Abstract

The 2019 pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 led to millions of deaths worldwide since its emergence. The viral genomic material can code structural and non-structural proteins including the main protease or 3CLpro, a cysteine protease that cleavages the viral polyprotein generating 11 proteins that participate in viral pre-replication. Thus, 3CLpro is a promising therapeutic target for SARS-CoV-2 inhibition by new drugs or drug repositioning because 3CLpro is dissimilar to human proteases. We conducted in vitro assays demonstrating the modulation activity of ambenonium, a drug already used in Myasthenia gravis that acts by inhibiting the action of acetylcholinesterase, and had its potential inhibitory activity against viral replication pointed out in a previous in silico study. In concentrations of 100 µM, 50 µM, 25 µM, 10 µM, and 1 µM there was no inhibition in the formation of lysis plates, with a slight increase in the genome copy number at the higher concentrations evaluated. However, in the concentrations of 0,1 µM and 0,01 µM, there was a reduction in the number of lysis plates. This behavior suggests that the ambenonium acts as a modulator of viral activity in vitro. To investigate potential conformational changes in the protein between dimeric and monomeric forms in the presence of the compound, a local docking analysis was performed. Results indicated this conformational shift is possible, though further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2019, in the city of Wuhan1, a novel virus emerged and was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) through metagenomic analysis of samples obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with severe pneumonia2. In accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO), over 700 million cases of the disease have been registered worldwide since the beginning of the pandemic, with over seven million deaths recorded3. In other words, the disease, while largely contained, continues to impact the population.

SARS-CoV-2 is the causative agent of the COVID-19 pandemic4 and is a positive-sense, single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus belonging to the Coronaviridae family. The Coronaviridaefamily is characterized by high rates of recombination and mutation, resulting in an ecological diversity5, being able to infect from birds to whales. Coronaviruses are included in the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily, which has four genera: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Deltacoronavirus, and Gammacoronavirus. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Betacoronavirus,and this genus has a unique feature in its structure: a solar corona form caused by spike proteins on the virus surface6.

The spike (S) protein is one of the four structural proteins in coronaviruses; the others are the M (membrane) protein, the E (envelope) protein, and the N (nucleocapsid) protein. The E and M proteins are responsible for the virus assembly, the N protein forms the capsid in which the genome is sheltered, and the S protein is responsible for the host cell recognition and entry. This entry, mediated by S protein, happens because the virus protein can bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor that is present in the host cells surface, including lung7. In addition to the four structural proteins, the virus has non-structural proteins as the main protease (Mpro), also termed 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), which is a cysteine hydrolase responsible for polyprotein (UniProt ID: P0DTC1) cleavage and a promising target to the development of anti-CoV agents8.

However, despite the improvements in drug discovery, cost efficiency still needs to improve9. The drug discovery process is, in practice, a chain of challenges in the pathway from a possible therapeutic candidate to in vivo administration because there are issues, biological and chemical, that are expensive and time-consuming to address10. Usually, this process takes 10 to 15 years and can cost US$2.8 billion, on average, and a high proportion of candidate molecules, as 80% to 90%, will fail in the clinical trial phase11.

Drug repurposing is using a drug already approved by regulatory agencies, such as the FDA, for a new indication12. This process has been used for a variety of diseases and also in the search for a COVID-19 treatment13,14,15. The primary purpose of drug discovery is to determine the safety, pharmacokinetics, and potency, defined as the amount of a drug necessary to produce a specific effect16.

Drug design is the inventive process of developing new drugs, and methods like Computer-aided drug design (CADD) have a huge potential because they combine computational chemistry, molecular design, and molecular modeling. Having access to massive data is not equal to applicable predictive models; it is necessary to evaluate side effects and therapeutic efficacy, and the techniques must be able to deal with a high volume of data, sparse data sources, and multidimensional data17.

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) is a CADD technique that focuses on analyzing the three-dimensional structures of target proteins and characterizing their binding site cavities. This method has emerged as an effective approach for optimizing and generating ligands in the pharmaceutical industry. The fundamental steps involved in SBDD include preparing the target, identifying the binding site cavity, conducting virtual screening, performing molecular docking, and carrying out molecular dynamics (MD)18. In a previous study conducted by our research group19, we developed an in-house machine learning strategy that was integrated with docking, MM-PBSA, and metadynamics to identify a potential inhibitor for the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

There are specific antiviral drugs available for COVID-1920,21,22. However, the treatment did not have the adherence expected, primarily due to the lack of accessibility and cost-effectiveness23. Consequently, it remains essential to pursue research into novel effective and affordable therapeutic agents against SARS-CoV-2. The treatment and inhibition of the COVID-19 virus can incur high costs. In 2020, in China, expenditures related to COVID-19 exceeded $0.62 billion24, with many patients requiring mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal oxygenation. Furthermore, various pharmaceutical interventions were employed to mitigate disease complications, including hydroxychloroquine, albeit with limited efficacy25.

Another crucial aspect of treatment effectiveness lies in observing and identifying potential therapeutic targets, which may influence biased outcomes. The virus is highly contagious, and variants with high transmission potential have been identified. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting the ineffectiveness of some existing vaccines26,27. Scientific efforts are still being conducted worldwide; however, they have resulted in only a few clinically approved vaccines. Moreover, the nature of the virus and its ability to mutate present new challenges28.

In this work, we evaluated the ambenonium, a molecule used in the treatment of Myasthenia gravis29, as a potential inhibitor for the main protease of SARS-CoV-2, as this molecule, to the best of our knowledge, is not described in the scientific literature for this purpose. It is important to highlight here that this molecule is an inhibitor for the human enzyme acetylcholinesterase, not an inhibitor for the main protease of the virus. Its potential inhibition for the viral enzyme was proposed by an early study of our group19,29.

We conducted experiments to verify the action of ambenonium in vitro, following in silico experiments. The first test analyzed enzyme activity in the presence of different ambenonium concentrations. Subsequently, cell culture tests were performed to assess cell viability in the presence of the compound, enzyme response to the compound, and viral fitness.

Materials and methods

Mammalian cells

Vero CCL-81 cells (ATCC CCL-81) and HEK-293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, DMEM (GIBCO, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Massachusetts, USA) and 1% pen-strep solution (Sigma, MO, USA), pH 7.2 at 37℃ in a humid atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The Vero CCL-81 cells were purchased from the BCRJ (Rio de Janeiro Cell Bank, Brazil), and the HEK-293 cells used were obtained from the Centro de Tecnologia de Vacinas (CT Vacinas) stock.

Compounds

The ambenonium used in the assays was purchased from LGC Standards (Luckenwalde, Germany). The compound was prepared as stock solutions at 5 mM concentration in 100% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Neon Comercial Reagentes Analíticos Ltda, SP, Brazil). The DMSO was diluted during the preparation of the compound using a buffer with a final DTT concentration of 1 mM. Serial dilutions were then performed at a 1:10 ratio to achieve a final compound concentration ranging from 100 µM to 0.01 µM.

