous nature of the syndrome is contributed by hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPOA) dysfunctioning leading to amalgams of symptoms like (i) androgen excess (free androgen score & presence of hirsutism and/or acne), (ii) polycystic ovarian morphology (presence of functional cyst) & (iii) ovarian dysfunctioning (anovulation/oligo-ovulation)3. Obesity, insulin resistance, and compensatory hyperinsulinemia have been extensively reported to have a substantial impact on the induction & progression of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), in addition to its reproductive manifestations. Although 50% of women with PCOS are obese or overweight, this association is not ubiquitous. Lean and obese PCOS women, in contrast, have a high visceral adiposity index in comparison to controls of the same age and BMI. Obesity and insulin resistance with persistent hyperandrogenism in a vicious cycle contribute to aggravating metabolic and reproductive disruptions4,5,6. A plethora of evidence suggests that PCOS is a multi-componential reproductive metabolic abnormality with various comorbidities such as type II diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular ailments, etc7.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic liver disease defined as the accumulation of fatty acid content greater than 5% of liver weight. It is prevalent in the Western world, with a global occurrence of 32.4%8. It is found to be more prevalent among males ∼40%) than females ∼26%9. NAFLD encompasses a spectrum, ranging from the benign non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to the more severe non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and a lethal stage of cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma10. Prior research has established a predisposition to NAFLD as linked with a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, type II diabetes, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia11. These factors align with the underlying causes of PCOS. Prominent pathological traits associated with PCOS include hyperandrogenism, obesity, and insulin resistance12,13. Recent data suggests a substantial correlation between these risk factors and NAFLD, thereby explaining the high prevalence of NAFLD (43%) in PCOS women14. It has been shown that PCOS women (Phenotype 1) with hyperandrogenism have a higher likelihood of NAFLD in comparison to PCOS women (Phenotype 4) without hyperandrogenism15. Hence, the presence of persistent hyperandrogenism in individuals with PCOS renders them more susceptible to NAFLD13,16.

Obesity and enduring hyperandrogenism have been observed to elicit alterations in the levels of several adipokines, such as leptin, adiponectin, resistin, etc17. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived hormone, has been proven to elicit a positive effect on insulin sensitivity & prevent lipid accumulation, hence maintaining metabolic integrity18. Low adiponectin levels have been reported in both PCOS as well as NAFLD etiology, becoming the chief culprit to metabolic derangements associated with these conditions19,20. It has been reported that adiponectin ameliorates aberrant androgen synthesis and improves insulin resistance in PCOS mice ovary21.

Circadian clocks entrain the daily bodily rhythm by transmitting signals from the master circadian pacemaker, i.e., the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), to the peripheral cell clock in the specific tissue. The endogenously synchronized circadian clock facilitates the synchronization of human biology and behavior with the diurnal environmental variations pertaining to the 24-hour day-night cycle. The circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK) and brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1 (BMAL1) forms heterodimers that bind with cis-acting E-box elements, facilitating the transcriptional activation of cryptochrome (Cry) and period (Per) genes. Following this, CRY and PER proteins re-localize to the nucleus and inhibit their transcription, establishing a transcription-translation feedback cycle. There is an intricate interplay reported between RORα and REV-ERBα through interactions with RRE, a shared DNA response element on the Bmal1promoter region, which plays a crucial role in modulating the expression of BMAL1, thereby establishing a feedback loop that ensures the timely expression of BMAL122. Circadian derangement, a typical characteristic of jet lag and shift work, is implicated in type II diabetes & obesity in humans and leads to metabolic abnormalities23,24. Recent evidence indicates that critical PCOS traits are associated with mutations of the core circadian clock genes25. Furthermore, hyperandrogenism, the main culprit underlying the etiology of PCOS, has been observed to perturb the circadian rhythm in female rats26. Hyperandrogenism modulates liver metabolism & alters the levels of genes involved in lipid metabolism, leading to steatosis in NAFLD. Roy et al. provided first-hand evidence that the hormonal disbalance, which is the primary inducer of PCOS, leads to upregulation in the levels of the Bmal1gene by altering the gene silencing marker, i.e., H3K27me3 by regulating the level of EZH2 & JMJD3. This hepatic clock disruption leads to the derangement of hepatic gene expression, and its implications on liver metabolism cannot be discounted27.

AdipoRon, a synthetic analog of endogenous of an antidiabetic and antiatherogenic adipokine i.e., adiponectin, mimicking its stimulation of AdipoR1(Kd: 1.8µM; Rmax:14.6RU) and AdipoR2(Kd: 3.1µM; Rmax:8.6RU) receptors, respectively, leading to subsequent activation of AMPK and PPAR. The anti-diabetic effects afforded by AdipoRon (50 mg/kg) in invivo studies exhibited a Cmax of 11µM. The stimulation of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 receptors by AdipoRon is affected by the serum concentration of adiponectin, where a therapeutic effect is observed at submaximal adiponectin concentration (15 µg/ml), whereas no effect is observed at maximal adiponectin concentration (50 µg/ml). In addition to improving metabolic dysfunction, AdipoRon has well-proven anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and life span-prolonging properties. Over the years, AdipoRon, the first orally active molecule, has gained widespread attention as a therapeutic approach for several diseases, such as obesity, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders28.

