Abstract

Unprecedented extreme climate events cause devastating infrastructure outages within power systems. Comprehensive outage identification is essential for the identification of critical components to ensure the uninterrupted power supply in a secure manner to withstand extreme weather events. Accurate outage identification, however, requires simulations of a large number of outage scenarios necessitating highly scalable computations thus challenging classical computing paradigms. Quantum computing provides a promising resolution by exploiting exponential scalability achieved through superposition and entanglement of voltage states. This paper devises a quantum contingency analysis (QCA) method to identify outage scenarios on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. Advanced quantum circuits incorporating Pauli-twirling, dynamic decoupling, and matrix-free measurement are designed to mitigate hardware-induced errors. A preconditioned hybrid method is devised to alleviate the computation burden of parameter optimization of quantum gates. Case studies identify line and generation outages via QCA in typical power systems. Our research underscores that quantum computing exhibits exponential scalability in identifying power grid outages and critical components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intensity and frequency of extreme weather events such as tornadoes, wildfires, and snowstorms, exacerbated by climate change and global warming, frequently result in infrastructure outages within electric power systems1,2. These failures such as line and generation outages, further cause unprecedented damage to human life and the economy3,4. This can be exemplified by a severe meteorological event in February 2021 - a winter storm in Texas - which instigated widespread blackouts and resulted in an estimated economic impact of at least 195 billion USD5.

Fundamentally, extreme events cause power infrastructure failures and trigger a sequence of grid emergencies such as voltage drop, overloading, and even system collapse, ultimately disrupting household services6,7. Identifying vulnerable components and potential grid outages in a preventive manner is a crucial challenge in mitigating and addressing the adverse effects of extreme events.

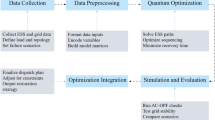

Contemporary power systems, however, span vast geographical areas and are characterized by a significant number of generators, transmission lines, and transformer stations, as shown in Fig. 1. Contingency Analysis (CA) is crucial for secure planning and operations of power grids in the wake of extreme weather events8,9 by proactively identifying latent outage emergencies through simulating power flows10,11. The complexity involved requires the utilization of advanced and scalable computational resources. Upon the detection of security concerns, CA provides warnings that signal the necessity for the development of preventive strategies12. Scalable and accurate CA is thus critical for power system operations with major implications for society.

Several CA methods have been developed including methods 1. prioritizing the impactful scenarios through techniques like sensitivity analysis13,14. 2. distributing computational effort by leveraging parallel computing to speed up computations15. 3. simplifying power flow calculations for quicker assessments through approximation methods and incremental analyses16. Machine learning and data-driven approaches offer an alternative to detailed simulations and aim to quickly predict contingencies by using models trained on historical data17,18. Hybrid methods combine analytical and numerical approaches to focus on the most critical contingencies, while real-time monitoring and adaptive analysis continuously assess the grid19. However, with the expansion of power grids as well as the increasing severity, impact, and frequency of extreme weather events, the complexity of the analysis increases accordingly thereby posing significant scalability challenges for classical-computing-based approaches.

In contrast to classical computing, quantum computing is emerging as a disruptive technology paradigm possessing an immense potential for exponential scalability20,21,22. Distributed quantum computation technology offers a framework to transition from small-scale quantum devices to large-scale quantum computers, significantly enhancing scalability23. Additionally, quantum information opens up fundamentally new possibilities for the development of high-performance quantum architectures and telecommunication networks24,25. This study aims to address several key considerations: harnessing quantum supremacy for scalability in contingency analysis, formulating contingency analysis within the quantum framework for efficient quantum algorithm exploitation, and mitigating the inherent challenges posed by Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) computers. The above considerations are addressed through Quantum Contingency Analysis (QCA) thus pioneering the exploitation of quantum computing for contingency analysis with major implications for secure operations of power systems.

The QCA employs a batched quantum power flow solver, which involves the reformulation of power system models into quantum language, and the optimization of a quantum circuit leveraging quantum entanglement and superposition for exponential scalability. In practical quantum-computing applications of QCA on real quantum computers, our study addresses measurement and noise issues, which are critical in the application of quantum computing. The improved quantum circuit design, along with hybrid quantum/classical computing techniques, enhances the QCA’s capability to handle a large number of power flows and identify latent outage emergencies such as power outages of key components whose failure could lead to serious consequences. We have validated the QCA effectiveness on a quantum simulator as well as on real IBM quantum computers.

