Abstract

Many controllers have been developed to control the motors of electric vehicles, but in the case of hydrogen vehicles, more delicate control is required, because power is provided through hybridization with batteries. The use of deep learning techniques enables optimization across various ranges based on extensive data to be more feasible. This study investigates the performance of three control strategies—PI control, Model Reference Adaptive Control, and Deep Learning-based MRAC—when applied to the motor of a hydrogen vehicle. The system of a hydrogen vehicle, including fuel cell systems, batteries, DC–DC converters, 3-phase inverters, and electric motors, was constructed and integrated to form a complete vehicle system. The performance of MRAC and DL-MRAC was compared based on step inputs of vehicle speed references, and the performance of PI control, MRAC, and DL-MRAC was evaluated under disturbances. Evaluations included considerations of the battery’s state of charge for fuel economy. Results indicate DL-MRAC exhibited the best fuel economy characteristics. While DL-MRAC’s current fuel economy advantage is slight, it is anticipated to improve with additional training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change evolves new vehicle trends such as the fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) and battery electric vehicle (BEV). The FCEVs has hydrogen storage to generate electricity by electrochemical reaction in hydrogen fuel cell. Among various type of fuel cells, a proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) is most suitable for vehicle application due to their low operating temperature with fast start-up, high efficiency and low noise with comfortability1,2,3. The FCEV also has small battery to cope with energy saving and sustainable durability under acceleration and deceleration. While those power sources drive the FCEV very clean without any harmful exhaust gases, the management strategies of power sources are different from single power source vehicle.

On the other hand, the conventional internal combustion engine vehicle can drive the car by mechanical power from fossil fuel combustion. But the FCEV uses the power generation system disconnected from traction of vehicles. That is, the hybrid power sources can provide electricity to the traction motor and the traction motor is finally driving the wheels. This disconnection of power sources from traction forces makes power management of FCEV more complicated than conventional internal combustion engine-based vehicles. Additionally, the power management of FCEV is more complicated than BEV due to hybrid power sources.

Even though power management strategy of FCEV is complicated, durable operation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell is beneficiary. When the rapid acceleration of PEMFC is detrimental for durability, intelligent operational strategy of PEMFC with battery extends the lifetime of PEMFC.

The power management of electrically driven vehicle is to meet requested power for driving the wheel by traction motor. The FCEVs utilize two power sources to achieve this goal. Different from internal combustion engine, two different control algorithms should be refined such as control of fuel cell and battery power generation and control of traction motor with the delivered electrical energy. As the two control algorithms are carried out delicately, the requested driving pattern is obtained. On the other hand, the control of power sources and traction motor should be investigated together so that the electrically driven vehicle achieve excellent fuel economy. A common power source structure was investigated with reference to many studies of fuel cell hybrid vehicles4,5,6,7.

Empirical data regarding fuel economy is naturally scarce, underscoring the increasing significance and effectiveness of fuel economy evaluations through simulation. The FCEVs make the performance of the motor crucial for vehicle fuel economy8,9,10,11,12. Currently, most electrically driven vehicle adopts permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM), which provides excellent efficiency and power density characteristics, employing precise vector control as the controller.

Vector control is a technique that transforms the three-phase motor currents into two-phase current components affecting flux and torque for interpretation and control purposes. Within vector control, Field-oriented control (FOC) consists of torque current controller for speed regulation, torque voltage controller for torque current regulation, and flux voltage controller for flux current regulation13,14. The torque current controller, which influences speed regulation, has the most direct impact on vehicle fuel economy, as its output, the torque current, is influenced by the torque voltage controller, thereby making the performance results of both controllers important for fuel economy15,16,17.

