Abstract

Fire hazards pose significant risks to civil infrastructure, leading to concrete degradation. This study explores the development of post-fire self-healing concrete incorporating encapsulated or immobilized bacteria to restore structural integrity after fire exposure. Key challenges addressed include protecting bacteria during fire exposure and activating them post-fire. Innovative encapsulation techniques were developed to shield bacteria within concrete samples during fires, enabling their activation afterward to enhance structural strength. A finite element model simulated the time-temperature profile within the concrete and cement-based composites, replicating experimental conditions. Concrete samples underwent customized ISO 834 standard testing for a shorter period, open fire tests, and ultrasonic assessments to evaluate residual properties post-heating. A novel surface treatment was devised to protect embedded bacteria during fire exposure, proving effective in maintaining bacterial viability and enabling post-fire self-healing. A finite element model was employed to simulate the internal temperature profiles and assess the effectiveness of bacterial activation post-fire. The results confirm that the encapsulated bacteria can survive fire exposure and subsequently enhance the concrete’s mechanical properties, marking a significant advance in fire-resistant construction materials. The research establishes critical time-temperature thresholds for the feasibility of post-fire self-healing in concrete, presenting a significant advancement in fire-resistant construction materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Occurrences of fires within buildings carry significant adverse consequences, posing serious threats to both human life and property integrity1,2,3. Studies have documented the reduction in compressive strength and modulus of elasticity of concrete when exposed to elevated temperatures, with spalling being a critical issue that compromises structural stability4,5. The thermal stability of different aggregate constituents in the concrete follows this increasing order: gravel, limestone, basalt, and lightweight aggregates, with the latter remaining dimensionally stable even at 600 ºC4. The cement paste, constituting 50–60% C-S-H, 20–25% CH, and other elements such as ettringite and un-hydrated cement particles, plays a crucial role in concrete’s makeup. Also, siliceous aggregates experience crystal transformation at temperatures between 500 and 650 ºC, causing volume expansion, while non-siliceous aggregates exhibit higher heat capacity, rendering them more resilient to fire and spalling4,5.

Fire-resistant, self-healing concrete is crucial for high-rise and informal settlements, as fire incidents cause significant interface deterioration in concrete due to its heterogeneous composition3. Thermal breakdown at the nano- and micro-scale stems from the dehydration and decomposition of hydration products within the concrete structure2. Various studies have investigated the micro and nano-structural transformations that drive degradation during fire exposure and the subsequent lingering performance of concrete6,7,8,9. Earlier research has demonstrated that porous aggregates are prone to expansion, leading to pop-outs during fires10.

During a fire, the hydration products gradually lose water, leading to mass loss. Dehydration completes when the temperature reaches 500 ºC11. It’s noteworthy that decomposed calcium hydroxide could reform during cooling, but the reformation of decomposed calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) is complex and not easily achievable12. The thermal response of construction materials depends on their constituents13, and treatments involving thermo-chemical processes can enhance the properties of these materials14. Both active and passive methods have been successfully applied to develop fire-resistant construction materials15, and previous models predict the effects of fire on materials16. These factors collectively justify the possibility and necessity of treated fire-retardant concrete with superior post-fire load-bearing capacity.

Numerous concrete formulations have been explored to enhance fire resistance. Incorporating polymer fibers, for instance, has shown potential in preventing thermally induced explosive spalling, as the fibers melt around 170 ºC, establishing pathways for steam release and decreasing pore pressure within the matrix17. Earlier studies have indicated that introducing processed PET residuals can augment the fire resistance of concrete samples18.

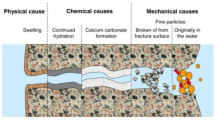

Cracks are inevitable in concrete structures, and their presence allows harmful elements like moisture, CO2, ions (Cl− and SO42−), and acids to penetrate, leading to concrete degradation19,20,21,22. Cracks can be triggered by various factors including plastic shrinkage, drying settlement, extreme environments (high temperature, high pressure, freezing), reinforcement corrosion, and mechanical loading20,22. While concrete can naturally repair cracks with widths under 2 mm, larger cracks require additional repair methods beyond concrete’s inherent capabilities23. Additionally, traditional crack closure methods like guniting and epoxy injection are time-consuming and expensive24. Recent research supports the idea that introducing self-healing mechanisms into concrete can increase the durability and service life of concrete structures.

Self-healing refers to the ability of concrete to automatically detect and repair damage. It’s a biomimetic process where self-healing concrete can detect and repair damage without manual intervention25,26,27. A successful self-healing method needs to be robust in terms of shelf life, pervasiveness, quality, reliability, versatility, and repeatability28. Self-healing mechanisms fall under categories of natural, biological, and synthetic. Natural self-healing encompasses processes like blocking cracks through water impurities, formation of calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide, and hydration of unreacted cement. Biological self-healing involves employing bacteria to induce calcite precipitation and enzymatic reactions, while synthetic methods utilize micro and macro-capsules, vascular systems, shape memory alloys, and engineered cementitious composites29. Healing agents, including mineral admixtures, chemical agents, bacterial mineral precipitation, adhesive polymers, and fibers, can be categorized into three types: polymeric (e.g., dicyclopentadiene, methyl methacrylate), biological (e.g., Bacillus bacteria, fungi), and inorganic (e.g., sodium silicate, magnesium oxide)25,29,30,31,32.

Microbial autogenous self-healing involves adding inactive bacteria spores, nutrients, and precursors to the concrete mix. When cracks appear, the dormant bacteria spores activate and grow with water, oxygen, and nutrients. This leads to the formation of calcium carbonate, which seals the cracks through metabolic activity19,21,33. Autonomous healing is an engineered process using external agents like expansive agents, fly ash, etc., to promote self-healing30,34. This method can repair wider cracks more quickly than autogenous self-healing. Autonomous healing includes intrinsic healing (using fibers, polymers, and minerals to reduce crack width), the vascular approach (using hollow tubes to transport healing agents), and capsule encapsulation25. Encapsulation is crucial to protect healing agents and bacteria. Common encapsulation methods include glass, ceramics, micro-encapsulation, and immobilization with lightweight aggregates27. Chemical encapsulation involves embedding chemicals in microcapsules triggered by stress or moisture35. Encapsulation of bacteria spores can be done with porous carriers, polymers, or low alkaline materials19.

Biological healing is often combined with fibers, capsules, and other methods36. Healing efficiency is influenced by various factors, including the type of cement, environmental conditions, availability of nutrients, pH levels, moisture content, temperature, bacterial strain and concentration, and the nature of pre-cracking25,37,38. Chemical healing is generally more efficient than microbial healing, leading to hybrid approaches24. Incorporating bacteria with fibers enhances self-healing efficiency, mechanical properties, and water resistance39. Other methods, like bio-cement, use calcium carbonate produced by urea hydrolysis and mineral precursors to repair microcracks40,41. Studies have reported successful post-fire healing with biological and chemical methods42,43. Using waste materials like fly ash or e-waste aggregates improves self-healing44,45.

Despite advancements in fire-resistant concrete and self-healing technologies, significant gaps remain in post-fire recovery of structural properties, as current methods focus on crack healing under normal conditions and fail to address high-temperature degradation of bacteria and healing agents. This study aims to bridge this gap by introducing an innovative approach using encapsulation and immobilization techniques to protect bacteria during fire exposure and enable post-fire activation, paving the way for effective biological healing in extreme conditions. The proposed finite element modeling and experimental validation provide a comprehensive understanding of the time-temperature thresholds required for bacterial survival and activation in fire-damaged concrete. This research introduces the integration of post-fire self-healing capabilities into fire-resistant construction materials, offering a novel solution that enhances both the durability and safety of buildings subjected to fire hazards, setting it apart from existing fire-retardant and self-healing technologies.

