Abstract

Employee job satisfaction is crucial for retaining good employees and sustaining the organization. Leaders’ ethical values and how these ethical values get translated into creating an ethical organizational culture are crucial factors in employee job satisfaction. In this study, we administered a survey questionnaire to understand how employee job satisfaction is related to the presence of ethical leadership. We also explored the mediating role of ethical culture and the moderating impact of age, gender, tenure, and age of the organization. We used leader-member exchange theory, and adapted frameworks primarily developed in a Western context and found that they are significant in the Indian context. We observed that ethical culture mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction. The analysis also revealed that Millennials and Gen-Z prefer organizations with an ethical culture. The same is true for new entrants against employees who have spent more extended periods in the same organization. We collected 210 samples from India’s micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). There were 152 male respondents, 58 female respondents, and 145 respondents in the age group of 20–30 and 65 in the range of 30–50. We used SPSS Amos to perform structural equation modeling. The results hold significant implications for managers. The research calls upon managers to create an ethical culture with clearly articulated rules. This culture should encourage dissent and punish deviations. MSME companies must move away from the leader-centric approach to conscientiously creating an ethical culture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Ethical leadership is much closer to home than we may readily admit. It is not somewhere “out there”—it is us, right here and now. It is in our deeply-held values. It is in our day-to-day choices. It is in our quest for good.” anonymous.

ME Energy is a medium-sized manufacturing company located in an arid region of Pune district. All this region’s wells run dry within a month after the monsoon. Villages around the company depend on water tankers for drinking water for the rest of the year. Immediately after setting up the factory, the company owner planted trees on the campus. Today, the 20-acre campus is lush green with trees. When they built the boundary wall, they laid thick layers of plastic along the wall. This ensured that all the rainwater collected on the company premises seeped into the earth and enriched the groundwater. They also built a tube well on the campus. The villagers surrounding the company now collect water from this well. As a result, the villages could break the perennial dependence on water tankers. On one hand, they created a good carbon sink by planting trees. They also ensured an excellent groundwater source to supply clean drinking water to the villagers. This initiative also helped the villagers to improve their economic situation. Their women do not need to wait for the water tankers and fight for the water anymore.

The owner of ME energy is a person driven by values. it is these values that has made him work for the benefit of the villagers around the company. In a country like India MSME companies contributes significantly to the economy. Many of their leaders are deeply spiritual. Such organizations create a culture of ethics and care and attract and retain good employees. Such organizations consider Employee job satisfaction higher (Mitonga Monga et al., 2019). The founder of ME Energy said that he learned these values from his parents, who viewed planting trees as a virtue. The state of Kerala is known as ‘God’s Own Country’ because of its greenery, nurtured by every household. He also said that the concept of vasudaiva kutumbakam (the world is one family) is an Indian value where one looks at the whole universe as one’s family.

MSME companies emerged in large numbers under the protective regime followed in India. After independence, the state wanted to build self-sufficiency in industrial production and created a protectionist regime. In the 1990s, when the government started taking more interest in regulating the business practices in India, the focus was on larger companies. Larger organizations viewed MSME companies as a source of low-cost producers. Larger organizations looked at them as providers of cost-effective materials. Their weak bargaining power made them easy targets for exploitation. Such an environment was instrumental in forcing the smaller companies to resort to exploitative labor practices and tax evasions to make profit. However, individual entrepreneurs tried remain ethical mainly owing to their sociocultural upbringing (Yadav, 2017; Tin et al., 2024). It is these small group of leaders who hold a beacon of light to ensure the value-based business continued.

Values again gained importance recently with the introduction of Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR) in 2021 by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). BRSR was India’s response to sustainability reporting that incorporated the ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) values. Although MSMEs are not mandated to make a BRSR report, the larger organizations encourage their smaller partners to comply with certain value-based practices. The voluntary guidelines of the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) focused on value-based business as early as the 1990s. Though not mandatory, many companies have recently started voluntarily reporting their responsible business practices (Pandey et al., 2023).

The relationship between the larger organizations and MSME companies has always been one of exploitative (Singh et al., 2018; Arruda, 2011). This exploitative relationship gets percolate into organizations culture. Often this gets reflected in the companies’ labor practices. Most workers in MSMEs are contract laborers with no labor protections. The existence of multiple and competing stakeholders adds to this problem. Such a perception necessitates MSMEs to adjust and accommodate practices that do not align with the dominant values and ethics. A recent paper using the theory of awareness, action, comprehensiveness, and excellence argues that better human resources management can make MSMEs more sustainable (Maheshwari et al., 2020). The theory says that ethical and sustainable values awareness will lead to sustainable actions. The theory argues that articulating a leader’s values and translating them into the organization’s culture help create a psychological contract between employees and employers.