There are many studies dealing with the topic of motor controllers in fuel cell electric vehicles available in the literature. Dong et al. proposes an improved second-order super twisting sliding mode control (STSMC) strategy integrating BAS and GWO algorithms for the speed control of 40,000 RPM PMSM, enhancing system stability and robustness, and demonstrates its superiority through comparative analysis with various controllers18. Lee et al. develops a loss-minimizing control law for a PMSM by modeling inductances as functions of q-axis current based on experimental flux data, and using experimental power loss data to create a lookup table of loss-minimizing current sets for various d-axis currents, which is then utilized in the torque control loop to ensure high efficiency at all torque-speed operating points19. Hames et al. presents optimal hydrogen fuel cell vehicle configurations and control strategies for safety, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency by comparing existing control strategies in the literature for fuel economy, emphasizing the integration of fuel cells, batteries, supercapacitors, controllers, and smart control units that adjust parameters based on data from the traction motor and energy storage systems20. Williamson et al. models the efficiency maps of inverters and traction motors to analyze the drivetrain efficiency of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) and fuel cell vehicles (FCVs), using ADVISOR software to simulate large vehicles similar to the Chevy Lumina and commercially available HEVs like the Honda Insight and Toyota Prius across various driving cycles21. Yigit et al. integrates a fractional-order PI (FOPI) controller structure to control a Brushless DC (BLDC) motor powered by hydrogen technology, incorporating a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolyzer, PEMFC, storage tank, BLDC motor, and motor driver system within MATLAB Simulink environment22.

The papers mentioned above present achievements in achieving excellent motor performance through motor controllers in electric vehicles. However, most conventional controllers applied to motors have limitations compared to their respective advantages23,24,25. For instance, performance varies depending on the vehicle speed range, so optimization is achieved by tuning gains in each segment. This stems from the mathematical limitations inherent in logic-based controllers. Recently, leveraging deep learning techniques applied across various industries allows designing controllers based on data rather than logic26,27,28. By training on extensive data, controllers can perform optimized control tailored to each range29.

There are various research cases that apply machine learning or deep learning to FCEVs and BEVs. Kim et al. showed that an effective energy prediction algorithm through an energy management strategy (EMS) helps maintain the state of charge (SOC)30. Venkatasatish et al. analyzed hydrogen refueling station (HRS)-based production and storage systems, energy storage devices, energy management systems, and the applicability of reinforcement learning for fuel cell hybrid electric vehicles (FCHEVs), while discussing key technical challenges and potential solutions31. Karen et al. utilized fueling transaction data from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) to estimate the frequency of midday charging for U.S. federal fleet BEVs and applied machine learning models to analyze the BEV adoption potential for 112,902 federal fleet vehicles, integrating the results into the Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Planning and Charging (ZPAC) tool for infrastructure optimization32. Oladosu et al. analyzed AI-based algorithms, control systems, and energy management strategies for optimizing hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (HFCEV) performance, highlighting how multi-objective optimization, reinforcement learning algorithms, and hybrid techniques enhance HFCEV cost competitiveness33. The above studies have conducted research on FCEVs and BEVs and achieved results using AI techniques such as machine learning and deep learning. However, since they are not used for control or focus on some control elements such as power distribution, there are limitations as a method for controlling transient states.

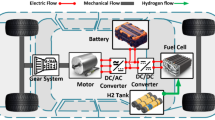

In this study, the performance characteristics of three control strategies were investigated: PI control, Model Reference Adaptive Control (MRAC), and Deep Learning MRAC (DL-MRAC)—by applying to a hydrogen vehicle motor. This study involved constructing the component system model of the hydrogen vehicle, including the fuel cell system, battery, DC–DC converter, 3-phase inverter, and electric motor. These models were integrated to form a complete vehicle system, with specifications either referenced from existing commercial hydrogen vehicles or designed based on them. This research compared the performance characteristics of MRAC and DL-MRAC using step inputs of vehicle speed references. Both MRAC and DL-MRAC were found to track the reference model’s output values, and their convergence speeds were evaluated to analyze each controller’s superiority. Further analysis is provided by comparing the performance of PI control, MRAC, and DL-MRAC under disturbance insertion while maintaining a constant vehicle speed reference. Factors such as undershoot after the disturbance, convergence speed, and oscillation were evaluated as criteria to assess each controller’s superiority in dealing with disturbances. One of the critical findings of the study was related to the vehicle’s fuel economy, which was evaluated through multiple simulations considering the battery’s SOC. DL-MRAC exhibited the best fuel efficiency characteristics among the three controllers, with fuel economy values ranking (19.903 for DL-MRAC, 19.896 for MRAC, and 19.872 for PI control).