Based on prior literature, it is well established that hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance, associated with PCOS, play a contributory role in hepatosteatosis development and progression29. Taking this evidence forward, dehydroepiandrosterone (6 mg/100 g body weight) and high-fat diet-induced PCOS, a model mimicking all the clinical manifestations of PCOS, was selected to demonstrate the potential therapeutic effects of AdipoRon. AdipoRon helped mitigate insulin resistance via activation of the AMPK-Akt-GSK3β pathway. Our research comfirmed that AdipoRon ameliorated overactivated lipogenic protein and gene expression, thereby attenuating NAFLD progression. In addition, AdipoRon modulated the altered peripheral circadian gene expression in the liver, leading to therapeutic benefits in PCOS-induced NAFLD. These circadian modulatory effects of AdipoRon can either be attributed to the ablation of hyperandrogenism or vice versa. Taken together, our findings could further elucidate the role of circadian irregularities in developing PCOS-associated NAFLD and provide an intriguing pharmacological treatment option for PCOS-associated NAFLD.

Results

DHEA & HFD administration induced reproductive abnormalities mimicking PCOS phenotype

On completion of 5 weeks of DHEA and HFD administration, the PCOS animals demonstrated estrous irregularities experiencing arrest in the diestrous phase in comparison to the maintenance of regular estrous cyclicity in the control group (Fig. 1A-B), as observed in the respective representative micrographs of vaginal smears shown in Fig. 1E-F. Further confirmation of successful PCOS induction was provided by a significant increase in the ovarian size and weight of PCOS animals (Fig. 1C, G-H) as well as by the presence of follicular cysts in PCOS animals in comparison to the control group (Fig. 1D). In addition, a significant increment in the levels of serum testosterone (T) (p < 0.001) and luteinizing hormone (LH) (p < 0.001) was observed in PCOS animals arrested at diestrous phase whereas a significant reduction was observed in estradiol (E2) (p < 0.001) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (p < 0.001) levels (Fig. 1I-L), which are characteristic features to PCOS development. This hormonal alteration led to a significant elevation in the LH/FSH ratio (p < 0.001), signifying the induction of reproductive aberrations (Fig. 1M).

Induction of PCOS. (A) Pictorial representation of study design designed using biorender (B) Pictorial representation of various estrous stages (scale bar = 100 μm), (C) Phenotypic changes after PCOS induction, (D) Ovarian sections stained with H&E showing cyst formation (C: Cyst), (E & F) Representative micrographs of estrous cyclicity patterns, (G) ovary size, (H) ovary weight, serum sex hormone profile evaluations at estrous phase of control group and diestrous phase of PCOS group, (I) testosterone (T), (J) estradiol (E2), (K) luteinizing hormone (LH), (L) follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), (M) LH/FSH ratio. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed in (G-M). Data are presented as mean ± SD, (n = 5); **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. Control group.

PCOS condition predisposes animals to NAFLD by metabolic profiles and histological alterations

The PCOS induction led to a significant increase (p < 0.001) in body weight compared to normal control animals (Fig. 2A). Metabolic dysfunction associated with PCOS leads to subsequent induction of NAFLD, as reported in the previous literature12. First, evidence of metabolic dysfunction in PCOS animals was provided by significantly upregulated plasma glucose (p < 0.001) and lipid parameters, i.e., triglycerides (p < 0.001), cholesterol (p < 0.001), and LDL-cholesterol levels (p < 0.001). In contrast, contrasting effects were observed in HDL-cholesterol levels (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B-F). Furthermore, glucose intolerance induction was validated by substantially elevated AUC (p < 0.001) for PCOS animals compared to control animals interpolated from IPGTT data (Fig. 2G-H). In addition, hyperinsulinemia exhibited by PCOS animals was confirmed using ELISA. Consequently, the HOMA-IR index was observed to be significantly augmented (p < 0.001) in PCOS compared to control animals (Fig. 2I-J). Furthermore, the levels of serum ALT, AST, and ALP were found to be significantly elevated (p < 0.001; p < 0.001; p < 0.001) in PCOS animals, indicating disruption of liver functioning (Fig. 2K-M). The relative liver weight exhibited a drastic increase (p < 0.01) in PCOS animals, thereby augmenting liver index (%), further confirming the induction of liver abnormalities in PCOS animals (Fig. 2N). The serum adiponectin levels were estimated to be significantly downregulated (p < 0.01) in PCOS animals as compared to control animals (Fig. 2O). The hepatic adiponectin protein expression and mRNA levels of the PCOS group were also significantly attenuated (p < 0.001) in PCOS animals (Fig. 2P-R). Hepatic histological aberrations in PCOS animals were confirmed by the presence of lipid droplets quantified as ballooning area (%), which were validated using hematoxylin and eosin staining and oil red o staining. In addition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis further confirmed the development of fatty liver, thus indicating a predisposition of PCOS animals to NAFLD (Fig. 2S-W).

PCOS induces NAFLD-like biochemical and histological alterations. The figure shows changes in (A) body weight after PCOS induction, biochemical profile of fasted animals (A) plasma glucose, (C) triglycerides, (D) total cholesterol, (E) LDL-cholesterol, (F) HDL-cholesterol, (G) IPGTT, (H) AUC of IPGTT, (I) serum insulin, (J) HOMA-IR, (K) ALT, (L) AST, (M) ALP, (N) liver index (%), (O) serum adiponectin, (P) immunoblots of liver adiponectin and actin (n = 3), (Q) densitometric analysis of adiponectin immunoblot normalized to actin, (R) mRNA expression of adiponectin in the liver normalized to actin, (S) gross morphology of control and PCOS liver, (T) representative photomicrographs of H&E stained liver sections (U) representative photomicrographs of oil red O stained sections of liver and (V) representative photomicrographs of transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) of liver sections; black arrows indicate the hepatocellular ballooning or lipid droplets; (W) Ballooning area (%). Two-way ANOVA plus Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed in (A), and unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed in (B-F), (H-O), and (Q-R-W). All blots were cut prior to hybridization. Data are presented as mean ± S.D; (n = 5); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001, (*) vs. Control group.

