Abstract

Pterygium is a prevalent ocular disease characterized by abnormal conjunctival tissue proliferation, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms driving pterygium pathogenesis remain inadequately understood. This study aimed to investigate gene expression changes following pterygium excision and their association with immune cell infiltration. Clinical samples of pterygium and adjacent relaxed conjunctival tissue were collected for transcriptomic analysis using RNA sequencing combined with bioinformatics approaches. Machine learning algorithms, including LASSO, SVM-RFE, and Random Forest, were employed to identify potential diagnostic biomarkers. GO, KEGG, GSEA, and GSVA were utilized for enrichment analysis. Single-sample GSEA was employed to analyze immune infiltration. The GSE2513 and GSE51995 datasets from the GEO database, along with clinical samples, were selected for validation analysis. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified from the PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 datasets, revealing 2437 DEGs and 172 differentially regulated genes (DRGs), respectively. There were 52 co-DEGs shared by both datasets, and four candidate biomarkers (FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13, EGR2) with potential diagnostic value were identified through machine learning algorithms. Single-sample GSEA demonstrated increased Th2 cell infiltration and decreased CD8 + T cell presence in pterygium tissues, suggesting a crucial role of the immune microenvironment in pterygium pathogenesis. Analysis of the GSE51995 dataset and qPCR results revealed significantly higher expression levels of FN1 and SPRR1B in pterygium tissues compared to conjunctival tissues, but SERPINB13 and EGR2 expression levels were not statistically significant. Furthermore, we identified four candidate drugs targeting the two feature genes FN1 and SPRR1B. This study provides valuable insights into the molecular characteristics and immune microenvironment of pterygium. The identification of potential biomarkers FN1 and SPRR1B highlights their significance in pterygium pathogenesis and lays a foundation for further exploration aimed at integrating these findings into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pterygium, a prevalent corneal conjunctival disease in subtropical and tropical regions with a global publication rate of approximately 12%, is characterized by the proliferation of conjunctival epithelial cells and fascial fibrovascular tissue invading the cornea1,2,3. Extensive research has demonstrated significant associations between pterygium occurrence and development and factors such as long-term UV exposure, exposure to environmental pollutants (including dust, PM2.5, PM10, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide), dry air, geographical location and genetic predispositions4,5,6. Pterygium often leads to ocular discomfort and blurred vision, significantly impacting patient’s quality of life and exhibiting a high recurrence rate, which poses additional economic burdens on patients and healthcare systems7,8. Current treatment primarily involves surgical excision. However, postoperative challenges such as recurrence, dry eye, irreversible corneal astigmatism and corneal scarring remain significant clinical obstacles9,10. These limitations highlight the urgent need for novel biomarkers and therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes and reduce morbidity. Despite its common occurrence, the underlying molecular mechanisms driving pterygium pathogenesis are inadequately understood. Prior studies have suggested a close relationship between pterygium development and factors like inflammatory responses, cellular proliferation and immune dysfunction7,11. However, comprehensive investigations elucidating the molecular characteristics of pterygium and the immune microenvironment are still limited12. A deeper understanding of these molecular features and the identification of key genes involved in pterygium pathogenesis could provide new insights into potential preventative and therapeutic approaches.

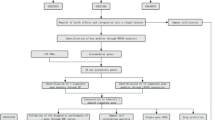

In this study, we aim to explore transcriptomic alterations following pterygium excision and their correlation with immune cell infiltration. Pterygium tissue serves as the experimental group, with adjacent relaxed conjunctival tissue acting as a control. By employing transcriptomic sequencing methods, we analyze gene expression changes and characterize the immune landscape associated with pterygium. This approach combines both our clinical samples and publicly available datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and their functional enrichment. Additionally, machine learning algorithms are utilized to screen for candidate biomarkers, enabling a robust evaluation of gene expression alterations. The integration of these methodologies is anticipated to provide a comprehensive assessment of the molecular underpinnings of pterygium. Our research objectives are to identify potential biomarkers associated with pterygium and to conduct immune infiltration analysis on our dataset. Through profiling the immune microenvironment, we aim to elucidate the role of immune cell subpopulations in pterygium progression, offering novel insights into its diagnosis. Investigating these molecular dynamics is crucial for enhancing our understanding of pterygium pathogenesis. Figure 1 depicts our research protocol.

In summary, exploring gene expression changes and immune cell infiltration in pterygium constitutes a significant step towards elucidating its complex biological landscape. By integrating transcriptomic analyses and machine learning approaches, this study aspires to uncover the molecular characteristics and immune interactions contributing to pterygium development and recurrence, paving the way for innovative diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Materials and methods

Datasets acquisition

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University (approval number: 2022198), and all study participants provided written informed consent. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study used pterygium tissue specimens collected using a non-random method, without blinding. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Patients with primary nasal pterygium tissue that had invaded the cornea and a disease duration of over six months; (2) Patients presenting with evident symptoms of congestion and eye irritation necessitating surgical intervention; (3) Patients with no prior history of other ocular diseases or surgeries; (4) Patients who were fully informed and provided consent for the examination of their pterygium tissue. During the surgical procedure, both pterygium tissue and normal conjunctival tissue were harvested for RNA extraction and subsequent sequencing analysis.