Ambenonium effect on 3CLpro

The steady-state kinetic parameters assay was performed in a 96-well plate using the 3CL Protease MBP-tag Assay Kit (BPS Bioscience, San Diego, CA) and the manufacturer’s recommendations were followed.

The concentration of ambenonium used in the assays was between 0.01 μM and 100 μM, obtained after a ten-fold serial dilution. The inhibition control (GC376, included in the Assay kit, a broad-spectrum antiviral compound) was serially diluted exactly as the test compound. The positive control contained only protease and diluent solution (no inhibitor) and the blank contained only assay buffer and diluent solution. The 96-well plate was prepared at room temperature without agitation, and the fluorescence was measured for 12 h at 460 nm in a microplate reader. From the data obtained, the Vmax and Km were calculated for each concentration using well established equations. The positive and negative controls, as well as the blank, were prepared using the same buffer solution (final concentration: 5 ng/μL) containing the 3CL protease.

Cytotoxicity to mammalian cells

The cytotoxicity of the ambenonium was performed in Vero CCL-81 cells and HEK-293 cells. Briefly, cells were incubated with different concentrations of the ambenonium between 0.01 µM and 100 µM, for 24, 48, and 72 h. The experiments were conducted with biological duplicates and seven technical replicates, and the graph was constructed based on the average value obtained from the number of genomic copies. Triton-X and DMSO were used as cellular death controls, at concentrations of 25% and 50%, respectively. After the incubation period, the cytotoxicity was assessed by the Alamar Blue (Thermo-Fisher) method. This reagent is a resazurin-based solution. Resazurin is a sodium salt, and in its oxidized form is a blue dye. In the presence of cellular metabolic activity, it is reduced to resorufin that has a pink color, which can be measured by a colorimetric or fluorometric reading30.

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity assay

The assays were performed in 24-well plates. 2 × 105 cells/mL of Vero CCL-81 were seeded and plates were incubated at 37℃ in a humid atmosphere containing 5% CO2for 24 h. After this period, the medium containing the SARS-CoV-2 virus was removed, and 30 PFU/mL were added to new 24-well plates in duplicate, containing different concentrations of ambenonium. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with periodic homogenization to enable the interaction between the ambenonium, the virus, and the cellular receptor. After the incubation period, the supernatant was removed and the cellular monolayer was covered with semisolid medium (carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) at 1% in DMEM with 5% SFB) and the lysis plates were counted after 72 h. For visualization and count, the plates were fixed using formaldehyde 8% and violet crystal. For this study, the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1, isolated SP02/BRA variant was used31.

For this essay, in our understanding, the most assertive controls were the virus control and the cell control. Similar to this study, other published works do not consider DMSO as a control because the stock of the compound undergoes serial dilutions with DMEM at 0% FBS32. To access the antiviral potential against SARS-CoV-2 of the ambenonium, qRT-PCR was applied to quantify the genomic copies of the SARS-CoV-2 genome.

Docking and molecular dynamics simulations

After the in vitro assays, we conducted a local docking with focus on the binding site: H41, S46, M49, Y54, F140, L141, N142, G143, C145, H164, M165, E166, L167, P168, H172, A173, F185, D187, Q189, T190, A191, and Q192. This experiment was conducted using AutoDock Vina33 to perform the docking using both the monomeric and dimeric forms of the main protease, with the ambenonium. For the monomer, the grid box was designed to include the catalytic dyad residues, with HIS41 selected as the central reference point, as it is more centrally positioned than CYS145. In contrast, for the dimer, the grid box must not only capture the catalytic dyad residues but also GLU166, which interacts with the N-finger. For both forms, the grid box was set in the following dimensions: 24, 24, 24 Å, coordinates (17.953, −35.477, 1.686). This interaction is essential for dimer stabilization and plays a critical role in the protease enzymatic activity. There were three simulations replicas and we set the tool to generate ten poses for each form in each replica.

Following the docking simulations, we conducted MD simulations of 100 ns to evaluate the interaction between ambenonium and the 3CLproin the apo form of the dimer, the dimer and the monomer. The best docking poses for the dimer and the monomer were selected for these simulations. The NAMD34software was used to perform the simulations, employing the CHARMM3635force field for protein topology preparation. Additionally, the ligand molecules topology was prepared using the CHARMM force field through the General Force Field (CGenFF) server36. A cubic box with boundary conditions of 10 Å was used to solvate the systems, and ions were added to neutralize the system. The systems were initially subjected to equilibration processes under NVT and NPT conditions for 1000 ps with a time step of 2 fs. Subsequently, the systems proceeded to the production stage of the MD simulations of 100 ns.

The MD analysis between the protein and ambenonium was conducted to understand the structural and energetic aspects of the complex. Structural fluctuations were evaluated using Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), while changes in the solvent-accessible surface area were analyzed with SASA (Solvent-Accessible Surface Area)37. Hydrogen bonds were monitored over time to identify critical contacts between the protein and the ligand. Finally, binding free energy calculations such as MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) and MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area) revealed the affinity of ambenonium for the active site, complementing the structural analysis38.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism versions 5.03 e 8.0 (GraphPad Software Incorporated, CA, USA). When p < 0.05, the results were considered statistically significant and were identified by an asterisk (*).

Results and discussion

Ambenonium effect on 3CLpro

Enzymes have long been recognized as excellent drug targets. Almost half of all clinically used oral drugs target an enzyme39, and many drugs in big pharma companies’ portfolios target an enzyme. An enzyme is a dynamic system because it can bind to many targets, form intermediates and final products in the catalytic cycle40.

In the case of the novel coronavirus, the main protease is one of the most well-defined drug targets. The SARS-CoV-2 3CLprois an essential enzyme for the virus, responsible for processing polypeptides and acting as a cysteine protease that cleaves peptide bonds to produce 11 non-structural viral proteins, including its own N- and C-terminal boundaries41. This activity is crucial for viral replication42. Figure 1 displays the 3D structure of 3CLpro, highlighting the active site. It is anticipated that, once bound to the main protease, ambenonium would inhibit the activity of the enzyme and block viral replication43.

Chain A of crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. (A): Cartoon representation of 3CLpro (PDB ID: 7KFI) with domain I (residues 8–101) shown in pink, domain II (residues 102–184) shown in green, and domain III (residues 201–301) shown in gold. (B): Active site of 3CLpro.The catalytic dyad, HIS41 in domain I and CYS145 in domain II, are shown in red. The substrate is shown in stick representation in gray. This figure was prepared using PyMol44 (Schrodinger LLC).

The domain III of the 3CLprowas identified as being of huge importance for dimerization and formation of the active enzyme. The active site of the protease is the interface between domains I and II, with the catalytic dyad formed by Cys-His, and a water molecule at the binding site playing the role of the third residue. This biochemical characterization of the main protease is essential for optimal conditions to be used in enzymatic assay, as the one conducted in the present work45.