Modelling approach

Vehicle model

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram and Simulink block of vehicle model designed in this study. In order to stably control the vehicle power system, the converter output voltage needs to follow the same as the battery voltage. The controller is designed so that the converter output voltage follows this value by sensing the battery voltage. When the amount of battery discharge current increases in the primary response to a step-shaped demand current input, the battery SOC decreases, resulting in a voltage as well. The voltage at the downstream end of the converter is controlled to be the same as the battery voltage, and at the same time, the converter duty ratio is fixed, so the converter input voltage must also be reduced at the same rate as the battery voltage changes. Taking this into consideration, the controller was designed to increase the fuel cell current. As the fuel cell current increases, the converter current also increases and the battery discharge rate gradually decreases. In some cases, the battery SOC stops decreasing and maintains a steady state, or the voltage may increase by switching to charging mode. When the voltage is increased, the fuel cell current is controlled to decrease so that the fuel cell voltage can also be increased. Accordingly, the downstream current of the converter is reduced, and thus the battery charging current is reduced to maintain a steady state in the end. Table 1 represents the detailed specifications of the vehicle.

Power supply system

The power supply system is one of the main components of FCEVs and provides the electrical energy necessary for the vehicle’s operation and propulsion. This system comprises fuel cells and batteries, each playing crucial roles that significantly impact the performance and efficiency of FCEVs. The power supply system maintains stable power delivery for FCEVs through the harmonious operation of fuel cells and batteries, ensuring environmentally friendly driving and exceptional performance.

Fuel cells are key devices that generate electrical energy through the chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen. The electrical energy produced from the combination of hydrogen and oxygen powers the motor directly or is stored in the battery when the motor demands energy beyond what the fuel cells can provide. This process generates only water as a byproduct, contributing to an eco-friendly driving by emitting no harmful substances into the atmosphere.

On the other hand, batteries store energy generated during driving and supply power as needed to support the vehicle’s electrical systems. High-performance lithium-ion batteries are predominantly used in vehicles, offering high energy density and long-term stable performance. During instances where rapid response or additional power beyond the fuel cells’ capabilities is required, such as during acceleration or high-speed driving, the battery supplements the motor with extra power, enhancing driving performance while maintaining energy efficiency. This dual function is crucial for enabling long-distance driving and sustaining optimal vehicle performance in hydrogen vehicles.

Power conversion system

The power conversion system plays a critical role in managing and controlling the delivery of electrical energy from the power supply system to the motor in an appropriate manner within the vehicle. This unit is primarily divided into two parts: the DC–DC converter and the inverter. The power conversion system plays a pivotal role in enhancing the efficiency and stability of FCEVs.

The DC–DC converter is responsible for converting the DC power output from sources such as fuel cells or batteries to different voltage levels required by various systems or devices within the vehicle. Especially, crucial is its role in aligning the disparate voltage outputs of batteries and fuel cells to maintain the stability of the voltage bus. This ensures overall system stability and efficient power utilization.

On the other hand, the inverter converts DC power into AC power, primarily to operate the motor. Since the power supplied from fuel cells or batteries is in DC form while the motor requires AC power, the presence of an inverter is indispensable. The inverter also plays a role in regulating the motor’s speed and torque, thereby enhancing the vehicle’s driving performance. For instance, precise control over motor rotation via the inverter enables swift adjustments for acceleration and deceleration, thereby improving driving stability.

Permanent magnet synchronous motor

The drivetrain of FCEVs is responsible for the actual propulsion of the vehicle and encompasses mechanical technologies and control systems primarily related to the motor. The motor converts electrical energy from the powertrain into mechanical motion to propel the vehicle. Efficient motor design and control play a crucial role in simultaneously enhancing vehicle performance and energy efficiency. By appropriately adjusting parameters such as wheel size, rotational speed, torque output, etc., the driving characteristics of the vehicle can be optimized.

