Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) is a widespread situation, linked to patients’ dietary habits and/or geographical origins. On the other hand, hypervitaminosis D (VDO) is also a worldwide problem, mainly associated with uncontrolled self-administration. In this study, we investigated the effects of VDD and VDO on sex steroid production and ovarian histology in mice. In addition to addressing the rarely explored situation of VDO, the originality of our approach is to disconnect VDD/VDO situations from the well-known calciotrophic effect of vitamin D (VitD). Our data indicate that VDD led to a significant decrease in serum LH and FSH levels, independently of serum calcium levels. VDD was also associated with increased testosterone and reduced oestradiol levels. VDO animals showed increased LH and reduced testosterone levels. Hormonal changes in the VDO animal groups were correlated with a lower accumulation of transcripts of steroidogenic genes such as CYP11A1 and 3ß-HSD, whereas these transcripts were higher in the VDD groups. CYP19A1 transcripts were lower in VDD animals than in controls. This study highlights the complex interaction between vitamin D status, the regulation of reproductive hormones and, consequently, reproductive performance. It underlines the need for caution when oral vitamin D supplementation is chosen as a therapeutic action to boost female reproductive performance, as VDO can be as detrimental as VDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vitamin D (VitD), considered a veritable hormone, is essential for maintaining the body’s phosphocalcic homeostasis critical for bone growth and maintenance. Following WHO recommendations adult blood levels of 25-OH-vitamin D (d25OH = 25-OH-calciferol; Vit D3 + D2) should be between 30 and 45 ng/mL. If the blood VitD level is below 30 ng/mL, physicians usually prescribe VitD supplementation to bring it back to normal values1. Of note, it is estimated that around one billion people worldwide suffer from vitamin D deficiency (VDD), which can be caused by a variety of factors including, among others, insufficient exposure to sunlight, or/and a VitD-deficient dietary intake. Although VitD supplementation is a common method of remedying deficiency, it is important to note that excessive VitD intake is toxic and should be avoided2,3. Uncontrolled self-administration can then lead to VitD overdosage (VDO), with potential deleterious consequences such as loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, asthenia and high blood pressure1.

Among many physiological processes, VitD has been shown to play an important role in mammalian reproductive health, including ovarian steroidogenesis, folliculogenesis and ovarian reserve in women, as well as in men, spermatogenesis, acrosomal response and sperm quality4,5,6,7. While studies have assessed the impact of VDD on both natural and assisted reproduction7), few have distinguished between the calciotrophic and non-calciotrophic effects of VitD8,9,10,11. In a previous study, we found that female mice exposed to excessive levels of vitamin D, but maintained at normal levels of calcium, had a higher total number of oocytes12. However, in parallel, we observed a reduction in the rate of oocyte maturation and their ability to develop to the blastocyst stage after fertilization. Furthermore, in pregnant mice with excessive vitamin D levels, despite an increase in the number of offspring per litter, the survival rate of offspring was significantly reduced. In VDD mice, when calcium levels were reduced, there was a reduction in the total number of oocytes, the percentage of mature oocytes and their ability to develop to the blastocyst stage12. Under these conditions, the number of offspring per litter and offspring survival rates were also reduced, possibly indicating diminished implantation rate. Interestingly, these deleterious effects were not attenuated when VitD levels returned to normal while calcium was still deficient. Conversely, by correcting calcium levels in a situation where VDD was maintained, all these effects were attenuated. Overall, these observations suggested that VitD and calcium act partly independently of each other in defining optimal female reproductive performance. In the present report, to gain a better understanding of the respective impact of VitD and calcium on female reproductive performance, we used normo- and hypo-calcemic VDD and VDO mice and assessed various parameters, including hormone levels and expression of steroidogenesis players. In addition, we performed a more detailed histological analysis of the ovaries.

Results

The aim of this study was to determine the direct and indirect effects of VDD or VDO on serum levels of progesterone, estradiol, testosterone, LH and FSH, as well as on follicular dynamics, taking into account the key enzymes involved in steroidogenesis (CYP11A1, 3β-HSD and CYP19A1) based on the experimental design (Fig. 1).

Experimental design. Black circles and black Square: paricalcitol and Zoledronic acid injections, respectively. Black Rectangle: Calcitriol gavage. In this experiment, 195 NMRI female mice were utilized. Prior to the allocation of groups, 5 mice were randomly chosen for the assessment of blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and calcium levels. The remaining 190 mice were subsequently divided into 5 groups (n = 38 each): (1) control group, (2) vitamin D overdose (VDO) and normal calcium (VitD+Ca), these mice were treated with vitamin D daily with low phosphorus and calcium diet, (3) vitamin D and calcium deficient (VitD−Ca−), these mice were treated with paricalcitol and normal phosphorus and calcium diet, (4) vitamin D deficient and normal- calcium (VitD−Ca), these mice were treated with paricalcitol and high phosphorus and calcium diet, (5) vitamin D normal and calcium deficient (VitD Ca−), these mice were treated zoledronic acid with low phosphorus and calcium diet.

