Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic altered the vaccine development paradigm with accelerated timelines from concept through clinical safety and efficacy. Characterization and release assays for vaccine programs were developed under similar time constraints to support bioprocess development, scaleup and formulation. During the development of these vaccines, SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) emerged requiring integration of additional antigens into the target product profile. Biochemical testing to support the addition of new antigen variants (identity, quantity, antigenicity/potency) needed substantial re-development. Here we present a reversed-phase high-performance liquid-chromatography method for antigen purity with orthogonal identification characterization comprising of Simple Wes and liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) to support accelerated process development for recombinant protein vaccines. This suite of assays was deployed to support rapid, scientific decision-making enabling the transition from completion of a placebo-controlled dose-ranging Phase 2 study to the start of the global Phase 3 safety and efficacy trial in less than 2 weeks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

New vaccine development historically has taken 15–20 years from initial scientific discovery to market authorization and policy recommendations. The long development timelines include chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) process development activities and clinical studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy. The analytical and process development activities are specific for each vaccine platform, while the clinical development, including discovery and early development, late development and implementation are linked to the infectious disease indication for the pathogen of interest1. Regardless of the manufacturing platform, final process scale up and good manufacturing practice (GMP) activities need to be in place before Phase 2 clinical study enrolment to ensure the investigational vaccine administered generates safety, immunogenicity and dose ranging data to support Phase 3 clinical trials2,3,4. There are multiple strategies to accelerate vaccine process development. Learnings used to develop prior vaccines from a common platform (i.e. mRNA, protein subunit, attenuated viral vector) can be leveraged to achieve certain similar up stream manufacturing processes including synthetic reagents, growth media, and substrate harvest density. Also, downstream purifications, stabilizing formulations, and finish/fill process can be harmonized for final drug substance and drug product which have similar physical and chemical properties. However, vaccine specific downstream processing (purification and formulation) which is based on the different physical and chemical properties of the vaccine components (i.e. recombinant protein, polysaccharide conjugate) are normally unique to the vaccine and only limited platform learnings apply. In those instances, comprehensive analytical characterization must be completed to define the final CMC process development for late-stage clinical trial materials and commercial product.

The vastly accelerated timelines required for release of vaccines under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) during the COVID-19 pandemic were achieved by unprecedented cooperation between government funding agencies, manufacturers, and regulatory authorities to scale up CMC and develop these vaccines at risk5,6,7,8,9. Regulatory guidance to achieve EUA was harmonized worldwide providing a clear development path for all vaccine candidates10,11,12. Processes normally performed in series were conducted in parallel regardless of the financial risks. Clinical trials were combined as either Phase 1/2 or Phase 2/3 studies with multiple Phase 3 studies running in parallel13,14,15,16,17. The first vaccines approved under EUA achieved rapid initiation of Phase 3 studies one month after completion of the Phase 2 clinical trials18,19,20,21,22. The process development needed to support vaccine CMC included upstream & downstream processing, physical/chemical characterization of candidates, release assays, stability programs, formulation improvements and qualification/validation activities to ensure lot-to-lot reproducibility. All these activities needed to be accelerated to achieve the successful completion of Phase 3 testing to be considered for EUA. The Sanofi recombinant COVID-19 vaccine process development leveraged the proprietary baculovirus-vector expression system used to produce commercial vaccines. Downstream processing, including protein purification, initially utilized depth filtration, affinity and hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC), and tangential flow filtration23, but the purity and yield were insufficient to proceed to Phase 3 clinical development. The commercial scale downstream processing was completely revised replacing the first steps (depth filtration, affinity and HIC) with ion-exchange and multimodal chromatography to achieve improved yields and purity (> 90–95%)17,24.

In this article, we describe a set of protein separation and characterization techniques that were developed early in the Sanofi recombinant protein COVID-19 vaccine project to provide enhanced analytical throughput, specificity, precision, and accuracy throughout the vaccine program. The initial SDS-PAGE and Western Blot methods used for protein purity and identification were replaced with a combination of reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), Simple Wes microcapillary detection and liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry analysis (LC/MS/MS). This suite of methods was of particular importance for rapid advancement of downstream purification development towards the commercial scale process and comparability testing as the project transitioned between clinical trials. This led to advancement of the Phase 3 clinical trials nine days after the completion of the Phase 2 dose ranging clinical study17,22,25,26,27.

