Abstract

This study examines a potential treatment for testicular ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury using fisetin (FIS) and quercetin (QUE) in a rat model. Male rats were divided into five groups: a control group, a torsion/detorsion (T/D) group, and three experimental groups treated with FIS, QUE, or a combination of FIS + QUE. Sperm parameters, oxidative stress markers, histopathological features, RT-PCR analysis of apoptotic and antiapoptotic gene expression, and fertility index were evaluated. The results demonstrated that FIS + QUE, FIS, and QUE significantly improved sperm motility and concentration, leading to a higher fertility index, than the reduced metrics in the T/D group. Additionally, levels of MDA and NO were significantly lowered, while CAT, SOD, GPx, and TAC levels increased in the FIS + QUE, FIS, and QUE groups. Histopathological, RT-PCR and fertility analyses also revealed evidence of apoptosis and testicular damage in the T/D group, shown by significant increases in P53, Bax, and caspase-3, along with marked decreases in AKT, PI3K, and Bcl-2. Treatment with FIS and QUE, particularly in combination, significantly improved outcomes, indicating a strong synergistic effect that helps repair damage and enhance reproductive function after T/D injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Testicular torsion, the spermatic cord twisting, is a critical urological emergency primarily affecting newborns and adolescent males1. The condition has an annual incidence rate of 4.5 per 100,000 males aged 1–25 years2. It often leads to the loss of the affected testis and impairs spermatogenesis in 50–95% of patients, significantly reducing fertility and carrying potential medicolegal consequences3. The twisting of the spermatic cord and associated structures causes biochemical and histological alterations, ultimately resulting in testicular dysfunction4. The extent of cord twisting and the duration of torsion are key factors influencing sperm survival and function5. Testicular torsion interrupts blood flow to the testicular tissue, leading to ischemia, during which ATP and other energy-rich phosphates are depleted. At the same time, the concentration of degradation products like hypoxanthine increases6. The subsequent reperfusion causes more severe damage upon detorsion than the ischemic phase alone7. Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury occurs when blood flow is restored following acute ischemia8. Ischemia and reperfusion generate excessive reactive oxygen species9, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β10, and chemokines and cell adhesion molecules, which attract neutrophils and other leukocytes into the testicular tissue11.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause oxidative stress by oxidizing mitochondrial membranes, cellular lipids, proteins, and DNA, leading to cellular dysfunction and germ cell apoptosis in the testes12. The testes are particularly vulnerable to ROS due to their high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids13. ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, peroxynitrite, and nitric oxide, which are commonly present in the environment, cause harmful effects such as protein denaturation, lipid peroxidation, damage to endothelial cells and DNA, and a decline in sperm production and quality. The body’s free radical-scavenging antioxidant system plays a critical role in reducing these damaging effects of ROS13. Timely diagnosis and immediate surgical correction through orchiopexy are essential to prevent testicular damage and subsequent infertility14. Previous studies have explored various interventions, including hypothermia, tunica albuginea incision, chemical treatments, and herbal extracts, in efforts to minimize damage to the male reproductive system following testicular detorsion15,16. However, no widely accepted approach for routine clinical use has been established to prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury after testicular torsion treatment17. Flavonoids, abundant plant secondary metabolites in many herbal medicines, possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, with clinical and preclinical studies also noting their antimicrobial and anti-allergic activities18.

Fisetin (3,7,3,4-tetrahydroxyflavone; FIS) is a flavonoid found in various fruits and vegetables, including strawberries, apples, persimmons, grapes, cucumbers, and onions19. It is known for its many pharmacological properties such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, antitumor, and anti-angiogenic activities20. Its antioxidant effects are believed to come from its chemical structure and ability to regulate critical signaling pathways, particularly those involving protein kinases19. Fisetin has been shown to reduce the growth and spread of tumors such as pancreatic cancer21. Furthermore, fisetin has been shown to reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury in organs like the heart through the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway22.

Quercetin (QUE), also known as 3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone, is a bioactive flavonoid commonly found in various fruits and vegetables such as onions, apples, citrus fruits, and tomatoes, as well as in green and black tea. This compound has potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anticancer properties and is widely available as a dietary supplement23. Quercetin can neutralize free radicals and bind metal ions, which is attributed to the presence of two antioxidant pharmacophores in its chemical structure24. Quercetin can reduce ROS levels even at low concentrations, thereby preventing ROS-induced DNA damage25. Its antitumor activity, mediated through various signaling pathways, has been demonstrated in several types of cancer, including lung and breast cancers26,27.

Since quercetin and fisetin have similar functional characteristics, using them together may have a synergistic effect. When administered simultaneously, these compounds might target different pathways or the same specific pathway. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the impact of giving these two phytoflavonoids, quercetin and fisetin, at the same time on testicular ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury in a rat experimental model and to compare the outcomes of their combined treatment.

Results

Sperm parameters

In Table 1, we observed significant differences in parameters between the T/D group and the other groups, including epididymal concentration, total motility, progressive motility, VAP, VSL, and BCF (p < 0.05). Significant improvements were noted when using FIS and QUE, especially when using both FIS and QUE combined in all groups for these parameters (p < 0.05). No significant differences were found between the T/D group and the other groups for parameters such as STR and LIN (p > 0.05; Table 1). Furthermore, Table 2 indicates that T/D led to a significant reduction in viability, PMF, DNA damage (Fig. 1), and morphology compared to the other groups. However, using FIS, QUE, and especially FIS + QUE showed the potential to improve these parameters (p < 0.05; Table 2).