The type of the motors primarily used in electric vehicles is PMSM, which has several merits such as high efficiency, high torque density, precise control, brushless structure, and high dynamic responsiveness. It, also, has minimal internal circuit losses, leading to high power conversion efficiency, and its tendency to generate high torque even in small sizes enhances system performance. Additionally, their brushless structure reduces maintenance needs and ensures quick responses to various driving conditions.

PMSM is controlled through inverters, receiving electrical energy to generate rotational motion. To effectively control modern motors used in electric vehicles, a method known as dq transformation, also called Park Clarke transformation, is predominantly employed. This method involves controlling 3-phase AC power in a way similar to handling DC power, enabling ease of motor control and high-performance management to enhance driving efficiency and stability. The dq transformation converts the motor’s 3-phase AC voltage/current into d-axis and q-axis components, allowing independent control of the motor’s rotational speed, torque, magnetic field, etc.

Controller

MRAC

A PID controller combines proportional control, integral control, and derivative control to regulate the dynamic characteristics of a system. It is widely used in many fields due to its relatively simple implementation and high stability. However, it does have some limitations. PID controllers are primarily designed for linear systems and, thus, when dealing with nonlinear systems or systems with changing parameters, the controlled system may not yield the output as desired. Changes in the external environment or uncertainties can affect PID controller performance; for instance, variations in motor loads or external interference can impact control performance. PID controllers struggle to handle such uncertainties and external factors effectively since they only consider the current state to adjust control inputs, making it difficult to adapt to dynamic system changes or uncertainties. Additionally, PID control requires manual gain adjustments for optimal control, which needs considerable time and effort. There are several heuristic methods that can easily tune the gain, but they are not as robust as adaptive control as a steady-state solution to disturbances.

On the other hand, MRAC is a control technique that can overcome these limitations. MRAC is designed to maintain desired performance or achieve optimal control even in uncertain systems or environments. Its structure consists of a model-reference controller that generates control inputs based on a model describing expected system behavior and an adaptive controller that adjusts control inputs in real-time using estimated model parameters as shown in Fig. 2. This allows MRAC to estimate the dynamic state of the system in real-time, adaptively adjust model parameters, and generate optimal control inputs. MRAC compensates for system uncertainties, providing higher control performance.

The use of MRAC in motor systems offers several advantages. Motors are sensitive to changes in the external environment, have substantial uncertainties, and exhibit dynamic variations in operation characteristics due to load changes or speed variations. MRAC can estimate system states in real-time, adjust model parameters to compensate for uncertainties, and quickly respond to dynamic environmental changes, ensuring stable operation across various environments. Moreover, MRAC, based on model-reference control, generates control inputs to track desired system behavior, ensuring optimal operation such as precise speed or position maintenance and control efficiency. Since this model parameter control is automatic, it minimizes user intervention, allowing for automated control and resource savings while maintaining system stability and consistent performance.

Figure 3 shows the basic test results of the MRAC developed in this model. The output of the plant without MRAC applied deviates significantly from the reference input value, but when MRAC is applied, the output converges to the reference input value. The convergence pattern matches the model reference values designed in this model. The degree of convergence of the output to the reference value varies depending on the adaptive constant b. Results for b values of 10, 100, and 1000 show that higher b values lead to faster convergence. Comparing the error values shown in Fig. 3b further clarifies the response characteristics depending on the b value.

Deep learning MRAC

MRAC provides robustness against disturbances; however, as seen in Fig. 3, it exhibits varying adaptation levels depending on the adaptive constant. Consequently, significant variations in the range of values before and after disturbances can result in notable differences in the controller’s performance. This implies that the motor control performance can vary depending on the acceleration of a vehicle’s motor.

To address such drawbacks, this study aims to utilize a neural model reference controller incorporating deep learning. The neural model reference controller used in this study is composed of a plant neural network model with time delays, as shown in Fig. 4, and a controller neural network model. The plant model is first identified, after which the controller is trained to ensure that the plant’s output follows the reference model’s output. This architecture can be examined through the neural network plant model and controller implemented in the Deep Learning Toolbox™. Each neural network consists of two layers, and the number of neurons in the hidden layer can be selected. The controller has three sets of input values: delayed reference inputs, delayed controller outputs, and delayed plant outputs. The number of delay values for each input can be adjusted, and generally, as the plant’s order increases, the number of delay values also increases. The neural network plant model has two sets of input values: delayed controller outputs and delayed plant outputs. Similar to the controller, the number of delay values can be configured for the plant model as well.