Results

Power flow identification through QCA

A prominent feature of quantum technology is exponential-scale computation capability operationalized in this study through quantum bits (qubits) to represent the status of vectors26. Each qubit is a superposition of quantum states \(|0 \rangle\) and \(|1 \rangle\)27 and an n-qubit quantum state of voltage amplitude \(\pmb {V}\) can be modeled as \(|{\pmb V} \rangle = \sum \nolimits _{k}^{2^n}\nu _k|k\rangle\), where \(|k\rangle\) is the \(k^{th}\) quantum basis state and \(\nu _k\) is the corresponding probability amplitude; in essence, each additional qubit can double information processing capability. Quantum computers thus provide an opportunity for modeling power flow and performing contingency analysis in an exponentially scalable fashion.

We use a Variational Quantum Linear Solver (VQLS) algorithm28 to enable the exponentially scalable linear iteration process of power flow \(\pmb {F}(\pmb {x})\) under different outage scenarios shown in Fig. 1. The underlying idea is to construct a Variational Quantum Circuit (VQC) governed by a sequence of classical parameters to generate voltage variables \(\Delta \pmb {x}\) which include differences of voltage amplitudes \(\Delta \pmb {V}\) and voltage angles \(\Delta \pmb {\theta }\) such that the updated part (left side of power flow iteration formulation) is proportional to measurement (right side) in (1):

More details are discussed in the Materials and Methods section ‘Quantum-encoded reformulation.’

The efficacy of the QCA method is initially illustrated in a five-node transmission system shown in Fig. 2A. This system is comprised of two generators: the first is equipped at node 1, which delivers a constant output, and the second is located at node 5, which is responsible for supporting system losses. Node 5 is set as the slack bus, ensuring voltage stability and power balance within the network, while the remain of nodes are configured as PQ buses. We established a batched quantum power flow model using an 8-dimensional vector space to capture power flows under both normal and generator outage scenarios. Each scenario requires a four-dimensional vector space for power flow descriptions necessitating a total of \(\log _2 8 = 3\) qubits. To derive power flow solutions for each scenario, a variational quantum circuit is established utilizing \(R_y\), \(R_z\), and SX quantum gates. Additionally, CNOT gates are implemented to facilitate the entanglement among various qubits. This model leverages quantum entanglement and superposition principles, represented by a 3-qubit quantum circuit illustrated in Fig. 2B. The circuit is optimized to access the quantum states of voltage differences \(\Delta \pmb {V}\).

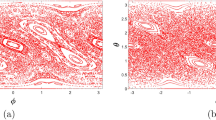

To maintain the positivity of the measurement output, the quantum states of \(\Delta \pmb {V}\) are decomposed into every foundational basis state. Consequently, \(\Delta \pmb {V}\) is expansively redefined in its basis states as \(|\Delta \pmb {V}\rangle = \sum \nolimits _{k}^{2^n}\nu _k|k\rangle\), as shown in Fig. 2C, where each qubit is geometrically represented by a Bloch sphere; for brevity, two basis states (out of eight) are illustrated. Following the optimization of the quantum circuit, the quantum states of each decomposed quantum basis \(|k\rangle\) are measured and the corresponding amplitudes are shown in Fig. 2D. Each measurement outcome in Fig. 2D corresponds to a quantum sphere in Fig. 2C. Amplitudes of QCA’s quantum states denotes normalized difference of electrical variables \(\Delta \pmb {x}\) including voltage amplitudes \(\Delta {V}\) and voltage angles \(\Delta {\theta }\) on basis states. The measurements closely match those obtained by Classical Quantum Analysis (CCA)29 (classical amplitudes are also shown in Fig. 2D). This alignment underscores the effectiveness of QCA through quantum computing.

Table 1 provides a summary of the power flow profiles obtained through QCA under normal operational conditions of the power grid. In the normal operating scenario, both voltage magnitudes and angles are within the voltage constraint requirements. Meanwhile, the QCA voltage results are close to the CCA voltage results, thereby underscoring the accuracy of the QCA approach.

Quantum state profiles under generation outage and normal operation scenarios. (A) 5-node transmission system topology. Scenario 1: a normal operation scenario; Scenario 2: the generator outage scenario where the generator at node 1 fails. (B) Quantum circuit under scenarios 1 and 2. (C) Quantum spheres. \(|\Delta \pmb {F}(\pmb {x})\rangle\) is decomposed as basis states \(|{k}\rangle\) from \(|{000}\rangle\) to \(|{111}\rangle\) on quantum spheres. (D) Quantum state outputs of optimized QCA quantum circuits for different basis and the comparison with CCA solutions.