In physiological conditions, the protease exists as a homodimer, with two monomers placed in a perpendicular orientation regarding each other positions. There is a contact interface of, approximately, 1,3 A between domain II of the chain A and the NH2-terminal residues (N-finger) of the chain B. The dimerization of the enzyme is crucial to the catalytic activity, with the N-finger of one monomer interacting with GLU166 of the other monomer helping in the formation of the S1 subpocket of the substrate binding site43.

Despite the dimer configuration in physiological conditions, the representation of the monomer is usual, and in a study conducted by Weng and colleagues, they discovered that there was no increase in the stability, or the affinity to the ligand, of the dimer complexes tested when compared with the monomer complexes28,46. Is important to note that each chain monomer of the enzyme has an active site consisting of the catalytic dyad, and as observed, the monomer can fold into a tertiary structure, but mutational analysis showed that in this form, the catalytic activity is very low or nonexistent47.

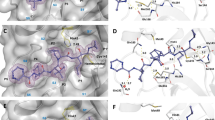

In a previous work conducted by our research group19, six compounds were indicated as potential inhibitors to the main protease, and one compound, ambenonium, in particular, was not yet described in the literature with this purpose. In Fig. 2, it is possible to see the protein–ligand complex formed between the main protease and ambenonium. In this work the monomer structure was used to represent the main protease.

Ambenonium in 3CLpro active site. This figure shows the ambenonium in the active site of the main protease, this was done using AutoDock Vina, in an experiment conducted by De Souza Gomes et al., 2022. The ligands (in blue) are well fitted in the 3CLpro active site (in orange). Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dashed lines; attractive electrostatic interactions, as orange dashed lines; orbital π interactions, as pink, yellow and purple dashed lines; unfavorable interactions, as red. Residues involved in hydrophobic interactions are represented by light green circles.

Ambenonium is a drug already approved by the FDA for treating myasthenia gravis. This autoimmune disease causes muscle weakness due to the production of antibodies against proteins at the neuromuscular junction. The mechanism of action of ambenonium consists of its interaction with the acetylcholinesterase in the anionic site, preventing the cleavage of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine by the enzyme48.

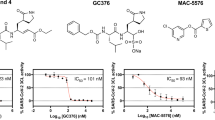

Different concentrations of the ambenonium were used to identify the concentration that could impact viral replication. As depicted in Fig. 3, an inhibition of viral activity could be expected; instead, it is possible to observe an increase in the activity of the main protease by measuring the relative fluorescence at each concentration of ambenonium. However, at the concentration of 1 µM, the increase was not statistically significant, although it was higher than the positive control GC376.

3CLpro enzymatic inhibition assay. Different concentrations of ambenonium were tested to assess their effects on viral replication over different time intervals. The relative fluorescence units (RFUs) at 12 h after reaction initiation were normalized to control and used to indicate the enzymatic activities. Each bar represents the average of experiments performed in triplicate. The fluorescence values are presented as an arbitrary unit. The data were subjected to a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Test using GraphPad Prism version 5.03. The asterisks mean statistical difference with p < 0.05 in relation to control. Amb: Ambenonium. GC376: positive control. The data are representative STD and mean.

Substrate concentration, enzyme concentration, pH, temperature, activator, and inhibitors are known factors that affect a chemical reaction catalyzed by an enzyme; if the enzyme concentration increases, the reaction rate increases as well. The velocity is known as the maximum velocity (Vmax) of the reaction catalyzed by the enzyme; the Km is known as the Michaelis-Manten constant and represents the substrate concentration at half the value of Vmax49.

Vmax and Km were calculated using well established equations for each concentration of the ambenonium. It was observed that when both Vmax and Km were reduced, the ambenonium had double activity, acting as an inhibitor or as an activator, depending on the ratio created between the amount of the small molecule and the enzyme itself, as shown in Fig. 4 (A and B). Km is a constant for every enzyme, does not change when the enzyme concentration changes, and can be used to identify an enzyme in particular. The same cannot be said about Vmax, as it will change whenever the enzyme concentration changes. Lower Kmvalues indicate that the enzyme has a higher affinity for the substrate and vice-versa50,51.

Enzyme kinetics for each substrate concentration (ambenonium). (A): Vmax of the enzyme activity for each ambenonium concentration. (B): Km for different concentrations of ambenonium. The concentration of 0.1 μM of ambenonium, for both Vmax and Km, indicates a high affinity of the compound for the enzyme. Vmax and Kmwere calculated using well-established equations50,52.

Contrary to the anticipated inhibition of viral replication, ambenonium was found to modulate viral activity. This unexpected finding suggests that the drug can either stimulate or inhibit viral replication, depending on its concentration. This distinctive behavior of ambenonium, acting as a modulator rather than a simple inhibitor, is attributed to its binding to the enzyme’s active site and subsequent stabilization, thus increasing the enzyme’s activity.

However, understanding the role of enzymes in disease and implementing strategies to modulate their activity in therapeutics is essential in drug discovery. Although enzymology is a powerful method, it cannot provide scientific insights into problems that can arise along the way, from target identification to proof of concept in the clinic. Furthermore, it is imperative to continuously link enzymology with protein structural analysis and other biophysical methods to provide all the information necessary for drug discovery40. In a paper for 198153, Sols had already discussed the multi-modulation of the enzyme activity and the possibility of some enzymes having an accumulation of regulatory mechanisms of different types, cooperative, interconversion, allosteric or any combination of these or the same kind of multiple allosteric effects. This might represent a paradoxical effect: cytotoxicity of the compound, which is not applicable, as it has been shown to be non-cytotoxic, or protein aggregation, which could result in a diminished drug effect at higher concentrations54.

In a study conducted by Silverstein55, he demonstrated that the usual effect expected in enzyme kinetics is this: enzyme activators lower Km and/or raise Vmax, and on the contrary, an enzyme inhibitor raises Km and/or lower Vmax. But what would happen if a molecule moves both in the same direction, as shown here, in the present work? Chen and colleagues56 demonstrated the effect of crowding agents on enzyme activity, focusing on how these agents can influence both the Km and Vmax of enzymatic reactions. It is demonstrated that in the presence of crowding agents, both Km and Vmax can be increased, which has significant implications for the behavior of drugs designed to act as inhibitors. When a study is conducted in vitro,it typically occurs using diluted solutions containing a few essential solutes, ignoring the complexity of the actual situation. In a cellular environment, proteins, lipids, ribosomes, and DNA are present, this is the concept of macromolecular crowding57. This crowding effect can slow down the molecular collisions, alter protein stability, binding interactions and enzyme kinetics55.

