Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the flow rate accuracy and bolus doses of four portable pumps with different mechanisms. We evaluated two electronic (COOPDECH Amy PCA [Amy] and CADD-Solis) and two elastomeric balloon-type pumps (COOPDECH Balloonjector and Rakurakufuser) under the following conditions: placement with an epidural catheter, operation on a shaking table, warming to 32 °C, and at room temperature (control, 25 °C). Amy maintained consistent flow rates across all conditions. The CADD-Solis also exhibited consistent flow rates, with minor yet statistically significant changes upon epidural catheter placement (− 5.0%, P = 0.005) and motion conditions (4.2%, P = 0.015). The Balloonjector and Rakurakufuser exhibited flow rate variations over time, and temperature increases significantly increased flow rates by 24.3% (P < 0.001) and 20.3% (P < 0.001), respectively. Bolus volume accuracy for the Amy, Balloonjector, and Rakurakufuser was not significantly affected under different conditions. The CADD-Solis showed a slight decrease in bolus volume with an epidural catheter (mean difference, 0.3 mL; P = 0.003). The electronic pumps maintained consistent flow rates across various conditions, whereas elastomeric balloon pumps exhibited variable rates influenced by time and temperature, increasing the risk of medication overdose. Bolus dosing accuracy was clinically satisfactory for all pump mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Portable infusion pumps are compact, versatile devices used to deliver a range of medication, including local anesthetics and opioids for analgesia1,2, chemotherapeutic agents3,4, and antimicrobial therapies5,6,7,8. These pumps support ambulatory care and reduce healthcare costs9,10. A previous North American study reported that approximately 85% of the anesthesiologists affiliated with the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine used these pumps for home catheter infusion, providing continuous peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative analgesia1. Given the possible lack of continuous medical supervision, the reliability of these pumps is crucial for ensuring consistent therapeutic effectiveness and side effect management5,11.

Commonly utilized mechanisms in portable infusion pumps are elastomeric balloons and electronic types1. Prior research has shown a patient preference for the elastomeric balloon type because of its simplicity, light weight, and user-friendliness3,12. However, factors, such as changes in balloon-reservoir size over time13,14, temperature13,14, outlet resistance15,16,17, atmospheric pressure18, and the pump’s height relative to the outlet site17,19, can influence the infusion flow rates of the elastomeric pumps. By contrast, electronic pumps offer more precise and flexible adjustable dosing regimens2. A recent advancement in this field involves an electronic portable pump featuring disposable, ultrasmall micropump technology measuring 10 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm. This miniaturization is expected to improve portability by reducing weight while maintaining accuracy20. However, the exactitude of electronic pumps equipped with micropump technology has not yet been thoroughly investigated. Additionally, the stability of the infusion flow rates under conditions that assume a patient’s dynamic activity and the accuracy of bolus dosing have not been assessed for either pump type.

This study aimed to address three knowledge gaps: accuracy of electronic pumps equipped with micropump technology; continuous dosing accuracy in dynamic motion; accuracy of bolus dosing. This study examined four commercially available pumps (one electronic featuring micropump technology, one standard electronic, and two elastomeric balloons) and assessed their performance in terms of continuous dosing accuracy under temperature fluctuations, during epidural catheter placement, in dynamic motion conditions, and for bolus dosing accuracy.

Methods

This study did not require approval from an institutional ethics board. In this study, four types of commercially available portable pumps were used (Table 1, Supplemental Table S1). The COOPDECH Amy PCA (Daiken Medical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) is the electronic type, featuring ultrasmall micropump technology; CADD-Solis (Smiths Medical Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) served as the standard electronic type; COOPDECH Balloonjector (Daiken Medical Co., Ltd.) and Rakurakufuser (Smiths Medical Japan Ltd., equivalent to VESSEL FUSER; AuBEX Corp., Tokyo, Japan) were the elastomeric balloon type. Different fluid delivery systems of two electronic pumps are illustrated in Fig. 1. These pumps were equipped with an adjustable flow rate system and bolus delivery functionality. All devices complied with Japanese standards. The two elastomeric balloon pumps complied with the standards for pressurized medicinal infusion pumps approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. These standards require a flow rate accuracy within ± 20% of the nominal rate when tested with either saline or a 5% glucose solution at body surface temperature (32 °C ± 2 °C) or room temperature (23 °C ± 2 °C), depending on the intended use conditions. The two electronic types conformed to JIS (Japanese Industrial Standards) T0601-2–24, which is equivalent to the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60,601–2–24.