Results

Orthogonal analytical techniques combining high throughput acquisition and analysis with superior resolving power for protein purity were implemented to support bioprocess improvements for vaccine clinical material production. RP-HPLC methods provide numerous advantages over more traditional methods for protein separation and purity evaluation such as SDS-PAGE including sample throughput and consistency, higher resolution, as well as ease of coupling to more comprehensive techniques (e.g. MS) for orthogonal characterization. Improvements in column chemistry stationary phase and particle design, as well as system performance (ultra-high pressure HPLC) allow for better overall protein separations by HPLC28. The RP-HPLC method described in this paper was initially developed for the purity evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen at the purified drug substance stage. However, the method also found applications in support of formulation and stability as well as process optimization to track improvements in relative yield and intermediate antigen purification through downstream process development.

RP-HPLC methods for protein separation are run in a denatured environment induced by pH, organic mobile phases, and the interaction of the protein analytes with the hydrophobic sidechains of the functionalized stationary phase. Although there are many physiochemical characteristics that contribute to the separation of different complex biomolecules, protein separation is a function of the relative hydrophobicity of the primary amino acids’ hydrophobic and aromatic residues with the stationary phase. These complex interactions allow for the potential to separate proteins with different amino acid sequences, even when they are similar in molecular weight. A BioResolve reversed-phase (RP) column was selected for RP-HPLC analysis as it provided good resolution of the spike antigen and host cell proteins (HCPs), which was beneficial for the analysis of both process intermediate samples and purified drug substance. The BioResolve RP column has a polyphenyl stationary phase ligand with an average pore size of 450 Å for high-resolution separation of large proteins (> 150 kDa). The 2.7 µm solid-core particles are designed to minimize intraparticle diffusion distances and maximize the resolving power for protein samples.

RP-HPLC was used in process monitoring to separate the target ancestral spike antigen from HCP impurities in crude harvest and subsequent purification steps across process intermediates through to purified SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen material. SDS-PAGE analysis was initially used, but the complexity of the samples (Fig. 1) combined with lower throughput severely limited downstream process development and hindered key technical decisions required to achieve greater than 90% spike antigen purity. The chromatograms in Fig. 2 demonstrate the reliability of the RP-HPLC method with a consistent ancestral spike protein antigen peak eluting at 18.4 min regardless of the sample complexity or downstream chromatographic purification method. Most of the proteins begin eluting after four minutes with the most hydrophobic proteins eluting at the end of the gradient near the twenty-minute point. Improvements in purity through the downstream processing streams are readily observed using UV detection at 215 nm and comparing the peak, marked by an asterisk, in the crude fermenter supernatant (Fig. 2A) with the marked peak in the purified drug substance (Fig. 2D) representing > 90% pure SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen material. The BioResolve RP column maintains consistent performance and accurate retention time for the spike antigen candidate throughout the changes in sample matrix conditions across the process intermediate samples (Fig. 2A–C).

SDS-PAGE sample analysis to monitor progressive increase in antigen purity during downstream purification for the ancestral spike antigen production. Lane 1 molecular weight markers; Lane 2 crude fermenter supernatant; Lane 3 post-CaptoMMC chromatography; Lane 4 post-Hypercel chromatography Lane 5 Mustang Q; and Lane 6 TFF concentrated purified drug substance. Red overlay numbers indicate relative (%) of band intensity per lane from densitometry analysis.

Direct implementation of RP-HPLC method to monitor progressive increase in antigen purity during downstream purification. UV215nm chromatograms corresponding to (A) crude fermenter supernatant, (B) post-CaptoMMC chromatography, (C) post-Hypercel chromatography and (D) purified drug substance for ancestral spike antigen production. Asterisk (*) denotes peak containing spike protein antigen.

To demonstrate method specificity, peak purity and to better understand the capabilities of the RP-HPLC method; fractions were collected for all chromatographic features with > 1% peak area, in the purified antigen drug substance. Selected fractions were dried down in a Speed Vac then analysed using microCapillary Electrophoresis ImmunoAssay (mCE IA, Fig. 3) and LC/MS/MS analysis (Fig. 4). The RP-HPLC fractions were collected in duplicate with 10 µg column load for mCE IA and 3 µg column load for LC/MS/MS analysis. These orthogonal methods were used to identify both product-related (e.g. antigen truncates) and process-related host cell protein impurities (HCPs). While the LC/MS/MS method (Fig. 4A) provides high sensitivity and breadth of coverage for low level HCPs as well as spike antigen sequences, results could not distinguish full length protein from potential truncates due to the enzymatic digest step prior to LC/MS/MS analysis.

Simple Wes identification of spike antigen containing fractions from RP-HPLC separation. (A) Purified drug substance UV280 nm chromatogram with fraction collection marked with vertical lines and (B) Simple Wes detection using anti-RBD polyclonal antibody. Lane 1 molecular weight markers; Lane 2 purified spike antigen control; Lane 3 fraction 4; Lane 4 fraction 5; Lane 5 fraction 8; Lane 6 fraction 13; Lane 7 fraction 14; Lane 8 fraction 18; Lane 9 fraction 19; Lane 10 fraction 20; Lane 11 fraction 21; Lane 12 fraction 22; and Lane 13 cell lysate. Similar results were obtained using anti-S1 and anti-S2 polyclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen (data not shown).

