Abstract

Understanding divergent perceptions of ethnic groups to climate change in mountainous regions home to multi-ethnic cultures and the factors influencing these perceptions is crucial for policymakers to predict the trending impacts of climate change and make long-term decisions. Based on the case of Southwest China, 1216 households were interviewed by questionnaire surveys to gain insight into the perceptions of local people on the dynamic evolution characteristics of climate events in the uplands of Yunnan, China, which is an area home to rich ethnic diversity, and also to determine the factors that influence these perceptions. Results indicated that climate events have now become important events for farmers’ livelihoods, ranking only after family diseases and livestock diseases. Drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall are the three kinds of climatic events with the most significant increase in frequency and severity in mountainous areas. Farmers’ perceptions on whether drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall occurred 10 years ago as well as changes in frequency and severity are significantly influenced by characteristics of respondents, ethnic culture, geographical environment of farmer residences, farmland characteristics, and sources of livelihood. Ultimately, taking ethnic differences into consideration for long-term planning will be an important part of the local response to climate change in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is affecting indigenous people and mountain ecosystems around the world (Fosu-Mensah et al., 2012). It is more pronounced in mountainous areas home to ethnic minorities because local people are highly reliant on natural resources that are particularly vulnerable to climate change (Dien and Van, 2014; Xu et al., 2009). Furthermore, diverse ethnic communities reside in ecologically heterogeneous and fragile uplands, with distinct cultures, livelihood activities, and farming practices (Akhter et al., 2013), heightening their vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change (Adger and Kelly, 1999; Byg and Salick, 2009). Farmer perceptions reflect their long-term observation of changes in climate and their concerns regarding the impact of climate events on local livelihoods (Maddison, 2006; Manh and Ahmad, 2021; Saguye, 2017; Soubry et al., 2020). Understanding the perceptions of local residents on the dynamic evolution characteristics of climate events will be crucial for policymakers to predict the trending impacts of climate change and make long-term planning (Avotniece et al., 2012; Karl et al., 1995; Meng et al., 2020; Spinoni et al., 2016). However, a number of studies have indicated that climate change perceptions are influenced by social, economic, ethnic, cultural, or the geographical features and climatic characteristics of specific areas and cannot be predicted accurately through models (Landauer et al., 2014; van Aalst et al., 2008; Varadan and Kumar, 2014). Therefore, assessing divergent perceptions of ethnic groups in mountainous regions to climate change with multi-ethnic cultures as well as the factors influencing these perceptions is necessary for developing tailored and effective climate adaptation strategies.

Many studies have assessed farmer perceptions of climate change and the factors affecting these perceptions in different ethnical and cultural contexts (Banerjee and Rupsha, 2015; Chun-xiao et al., 2019; Lazo et al., 2000; Pham et al., 2019; Wang and Feng, 2023; Williamson et al., 2005). For example, several studies found that non-White minorities (Blacks and Latinos) in the United States show higher levels of risk perception and support for national and international climate and energy policies than Whites (Macias, 2016; Pearson et al., 2017; Speiser and Krygsman, 2014; Whittaker et al., 2005). One study from Australia (Hansen et al., 2014) indicated that immigrants who wear thicker and darker clothing due to cultural and religious factors or prefer heated food, have a significant perception of extreme heat and have lower adaptability to it. Research by Elias et al. (2018) in Africa found that minority communities were more aware of climate change than majority ethnic groups. Manh and Ahmad (2021) revealed significant differences in the perceptions of climate change among the Tay, Hmong, and Dao farmers in the mountainous areas of Vietnam.

Notwithstanding the existence of a few studies concerning the cultural and ethnic differences in climate change perception, most research tends to focus on perceptions and impact factors of climate change in urban areas or differences between two or three ethnic groups (Abid et al., 2019; Aslam, 2018; Dang et al., 2014; Deressa et al., 2011; Elias et al., 2018; Hansen et al., 2014; Landauer et al., 2014; Maddison 2006; Nguyen et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2017; Pham et al., 2019; Sanchez et al., 2012; Shrestha et al., 2017; van der Linden, 2017). These studies have found that vulnerable populations and ethnic minorities have a more pronounced perception of climate change, while factors affecting the perception of climate change among mountain system residents remain more complex. Research into the perception of climate change by ethnic minorities in mountainous areas has mainly been based on using independent communities living at different altitudes as sample populations, and these studies have typically focused on developing countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, and India. In terms of research on the cognition of ethnic minorities towards climate change, most of these studies explore the traditional knowledge of certain ethnic groups and their consequent adaptation to climate change. For instance, Byg and Salick (2009) reported that Tibetan villages perceived changes in climate to be related to local phenomena, such as spiritual retribution, overpopulation, and increased electricity consumption. However, research into indigenous farmer perceptions of climate change and determinants of household perceptions of climate change in multi-ethnic and multi-cultural mountainous areas remain scarce.

Northwestern Yunnan in China features three rivers (Yangtze River, Mekong River, and Salween River) that flow in parallel. The area’s terrain is characterized by high mountains and steep valleys, with significant elevation fluctuations and extreme sensitivity to climate change. Affected by this complex terrain, this region has a distinct three-dimensional climate and diverse microclimates, fostering rich biodiversity and ecosystems. It is also the region home to the highest level of diversity for ethnic groups in China, with different ethnic groups coexisting across different climate zones. For example, the Lisu mainly reside in low-altitude areas. The ethnic groups in mid-altitude areas are the most diverse, with a larger population consisting of Bai, Han, and Lisu. High-altitude areas are mainly inhabited by Naxi and Tibetan communities. Resembling other multi-ethnic societies in mountainous areas around the world, most of these ethnic minorities live alongside fragile ecological environments, and their traditional livelihoods are more significantly impacted by climate change and its associated natural disasters (Chen et al., 2017; Lun et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2009). Local resident’s perceptions of climate change are influenced by multiple factors due to the complex geographical environment, diverse three-dimensional climate, and socio-economic background (Yang et al., 2006). In order to compensate for the lack of research on the perception of climate change in mountainous multi-ethnic communities from the perspective of ethnic differences, this research selected northwestern Yunnan as a case study to reveal the perceptions of local people on the dynamic evolution characteristics of climate events and determine the factors that influence these perceptions, as the area’s complex geographical environment and diverse ethnic characteristics resemble mountainous environments of most developing countries.

