Abstract

This study employs a corpus stylistic approach to examine the functional aspect of translator style. It introduces and explores the concept of “translator’s functional style” through a case study of the Chinese-English translation of Lao She’s Er Ma. To analyze functional styles, the study develops an analytic framework that explores how different translators reconstruct the literary theme of “Diasporic Chinese” in their translations. This involves an examination of how the translators render thematic words and handle the resulting lexico-semantic patterns. The findings reveal notable disparities in the translators’ functional styles, which are influenced by multiple translatorial and extra-translatorial factors, including the translators’ backgrounds, motivations, preferences, interpretation, patronage, and technological development. The study argues that future translator style research should decrease dependence on corpus linguistic methodologies, which are meant to analyze general language features and variations, and establish an independent framework that enables more effective stylistic explorations beyond the formal aspect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Translation studies have witnessed a growing interest in translator style, which is “a kind of thumbprint that is expressed in a range of linguistic – as well as non-linguistic – features” (Baker 2000: 245). While translator style research has benefited greatly from corpus methodologies, existing work has predominantly focused on formal linguistic features, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of translator style from a functional perspective.

The present study seeks to address this gap by proposing a novel concept “translator’s functional style”, which describes translators’ linguistic idiosyncrasies when handling elements that serve specific literary functions in source texts (see Section “Translator's functional style” for details), as opposed to merely examining formal linguistic features (lexical choices, syntactic structures) in isolation from their literary functions. Unlike formal style analysis, which primarily identifies what linguistic choices translators make, functional style analysis explores how these linguistic idiosyncrasies create literary effects in the target text. This functional approach bridges stylistics and translation studies by connecting linguistic form with literary function.

Baker’s (ibid) seminal work, which investigated whether translators leave distinctive “thumbprints” in their translations independent of source texts, introduced corpus methods to translator style research. Subsequent studies have developed along two main paths: (1) target-oriented approaches comparing translated texts with non-translated texts in the same language (Laviosa 2021; Li 2016; Saldanha 2011), and (2) source-oriented approaches examining how different translators render the same source text (Afrouz 2021; Wu et al. 2024; Youdale 2019).

Despite these valuable contributions, existing corpus-based studies (e.g., Li et al. 2018; Liu and Afzaal 2021; Wu and Li 2024) have generally neglected the functional dimension of translator style and lack systematic criteria for selecting stylistic indices. This tendency to focus on formal linguistic features without considering their textual functions limits our understanding of how translators shape the literary experience of translated works.

This study addresses these limitations by exploring the functional aspects of translator style in English translations of Chinese fiction. The study makes two significant contributions to the field: first, it shifts the analytical focus from formal linguistic elements to their functional roles in the target text; second, it establishes clear criteria for selecting stylistic indices based on shared literary functions rather than isolated linguistic features.

The following sections will elaborate on the limitations of existing approaches (Section “Corpus-based Translator Style Research”), introduce the theoretical framework for analyzing translator’s functional style (Section ”Corpus Stylistics and Functional Styles”), present a case study of four English translations of the Chinese novel Er Ma (Section “A case study of Chinese-English translation of Er Ma”), and discuss the implications for future research in this area (Section “Conclusion”).

Corpus-based Translator Style Research

Corpus-based translator style studies fall into two categories: T-type (target text-focused) using comparable corpora and S-type (source text-centered) using bilingual parallel corpora (Saldanha 2011; Li 2016), each requiring distinct research designs.

T-type studies

T-type studies compare the stylistic features of translations produced by one translator with those of another, and/or with a reference corpus of non-translated texts in the same language and genre. Such studies (e.g., Saldanha 2011; Wang and Li 2020; Wu and Li 2024) utilize comparable corpora and focus exclusively on target texts, analyzing formal linguistic features and their statistics (e.g., Standardized Type-Token Ratio [STTR], mean sentence length [MSL], mean word length [MWL]). These analyses employ either “one-to-many” mode (same source text) or “many-to-many” mode (different source texts).

Various T-type studies (e.g., Li et al. 2018, Wu and Li 2024) have compared the styles of different translators working on the same or different source texts, using a translated text or reference corpus as a benchmark. These studies exhibit differences in corpus design and stylistic indices selection, resulting in three variants (Fig. 1).

The first variant (TV-I) employs the many-to-many mode to investigate translators’ styles using three specific stylistic indices suggested by Baker (2000): STTR, MSL, and reporting verbs (e.g., say, tell). Studies within TV-I (e.g., Baker 2000; Saldanha 2011) compare styles across multiple translations of source texts differing in languages and/or genres with those of other translators, analyzing these stylistic indices through comparable corpora. The primary objective of TV-I studies is to determine whether translators leave identifiable “thumbprints” in translations.

The second variant (TV-II) explores translators’ styles using a broader range of formal stylistic indices, including those utilized in TV-I studies. TV-II adopts the one-to-many mode and analyzes various stylistic indices (e.g., STTR, reporting verbs, contractions, italics), thus offering greater flexibility in index selection. Some studies in this variant, such as Wang and Li (2020) and Wu and Li (2024), aim to identify stylistic diversities among translators working on the same source text and examine the sociocultural factors influencing these differences.

The third variant (TV-III) combines elements of both TV-I and TV-II studies. While TV-III uses the same indices as TV-I, it adopts the one-to-many mode typical of TV-II studies. Although TV-III studies (e.g., Li 2016; Olohan 2004) utilize the same stylistic indices as TV-I, they differ due to their modes of analysis. Furthermore, TV-III studies are distinct from TV-II as they focus on a narrower range of stylistic indices while employing the one-to-many mode.

