Abstract

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is characterized by the abnormal growth of ectopic bone in non-skeletal soft tissues through a fibrotic pathway and is a frequent complication in a wide variety of musculoskeletal injuries. We have previously demonstrated that TGFβ levels are elevated in the soft tissues following extremity injuries. Since TGFβ mediates the initial inflammatory and wound-healing response in the traumatized muscle bed, we hypothesized that targeted inhibition of the TGFβ pathway may be able to abrogate the unbalanced fibrotic phenotype and bone-forming response observed in post-traumatic HO. Primary mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) harvested from debrided traumatized human muscle tissue were used in this study. After treatment with TGFβ inhibitors (SB431542, Galunisertib/LY2157299, Halofuginone, and SIS3) cell proliferation/survival, fibrotic formation, osteogenic induction, gene expression, and phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 were assessed. In vivo studies were performed with a Sprague-Dawley rat blast model treated with the TGFβ inhibitors. The treatment effects on the rat tissues were investigated by radiographs, histology, and gene expression analyses. Primary MPCs treated with TGFβ had a significant increase in the number of fibrotic nodules compared to the control, while TGFβ inhibitors that directly block the TGFβ extracellular receptor had the greatest effect on reducing the number of fibrotic nodules and significantly reducing the expression of fibrotic genes. In vivo studies demonstrated a trend towards a lower extent of HO formation by radiographic analysis up to 4 months after injury when animals were treated with the TGFβ inhibitors SB431542, Halofuginone and SIS3. Altogether, our results suggest that targeted inhibition of the TGFβ pathway may be a useful therapeutic strategy for post-traumatic HO patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is characterized by the abnormal growth of ectopic bone in non-skeletal soft tissues and afflicts up to 70% of patients after hip replacements, musculoskeletal trauma, amputations or burn injuries1,2. Patients with HO experience multiple complications, such as chronic pain, restricted joint function, and open wounds that impair rehabilitation and prosthetic limb use1. Current treatment strategies are limited to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, radiation therapy, and surgical excision, but they fail to reverse the joint contractures and the restricted range of motion as well as to prevent the development and the recurrence of ectopic bone formation.

While modulation of the local inflammatory response following injury is essential for wound healing and repair, severe traumatic injuries appear to initiate an over-exuberant response that compromises efficient wound healing and tissue regeneration. As a result of the chronic inflammation in the wound, tissue regeneration mechanisms are overshadowed by a generalized healing response that leads to the formation of scar tissue1. Of importance, nonmyogenic mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) in skeletal muscle were shown to be the origin of adipogenic and fibrous connective (scar) tissue as well as the major contributor to the formation of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-induced HO3,4,5. Nonmyogenic MPCs exhibit osteogenic and adipogenic potential and share the cell surface markers CD31-, CD45-, Sca-1+, and PDGFRα+5. Also, they are a distinct cell population from satellite cell-derived myoblasts, which have been reported to contribute to myofiber formation, but not to fibrotic tissue formation5. As such, fibrotic tissue formation is likely an intermediate step in the onset of post-traumatic HO in a way that is not completely understood. Overall, we believe that to identify novel and efficient treatment strategies that can block post-traumatic HO and promote normal tissue regeneration it is essential to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying fibrotic tissue and HO formation after injury.

TGFβ plays a critical role in tissue fibrosis and TGFβ signaling is crucial for wound healing biology and stem cell commitment, processes that are activated after musculoskeletal injury6,7. TGFβ1-mediated tissue fibrosis is mainly triggered by the activation of the downstream small mother against decapentaplegic (SMAD) signaling, which regulates the over-expression of pro-fibrotic genes8. However, non-SMAD pathways and a wide range of cell types besides fibroblasts (including macrophages, epithelial cells, and vascular cells) also play a role in post-traumatic TGFβ-mediated fibrosis9. In addition, we have found that TGFβ1 is highly expressed in human muscle tissue samples after injury6, and platelets that are immediately recruited after injury (i) contain large amounts of TGFβ1 and (ii) release TGFβ1 at the site of injury, promoting the recruitment of monocytes and fibroblasts to the site of injury and, overall, accelerating the process of wound healing10. Also of interest, it has been shown that TGFβ initiates and promotes HO formation in mouse models as well as treatment with TGFβ neutralizing antibody attenuates ectopic bone formation while an inducible knockout of the TGFβ type II receptor inhibits HO progression in vivo11.

More recently, it has been demonstrated that TGFβ1-activated SMAD2 and SMAD3 signaling have differential genomic responses and play distinct, but complementary, roles in regulating early developmental events in mammals12,13. It has also been shown that in the presence of TGFβ1, secretion of matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2) is dependent on SMAD2, secretion of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) protein is dependent on SMAD3 and upregulation of alpha 2 actin smooth muscle (ACTA2) is dependent on both SMAD2 and SMAD3, suggesting distinct functional roles for these proteins14. Altogether, these results demonstrate that SMAD2 and SMAD3 can differentially regulate the transcription of fibrotic-associated TGFβ target genes.

Since TGFβ is a critical mediator of the initial inflammatory and wound healing response in the traumatized muscle bed, we hypothesized that targeted inhibition of the TGFβ pathway may be able to abrogate the unbalanced fibrotic phenotype and bone-forming response observed in the development and progression of post-traumatic HO. In this study, we report the in vitro and in vivo effects of two classes of TGFβ inhibitors that (i) target the TGFβ receptor inhibiting both SMAD2 and SMAD3 phosphorylation (ALK5/TGFβ type I receptor inhibitors: SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299) or that (ii) specifically target and inhibit SMAD3 phosphorylation (SMAD3 inhibitors: Halofuginone and SIS3) in the formation of fibrotic nodules and post-traumatic HO. Overall, our study provides additional preclinical evidence that supports targeted and selective inhibition of the TGFβ pathway as a useful therapeutic strategy for post-traumatic HO patients.

Results

TGFβ inhibitors selectively regulate SMAD2/3 phosphorylation while having minor effects on the proliferation and survival of human primary MPCs

We and others have previously demonstrated that TGFβ levels are elevated in humans after injury and during the development of HO6,7,11. To investigate the inhibition of the TGFβ pathway as a potential treatment for post-traumatic HO patients, we selected 2 classes of TGFβ inhibitors: ALK5/TGFβ type I receptor selective inhibitors (SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 selective inhibitors (Halofuginone and SIS3). The TGFβ inhibitors used in this study were commercially available from MedChem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ). To characterize the effects of these selected TGFβ targeted inhibitors we established an in vitro model of HO formation that consists of primary MPCs harvested from traumatized human muscle tissue treated with recombinant TGFβ [10 ng/mL]. MPCs were treated with SB431542 [0.3 µM, 1 µM and 3 µM] or Galunisertib (LY2157299) [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM] simultaneously with TGFβ for 30 min (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1), and Halofuginone [3 nM, 10 nM and 30 nM] or SIS3 [5 µM, 10 µM and 20 µM] for 24 h followed by TGFβ treatment for 30 min and 15 min, respectively (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1, treatment with SB431542 decreased in a dose-dependent manner the levels of both pSMAD2 and pSMAD3 compared to the TGFβ treatment alone, and treatment with Galunisertib (LY2157299) demonstrated similar effects decreasing pSMAD2 levels, while a decrease in pSMAD3 levels compared to the TGFβ treatment alone was observed only in one donor (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1, Donor 2). Also, the SMAD3 inhibitors Halofuginone and SIS3 had no major effects on pSMAD2 levels, while a dose-dependent downregulation of pSMAD3 compared to the TGFβ treatment alone was consistently observed (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. 1). Of note, the total levels of SMAD2 were not significantly affected, while the total levels of SMAD3 were in some cases also modulated by the inhibitors (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1).

TGFβ inhibitors selectively regulate SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in human primary MPCs. (A) Primary MPCs were treated with ALK5 inhibitors SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299 [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM]. SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299 treatments were performed simultaneously with the TGFβ [10 ng/mL] treatment for 30 min. (B) Primary MPCs were treated with SMAD3 inhibitors Halofuginone [3 nM, 10 nM, and 30 nM] or SIS3 [5 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM]. Halofuginone treatment was performed for 24 h before TGFβ [10 ng/mL] treatment for 30 min and SIS3 treatment was performed for 24 h before TGFβ [10 ng/mL] treatment for 15 min. GAPDH was used as the loading control. DMSO treatment was used as vehicle control. Molecular weight is shown in Kilodaltons (kDa). TGFB = TGFβ, SB = SB431542, LY = Galunisertib/LY2157299, Halo = Halofuginone.

