Abstract

This swift growth in Internet of Vehicle (IoV) networks has created serious security issues, primarily in intrusion detection due to the fact that these are complex, dynamic, and large-scale networks. AES-256 encryption for strong real-time security and access control, along with Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE) for privacy-preserving collaborative data processing and encrypted computations, are some of the innovative contributions to IoV security that this work presents. Z-score normalization and median imputation are two excellent methods for prepping high-quality data for a deep learning-based intrusion detection system (IDS). Vision Transformer (ViT), wavelet transforms, and GAT ensure effective feature extraction, and a novel hybrid optimization known as Crayfish-Mother secure Optimization (CMSO) method is proposed to optimize feature selection to its maximum and reduce computational cost. DenseNet, GoogleNet, AlexNet, and SqueezeNet are also integrated in the newly proposed DAGSNet architecture to enhance feature detection and classification, enhancing the dependability and effectiveness of the IDS for IoV security. A highly secure, effective, and precise intrusion detection system in IoV environments is guaranteed by this holistic approach with the minimum time of encryption and decryption (0.02 s, 0.82 s) and maximum precision of two datasets (0.991, 0.984).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

IoV is considered an evolutionary process, utilizing cutting-edge communication technologies like Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V), and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I), to connect vehicles with organization, pedestrians, as well as networks1. For improved traffic flow, and road safety, and facilitating applications such as fleet management, entertainment, and autonomous driving, IoV combines smart transportation systems by processing real-time data2. IoV has made cars an integral component of smart cities due to the frictionless information exchange artificial intelligence and cloud computing technologies upon which they depend3. However, a prolonged attack surface that arises from increased connectivity does present a severe security concern in terms of the threat of malicious attacks and unauthorized access in addition to data breaches4. The current literature reviews many approaches to detecting intrusion in IoV systems such as traditional rule-based systems, blockchain for secure communication, and machine learning (ML)-based approaches5.

These techniques are applied to address certain threats like spoofing, tampering with data, and denial-of-service attack6. For instance, cryptographic techniques center on communication protection, whereas algorithms for anomaly detection are designed to detect abnormal traffic in IoV networks7. Most current solutions are still suffering from issues like high computational complexity, low scalability in real-time systems, and low flexibility to cope with evolving attack patterns despite recent developments8. Typical security solutions for multiple platforms and various manufacturers are also more difficult due to the heterogeneity of IoV systems9. Deficiencies in current intrusion detection systems of IoV call for more practical, flexible, and scalable options10. The resource-constrained and dynamic IoV scenario where cars need to meet stringent latency constraints is sometimes overlooked by traditional approaches11.

Moreover, advanced cyberattack detection and prevention are hindered by inefficient coordination among dispersed elements in IoV systems12. This is towards the development of innovative intrusion detection systems that leverage advances in artificial intelligence, edge computing, and federated learning (FL) to enhance the real-time security, reliability, and resilience of IoV networks13. Closing these gaps will be pivotal in ensuring the safe emergence of IoV technologies so that a culture of user trust is built. Computational load, poor feature selection, and inability to evolve according to emerging cyber-attacks are the three most significant issues that the research intends to tackle in order to manage the key issues in IDS for IoV. Handling high-dimensional data is a problem for conventional IDS solutions, leading to inefficient real-time threat detection. Furthermore, existing feature selection methods are not able to determine the most significant features, and hence the achieved classification performance is not satisfactory. The failure of traditional IDS models to learn new and sophisticated attack behaviors makes them obsolete against emerging threats in dynamic IoV environments, which is a major issue too. Mitigating these issues more specifically, the present work integrates DAGSNet for high-classification accuracy, presents an optimised feature extraction algorithm (CMSO) for the sake of saving processing overheads, and utilizes privacy-preserving methods (HE, SMPC, and AES-256) to further enable safer, real-time threat detection in large IoV networks. Moreover, the following “List of symbol” shows the symbols used in the proposed section. The foremost contribution of this framework is,

-

It employs SMPC & Homomorphic Encryption (HE) to guarantee privacy-preserving collaborative data processing and safe computations on encrypted data. For symmetric keys and hardware-in-the-loop applications in the IoV systems, AES-256 encryption provides excellent real-time security and access control.

-

DL-based IDS runs with clean, consistent, and high-quality data inputs since preprocessing techniques include the median imputation to handle missing data, and Z-score normalization to normalize the data.

-

This work proposes a novel feature selection algorithm, CMSO to avoid overhead costs, and applies ViT, wavelet transforms and GAT algorithms to ensure effective and significant extraction of the features.

-

The framework enhances feature recognition and classification by utilizing the newly developed DAGSNet which is a combination of DenseNet, GoogleNet, AlexNet, and SqueezeNet to create more robust and reliable intrusion detection systems tailored for IoV.

The structure of the article is as follows: "Introduction" provides an overview of the IoV and the associated cybersecurity problems. "Litereature review" presents a review of pertinent research. "Problem statement" explains the proposed approach, while "Proposed methodology" presents the results and discussions. Lastly, "Data collection" provides a summary of the research.

Literature review

Liu et al.14 proposed in 2021 a cooperative intrusion detection system which offloads the training model onto scattered edge devices, e.g., roadside units (RSUs) and associated cars. There is a distributed federated-based approach to achieving security and privacy with reduced central server resources utilization. The shared and stored models for training were done on blockchain to ensure that the aggregate model is secure. This model investigates common threats and illustrates how this method reduces computation expense and communication overhead and attains cooperative privacy preservation for cars.

El-Gayar et al.15 introduced Dynamic Forest-Structured Ensemble Network (DFSENet) for the IoV in 2024. External sources’ network traffic data and In-Vehicle Networks (IVNs) data were classified efficiently by this network. The architecture defends intelligent connected vehicles (ICVs) and IoV systems from numerous cyber threats by enhancing the ability to effectively and accurately detect a variety of cyberattacks. To eliminate class imbalance issues and obtain a balanced class distribution, the combination of the SMOTE and the random under sampling mechanism was employed. The CICIDS2017 dataset was utilized to demonstrate the power of this approach.

Li et al. 202116 presented Transfer learning and two model updating strategies based on whether the IoV cloud was capable of providing timely a small amount of labeled data for an innovative attack. The second one was the local update method, where the IoV cloud could not provide any marked data in a timely manner. The local update method pre-labeled the unlabeled data in new attacks to acquire a pseudo label, and thereafter utilized the pseudo-labeled data for multiple transfer learning iterations. Then, a car completed the update without accessing the IoV cloud to obtain any labeled data.

In 2023, Sousa et al.17 presented IDS for forecasting the flooding attacks among the scenarios with vehicles. The emergence of 5G technology has exposed different computer-based scenarios. Decentralized administration pattern and the heterogeneity attributes of the IoV like time of connection and fast-topology variability caused by frequent high mobility cause difficulties in presenting network security solution to the wide array of vehicle connectivity. Machine learning algorithms have the potential to recognize and classify malicious activity in a network as well as glean patterns to secure better coverage over security needs. This model utilized the NS-3 to model 5G-enabled vehicle scenarios. Four datasets with different nodes, attackers, and mobility patterns were designed for this research using Simulation of Urban MObility (SUMO) data. In 2023, Poongodi and Hamdi18 proposed generative adversarial networks, or GANs, for IoV devices as a multilevel discriminator for the distributed model of IDS. The model employed a distributed multilevel GAN model with a central controller to identify unusual activity. For monitoring its data and identifying internal and external attacks on other adjacent devices, each IoV device in this solution communicates peer-to-peer with neighbors. Additionally, the solution maintains the privacy of all IoV system data, such as sensitive information like vehicle data, by avoiding datasets needing to be transferred to other IoV devices.

In 2024, Korium et al.19 introduced a novel intrusion detection framework specifically made for cyberattacks on vehicles located in the Internet of Vehicles environment, including denial-of-service, distributed denial-of-service, distributed reflection denial-of-service, brute force, botnets, and sniffing. Here, a machine learning-based intrusion detection system is employed that can identify anomalous activity by looking at network traffic to identify anomalous data flows.