Assessment of vitamin D and calcium levels in different groups

Administration of paricalcitol together with a specific diet resulted in a significant reduction in serum 25(OH)D levels. In the VitD−Ca− and VitD−Ca groups, serum 25(OH)D levels on study day 72 were reduced to 10 ng/ml ± 0.5 and 10.5 ng/ml ± 0.7, respectively, which was significantly lower (p < 0.0001 each) than in the control group (36 ng/ml ± 4.1). On the contrary, in the VitD+Ca group supplemented with calcitriol (VDO), 25(OH)D level increased significantly to 87 ng/ml ± 2.5 compared with the control group (p < 0.0001), while in the VitD Ca− group it was similar to the control group at 38 ng/ml ± 2.6 (Fig. 2A).

Assessment of serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 (A), calcium (B), Alanine transaminase (ALT) (C) and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (D) content at day 72 in the different groups of mice. b c d indicates significant differences groups with a control group. Statistical differences between groups were obtained by a one-way ANOVA test (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001).

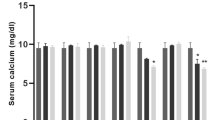

With regard to calcium, administration of zoledronic acid combined with a specific diet resulted in a significant (p < 0.0001) reduction in serum calcium levels in the VitD Ca- group (7.2 mg/dl ± 0.1) compared with the control group (9 mg/dl ± 0.1), despite normal VitD levels. Similarly, in the VitD-Ca- group, serum calcium values were significantly (p < 0.001) lower (7.8 mg/dl ± 0.2) than in the control group. For the VitD+Ca and VitD-Ca groups, serum calcium levels were equal to those of the control group, at 9.3 mg/dL ± 0.6 and 9.7 mg/dL ± 0.2, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Effect of serum vitamin D and calcium levels on liver function

When liver enzyme ALT was assessed in the different groups, we found that serum ALT levels were significantly up (p < 0.0001) in the VDD groups [VitD−Ca− (180 IU/L ± 3.0) and [VitD−Ca (234 IU/L ± 9.0)] when compared to the control group (24 IU/L ± 1.5), thus ALT increases irrespective of the calcium level (Fig. 2C). Identically, in the VDD animal groups serum AST levels were significantly (p < 0.0001) increased from 25 IU/L ± 1.5 in the control group to 93 IU/L ± 1.5 in the VitD−Ca− group and 91 IU/L ± 9.2 in the VitD−Ca, irrespective of the calcium level (Fig. 2D). On the contrary, in VDO animals with normal calcium level (VitD+Ca), a significant (p < 0.0001) decrease in serum ALT (5 IU/L ± 0.5) and AST (6 IU/L ± 0.5) levels were recorded. In the normal VitD animals deficient in calcium (VitD Ca−), no difference was recorded in the ALT (23 IU/L ± 1.5) and AST (25 IU/L ± 1.5) serum levels compared to the control group.

Effect of serum vitamin D and calcium levels on serum LH, FSH, progesterone, estradiol and testosterone levels

In the VDD animal groups, irrespective of the calcium level [VitD−Ca− (0.2 mIU/mL ± 0.1) and VitD−Ca (0.2 mIU/mL ± 0.1), the serum LH level was significantly (p < 0.0001) decreased in both groups compared with the control group (1.4 mIU/mL ± 0.4). Identically, in the same VDD animal groups, [VitD−Ca− (0.3 mIU/mL ± 0.1) and VitD−Ca (0.4 mIU/mL ± 0.08) (p < 0.0001)] serum FSH levels were significantly decreased when compared with the control group (1.7 mIU/mL ± 0.5). In the VDO animal group (VitD+Ca) the serum LH (2.1 mIU/mL ± 0.3) levels were significantly (p < 0.01) increased when compared with the control group. In the VDO animal group (VitD+Ca) serum FSH (2.6 mIU/mL ± 0.5 P < 0.01) and in the VitD Ca− animal group the serum LH (1.8 mIU/mL ± 0.2) and FSH (1.6 mIU/mL ± 0.5) values were similar to those of the control group (Fig. 3A and B). Serum estradiol level in the VDD animal groups, irrespective of the calcium level, decreased [VitD−Ca− (0.3 pg/mL ± 0.1) and [VitD−Ca (0.4 pg/mL ± 0.08)] significantly (p < 0.0001). In the VitD Ca− (2.8 pg/mL ± 0.6) and VitD+Ca (2.6 pg/mL ± 0.5)] serum estradiol levels were found unchanged, when compared with the control group (Fig. 3C). Regarding progesterone, only the VDD animal group deficient in calcium [VitD−Ca− (16.1 ng/mL ± 0.9)] did show a significantly (p < 0.0001) lower serum progesterone level when compared with the control group (29.5 ng/mL ± 0.9). None of the other groups showed differences (Fig. 3D).

Assessment of serum levels of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) (A), Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (B), Estradiol (C), Progesterone (D) and Testosterone (E), in the different groups of mice at day 72. b c d indicates significant differences groups with a control group. Statistical differences between groups obtained by one-way ANOVA test (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001).

Finally, serum testosterone level in the VDD animal groups, irrespective of the calcium level [VitD−Ca− (2.9 nmol/L ± 0.05) and VitD−Ca (2.7nmol/L ± 0.20], were significantly (p < 0.0001) increased when compared with the control group (1.7nmol/L ± 0.25). On the contrary, in the VDO [VitD+Ca (0.07 nmol/L ± 0.005)] serum testosterone level was significantly (p < 0.0001) decreased when compared with the control group. There was no significant difference in the serum testosterone level between the VitD Ca− animal group (1.7nmol/L ± 0.3) and the control group (Fig. 3E).