All surgical procedures were performed under local anesthesia by the same surgeon. The cohort comprised thirty-four patients undergoing elective pterygium surgery, with a gender distribution of 5 males and 29 females. The mean age was 56.8 years, and the average duration of illness was 4.19 years. Based on literature reports13, pterygium is divided into three levels. Our study includes 5 cases of Grade 1 pterygium, 18 cases of Grade 2 pterygium, and 11 cases of Grade 3 pterygium. During the operation, the diseased pterygium tissue was excised, along with the excess loose conjunctiva surrounding the pterygium. The experimental design mainly focused on the “pterygium tissue sample” and its “corresponding normal conjunctiva of adjacent tissues”. This control design was designed to minimize the possible impact of background individual differences, allowing for a greater focus on differences in the molecular characteristics of tumors and adjacent tissues. Total RNA extracted from pterygium and bulbar conjunctiva samples was assessed for integrity using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer, rRNA was removed from total RNA to obtain sample mRNA, which was then randomly fragmented using divalent cations in NEB Fragmentation Buffer. This was followed by chain-specific fragmentation for mRNA construction. Library quantification was initially performed using a Qubit2.0 Fluorometer, after which the library was diluted to 1.5ng/ul. The insert size of the library was measured using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer, and QRT-PCR was employed for precise quantification of the library’s effective concentration, which was required to be higher than 2nM. Following genomic DNA quality inspection, the DNA was fragmented via mechanical interruption (ultrasound). The fragmented DNA was then purified, end-repaired, 3′ end adenylated, ligated to a sequencing adapter, and size-selected using agarose gel electrophoresis. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was amplified to create the sequencing library. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, with a read length of 150 bp. The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession number: PRJNA1147595,URL: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1147595?reviewer=3k3nnr66jke53qo77la1sbt91b). Additional datasets are available in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (accession numbers: GSE2513 and GSE51995, URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). GSE2513 comprises four conjunctival samples and eight pairs of pterygium and control conjunctival samples14. GSE51995 includes four conjunctival samples and four pairs of pterygium and control conjunctival samples15.

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and functional analysis

The xiantao tool (https://www.xiantao.love/) is a valuable bioinformatics analysis web tool utilized for visualization. DEGs in PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 were identified using R programming, meeting the criteria of p ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 (conjunctiva vs. pterygium). The final determination of DEGs involved a Benjamini–Hochberg FDR (false discovery rate) multiple testing correction, with a p value analysis to correct false-positive results, where p ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 served as the threshold. Heat maps and volcano maps were generated to visualize the DEGs. Both datasets were normalized, and a cross-comparable evaluation was visualized using boxplots. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted on all genes (previously ranked based on their log2FC between analyzed groups) using the cluster profiler package. Enrichment was considered significant if the nominal false discovery rate (FDR) was < 0.25 and the P-value was < 0.05, referencing the ‘c2.cp.all.v2022.1.Hs.symbols.gmt’ gene set. By utilizing the gene set variation analysis (GSVA) package and referencing the ‘h.all.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt’ gene set16, the gene expression matrix data were subjected to GSVA. Differential pathways were filtered based on an p value < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 0.2.

Gene ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis

The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Functional Annotation Tool (accessible at https://david.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp) was utilized to conduct GO term and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on the common differentially expressed genes (co-DEGs)17,18. The R language package was employed to execute and visualize the enrichment analysis outcomes, applying thresholds of p value < 0.05 and a minimum enrichment gene count of 2. Both a bar graph and a bubble plot were generated for representation.

Identification of candidate diagnostic biomarkers by three machine-learning algorithms

Three distinct machine-learning algorithms, namely least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) logistic regression, support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE), and random forests (RF), were employed to identify potential novel biomarkers for pterygium19,20. The machine learning models RF (Random Forest) and SVM (Support Vector Machine) were trained with a random seed set to 2024, and the random processes were automatically generated using R project. Furthermore, the random forest method was executed using the ‘random Forest’ R package in R. LASSO logistic regression analysis was conducted using the ‘glmnet’ R package, with the minimum lambda value being considered optimal. The ‘e1071’ R package was utilized for SVM-RFE, and it was also used to split the data into train and test sets with a ratio of 80:20, incorporating 10-fold cross-validation. The partial likelihood deviation was maintained below 5%, and parameter selection for optimization was cross-verified by a factor of 10. Subsequently, the genes that exhibited characteristics consistent with all three aforementioned classification schemes were selected for further investigation. Specifically, the top 15 genes sharing these characteristics were chosen for deeper exploration.

Verification of candidate diagnostic biomarkers

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the hub genes were plotted using the R program. The area under the curve (AUC) of the corresponding ROC curves of the hub genes was used to assess the discriminative effects between pterygium tissues and conjunctiva tissues.

Infiltration analysis of immune cells and functions

The infiltrating scores of 24 immune cell types in the conjunctiva and pterygium groups were calculated using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) via the ‘gsva’ R package and visualized through a heatmap generated by the ‘Complex Heatmap’ package in the PRJNA1147595 dataset21. Point plots were utilized to compare and visualize the ssGSEA scores of infiltrated immune cells between the conjunctiva and pterygium samples, employing the ‘ggplot2’ R package. Additionally, a correlation heatmap was created using the ‘ggplot2’ R package to reveal the relationships among the 24 types of immune cells. To identify hub genes with diagnostic potential, we analyzed the correlation between four hub genes and immune cells using Spearman’s correlation analysis via the ‘ggplot2’ R package.