In addition, to investigate the potential cytotoxic effects of the TGFβ inhibitors on MPCs, we treated these cells with each TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542 or Galunisertib/ LY2157299 [0.1 µM, 0.3 µM, 1 µM and 3 µM], Halofuginone [1 nM, 3 nM, 10 nM and 30 nM] or SIS3 [1 µM, 3 µM, 10 µM and 20 µM]) in the presence of TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for 4 days and 1 week. We chose to show the MTT results on the combination treatment of the inhibitors in the presence of TGFβ1 because these were the conditions used throughout the manuscript. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 2 and Table 1, both ALK5 and SMAD3 inhibitors demonstrated variable effects in the proliferation and survival of MPCs compared to the Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle) control. Moreover, TGFβ1 control treatment alone showed a 17–19% reduction in cell proliferation and survival of the MPCs compared to the DMSO (vehicle) control (4 days: Non-treated control: 100 ± 0.0; TGFβ1 control: 81 ± 17.0; p = 0.09; 1 week: Non-treated control: 100 ± 0.0; TGFβ1 control: 83 ± 17.0, p = 0.09; see Table 1), suggesting that to a certain extent TGFβ1 inhibits the proliferation of human primary MPCs. Of note, no significant differences were observed between a non-treated control condition and the DMSO control in both timepoints investigated (4 days: Non-treated control: 100 ± 0.0; DMSO control: 106 ± 3.6; p = 0.12; 1 week: Non-treated control: 100 ± 0.0; DMSO control: 100 ± 5.0; p = 1.00), demonstrating that no independent effects related to the DMSO treatment were observed. Altogether, these results demonstrate the specific effects of ALK5 (SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 (Halofuginone and SIS3) inhibitors in the levels of pSMAD2 and pSMAD3 and the variable effects of TGFβ1 and both classes of inhibitors in the proliferation and survival of human primary MPCs.

TGFβ inhibitors mostly downregulate the expression of fibrotic markers in human primary MPCs

We have previously demonstrated the elevated expression of fibrotic markers such as TGFβ1, SMAD3, Fibronectin, and PAI-1 in human-injured muscle samples15. As a result, we next investigated the effects of the TGFβ inhibitors (SB431542 [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Halofuginone [3 nM, 10 nM, and 30 nM] and SIS3 [3 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM]) on the expression of fibrotic markers (ACTA2, COL1A1, FN1, and SERPINE1) in MPCs cultured for 48 h with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] with or without each inhibitor in monolayer culture conditions. MPCs treated with TGFβ alone had increased levels of the fibrotic markers ACTA2 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 9.5 ± 3.3, p = 0.09), COL1A1 (Control: 1.1 ± 0.1; TGFβ: 4.8 ± 2.4, p = 0.09), FN1 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 4.1 ± 1.1, p = 0.09) and SERPINE1 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 5.6 ± 1.4, p = 0.09) compared to the vehicle (DMSO) control (Fig. 2). In addition, as shown in Fig. 2; Table 2, SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299 in combination with TGFβ consistently downregulated all the analyzed fibrotic markers. Interestingly, Halofuginone downregulated ACTA2, COL1A1, and FN1 only at the higher tested concentration of 30 nM, while only a mild effect was observed in SERPINE1 at the concentrations 3 nM and 10 nM (Fig. 2; Table 2). Finally, SIS3 demonstrated a robust downregulation of ACTA2 and COL1A1 at the concentrations 10 µM and 20 µM, while a more moderate downregulation of FN1 was observed at the 20 µM concentration, and only minor effects on the expression of SERPINE1 were observed (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Targeted TGFβ inhibitors down-regulate the expression of fibrotic markers in human primary MPCs. Primary MPCs were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for 48 h. Relative expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR for the fibrotic markers (A) ACTA2, (B) COL1A1, (C) FN1, and (D) SERPINE1. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control gene. DMSO treatment was used as vehicle control and used as a reference to calculate relative gene expression levels. Average ± SD from three to four independent donors. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 1-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with TGFβ treatment alone. TGFB = TGFβ, SB = SB431542, LY = Galunisertib/LY2157299 and Halo = Halofuginone.

Following these findings, we investigated the expression of the osteogenic regulator RUNX2 in MPCs cultured for 48 h and 1 week with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] with or without each TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542 [0.3 µM and 1 µM], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [0.3 µM and 1 µM], Halofuginone [3 nM and 10 nM] and SIS3 [3 µM and 10 µM]) in monolayer culture conditions. We chose to use only two representative doses from each inhibitor for this experiment to simplify the experimental design and interpretation of the results. Treatment of MPCs with TGFβ alone showed increased expression of the osteogenesis regulator RUNX2 compared to the vehicle (DMSO) control (Fig. 3; Control: 1.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 1.9 ± 0.2; p = 0.01). After 48 h of treatment, significant downregulation of RUNX2 was observed only with Galunisertib/LY2157299 [1 µM] treatment, while upon Halofuginone and SIS3 treatments the expression of RUNX2 remained mostly unchanged (Fig. 3A; Table 3). Interestingly, after 1 week of treatment, RUNX2 levels were constant or increased upon SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299 treatments, and moderately decreased upon Halofuginone and SIS3 treatments, respectively (Fig. 3B; Table 3).

Targeted TGFβ inhibitors selectively regulate the expression of RUNX2 in human primary MPCs. Primary MPCs were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for (A) 2 days and (B) 1 week. Relative expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control gene. DMSO treatment was used as a vehicle control and used as a reference to calculate relative gene expression levels. Average ± SD from three to four independent donors. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 1-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with TGFβ treatment alone (**p ≤ 0.01). TGFB = TGFβ, SB = SB431542, LY = Galunisertib/LY2157299 and Halo = Halofuginone.

For comparison, we performed downregulation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 with siRNAs with or without TGFβ [10 ng/mL] in MPCs cultured for 48 h in monolayer conditions. SMAD2 and SMAD3 knockdowns (SMAD2-KD and SMAD3-KD) were confirmed by q-RT-PCR (SMAD2-KD: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD: 0.3 ± 0.0, p = 0.00001; Control + TGFβ: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD + TGFβ: 0.3 ± 0.0, p = 0.000004 and SMAD3-KD: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.3 ± 0.0, p = 0.00001; Control + TGFβ: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD + TGFβ: 0.3 ± 0.0, p = 0.0002) and Western blot analyses (Supplemental Fig. 3A-D). Remarkably, in the absence of TGFβ treatment a significant downregulation of ACTA2 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD: 0.7 ± 0.1, p = 0.03), COL1A1 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD: 0.6 ± 0.2, p = 0.03), COL3A1 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD: 0.4 ± 0.1, p = 0.01), MMP9 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD: 0.7 ± 0.1, p = 0.01) and CDH2 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD: 0.8 ± 0.1, p = 0.03) was observed upon SMAD2-KD and downregulation of ACTA2 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.8 ± 0.1, p = 0.03), COL1A1 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.6 ± 0.2, p = 0.03), COL3A1 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.4 ± 0.1, p = 0.00), VIM (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.9 ± 0.1, p = 0.04), MMP9 (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.8 ± 0.1, p = 0.02) and ALP (Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, SMAD3-KD: 0.8 ± 0.1, p = 0.03) was observed upon SMAD3-KD (Supplemental Fig. 3E-F).

In the presence of TGFβ [10 ng/mL] treatment, downregulation of COL1A1, COL3A1, VIM, FN1 and ALP was observed for both SMAD2-KD (COL1A1: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 3.6 ± 0.9, SMAD2-KD: 2.8 ± 1.3, p = 0.03; COL3A1: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 1.8 ± 0.5, SMAD2-KD: 0.9 ± 0.3, p = 0.04; VIM: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 0.9 ± 0.1, SMAD2-KD: 0.7 ± 0.1, p = 0.04; FN1: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 2.1 ± 0.3, SMAD2-KD: 1.7 ± 0.4, p = 0.02 and ALP: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 1.6 ± 1.0, SMAD2-KD: 1.3 ± 1.1, p = 0.03) and SMAD3-KD (COL1A1: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 3.6 ± 0.9, SMAD3-KD: 2.9 ± 1.3, p = 0.04; COL3A1: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 1.8 ± 0.5, SMAD3-KD: 0.9 ± 0.3, p = 0.03; VIM: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 0.9 ± 0.1, SMAD3-KD: 0.6 ± 0.1, p = 0.03; FN1: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 2.1 ± 0.3, SMAD3-KD: 1.8 ± 0.5, p = 0.05 and ALP: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 1.6 ± 1.0, SMAD3-KD: 1.3 ± 1.2, p = 0.05) compared to the TGFβ treated control, while downregulation of BGLAP (also known as Osteocalcin) was observed only upon SMAD2-KD (BGLAP: Control: 1.0 ± 0.0, Control + TGFβ: 0.7 ± 0.0, SMAD2-KD + TGFβ: 0.6 ± 0.1, p = 0.04; Supplemental Fig. 3E-F).

Overall, these results demonstrate that TGFβ inhibitors down-regulate the expression of several fibrotic markers while moderately reversing the expression of RUNX2 in human primary MPCs. In comparison, the genetic knockdown of SMAD2 and SMAD3 demonstrated milder downregulation effects on the expression of fibrotic and osteogenic markers.