To achieve the aim of this study, the research attempted to answer the following empirical questions: (1) What climate events have affected the livelihoods of residents in multi-ethnic mountainous areas in the past 10 years? (2) Did the climate events suffered by local residents occur 10 years ago? (3) Compared with 10 years ago, how has the frequency and severity of climate events affecting local residents changed? (4) What factors influence local residents’ perceptions of the dynamic evolution of climate events? Through an empirically grounded approach, a questionnaire survey was administered across 1216 households in Southwest China, which is a region of the country featuring a high degree of ethnic diversity. This research contributes to the existing literature by deepening our understanding of the perceptions of residents in multi-ethnic mountainous areas on the dynamic evolution of climate events as well as helping identify the factors that influence the formation of this perception.

Conceptual framework

Perception refers to practical knowledge arising from experience and concrete situations (Gupta, 2012). Perception of climate change in this study is defined as the respondents’ perception of changes in the climate based on observation and individual experience in relation to the increase, decrease, or no change in precipitation, temperature, and extreme weather events over a long period of time. The analysis of farmers’ perceptions of climate change was divided into two stages. The first stage sought to determine what climate events local farmers perceive and how their frequency and severity change over time through three questions. The second stage examined factors associated with risk perception of climate change using the Climate Change Risk Perception Model (CCRPM) proposed by van der Linden (2015). According to CCRPM, risk perceptions of climate change can be influenced by cognitive factors (i.e., knowledge about climate change), experiential factors (i.e., affect and personal experience with extreme weather events), socio-cultural factors (i.e., social norms and values) and socio-demographic factors (i.e., age, gender, income, and education level). However, the risk perceptions of climate change are complex and multidimensional (Elshirbiny and Abrahamse, 2020; Slovic et al., 2010), and their influencing factors may vary depending on different geographical environments as well as socio-economic and cultural contexts (Pidgeon et al., 1992). Given the complex geographical environment, stark elevation differences, and diverse livelihood strategies and ethnic cultures of local farmers in the research area, this study adapts the determination of factors affecting farmers’ perceptions of climate change into three dimensions based on CCRPM, including socio-demographic, geographical and livelihood source factors. Cognitive factors, experiential factors, and socio-cultural factors in CCRPM were excluded. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework adapted from van der Linden (2015) and used in the current study.

Methods

Study area

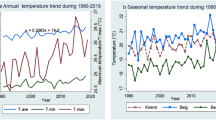

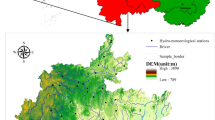

The study was conducted in northwestern Yunnan Province in Southwest China at the southeast rim of the Tibetan Plateau (24°47′N—29°13′N, 98°08′E—101°32′E) (Yang et al., 2015) (Fig. 2). Northwestern Yunnan is a typical alpine canyon region, featuring a three-dimensional climate and diverse ecosystems (Yang et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2015). The regional climate is influenced by the southwest monsoon, southeast monsoon, and the continental alpine climate of the Tibetan Plateau (Xu et al., 2009). The local climate is generally divided into rainy and dry seasons. The rainy season lasts from May to October, and the precipitation it brings accounts for 80% of total annual rainfall. The remaining time is the dry season (Yang et al., 2016). In the last few decades, northwestern Yunnan has shown a general trend of fluctuating rainfall and increasing temperatures (Xu et al., 2007; Zongxing et al., 2010).

There are 14 ethnic groups in northwestern Yunnan, making it home to the richest ethnic diversity in China (Chen et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2006). Northwestern Yunnan is composed of four prefectures: Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture; Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture; Lijiang City (prefecture-level city); and Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture (Chen et al., 2017). The multi-ethnic cross-border area at the junction of Diqing, Nujiang, and Lijiang was selected as the study area. The main ethnic group of Diqing is Tibetan. In Nujiang, Lisu is the main ethnic group, and a small number of Nu, Dulong, and Pumi are also distributed throughout the prefecture. In Lijiang, Naxi is the main ethnic group, and there are also a small number of Mosuo, Yi, Bai, Hui, and other residents. At the junction of the three prefectures, many members from different ethnic groups cohabit (Lun et al., 2020). Traditional livelihoods of resident ethnic groups mainly include agriculture and nomadism, in addition to hunting, fishing, and gathering (Jianchu et al., 2005). Diversified livelihoods based on rain-fed agriculture can typically be found throughout this area. Nowadays, off-farm activities also form an important component of the livelihoods of local people, including migrant work, tourism services, collecting non-timber forest products, and planting Chinese herbal medicines (He et al., 2018). The livelihoods of local people remain highly dependent on natural resources, which are directly and significantly affected by climate change.

Data collection

Information was collected through a semi-structured questionnaire survey administered in January 2015. Through random sampling, we first selected two counties from each prefecture, before selecting 2–4 townships from each county, 2–4 villages from each township, and 30 households from each village. Ultimately, a total of 6 counties, 17 townships, 42 villages, and 1216 households were selected for the investigation (see ST 1). Before beginning our investigation in each village, we contacted the local village committee leaders in advance. With their help, we first wrote all the eligible households to interview on paper, put them into a box, and then drew 30 pieces of paper from the box at random. Households were selected for the survey in accordance with the selected 30 pieces of paper, and only one person from each household was surveyed. The entire interview was conducted via face-to-face conversations. The survey was carried out by four researchers from the Kunming Institute of Botany and 17 trained undergraduates and postgraduates from Yunnan Agricultural University and Yunnan Minzu University during their winter holiday. Each investigator completed approximately 4–5 questionnaires per day.