Fluid delivery systems of electronic pumps: (a) COOPDECH Amy PCA: The micropump measures 10 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm. During pump expansion, the upstream valve opens to draw fluid in, while during contraction, the downstream valve opens to discharge the solution. (b) CADD-Solis: The device employs three pistons that sequentially compress an infusion tube. Coordinated movement of upstream, middle, and downstream pistons alternates between occlusion and release to drive fluid delivery through peristaltic action.

The pumps were filled with 0.9% normal saline to their maximum capacity and set at an infusion flow rate of 4 mL/h. Fluid was collected in a glass bottle placed on a recently calibrated electronic balance (A&D GX 6002 A [weighing capacity = 6200 g, scale division d = 0.01 g, verification scale interval e = 0.1 g], A&D Company, Tokyo, Japan) connected to a laptop (Fig. 2). The use of glass bottles eliminated electrostatic interference, and the total weight of the filled container fell within the manufacturer’s recommended optimal weighing range. The top of the collection bottle was sealed with plastic wrap to minimize evaporation. Weight measurements were recorded every 10 min, and hourly flow rates were calculated based on these readings. This gravimetric method of measuring flow rates was adopted based on previous similar studies13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The dosing period was considered complete when the measured flow rate decreased to < 2.0 mL/h (50% of the set infusion flow rate). The room temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and the height of the pumps relative to the outlet site was kept constant. Disposable devices were used only once; the COOPDECH Amy PCA was recharged before each experiment, and the CADD-Solis was equipped with new batteries for each experiment.

The experiments were conducted under four conditions: (1) epidural catheter condition, measurements with an epidural catheter (Perifix ONE Catheter, 20 gauge, 100 cm; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany); (2) motion condition, measurements conducted while placing pumps on a shaking table (Mild Mixer PR-36; Taitec Corporation, Saitama, Japan; setting: 50% speed, low angle); (3) warming condition, measurements with pumps warmed in an incubator set at 32 °C (Sanyo Incubator MIR-153; Sanyo, Osaka, Japan); (4) control condition, baseline measurements without any additional manipulation. The bolus doses (3 mL in each pump) were measured under the same four conditions as previously mentioned.

The accuracy of the continuous infusion flow rate was evaluated using two criteria: the average measured flow rate as a percentage of the set flow rate (4 mL/h) during the dosing period (%); the percentage of dosing time within the range of 100% ± 15% of the set flow rate during the dosing period (%). The criterion of within 100% ± 15% was based on benchmarks established by similar studies13,14,19,21. The accuracy of bolus dosing was assessed based on the measured bolus dose volumes (in milliliters).

All experiments were performed in triplicates, and considering precedents from similar studies, three measurements were deemed sufficient13,14,19,21. Results are expressed as mean (standard deviation). Comparisons among conditions were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the ANOVA results were significant, Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for comparison with the control condition. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Specifically, it is a modified version of the R commander designed to incorporate statistical functions frequently used in biostatistics22.

Results

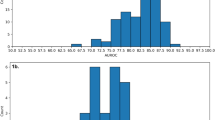

The measured flow rate profiles during the dosing period are shown in Fig. 3. Under control conditions, both COOPDECH Amy PCA and CADD-Solis exhibited consistent flow rates throughout the dosing period. However, the COOPDECH Balloonjector showed a gradual decline in flow rate from the start to the end of administration, whereas Rakurakufuser displayed an accelerated flow rate in the latter half before cessation.