Histology analysis

The morphology of conjunctiva and pterygium tissues was observed using haematoxylin staining, masson’s trichrome staining, and vimentin immunohistochemical methods. Conjunctival and pterygium samples were collected from patients undergoing surgery, with informed consent and ethical approval obtained. The samples were immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 48 h and then embedded in paraffin. The fixed tissues were processed through a graded series of alcohols (70%, 80%, 95%, and 100% ethanol) for dehydration, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. The paraffin blocks were cut into 5 μm thick sections using a microtome. For HE staining, the sections were deparaffinized by immersing them in xylene for 5 min, repeated twice, and then rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (100%, 95%, 80%, 70%) for 5 min each, followed by distilled water. The sections were stained with Harris’ hematoxylin for 5 min to visualize the nuclei, rinsed under running tap water for 5 min, differentiated with 1% acid alcohol for a few seconds, rinsed again, and then blued with 0.6% ammonia water or Scott’s tap water substitute for 2 min. The sections were counterstained with eosin Y for 2 min to visualize the cytoplasm. For Masson’s trichrome staining, the same steps were followed as for HE staining, with the exception of staining the sections with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin for 5 min to visualize the nuclei and collagen, differentiating with acid alcohol, bluing with lithium carbonate or weak ammonia water, staining with Masson’s trichrome solution for 5 min, differentiating with 1% phosphotungstic acid or 2% acetic acid, and counterstaining with aniline blue for 5 min to enhance collagen visualization. For vimentin immunohistochemical staining, the same steps were followed as for HE staining, with additional steps of heat-induced antigen retrieval, blocking endogenous peroxidase activity, applying a protein blocking solution, applying the primary antibody against vimentin at an appropriate dilution, incubating, rinsing, applying a biotinylated secondary antibody or a polymer-based detection system, incubating again, and finally examining the stained sections under a light microscope to assess the morphology and vimentin expression pattern.

Quantitative real time PCR

Human conjunctival and pterygium tissues were homogenized and lysed using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher) in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from these tissues utilizing a total RNA extraction kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Following this, cDNA was synthesized via reverse transcription using a cDNA first strand reverse transcription synthesis kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). RT-qPCR was conducted to assess the expression levels of four genes: FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13 and EGR2, employing TB Green Fast qPCR Mix (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). Gene expression was quantified relative to GAPDH using the 2 − ΔΔCt method.

Identification of potential drug candidates

The important potential drug candidates were identified with the aid of the DSigDB database. Access to both the DSigDB databases was granted via the Enrichr platform (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.2.1) and SPSS (version 23.0). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). The student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze continuous variables with or without normal distribution, respectively. Categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentages) and analyzed using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Identification of DEGs

Using the R tool with criteria of p ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1, we identified 2437 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the PRJNA1147595 dataset and 172 differentially regulated genes (DRGs) in the GSE2513 dataset. Subsequently, cluster analysis was performed on these DEGs. The top 20 up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs in the PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 datasets were prioritized, respectively. Volcano plots and heat maps were generated based on the cluster analysis of PRJNA1147595 (Fig. 2A, C) and GSE2513 (Fig. 2B, D). The heat maps demonstrated high confidence in sample clustering. After normalization and cross-comparable evaluation (Fig. 2E for PRJNA1147595 dataset and Fig. 2F for GSE2513), it was evident that the data distribution of both sample sets met the standard criteria, indicating high quality and cross-comparability of the microarray data.

The volcano plots and heat maps of PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 datasets. (A) The volcano plot illustrates the PRJNA1147595 dataset, where the x-axis represents log2 (Fold Change) and the y-axis represents -log10 (p-value). Red dots signify up-regulated genes, while blue dots indicate down-regulated genes. (B) The volcano plot displays the GSE2513 dataset. (C) The heat map shows the PRJNA1147595 dataset, with each line representing a gene and each column a sample. Red color denotes a high-expression level, and blue color indicates a low-expression level. (D) The heat map represents the GSE2513 dataset. (E) This depicts the cross-comparability evaluation of the PRJNA1147595 dataset. (F) The cross-comparability evaluation of the GSE2513 dataset is shown.

GSEA and GSVA analysis

Our reference gene set was ‘c2.cp.all.v2022.1.Hs.symbols.gmt’. Both datasets underwent GSEA enrichment analysis to identify significant enrichment based on the criteria of FDR < 0.25 and P < 0.05. The GSEA analysis revealed significant enrichment in upregulated pathways, including PID_INTEGRIN1_PATHWAY and MET_ACTIVATES_PTK2_SIGNALING, in both datasets (Fig. 3A-D). Additionally, it showed significant enrichment in downregulated pathways, such as PID_MAPK_TRK_PATHWAY and FCERI_MEDIATED_MAPK_ACTIVATION, among others. GSVA enrichment analysis was conducted on the PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 datasets, revealing distinct pathways. The differential pathways in the PRJNA1147595 dataset encompassed HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB, HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION, HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1, HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION, and HALLMARK_ANGIOGENESIS, among others (Fig. 3E). These outcomes aligned with those of the GSE2513 dataset’s GSVA differential pathways, specifically HALLMARK_ANGIOGENESIS and HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB (Fig. 3F).

