Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths globally, owing to its high recurrence rate of 50 to 70% within five years. Despite known associations of certain DNA damage and repair (DDR) genes with tumor recurrence and drug resistance, a comprehensive understanding of DDR pathways’ role in predicting HCC recurrence and therapeutic responses remains elusive. Addressing this gap could offer significant advancements in prognostic and therapeutic strategies for HCC. This study used 769 RNA sequencing samples from public datasets and 53 samples from Xiangya Hospital for DDR model training and validation. It came out that DDR pathways were significantly enriched in samples with P53 mutations. Next, among the 173 combinations of algorithms and parameters, CoxBoost + RSF, Lasso [fold = 10] + RSF, and Lasso [fold = 50] + RSF demonstrated the best performance. The average AUC values of 1 to 5 years and the average concordance index (C-index) value were around 0.7. The risk scores were increased in tumors with recurrence, P53 mutation, and higher TNM stages. High-risk groups, characterized by enriched DDR pathways, exhibited lower CD8 + T cell infiltration and poorer responses to immunotherapy using atezolizumab and bevacizumab, emphasizing the potential of DDR signatures as valuable prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers. In conclusion, the DDR signatures associated with P53 mutations can predict recurrence and therapeutic response in HCC, highlighting their potential as prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major contributor to cancer-related deaths globally1, with alarmingly high postoperative recurrence rates of 50% to 70% within five years2. While the clinical characteristics influencing HCC recurrence risk are well-documented3,4,5, the molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. This gap in knowledge impedes the development of effective postoperative strategies to reduce recurrence risk. Current adjuvant target therapies, including sorafenib, had failed to improve recurrence-free survival (RFS) in HCC6. Similarly, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization showed limited efficacy in preventing postoperative recurrence7. Although combining atezolizumab and bevacizumab has significantly extended overall survival (OS) in advanced HCC8,9, it has been less effective in prolonging RFS in the whole population of resectable HCC tumors with high recurrence risk10. Traditional immune therapy biomarkers such as programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, tumor mutational burden, and microsatellite instability, offered limited predictive value for HCC treatment outcomes11. This underscored an urgent need for novel molecular panels to better predict postoperative recurrence and inform treatment strategies.

P53 played a crucial role in the initiation and progression of tumors12,13,14, primarily through the activation of DNA damage and repair (DDR), inhibition of the cell cycle, and promotion of apoptosis15. P53 mutations were associated with HCC recurrence, leading to shorter OS and RFS among patients16. DDR was essential for repairing gene mutations and maintaining genomic stability17,18,19,20. Limited evidence suggested that DDR promote tumor recurrence. For example, DDR-induced reactivation of Octamer-Binding transcription factor 4 led to tumor recurrence21 , and upregulation of DDR genes in glioblastoma promoted tumor progression and recurrence22. Interestingly, defects in DDR could activate anti-tumor effects via various mechanisms23,24,25. For instance, the accumulation of mutations caused by DDR defects generated tumor-specific neoantigens, which in turn activate anti-tumor immunity26. DNA damage-induced activation of the cGAS-STING pathway fostered type I IFN signaling and enhanced anti-tumor immune responses27,28. DNA damage could also lead to increased expression of PD-L129,30 , and triggered immune responses through cell death signals31. Therefore, molecules in the DDR pathway had the potential to serve as predictive markers for immunotherapy32.

Molecular models were widely utilized for predicting cancer prognosis and guiding treatment options33,34,35. With advancements in machine learning, combining various algorithms and selecting the most effective ones are crucial for enhancing model performance36,37. In this study, we applied 173 distinct combinations of machine learning algorithms to datasets from TCGA-LIHC, PLANET, GSE76427, GSE14520, and the Xiangya cohort. Our model was designed to predict HCC recurrence and treatment response by leveraging DDR signatures associated with P53 mutations. Our analysis explored the relationship between DDR signatures and factors such as the immune microenvironment, drug sensitivity and responsiveness to immunotherapy. These findings highlighted the potential of DDR signatures as prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers in HCC.

Material and methods

Collection and sequence of clinical HCC samples

In this study, we collected frozen tumor tissues from 53 HCC patients who underwent resection at Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, between 2017 and 2020. All of them had a confirmed diagnosis of HCC without any other primary tumors, had not received any treatment prior to surgery, and had not undergone postoperative immunotherapy. A follow-up was conducted to monitor RSF, with the follow-up endpoint being August 2024. These patients served as a validation cohort for our model. Additionally, we collected HCC tissues for Cytometry by Time-Of-Flight (CyTOF) and RNA sequencing from 16 patients, which were reported in our previous article38. The RNA sequencing data were supposed to be used in calculating the DDR model-derived risk score for each sample. And the matched CyTOF data were to be used in assessing intra-tumoral immune cell infiltration between the high and low-risk groups. The collection and handling of clinical specimens were approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number: 202401014). Samples meeting quality control standards were sequenced on the BGI platform, with a sequencing depth of 10G, producing raw FASTQ data. The data were processed using fastp (version 0.20.1) to remove adapters and low-quality reads, yielding clean data. Hisat2 (version 2.2.1) was used for aligning to the GRCh38 reference genome, and featureCounts (version 2.6.0) was employed to obtain read counts, which were then normalized to TPM and log2 transformed.