The plant neural network model is designed to mimic the actual behavior of the plant, while the controller neural network is designed to make the reference input track the model reference output. This designed model reference neural controller is then integrated with the conventional MRAC, forming what is termed as DL-MRAC.

Figure 5 represents the basic test results of the DL-MRAC designed in this study. The results show that when testing with a reference input ranging from 0 to 1, the output tracks the reference value well. However, when testing with a reference input ranging from 0 to 5, the output fails to track the reference input accurately. While there is a tendency for the output to increase as the reference input increases, beyond the range of 0–1, the output exhibits nonlinear behavior.

Therefore, in this study, it is aimed to use normalization as shown in Fig. 6. The model reference input r and plant output x were appropriately divided by their respective ranges to standardize them within the range of 0 and 1. The controller was then trained using these standardized values. After training, the output value u from the controller was reverse-standardized to be inputted into the plant. After applying normalization, It is confirmed that the output tracks the reference value well even after inputting references outside the range of 0–1.

Results and discussion

PI control, MRAC, and DL-MRAC were applied to control the motor of a hydrogen vehicle model, and evaluated the performance of each controller by comparing responsiveness and fuel efficiency results. PI control is a classical control method where angular velocity is input to generate torque current, which in turn controls torque voltage to regulate the motor. In contrast, DL-MRAC controls the motor by receiving input of reference angular velocity and actual angular velocity to adjust torque voltage. Figure 7 represents the block diagram of the portion replaced by the PI controller for DL-MRAC.

Speed response

In this study, reference speed profiles of 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 km/h were applied to observe the response characteristics of each controller. The reference models for MRAC and DL-MRAC were designed to track the time-delayed values of speed input using transfer functions. Since PI control does not have a reference model, it was omitted from observing speed responsiveness.

Figure 8 shows the results of speed response observation tests for MRAC and DL-MRAC. Observing the relatively low-speed transition in Fig. 8a, MRAC yields a slow tracking result of the model reference value with relatively high overshoot. In contrast, DL-MRAC initially tracked the model reference value quickly but transitioned to slower tracking midway. This demonstrates DL-MRAC’s relatively faster response at the beginning of step inputs.

As the speed reference increased to 10, 20, and 30 km/h, the response characteristics showed better tracking of the model reference. Compared to the 5 km/h speed reference, MRAC exhibited more accurate tracking at intermediate speed references than DL-MRAC. However, in the relative high-speed transition shown in Fig. 8e, MRAC appeared highly unstable, highlighting its instability due to a single adaptive constant that does not carry over characteristics from low and intermediate speeds to high speeds. In contrast, DL-MRAC showed a relatively stable tracking of the model reference despite exhibiting significant overshoot due to its rapid initial response to step inputs, implying its stability in high-speed transitions.

Disturbance

Vehicles encounter various disturbances during operation, and effectively overcoming these disturbances is a crucial factor for vehicle performance. Different types of disturbances involve variations in motor torque, which manifests as changes in motor rotation speed. Vehicle dynamics are one of the direct influencing factors on the vehicle motor, with factors such as speed, weight, and terrain conditions predominantly influencing it. In the proposed truck model in this study, the vehicle’s weight and terrain material are not easily affected by operational disturbances, which is not a common occurrence. However, among the four resistance factors in vehicle dynamics, rolling resistance is a phenomenon easily encountered during vehicle operation, especially when the terrain gradient is introduced as a disturbance, allowing for the testing of disturbance effects during regular driving conditions. Therefore, in this study, it is aimed to assess the motor response performance when facing a 30-degree incline at a fixed speed.