Ullah et al.20 propose a presented LSTM-GRU hybrid approach for IoV intrusion detection. The method greatly increases the accuracy of attack detection while minimizing training and response time. This model employed pre-processing methods like as normalization, feature filtering, shuffling, and cleaning. The shuffling technique, which was used in pre-processing, randomly shuffles the dataset for model testing and training, enhancing the model’s performance.

In 2023, Xing et al.21 introduced a parallel analysis of spatiotemporal features (PA-STF)-based IDS for IoV. Initially, the feature correlations of IoV traffic was used to create an ideal subset of characteristics. Next, Long short-term memory (LSTM) and temporal convolutional network (TCN) are used in parallel to extract spatiotemporal information from IoV traffic.

In 2022, Cheng et al.22 presented a temporal convolutional network with global attention to build the TCAN-IDS in-vehicle network intrusion detection model. In particular, the TCAN-IDS model symmetrically encodes messages recalling a historical moment using 19-bit characteristics that include the original message’s data field and arbitration bit. The spatial-temporal detail characteristics were then extracted by the feature extraction model.

In 2024, Saheed et al.23 suggested an Ensemble Transfer Learning (TL) model of eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) designed especially for identifying zero-day attacks in IoV. This model incorporates deep Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), which offered transparency and helps cybersecurity experts comprehend judgments. Furthermore, the model used hybrid bidirectional long-short-term memory with autoencoders (BiLAE) to improve computational efficiency by reducing the dimensionality of IoV network traffic.

Problem statement

Due to the dynamic and dispersed character of these networks, the growing interconnectivity in the IoV systems has greatly improved transportation efficiency and safety, but it has also brought about serious security concerns. By utilizing innovations like GAN, DL, FL, and spatiotemporal analysis, IDS have advanced significantly. Such issues include high processing requirements, connection costs, the requirement for real-time tagged data, and a lack of flexibility in response to changing zero-day attacks. Moreover, most methods rely on central models, which jeopardize efficiency, privacy, and scalability in diverse IoV contexts. Current strategies still carry severe limitations in warranting reliable, real-time detection across various IoV scenarios despite worthy efforts in addressing these challenges, including distributed GAN model, temporal convolutional networks, and XAI-based transfer learning. Hence, a complete and flexible solution that fills such gaps is desperately needed to offer scalable, effective, and reliable intrusion detection in IoV systems.

Proposed methodology

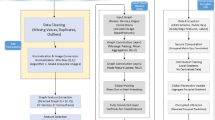

Here, in this research, an encryption deep learning-based Crayfish-Mother Swarm Optimizer (EDL-CMSO) model using DL and encryption is used in intrusion detection in IoV systems. In the proposed framework, DL, blockchain, and advanced cryptographical methods enhance intrusion detection in IoV systems. SMPC and HE ensure that computations are shared without full disclosures of data as well as homomorphic computations over encrypted data. AES-256 is put in place to protect symmetric keys and hardware-in-the-loop applications while adding a strong component in the form of access control and real-time data protection. Preprocessing techniques include the median imputation for data cleaning and Z-score normalization for the data standardization within the DL-based IDS. The novel DAGSNet framework combines the characteristics of DenseNet, GoogleNet, AlexNet, and SqueezeNet architectures to achieve comprehensive feature detection. In this, the new CMSO is used for reducing the overhead of feature selection, and for feature extraction, it uses ViT, wavelet transforms, and GAT. This strong integration guarantees IoV systems with enhanced intrusion detection capabilities that are effective, safe, and privacy-preserving. Figure 1 shows the workflow of the proposed architecture.

To enhance security and ensure precise detection of threats, the intrusion detection framework implemented in Controller Area Network (CAN) environments follows a systematic multi-phase approach. In an effort to capture both good and bad traffic, the system begins with gathering information, and this entails harvesting raw CAN traffic from vehicle networks. To ensure security and secure transportation, the data acquired is encrypted utilizing techniques such as Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), SMPC, and Homomorphic Encryption. Once encrypted, the information is processed via pre-processing to fine-tune data with mean imputation employed in addressing missing information and feature scaling through Z-score normalization. To gather high-level features and enhance data representation, the system subsequently applies advanced deep learning methods for feature extraction, including Vision Transformer, Graph Attention Network (GAT), and Wavelet Transform. After feature extraction, the most relevant features are selected through an optimization method named CMSO (likely a personalized optimization approach), which enhances detection accuracy and computing efficiency. Finally, DAGSNet, a sophisticated neural network designed to make accurate anomaly detection in CAN traffic, is employed to provide the sanitized data to a Deep Learning-based Intrusion identification System. The Detected Output, the enhanced possible intrusions in the network, is the outcome of the model labeling the input as malicious or normal. The architecture is particularly well-adapted to real-world applications because it integrates deep learning, encryption, and optimization techniques to offer robust cybersecurity in automotive applications.

Data collection

In this framework, two datasets are used for intrusion detection are CIC-IDS 2017 database and, the CAN database.

CIC-IDS 2017 dataset

This dataset, which is divided into two classes (Normal and Anomaly), provides a chance to experiment with different anomaly detection techniques. The system can be made more resilient to zero-day attacks by using it to find trends and deviations in Normal and Anomaly data without the need for labels. The main aim is to detect the anomaly using labelled data. Also, to detect the patterns in Normal and anomaly data without using labelled data by unsupervised methods and to make a model which detects abnormal behaviour in each system.

CAN dataset

A bus communication protocol called the Controller Area Network (CAN) establishes a standard for dependable and effective real-time transmission between in-vehicle nodes. This dataset covers DoS attacks, attack-free states, impersonation attacks, and fuzzy attacks. To create datasets, CAN traffic from a genuine car was logged using the OBD-II connection while message injection attacks were running. From the KIA SOUL, researchers extracted the in-vehicle data.

-

DoS Attack involves short-cycle injection of “0 × 000” CAN ID messages.

-

A fuzzy attack involves inserting messages with fake random CAN ID and DATA values.

-

The impersonating node with arbitration ID = ‘0 × 164’ injects messages as part of the impersonation assault.

-

Normal CAN messages are in an attack-free state.

To verify the applicability and generalizability of models, particularly for anomaly detection and vehicle cybersecurity, the CAN (Controller Area Network) dataset is a must. It consists of real or simulated CAN bus messages indicating how a vehicle’s electronic control units (ECUs) talk to each other. To validate a model’s resistance to cyberattacks, the datasets often include both normal and attack situations, for example, flooding, spoofing, and message injection. The diversity in car types, manufacturers, and driving conditions in the dataset enhances the model’s ability to generalize to different automotive settings. In addition, data sets can contain variations in payload structures, message rates, and error patterns, which are all used to ensure that models will be able to distinguish reliably between normal and anomalous behavior. To add robustness to validation, researchers often collect private data from real vehicle networks or utilize publicly available CAN data sets, like the Car Hacking Dataset, OTIDS, or TU Automotive Dataset. A well-crafted CAN dataset with a variety of situations is an assurance that models are reliable and versatile to be applied under real-world contexts.

CICIoV2024DecimalCSV

The decimal datasets consist of several files, each corresponding to different types of network behavior—both normal and malicious. Here’s a breakdown of the types of data you’ll find in the decimal format:

-

Benign Traffic Data: This dataset represents normal operations within the IoV environment. It includes traffic data that does not contain any malicious activities, serving as a baseline for what typical, non-threatening data traffic looks like.

-

DoS Attack Data: This file contains data simulating Denial of Service (DoS) attacks. These datasets are crucial for training and testing models to detect and respond to DoS scenarios, where the system is overwhelmed with traffic to disrupt service.

-

Spoofing Attack Data: There are multiple datasets for different spoofing attacks, each targeting specific vehicle controls.

-

GAS Spoofing: Data that simulates attacks aimed at manipulating gas control systems.

-

RPM Spoofing: Includes malicious data affecting the revolutions per minute (RPM) controls.

-

SPEED Spoofing: Consists of spoofed data that targets vehicle speed controls.

-

STEERING_WHEEL Spoofing: Contains data that mimics attacks on the steering control systems.