The household questionnaire was composed of three parts. The first part recorded information related to social relationships and family characteristics. The second part was related to economic conditions and farmlands as well as livelihood structure. The third part quired the households’ perception of climate events and socio-economic events that affect their livelihoods. For the selection and categorization of these events, we presented a range of potential climate and socio-economic occurrences, encouraging farmers to choose and offer open responses. From these selections and answers, we distilled a total of 28 hazard events that affect farmers’ livelihoods. Based on expert knowledge and relevant literature, we grouped events related to climatic factors, such as temperature and rainfall, under climate events, while those primarily stemming from socio-economic factors were designated as socio-economic events. Each category encompassed 14 events, as detailed in ST2. The perception of these events was specifically obtained through the following three steps.

-

(1)

Respondents were first asked what climate events or socio-economic-related hazard events they have suffered from in the past 10 years (2005–2015). The interviewees were provided a list of climate events and socio-economic-related hazard events and were asked to select the hazard events that they perceived. If the hazard events they perceived were not listed in the questionnaire, they could add them.

-

(2)

Those who perceived hazardous events were asked if they thought these events had occurred 10 years ago (before 2005).

-

(3)

With respect to the perceived hazard events, we asked respondents to compare the changes in the frequency and severity of these events in the last 10 years (2005–2015) with those from 10 years ago (before 2005).

Data analysis

The number of local respondents and their percentage of the total interviewed respondents were used to assess perceptions of climate events and socio-economic-related hazard events. The perceptions of the three most-mentioned climate events (drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall) over time by respondents were selected as the dependent variables. It is binary to determine whether a perceived climate event occurred 10 years ago, with 1 indicating it has occurred and 0 indicating it has not. The nature of the dependent variable suggests a non-linear relationship due to a discontinuous relationship and the non-applicability of the ordinary least square method. Therefore, a binary logistic regression was used to assess the impact of various factors on whether respondents thought these events had occurred 10 years ago; Multiple logistic regression was used to evaluate the effects of various factors on changes in the frequency and severity of climate events in the last 10 years as well as those from 10 years ago. The dependent variable of the M-logit model is the level of change in frequency and severity of each climate-related event perceived by households. The level of frequency change is divided into less frequent, more frequent, and new occurrences, while the level of severity change is divided into less severe, more severe, and new occurrences. The choice is one of three levels. Socio-economic factors, environmental factors, and household characteristics were selected as independent variables for regression analysis. A total of 34 variables were selected for logistic regression analysis (see ST 3).

The stepwise method (backward) was performed with tolerance set at 0.001 and PIN (0.15) and POUT (0.20). (to select variables with significance in the model.) This method includes all predictor variables, whether or not they are statistically significant. Variables are tested, one at a time, for removal from the model. The first variable that is removed from the model is the variable whose likelihood ratio statistics have the largest probability that is greater than alpha (Nepal, 2003; Wright, 1995). The procedure continues to remove variables from the model until the model contains only variables that are statistically significant. The coefficient vectors or parameters were estimated by the maximum likelihood method using the SPSS 20.0. Only results that showed a significant effect are reported below.

Results

Hazard events suffered by households in the last 10 years

In order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the hazard events that affect farmers’ livelihoods and the role of climate events among them, we investigated and analyzed both climate and socio-economic events (See ST2) that have a significant impact on farmers’ livelihoods and made comparisons between them. For instance, family sickness and livestock diseases caused by socio-economic factors, although difficult to attribute solely to climate change, are two important categories of events that significantly affect farmers’ livelihoods. Table 1 highlights the important events—socio-economic and climate hazards—that have affected local residents’ livelihoods in the last 10 years (2005–2015). Family sickness is the most important event from which local residents report suffering, involving 470 households, accounting for 38.7% of total respondents. Livestock diseases, drought as well as crop diseases, and pests follow family sickness. The number of households involved in these three types of events each exceeds 20% of the total number of respondents: 24.8% (301), 20.6% (251), and 20.1% (244), respectively. Some climate events, such as long-term drought, erratic rainfall, strong wind, hail, flood, landslide, and soil erosion, also involve many households. The corresponding number of respondents accounts for 10.5% (128), 6.7% (81), 6.5% (79), 6.3% (77), 5.0% (61) and 4.6% (56) of the total respondents, respectively.

Whether the hazard events suffered by the household occurred 10 years ago

To compare the same hazarded event effect in the last 10 years with 10 years ago, we asked respondents whether the hazard events suffered by them in the last 10 years (2005–2015) had occurred 10 years ago (before 2005). Statistical results are shown in Table 2. Most respondents mentioned that the events they suffered in the last 10 years generally also occurred 10 years ago. However, for family sickness, livestock diseases, drought, crop diseases and pests, long-term drought, erratic rainfall, strong wind, flood, landslide, and soil erosion, some people stated that these events had not occurred 10 years ago, with 133, 47, 42, 26, 37, 16, 9, 11 and 15 respondents, respectively.

Changes in the frequency of hazard events suffered by the household in the last 10 years

For each hazard event suffered by households in the last 10 years, we surveyed respondents about its change in frequency compared to 10 years ago. We provided three options: less, no change, and more frequently than before. Statistical results are shown in Table 3. There were 10 important events mentioned by most respondents in the following order: family sickness, livestock disease, drought, crop disease and pests, long-term drought, erratic rainfall, strong wind, hail, flood, landslide, and soil erosion. For family sickness, livestock diseases as well as crop diseases and pests, the number of respondents who think that the frequency has not changed in the last 10 years was the most common response, with “less than before” coming next before “more frequent than before” being the least common. Moreover, the number of respondents who believe that the frequency has not changed is significantly more than those who chose the other two options. For drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall, the number of respondents who believe that they have occurred more frequently in the last 10 years was the most common response, significantly higher than the number of respondents who believe that there is no change or that they are fewer than before.