Materials and methods

Cubical samples of reference concrete and cement-based composites (CBC) incorporating self-healing materials (a mixture of 70% Bacillus subtilis and 30% calcium lactate by volume) at proportions of 10%, 15%, and 20% were cast using wooden molds. The strain used in this study is Bacillus subtilis, chosen for its remarkable ability to survive in extreme environmental conditions, including high temperatures. This bacterium is well-documented for its role in calcium carbonate precipitation, a key process in the self-healing mechanism. Its resilience, coupled with its capacity to metabolize calcium lactate and produce calcium carbonate, makes it a suitable candidate for enhancing the post-fire self-healing capabilities of concrete. The concrete mix design used was of M40 grade. The composition of the samples is provided in Table 1. Physical properties of the concrete and CBC samples were evaluated using standard ASTM test procedures18. The rheological behavior in the fresh state was assessed using slump and Ve-Be consistometer tests46. After 24 h, the samples were extracted from molds and cured in water at room temperature (26–30 ºC) for 28 days. Table 2 outlines sample composition and designations for each test type.

To ensure the survival and functionality of Bacillus subtilis during and after fire exposure, a multi-faceted encapsulation approach was employed. Figure 1 highlights two effective methods each for immobilization and encapsulation used in producing CBC samples, emphasizing these successes amid several unreported attempts. Bacteria at varying proportions (10%, 15%, and 20% by volume) were immobilized within expanded clay and porous aggregates. Expanded clay and porous aggregates were infused with bacterial solutions and coated with a cement paste layer. A water-based bacterial solution, prepared in equal proportions by volume, was absorbed by the expanded clay and porous aggregates over 24 h. These materials were then coated with cement paste before being incorporated into the concrete samples. This setup acted as a thermal barrier, reducing heat transfer and maintaining internal temperatures below the bacterial survival threshold (~ 70 °C) during fire exposure.

The first encapsulation method includes gelatin capsules filled with a bacterial solution (70%) and calcium lactate (30%) coated with cement paste to enhance thermal protection (as shown in Fig. 1) prior to concrete inclusion. Similarly, the carbon fabric ball was filled with bacteria and calcium lactate and coated before concrete preparation. During the fire, the water content within the cement paste evaporated, forming microcracks in the coating. These microcracks served a dual purpose: they insulated the bacteria during the fire and facilitated bacterial activation post-fire by allowing the ingress of moisture and CO2, critical for calcium carbonate precipitation. Carbon fiber bacteria balls offered an additional encapsulation strategy, leveraging the superior thermal resistance of carbon fibers. These balls were also coated with cement paste to further enhance insulation and ensure bacterial viability during fire exposure.

Finally, surface treatments were applied to the concrete samples using fire-resistant coatings. A carbon-rich residue derived from controlled heating of burnt plastic and a cow-dung-based material inspired by traditional fireproofing techniques were tested. The cow-dung coating solution was prepared by mixing dried and finely ground cow-dung powder with water in a 1:1 ratio by volume. This mixture was thoroughly stirred to achieve a uniform, slurry-like consistency suitable for application. The prepared solution was then applied to the surface of the concrete samples using a brush to ensure an even coat across all exposed surfaces. After the application, the coated samples were left to air-dry overnight at room temperature to allow the coating to set and adhere to the substrate.

The cow-dung-based coating provides a fire-resistant layer by forming a carbon-rich residue upon exposure to heat. This residue acts as an insulating barrier, reducing heat transfer into the concrete and protecting the encapsulated bacteria and the structural integrity of the samples during fire exposure. This method draws inspiration from traditional practices of applying cow-dung paste to floors and walls to protect them from fire and thermal damage. While rooted in traditional knowledge, this approach has been adapted and tested in the study for its scientific merit and practical utility in enhancing the fire resistance and self-healing properties of concrete. This method draws inspiration from an age-old practice of safeguarding building surfaces from fire. Historically, treated cow-dung paste was applied to floors to protect them during fire use. This practice minimized fire-induced damage. However, there’s no documented scientific evidence in literature about this ancient fire protection technique. This aspect falls outside the scope of the current study as well.

These coatings acted as an external shield, reducing thermal conductivity and protecting the encapsulated bacteria. This combination of encapsulation techniques and surface treatment effectively preserved bacterial viability during fire exposure and optimized their activation post-fire, enabling the calcium carbonate precipitation necessary for self-healing. The self-healing mechanism relies on the metabolic activity of Bacillus subtilis to precipitate calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) within cracks formed due to fire-induced damage. Upon activation in the presence of moisture and CO2 post-fire, the bacteria metabolize calcium lactate, releasing calcium ions (Ca2+) and carbonate ions (CO22−). These ions combine to form calcium carbonate, which crystallizes within cracks, effectively sealing them and restoring structural integrity. Table 3 outlines the experiment’s sample details. Untreated and treated samples underwent ISO 834 and open fire heating tests.

-

T1: Average temperature at the center of the bottom face.

-

T2, T3, T4, T5: The four side faces.

-

T6: The top face of each cube.

Commonly, fire effects on concrete samples are simulated using furnaces. Yet, experimental measurement of temperature changes, thermal stresses, and deformation within concrete components during fire is challenging. A Finite Element Method (FEM) model was developed to predict temperature and stresses across concrete samples during fire. The present study utilized a computationally efficient 2D model in ANSYS WB 2019R1. The ISO-834 fire curves guided heating of the concrete sample in the model. This 2D approach is adept at explaining interfacial micromechanics. Within the FE model, coarse aggregates and encapsulation (gelatin) were integrated into the mortar matrix (depicted in Fig. 3a). A thermo-structural coupled field simulation assessed thermal loading’s effect on concrete components. The model applied transient thermal boundary conditions according to ISO-834 fire curves (as shown in Fig. 3b) to the concrete sample. These outcomes facilitated temperature determination within the sample, gauging bacteria survivability during fire. The simulation adopted a 3-hour (ISO-834 recommended) fire duration to identify optimal ways of including bacteria in CBCs for sustained survival during prolonged fires. To ensure bacteria survival, their temperature was maintained below 70ºC.

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental results, all procedures were carried out under controlled laboratory conditions following relevant ASTM standards for sample preparation, testing, and analysis. The encapsulation and immobilization techniques were carefully selected based on preliminary studies that identified the optimal conditions for bacterial survival during and after fire exposure. Each experimental setup, including the fire tests and ultrasonic assessments, was replicated a minimum of three times to confirm consistency and minimize random errors. Calibration of the equipment, such as the ultrasonic test devices and finite element modeling parameters, was performed prior to each test to ensure accuracy. Additionally, the chosen fire testing approach was validated against standard ISO 834 fire curves to simulate real-world fire scenarios. Statistical analyses, including error margins and data validation methods, were employed to assess the significance of the results. Detailed protocols for each step are available upon request to further support the reproducibility of the findings.