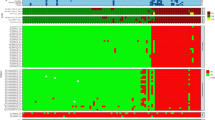

LC/MS/MS analysis for protein identification in RP-HPLC fractions: (A) LC/MS/MS workflow schematic including digestion of protein fractions, separation by nanoUPLC followed by data dependent acquisition on a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer. (B) UV280 nm chromatogram of purified drug substance with HPLC fractions collected by time in 30 s intervals. (C) A bar plot representation of the relative intensity of proteins detected in the fraction identification LC/MS/MS experiments. Insert, table summary of main protein identity results for HPLC fractions.

Rapid protein identification of the ancestral spike antigen from the RP-HPLC fractions was achieved by western blot analysis initially performed using standard SDS-PAGE separated samples and then transitioned to an automated mCE IA (Simple Wes)29. The Simple Wes method allowed for low-resolution measure of protein molecular weight, providing the ability to differentiate truncated from full-length protein both in a standalone manner as well as individual fractions collected by RP-HPLC monitored at UV absorbance 280 nm using antibody reagents recognizing the SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen receptor binding domain, S1 or S2 domains (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 1).

Positive ancestral spike antigen identity was confirmed for the main peak eluting at 18.4 min and the minor peaks eluting immediately before and after the main peak using an anti-RBD antibody (Fig. 3). The earlier eluting peaks, containing less hydrophobic molecules, consistent with either smaller proteins or fragments of larger proteins degraded during the purification process, were not identified by the Simple Wes analysis, consistent with the superior reported stability of the engineered spike antigen constructs30. To confirm spike antigen and impurity protein identity, HPLC fractions were subjected to proteolytic digestion followed by LC/MS/MS analysis of the resulting peptides (Fig. 4).

The LC/MS/MS fraction analysis identified the recombinant spike antigen as the most intense protein in the major peak (18.4 min) of the RP-HPLC chromatogram (Fig. 4B). This workflow also facilitated the identification of HCPs across the RP-HPLC fraction analysis, detected as minor constituents in the drug substance. The spike antigen was detected at lower intensities in some of the earlier eluting fractions (fraction 8, and as minor components in fractions 13 and 14, see Supplemental Fig. 2A) as well as in the later eluting fraction that was collected after the main peak (Fig. 4C). The spike antigen sequence was also detected in the low intensity peaks eluting between 12.0 and 12.5 min as measured by LC/MS/MS and confirmed by Simple Wes as a lower mass truncate containing the RBD sequence (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. 1).

Protein identification by LC/MS/MS analysis of individual RP-HPLC fractions was compared to in-solution LC/MS/MS analysis results for the matching drug substance lot (Supplemental Fig. 2). The most intense HCPs detected in RP-HPLC fractions (fraction 13 and 14 in Fig. 4C inset table) were also detected as the most intense HCPs from the in-solution digest workflow (Supplemental Fig. 2). The early eluting peak, observed at 10.5 min (Fig. 4B) was identified as Triton X-100 based on a separate LC–UV–MS analysis (Supplemental Fig. 3). Triton X-100 is a polymer surfactant used in the purification process which exhibits characteristically higher absorbance at UV280 nm compared to UV215 nm, in contrast to proteins which display higher relative signal at UV215 nm. The Triton X-100 peak at 10.5 min was shown not to contain protein components, as no protein was identified in the LC/MS/MS analysis (Fraction 4, Fig. 4B) corroborated by the absence of intrinsic fluorescence signal for the Triton X-100 peak. In addition, diagnostic molecular ions from the surfactant were observed in survey-based MS spectra from LC–UV–MS analysis (Supplemental Fig. 3). The Triton X-100 peak was subsequently excluded from calculations of protein purity.

As the pandemic progressed new globally circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOC) arose with varying amino acid substitutions and mutations placing pressure on vaccine development to consider formulating multiple spike antigens to support global public health. Three vaccine spike antigen variants, ancestral, Beta and Omicron BA.1, were evaluated using this recombinant spike antigen platform during the pandemic with two vaccine candidates completing Phase 3 clinical trials for primary and booster immunization22,25,31 (Fig. 5). The Beta spike antigen amino acid sequence diverged from the ancestral spike by eleven changes, while the later circulating Omicron BA.1 spike antigen differed by over 40 amino acid modifications. These amino acid additions, deletions, and substitutions (Fig. 5 and Table 1) impacted the biophysical properties of the spike antigen by influencing the relative hydrophobicity and isoelectric points of the full-length antigens (Table 1). The differences in pI and hydrophobicity between the three spike antigens were detected by RP-HPLC analysis. The retention times of the more similar ancestral and Beta spike antigens co-eluted at 18.4 min in contrast to the more charged Omicron BA.1 spike antigen which eluted earlier at 17.5 min as shown in Fig. 6. Although protein yields varied by spike antigen variant, the protein purity achieved for final drug substance was similar across all three spike antigens consistently observed between 90 and 95% (Fig. 6).