AdipoRon improved the body weight and metabolic and histological aberrations in PCOS-induced NAFLD animals

Treatment with AdipoRon for six weeks showed a significant improvement (p < 0.001) in body weight (Fig. 3A). AdipoRon also afforded therapeutic benefits to the disrupted metabolic profile. A significant reduction was observed in the plasma glucose (p < 0.001) levels as well as lipid parameters such as triglyceride, cholesterol, and LDL-C (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B-E). A significant elevation of HDL (p < 0.001) was observed in the AdipoRon-treated group (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, AdipoRon also alleviated glucose intolerance demonstrated by IPGTT, and corroboration was provided by the significance observed in the AUC plot (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3G-H). Restoration of insulin sensitivity by AdipoRon was confirmed using insulin ELISA, which showed a significant reduction of insulin levels (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3I). The HOMA-IR index was also substantially improved (p < 0.001) by AdipoRon treatment, pointing toward a reduction of insulin resistance in PCOS animals (Fig. 3J). The levels of liver enzymes, i.e., serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), were also significantly downregulated (p < 0.001; p < 0.001; p < 0.01) by AdipoRon, indicating improved liver functioning (Fig. 3K-M). There was a significant reduction in liver index (%) and liver triglyceride level (p < 0.05 ; p < 0.001) in the treated group as compared to the PCOS group (Fig. 3N-O). In addition, there was a significant improvement (p < 0.001) in the WAT weight and adiposity index shown in AdipoRon-treated animals (Fig. 3P-Q). In line with previous observations, the serum adiponectin level was also elevated by AdipoRon, consistent with its upregulation at mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3R-U). The hyperandrogenism associated with PCOS was also ameliorated by AdipoRon (Fig. 3V), which plays a crucial role in linking both disease etiologies29. PCOS-induced steatohepatitis and hepatic sinusoidal dilatation, characteristic traits of NAFLD, were ameliorated by AdipoRon, which was confirmed by reduced ballooning area (%) and lipid droplets number in PCOS animal liver tissue (Fig. 3W-AB).

Adiporon improved bodyweight, metabolic alterations, and liver histopathological features of PCOS-induced NAFLD animals. The figure shows changes in (A) bodyweight, biochemical profile of fasted animals, (B) plasma glucose, (C) triglycerides, (D) total cholesterol, (E) LDL-cholesterol, (F) HDL-cholesterol, (G) IPGTT, (H) AUC of IPGTT, (I) serum insulin, (J) HOMA-IR, (K) ALT, (L) AST, (M) ALP, (N) liver index (%), (O) liver triglycerides, (P) WAT weight, (Q) Adiposity index, (R) serum adiponectin, (S) immunoblot of liver adiponectin and actin (n = 3), (T) densitometric analysis of adiponectin immunoblot normalized to actin, (U) mRNA expression of adiponectin in the liver normalized to actin (n = 3), (V) testosterone (T) levels, (W) gross morphology of livers of control, PCOS and AdipoRon treated animals, (X) representative photomicrographs of H&E stained liver sections, (Y) representative photomicrographs of oil red O stained liver section, (Z) representative photomicrographs of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of liver section, (AA) Balloning area (%) and (AB) no. of lipid droplets; black arrows indicate the hepatocellular ballooning or lipid droplets. Two-way ANOVA plus Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed in (A), and one-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed in (B-F), (H-R), (T-V), and (AA-AB). All blots were cut prior to hybridization. Data are presented as mean ± SD; (n = 5); *or#p < 0.05, **or##p < 0.01 and ***or###p < 0.001, (*) vs. Control group and (#) vs. PCOS group.

AdipoRon ameliorates aberration in insulin signaling and hepatic de Novo lipogenesis in PCOS-induced NAFLD rats

The biochemical and histological improvement by AdipoRon in NAFLD rats led us to elicit the role of the insulin signaling pathway and the role of AdipoRon in improving disease conditions. Immunoblotting was performed to examine the alteration in the levels of proteins comprising the insulin signaling cascade. We observed that insulin signaling was compromised in DHEA + HFD-fed rats, indicated by reduced AMPK/AKT/GSK3β pathway activation. The expression of pAMPK (Thr172), pAKT (Ser473), and pGSK3β (Ser9) was significantly reduced (p < 0.01; p < 0.01; p < 0.001), in PCOS animals in comparison to control animals. AdipoRon treatment significantly elevated AMPK phosphorylation (p < 0.01), which further considerably augmented the phosphorylation of AKT (p < 0.01). The activated AKT then significantly downregulated the GSK3β (inactive) expression (p < 0.01) via phosphorylation (Fig. 4A-D). The inactivation of GSK3β leads to subsequent activation of glycogen synthase, which stimulates glycogenesis and improves glucose sensitivity30. It has been reported that hyperandrogenism associated with PCOS leads to the disruption of lipid homeostatic balance between lipogenesis & lipid oxidation, causing increased hepatic retention of lipids, subsequently leading to the development of NAFLD31. Western blot analysis shows significant upregulation of lipogenic proteins, such as ACC (p < 0.01), FASN (p < 0.01), and FABP4 (p < 0.001), was observed in liver tissue isolated from PCOS animals (Fig. 4E). The hepatic mRNA levels of lipogenesis-promoting transcription factors, including Foxo1, Chrebp, Fasn, and Srebp1c, were significantly augmented (p < 0.01; p < 0.001; p < 0.01; p < 0.001) in liver samples of PCOS animals. Administration of AdipoRon leads to a significant decrease in lipogenic protein expression (ACC, FASN, and FABP4) as well as the mRNA levels of lipogenic transcription proteins (Fasn, Chrebp, Fasn, and Srebp1c), thereby inhibiting the over-activation of de novo lipogenesis, consequently reducing NAFLD development and progression in PCOS animals (Fig. 4F-L).