Changes in the severity of hazard events suffered by the household in the last 10 years

Table 4 shows the comparison of the severity of important events suffered by local people in the last 10 years compared to 10 years ago. For family sickness, although the number of respondents who believe their severity has not changed compared to 10 years ago, this category was the most common response at 154 selections. In addition, many respondents (145) think it is more serious than before, far higher than the number of respondents who think it is not as serious as before (69). For the severity of livestock diseases as well as crop diseases and pests, more respondents believe that there is little difference compared to 10 years ago, and the respective numbers of respondents reached 112 and 104. For drought, long-term drought, erratic rainfall, landslides, and soil erosion, the number of respondents who believe that these events have become more serious in the last 10 years is significantly higher compared to 10 years ago. This indicates that most respondents believe that these events have become more serious in the last 10 years. In particular, the increased severity of drought and long-term drought is the most obvious. Regarding other events, their severity has changed little in the last 10 years.

Factors affecting whether the climate events about which most households were concerned occurred 10 years ago

The climate-related events most mentioned by respondents were selected to assess the impact of socio-economic variables on local people’s perceptions of these events over time. Events selected for analysis included drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall. Analysis of the results of farmer perceptions on whether these events occurred 10 years ago is presented in Table 5.

From Table 5, farmer perceptions of whether drought occurred 10 years ago are significantly affected by the proportion of currently cultivated land and the proportion of forest product sales. Households with a higher proportion of cultivated land believe that drought was more likely to have occurred 10 years ago, while those with a higher proportion of income from forest products believe that drought was less likely to have occurred 10 years ago.

With regard to the perception of whether long-term drought occurred 10 years ago, those households who live farther away from the local county seat believe that long-term drought is more likely to have occurred 10 years ago. Households with a higher proportion of rain-fed land believe that long-term drought is less likely to have occurred 10 years ago.

As for the perception of whether erratic rainfall occurred 10 years ago, households who have a large area of rain-fed land and a higher proportion of income from Chinese herbal medicine believe that erratic rainfall is less likely to have occurred 10 years ago.

Factors affecting changes in the frequency and severity of climate events about which most households were concerned in the last 10 years and 10 years ago

Factors affecting changes in the frequency and severity of drought in the last 10 years and 10 years ago

The frequency and severity of climate events are important indicators to evaluate the impact of climate events on farmer livelihoods. Analysis of the impact of various factors on farmer perceptions of changes in the frequency and severity of drought in the last 10 years and 10 years ago are shown in Table 6. The data suggest that the higher the proportion of farmers whose income comes from migrant workers, the more likely they are to believe that the frequency of drought is less than ten years ago. Compared with Tibetans, Lisu individuals are less likely to believe that the frequency of drought in the last 10 years is less compared to 10 years ago. Households located farther away from the county seat with a higher proportion of irrigable land are less likely to believe that drought occurs more frequently now than it did a decade ago. The older the respondent, the more likely they are to believe that drought is occurring more frequently now compared to a decade ago. Compared to farmers with a primary education level, farmers at a junior middle school education level are more likely to believe that drought occurs more frequently now compared to a decade ago.

Regarding the perception of changes in drought severity, the farther away the farmers live from the county seat, the less likely they are to believe that drought is more serious now compared to ten years ago, while while increased age of respondents correlates to increased belief that drought is more serious now compared to ten years ago. Compared with Tibetans, Nu individuals are less likely to believe that drought is more serious now compared to a decade ago. Households with a higher proportion of salaried income are more likely to think that drought is a new phenomenon emerging in the last 10 years.

Factors affecting changes in the frequency and severity of long-term drought in the last 10 years and 10 years ago

Analysis of factors influencing the ways in which local perceptions of long-term drought change in frequency and severity are shown in Table 7. The farther away the household is located from the county seat, the less likely they are to believe that the frequency of long-term drought is less, more, or newer than ten years ago—that is, the less likely they are to respond significantly to changes in the frequency of long-term drought. Households with a larger proportion of rain-fed land are less likely to believe that long-term drought occurs less or more frequently than it did a decade ago—that is, such households cannot respond significantly to changes in the frequency of long-term drought. Compared with those who believe that there is no extreme weather, respondents who believe that family houses are capable of completely withstanding natural disasters are more likely to believe that long-term drought occurs less frequently now compared to a decade ago. Compared with men, women are less likely to think that long-term drought occurs more frequently now compared to a decade ago. In households, the higher the proportion of income from business activities other than tourism services, the more likely they are to believe that long-term drought is a new phenomenon emerging in the last 10 years. Compared with households that largely have terraced farmland, households with steep farmland are less likely to believe that long-term drought is a new phenomenon emerging in the last 10 years.

Regarding the perception of changes in the severity of long-term drought, the farther away the households live from the county seat, the less likely they are to believe that long-term drought in the last 10 years is not more serious, more serious, or new. Households with a higher proportion of cultivated land are less likely to believe that long-term drought in the last 10 years is more serious or new compared to before. Households with a higher proportion of rain-fed land are less likely to believe that long-term drought in the last 10 years is more serious than before. Compared with Tibetans, Naxi individuals are more likely to believe that long-term drought in the last 10 years is more serious than before or that it is new. Compared with farmers who believe there is no extreme weather, those who believe their houses can completely resist natural disasters are more likely to believe that long-term drought is not more serious than before or that it is new. Compared with households that largely have terraced farmland, households with mostly flat farmlands are less likely to believe that long-term drought in the last 10 years is more serious than before or that it is new. Households with mostly sloping farmland are more likely to believe that long-term drought is more serious than before.