Generation outages detection via QCA

The previous results validate the effectiveness of QCA under the normal operation of power grids. However, to detect underlying contingencies, QCA must be identifiable to component (both generator and line) outages. We first detect the voltage profiles under the generator 1 outage scenario. The \(|\Delta \pmb {F}(\pmb {x})\rangle\) for generation outages consist of the four decomposed quantum basis vectors on quantum spheres including \(|100\rangle\), \(|101\rangle\), \(|110\rangle\), and \(|111\rangle\) in Fig. 2C. By optimizing the corresponding circuit, the measurement output enables to accurately describe the quantum state of \(\Delta \pmb {V}\). The QCA quantum states are identical to the CCA results.

Table 1 presents the detected voltage profiles under the generator outage scenario. Compared with the voltage profiles under normal operation, the detected voltage magnitude at node 4 is decreased to 0.9881 p.u. due to a lack of power support from the generator 1, thereby indicating its importance on the voltage support of the power system. Since generator 5 can balance the power loss of the system, capacitors can be installed to prevent voltage drops under the generator 1 failure scenario.

Line outages detection via QCA

To identify line outages, a predefined list of line outage scenarios is systematically developed for parallel detection. This list includes outages of lines 1-5, 2-5, 1-2, and 1-3 as shown in Fig. 3A. For these four line outage scenarios, a 16-dimensional vector representation of \(\Delta \pmb {V}\) is formulated within a 4-qubit quantum circuit. Correspondingly, \(|\Delta \pmb {F}(\pmb {x})\rangle\) is decomposed into 16 basis states on the quantum sphere, as shown in Fig. 3B. Following the optimization of the quantum circuit, the quantum states for each sphere are measured (corresponding amplitudes are shown in Fig. 3C). The QCA quantum states are identical to the CCA results, which validates the effectiveness of QCA for line outage scenarios through quantum computing.

Figure 4A and C summarize the voltage angles and magnitudes of the power grid under different line outage scenarios. A single-line outage can have different impacts on voltages. For example, the line 1-2 outage results in low voltage magnitudes at nodes 3 and 4, dropping to 0.9726 p.u. and 0.9745 p.u., respectively. Additionally, Figure 4B and D provide a comparative analysis of the voltage angle and magnitude deviations from the normal operations under different line outage scenarios. Notably, the line 1-5 outage is identified as the most critical impact on the power grid’s operation. This outage causes voltage magnitude drops at nodes 3 and 4 by 0.1930 p.u. and 0.2160 p.u., respectively, which may trigger a load-shedding strategy to facilitate the grid’s recovery to stable conditions.

Figure 5A displays the topology of the IEEE 118-node system, including specific outage locations for pre-determined line outage scenarios. The IEEE 118 system comprises 64 PQ buses, 53 PV buses, 186 transmission lines, and 54 generators. Additionally, bus 69 is set as the slack bus, serving as the reference point for balancing the power mismatches across the network. A total of ten line outages are simulated using the QCA approach. As the system scale increases, the complexity of parameter optimization as well as that of Jacobian matrix decomposition increases if the contingency analysis is performed by using linear iterations. We have developed a preconditioned hybrid quantum solver for large systems to overcome the above challenges (see ‘Error mitigation by hybrid quantum/classical computing’ in the Materials and Methods for details). Accordingly, Fig. 5B and C present the voltage amplitudes and angles across the 118-node system under 11 predefined outage scenarios and 1 normal operation condition. QCA indicates that the outage of line 11-13 has the most serious impact on the system’s voltage amplitude, notably reducing node 13’s voltage amplitude to 0.9 p.u. Furthermore, the outage of line 22-23 leads to a significant decrease in both voltage amplitude and angle at node 22. These findings are instrumental in identifying the most vulnerable components of the 118-node system in the event of extreme conditions. Preventive strategies such as installing backup generation and capacitors are required in the vulnerable locations of the system. As importantly, the advantage of quantum computing is its theoretical requirement of only \(\lceil log_2{1298} \rceil =11\) qubits to solve the 11 outage scenarios, compared with the 6490 bits required by classical computing. This significant reduction in computational requirements underscores the potential of QCA for exponential scalability in outage identification within large-scale power systems.

To validate the effectiveness of QCA in practical system, we conducted the QCA method within New England power system30 which includes 10 generators and 46 branches (See Fig.6A). This test case involved six predefined line outage scenarios, specifically targeting outages at lines 1-2, 2-25, 4-14, 6-11, 10-13, and 25-26 as shown in Fig. 6A. Accordingly, Figs. 6B and C, detail the resulting voltage amplitude and angle profiles throughout the system. It can be seen that each line outage leads to distinct variations in the voltage profiles. For instance, the outage of line 10-13 leads to a decline of the voltage magnitude at bus 12, dropping from 1.0000 p.u. to 0.9984 p.u., because of the interruption in power support from line 10-13. Conversely, the bus 24 voltage in case 2 is increased from 1.0380 p.u. to 1.0798 p.u. because of the power flow redistribution. Thus, these results from the contingency analysis underscore the need for preventive strategies to mitigate potential system vulnerabilities.