TGFβ inhibitors selectively regulate the formation of fibrotic nodules in vitro

In addition to the effects on the expression of fibrotic markers in primary MPCs, we were interested in investigating the effects of TGFβ inhibitors in a model of fibrotic nodule formation in vitro. Our model was modified from the protocol previously published by Xu et al.16 where they demonstrated that TGFβ1 induced nodule formation in mesenchymal and epithelial cells from kidney and other organs by disrupting the cell monolayer and inducing cell migration into nodules in a dose-, time- and Smad3-dependent manner. In our study, we used MPCs treated with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] and each TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542 [1 µM and 3 µM], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [1 µM and 3 µM], Halofuginone [10 nM and 30 nM] and SIS3 [10 µM and 20 µM]) for 4 days to investigate their effects in fibrotic nodule formation in vitro. At the end of 4 days, nodules were counted in each well and imaged or collected for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A-C, TGFβ ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299) reduced the number of fibrotic nodules (Non-treated Control: 0.0 ± 0.0; DMSO Control: 0.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 17.1 ± 4.2; SB431542 1 µM + TGFβ: 2.4 ± 2.5, p = 0.06; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 3.8 ± 3.4, p = 0.05; LY2157299 1 µM + TGFβ: 0.6 ± 1.0, p = 0.06; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.1 ± 0.2, p = 0.05).

Targeted TGFβ inhibitors selectively regulate the formation of fibrotic nodules in vitro. (A,B) Primary MPCs were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for 4 days. Results are representative of 2 independent donors. (C) Average ± SD number of nodules per well from three independent donors treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL]. (D) Average ± SD number of nodules per well from three independent donors treated with SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL]. Non-treated control was used for comparison and DMSO treatment was used as a vehicle control. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 2-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with the TGFβ treatment alone (*p ≤ 0.05). TGFB = TGFβ, SB = SB431542, LY = Galunisertib/LY2157299 and Halo = Halofuginone.

Interestingly, TGFβ SMAD3 inhibitor Halofuginone had no significant effects on the number of fibrotic nodules (Non-treated Control: 0.0 ± 0.0; DMSO Control: 0.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 17.1 ± 4.2; Halofuginone 10 nM + TGFβ: 18.6 ± 9.6, p = 0.69; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 25.2 ± 12.0, p = 0.24), while SIS3 demonstrated a dose-dependent effect on the number of fibrotic nodules observed (Non-treated Control: 0.0 ± 0.0; DMSO Control: 0.0 ± 0.0; TGFβ: 17.1 ± 4.2; SIS3 10 µM + TGFβ: 11.8 ± 5.9, p = 0.12; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 2.7 ± 2.2, p = 0.05; Fig. 4A-B and D).

In addition, we investigated the expression of fibrotic (ACTA2, COL1A1, COL3A1, VIM, FN1, SERPINE1, MMP9, and CDH2) and osteogenic (RUNX2, ALP, and BGLAP) markers following the fibrotic nodules assay. As shown in Fig. 5A-H; Tables 4 and 5, ALK5 TGFβ inhibitors (SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299) consistently downregulated the expression of fibrotic markers (ACTA2, COL1A1, COL3A1, FN1, SERPINE1, MMP9 and CDH2) following the fibrotic nodule formation assay in human primary MPCs. Interestingly, SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone and SIS3) had only mild (ACTA2 and COL1A1) or no (COL3A1, VIM, FN1, MMP9, and CDH2) effects in the same experimental conditions (Fig. 5A-H; Tables 4 and 5). Also of note, SERPINE1 was slightly upregulated following treatment with Halofuginone in the fibrotic nodule formation assay (Fig. 5F; Table 5).

ALK5 TGFβ inhibitors downregulate the expression of fibrotic markers following the fibrotic nodule formation assay in human primary MPCs. Primary MPCs were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for 4 days following the fibrotic nodule formation assay conditions. Relative expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR for the fibrotic markers (A) ACTA2, (B) COL1A1, (C) COL3A1, (D) VIM, (E) FN1, (F) SERPINE1, (G) MMP9 and (H) CDH2. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control gene. Non-treated control was used as a reference to calculate relative gene expression levels. DMSO treatment was used as a vehicle control. Average ± SE from three to seven independent donors. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 1-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with TGFβ treatment alone (*p ≤ 0.05). TGFB = TGFβ, SB = SB431542, LY = Galunisertib/LY2157299 and Halo = Halofuginone.

Remarkably, the TGFβ inhibitors SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299 consistently downregulated the expression of the osteogenic regulator RUNX2, while Halofuginone and SIS3 demonstrated no significant effects (RUNX2: Control: 1.11 ± 0.24; TGFβ: 3.97 ± 2.99; SB431542 1 µM ± TGFβ: 1.15 ± 0.45, p = 0.06; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.96 ± 0.53, p = 0.06; LY2157299 1 µM + TGFβ: 1.07 ± 0.53, p = 0.06; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.76 ± 0.31, p = 0.04; Halofuginone 10 nM + TGFβ: 3.43 ± 1.62, p = 0.27; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 2.99 ± 1.95, p = 0.14; SIS3 10 µM + TGFβ: 2.94 ± 1.77, p = 0.20; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 3.42 ± 2.07, p = 0.29; Fig. 6A). Finally, SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299 demonstrated a dose-dependent upregulation of ALP and a consistently upregulation of BGLAP (ALP: Control: 0.93 ± 0.35; TGFβ: 0.46 ± 0.28; SB431542 1 µM ± TGFβ: 0.78 ± 0.53, p = 0.21; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.45 ± 0.22, p = 0.48; LY2157299 1 µM + TGFβ: 1.78 ± 0.73, p = 0.04; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.51 ± 0.55, p = 0.04; BGLAP: Control: 1.09 ± 0.15; TGFβ: 0.87 ± 0.16; SB431542 1 µM ± TGFβ: 1.11 ± 0.48, p = 0.18; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.20 ± 0.33, p = 0.06; LY2157299 1 µM + TGFβ: 1.13 ± 0.22, p = 0.04; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.19 ± 0.36, p = 0.08; Fig. 6B-C), while Halofuginone and SIS3 had mostly mild effects on ALP and mostly no effects on BGLAP, with the exception of SIS3 [20 µM] that demonstrated a significant upregulation on the expression levels of BGLAP (ALP: Control: 0.93 ± 0.35; TGFβ: 0.46 ± 0.28; Halofuginone 10 nM + TGFβ: 0.39 ± 0.28, p = 0.29; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 0.32 ± 0.18, p = 0.17; SIS3 10 µM + TGFβ: 0.27 ± 0.18, p = 0.14; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 0.15 ± 0.07, p = 0.04; BGLAP: Control: 1.09 ± 0.15; TGFβ: 0.87 ± 0.16; Halofuginone 10 nM + TGFβ: 0.88 ± 0.15, p = 0.48; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 0.81 ± 0.15, p = 0.29; SIS3 10 µM + TGFβ: 0.87 ± 0.21, p = 0.48; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 1.08 ± 0.19, p = 0.04; Fig. 6B-C).

ALK5 TGFβ inhibitors downregulate the expression of the osteogenic regulator RUNX2 following the fibrotic nodule formation assay in human primary MPCs. Primary MPCs were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) and TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for 4 days following fibrotic nodule formation assay conditions. Relative expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR for the osteogenic markers (A) RUNX2, (B) ALP, and (C) BGLAP. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control gene. Non-treated control was used as a reference to calculate relative gene expression levels. DMSO treatment was used as vehicle control. Average ± SE from six to seven independent donors. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 1-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with TGFβ treatment alone (*p ≤ 0.05). TGFB = TGFβ, SB = SB431542, LY = Galunisertib/LY2157299 and Halo = Halofuginone.

Overall, our results showed that SB431542, Galunisertib/LY2157299, and SIS3 significantly decreased the formation of fibrotic nodules formed by MPCs in vitro, demonstrating (i) that TGFβ alone is sufficient to induce a fibrotic phenotype in post-traumatic MPCs and (ii) that these cells are a robust in vitro model for the study of human post-traumatic fibrosis.

TGFβ inhibitors SB431542, Galunisertib/LY2157299 and Halofuginone downregulate the expression of RUNX2 during osteogenic differentiation

Finally, the effects of the TGFβ inhibitors (SB431542, Galunisertib/LY2157299, Halofuginone, and SIS3) were investigated on the induction of osteogenic differentiation. Primary human MPCs have previously demonstrated the ability to differentiate into the adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages17,18,19. To investigate that we pre-treated MPCs with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] and each TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542 [3 µM], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [3 µM], Halofuginone [30 nM] and SIS3 [20 µM]) for 4 days followed by osteogenic differentiation as previously described17 for up to 2 weeks. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 4, SB431542, Galunisertib/LY2157299, and Halofuginone downregulated the expression of the osteogenic regulator RUNX2, while having no to mild effects on ALP and BGLAP. Interestingly, SIS3 had no significant effects on any of the osteogenic markers (1 week: ALP: Control: 0.94 ± 0.28; TGFβ: 0.76 ± 0.38; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.90 ± 0.50, p = 0.24; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.87 ± 0.18, p = 0.35; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 0.82 ± 0.26, p = 0.45; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 0.66 ± 0.42, p = 0.24; RUNX2: Control: 0.67 ± 0.28; TGFβ: 3.36 ± 1.94; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 2.63 ± 1.57, p = 0.21; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.69 ± 0.34, p = 0.20; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 1.17 ± 0.64, p = 0.20; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 3.46 ± 2.08, p = 0.35; BGLAP: Control: 1.05 ± 0.07; TGFβ: 1.19 ± 0.24; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.07 ± 0.19, p = 0.20; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.11 ± 0.06, p = 0.37; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 1.17 ± 0.29, p = 0.47; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 1.15 ± 0.27, p = 0.41; 2 weeks: ALP: Control: 0.92 ± 0.12; TGFβ: 0.48 ± 0.09; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.63 ± 0.16, p = 0.23; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.80 ± 0.19, p = 0.18; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 0.70 ± 0.21, p = 0.23; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 0.48 ± 0.12, p = 0.48; RUNX2: Control: 1.47 ± 0.26; TGFβ: 2.85 ± 1.06; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.78 ± 0.63, p = 0.18; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.25 ± 0.40, p = 0.20; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 1.94 ± 0.31, p = 0.23; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 3.25 ± 0.65, p = 0.23; BGLAP: Control: 1.34 ± 0.27; TGFβ: 1.02 ± 0.40; SB431542 3 µM + TGFβ: 0.97 ± 0.28, p = 0.43; LY2157299 3 µM + TGFβ: 1.31 ± 0.16, p = 0.23; Halofuginone 30 nM + TGFβ: 1.25 ± 0.36, p = 0.31; SIS3 20 µM + TGFβ: 0.99 ± 0.13, p = 0.48; Supplemental Fig. 4). Altogether, our results demonstrated that the osteogenic transcription factor RUNX2 was downregulated by the ALK5 TGFβ inhibitors (SB431542 and Galunisertib/LY2157299) and the SMAD3 inhibitor Halofuginone following up to 2 weeks of osteogenic differentiation in human primary MPCs compared to the TGFβ treatment alone.