One of the most popular benchmarks to test intrusion detection systems (IDS) and cybersecurity models is the CIC-IDS 2017 dataset. It can be helpful in checking the generalizability and applicability of a model since it was created by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) and contains real network traffic data, both malicious and benign. The data set offers complete representation of cyber threats by covering an array of attack types such as brute force attacks, botnets, intrusion, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), and web threats. With exhaustive features like flow time, packet size, protocol types, and payload, it captures real-world network activity and helps models to learn sophisticated patterns for accurate identification. Additionally, the dataset is suitable for both supervised and semi-supervised learning methods since it contains both labeled and time-stamped data. The generalization ability of the model in different network conditions is enhanced by the diversity in attack types and normal traffic, making it suitable for real-world cybersecurity deployment. To further confirm the robustness and adaptability of a model, researchers often blend CIC-IDS 2017 with other datasets, including CSE-CIC-IDS 2018 or UNSW-NB15.

Dataset structure and features

Each file in the decimal dataset typically includes a wide range of features extracted from network traffic. These features might include, but are not limited to:

-

Timestamps: Indicating the time the data packets were captured.

-

Packet Sizes: The size of each packet in the network traffic.

-

Source and Destination IP Addresses: IP addresses from which data packets originate and where they are being sent.

-

Port Numbers: Port numbers involved in the network communication.

-

Payload Information: This might include specific data extracted from the packet payloads, presented in decimals.

-

Label: Each instance is labeled as benign or specifies the type of attack, making it suitable for supervised learning tasks.

Figure 2 displays the database’s SHAP analysis. The variables “Flow Duration,” “Total Fwd Packets,” and “Total Length of Fwd Packets” are ranked as the most significant in determining the network’s behavior about the “CIC-IDS 2017 dataset,” confirming the idea that flow characteristics are crucial for anomaly identification. However, with the characteristics of vehicle communication systems, it is expected that factors such as message frequency and payload size would be the top followed in the CAN Dataset.

Data encryption by IoVCipherGuard approach

The system of IoV collects and safeguards data from a range of sources, including sensors, road construction, and automobiles. It is significant because such data will contain sensitive information about the traffic patterns of the network, the behavior of vehicles, and even potential threats. This collected information is first encrypted by an approach called IoVCipherGuard to maintain secrecy. Among the methods is homomorphic encryption, which preserves confidentiality during the data processing stage by allowing encrypted data to be processed without the need to decrypt it. Furthermore, SMPC is utilized to conduct calculations on shared data without granting any participant access to the complete dataset, thus encouraging anonymity in team data sharing. Finally, even with high data quantities, an AES-256 is used because of its strength and effectiveness when encrypting symmetric keys and hardware-in-the-loop applications. In addition to implementing real-time processing, which is necessary for IoV systems, this integration efficiently performs limited access control and offers preventative data protection throughout the whole data gathering and processing process. To ensure privacy, the system utilize privacy-preserving techniques such as SMPC and HE. This allows vehicles and infrastructure to collaborate and process data without exposing sensitive information to any party, maintaining user privacy while still enabling effective intrusion detection. HE with DL models to allow SMPC during the intrusion detection process. This ensures privacy without compromising the performance of the intrusion detection system. While HE is novel, its application to collaborative, distributed IDS in IoV systems may be considered innovative, as it allows multiple vehicles to contribute data for intrusion detection while maintaining confidentiality.

Homomorphic encryption

Data that has been encrypted can be used for calculations without having to be decrypted due to HE24. This guarantees security and privacy for IoV systems. The mathematical assumptions based on HE is given below.

In Key Generation, a public and private key pair (\(\:pk,sk\)) is generated in Eq. (1).

Where, \(\:\lambda\:\) is the security parameter. Then, a plaintext \(\:m\) is encrypted using the public key \(\:pk\) in Eq. (2).

Where \(\:c\) is the ciphertext. After this, homomorphic operations are performed with two plaintexts \(\:{m}_{1},{m}_{2}\) is encrypted into \(\:{c}_{1}\)and \(\:{c}_{2}\) which are determined in Eq. (3).

Then, addition and multiplication operations are directly performed on encrypted data in Eq. (4) (5).

Where, \(\:\oplus\:\) and \(\:\otimes\:\) are the homomorphic addition and multiplication. Finally, the data is decrypted using the private key \(\:sk\) in Eq. (6)

As a result, sensitive data can be processed by IoV nodes using encrypted sensors or vehicle data.

Secure multi-party computation

SMPC allows multiple parties to collaboratively compute a function over their private inputs without revealing the inputs themselves, preserving data privacy25. Initialize the \(\:n\) parties, \(\:{P}_{1},{P}_{2},\cdots\:,{P}_{n}\) hold private inputs \(\:{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\cdots\:,{x}_{n}\). This computation aims to compute the public function \(\:f({x}_{1},{x}_{2},\cdots\:,{x}_{n})\) without revealing \(\:{x}_{i}\)26. In secret sharing, split each of the input \(\:{x}_{i}\) into \(\:n\) shares \(\:\{{x}_{i1},{x}_{i2},\cdots\:,{x}_{in}\}\) is determined in Eq. (7)

Where, \(\:p\) represents the prime modulus. Each party receives one share of every input. In secure computation, the parties used the protocol for computing the shares of the result. \(\:f\) in Eq. (8).

Finally, the shares are combined to reconstruct the result \(\:y\)27.

SMPC is typically employed in distributed systems that need numerous participants to compute in a privacy-preserving manner, but since only one person processes the data, its direct utility in a single-point automotive network intrusion detection system is less significant. Nevertheless, SMPC can be modified for cooperative IoV intrusion detection situations in which data is exchanged among several vehicles or nodes. In these situations, SMPC securely updates models or aggregates dispersed data while maintaining privacy. In contrast to single-node implementations, the original text’s explanation should explicitly link the use of SMPC with distributed settings or support its applicability by emphasizing the possible privacy benefits in larger collaborative detection frameworks. SMPC plays a vital part in the intrusion detection process by enabling multiple parties (such as IoV nodes, edge devices, and cloud servers) to collaboratively analyze and detect security threats without revealing their private data. In Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), SMPC ensures that raw traffic data, user behavior logs, and other sensitive information remain encrypted during the detection process, preventing unauthorized access and data leakage. By distributing computations across multiple parties, SMPC enhances privacy, security, and trust among interconnected IoV entities while still allowing for real-time anomaly detection. This is especially valuable in IoV environments where data originates from diverse and potentially untrusted sources. Additionally, SMPC strengthens resistance against adversarial attacks, ensuring that malicious entities cannot manipulate or gain insights into IDS operations.

Advanced encryption standards

AES is a symmetric block cipher that encrypts data in IoV systems to provide confidentiality during connection28. Assume that the input in this framework is the 128-bit plaintext block P, and the output is the 128-bit ciphertext block C, with the symmetric key K, which might be 128, 192, or 256 bits, depending on the AES variation. The number of rounds (R) that the AES uses to process the plaintext varies depending on the size of the key; for 128-bit keys, R = 10, for 192-bit keys, R = 12, and for 256-bit keys, R = 14. Here each round has four main operations: The substitution box is used to replace each byte of the plaintext which is determined in Eq. (10).

Where, \(\:S\) is the S-Box mapping. Next, row shifting is performed through cyclically shifting the rows of the \(\:4\times\:4\) plaintext matrix in Eq. (11).

In Linear Transformations, the matrix multiplication is used to transform each column of the matrix in the Galois Field \(\:GF\left({2}^{8}\right)\) which are determined in Eq. (12).

Where, \(\:M\) denotes the fixed \(\:4\times\:4\) matrix. In Key Mixing, the state is XORed with a round key. \(\:{K}_{r}\) is determined in Eq. (13).