Public data collection and batch effect removal

For recurrence analysis, publicly available transcriptomic sequencing data were gathered from tumor resection specimens of HCC patients, including datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC), PLANET, GSE76427, and GSE14520. Clinical data, mutation information, and bulk RNA sequencing raw expression files for the TCGA-LIHC cohort were retrieved from https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov. The gene expression matrix was normalized to TPM and log2 transformed. Samples with P53 mutations, identified as single nucleotide polymorphism or deletion, were annotated as P53-mutant, while others were labeled as P53-wild type. From the initial 377 samples, those without recurrence time and those within non-primary tumors were excluded, resulting in 364 samples for further analysis. For the PLANET cohort39, clinical information and raw expression files were acquired from https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/PLANET_cohort/23732370. Average expression was calculated when multiple tumor samples were available for a single patient, followed by TPM normalization and log2 transformation. Samples missing recurrence time and those categorized as non-primary tumors were excluded, resulting in 55 samples for downstream analysis. Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data with the accession numbers of GSE76427 and GSE14520 were downloaded from GEO database40,41. After excluding samples with missing recurrence times, 108 and 242 samples were retained from GSE76427 and GSE14520, respectively. Each dataset had low-variance genes with an inter-sample variance below 0.2 removed. Batch effects were assessed using principal component analysis (PCA) and removed using the ComBat method from the sva package to minimize technical variation and enhance data consistency and comparability.

For analysis of therapy response, we applied the HCC transcriptomic sequencing data with therapy response information from the European Genome-phenome Archive, with dataset ID EGAD00001008128 and EGAD0000100813042. EGAD00001008128 contains raw RNA sequencing data from tumor samples of 358 patients who participated in the GO30140 (NCT02715531) phase 1b or IMbrave150 (NCT03434379) phase 3 trials and received treatment with either atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab, atezolizumab alone, or sorafenib. EGAD00001008130 contains therapy response and survival outcome. These raw data were processed using fastp (version 0.20.1) to remove adapters and low-quality reads, yielding clean data. Hisat2 (version 2.2.1) was used for aligning to the GRCh38 reference genome, and featureCounts (version 2.6.0) was employed to obtain read counts, which were then normalized to TPM and log2 transformed.

Enrichment analysis and survival analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2). Gene sets related to DNA damage repair were obtained from MSigDB43, enriched through Gene Ontology44, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes45, Reactome46, and WikiPathways, along with gene sets summarized by Michele Olivieri et al.47, aggregating to a total of 430 gene sets. GSEA enrichment analysis was conducted using GSEA (version 4.3.3). Gene sets with an FDR < 25% and nominal p-value < 5% were considered significantly enriched, and the genes within these significant gene sets were subjected to univariate Cox regression analysis. RFS-related univariate Cox regression analysis was performed using the survival package. Genes with a Cox regression p-value < 0.05 in both the training and independent validation cohorts were intersected to identify prognostic genes significantly associated with RFS for subsequent model development. The survival and survminer packages were used to generate Kaplan–Meier plots illustrating the relationship between model risk scores and survival probability. For significant genes in the model, enrichment analysis was conducted using Enrichr-KG (maayanlab.cloud), and chord diagrams were drawn using the circlize package to depict the pathway-gene relationships and biological functions.

Model training and validation

The TCGA-LIHC cohort was used as the training set, PLANET as validation set 1, GSE76427 and GSE14520 combined as validation set 2, and the Xiangya cohort as an independent validation set. A total of 10 machine learning algorithms were integrated: CoxBoost, Random Survival Forests (RSF), Lasso, stepwise Cox, Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Ridge, Elastic Net (Enet), SuperPC, survival-support vector machines (survival-SVMs), and plsRcox. These algorithms were widely used for published survival models37,48,49,50. By adjusting cross-validation folds, stepwise regression directions, and penalty terms, 173 algorithm combinations were generated. These combinations were used to train 173 prognostic models on the training set. The pROC and ggplot2 packages facilitated the computation and visualization of AUC heatmaps for 1 to 5 years and calculated the concordance index (C-index) of the models. The mosaic::zscore function of the mosaic package was used to standardize risk scores within each cohort. The mosaic::zscore function automatically transformed the data into a standard normal distribution (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1). Samples with risk scores higher than cohort mean were divided into the high-risk group, while the others were in the low-risk group. The survminer package was employed to illustrate survival probability differences between high and low-risk groups using Kaplan–Meier (KM) plots. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted using the survival package, with forest plots drawn using the forestplot package to evaluate the independent predictive effect of risk scores on RFS. The ggplot2 package generated bar plots showcasing the most important features in the random forest model.

Immune infiltration algorithms and CyTOF analysis

Four immune microenvironment scoring methods—ESTIMATE51, xCELL52, IPS53, and TIDE54—were applied to score the training and validation sets. Five immune infiltration algorithms—xCELL, CIBERSORT55, CIBERSORT absolute, MCPcounter, and TIDE—were used for differential analysis of immune-infiltrating cells between high and low-risk groups in the training set. CyTOF was conducted by SendiBio, as described in our previous publication38. Cell clustering and t-SNE dimensionality reduction of CyTOF data were performed using FCS Express 7.

Drug sensitivity analysis

The oncoPredict R package was utilized to predict drug responses for each sample56. CTRP was used for RNA-seq data, and GDSC2 for microarray data. Drug sensitivity scoring was performed for both high and low-risk groups in the training and validation sets, with significance tested using the Wilcoxon test. The intersection of differential drugs in each cohort provided representational differential drugs. Violin plots illustrated the inter-group differences in drug sensitivity scores, while scatter plots showcased the correlation between drug sensitivity scores and risk scores.

Cell lines and cell cultures

LO2 (normal liver cell line), Hep3B, HCCLM3, HepG2, and MHCC97H (Human liver cancer cell line) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Typical Culture Preservation Center Cell Bank. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco Modified Eagle culture-medium (DMEM) (10–013-CVRC, Corning, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China) containing 10% FBS (SA301.02, Cellmax, Beijing, China) in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. All cells were free of mycoplasma contamination.