TGFβ inhibitors SB431542, Halofuginone, and SIS3 demonstrated a trend towards a lower extent of HO formation on the in vivo rat blast model of HO formation

To investigate the in vivo effects of the TGFβ inhibitors, we used a previously described hind limb Sprague-Dawley rat blast model for post-traumatic HO20. Since our goal was to assess if the TGFβ inhibitors would block the formation of post-traumatic HO, treatments were delivered intraperitoneally immediately post-trauma and once daily for 2 weeks after blast injury. Animals were divided into four treatment groups (40 animals per group: 20 blast amputation group and 20 no-trauma control group) to test the effects of the TGFβ inhibitors [low dose, medium dose and high treatment dose, respectively]: SB431542 [5 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 30 µg/g bodyweight], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [16 µg/g, 30 µg/g and 36 µg/g bodyweight], Halofuginone [2.5 µg/g, 5 µg/g and 10 µg/g bodyweight] and SIS3 [2 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 50 µg/g bodyweight]. Each group included a set of 10 animals (5 blast amputation group and 5 no-trauma control group) each as a vehicle (DMSO) control group. Radiographs of the amputated limbs were performed as previously described20 and two independent reviewers graded the extent of HO visualized on radiographs (grade scale of 0–2: grade = 0 represented no HO, grade = 1 represented mild HO (> 0 but less than 25% of the diaphyseal diameter) and grade = 2 represented moderate to severe HO (more than > 25% of the diaphyseal diameter; modified from Hoyt et al.21). For the analysis, the timepoints were combined as follows: 1 week + 2 weeks, 1 month + 1.5 months, 2 months + 2.5 months, 3 months + 3.5 months, and 4 months. As shown in Fig. 7A-D, a trend towards a lower extent of HO formation was observed upon SB431542 treatment throughout all doses and timepoints as well as upon Halofuginone high dose at 1 month + 1.5 months, 2 months + 2.5 months, 3 months + 3.5 months, and 4 months. In addition, SIS3 showed a trend towards a lower extent of HO formation following all doses in the 1 week + 2 weeks timepoint and following medium and high doses at the 1 month + 1.5 months, 2 months + 2.5 months, and 3 months + 3.5 months timepoints. Using a linear mixed model on the extent of HO formation, only a few treatments and doses were statistically significant as follows: 2 weeks timepoint: Control vs. Halofuginone low dose: p = 0.03, Control vs. Halofuginone medium dose: p = 0.02 and Control vs. Halofuginone high dose: p = 0.01; 2 months timepoint: Control vs. SB431542 high dose: p = 0.05 and Control vs. Galunisertib (LY2157299) high dose: p = 0.01; 2.5 months timepoint: Control vs. SB431542 high dose: p = 0.05; 3.5 months timepoint: Control vs. Halofuginone low dose: p = 0.05 and 4 months timepoint: Control vs. Halofuginone low dose: p = 0.05. If treatment doses are combined, the TGFβ inhibitors only showed minor effects using the linear mixed model on the extent of HO formation by radiographic analysis in the in vivo rat blast model of HO (1 week + 2 weeks: Control vs. SB431542 all doses: p = 0.706; Control vs. Galunisertib (LY2157299) all doses: p = 0.444; Control vs. Halofuginone all doses: p = 0.408; Control vs. SIS3 all doses: p = 0.191; 1 month + 1.5 months: Control vs. SB431542 all doses: p = 0.170; Control vs. Galunisertib (LY2157299) all doses: p = 0.596; Control vs. Halofuginone all doses: p = 0.769; Control vs. SIS3 all doses: p = 0.149; 2 months + 2.5 months: Control vs. SB431542 all doses: p = 0.012; Control vs. Galunisertib (LY2157299) all doses: p = 0.062; Control vs. Halofuginone all doses: p = 0.450; Control vs. SIS3 all doses: p = 0.149; 3 months + 3.5 months: Control vs. SB431542 all doses: p = 0.170; Control vs. Galunisertib (LY2157299) all doses: p = 0.164; Control vs. Halofuginone all doses: p = 0.063; Control vs. SIS3 all doses: p = 0.306 and 4 months: Control vs. SB431542 all doses: p = 0.166; Control vs. Galunisertib (LY2157299) all doses: p = 0.195; Control vs. Halofuginone all doses: p = 0.048; Control vs. SIS3 all doses: p = 0.974).

SB431542, Halofuginone, and SIS3 show a trend towards a lower extent of HO formation by radiographic analysis in an in vivo rat blast model of HO. Animals underwent routine X-ray assessments beginning after the first month following amputation for 2-week intervals for the remainder of their survival. (A) SB431542, (B) Galunisertib/LY2157299, (C) Halofuginone or (D) SIS3. Low dose, medium dose and high treatment dose, respectively, were administered as follows: SB431542 [5 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 30 µg/g bodyweight], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [16 µg/g, 30 µg/g and 36 µg/g bodyweight], Halofuginone [2.5 µg/g, 5 µg/g and 10 µg/g bodyweight] and SIS3 [2 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 50 µg/g bodyweight]. Grade scale of 0–2: grade = 0 represented no HO; grade = 1 represented mild HO (> 0 but less than 25% of the diaphyseal diameter), and grade = 2 represented moderate to severe HO (more than > 25% of the diaphyseal diameter; modified from Hoyt et al.21). Grades for each radiograph were averaged to give a final score for each image. 1wk = 1 week; 2wks = 2 weeks; 1 M = 1 month; 1.5 M = 1.5 months; 2 M = 2 months; 2.5 M = 2.5 months; 3 M = 3 months; 3.5 M = 3.5 months; 4 M = 4 months. Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed model (*p ≤ 0.05).

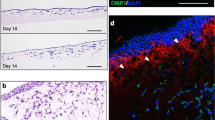

For histology and gene expression analyses from each treatment condition, two animals were sacrificed at the 2-week timepoint and three animals were sacrificed at the 4-month timepoint following blast injury, and the hindlimb was fixed in a 10% formalin solution followed by histology preparation and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as well as RNA isolation and q-RT-PCR analysis for fibrotic (Acta2, Col1a1, Col3a1, Fn1 and Serpine1) and osteogenic (Alp and Runx2) genes. Stained H&E slides were analyzed and scored in bright-field microscopy by an experienced pathologist. For the ANOVA statistical analysis, the low, medium, and high treatment doses from each drug were combined and only sample categories that met the assumption of equal variances across the groups were included in the analysis. In addition, only the 4-month blasted timepoint was analyzed since the non-blasted group had no variability and the 2-week timepoint (blasted and non-blasted groups) had a small sample size (2 animals each) and could not be included in the analysis. Histologic findings included tissue degeneration (ANOVA between groups: p = 0.480), loss of fibrosis (ANOVA between groups: p = 0.879), chronic inflammation (ANOVA between groups: p = 0.949), and multinucleated giant cells (ANOVA between groups: p = 0.671). Of note, additional categories of interest such as HO formation, ossification, mineralization, acute inflammation, and tissue regeneration failed the Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances and were not analyzed.

Finally, gene expression analyses were performed by q-RT-PCR for fibrotic (Acta2, Col1a1, Col3a1, Fn1, and Serpine1) and osteogenic (Alp and Runx2) genes on the 2 weeks and 4 months timepoints following blast injury. As shown in Fig. 8, on blast-injury animals, Acta2 was not significantly downregulated following 2 weeks of SB431542 low-dose (Control: 1.15 ± 0.62; SB431542 low: 0.72 ± 0.03; p = 0.37) and 4 months of high dose treatment (Control: 1.04 ± 0.31; SB431542 high: 0.75 ± 0.45; p = 0.39). In addition, we observed a downregulation of Acta2 upon Galunisertib/LY2157299 low and medium doses at 4 months (Control: 1.04 ± 0.31; LY2157299 low: 0.18 ± 0.06; p = 0.18 and LY2157299 medium: 0.58 ± 0.23; p = 0.25) as well as upon SIS3 low and medium doses at 2 weeks (Control: 1.15 ± 0.62; SIS3 low: 0.48 ± 0.02; p = 0.23 and SIS3 medium: 0.60 ± 0.29; p = 0.28; Fig. 8A).