Results and discussion: experiments

Sample weights (Table 4) under natural, submerged, and saturated conditions provide insights into density and pore structure. The average percentage decrease in weight for submerged CC samples and the percentage increase for saturated CC samples relative to their natural weights are reported. Water submerged CCs saw average reductions of 43.04% (ECC_CP_10) to 47.21% (CFBB_CP_20). Saturated CCs witnessed average weight increments of 1.52% (EC_20) to 2.04% (RA_10). Similar trends held for CBCs: water submerged CBCs showed reductions of 45.75% (ECC_CP_10) to 46.81% (RA_20), while saturated CBCs had increments of 1.39% (CFBB_20) to 2.04% (RA_10). Overall, submerged samples lost 43–48% weight, while saturated samples gained 1-2.5%. CC density dropped due to substitutions (Table 5), with decreases of 2.33% (ECC_CP_10) to 7.17% (CFBB_CP_15) relative to reference samples, attributed to increased porosity.

Additionally, to assess workability and consistency, the slump and Ve-Be tests are employed. Results confirm suitable workability and water-cement ratio for both concrete and CBCs. Ve-Be test outcomes for all combinations, with CFBB_10 recording the longest time (6.4 s) and CC the shortest (5.4 s).

Figure 4a–b displays the compressive stress-strain curves for the samples, utilizing average values over 7 days and 28 days of curing. The corresponding average percentage reductions in compression strength after 28 days of curing, at substitution levels of 10%, 15%, and 20%, are as follows: ECC_CP (6.11%, 8.96%, and 13.36%), EC (8.19%, 11.28%, and 15.72%), CFBB (3.26%, 6.52%, and 11.12%), CFBB_CP (4.68%, 7.94%, and 12.14%), GC_CP (9.25%, 12.87%, and 17.43%), and RA (14.22%, 17.80%, and 21.16%). These percentages are in comparison to CC. Furthermore, Fig. 5 illustrates the rise in compressive strength between the 7-day and 28-day water curing periods. The increase in compressive strength reaches a minimum of 58.31% for ECC_CP_10 and a maximum of 66.49% for RA_20 after 28 days of curing, in contrast to the 7-day curing period.

Figure 6a–e provides confirmation that the stress-strain correlation is contingent upon the temperature of fire exposure. As the temperature increases, there is a corresponding decline in ultimate stresses. The elevation in temperature leads to a reduction in the compressive strength across all samples. This phenomenon can be attributed to factors such as micro-cracking and internal stresses caused by aggregate expansion due to physical and chemical transformations within the concrete during heating. At 200 °C, the decline in compressive strength is linked to the loss of free and adsorbed water. Beyond 400 °C, the reduction in strength results from dehydration and the breakdown of hydration products. Moreover, temperatures exceeding 600 °C led to a loss of stiffness due to the decomposition of calcium silicate hydrate gel, while temperatures surpassing 800 °C further decrease strength due to the decomposition of calcium carbonate3,5,14. Figure 7 (a-d) depicts the average degradation in compressive strength. It encompasses untreated samples, treated samples, self-healed samples, as well as treated and self-healed samples without fire exposure, subsequent to fire exposure at temperatures of 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C for a duration of 60 min, along with the open fire test. Notably, the treated and self-healed CFBB samples exhibit the most favorable compressive strength outcome, while CC samples displayed the greatest post-fire exposure deterioration.

Percentage variations in compressive strength are presented for untreated samples (Fig. 8), treated samples (Fig. 9), self-healed samples (Fig. 10), and samples that were both treated and self-healed (Fig. 11) at exposure levels of 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, 800 °C, and open fire. The application of treatments has yielded positive enhancements in the residual compressive strength of both concrete and CBC samples. Table 6 presents the percentage advancements in residual compressive strength attributed to treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples, in comparison to untreated samples. The most notable improvement in residual compressive strength is observed in the case of treated and self-healed samples. Notably, both treated and exclusively self-healed samples have effectively mitigated the decline in residual compressive strength. This reduction in strength degradation can be attributed to the fire protection layer resulting from the treatments applied to CC and CBC samples. The presence of burnt carbon-rich and fire-resistant components within these coatings has proven effective in countering the effects of the tested fire duration and exposure intensity.

The P-wave velocity measurements for both CC and treated samples were conducted before and after exposure to fire temperatures of 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C for 60 min, following the BS 1881 standard. This was achieved using a pair of P-wave transducers (200 V) and a pulse receiver (52 kHz). For P-wave assessment, 20 indirect measurements were taken on the surface of each sample. The transmitters and transducers were positioned at eight distinct points along the sample’s length to determine the average P-wave velocity. In a similar vein, S-wave velocity was evaluated through 29 direct measurements using the scanning image method on each sample’s surface.

In the absence of fire exposure and treatment, the ranges for P-wave and S-wave velocities were observed as 3960 –2946 m/s and 2230 –1580 m/s, respectively. For untreated samples without fire, the P-wave and S-wave velocities ranged from 3280 –2476 m/s and 1972 –1480 m/s after exposure to 200 °C, 2960 –2270 m/s and 1872 –1319 m/s after exposure to 400 °C, 2380 –1726 m/s and 1572 –1010 m/s after exposure to 600 °C, and 2064 –1340 m/s and 1332 –800 m/s after exposure to 800 °C. Treated samples showed similar patterns, with some differences in velocity ranges due to treatment effects. For self-healed samples, the velocity ranges were 4230 –3096 m/s for P-wave and 2374 –1650 m/s for S-wave in the absence of fire, and these values decreased with increasing fire exposure. Treated and self-healed samples exhibited the highest velocities, particularly after exposure to higher fire temperatures, with ranges of 3530 –2700 m/s for P-wave and 2150 –1588 m/s for S-wave after 800 °C exposure.

Open fire exposure caused notable shifts in velocity ranges. For untreated samples, P-wave velocities ranged from 2144 to 1326 m/s, and S-wave velocities ranged from 1340 to 820 m/s. In contrast, treated and self-healed samples exhibited improved velocity ranges of 2520 to 1710 m/s for P-waves and 1510 to 1010 m/s for S-waves. Overall, P-wave and S-wave velocities varied based on temperature exposure, treatment, and sample type, displaying consistent trends in behavior. Table S1, Table S2, Table S3, and Table S4 (see Appendix) provide a comprehensive summary of comparisons, including density, Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, dynamic modulus, P-wave and S-wave velocities, and dynamic moduli derived from these velocities for untreated, treated, self-healed, and combined treated and self-healed samples. These tables also detail error ranges for dynamic moduli derived from P-wave and S-wave velocities compared to static test results, with error percentages increasing significantly under prolonged fire exposure.

Comparatively, composites exhibit lower densities than concrete due to their lightweight constituents. Untreated samples show the broadest range of densities, with concrete and CFBB_CP_20 composite displaying the highest and lowest values, respectively. This trend persists across treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples, with ECC_CP_10 and CFBB_CP_20 composites having the greatest and least densities, respectively. Composites also show a noticeable decrease in Young’s modulus compared to concrete, attributable to substitutions in their constituents. Both static (ED) and ultrasonic tests (EDP and EDS) reveal that untreated concrete and RA_20 composite samples have the highest and lowest dynamic Young’s modulus values, respectively, while CFBB_10 and RA_20 composites exhibit these extremes across treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples. Additionally, CFBB_10 and RA_20 composites show the maximum and minimum average P-wave and S-wave velocities, respectively, consistent across all sample conditions. Furthermore, the most significant deviations in dynamic Young’s modulus values from static and ultrasonic tests occur in RA_20 and CFBB_10 composites for both untreated and treated samples, while RA_20 and CFBB_CP_15 composites display these extremes for self-healed samples, and RA_20 and CFBB_CP_10 for treated and self-healed samples. These observations are detailed in Table S5, Table S6, Table S7, and Table S8 (see Appendix) and Table S9, Table S10, Table S11, and Table S12 (see Appendix) for samples at 200 °C and 400 °C fire conditions, respectively.