Cell count kit-8 (CCK-8) proliferation test

Cell proliferation was detected by CCK-8 assay (BS350B, Biosharp, Beijing, China); cells of logarithmic growth stage (2000 cells per well) were inoculated on 96-well plates. At specific time points (24, 48, 72 h), cells were added with CCK-8 solution 10 μL per well and incubated at 37 ℃ for two hours. The absorbance value at 450 nm was calculated by spectrophotometry three times every 24 h.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA is extracted using AG RNAex Pro reagent (AG21101, AG, Changsha, Hunan, China). The RNA concentration was quantified using NanoDrop™ One. 1.5 μg RNA was transferred to cDNA using the Evo M-MLV RT Kit (AG11728, AG, Changsha, Hunan, China). The SYBR Green PCR Mastermix Kit (AG11718, AG, Changsha, Hunan, China) was used to amplify PCR on QuantStudio™ real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR software. 2-ΔΔCt computes values for quantitative analysis. Primers are as follows:

POLR3G:

F: TAGGGAGCAGTGCCTTTCAG.

R: GTGGGGGTGGTTTCAACACT.

GAPDH:

F: CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT.

R: GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT.

Using GAPDH as the internal parameter, the 2 − ΔΔCt value was calculated for quantitative analysis.

Western blotting

Extract total protein with radio immunoprecipitation assay buffers containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. After separation by SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane at 250 mA for 90 min and blocked with 5% skim milk. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody at 4℃ for 12 h. Subsequently, the membrane and the secondary antibody were incubated at 37℃ for 60 min. After 3 washes with TBST, the ChemiDoc XRS Image system detected the signal. Finally, the protein was quantitatively analyzed using Image J software. Antibodies used were as followed: POLR3G (03G240603, 1:1000, AWA40802, Abiowell, Changsha, Hunan, China), β-Tubulin (21,000,383, 1:20,000, HRP-66240, Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China).

EdU detection

3000 cells were inoculated on a 96-well plate. Cells were maintained with 20 μM EdU (C0078S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 2 h and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were then treated with 50 μl Click Additive Solution. For 30 min, washed with 0.5% Triton X-100 (AWH0299a, Abiowell, Changsha, Hunan, China), stained with DAPI solution (AWC0292, Abiowell, Changsha, Hunan, China), and images were collected under the microscope.

Small interference RNA (siRNA) transfection

Sequentials were ordered from OBIO (https://www.obiosh.com/) for siRNA transfection targeting POLR3G, and Lipo3000 (L3000-015, Invitrogen, California, USA) was utilized for transfection. The specific sequences for each siRNA are as follows:

Si-NC.

Forward: UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT.

Reverse: ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT.

Si-POLR3G.

Forward: UAAAGGAAGAGGACGUGCUGCUUAUTT.

Reverse: AUAAGCAGCACGUCCUCUUCCUUUATT.

Transwell migration

Cell migration experiments were performed in a 24-well transwell plate (8.0 µm pore size, Corning Life Sciences, Costar, USA). Stably transduced cells were treated with trypsin and adjusted to 3 × 105 cells/mL after counting. Then, 600 µL of complete medium containing 30% (v/v) serum was added to the lower chamber, 200 µL of the cell suspension was added to the upper chamber, and the cells were cultured for 48 h. The cells in the upper chamber were removed, and the cells remaining on the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (AWI0056b, Abiowell, Changsha, Hunan, China). After staining with 0.1% crystal violet solution (AWI0364a, Abiowell, Changsha, Hunan, China), the cells were observed under a microscope and imaged. All experiments were repeated three times.

Statistics analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2) and GraphPad Prism 10. The Kruskal–Wallis test was utilized for multiple group comparisons. This was followed by Dunn’s post-hoc comparisons between subgroups, whose p-value was adjusted by the Bonferroni correction. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for two-group comparisons. The Kaplan–Meier method was applied to estimate survival probabilities, with the log-rank test used for comparing survival curves between different groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to evaluate the impact of variables on survival time. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the linear relationship between variables and quantify the strength of their association. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

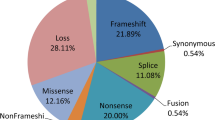

DDR genes associated with P53 mutations in HCC recurrence

Our methodology was illustrated in Fig. 1. Five pathway enrichment methods, including Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment, Wikipathway pathway enrichment, Reactome pathway enrichment, Gene Ontology pathway enrichment, and Michele Olivieri et al. pathway enrichment. The findings consistently indicated that P53-mutant HCC exhibited a higher enrichment in DDR pathways, particularly in mismatch repair, homologous recombination, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, and in the regulation of DNA repair gene transcription by P53 (Supplementary table 1). In contrast, there was no notable enrichment of genes linked to DDR in wild-type P53 HCC (Fig. 2A). After the elimination of batch effects from different datasets, the distribution of each data is scattered and uniform, indicating that the data of various data sets are consistent and comparable. As a result, the analysis outcomes can be deemed relatively more reliable (Fig. 2B). Univariate Cox regression analysis was carried out on genes that exhibited significant enrichment in the DDR pathway across both the training and validation datasets. Subsequently, 106 prognostic genes that displayed a substantial association with RFS were pinpointed and incorporated into the model construction (Fig. 2C; Supplementary table 2).