Figure 9 illustrates the performance of each controller in response to disturbances encountered at speeds of 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 km/h. In the case where PI control is used, it generally shows smaller undershoots in motor angular velocity compared to other controllers, but it suffers from abrupt oscillations and slower return to nominal speeds compared to other controllers. Among the three controllers, MRAC shows the most pronounced undershoot behavior, although the difference compared to DL-MRAC is not substantial. When comparing the disturbance performance of MRAC and DL-MRAC, they exhibit generally similar performance, but some differences are observed depending on the motor reference speed. At low speeds of 5 and 10 km/h, DL-MRAC converges to a steady state faster than MRAC. However, at 10 km/h, DL-MRAC’s convergence slows down, leading to a reversal in convergence speed compared to MRAC at around 1.2 s. At speed references of 20 and 30 km/h, both MRAC and DL-MRAC exhibit visible oscillations. The oscillations are more pronounced in DL-MRAC than in MRAC, and MRAC shows a faster convergence speed. At a speed reference of 40 km/h, DL-MRAC exhibits an undershoot of about 4, significantly reducing compared to other speed references, but the oscillations increase substantially. MRAC, on the other hand, shows a significant increase in oscillations, indicating a highly unstable behavior, especially at high speeds when facing disturbances.

Fuel economy

Hydrogen vehicle batteries have distinct characteristics, with different initial SOC and final SOC after a driving cycle. This makes it challenging to assess the fuel economy of hydrogen vehicles using a single drive cycle dataset. In order to enable such assessments, it’s necessary to convert the SOC difference between the initial and final SOC into hydrogen consumption or potential driving range. Developing protocols that define how the battery should be charged or discharged based on the difference of SOC is a highly complex task.

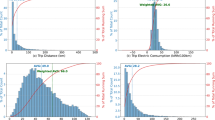

In this study, fuel economy simulation was conducted based on the SAE-J2572 protocol, a document that outlines the protocol for evaluating hydrogen vehicle fuel economy34. This document proposes a method for estimating fuel economy when the initial and final SOC are not same, based on multiple drive cycles. In this research, the SOC and hydrogen consumption data were collected during the simulation starting at the various initial SOC values ranging from 10 to 90% at 10% intervals. Figure 10 shows the WHVC mode driving profile used to acquire fuel economy data in this study.

Table 2; Fig. 11, respectively, present the data acquired in this fuel economy evaluation and the results. The points for fuel economy versus the difference between the initial and final SOC are depicted as scatter plots, and a first order polynomial curve fitting is performed on these data points. In this curve fitting, the point where the initial and final SOC difference is zero is assumed to represent the fuel economy under each condition. The measured fuel economies for PI, MRAC, and DL-MRAC are 19.872, 19.896, and 19.903 km/kg, respectively. The ranking of fuel economy is as follows: DL-MRAC, MRAC, and PI (highest to lowest).

Conclusion

In this study, the performance characteristics of PI control, MRAC, and Deep Learning MRAC is investigated when applied to a hydrogen vehicle motor.

-

1.

The component systems of the hydrogen vehicle were constructed, which included the fuel cell system, battery, DC–DC converter, 3-phase inverter, and electric motor. All of these models were integrated into a complete vehicle system.

-

2.

The specifications of the vehicle system were either referenced from or designed based on existing commercial hydrogen vehicles.

-

3.

The performance characteristics of MRAC and DL-MRAC were compared based on step inputs of vehicle speed references. It was confirmed that both MRAC and DL-MRAC output values track the reference model, and the convergence speed was evaluated as a criterion to analyze the superiority of each controller.

-

4.

The performance characteristics of PI control, MRAC, and DL-MRAC were compared by inserting disturbances while maintaining a constant vehicle speed reference. Under the conditions of disturbance insertion, factors such as undershoot immediately after the disturbance, convergence speed, and oscillation were evaluated as criteria to analyze the superiority of each controller.

-

5.

The vehicle’s fuel economy was evaluated through multiple simulations, with the fuel economy value calculated while considering the battery’s SOC. The fuel economy of DL-MRAC, MRAC, and PI control was observed to be superior in the following order: 19.903 for DL-MRAC, 19.896 for MRAC, and 19.872 for PI control.

-

6.