S-type studies

S-type studies investigate how translators transfer stylistic features from source texts to target texts and analyze variations among different translators using bilingual parallel corpora. These studies operate in two modes: single mode (e.g., Chen and Li 2023; Huang 2015; Liu et al. 2022), using one parallel corpus with multiple target texts to examine linguistic features like contractions and discourse presentation; and multiple mode (e.g., Winters 2007, 2013), involving two or more sets of parallel corpora for analysis within and across sets. Many S-type studies (e.g., Afrouz 2021; Huang 2014; Liu et al. 2022) have explored translators’ management of linguistic features and resulting diversities in target texts. Unlike T-type studies, variations in S-type studies primarily stem from the nature of stylistic indices (formal vs. functional) rather than quantity, resulting in two variants (see Fig. 1).

The first variant (SV-I) explores translator style by examining how translators handle formal stylistic features (e.g., lexical and syntactic features) of the source text in translation. SV-I studies compare different translators’ styles using a predefined set of formal linguistic features identified in the source text as a benchmark. Deviations in these features within the target texts from those in the source text are indicative of translator style. Additionally, some SV-I studies (e.g., Chen and Li 2023; Liu and Afzaal 2021; Munday 2008) analyze stylistic differences between translators working on the same source text and consider various sociocultural factors contributing to these differences.

The second variant (SV-II) investigates how different translators reproduce literary functions (e.g., viewpoints, ironic effects) of the source text in their translations. SV-II studies extend beyond formal linguistic features, examining how translators handle literary functions associated with these features and the resultant stylistic nuances. This marks a significant shift from Baker’s (2000) proposal, which used formal linguistic features as indicators of style. However, many SV-II studies (e.g., Huang 2014; Winter 2013) have been limited, focusing on “smaller/local” literary functions such as viewpoints, ironic effects, and character speech, while overlooking “bigger/global” functions like thematic construction, characterization, and fictional world building. This limitation will be further discussed in Section “Translator's functional style”.

Potential limitations

Although existing translator style research has offered meaningful insights from various perspectives (i.e., source/target-oriented) using different corpus designs (i.e., comparable, parallel), it faces several significant limitations. First, the functional aspect of translator style has been largely overlooked, with most studies (excluding SV-II studies) focusing exclusively on formal aspects, such as lexical and syntactic features and their statistics. This overemphasis on formal features fails to capture how translators reconstruct broader literary functions like thematic development, characterization, and fictional world building. Even when functional aspects are considered in SV-II studies, they tend to focus on localized effects (e.g., viewpoints, irony) rather than these larger literary functions that shape the overall narrative.

Second, the criteria for selecting stylistic indices in most studies (see Sections “T-type studies” & “S-type studies”) are often not clearly defined, posing challenges for comparing results across different studies. This methodological inconsistency stems from corpus linguistics’ general-purpose approach to language analysis, which may not be optimal for examining translator-specific stylistic features. The arbitrary selection of stylistic indices - whether they are type-token ratios, sentence lengths, or specific lexical items - often lacks theoretical justification for their relevance to translator style. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when attempting to establish patterns or draw conclusions about translator style across different studies or contexts.

Third, current corpus-based approaches tend to isolate linguistic features from their broader literary contexts, potentially missing the complex interplay between formal choices and their functional impacts. This reductionist approach may oversimplify the multifaceted nature of translator style, particularly in literary translation where stylistic choices often serve multiple functions simultaneously.

To address these limitations, adopting the corpus stylistic method could be beneficial. This approach emphasizes the functional aspect of translator style and establishes clear connections between selected stylistic indices that represent translator style through function. Unlike traditional corpus-based approaches, it provides a theoretical framework for selecting and analyzing stylistic features based on their contribution to literary functions. The subsequent section will introduce this method and explore how it can effectively investigate the functional aspect in translator style research.

Corpus Stylistics and Functional Styles

Corpus stylistic theories and methods

Corpus stylistics is a field of corpus linguistics that focuses on style-related research questions and analytic frameworks (McIntyre and Walker 2019). Corpus stylisticians (e.g., Louw and Milojkovic 2016; Mahlberg 2013; McIntyre 2015; Semino et al. 2004) have attempted to link linguistic description with literary appreciation by exploring various textual patterns and their potential functions in literary works.

Hunston (2010) defines a textual pattern as meaningful repetitions of linguistic units, such as words, clusters, structures, and sounds, which in literary texts are significant as they can fulfill various literary functions. Some corpus stylistic research (e.g., Culpeper 2009; Fischer-Starcke 2006) aligns with SV-II studies by focusing on the literary functions of single textual patterns like character speech, viewpoints, and ironic effects. However, these studies primarily concentrate on source texts, whereas SV-II studies also analyze translated texts. Other corpus stylistic studies (e.g., Čermáková 2015; Mahlberg 2013; Mastropierro 2018) have adopted a more holistic approach, moving beyond isolated textual patterns to examine literary functions across multiple patterns. These studies typically begin by identifying keywords or key clusters, then categorize their collocates within a fixed span (e.g., L5:R5) into various semantic domains and sub-domains using varying classification models. This methodological approach reveals the potential literary functions these elements may serve, such as forming the building blocks for fictional worlds (Mahlberg and McIntyre 2011), enhancing characterization and character relationships (Mahlberg 2013), or constructing fictional themes (Mastropierro 2018).

Corpus stylistic studies offer a functional perspective on literary works through textual pattern analysis (Mahlberg 2013; Mastropierro 2018; McIntyre 2015). Applied to translation studies, this approach reveals translators’ stylistic idiosyncrasies, developing the concept of translators’ functional style.