Study design flowchart. The TCGA-LIHC dataset was utilized as the training set, while the PLANET, GEO, and the Xiangya cohorts were employed as the validation sets. To identify prognostic genes associated with RFS, univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted on DDR pathway genes notably enriched in P53-mutated samples, identifying 106 candidate genes. Evaluation metrics, such as the AUC and C-index, were used to assess the performance of 173 algorithm and parameter combinations. The optimal algorithm combination was selected to generate DDR signatures with the highest predictive significance for RFS. Subsequently, the HCC patient cohort was stratified into high and low DDR groups for comparative analysis. Differences in survival probability, clinical characteristics, microenvironment scores, immune cell infiltration, drug sensitivity patterns, and response to immunotherapy were assessed between these two groups.

DDR genes associated with P53 mutations in HCC recurrence. (A) GSEA map of five pathway enrichment methods with P53 mutation as a grouping in the training and validation set. (B) Pre-batch and post-batch effects PCA plots in the training and validation sets. (C) Venn diagram of genes significantly associated with RFS in training and validation sets.

Development and validation of DDR model for HCC recurrence

We identified 106 DDR genes in the training and validation sets through univariate Cox regression analysis based on RFS. We employed 173 combinations of algorithms and parameters to construct predictive models and evaluate the AUC and C-index over 1 to 5 years (Fig. 3A-B) (Supplementary table 3). CoxBoost + RSF, Lasso [fold = 10] + RSF, and Lasso [fold = 50] + RSF were among the best models, with an average AUC and average C-index around 0.7. The DDR genes set includes BCL7A, HDAC2, PRKCQ, NPM1, ERCC6, UBB, RAD54B, CCT2, MAPKAPK5, PSMD9, NUP85, CCNB1, POLR3G, EEF1E1, CHD1L, GTF3C3, SFN, THOC5, TTF2. The weight of each gene in the model was examined using the top three algorithms and parameters, revealing consistent results across all three algorithmic combinations. This indicated the relative reliability of our results; consistent findings were observed when employing diverse combinations of algorithms (Fig. 3C). The pathway analysis of the DDR genes set indicated that the primary enriched pathways were the P53 signaling and nucleotide excision repair pathways (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, we extensively summarized the published models and AUC values for predicting HCC recurrence utilizing various molecular features (Supplementary table 4).

Development and validation of DDR model for HCC recurrence. (A) Heat map of AUC values and 3-year average AUC values of the top 60 algorithms and parameter combinations in the training and validation sets. (B) Heat maps of 1-, 2-, 4-, and 5-year AUC and c-index values for the top 10 algorithms and parameter combinations in the training and validation sets. (C) The lollipop plot showed the three optimal model combinations to score the importance of DDR genes. (D) The chord plot showed the related pathways enriched by DDR genes.

The high-risk group presented worse clinical prognosis

To better understand the influence of risk scores on clinical features and prognosis, we analyzed RFS and clinical characteristics within both the high and low-risk groups. We utilized the LASSO [fold = 10] + RSF algorithm to conduct Kaplan–Meier curve analysis and log-rank tests across the TCGA, PLANET, and GEO cohorts. Consistently, the high-risk group showed a lower survival rate in all three cohorts. The Hazard Ratios were 115, 3.5, and 2.3 in the TCGA, PLANET, and GEO cohorts, respectively, with significant differences in log-rank P-values (log-rank P < 0.0001, log-rank P = 0.0030, and log-rank P < 0.0001). This implied that our risk score was predictive of HCC prognosis (Fig. 4A). Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that high-risk group was a significant risk factor (Fig. 4B), and further multivariate Cox regression analyses emphasized that the high-risk group was an independent poor prognostic factor (Hazard Ratios (95% CI): 100.9 (48.79,208.7)) (Fig. 4C). Further analysis of clinical features showed that the high-risk group was linked to recurrence type, pathological grade, stage, T stage, and presence of P53 mutation, yet it displayed no significant associations with recurrence site, N stage, M stage, age, or gender (Fig. 4D-L).

The high-risk group presented worse clinical prognosis. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of RFS based on the log-rank test in TCGA, PLANET, and GEO for the high and low-risk groups. (B) Forest plot of univariate Cox regression of risk scores and clinical parameters. (C) Forest plot of multivariate Cox regression of risk scores and clinical parameters. (D) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and type of recurrence. (E) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and recurrence tissue. (F) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and pathological grades. (G) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and stages. (H) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and T.stage. (I) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and N.stage. (J) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and P53 mutation type. (K) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and gender. (L) Combined violin and box plots of risk scores and age.

The high-risk group demonstrated lower microenvironment score and decreased CD8 + T cell infiltration