AdipoRon improves hepatic insulin signaling and reduces de novo lipogenesis in PCOS-induced NAFLD. The figure shows (A) immunoblots of pGSK3β, tGSK3β, pAKT, tAKT, pAMPK and β-actin, (B) densitometric analysis of pAMPK normalized to tAMPK, (C) densitometric analysis of pAKT normalized to tAKT, (D) densitometric analysis of pGSK3β normalized to tGSK3β, (E) immunoblots of ACC, FASN, FABP4 and β-actin, (F) densitometric analysis of ACC normalized to β-actin, (G) densitometric analysis of FASN normalized to β-actin, (H) densitometric analysis of FABP4 normalized to β-actin, (I-L) mRNA expression of Foxo1, Chrebp, Fasn and Srebp1c normalized to β-actin. One-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed in (B-D) and (F-L). All blots were cut prior to hybridization. Data are presented as mean ± SD; (n = 3); **or##p < 0.01 and ***or###p < 0.001, (*) vs. Control group and (#) vs. PCOS group.

AdipoRon reinstates hepatic clock gene expression in PCOS-associated NAFLD

The hyperandrogenism-induced desynchrony of the circadian clock has a crucial role in PCOS-associated NAFLD pathophysiology27. It was observed through immunoblotting that hyperandrogenism & high levels of free fatty acid levels led to significant overexpression of hepatic core loop proteins, i.e., BMAL1 (p < 0.001), CLOCK (p < 0.01), CRY2 (p < 0.01), and PER3 (p < 0.001), (Fig. 5A-E). The liver tissue sample from PCOS animals also showed contrasting expression of secondary loop proteins, i.e., significantly elevated RORα (p < 0.001) expression & significantly downregulated REVERBα expression (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5F-G). Hepatic mRNA levels of these circadian clock genes (Bmal1, Clock, Cry2, Per3, Reverba, and Rora) were also significantly altered (p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001) in PCOS animals (Fig. 5H-M). AdipoRon ameliorated hepatic circadian alteration in PCOS animals at protein and mRNA level, which may help restore liver metabolic homeostasis as demonstrated by earlier studies32.

AdipoRon restores hepatic clock gene expression in PCOS-induced NAFLD. The figure shows (A) immunoblots of BMAL1, CLOCK, CRY2, PER3, REVerbα, RORα and β-actin, (B) densitometric analysis of BMAL1 normalized to β-actin, (C) densitometric analysis of CLOCK normalized to β-actin, (D) densitometric analysis of CRY2 normalized to β-actin, (E) densitometric analysis of PER3 normalized to β-actin, (F) densitometric analysis of REVerbα normalized to β-actin, (G) densitometric analysis of RORα normalized to β-actin, and (H-M) mRNA levels of Bmal1, Clock, Cry2, Per3, Reverba and Rora normalized to β-actin. One-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed in (B-M). All blots were cut prior to hybridization. Data are presented as mean ± SD; (n = 3); *or#p < 0.05, **or##p < 0.01 and ***or###p < 0.001, (*) vs. Control group and (#) vs. PCOS group.

AdipoRon epigenetically modulates the expression of hepatic circadian genes

Histone modification regulates the conversion of chromatin from a heterochromatin form to a euchromatin form to modulate the expression of various genes without altering the DNA sequence33. Therefore, this prompted us to examine the levels of transcription activation marks, i.e., H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, and H3K36me2. We found their levels were significantly upregulated (p < 0.05; p < 0.001, p < 0.001) in PCOS-associated NAFLD (Fig. 6A-D). To further validate the role of epigenetic modulations, ChIP-qPCR studies were performed using H3K36me2 antibody which showed a significant increase in H3K36me2 enrichment at the promoter of Bmal1 (p < 0.001) and Rora (p < 0.01), and a substantial reduction at Reverba promoter (p < 0.001) in liver tissue of PCOS animals which was restored by treatment with AdipoRon (Fig. 6E-G).

AdipoRon alters hepatic circadian gene expression by modulating histone modification landscape. The figure shows (A) immunoblots of H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, H3K36me2, and H3, densitometric analysis of (B) H3K36me2, (C) H3K9/14ac, (D) H3K4me3 normalized to H3, CHIP-qPCR of H3K36me2 for enrichment on (E) Bmal1, (F) Rora and (G) Reverba promoters. One-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed in (B-G). All blots were cut prior to hybridization. Data are presented as mean ± SD; (n = 3); *or#p < 0.05, **or##p < 0.01 and ***or###p < 0.001, (*) vs. Control group and (#) vs. PCOS group.

Discussion

Women diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased probability of developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)34. Adiponectin deficiency is one of the underlying causative factors linking both etiologies, which is often associated with metabolic dysfunctioning as it orchestrates glucose and lipid metabolism35. The metabolic and reproductive dysfunctions associated with PCOS contribute to aberration in lipid homeostasis, leading to hepatic steatosis, playing a crucial underlying role in the onset of NAFLD in PCOS animals36. Our observation demonstrated that DHEA (60 mg/kg) and high-fat diet exposure could lead to successful induction of NAFLD characteristics features in addition to PCOS characteristics. This induction could be attributed to hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance, the hallmark of the PCOS condition, accompanied by a significantly low level of adiponectin. PCOS-induced animals were found to be obese, insulin-insensitive, and prone to hepatic lipid accumulation. Our data reflected that treatment with AdipoRon, a synthetic analog of adiponectin, led to the improvement of metabolic abberation in PCOS-associated NAFLD, thereby reversing glucose intolerance and insulin-resistant conditions. This metabolic homeostasis reinstating property of AdipoRon can be attributed to AMPK activation and subsequent activation of the downstream AKT/GSK3β pathway. These promising effects of AdipoRon could possibly be credited to its higher binding affinities for AdipoRs (AdipoR1 and AdipoR2).

37.