Under these conditions, the drug may bind to the enzyme, but fail to function purely as an inhibitor. Instead, it may behave as both an inhibitor or an activator, depending on the specific dynamics of the enzyme–substrate interaction in the crowded environment. This dual effect complicates the prediction of the overall impact of the drug, as its inhibitory action can be attenuated or enhanced by the presence of macromolecular crowding, influencing the efficiency and specificity of the therapeutic response58,59.

Cytotoxicity to mammalian cells and anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity assay

Cell cytotoxicity assay is usually used for drug screening to detect if a test molecule affects cell proliferation or will show a direct cytotoxic effect. Despite the type of cell-based assay being used, it is crucial to find out how many cells will remain at the end of the experiment60. The presence of dead cells with membrane loss integrity can be detected by measuring the markers that leak to the culture medium from the cytoplasm.

For example, the reducing capacity of NADH can be used in the metabolism of many molecules to transform them into their fluorescent products61,62,63.In the present work, this reducing power of NADH was used to convert the substrate (resazurin or AlamarBlue) into the fluorogenic product (resorufin)60,64,65. The reduction assay using resazurin is almost inexpensive, and this fluorescent signal generated is one of the best ways to evaluate the changes in cell viability across different types of cell densities and metabolic states. Besides, resazurin is non-toxic to the cells66.

In Fig. 5, it is shown the cytotoxicity assay for two different cell lineages, Vero and HEK, in the presence of the ambenonium, Triton and DMSO, for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. These cell lines are commonly used in virological research67,68.

Cytotoxicity assay for Vero and HEK cells using Alamar blue method. Cells were incubated for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h with ambenonium in different concentrations. The gray area in the graphics corresponds to the cellular viability, ranging from 80 to 100%. The blue line shows the cellular viability in the presence of ambenonium, the orange dashed line shows the viability in the presence of DMSO, and, in red, the viability in the presence of Triton. The data are representative of at least seven internal replicates, with STD and mean. The data were subjected to a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Test using GraphPad Prism version 5.03. The asterisks mean statistical difference with p < 0.05 in relation to ambenonium. * means p < 0.05, ** means p < 0.01 and *** means p < 0.001.

The gray area in the graphs represents the range of cellular viability, from 80 to 100%. After 24 h, Vero cells showed reduced viability, as the curve was out of the range of the viability previously calculated. However, this trend improved at both the 48 h and 72 h marks, indicating that ambenonium is safe across all tested concentrations for these cells. In contrast, HEK cells displayed different viability patterns compared with Vero cells at every concentration and time point, with the most notable differences observed after 72 h. Specifically, at a concentration of 1 µM, HEK cell viability at 24 h was comparable to the toxicity observed with DMSO, and similarly, at 0.01 µM after 48 h. For all time points, cell viability in ambenonium-treated samples was statistically higher compared to those treated with DMSO and Triton, except for the DMSO-treated HEK cells at 48 h. These results reinforce the safety of ambenonium, consistent with its therapeutic use in myasthenia treatment69.

Figure 6 confirms that there was no inhibition in the formation of lysis plates at the concentrations 100 µM, 50 µM, 25 µM, 10 µM, and 1 µM. This fact suggests a non-inhibitory activity of ambenonium against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease since the formation of lysis plates indicates that the virus was capable of replication leading to cell death caused by the membrane cell rupture. However, at the concentrations of 0.1 µM and 0.01 µM, there was a reduction in the number of lysis plates compared to the control. This result suggests that the ambenonium does not have an inhibition activity against the 3CLpro, but can act as a modulator for its activity.

Non-linear regression of the percentage of inhibition of lysis plates. In concentrations of 100 µM, 50 µM, 25 µM, 10 µM, and 1 µM there was no inhibition in the formation of lysis plates. However, in the concentrations of 0.1 µM and 0.01 µM there was a reduction in the number of lysis plates compared to the control. All results are presented in relation to the control. The data were subjected to a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Test using GraphPad Prism version 5.03.

In this last assay, after the infection, the inoculum was removed and the Vero cells were incubated for 72 h. After that, 40 µL of the supernatant containing the virus was removed for viral RNA extraction. The number of genomic copies of the genetic material of the virus is shown in Fig. 7.

This analysis was carried out using specific primers for RT-qPCR. The results showed that the number of viral genomic copies is more considerable in higher concentrations of ambenonium evaluated. In a work conducted in 201470, they proposed that some mutations in HIV improved the fitness of the mutant virus in the presence of raltegravir, a drug used in antiretroviral therapy. However, this kind of study is difficult to perform because it involves expensive experiments and requires a well-equipped biosafety laboratory to conduct tests involving live viruses, not just inactivated enzymes. Still, it would be interesting to be able to further investigate the modulation activity of ambenonium.

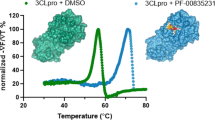

Docking and molecular dynamics simulations

Here, we present the results of docking performed using AutoDock Vina. Initially, the docking was carried out with ambenonium as the ligand and the monomeric form of the main protease. Following that, docking was performed with ambenonium and the dimer, since this is the active form of the protein. However, as shown in previous studies, only the monomer is typically used for in vitro studies8,19,45,46,71 with the second protomer acting as structural support for the first chain. The Vina scores (in kcal/mol) are shown in Table 1.

Although ambenonium can bind to both the monomeric and dimeric forms of the protease, we observe that the scores for the monomer are more negative (expressed in kcal/mol). In Fig. 8it is possible to observe the quaternary structure formed by the main protease dimer. This indicates that the interaction between ambenonium and the monomeric form of the protease is stronger than with the dimeric form, as a more negative Vina score reflects a higher predicted binding affinity72. The stronger interaction in the monomer may result from more favorable interactions, such as hydrogen bonding or Van der Waals forces, that contribute to a more stable ligand-receptor complex. While the electronic properties of ambenonium, including its potential for forming interactions with polar or charged residues, may contribute to this stronger binding, it is important to note that Vina scores also account for factors like hydrophobic interactions and ligand flexibility33.

The subunits of the homodimer (PDB ID: 7KFI). The domain I (residues 8–101) is shown in magenta, the domain II (residues 102–184) is shown in blue, and domain III (residues 201–301) is shown in yellow. Each monomer comprises a catalytic dyad formed by the residues His41 and CYS145 and they are shown in red spheres. This figure was prepared using PyMol (Schrodinger LLC).

Whereas the active form of the enzyme is the dimer, ambenonium interacts with the main protease in both forms. However, in the dimeric form, the interaction may not be strong enough to completely inhibit the enzyme, as it binds to one monomer while the other monomer remains free to continue enzymatic activity, though at a lower47.