Employees’ perception of their leader’s values significantly impacts the employee’s job happiness and the organization’s overall effectiveness (Bello et al., 2018). Iyer and Ravichander (2013) called upon the business leaders to adopt higher ethical standards. MSMEs are predominantly leader-led and person-centric organizations. Since most of these are family businesses, the leader’s values become the organization’s values (Al Halbusi et al., 2022; Hair et al., 2017). The owner’s leadership styles directly impact the performance of employees in these organizations (Sorenson, 2000; Joseph et al., 2020). A similar study by Villaluz and Hechanova (2019) established the role of leadership in creating a particular culture in the organization.

We can use social exchange theory to explain the relationship between leadership ethical values and employee job satisfaction. The theory says that individuals observe others and imitate their behavior. Employees emulate the ethical practices of their leaders. Kim and Vandenberghe (2021) used social exchange theory to discuss the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational commitment. Babič (2014) associated ethical leadership with the leader-member exchange (LMX) theory. Gu et al. (2015) applied this in the Chinese context and argued that identification with the leader led to employee creativity. Ikhram et al. (2022) extended the LMX theory to study the relationship between leadership styles and employee job satisfaction. Qian and Jian (2020) examined the mediating role of LMX theory in the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational culture. The family values of the founders encourage them to engage in corporate social responsibility (CSR). These CSR activities significantly contribute to an company’s chance of survival (Ahmad et al., 2020). They argued that family involvement in business and their involvement in societal causes improves a company’s sustainability. Research also established the significance of the leaders’ religious beliefs in the firm performance (Ganiyu et al., 2023). Dey et al. (2022) argued that the spiritual leadership of MSME leaders positively influences the pro-environmental behavior of employees and the work climate.

In recent times, MSMEs have gained significant recognition for their employment generation and contribution to the nation’s GDP. These companies have also helped in rural industrialization, as over 55% of them are situated in rural India (Shelly et al., 2020). By employing people from the marginalized sections of society, they provide the foundation for inclusive growth. They also contribute significantly towards the achievement of the SDG goals. There are about 63,000,000 MSMEs in India. Women and members of the weaker sections manage over 60% of these companies. Hence, they become a great leveler and provides inclusivity and social and economic development for the rural population (Hattiambire and Harkal, 2022).

Previously sociologists and psychologists have researched on the value proposition of business leaders. However, there were only a few management researchers in India have discussed ethics and values of the MSME leaders. Hence, this paper studied the role of ethical leadership and ethical culture in addressing this gap. There are a few studies that explored the relationship between ethical leadership and employee job satisfaction from an Indian context (Khuntia and Suar, 2004; Bhal and Dadhich, 2011; Dhar, 2016; Aftab et al., 2023; Joseph et al., 2022; Banerjee, 2008; Kar, 2014; Chatterji and Zsolnai, 2016; Balasubramanian and Krishnan, 2012). Almost all these papers studied large organizations. Also, they did not explore the mediating role of ethical culture. These papers also do not study the moderating influence of age, gender, tenure, and age of the organization. Such a study is critical in the current scenario, as every nation prioritizes sustainable development (Roy, 2022). A few research papers also explored the role of age, gender and tenure on the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction. Researching the moderating role of the age, one come across papers that on one had argue that young millennials are more ethically oriented, while other papers argue that as one grow older there is a greater fit between organizations and people making older employees more ethically oriented. Most research papers from Indian manufacturing sector shows that older employees with longer tenure are more ethically oriented. This paper wanted to establish this relationship empirically.

This research aims to understand whether leaders in these MSME companies create an ethical culture and whether this positively impacts employee job satisfaction. The researchers asked the following research questions to guide the research. (a) Does ethical leadership affect job satisfaction directly or indirectly when mediated by ethical culture? (b) Does gender, age group, tenure with the organization, and the age of the organization moderate this relationship?

Literature review

Over the years, there has been an increasing realization that an organization’s culture and ethical leadership strongly correlate with the employee attitude at the workplace. Researchers such as Kalshoven et al. (2011) and Huhtala et al. (2013) have explored how the leader’s ethical values and practices influence employee outcomes from a western context. Mitonga-Monga (2019) explored this relationship from an African background. Vachhrajani et al. (2020) and Joseph et al. (2020) have also explored the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction from the perspective of Indian organizations. They also studied the mediating role of procedural justice perceptions. Joseph et al. (2022) studied the role of ethical organizational culture on employee job satisfaction. Belwalkar et al. (2018) studied the relationship between workplace spirituality and employee job satisfaction. The socio-cultural and religious background of the leaders have a strong influence on their leadership style. Such an outlook can also lead to organizational citizenship behavior (Azam et al., 2022). Such influences are often looked upon and emulated by their employees.