TGFβ inhibitors modulation of the expression of fibrotic markers in an in vivo rat blast model of HO. Following blast injury, animals were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) for 2 weeks (n = 02) and up to for 4 months (n = 03). Low dose, medium dose and high treatment dose, respectively, were administered as follows: SB431542 [5 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 30 µg/g bodyweight], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [16 µg/g, 30 µg/g and 36 µg/g bodyweight], Halofuginone [2.5 µg/g, 5 µg/g and 10 µg/g bodyweight] and SIS3 [2 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 50 µg/g bodyweight]. Relative expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR for the fibrotic markers (A) Acta2, (B) Col1a1, (C) Col3a1, (D) Fn1 and (E) Serpine1. β-actin (Actb) was used as a housekeeping control gene. Non-treated (vehicle) control was used as a reference to calculate relative gene expression levels. Average ± SD from independent animals. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 1-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with the control group from each timepoint.

Col1a1 was downregulated following 2 weeks SB431542 low-dose (Control: 1.24 ± 0.88; SB431542 low: 0.44 ± 0.13; p = 0.32) and 4 months SB431542 medium and high doses (Control: 1.13 ± 0.52; SB431542 medium: 0.56 ± 0.38; p = 0.28 and SB431542 high: 0.65 ± 0.35; p = 0.36). Moreover, Col1a1 was downregulated following 4 months of Galunisertib/LY2157299 low, medium and high doses (Control: 1.13 ± 0.52; LY2157299 low: 0.42 ± 0.26; p = 0.21; LY2157299 medium: 0.87 ± 0.46; p = 0.30 and LY2157299 high: 0.89 ± 0.75; p = 0.28). Col1a1 was also downregulated following 2 weeks SIS3 low and medium doses (Control: 1.24 ± 0.88; SIS3 low: 0.40 ± 0.06; p = 0.23 and SIS3 medium: 0.51 ± 0.08; p = 0.24) and 4 months SIS3 high dose (Control: 1.13 ± 0.52; SIS3 high: 0.50 ± 0.08; p = 0.28; Fig. 8B).

Col3a1 was downregulated following 4 months of medium and high dose treatments with SB431542 (Control: 1.10 ± 0.45; SB431542 medium: 0.82 ± 0.62; p = 0.33 and SB431542 high: 0.56 ± 0.31; p = 0.36) as well as Galunisertib/LY2157299 4 months low and medium dose treatments (Control: 1.10 ± 0.45; LY2157299 low: 0.52 ± 0.44; p = 0.21; LY2157299 medium: 0.83 ± 0.49; p = 0.25). Col3a1 was also downregulated following 2 weeks of treatment with SIS3 low and medium doses (Control: 1.05 ± 0.33; SIS3 low: 0.67 ± 0.08; p = 0.28; SIS3 medium: 0.83 ± 0.02; p = 0.21) and 4 months of treatment with SIS3 high dose (Control: 1.10 ± 0.45; SIS3 high: 0.69 ± 0.004; p = 0.25; Fig. 8C).

As shown in Fig. 8D, Fn1 was downregulated following 2 weeks of SB431542 low dose treatment (Control: 1.10 ± 0.49; SB431542 low: 0.68 ± 0.03; p = 0.28) and 4 months of SB431542 high dose treatment (Control: 1.06 ± 0.35; SB431542 high: 0.78 ± 0.28; p = 0.36) as well as following 4 months of Halofuginone high dose treatment (Control: 1.06 ± 0.35; Halofuginone high: 0.91 ± 0.35; p = 0.34). Finally, SIS3 treatment downregulated Fn1 expression levels at low and medium doses after 2 weeks (Control: 1.10 ± 0.49; SIS3 low: 0.57 ± 0.08; p = 0.33 and SIS3 medium: 0.70 ± 0.03; p = 0.33) as well as at high dose after 4 months of treatment (Control: 1.06 ± 0.35; SIS3 high: 0.94 ± 0.10; p = 0.34).

Serpine1 downregulation (Fig. 8E) was observed upon 2 weeks of SB431542 high dose (2 weeks: Control: 1.16 ± 0.54; SB431542 high: 0.61 ± 0.10; p = 0.28), Galunisertib/LY2157299 medium and high doses (2 weeks: Control: 1.16 ± 0.54; LY2157299 medium: 0.66 ± 0.00; p = 0.47; LY2157299 high: 0.54 ± 0.01; p = 0.34). Serpine1 was also downregulated by 2 weeks Halofuginone low dose (Control: 1.16 ± 0.54; Halofuginone low: 0.61 ± 0.16; p = 0.33), 4 months Halofuginone high dose (Control: 1.52 ± 1.33; Halofuginone high: 0.56 ± 0.12; p = 0.25) and 2 weeks and 4 months of SIS3 low dose treatments (2 weeks: Control: 1.16 ± 0.54; SIS3 low: 0.86 ± 0.50; p = 0.38; 4 months: Control: 1.52 ± 1.33; SIS3 low: 0.72 ± 0.34; p = 0.38).

In addition to the fibrotic genes, two osteogenic genes were investigated: Alp and Runx2 (Fig. 9). Alp was downregulated following 2 weeks of treatment with SB431542 medium dose (Control: 1.30 ± 0.93; SB431542 medium: 0.93 ± 0.63; p = 0.37), 4 months of treatment with SB431542 high dose (Control: 1.21 ± 0.66; SB431542 high: 1.08 ± 0.73; p = 0.37) and 4 months of treatment with LY2157299 medium dose (Control: 1.21 ± 0.66; LY2157299 medium: 0.91 ± 0.89; p = 0.45). Moreover, downregulation of Alp was observed upon 2 weeks of Halofuginone low, medium and high doses treatments (Control: 1.30 ± 0.93; Halofuginone low: 0.98 ± 0.52; p = 0.36; Halofuginone medium: 0.91 ± 0.13; p = 0.41; Halofuginone high: 0.75 ± 0.60; p = 0.41) and 4 months Halofuginone low and medium doses treatments (Control: 1.21 ± 0.66; Halofuginone low: 0.94 ± 0.56; p = 0.39; Halofuginone medium: 0.54 ± 0.46; p = 0.36). Finally, Alp expression levels were downregulated upon 2 weeks of treatment with low and medium doses of SIS3 (Control: 1.30 ± 0.93; SIS3 low: 0.85 ± 0.14; p = 0.39; SIS3 medium: 1.07 ± 0.49; p = 0.43) and 4 months of treatment with high doses of SIS3 (Control: 1.21 ± 0.66; SIS3 high: 0.91 ± 0.40; p = 0.33).

TGFβ inhibitors modulation of the expression of osteogenic markers in an in vivo rat blast model of HO. Following blast injury, animals were treated with ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 or Galunisertib/LY2157299) and SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone or SIS3) for 2 weeks (n = 02) and up to for 4 months (n = 03). Low dose, medium dose and high treatment dose, respectively, were administered as follows: SB431542 [5 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 30 µg/g bodyweight], Galunisertib/LY2157299 [16 µg/g, 30 µg/g and 36 µg/g bodyweight], Halofuginone [2.5 µg/g, 5 µg/g and 10 µg/g bodyweight] and SIS3 [2 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 50 µg/g bodyweight]. Relative expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR for the osteogenic markers (A) Alp and (B) Runx2. β-actin (Actb) was used as a housekeeping control gene. Non-treated (vehicle) control was used as a reference to calculate relative gene expression levels. Average ± SD from independent animals. Adjusted p-value was calculated by 1-tail Student’s T-test in comparison with the control group from each timepoint.

Finally, Runx2 expression levels were downregulated following 2 weeks of Halofuginone low and medium doses (Control: 1.28 ± 0.98; Halofuginone low: 0.95 ± 0.40; p = 0.48 and Halofuginone medium: 1.26 ± 0.57; p = 0.32) and 4 months of Halofuginone high doses (Control: 2.30 ± 2.38; Halofuginone high: 1.34 ± 0.47; p = 0.32). In addition, Runx2 was downregulated after 2 weeks of SIS3 low and high dose treatments (Control: 1.28 ± 0.98; SIS3 low: 0.91 ± 0.48; p = 0.34 and SIS3 high: 0.89 ± 0.07; p = 0.36), and 4 months of SIS3 low dose treatment (Control: 2.30 ± 2.38; SIS3 low: 0.62 ± 0.30; p = 0.32). Lastly, for comparison, the effect of the TGFβ inhibitors on the expression of the fibrotic and osteogenic markers in the not-blasted control animals is shown in Supplemental Fig. 5.