Similar to non-fire conditions, a parallel trend is observed in the densities of composites compared to concrete under fire conditions. The highest and lowest densities are recorded in concrete and CFBB_CP_20 composites for untreated samples, while ECC_CP_10 and CFBB_CP_20 composites present these extremes for treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples. In terms of dynamic Young’s modulus during both static and ultrasonic tests, the highest and lowest values are observed in concrete and RA_20 composite for untreated samples and in CFBB_10 and RA_20 composites for treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples. Maximum and minimum average values of P-wave and S-wave velocities are seen in CFBB_10 and RA_20 composites respectively, across all conditions. Moreover, the most significant deviations in dynamic Young’s modulus values from static and ultrasonic tests are observed in untreated samples, primarily in RA_20 composite and concrete. For treated samples, these extremes occur in RA_15 and CFBB_CP_10 composites, while for self-healed samples, they are most pronounced in RA_20 and CFBB_10 composites. For treated and self-healed samples, the deviations are most notable in RA_20 and CFBB_15 composites. Table S13, Table S14, Table S15, and Table S16 (see Appendix) and Table S17, Table S18, Table S19, and Table S20 (see Appendix) provide a comparison of properties during static and ultrasonic tests for samples at 600 °C and 800 °C fire conditions, respectively.

Table S21, Table S22, Table S23, and Table S24 (see Appendix) shows comparison of properties during static and ultrasonic tests for samples at open fire test condition. Untreated concrete had the highest density, CFBB_CP_20 the lowest. In treated, self-healed, and treated & self-healed samples, ECC_CP_10 and CFBB_CP_20 showed highest and lowest densities, respectively. Dynamic Young’s modulus (ED, EDP, EDS) peaked in untreated concrete and CFBB_10 (treated categories), lowest in RA_20.

Maximum P-wave and S-wave velocities occurred in untreated concrete and CFBB_10 (treated categories), with minimum velocities in RA_20 composites.

Greatest modulus deviations (ED vs. EDP and EDS) appeared in RA_20 composites across untreated, treated, and treated & self-healed categories, with smallest deviations in untreated concrete and CFBB_CP_10 composites.

Under fire and no-fire conditions, highest densities were noted in untreated concrete and ECC_CP composites, while CFBB and CFBB_CP consistently showed lowest densities. Modulus values (ED, EDP, EDS) remained highest in concrete and ECC_CP composites, lowest in RA composites across conditions. Maximum velocities appeared in CFBB, lowest in RA composites. Largest deviations were consistently seen in RA and GC_CP composites, smallest in untreated concrete, ECC_CP, CFBB, and CFBB_CP composites.

The application of fire-retardant treatments, such as traditional cow-dung-based coatings, has significantly contributed to the preservation of compressive strength across varying fire temperatures. These treatments act as thermal barriers, reducing heat transfer to the concrete matrix and encapsulated bacteria. By maintaining lower internal temperatures during fire exposure, the fire-retardant layers enhance bacterial survivability, enabling effective calcium carbonate precipitation and crack healing post-fire. Experimental results indicate that samples treated with fire-retardant coatings exhibit higher residual compressive strength, particularly at moderate fire temperatures (200 °C to 600 °C), compared to untreated samples. This demonstrates the synergistic role of fire-retardant coatings and encapsulation techniques in mitigating thermal damage and preserving structural integrity.

Calcium carbonate precipitation, a key indicator of bacterial activation and functionality, was evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Post-fire concrete samples incorporating various encapsulation techniques, including ECC_CP_15, EC_15, CFBB_15, CFBB_CP_15, GC_CP_15, and RA_15, were subjected to SEM analysis to study the morphology and distribution of the precipitates within microcracks and voids.

The SEM images (Fig. 12) revealed distinct crystal formations within the microcracks of treated samples, characteristic of calcium carbonate deposits. The morphology of these crystals varied depending on the encapsulation method and fire exposure conditions. For samples exposed to temperatures up to 400 °C, dense, well-formed calcite crystals were observed, demonstrating robust bacterial activity and efficient precipitation. At 600 °C, smaller and more irregular crystal structures were detected, indicating partial bacterial viability and reduced metabolic activity due to the thermal stress.

In the CFBB_15 and CFBB_CP_15 samples, the SEM images displayed higher surface coverage with calcium carbonate crystals compared to other systems, suggesting superior protection provided by carbon fiber encapsulation. The GC_CP_15 samples showed localized crystal formation around microcracks, further validating the effectiveness of gelatin capsules coated with cement paste in preserving bacterial viability.

In contrast, samples exposed to temperatures beyond 600 °C showed limited or no visible calcium carbonate deposits, correlating with the expected thermal degradation of bacterial spores and a lack of metabolic activity. The absence of significant crystal structures in these samples further highlights the critical temperature thresholds for bacterial survival.

The SEM analysis not only confirmed the presence of calcium carbonate precipitates but also provided insights into the performance of various encapsulation techniques under different fire exposure conditions. These findings underscore the role of encapsulation in maintaining bacterial viability and enabling effective self-healing in fire-damaged concrete.

To enhance the robustness of the findings, advanced statistical analyses were conducted on the experimental data. Standard deviations and confidence intervals were calculated for all measured properties, including compressive strength and residual properties across different encapsulation percentages and fire exposure conditions. The mean compressive strength, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each combination of encapsulation percentage (10%, 15%, and 20%) and fire temperatures (200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C). Results indicated a consistent decline in compressive strength with increasing fire temperature, while higher encapsulation percentages demonstrated better retention of strength. For instance, at 200 °C, the mean compressive strength for samples with 10%, 15%, and 20% encapsulation was 42.12 MPa, 39.56 MPa, and 36.78 MPa, respectively. At 800 °C, the values dropped to 29.78 MPa, 27.45 MPa, and 24.91 MPa, highlighting the protective effect of encapsulation.

The statistical significance of observed differences was determined using one-way ANOVA at a 95% confidence level. One-way ANOVA was performed to assess the statistical significance of differences in compressive strength across fire temperature groups. The test yielded a p-value < 0.05, indicating that fire temperature had a statistically significant effect on compressive strength. This confirms that thermal exposure is a critical determinant of concrete performance. The ANOVA results revealed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in compressive strength between samples with different encapsulation percentages (10%, 15%, and 20%) and across fire temperatures (200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C). Interaction effects between encapsulation percentages and fire temperatures were also significant, indicating that the degree of encapsulation influenced the thermal response of the samples.

To further explore the relationships between the variables, a regression analysis was conducted using compressive strength as the dependent variable and encapsulation percentage, fire temperature, and their interaction as independent variables. The regression model is given in Eq. (1).

Where: β0: 50.85; The intercept, representing the baseline compressive strength without encapsulation or fire exposure. β1: 0.35; The coefficient for Encapsulation Percentage, representing its direct effect on compressive strength. β2: − 0.05; The coefficient for Fire Temperature, representing its direct effect on compressive strength. β3: − 0.001; The interaction coefficient, showing how the effect of Fire Temperature on compressive strength is moderated by Encapsulation Percentage.