Effect of serum vitamin D and calcium levels on primordial, primary, secondary, tertiary, and de Graaf follicles

The mean distributions of follicles at different stages of maturation per ovary were compared between groups, and the results are presented in Figs. 4, 5 and 6. Interestingly, the VDD animal groups, irrespective of calcium level, showed significant decreases in follicle number at all stages of development (primordial, primary, secondary, tertiary and grafian; see Figs. 4 and 5). In VDO animals (VitD+Ca), there were most often no significant differences in follicle numbers, with the exception of the number of primary follicles, which was found to be lower (Fig. 4A1). In the VitD Ca- there were no significant differences in follicle numbers with the exception of primordial and primary follicles which was found to be lower (Fig. 4A1, B1). Looking at the number of atretic follicles, we observed that there was no significant difference in the average number of atretic follicles per ovary, whatever the group of animals considered (Fig. 4A2, C2, Fig. 5D2, E2). Only in VDD animals, regardless of calcium level, did we observe a decrease in the average number of primary atretic follicles (Fig. 4B2). Logically, taking into account the observed decrease in the number of follicles, especially in the VDD animal groups (Fig. 4A1, B1, C1 and Fig. 5D1, E2), looking at the ratio of atretic follicles at different stages of maturation to the total number of follicles, (Fig. 4A3, B3, C3, Fig. 5D3, E3) we noticed a significant decrease in the VDD animals’ group from primordial, primary, secondary, tertiary and graafian follicles irrespective of calcium level.

Distributions of different types of follicles per ovary, primary(A), primordial (B), secondary (C) tertiary (D)and Graafian (E) follicles. b c d indicates significant differences groups with a control group. Statistical differences between groups were obtained by a one-way ANOVA test (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001).

Distributions of different types of follicles per ovary, primary(A), primordial (B), secondary (C) tertiary ()Dand Graafian (E) follicles. b c d indicates significant differences groups with a control group. Statistical differences between groups were obtained by a one-way ANOVA test (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001).

Cross-sections of ovarian tissue from different groups; the cross-section from the control group represented the normal distribution of follicles at different stages along with distributed corpus luteums from the previous cycles in the cortex area. See the expanded follicular atresia in the sections from the experimental groups at various stages of the folliculogenesis. The intact follicles contain normal oocytes (NO), with homogenous cytoplasm without cytoplasmic vacuolation (CV), well-formed theca layers (black arrow), and normal integrity of granulosa cells (NGC) with no granulosa cell dissociation (GCD) and antrum formation (*), no hyalinization (HCG), normal cumulus oophorus integrity (NCOI) with no apoptotic granulosa cells (AGC) when compared to the atretic follicles (H&E staining, the photomicrographs with higher magnifications: 400× microscopic and 2.4× optical magnification).

Effect of serum vitamin D and calcium levels on relative expression of CYP11A1, 3β-HSD and CYP19A1 genes

Figure 7 shows the relative expression levels of the selected steroidogenic genes CYP11A1, 3ßHSD and CYP19A1 in the different animal groups. It is interesting to note that VDD, irrespective of calcium level, causes a significant overexpression of CYP11A1 and, conversely, a significant decrease in CYP19A1. VDD also caused a slight but significant increase in 3ßHSD expression only when calcium levels were deficient. In the VDO animal groups, expression of these same genes does not behave in the same way. VDO has no effect on the accumulation of CYP19A1 transcripts. In normo calcemic VDO animals, expression levels of CYP11A1 and 3ßHSD are significantly reduced (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Vitamin D, recently dubbed “hormone D”, has a broad spectrum of action in many tissues and has been associated with numerous diseases13. The interaction of VitD with its cell membrane receptor involves various molecular pathways, ultimately resulting in altered intracellular and serum calcium concentrations14,15. It should also be noted that VitD has direct genomic effects by controlling the expression of many genes with a VitD response element (VDRE) in their regulatory sequences16,17. Using an established VitD rodent model in which calcium levels can be controlled18 we assessed here the impact of VDD and VDO on follicular activity.

We first found that, irrespective of calcium levels, the liver enzyme activities ALT and AST were reduced in VDO animals and increased in VDD ones. Correction of VitD levels normalized the situations, whereas correction of calcium levels did not. This is in agreement with previous data19,20 and with the consensus interpretation that VDD can trigger inflammatory hepatic responses21,22. Focusing on the female gonad, we observed that VDO led to an increase in the number of mature oocytes, but a reduction in their developmental competency and offspring survival. On the contrary, and confirming earlier data7, both VDD and hypocalcemia (with normal VitD level) resulted in a reduction in the number and percentage of mature oocytes, blastocyst and fertility rates, as well as offspring survival. These observations show that VDO, VDD or hypocalcemia all have adverse effects on female reproductive function, suggesting that VitD and calcium act in part independently of each other in defining optimal female reproductive performance7.