Discussion

HO is characterized by the abnormal growth of ectopic bone in non-skeletal soft tissues and is a frequent complication in battlefield injuries1. Current combat operations yield large numbers of traumatic musculoskeletal injuries that are characterized by traumatized muscles and have been associated with the development of post-traumatic HO2. Importantly, following combat trauma, wound closure is often delayed, leading to sub-optimal healing. In this study, we aimed to further understand the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in the development of post-traumatic fibrosis and HO. We previously showed that TGFβ levels were elevated in the soft tissues of war-traumatized extremity injuries6 and TGFβ activity has been demonstrated to be elevated in traumatic human HO, such as following internal fixation for elbow fracture or after central nervous system trauma11,22. In addition, macrophage infiltration and activation of TGFβ signaling have been demonstrated to be essential for human HO formation23,24. Since TGFβ significantly mediates the initial inflammatory and wound healing response in the traumatized muscle bed25,26,27,28, we hypothesized that targeted inhibition of the TGFβ pathway may be able to abrogate the unbalanced fibrotic phenotype and bone-forming response observed in HO after a traumatic event. Here we focused on the investigation of selected TGFβ targeted inhibitors as a novel potential therapeutical strategy for the prevention and treatment of post-traumatic fibrosis and HO.

We focused our efforts on drugs encompassing two classes of TGFβ1 inhibitors that directly block the TGFβ1 receptor (ALK5 inhibitors: SB431542 and LY2157299) or block downstream signaling components of the TGFβ1 pathway (SMAD3 inhibitors: Halofuginone and SIS3). To characterize the effects of these selected TGFβ1 targeted therapies we established an in vitro model of HO formation that consists of human primary MPCs harvested from traumatized muscle tissue treated with recombinant TGFβ1. As expected, the TGFβ inhibitors selectively regulated SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in human primary MPCs. Furthermore, studies performed in human primary MPCs treated with TGFβ1 alone and each TGFβ1 inhibitor for 4 days and 1 week demonstrated variable effects in the proliferation and survival of MPCs, however, no major deleterious effects were observed upon the treatment of human primary MPCs with these two classes of TGFβ1 inhibitors. Importantly, the TGFβ1 treatment alone showed a 17–19% reduction in the cell proliferation and survival of MPCs, suggesting that – to a certain extent – TGFβ1 inhibits the proliferation of human primary MPCs. TGFβ-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation has been widely investigated and previously reviewed in the literature and is known to effectively inhibit cell cycle progression only during the G1 phase in a wide variety of cells such as epithelial, endothelial, hematopoietic, and certain types of mesenchymal cells29,30,31.

Post-traumatic fibrosis is a significant orthopedic challenge characterized as a non-functional tissue that leads to incomplete functional recovery. The fibrotic process is known to cause significant changes in tissue properties, such as enhanced density and stiffness as well as lower pH and oxygenation32. There are currently no significant anti-fibrotic therapeutic approaches to counteract and/or reverse fibrosis. TGFβ is a well-known and essential pro-fibrotic factor, and inhibition of the TGFβ pathway has been investigated as a potential anti-fibrotic therapeutical strategy33,34,35,36. We hypothesized that post-traumatic TGFβ-mediated fibrosis may lead to HO formation. As such, we investigated the effects of TGFβ inhibitors in the expression of fibrotic markers and fibrotic nodule formation in human primary MPCs. MPCs treated with TGFβ alone had increased levels of the fibrotic markers ACTA2 (9.5-fold change), COL1A1 (4.8-fold change), FN1 (4.1-fold change), and SERPINE1 (5.6-fold change) and an increased expression of the osteogenesis regulator RUNX2 (1.9-fold change) compared to the vehicle control demonstrating that TGFβ alone is sufficient to induce a fibrotic and osteogenic phenotype in human post-traumatic MPCs and that these cells are a robust in vitro model for the study of HO formation and progression. Furthermore, we observed that TGFβ inhibitors mostly downregulated the expression of fibrotic markers (ACTA2, COL1A1, FN1, and SERPINE1) after 48 h of treatment, while the osteogenic regulator RUNX2 was selectively modulated (trending towards upregulated following treatment with ALK5 inhibitors and downregulated following treatment with SMAD3 inhibitors) after 1 week of treatment in comparison to the TGFβ treatment alone. Genetic downregulation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 demonstrated mild effects on the expression of fibrotic and osteogenic markers, suggesting that pharmacologic inhibition of SMAD2/3 was more effective in modulating the expression of fibrotic genes and the osteogenic regulator RUNX2 in our in vitro model of HO formation.

Remarkably, both ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 and LY2157299) and the SMAD3 inhibitor SIS3 significantly decreased the formation of fibrotic nodules formed by MPCs in vitro. Also of interest, when the gene expression of fibrotic and osteogenic markers was investigated on the fibrotic nodules, we observed that SB431542 and LY2157299 downregulated the expression of fibrotic markers, while the SMAD3 inhibitors had no effects on the expression of fibrotic markers despite SIS3 effects on the fibrotic nodules’ formation assay. The significance of these results will need to be further investigated. Finally, among the osteogenic markers only the expression of RUNX2 was downregulated by ALK5 inhibitors following the fibrotic nodule formation assay in human primary MPCs compared to the TGFβ treatment alone. Inhibition of TGFβ signaling by SB431542 has been demonstrated to decrease fibrosis in a mouse model of massive rotator cuff tear37, decrease the expression of fibrotic factors in a rat model of silicotic fibrosis38 and, alleviate liver fibrosis in vivo39. LY2157299 as well as other ALK5 inhibitor compounds such as J-1063 have also shown anti-fibrotic effects in vivo40. Additionally, halofuginone inhibited tissue fibrosis41 and, was tested in animal models and human clinical trials for the treatment of dermal fibrosis42. In these studies, halofuginone was demonstrated to inhibit collagen synthesis, decrease collagen content, and reduce skin scores, providing a foundation for the potential use of halofuginone in the treatment of dermal fibrosis42. Recently, halofuginone was also tested in an animal model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which is associated with significant muscle fibrosis, showing decreased collagen content and tissue degeneration42. Lastly, treatment with SIS3 ameliorated fibrosis by decreasing fibrotic markers such as extracellular matrix deposition, fibronectin staining intensity, and collagen I/III expression levels in a mouse model of kidney unilateral ureteral obstruction43. An amelioration in the fibrotic phenotype and collagen deposition was also observed following treatment with SIS3 in a mouse model of submandibular gland dysfunction44 as well as in a bleomycin-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis45. Altogether, these results demonstrate the translational potential of the TGFβ inhibitors used in this study to ameliorate the fibrotic phenotype in a wide range of fibrotic models and systems. Moreover, in our study, ALK5 inhibitors were sufficient to abrogate the fibrotic nodule formation and reduce the expression of fibrotic markers in vitro, while only SIS3 among the SMAD3 inhibitors had a dose-dependent effect on the formation of fibrotic nodules.

The canonical signaling pathway downstream of TGFβ involves the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, which forms a complex with SMAD4 and translocates to the nucleus to modulate the transcription of downstream targets. However, it has been demonstrated that SMAD2 and SMAD3 have different sensitivities in response to TGFβ signaling12,13. In addition, the nuclear C-terminal domain small phosphatase 1 has been shown to dephosphorylate the linker regions of SMAD2/3 in vitro46,47 and, interestingly, SMAD2 and SMAD3 linker regions are distinct from each other12. As a result, the differences observed between ALK5 and SMAD3 inhibitors in this study may be a result of differences in the activation/inactivation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 or a result of the activation of TGFβ non-canonical pathways that are independent of SMAD2/3. Additional studies will need to be performed to elucidate these mechanistic differences and underlying molecular mechanisms.

Finally, we investigated the ALK5 inhibitors (SB431542 and LY2157299) and the SMAD3 inhibitors (Halofuginone and SIS3) in a previously described in vivo rat blast model of HO formation20. TGFβ inhibitors SB431542, Halofuginone, and SIS3 demonstrated a trend towards a lower extent of HO formation by radiographic analysis up to 4 months after injury in vivo. However, it remains unclear what stage and/or phase of the post-traumatic HO process was affected by the TGFβ inhibitors as well as if any of the treatments inhibited the formation of cartilage, which was not investigated in this study. Additional studies are needed to answer these questions. In addition, the expression of the osteogenic markers Alp and Runx2 was investigated by q-RT-PCR, however, while downregulation was observed in some of the treatment conditions these results did not reach statistical significance. This may be a result of the small number of animals in each sub-group of the study (each sub-group in the blasted group and non-blasted group had 20 animals per drug treatment and 5 animals for each sub-group dose of the treatment or vehicle control, where 2 animals were sacrificed after 2 weeks of treatment and 3 animals were sacrificed after 4 months of treatment). We believe this small number of animals in each sub-group is one of the main limitations of the study (see Fig. 10). Importantly, inhibition of TGFβ has been previously reported to attenuate the progression of HO in distinct mice models of HO formation11,48. In addition, depletion of macrophages inhibited TGFβ activation and suppressed the formation of traumatic HO in vivo23 as well as inhibition of TGFβ hindered and/or decreased the formation of HO in vivo23,24. Finally, Galunisertib (LY2157299), one of the TGFβ inhibitors used in our study, was recently reported to prevent the development of HO in an in vivo Achilles tendon puncture traumatic HO model by blocking the phosphorylation of Smad2/349. Mao and colleagues also demonstrated that treatment with Galunisertib (LY2157299) in the early stages of HO development was more effective in preventing HO formation than reversing HO once established, suggesting that Galunisertib may be an effective prophylactic treatment for post-traumatic HO49.