DNA damage assessment in different experimental groups with a scale bar of 65 μm. White arrow: Normal sperm (green), Black arrow: DNA-damaged sperm (yellow). (A) Control, (B) Torsion/Detorsion (T/D), (C) Fisetin + T/D, (D) Quercetin + T/D, (E) Fisetin + Quercetin + T/D. (Acridine Orange staining, 100x).

Oxidative stress

The results displayed in Fig. 2 indicate that treatment with FIS + QUE, FIS, and QUE resulted in a significant increase in the activities of CAT, SOD, GPx, and TAC compared to the T/D group (p < 0.05; Fig. 2). Conversely, levels of NO and MDA were notably higher in the T/D group compared to the other experimental groups (p < 0.05). However, the administration of FIS + QUE, FIS, and QUE led to a significant reduction in MDA and NO levels compared to the T/D group (p < 0.05; Fig. 2).

Biochemical findings in different experimental groups. T/D: Torsion and detorsion; F: Fisetin; QE: Quercetin. (A) Total antioxidant capacity (TAC); (B) glutathione peroxidase (GPx); (C) superoxide dismutase (SOD); (D) Malondialdehyde (MDA); (E) nitric oxide (NO). Superscripts demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05; Mean ± SD).

Macroscopic and histopathological assessment

The experiment showed that testicular torsion caused significant changes in the structure of the testis, as seen in Fig. 3. These changes included cracks, holes, blockages in blood vessels, the presence of inflammatory cells, accumulation of fluid, and widening of the space between the connective tissues. Leydig cells degraded and had small, dense nuclei, while Sertoli cells became detached from the germ cells and developed irregular, shapeless, and smaller nuclei. The assessment of the torsioned testes using Johnsen’s score confirmed degeneration, shedding, and disorganization of germ cells (Table 3). The group subjected to torsion/detorsion (T/D) showed significantly more histopathological changes compared to the control group, as indicated by the mean Cosentino score (p ≤ 0.05; Table 3). Due to the loss of germ cells during sperm production caused by the 720° torsion/detorsion, the Sertoli cell index (SCI), tubular differentiation index (TDI), and the number of round spermatids (STsD) were notably lower in the T/D group than in the other groups (p ≤ 0.05; Table 3). Analysis of the histological parameters revealed that the testicular biopsy score, spermatogenic index (SPI), Leydig cell nuclear diameter (LCND), and TDI were also reduced in the T/D group compared to the other experimental groups. However, treatment with FIS + QUE, FIS, and QUE significantly improved these parameters compared to the T/D group (p ≤ 0.05; Table 3).

Fisetin and quercetin mitigate testicular damage induced by torsion/detorsion (T/D). Images (A–E) are magnified at 100x with a scale bar of 65 μm, while images (F–J) are magnified at 400x with a scale bar of 20 μm. The structure of testicular tissue was compared among the following experimental groups: (A, F) Control, (B, G) T/D, (C, H) Fisetin + T/D, (D, I) Quercetin + T/D, and (E, J) Fisetin + Quercetin + T/D. In the control group (A, F), germ cells were well-organized in columnar arrangements, with thick walls in the convoluted seminiferous tubules and a high density of sperm within the tubular lumens. White arrows indicate reduced sperm density in the lumen of the seminiferous tubules, particularly in the T/D group (B, G) and the treatment groups: Fisetin + T/D (C, H), Quercetin + T/D (D, I), and Fisetin + Quercetin + T/D (E, J). Asterisks highlight the disorganization and disruption of the germinal epithelium across different groups, with the most severe alterations observed in the T/D group (B, G), followed by the treatment groups: Fisetin + T/D (C, H), Quercetin + T/D (D, I), and Fisetin + Quercetin + T/D (E, J).

qRT-PCR

In the T/D group, mRNA expression levels of P53, Bax, and caspase-3 were elevated, while AKT, PI3K, and Bcl-2 expression significantly decreased. However, treatment with FIS, QUE, and FIS + QUE improved pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic gene expression compared to the T/D group (p < 0.05; Fig. 4).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction findings in different experimental groups. The mRNA expression levels using semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). T/D: Torsion and detorsion; F: Fisetin; QE: Quercetin. (A) P53; (B) Bax; (C) Caspase-3; (D) AKT; (E) PI3K; (F) Bcl-2. Superscripts demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05; Mean ± SD).

Fertility indexes

Table 4 presents the results of the in vivo fertility index. The findings revealed that the T/D group had a significantly lower fertility index than the other groups. In contrast, the administration of FIS + QUE, FIS, and QUE resulted in a marked improvement in the fertility index relative to the T/D group (p ≤ 0.05; Table 4).

Discussion

The twisting of the spermatic cord is a severe emergency in children and can lead to infertility if not treated promptly28. The leading cause of the harmful effects of testicular torsion is the delay in untwisting the cord, which results in the death of germ cells due to inadequate blood flow needed to support the affected tissue29. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause significant damage to cells, affecting both sperm and testicular tissue30. Additionally, high levels of ROS have been linked to male infertility30. External antioxidants may help reduce oxidative stress and minimize tissue damage caused by testicular torsion30. This study examines the effects of T/D and oral administration of FIS and QUE in rats, investigating the potential combined impact of these treatments. The results show that FIS and QUE, particularly when used together, improve treatment effectiveness by enhancing sperm quality and quantity, reducing testicular damage and genes related to cell death, balancing oxidative and antioxidative factors, and increasing fertility indexes (Fig. 5).

The effectiveness of Fisetin and Quercetin on ischemia-reperfusion. The image was created using Microsoft Word 2019 (Version 16.0, Microsoft Corporation, https://www.microsoft.com).