Translator’s functional style

Drawing on corpus stylistic theories and methods, the study proposes a new concept called “translator’s functional style”, which is defined as the linguistic idiosyncrasies that translators show in target texts when they reshape the literary functions of source texts. The position of functional style studies within translator style research, and its relationship with T-/S-type studies, is depicted in Fig. 2.

Translator functional style research distinctly differs from T-type and S-type studies, yet it shares some similarities with the second variant of S-type studies (SV-II) due to its focus on functional aspects. Unlike T-type studies and the first variant of S-type studies (SV-I), which prioritize the formal aspects of language, functional style research emphasizes the functional aspects. Moreover, it diverges from SV-II studies by concentrating on “bigger/global” literary functions such as thematic construction, fictional world building, and characterization. In contrast, SV-II studies tend to focus on “smaller/local” functions like creating humorous effects, expressing viewpoints, and presenting discourse, which serve as building blocks for these “bigger/global” functions.

To demonstrate the investigation of functional style in actual research, the study outlines three main steps of its analytical process:

Step 1: Select key words/clusters and determine their collocate span (e.g., L5:R5) to identify textual patterns in the source text. Classify these keywords using appropriate models such as Mahlberg and McIntyre’s (2011) “fictional world signals” and “thematic signals”, and Johnson’s (2016) “aboutness indicators” (plot-related elements including participants, circumstances, abstract concerns, verbal groups) and “narrative strategies” (time references, negation, reflexive/personal references). Then identify literary functions attached to the textual patterns and semantic domains formed by these keywords/clusters.

Step 2: Examine translators’ stylistic idiosyncrasies by analyzing how they replicate the original literary functions in their translations. These idiosyncrasies reveal translators’ functional styles, which emerge from differences between source text and translations or among multiple translations of the same source.

Step 3: Interpret findings by analyzing factors behind stylistic variations among translators. As translator style research concerns human agents, explore both translatorial factors (translators’ backgrounds, motivations, preferences) and extra-translatorial factors (sociocultural influences, patronage) that may impact stylistic choices.

A Case Study of Chinese-English Translation of Er Ma

This section presents a case study examining translators’ functional styles in Lao She’s novel Er Ma (二馬). As a renowned Chinese author, Lao She is celebrated for his vivid portrayals of lower-class Chinese suffering during the 1920s (Jimmerson 1991). Er Ma was selected for this study because its London setting presents unique translation challenges involving racial terminologies that reveal translators’ linguistic choices and thus their functional styles when navigating cross-cultural representation for different target audiences.

Following established corpus stylistic methodologies (Mahlberg 2013; Mastropierro 2018), the following case analysis begins by identifying key thematic words from the Chinese source text. Previous studies of Er Ma (Wen 2000; Witchard 2012) have identified “Diaspora Chinese” as an important literary theme, which serves as an entry point for identifying these thematic words, and also the foundation for investigating translators’ functional styles.

Two thematic words were selected for analysis: “中國人” (the Chinese) and “黃臉” (the yellow face). These words were chosen for three primary reasons: first, they directly connect to the diaspora theme; second, their thematic relevance is reflected in their high frequency in the original text; and third, their varied translations across different versions highlight distinct translator approaches.

Having identified the key thematic words, the following part outlines the methodological details of the case analysis, including source and target texts, research questions, and analytical framework employed to systematically investigate the translators’ functional styles.

Methodology

Source and target texts

The source text of Er Ma in Chinese was published by People’s Literature Publishing House in 1998. The study employs the Jieba Python package for segmenting the Chinese source text into manageable tokens, with the results manually proofread for accuracy. The target texts include all four published English translations of Er Ma by M. J. James, K. K. Huang & D. Finkelstein, J. Jimmerson, and W. Dolby. Table 1 provides details of these translations.

The texts were initially obtained in hardcopy and subsequently converted into txt files using OCR. These txt files were then proofread against the hardcopies to ensure accuracy and reliability. Table 2 presents the basic corpus statistics for these translations, including token count, type count, STTR, MSL, MWL. These metrics provide an initial overview of the corpus data.

Table 2 shows both similarities and differences across the four Er Ma translations. Token counts increase progressively from 95,689 in Ma and Son to 109,843 in The Two Mas. Type counts also rise, indicating greater lexical diversity in later versions. STTR remains consistent (41.77–43.81), with Mr. Ma & Son showing the highest lexical variety. MWL stays stable at approximately 4.2 across all translations. The most significant difference is MSL, with The Two Mas featuring a markedly higher value (37.63) compared to others (below 15), suggesting more complex sentence structures.

Research questions

To examine translators’ functional styles as they reconstruct “Diasporic Chinese” in translation, the following research questions (RQs) are raised:

RQ1: How do the two thematic words interact linguistically with their contexts to develop the theme of “Diasporic Chinese” in Er Ma?

RQ2: How do the translators’ functional styles diverge or converge as they handle such interactions to reconstruct the theme in their English translations of Er Ma?

RQ3: What are the underlying factors that contribute to the similarities and differences between these translators’ functional styles in translation?

RQ1 examines how the thematic words interact with their contexts to construct the theme in the source text. RQ2 explores translators’ functional styles as they handle the interactions between the thematic words and their contexts in target texts. RQ3 investigates translatorial and extra-translatorial factors that contribute to these functional styles.

Analytic framework

As shown in Fig. 3, the study develops an analytic framework to guide the selection of stylistic indices representing translators’ functional styles in reconstructing “Diasporic Chinese”. The framework focuses on thematic word renditions and resulting lexico-semantic patterns across translations. These elements are crucial for thematic reconstruction and effectively reflect translators’ styles: thematic word renditions show initial efforts to reconstruct “Diasporic Chinese”, while lexico-semantic patterns demonstrate how translators portray these characters within broader contexts.