It is possible that the relevance of our findings may also be extended to types of HO that are beyond post-traumatic HO, which was the focus of our study. Recently, it has been reported that the brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1 (Bmal1) negatively regulates aging-related HO of tendons and ligaments through the TGFβ-bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway in vivo50. Moreover, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), a genetic condition associated with congenital skeletal malformations and progressive HO formation is caused by a mutation in the activin receptor IA/activin-like kinase 2 (ACVR1/ALK2), which is part of the TGFβ-BMP signaling pathway51,52. In the context of FOP, TGFβ inhibition was shown to attenuate the progression of HO in a BMP-induced FOP in vivo model11, and additional inhibitors targeting ALK2 are under development to treat patients with FOP53.

Overall, there are intricate TGFβ signaling mechanisms where extracellular and intracellular TGFβ levels may contribute to the formation of post-traumatic ectopic bone. Our results support the notion that targeted modulation of the TGFβ pathway may decrease the incidence of fibrosis and ectopic bone formation and has the potential to be a useful therapeutic strategy for post-traumatic HO patients.

Methods

Ethics statement and clinical samples

Primary MPCs were harvested from debrided traumatized human muscle tissue from injured service members during their initial surgical debridement at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Tissue specimens used in this study were taken at the margin of devitalized and healthy-appearing tissue that would otherwise be discarded as surgical waste. The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this tissue procurement protocol and the need to obtain informed consent was waived by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The amount of tissue debrided was determined by the operative surgeon. After surgical debridement of the tissue, de-identified samples were placed in a sterile container and transported on ice to the laboratory for processing.

MPCs harvest and culture

Cells were harvested from traumatized muscle tissue of patients undergoing surgical debridement as previously described17,19,54,55. MPCs have been previously phenotypically characterized and demonstrated the ability to undergo osteogenesis, adipogenesis, and chondrogenesis in vitro17,19,54,55. Briefly, the healthy margin of the debrided tissue was washed in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA), minced, and incubated with Collagenase type 2 [0.5 mg/mL] (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) for 2 h at 37 °C with agitation. Following incubation, the tissue was filtered through cell strainers (100 µM and 40 µM, Corning, Glendale, AZ), pelleted, and resuspended in growth medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium [DMEM] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS] and 3X Penicillin/Streptomycin and Fungizone, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were plated and incubated at 37 °C on tissue culture plastic for 2 h, followed by washes with HBSS to remove the non-adherent cells and enrich MPCs isolation. After 1 day in culture, the growth medium consisted of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X Penicillin/Streptomycin and Fungizone (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The culture of the adherent cells was maintained until confluence (approximately 2 weeks), and cells were used for experiments between passages 3 and 6.

Treatment with TGFβ inhibitors on monolayer MPCs

Primary MPCs were seeded at a density of 1,000 cells/cm2 and treated for 48 h or 1 week with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI) and the TGFβ inhibitors SB431542 [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Galunisertib (LY2157299) [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Halofuginone [3 nM, 10 nM, and 30 nM] or SIS3 [3 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM] as indicated in each experiment. All inhibitors were commercially available from MedChem Express. DMSO alone [20 µM] was used as vehicle control and TGFβ [10 ng/mL] (Sigma-Aldrich) alone was used as experimental control. Experiments were performed on three to seven independent donors as indicated in each figure caption or table description.

Cell viability assays

Cell viability assays were performed in 96-well microtiter plates containing 2,000 primary MPCs per well using the MTT reagent (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). MPCs were treated with SB431542 [0.1 µM, 0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Galunisertib (LY2157299) [0.1 µM, 0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Halofuginone [1 nM, 3 nM, 10 nM, and 30 nM] and SIS3 [1 µM, 3 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM] with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] for 4 days and 1 week. DMSO treatment was used as vehicle control. The DMSO volume used corresponded to the highest volume of DMSO used within the dilution of the TGFβ inhibitors. The formazan dye formed by the viable cells was quantified by measuring the absorbance of the dye solution at 590 nM following the manufacturer’s instructions. The percentage of cell proliferation/survival was calculated relative to the DMSO (vehicle control) treatment.

Transfection with SMAD2 or SMAD3 siRNAs on monolayer MPCs

Transfection of SMAD2 or SMAD3 siRNAs was performed in MPCs using 25 nM siRNAs (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the presence or absence of TGFβ [10 ng/mL] (Sigma-Aldrich) and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions and compared to a negative control (scramble) siRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA and protein samples were collected 48 h after transfection as described below.

Fibrotic nodules formation assay

Ninety-six well tissue culture plates were coated with 20 µg/mL Poly-L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, plates were washed 3 times with PBS 1X (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immediately after coating, 10,000 MPCs per well were seeded on coated plates in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X Penicillin/Streptomycin and Fungizone, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 overnight as previously described16. The following day, with a confluence range between 80 and 100%, cells were washed once with serum-free DMEM, and cultured for 24 h before any additional experiments were performed in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS as previously described16. Treatment with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] (Sigma-Aldrich) with or without the TGFβ inhibitors SB431542 [1 µM and 3 µM], Galunisertib (LY2157299) [1 µM and 3 µM], Halofuginone [10 nM and 30 nM] or SIS3 [10 µM and 20 µM] as indicated were performed for 4 days. On day 4, nodules were collected in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for RNA extraction, or nodules were counted and representative pictures from each condition were taken on a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Osteogenic differentiation

MPCs isolated from traumatized human muscle tissue were induced to osteogenic differentiation as previously described17,54. Monolayer cultures of multiprogenitor cells were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2 and treated for 4 days with TGFβ [10 ng/mL] (Sigma-Aldrich) and the TGFβ inhibitors SB431542 [3 µM], Galunisertib (LY2157299) [3 µM], Halofuginone [30 nM] or SIS3 [20 µM] as indicated. Following treatment with the inhibitors, cells were treated for up to 2 weeks with osteogenic medium, consisting of DMEM with 10% FBS supplemented with10 mM β-Glycerol phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 nM 1,25-di-hydroxyvitamin D3 (BIOMOL International, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and 0.01 µM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich). After each week of induction, RNA was collected for q-RT-PCR analysis of the osteogenic markers RUNX2, ALP, and BGLAP (see methods below). Experiments were performed in 3 independent donors as indicated.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR analysis on human primary MPCs samples

Gene expression analyses for fibrotic (ACTA2, COL1A1, COL3A1, FN1, SERPINE1, MMP2, MMP9, CDH2, and VIM) and osteogenic (RUNX2, ALP and BGLAP) markers were performed following 2 days or 1 week of treatment with TGFβ and each respective TGFβ inhibitor (monolayer experiments) or following 4 days of treatment with TGFβ and each respective TGFβ inhibitor (fibrotic nodules formation experiments). Following treatments with SMAD2 or SMAD3 siRNAs, gene expression analyses for SMAD2 or SMAD3 were performed 48 h after transfection. In addition, fibrotic (ACTA2, COL1A1, COL3A1, VIM, FN1, SERPINE1, MMP9, and CDH2) and osteogenic (RUNX2, ALP, and BGLAP) markers were analyzed on these samples. A scramble transfection was used as control. RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions and purified using RNeasy Mini columns (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RNA concentration was measured with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis. The relative gene expression analyses were performed by q-RT-PCR with an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 7 Flex real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene expression was normalized using GAPDH as an internal housekeeping control.

Western blot analysis

Primary MPCs were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2 and treated with SB431542 [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Galunisertib (LY2157299) [0.3 µM, 1 µM, and 3 µM], Halofuginone [3 nM, 10 nM, and 30 nM] or SIS3 [5 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM] with TGFβ [10 ng/mL]. DMSO treatment was used as vehicle control. SB431542 and LY2157299 treatments were performed simultaneously with the TGFβ treatment for 30 min. Halofuginone treatment was performed for 24 h before TGFβ treatment for 30 min and SIS3 treatment was performed for 24 h before TGFβ treatment for 15 min. Optimization studies were performed to determine the appropriate dose of TGFβ inhibitors, and the time required to detect phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 on primary MPCs. Alternatively, primary MPCs were treated with SMAD2 or SMAD3 siRNAs for 48 h. A scramble transfection was used as control. Following treatments, protein extraction and analyses were performed following standard protocols using RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total protein extracts were centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were used for downstream analyses. Protein quantification was performed using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten to twenty µg of total protein extracts were separated by gel electrophoresis using a NuPAGE® 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Applied Biosystems), followed by transference onto nitrocellulose membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were incubated with antibodies against phosphorylated SMAD family member 2 (SMAD2), phosphorylated SMAD family member 3 (SMAD3), total SMAD2 or total SMAD3 (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) as indicated. Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a loading control. Detection was performed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit secondary antibody (EMD/Millipore, Burlington, MA; 1:10,000) followed by Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate Kit (EMD/Millipore). Images were acquired on a ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Rat blast model and tissue collection