To deepen our understanding of these situations with regard to ovarian reserve and VitD status, we conducted further research and, in particular, monitored follicular activity, hormone levels and the relative expression of key steroidogenic players at different stages of follicular development. We show that VDD or hypocalcemia (in a context of normal VitD) is associated with significant depletion of primordial follicles, a situation that was not reversed by either calcium correction or VitD replacement. This suggests that VitD and calcium are somehow equally important in maintaining the primordial follicle pool. These data are consistent with clinical reports indicating that VitD is essential for human ovarian reserve23,24,25. Since in these situations (VDD or hypocalcemia with normal VitD), the ratio of atretic follicles to total primary follicles was not different from that of the control animal groups, this suggests that follicular activation was primarily concerned rather than atresia. Thus, both VitD and calcium appear to be important for follicular activation. When VitD and calcium are depleted (VitD−Ca−) there is a general reduction in the number of follicles at all stages (primordial, primary, secondary, tertiary, graafian) which was corrected when VitD levels were back to normal, but not when calcium levels were normalized. This highlights the prevalence of VitD over calcium in determining optimal ovarian activity.

In addition to being important for follicular activation, VitD (but not calcium) also proves important throughout follicular development in determining follicular atresia, as shown by the fact that when looking at the ratio of staged atretic follicles (secondary, tertiary and to a lesser extent graafian) to the total number of follicles, all were increased compared to the control group.

In partial agreement with our observations, Sun et al. (2010) reported earlier that calcium deficiency in VDD context reduced both primordial and transitional follicle numbers, a situation that was resolved by calcium replacement10. In our case, calcium replacement did not completely restore follicular activity. This could be due to the different types of mouse models used, which cannot be compared, as Sun et al. used a knock-out model in which the enzyme converting inactive VitD to its active form was deleted10. In addition, both studies show differences in FSH and LH levels, which could also partly explain the discrepancies observed26,27. In our model, in the VDD situation associated with low calcium (VitD−Ca−), FSH and LH levels were low and could be normalized only by VitD replacement, but not by calcium replacement. This make sense, as FSH levels are expected to be low in VDD, since VitD is a known positive trans-acting regulator of the AMH gene, which in turn positively regulates FSH production. Therefore, in VDD, AMH is expected to be low and, consequently, so is FSH. Since the role of AMH in the ovary is to limit the early stages of follicular activation and reduce the sensitivity of follicles to FSH, thus maintaining ovarian reserve28,29,30,31,32,33, the behaviors we recorded seem quite logical. Of note, although serum calcium has been positively associated with AMH expression34,35, calcium supplementation did not normalize FSH levels in our model, further suggesting that VitD is a more important regulator of the follicular activation process than calcium. According to the “two-cell theory”, in the theca cells, LH facilitates the conversion of cholesterol to androstenedione and testosterone, which in the granulosa cells are converted to estradiol via aromatase activity (CYP19A1). Together with inhibin, estradiol then exerts a negative feedback effect controlling LH and FSH production34,35,36,37,38. In this context, our data show that, irrespective of calcium levels, VDD reduced FSH and LH levels and, consequently, estradiol levels. Consistent with lower estradiol level in VDD situations (whether calcium was normal or not), we recorded reduced CYP19A1 aromatase expression and higher testosterone levels. When both VitD and Ca were low (VitD−Ca−), we also found that progesterone was significantly lower. In line with our observation, increased testosterone has been shown to suppress GnRH secretion, leading to lower LH and FSH levels, thus disrupting follicular maturation39,40,41. It should be noted that a tonic level of LH is required to induce testosterone, while the conversion of testosterone to estrogen depends on FSH which regulates CYP19A1 activity. A somewhat similar situation has recently been reported in a mouse model of PCOS, in which granulosa cells respond to advanced glycation end (AGE) products by reducing estradiol, increasing testosterone concentration and reducing progesterone42,43,44,45. This is also consistent with observations of negative interactions between AGEs and VitD46,47. Our data are similarly in line with previous reports showing that high testosterone levels and low VitD were associated with hormonal imbalance in PCOS explaining irregular menstrual cycles, fertility problems, and excessive hair growth (hirsutism)48,49,50,51. The fact that the effects observed in groups of animals with VDD were corrected only by VitD supplementation and not by normalization of calcium levels underlines the importance of VitD’s genomic effect on follicular development rather than its calciotrophic effect. A clinical extrapolation that might follow from our study is that vitamin D levels should be checked in people with PCOS and, if necessary, supplemented accordingly. In addition, people with PCOS should avoid diets promoting AGEs generation that increases testosterone levels knowing that it is well established that testosterone can increase renal calcium clearance52. Thus, VDD and hypocalcemia may work hand in hand in PCOS sufferers to exaggerate the manifestations of this syndrome.

In the case of VitD excess (VDO animal groups), we showed that serum LH, FSH and testosterone levels were increased significantly, while estradiol and progesterone levels remained surprisingly unchanged. In these VDO animals, CYP19A1 expression remained, while 3ßHSD was greatly reduced. This peculiar observation may suggest that VitD, via a previously unknown pathway, has the ability to increase the conversion of testosterone to estradiol, despite low 3ßHSD expression.