Schematic of SARS CoV-2 S-glycoproteins. Structure of native spike (1) from the ancestral Wuhan-Hu-1 isolate; (2) vaccine ancestral spike antigen, with amino acids and region modified in cyan; (3) vaccine Beta spike antigen with additional modifications in blue boxes: (4) vaccine Omicron BA.1 spike antigen with additional modification in blue boxes. The numbering of the deletions and point mutations is based on the Wuhan-Hu-1 full-length protein sequence. SS, signal sequence; NTD, amino terminal domain (14–305); RBD, receptor binding domain (331–527); SD1/SD2, C-terminal domains 1 and 2 (528–685); S1/S2 protease cleavage site (685); FP, fusion peptide(816–855); FPR, fusion peptide region (856–911); HR1, heptad repeat 1 (912–984); CH, central helix (985–1034); CD, connector domain (1076–1141); HR2, heptad repeat 2; TM, transmembrane domain; CT, cytoplasmic tail; T4f., T4 foldon trimerization domain.

RP-HPLC analysis of ancestral, Beta and Omicron BA.1 SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen constructs produced in baculovirus-vector expression system. Purified antigen material demonstrating high purity by RP-HPLC. Retention of main antigen peak was identical for ancestral and Beta spike antigens. Omicron BA.1 spike antigen exhibited distinctly earlier retention time by RP-HPLC, reflecting overall lower hydrophobicity arising from differences in amino acid composition.

Discussion

High-throughput protein characterization was essential to realize rapid downstream process optimization in the accelerated timelines needed for this pandemic COVID-19 vaccine development. Replacement of traditional SDS-PAGE analysis to determine protein purity by RP-HPLC provided higher resolution separation of protein impurities and sample compatibility for analysis between the different protein characterization methods which was crucial to achieve the high-throughput analysis in a timely manner. Samples eluted from the intermediate chromatographic purification steps, as well as the final vaccine drug substance and drug product, were loaded directly onto the BioResolve RP column without further sample preparation. Fractions were collected from RP-HPLC in a precise, timed manner by use of an automated fraction collector then dried down and resuspended in the appropriate sample buffer for Simple Wes and LC/MS/MS analysis. The simplified sample handling was key for rapid data generation leading to speedy process optimization decisions. Changes in buffer composition, pH and gradient elution for each chromatographic step in the downstream spike antigen purification process were realized by access to rapid data generated from experimental investigations at GMP scale (2000–10,000 L fermentation). Optimization of the downstream process with high purity was essential to gain regulatory approval to proceed to Phase 2 clinical trials. Ultimately, with validated analytical methods in place, vaccine development proceeded to a Phase 3 clinical trial start nine days after the Phase 2 dose ranging results were announced.

The RP-HPLC assay also facilitated high-throughput analysis for vaccine purity and characterization in support of Market Authorization. This was particularly important to demonstrate robust CMC and GMP manufacture of new VOC based vaccines32,33. The molecular identity of spike antigen confirmed by Simple Wes analysis was followed by LC/MS/MS impurity analysis providing clear identification of spike antigen and related truncation species as well as trace detection of HCPs. This tandem identity profiling provided clear and convincing support for the > 95% product purity attained for VidPrevtyn Beta commercial supply. This was important not only as release criteria, but also for stability testing on the drug substance, and diluted drug product, necessary to generate positive data for shelf-life determination.

The first emerging VOCs had minimal amino acid substitutions in the spike antigen. However, as SARS-CoV-2 evolved the number of amino acid mutations across the entire viral genome subsequently increased, thus allowing a more infectious, but less lethal pathogen. The eleven amino acid substitutions/deletions between the ancestral and Beta spike antigens were strategically located in surface accessible domains to evade the elicited immune response. However, because the biochemical properties of the substituted amino acids were similar, these changes did not influence the RP-HPLC retention profile. By the time the Omicron VOCs had emerged, the number of mutations had significantly increased with 41 substitutions/deletions/additions in the spike antigen alone. These changes impacted not only the precise and specific immunological recognition of the spike antigen but also influenced the isoelectric point and surface microenvironment of the Omicron BA.1 spike antigen to affect RP-HPLC retention sufficiently to achieve baseline separation when compared to ancestral and Beta spike antigen. Orthogonal protein characterization comparison of different variant antigens was essential to differentiate the earlier more similar VOCs, but as the SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen changed in later emerging VOCs, the RP-HPLC profiles alone could be used to recognize the different antigens based on differences in established elution patterns.