Factors affecting changes in the frequency and severity of erratic rainfall in the last 10 years and 10 years ago

From Table 8, households with a higher proportion of cultivated farmland are more likely to believe that erratic rainfall is less frequent than it was 10 years ago. Households living far away from the county seat are less likely to believe that erratic rainfall occurs more frequently now compared to 10 years ago. Compared with Tibetans, Han individuals are more likely to believe that erratic rainfall has only occurred in the last 10 years.

With regard to the perception of changes in the severity of erratic rainfall, households with a higher proportion of cultivated farmland are less likely to believe that erratic rainfall in the last 10 years is more serious than 10 years ago or that it is new. Households with a higher proportion of salaried income are less likely to believe that the severity of erratic rainfall is more serious now compared to 10 years ago. Compared with Tibetans, Han individuals are more likely to believe that erratic rainfall is a new occurrence emerging in the last decade. Compared to respondents whose education level reaches primary school, respondents whose education level reaches junior middle school are more likely to believe that erratic rainfall is new in the last decade.

Discussion

In general, climate disasters have become the main events affecting the livelihoods of farmers, ranking only after family sickness and livestock diseases (Table 1). This study found that drought, crop diseases and pests, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall are considered by most as events occurring with a high frequency in the last 10 years (Table 3). At the same time, their severity is more serious now compared to 10 years ago (Table 4). Similar findings have been revealed in many previous studies undertaken in arid regions (Brito et al., 2017; Hualei, 2017; Peng et al., 2018). Although the frequency of landslides and soil erosion is not significantly different from that of 10 years ago, their severity is significantly more serious than that of 10 years ago. This point has seldom been raised in previous studies. This may be due to the frequent occurrence of erratic rainfall in mountainous areas, which often leads to concentrated rainstorms that trigger natural disasters like landslides, debris flow, soil erosion, and more. The results here imply that livelihood sources of residents directly affected by rainfall are more seriously affected now compared to 10 years ago because agricultural income and income from non-timber forest products are directly affected by drought and erratic rainfall. This is similar to the research by Byg and Salick (2009) in the same area, where they found that most local Tibetans perceived a decrease in the annual amount of snow and rain.

This study also found that certain characteristics of respondents (such as gender, age, and education level), the geographical environment of farmer residences, farmland characteristics, and livelihood income sources all have a significant impact on farmer perceptions of changes in the frequency and severity of climate events (Tables 6–8). This finding is consistent with many previous studies (Banerjee and Rupsha, 2015; Chun-xiao et al., 2019). However, in terms of gender, we found that women did not think that long-term drought was more frequent compared to 10 years ago, in contradistinction to most studies which have found that women generally perceive greater climate risk than men (Lazo et al., 2000; Williamson et al., 2005). This may be because of women’s different sensitivities to climate events related to water. For example, research in India found that women have a higher level of perception of climate events such as rainfall reduction or droughts (Sam et al., 2020). This may be due to the underdeveloped local water supply facilities in India, where women need to collect drinking water from places far away from houses, which makes local women more aware of and vulnerable to water scarcity. But in rural villages in China, tap water is installed in almost every household, which virtually eliminates the need for women to go out and collect drinking water, which makes them relatively insensitive to the lack of water resources. At the same time, due to men migrating out to work, most rural women in China stay behind to engage in agricultural production for an extended period of time in the region, which makes them accustomed to the impact of long-term drought on agricultural production activities and insensitive to climate events. On the contrary, many men have migrated out to work, rarely engaging in agricultural production activities, and are more sensitive to long-term drought. This is supported by Lazo et al. (2000), who found that men perceived greater overall risk to ecosystems from climate change. This study also indicates that older respondents, due to their richer life experiences, have observed non-drought periods before and are more sensitive to the new climate of higher temperatures and drought which has become increasingly apparent in recent years. In turn, this makes them feel that drought now occurs more frequently and severely compared to the past. This finding supports the generally proposed idea that people who have experienced extreme weather events often have higher risk perceptions of climate change (van der Linden, 2015).

In addition, differences were observed in climate event change perceptions across ethnic groups. Compared with Tibetans, Lisu, Naxi, and Han individuals believe that drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall have occurred more frequently and severely in the past 10 years compared to 10 years ago (Tables 6–8). This may be because Tibetans live in an alpine climate zone with little rain and essentially do not plant crops in the dry seasons (winter and spring) owing to drought and lower temperatures. Their livelihoods are thus relatively less affected by drought and erratic rainfall. In contrast, most Lisu, Naxi, and Han individuals live on both sides of the river valley or in flat lowland areas, where they usually plant crops in the dry season, making them more sensitive to water shortages in the dry season. At the same time, rainfall in lowland areas is more abundant than in the type of high-altitude areas where Tibetans tend to live, which makes Lisu, Naxi, and Han individuals more sensitive to changes in rainfall. Therefore, compared with Tibetans, they believe that erratic rainfall is more serious now compared to 10 years ago. This study also found that compared with Tibetans, Nu individuals are less likely to believe that drought is serious, which may be due to more abundant rainfall in areas where Nu people tend to reside compared to the areas where Tibetans live. The findings are in line with the results of research by Manh and Ahmad (2021), who found a significant difference among ethnic groups’ perceptions of change climate in mountainous areas of Vietnam.

Although perceptions of climate change are influenced by ethnic differences, these perceptions are more likely due to the combined effects of various factors such as the geographical environment, climate conditions, and livelihood activities of different ethnic groups, which have also been reflected in other studies. For example, several studies have found that whether in developing or developed countries, ethnic minorities have a higher level of perception of climate change due to their diverse climate regions and higher dependence on natural resources for their livelihoods (Elias et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2017). Sanchez et al. (2012) found that there were no differences in the perception of climate change among different ethnic groups distributed in one climatic zone, while Manh and Ahmad (2021) found that there were differences in the perception of climate change among different ethnic groups in the same latitude but different altitudes. Lun et al. (2020) found that even in a small geographical area, perceptive differences in climate change by local ethnic minorities may be substantially large, largely caused by the differences in the three-dimensional climate, geographical environment, and family planning activities. The specific environment in which different ethnic groups reside and the diverse livelihoods they employ are likely the explanatory factors for the existence of differences in perceptions held across different ethnic groups on changes in climate events.