The development of inhibitors for cysteine proteases presents a challenge, whether due to toxicity or lack of specificity caused by covalent modifications to untagged cysteine residues73. But, for complete enzyme inhibition, a two-step mechanism of action is often employed, particularly in the case of covalent inhibitors, such as GC37674. In this mechanism, the inhibitor can bind competitively to the substrate-binding cavity of the main protease, a cysteine protease, bringing it into proximity with the cysteine residue in the catalytic dyad. Subsequently, a covalent bond forms between the inhibitor and the target cysteine (the catalytic dyad cysteine), resulting in irreversible inhibition73,75. As shown in Fig. 9, the hydrogen bonds formed after molecular docking can be observed in both the monomeric and dimeric forms. The key residues involved, including HIS41 and CYS145, were previously highlighted in Fig. 2, which presents the docking analysis conducted by De Souza Gomes and colleagues19.

Hydrogen bonds after molecular docking between the 3CLpro and ambenonium. The carbon atoms are represented in magenta, oxygen atoms in red, nitrogen atoms in blue, and ambenonium in white. The yellow dashed lines indicate the hydrogen bonds formed between ambenonium and the protein. (A) Hydrogen bonds formed between the monomeric form of 3CLpro and ambenonium after docking analysis. (B) Hydrogen bonds formed between the chain B of 3CLpro dimeric form and ambenonium after docking analysis. The figures highlight the involvement of the catalytic dyad (HIS41 and CYS145) in the interaction, along with other key residues present as sticks. These visualizations were generated using PyMOL (Schrödinger LLC).

Hydrogen bonds are considered a crucial element in molecular recognition and play a key role in host–guest complex formation, DNA base pairing, and enzymatic catalysis. They are also responsible for the stabilization of the 3D structures of drug targets, such as DNA and proteins76. Hydrogen bonds are not as strong as covalent bonds, but are stronger than noncovalent interactions such as van der Waals forces. Additionally, the directionality of hydrogen bonds influences how molecules arrange in space77. In Fig. 10, the hydrogen bonds formed between ambenonium and the monomeric form of the main protease during MD simulations can be observed, along with the key residues involved in protein–ligand complex formation and stabilization. Similarly, Fig. 11 illustrates the hydrogen bonds formed during the MD simulation between the dimeric form of the main protease and ambenonium, as well as the key residues contributing to protein–ligand complex formation and stabilization.

Hydrogen bonds observed during MD simulations between the monomer and ambenonium. The plot illustrates the hydrogen bond interactions between the ligand ambenonium and the residues of the monomer over time during a molecular MD simulation. The x-axis represents the simulation frames, while the y-axis denotes the amino acid residues involved in hydrogen bonds. Each black dot corresponds to a detected hydrogen bond at a specific frame, highlighting the temporal persistence and variability of these interactions. Notably, residues CYS145, SER144, VAL42 and LEU27 exhibit frequent interactions, suggesting their potential role in ligand stabilization within the active site of the protein.

Hydrogen bonds observed during MD simulations between the dimer and ambenonium. This plot illustrates the temporal evolution of hydrogen bond interactions between the ligand ambenonium and dimeric residues throughout a MD simulation. The x-axis denotes the simulation frames, while the y-axis lists the amino acid residues forming hydrogen bonds with the ligand. Each black dot represents an observed interaction at a given frame, highlighting fluctuations in binding dynamics. Notably, CYS145, HIS41, and THR25 emerge as key interacting residues, potentially influencing ligand stabilization and dimer stability.

However, a reversible inhibitor can form a covalent bond with the main protease, but this bond can be disrupted in certain circumstances, allowing the enzyme to regain its function. The chemical structure of ambenonium consists of a quaternary ammonium with two chlorobenzyl groups attached to nitrogen atoms78. Therefore, to achieve complete inhibition of the main protease as observed in the in silico study, chemical modifications in this molecule may be necessary, or as suggested by Chen and collegues73, the addition of reducing agents that could be used in conjunction with ambenonium. The use of enzyme inhibitors in combination with other molecules is already documented and used in clinical practice, like the peptidomimetic inhibitors for HIV protease66and the small molecule inhibitors applied for HCV protease79.

The binding of small molecules to the main protease induces structural changes that can impact enzymatic activity80. Based on the MD simulations conducted, ambenonium establishes hydrogen bond interactions with key residues in both the monomeric and dimeric forms of the main protease. Analysis of hydrogen bond interactions over 1,000 frames (100 ns) reveals that in the monomeric state, ambenonium primarily interacts with residues CYS145, SER144, VAL42 and LEU27 suggesting a stabilization effect within the active site. These interactions are consistent with previous crystallographic data80, indicating the involvement of these residues in ligand binding and enzymatic function. The persistence of interactions with CYS145, a catalytic residue, further supports its role in ligand recognition.

In dimeric state, the ligand exhibits interactions with a slightly different set of residues, including CYS145, HIS41, and THR25. CYS145 and HIS41 constitute the catalytic dyad, implying that ambenonium may influence enzymatic activity through direct binding to these key residues. Additionally, THR25 and VAL42 contribute to binding stabilization, which could play a role in modulating dimerization and overall protein function. These findings align with the structural insights provided by Fornasier and colleagues (2024)81 reinforcing the idea that ligand binding induces conformational adjustments that affect both active site architecture and dimer interface stability.

The MD analysis between the protein and ambenonium revealed significant differences in structural stability, flexibility, and active site accessibility across different forms (apo, dimer, and monomer). The RMSD plot depicted in Fig. 12 showed that the apo form of the dimer exhibited greater structural stability, with smaller variations throughout the simulation. In contrast, the dimer combined with ambenonium displayed moderate fluctuations, suggesting conformational rearrangements induced by the presence of the ligand. The combined monomer, however, exhibited a significant increase in RMSD after 700 ps, indicating structural instability or more pronounced conformational adjustments.

A comparative Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analysis over time for the apo form, the dimer, and the monomer of the main protease and ambenonium. The x-axis represents time in picoseconds (ps), while the y-axis denotes RMSD in Angstroms, which quantifies structural deviation from the initial conformation. Blue line (apo form: dimer) represents the RMSD of the dimer in its unbound state, exhibiting relatively stable fluctuations around 4–5 Å and 100 ps. Orange line (combined: dimer + ambenonium) depicts the RMSD of the dimer complexed with ambenonium, showing a slightly higher deviation than the Apo Form, particularly after 200 ps, suggesting ligand-induced structural variations. Green line (combined: monomer + ambenonium) represents the monomer complexed with ambenonium. Initially, it shows the lowest RMSD values, indicating structural stability. However, around 800 ps, a sharp increase suggests significant conformational changes.

The RMSF analysis, in Fig. 13, highlighted local residual fluctuations, revealing greater rigidity in the apo form, in both chains. The introduction of ambenonium increased the flexibility of specific regions, with the most notable impact observed in chain B under monomeric conditions, particularly after residue 200. This suggests that the ligand influences the local dynamics of the protein, especially in less stable conditions, such as the monomeric form.