Finally, decryption reverses the encryption process using inverse operations of the above-mentioned process involving inverse subBytes, inverse shift, inverse shift rows, inverse MixColumns, and AddRound key. These processes are performed until the original plaintext \(\:P\) is reconstructed. Encrypted model updates are sent to the central server, wherein the aggregation is achieved via the new Adaptive Federated Proximal Hierarchical Averaging (AFPHA), which includes the Federated Averaging (FedAvg ), Federated Proximal (FedProx), and Hierarchical Federated Learning (HFL). FL allows multiple devices (or clients) in a distributed system, such as the IoV, to collaboratively train machine learning models without sharing raw data. Instead, each device trains a model locally on its data and sends updates (model parameters) to a central server. These updates are aggregated to create a global model. FedAvg is a method of training ML models when data is dispersed over a large number of servers or devices. It enables model training without revealing raw data, hence guaranteeing the security and privacy of data, including data locality. This is a widely used federated learning technique where each device computes a local model update, and the server averages these updates to form a global model. FedProx is an optimization technique used while training DL models in a federated environment. FedProx is an enhanced version of FedAvg that incorporates a proximal term to reduce the impact of data heterogeneity. It adjusts the learning process to account for differences in local updates, improving convergence when devices have diverse data. It stands for the name distributed proximal point optimization, which is used for heterogeneous data federated learning. HFL is one kind of machine learning that has enabled several devices to train models in parallel with no data exchange. In HFL, devices are grouped into clusters, and each cluster trains a local model. The server aggregates models from each cluster, creating a global model. However, HFL is far more effective compared to a traditional cloud-client architecture in design and will make model training relatively faster. It calculates how quickly the global model converges. This is measured in terms of the number of communication rounds or the amount of time needed for convergence. The analysis helps to set optimal parameters, such as the number of rounds or the learning rate. By integrating these techniques, AFPHA provides secure, decentralized updates and adaptive, low-latency detection in IoV networks.

Preprocessing

The preprocessing processes include normalizing the data using Z-score normalization and cleaning the data using the median imputation.

Data augmentation

To address dataset imbalance in the Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for IoV, this study employs a combination of oversampling, undersampling, and data augmentation techniques to ensure a well-balanced and representative dataset. Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) is used to generate synthetic samples for underrepresented attack classes, preventing the model from being biased toward majority classes. Also, cost-sensitive learning is embedded through imposing higher penalty on minority misclassified samples, enhancing the detection rate of rare attacks. Data augmentation at feature level such as wavelet transformation, injection of noise, and time-series augmentation (window slicing and permutation) also adds to dataset diversity while maintaining vital traffic patterns. To avoid overfitting on normal traffic, random under sampling of majority classes is used. These methods combined enhance model generalization, improve detection of infrequent attacks, and provide a more equitable, high-performing IDS for practical IoV applications.

Data cleaning

In the median imputation29, the median of the associated feature is used to fill in the missing values in a dataset. Here, assume that the dataset be \(\:=\left\{{x}_{ij}\right\}\) where \(\:{x}_{ij}\) denotes the value of the jth feature for the i-th data point. Several values \(\:{x}_{ij}\:\)are missing. To replace the missing values, further processing is performed30. The median \(\:{M}_{j}\) is calculated for a feature from the non-missing values and is determined in Eq. (14)

Finally, the missing values are replaced in Eq. (15).

Data normalization

Z-score normalization is used to scale the data, assigning a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 to each characteristic. Equations (16), (17), (18) is used to determine the Z-score normalization for each value \(\:{x}_{ij}.\)

Here, \(\:n\) is the quantity of data points, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{j}\) is the standard deviation, \(\:{\mu\:}_{j}\) is the mean. This guarantees that the data is scaled (Z-score normalization) and cleaned (median imputation) for subsequent processing.

Feature extraction

This part integrates ViT, wavelet transforms, and GAT to extract significant features from IoV systems.

Vision transformer

In this framework, \(\:X\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{n\times\:m}\) decompose into wavelet coefficients using Discrete wavelet transform (DWT) is determined in Eq. (19).

Where \(\:{C}_{A},\) and \(\:{C}_{D}\)are used to capture the low-frequency and high-frequency features, \(\:n\) and \(\:m\) are the number of samples and features. The vision transformers operate on patches of the input data. In patch embedding, \(\:{X}_{wavelet}\)is divided into smaller patches of \(\:p\times\:p\) size, flattened, and linearly projected to feature space of dimension \(\:d\).

Where, \(\:k\) represents the number of patches, and \(\:P\) extracts the patches. Then, positional encoding is performed to add positional information \(\:{E}_{pos}\) to each patch embedding \(\:{z}_{i}.\)

Then, the attention scores are computed using the scaled dot-product attention in the self-attention mechanism for all patches is determined in Eq. (22).

Where, \(\:Q,K,V\) is said to be a query, key, and value matrix derived from \(\:{z}_{i}^{{\prime\:}}.\)

Where, \(\:{W}_{Q},\:K,\:and\:{W}_{V}\) are the learnable weight matrices. Then, the multiple attention heads are combined by using the Multi-Head Attention as determined in Eq. (24).

Where, \(\:h\) denotes the number of attention heads, and \(\:{W}_{O}\) represents the output projection matrix. Then, the transformer output process attention results via feed-forward layers are determined in Eq. (25).

The integration of ViTs for non-image data such as sensor data or traffic flow analysis is a potential area of novelty. Traditionally, ViTs are used for visual data, but adapting them for feature extraction in IoV systems could yield insights into complex, high-dimensional data from sensors, vehicle communications, and other sources.

Graph attention network

Typically, nodes in GAT represent the entities or properties being modeled. The nodes in the IoV intrusion detection system might be checked for distinct data pieces, like particular characteristics taken from the system (e.g., traffic patterns, sensor readings, etc.). The nodes in this instance are the patches \(\:{z}_{final}\:\), which stand for processed feature vectors from several stages (ViT, GAT, and wavelet). In this framework, GAT model relationships between patches or nodes. In graph representation, the patches \(\:{z}_{final}\:\)are represented as nodes in a graph \(\:C=(V,E)\), where \(\:V\:\)is the node, and the edges capturing relationships are said to be \(\:E.\) The adjacency matrix \(\:A\) is typically an \(\:N\times\:N\) matrix, where \(\:N\)is the number of nodes (patches) in the graph. The elements of the adjacency matrix represent the strength or weight of the relationship (edge) between the corresponding nodes. In GAT, the adjacency matrix is constructed dynamically by the attention mechanism based on the attention scores computed between each pair of nodes. These scores are determined by the attention coefficients (\(\:{\alpha\:}_{ij}\)) that measure the importance of node \(\:i\) for node \(\:j\), which is computed as described in Eq. (26).

Where \(\:\left|\right|\) represents concatenation, \(\:{W}_{h}\) is the learnable weight matrix, and the shared attention vector (\(\:\alpha\:\)). Then, the node features are updated by aggregating neighbors from neighbors. This attention score \(\:{\alpha\:}_{ij}\:\)determines the strength of the connection between nodes \(\:i\) and \(\:j\) and is used to update the adjacency matrix. The attention scores \(\:{\alpha\:}_{ij}\:\)are often normalized using a softmax function, as shown in the denominator of the equation. This normalization guarantees that the attention scores of all neighbouring nodes of node \(\:i\) add up to 1, which stabilizes the learning process and makes the network insensitive to different node degrees. After the attention coefficients are calculated and normalized, the adjacency matrix A is filled with these attention scores. The resulting adjacency matrix encodes the relationships between all pairs of nodes in the graph. For every node iii, the adjacency matrix will have the attention scores for all its neighbors \(\:j\) as \(\:{A}_{ij}\), showing the degree of their connections. The adjacency matrix is subsequently applied in the attention mechanism to transform the feature representations of every node. The transformed features of every node are calculated by summing up the features of the neighbors of the node, weighted using the attention scores. The process of updating is decided in Eqs. (27),

Where, \(\:\sigma\:\) is the non-linear activation functionIn GAT, the attention scores that indicate the relationships among nodes are used to build the adjacency matrix, and these attention scores are calculated dynamically with the help of the attention mechanism. This matrix helps the network concentrate on significant relations among nodes while neglecting minor ones, facilitating more efficient and context-sensitive feature extraction. The dynamic aspect of this construction is especially useful in IoV systems, where the interconnection among various nodes (e.g., vehicles, sensors) can be varied based on the network scenario and traffic flows. The output of the ViT and GAT are combined to generate the feature extraction for this framework. The final feature vector \(\:F\) is determined in Eq. (28).