Lexico-semantic patterns are examined through semantic fields (collocates with the same semantic preference) and lexical chains (cohesive webs created by thematic words). While Sinclair (2004) defines semantic fields, lexical chains require clarification. Lexical chains are essential for analyzing cohesion and identifying thematic patterns in translations. They form when semantically related words create cohesive networks throughout a text. In this study, randomly sampled paragraphs containing keywords are examined to demonstrate thematic continuity. Mere word presence doesn’t establish causal relationships; careful analysis of co-occurrence within semantic fields is required. Mastropierro (2018) demonstrated lexical chains’ value in translation studies by examining how translators maintain or modify original chains. Establishing meaningful lexical chains requires analyzing contextual and semantic relationships rather than presuming correlations, providing deeper insights into translators’ functional styles beyond word placement. By combining lexical-oriented (chain) and semantic-oriented (field) analyses, Section “Results” presents a comprehensive analysis of translators’ functional styles across different English translations of Er Ma.

Results

Renditions of thematic words

Table 3 shows the translators’ renditions of the two thematic words: “中国人” as “Chinese”, “Chinamen”, or “Chink” and “黃臉” as “yellow face”, “yellow-faced”, “yellow devils”, or “yellow-skinned”. However, these renditions alone don’t fully capture the translators’ styles. Quantitative analysis using normalized frequencies (per million) provides deeper insights. The fiction subsets of BNC (1980s-1993) and COCA (1990–2017) serve as reference corpora, chosen because they represent diverse English genres and correspond to when the translations were produced.

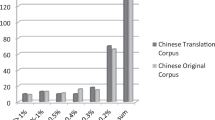

AntConc 4.0 was used to retrieve raw frequencies of the two thematic words from the corpus, with MS Excel employed for the “per million” normalization. Data analysis reveals three significant trends. First, all translators over-translate both words compared to reference corpora. Second, translators show varying frequency tendencies relative to the source text (ST). They consistently decrease “黃臉” frequency, with Huang & Finkelstein showing the lowest percentage of ST equivalents (57.01%) and Dolby the highest (74.28%). Conversely, they substantially increase “中国人” frequency in translation, with James showing the highest percentage (127.40%) and Dolby the lowest (107.72%). Third, James’ renditions of “中国人” carry the highest negativity percentage (15.28%) through “Chinamen” and “Chink” usage, while Huang & Finkelstein’s carry the lowest (2.90%). Jimmerson and Dolby show intermediate values at 6.58% and 7.10% respectively. These quantitative findings provide insights into the translators’ functional styles when reconstructing the concept of “Diasporic Chinese” in Er Ma through thematic word rendition.

Reconstructions of semantic fields

The construction of the “Diaspora Chinese” in the source text is shaped by the lexico-semantic patterns of the two thematic words “黃臉” and “中國人”. By analyzing the semantic preferences of each word within the concordance span of L10:R10, a range shown by repeated pilot studies to capture all relevant contextual information without redundancy, we can delineate the semantic fields they form and the contextual insights they offer. Concordance analyses of these words in the source text reveal that they share four semantic fields, as detailed in Table 4.

The first semantic, labeled as General Negativity, portrays Chinese diaspora as sick and unpleasant. For “黃臉”, collocates include “又黃又腫” (yellow and swollen) and “抽大煙” (opium smoking); for “中國人”, collocates include “討人嫌” (annoying) and “髒臭” (dirty and smelly).

The second shared field, Treachery, Crime, Peril, depicts Chinese diaspora as criminals committing violent acts. Evidenced by collocates like “強盜” (robber) and “暗殺” (assassination) with “中國人”, and “害死人” (causing death) with “黃臉”.

The third shared field, Dehumanization, intensifies negative portrayal by depicting Chinese as monstrous, non-human beings. Collocates include “東西” (thing), “沒鼻子” (no nose), and “怪物” (monster) with “黃臉”, as well as “玩藝兒” (plaything) and “沒鼻子” with “中國人”.

The fourth shared field, Japanese Superiority, creates an impression where Japanese are depicted as superior to Chinese. Illustrated by collocate pairs such as “日本人-好處” (Japanese-advantage) with “黃臉” and “日本人-體面” (Japanese-respectable) and “日本人-造大炮” (Japanese-making cannons) with “中國人”.

The study finds that all translators maintain these four semantic fields when reconstructing “Diasporic Chinese” in translation, as shown in Table 5, which uses the same color scheme as Table 4 to represent semantic components. However, the frequency and semantic intensity of collocates in these fields vary from the source text and differ between translators. These variations reflect translators’ distinctive approaches to thematic reconstruction of “Diasporic Chinese” and thus their functional styles.

Quantitatively, these deviations are demonstrated by the proportional differences of semantic components across the four semantic fields. Figure 4 displays these deviation scores, detailing the labels and proportions of the semantic components within the fields. Deviation scores are calculated by assessing the proportional differences of each semantic component between the source text (ST) and a target text (TT) across all semantic fields. Analysis reveals distinct functional styles in reconstructing “Diasporic Chinese”. James shows the largest deviation (score 1.94), most notably in the Dehumanization field where he increased “Monstrousness” by 28.85% while reducing “Physicality” by the same percentage. Jimmerson exhibits the smallest deviations (score 1.23), with less than 1% differences in all components within Treachery, Crime, Peril fields and the “Monstrousness” component. Huang and Finkelstein’s deviation score is 1.46, while Dolby’s is 1.32. These results indicate James deviates most significantly from the ST in reconstructing “Diasporic Chinese”, while Jimmerson maintains closest fidelity to the original semantic proportions.