Progressive motility is a crucial aspect of sperm movement within the female reproductive system. It is regulated by mechanisms such as the Ca2+ pathway and the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) pathway31,32. Exposure to a 720° torsion/detorsion (T/D) event has been found to impair spermatogenesis, decreasing sperm count, progressive motility, and forward movement33. Additionally, oxidative stress during reperfusion can harm sperm by oxidizing DNA, membrane lipids, and cellular proteins34. Research has shown that antioxidant treatments can significantly improve sperm parameters in the presence of harmful substances35. Ijaz et al.36 discovered that FIS administration via oral gavage improved rats’ motility in arsenic-induced reproductive damage. Another study revealed that quercetin supplementation helped reduce reductions in sperm count, motility, viability, and HOS-positive sperm, decreasing morphological abnormalities in diabetic rats37. Our results, supported by recent studies, show that administration of FIS and QUE, individually and in combination, significantly improves essential parameters such as sperm count, motility, morphology, viability, DNA integrity, and plasma membrane function. These improvements may be attributed to the role of antioxidants in reducing oxidative stress and minimizing structural and functional sperm abnormalities.

Several studies have shown that torsion and detorsion (T/D) hurt spermatogenesis. Histopathological evidence has revealed germ cell loss in T/D-induced conditions, irrespective of disruptions in Leydig and Sertoli cells15. Previous findings suggest that T/D-induced germ cell loss is associated with intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways38. Additionally, Bozlu and colleagues have indicated that germ cell loss under T/D conditions is linked to increased levels of testicular lipid peroxidation, nitric oxide (NO), and myeloperoxidase (MPO)39. Various studies have shown that testicular torsion (TT) reduces seminiferous tubule diameter and germinal epithelial thickness and impairs sperm maturation38,39. Concerning sperm quality, it has been demonstrated that T/D reduces sperm concentration while increasing sperm abnormalities38. Aktoz et al.40 found that ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) significantly damages the testis, while treatment with QUE improved histopathological parameters, enhanced testicular eNOS expression, and increased germ cell apoptosis. In another study, quercetin was shown to ameliorate cyanide-induced testicular damage in Wistar rats41. Similarly, research demonstrated that FIS could improve histological damage caused by monosodium glutamate (MSG)-induced testicular toxicity in rats42. Our study also highlights the presence of multinucleated giant cells as critical markers of severe disruption of spermatogenesis in I/R injury, which is consistent with previous findings. As found in testicular I/R injury models, these multinucleated giant cells represent one of the critical indicators of problems in germ cell maturation as reported by Seker et al. (2022) and Sagir et al. (2023)43,44. In addition to fisetin and quercetin in our study, which could effectively alleviate testicular damage and improve related abnormalities, studies such as those by Seker et al. (2022) highlight the potential of riociguat to regulate cellular pathways through soluble guanylate cyclase, thereby demonstrating its ability to ameliorate testicular damage43. Similarly, Sagir et al. (2023) identified visnagin as a potent modulator of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation and demonstrated its protective effect against testicular I/R injury44.

In recent decades, several studies, including those from our research group, have shown that oxidative stress is crucial in testicular damage caused by ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury15,45. Under I/R conditions, there is an increase in lipid peroxidation in the testes, along with a decrease in total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and the activity of key antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). This oxidative stress is not only due to reduced oxygen supply but is also worsened when the testicular antioxidant defense mechanisms are compromised45. One study demonstrated that FIS can improve oxidative stress-related enzymes in a rat model of arsenic exposure36. At the same time, another found that FIS exhibits antioxidant effects by reducing oxidants like H2O2, NO, and NOX4, and enhancing antioxidant capacity by increasing GSH levels42. Similarly, QUE improved oxidative parameters in acrylamide-induced retinal damage in diabetic rats46. The reduction in MDA and NO levels observed in our study supports the role of fisetin and quercetin as powerful antioxidants that can effectively attenuate lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage. The observed reduction in oxidative stress is consistent with the findings of Seker et al. (2024), who demonstrated the gonadoprotective effect of trans-anethole by modulating STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways47. Nitric oxide (NO), a free radical soluble in water and lipids, is key in regulating blood flow under normal and pathological conditions48. NO levels are associated with I/R injury, as NO synthase activity and NO levels increase during ischemia. However, excess superoxide radicals (O2−) are generated upon reperfusion, and the interaction between NO and O2 − exacerbates cellular damage49. Our study elevated NO levels in the I/R group but partially restored in the drug-treated groups. This supports the idea that FIS and QUE help protect the testis from I/R injury by inhibiting NO production. The combined administration of FIS and QUE was statistically more effective in reducing NO levels.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, involves various kinases and cysteine proteases known as caspases. Unlike other types of cell death, genetically driven apoptosis, which includes DNA fragmentation, does not trigger inflammation50. Numerous studies have demonstrated that testicular ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) activates germ cell apoptosis due to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by neutrophils51. Previous research using a rat model revealed that torsion/detorsion (T/D) induces germ cell-specific apoptosis, showing significantly increased Bax mRNA expression and decreased Bcl-2 expression in the T/D group compared to the control group52. The antioxidant hesperidin has been shown to exert anti-apoptotic effects in several studies53,54. Arsenic poisoning in rats significantly elevated Bax and caspase-3 expression while reducing Bcl-2 expression, but treatment with FIS reversed this by increasing Bcl-2 and decreasing Bax and caspase-3, demonstrating FIS’s anti-apoptotic effect36. Another study showed that QUE inhibited the increased expression of p53, Bax, caspase-3, and MDA in rats exposed to chronic, unpredictable stress55. Our research on modulating apoptotic markers, including caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax, supports the protective and complementary effects of quercetin and fisetin. Furthermore, Sagir et al. (2023) identified the pathways for apoptosis and proliferation, which is consistent with our findings44.