Quantum state profiles under different line outage scenarios. (A) Line outages in transmission system topology including Scenario 1: line 1-5 outage; Scenario 2: line 2-5 outage; Scenario 3: line 1-2 outage; Scenario 4: line 1-3 outage. (B) Quantum spheres. The \(|\Delta \pmb {F}(\pmb {x})\rangle\) integrated four line outages is decomposed as basis states \(|{k}\rangle\) on quantum spheres. (C) Quantum state outputs of optimized QCA circuits under different basis states and the comparison with CCA solutions.

Voltage profiles under different line outages. (A) Voltage angles under different line outages. (B) Voltage angle deviations between line outages and normal operation. (C) Voltage magnitudes under line outages. (D) Voltage magnitude deviations between line outages and normal operation. Scenario 1: line 1-5 outage; Scenario 2: line 2-5 outage; Scenario 3: line 1-2 outage; Scenario 4: line 1-3 outage.

Voltage profiles of the 118-node system under line outages and normal operation scenarios. (A) System topology and the locations of line outages. (B) Voltage amplitudes under the line outages and normal operation scenarios. Scenarios 1-10: line outages, Scenario 11: normal operation. (C) Voltage angles under the line outages and normal operation scenarios.

Voltage profiles of the New England system under line outages and normal operation scenarios. (A) System topology and the locations of line outages (The system topology can be found in the references30,31, the system map is printed from @2025 Google which can be found from link32). (B) Voltage amplitudes under the line outages and normal operation scenarios. Scenarios 1-6: line outages, Scenario 7: normal operation. (C) Voltage angles under the line outages and normal operation. scenarios.

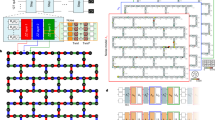

Outage identification on real noisy quantum devices

Having demonstrated the efficiency of QCA under different outage scenarios, the demonstration of the practical viability and efficiency of QCA when deployed on current quantum computing platforms such as IBM quantum hardware \({IBM\_lagos}\) is essential. This \({IBM\_lagos}\) device, a 7-qubit system with a 32-quantum volume, is characterized by a median CNOT error of \(1.127e^{-2}\), a median SX error of \(2.397e^{-4}\) and a median readout error of \(1.580e^{-2}\). Its basis gates include CNOT, ID, RZ, SX, and X gates, as detailed in Fig. 5B. The quantum shots are configured to 10000 in all experiments. Figure 5A and C illustrate the original quantum circuit alongside its modified counterpart, which incorporates specific mitigation methods.

Figure 5D illustrates the impacts of the noise in real hardware on QCA results and the performance of the mitigation methods that are used to relieve different errors in QCA results. The ‘ideal’ results in Fig. 5D reveal the measurement outputs of \(\Delta \pmb {V}\) for the decomposed basis states \(|010\rangle\) and \(|110\rangle\) on the quantum simulator. The ‘real\(\_\)raw’ results show the deviation impacts of the noise of real quantum hardware on QCA results. These hardware-induced errors cause slight deviations between the measurements obtained from the real quantum device and ideal solutions. To relieve the quantum errors, ‘real\(\_\)mitigate’ measurement results illustrate the enhanced efficacy of the modified quantum circuit, which incorporates the Pauli-twirling method to diminish coherent errors and a dynamic coupling technique to mitigate both dephasing and coherent errors. To further minimize the deviations, ‘real\(\_\)mitigate+’ is employed to correct the impact of measurement errors on the results by avoiding constructing and inverting the full error matrix Fig. 7.

Quantum measurement outputs for transmission generation outages on the quantum simulator and real quantum computer (\({IBM\_lagos}\)). (A) Original quantum circuit. \(D_l\): delay gate. (B) Topology of \({IBM\_lagos}\). (C) Modified quantum circuit with Pauli-twirling and dynamic decoupling method. (D) quantum measurement results. ideal: measurement results on the quantum simulator. real\(\_\)raw: measurement results on the original quantum circuit. real\(\_\)mitigate: measurement results on the modified quantum circuit. real\(\_\)mitigate+: measurement results on the modified quantum circuit with matrix-free measurement error mitigation.

Discussion

This paper has explored the application of variational quantum computing technology for the identification of power outages, highlighting its potential for exponential scalability with a linear increase in quantum qubits. Leveraging the VQLS algorithm, we have developed a quantum contingency analysis technique. After reformulating contingency analysis models into the quantum language, facilitating their compatibility with variational quantum computing algorithms, our research focused on evaluating the effectiveness of the devised quantum contingency analysis in identifying voltage profiles under various generator and line outages in power systems. The results demonstrated that the QCA method can harness quantum supremacy to produce exponentially scaled voltage vectors, significantly enhancing the capability to identify multiple outage scenarios with minimal quantum computing resources.