Some ST-TT proportional differences may stem from obligatory translation shifts or L10:R10 span limitations in capturing collocates. However, others likely reflect translators’ deliberate manipulations. Examining these manipulations through the following ST-TT bilingual contextual evidence reveals instances where translators alter collocate semantic intensity, providing insight into their functional styles.

Example (1) | Example (2) |

[ST] 設若普通英國人討厭中國人, 有錢的英國男女是拿中國人當玩藝兒看 [James] If ordinary Englishmen dislike the Chinese, rich Englishmen regard the Chinese as amusing. [H & F] If the ordinary Englishman despised Chinese, wealthy English men and women regarded them as mere objects of amusement. [Dolby] If the average English person detests the Chinese, the wealthy, men and women alike, regard the Chinese objects of amusement. [Jimmerson] If you were to say that ordinary classes in English society detested the Chinese, then the wealthy classes on the other hand, saw them as objects of amusement. | [ST]…於是中國人就變成世界上最陰險, 最污濁, 最討厭, 最卑鄙的一種兩條腿兒的動物! [James]…and so the Chinese have been transformed into the most sinister, filthy, repulsive, debased creatures on two legs in the whole world! [H & F] Thus, the Chinese became the most inscrutably dangerous, filthy, disgusting, and despicable two-legged creatures in the world. [Jimmerson] Hence, Chinese have been made the most treacherous people in the world, the foulest, disgusting, contemptible beasts to walk on two legs! [Dolby] Thus are the Chinese transformed into the most sinister, most foul, most loathsome and most degraded two-legged beasts on earth. |

Example (3) | Example (4) |

[ST] 姐姐, 你知道, 我父親那一輩的中國人是被外國人打怕了, 一聽外國人誇獎他們幾句, 他們覺得非常的光榮。 [H & F] Sister, you know that my father’s generation of Chinese has been so intimidated by foreigners that just a few words of praise from a Westerner fills them with pride. [James] Sister, you know the Chinese of my father’s generation have been terrorized by the foreigners. They hear foreigners praise them and they feel they have been extraordinarily glorified. [Dolby] You know, Elder Sister, my father’s generations had the scares put into them by foreigners, and all they need is to hear those same foreigners bestowing faint praise and they feel tremendously honoured. [Jimmerson] Sister, you know how his generation of Chinese have been psychologically crippled by foreigners—all it takes is a few words of praise from a foreigner and he’s overwhelmed, beaming with honor. | [ST]沒到過中國的英國人, 看中國人是陰險詭詐, 長著個討人嫌的黃臉。 [H & F] To Englishmen who have never been to China, the Chinese are a treacherous and deceitful race, with yellow faces capable only of arousing disgust. [James]Englishmen who have never gone to China think the Chinese are yellow-faced clandestine schemers who always arouse suspicion. [Dolby] English people who’ve never been to China picture the Chinese as sinister, underhand beings with disagreeable yellow faces. [Jimmerson] For the English who’ve never been to China, Chinamen are unsightly, yellow-faced creatures, notoriously sinister and cunning. |

Example (1) shows how James uniquely depicts diasporic Chinese, revealing her distinctive functional style. While all translators reduce the negative sentiment of “玩藝兒” (toy), James’s rendition as “amusing” (versus others’ “objects of amusement”) transforms “contemptible” Chinese in the ST into active “entertainers” for “rich Britons”, rather than the “lifeless” objects portrayed in other translations. This idiosyncrasy partly explains James’s highest deviation score (1.94), as her translation weakens the dehumanization effect compared to other translators who largely preserve it.

Example (2) shows Huang & Finkelstein’s unique reconstruction of “treachery” associated with diasporic Chinese. While James, Jimmerson, and Dolby preserve the ST collocate “陰險” (insidiousness) using “sinister”, “treacherous”, and “sinister” respectively, Huang & Finkelstein choose “inscrutably dangerous.” This intensifies the original term’s semantic impact through the addition of “dangerous”, creating a more intimidating tone that reinforces the insidiousness attributed to Chinese characters. This distinctive choice is reflected in their translation having the second-highest proportional deviation in the “Treachery” component among all four translations (see Fig. 4).

Example (3) reveals Jimmerson’s functional style through her translation of “打怕了”, a Chinese collocate expressing mental paralysis from repeated defeats. While other translators use fear-based terms like “intimidated”, “terrorized”, and “scared”, Jimmerson uniquely renders it as “psychologically crippled”, better preserving the original’s semantic intensity by suggesting mental breakdown. This choice partly explains her translation’s lowest deviation score (1.23) and highlights her distinctive approach. Her stylistic idiosyncrasy brings target readers closer to the original text, offering clearer insight into the mentality attributed to Chinese diaspora in Er Ma.

Example (4) shows how Dolby and Jimmerson stylistically differ from James and Huang & Finkelstein when translating “討人嫌” (repulsive), a negative ST collocate characterizing Chinese people in Er Ma. While Huang & Finkelstein and James use “disgust” and “suspicion” respectively, Dolby and Jimmerson opt for “disagreeable” and “unsightly.” These latter choices create slightly weaker semantic intensities that better reproduce the original meaning of unpleasant impressions, whereas “disgust” intensifies and “suspicion” diverges from the original. This shared approach by Dolby and Jimmerson demonstrates their greater preservation of the original “Diasporic Chinese” construction, reflected in their relatively low overall proportional deviation scores, as shown in Fig. 4.

Recreations of lexical chains

Lexical chains are the ways “lexical items relate to each other and to other cohesive devices so that textual continuity is created” (Flowerdew, Mahlberg (2009): 1). In the analytic framework (Fig. 3), it is another aspect to be explored to uncover these translators’ functional styles. This study hypothesizes that translators’ varied renditions of thematic words may disrupt the source text’s original lexical chains, revealing their distinctive approaches. The analysis specifically examines how these disruptions to thematic word chains manifest across different translations.