The regression model showed a strong correlation (R2 > 0.9), indicating that these variables explain most of the observed variance in compressive strength. The model highlighted a non-linear decline in compressive strength with increasing fire temperature, moderated by higher encapsulation percentages, which mitigated strength loss.

The statistical analysis of the experimental data underscores the effectiveness of the advanced encapsulation and treatment methods employed in this study, revealing a significant enhancement in the residual compressive strength of treated concrete samples compared to their untreated counterparts (p < 0.05). Specifically, the compressive strength of the treated and self-healed samples, particularly those with higher encapsulation percentages of CFBB and ECC composites, demonstrated remarkable resilience following exposure to fire. The CFBB_CP_20 and ECC_CP_20 composites exhibited the highest post-fire compressive strengths, suggesting that the combination of encapsulated bacteria and carbon-rich protective coatings plays a crucial role in mitigating fire-induced degradation.

This enhancement can be attributed to the synergistic effects of bacterial encapsulation and the fire-resistant coatings applied to the concrete samples. The encapsulation process effectively insulated the bacteria from the extreme temperatures encountered during fire exposure, preserving their viability and enabling post-fire self-healing through the bio-precipitation of calcium carbonate. This bio-mineralization process contributed to the closure of micro-cracks that formed due to thermal stress, thereby restoring a significant portion of the concrete’s structural integrity. Additionally, the carbon-rich coatings, derived from waste materials, acted as thermal barriers, reducing the internal temperature gradient and preventing the extensive thermal decomposition of C-S-H gel and calcium hydroxide, which are critical to maintaining the strength and stability of the concrete matrix.

Further validation of these findings is provided by the P-wave and S-wave velocity measurements, which indicated less pronounced reductions in treated samples compared to untreated ones. The treated and self-healed samples maintained higher wave velocities, reflecting their superior structural integrity and reduced porosity post-fire. The dynamic modulus values derived from these ultrasonic tests were in close agreement with the static modulus values, confirming that the encapsulation and treatment techniques not only preserved bacterial functionality but also enhanced the overall fire resistance of the concrete. This improved performance is particularly significant in high-temperature environments, where traditional concrete formulations typically suffer from severe strength loss. The incorporation of self-healing bacterial agents, therefore, presents a promising approach to extending the durability and safety of fire-exposed structures, offering a novel solution that integrates fire resistance with self-repair capabilities.

Results and discussion: FE analysis

The fire exposure duration significantly impacts the degradation of properties in cementitious materials. Also, the level of degradation varies across dimension of cementitious materials. This behavior is attributed to the fact that when exposed to fire for shorter durations, the core of the sample may not achieve maximum temperatures. The FE model predicts the temperature variation, thermal stress, and deformation for 30 min of fire exposure. This analysis was conducted to know the temperature across thickness of the samples so that encapsulated/immoblised bacteria survival can be predicted. Figure 13a presents the results of FE analysis after 30 min of transient thermal simulation. It can be seen that the maximum temperature of concrete reaches 1154.70 ℃ after 30 min of fire exposure. Figure 13b presents the increase in maximum temperature due to fire exposure. The initial steep rise in the temperature is attributed to the fast propagation of temperature on the outer surface of the concrete sample. The heat flux contours and corresponding curves in the concrete sample are presented in Fig. 13c. The maximum heat flux is achieved in the initial period of fire exposure. As expected, after 30 min of fire exposure, the maximum heat flux of 5.44 × 10− 4 W/mm2 is achieved at the four edges of the model. Figure 13 (d) presents the variation of maximum heat flux in the FE model with time. The highest heat flux of 1.50 × 10− 1 W/mm2 was observed in the model at the initial time, with subsequent reduction at the end of 30 min.

Figure 14 presents the von Mises stress contour in the concrete sample due to fire exposure. As expected, the stress concentration occurs at the aggregate/gelatine encapsulation-concrete interface. The interaction between coarse aggregate/gelatine encapsulations and concrete is evident from the figure in the form of a stress band with a maximum stress of 51.46 MPa. The formation of the stress band is also related to the shear banding due to fire exposure. This observation is attributed to the relative difference between their thermo-structural properties.

Figure 15a and b present the FE model for concrete samples embedded with coarse aggregate and wood particles and the corresponding input ISO-834 fire curve, respectively. The FE model was subjected to the ISO-834 fire curve from three boundary conditions: all four sides, three sides, and one side similar to experiments.

Figure 16a–c presents the transient temperature contours in the FE model for these boundary conditions. Figure 16a illustrates the temperature distribution contours in the FE model for the three boundary conditions under transient thermal analysis. After 10 min of fire exposure, the minimum temperature was 37.99℃ when the model was exposed from all four sides. When exposed from three and one sides, the minimum temperature values were observed to be 26.63 ℃ and 22 ℃, respectively (see Fig. 16c,d). Interestingly, the maximum temperature in the concrete sample was 2222.7 ℃ under all three boundary conditions. The heat flux distribution contours in the FE model for the three boundary conditions under transient thermal analysis are presented in Fig. 17a–c. The minimum heat flux was 0.119 W/m2 when the model was exposed from all four sides. This value decreased to 0.113 W/m2 and 0.082 W/m2 when the samples were exposed from three and one sides. The von Mises stress contours in the concrete samples are presented in Fig. 18a–c. It can be noticed that the highest stress concentration occurs at the concrete-aggregate interface due to the differential mechanical properties. The thermal loading-induced deformation contours under three boundary conditions are presented in Fig. 19a–c. The highest total deformation was observed in the sample when all four sides were subjected to fire exposure. Figure 20a presents the FE model employed in the present investigation showing CBC with gelatine capsules. Figure 20b illustrates the input ISO – 834 fire curve.

The 2D FEM used in this study, while computationally efficient, has inherent limitations in representing complex 3D concrete geometries, particularly in capturing out-of-plane heat transfer and localized effects of inclusions like EC, CFBB, and GC. To mitigate these limitations, the model was calibrated using experimental data, and thermal and mechanical properties of the inclusions were homogenized to approximate their collective impact. Realistic boundary conditions were employed to simulate thermal exposure accurately. Despite these efforts, future work will involve 3D FEM to provide more detailed and high-fidelity simulations of thermal and mechanical behavior under fire exposure47.

Further, a body-centered unit cell of dimensions 5 × 5 × 5 mm³ was employed to study the shielding effect of cement paste on the bacteria-treated EC-loaded samples, with homogenization applied to ensure consistency, as the experimental sample size was 150 mm³. Figure 21 shows the FE models employed for modelling EC_CBC_10 and ECC_CP_10 concrete samples. The computationally efficient symmetric 3D model was developed using ANSYS WB 2019R2. The 3D model can obtain the interfacial thermal interaction between the constituents. The mesh convergence study implies obtaining true solution of partial differential equations with a finer mesh in the spatial domain. It involves sequentially reducing the element size and analyzing the impact on the solution accuracy and computational efficiency. A finer mesh provides a more accurate solution due to improved sampling of the design domain but with a lower computational efficiency. The designers must strike the optimal balance between the solution’s accuracy and computational efficiency. A mesh convergence study was conducted to determine the optimal mesh size to achieve the highest computational efficiency without much loss of accuracy. Figure 22a–f presents the results of the mesh independence study displaying the finer mesh with a lower element size. The maximum highest total heat flux and maximum and minimum temperatures in the FE model for each element size are plotted in Fig. 22g and h. The plateauing of the heat flux and temperature curves can be seen after 94,250 elements, indicating the mesh independence being achieved. As a result, the FE model was discretized with 94,250 finite elements to ensure mesh independence.