Unlike classical approaches such as the conjugate gradient method (CG)33 or purely quantum techniques such as Harrow-Hassidim-Lloyd method (HHL)34,35, the computational complexity of the QCA method does not have a rigid formula due to its hybrid quantum nature. However, the complexity of QCA is influenced by several different factors: 1) the properties of the Jacobian Matrix \(\pmb {J}\) specifically its size and condition number can increase the number of required quantum gates as these attributes scale up. Additionally, 2) as the complexity of the system grows, more complex variational quantum circuits are required which increases the iterations for cost function optimization and impacts the convergence efficiency of the method. Thus, the optimization algorithm may also affect the convergence performance of the QCA method.

However, quantum approaches such as HHL and VQLS offer enhanced resource efficiency with qubit consumption increasing logarithmically \(log_2(N)\) with the problem size due to quantum superposition. In contrast, classical computing requires linearly increasing bit consumption 64N for double-precision floating-point problems, indicating potentially superior scalability in quantum-based methods. The VQLS method utilizes variational quantum circuits that simplify quantum circuit construction and enhance noise resilience. Additionally, VQLS employs shallow quantum circuits to map power flow solutions in various contingency scenarios, which reduces circuit depth. These features make the VQLS-based QCA method advantageous in the NISQ era.

The exploration of detecting power system outages remains a novel frontier in quantum science, necessitating the integration of the physical nature of power systems into quantum computing. The QCA method effectively captures potential outages that could have severe impacts on power grids. The future application of QCA to ultra-scale systems and complex outage scenarios, such as \(N-m-m\) contingency analysis, requires further investigation due to several challenges as follows,

From a hardware perspective, current NISQ computers encounter limitations in supporting high-volume, deep quantum circuits for complex quantum algorithms. These constraints are primarily oriented from inherent quantum noise, limited coherence times, and high error rates prevalent in NISQ devices, which collectively impact computational accuracy and scalability. Additionally, the performance of quantum algorithms is also influenced by the number of qubits, their connectivity, and the availability of basic quantum gates on NISQ devices. For instance, if a QCA variational quantum circuit requires quantum gates that do not exist or connections between unlinked qubits, it necessitates recompilation into an equivalent quantum circuit that is compatible with available hardware. This recompilation process inevitably increases the depth of the QCA circuits, further complicating their implementation and potentially affecting their efficiency. Finally, the repetitive calculation for high-accuracy solutions on these quantum computers may lead to increased time consumption. From the algorithm perspective, the scaling up of system sizes can lead to a rise in both the number and complexity of quantum circuits. This expansion complicates the optimization of circuit parameters due to an enlarged search space for the optimal settings of quantum gates. Thus, there is an increasing need for more adaptive optimization algorithms to enhance the efficiency and reduce computational overhead in large-scale quantum computing environments.

To improve the QCA performance, we have devised a preconditioned hybrid quantum/classical computing approach to alleviate the computational burden associated with the decomposition of the Jacobian matrix and parameter optimization. Furthermore, we have established modified quantum circuits incorporating various quantum error mitigation methods, including Pauli-twirling36, dynamic decoupling37, and matrix-free measurement38 to relieve hardware-induced errors. In the future research, more hybrid quantum algorithms such as variants39 of VQLS can be implemented in special operation scenarios. We anticipate that enhanced methodologies will yield even more powerful and efficient QCA capabilities for broader application in complex power system analysis.

Methods

Power flow model

To capture underlying outages, the static state of system operation must be identified in real power grids40. Power flow formulates the steady-state energy flow based on the system model. Here, we use active/reactive power flow formulations \(\pmb {F}({\pmb {\theta }},{\pmb {V}})\) to calculate the voltage profile on each node i (\(i\in N\)), comprising a N-node power grid:

where, \(\pmb {V}\) and \(\pmb {\theta }\) denote voltage magnitude and voltage angel vectors of the system; \(\pmb {S}^g=[\pmb {{P}}^g,\pmb {Q}^g]^T\) and \(\pmb {S}^l=[\pmb {{P}}^l,\pmb {Q}^l]^T\) are the generation and load power vectors, respectively; \(\circ\) means Hadamard product; \(\bar{\pmb {Y}}(\pmb {\theta })\) is the extended admittance matrix.