It is well documented that persistent long androgen excess along with insulin resistance often associated with PCOS could stimulate denovo lipogenesis with subsequent inhibition of lipolysis, causing hepatostetosis29. Our findings resonate with previous research, as significantly elevated levels of serum lipid parameters, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL-C, were observed alongside increased liver TG content, aberrant histomorphological changes such as hepatic macrovesicular steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, and vacuolization and abnormally upregulated lipogenic protein and gene expression which could be attributed to the glucose metabolism dysfunctioning and higher testosterone levels in PCOS animals. This disrupts the equilibrium between fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, which is essential for maintaining lipid homeostasis36. In the present study, hepatic TG levels and hepatocellular ballooning or lipid droplet accumulation were reduced by AdipoRon, together with an improvement in the serum lipid profile. Among lipogenic mediators, transcription regulators such as Srebp1c, Chrebp, and Foxo1, in addition to key enzymes and proteins such as ACC, FASN, and FABP4, were notably reduced by AdipoRon treatment. These results indicate that AdipoRon may potentially modulate the overstimulated expression of de novo lipogenesis-associated proteins in PCOS animals. Moreover, liver dysfunctioning in PCOS animals was ameliorated by AdipoRon, illustrated by reduced serum ALT, AST, and ALP levels. Collectively, our findings demonstrated that AdipoRon administration significantly alleviated hepatosteatosis and restored liver function, thus helping prevent the subsequent development of NAFLD in animals with PCOS.

Recent evidence suggests that chronic hyperandrogenism, associated with PCOS females, impairs hepatic fatty acid breakdown and augments de novo lipogenesis along with upregulated fatty acid uptake, leading to hepatic lipid accumulation. These disruptions of hepatic lipid homeostasis were proven to be attributed to the hepatic circadian system modulations caused by persistent hyperandrogenism27. Numerous investigations have revealed a substantial correlation between the biological clock system and metabolism, pointing towards the role of circadian rhythmicity disruption in the onset of several metabolic abnormalities, such as PCOS, resulting in an aberrant sleep cycle and other clinical manifestations often associated with this disorder35,38. The daily rhythm also possesses control over the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism in the liver. Metabolic anomalies, including NAFLD, have been previously correlated with genetic mutations of hepatic circadian genes39. Certain reports suggest that a disrupted circadian rhythm may be a contributing factor to increased de novo lipogenesis40. Notably, our data suggested that PCOS induction in female rats provided persistent androgen excess, leading to significant upregulation in several hepatic clock control genes, such as Bmal1, Clock, Per3, and Cry2, comprising the primary circadian loop in the liver tissue. In contrast, the genes comprising the secondary loop, i.e., Rora and Reverba, exhibited a contrasting expression pattern, i.e., upregulation of Rorα & downregulation of Reverbα. Interestingly, these alterations of the hepatic circadian system in PCOS animals were ameliorated by AdipoRon.

Posttranslational modifications of histones are imperative for governing gene expression through transcriptional regulation41. It has been previously elucidated that in addition to ARE-mediated regulation, androgen has been proven to alter circadian gene expression through epigenetic modification, i.e., H3K27me3, an inhibitory modification, which serves as a downstream target of androgen action. In DHT-treated liver, reduction of the H3K27me3 mark in the vicinity of BMAL1 was found to be associated with hepatostetosis27. In line with the previous research, we observed the presence of several transcription activation marks, i.e., H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, and H3K36me2, which were found to be elevated in PCOS-associated NAFLD conditions. The augmentation of circadian gene expression was further elucidated via the H3K36me2 enrichment studies at their respective promoters using ChIP-qPCR. The studies revealed that an augmented enrichment of H3K36me2 was found at BMAL1 and RORα promoters. However, an abated enrichment was found at the REVERBα promoter, respectively, in liver samples isolated from PCOS animals. These epigenetic alterations exhibit implications in the disruption of the hepatic clock, and the far-fetching effects of these circadian aberrations on liver metabolism cannot be neglected. Our results demonstrated, epigenetic alteration in the hepatic circadian system of PCOS animals was found to be restored by AdipoRon, providing a mechanistic understanding regarding its therapeutic benefits in PCOS-associated NAFLD (Fig. 7). However, further studies are required to warrant any conclusion as it is still unclear whether these circadian modulatory properties of AdipoRon are direct effect or indirect, resulting from the reduction of hyperandrogenism or via the amelioration of adiponectin-deficit, which is known to exhibit a time-specific effect on liver metabolism and diurnal food intake42.

In summary, our study indicated that AdipoRon ameliorated the hepatosteatosis and liver dysfunction associated with PCOS by epigenetically modulating the hepatic circadian gene expression, regulating the AMPK/AKT/GSK3β pathway, and regulating lipogenic protein expression. These findings suggested that AdipoRon can be a therapeutic option for reversing hepatosteatosis in PCOS patients, preventing its development into a more life-threatening disease such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Animals

Prepubertal twenty-one days female Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were acquired from the Central Animal Facility (CAF) after approval from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education & Research (NIPER), SAS Nagar, India (Approval No. IAEC/21/70 & IAEC/21/65). The habitation conditions were controlled and ambient, ensuring a temperature of 23 ± 2ºC and a humidity level of 50 ± 10%. Food and water were provided without restriction throughout the study. Circadian rhythmicity was also maintained with a 12-h light and 12-h dark cycle. Animals were fed either a regular rodent chow diet (3.8 kcal/g, C 0400, Altromin, Germany) or a high-fat diet (60% kcal fat, D12492, Research Diet, New Brunswick), depending upon the grouping. Upon completion of experimentation, the animals were euthanized via Co2 inhalation for the collection of tissues and serum samples for analysis. All methods were performed in compliance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was conducted in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Experimental design and animal treatment

Prepubertal rats in the disease (PCOS) group were subjected to concurrent administration of high-fat diet al.ong with DHEA (60 mg/kg; sc) in 0.1 ml sesame oil for 35 days43,44, whereas the animals comprising the normal control group were fed a regular chow diet. An arrest in the estrous cycle with an altered hormonal profile indicates successful PCOS induction. Based on several hepatic alterations in PCOS-induced animals, animals were randomly assigned to three groups.