Other studies have investigated the effect of VDD on female reproductive performance, either by knockdown of the VitD receptor (VDR-KD)26, or by knockdown of CYP27b1 activity, which converts the VitD precursor calcidiol to the active hormone calcitriol10,53 or else, by a VitD -deficient diet54,55 but without UV restriction and without taking calcium into account. Our experimental model is more complete and more precise. Furthermore, in our experimental model, paricalcitol treatment stimulates the CP24A activity, which converts the active VitD form into its inactive form. Consequently, via VitD deprivation, paricalcitol treatment and UV limitation, all sources of active VitD are depleted. This is not the case in the other models reported, which may explain why our data correspond fairly well to what has been reported previously, with the exception of the changes we recorded in serum LH and FSH levels. This reinforces the idea that VitD, via pathways that now need to be investigated, has direct or indirect actions on GnRH, as well as on the synthesis and secretion FSH and LH.

One of the limitations of our study is the lack of exploration of other endocrine pathways that could provide a better understanding of the complex and pleiotropic actions of VitD on mammalian physiology. In addition, it would have been interesting to explore further the link between vitamin D, steroidogenesis and inflammation or one of its counterparts, oxidative stress56. It has been suggested that VitD oxidation has a negative impact on the immune system and that this exacerbates inflammatory responses, an observation that was brought forward during the last SARS-CoV2 pandemic where VDD patients were associated with more severe inflammatory symptoms57. In this context, it would be interesting to monitor systemic inflammatory markers in VDD and VDO models.

In conclusion, low calcium intake or/and calcium-deficiency represent a minor challenge to follicular development. VDD and VDO, on the other hand, have a much broader and more profound impact on follicular development and reproductive performance. This may suggest that, in women facing infertility, VitD measurement could be relevant and, if necessary, balanced supplementation could be undertaken. Our findings, although obtained from an animal model, are likely to be relevant to human reproductive health, particularly with regard to dietary supplementation guidelines. They underline the idea that caution should be exercised when VitD supplementation is considered, as VDO can be as problematic as VDD.

Methods

Ethics and animals

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Royan Institute, Tehran, Iran (IR.ACECR.ROYAN.REC.1399.083). All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines established by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Royan Institute. Also, the manuscript follows the recommendations in the ARRIVE guidelines.

Media and reagents

All chemicals and media used in this study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and Gibco (Grand Island, NY), unless otherwise indicated.

Experimental design: animal groups and VDO/VDD induction

A total of 195 female NMRI mice, aged 4–5 weeks and weighing 20–35 g, were used in this study. Mice were housed in standard cages maintained at 22 ± 1 °C, 55 ± 5% humidity and 12/12 h cycle of light and darkness with standard diet containing 0.67% phosphorus, 1% calcium and 2200 IU vitamin D3/kg/day for 10 days. The mice were allowed free access to water and diet. At the end of this period, five mice were randomly selected and their serum vitamin D and calcium levels measured (Fig. 1). The remaining mice (N = 190, 38 mice/group) were then randomly divided into five groups as follows:

Group 1: control group in which mice were maintained on the standard diet.

Group 2: VDO and normal calcium mice (VitD+Ca) were gavaged with an additional 1000 IU VitD/day and fed a diet containing in fine 0.4% phosphorus, 0.2% calcium and 2200 IU vitamin D3/kg for 4 weeks58.

Group 3: mice deficient in VitD and calcium (VitD−Ca−) were injected intraperitoneally with 32ng paricalcitol three times a week for one week. Mice were then maintained under UV-limited conditions on a special diet containing less than 8 IU/kg VitD, 1% calcium and 0.67% phosphorus59,60.

Group 4: VDD and normal calcium mice (VitD−Ca) were injected intraperitoneally with 32ng paricalcitol three times a week for one week. Mice were then maintained under UV-limited conditions on a special diet containing less than 8 IU/kg VitD, 2% calcium, 1.25% phosphorus and 20% lactose59,60.

Group 5: Normal VitD and calcium-deficient mice (VitD Ca−) were injected intraperitoneally with 20 µg zoledronic acid twelve times for four weeks. Mice were then maintained on a diet containing 2200 IU vitamin D3/kg, 0.2% calcium and 0.4% phosphorus61.

Vitamin D (Calcitriol) was obtained from Vitabiotics (Iran). Paricalcitol and zoledronic acid were obtained from AbbVie (USA) and Ronak (Iran), respectively. Paricalcitol increases the expression of CYP24A1, inducing the catabolism of endogenous VitD. Zoledronic acid is a bisphosphonate that increases bone volume and decreases blood calcium levels. For each group, in order to verify the establishment of the models, 3 mice were randomly selected and sacrificed on day 30 after treatment to assess serum VitD and calcium levels. In this study, for general anesthesia, a mixture of 75 mg.kg-1 of ketamine (10%) and 2.5 mg.kg-1 of xylazine (2%) were used for mice weighing between 25 and 30 g through intraperitoneal injection. Following the induction of anesthesia, the animals were humanely sacrificed through a process of complete blood removal from the heart. Death was confirmed by the cessation of both cardiac and respiratory functions. The remaining mice in each group (n = 35) were subjected to the same diet and conditions for the next 42 days, corresponding to two cycles of folliculogenesis. At the end of this period, 5 mice were randomly selected from each group to assess their vitamin D, calcium, serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. Mice left in each group (n = 30) were used for evaluation of progesterone, estradiol, testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, as well as for quantitative qRT-PCR analysis of granulosa cells and histomorphometric evaluation on day 72.