GSEA, GSVA, bubble plots of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results. (A-B) Analysis of upregulated pathways of differential genes in the PRJNA1147595 dataset. (C-D) Analysis of upregulated pathways of differential genes in the GSE2513 dataset. (E) Identification of differentially enriched pathways in the PRJNA1147595 dataset. (F) Identification of differentially enriched pathways in the GSE2513 dataset. (G) Venn diagram illustrating common Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in both the PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 datasets. (H) Bubble plots visualize the Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis results of common DEGs (co-DEGs). The varying depths of node colors represent different adjusted p-values, while the different sizes of the nodes indicate the varying number of genes. (I) Bubble plots visualize the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis results of common DEGs (co-DEGs).

Enrichment analysis of DEGs

A Venn diagram was created to illustrate the common DEGs between the two datasets (Fig. 3G). There were 52 co-DEGs shared by both datasets. GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were conducted to assess the function of these 52 co-DEGs (Fig. 3G). The GO terms were categorized into BP (biological process), CC (cellular component), and MF (molecular function). The top 6 BP, 2 CC, and 4 MF terms with the lowest p-values in each category were selected and visualized using bubble plots (Fig. 3H). The co-DEGs were primarily enriched in GO terms such as ‘peptide cross-linking’, ‘cellular response to metal ion’, ‘response to extracellular stimulus’, ‘skeletal muscle organ development’, ‘ERK1 and ERK2 cascade’, and ‘response to metal ion’. They were also enriched in CC terms like ‘collagen-containing extracellular matrix’ and ‘intrinsic component of the external side of the plasma membrane’. Additionally, the co-DEGs were enriched in MF terms including ‘extracellular matrix structural constituent’, ‘DNA-binding transcription activator activity, RNA polymerase II-specific’, ‘DNA-binding transcription activator activity’, and ‘peptidase regulator activity’. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 12 pathways with lower p-values, which were visualized using bubble plots (Fig. 3I). The co-DEGs were mainly enriched in KEGG pathways such as ‘Estrogen signaling pathway’, ‘IL-17 signaling pathway’, ‘Vascular smooth muscle contraction’, ‘C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway’, ‘GnRH signaling pathway’, ‘Toll-like receptor signaling pathway’, ‘TNF signaling pathway’, ‘Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis’, and ‘Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes’, among others22,23,24.

Selection of candidate diagnostic biomarkers using machine learning

Among the 52 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), LASSO regression analysis pinpointed 15 genes with the minimal binomial deviation (Fig. 4A-B). Subsequently, the random forest approach ranked the DEGs by gene significance score and selected 15 candidates (Fig. 4C-D). For pterygium, the SVM-RFE method, after 10-fold validation, identified 15 genes with the lowest error rate and highest accuracy (Fig. 4E). Ultimately, a Venn diagram illustrated the overlap of FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13, and EGR2 as DEGs when the three methodologies were employed concomitantly (Fig. 4F).

Selection of candidate diagnostic biomarkers of pterygium with machine learning approaches. (A-B) LASSO regression analysis was employed to identify diagnostic biomarkers. (C) Diagnostic errors associated with the conjunctiva, pterygium, and total groups were visualized using the random forest model. (D) A column displaying the top 15 DEGs ranked according to their importance scores derived from the random forest analysis. (E) The DEGs with the lowest error rate and highest accuracy after 10-fold cross-validation were selected as the most suitable candidates through the SVM-RFE algorithm. (F) The intersection of the results from the three machine learning algorithms was illustrated using a Venn diagram tool.

Prognostic value of the candidate diagnostic biomarkers

PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 were utilized as validation datasets. The ROC curves for the four hub genes were plotted based on their expression levels in both datasets to assess the discriminative effect on pterygium versus pairs conjunctiva (Fig. 5A-H).

Infiltration analysis of immune cells and 4 features genes relationship

To further investigate the infiltration and functional differences of immune cells between the conjunctiva and pterygium groups, we assessed the enrichment scores of distinct immune cell subpopulations using ssGSEA. The results were visualized through a heatmap (Fig. 6A) and point plots (Fig. 6B). The pterygium groups exhibited elevated levels of Th2 cells, but decreased levels of CD8 T cells, cytotoxic cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, T cells, Th1 cells, and Th17 cells. Correlation analysis of 24 immune cell types revealed that cytotoxic cells were positively correlated with CD8 T cells (r = 0.9), eosinophils (r = 0.76), and neutrophils (r = 0.78), while Th17 cells were negatively correlated with pDC (r = -0.62) and NK cells (r = -0.51). Additionally, Th2 cells were negatively correlated with NK cells (r = -0.45) and Tem (r = -0.41) (Fig. 6C). To identify potential diagnostic biomarkers for pterygium, we analyzed the association of four hub genes (FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13, and EGR2) with immune cells and functions in the PRJNA1147595 dataset using ssGSEA, examining possible relationships between these genes and the 24 immune cell types (Fig. 6D).