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina. Animal experiments were performed in compliance with the “Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments” (ARRIVE) guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org/). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Animals were male Sprague-Dawley rats, skeletally mature, averaging 24 weeks of age, and weighing between 350 and 400 gm (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN). Using a previously described hind limb rat protocol20, rats (n = 160 distributed as follows: n = 80 blast amputation group and n = 80 no-trauma control group) were first anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (7 mg/kg) delivered intraperitoneally, and pre-blast doses of enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg) and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) were administered subcutaneously for antisepsis and analgesia, respectively20. The blast setup consisted of a 12 × 12 × 2-inch aluminum platform welded above a 2 × 2 × 2-foot steel tank. The animals were positioned sternally and secured onto the platform with two industrial-sized Velcro straps across the chest and abdomen. The platform had a hole through its center that was 2.5 inches in diameter, over which the designated hindlimb was held exposed, 5–10 mm distal to the knee joint. The tank was filled with water up to a level of 1 inch beneath the bottom of the platform. The Pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN) explosive was submerged 0.5 inch beneath the surface of the water, and directly beneath the center of the hole in the platform, at a total stand-off distance of 3.5 inches from the top of the platform. PETN detonation caused a column of water to travel through the opening in the platform and amputate the exposed extremity. Immediately afterward, injured rats were transferred to a sterile field for wound management and primary surgical closure. A detailed description of the blast setup, blast, surgical closure, and post-blast care has been previously reported20. Rodents in the blast amputation group and no-trauma control group were divided into four treatment groups to test the effects of the following TGFβ inhibitors [low dose, medium dose, and high treatment dose, respectively]: SB431542 [5 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 30 µg/g bodyweight, the volume of administration approximately 100 µL, route intraperitoneal], Galunisertib (LY2157299) [16 µg/g, 30 µg/g and 36 µg/g bodyweight, the volume of administration approximately 100 µL, route intraperitoneal], Halofuginone [2.5 µg/g, 5 µg/g and 10 µg/g bodyweight, the volume of administration approximately 100 µL, route intraperitoneal] and SIS3 [2 µg/g, 10 µg/g and 50 µg/g bodyweight, the volume of administration approximately 100 µL, route intraperitoneal]. Each group included a vehicle control group treated with DMSO [DMSO, 5% v/v in water, the volume of administration approximately 100 µL, route intraperitoneal]. All treatments were performed once daily starting immediately after blast amputation and continued for 2 weeks (Fig. 10). For each treatment condition, two animals were sacrificed at a 2-week timepoint, three animals were sacrificed at a 4-month timepoint, and the hindlimb was fixed in a 10% formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich). In the acute postoperative period, rats were monitored for signs of distress and given a 5-day course of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg administered subcutaneously twice a day) and enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg administered subcutaneously twice a day). Radiographs of the amputated limbs were performed with a digital Faxitron radiography machine (Faxitron X-Ray LLC, Lincolnshire, IL) as previously described20. The 4-month survival groups underwent routine X-ray assessments beginning after the first month following amputation for 2-week intervals for the remainder of their survival. Two independent reviewers graded the extent of HO visualized on radiographs. HO was graded on a scale of 0–2, whereby a grade of 0 represented no HO, a grade of 1 represented mild HO (defined as > 0 but less than 25% of the diaphyseal diameter), and a grade of 2 represented moderate to severe HO (defined as more than > 25% of the diaphyseal diameter). The grading scale was modified from Hoyt et al.21 for this study. Grades for each radiograph were averaged to give a final score for each image. All animal procedures were performed under approved appropriate protocols by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR analysis on rat blast model tissue samples

Gene-expression analyses for fibrotic (Acta2, Col1a1, Col3a1, Fn1 and Serpine1) and osteogenic (Alp and Runx2) markers were performed in all rodent tissue samples. Two twenty-micron thick sections from each sample were cut and RNA was extracted using miRNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was measured with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by cDNA synthesis. The relative gene expression analyses were performed by q-RT-PCR with an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 7 Flex real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized using Actin as internal housekeeping control.

Histology and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Rat traumatized tissue and uninjured control tissue samples were fixed in a 10% formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by sequential ethanol dehydration infiltrated with xylenes and embedded in paraffin as previously described6. Five-micron thick sections on glass slides from all tissues were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for histo-pathological evaluation. Sections were deparaffinized in xylenes, rehydrated using a graded series of ethanol, and stained with H&E staining following standard laboratory procedures. Histology preparation and H&E staining were mostly performed at the Histopathology Core Facility, Biomedical Instrumentation Center, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. A small subset of samples was processed and H&E stained at Histoserv, Inc. (Germantown, MD). Stained H&E slides were analyzed, scored (grade 0–5), and photographed in bright-field microscopy following standard procedures by Dr. Christopher W. Schellhase, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD.

Statistical analysis

Replicates from independent experiments are expressed as mean ± standard deviation values or as mean ± standard error values as indicated, and significance was calculated by one- or two-tailed Student’s t-tests as indicated. The Benjamini-Hochberg process was used to adjust the t-test p-values. Radiographic results were analyzed using a linear mixed model to determine the extent of HO formation as indicated. Histological sample categories that met the assumption of equal variances across the groups (tissue degeneration, loss of fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and multinucleated giant cells) were included in the ANOVA analysis as indicated. Additional histological sample categories of interest (HO formation, ossification, mineralization, acute inflammation, and tissue regeneration) failed the Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances and were not analyzed. One- or two-tailed Student’s t-tests were performed in Microsoft Excel. All additional analyses were performed in SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ACTA2:

-

Alpha 2 actin smooth muscle

- ACVR1:

-

Activin receptor IA

- ALK2:

-

Activin receptor-like kinase 2

- ALK5:

-

Activin receptor-like kinase 5

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- BGLAP:

-

Bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein

- Bmal1:

-

Brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1

- BMP:

-

Bone morphogenetic protein

- CDH2:

-

Cadherin 2

- COL1A1:

-

Collagen type I alpha 1 chain

- COL3A1:

-

Collagen type III alpha 1 chain

- CTGF:

-

Connective tissue growth factor

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FN1:

-

Fibronectin 1

- FOP:

-

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HBSS:

-

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HO:

-

Heterotopic ossification

- MMP2:

-

Matrix metallopeptidase 2

- MMP9:

-

Matrix metallopeptidase 9

- MPCs:

-

Primary mesenchymal progenitor cells

- MTT (assay):

-

(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (assay)

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PETN:

-

Pentaerythritol tetranitrate

- q-RT-PCR:

-

Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- RUNX2:

-

RUNX family transcription factor 2

- SERPINE1:

-

Serpin family E member 1

- SMAD2:

-

SMAD family member 2

- SMAD2-KD:

-

SMAD family member 2 knockdown

- SMAD3:

-

SMAD family member 3

- SMAD3-KD:

-

SMAD family member 3 knockdown

- TGFβ:

-

Transforming growth factor-β (beta)

- VIM:

-

Vimentin

References

Nauth, A. et al. Heterotopic ossification in orthopaedic trauma. J. Orthop. Trauma. 26 (12), 684–688 (2012).

Potter, B. K. et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations. Prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 89 (3), 476–486 (2007).

Uezumi, A. et al. Fibrosis and adipogenesis originate from a common mesenchymal progenitor in skeletal muscle. J. Cell. Sci. 124 (Pt 21), 3654–3664 (2011).

Wosczyna, M. N. et al. Multipotent progenitors resident in the skeletal muscle interstitium exhibit robust BMP-dependent osteogenic activity and mediate heterotopic ossification. J. Bone Min. Res. 27 (5), 1004–1017 (2012).

Uezumi, A. et al. Roles of nonmyogenic mesenchymal progenitors in pathogenesis and regeneration of skeletal muscle. Front. Physiol. 24, 5:68 (2014).

Jackson, W. M. et al. Cytokine expression in muscle following traumatic injury. J. Orthop. Res. 29 (10), 1613–1620 (2011).

Ji, Y. et al. Heterotopic ossification following musculoskeletal trauma: modeling stem and progenitor cells in their microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 720, 39–50 (2011).

Hu, H. H. et al. New insights into TGF-beta/Smad signaling in tissue fibrosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 25;292, 76–83 (2018).

Frangogiannis, N. Transforming growth factor-β in tissue fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 217 (3), e20190103 (2020).

Morikawa, M. et al. TGF-beta and the TGF-beta family: Context-Dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 8 (5), a021873 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Inhibition of overactive TGF-beta attenuates progression of heterotopic ossification in mice. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 551. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02988-5 (2018).

Ling Liu, X. L. et al. Smad2 and Smad3 have differential sensitivity in relaying TGFβ signaling and inversely regulate early lineage specification. Sci. Rep. 6, 21602. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21602 (2016).

Eric Aragón, Q. W. et al. Structural basis for distinct roles of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in FOXH1 pioneer-directed TGF-β signaling. Genes Dev. 33 (21–22), 1506–1524 (2019).

Phanish, M. K. et al. The differential role of Smad2 and Smad3 in the regulation of pro-fibrotic TGFbeta1 responses in human proximal-tubule epithelial cells. Biochem. J. 393 (Pt 2), 601–607 (2006).

de Vasconcellos, J. F. et al. In vivo model of human post-traumatic heterotopic ossification demonstrates early fibroproliferative signature. J. Transl Med. 17 (1), 248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1996-y (2019).

Xu, Q., Shrivastav, N. J., Lucio-Cazana, S. & Kopp, J. In vitro models of TGF-beta-induced fibrosis suitable for high-throughput screening of antifibrotic agents. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 293 (2), F631–640 (2007).