Influence of values on MSME leadership

MSME companies in India are largely family-owned. Often, these families have a patriarch who sets out the organization’s value system. Springer Nature, in 2020, came out with a special issue to understand the role of family values on business organizations and their culture. Astrachan et al. (2020) in that series studied the impact of values, spirituality, and religion on ethical behavior in family businesses. Bhatnagar et al. (2020) explored the aspect of philanthropy among Indian family firms and the influence of values. These business leaders may be rigorous regarding cost-cutting, but they treat the employees as family members. They celebrate various festivals and life events together. Sharing food is a common practice among these companies. For an Indian, good deeds (Karma) are the way to salvation. They do good things without expecting anything in return (Nishkamakarma). Most family firms do philanthropy. Hence, giving charity, treating others with respect and care, and doing good are part of Indian way of life. Kumar et al. (2022) look at this worldview guided by values, morals, and the idea of what is good as the guiding spirit of leaders. While studying Indian leaders’ ethical orientation it is in essence their value system that we are focusing on.

Ethical leadership

Most papers on ethical leadership focused on the leader’s people orientation (Bhal and Dadich, 2011), whether they treat employees fairly (Banerjee, 2008), their willingness to share power, their environmental sustainability practices, clear articulation of values and policies, and the leader’s integrity (Saha et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2005). Chen and Trevino (2023) take a different stand in their latest work and advocate for focusing on more positive aspects such as a leader’s ethical behavior, allowing people an ethical voice, encouraging positive emotions such as compassion and moral elevation to create an ethical work culture in the organizations (Bansal and Kumar, 2018). Khademian (2016) also observed in his study of the cement factory workers that supportive leaders who are able to combine task and people orientation are able to create positive ethical behavior among workers. Most studies use a LMX theory to contextualize ethical leadership.

In the paper on ethical leadership, Trevino et al. (2000) argued that the reputation of a leader as being ethical is the key to the success of an executive leader. According to them, a corporate executive leader performs two roles; that of a moral person and a moral manager. As a moral person, one must possess the traits of honesty and integrity and should walk the talk. A moral manager must create strong ethical policies, implement them, and communicate them to everyone in the organization. Therefore, ethical leadership = Moral Person + Moral Manager. Mayer et al. (2012) furthered the study of Trevino et al. (2000) and Brown et al. (2005) and identified idealized influence, interpersonal justice, and informational justice as factors distinguishing ethical leadership. In an earlier work Mayer et al. (2009) studied how ethical leadership contributes to organizational citizenship behavior and reduce workplace deviance. Goodarzi et al. (2018) also observed that when managers follow ethical path, they will be more creative and enterprising in their business.

Drawing from the various definitions of ethical leadership, Kalshoven et al. (2011) developed a theoretical model to study ethical leadership at work (ELW). The constructs they used to define ethical leadership are: (a) Fairness- where the leaders do not practice favoritism, treat everyone in a manner that is right and equal, and make choices based on principles and fairness, (b) Power sharing where the leadership takes into consideration the voice of followers while making a decision and listen to their ideas and concerns, (c) Role clarification- leadership explicitly clarify responsibilities, expectations and performance goals of every employee, (d) People orientation—leader care for, support and respect the followers, (e) Integrity-where leader walks the talk, (f) Ethical guidance—need to communicate acceptable and punishable actions, and (g) Concern for sustainability- the concern for environmental sustainability. Nastiezaie et al. (2016) and Naiyananont and Smuthranond (2017) empirically tested this model. This theoretical framework requires employees to respond to their perception of their leaders from a social exchange theory perspective. This theory presupposes that employee constantly observe the leader’s behavior and role models them. In other words, an exchange between leaders and employees creates a psychological contract that leads to higher job satisfaction. Chen et al. (2021) tested the role of gender and found in organizations where there are more male subordinates, job satisfaction is higher. To complement these constructs, Kaushal and Mishra (2017) added that the social commitment of the organizations improves employee commitment, loyalty and perseverance in organizations. This study was further reiterated by Sipahi Dongul and Artantaş (2023) where they empirically established that the social entrepreneurship behavior of the leaders improves organizational performance. Ed-Dafali et al. (2023) and Omeihe et al. (2023) then say that a transformational leadership help improve organizational efficiency and novelty.