Local residents’ perceptions of changes in climate events are also affected by the geographical environment of their residence. Households located far away from the local county seat believe that drought and erratic rainfall are less frequent and severe now compared to 10 years ago (Tables 6 and 8). This may be because the effects of climate change in these areas are not obvious, or potentially because the local forest vegetation has recovered well in recent years, which can offer a good buffer and regulatory effect on climate change, reducing the occurrence of climate events. The study found that compared with households with largely terraced farmland, households with mostly steep farmland are less likely to believe that long-term drought is a new phenomenon; households with mostly flat farmland are less likely to believe that long-term drought in the last 10 years is more serious than before or that it is new; and households with mostly sloping farmland are more likely to believe that long-term drought is more serious now compared to before (Table 7). This finding is similar to a study by Shrestha et al. (2017), who found that the impact of climate change was perceived to be higher in communities living at higher elevations compared to those at lower elevations. This may be because farmland with flat terrain intercepts more rainwater, and this kind of farmland has stronger water-holding capacity, thereby making it less sensitive to long-term drought. On the contrary, sloped farmland or farmland across steep terrain intercepts less rainwater and has a weaker water-holding capacity, making it more vulnerable to long-term drought, thus aggravating the potential impact of long-term drought on agricultural production. This study indicates that farmers whose houses can completely resist natural disasters believe that long-term drought is less frequent and less serious now compared to 10 years ago, which may be related to their confidence in their household resilience to natural disasters.

Irrigation conditions and water conservation characteristics of farmland both exert an important impact on farmers perceptions of climate change. For example, some households with a high proportion of irrigable land are less likely to believe that drought is more frequent now compared to 10 years ago (Table 6) because their paddy fields feature the inherent ability to resist drought, are less directly affected by drought, and ultimately not sensitive to drought. We found that respondents with a higher proportion of rain-fed land are less likely to believe that long-term drought is more frequent or serious now compared to 10 years ago (Table 7), which may be because most of the rain-fed land is not cultivated in the dry season and therefore not affected by long-term drought. We also found that respondents with a higher proportion of cultivated land believe that long-term drought and erratic rainfall are not more serious now compared to 10 years ago (Tables 7 and 8), which may be because most of the lands cultivated by these people in the dry season feature strong water-holding capacity and are relatively unaffected by drought.

The study found that differences in farmers’ perception of climate events in the last 10 years and those that occurred 10 years ago are affected by the sensitivity of farmer livelihood sources to climate events and farmer attention to livelihoods. In general, most farmers with high income from off-farming activities believe that climate events are not serious, which may be because off-farming activities are less directly affected by climate change, and some farmers simply place their attention elsewhere. For example, farmers receiving a high proportion of income from migrant work believe that drought is less frequent now compared to 10 years ago. Farmers with higher salaried incomes also believe that erratic rainfall is not more serious compared to 10 years ago. Previous studies by Byg and Salick (2009) in the same region have also found that the number of people who believe that climate change has a negative impact is lower in villages with more tourists than in villages with fewer or no tourists.

Conclusion

Climate events such as drought, crop diseases and pests, long-term drought, erratic rainfall, strong winds, hail, floods, soil erosion, and so on have become important events suffered by farmers, ranking only after family diseases and livestock diseases. Most people believe that these events also occurred 10 years ago, but some people believe that these events have only occurred in the last 10 years. Drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall are the three kinds of climatic events with the most noticeable increase in frequency and severity in mountainous areas. Farmer perceptions of whether drought, long-term drought, and erratic rainfall occurred 10 years ago as well as changes in frequency and severity are significantly influenced by respondent characteristics, ethnic culture, the geographical environment of farmer residences, farmland characteristics, and sources of livelihood. How to reduce the impact of drought and erratic rainfall is an important issue for local governments and residents in multi-ethnic mountainous areas to formulate adaptive strategies to deal with climate change. We suggest that transforming steep agricultural land into terraces or transforming sloping agriculture into a forestry economy is one practical and feasible measure to cope with climate change in multi-ethnic mountainous areas. At the same time, achieving diversified livelihoods and increasing the proportion of off-farm income to household income could also be a critical strategy for addressing climate change, which has been a demonstrated path forward in many similar regions. Paying greater attention to ethnic and cultural differences will be an important part of local responses to climate change in the future.

Limitations and future research directions

This study examined different communities where multiple ethnic groups live together through the lens of ethnic diversity, which is more representative of the reality of multi-ethnic regions than previous studies which have only examined a single ethnic community. Integrating the complex geographical factors and diverse livelihood sources of mountainous communities into the differential analysis of farmers’ perception of climate change can provide a more realistic understanding of the obstacles faced by mountainous ethnic groups in perceiving and adapting to climate change. However, the study has a few drawbacks. First, when using the framework of CCRPM to analyze the influencing factors on farmers’ perception of climate change, only socio-demographics were included, lacking analysis from the other three components. Future research will continue to enrich the model of analysis by incorporating cognitive, experiential, and socio-cultural factors into the survey and analysis, especially regarding the traditional knowledge of different ethnic groups adapting to climate change and managing natural resources, which is a key factor in community-based responses to climate change. Second, the evaluation of climate change indicators lacks support from meteorological monitoring data. In future research, meteorological stations can be locally established to obtain robust meteorological data to inform the analysis. Finally, although we analyzed the impact of topography and level of irrigation of farmlands on farmers’ perception of climate change, we did not take into account that the complex terrain and diverse survey locales may generate biases in the perception of local residents. Future research may require a quantitative assessment of the vulnerability and adaptability of local residents to climate change based on terrain and altitude classification, combined with meteorological data and economic losses resulting from climate disasters.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are uploaded as supplementary materials to this article.