The FE model was subjected to a transient thermal analysis to predict temperature within the unit cell during fire exposure. All six sides of the FE models were subjected to ISO-834 fire curves identical to the experimental boundary conditions for 30 min. The initial, minimum and maximum time steps were set to 3.515 × 10− 2 s, 3.515 × 10− 3 and 0.3515 s, respectively, to capture the temperatures accurately. The time integration was set to ‘ON’ to account for the time-dependent variation of temperatures. The automatic time stepping option was set to ‘ON’ to increase computational efficiency by adjusting the time interval according to the simulation requirements. Table 7 gives the thermal properties of the constituents used in the analysis.

Figure 23 presents the temperature contours in the FE model cross-sections for EC_CBC_10 and EC_CP_10 concrete samples under the ISO-834 fire curve at various simulation time steps. At t = 0.5 s, the maximum temperatures in the corner EC particles were 345.08 ℃ in both samples. The minimum temperatures recorded at the central particles were 294.84 ℃ and 293.38 ℃ for EC_CBC_10 and ECC_CP_10 concrete samples, respectively (see Fig. 23a,b). This similarity implies that after 0.5 s, the fire exposure did not cause any noticeable temperature rise in the central particle. Figure 23c and d depict the temperature contours in both the samples at the end of 1.5 s. In this case, the maximum temperatures recorded in the central particle increased to 320.32 ℃ and 303.88 ℃ in EC_CBC_10 and ECC_CP_10 samples, respectively (Fig. 23c,d). At the end of 5 s, these temperatures rose to 496.32 ℃ and 450.81 ℃ respectively (Fig. 23e,f). At t = 15 s, the maximum temperature increased to 689.1 ℃ for the EC_CBC_10 sample and 676.64 ℃ for the ECC_CP_10 sample (Fig. 23g,h). Due to cement paste protection, EC particle temperatures at each time step are lower in the ECC_CP_10 sample.

Figure 24 presents the variation of temperature along the path 1–2. The corresponding terminal temperatures (at points 1 and 2) are depicted via bar graphs in Fig. 24a and b. The increase in temperature when one moves from points 1 to 2 can be noticed from these figures. Figure 24a shows a slight temperature difference at t = 0.5 s. The temperature difference increases with time, attaining a peak value followed by a gradual reduction up to t = 120 s (see Fig. 24b–f). As the fire curve heats the cement paste, its lower specific heat capacity slows the core temperature increase. The FE model and EC particle reach a steady state over time, reducing the temperature difference at points 1 and 2 to a negligible value. This behaviour is also evident in Fig. 25, depicting the variation of temperature difference between temperatures at points 1 and 2. A peak temperature difference of 37.19 K and 42.73 K is observed at t = 5 s for EC_CBC_10 and EC_CP_10 samples, respectively. The EC_CP_10 sample displayed a higher temperature difference than the EC_CP_10 samples.

It is interesting to note that the rate of temperature increase follows the ISO-834 input fire curve. However, the slower rate of temperature rise is evident in Fig. 26, especially in the initial 15 s. The slower rate of temperature increase is again attributed to the cement paste applied to the EC.

The FE analysis conducted in this study closely aligns with experimental results, validating the model’s accuracy in simulating the thermo-mechanical behavior of concrete under fire conditions. The FE model effectively replicated the thermal gradients, stress distributions, and critical thermal events such as the decomposition of calcium hydroxide and degradation of C-S-H gel, which corresponded to observed losses in compressive strength and P-wave/S-wave velocities.

Notably, the FE simulations revealed that encapsulated bacteria within the CBC samples were exposed to temperatures below the critical 70 °C survival threshold, supporting the observed post-fire self-healing via calcium carbonate bio-precipitation. The analysis also demonstrated that carbon-rich coatings significantly delayed heat penetration, protecting the bacteria and enhancing post-fire strength, especially in CFBB_CP_20 and ECC_CP_20 samples.

Further, the model identified fire-induced micro-cracking primarily at aggregate-matrix interfaces, where activated bacteria effectively initiated healing, contrasting with more extensive damage in CC lacking such agents. The FE analysis also suggested that self-healing improved long-term durability and resistance to subsequent thermal and mechanical stresses, enhancing the lifespan of fire-exposed CBC structures.

Overall, the FE analysis not only confirmed experimental observations but also provided deeper insights into the role of advanced materials, such as encapsulated bacteria and protective coatings, in developing resilient, self-healing concrete composites. This modeling approach establishes a foundation for optimizing self-healing formulations and advancing the safety of fire-exposed infrastructure.

Further, the sensitivity analysis of the model parameters was performed through design of experiments (DoE) designed to enhance the confidence in model accuracy. The study involved three input and response variables to obtain different values of response parameters by combining various input parameters as per the Box-Behnken design (BBD). EC density, specific heat, and thermal conductivity were taken as input, and minimum and maximum temperatures along the path 1–2 and total thermal flux were selected as response variables. Table 8 presents these input and response variables with their identification codes and initial values. A total of 14 numerical experiments were performed on the FE models corresponding to the samples EC_CBC_10 and ECC_CP_10. The dataset obtained was employed to plot the main effects chart to visualize the mean response in the response variable at different input variable levels. It helps explain how each factor affects the response variable independently.

Figure 27a–c depicts the main effects plot for the response variables (density, specific heat, and total heat flux) corresponding to the various input variable levels for EC_CBC_10. The main effects plot for minimum temperature and response variable shows that increasing EC density and specific heat decreases the minimum temperature. Contrarily, an increase in the thermal conductivity leads to a steep rise in the minimum temperature. The steep slope of the line indicates a strong effect of density on the minimum temperature. A similar effect of these independent variables can be noticed in the main effects plot for maximum temperature (see Fig. 27b). Contrarily, as indicated by the straight line with a slight slope, the thermal conductivity has an insignificant effect on the maximum temperature. Figure 27c represents the main effects plot for total heat flux, depicting a strong relation between the input and response variables manifested by a positive slope.

Figure 28a–c depicts the main effects plot for the response variables (density, specific heat, and total heat flux) corresponding to the various input variable levels for ECC_CP_10. It can be seen that an increase in thermal conductivity is associated with a decrease in the minimum temperature. The negligible effect of thermal conductivity on the maximum temperature is evident from Fig. 28b. On the contrary, as shown in Fig. 28c, the thermal conductivity negatively affects the total heat flux. The total heat flux increases with the density of EC in the case of ECC_CP_10. The specific heat has a positive effect on the heat flux.

Conclusions

This study comprehensively explored the post-fire self-healing capabilities of concrete incorporating encapsulated bacteria within CBCs. The experimental results demonstrated that the encapsulation of bacteria significantly enhances the residual compressive strength of fire-exposed concrete, with CFBB_CP_20 and ECC_CP_20 samples showing the highest resilience. The FE model, validated by experimental data, effectively replicated the thermal and mechanical behavior observed during testing, confirming that the encapsulated bacteria remained viable and facilitated post-fire healing by bio-precipitating calcium carbonate.