Measured flow rate profiles during the dosing period. The data illustrate the actual measured infusion flow rate as a percentage of the set flow rate (4 mL/h) (%). Control, corresponds to measurements at room temperature (25 °C); epidural catheter, indicates the use of a 20-gauge, 100-cm epidural catheter; motion, represents the condition on a shaking table; warming, denotes warming to 32 °C; gray zone, 100% ± 15% range of the set flow rate. The axis labels are consistent across all panels. Data are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Table 2 presents the average measured flow rate as a percentage of the set flow rate (4 mL/h) during the dosing period for each condition. The COOPDECH Amy PCA showed no significant changes in flow rates across conditions. The CADD-Solis showed a slightly reduced flow rate with the epidural catheter [93.1% (0.5%); mean difference, − 5.0%; 95% confidence interval (CI), − 1.7 to − 8.3 l; P = 0.005] and a marginally increased flow rate during motion [102.4% (0.7%); mean difference, 4.2%; 95% CI, 0.9 to 7.6; P = 0.015], both statistically significant yet small compared with the control condition [98.1% (1.6%)]. The COOPDECH Balloonjector showed a significant increase in the flow rate during warming [117.5% (0.7%); mean difference, 24.3%; 95% CI, 19.1 to 29.6; P < 0.001] compared with the control condition [98.2% (2.5%)]. Similarly, the Rakurakufuser significantly increased the flow rate during warming [99.3% (3.9%); mean difference, 20.3%; 95% CI, 11.6 to 29.1; P < 0.001] compared with the control condition [78.9% (3.6%)].

Table 3 presents the percentage of dosing time within the range of 100% ± 15% of the set flow rate during the dosing period. Both the COOPDECH Amy PCA and CADD-Solis showed no significant changes in accuracy within the 100% ± 15% range across conditions. Meanwhile, the COOPDECH Balloonjector showed significant differences across conditions, post-hoc analysis revealed no specific condition with a significant change compared with the control. In the warming condition, the Rakurakufuser exhibited a significantly higher percentage of dosing time within the 100% ± 15% accuracy range [89.1% (0.5%); mean difference, 58.2%; 95% CI, 31.8 to 84.5; P < 0.001] relative to the control [31.0 (12.2%)].

Table 4 presents the measured volumes of the bolus doses (3 mL). For the COOPDECH Amy PCA, COOPDECH Balloonjector, and Rakurakufuser, there were no significant changes in bolus volumes across different conditions. The CADD-Solis showed a statistically significant decrease in bolus volumes when used with an epidural catheter [2.7 (0.1) mL] compared with the control condition [3.0 (0.1) mL]; however, the mean difference was minimal (− 0.3 mL; 95% CI, − 0.1 to − 0.5; P = 0.003).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the infusion flow rate accuracy of four pumps under four different conditions: control, during epidural catheter placement, in dynamic motion, and with warming. The COOPDECH Amy PCA, an electronic pump featuring novel micropump technology, maintained consistent flow rates across all conditions. The standard electronic CADD-Solis also showed consistent flow rates, with slight changes (approximately 5%) observed during epidural catheter placement and motion conditions. In contrast, the elastomeric pumps, COOPDECH Balloonjector and Rakurakufuser, demonstrated dynamic changes in flow rates over time. Additionally, an increase in temperature from 25 °C to 32 °C significantly increased the flow rates of both elastomeric pumps by approximately 20%.

The two electronic pumps evaluated in this study use different mechanisms (as shown in Fig. 1); the COOPDECH Amy PCA uses an ultrasmall micropump that cyclically expands and contracts for infusion delivery, whereas the CADD-Solis administers by sequentially compressing (squeezing) the infusion tubes. Both pumps consistently maintained flow rates within the 100% ± 15% range under warming conditions or with the resistance of an epidural catheter. Stable flow has been highlighted as an asset for electronic pumps in previous studies13,14,16,17, and our results further indicate that this stability may not depend on their operating mechanisms. Moreover, this is the first study to demonstrate the stability of electronic pumps during dynamic motion. Although previous studies have indicated that the flow rates of electronic pumps can be affected by battery depletion or replacement, and component failures14,19,23, such scenarios were not explored in our research.