Group 1: Normal Control (Control); n = 5; administered 0.9% w/v normal saline.

Group 2: Disease Control (PCOS); n = 5; administered DHEA (60 mg/kg; sc) + high-fat diet.

Group 3: Treatment (PCOS + AD); n = 5; ZT4; PCOS animals administered treatment with AdipoRon (25 mg/kg: p.o; 0.5% CMC).

On confirmation of PCOS-associated NAFLD induction, treatment with AdipoRon (AD) (SML0998) was commenced. The dose was extrapolated from the mouse dose, which was proven therapeutically beneficial and safe by previous studies28,45,46. The animals were terminally sacrificed at ZT4, maintaining circadian uniformity among groups.

Estrous determination

Vaginal smear examination was conducted in the 6th week (model confirmation) and in the 13th week (end of intervention) following the previously reported protocol47. The vaginal smears were prepared using 0.9% NaCl solution, which was subjected to air drying and fixation using 70% ethanol and finally stained using 0.5% methylene blue solution. Light microscopy was employed to ascertain the estrous phases (Olympus BX51 microscope, Tokyo, Japan).

Bodyweight & biochemical analysis

Bodyweight was analyzed and recorded on a weekly basis. Following overnight fasting, retro-orbital puncturing was conducted for blood collection. Thereafter, the blood was centrifuged at 2500 g for 10 min at 4ºC for separation of the plasma and serum, respectively. The sex hormone profile, specifically the serum levels of testosterone, estradiol, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), was assessed using ELISA kits (Elabscience, USA) as per the instructions of the manufacturer. Additionally, liver enzymes, including serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), were analyzed utilizing the serum samples. The extracted plasma, on the contrary, was subjected to analysis to determine the levels of total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, glucose, and triglyceride using commercially available assays in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines (Accurex Biomedical Pvt. Ltd, India). Insulin and adiponectin levels were determined using an ELISA kit (Elabscience, USA). HOMA-IR was calculated as described48. Spectrophotometric analysis was done using BioTek Synergy LX Multimode Reader (Agilent, US). Liver index (%) was evaluated using the formula, Liver Index (%)= {Liver weight (gm)/Body weight(gm)}*100, whereas adiposity index was calculated using the formula, Adiposity Index= {Total body fat (gm)/Body weight (gm)}*10049,50.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT)

Overnight (16 h) fasted animals were subjected to an IPGTT assessment to evaluate the glucose sensitivity after model induction and on completion of intervention duration following a previously described protocol51. Blood samples were withdrawn at 0 min before administering 20% glucose (2 g/kg; i.p). Subsequently, samples were taken 15, 30, 60, and 120 min post the initial glucose administration. The total area under the curve of the glucose response (AUC) was interpolated from the plot between plasma glucose versus time utilizing GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Histological analysis

Paraffin-embedded ovarian and liver tissues were sliced into 5 μm sections, mounted on Mayer’s albumin-coated slides, followed by overnight drying. Following xylene deparaffinization, these sections were rehydrated using alcohol and water. As per the protocol outlined previously, these rehydrated sections were stained with H&E and mounted using DPX48. OCT (optimal cutting temperature compound, Sigma) embedded liver tissues were frozen at −20°C followed by cryosectioning to 5 μm sections using cryotome (Leica CM 1860, Leica Biosystems). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the sections were fixed using 10% formalin, dipped in isopropanol, and ultimately stained via Oil Red O. Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining, and glycerol gelatin was used as a mountant52. Microscopic evaluation of stained slides was done using OlympusBX51, Japan.

Lipid analysis via transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The previously validated procedure was followed to prepare liver samples for TEM analysis53. Briefly, the processing of liver tissue initiated with fixation using 2.5% phosphate-buffered glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 1 h, followed by post-fixation using 1% osmium tetraoxide for 1 h. Traces of osmium tetraoxide residue were removed by subsequent washing using PBS. These samples were then subjected to dehydration using ethanol followed by propylene oxide treatment and then embedded in epoxy resin (Epoxy Embedding Medium kit, Sigma). The sectioning was performed using a glass knife, and contrast staining was done using 4% uranyl acetate. Immediately after mounting on the copper grid, the sections were analyzed at NIPER, S.A.S Nagar, Punjab, India, utilizing TEM (Model TF-20, FEI).

Western blot analysis

Protein expression was evaluated via immunoblotting, performed as reported53. Briefly, frozen liver tissues were subjected to lysis utilizing NP-40 buffer, followed by resolution of extracted protein samples using 7 to 14% SDS-PAGE. These resolved proteins were then transferred to the PVDF membrane, followed by 3% BSA blocking and overnight incubation with the primary antibodies (1:1000): CLOCK (ABclonal #A7265), BMAL1 (ABclonal #A4714), PER3 (ABclonal #A2219), CRY2 (ABclonal #A17465), RORα (ABclonal #A6971), REV-ERBα (ABclonal #A20452), ACC (CST #3676), FASN (CST #3180), FABP4 (CST #2120), Adiponectin (CST #2789), Acetyl-H3 (Lys9/Lys14) (CST#9677S), H3K4me3 (CST #9751S), H3K36me2 (CST #2901S), Histone H3 (CST #4499S) and β-Actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology # sc-47778). On completion of overnight incubation with the primary antibody, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The visualization of the immunocomplex was done using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and Image Quant 500 (Amersham) was used for capturing immunoblot images for densitometric analysis utilizing ImageJ, NIH.