This \(\:F\) is a final feature vector used for downstream tasks in intrusion detection in IoV systems. For reliable feature representation in IoV systems, this method efficiently extracts relational (GAT), spatial (ViT), and hierarchical (wavelet) features. In this case, the relationships or dependencies between these nodes would normally be represented by the edges. The correlation between traffic flow data from various vehicles or communication channels is one example of how the framework aim to represent the relationships between various aspects or entities in the IoV system. Depending on how similar or functionally dependent the traits are, these associations could be dynamically recorded. As demonstrated by the computation of the attention coefficients using LeakyReLU and learnable parameters, the attention mechanism aids in allocating weights (coefficients) to the edges, enabling the model to concentrate more on the most pertinent connections between nodes. The GATs are applied for the relationships between vehicle communication and infrastructure within the IoV network. Instead of treating the communication as independent, the attention mechanism allows for dynamic prioritization based on the context and importance of each interaction. This model enhances the ability of the system to detect attacks, such as data injection or eavesdropping, by recognizing abnormal relationships and interactions.

Feature selection

In this study, a novel CMSO is presented to address the overhead problems in the feature selection stage for improved intrusion detection in the IoV utilizing blockchain. In this case, the features are selected with Hybrid optimization namely Mother Optimization Algorithm (MOA) and Crayfish Optimization Algorithm (COA), which guarantees the best feature selection for the detection model. The COA and MOA are used to choose the best features from the established model, which made use of their swarming and hunting traits. The three distinct sources of COA behavior are the crayfish’s competitive activity, summer vacation, and foraging. The COA exploitation stage was the foraging and competition stage, whereas the exploration stage was the bringing up stage.

CMSO and DAGSNet architectures

CMSO – feature selection optimization

It is a novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm encouraged by the swarming behavior of crayfish and the mother’s guidance mechanism. It efficiently selects the most relevant features for intrusion detection in IoV by balancing exploration (diversity in feature selection) and exploitation (converging toward optimal features).

Design and optimization process

CMSO mimics crayfish movement where individuals explore different feature subsets, while the mother’s influence refines the selection process.

It applies a fitness function based on classification performance (e.g., accuracy, F-score) to evaluate candidate feature sets.

A mutation mechanism introduces small perturbations in feature selection to prevent local optima.

The algorithm iterates until convergence, selecting an optimal feature subset that maximizes detection accuracy while minimizing redundancy.

Improvements in feature selection

Reduces computational overhead by selecting only the most significant features.

Enhances IDS efficiency and speed without compromising accuracy.

Helps avoid overfitting, ensuring the model generalizes well to unseen attacks.

DAGSNet – advanced classification model for Iov intrusion detection

DAGSNet is a hybrid deep learning model integrating DenseNet, AlexNet, GoogleNet, and SqueezeNet, designed to enhance feature extraction, classification accuracy, and detection robustness.

Architecture and design

DenseNet component: Improves gradient flow and feature reuse, leading to better learning efficiency.

AlexNet layers: Provide robust feature extraction for low-level patterns in network traffic.

GoogleNet’s inception modules: Extract multi-scale features to capture diverse attack patterns.

SqueezeNet’s lightweight architecture: Reduces model size and computational costs while maintaining high classification performance.

Final fully connected layers: Perform high-precision classification using optimized feature representations.

Optimization and performance enhancements

Uses batch normalization and dropout to prevent overfitting.

Implements adaptive learning rates with Adam optimization to speed up convergence.

Employs attention mechanisms to focus on critical traffic features, enhancing detection accuracy.

Impact on classification accuracy

Higher detection rates for both known and novel cyber threats in IoV.

Reduced false positives due to better feature learning and refinement.

Lower computational complexity compared to conventional deep learning models, making it more suitable for real-time IoV applications.

By combining CMSO for optimized feature selection and DAGSNet for high-precision classification, the proposed system significantly improves intrusion detection performance in IoV environments. CMSO reduces computational overhead while ensuring only the most relevant features are used, whereas DAGSNet enhances feature extraction, classification robustness, and accuracy, making the IDS more efficient and reliable in detecting cyber threats.

Initialize population

A matrix of \(\:1\times\:dim\:\)is used to represent each crayfish in the multi-dimensional optimization problem. Each column vector represents the single solution to the objective function under optimization. Each variable \(\:{X}_{i}\:\)in a group of variables \(\:({X}_{i,1},{X}_{i,2},\cdots\:,{X}_{i,dim})\)has upper and lower bounds. A solution space is populated with arbitrary candidate solutions \(\:X\:\)upon initialization of the COA. The candidate solution depends on dimension dim and population size N. Equation (29) provided the initialization of the COA algorithm.

Where \(\:{X}_{i,j}\:\)is positioned as the individual’s position \(\:i\:\)in the \(\:j\:\)th dimension, \(\:X\) is defined as the population’s initial position, \(\:N\:\)is defined as the total number of populations, and \(\:dim\) is defined in the population dimension, Eq. (30) produces the \(\:{X}_{i,j}\:\)values.

Where, \(\:{lb}_{j}\) is a parameter corresponding to the lower limit of the \(\:j\:th\) parameter dimension, \(\:{ub}_{j}\) is a parameter that fits the upper limit of the \(\:j\:th\) parameter dimension, and \(\:rand\) is a generic placeholder for a random number. Temperature is defined as in Eq. (31). Crayfish consumption can be described with a mathematical model given in Eq. (32).

where, \(\:temp\) indicates the temperature of the environment in which the crayfish are located.

where, \(\:\mu\:\) denoted as the temperature of the crayfish, \(\:\sigma\:\) and \(\:{C}_{1}\)are defining the regulate intake of crayfish in different temperatures.

Summer resort stage(exploration)

When \(\:temp\) >30, the temperature is too high. At that time, the crayfish is selected to join the cave for summer vacation. The cave \(\:{X}_{shade}\)is expressed in Eq. (33).

A stochastic process is used to describe the competition between crayfish during their look for caves. When \(\:rand\) is less than 0.5, it indicates that there aren’t any other crawfish nearby to compete for the caves, therefore a crawfish can go straight to a cave for summer vacation. According to Eq. (34) at that point, the crayfish can use the cave as a summer vacation.

Where, \(\:\text{t}\) denoted as the current iteration number, \(\:t+1\)indicates as the next-generation iteration number, \(\:{C}_{2}\) indicates as the decreasing curve, are given in Eq. (35).

Where, \(\:T\) refers to the maximum number of iterations. In the Resource Summer stage, the crayfish’s goal is to reach the cave, which serves as the main focus of the resolution of said strategy. The crayfish can enter the cave at that pole. This encourages people to find the best answer and improves COA’s performance efficiency. Let the algorithm converge more quickly31. The hybrid optimization approach in this case is concentrated on the exploitation phase of MOA and the exploration phase of COA.

Uplift (exploitation phase)

The mothers’ instructions cover a variety of methods for getting children ready for learning. The MOA stage increases the ability to search and exploit the local area during the upbringing stage by making minor adjustments to the positions that the population members occupy. The dynamics of children’s personality development, as modeled by Eq. (36), are used to assign each member of the population a new place to simulate an upbringing stage. The prior position of the member who underwent position change is shown in Eq. (37) if the objective function value produced by a new position is less than the previous one.

where\(\:\:t\) is the current value of the iteration counter32,\(\:{F}_{i}^{P3}\) is the value of the objective function, \(\:{F}_{i}^{P3}\) is a uniformly distributed random number within [0, 1], and \(\:{X}_{i}^{P3}\) represents a new position of the ith population member that is established based on the third phase of the proposed MOA and \(\:{X}_{i}^{P3}\) are their dimensions in vector j.