ESTIMATE Score, xCELL Score, IPS, and TIDE were used to evaluate the immune infiltration of high and low-risk groups in the model (Fig. 5A; Supplementary table 5). Elevated ESTIMATE, xCELL, and IPS scores were linked to increased immune infiltration, whereas higher TIDE scores were associated with a poorer response to immunotherapy. In the training set and the two verification sets, the high-risk group was related to low StromalScore (ESTIMATEScore), ESTIMATEScore (ESTIMATEScore), StromaScore (xCELL Score) and MicroenvironmentScore (xCELL Score) and high dysfunction (TIDE Score). In the training set and only one validation set, the high-risk group was associated with low ImmuneScore (xCELL Score) scores and high Exclusion (TIDE Score)) and TIDE (TIDE Score)). In the training set alone, the high-risk group was associated with low ImmuneScore (ESTIMATE Score), MHC (IPS), and IPS (TIDE) scores. In the PLANET cohort, we observed no significant differences in Exclusion and TIDE scores between high and low-risk groups, which may be attributed to the cohort’s limited sample size (N = 55). However, analysis of the two larger cohorts (TCGA and GEO) revealed significant differences in Exclusion and TIDE scores, suggesting enhanced immune exclusion in high-risk groups. This indicates that the high-risk group resembled cold tumors and may have exhibited limited responsiveness to immune checkpoint monoclonal antibodies like anti-PD1, whereas the low-risk group may potentially benefit from immunotherapy. In the TCGA cohort, we applied five immune infiltration algorithms, including xCELL, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT absolute, MCPcounter, and TIDE. Among these, four algorithms consistently indicated lower infiltration of CD8 + T cells in the high-risk group (Fig. 5B; Supplementary table 5). RNA sequencing of 16 HCC patients in the Xiangya cohort was used to calculate the DDR model-derived risk score for each sample. Subsequently, matched CyTOF was used to assess the difference in immune infiltration between the high and low-risk groups. CyTOF analysis demonstrated decreased immune cell infiltration in the high-risk group. Subsequent examination of cell subsets revealed reduced CD8 + T cell infiltration and an elevated level of depleted CD8 + T cells in the high-risk group (Fig. 5C-F; Supplementary table 5). This indicates that the low-risk group could potentially respond well to immunotherapy, whereas the high-risk group may exhibit characteristics resembling a cold tumor phenotype.

The high-risk group demonstrated lower microenvironment score and decreased CD8 + T cell infiltration. (A) Box plots of four immune infiltration scores in the high and low-risk groups in the training and validation set. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). (B) Box plot of the scores of five immune infiltration algorithms in the high and low-risk groups of the TCGA cohort. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). (C) CyTOF plot of Xiangya cohort of immune infiltration in the high and low-risk groups. (D) Quantitative analysis of the proportion of immune cells in the high and low-risk groups in the Xiangya cohort. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05). (E) CyTOF plot of Xiangya cohort of CD8 + T cell infiltration and exhausted CD8 + T cell infiltration in the high and low-risk groups. (F) Quantitative analysis of the proportion of CD8 + T cells and the proportion of exhausted CD8 + T cells in the high and low-risk groups of the Xiangya cohort. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05).

The high-risk group exhibited a poorer response to immunotherapy using Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab

Drug sensitivity scores were calculated for the high-risk and low-risk groups in a training set and two validation sets. The overlap of these scores pinpointed two specific drugs (MK-2206 and BI-2536) (Fig. 6A). The drug sensitivity scores for the two drugs revealed that the high-risk group in all three cohorts exhibited higher sensitivity to MK-2206, whereas the low-risk group demonstrated a stronger sensitivity to BI-2536. The sensitivity of MK-2206 was positively correlated with the risk scores in all three cohorts, suggesting that MK-2206 may be considered to increase the treatment effect in this subset of patients in the high-risk group; However, the correlation coefficient is limited (R2 = 0.08). The inverse correlation between the drug sensitivity and risk score of BI-2536 indicated its potential to improve treatment effectiveness in low-risk patient groups. However, it was worth noting that the correlation coefficient was moderate (R2 = 0.36) (Fig. 6B-C). The recurrence risk score model was utilized to evaluate the three drug regimens within the IMbrave150 and GO30140 cohorts. The analysis indicated a poorer prognosis for the high-risk group in the IMbrave 150 immunotherapy cohort (receiving Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab) (Fig. 6D-E; Supplementary table 5). This observation implied a potential resistance to immunotherapy using Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab within the high-risk group.

The high-risk group exhibited a poorer response to immunotherapy using Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab. (A) Drugs with significant differences in drug sensitivity scores between the high and low-risk groups were intersected in the three cohorts. (B) The drug sensitivity scores of MK − 2206 and BI − 2536 were compared in the high-low risk groups of the three cohorts. (C) Correlation analysis of risk score and drug sensitivity score between the high and low-risk groups. (D) Kaplan–Meier curves showed progression-free survival probability in the high and low-risk groups of the IMbrave150 and GO30140 cohorts. E. Kaplan–Meier curves showed overall survival probability in the high and low-risk groups of the IMbrave150 and GO30140 cohorts.

POLR3G promoted the proliferation and migration of HCC cells in vitro

One of core gene in the DDR genes set is POLR3G. We explored the expression and function of POLR3G in vitro in HCC. PCR and western blot results showed that POLR3G levels were significantly higher in HCC cell lines compared to LO2 cells (Fig. 7A-B). We chose the Hep3B and HCCLM3 cell lines, which exhibited relatively high POLR3G expression, for gene silencing and functional experiments. CCK-8 and EdU assays in both cell lines revealed decreased cell proliferation capacity upon POLR3G silencing (Fig. 7C-F). Transwell migration assays were carried out to validate the role of POLR3G in promoting migration in HCC. Consistently, the transwell migration tests demonstrated a notable decrease in the migratory capacity of Si-POLR3G-HEP3B and Si-POLR3G-HCCLM3 cells compared to the control group (Fig. 7G-H). In summary, our study revealed that POLR3G enhances the proliferation and migration of HCC cells in vitro.

POLR3G promoted the proliferation and migration of HCC cells in vitro. (A) POLR3G mRNA expression in normal liver cells and HCC cell lines. (B) POLR3G protein expression in normal liver cells and HCC cell lines. (C-D) CCK-8 suggested that the knockdown of POLR3G suppressed the proliferation of HCC cells. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (E–F) EdU suggested that the knockdown of POLR3G suppressed the proliferation of HCC cells. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05). (G-H) Transwell migration tests suggested that the knockdown of POLR3G suppressed the migration of HCC cells. The asterisks represented the statistical P-value (*P < 0.05).