Determination of antigen purity presents considerable challenges from both analytical and regulatory CMC perspectives. Current WHO guidelines recognize HPLC as a suitable antigen purity method for multiple recombinant vaccines (Hepatitis B, Malaria, and Hepatitis E)3,34,35; however, no such document guidance exists at the time of writing for SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccines. Utilization of RP-HPLC for purity release in combination with LC/MS/MS and Simple Wes for orthogonal peak identity characterization, reflects use of cutting-edge analytical technologies which are broadly applicable across recombinant protein vaccine development. This advanced and integrated analysis can serve as a template for other recombinant vaccine antigens wherein protein purity remains a critical quality parameter.

Overall, we found RP-HPLC separations of process intermediate and purified antigen samples to be critical for the rapid downstream process development of multiple recombinant COVID-19 vaccine formulations. Ease of fractionation coupled with Simple Wes and LC/MS/MS were applied as complementary workflows to provide in-depth and robust characterization. The RP-HPLC method was validated to replace the traditional SDS-PAGE for internal analytical process development and was accepted in regulatory filings to support Market Authorization of VidPrevtyn Beta as a COVID-19 booster vaccine. Simple Wes analysis provided spike antigen identification of fractions collected from RP-HPLC in a rapid, automated manner for large numbers of samples collected from multiple RP-HPLC runs. The impurity profile was completed by LC/MS/MS identification of all protein-containing fractions from the RP-HPLC analysis. Future recombinant protein vaccine development will require orthogonal analytical techniques as the standard for full protein characterization. Ongoing innovation in analytical technologies will continue to drive improvements towards more rapid and sensitive analyses.

Methods

Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

Reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was performed on an Agilent 1260 HPLC equipped with quaternary pump, diode array (DAD) and fluorescence detection. SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen was separated from protein impurities using a Waters BioResolve RP mAb 450, 2.7 µM, 2.1 × 150 mm column held at 65 °C with 0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (ACN) (mobile phase B). A non-linear gradient was applied at 0.4 mL/min as follows: 10–20% B (0–2 min); 20–50% B (2–12 min); 50–68% B (12–24 min); 80% B (25–28 min); 10% B (28.01–33 min). This multi-step gradient provided a rapid cycle time without sacrificing high sensitivity or resolution for protein fragments/impurities (i.e. 3%/min gradient slope) and full-length antigen (i.e. 1.5%/min gradient slope). Ultraviolet (UV) detection was performed at 215 nm for in-process samples and 280 nm for purified antigen material (DAD bandwidth = 4 nm, reference 360 nm). Intrinsic protein fluorescence was captured concurrently during the RP-HPLC separation via excitation at 280 nm and monitoring tryptophan emission at 340 nm36. Data analysis was carried out in Empower software (Waters) and purity reported from % area of the main antigen peak.

The total protein concentration between stages was ≥ 100 μg/mL based on bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. The BCA total protein results were used to normalize protein load at 3 µg on-column to maintain consistent sensitivity for impurity detection. Samples were held in an autosampler set to 10 °C and directly injected without any treatment prior to RP-HPLC analysis. Fractions were collected using an online fraction collector in 30-s time windows then dried down in a Speed Vac for analysis by Protein Simple Wes or LC/MS/MS. The Triton X-100 peak (~ 10.5 min) was identified by running RP-HPLC on an Agilent Q-TOF 6500 series mass spectrometer operated in positive ion mode.

Simple western microcapillary immunoassay

Western blotting was performed by way of an automated microCapillary Electrophoresis ImmunoAssay (mCE IA) as previously described29. mCE IA reagents were provided by ProteinSimple©(Bio-Techne) and used in conjunction with ProteinSimple’s Simple Western Instrument and 12–230 kDa Wes Separation Module (cat# SM-W004). Reagents were prepared according to the ProteinSimple© Simple Wes manual. Recombinantly expressed SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen samples were diluted using 0.1 × sample buffer (Cat # 042-195) and 4 mL of 5 × Fluorescent master mix with 200 mM DTT in a final volume of 20 mL. Samples were incubated for 5 min at 95 °C and then transferred to the 12- 230 kDa pre-filled microplate (cat # 043-165). A standard curve was prepared from 0.025 to 0.25 µg/mL using purified drug substance material. A commercial full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was obtained from Acro Biosystems (Cat # S2N-C52H5) and included for comparison.