Assessment of serum vitamin D, calcium, ALT, and AST levels

Serum levels of 25(OH)D3 and calcium were determined using standard laboratory procedures based on radio-immunoassays (RIA) obtained from Pars Azmoon Co. (Tehran, Iran). The normal serum reference values for the mouse species are 30ng/ml for VitD and 8.5 to 10.1 mg/dL for calcium. Enzymatic measurements were performed by photometric methods using Pars Test enzyme diagnostic kits for serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), in accordance with specific guidelines provided by the laboratory or research institution conducting the study. A Biotechnical Company 3000 BT auto-analyzer was used for this purpose. The normal serum range for ALT in female mice is between 13 and 48 IU/L, while that for AST is between 25 and 125 IU/L62.

Assessment of serum progesterone, estradiol, testosterone, LH, and FSH levels

After treatments or completion of two folliculogenesis cycles (42 days), all mice were sacrificed on day 72 and blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture. Serum samples were rapidly separated and frozen at -20 °C for subsequent measurement of progesterone, estradiol and testosterone levels using a TST assay (Siemens, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum FSH and LH levels were determined using the Architect-Abbott America (USA) luminescence immunoassay system. Serum LH and FSH levels measured ranged from 1 to 12.5 mIU/mL and from 1.4 to 15.4 mIU/mL, respectively13.

Histo-morphometric analyses

Ovarian tissues were subjected to histological examination by staining with Mayer’s hematoxylin-eosin solution (Merck-Serono in Darmstadt, Germany). Two experienced professionals blindly assessed the ovarian follicles and classified them into four categories on the basis of previously established criteria using a light microscope with ×400 magnification. Follicles were classified as follows: (1) primary follicles, consisting of a single layer of flattened pre-granulosa cells; (2) primary follicles, consisting of a single layer of granulosa cells, including cuboidal forms; (3) secondary follicles, containing at least two layers of cuboidal granulosa cells; and (4) antral follicles, comprising several layers of cuboidal granulosa cells and an antrum. Follicles with features such as granulosa cell dissociation, oocyte atrophy or atresia, irregular or dissociated cumulus oophorus, early antrum formation and vacuolated oocyte cytoplasm were classified as atretic follicles. The mean distribution of the total number of follicles per ovary, mean changes in the distribution of atretic follicles and the proportion of atretic follicles to the total number of follicles were evaluated and compared between groups. Results were reported as mean values and standard deviations63.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from granulosa cells harvested from mice using a spin column-based method involving the four main steps of lysis, binding, washing and elution designed to ensure efficient RNA extraction and purification. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using an ND-2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop). A high-capacity reverse transcription kit (PrimeScript RT with gDNA Eraser; Biotek) was used to synthesize cDNAs, and PCR reactions were performed as biological replicates in triplicate wells. qRT-PCR primers were designed using Primer 5.0 software (Premier, Canada) and are shown in Table 1.To normalize gene expression, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. qRT-PCR was performed using FastStart SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) and an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mouse Gapdh gene was used to normalize Ct values, and the 2-∆∆Ct method was applied for relative quantification of the CYP11A1, 3β-HSD and CYP19A1 genes (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Data on serum levels of progesterone, estradiol, testosterone and follicle number, as well as measurements of gene expression, were analyzed using Prism software with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s test. The semi-quantitative pathological observations were analyzed using Friedman’s non-parametric test, followed by the Mann-Whitney U test in pairs between the experimental groups. All data are presented as mean ± S.E.M., and the significance level was set at p ≤ 0.0001.

Data availability

Data supporting the manuscript’s findings can be found in the manuscript.

References

Holick, M. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 96 (7), 1911–1930 (2011).

Kaur, P., Mishra, S. K. & Mithal A.Vitamin D toxicity resulting from overzealous correction of vitamin D deficiency. Clin. Endocrinol. 83 (3), 327–331 (2015).

Marcinowska-Suchowierska, E. et al. Vitamin D toxicity–a clinical perspective. Front. Endocrinol. 550(9) (2018).

Veenstra, T. 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in the central nervous system of the rat embryo. Brain Res. 804 (2), 193–205 (1998).

Cui, X., Gooch, H., Petty, A., McGrath, J. J. & Eyles D.Vitamin D and the brain: genomic and non-genomic actions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 453, 131–143 (2017).

Muscogiuri, G. et al. Shedding new light on female fertility:the role of vitamin D. Reviews Endocr. Metabolic Disorders. 18, 273–283 (2017).

Safari, H., Hajian, M., Nasr-Esfahani, M. H., Forouzanfar, M. & Drevet, J. R. Vitamin D and calcium, together and separately, play roles in female reproductive performance. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 10470 (2022).

Kwiecinksi, G. G., Petrie, G. I. & DeLuca, H. F. 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 restores fertility of vitamin D-deficient female rats. Am. J. Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 256 (4), E483–E487 (1989).

Johnson, L. E. & DeLuca, H. F. Reproductive defects are corrected in vitamin D–Deficient female rats fed a high calcium, phosphorus and lactose diet. J. Nutr. 132 (8), 2270–2273 (2002).

Sun, W. et al. Defective female reproductive function in 1, 25 (OH) 2D-deficient mice results from indirect effect mediated by extracellular calcium and/or phosphorus. Am. J. Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 299 (6), E928–E935 (2010).