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis. The analysis was performed to assess the flexibility of individual residues in the protein structure. The introduction of ambenonium induced noticeable changes in the dynamic behavior of the enzyme, even in the monomeric form, with a significant increase in flexibility observed after residue 200. Notably, residues 201 to 301 belong to Domain III, which comprises the C-terminal region of the enzyme. This domain plays a crucial role in stabilizing the interface between monomers, thereby influencing the overall structural integrity and stability of the protein. The observed fluctuations in this region suggest that ambenonium binding may alter the interactions essential for dimer stabilization, potentially affecting the functional state of the enzyme.

The SASA, shown in Figs. 14 and 15, complemented these observations, showing that the apo form of chain B reaches stability in the solvent after the first 400 frames. Comparing the dimeric and monomeric forms in the presence of ambenonium, the dimer displayed lower SASA (~ 1000 Å2), indicating greater protection of the active site, while the monomer exhibited higher exposure (~ 1300 Å2), suggesting increased solvent accessibility. This reinforces the idea that the dimeric form keeps the active site more closed and protected, whereas the monomeric form provides greater accessibility, potentially facilitating interactions with the ligand.

SASA Analysis of active site, dimer and monomer forms. SASA analysis of the active site shows that the dimer (blue) has consistently lower SASA values (~ 800–1000 Å2) compared to the monomer (orange, ~ 1200–1400 Å2). This indicates reduced solvent exposure in the dimeric form, likely due to structural compactness or intersubunit interactions, highlighting the impact of oligomerization on active site accessibility.

Conformational Dynamics and Solvent Accessibility of the Apo Form (Chain B). SASA analysis of the apo form (dimer, chain B) shows a gradual increase in solvent exposure over time, stabilizing at ~ 9000 Å2 after frame 400. This trend suggests a conformational adjustment during the simulation, potentially leading to greater accessibility of the structure to the solvent environment.

Based on the analysis of the data collected, ambenonium may have more flexibility to form hydrogen bonds with the monomer, leading to a gradual increase in interactions throughout the simulation. In the dimer, however, steric barriers or conformational changes could restrict hydrogen bonding, keeping the number stable over time. The monomer may allow a more dynamic fit for ambenonium, promoting transient interactions. In the dimer, the presence of another chain could restrict these movements, limiting the flexibility of ambenonium.

These results highlight that ambenonium distinctly influences the structural dynamics of the protein in its different forms. The dimer demonstrates greater overall stability and reduced active site exposure, whereas the monomer, although more flexible and less stable, forms stronger interactions with the ligand. These characteristics are crucial for understanding the behavior of the protein-ambenonium complex and can guide future studies on its functionality and potential biological applications.

The binding free energy values (ΔG) calculated using the MM-GBSA and MM-PBSA methods provide crucial insights into the strength of interactions between ambenonium and chain B of the protein in its different forms (monomeric and dimeric). The MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA methods are computational techniques widely used in drug discovery to estimate binding free energies between ligands and proteins. While both combine molecular mechanics with implicit solvation models, MM-PBSA relies on the Poisson-Boltzmann model for polar solvation, and MM-GBSA uses the Generalized Born approximation. These methods offer a balance of speed and efficiency but may lack precision in capturing entropic effects explicitly82. Table 2 presents the results of these free energy calculations.

In the monomeric form, the ΔG values are negative, indicating that the interaction between ambenonium and chain B is thermodynamically favorable. The MM-GBSA calculation yields a more negative value, suggesting that factors such as solubility and polarity significantly contribute to the stabilization of the binding. Conversely, the MM-PBSA calculation, with less negative values, suggests that electrostatic contributions are less pronounced in the monomeric form.

In the dimeric form, the ΔG values are even more negative, indicating more stable interactions between ambenonium and chain B. The MM-GBSA result (−35.21 kcal/mol) demonstrates that hydrophobic interactions and the solvated environment play a crucial role in stabilizing the dimeric complex. The MM-PBSA value, while less negative, also reflects favorable interactions but with reduced influence from electrostatic forces.

When comparing the two forms, the dimeric conformation exhibits more negative ΔG values in both methods, suggesting that the dimer provides a more stable environment for ambenonium binding. This increased stability may be associated with the protection of the active site, which facilitates more effective interactions in the dimeric form.

Finally, the more negative values obtained by MM-GBSA in both forms indicate that this method places greater emphasis on hydrophobic interactions and the solvated environment, whereas MM-PBSA reflects a stronger influence from electrostatic interactions. This difference highlights the importance of considering both methods to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of interaction stability in the studied system.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to investigate the potential inhibition activity of ambenonium against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2. This activity was previously suggested in an in silico study conducted by our research group19. Ambenonium is already used to treat myasthenia, meaning it has been proven safe for human use. Different compound concentrations were used, and fluorescence was measured to obtain Vmax and Km values. In the second part, a cytotoxicity assay was performed to assess cell viability in the presence of the compound. An assay of the compound’s potential inhibition activity against the virus was conducted, followed by quantification of the virus’s genetic material.

The results indicated that ambenonium does not seem to possess inhibitory activity as suggested in the in silico study, but a modulation of enzyme activity was observed. At higher concentrations of the compound, the enzyme doubled the activity, whereas a reduction in activity could be expected for an inhibitor. Modulation of enzymatic activity can be a target for developing new drugs or drug repurposing. This modulation was confirmed when the viral genetic material was quantified. If the compound had inhibitory activity, the amount of viral RNA detected would have been very low or almost nonexistent, contrary to what was observed. The docking simulations performed showed that the interaction between the monomer of the main protease is stronger than the interaction between the dimer and ambenonium, which could explain the results observed in our in silico study and this in vitro study.

Analyzing the experiments, it was possible to emphasize the importance of in vitro studies following in silico work. Despite attempts to replicate the exact conditions of a biological system, computational simulations will always exhibit differences when compared with a living cell. This variation arises from the intricate nature of cellular environments, where factors like molecular crowding, stochastic processes, and dynamic interactions with other cellular components are challenging to fully capture in silico. Computational models necessarily simplify these complex processes, often leading to approximations rather than perfect replications of cellular behaviors observed in real biological systems. This inherent discrepancy underscores the importance of experimental validation to bridge the gap between computational predictions and biological outcomes.

The results of the MD indicate that ambenonium interacts more stably with chain B in the dimeric conformation compared with the monomeric form, as evidenced by the more negative ΔG values. This suggests that the dimeric conformation provides a more favorable environment for ambenonium binding, which is relevant for understanding the structural and functional mechanisms of this interaction. The combined analysis of the data also reveals that ambenonium significantly impacts the structural stability and interactions of the protein. While the dimer exhibits greater overall stability and reduced active site exposure, the monomer, despite being more flexible, establishes stronger interactions with the ligand. These findings are fundamental for understanding the behavior of the protein-ambenonium complex and can serve as a basis for future studies aimed at optimizing the design of molecules with higher affinity and efficacy.