Automated mCEIA analysis was performed using polyclonal primary antibody recognizing the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Sino Biological cat # 40592-T62) diluted 200 × with antibody diluent (cat# 042–203). Additional qualitative characterization of fractions was performed using anti-S1 (Thermo Scientific cat # PA1-41375) and anti-S2 polyclonal primary antibodies (Thermo Scientific cat # PA1-41,165). The polyclonal antibodies were verified to be highly specific for SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen with no cross reactivity against a Sf9 lysate negative control. Undiluted HRP conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat# 042–206) and freshly prepared 1:1 solution of Luminol-S (cat# 043–311) and peroxide (cat# 043–379) were loaded into the pre-filled microplate to facilitate immunochemical detection.

Separation, incubation, and blocking were performed automatically using the Protein Simple 12–230 kDa module program in the Compass software accompanied by the ProteinSimple’s Simple Western Instrument. Capillary gel images and electropherograms were automatically generated by Compass Software. Fractions were visualized in a gel image view to probe for the presence or absence of a band at the anticipated molecular weight for spike antigen.

SDS-PAGE

Samples for SDS-PAGE densitometry analysis were prepared using an in-house master buffer comprised of 40 µL β-mercaptoethanol and 360 µL of 4 × SDS stock solution (0.25 M Tris–HCl, 20% glycerol, 8% (w/v) SDS, 8 M urea pH 6.8). Process intermediates were prepared by adding 20 µL of sample to 8 µL of master buffer, heat treatment at 95 °C for 5 min followed by a ~ 10 s sedimentation step to collect condensation prior to gel loading. The molecular weight marker was prepared similarly with 8 µL of Precision Plus Protein standard (BioRad cat # 1610374) combined with 8 µL of master buffer covering a molecular weight (MW) size range of 10–250 kDa. For purified drug substance samples, the volume of sample was adjusted and diluted with Milli-Q water to target ~ 3 µg total per lane.

Gel electrophoresis was performed using a pre-cast NuPAGE 4–12% Bis–Tris gel (Life Technologies Cat # NP0321BOX) in a XCell SureLock Mini-Cell system (Life Technologies Cat # EI0001). Separation was performed with 1xMOPS SDS running buffer at 200 V for 40 min following manufacturer instructions. The gel was stained using Instant Blue (AbCam Cat # ab119211) for > 1 h then destained in water for > 2 h. Densitometry analysis was performed on a Bio-Rad GS-900 calibrated densitometer with Image Lab software. The progressive increase in purity during downstream purification was monitored using the relative (%) band intensity per lane from the densitometry analysis.

LC/MS/MS analysis

HPLC fraction digestion: The RP-HPLC fractions were dried down using a SpeedVac and resuspended in a mixture of 25 μL of the one-pot reduction/alkylation buffer that consisted of 3 μL of 1 M ammonium bicarbonate (ABC, Sigma Cat# 09830), 3 μL of 1% RapiGest (Waters, Cat# 186001861), 0.3 μL of 0.5 M TCEP (Thermo, Cat# A39270), 3 μL of 200 mM chloroacetamide (CAA, Thermo Cat# 77720) and 15.7 μL of LC/MS water (Fisher). The mixture was then incubated at 95 °C at 300 rpm for 10 min. Then, 10 μL of 0.1 μg/μL Trypsin/LysC (Promega, Cat# V5072) was added to each fraction and incubated at 37 °C at 300 rpm for 1 h. Digestions were quenched with 1 μL of a solution of 50/50 trifluoroacetic acid and incubated at 37 °C at 300 rpm for 30 min to hydrolyze the RapiGest. Samples were sedimented at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant collected. The fraction digests were either frozen at − 20 °C or aliquoted into sample vials for LC/MS analysis.

Solution digestion: 25 μg of protein sample was diluted in water to a total volume of 98.5 μL. 15 μL of 1 M ammonium bicarbonate (ABC, Sigma Cat# 09830), 15 μL of 1% RapiGest (Waters, Cat# 186001861), 1.5 μL of 0.5 M TCEP (Thermo, Cat# A39270), and 15 μL of 200 mM chloroacetamide (CAA, Thermo Cat# 77720) were added to each sample for one-pot reduction and alkylation. The mixture was then incubated at 95 °C at 300 rpm for 10 min, and cooled to room temperature for 5 min. 5 μL of 0.5 μg/μL of Trypsin/LysC (Promega, Cat# V5072) was added to the sample mixtures and incubated at 37 °C at 300 rpm for 2 h. Digestions were quenched with 6 μL of a solution of 50/50 formic acid and incubated at 37 °C at 300 rpm for 30 min to hydrolyze the RapiGest. Samples were sedimented at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected. The digested samples were either stored at − 20 °C or diluted with 0.1% FA in water to 500 fmol/μL (based on the antigen concentration in sample) and transferred into sample vials for LC–MS analysis.