References

Abid M, Scheffran J, Schneider UA, Elahi E (2019) Farmer perceptions of climate change, observed trends and adaptation of agriculture in Pakistan. Environ Manag 63(1):110–123

Adger WN, Kelly PM (1999) Social vulnerability to climate change and the architecture of entitlements. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 4:253–266

Akhter S, Raihan F, Sohel MSI, Syed MA, Alamgir M (2013) Coping with climate change by using indigenous knowledge of ethnic communities from in and around Lawachara National Park of Bangladesh. J For Environ Sci 29(3):181–193

Aslam MA (2018) Understanding farmers perceptions about climate change: a study in a North Indian State. Adv Agri Environ Sci Open Access (AAEOA 1(2):85–89

Avotniece Z, Klavins M, Rodinovs V (2012) Changes of extreme climate events in Latvia. Sci J Riga Tech Univ Environ Clim Technol 9:4–11

Banerjee X, Rupsha R (2015) Farmers’ perception of climate change, impact and adaptation strategies: a case study of four villages in the semi-arid regions of India. Nat Hazards 75(3):2829–2845

Brito SSB, Cunha APMA, Cunningham CC, Alvalá RC, Marengo JA, Carvalho MA (2017) Frequency, duration and severity of drought in the Semiarid Northeast Brazil region. Int J Climatol 38(2):517–529

Byg A, Salick J (2009) Local perspectives on a global phenomenon—climate change in Eastern Tibetan villages. Glob Environ Change 19(2):156–166

Chen T, Peng L, Liu S, Wang Q, Chen T, Peng L, Liu S, Wang Q (2017) Spatio-temporal pattern of net primary productivity in Hengduan Mountains area, China: impacts of climate change and human activities. Chin Geogr Sci 27(6):948–962

Chun-xiao S, Rui-feng L, Oxley L, Heng-yun M (2019) Do farmers care about climate change? Evidence from five major grain producing areas of China. J Integr Agri 18(6):1402–1414

Dang H, Li E, Bruwer J, Nuberg I (2014) Farmers’ perceptions of climate variability and barriers to adaptation: lessons learned from an exploratory study in Vietnam. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 19(5):531–548

Deressa TT, Hassan RM, Ringler C (2011) Perception of and adaptation to climate change by farmers in the Nile basin of Ethiopia. J Agric Sci 149(1):23–31

Dien TV, Van DX (2014) Agricultural production model adapt to climate change based on indigenous knowledge of ethnic minorities in BAC KAN province, Vietnam. Asian Research Publishing. Netw (ARPN) ARPN J Earth Sci 3(1):1–7

Elias T, Dahmen NS, Morrison DD, Morrison D, Morris DL (2018) Understanding climate change perceptions and attitudes across racial/ethnic groups. Howard J Commun. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2018.1439420

Elshirbiny H, Abrahamse W (2020) Public risk perception of climate change in Egypt: a mixed methods study of predictors and implications. J Environ Stud Sci 10:242–254

Fosu-Mensah BY, Vlek PLG, Maccarthy DS (2012) Farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change: a case study of Sekyedumase district in Ghana. Environ Dev Sustain 14(4):495–505

Gupta AD (2012) Way to study indigenous knowledge and indigenous knowledge system. Antrocom Online J Anthropol 8:373–393

Hansen A, Nitschke M, Saniotis A, Benson J, Tan Y, Smyth V, Wilson L, Han GS, Mwanri L, Bi P (2014) Extreme heat and cultural and linguistic minorities in Australia: perceptions of stakeholders. BMC Public Health 14(1):1–12

He J, Yang B, Dong M, Wang Y (2018) Crossing the roof of the world: trade in medicinal plants from Nepal to China. J Ethnopharmacol 224:100–110

Hualei J (2017) Analysis of climate change and drought characteristics of Julu in Hebei Province during 1959~2016. Clim Change Res Lett 6(4):265–272

Jianchu X, Erzi TM, Duojie T, Yongshou F, Zhi L, David M (2005) Integrating sacred knowledge for conservation: cultures and landscapes in Southwest China. Ecol Soc 10(2):7, [online] URL http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss2/art7/

Karl TR, Knight RW, Plummer N (1995) Trends in high-frequency climate variability in the twentieth century. Nature 377(6546):217–220

Landauer M, Haider W, Proebstl-Haider U (2014) The influence of culture on climate change adaptation strategies: preferences of cross-country skiers in Austria and Finland. J Travel Res 53(1):95–109

Lazo JK, Kinnell JC, Fisher A (2000) Expert and layperson perceptions of ecosystem risk. Risk Anal 20(2):179–193

Lun Y, Misiani Z, Yanyan Z, Xiaohan Z (2020) The impacts of climate change on the traditional agriculture of ethnic minority in China. J Environ Eng Sci 9(2):43–55

Macias T (2016) Environmental risk perception among race and ethnic groups in the United States. Ethnicities 16:111–129

Maddison D (2006) The perception of and adaptation to climate change in Africa. CEEPA Discussion Paper No. 10. Centre for Environmental Economics and Policy in Africa, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Manh NT, Ahmad MM (2021) Indigenous farmers’ perception of climate change and the use of local knowledge to adapt to climate variability: a case study of Vietnam. J Int Dev 33:1189–1212

Meng D, Shengzhi H, Qiang H, Guoyong L, Yi G, Lu W, Wei F, Pei L, Xudong Z (2020) Assessing agricultural drought risk and its dynamic evolution characteristics. Agric Water Manag 231(24):106003

Nepal SK (2003) Trail impacts in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) national park, Nepal: a logistic regression analysis. Environ Manag 32(3):312–321

Nguyen TPL, Seddaiu G, Virdis SGP, Tidore C, Pasqui M, Roggero PP (2016) Perceiving to learn or learning to perceive? Understanding farmers’ perceptions and adaptation to climate uncertainties. Agric Syst 143:205–216