Differentially infiltrated immune cells and genes relationship in conjunctiva and pterygium samples. (A) Heatmap of differential immune cells in conjunctiva and pterygium. (B) The ssGSEA scores of 24 immune cells. (C) Correlation matrix of 24 immune cells. (D) Heatmap of correlation among 4 hub genes with immune cells. Scatter diagram of the correlation between FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13 and EGR2.

Verification through clinical sample and GSE51995

Notable differences and characteristics emerge from the results of HE staining, Masson staining, and vimentin immunohistochemical staining between conjunctival tissue and pterygium tissue. HE staining reveals distinct cellular morphologies and tissue architectures, with pterygium often displaying more prominent fibrous proliferation and cellular density. Masson staining accentuates the collagen fibers, which appear predominantly blue in both tissues, but pterygium may exhibit a denser and more irregular collagen fiber arrangement. Vimentin immunohistochemical staining highlights the intermediate filaments, showing widespread and intense positivity in pterygium cells, indicating higher vimentin expression compared to the conjunctiva, where the staining pattern may be more focal and less intense. These staining characteristics reflect the unique pathological features and compositional differences between pterygium and conjunctival tissues (Fig. 7A). Analysis of dataset GSE51995 reveals significantly higher expression levels of FN1 and SPRR1B in pterygium tissues compared to conjunctival tissues (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7B-C). Although SERPINB13 expression is elevated in pterygium relative to conjunctiva, the difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.15) (Fig. 7D). Conversely, EGR2 shows a trend of higher expression in conjunctiva compared to pterygium, but this difference is also not statistically significant (p = 0.57) (Fig. 7E). qPCR results confirm the significant increase in FN1 and SPRR1B expression in pterygium tissues compared to conjunctival tissues (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7F-G). Despite non-significant p-values for SERPINB13 and EGR2, their expression trends align with previous findings reported in PRJNA1147595, GSE2513, and GSE51995 (Fig. 7H-I).

Verification hub genes expression level through clinical sample and GSE51995. (A) HE staining, masson staining, and vimentin immunohistochemical staining of conjunctiva tissues and pterygium tissues. Scale bar: 200 μm. (40×). (B-E) The expression levels of FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13 and EGR2 among conjunctiva tissues and pterygium tissues in GSE51995 dataset. (F-I) RT-qPCR results of FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13 and EGR2 in conjunctiva tissues and pterygium tissues.

Identification of potential drug candidates

To pinpoint potential drug candidates that target the two identified feature genes, we conducted a comprehensive analysis using data sourced from the DSigDB databases. We undertook an extensive screening to identify the top 6 drug molecules, guided by an adjusted P value < 0.05 as per the DSigDB database (illustrated in Fig. 8A-B). Among these, alitretinoin CTD 00003402 and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate CTD 00006852 emerged as a prominent candidate, demonstrating interactions with all two feature genes and achieving a notable combined score of 360,083 and 290,763. The remaining drug candidates exhibited interactions with FN1 and SPRR1B, offering valuable insights for the advancement of pterygium treatment research and development.

Discussion

Pterygium, an ocular condition characterized by abnormal conjunctival tissue proliferation, poses significant challenges due to associated discomfort and potential visual impairment10. This prevalent disease often leads to a diminished quality of life for patients, compounded by a high recurrence rate following surgical excision8. Additionally, complications such as dry eye syndrome, irreversible corneal astigmatism, and corneal scarring present ongoing clinical challenges9,10. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment modality. However, the limited efficacy of existing therapeutic approaches underscores the urgent need for novel biomarkers and treatment strategies to mitigate recurrence and improve patient outcomes25,26.

The analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) revealed substantial alterations, notably in the PRJNA1147595 dataset, where 2,437 DEGs were identified. Applying stringent selection criteria (p ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1) ensured the robustness of these findings, visually corroborated by volcano plots and heatmaps displaying distinct sample clustering. The biological implications of these DEGs extend beyond mere identification, paving the way for a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying pterygium development. In our study, we identified 52 co-differentially expressed genes (co-DEGs) in the PRJNA1147595 and GSE2513 datasets. Through the application of machine learning algorithms, four genes—FN1, SPRR1B, SERPINB13, and EGR2—were ultimately pinpointed as key biomarkers for pterygium. These candidates demonstrated significant diagnostic potential, as evaluated by ROC curve analysis. This approach underscores the effectiveness of combining computational methods with biological data to uncover novel biomarkers that may enhance early diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of pterygium. The robustness of these biomarkers across various datasets emphasizes their relevance and potential utility in clinical practice. Additionally, a comparative analysis of diverse machine learning techniques, including LASSO, SVM-FRE and Random Forests, highlights the reliability and consistency of our findings, indicating a converging consensus on the crucial role of these biomarkers in pterygium27,28. As research progresses, validating these biomarkers through rigorous clinical trials will be essential for establishing their role in routine diagnostic protocols and facilitating personalized management strategies for patients with this condition.