Ethical culture

This concept premises that an organization lives by ethical principles. The research of Kaptein (2008) and several others used Corporate Virtue Ethics (CVC) model to understand the ethical culture (Gebler, 2006; Schwartz 2013; Huhtala et al., 2011). According to Kaptein (2008), one can determine the extent to which an organization’s culture motivates employees to act ethically and also prevents employees from acting unethically. Corporate ethical virtues are essential conditions for employees’ ethical behavior. His proposed virtues include role clarity, congruity, feasibility, supportability, transparency, discussability, and sanctionability. In a recent paper, Constantinescu and Katpein (2021) furthered the corporate virtue ethics and discussed virtue and virtuousness in organizations. Kancharla and Dadhich (2021) observed that ethical training has a mediating effect in reducing corruption. Desai (2020), while studying the theoretical underpinnings of corruption, argues that creating an ethical culture can significantly reduce it. Tang et al. (2018a, 2018b) argued that ethical organizational culture reduces corruption and dishonesty. Employees make a cost-benefit analysis while making ethical decisions.

Kaptein (2008) and Huhtala et al. (2013) use the virtue model to study the ethical organizational culture. Riivari and Lamsa (2019) extended the earlier studies and found that ethical culture was essential to an organization’s behavioral, strategic, and process innovativeness. We adapted this corporate ethical virtue (CEV) in this research. The constructs of this theoretical model include (a) Clarity: The expectations from an employee must be tangible, all-inclusive, and comprehensible (Fernando, 2009). (b) Congruity asks for reducing the cognitive dissonance between what management preaches and practices (Treviño et al., 2000). (Brown et al., 2005) and Schminke et al. (2005) observed that employees often role-model their leader’s unethical behavior over ethical behavior. (c) Feasibility discusses how organizations create a conducive environment for employees to act ethically (Kaptein, 2008; Trevino and Brown, 2005). (d) Supportability discusses the extent of organizational support for employees to act ethically. Román and Munuera (2005) found that displeased and demoralized employees engage in unethical activities. (e) Transparency is a general situation where employees are responsible only for those factors that they know. Organizations with high transparency and visibility are ethical (Taştan and Davoudi 2019; Hosseini et al., 2018). (f) Discussability: Kaptein (2008) says that in organizations with a low level of freedom, where criticism is not allowed, people tend to close their eyes to many unethical activities. Devine and Reaves (2016) call it “killing the messenger.” (g) Sanctionability says that the absence of sanctions for more minor infringements of ethics and law leads to a perception that anything goes (Bolino and Klotz, 2015). Due to the existence of multiple competing interests, organizations often are unable to punish unethical behavior. Aftab et al. (2023) also explored the role of age and gender as factors that impact job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction

Does Ethical leadership and ethical culture lead to increased job satisfaction? Does ethical culture function as a mediating variable to create higher job satisfaction? To answer these questions, Pettijohn et al. (2008) tested the positive relationship between employees’ perception of their leadership as ethical and their job satisfaction. An organization needs to keep its employees happy and satisfied (Al Halbusi, 2021). Valentine et al. (2006) also suggested that employees’ perception of organizational ethics and support, positively impacts their job satisfaction. It is essential for their continued existence in the organization. Çelik et al. (2015) established a positive relationship between job satisfaction and leadership ethics in the hotel industry. Demirtas and Akdogan (2015) establish the direct and indirect impact of ethical leadership, employee commitment, and turnover intentions. Employees need to be taken care of as internal customers, leading them to care for the external stakeholders (Jafari and Soltani, 2016). Tang et al. (2023) further studied the role of perceptions of pay disparities that lead to justice-seeking dishonesty among employees. Creating a perception of equal treatment can create higher job satisfaction among employees.

Job satisfaction determines the behavior as well as the turnover intention of the employee(s) in the organization. Organizations need to retain a skilled and motivated workforce for the continuing success of the organization’s vision, objectives, and goals. Hence, managing employee attitudes takes center stage (Judge et al., 2017). Job satisfaction involves employees’ affect or emotions; it influences an organization’s well-being concerning job productivity, employee turnover, absenteeism, and life satisfaction (Roodt et al., 2002). Over the years, one has observed increasing research on business ethics and its relation to employee morale (Huhtala et al., 2013). Some emerging topics within this research are societal expectations, fair competition, legal protection and rights, and social responsibilities. Ethical business practices positively impact various organizational stakeholders, such as customers, employees, competitors, and the general public. Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (2016) found that when employees perceive their leaders as having highly ethical behavior, they tend to have higher levels of commitment and exhibit organizational citizenship behavior. A study by Li (2024) empirically established that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior.