Discussion

HCC is an aggressive and recurrent malignant tumor that often responds poorly to immunotherapy57. Identifying biomarkers that predict recurrence and immune efficacy is therefore essential to optimizing treatment strategies for those most likely to benefit.

In our study, we examined the role of DDR signatures related to P53 mutations in predicting HCC recurrence and response to immunotherapy. By employing datasets from TCGA-LIHC, PLANET, GSE76427, GSE14520, and the Xiangya cohort, we utilized 173 diverse combinations of machine learning algorithms to construct predictive DDR signatures. We analyzed microenvironment scores, immune cell infiltration, drug sensitivity analysis, and immunotherapy prognosis in both high and low-risk patient groups. POLR3G was a protein-coding gene that encoded a critical component of the RNA polymerase III complex and possessed chromatin-binding activity58. It localized primarily to the cytoplasm and nucleolus59. Recent studies have established POLR3G as a critical regulator of genomic stability through its direct involvement in homologous recombination-mediated DNA double-strand break repair60,61. These findings demonstrated POLR3G was essential for maintaining DNA repair fidelity. Accumulating evidence indicated that POLR3G played a pivotal role in driving the progression of multiple cancers, including bladder, breast, lung, and prostate cancer62,63,64,65. Based on these findings regarding POLR3G’s dual roles in DNA damage and repair response and oncogenesis, we investigated its expression and function in vitro for HCC.

Our analysis of public transcriptomic datasets revealed higher immune microenvironment and CD8 + T cell infiltration scores in the low-risk group compared to the high-risk group. These findings were confirmed by CyTOF results from the Xiangya cohort. Previous studies have shown that lower levels of tumor-infiltrating CD8 + T cells were associated with worse immunotherapy response66,67. Our analysis of the IMbrave150 immunotherapy cohort revealed poorer OS in the high-risk group, indicating a correlation between DDR and immunotherapy (Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab) resistance9. Targeting DDR might be a potential combination strategy for activating the tumor immune microenvironment and enhancing immunotherapy in HCC. For example, inhibitors of poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP), ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM), significantly up-regulated STING pathway to activate CD8 + T cells and enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD-L168,69,70,71,72. The inhibitor of ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) induced synthetic lethality in mismatch repair-deficient cells to augment immunotherapy response73.

Current post-surgery target therapies and immunotherapies for high-risk recurrent HCC remain ineffective. Trials like IMbrave050 and STORM failed to demonstrate significant prolongation of survival6,10 . In our study, MK-2206 and BI-2536 showed potential as therapeutic agents, with MK-2206 being more effective in the high-risk group and BI-2536 in the low-risk subset; however, this correlation needs validation in larger cohorts74,75.

Our model had several distinct advantages over existing molecular models in predicting HCC recurrence and therapy response. For instance, in predicting 1-year recurrence, our model achieved an average AUC value of 0.752, surpassing the earlier models whose AUC values ranged from 0.598 to 0.661. (Tang et al.76 microvascular invasion-related genes model, AUC = 0.655; Long et al.77 DNA methylation driver genes model, AUC = 0.661; Kong et al.78 recurrence-related genes model, AUC = 0.598; Wang et al.79 Seven core genes model, AUC = 0.616). Similar results were observed for the 2–5 years AUC values76,77,78,79. Another key strength of our approach lied in the application of 173 machine learning algorithm combinations, which offered more robust and reliable predictions. Moreover, unlike models validated solely on publicly available transcriptome data80,81,82, our model underwent validation with the Xiangya cohort, which significantly bolstered its clinical relevance and stability. Furthermore, unlike other models relying on TIDE algorithms instead of HCC immunotherapy cohorts to predict immunotherapy response83,84, we utilized real HCC immunotherapy cohorts to demonstrate the predictive value of our model.

While our study presented promising findings, it also had several limitations. Firstly, the analysis at the single-cell level is constrained due to the lack of single-cell transcriptome data with RFS information. Subsequent studies can pay attention to the collection of RFS information in single-cell sequencing experiment. Secondly, the study’s brevity limited our exploration of the functional roles of the genes involved in the models. To gain a comprehensive understanding, future research could investigate how these genes contribute to HCC recurrence and response to immunotherapy, elucidating their mechanisms of action. Thirdly, while MK-2206 and BI-2536 have shown potential as therapeutic agents for HCC, their roles were not comprehensively studied here. Future investigations should delve deeper into their mechanisms and efficacy, aiming to solidify their potential as viable drug targets for HCC treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study identified DDR signatures associated with P53 mutations to predict HCC recurrence and treatment response, highlighting their potential as prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term =), the PLANET cohort https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/PLANET_cohort/23732370, HCC transcriptomic sequencing data with therapy response information from the European Genome-phenome Archive, with dataset ID EGAD00001008128 and EGAD00001008130, the transcriptome and CyTOF data from Xiangya can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author with a formal request.

Code availability

All code generated for analysis is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Forner, A. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 391(10127), 1301–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30010-2 (2018).

Peter, R. et al. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 69(1), 182–236 (2018).

Chan, A. W. H. et al. Development of pre and post-operative models to predict early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. J. Hepatol. 69(6), 1284–1293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.08.027 (2018).

Li, T. et al. Positive HBcAb is associated with higher risk of early recurrence and poorer survival after curative resection of HBV-related HCC. Liver Int. 36(2), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12898 (2016).

Lee, S. et al. Effect of microvascular invasion risk on early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery and radiofrequency ablation. Ann. Surg. 273(3), 564–571. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003268 (2021).