Johnson, L. E. & DeLuca, H. F. Vitamin D receptor null mutant mice fed high levels of calcium are fertile. J. Nutr. 131 (6), 1787–1791 (2001).

Fernando, M. et al. Vitamin D-binding protein in pregnancy and reproductive health. Nutrients 12 (5), 148 (2020).

Abasi, S. et al. Vitamin D deficiency affects the sex hormones and testicular function in mice. Andrologia 2024 (1), 6912179 (2024).

Christakos, S. & J. W., & Biology and mechanisms of action of the vitamin D hormone. Endocrinol. Metabolism Clin. 46 (4), 815–884 (2017).

Christakos, S., Dhawan, P., Porta, A., Mady, L. J. & Seth, T. Vitamin D and intestinal calcium absorption. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 347 (1–2), 25–29 (2011).

Fleet, J. C. & Schoch, R. D. Molecular mechanisms for regulation of intestinal calcium absorption by vitamin D and other factors. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 47 (4), 181–195 (2010).

Veldurthy, V. et al. Vitamin D, calcium homeostasis and aging. Bone Res. 4 (1), 1–7 (2016).

Van Cromphaut, S. J. et al. Duodenal calcium absorption in vitamin D receptor–knockout mice: functional and molecular aspects. Proc. National Academy of Sciences USA. 98(23), 13324–13329 (2001).

Liangpunsakul, S. & Chalasani, N. Serum vitamin D concentrations and unexplained elevation in ALT among US adults. Dig. Dis. Sci. 56, 2124–2129 (2011).

Ragab, D., Soliman, D., Samaha, D. & Yassin, A. Vitamin D status and its modulatory effect on interferon gamma and interleukin-10 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in culture. Cytokine 85, 5–10 (2016).

Liu, W. et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin D in tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (9), 2736 (2018).

Krishnan, A. V. & Feldman, D. Mechanisms of the anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions of vitamin D. Annual Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 51, 311–336 (2011).

Aramesh, S. et al. Does vitamin D supplementation improve ovarian reserve in women with diminished ovarian reserve and vitamin D deficiency: a before-and-after intervention study. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 21 (1), 1–5 (2021).

Moridi, I., Chen, A., Tal, O. & Tal, R. The association between vitamin D and anti-Müllerian hormone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 12, 1567 (2020).

Yin, W. W. et al. The effect of medication on serum anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) levels in women of reproductive age: A meta-analysis. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 22 (1), 1–14 (2022).

Kinuta, K. et al. Vitamin D is an important factor in Estrogen biosynthesis of both female and male gonads. Endocrinology 141 (4), 1317–1324 (2000).

Irani, M. & Merhi, Z. Role of vitamin D in ovarian physiology and its implication in reproduction: a systematic review. Fertility Steril. 102 (2), 460–468 (2014).

Naderi, Z., Kashanian, M., Chenari, L. & Sheikhansari, N. Evaluating the effects of administration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D supplement on serum anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) levels in infertile women. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 34 (5), 409–412 (2018).

Xu, J. et al. Vitamin D3 regulates follicular development and intrafollicular vitamin D biosynthesis and signaling in the primate ovary. Front. Physiol. 9, 1600 (2018).

Xu, Z. et al. Correlation of serum vitamin d levels with ovarian reserve markers in patients with primary ovarian insufficiency. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 12 (4), 4147–4153 (2019).

Merhi, Z. O. et al. Circulating vitamin D correlates with serum antimüllerian hormone levels in late-reproductive-aged women: women’s interagency HIV study. Fertility Steril. 98 (1), 228–234 (2012).

Xu, J., Hennebold, J. D. & Seifer, D. B. Direct vitamin D3 actions on rhesus macaque follicles in three-dimensional culture: assessment of follicle survival, growth, steroid, and antimüllerian hormone production. Fertility Steril. 106 (7), 1815–1820 (2016).

Dennis, N. A., Houghton, L. A., Pankhurst, M. W., Harper, M. J. & McLennan, I. S.Acute supplementation with high dose vitamin D3 increases serum anti-Müllerian hormone in young women. Nutrients 9 (7), 719 (2017).

Ibraheem, N. J., Al-Murshidi, M. M. H. & Hasan, W. S. Homeostasis events for serum ionized calcium accompanied by Anti-Mullerian hormone in some women with primary infertility in Babylon Province. J. Univ. Babylon. Pure Appl. Sci. 27 (2), 7–16 (2019).

Holzer, I. ea al. Parameters for calcium metabolism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome who undergo stimulation with letrozole: a prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med.. 11(9), 2597 (2022).

Bednarska-Czerwińska, A., Olszak-Wąsik, K., Olejek, A., Czerwiński, M. & Tukiendorf, A. Vitamin D and anti-Müllerian hormone levels in infertility treatment: the change-point problem. Nutrients 11 (5), 1053 (2019).

Bates, G. W. & Bowling, M. Physiology of the female reproductive axis. Periodontology 61(1), 89–102(2013). (2000).

Rosner, J., Samardzic, T., Sarao, M. S. & Physiology female reproduction. (2019).

Nassar, G. N., Leslie, S. W. & Physiology testosterone. (2018).

Pielecka, J., Quaynor, S. D. & Moenter, S. M.Androgens increase gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing activity in females and interfere with progesterone negative feedback. Endocrinology 147 (3), 1474–1479 (2006).