DL based IDS via DAGSNet

This framework leverages the strengths of DenseNet, GoogleNet, AlexNet, and SqueezeNet to enhance intrusion detection and classification. By integrating the unique features of these architectures, DAGSNet combines their individual advantages to create a robust DL-based IDS tailored for effective feature extraction and accurate classification. The combination of these models is considered a hybrid approach. The idea of using multiple architectures together allows the system to capitalize on the individual advantages of each model, such as DenseNet’s dense connections, GoogleNet’s inception modules, AlexNet’s hierarchical feature extraction, and SqueezeNet’s parameter efficiency. This fusion helps to improve the model’s overall robustness, detection accuracy, and efficiency in detecting a wide range of intrusion types in the dynamic environment of IoV.

DenseNet

The input to DenseNet is a feature map that is passed through a series of convolutional layers. The input could be an image or structured data converted into a feature map. Each layer in DenseNet receives feature maps from all preceding layers through dense connections. The feature maps at the layer \(\:l\) is determined in Eq. (38).

Where the composite function is said to be \(\:{H}_{l},\:[{F}_{0},{F}_{1},\cdots\:,{F}_{l-1}]\) are the concatenation of feature maps from all previous layers. After \(\:L\:\)Layers, the DenseNet produces the dense output for the feature map is determined in Eq. (39).

After passing through multiple layers, the output \(\:{F}_{DenseNet}\:\)is the final feature map, which contains the aggregated feature information from all the preceding layers due to the dense connections. This output serves as a condensed representation of the data, used for intrusion detection.

GoogleNet

The input to GoogleNet is also a feature map, similar to DenseNet, which is processed using multiple inception modules. GoogleNet employs inception modules for detecting the intrusion features at multiple scales. To get the output of the inception module, each inception module applies parallel operations in Eq. (40).

Where, \(\:{F}_{pool}\) is said to be a feature map derived from max pooling, \(\:{F}_{1\times 1},{F}_{3\times 3},{F}_{5\times 5}\) are the feature maps from \(\:1\times\:1,\:3\times\:3,\:5\times\:5\)Convolutions. Finally, the final feature map is obtained Eq. (41) after the stacking multiple inception modules are performed.

The output, \(\:{F}_{GoogleNet}\), is the final concatenated feature map from all the inception modules. This output represents high-level features extracted from different convolutional operations, which help in detecting various intrusion patterns at different scales.

AlexNet

AlexNet is a conventional CNN that uses pooling layers after convolutional layers to detect hierarchical features. The feature map is the input to AlexNet, and it is fed through a sequence of convolutional layers with ReLU activation functions. This enables the network to learn hierarchical data patterns. Each convolutional layer is determined in Eq. (42).

Where \(\:Conv\) represents the convolution operation with learnable weights \(\:{W}_{l}\), Bias term is said to be \(\:{b}_{l}\). Then max pooling reduces the spatial dimensions after some layer is described in Eq. (43).

The final feature map output of AlexNet is determined in Eq. (44).

The output, \(\:{F}_{AlexNet}\) is the last pooled feature map obtained by applying max pooling to compress the spatial dimensions. The output encodes the hierarchical features that are learned from the input data and are required for detecting sophisticated intrusion patterns.

SqueezeNet

The feature map is input to SqueezeNet through a series of fire modules. The modules employ a “squeeze” layer (1 × 1 convolution) and an “expand” layer (3 × 3 convolution) to effectively extract features with minimal parameters. Fire modules are employed by SqueezeNet to detect features in a parameter-effective manner. Squeeze layer followed by the expand layer in Eq. (45)

Where, \(\:{F}_{squeeze}={Conv}_{1\times 1}\left({F}_{input}\right)\). The final output of the feature map after stacking multiple fire modules are described in Eq. (46)

The output, \(\:{F}_{SqueezeNet}\), is the concatenated feature map obtained after processing through multiple fire modules. This output captures compressed yet informative features, important for detecting intrusions with minimal computational cost.

The final input to DAGSNet is the concatenated feature vector formed by combining the outputs from all four networks: DenseNet, GoogleNet, AlexNet, and SqueezeNet. This combined feature vector, \(\:{F}_{combined}\) contains all the relevant features extracted from different perspectives by each individual network. Then, these feature maps are combined from all four networks in Eq. (47).

Furthermore, to detect the intrusion, pass \(\:{F}_{combined}\) via fully connected layer in Eq. (48)

Where \(\:W,b,\sigma\:\) are the learnable weights, bias term, and activation function. The network outputs the prediction score in Eqs. (49) (50).

The output \(\:y\), is the prediction score from the fully connected layer. This score can either be binary (0 or 1) for binary intrusion detection or a multi-class value (depending on the number of intrusion types) for multi-class classification. Model Pruning and Quantization reduce the number of parameters in DenseNet, GoogleNet, AlexNet, and SqueezeNet by using techniques like model pruning and quantization. These techniques eliminate less important parameters and reduce the size of the model, making it faster for both training and inference. The model Pruning removes weights that have a minimal impact on the final prediction, resulting in a smaller, more efficient model. Also, Quantization converts model weights from floating-point to lower-bit integer values, reducing memory usage and speeding up computations. Figure 3 shows the DAGSNet architecture of intrusion detection in IoV system. For reliable intrusion detection in IoV systems, this hybrid network makes use of the distinctive features of all four architectures.

Result and discussion

The developed approach is implemented using the Python tool, and the experiment results are verified using two different datasets, such as the CAN Dataset (http://ocslab.hksecurity.net/Dataset/CAN-intrusion-dataset) and CIC-IDS 2017 dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chethuhn/network-intrusiondataset), CICIoV2024DecimalCSV(https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/pushpakattarde/ciciov2024decimalcsv) for Intrusion Detection. To evaluate the effectiveness of the developed methods, performance metrics such as sensitivity, FNR, specificity, NPV, accuracy, FPR, and precision, MCC, Recall, and F-measure have been used. The experimental environment settings and network training parameters are given in Table 1.

Performance metrics

The chosen performance measures ensure correctness, reliability, and effectiveness, especially in imbalanced datasets, and provide a complete evaluation of the Intrusion Detection System (IDS). While accuracy is a wide measure of correctness, it alone is insufficient because it could be biased towards majority classes. Recall (sensitivity) ensures that true attacks are not missed, which is essential for security systems, and accuracy minimizes false alarms by determining the percentage of detected intrusions that are indeed threats. By evaluating the ability of the system to correctly identify normal traffic and eliminating unnecessary alarms, specificity improves recall. When both false positives and false negatives influence system performance, the F-measure (F1-score) is optimal as it is a compromise between precision and recall. To further enhance system reliability, NPV assesses the percentage of estimated benign cases that are indeed benign. The compromise between attack detection and false alarm avoidance is also examined by FPR and FNR, which is also very important in IoV security applications. Finally, since it considers all possible classification outcomes, the MCC provides a balanced evaluation and is particularly useful when analyzing IDS performance under circumstances with imbalanced datasets. Combined, these provisions ensure a realistic and complete analysis of the IDS in real-world IoV environments.

i) Accuracy: The percentage of accurately identified instances (both positive and negative) relative to all instances is known as accuracy. It assesses overall performance.

ii) Precision: The percentage of accurately identified intrusions (true positives) among all detected intrusions is known as precision. It assesses how well the optimistic predictions come true.

iii) Sensitivity: The proportion of real attacks that are accurately identified is known as sensitivity. It assesses the system’s ability to detect intrusions.

iv) Specificity: The percentage of real normal traffic that is accurately classified as normal is known as specificity. It assesses the system’s ability to prevent false alarms.

v) F-measure: The F-measure integrates Precision and Sensitivity into a single statistic by taking the harmonic mean of both. The ratio of false positives to false negatives is balanced.

vi) MCC: This measure evaluates the correctness of binary classifications by taking into account the four confusion matrix components (TP, TN, FP, and FN). Even with unbalanced data, it is a balanced measure.

vii) NPV: It calculates the percentage of correctly classified normal traffic (true negatives) among all cases that were predicted to be normal.

viii) FPR: It calculates the percentage of instances of regular traffic that are mistakenly labeled as intrusions. It assesses how likely the system is to sound false alerts.

ix) FNR: The fraction of real intrusions that the system overlooks (considered normal traffic) is measured and it is defined as FNR. It assesses the system’s tendency to overlook intrusions.

x) Recall: The capacity of a model to accurately identify every real positive case is measured using recall. It is the percentage of real positive cases (total intrusions) that are true positive predictions (properly identified intrusions).