Role of gender, age of the organizations and tenure of employee

Ethical leadership do elicit ethical employee behavior. However, does gender of the leader have any impact on the ethical behavior? Several studies have examined this relationship between the gender of the leader and the organizations ethical practice. Eliwa et al. (2023) argued that a more gender diversified board is important to ensure corporate social responsibility. Another study by Prochazkova and Micak (2023) noticed that in organizations that has woman CEO has higher ethical behavior and has more inclinations towards corporate social responsibility. In the same line Glover et al., 2002 had also argued that women are more ethical compared to male counterparts. Women generally exhibited significantly higher levels of ethical judgment than Men. In recent times some research argue that young people exhibit more ethical behavior than older generations. However most empirical research supports the fact that older generations exhibit more ethical behavior both as leaders and employees (Lasthuizen and Badar, 2023). While studying the impact of tenure on the ethical behavior of employees, studies show that those who have higher organization- person fit have higher ethical standards. Those who have longer tenure tend to have higher fit. Al Halbusi et al. (2021) proved this hypothesis through their empirical study. Schwepker and Dimitriou (2021) also said that employees with higher tenure are less stressed at work compared to those with lesser experience and hence are less prone to unethical behavior. Based on the gaps identified in the literature we propose to test the following Hypotheses.

H1. Ethical leadership has a positive impact on Employee Job Satisfaction.

H2. Ethical leadership has a positive impact on Ethical Organizational Culture.

H3. Ethical Organizational Culture has a positive impact on employee Job Satisfaction.

H4. Ethical leadership positively impacts Job Satisfaction when mediated through Ethical Culture.

H5. Gender, age, and tenure of the organization has a moderating impact on the Ethical leadership, Ethical culture, and Job satisfaction.

Research methodology

Measurement scale

Researchers used existing models to construct the theoretical model for this paper. We adapted the ethical leadership constructs from the works of Kalshoven et al. (2011). They formulated and tested the Ethical Leadership at Work framework. We adapted the Ethical Culture construct from the work of Kaptein’s (2008) study. The items of Job satisfaction are from Çelik (2015) study. We used the 5-point Likert scale to measure the items.

Data collection

We collected data from MSME companies from the manufacturing and service sectors through a survey. The manufacturing companies include auto parts, plastic, heating equipment, and firearm and food processor companies. The service companies include logistics, supply chain, and information technology companies (Jibril et al., 2024). We sent out invitations to 350 employees of selected small-size manufacturing and IT companies and received 225 responses. However, we considered only 210 responses for the final analysis, after removing 15 incomplete records. We employed a convenience sampling method because most employers hesitate to allow their employees to answer the survey on ethical leadership and ethical culture. So, we selected companies from where there is a possibility of getting a response. Table 1 displays the demographic details of the respondents. There were 152 males and 58 females who responded to the questionnaire. The data also shows that the age of all the employees lies between 20 and 50 years, out of which the maximum employees are young (between 20 and 30 years), followed by senior employees (between age 31 and 50 years). Forty percent of employees have less than or equal to 2 years of tenure with the organization, 39 percent have tenure between 3 to 5 years, and 21 percent have more than 6 years with the organization.

Results and discussion

Results

This section presents results of our data analysis. We employed systematic multistage approach to present the results, beginning with the assessment of the measurement model to establish reliability and validity of model. Later we assessed the model fit using established model fit indices. Upon validating the measurement model, we proceeded with path analysis and hypothesis testing to evaluate direct and indirect relationships proposed in the study. Furthermore, the moderation analysis was also conducted to assess effect of gender, employee age, organizational age, and employee tenure on the relationships proposed in the study. Subsequent section present results of these analysis in detail.

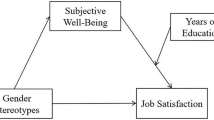

Assessment of measurement model

We analyzed the data using covariance-based SEM. The measurement model is shown in the Fig. 1. To ensure reliability and validity of the constructs the measurement model was first assessed using factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), maximum shared variance (MSV), and Maximum reliability Value (MAxR(H)) (Hair et al., 2017, Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Hair et al. (2017) suggested that factor loading and AVE should be greater than 0.7, and CR should be greater than 0.5. We used the Fornell–Larcker criterion to evaluate the discriminant validity. Table 2 and Table 3 shows that the model is reliable as it fulfills all criteria of model reliability. The data has discriminant validity because Inter-construct correlations are less than the square root of AVE. The MAxR(H) value is also greater than CR (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Model fit and hypothesis testing

Following the validation of the measurement model, model fit was evaluated to assess how well the proposed structural model fits the data. We assessed the model fit of the data using the indicators shown in Table 4. We observed that the model fits the data well as all values of Chi-Square, CFI, IFI, RMSEA, and RMR fulfill the criteria given in the references. Therefore, path analysis can be carried out to test the proposed hypothesis.

Path analysis and hypothesis testing

This section presents the results of the path analysis which examines the relationships proposed in the study. Figure 2 shows the path diagram of the model proposed in the study. Table 5 shows model fit indices of path analysis and Table 6 shows the results of the path analysis.

We have tested the following hypothesis.

H1. Ethical leadership has a positive impact on Employee Job Satisfaction.