Notably, genes such as FN1 and SPRR1B, consistently upregulated across three distinct datasets and clinical samples, imply a central role in pterygium pathogenesis and its inflammatory environment. The FN1 gene encodes for fibronectin, a large glycoprotein that is a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and basement membranes. Fibronectin plays a crucial role in cell adhesion, migration, growth, and differentiation. It acts as a bridge between cells and the ECM, mediating cell-matrix interactions that are essential for tissue organization, wound healing, and embryonic development. Fibronectin also participates in signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation, survival, and gene expression. Additionally, it plays a role in immune responses and can modulate the activity of growth factors and cytokines29,30. The SPRR1B gene belongs to the small proline-rich protein (SPRR) gene family and encodes for a small proline-rich protein 1B. These proteins are primarily expressed in epithelial cells, particularly in the skin and cornea. SPRR1B proteins are involved in the formation and maintenance of the cornified envelope, a structure that provides mechanical strength and barrier function to the epidermis and other stratified epithelia. They contribute to the cross-linking of proteins and lipids in the cornified envelope, enhancing its structural integrity31,32. Moreover, exploring the functional roles of these co-DEGs may reveal their contributions to the underlying pathophysiological processes, potentially identifying new therapeutic targets to reduce recurrence rates after surgical intervention33.

Gene expression analysis provides important insights into the molecular mechanisms of diseases and has aided in defining new therapeutic targets across various pathologies. In the present study, RNA sequencing is applied to gain detailed insights into the underlying molecular mechanisms of pterygium. Notably, this is the first study to use bioinformatic ssGSEA analysis to decipher the cellular microenvironment of pterygium. Thus far, only a limited number of studies have applied RNA sequencing to pterygium, including two studies utilizing cultured pterygium cells34,35 and recently published studies based on surgically removed pterygium tissue7,12,36,37. In this study, we investigate gene expression alterations following pterygium excision and their correlation with immune cell infiltration. By utilizing transcriptomic analyses and bioinformatics tools, we aim to identify key molecular features and pathways involved in pterygium pathogenesis. Our findings reveal significant upregulation of specific genes, including FN1 and SPRR1B, across multiple datasets, indicating their potential as biomarkers. Furthermore, the observed immune microenvironment suggests a pivotal role for immune responses in pterygium development, paving the way for innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies38,39. Our immune infiltration analysis revealed a significant increase in Th2 cell infiltration within pterygium tissue, contrasting with a notable reduction in cytotoxic CD8 + T cells and other immune cell types. This shift indicates a potential Th2-skewed immune environment, which is implicated in various chronic inflammatory conditions. The presence of increased Th2 cells may facilitate the secretion of cytokines promoting fibrosis and tissue remodeling, thereby contributing to pterygium pathogenesis. This immune landscape aligns with findings from other studies suggesting similar Th2 polarization in inflammatory diseases, prompting considerations for immune-modulating therapies in pterygium management. Furthermore, exploring interactions between different immune cell types is crucial, as they may elucidate mechanisms of immune evasion and disease persistence. Future research should focus on characterizing these interactions to fully understand their impact on disease progression and response to potential immunotherapies.

Pathway analysis conducted using GSEA and GSVA revealed critical signaling pathways enriched in pterygium, notably the PID_INTEGRIN1_PATHWAY and MET_ACTIVATES_PTK2_SIGNALING pathways. The identification of these pathways offers valuable insights into the biological processes involved, especially regarding cellular communication and modulation of the immune response. Upregulation of integrin signaling suggests enhanced cell adhesion and migration, aligning with the proliferative nature of pterygium tissue. Conversely, downregulation of pathways like PID_MAPK_TRK_PATHWAY may indicate dysregulation of cellular proliferation and survival mechanisms. Comprehending these pathways not only contributes to elucidating the pathogenesis of pterygium but also lays the groundwork for developing targeted therapies. For example, inhibiting integrin signaling could represent a novel therapeutic approach for managing pterygium recurrence40. Such targeted interventions could ultimately transform the clinical management of pterygium, enhancing patient outcomes through personalized therapies. We also find alitretinoin CTD 00003402, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate CTD 00006852, 8-Bromo-cAMP, Na CTD 00007044 and vitinoin CTD 00007069 emerged as a prominent candidate, demonstrating interactions with two feature genes FN1 and SPRR1B.