DL-MRAC demonstrated superiority at certain speed references and showed the best fuel efficiency characteristics. This was due to its basis in data training rather than mathematical or analytical logic, leading to limitations in analytically inferring the causes of control phenomena. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the potential to overcome the drawbacks of conventional MRAC through appropriate training based on the derived results was confirmed. Currently, the fuel efficiency characteristic of DL-MRAC is marginally superior, but it is believed that with appropriate training, its fuel efficiency superiority will further increase.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, J. et al. Remaining useful life prediction of vehicle-oriented PEMFC systems based on IGWO-BP neural network under real-world traffic conditions. Energy 291, 130334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.130334 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Empirical lifetime prediction through deterioration evaluation of high-power PEMFC for railway vehicle applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 71, 972–981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.05.185 (2024).

Meng, H., Yu, X., Luo, X. & Tu, Z. Modelling and operation characteristics of air-cooled PEMFC with metallic bipolar plate used in unmanned aerial vehicle. Energy 300, 131559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.131559 (2024).

Saravanan, R., Sobhana, O., Lakshmanan, M. & Arulkumar, P. Fuel cell electric vehicles equipped with energy storage system for energy management: A hybrid JS-RSA approach. J. Energy Storage https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.108646 (2023).

Waseem, M., Amir, M., Lakshmi, G. S., Harivardhagini, S. & Ahmad, M. Fuel cell-based hybrid electric vehicles: an integrated review of current status, key challenges, recommended policies, and future prospects. Green. Energy Intell. Transp. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geits.2023.100121 (2023).

Badji, A., Abdeslam, D. O., Chabane, D. & Benamrouche, N. Real-time implementation of improved power frequency approach based energy management of fuel cell electric vehicle considering storage limitations. Energy 249, 123743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123743 (2022).

Han, R., He, H., Zhang, Z., Quan, S. & Chen, J. A multi-objective hierarchical energy management strategy for a distributed fuel-cell hybrid electric tracked vehicle. J. Energy Stor. 76, 109858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.109858 (2024).

Kim, D. M., Kwon, K., Cha, K. S., Min, S. & Lim, M. S. Deep neural network-based modeling and optimization methodology of fuel cell electric vehicles considering power sources and electric motors. J. Power Sources. 603, 234401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.234401 (2024).

Lawrence, C. P., ElShatshat, R., Salama, M. M. A. & Fraser, R. A. An efficient auxiliary system controller for fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV). Energy 116, 417–428 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.09.131

Wang, D. et al. Energy management strategy with mutation protection for fuel cell electric vehicles. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 63, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.03.025 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Energy management strategy for fuel cell electric vehicles based on scalable reinforcement learning in novel environment. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 59, 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.01.335 (2024).

Giuseppe, D. P. et al. Fuel cell electric vehicle characterisation under laboratory and In-use operation. Energy Rep. 11, 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.12.013 (2024).

Alvaro, P. M., Aitor, S. A., Fernando, M. & Javier, V. FOC-Droop control strategy for PMSM fed paralleled multi-inverter power systems oriented to aeronautical applications. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 185, 106369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2020.106369 (2020).

Ramesh, P., Umavathi, M., Bharatiraja, C., Ramanathan, G. & Athikkal, S. Development of a PMSM motor field-oriented control algorithm for electrical vehicles. Mater. Today: Proc. 65, 176–187 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.06.080

Dalal, Z., Youcef, B. & Habib, B. Field-oriented control based on parallel proportional-integral controllers of induction motor drive. Energy Rep. 9, 4846–4860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.04.008 (2023).

Chen, K. Y., Hu, J. S., Tang, C. H. & Shen, T. Y. A novel switching strategy for FOC motor drive using multi-dimensional feedback quantization. Control Eng. Pract. 20, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2011.10.013 (2012).

Chi, X. et al. A ripple suppression of sensorless FOC of PMSM electrical drive system based on MRAS. Results Eng.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101427 (2023).

Dong, L. & Jiang, P. Improved super-twisting sliding mode control strategy in permanent magnet wynchronous motors for hydrogen fuel cell centrifugal compressor. Heliyon 10, e24181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24181 (2024).

Lee, J., Nam, K., Choi, S. & Kwon, S. A. Lookup Table based loss minimizing control for FCEV permanent magnet synchronous motors. IEEE Veh. Power Propuls. Conf. https://doi.org/10.1109/VPPC.2007.4544120 (2007).