The results indicate that the direct effect of EL on JS is 0.30 with “p” value less than 0.05. Therefore, we can conclude that ethical leadership positively influences employee job satisfaction.

H2. Ethical leadership has a positive impact on the ethical culture of the organization.

The results shows that the regression weight between EL and EC is 0.80 with “p” value less than 0.05. Thus, we can conclude that there is the high positive impact of ethical leadership on the ethical culture of the organization.

H3. Ethical culture of the organization has a positive impact on employee Job Satisfaction.

The path coefficient between EC and JS is 0.50 with p value less than 0.05. Therefore, we can conclude that there is a moderate positive impact of ethical culture on the job satisfaction of the employee.

H4. Ethical culture mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and employee job satisfaction.

The results reveals that the indirect effect between EL and JS through EC is 0.40 with “p” value less than 0.05. Further, direct impact of EL on JS is also significant and positive. Therefore, we can infer that ethical culture partially mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction.

H5. Gender, age, and organizational tenure moderate the relationship between ethical leadership, ethical culture, and job satisfaction.

The results of the moderation analysis were given statistical evidence. No significant moderation by gender was found in any of the relationships. All of the paths (EL → EC, EL → JS, EC → JS) were significant for males as well as for females (p > 0.58), which seems to suggest against gender-specific perception depicted in the Table 7.

Moderation of age was found to be quite apparent. Ethical leadership was not significantly associated with job satisfaction among employees 20–30 years (β = 0.13, p = 0.36), ethical culture did (β = 0.69, p = 0.001). By contrast, ethical leadership significantly influenced job satisfaction among staff aged 31–50 years, and ethical culture had direct positive effects on the young people depicted in the Table 9.

Organizational tenure also acted as a moderator in the relationships. Moral leadership affected job satisfaction only for high-tenure workers (β = 0.48, p = 0.028). Ethical culture was a strong predictor of job satisfaction for low (1–2 years) and medium-tenure (3–5 years) employees (β = 0.63 and 0.59 respectively, p < 0.01) but not for high-tenure employees depicted in the Table 11.

Common method variance

Given that the data were collected using questionnaire method the possibility of the common method bias was assessed. We adopted Harman’s single factor test to check common method bias in the dataset. If there is a common method bias in the dataset, the majority of the variance in the dataset is explained by a single factor (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Harman’s single-factor test checks if a single factor explains the majority of the variance. When we extracted only one-factor using exploratory factor analysis, we found that the total variance extracted by a single factor was less than 50 percent. Therefore, there is no concern about common method bias in the dataset.

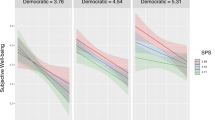

Moderation effect of gender

Moderation analysis is carried out to explore whether relationship between Ethical Leadership, Ethical Culture and Job Satisfaction in the proposed model differs by Gender. Figure 3a, b shows path analysis results for Men and Women and Table 7 summarizes the results. All the paths for both Men and Women are significant. We also observed that there is no significant difference in the path coefficients across the genders. Table 8 presents the model fit indices for moderation effect of gender to ensure that they are in the acceptable threshold and fits the data well across the subgroups (Men and Women).

Moderation effect of age of the employee

Moderation analysis was further carried out to check moderation effect of age of the employee on the relationship between EL, EC, and JS of the proposed model. Figure 4a, b shows the path analysis results for the employees’ different age groups. Table 9 summarizes the results and Table 10 presents the model fit indices for the moderation effect of the age of the employees. It is seen that model fit indices values are within acceptable threshold indicating that model fits the data well across the subgroups. We observed that the impact of EL on EC is significant for both age groups. Interestingly, we also observed that while the impact of EL on JS is significant only for the senior age group, the EC to JS is significant only for the young age group.

Moderation effect of age of organization

This part of the analysis investigates whether age of the organization moderates the hypothesized relationship in the proposed model. Figure 5a, b, c show path analysis results across different age groups of organizations. Table 11 summarizes the path analysis results for the moderation effect of age of the organization. Table 12 shows the model fit indices for the moderation effect of age of the organization. The results show that the impact of EL on EC is significant for all age groups of organization. The impact of EL on EC is significantly different for the high-age group organizations than low and medium-age group organizations. The impact of EL on JS is significant only for organizations between the ages of 1 and 10 Years. The impact of EC on JS is significant only for organizations aged between 11 and 20 Years and above 20 Years, but we did not observe any significant difference between them.

a Path analysis results for organization age between 1 and 10. Organization age between 1 and 10 years (Low). b Path analysis results for organization age between 11 and 20. Organization age between 11 and 20 years (Medium). c Path analysis results for organization age between 20 and above. Organization age above 20 years (High).