Pearson AR, Ballew MT, Naiman S, Schuldt JP (2017) Race, class, gender and climate change communication. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.412

Peng Y, Xia J, Zhang Y, Zhan C, Qiao Y (2018) Comprehensive assessment of drought risk in the arid region of Northwest China based on the global Palmer drought severity index gridded data. Sci Total Environ 627(15):951–962

Pham NTT, Nong D, Garschagen M (2019) Farmers’ decisions to adapt to flash floods and landslides in the Northern Mountainous Regions of Vietnam. J Environ Manag 252:109672

Pidgeon N, Hood C, Jones D, Turner B, Gibson R (1992) Risk perception. In F. Warner (ed.). Risk: analysis, perception, management, report of a royal society study group. The Royal Society, London. pp. 89–134

Sam AS, Padmaja SS, Kächele H, Kumar R, Müller K (2020) Climate change, drought and rural communities: understanding people’s perceptions and adaptations in rural eastern India. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 44:101436

Saguye TS (2017) Farmers’ perception of climate change and variability and it’s implication for adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices. Am J Hum. Ecol 6(1):27–41

Sanchez AC, Fandohan B, Assogbadjo AE, Sinsin B (2012) A countrywide multi-ethnic assessment of local communities’ perception of climate change in Benin (West Africa). Clim Dev 4(2):114–128

Shrestha RP, Chaweewan N, Arunyawat S (2017) Adaptation to climate change by rural ethnic communities of Northern Thailand. Climate 5(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli5030057

Slovic P, Fischhoff B, Lichtenstein S (2010) Why study risk perception? Risk Anal 2(2):83–93

Soubry B, Sherren K, Thornton TF (2020) Are we taking farmers seriously? A review of the literature on farmer perceptions and climate change, 2007–2018. J Rural Stud 74:210–222

Speiser M, Krygsman K (2014) American climate values 2014: insights by racial and ethnic groups. Strategic Business Insights and ecoAmerica, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://ecoamerica.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/09/eA_American_Climate_Values_2014_Insights_by_Racial_Ethnic_Groups.pdf

Spinoni J, Naumann G, Vogt JV (2016) Pan-European seasonal trends and recent changes of drought frequency and severity. Glob Planet Change 148:113–130

van Aalst MK, Cannon T, Burton I (2008) Community level adaptation to climate change: the potential role of participatory community risk assessment. Glob Environ Change 18:165–179

van der Linden S (2015) The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: towards a comprehensive model. J Environ Psychol 41:112–124

van der Linden S (2017) Determinants and measurement of climate change risk perception, worry, and concern. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science (April). Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Varadan RJ, Kumar P (2014) Indigenous knowledge about climate change: Validating the perceptions of dryland farmers in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Tradl Knowl 13(2):390–397

Wang J, Feng J (2023) Determinants of heterogeneous farmers’ joint adaptation strategies to irrigation-induced landslides on the Loess Plateau, China. Clim Risk Manag 41:100540

Whittaker M, Segura GM, Bowler S (2005) Racial/ethnic group attitudes toward environmental protection in California: is “environmentalism” still a white phenomenon? Political Res Q 58:435–447

Williamson TB, Parkins JR, Mcfarlane BL (2005) Perceptions of climate change risk to forest ecosystems and forest-based communities. Forestry Chron 81(5):710–716

Wright RE (1995) Logistic Regression. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, eds. Reading and understanding multivariate statistics. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. pp. 217–244

Xu J, Grumbine RE, Shrestha A, Eriksson M, Yang X, Wang Y, Wilkes A (2009) The melting Himalayas: cascading effects of climate change on water, biodiversity, and livelihoods. Conserv Biol 23(3):520–530

Xu ZX, Gong TL, Li JY (2007) Decadal trend of climate in the Tibetan plateau-regional temperature and precipitation. Hydrol Process. 22(16):3056–3065

Yang H, Luo P, Wang J, Mou C, Mo L, Wang Z, Fu Y, Lin H, Yang Y, Bhatta LD (2015) Ecosystem evapotranspiration as a response to climate and vegetation coverage changes in Northwest Yunnan, China. PLoS One 10(8):e0134795

Yang H, Villamor GB, Su Y, Wang M, Xu J (2016) Land-use response to drought scenarios and water policy intervention in Lijiang, SW China. Land Use Policy 57:377–387

Yang J, Zhang W, Feng W, Shen Y (2006) Geographical distribution of testate amoebae in Tibet and Northwestern Yunnan and their relationships with climate. Hydrobiologia 559(1):297–304

Zongxing L, Yuanqing H, Chunfen W, Xufeng W, Huijuan X, Wei Z, Weihong C (2010) Spatial and temporal trends of temperature and precipitation during 1960–2008 at the Hengduan Mountains, China. Quat Int 236(1):127–142

Acknowledgements

This research financially benefited from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 72063037). English editing from Austin G. Smith is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, HY, JH; Methodology, HY, JH, ZL, YS, JX; Data curation, HY., YS, JH; Writing—original draft, HY, JH; Writing—review & editing, HY, JH, ZL, YS, JX; Supervision, JH; Project administration, YS, JX; Funding acquisition, JH, JX. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university. Ethical clearance and approval were granted by the Professor Committee at the School of Ethnology and Sociology of Yunnan University (ethical approval no. YNU-HJ-72063037) and the Institutional committee of Centre for Mountain Ecosystem Studies of Kunming Institute of Botany (ethnic approval no. KIB-YH-107085-002).

Informed consent

Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Prior to participation, oral informed consent was obtained to ensure participants were adequately informed and voluntarily agreed to take part in the questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., He, J., Li, Z. et al. Ethnic diversity and divergent perceptions of climate change: a case study in Southwest China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 690 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03207-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03207-x