The analysis focuses specifically on “中國人” due to its high frequency (235 ST occurrences) and diverse translations across the four versions. While all translators maintained the four semantic fields jointly created by “中國人”, and “黃臉”, they employed multiple English equivalents for “中國人”. This multiplicity weakens the original text’s cohesiveness, where the author consistently used the same term throughout. The following examples illustrate this phenomenon.

Example (5) demonstrates the original lexical chain (black arrows) created by “中國人” across six randomly-sampled paragraphs from the source text. These selections represent every 24th paragraph from the 144 containing this thematic word, presented in their original sequence with the term highlighted in yellow and relevant collocates italicized. This lexical chain establishes a cohesive pattern consistently conveying negativity toward diasporic Chinese. The first, fifth, and sixth paragraphs pair the thematic word with collocates like “弱國” (weak nation), “罪名” (accusation), “不齒” (disdain), and “沒…資格” (unqualified), all expressing British contempt. The second paragraph combines it with “拳頭” (fist) and “捶死” (beat to death), reflecting vehement British aversion. The third paragraph’s repeated occurrences evoke troubled sentiments toward Chinese people, while the fourth paragraph conveys dehumanization. Together, these paragraphs create a coherent negative portrayal of the Chinese diaspora in Er Ma.

The lexical chain built around “中國人”is disrupted across all four translations due to varied renditions including “Chinese”, “Chinamen”, or “Chink”. Examples (6) and (7) show how both James and Jimmerson employ these three different translations for the same source term. Although the negative semantic associations remain intact through the italicized collocates, the resulting semantic fields become fragmented as they stem from multiple nodes rather than the single consistent term used in the source text. This weakens the connections between nodes compared to the original cohesive tie, potentially altering target readers’ perception of the Chinese diaspora portrayed in the translations.

In James’ translation (Example 6), “中國人” is rendered as “Chinamen” (in grey) eight times and “Chink” (in green) once, rather than the literal “Chinese”. This completely disrupts the original lexical chain and likely reinforces racial stereotypes among target readers. Jimmerson’s translation (Example 7) shows a similar but less pronounced pattern, using “Chinamen” three times and “Chink” once. While less disruptive than James’ approach, these choices still partially interrupt the source text’s lexical cohesion and potentially heighten negative perceptions of Chinese characters. Both translation strategies alter the original textual continuity established through consistent terminology in the source text.

Dolby’s translation (Example 8) partially disrupts the original “中國人” lexical chain by occasionally using “Chinamen”, which may evoke racial connotations. However, this tendency is less pronounced than in James’ or Jimmerson’s translations, as Dolby preserves over 70% of the chain by using “Chinese” seven times. This partial disruption still weakens the cohesive focus found in the source text’s consistent terminology or in James’s frequent use of “Chinamen”.

In contrast, Huang & Finkelstein’s translation (Example 9) renders “中國人” accurately and consistently throughout, fully preserving the original lexical chain. This approach likely produces an interpretive effect on target readers closest to that of the source text, maintaining the original cohesive structure and semantic relationships established by the consistent use of a single term.

The translators’ functional styles are most distinct when comparing James’ and Huang & Finkelstein’s approaches. James’ translation aligns with Baker’s (2011) and Mastropierro’s (2018) observation that random lexical selection can fail to construct contextually appropriate cohesion. By translating “中國人” variously as “Chinese”, “Chinamen”, and “Chink”, James disrupts the original lexical chain and cohesion. In contrast, Huang & Finkelstein consistently render “中國人” as “Chinese”, preserving the source text’s original lexical chain. This fundamental difference in translation strategy illustrates opposing approaches to maintaining textual cohesion and reflects each translator’s distinctive functional style when handling culturally charged terminology.

Discussion

The study reveals varying functional styles among translators reconstructing the “Diaspora Chinese” theme. Jimmerson maintains fidelity to the original, while Huang & Finkelstein and Dolby make fewer efforts to preserve it. James shows the greatest deviation. These stylistic differences stem from translators’ backgrounds, motivations, preferences, interpretations, patronage, and technological development—factors explored in the following discussion addressing the third research question (RQ3).

A translator’s background, such as nationality and mother tongue, considerably influences his/her styles in translation. Such influence is particularly evident in Huang & Finkelstein’s translation. Table 1 reveals that Huang, an overseas Chinese residing in the US, is the only native Chinese speaker among all the translators. According to Li (2016), faithfulness to the original text has traditionally been the main criterion for evaluating translation quality among Chinese translators. Thus, it can be inferred that Huang’s English translation is more likely to prioritize literal translation. This could explain why Huang and Finkelstein’s collaborative translation closely aligns with the original construction of “Diaspora Chinese”. In contrast, the other three translators are either British or American, with English as their mother tongue. Consequently, faithfulness to the original text and maintaining a style similar to the original may not be the primary considerations driving their translation strategies.

Translation motivation, shaped by sociocultural and sociopolitical contexts, significantly influences translators’ styles (Hatim and Mason 2014). Jimmerson’s translation, published by China’s Foreign Languages Press (FLP), reflects China’s international promotion agenda during the reform era. Her adherence to the source text aligns with FLP’s “courageous and decisive” approach to promoting Chinese literature (http://flp.com.cn/about/history/), suggesting an intent to present Chinese thought and culture accurately to English-speaking readers. Similarly, Huang and Finkelstein’s stated motivation to “improve mutual understanding between China and other nations of the world” (Huang and Finkelstein 1984: ix) explains their faithful translation strategy. Both cases demonstrate how institutional and personal motivations during China’s reform and opening-up period influenced translation choices that prioritized fidelity to the source text.