Hames, Y., Kaya, K., Baltacioglu, E. & Turksoy, A. Analysis of the control strategies for fuel saving in the hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 43, 10810–10821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.12.150 (2018).

Williamson, S., Lukic, M. & Emadi, A. Comprehensive drive train efficiency analysis of hybrid electric and fuel cell vehicles based on motor-controller efficiency modeling. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 21, 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2006.872388 (2006).

Yigit, T. & Celik, H. Speed controlling of the PEM fuel cell powered BLDC motor with FOPI optimized by MSA. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 35097–35107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.04.091 (2020).

Mopidevi, S. et al. Design, control and performance comparison of PI and ANFIS controllers for BLDC motor Dirven electric vehicles. Measurement: Sens. 31, 101001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measen.2023.101001 (2024).

Lu, S. & Jingzhuo, S. Adaptive PI control of ultrasonic motor using iterative learning methods. ISA Trans. 139, 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2023.03.032 (2023).

Li, H., Song, B., Chen, T., Xie, Y. & Zhou, X. Adaptive fuzzy PI controller for permanent magnet synchronous motor drive based on predictive functional control. J. Frankl. Inst. 358, 7333–7364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfranklin.2021.07.024 (2021).

Said, M. et al. Higher performance enhancement of direct torque control by using artificial neural networks for doubly fed induction motor. e-Prime – Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy. 8, 100537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2024.100537 (2024).

Yang, W. et al. An improved neural networks-based vector control approach for permanent magnet linear synchronous motor. J. Frankl. Inst. 361, 106565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfranklin.2023.12.026 (2024).

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Yao, S., Qu, C. & Wang, H. Adaptive backstepping control of primary permanent magnet linear motor via radial basis function neural network and command filter. Comput. Electr. Eng. 109, 108774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108774 (2023).

Su, X., Yang, X. & Xu, Y. Adaptive parameter learning and neural network control for uncertain permanent magnet linear synchronous motors. J. Frankl. Inst. 360, 11665–11682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfranklin.2023.09.016 (2023).

Kim, T. H., Cho, J. H., Kim, Y. & Chang, J. H. Deep-learning-based prediction algorithm for fuel-cell electric vehicle energy with shift mixup. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 14529–14538. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3373078 (2024).

Venkatasatish, R. & Dhanamjayulu, C. Reinforcement learning based energy management systems and hydrogen refuelling stations for fuel cell electric vehicles: An overview. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 27646–27670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.06.088 (2022).

Karen, F., Mark, S. & Cabell, H. Predicting & U.S. Federal fleet electric vehicle charging patterns using internal combustion engine vehicle fueling transaction statistics. Appl. Energy. 378, 124778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124778 (2025).

Oladosu, T. L., Pasupuleti, J., Kiong, T. S., Koh, S. P. J. & Yusaf, T. Energy management strategies, control systems, and artificial intelligence-based algorithms development for hydrogen fuel cell-powered vehicles: A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 61, 1380–1404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.02.284 (2024).

International, S. A. E. Recommended practice for measuring fuel consumption and range of fuel cell and hybrid fuel cell vehicles fueled by compressed gasesous hydrogen. SAE J2572, 1–13 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning(KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy(MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20213030030210), and supported by Korea Research Institute for defense Technology planning and advancement(KRIT) grant funded by the Korea government(DAPA(Defense Acquisition Program Administration)) (No. KRIT-CT-22-035, Optimized Design of Unmmaned Turret and Analysis Technology of Protective Structure of Capsule Crew Romm, 2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y. and J.H.; methodology, S.Y. and S.S.Y.; software, S.Y. and J.H.; formal analysis, S.Y. and S.S.Y.; investigation, J.H. and S.S.Y; writing-original draft preparation, J.H.; writing-review and editing, S.Y. and S.S.Y.; supervision, S.Y. and S.S.Y.; project administration, S.S.Y.; funding acquisition, S.S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, J., Yi, S. & Yu, S. Assessment of hydrogen vehicle fuel economy using MRAC based on deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 13085 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97082-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97082-4