We derive the fast decoupled power flow for contingency analysis on the fact that transmission grid voltage angles are mainly related to active power and voltage magnitudes to reactive power. For the nonlinear power flow equations, a set of power flow linear iterations is required until convergence:

\(\Delta \pmb {F}\), \(\Delta \pmb {\theta }\) and \(\Delta \pmb {V}\) denote the power mismatches, voltage angle differences and voltage magnitude differences; \(\pmb {J}\) denotes the Jacobian matrix. A full description of the power flow model is given in the supplementary materials41. With the calculated results, we can compare the power profiles on each node with the operating requirements to identify the outages and vulnerable components in the power grids.

Quantum-encoded reformulation

The quantum-encoded reformulation uses a variational quantum linear solver28 to search the solutions of the power flow linear iteration (3). The main target of this method is to establish a variational quantum circuit specified by a set of classical parameters so that the left-hand side of each linear iteration (3) is proportional to the right-hand side of (3). Mathematically, at each outage scenario, the corresponding formulation is established as (1). The corresponding Algorithm is summarized which mainly consists of outage scenario information updating, VQLS input preparation, and variational quantum circuit optimization in Fig. 1. To reach the power outage profiles, the algorithm first updates the deviations of power injections and the Jacobian matrix using (2). Then, the updated Jacobian matrix is encoded by a series of quantum Pauli gates42 as shown in Fig. 1. The VQC circuit43 is designed to describe the solution of (3) by a series of quantum gates. By optimizing the cost function44, VQC outputs are expected to get closer to the true values.

Error mitigation methods

While the quantum-encoded reformulation is theoretically capable of performing contingency analyses, practical implementation may encounter obstacles, which originate from two primary sources: quantum errors inherent in quantum computers, and classical errors arising from the optimization performance of quantum gates. Both quantum and classical computing techniques necessitate error mitigation techniques to ensure the effectiveness of contingency analyses in practical applications.

Error mitigation on quantum circuit design

The paper36 establishes Pauli-twirling-based VQC to mitigate quantum coherent errors for practical implementation. The Pauli-twirling-based VQC effectively averages out off-diagonal coherent errors across the Pauli basis, thereby enhancing the overall fidelity of the VQC circuit. Furthermore, Pauli-twirling helps mitigate the impact of coherent errors associated with gate-rescaling, thus avoiding conclusions potentially incompatible with the laws of physics. In the designed VQCs, the physical connectivity and circuit structure inevitably introduce idling times for qubits, which introduce dephasing and coherent errors. To address this, dynamic decoupling37 is employed in the VQC to identify idle periods of qubits and replace these idle intervals with specifically timed gate sequences. In particular, we incorporate the sequence \(\tau /4- R_x(\pi )-\tau /2-R_x(-\pi )-\tau /4\) for each idling period, where, \(R_x\) denotes \(R_x\) gate, \(\tau\) represents the idling time minus the duration of two \(R_x(\pi )\) pulses. To correct measurement errors in VQC circuits, we utilize a matrix-free measurement error mitigation method38. This approach effectively addresses measurement errors without the necessity of constructing and inverting a full error matrix. This method becomes increasingly important for large-scale quantum systems, where the size of the error matrix grows exponentially with the number of qubits.

Error mitigation by hybrid quantum/classical computing

As the scale of the power system expands, the decomposition of the Jacobian matrix and the optimization of parameters within quantum circuits become increasingly complex. To address this challenge, our paper develops a quantum preconditioned optimizer. The core principle of this method involves utilizing a preconditioned matrix \(\pmb {M}\) within an iterative optimization process45,46, aiming to minimize the errors in \(\Delta \pmb {x}\). This strategy distinguishes from traditional approaches that compute the Jacobian matrix to determine \(\Delta \pmb {x}\), thereby relieving the decomposition and parameter optimization burdens. The preconditioned errors \(\pmb {s}\) are updated as:

where, \(|\cdot \rangle\) denotes quantum state which is formulated via its basis state. For instance, \(|\Delta \pmb {V}\rangle = \sum \nolimits _{k}^{2^n}\nu _k|k\rangle\); \(\hat{\mathscr {H}}(\pmb {x},\Delta \pmb {x})_{k}\) is a residual vector at \(k^{th}\) iteration, which can be initialized as \(\pmb {F}(\pmb {x})- \pmb {J} \Delta \pmb {x}\) and updated as \(\hat{\mathscr {H}}(\pmb {x},\Delta \pmb {x})_{k+1}=\hat{\mathscr {H}}(\pmb {x},\Delta \pmb {x})_{k} + \rho _{k} \pmb J \pmb {p}_{k}\) in which the residual are adjusted to minimize and reach convergence iteratively; \(\pmb {\Psi }_{k}\) denotes the normalized state of the residual; \(\pmb {s}_{k}\) denotes the preconditioned errors; \(\pmb {p}_{k}\) refers to the search direction and can be updated \(\pmb {p}_{{k+1}}=\pmb {s}_{k+1} +\hat{\mathscr {H}}(\pmb {x},\Delta \pmb {x})_{{k+1}}^T \pmb {s}_{k+1}(\hat{\mathscr {H}}(\pmb {x},\Delta \pmb {x})_{k}^T \pmb {s}_{k})^{-1} \pmb {p}_{k}\); \(\rho _{k}\) is a coefficient, and can be obtained as \(\rho _{k}= \hat{\mathscr {H}}(\pmb {x},\Delta \pmb {x})_{k}^T \pmb {s}_{k}(\pmb {p}^T_{k} \pmb J\pmb {p}_{k})^{-1}\). Then, \(\Delta \pmb {x}_{k+1}\) can be updated by using the gradient descent rule \(\Delta \pmb {x}_{k+1}=\Delta \pmb {x}_{k} + \rho _{k} \pmb {p}_{k}\). This function continues until solutions of (3) are obtained. More variants of error correction methods are developed to relieve the noise impacts47.