This study showed that the flow rates of the elastomeric balloon pumps exhibited significant changes over time and with temperature variation, consistent with the findings of previous studies13,14,19,21,24. The flow rates of these elastomeric pumps adhere to the Hagen-Poiseuille law, which states that the flow rate is directly proportional to the fourth power of the catheter radius and infusion pressure and inversely proportional to the fluid viscosity and catheter length15. The extent of balloon contraction affects infusion pressure, whereas temperature alters fluid viscosity. Despite a previous study suggesting an influence on flow rates with microcatheters as narrow as 28 gauge15, our results showed no such effect with a 20-gauge epidural catheter on elastomeric pump flow rates. Because of potential catheter rupture, the use of catheters thinner than 24 gauge is not currently recommended15,25.

We evaluated the accuracy of bolus dosing, a novel contribution of this study. Our findings demonstrate that electronic pumps consistently achieved high accuracy in both flow rates and bolus dosing, reinforcing their reliability for clinical use. Numerous studies have established that a regimen incorporating scheduled intermittent or patient-controlled bolus dosing outperforms continuous infusion alone in regional anesthesia for pain management26,27,28,29. This underscores a notable clinical demand for accurate bolus dosing, and the insights from our study on its precision may hold clinical significance.

In contrast, elastomeric pumps demonstrated significant instability in flow rates and sensitivity to temperature changes, raising serious patient safety concerns. Notably, at 32 °C, the COOPDECH Balloonjector delivered an initial flow rate approximately 160% higher than expected, while at 25 °C, the Rakurakufuser consistently delivered less than 80% of the expected rate. These variations are particularly concerning in ambulatory settings, where environmental temperature fluctuations are often uncontrolled, and deviations in flow rates can go undetected. Elevated flow rates during postoperative pain management increase the risk of opioid-related complications, such as respiratory depression or nausea30, and local anesthetic systemic toxicity31. Conversely, reduced flow rates can result in inadequate pain control.

Our findings highlight electronic pumps as the more reliable option for consistent drug delivery. However, in facilities limited to elastomeric pumps, we recommend a risk mitigation strategy of using patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with bolus dosing instead of continuous infusion, as bolus doses showed consistent accuracy across varying conditions.

It is important to interpret these in vitro results cautiously when applying them to clinical settings, as various in vivo factors can affect delivery accuracy. Previous studies have demonstrated that back pressure and vertical displacement of pumps can significantly influence delivery accuracy17,32. Factors such as physiological venous pressure and changes in pump positioning relative to the infusion site should also be considered in clinical practice. Additionally, prior research reported that 20.5% of elastomeric balloon pumps failed to deflate correctly in clinical settings33. The absence of alarm systems in these pumps complicates the detection of malfunctions, though our study did not specifically address these issues.

This study had some limitations. First, the evaluated pumps had different manufacturer-recommended temperatures (listed in Table 1). The room temperature was maintained at 25 °C during experiments, which may not have been ideal for some pumps. Owing to this variation, direct comparisons between different pumps are difficult. Second, the pumps had different reservoir volumes, which could have influenced the dosing duration and flow rate accuracy assessment. Nonetheless, the pumps were filled to their maximum capacity, as recommended by the manufacturer, to achieve optimal performance. Third, an accuracy assessment was performed at a flow rate of 4 mL/h. Although this is a clinically relevant setting, different flow rates may produce different results because the pumps have adjustable flow rate systems (Table 1). Fourth, we used 0.9% normal saline for the experiments, consistent with previous studies13,14,15,17,19. However, as fluid viscosity varies with depending on the type and concentration, the results may not fully apply to other fluids34. The viscosity of 0.9% normal saline was assumed to be comparable to that of 0.5% ropivacaine13. For different fluids, measuring viscosity would be valuable to predict flow rate accuracy and enhance patient safety. Fifth, we did not evaluate variability between different manufacturing batches or the effects of shelf-life. Previous studies have shown that storage conditions, such as refrigeration or freezing, can influence flow stability35,36. Additionally, the devices used in this study were approved under Japanese regulatory standards. While the electronic pumps met JIS T0601-2–24 (equivalent to international IEC 60,601–2–24), the compliance of elastomeric pumps with international standards like ISO 28,620 could not be confirmed, which may limit the global applicability of our findings.