Bruix, J. et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 16(13), 1344–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00198-9 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: A randomized controlled study. Clin. Cancer Res. 24(9), 2074–2081. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-2899 (2018).

Sadagopan, N. et al. Recent progress in systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25021259 (2024).

Finn, R. S. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382(20), 1894–1905. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1915745 (2020).

Yopp, A. et al. LBA39 updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave050: Phase III study of adjuvant atezolizumab (atezo)+ bevacizumab (bev) vs active surveillance in patients (pts) with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann. Oncol. 35, S1230 (2024).

Greten, T. F. et al. Biomarkers for immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20(11), 780–798. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00816-4 (2023).

Marei, H. E. et al. p53 signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 21(1), 703. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-021-02396-8 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Should mutant TP53 be targeted for cancer therapy?. Cell Death Differ. 29(5), 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-022-00962-9 (2022).

Hassin, O. et al. Drugging p53 in cancer: one protein, many targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22(2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00571-8 (2023).

Vaddavalli, P. L. et al. The p53 network: Cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in cancer and aging. Trends Gene.t 38(6), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2022.02.010 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Alterations of TP53 are associated with a poor outcome for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 48(15), 2328–2338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.001 (2012).

Groelly, F. J. et al. Targeting DNA damage response pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 23(2), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00535-5 (2023).

Hopkins, J. L. et al. DNA repair defects in cancer and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dev. 36(5–6), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.349431.122 (2022).

Hoeijmakers, J. H. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 361(15), 1475–1485. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0804615 (2009).

Basu, A. K. DNA damage, mutagenesis and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19040970 (2018).

Filipponi, D. et al. DNA damage signaling-induced cancer cell reprogramming as a driver of tumor relapse. Mol. Cell 74(4), 651-663.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.002 (2019).

Yang, W. B. et al. Histone deacetylase 6 acts upstream of DNA damage response activation to support the survival of glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 12(10), 884. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-04182-w (2021).

Reisländer, T. et al. DNA damage and cancer immunotherapy: A STING in the tale. Mol. Cell 80(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.026 (2020).

Pan, D. et al. When DNA damage responses meet tumor immunity: From mechanism to therapeutic opportunity. Int. J. Cancer 155(3), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34954 (2024).

Jiang, M. et al. Alterations of DNA damage response pathway: Biomarker and therapeutic strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11(10), 2983–2994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.01.003 (2021).

Burrell, R. A. et al. Replication stress links structural and numerical cancer chromosomal instability. Nature 494(7438), 492–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11935 (2013).

Brzostek-Racine, S. et al. The DNA damage response induces IFN. J. Immunol. 187(10), 5336–5345. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1100040 (2011).

Heijink, A. M. et al. BRCA2 deficiency instigates cGAS-mediated inflammatory signaling and confers sensitivity to tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07927-y (2019).

Sato, H. et al. DNA double-strand break repair pathway regulates PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1751. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01883-9 (2017).

Permata, T. B. M. et al. Base excision repair regulates PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Oncogene 38(23), 4452–4466. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-019-0733-6 (2019).

Apetoh, L. et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat. Med. 13(9), 1050–1059. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1622 (2007).

Zhang, J. et al. Role of DNA repair defects in predicting immunotherapy response. Biomark. Res. 8, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00202-7 (2020).

Chen, Z. et al. A machine learning model to predict the triple negative breast cancer immune subtype. Front. Immunol. 12, 749459. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.749459 (2021).

Su, Y. et al. Colon cancer diagnosis and staging classification based on machine learning and bioinformatics analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 145, 105409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105409 (2022).

Chen, D. L. et al. Identification of key prognostic genes of triple negative breast cancer by LASSO-based machine learning and bioinformatics analysis. Genes (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13050902 (2022).

Swanson, K. et al. From patterns to patients: Advances in clinical machine learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell 186(8), 1772–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.035 (2023).

Chu, G. et al. Integrated multiomics analysis and machine learning refine molecular subtypes and prognosis for muscle-invasive urothelial cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 33, 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2023.06.001 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Comprehensive molecular classification predicted microenvironment profiles and therapy response for HCC. Hepatology 80(3), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1097/hep.0000000000000869 (2024).

Zhai, W. et al. Dynamic phenotypic heterogeneity and the evolution of multiple RNA subtypes in hepatocellular carcinoma: the PLANET study. Natl. Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwab192 (2022).

Grinchuk, O. V. et al. Tumor-adjacent tissue co-expression profile analysis reveals pro-oncogenic ribosomal gene signature for prognosis of resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 12(1), 89–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12153 (2018).

Roessler, S. et al. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 70(24), 10202–10212. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-2607 (2010).

Zhu, A. X. et al. Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Med. 28(8), 1599–1611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01868-2 (2022).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1(6), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology the gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet. 25(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.1.29 (1999).

Milacic, M. et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52(D1), D672-d678. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1025 (2024).

Olivieri, M. et al. A genetic map of the response to DNA damage in human cells. Cell 182(2), 481-496.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.040 (2020).

Skubleny, D. et al. The tumor immune microenvironment drives survival outcomes and therapeutic response in an integrated molecular analysis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 30(23), 5385–5398. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-23-3523 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Identifying squalene epoxidase as a metabolic vulnerability in high-risk osteosarcoma using an artificial intelligence-derived prognostic index. Clin. Transl. Med. 14(2), e1586. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.1586 (2024).

Qin, H. et al. Integrated machine learning survival framework develops a prognostic model based on inter-crosstalk definition of mitochondrial function and cell death patterns in a large multicenter cohort for lower-grade glioma. J. Transl. Med. 21(1), 588. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04468-x (2023).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3612 (2013).