Mass Spectrometry data acquisition: LC/MS/MS experiments were run on a Thermo Scientific™ Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer coupled to a Dionex UltiMate™ 3000 RSLCnano liquid chromatography system. The protein digest fractions were separated using an EASY-Spray™ (150 mm × 3 µm 75 µm) column. The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase B) using the following gradient: 1% B (0–4 min); 1–35% B (1–99 min); 35–95% B (99–101 min); 95% B (101–106 min); 95–1% B (106–107 min); 1% B (107–117 min). The flow rate was 0.3 µL/min, and 10 μL of the sample, stored at 6 °C in the autosampler, was injected. The column was heated to 35 °C. All the MS data acquisition runs were acquired using data dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. The mass spectrometer collected data from 10 to 115 min in positive mode. The MS survey scan range was set to 400–2000 Da at 120,000 resolution and AGC target and maximum IT of 3e6 and 200 ms, respectively. MS/MS spectra were collected for the top-10 MS1 ions at 30,000 resolution and normalized collision energy of 27. AGC target was set to 5e5 and maximum IT was 100 ms.

Data Analysis: Data Processing for DDA Protein Identification NanoLC/MS/MS results files were imported into Proteome Discoverer version 2.4 (Thermo Scientific) for data processing. Databases containing the following protein sequences were used for all analyses: Cell expression system: Spodoptera frugiperda proteome (UniProt UP000102185, 28 122 sequences), Baculovirus: Autographa californica proteome (UniProt UP000008292, 155 sequences), Antigen: SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike antigen sequence (each variant sequence, respectively), Common impurities (proteins that can be introduced to the sample during sample handling and preparation/proteolysis, or that are used as standards in MS analysis, 118 sequences)37. Experiments were searched using the Sequest HT algorithm with trypsin as the enzyme. A maximum of 4 missed cleavages were considered with the following dynamic modifications: carbamidomethyl (C), deamidation (NQ), oxidation (M) and carbamylation (K). Precursor mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm and the fragment mass tolerance to 0.02 Da. Results were filtered based on a target decoy search with a false discovery rate of 1% at the peptide-spectral match (PSM) level. For LC/MS/MS based protein detection/identification, the following criteria were applied for protein assignment: (i) a minimum of 3 peptides detected per assigned protein and (ii) confidence threshold of 99% for all assigned proteins reported in results. Target False Discovery Rate (FDR) was set at 0.01 in search parameters.

Data availability

The data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and the supplementary information file. Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Black, S., Bloom, D. E., Kaslow, D. C., Pecetta, S. & Rappuoli, R. Transforming vaccine development. Semin. Immunol. 50, 101413 (2020).

FDA. Guidance for Industry General Principles for the Development of Vaccines to Protect Against Global Infectious Disease. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/general-principles-development-vaccines-protect-against-global-infectious-diseases (2011).

WHO. Guidelines on the quality, safety and efficacy of recombinant malaria vaccines targeting the pre-erythrocytic and blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum, Annex 3, TRS No 980. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/content-and-format-chemistry-manufacturing-and-controls-information-and-establishment-description-1 (2014).

WHO. WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/208900/9789240695634-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2015).

Slaoui, M. & Hepburn, M. Developing safe and effective covid vaccines—Operation warp speed’s strategy and approach. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1701–1703 (2020).

Bok, K., Sitar, S., Graham, B. S. & Mascola, J. R. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: Milestones, lessons, and prospects. Immunity 54, 1636–1651 (2021).

Kim, J. H. et al. Operation warp speed: Implications for global vaccine security. Lancet Glob. Health 9(7), e1017–e1021 (2021).

Saville, M. et al. Delivering pandemic vaccines in 100 Days—What will it take?. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, e3 (2022).

WHO. Considerations for evaluation of COVID19 vaccines. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/in-vitro-diagnostics/covid19/considerations-who-evaluation-of-covid-vaccine_v25_11_2020.pdf?sfvrsn=f14bc2b1_3&download=true (2020).

FDA. Emergency Use Authorization Vaccines Prevent COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/public-health-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19 (2022).

EMA. EMA considerations on Covid-19 vaccine approval. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/ema-considerations-covid-19-vaccine-approval_en.pdf (2020).

WHO. EUL Procedure v9. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/medicines/eulprocedure.pdf?sfvrsn=55fe3ab8_8&download=true (2022).

Chu, L. et al. A preliminary report of a randomized controlled phase 2 trial of the safety and immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Vaccine 39, 2791–2799 (2021).

Mulligan, M. J. et al. Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults. Nature 586, 589–593 (2020).

Shinde, V. et al. Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1899–1909 (2021).

Sadoff, J. et al. Interim results of a phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1824–1835 (2021).