Data availability

The simulation datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Paramasivam, M., Dasgupta, S., Ajjarapu, V. & Vaidya, U. Contingency analysis and identification of dynamic voltage control areas. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 30, 2974–2983. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2014.2385031 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Real-time contingency analysis with corrective transmission switching. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 32, 2604–2617. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2016.2616903 (2017).

Yao, R., Qiu, F. & Sun, K. Contingency analysis based on partitioned and parallel holomorphic embedding. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 37, 565–575. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2021.3095767 (2022).

Dimitrovska, T., Rudež, U. & Mihalič, R. Real-time application of an indirect power-system contingency screening method based on adaptive pca. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 34, 4665–4673. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2019.2919652 (2019).

Lee, C.-C., Maron, M. & Mostafavi, A. Community-scale big data reveals disparate impacts of the texas winter storm of 2021 and its managed power outage. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 9, 1–12 (2022).

Che, L., Liu, X., Wen, Y. & Li, Z. Identification of cascading failure initiated by hidden multiple-branch contingency. IEEE Transactions on Reliability. 68, 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1109/TR.2018.2889478 (2019).

Jia, Y., Xu, Z., Lai, L. L. & Wong, K. P. Risk-based power system security analysis considering cascading outages. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 12, 872–882. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2015.2499718 (2016).

Wang, M., Yang, M., Wang, J., Wang, M. & Han, X. Contingency analysis considering the transient thermal behavior of overhead transmission lines. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 33, 4982–4993. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2018.2812826 (2018).

Huang, J. et al. System-scale-free transient contingency screening scheme based on steady-state information: A pooling-ensemble multi-graph learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 37, 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2021.3097331 (2022).

Che, L., Liu, X. & Li, Z. Preventive mitigation strategy for the hidden n-k line contingencies in power systems. IEEE Transactions on Reliability. 67, 1060–1070. https://doi.org/10.1109/TR.2018.2833105 (2018).

Meneses de Quevedo, P., Contreras, J., Rider, M. J. & Allahdadian, J. Contingency assessment and network reconfiguration in distribution grids including wind power and energy storage. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy. 6, 1524–1533. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2015.2453368 (2015).

Sahraei-Ardakani, M., Li, X., Balasubramanian, P., Hedman, K. W. & Abdi-Khorsand, M. Real-time contingency analysis with transmission switching on real power system data. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 31, 2501–2502. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2015.2465140 (2016).

Guler, T. & Gross, G. Detection of island formation and identification of causal factors under multiple line outages. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 22, 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2006.888985 (2007).

Dimitrovska, T., Rudez, U. & Mihalic, R. Indirect power-system contingency screening for real-time applications based on pca. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 33, 1080–1081. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2017.2691556 (2018).

Angeline Ezhilarasi, G. & Swarup, K. S. Parallel contingency analysis in a high performance computing environment. In 2009 International Conference on Power Systems, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPWS.2009.5442650 (2009).

Peterson, N. M., Tinney, W. F. & Bree, D. W. Iterative linear ac power flow solution for fast approximate outage studies. IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems. PAS-91, 2048–2056, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAS.1972.293536 (1972).

Yang, S., Vaagensmith, B. & Patra, D. Power grid contingency analysis with machine learning: A brief survey and prospects. In 2020 Resilience Week (RWS), 119–125, https://doi.org/10.1109/RWS50334.2020.9241293 (2020).

Kim, C., Kim, K., Balaprakash, P. & Anitescu, M. Graph convolutional neural networks for optimal load shedding under line contingency. In 2019 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/PESGM40551.2019.8973468 (2019).