Testicular torsion can lead to a compromised blood testis barrier, causing the release of cytokines that trigger widespread apoptosis in the germinal epithelium of the unaffected testis. This condition significantly increases the risk of infertility in individuals with testicular torsion56. One study found a decrease in pregnancy rates and the number of embryos following testicular torsion/detorsion (T/D), associated with reduced serum testosterone levels and diminished sperm quality57. The use of exogenous antioxidants has been suggested as a potential strategy to improve sperm survival and motility in patients with testicular dysfunction58. In this study, fertility indices declined after T/D treatment. However, the administration of FIS or QUE, particularly in combination, significantly improved fertility indices. This improvement may be attributed to enhanced sperm motility, viability, and membrane integrity, potentially leading to increased fertility rates in rats59. Lu et al.60 and Zhang et al.61 propose that these improvements could be linked to enhanced sperm fertilization capacity. For these compounds to reach their full clinical potential, future research should optimize dosage and timing of administration.

Conclusion

After undergoing testicular torsion and detorsion, both FIS and QUE were found to be effective in preventing ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury to the testis. The results indicate that when these drugs are administered intraperitoneally before detorsion, the testis experiences less damage from I/R injury. However, a limitation of this study is that the precise timing and dosage for maximizing the effects of FIS and QUE have not been fully established. Future studies should investigate various doses and administration timings to determine the optimal treatment for potential clinical application.

Methods

Chemicals

The chemical compounds required for the study were sourced from well-known suppliers, including Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Animals

Fifty-six adult male Wistar rats weighing 260 and 300 g and aged 12 to 14 weeks were acquired from the Animal Resource Center at Urmia University in Urmia, Iran. The rats were kept in a controlled environment with a stable temperature of 20–22 °C, proper ventilation, a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and a relative humidity of 50 ± 10%. They were housed in plastic cages, provided an unlimited supply of standard laboratory feed, and given free access to tap water. Before the experiment, the rats underwent a one-week acclimatization period.

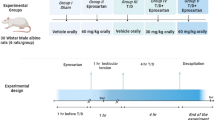

Experimental protocol

Following a week of acclimatization, we randomly divided the rats into five groups, each comprising eight animals:

-

Control group: The control group underwent sham surgery without testicular I/R injury.

-

Torsion/detorsion [T/D] group: The T/D group experienced 720° torsion-induced ischemia for 2 h.

-

Fisetin (FIS) group: The FIS group experienced ischemia induced by 720° torsion for 2 h and 30 min before testicular detorsion, and the rats received FIS at a dose of 20 mg/kg/IP62.

-

Quercetin (QUE) group: The QUE group experienced 720° torsion-induced ischemia for 2 h, and 30 min before testicular detorsion, rats received QUE at a dose of 20 mg/kg/IP63.

-

FIS + QUE group: The FIS + QUE group experienced 720° torsion-induced ischemia for 2 h. Thirty minutes before testicular detorsion, the rats received F at a dose of 20 mg/kg/IP + QUE at a Dose of 20 mg/kg/IP.

Surgical procedure

Aseptic techniques were used during the process. The left testis was used to measure oxidative stress after 30 days, while the right testis and epididymis were removed for sperm analysis and histology. Both xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (80 mg/kg) were used for anesthesia. After a 720° clockwise rotation, the testicles were unhorsed two hours later and stabilized with 5/0 silk sutures. For sperm analysis, the cauda epididymis of the right testis was separated and preserved in formalin15.

Epididymal sperm collection

The male rats were humanely euthanized via an intraperitoneal injection of xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg) and ketamine hydrochloride (150 mg/kg)64. Sperm were harvested from the cauda epididymis of the testes. The cauda epididymis was fragmented into small pieces and placed in a Petri dish containing 1 mL of human tubal fluid medium, including calcium chloride, glucose, and potassium chloride. The dish was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 30 min65.

Sperm analysis

Epididymal sperm count

The sperm were diluted in distilled water at a ratio of 1:5, rendered nonviable, and counted using a Neubauer hemacytometer. Fragments of epididymal tissue were carefully gathered and weighed on a high-precision digital laboratory scale with a capacity of 0.0001 g66.

Epididymal sperm motility

The CASA system (Test Sperm 3.2, Videotest, St. Petersburg, Russia), configured for analysis of rat sperm, was employed to quantify sperm concentration and kinetic parameters (Table 5). The system assessed the following parameters: total motility (%), progressive motility (%), curvilinear velocity (VCL; µm/s), straight-line velocity (VSL; µm/s), average path velocity (VAP; µm/s), straightness (STR; %), linearity (LIN; %), amplitude of lateral head displacement (ALH; µm/s), and beat-cross frequency (BCF; Hz). For analysis, approximately ten µL of the sperm solution was placed on a microscope slide. The slide was examined using dark-field or phase-contrast microscopy. Five microscopic fields of at least 500 spermatozoa were evaluated32.

Epididymal sperm viability and morphology

Sperm viability and morphology were assessed using the eosin-nigrosin staining method according to the World Health Organization procedure67. This involved mixing one part sperm with two parts 1% eosin and observing the sample under a light microscope at 400x magnification. The method employed involved staining non-viable spermatozoa with eosin, which imparts a red color. In contrast, viable spermatozoa remained unstained, thereby facilitating an assessment of sperm viability. Additionally, the eosin-nigrosin staining technique facilitated the identification of abnormal spermatozoa. Those exhibiting irregular head, neck, or tail patterns were classified as abnormal. For each sample, 200 sperm were examined at 400x magnification, and the findings were expressed as percentages32.