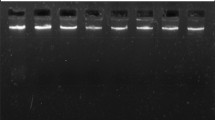

mRNA expression analysis via RT-PCR

For complete RNA extraction, hepatic tissues were treated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, USA). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized using the Verso cDNA kit (AB1453A-Thermo Scientific) as per the instructions provided. Quantification of extracted RNA was performed using NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Brilliant III SYBR Master Mix (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) and gene-specific oligonucleotides were used to detect the relation expression of circadian genes and genes involved in lipogenesis (Table 1). Specific primers were used to amplify actin rRNA, which was then utilized for normalization. The findings were assessed utilizing the 2−∆∆Ct method.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, ChIP-qPCR was performed using a one-step ChIP kit (Cat. # ab117138, Abcam, USA) for analyzing chromatin isolated from liver tissues using a chromatin extraction kit (Cat. # ab117152, Abcam, USA). Briefly, the liver samples were minced, followed by cross-linking with neutral buffered formalin and then homogenization using lysis buffer. The centrifugation of homogenate provided the nuclear pellet, which was processed further using a chromatin extraction buffer. Sonication of isolated chromatin was conducted for chromatin fragmentation using BioRuptor (Diagenode) for ten cycles of 10 s each, maintaining a 15-sec interval between each cycle. For input control, 10% of the fragmented chromatin was used, whereas, for immunoprecipitation, the residual portion was incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-H3K36me2 antibody. Protein-DNA complexes were washed, followed by the reversal of crosslinking using a DNA release buffer. The real-time PCR was performed using this eluted DNA obtained using the release buffer. DNA from input samples was also isolated for normalization. To quantify the abundance of H3K36me2, primers tailored to the gene’s promoter sequence outlined in Table 1 were utilized.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v.8.0). Data were represented as mean ± standard deviation. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied for statistical comparison between the two groups, whereas for multiple groups comparison, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s test was conducted. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data and resource availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request. All the resources are available within the article.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request. All the resources are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- BMAL1:

-

Brain and muscle ARNT-like 1

- CLOCK:

-

Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput CRY2:Cryptochrome 2

- PER3:

-

Period circadian regulator 3

- RORA:

-

RAR related orphan receptor A

- FOXO1:

-

Forkhead box protein O1

- ACC:

-

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- CHREBP:

-

Carbohydrate-responsive element binding protein

- FABP4:

-

Fatty acid binding protein 4

- FASN:

-

Fatty acid synthase

- SREBP1c:

-

Sterol-regulatory element binding protein-1 C

References

Goodman, N. F. et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists, American college of endocrinology, and androgen excess and PCOS society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome-part 1. ;21(11):1291–1300. (2015).

Dennett, C. C. & Simon, J. J. D. S. The role of polycystic ovary syndrome in reproductive and metabolic health: overview and approaches for treatment. ;28(2):116–120. (2015).

Kumariya, S., Ubba, V., Jha, R. K. & Gayen, J. R. J. A. Autophagy in ovary and polycystic ovary syndrome: role, dispute and future perspective. ;17(10):2706–2733. (2021).

Glueck, C. J. & Goldenberg, N. J. M. Characteristics of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, treatment, and genetics. ;92:108–120. (2019).

Moghetti PJCpd. Insulin resistance and polycystic ovary syndrome. ;22(36):5526–5534. (2016).

Jena, D. et al. Study of visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat thickness and its correlation with cardiometabolic risk factors and hormonal parameters in polycystic ovary syndrome. ;22(3):321. (2018).

Kim, K-W-J-J-O. Syndrome M Unravelling Polycystic Ovary Syndrome its Comorbidities ;30(3):209. (2021).

Riazi, K. et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. (2022).

Teng, M. L. et al. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. ;29(Suppl):S32. (2023).

Ahmed, A., Wong, R. J. & Harrison, S. A. J. C. G. Hepatology. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease review: diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. ;13(12):2062–2070. (2015).

Marušić, M., Paić, M. & Knobloch, M. Liberati Pršo A-MJCJoG, Hepatology. NAFLD, insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus type 2. ;2021. (2021).

Vassilatou EJWJoGW. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and polycystic ovary syndrome. ;20(26):8351. (2014).

Hong, S. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. ;13(1):13397. (2023).

Manzano-Nunez, R. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. ;12(3):856. (2023).

Rosenfield, R. L. & Ehrmann, D. A. J. E. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. ;37(5):467–520. (2016).

Rocha, A. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. ;40:1279–1288. (2017).

Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M., Kuglin, D., Dąbkowska-Huć, A., Skałba, P. J. E. J. O. & Gynecology, Biology, R. Serum adiponectin and resistin in relation to insulin resistance and markers of hyperandrogenism in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. ;154(1):51–56. (2011).

Benrick, A. et al. Adiponectin protects against development of metabolic disturbances in a PCOS mouse model. ;114(34):E7187–E96. (2017).

Shabalala, S. C. et al. The effect of adiponectin in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the potential role of polyphenols in the modulation of adiponectin signaling. ;131:110785. (2020).

Sanchez-Garrido, M. A. & Tena-Sempere, M. J. M. Metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: pathogenic role of androgen excess and potential therapeutic strategies. ;35:100937. (2020).

Singh, A., Bora, P., Krishna, A. J. B. & Communications, B. R. Direct action of adiponectin ameliorates increased androgen synthesis and reduces insulin receptor expression in the polycystic ovary. ;488(3):509–515. (2017).

Lee, J. M., Kim, H. & Baek, S. H. J. E. medicine m. Unraveling the physiological roles of retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor α. ;53(9):1278-86. (2021).

Hariri, A. et al. The circadian rhythm: an influential soundtrack in the diabetes story. ;14. (2023).