A significant outcome of this research is the role of carbon-rich coatings in providing additional thermal protection, thereby minimizing fire-induced micro-cracking and preserving the structural integrity of the concrete. This dual protection mechanism highlights the potential of integrating sustainable, self-healing materials into fire-resistant construction. Future work should aim to optimize these techniques for large-scale application and assess their long-term performance under real-world conditions.

The main finding of the study are as follows:

-

1.

The 20% ECC_CP, EC, CFBB, CFBB_CP, GC_CP, and RA have shown maximum average percentage weight reduction for water submerged samples, i.e., 47%. 46.47%, 47.48%, 47.21%, 46.97%, and 46.81%, respectively.

-

2.

The 20% ECC_CP, EC, CFBB, CFBB_CP, GC_CP, and RA have shown least average percent weights increment for saturated samples, i.e., 1.69%,1.52%, 1.39%, 1.12% 1.17%, and 1.78%, respectively.

-

3.

The density of CC is decreased with the substitutions i.e., the percentage decrease in density is maximum for 7.17% for CFBB_CP_15, respectively with respect to reference samples.

-

4.

The maximum and minimum Ve-Be time were for CFBB_10 (6.4 s) and CC (5.4 s).

-

5.

The average percentage reduction of compression strength during 7 and 28 days of curing for 10%, 15%, and 20% are ECC_CP (7.32%, 13.57%, and 18.33%), and (6.11%, 8.96%, and 13.36%), EC (9.72%, 16.80%, and 20.65%), and (8.19%, 11.28%, and 15.72%), CFBB (6.10%, 10.21%, and 14.65%), and (3.26%, 6.52%, and 11.12%), CFBB_CP (6.93%, 11.11%, and 15.14%), and (4.68%, 7.94%, and 12.14%), GC_CP (11.13%, 16.41%, and 21.61%), and (9.25%, 12.87%, and 17.43%), and RA (13.16%, 17.77%, and 22.78%), and (14.22%, 17.80%, and 21.16%), respectively in compare to CC.

-

6.

The compressive strength has increased maximum by 25.17% for EC_20 and minimum by 18.41% for RA_10 after 28 days compared to 7 days curing.

-

7.

The treated CFBB_15 have shown best compressive strength, whereas, untreated CC samples degraded most post-fire exposure.

-

8.

The maximum residual compressive strength improvement is noticed in CFBB_10 by 4.32%, 3.89%, 3.18%, and 1.62% for treated, 6.76%, 5.58%, 4.72%, and 2.97% for self-healed, and 8.79%, 6.69%, 5.08%, and 3.31% for treated and self-healed samples after 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C, respectively. However, the least recovery of compressive strength is observed for RA_10 3.77%, 2.74%, 2.13%, and 1.14% for treated, 6.06%, 5.02%, 3.78%, and 2.05% for self-healed, and 7.86%, 5.94%, 3.97%, and 2.05% for treated and self-healed samples after 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C, respectively.

-

9.

The fire test results proved that the average temperature of CC is typically higher than other counterparts for identical exposure time.

-

10.

The 20% bacteria substitution in all the combinations of samples has shown better properties than 10% and 15% bacteria substitution. The SEM images reflect the accumulation of CFBB and GC_CP in the CC. Likewise, irregular shapes particles of residuals can also be identified in a compact matrix.

-

11.

The dynamic modulus from ultrasonic testsare approximately 4–10% higher than the dynamic modulus from the static test for untreated, treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples. However, during fire exposure, the error percentage of dynamic modulus from ultrasonic and static tests have been increased by approximately 7–13%, 9–17%, 16–33%, and 28–53% for untreated, treated, self-healed, and treated and self-healed samples after 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C, respectively.

-

12.

FEM analyses provide insights into how fire exposure duration, boundary conditions, and material composition affect the temperature, heat flux, stress, and deformation in cementitious materials. These findings are valuable for understanding the behavior of such materials under fire conditions and can inform design and safety considerations. The duration of fire exposure significantly affects the degradation of properties in cementitious materials. Longer exposure times lead to more pronounced degradation. Deformation in the concrete sample varies based on the boundary conditions. The highest total deformation is observed when all four sides are subjected to fire exposure. The thermo-structural properties of different material constituents, such as coarse aggregate, gelatin encapsulations, and wood particles, play a role in the observed stress and deformation patterns.

-

13.

The investigation demonstrates that effective shielding against temperature increases in EC-loaded samples during fire exposure. This shielding effect is particularly evident in the slower rate of temperature rise and lower temperature differentials observed in samples with cement paste. The EC_CP_10 sample displays a higher temperature difference than the EC_CBC_10 sample, indicating the effectiveness of cement paste in reducing temperature differentials. The protective properties of cementitious materials in fire scenarios can provide valuable insights for improving construction and material design to enhance fire resistance.

Future studies will focus on evaluating the long-term durability of self-healing concrete, including its stability under aging and repeated thermal and mechanical stresses, to ensure its practical applicability in real-world conditions. The encapsulation techniques demonstrated in this study are compatible with conventional concrete production processes, suggesting potential for scalability. Materials such as expanded clay, carbon fiber balls, and gelatin capsules are readily adaptable to large-scale construction. However, factors such as production costs, logistics, and long-term durability must be optimized to ensure practical implementation. Future studies will focus on addressing these challenges and validating the performance of self-healing concrete technologies under field conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Cai, G., Zheng, X., Gao, W. & Guo, J. Self-extinction characteristics of fire extinguishing induced by nitrogen injection rescue in an enclosed urban utility tunnel. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 59, 104478 (2024).

Kodur, V. Properties of concrete at elevated temperatures. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, e468510 (2014).

Komonen, J. & Penttala, V. Effects of high temperature on the pore structure and strength of plain and polypropylene fiber reinforced cement pastes. Fire Technol. 39 (1), 23–34 (2003).

Khoury, G. A., Grainger, B. N. & Sullivan, P. J. E. Strain of concrete during first heating to 600°C under load. Mag Concr Res. 37 (133), 195–215 (1985).

Naus, D. The Effect of Elevated Temperatures on Concrete Materials and Structures—A (Literature Review at ORNL, 2006).

Liu, Y., Wang, W., Chen, Y. F. & Ji, H. Residual Stress-Strain relationship for thermal insulation concrete with recycled aggregate after high temperature exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 129, 37–47 (2016).

Shah, A. H. & Sharma, U. K. Fire resistance and spalling performance of confined concrete columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 161–174 (2017).

Haddad, R. H., Al-Saleh, R. J. & Al-Akhras, N. M. Effect of elevated temperature on bond between steel reinforcement and fiber reinforced concrete. Fire Saf. J. 43 (5), 334–343 (2008).

Abid, M., Hou, X., Zheng, W. & Hussain, R. High temperature and residual properties of reactive powder Concrete – A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 147, 339–351 (2017).

Concrete Microstructure, Properties, and Materials | McGraw-Hill Education—Access Engineering. https://www.accessengineeringlibrary.com/content/book/9780071797870. Accessed 12 Jul 2023.

Zhou, Q. & Glasser, F. P. Thermal stability and decomposition mechanisms of ettringite at < 120°C. Cem. Concr Res. 31 (9), 1333–1339 (2001).

Taylor, H. F. W. 33. hydrated calcium silicates. Part V. The water content of calcium silicate hydrate (I). J. Chem. Soc. Resumed. 1, 163–171 (1953).

Vedrtnam, A. et al. Experimental and numerical structural assessment of transparent and tinted glass during fire exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 250, 118918 (2020).