Emerging evidence highlights distinct molecular profiles between primary and recurrent pterygia. Studies have demonstrated that interleukin-10 (IL-10) expression is significantly upregulated in primary pterygium tissues compared to recurrent lesions, whereas transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) levels are markedly elevated in recurrent pterygia relative to their primary counterparts. This differential expression suggests that TGF-β1 overexpression may contribute to pterygium recurrence, potentially through its pro-fibrotic and inflammatory effects41. Furthermore, comparative analyses reveal that tumor suppressor protein p53, anti-apoptotic marker Bcl-2, and proliferation antigen Ki-67 are expressed at higher levels in primary pterygium tissues than in normal conjunctival tissues. Intriguingly, recurrent pterygia exhibit a statistically significant increase in Bcl-2 expression compared to primary lesions, indicating that Bcl-2-mediated inhibition of apoptosis may play a critical role in disease recurrence. These findings collectively underscore the dynamic interplay between apoptosis regulation, cellular proliferation, and fibrogenic signaling in pterygium pathogenesis and recurrence mechanisms33. Study has compared biomarkers among atrophic, hypertrophic, and intermediate pterygium subtypes, revealing that YKL-40 expression levels were significantly elevated in all three pterygium types compared to normal conjunctival tissues. However, no statistically significant differences in YKL-40 expression were observed between the three pterygium subtypes. This suggests that while YKL-40 may serve as a biomarker distinguishing pathological pterygium tissue from normal conjunctiva, it does not exhibit differential expression patterns among the clinically classified pterygium subtypes. Pseudopterygium arises from damage to limbal stem cells and/or their niche microenvironment, leading to limbal stem cell deficiency42. This triggers conjunctival tissue proliferation invading the cornea, while the limbal stem cell population remains deficient43. Currently, there is a notable lack of transcriptomic studies investigating molecular differences among pseudopterygium, atrophic pterygium, fleshy pterygium, and normal conjunctival tissues. Addressing this gap could advance our understanding of their distinct pathogenesis and inform targeted therapeutic strategies.

The limitations of this study necessitate careful consideration. Firstly, while the sample size is adequate for preliminary insights, it may not fully capture the heterogeneity of pterygium cases, potentially impacting the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, the lack of extensive clinical validation constrains the robustness of the identified biomarkers and pathways, highlighting the need for larger, prospective studies to confirm these results. Additionally, the reliance on bioinformatics methods, despite their power, may overlook intricate biological interactions that could be revealed through wet lab experiments. Moreover, potential batch effects across different datasets could introduce variability in the differential expression analysis, influencing the identification of consistent biomarkers. Addressing these limitations is crucial for enhancing the credibility and applicability of our findings in clinical settings.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the molecular characteristics and immune microenvironment of pterygium, emphasizing key biomarkers and signaling pathways that may guide future diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. The identification of potential biomarkers, such as FN1 and SPRR1B, highlights their significance in pterygium pathogenesis and offers a foundation for further exploration aimed at integrating these findings into clinical practice. By bridging the gap between bioinformatics and clinical application, our research lays the groundwork for improved patient management and the development of innovative therapeutic approaches, ultimately enhancing the quality of care for individuals affected by pterygium.

Data availability

Our RNA-seq data have been deposited in Sequence Read Archive (SRA https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1147595?reviewer=3k3nnr66jke53qo77la1sbt91b) with accession numbers PRJNA1147595 and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession numbers GSE2513 and GSE51995.

References

Coroneo & T, M. Pterygium as an early indicator of ultraviolet insolation: A hypothesis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 77, 734–739 (1993).

Maurizi, E. et al. Tara. A novel role for CRIM1 in the corneal response to UV and pterygium development. Exp. Eye Res. 179 (2019).

Bradley, J. C., Yang, W., Bradley, R. H., Reid, T. W. & Schwab, I. R. The science of pterygia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 94, 815–820 (2010).

Pan, Z. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pterygium: A cross-sectional study in Han and Manchu ethnic populations in Hebei, China. BMJ Open 9 (2019).

Lee, K. W. et al. Outdoor air pollution and pterygium in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 32 (2017).

Fu, Q. et al. Association between outpatient visits for pterygium and air pollution in Hangzhou, China. Environ. Pollut. 291, 118246 (2021).

Kim, Y. A. et al. Multi-system-Level analysis with RNA-Seq on pterygium inflammation discovers association between inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and oxidative phosphorylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25094789 (2024).

Essuman, V. A., Ntim-Amponsah, C. T., Vemuganti, G. K. & Ndanu, T. A. Epidemiology and recurrence rate of pterygium post excision in Ghanaians. Ghana. Med. J. 48, 39–42. https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v48i1.6 (2014).

Sabater-Cruz, N. et al. Postoperative treatment compliance rate and complications with two different protocols after pterygium excision and conjunctival autografting. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 31, 932–937. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120917335 (2021).

Eze, B. I., Maduka-okafor, F. C. & Okoye, O. I. Chuka-okosa, C. M. Pterygium: A review of clinical features and surgical treatment. Niger J. Med. 20, 7–14 (2011).

Suarez, M. F. et al. Transcriptome analysis of pterygium and pinguecula reveals evidence of genomic instability associated with chronic inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222112090 (2021).

Wolf, J. et al. Characterization of the cellular microenvironment and novel specific biomarkers in pterygia using RNA sequencing. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 714458. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.714458 (2021).

Pan, Z. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pterygium: A cross-sectional study in Han and Manchu ethnic populations in Hebei, China. BMJ Open. 9, e025725. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025725 (2019).

Wong, Y. W., Chew, J., Yang, H., Tan, D. T. & Beuerman, R. Expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 in pterygium tissue. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90, 769–772. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2005.087486 (2006).

Hou, A. et al. Evaluation of global differential gene and protein expression in primary pterygium: S100A8 and S100A9 as possible drivers of a signaling network. PLoS ONE. 9, e97402. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097402 (2014).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-7 (2013).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Huang, S. et al. Applications of support vector machine (SVM) learning in cancer genomics. Cancer Genomics Proteom. 15, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.21873/cgp.20063 (2018).