Shi, S., Ansari, T. S., McGuinness, O. P., Wasserman, D. H. & Johnson, C. H. J. C. B. Circadian disruption leads to insulin resistance and obesity. ;23(5):372–381. (2013).

Li, S. et al. Altered circadian clock as a novel therapeutic target for constant darkness-induced insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism of polycystic ovary syndrome. ;219:13–29. (2020).

Sellix, M. T., Murphy, Z. C. & Menaker, M. J. E. Excess androgen during puberty disrupts circadian organization in female rats. ;154(4):1636–1647. (2013).

Roy, S. et al. Androgen-mediated perturbation of the hepatic circadian system through epigenetic modulation promotes NAFLD in PCOS mice. ;163(10):bqac127. (2022).

Okada-Iwabu, M. et al. A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. ;503(7477):493–499. (2013).

Cui, P. et al. Long-term androgen excess induces insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in PCOS-like rats. ;208:105829. (2021).

Nikoulina, S. E. et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 improves insulin action and glucose metabolism in human skeletal muscle. ;51(7):2190–2198. (2002).

Abruzzese, G. A. et al. Prenatal hyperandrogenism induces alterations that affect liver lipid metabolism. (2016).

March, S. et al. Autonomous circadian rhythms in the human hepatocyte regulate hepatic drug metabolism and inflammatory responses. ;10(17):eadm9281. (2024).

Handy, D. E., Castro, R. & Loscalzo, J. J. C. Epigenetic modifications: basic mechanisms and role in cardiovascular disease. ;123(19):2145–2156. (2011).

Spremović Rađenović, S. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and pathophysiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). ;10(1):131. (2022).

Wada, T. et al. Adiponectin Regulates Circadian Rhythm Glucose Lipid Metabolism ;254(2):121–133. (2022).

Hai, Y. et al. Icariin alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in polycystic ovary syndrome by improving liver fatty acid oxidation and inhibiting lipid accumulation. ;28(2):517. (2023).

Zatorski, H. et al. AdipoRon, an orally active, synthetic agonist of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 receptors has gastroprotective effect in experimentally induced gastric ulcers in mice. ;26(10):2946. (2021).

Johnson, B. S. et al. Derailed peripheral circadian genes in polycystic ovary syndrome patients alters peripheral conversion of androgens synthesis. ;37(8):1835–1855. (2022).

Schrader, L. A., Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S. M., Hogenesch, J. B., Bradfield, C. A. & Malecki KMJTJoCI. Circadian disruption, clock genes, and metabolic health. ;134(14). (2024).

Sun, S. et al. Circadian rhythm–dependent induction of hepatic lipogenic gene expression in rats fed a high-sucrose diet. ;294(42):15206–15217. (2019).

Dong, X. & Weng, Z. J. E. The correlation between histone modifications and gene expression. ;5(2):113–116. (2013).

Tsang, A. H., Koch, C. E., Kiehn, J-T., Schmidt, C. X. & Oster, H. J. E. An adipokine feedback regulating diurnal food intake rhythms in mice. ;9:e55388. (2020).

Zhou, J., Tan, Y., Wang, X. & Zhu, M. J. A. Paeoniflorin attenuates DHEA-induced polycystic ovary syndrome via inactivation of TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathway in vivo. ;13(5):7084. (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. High-fat diets exaggerate endocrine and metabolic phenotypes in a rat model of DHEA-induced PCOS. ;151(4):431–441. (2016).

Hu, X. et al. AdipoRon prevents l-thyroxine or isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy through regulating the AMPK-related pathway. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 51 (1), 20–30 (2018).

Khandelwal, M., Manglani, K., Upadhyay, P., Azad, M. & Gupta, S. J. N. D. AdipoRon induces AMPK activation and ameliorates Alzheimer’s like pathologies and associated cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 mice. ;174:105876. (2022).

Shaw, S. et al. Alterations of estrous cycle, 3β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity and progesterone synthesis in female rats after exposure to hypobaric hypoxia. ;10(1):3458. (2020).

Kabeer, S. W., Pant, R., Sharma, S. & Tikoo, K. J. C. B. I. Laccaic acid restores epigenetic alterations responsible for high fat diet induced insulin resistance in C57BL/6J mice. ;374:110401. (2023).

Liu, B. et al. Raw bowl tea (Tuocha) polyphenol prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating intestinal function in mice. Biomolecules [Internet] ; (2019). 9(9).

Leopoldo, A. et al. Classif. Different Degrees Adiposity Sedentary Rats ;49(4):e5028. (2016).

Karbaschi, R. et al. Maternal high-fat diet intensifies the metabolic response to stress in male rat offspring. ;14(1):1–12. (2017).

Cui, A., Hu, Z., Han, Y., Yang, Y. & Li, Y. J. J. Optimized analysis of in vivo and in vitro hepatic steatosis. (121):e55178. (2017).

Pant, R. et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of DNMT1 restores macrophage autophagy and M2 polarization in Western diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. :104779. (2023).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Kulbhushan Tikoo is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We would like to acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, for providing the necessary funding for conducting this study (Grant no. 5/4/5–8/Diab./20-NCD-III). We would also like to acknowledge Ms. Archana Panghal from the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, NIPER SAS Nagar, for helping us cryosectioning liver tissue for oil red O staining. We would like to acknowledge Biorender for the preparation of the study design and graphical abstract figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing: original draft, S.W.K.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing: review and editing, V.K.: Data curation, Formal analysis, K.T.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources, Writing: review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, S., Kabeer, S.W., Kumar, V. et al. Adiponectin receptor agonist, AdipoRon, restores hepatic clock gene expression in PCOS-associated NAFLD. Sci Rep 15, 33729 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93126-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93126-x