The importance of this study is that we were able to demonstrate that, although in silico results suggest a potential inhibitory activity, ambenonium, at certain concentrations, may actually increase the viral replication rate due to its modulatory characteristics. This finding underscores the critical importance of biological assays to validate in silico studies and highlights the potential role of ambenonium in research.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the Github repository and can be accessed at: https://github.com/Juliana-2510/Ambenonium-main-protease/tree/main. This includes all raw and processed data used in the study. For any additional information or clarification regarding the datasets, please feel free to contact the corresponding author.

References

Hui, D. S. et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health — The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 91, 264–266 (2020).

Hu, B. et al. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 141–154 (2021).

World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-%28covid-19%29 (2024).

Fumagalli, C. et al. Clinical risk score to predict in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 10, e040729 (2020).

Cui, J., Li, F. & Shi, Z. L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 181–192 (2019).

Yang, H. & Rao, Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 685–700 (2021).

Yesudhas, D., Srivastava, A. & Gromiha, M. M. COVID-19 outbreak: History, mechanism, transmission, structural studies and therapeutics. Infection 49, 199–213 (2021).

Ullrich, S. & Nitsche, C. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 30, 127377 (2020).

Kumar, S. & Roy, V. Repurposing drugs: An empowering approach to drug discovery and development. Drug Res. 73, 481–490 (2023).

Santa-Maria, J. P., Wang, Y. & Camargo, L. M. Perspective on the challenges and opportunities of accelerating drug discovery with artificial intelligence. Front. Bioinform. 3, 1–5 (2023).

Vijayan, R. S. K. et al. Enhancing preclinical drug discovery with artificial intelligence. Drug Discov. Today 27, 967–984 (2022).

Parvathaneni, V. et al. Drug repurposing: A promising tool to accelerate the drug discovery process. Drug Discov. Today 24, 2076–2085 (2019).

Ni, L. et al. Combination of western medicine and Chinese traditional patent medicine in treating a family case of COVID-19. Front. Med. 14, 210–214 (2020).

Singh, A. K. et al. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: A systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabet. Metab. Syndr. 14, 241–246 (2020).

Dotolo, S. et al. A review on drug repurposing applicable to COVID-19. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 726–741 (2021).

Menjist, H. M., Dilnessa, T. & Jin, T. Structural basis of potential inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Front. Chem. 9, 1–11 (2021).

Niazi, S. K. & Mariam, Z. Computer-aided drug design and drug discovery: A prospective analysis. Pharmaceuticals 17, 1–22 (2024).

Vemula, D. et al. CADD, AI and ML in drug discovery: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 181, 106324 (2023).

de Souza Gomes, I. et al. Computational prediction of potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 main protease based on machine learning, docking, MM-PBSA calculations, and metadynamics. PLoS One 17, e0266729 (2022).

Blair, H. A. Correction to: Remdesivir: A review in COVID-19. Drugs 83, 1349 (2023).

Marzolini, C. et al. Prescribing nirmatrelvir-ritonavir: How to recognize and manage drug-drug interactions. Ann. Intern. Med. 175, 683–690 (2022).

Tian, F. et al. Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir compared with other antiviral drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 95, e28454 (2023).

Marques, K. C., Quaresma, J. A. S. & Falcão, L. F. M. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in “Long COVID”: pathophysiology, heart rate variability, and inflammatory markers. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1272565 (2023).

Rezapour, A. Cost-effectiveness of remdesivir for the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A systematic review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 12, 39 (2023).

Prodromos, C. & Rumschlag, T. Hydroxychloroquine is effective, and consistently so when provided early, for COVID-19: A systematic review. New Microb. New Infect. 38, 100766 (2020).

Martinuka, O. Methodological biases in observational hospital studies of COVID-19 treatment effectiveness: Pitfalls and potential. Front. Pub. Health 11, 1276898 (2024).

Breskin, A. et al. Effectiveness of remdesivir treatment protocols among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: A target trial emulation. Epidemiology 34, 365–375 (2023).

Weng, Y. L. et al. Molecular dynamics and in silico mutagenesis on the reversible inhibitor-bound SARS-CoV-2 main protease complexes reveal the role of lateral pocket in enhancing the ligand affinity. Sci. Rep. 11, 19763 (2021).

Remijn-Nelissen, L. et al. MGFA International Conference Proceedings Symptomatic pharmacological treatment of myasthenia gravis. RRNMF Neuromuscul. J. 4, 156–166 (2023).

O’Brien, J. et al. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5421–5426 (2000).

Araújo, D. B. et al. SARS-CoV-2 isolation from the first reported patients in Brazil and establishment of a coordinated task network. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 115, e200199 (2020).

Musaraat, F. et al. The anti-HIV drug nelfinavir mesylate (Viracept) is a potent inhibitor of cell fusion caused by the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein warranting further evaluation as an antiviral against COVID-19 infections. J. Med. Virol. 92, 2087–2095 (2020).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Nelson, M. T. et al. NAMD: A parallel, object-oriented molecular dynamics program. Int. J. Supercomput. Appl. High. Perform. Comput. 10, 251–268 (1996).

Huang, J. & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. "CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. comput. chem. 34(25), 2135–2145 (2013).

Kenno, V. et al. Automation of the CHARMM general force field (CGenFF) II: Assignment of bonded parameters and partial atomic charges. J. Chem. Inform. model. 52(12), 3155–3168 (2012).

Durham, E. et al. Solvent accessible surface area approximations for rapid and accurate protein structure prediction. J. mol. model. 15, 1093–1108 (2009).

Genheden, S. & Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Exp. Op. Drug Discov. 10, 449–461 (2015).

Anderson, A. C. Winning the arms race by improving drug discovery against mutating targets. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 278–288 (2013).

Holdgate, G. A., Meek, T. D. & Grimley, R. L. Mechanistic enzymology in drug discovery: A fresh perspective. Nat. Rev. 17, 705–718 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. X-ray crystallographic characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease polyprotein cleavage sites essential for viral processing and maturation. Nat. Commun. 13, 208 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Structural basis of main proteases of coronavirus bound to drug candidate PF-07304814. J. Mol. Biol. 434, 102230 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science 358, 409–412 (2020).

PyMol. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 3.0. Schrödinger, LLC.

Ferreira, J. C. & Rabeh, W. M. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of the main protease, 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) from the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11 (2020).

Yoshino, R., Yasuo, N. & Sekijima, M. Identification of key interactions between SARS-CoV-2 main protease and inhibitor drug candidates. Sci. Rep. 10, 12437 (2020).

Nashed, N. T. et al. Modulation of the monomer-dimer equilibrium and catalytic activity of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by a transition-state analog inhibitor. Commun. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03084-7 (2022).

Gilhus, N. E. et al. Generalized myasthenia gravis with acetylcholine receptor antibodies: A guide for treatment. Eur. J. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.16229 (2024).