Epididymal sperm DNA damage

The acridine orange (AO) staining technique was used to differentiate denatured, native, and double-stranded DNA in sperm chromatin. Denatured DNA showed the most intense fluorescence. The smears were first treated with acetic acid and Conroy’s fixative mixture in a 1:3 ratio for 2 h, then air-dried for 5 min. After that, they were immersed in a stock solution containing 1 mg of AO dissolved in 1000 mL of filtered water, which was kept in a dark chamber at 4 °C for 5 min. The spermatozoa were then examined under a fluorescent microscope at 400x magnification, where sperm with red or yellow coloration were identified as damaged or abnormal32,68.

Sperm plasma membrane functionality (PMF)

The hypo-osmotic swelling test evaluated sperm progressive motility factor (PMF). In this test, 100 µL of a hypo-osmotic solution containing 1.351 g/L of fructose and 0.735 g/L of sodium citrate was mixed with ten µL of the sperm sample and then kept at 37 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the functionality of the sperm plasma membrane was assessed under a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus, BX41, Tokyo, Japan) at 400x magnification. Sperm with coiled or swollen tails were considered to have functional plasma membranes32. The same hypo-osmotic swelling test was also used to identify sperm exhibiting the progressive motility factor (PMF). The test combined 100 µL of a hypo-osmotic solution containing fructose (1.351 g/L) and sodium citrate (0.735 g/L) with ten µL of the sperm sample, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. The assessment of sperm plasma membrane function was performed using a phase-contrast microscope at 400x magnification, with coiled or swollen tails serving as key indicators of efficient PMF.

Evaluation of oxidative stress

A 20–30 mg sample of testicular tissue was homogenized in 1000 µL of lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min. The resulting supernatant was collected for biochemical analysis to assess enzymatic antioxidant activity. All measurements were conducted using commercial kits from Navand Salamat (Navand Salamat Company, Urmia, Iran). Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined using a commercial MDA assay kit, with sample absorbance measured at 523 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the results expressed in nmol/mg of protein. Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in the testis was measured using a TAC assay kit, and the results were also reported as nmol/mg protein. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) levels were assessed using a GPx assay kit, with concentrations expressed as mU/mg protein. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured with a commercial SOD kit, with activity determined based on the reduction in color intensity at 405 nm, and the results expressed as U/mg protein. Catalase (CAT) activity was evaluated using a commercial CAT kit, following a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, absorbance measured at 550 nm, and results reported in U/mg protein. Nitric oxide (NO) levels were assessed using an NO assay kit. Sample absorbance was read at 570 nm, and NO concentration was reported as nmol/mg protein.

Macroscopic and histopathological evaluation

In all experimental groups, testis and epididymis weights were recorded in g using a digital scale, and the percentage of testis-to-body weight was calculated. The right testes of the rats, fixed in 10% formalin, were dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Thin sections, seven µm thick, were prepared with a rotary microtome and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained slides were examined under a light microscope (Olympus Model BH-2, Tokyo, Japan). The seminiferous tubule diameter (STsD) was calculated by measuring 200 randomly selected round or nearly round cross-sections of seminiferous tubules. The two perpendicular diameters of each cross-section were measured using an ocular micrometer (Model CHT, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the average values were determined.

Furthermore, the Sertoli Cell Index (SCI), Reproductive Index (RI), and Meiotic Index (MI) were evaluated using 60 randomly chosen seminiferous tubules per group. The SCI represents the ratio of Sertoli cells, identifiable by distinct nuclei and nucleolus, to the number of germ cells in the seminiferous tubules. The RI reflects the number of tubules with germ cells that have reached at least the mid-level of spermatogonia or higher. The MI, calculated as the ratio of round spermatids to pachytene primary spermatocytes, indicates the number of cells lost during division. The Leydig Cell Nuclear Diameter (LCND) was measured using a calibrated ocular micrometer, following the method described by Elias and Hyde. The Tubular Differentiation Index (TDI) was defined as the number of seminiferous tubules containing at least three fully developed germ cells, and the Spermatogenic Index (SPI) was defined as the number of seminiferous tubules containing sperm cells. These indices were determined by examining 200 transverse sections of seminiferous tubules from each animal (100 per testis)69.

The mean testicular biopsy score was determined to assess the stages of spermatogenesis using the Johnsen scoring system, which ranges from 1 to 10. Two hundred seminiferous tubules were analyzed using a light microscope (CHT model, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Testicular damage was assessed using the Cosentino scoring system, which categorizes damage into four grades68.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assessment

The SinaSyber Blue HF-qPCR Mix from CinnaGen in Tehran, Iran, was used for qRT-PCR analysis on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System from Applied Biosystems in the USA. The reaction volume was 25 µL, and cDNA samples were analyzed for the relative gene expression of Bcl-2, Bax, P53, caspase-3, AKT, and PI3K, with 18SrRNA as the reference gene (Table 6). The qRT-PCR thermal cycling protocol included an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The relative gene expression was calculated using the formula: Relative expression = 2−(SΔct−CΔct), where SΔct is obtained by subtracting the cycle threshold (ct) value of the reference gene from that of the target gene, and CΔct is the corresponding ct value for internal control samples. The relative expression data was normalized for statistical analysis using a log10 transformation70. The reverse transcription-PCR primers used are listed in Table 650,65,71,72,73.