Comparative analysis

The developed model gained outcomes are evaluated with the existing techniques like AlexNet, DenseNet, SqueezeNet and GoogleNet. These methods are compared for several performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, sensitivity, specificity, f-measure, NPV, MCC, FPR, and FNR.

The cryptographic techniques are shown in this Table 2; Fig. 4, shows encryption and decryption times (in seconds): AES, Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA), and the suggested technique. The effectiveness of the suggested approach can be substantiated through a comparison of different cryptographic algorithms’ encryption and decryption times. AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) is less effective for real-time scenarios since it boasts a relatively shorter encryption time of 0.059145 s but an incredibly long decryption time of 3.168541 s. ECC, or elliptic curve cryptography, gives the quickest encryption time (0.050126 s), but slower decryption time (4.955412 s) suggests that it has computational overhead in decryption procedures. Though known to be as secure as all others, RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) is the poorest performer, giving 0.079216 s for encrypting data and 7.854215 s for decrypting data. It is not suitable for secure real-time communication. The suggested encryption approach, however, performs much better than these classic approaches, which achieved the best decryption time of 0.821652 s and the shortest encryption time of 0.029152 s. This demonstrates that the proposed approach is ideal for real-time application like intrusion detection in Controller Area Network (CAN) because not only is it more secure, but computational delay as well. Fast data retrieval is enabled by the dramatic decrease in decryption time, an element key to sustaining system performance and responsiveness in security-conscious automotive networks.

Because inverse operations are computationally complex, AES offers comparatively quick encryption but slower decryption. While RSA is the least effective and has the longest encryption and decryption times because of its enormous key sizes and modular exponentiation, ECC delivers faster encryption but slower decryption due to extensive scalar multiplication. In comparison to conventional methods, the suggested method’s speed is probably driven by streamlined encryption and decryption procedures, perhaps making use of precomputation, lightweight cryptographic primitives, or hardware acceleration.

The performance metrics of the proposed model with and without feature selection are shown in Table 3. The comparison of different measures of evaluation shows clearly the influence of feature selection on the performance of the intrusion detection model. The feature selection model distinguishes better since its accuracy (0.99125) is greater than 0.980981 without feature selection. Feature selection also improves precision and recall, which are 0.985433 and 0.98452, respectively, versus 0.973654 and 0.97218 without feature selection. This indicates how the chosen features improve the ability to distinguish malicious from legitimate messages. Through feature selection, the model’s sensitivity (0.985453) and specificity (0.990158) further attest to its ability to identify true positives and true negatives correctly. The enhanced classification performance of the model is also reflected by the observation that the F-measure, which assigns equal importance to precision and recall, is slightly better when feature selection is applied (0.98455) compared to when it is not (0.979421). Also, there are fewer false negatives when the NPV increases to 0.990835. The enhanced detection feature of the feature-selected model is further illustrated through a significant reduction in FNR from 0.092452 to 0.00368 and FPR from 0.020045 to 0.001148. Finally, the quality of the model overall is gauged using the MCC that increases from 0.972166 to 0.984523 and indicates better predictability. These results show how feature selection significantly enhances the overall accuracy, reliability, and resilience of the intrusion detection system in addition to maximizing computing effectiveness.

The results of SHAP analysis (depicted in Fig. 5) for the intrusion detection systems for CAN and CIC-IDS 2017 datasets highlight the importance of many characteristics that are crucial for creating the intrusion detection models. The most significant predictor for the models built in the CIC-IDS 2017 dataset is the Flow Duration feature, which has the greatest potential with an average SHAP value of 0.12. This suggests that longer flow lengths are likely to signal the existence of more complex or protracted attacks, which makes it an extremely important attribute for distinguishing attack streams from regular traffic. But in the CAN dataset, the feature ID has the highest average SHAP value of 0.15, which is a definite sign of the model’s estimation. Flow-based metrics play a greater role in the CIC-IDS 2017 dataset than in the CAN set of messages, where much focus is laid on message identifiers and their data lengths. Recognition of what these features do would lead to a better feature selection strategy and the models’ contribution to successful intrusion detection results.

The performance of many intrusion detection methods (Proposed, AlexNet, DenseNet, SqueezeNet, and GoosgleNet) on the CAN datasets and CIC-IDS 2017 is compared in Table 4; Fig. 6 based on important metrics.

Table 4 shows a comprehensive performance assessment among the proposed model along with the existing models such as AlexNet, DenseNet, SqueezeNet, and GoogleNet on significant evaluation parameters using the CIC-IDS 2017 dataset. The CIC-IDS 2017 dataset is utilized to compare different deep learning models, highlighting the improved intrusion detection performance of the proposed method. As compared to AlexNet (0.966), DenseNet (0.979), SqueezeNet (0.957), and GoogleNet (0.955), the presented model has the highest accuracy of 0.991, indicating its efficacy in separating benign and malicious traffic. It also has the highest specificity of 0.990 and sensitivity of 0.985, providing equal influence in the accurate identification of true negatives and true positives. Also demonstrating its robustness in having high detection ability while avoiding erroneous classifications are the precision (0.985), recall (0.985), and F-measure (0.985). The model is able to detect normal events with fewer false negatives, according to the NPV of 0.991. The soundness of the model as applied to real scenarios in cybersecurity is demonstrated by the striking observation that the FNR rate is appreciably lower to 0.037 and the FPR rate is reduced to 0.011. Generally, the model performs well with a balance of predictions indicated by the MCC of 0.985. The lowest training time (320 s), testing time (85 s), and inference time (15 ms) are achieved with the proposed model, which performs much better computationally than alternatives. The proposed model offers an intrusion detection system that is efficient and faster in comparison to DenseNet (560s training, 110s testing, and 25ms inference), SqueezeNet (340s training, 92s testing, and 18ms inference), and GoogleNet (450s training, 98s testing, and 22ms inference). According to these findings, the suggested method is ideal for real-time network intrusion detection cybersecurity processes as it maintains effectiveness in computing while detection power is improved.

The suggested model’s superior detection capabilities are demonstrated in Table 5, which contrasts its performance on the CAN dataset with that of AlexNet, DenseNet, SqueezeNet, and GoogleNet. The effectiveness of the proposed method to intrusion detection is supported by experimentation on some of the proposed models using the CAN dataset. In comparison with AlexNet (0.956), DenseNet (0.970), SqueezeNet (0.948), and GoogleNet (0.946), the proposed model gives the best accuracy (0.984) in identifying malicious traffic from normal CAN traffic. In sensitivity (0.973) and specificity (0.981), the model performs better than others, providing a balanced capability to detect intrusions with fewer false alarms. Its strength in minimizing misclassification is also evident from the high precision (0.973), recall (0.973), and F-measure (0.972) it has. While the False Positive Rate (FPR) of 0.018 is significantly lower than all other models in reducing spurious alarms, the Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of 0.982 reflects good reliability in identifying normal CAN traffic. Additionally, missed incursions are minimized with a significant drop of the False Negative Rate (FNR) to 0.092. The model’s capability to consistently generate correct and well-balanced predictions is also proven through the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.972. The suggested model is computationally most effective, having the minimum inference time (12 ms), test time (75 s), and training time (310 s). Both speed and performance are significantly improved by the suggested model in comparison to DenseNet (540s training, 100s testing, 22ms inference), SqueezeNet (330s training, 85s testing, 15ms inference), and GoogleNet (420s training, 95s testing, 20ms inference). These findings verify that the new architecture is the best way to protect car networks since not only does it improve detection accuracy and trustworthiness, but it also guarantees fast and effective real-time intrusion detection in Controller Area Network (CAN) cases.