Babalola, A. A., Belkacemi, R. & Zarrabian, S. Real-time cascading failures prevention for multiple contingencies in smart grids through a multi-agent system. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 9, 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2016.2553146 (2018).

Chen, C.-C., Shiau, S.-Y., Wu, M.-F. & Wu, Y.-R. Hybrid classical-quantum linear solver using noisy intermediate-scale quantum machines. Scientific Reports. 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52275-6 (2019).

De Leon, N. P. et al. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science. 372, eabb2823 (2021).

Morstyn, T. & Wang, X. Opportunities for quantum computing within net-zero power system optimization. Joule. (2024).

Gyongyosi, L. & Imre, S. Scalable distributed gate-model quantum computers. Sci Rep. 11, 5172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76728-5 (2021).

Gyongyosi, L. & Imre, S. Advances in the quantum internet. Commun. ACM 65, 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1145/3524455 (2022).

Gyongyosi, L., Imre, S. & Nguyen, H. V. A survey on quantum channel capacities. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 20, 1149–1205. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2017.2786748 (2018).

Dervovic, D. et al. Quantum linear systems algorithms: a primer (2018). arXiv:1802.08227.

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics. 3, 625–644 (2021).

Bulat, H., Franković, D. & Vlahinić, S. Enhanced contingency analysis–a power system operator tool. Energies. 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14040923 (2021).

Shrestha, A. & Gonzalez-Longatt, F. Parametric sensitivity analysis of rotor angle stability indicators. Energies. 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165023 (2021).

Chegg Inc. System reduced New England transmission system, IEEE 39-bus system - Chegg. https://www.chegg.com/homework-help/questions-and-answers/system-reduced-new-england-transmission-system-ieee-39-bus-system-buses-1-38-represent-mai-q122960092 (2023).

Google LLC. Google Maps. https://www.google.com/maps (2025).

Nazareth, J. L. Conjugate gradient method. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics. 1, 348–353 (2009).

Harrow, A. W., Hassidim, A. & Lloyd, S. Quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations. Physical Review Letters. 103, 150502 (2009).

Feng, F., Zhou, Y. & Zhang, P. Quantum power flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 36, 3810–3812. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2021.3077382 (2021).

Kim, Y. & Wood, C. Scalable error mitigation for noisy quantum circuits produces competitive expectation values. Nat. Phys. 19, 752–759 (2023).

Ezzell, N., Pokharel, B., Tewala, L., Quiroz, G. & Lidar, D. A. Dynamical decoupling for superconducting qubits: a performance survey (2023). arXiv:2207.03670.

Nation, P. D., Kang, H., Sundaresan, N. & Gambetta, J. M. Scalable mitigation of measurement errors on quantum computers. PRX Quantum. 2, 040326. https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.040326 (2021).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Information-theoretic bounds on quantum advantage in machine learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 190505. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.190505 (2021).

Feng, F., Zhang, P., Zhou, Y. & Wang, L. Distributed networked microgrids power flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. (2022).

Stott, B. & Alsac, O. Fast decoupled load flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems. 859–869 (1974).

Brown, A. R. & Susskind, L. Second law of quantum complexity. Physical Review D. 97, 086015 (2018).

Kandala, A. et al. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature. 549, 242–246 (2017).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, P. & Feng, F. Noisy-intermediate-scale quantum electromagnetic transients program. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 38, 1558–1571. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2022.3172655 (2023).

Concus, P., Golub, G. H. & Meurant, G. Block preconditioning for the conjugate gradient method. SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing. 6, 220–252. https://doi.org/10.1137/0906018 (1985).

Feng, F., Zhang, P., Zhou, Y. & Shamash, Y. A. Noisy-intermediate-scale quantum power system state estimation. iEnergy. 3, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.23919/IEN.2024.0019 (2024).

Feng, F., Zhou, Y.-F. & Zhang, P. Noise-resilient quantum power flow. iEnergy. 2, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.23919/IEN.2023.0008 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) under the Solar Energy Technologies Office Award Number DE-EE0009341. This work relates to the Department of Navy award N00014-24-1-2287 issued by the Office of Naval Research. The U.S. Government has a royalty-free license throughout the world in all copyrightable material contained herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fei Feng: Algorithm design and software development, analysis of results, writing- original draft preparation. Yifan Zhou: Algorithm design, manuscript proofreading and editing. Mikhail A. Bragin: Algorithm design, manuscript proofreading and editing. Yacov A. Shamash: Methodology, manuscript proofreading and editing. Peng Zhang: Principal investigator, supervision, conceptualization, methodology, analysis, manuscript preparation and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, F., Zhou, Y., Bragin, M.A. et al. Quantum contingency analysis for power system steady-state security identification. Sci Rep 15, 15148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98776-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98776-5