Pitteloud, N. et al. Inhibition of luteinizing hormone secretion by testosterone in men requires aromatization for its pituitary but not its hypothalamic effects: evidence from the tandem study of normal and gonadotropin-releasing hormone-deficient men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 93 (3), 784–791 (2008).

Garg, D. & Merhi, Z. Relationship between advanced glycation end products and steroidogenesis in PCOS. Reproductive Biology Endocrinol. 14, 1–13 (2016).

Homer, M. V., Rosencrantz, M. A., Shayya, R. F. & Chang, R. J. The effect of estradiol on granulosa cell responses to FSH in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reproductive Biology Endocrinol. 15, 1–6 (2017).

Kuyucu, Y., Sencar, L., Tap, Ö. & Mete, U. Ö. Investigation of the effects of vitamin D treatment on the ovarian AMH receptors in a polycystic ovary syndrome experimental model: an ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Reprod. Biol. 20 (1), 25–32 (2020).

Behmanesh, N., Abedelahi, A., Charoudeh, H. N. & Alihemmati, A. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on follicular development, gonadotropins and sex hormone concentrations, and insulin resistance in induced polycystic ovary syndrome. Turkish J. Obstet. Gynecol. 16 (3), 143 (2019).

Bischof, M. G., Heinze, G. & Vierhapper, H. Vitamin D status and its relation to age and body mass index. Horm. Res. 66 (5), 211–215 (2006).

Irani, M., Minkoff, H., Seifer, D. B. & Merhi, Z. Vitamin D increases serum levels of the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in women with PCOS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 99 (5), E886–E890 (2014).

Wen, X., Li, D., Tozer, A. J., Docherty, S. M. & Iles, R. K. Estradiol, progesterone, testosterone profiles in human follicular fluid and cultured granulosa cells from luteinized pre-ovulatory follicles. Reproductive Biology Endocrinol. 8 (1), 1–10 (2010).

Yildizhan, R. et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in obese and non-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Archives Gynecol. Obstet. 280, 559–563 (2009).

Hahn, S. et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with insulin resistance and obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Experimental Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 114 (10), 577–583 (2006).

He, C., Lin, Z., Robb, S. W. & Ezeamama, A. E. Serum vitamin D levels and polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 7 (6), 4555–4577 (2015).

Hsu, Y-J. et al. Testosterone increases urinary calcium excretion and inhibits expression of renal calcium transport proteins. Kidney Int. 77 (7), 601–608 (2010).

Dicken, C. L. et al. Peripubertal vitamin D3 deficiency delays puberty and disrupts the estrous cycle in adult female mice. Biol. Reprod. 87 (2), 51–51 (2012).

Nicholas, C. et al. Maternal vitamin D deficiency programs reproductive dysfunction in female mice offspring through adverse effects on the neuroendocrine axis. Endocrinology 157 (4), 1535–1545 (2016).

Wan, T. et al. Vitamin D deficiency inhibits microRNA-196b-5p which regulates ovarian granulosa cell hormone synthesis, proliferation, and apoptosis by targeting RDX and LRRC17. Annals Translational Med. 9(24) (2021).

Masjedi, F. et al. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 197:105521 .

Chiodini, I. et al. Vitamin D status and SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 clinical outcomes. Front. Public. Health 22(9),736665 .

Carlsson, A. & Lindquist, B. Comparison of intestinal and skeletal effects of vitamin D in relation to dosage. Acta Physiol. Scandinavia. 35 (1), 53–55 (1955).

Stavenuiter, A. et al. A novel rat model of vitamin D deficiency: safe and rapid induction of vitamin D and calcitriol deficiency without hyperparathyroidism. Biomed. Res. Int. (2015).

Duarte, I., Rotter, A., Malvestiti, A. & Silva, M. The role of glass as a barrier against the transmission of ultraviolet radiation: an experimental study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 25 (4), 181–184 (2009).

Huja, S. S., Fernandez, S. A., Phillips, C. & Li, Y. Zoledronic acid decreases bone formation without causing osteocyte death in mice. Arch. Oral Biol. 54 (9), 851–856 (2009).

KURAI, K., IINO, S., OKA, H., TSUDA, F. & NAITO, S., & Clinical utility of a simple quantitative determination of hepatitis B e antigen. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3 (6), 593–599 (1988).

Anvari, S. S., Dehgan, G. & Razi, M. Preliminary findings of platelet-rich plasma-induced ameliorative effect on polycystic ovarian syndrome. Cell. J. (Yakhteh). 21 (3), 243 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies. We would like to thank the Royan Biotechnology Institute (Isfahan, Iran) for allowing us to access their facilities to carry out this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“H.S. performed the experimental part. M.H. and N.T. helped with the experiments and supervised work. M.H., M.H.N-E. and H.S. participated in study design, data collection and evaluation, drafting and statistical analysis. M.R. participated in data collection, evaluation and statistical analysis. M.H.N-E., M.H. and J.R.D. designed and wrote the manuscript also participated in the finalization of the manuscript and approved the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.”

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Safari, H., Hajian, M., Tanhaeivash, N. et al. Consequences of vitamin D deficiency or overdosage on follicular development and steroidogenesis in Normo and hypo calcemic mouse models. Sci Rep 15, 14278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99437-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99437-3