The performance study of the suggested model using the CICIoV2024 dataset in comparison to AlexNet, DenseNet, SqueezeNet, and GoogleNet is shown in Table 6. The suggested model is better at Internet of Vehicles (IoV) network intrusion detection, as the evaluation of deep learning models over CICIoV2024 dataset suggests. Compared with AlexNet (0.967), DenseNet (0.973), SqueezeNet (0.948), and GoogleNet (0.965), the suggested method offers the best accuracy (0.976), indicating that it is resistant to cyberthreat detection. Further, the model’s sensitivity (0.986) and specificity (0.962) are high, making the detection high while the rate of false positives remains low. Further, its capacity to classify properly is indicated by its precision (0.980), recall (0.968), and F-measure (0.974), decreasing the likelihood of misclassifying malicious or normal traffic. The model’s accuracy in detecting benign cases correctly is guaranteed by its NPV of 0.988, and its lowest FPR of 0.015 greatly minimizes false alarms from other models. Furthermore, fewer threats are lost because the FNR is minimized to 0.038. The even performance of the model in detecting malicious and normal traffic correctly is also guaranteed by its MCC of 0.973. The suggested model is computationally more efficient than the others with reduced training (500 s), testing (100 s), and inference (14 ms) time. The suggested method provides ample computational overhead saving, and therefore it is the best for real-time IoV security applications when compared to DenseNet (720s training, 140s testing, 25ms inference), SqueezeNet (550s training, 110s testing, 18ms inference), and GoogleNet (650s training, 130s testing, 22ms inference). These facts highlight how the model proposed is a contender for use in contemporary vehicle networks since not only does it improve detection quality but also provides efficient and reliable intrusion detection in IoV contexts.

The CIC-IDS 2017 dataset is used in Table 7 to compare the performance of the suggested model with state-of-the-art (SOTA) techniques, DFSENet, GAN, TCAN-IDS, and XAIEM. The comparison of some intrusion detection models in the CIC-IDS 2017 dataset shows that the proposed model outperforms other methods including DFSENet, GAN, TCAN-IDS, and XAIEM. In comparison with DFSENet (0.980), GAN (0.975), TCAN-IDS (0.965), and XAIEM (0.955), the proposed model achieves the maximum accuracy (0.991) and demonstrates the effectiveness of differentiating between benign and malicious network traffic. It also tops in terms of sensitivity (0.985) and specificity (0.990), providing an extremely high number of true positives with minimal false alarms. Also supporting its well-balanced performance and hardness in network intrusion classification are precision (0.985), recall (0.985), and F-measure (0.985). The model excellently classifies benign network traffic, minimizing false negatives, from the NPV of 0.991. At 0.011, it also offers the lowest FPR, which means less harmless traffic is flagged as malicious. In a similar manner, relatively fewer attacks are missed since the FNR is lowest at 0.037. Good balance in classification and predictability of the model are also evidenced by its MCC of 0.985. By having the shortest training (500s), testing (100s), and inference (14ms) times, the proposed model beats the alternatives in computational efficiency. To address real-time intrusion detection, the new method offers a more effective and scalable approach compared to DFSENet (650s training, 120s testing, 18ms inference), GAN (700s training, 140s testing, 22ms inference), TCAN-IDS (600s training, 110s testing, 20ms inference), and XAIEM (650s training, 130s testing, 19ms inference). These findings demonstrate that besides improving detection performance, the new paradigm offers an effective and computationally affordable method of protecting contemporary network infrastructures from cyber attacks.

Table 8 shows how well the suggested model performs using the CAN dataset in comparison to SOTA techniques DFSENet, GAN, TCAN-IDS, and XAIEM. The CAN dataset is utilized to evaluate various intrusion detection models, and the results indicate that the suggested model is superior to DFSENet, GAN, TCAN-IDS, and XAIEM. In terms of the security of Controller Area Networks (CAN) from cyberattacks, the suggested model is superior to DFSENet (0.974), GAN (0.967), TCAN-IDS (0.958), and XAIEM (0.950) with the greatest accuracy (0.984). Further, it has perfect sensitivity (0.973) and specificity (0.981) to achieve excellent intrusion detection without many false alarms. Precision (0.973), recall (0.973), and F-measure (0.972) are all in affirmation of the capability of the model in accurately detecting both malicious as well as valid traffic. Strong non-malicious communication reliability is indicated in NPV being 0.982. Although the FNR of 0.092 is still acceptable, the FPR of 0.018 is significantly lower than in other models, minimizing false alarms. The strong and stable classification ability of the model is also verified by its MCC of 0.972. The suggested model achieves the minimum testing (110 s), inference (15 ms), and training (550 s) time for calculation efficiency. For automotive network intrusion detection in real-time, the suggested model is appropriate as it is significantly faster than DFSENet (600s training, 120s testing, 18ms inference), GAN (650s training, 130s testing, 20ms inference), TCAN-IDS (620s training, 115s testing, 17ms inference), and XAIEM (640s training, 125s testing, 19ms inference). These findings confirm that the suggested method is the best way to protect contemporary car systems from cyber attacks because it provides computing economy in addition to the other benefits of improving detection accuracy and reliability.

The suggested model’s improved performance across a number of criteria is demonstrated in Table 9, which compares it to DFSENet, GAN, TCAN-IDS, and XAIEM on the CICIoV2024 dataset. The model suggested is superior to DFSENet (0.963), GAN (0.955), TCAN-IDS (0.946), and XAIEM (0.940) at a rate of 0.976 accuracy, which indicates its superior capability to discriminate between innocent and malicious network traffic. It also attains the best sensitivity (0.962) and specificity (0.986), with a great balance between avoiding false positives and identifying true incursions. The robustness of the proposed model in correct intrusion detection with minimal misclassification rates is confirmed by its precision (0.980), recall (0.968), and F-measure (0.974). Its accuracy in identifying benign traffic is also confirmed by its Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of 0.988. The 0.038 False Negative Rate (FNR) guarantees that there are hardly any uncaught attacks, and the False Positive Rate (FPR) is lowest at 0.015, with very few unnecessary alarms. Also, the capability of the model to have high correlation between the predicted and actual classifications is reflected through the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.973. In terms of computational efficiency, the proposed model is the fastest to train (500 s), test (100 s), and infer (12 ms). In comparison to the proposed model, the proposed model is the most efficient, taking 550s for DFSENet, 600s for GAN, 590s for TCAN-IDS, and 610s for XAIEM to train. For real-time intrusion detection of IoV systems, its inference time (12ms) is the best option as it is faster than DFSENet (15ms), GAN (18ms), TCAN-IDS (16ms), and XAIEM (17ms). These outcomes prove that in addition to achieving better detection accuracy, the introduced model guarantees quicker and more effective performance, making it perfect for protecting next-generation IoV networks from online attacks.

Computational resources

Computational overhead is the extra processing resources, time, and energy needed to run an Intrusion Detection System (IDS), especially in resource-limited settings such as Internet of Vehicles (IoV). Excessive computational overhead can cause threats to be detected late, result in high power consumption, and decrease system efficiency, which is essential in real-time systems. Computational overhead factors involve intricate encryption methods, complex deep learning models, feature selection procedures, and processing of high-dimensional data. To counter this, effective algorithms like the proposed CMSO feature selection algorithm assist in minimizing redundant computations, while models optimized such as DAGSNet balance performance efficiency with accuracy. Further, using parallel processing, light-weight encryption, and edge computing will also reduce computation costs to keep intrusion detection real-time without overly affecting system performance. Computational Overhead in IDS is summarized in the following Table 10.

Discussion

Table 11 presents a comparison of various methods for intrusion detection specifically related to the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). It aims to measure these methods against significant performance evaluation parameters such as:

-

Feature Selection Technique: The method of selecting relevant data features.

-

Classification Model: Type of algorithm used to identify intrusions.

-

Computational Efficiency: The power and time required for processing.

-

Detection Accuracy: The ability of the method to correctly identify attacks.

-

Adaptability to New Threats: The method to show flexibility against attacks it has never seen before.

In essence, Table 11 talks about the merits and demerits of various intrusion detection tactics, including traditional machine learning, deep learning, hybrid models, attention-based models, and the proposed EDL-CMSO model, with respect to securing IoV environments.