Arsalan, A. & Younus, H. Enzymes and nanoparticles: Modulation of enzymatic activity via nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 118, 1833–1847 (2015).

Srinivasan, B. A guide to Michaelis-Menten equation: Steady state and beyond. FEBS J. 289, 6086–6098 (2021).

Nirmala, K., Manimegalai, B. & Rajendran, L. Steady-state substrate and product concentrations for non-Michaelis-Menten kinetics in an amperometric biosensor- hyperbolic function and Padé approximants method. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 15, 5682–5697 (2020).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. High-throughput kinetic studies in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 28, 102–109 (2023).

Sols, A. Multimodulation of enzyme activity. Curr. Top. Cell Regul. 19, 77–101 (1981).

Giovanetti, M. et al. Genomic epidemiology of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Brazil. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1490–1500 (2022).

Silverstein, T. P. When both Km and Vmax are altered, is the enzyme inhibited or activated?. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 47, 446–449 (2019).

Chen, W. et al. The effect of konjac glucomannan on enzyme kinetics and fluorescence spectrometry of digestive enzymes: An in vitro research from the perspective of macromolecule crowding. Food Res. Int. 184, 114247 (2024).

Silverstein, T. P. & Slade, K. Effects of macromolecular crowding on biological systems. J. Chem. Educ. 96, 2476–2487 (2019).

Ostrowska, N., Feig, M. & Trylska, J. Varying molecular interactions explain aspects of crowder-dependent enzyme function of a viral protease. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011054 (2023).

Wilcox, X. E., Chung, C. & Slade, K. M. Macromolecular crowding effects on the kinetics of opposing reactions catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 26, 100956 (2021).

Lavogina, D. et al. Revisiting the resazurin-based sensing of cellular viability: Widening the application horizon. Biosensors 12, 196 (2022).

Abir, A. H. et al. Metabolic profiling of single cells by exploiting NADH and FAD fluorescence via flow cytometry. Mol. Metab. 87, 101981 (2024).

Chandel, N. et al. Indigo production goes green: A review on opportunities and challenges of fermentative production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40, 62 (2024).

Cannon, T. M. et al. Characterization of NADH fluorescence properties under one-photon excitation with respect to temperature, pH, and binding to lactate dehydrogenase. OSA Contin. 4, 1610–1625 (2021).

Pylaev, T. E. et al. High-throughput cell optoporation system based on Au nanoparticle layers mediated by resonant irradiation for precise and controllable gene delivery. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53126-9 (2024).

Riss, T. et al. Cytotoxicity assays: In vitro methods to measure dead cells. In Assay Guidance Manual (2019).

Petiti, J., Revel, L. & Divieto, C. Standard operating procedure to optimize resazurin-based viability assays. Biosensors 14, 156 (2024).

La Monica, G. et al. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease for treatment of COVID-19: Covalent inhibitors structure–activity relationship insights and evolution perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 65, 12500–12534 (2022).

Lemoine, D. et al. Probing the ionotropic activity of glutamate GluD2 receptor in HEK cells with genetically-engineered photopharmacology. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.59026 (2020).

Bennani, H. N. Treatment of refractory myasthenia gravis by double-filtration plasmapheresis and rituximab: A case series of nine patients and literature review. J. Clin. Apher. 36, 348–363 (2020).

Hu, Z. & Kuritzkes, D. R. Altered viral fitness and drug susceptibility in HIV-1 carrying mutations that confer resistance to nonnucleoside reverse and integrase strand transfer inhibitors. J. Virol. 88, 928–976 (2014).

Lv, Z. et al. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteases for COVID-19 antiviral development. Front Chem https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.819165 (2021).

Hosseini, M. et al. Computational molecular docking and virtual screening revealed promising SARS-CoV-2 drugs. Precis. Clin. Med. 4, 1–16 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Ginkgolic acid and anacardic acid are specific covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 cysteine proteases. Cell Biosci. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-021-00564-x (2021).

Ma, C. et al. Boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 30, 678–692 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Fast and effective prediction of the absolute binding free energies of covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease and 20S proteasome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7568–7572 (2022).

Kenny, P. W. Hydrogen-bond donors in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 65(21), 14267–14275 (2022).

Karas, L. J. et al. Hydrogen bond design principles. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 10, e1477 (2020).

PubChem. Compound summary: Ambenonium. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ambenonium. Accessed (2024).

Oerlemans, R. et al. Repurposing the HCV NS3–4A protease drug boceprevir as COVID-19 therapeutics. R. Soc. Med. Chem. 12, 370–379 (2021).

Noske, G. D. et al. A Crystallographic Snapshot of SARS-CoV-2 main protease maturation process. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167118 (2021).

Fornasier, E. et al. Allostery in homodimeric SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Commun. Biol. 7, 1435 (2024).

Tuccinard, T. What is the current value of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods in drug discovery?. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 16(10), 1233–1237 (2021).

Funding

This work has been supported by funding from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). Finally, a special thanks to CT Vacinas—UFMG for the technical support in carrying out the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Juliana Ângelo de Souza, Isabela de Souza Gomes, Roberto Sousa Dias, Sérgio Oliveira de Paula, Sabrina de Azevedo Silveira. Data curation: Juliana Ângelo de Souza, Isabela de Souza Gomes, Luciana de Souza Fernandes, Luciana Ângelo de Souza, Luis Adan Flores Andrade, Sheila Cruz Araújo, Vinícius de Almeida Paiva Formal analysis: Juliana Ângelo de Souza, Roberto Sousa Dias, Sabrina de Azevedo Silveira. Funding acquisition: Flávio Guimarães da Fonseca, Sérgio Oliveira de Paula, Sabrina de Azevedo Silveira Methodology: Isabela de Souza Gomes, Luciana de Souza Fernandes, Luis Adan Flores Andrade, Roberto Sousa Dias Project administration: Sabrina de Azevedo Silveira Supervision: Leonardo Henrique França de Lima, Raquel Cardoso de Melo-Minardi, Sérgio Oliveira de Paula, Flávio Guimarães da Fonseca, Sabrina de Azevedo Silveira. Writing – original draft: Juliana Ângelo de Souza Writing – review & editing: Juliana Ângelo de Souza, Isabela de Souza Gomes, Luciana de Souza Fernandes, Luis Adan Flores Andrade, Luciana Ângelo de Souza, Sheila Cruz Araújo, Vinícius de Almeida Paiva, Leonardo Henrique França de Lima, Roberto Sousa Dias, Raquel Cardoso de Melo-Minardi, Flávio Guimarães da Fonseca, Sérgio Oliveira de Paula, Sabrina de Azevedo Silveira.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, J.Â., de Souza Gomes, I., de Souza Fernandes, L. et al. In vitro enzymatic and cell culture assays for SARS-CoV-2 main protease interaction with ambenonium. Sci Rep 15, 10606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94283-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94283-9