In conclusion, the electronic pumps COOPDECH Amy PCA and CADD-Solis maintained flow rates despite changes in conditions, such as epidural catheter placement, dynamic motion, and warming. The elastomeric balloon pumps, COOPDECH Balloonjector and Rakurakufuser, showed flow rate variability over time and with temperature fluctuations, posing a potential risk of unintended medication overdose. The accuracy of bolus dosing was clinically satisfactory, showing minimal impact of various conditions, regardless of the pump mechanism. These findings underscore the importance of selecting the appropriate pump type based on specific clinical scenarios to ensure optimal infusion regimens.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adhikary, S. et al. Assessing the current status of continuous peripheral nerve blocks in clinical practice in North America, a survey approach. J. Clin. Anesth. 65, 109870 (2020).

Ilfeld, B. M. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks: A review of the published evidence. Anesth. Analg. 113, 904–925 (2011).

Zahnd, D., Aebi, S., Rusterholz, S., Fey, M. F. & Borner, M. M. A randomized crossover trial assessing patient preference for two different types of portable infusion-pump devices. Ann. Oncol. 10, 727–729 (1999).

Sabbagh Dit Hawasli, R., Barton, S. & Nabhani-Gebara, S. Ambulatory chemotherapy: Past, present, and future. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 27, 962–973 (2021).

Sriskandarajah, S. et al. Safety and clinical outcomes of hospital in the home. J. Patient Saf. 16, 123–129 (2020).

Egerer, G. et al. Efficacy of continuous infusion of ceftazidime for patients with neutropenic fever after high-dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 15, 119–123 (2000).

Egerer, G. et al. Continuous infusion of ceftazidime for patients with breast cancer and multiple myeloma receiving high-dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 30, 427–431 (2002).

Fernández-Rubio, B. et al. Stability of antimicrobials in elastomeric pumps: A systematic review. Antibiotics (Basel) 11, 45 (2021).

Ilfeld, B. M., Esener, D. E., Morey, T. E. & Enneking, K. F. Ambulatory perineural infusion: The patients’ perspective. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 28, 418–423 (2003).

García-Suárez, J. et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH plus rituximab is an effective regimen in patients with poor-prognostic untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Results from a prospective observational study. Br. J. Haematol. 136, 276–285 (2007).

Ardon, A., Gillespie, N., Kolli, S., Shilling, A. M. & Warrick, M. Patient-controlled analgesia in high-risk populations: Implications for safety. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 10, 463–472 (2020).

Capdevila, X. et al. Patient-controlled perineural analgesia after ambulatory orthopedic surgery: A comparison of electronic versus elastomeric pumps. Anesth. Analg. 96, 414–417 (2003).

Ilfeld, B. M., Morey, T. E. & Enneking, F. K. The delivery rate accuracy of portable infusion pumps used for continuous regional analgesia. Anesth. Analg. 95, 1331–1336 (2002).

Ilfeld, B. M., Morey, T. E. & Enneking, F. K. Portable infusion pumps used for continuous regional analgesia: Delivery rate accuracy and consistency. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 28, 424–432 (2003).

Kasai, T. et al. Influence of microcatheter length on flow rates of disposable infusion kits. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 21, 858–860 (2004).

Hwang, B. S., Jeong, T. Y. & Kang, S. S. The comparative study of flow rate between IV extension tube and epidural catheter connected to patient controlled analgesia device. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 57, 610–614 (2009).

Hobbs, J. G. et al. Flow rate accuracy of ambulatory elastomeric and electronic infusion pumps when exposed to height and back pressures experienced during home infusion therapy. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 16, 735–742 (2019).