Sridhar, S. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an AS03-adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine (CoV2 preS dTM) in healthy adults: Interim findings from a phase 2, randomised, dose-finding, multicentre study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 636–648 (2022).

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403–416 (2020).

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603–2615 (2020).

Heath, P. T. et al. Safety and efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1172–1183 (2021).

Sadoff, J. et al. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2187–2201 (2021).

Dayan, G. H. et al. Efficacy of a monovalent (D614) SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine with AS03 adjuvant in adults: A phase 3, multi-country study. eClinicalMedicine 64, 102168 (2023).

Goepfert, P. A. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine formulations in healthy adults: Interim results of a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 1–2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 1257–1270 (2021).

Anosova, N. et al., 2022. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infections. PCT/US2021/047152, filed August 21, 2021.

Dayan, G. H. et al. Efficacy of a bivalent (D614 + B.1.351) SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine with AS03 adjuvant in adults: A phase 3, parallel, randomised, modified double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 11, 975–990 (2023).

Sanofi and GSK COVID-19 vaccine candidate demonstrates strong immune responses across all adult age groups in Phase 2 trial. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2021/2021-05-17-05-30-00-2230312.

Sanofi and GSK initiate global Phase 3 clinical efficacy study of COVID-19 vaccine candidate. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2021/2021-05-27-05-30-00-2236989.

Fekete, S., Veuthey, J.-L. & Guillarme, D. New trends in reversed-phase liquid chromatographic separations of therapeutic peptides and proteins: Theory and applications. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 69, 9–27 (2012).

Keizner, D. et al. Quantitative microcapillary electrophoresis immunoassay (mCE IA) for end-to-end analysis of pertactin within in-process samples and Quadracel® vaccine. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 204, 114284 (2021).

Bruch, E. M. et al. Structural and biochemical rationale for Beta variant protein booster vaccine broad cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 14, 2038 (2024).

de Bruyn, G. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a variant-adapted SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine with AS03 adjuvant as a booster in adults primed with authorized vaccines: A phase 3, parallel-group study. eClinicalMedicine 62, 102109 (2023).

EMA. EMA recommends approval of VidPrevtyn Beta as a COVID 19 booster vaccine | European Medicines Agency (EMA). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-approval-vidprevtyn-beta-covid-19-booster-vaccine?ref=publicsquare.uk (2022).

EMA. VidPrevtyn Beta, INN-COVID-19-Vaccine-(recombinant,-adjuvanted). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/vidprevtyn-beta-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (2022).

WHO. Recommendations to assure the quality, safety and efficacy of recombinant hepatitis B vaccines. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/biologicals/vaccine-standardization/hepatitis-b/trs-978-annex-4.pdf?sfvrsn=12032a5b_4&download=true (2013).

WHO. Recommendations to assure the quality, safety and efficacy of recombinant hepatitis E vaccines. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/biologicals/vaccine-standardization/hepatitis-e/trs_1016_hep_e_annex_2_web-2.pdf?sfvrsn=78c0a7bc_3&download=true (2019).

Stone, K. L. et al. Techniques in Protein Chemistry. In Sect. IV: Appl. HPLC, 377–391 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-682001-0.50046-4.

The Global Proteome Machine-cRAP protein sequences. https://thegpm.org/crap/index.html.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Cindy Xin Li for in-process samples and SDS-PAGE analysis, Shaolong Zhu for intact mass LC-MS analysis for Triton peak ID, Allison Kennedy for assistance with Simple Wes figure generation, Rahul Misra for in-process sample coordination, Kartik Narayan and Matthew Balmer for supervisory oversight and initial discussions on conceptual design. This study was funded by Sanofi and by federal funds from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, part of the office of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response at the US Department of Health and Human Services in collaboration with the US Department of Defense Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Defense under contract number W15QKN-16-9-1002. The views presented here are those of the authors and do not purport to represent those of the Department of the Army.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A.J. and R.M.C. contributed to the concept and/or design of the study. L.S. developed the RP-HPLC method, carried out sample separations and data generation. H.S carried out the Simple Wes experiments and data analysis. L.S. and M.L. interpreted the RP-HPLC and Simple Wes results. L.Y. performed the LC/MS/MS experiments. L.Y., L.S., and D.A.J carried out the LC/MS/MS data analysis and interpretation. D.A.J and R.M.C wrote the first draft of the manuscript. R.M.C., D.A.J. and L.S. contributed to manuscript preparation, review, and editing. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are current or former employees of Sanofi and may hold shares and stock options in the company.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

James, D.A., Szymkowicz, L., Yin, L. et al. Accelerated vaccine process development by orthogonal protein characterization. Sci Rep 15, 11831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96642-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96642-y