Breiman. Random forests. MACH LEARN. 45(1), 5–32 (2001). (2001).

Hnzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7–7 (2013).

Ogata, H. et al. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.1.29 (1999).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Prot. Sci. Publ. Prot. Soc. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–d592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Yoon, C. H., Seol, B. R. & Choi, H. J. Effect of pterygium on corneal astigmatism, irregularity and higher-order aberrations: A comparative study with normal fellow eyes. Sci. Rep. 13, 7328. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34466-4 (2023).

Dong, S., Wu, X., Xu, Y., Yang, G. & Yan, M. Immunohistochemical study of STAT3, HIF-1α and VEGF in pterygium and normal conjunctiva: Experimental research and literature review). Mol. Vis. 26, 510–516 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Distinct molecular subtypes of systemic sclerosis and gene signature with diagnostic capability. Front. Immunol. 14, 1257802. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1257802 (2023).

Hou, Q. et al. Potential therapeutic targets for COVID-19 complicated with pulmonary hypertension: A bioinformatics and early validation study. Sci. Rep. 14, 9294. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60113-7 (2024).

Zhang, X. X., Luo, J. H. & Wu, L. Q. FN1 overexpression is correlated with unfavorable prognosis and immune infiltrates in breast cancer. Front. Genet. 13, 913659. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.913659 (2022).

Pan, S. et al. FN1 mRNA 3’-UTR supersedes traditional fibronectin 1 in facilitating the invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer through the FN1 3’-UTR-let-7i-5p-THBS1 axis. Theranostics 13, 5130–5150. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.82492 (2023).

Cheng, H. et al. Bladder cancer patients with elevated SPRR1B expression experiencing a poor prognosis. Arch. Esp. Urol. 77, 554–569. https://doi.org/10.56434/j.arch.esp.urol.20247705.76 (2024).

Barbero, G., Castro, M. V., Quezada, M. J. & Lopez-Bergami, P. Bioinformatic analysis identifies epidermal development genes that contribute to melanoma progression. Med. Oncol. 39, 141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-022-01734-8 (2022).

Turan, M. & Turan, G. Bcl-2, p53, and Ki-67 expression in pterygium and normal conjunctiva and their relationship with pterygium recurrence. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 30, 1232–1237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120945903 (2020).

Larráyoz, I. M. et al. Molecular effects of Doxycycline treatment on pterygium as revealed by massive transcriptome sequencing. PLoS ONE. 7, e39359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039359 (2012).

Larrayoz, I. M., Rúa, Ó., Velilla, S. & Martínez, A. Transcriptomic profiling explains Racial disparities in pterygium patients treated with Doxycycline. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 7553–7561. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14951 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis to identify the important coding and Non-coding RNAs involved in the pathogenesis of pterygium. Front. Genet. 12, 646550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.646550 (2021).

de Guimarães, J. A. et al. Transcriptomics and network analysis highlight potential pathways in the pathogenesis of pterygium. Sci. Rep. 12, 286. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04248-x (2022).

Gao, J. et al. Elevated KDM4D expression in pterygium: Impact and potential Inhibition by lycium barbarum polysaccharide. J. Ocul Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2023.0130 (2024).

Hu, Y., Atik, A., Qi, W. & Yuan, L. The association between primary pterygium and corneal endothelial cell density. Clin. Exp. Optom. 103, 778–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.13049 (2020).

Runemark, A., Moore, E. C. & Larson, E. L. Hybridization and gene expression: Beyond differentially expressed genes. Mol. Ecol. e17303 https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17303 (2024).

Eroğul, Ö. & Şen, S. Comparison of biomarkers playing a role in pterygium development in pterygium and recurrent pterygium tissues. Diagnostics (Basel Switz.). 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14232619 (2024).

Urbinati, F. et al. Pseudopterygium: An algorithm approach based on the current evidence. Diagnostics (Basel Switz.). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12081843 (2022).

Le, Q., Xu, J. & Deng, S. X. The diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. Ocul. Surf. 16, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.11.002 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the contributors to the public databases used in this study.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82460201, 81860171), National clinical key specialty ophthalmology open foundation (Grant No. ZKF2024041 and ZKF2024042). Yunnan Provincial Health Committee Training program for leading medical talents (L2019029). Yunnan University Medical Research Foundation (YDYXJJ2024-0003). China Scholarship Council (202208535051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hai Liu and Liwei Zhang conceived this study. Ji Yang, Hai Liu, Yan Li and Liwei Zhang designed the study. Ji Yang, YaNan Chen, ChengYan Fang and HongQin Ke contributed to conducting experiments and analyzed the data. Ji Yang and YaNan Chen wrote the manuscript. Clinical samples were collected and provided by ChengYan Fang, HongQin Ke, RuiQin Guo and YunLing Xiao. Ping Xiang and RuiQin Guo reviewed the manuscript and made critical corrections. Hai Liu and Liwei Zhang provided the funding for the sequencing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used WenXinYiYan TOOL in order to revise English sentences. After using this tool, we reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Ethics declarations

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University (approval number: 2022198), and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Chen, YN., Fang, CY. et al. Investigating immune cell infiltration and gene expression features in pterygium pathogenesis. Sci Rep 15, 13352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98042-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98042-8