Moderation effect of employee tenure with organization

Finally, moderation role of the employee tenure was examined to understand whether length of service of employee affects the relationship between EL, EC, and JS of the proposed model. Figure 6a, b, c show path analysis results for the tenure of the employee with the organization. Table 13 summarizes the results of the path analysis. Table 14 shows the model fit indices for the moderation effect of employee tenure within the organization. The results shows that the impact of EL on EC is significant for all groups. We observe no significant difference between the medium and high tenure groups, but a significant difference exists between the low and medium tenure groups and the low and high tenure groups. Interestingly, the impact of EL on JS is significant only for the high-tenure group. The impact of EC on JS is significant only for low and medium-tenure groups.

a Path analysis results for employee tenure with the organization for 1–2 years. Employee tenure with the organization between 1 and 2 Years (Low tenure group). b Path analysis results for employee tenure with organization for 3–5 years. Employee tenure with the organization between 3 and 5 years (medium tenure group). c Path analysis results for employee tenure with the organization above 5 years. Employee tenure with the organization above 5 Years (high tenure group).

Discussion

This research investigated five hypotheses on examining ethical leadership (EL), ethical culture (EC) and its effect on job satisfaction (JS) in Indian MSMEs. This result corroborates H1, demonstrating that EL exerts a strong direct impact on JS. This is consistent with existing literature which posits that leaders who are honest, just and have concern exert a positive influence on subordinates’ job attitudes. H2 and H3 are also supported, with EL having a very strong effect on EC and EC having a medium effect on JS. This finding confirms that leaders shape ethical norms that have downstream effects on employee job satisfaction. H4 is supported as EC partly mediates the EL-JS link, demonstrating that ethical culture represents a central mechanism through which leadership influences well-being. H5, which were about moderate effects of gender, age, tenure and organizational age showed debatable results. Gender did not moderate, but age and tenure did, such that young employees reacted more to EC and old long-tenured employees to EL. The relationships under examination were moderated by organizational age indicating that age matters in ethical perception formation.

We used a combination of models and constructs developed in a Western context, tested them in India, and found a good fit. This result is an exciting outcome as this is the first time someone tested this model in India. The previous study by Khuntia and Suar (2004) only tested the ethical leadership constructs in an Indian context. Our research tested these constructs and found positive correlations between ethical leadership and employee job satisfaction and that ethical culture mediates this relationship. This brings to the fore the important role an ethical organizational culture plays in creating higher employee job satisfaction. This research offers several pointers for researchers and managers. Employee’s perception of their leader is an important factor. A leader has to practice what he preaches.

Theoretical implication

The research used both social exchange theory and leader member exchange theory to explain the relationship between the constructs. Employees’ cognitive evaluation of their leaders plays a significant role in constructing the LMX theory. There is a continuous exchange between leaders and their subordinates. In the MSME companies, leaders take a parental role and develop a deep relationship with their employees (Panya, 2024). However, many have observed that there is also an exploitative relationship between leaders and their subordinates in MSMEs (Maheshwari et al., 2020). Hence, the researchers assumed that job satisfaction depends on how employees perceive their leader as ethical and who walks the talk (Joseph et al., 2020). Some leaders make an effort to create a culture of ethics in their organizations, and employees feel that this is important for their job satisfaction. This research has tested and shown that employees’ perception of their leaders as being ethical, positively impacts their job satisfaction. The research also showed a partial mediation of ethical culture to create higher job satisfaction.

The paper further tested the moderating variables of age, gender, tenure, and the age of the organization. Each of these has a significant impact on employee job satisfaction. The study showed that both men and women feel that EL leads to JS, and when EC mediates, it leads to higher JS. However, this paper found that while the relation between EL and JS is higher among older employees, younger employees feel that EC significantly impacts JS. This finding is a significant contribution of this research paper.

Similarly, for tenure, the results show that the impact of EL on EC is significant for all groups. There is no significant difference between the medium and high-tenure groups. However, a significant difference exists between the low and medium-tenure groups and the low and high-tenure groups. Interestingly, the impact of EL on JS is significant only for the high-tenure group. The impact of EC to JS is significant only for low and medium-tenure groups. While testing the impact of age of the organization we found that the impact of EL on EC is significant for all age groups of organization. The impact of EL on EC is significantly different for older organizations than for low- and medium-age organizations. The impact of EL on JS is significant only for organizations between the ages of 1 and 10. The impact of EC to JS is significant only for organization older than 10 years.