Translators’ wording preference is another factor that influences their functional styles. James’ inclination toward American English caused her translation to diverge from the source text’s semantic field. She admitted that despite efforts to preserve the original style, her American background led her to “subconsciously used American English” in translation (James 1980). Marney (1982) confirms that while James’ translation maintains content fidelity, its diction leans toward American English, contributing to her substantial deviation from the original “Diaspora Chinese” construction. Similarly, Dolby’s preferences influence his functional style. In his preface, he explicitly states his preference for the Wade-Giles Romanization system and other earlier systems over the now-standard Pinyin for English translations of Chinese names and places (Dolby 2013). This preference partly explains how his translation deviates from the thematic construction in the source text, demonstrating how personal linguistic choices significantly impact translation outcomes.

The translator’s personal interpretation of the original work is also a key factor that influences these translators’ functional styles. James’ understanding of Er Ma exemplifies this effect. She believed the novel portrayed British attitudes toward Chinese people from a Chinese perspective—a technique highlighting British stereotypes (James 1980). To replicate this technique, James added terms like “Chink” that were absent in the source text. This choice substantially altered the original lexical chains, affecting how the “Diasporic Chinese” theme was represented in translation. Thus, a translator’s interpretation directly impacts the manifestation of their functional style, creating significant deviations from the source text’s lexical and thematic constructions.

Diverse patronage with unique publicity and language policies influences translator style. Lefevere (2016) describes patronage as powers (individuals, institutions) that can promote or obstruct literary practices. The four patrons have distinct agendas: FLP promotes Chinese literature “courageously and decisively”, Joint Publishing emphasizes “humanistic care and lifestyle taste” (https://jointpublishing.com/homepage.aspx), Penguin Classics aims to create “books for everyone, a book can change anyone” (https://www.penguin.co.uk/company/about-us/our-publishing), and the Chinese Material Center focuses on “cultural exchange and promotion” (James 1980). Jimmerson’s translation, supported by a mainland Chinese publisher, adopts a positive image of China by translating “中國人” as “Chinese” instead of “Chinks” or “Chinamen.” She also uses Mandarin Pinyin (e.g., “Li Zirong”, “Ma Zeren”), whereas others use Wade-Giles or Yale, demonstrating how patronage shapes a translator’s functional style.

In today’s AI-driven era, translation resources and technologies significantly shape translators’ styles. In the 1980s, James and Huang & Finkelstein relied on paper dictionaries when translating Mr. Ma and Son (Beyer 1983). These technological limitations forced greater dependence on personal experience, resulting in purer individual styles. By the 1990s, expanded resources and tools transformed translation methods and improved efficiency, affecting stylistic expression (O’Hagan and Ashworth 2002). Jimmerson’s translation emerged during this transition, likely reflecting these technological influences. The 21st Century brought digital resources, search engines, and AI tools that dramatically enhanced translation efficiency. The emerging human-machine collaborative model has merged personal experience with technology, affecting translator style. This partly explains why Dolby’s translation differs markedly from others—a distinction possibly attributable to the technological and resource disparities across different eras

Apart from these factors that explain the stylistic differences, the study’s functional approach offers advantages over traditional corpus-based methods in analyzing translator style. While corpus-based approaches excel at identifying formal linguistic patterns through statistical analysis (type-token ratios, sentence lengths), they often fail to connect these features to broader literary functions like thematic construction. A purely statistical analysis might identify James’ varied lexical choices or Dolby’s unique romanization system, but would miss how these choices systematically impact the “Diaspora Chinese” theme. The functional approach, in contrast, reveals how seemingly isolated linguistic choices accumulate to create distinct thematic effects, as demonstrated in Jimmerson’s consistent translation of “中國人”as “Chinese” versus James’ varied terminology including “Chink”, which significantly affects thematic coherence.

Conclusion

Drawing on corpus stylistic theories and methods, this study introduces and analyzes the concept of “translator’s functional style” through a case study of the Chinese-English translation of Er Ma. It advances translator style research by focusing on functional aspects through thematic reconstruction and develops an analytical framework (Section “Analytic framework”) with specific stylistic indices selection criteria.

The framework, initially applied to “Diasporic Chinese” in Er Ma, has universal applicability across translator functional style studies. It guides stylistic indices selection for thematic reconstruction regardless of cultural or literary context. By analyzing thematic word renditions and lexico-semantic patterns in any translation, it reveals translators’ stylistic decisions and interpretations, making it a versatile tool for exploring functional styles in diverse literary translations.

However, this study focuses solely on thematic reconstruction, neglecting fictional world building and characterization. Future research should examine how translators manage multiple literary functions simultaneously for deeper functional style insights. Integrating translation universals (explicitation, simplification) with functional style analyses would enrich translator style understanding. Additionally, developing frameworks beyond corpus linguistics’ general language features would enable more effective stylistic exploration beyond formal aspects.