Vedrtnam, A. & Gunwant, D. Modeling improved fatigue behavior of sugarcane fiber reinforced epoxy composite using novel treatment method. Compos. Part. B Eng. 175, 107089 (2019).

Wang, X., Tan, Q., Wang, Z., Kong, X. & Cong, H. Preliminary study on fire protection of window glass by water mist curtain. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 125, 44–51 (2018).

El-Fitiany, S. F. & Youssef, M. A. Interaction diagrams for Fire-Exposed reinforced concrete sections. Eng. Struct. 70, 246–259 (2014).

Sarvaranta, L. & Mikkola, E. Fibre mortar composites under fire conditions: effects of ageing and moisture content of specimens. Mater. Struct. 27 (9), 532–538 (1994).

Vedrtnam, A., Bedon, C. & Barluenga, G. Study on the compressive behaviour of sustainable Cement-Based composites under One-Hour of direct flame exposure. Sustainability 12 (24), 10548 (2020).

Xiao, X., Unluer, C., Chu, S. & Yang, E. H. Single bacteria spore encapsulation through Layer-by-Layer Self-Assembly of Poly(Dimethyldiallyl ammonium Chloride) and silica nanoparticles for Self-Healing concrete. Cem. Concr Compos. 140, 105105 (2023).

Cappellesso, V. G., Van Mullem, T., Gruyaert, E., Van Tittelboom, K. & De Belie, N. Bacteria-Based Self-Healing concrete exposed to Frost salt scaling. Cem. Concr Compos. 139, 105016 (2023).

Meraz, M. M. et al. Self-Healing concrete: Fabrication, advancement, and effectiveness for long-term integrity of concrete infrastructures, Alex. Eng. J., 73, 665–694. (2023).

Shivanshi, S., Chakraborti, G., Upadhyaya, S. & Kannan, N. K. A study on bacterial self-healing concrete encapsulated in lightweight expanded clay aggregates. Mater. Today Proc. (2023).

Luhar, S., Luhar, I. & Shaikh, F. U. A. A review on the performance evaluation of autonomous Self-Healing bacterial concrete: mechanisms, strength, durability, and microstructural properties. J. Compos. Sci. 6 (1), 23 (2022).

Indhumathi, S., Dinesh, A. & Pichumani, M. Diverse perspectives on self healing ability of engineered cement Composite – All-Inclusive insight. Constr. Build. Mater. 323, 126473 (2022).

Mohamed, A. et al. Factors influencing Self-Healing mechanisms of cementitious materials: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 393, 131550 (2023).

Hungria, R. et al. Optimizing the Self-Healing efficiency of Hydrogel-Encapsulated bacteria in concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35 (4), 04023048 (2023).

Pan, X. & Gencturk, B. Self-Healing efficiency of concrete containing engineered aggregates. Cem. Concr Compos. 142, 105175 (2023).

Susanto, S. A., Hardjito, D. & Antoni, A. Review of autonomous Self-Healing cementitious material. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 907 (1), 012006 (2021).

Dharmabiksham, B. & Murali, K. Experimental investigation on the strength and durability aspect of bacterial self-healing concrete with GGBS and dolomite powder. Mater. Today Proc., 66, 1156–1161 (2022).

Nair, P. S., Gupta, R. & Agrawal, V. Self-healing concrete: A promising innovation for sustainability: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 65, 1410–1417. (2022).

Galal, M. K. et al. Self-healing bio-concrete: Overview, importance and limitations. In 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), 1–6. (2022).

Nodehi, M., Ozbakkaloglu, T. & Gholampour, A. A systematic review of Bacteria-Based Self-Healing concrete: biomineralization, mechanical, and durability properties. J. Build. Eng. 49, 104038 (2022).

Du, W., Qian, C. & Xie, Y. Demonstration application of microbial Self-Healing concrete in sidewall of underground engineering: A case study. J. Build. Eng. 63, 105512 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Properties and mechanism of Self-Healing cement paste containing microcapsule under different curing conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 357, 129410 (2022).

Bansal, S., Tamang, R. K., Bansal, P. & Bhurtel, P. Biological methods to achieve self-healing in concrete. In Advances in Structural Engineering and Rehabilitation, (S. Adhikari, B. Bhattacharjee, and J. Bhattacharjee, eds), 63–71 (Springer, 2020).

Li, X., Zhao, S. & Wang, S. Status-of-the-Art for Self-Healing concrete. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1622 (1), 012011 (2020).

Dinarvand, P., Rashno, A. & Sustain, J. Review of the potential application of bacteria in self-healing and the improving properties of concrete/mortar. Cem. -Based Mater., 11 (4), 250–271. (2022).

Zhang, Y., Wang, R. & Ding, Z. Influence of crystalline admixtures and their synergetic combinations with other constituents on autonomous healing in cracked Concrete—A review. Materials 15 (2), 440 (2022).

Su, Y., Qian, C., Rui, Y. & Feng, J. Exploring the coupled mechanism of fibers and bacteria on Self-Healing concrete from bacterial extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Cem. Concr Compos. 116, 103896 (2021).

El Enshasy, H. et al. Biocement: A novel approach in the restoration of construction materials. In Microbial Biotechnology Approaches To Monuments of Cultural Heritage, (eds Yadav, A. N., Rastegari, A. A., Gupta, V. K. & Yadav, N.), 177–198. (Springer, 2020).

Fahimizadeh, M., Abeyratne, A., Mae, L., Singh, R. & Pasbakhsh, P. Biological Self-Healing of cement paste and mortar by Non-Ureolytic bacteria encapsulated in alginate hydrogel capsules. Materials 13, 3711 (2020).

Sohail, M. G. et al. Bio Self-Healing concrete using MICP by an Indigenous Bacillus cereus strain isolated from Qatari soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 328, 126943 (2022).

Sonmez, M. & Erşan, Y. Ç. Production and compatibility assessment of denitrifying biogranules tailored for Self-Healing concrete applications. Cem. Concr Compos. 126, 104344 (2022).

Liu, Y., Zhuge, Y., Fan, W., Duan, W. & Wang, L. Recycling industrial wastes into Self-Healing concrete: A review. Environ. Res. 214, 113975 (2022).

Reshma, T. V., Kumar, C. & Khalid, S. P. Influence of self-healing behavior of bacteria & e-waste incorporated concrete on its mechanical properties. Mater. Today Proc. (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. State-of-the Art on preparation, performance, and ecological applications of planting concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e03131 (2024).

Long, X., Iyela, P. M., Su, Y., Atlaw, M. M. & Kang, S. Numerical predictions of progressive collapse in reinforced concrete beam-column sub-assemblages: A focus on 3D multiscale modeling. Eng. Struct. 315, 118485 (2024).

Wang, X., Zhang, J., Sun, W. & Zhao, Y. Effect of thermal properties of aggregates on the mechanical properties of concrete at high temperature. Materials 14 (20), 6004 (2021).

Funding

This project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No 945478 (SASPRO2) and also Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 754382 (GOT-ENERGY TALENT). The content of this article does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.V., D.G. and K.K. wrote the main manuscript text and A.V., H.V. conducted experiments, M.T. P, G.B. supervised the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vedrtnam, A., Palou, M.T., Varela, H. et al. Experimental and numerical study on post-fire self-healing concrete for enhanced durability. Sci Rep 15, 9731 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94331-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94331-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Validated thermal model for bacterial survival in fire-resistant self-healing concrete

Scientific Reports (2025)