Aran, D. et al. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 18(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-017-1349-1 (2017).

Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep. 18(1), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019 (2017).

Jiang, P. et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 24(10), 1550–1558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1 (2018).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12(5), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3337 (2015).

Maeser, D. et al. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab260 (2021).

Xu, F. et al. Immune checkpoint therapy in liver cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-018-0777-4 (2018).

Renaud, M. et al. Gene duplication and neofunctionalization: POLR3G and POLR3GL. Genome Res. 24(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.161570.113 (2014).

Kessler, A. C. et al. The nuclear and cytoplasmic activities of RNA polymerase III, and an evolving transcriptome for surveillance. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(21), 12017–12034. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1145 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. RNA polymerase III is required for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cell 184(5), 1314-1329.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.048 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. RNA polymerase III directly participates in DNA homologous recombination. Trends Cell Biol. 32(12), 988–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2022.06.007 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. POLR3G promotes EMT via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in bladder cancer. FASEB J. 37(12), e23260. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202301095R (2023).

Lautré, W. et al. The POLR3G subunit of human RNA polymerase III regulates tumorigenesis and metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14235732 (2022).

Park, C. R. et al. Regulating POLR3G by MicroRNA-26a-5p as a promising therapeutic target of lung cancer stemness and chemosensitivity. Noncoding RNA Res. 8(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncrna.2023.03.001 (2023).

Petrie, J. L. et al. Effects on prostate cancer cells of targeting RNA polymerase III. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(8), 3937–3956. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz128 (2019).

St Paul, M. et al. The roles of CD8(+) T cell subsets in antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 30(9), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2020.06.003 (2020).

Park, J. et al. Microenvironment-driven metabolic adaptations guiding CD8(+) T cell anti-tumor immunity. Immunity 56(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2022.12.008 (2023).

Sen, T. et al. Targeting DNA damage response promotes antitumor immunity through STING-Mediated T-cell activation in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 9(5), 646–661. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-18-1020 (2019).

Li, C. et al. ATM inhibition enhance immunotherapy by activating STING signaling and augmenting MHC Class I. Cell Death Dis. 15(7), 519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06911-3 (2024).

Reisländer, T. et al. BRCA2 abrogation triggers innate immune responses potentiated by treatment with PARP inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 3143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11048-5 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Niraparib activates interferon signaling and potentiates anti-PD-1 antibody efficacy in tumor models. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38534-6 (1853).

Hu, M. et al. ATM inhibition enhances cancer immunotherapy by promoting mtDNA leakage and cGAS/STING activation. J. Clin. Invest. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci139333 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. ATR inhibition induces synthetic lethality in mismatch repair-deficient cells and augments immunotherapy. Genes Dev. 37(19–20), 929–943. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.351084.123 (2023).

Agarwal, E. et al. Akt inhibitor MK-2206 promotes anti-tumor activity and cell death by modulation of AIF and Ezrin in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-145 (2014).

Steegmaier, M. et al. BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr. Biol. 17(4), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.037 (2007).

Tang, Y. et al. Identification and validation of a prognostic model based on three MVI-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18(1), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.66536 (2022).

Long, J. et al. DNA methylation-driven genes for constructing diagnostic, prognostic, and recurrence models for hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics 9(24), 7251–7267. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.31155 (2019).

Kong, J. et al. A genomic-clinical nomogram predicting recurrence-free survival for patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. PeerJ 7, e7942. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7942 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. A gene-based risk score model for predicting recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 21(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07692-6 (2021).

Xie, S. et al. Novel risk model based on angiogenesis-related lncRNAs for prognosis prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 23(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-023-02975-x (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Competing endogenous RNA network and prognostic nomograms for hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent R0 resection. J. Cell. Physiol. 234(11), 20342–20353. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.28634 (2019).

Kong, W. et al. Prognostic model of patients with liver cancer based on tumor stem cell content and immune process. Aging (Albany NY) https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103832 (2020).

Hong, W. et al. Deciphering the immune modulation through deep transcriptomic profiling and therapeutic implications of DNA damage repair pattern in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 582, 216594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216594 (2024).

Yan, Z. J. et al. Development of a TMErisk model based on immune infiltration in tumour microenvironment to predict prognosis of immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Brief. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbad067 (2023).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82373275, 81974384, 82173342 & 82203015), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2022M723553), four projects from the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2021JJ31092, 2021JJ31048, 2023JJ40942, 2025JJ70655), Nature Science Foundation of Changsha (No.73201), CSCO Cancer Research Foundation (No. Y-HR2019-0182 & Y-2019Genecast-043) and the Key Research and Development Program of Hainan Province (No. ZDYF2020228 & ZDYF2020125). The funders have no roles in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or the writing of this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiayao Ma: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Project administration. Diya Tang: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation. Guangzu Cui: Writing—review and editing, Validation, Resources. Xiangyang Zhang: Data curation, Visualization, Validation. Xinwen Wang: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. Yin Li: Software. Erya Hu: Validation. Xin Zhou: Validation, Resources. Haicong Liu: Software, Resources. Qingping Peng: Software. Changjing Cai: Software. Xiangying Deng: Validation. Shan Zeng: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Yihong Chen: Supervision, Conceptualization. Zemin Xiao: Supervision, Conceptualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of the Xiangya Hospital (Ethics No. 202401014). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The authors confirming that all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., Tang, D., Cui, G. et al. The molecular characteristics of DNA damage and repair related to P53 mutation for predicting the recurrence and immunotherapy response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 14939 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99853-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99853-5