Fertility indices assessment

All experimental groups, except the surgical group, comprised eight male and sixteen female rats. The fertility indices, including the female mating index (%), male mating index (%), pregnancy index (%), and male fertility index (%), were measured74.

Statistical analysis

The data from the study was analyzed using the statistical software package SPSS (version 26.0, IBM Corporation, Chicago, USA). We used the one-way ANOVA to identify significant differences between the various groups under study. Subsequently, we employed Tukey’s post hoc test to determine precisely which of the groups exhibited statistically significant differences in comparison with one another. We considered a p-value of ≤ 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TM:

-

Total motility

- PM:

-

Progressive motility

- VCL:

-

Curvilinear velocity

- VSL:

-

Straight-line velocity

- VAP:

-

Average path velocity

- STR:

-

Straightness

- LIN:

-

Linearity

- ALH:

-

Amplitude of lateral head displacement

- BCF:

-

Beat-cross frequency

- PMF:

-

Plasma membrane functionality

- TAC:

-

Total antioxidant capacity

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- GPx:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

References

Ünsal, A. et al. Propofol attenuates reperfusion injury after testicular torsion and detorsion. World J. Urol. 22, 461–465 (2004).

Howe, A. S. & Palmer, L. S. Testis torsion: recent lessons. Can. J. Urol. 23, 8602 (2016).

Perrotti, M., Badger, W., Prader, S. & Moran, M. E. Medical malpractice in urology, 1985 to 2004: 469 consecutive cases closed with indemnity payment. J. Urol. 176, 2154–2157 (2006).

Tamamura, M. et al. Protective effect of Edaravone, a free-radical scavenger, on ischaemia‐reperfusion injury in the rat testis. BJU Int. 105, 870–876 (2010).

Shimizu, S. et al. Testicular torsion–detorsion and potential therapeutic treatments: A possible role for ischemic postconditioning. Int. J. Urol. 23, 454–463 (2016).

Elshaari, F. A., Elfagih, R. I., Sheriff, D. S. & Barassi, I. F. Oxidative and antioxidative defense system in testicular torsion/detorsion. Indian J. Urol. 27, 479–484 (2011).

Arena, S. et al. Medical perspective in testicular ischemiareperfusion injury. Exp. Ther. Med. 13, 2115–2122 (2017).

Minutoli, L. et al. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) during testicular ischemia–reperfusion injury in nuclear factor-κB knock-out mice. Life Sci. 81, 413–422 (2007).

Yazihan, N., Ataoglu, H., Koku, N., Erdemli, E. & Sargin, A. K. Protective role of erythropoietin during testicular torsion of the rats. World J. Urol. 25, 531–536 (2007).

Karna, K. K., Choi, B. R., Kim, M. J., Kim, H. K. & Park, J. K. The effect of schisandra chinensis baillon on cross-talk between oxidative stress, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, and mitochondrial signaling pathway in testes of varicocele-induced SD rat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5785 (2019).

Mahmoud, N. M. & Kabil, S. L. Pioglitazone abrogates testicular damage induced by testicular torsion/detorsion in rats. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 22, 884 (2019).

Kostakis, I. D. et al. Erythropoietin and sildenafil protect against ischemia/reperfusion injury following testicular torsion in adult rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 13, 3341–3347 (2017).

Erdemir, F. et al. The comparison of the effect of Isoeugenol-based novel potent antioxidant and melatonin on testicular tissues in torsion induced rat model. Androl. Bull. 19, 111–116 (2017).

Ringdahl, E. & Teague, L. Testicular torsion. Am. Fam Physician. 74, 1739–1743 (2006).

Mostahsan, Z., Azizi, S., Soleimanzadeh, A. & Shalizar-Jalali, A. The protective roles of Mito-TEMPO on testicular ischemiareperfusion injury based on biochemical and histopathological evidences in mice. Iran. J. Vet. Surg. 19, 97–105 (2024).

Mohammadnejad, K., Mohammadi, R., Soleimanzadeh, A., Shalizar-Jalali, A. & Sarrafzadeh-Rezaei, F. The effect of β-Cryptoxanthin on testicular Ischemia-Reperfusion injury in a rat model: evidence from testicular histology. Iran. J. Vet. Surg. https://doi.org/10.30500/ivsa.2024.457134.1405 (2024).

Gultekin, A. et al. The effect of tunica albuginea incision on testicular tissue after detorsion in the experimental model of testicular torsion. Urol. J. 15, 32–39 (2018).

Kim, Y. H., Kim, J., Park, H. & Kim, H. P. Anti-inflammatory activity of the synthetic chalcone derivatives: Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase-catalyzed nitric oxide production from lipopolysaccharide-treated RAW 264.7 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30, 1450–1455 (2007).

Khan, N., Syed, D. N., Ahmad, N. & Mukhtar, H. Fisetin: a dietary antioxidant for health promotion. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 151–162 (2013).

Antika, L. D. & Dewi, R. M. Pharmacological aspects of Fisetin. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 11, 1–9 (2021).

Murtaza, I., Adhami, V. M., Hafeez, B., Bin, Saleem, M. & Mukhtar, H. Fisetin, a natural flavonoid, targets chemoresistant human pancreatic cancer AsPC-1 cells through DR3‐mediated Inhibition of NF‐κB. Int. J. Cancer. 125, 2465–2473 (2009).

Shanmugam, K., Ravindran, S., Kurian, G. A. & Rajesh, M. Fisetin confers cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury by suppressing mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase 3β activity. Oxid Med Cell Longev 9173436 (2018). (2018).