Mizuuchi, M., Yamakage, M., Iwasaki, S., Kimura, A. & Namiki, A. The infusion rate of most disposable, non-electric infusion pumps decreases under hypobaric conditions. Can. J. Anaesth. 50, 657–662 (2003).

Ilfeld, B. M., Morey, T. E. & Enneking, F. K. Delivery rate accuracy of portable, bolus-capable infusion pumps used for patient-controlled continuous regional analgesia. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 28, 17–23 (2003).

COOPDECH® AMY® PCA. Daiken Medical Co. Ltd. https://daiken-iki.co.jp/en/pi/seihin_amy.html (accessed on January 26, 2024).

Weisman, R. S., Missair, A., Pham, P., Gutierrez, J. F. & Gebhard, R. E. Accuracy and consistency of modern elastomeric pumps. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 39, 423–428 (2014).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48, 452–458 (2013).

Shah, T., Van Dam, T. & Madamangalam, A. Epidural pump malfunction. Anaesthesia 72, 269–270 (2017).

Ackermann, M., Maier, S., Ing, H. & Bonnabry, P. Evaluation of the design and reliability of three elastomeric and one mechanical infusers. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 13, 77–84 (2007).

Denny, N. M. & Selander, D. E. Continuous spinal anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 81, 590–597 (1998).

Singelyn, F. J., Seguy, S. & Gouverneur, J. M. Interscalene brachial plexus analgesia after open shoulder surgery: Continuous versus patient-controlled infusion. Anesth. Analg. 89, 1216–1220 (1999).

Ilfeld, B. M., Morey, T. E. & Enneking, F. K. Infraclavicular perineural local anesthetic infusion: A comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology 100, 395–402 (2004).

Ueda, K., Ueda, W. & Manabe, M. A comparative study of sequential epidural bolus technique and continuous epidural infusion. Anesthesiology 103, 126–129 (2005).

Satomi, S. et al. The efficacy of programmed intermittent epidural bolus for postoperative analgesia after open gynecological surgery: A randomized double-blinded study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 6297247 (2018).

Algera, M. H. et al. Opioid-induced respiratory depression in humans: A review of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling of reversal. Br. J. Anaesth. 122, e168-179 (2019).

Macfarlane, A. J. R., Gitman, M., Bornstein, K. J., El-Boghdadly, K. & Weinberg, G. Updates in our understanding of local anaesthetic systemic toxicity: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 76(S1), 27–39 (2021).

Riemer, J. E., Greber, N. C., Fruhauf, M., Weiss, M. & Piegeler, T. Susceptibility of two different PCA pumps to inaccurate delivery associated with pole position at low flow-rates in a pediatric setting - An experimental study. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-024-01233-3 (2024) (Online ahead of print).

Remerand, F. et al. Elastomeric pump reliability in postoperative regional anesthesia: A survey of 430 consecutive devices. Anesth. Analg. 107, 2079–2084 (2008).

Coley, S. C., Shaw, P. K. & Leff, R. D. The performance of three portable infusion-pump devices set to deliver 2 mL/hr. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 54, 1277–1280 (1997).

Capes, D. F. & Asiimwe, D. Performance of selected flow-restricting infusion devices. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 55, 351–359 (1998).

Rich, D. S. Evaluation of a disposable, elastomeric infusion device in the home environment. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 49, 1712–1716 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 20K17814). We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS conceived and designed the study, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and prepared the manuscript draft. MK conceived and designed the study, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, as well as edited the manuscript. YM designed the study, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, as well as edited the manuscript. KT supervised the study, interpreted data, and edited the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sekiguchi, R., Kinoshita, M., Maeda, Y. et al. Accuracy of infusion flow rates and bolus doses for portable infusion pump. Sci Rep 15, 13517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98533-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98533-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Wearable Devices for Subcutaneous Delivery of Large-Volume Biologics: Design, Use, and Regulatory Perspective

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2025)