References

Afrouz M (2021) Investigating literary translator’s style in span of time: The case of Sa ‘di’s Gulistan translated into English. Lebende Sprache. 66(2):214–230. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2021-0016

Baker M (2000) Towards a methodology for investigating the style of a literary translator. Target 12(2):241–266. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.12.2.04bak

Baker M (2011) In other words: a coursebook on translation, 2nd edn. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203133590

Beyer J (1983) Jean M. James (tr.): Ma and son, a novel by Lao She. [iii], 268 pp. San Francisco: Chinese Materials Center, Inc., 1980. $21.80. Bull. Sch. Orient Afr. Stud. 46(1):182–183. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0041977x00077892

Čermáková A (2015) Repetition in John Irving’s novel A Widow for One Year: A corpus stylistics approach to literary translation. Int J. Corpus Linguist 20(3):355–377. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.20.3.04cer

Chen F, Li D (2023) Patronage and ideology: a corpus-based investigation of Eileen Chang’s style of translating herself and the other. Digit Scholarsh. Humanit 38(1):34–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqac015

Culpeper J (2009) Keyness: Words, parts-of-speech and semantic categories in the character-talk of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Int J. Corpus Linguist 14(1):29–59. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.14.1.03cul

Fischer-Starcke B (2006) The phraseology of Jane Austen’s Persuasion: phraseological units as carriers of meaning. ICAME J. 30:87–104

Flowerdew J, Mahlberg M (eds) (2009) Lexical cohesion and corpus linguistics, vol 17. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.17

Hatim B, Mason I (2014) Discourse and the translator. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315846583

Hunston S (2010) How can a corpus be used to explore patterns? In: O’Keeffe A, McCarthy M (eds) The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics. Routledge, London, pp 152-166. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203856949-12

Huang L (2014) Discourse presentation in English translations of Luotuoxiangzi: a corpus-based study of translator style. J. PLA Univ. Foreign Lang. 37(1):72–80

Huang L (2015) Style in translation. In: Style in translation: a corpus-based perspective. Springer, Berlin, pp 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-45566-1

James JM (1980) Ma and son: a novel by Lao She. Chinese Materials Center Inc, San Francisco

Johnson JH (2016) A comparable comparison? A corpus stylistic analysis of the Italian translation of Julian Barnes’ Il Senso di una Fine and the original text the sense of an ending. Lang. Lit. 25(1):38–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947015623360

Laviosa S (2021) Corpus-based translation studies: theory, findings, applications, vol 17. Brill, Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004485907

Lefevere A (2016) Translation, rewriting, and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge, London

Li D (2016) Translator style: a corpus-based approach. In: Ji M, Oakes M, Li D, Hareide L (eds) Corpus methodologies explained: an empirical approach to translation studies. Routledge, London, pp 103-136. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315694122

Li D, He W, Hou L (2018) A corpus-based study of Julia Lovell’s translating style. Foreign Lang. Teach. 39(1):70–76

Liu K, Afzaal M (2021) Translator’s style through lexical bundles: a corpus-driven analysis of two English translations of Hongloumeng. Front Psychol. 12:633422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633422

Liu K, Cheung JO, Moratto R (2022) Lexical bundles in the fictional dialogues of two Hongloumeng translations: a corpus-based approach. In: Advances in corpus applications in literary and translation studies. Routledge, pp 229-253. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003298328-14

Louw B, Milojkovic M (2016) Corpus stylistics as contextual prosodic theory and subtext, vol 23. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1075/lal.23

Mahlberg M, McIntyre D (2011) A case for corpus stylistics: Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale. Engl. Text. Constr. 4(2):204–227. https://doi.org/10.1075/etc.4.2.03mah

Mahlberg M (2013) Corpus stylistics and Dickens’s fiction. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203076088

Marney J (1982) Review: Lao She. Ma and Son. Jean M. James, tr. San Francisco. Chinese Materials Center. World Lit. Today 56(1):176–177

Mastropierro L (2018) Corpus stylistics in Heart of Darkness and its Italian translations. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

McIntyre D (2015) Towards an integrated corpus stylistics. Top. Linguist 16(1):59–68. https://doi.org/10.2478/topling-2015-0011

McIntyre D, Walker B (2019) Corpus stylistics: theory and practice. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474413220

Munday J (2008) Style and ideology in translation: Latin American writing in English. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203873953

O’Hagan M, Ashworth D (2002) Translation-mediated communication in a digital world: facing the challenges of globalization and localization. Multilingual Matters, Clevedon. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853595820

Olohan M (2004) Introducing corpora in translation studies. Routledge, London https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203640005

Saldanha G (2011) Translator style: methodological considerations. Translator 17(1):25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2011.10799478

Sinclair J (2004) Trust the text: language, corpus and discourse. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203594070

Wang Q, Li D (2020) Looking for translators’ fingerprints: a corpus-based study on Chinese translations of Ulysses. In: Hu K, Kim K (eds) Corpus-based Translation and interpreting studies in Chinese contexts. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp 155-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21440-1_6

Winters M (2007) F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Die schönen und verdammten: a corpus-based study of speech-act report verbs as a feature of translators’ style. Meta 52(3):412–425. https://doi.org/10.7202/016728ar

Winters M (2013) German modal particles-from lice in the fur of our language to manifestations of translators’ styles. Perspect 21(3):427–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2012.711842

Witchard A (2012) Lao She in London, vol 1. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong. https://doi.org/10.5790/hongkong/9789888139606.001.0001

Wen RM (2000) Two Mas from the perspective of cultural criticism. Mod Chin Lit Stud 34(4):123–128

Wu K, Li D (2024) Unraveling Eileen Chang’s stylistic multiverse: insights from multivariate analysis with multifactorial design. Digit Scholarsh. Humanit 39(3):1001–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqae040

Wu K, Li D, Lei VLC (2024) On translator style. In: Li D, Corbett J (eds) The Routledge handbook of corpus translation studies. Routledge, London, pp 271-287. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003184454-20

Youdale R (2019) Using computers in the translation of literary style: challenges and opportunities. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429030345-2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kan Wu (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required because the study did not contain any studies with human participants performed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, K. Uncovering the functional aspect of translator style: corpus stylistic insights. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 842 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05123-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05123-0