Passioti, M., Maggina, P., Megremis, S. & Papadopoulos, N. G. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 14, 1–11 (2014).

Henderson, J. T., Webber, E. M. & Sawaya, G. F. Screening for ovarian cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 319, 595–606 (2018).

Egert, S. et al. Daily Quercetin supplementation dose-dependently increases plasma Quercetin concentrations in healthy humans. J. Nutr. 138, 1615–1621 (2008).

Mansourizadeh, F. et al. Efficient synergistic combination effect of Quercetin with Curcumin on breast cancer cell apoptosis through their loading into Apo ferritin cavity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 191, 110982 (2020).

Choi, J. A. et al. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by Quercetin. Int. J. Oncol. 19, 837–844 (2001).

Lee, J. W. et al. Inhaled hydrogen gas therapy for prevention of testicular ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J. Pediatr. Surg. 47, 736–742 (2012).

Mogilner, J. G. et al. Effect of diclofenac on germ cell apoptosis following testicular ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 22, 99–105 (2006).

Aitken, R. J. & Baker, M. A. Oxidative stress, sperm survival and fertility control. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 250, 66–69 (2006).

Ramazani, N. et al. Reducing oxidative stress by κ-carrageenan and C60HyFn: the post-thaw quality and antioxidant status of Azari water Buffalo bull semen. Cryobiology 111, 104–112 (2023).

Ramazani, N. et al. The influence of L-proline and fulvic acid on oxidative stress and semen quality of Buffalo bull semen following cryopreservation. Vet. Med. Sci. 9, 1791–1802 (2023).

Puja, I. K. et al. Preservation of semen from Kintamani Bali dogs by freezing method. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 6, 158 (2019).

Camhi, S. L., Lee, P. & Choi, A. M. The oxidative stress response. New. Horiz. 3, 170–182 (1995).

Kurcer, Z., Hekimoglu, A., Aral, F., Baba, F. & Sahna, E. Effect of melatonin on epididymal sperm quality after testicular ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Fertil. Steril. 93, 1545–1549 (2010).

Ijaz, M. U. et al. Mechanistic insight into the protective effects of Fisetin against arsenic-induced reproductive toxicity in male rats. Sci. Rep. 13, 3080 (2023).

Yelumalai, S., Giribabu, N., Karim, K., Omar, S. Z. & Salleh, N. Bin. In vivo administration of Quercetin ameliorates sperm oxidative stress, inflammation, preserves sperm morphology and functions in streptozotocin-nicotinamide induced adult male diabetic rats. Archives Med. Sci. 15, 240–249 (2019).

Minas, A. et al. Testicular torsion in vivo models: Mechanisms and treatments. Andrology 11, 1267–1285 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.13418

Bozlu, M. et al. Inhibition of Poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) Polymerase decreases long-term histologic damage in testicular ischemia-reperfusion injury. Urology 63, 791–795 (2004).

Aktoz, T., Kanter, M. & Aktas, C. Protective effects of Quercetin on testicular torsion/detorsion-induced ischaemia‐reperfusion injury in rats. Andrologia 42, 376–383 (2010).

Oyewopo, A. O. et al. Regulatory effects of Quercetin on testicular histopathology induced by cyanide in Wistar rats. Heliyon 7, e07662 (2021).

Rizk, F. H. et al. Fisetin ameliorates oxidative glutamate testicular toxicity in rats via central and peripheral mechanisms involving SIRT1 activation. Redox Rep. 27, 177–185 (2022).

Seker, U. et al. Targeting soluble guanylate cyclase with Riociguat has potency to alleviate testicular ischaemia reperfusion injury via regulating various cellular pathways. Andrologia 54, e14616 (2022).

Sagir, S., Seker, U., Ozoner, M. P., Yuksel, M. & Demir, M. Oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation, and proliferation modulator function of Visnagin provide gonadoprotective activity in testicular ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 9968–9977 (2023).

Shamsi-Gamchi, N., Razi, M. & Behfar, M. Testicular torsion and reperfusion: evidences for biochemical and molecular alterations. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 23, 429–439 (2018).

Zargar, S., Siddiqi, N. J., Ansar, S. & Alsulaimani, M. S. El ansary, A. K. Therapeutic role of Quercetin on oxidative damage induced by acrylamide in rat brain. Pharm. Biol. 54, 1763–1767 (2016).

Seker, U. et al. Regulation of STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways by trans-Anethole in testicular ischemia-reperfusion injury and its gonadoprotective effect. Rev. Int. Androl. 22, 57–67 (2024).

Akgür, F. M., Kilinç, K., Aktuǧ, T. & Olguner, M. The effect of allopurinol pretreatment before detorting testicular torsion. J. Urol. 151, 1715–1717 (1994).

Koltuksuz, U. et al. Testicular nitric oxide levels after unilateral testicular torsion/detorsion in rats pretreated with caffeic acid phenethyl ester. Urol. Res. 28, 360–363 (2000).

Dhulqarnain, A. O. et al. Pentoxifylline improves the survival of spermatogenic cells via oxidative stress suppression and upregulation of PI3K/AKT pathway in mouse model of testicular torsion-detorsion. Heliyon 7, e06868 (2021).

Lysiak, J. J., Nguyen, Q. A. T., Kirby, J. L. & Turner, T. T. Ischemia-reperfusion of the murine testis stimulates the expression of Proinflammatory cytokines and activation of c-jun N-terminal kinase in a pathway to E-selectin expression. Biol. Reprod. 69, 202–210 (2003).

Turner, T. T., Tung, K. S. K., Tomomasa, H. & Wilson, L. W. Acute testicular ischemia results in germ Cell-Specific apoptosis in the rat. J. Urol. 160, 1944 (1998).

Celik, E. et al. Protective effects of hesperidin in experimental testicular ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Archives Med. Sci. 12, 928–934 (2016).

Justin Thenmozhi, A., Raja, W., Manivasagam, T. R., Janakiraman, T., Essa, M. M. & U. & Hesperidin ameliorates cognitive dysfunction, oxidative stress and apoptosis against aluminium chloride induced rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 20, 360–368 (2017).

Bin-Jaliah, I. Quercetin Inhibits, ROS-p53-Bax-caspase-3 axis of apoptosis and augments gonadotropin and testicular hormones in chronic unpredictable Stress-Induced testis injury. Int. J. Morphology 39, 839–847 (2021).

Hadziselimovic, F., Geneto, R. & Emmons, L. R. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J. Urol. 160, 1158–1160 (1998).

Shokoohi, M. et al. Investigating the effects of onion juice on male fertility factors and pregnancy rate after testicular torsion/detorsion by intrauterine insemination method. Int. J. Womens Health Reprod. Sci. 6, 499–505 (2018).

Qamar, A. Y. et al. Role of antioxidants in fertility preservation of sperm—A narrative review. Anim. Biosci. 36, 385 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Effect of Procyanidin on canine sperm quality during chilled storage. Vet. Sci. 9, 588 (2022).

Lu, X. et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoTEMPO improves the post-thaw sperm quality. Cryobiology 80, 26–29 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Mito-Tempo alleviates Cryodamage by regulating intracellular oxidative metabolism in spermatozoa from asthenozoospermic patients. Cryobiology 91, 18–22 (2019).

Prem, P. N. & Kurian, G. A. Fisetin attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by improving mitochondrial quality, reducing apoptosis and oxidative stress. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 395, 547–561 (2022).

Chi, K. K. et al. Comparison of Quercetin and Resveratrol in the prevention of injury due to testicular torsion/detorsion in rats. Asian J. Androl. 18, 908–912 (2016).

de Lima, A. Fertility in male rats: disentangling adverse effects of arsenic compounds. Reprod. Toxicol. 78, 130–140 (2018).

Soleimanzadeh, A., Kian, M., Moradi, S. & Mahmoudi, S. Carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) fruit hydro-alcoholic extract alleviates reproductive toxicity of lead in male mice: evidence on sperm parameters, sex hormones, oxidative stress biomarkers and expression of Nrf2 and iNOS. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 10, 35 (2020).

Anbara, H. et al. Repro-protective role of Royal jelly in phenylhydrazine-induced hemolytic anemia in male mice: histopathological, embryological, and biochemical evidence. Environ. Toxicol. 37, 1124–1135 (2022).

Organization, W. H. Department of reproductive health and research. WHO Lab. Man. Examination Process. Hum. Semen. 5, 21–22 (2010).

Baqerkhani, M., Soleimanzadeh, A. & Mohammadi, R. Effects of intratesticular injection of hypertonic mannitol and saline on the quality of Donkey sperm, indicators of oxidative stress and testicular tissue pathology. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 99 (2024).

Elias, H. & Hyde, D. M. An elementary introduction to stereology (quantitative microscopy). Am. J. Anat. 159, 411–446 (1980).

Soleimanzadeh, A., Pourebrahim, M., Delirezh, N. & Kian, M. Ginger ameliorates reproductive toxicity of formaldehyde in male mice: evidences for Bcl-2 and Bax. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 7, 259–266 (2018).

Taghavi, S. A., Valojerdi, M. R., Moghadam, M. F. & Ebrahimi, B. Vitrification of mouse preantral follicles versus slow freezing: morphological and apoptosis evaluation. Anim. Sci. J. 86, 37–44 (2015).

Sheikhbahaei, F., Khazaei, M., Rabzia, A., Mansouri, K. & Ghanbari, A. Protective effects of thymoquinone against methotrexate-induced germ cell apoptosis in male mice. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 9, 541 (2016).

Han, X. et al. Caspase-mediated apoptosis in the cochleae contributes to the early onset of hearing loss in A/J mice. ASN Neuro. 7, 1759091415573985 (2015).

Sadeghirad, M., Soleimanzadeh, A., Shalizar-Jalali, A., & Behfar, M. Synergistic protective effects of 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylglycol and Hydroxytyrosol in male rats against induced heat stress-induced reproduction damage. Food Chem. Toxicol. 190, 114818 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank the members of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Urmia University Research Council for the approval and support of this research.

Funding

This work was supported by Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology of Urmia University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ: Investigation, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. AS: Investigation, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. MB: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Animal Ethics Committee of Urmia University approved the experiments, and all methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (IR-UU-2361/PD/3). Additionally, the study adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines (Animals in Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments) and complied with institutional and national regulations for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zolfaghari, S., Soleimanzadeh, A. & Baqerkhani, M. The synergistic activity of fisetin on quercetin improves testicular recover in ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Sci Rep 15, 12053 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96413-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96413-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Establishment of safe and efficient infertile goat model using cyclophosphamide and its implications at the cellular and molecular level

Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences (2025)

-

Allicin and hesperidin protect sperm production from environmental toxins in mice

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

β-Glucan and resveratrol mitigate lead induced reproductive toxicity in male mice

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Oral niacin mitigates heat-induced reproductive impairments in male mice

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The effects of heavy smoking on oxidative stress, inflammatory biomarkers, vascular dysfunction, and hematological indices

Scientific Reports (2025)