Managerial implications

The paper brings several managerial implications through the moderating variable analysis. Primarily, the research found a positive correlation between all three constructs, and hence, we propose that MSME leaders have to walk the talk of ethics and integrity. They have to guide employees in the right direction actively. They must show a higher level of people-orientation and concern for long-term orientation. In order to create an ethical culture, the leaders need to articulate policies clearly. There should be a congruity between the policy and the actions of the top leadership. Leaders must provide the space for employee voice. Various forums to discuss ethics are also crucial to creating an ethical culture within the organization. The paper has proved that if these factors are present, it will lead to higher employee job satisfaction.

The paper has a few unexpected outcomes that the researchers had yet to anticipate. The first one is that young employees do not look up to the leader as a role model, but having an ethical culture in the organization is important for them. This finding is crucial when dealing with millennial and Gen Z employees. They look for a good ethical culture within the organizations than emulating the leader.

The second unanticipated outcome is related to the tenure of the employees. The research observed that employees with more than 5 years of experience in the same organization look up to the leaders as role models. For employees with work experience of less than 2 years, the ethical culture is an important predictor of job satisfaction.

The third significant contribution of the paper is that in organizations that are new (less than 10 years), ethical leadership is a significant predictor of job satisfaction. For older organizations, ethical culture has a significant impact on employee job satisfaction. In new organizations, the leaders should become role models. Employees emulate the leader and hence they have to actively walk the talk. Older employees value an ethical culture. Organizations can manage this by having clearly articulated policies, avenues to express dissents, and sanctions for violations.

Limitations

One of the major limitations of this paper is that we could not collect a larger sample. Most MSME leaders are not willing to allow the employees to fill in such a questionnaire. Another reason for the low number is that in most of these MSMEs, only a few employees understand English to fill in the questionnaire. After approaching many MSMEs we still could not get a larger sample. Lack of external funding also limited the researcher’s ability to reach out to a larger population. The research also excluded micro-organizations as they needed more English-speaking workforce. We also avoided MNC companies as they have a different value system.

The research only addressed the MSME companies and their employees. We did not study the larger organizations in India. Further studies are needed among larger manufacturing and IT services companies to see if we get the same results. The unexpected results of the moderating variables need to be tested among larger organizations. The indicators for smaller organizations say that organizations need to create a culture of ethics. This will have far-reaching impacts on leadership development in these organizations. This research is a definite indication that the value system of the new workforce is clearly changing.

Conclusion

The significance of MSMEs to national development has gained prominence in the wake of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). MSMEs are key to the attainment of SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) as well as SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) as they play a vital role in employment, entrepreneurship and local economic development. In India, MSMEs contribute to around 33% of the GDP and a major part of the workforce; therefore, promoting ethical and inclusive organizational cultures is not only an option but is the need of the hour. This study has shown that ethical leadership and a strong ethical culture in MSMEs contribute to the enhancement of employee job satisfaction. But not everyone is equally affected. It’s evident that younger workers value an ethical workplace more than loyalty to a leader, indicating a seismic shift in what today’s workforce thinks and wants. Alternatively, some longer-serving workers might still consider the integrity of leadership to be just as important as their younger counterparts. Managers of MSMEs should therefore have double standards: lead with strong ethical morals, and stabilize transparent and inclusive organizational behaviors. Crucially, this research is not claiming that ethical leadership or culture on their own will lead to positive organizational results. Instead, they should be part of a wider approach that involves with policy certainty, the mechanisms to give employees a voice, and a long-term commitment to ethical governance. By enabling MSMEs to act in line with SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) and integrate integrity and fairness into their operations they can shape resilient, people-centric workplaces which will promote economic and social sustainability.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are included in the article. Additional data that support the findings of this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aftab J, Sarwar H, Kiran A, Qureshi MI, Ishaq MI, Ambreen S, Kayani AJ (2023) Ethical leadership, workplace spirituality, and job satisfaction: moderating role of self-efficacy. Int J Emerg Mark 18(12):5880–5899. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2021-1121

Ahmad S, Siddiqui KA, AboAlsamh HM (2020) Family SMEs’ survival: the role of owner family and corporate social responsibility. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 27(2):281–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-12-2019-0406

Al Halbusi H, Tang TLP, Williams KA, Ramayah T (2022) Do ethical leaders enhance employee ethical behaviors? Organizational justice and ethical climate as dual mediators and leader moral attentiveness as a moderator—evidence from Iraq’s emerging market. Asian J Bus Ethics 11(1):105–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00143-4

Al Halbusi H, Williams KA, Ramayah T, Aldieri L, Vinci CP (2021) Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Pers Rev 50(1):159–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2019-0522

Arruda MCC (2011) Latin America: ethics and corporate social responsibility in Latin American small and medium-sized enterprises: challenging development (pp 55–83). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9331-8_5

Astrachan JH, Binz Astrachan C, Campopiano G, Baù M (2020) Values, spirituality and religion: family business and the roots of sustainable ethical behavior. J Bus Ethics 163(4):637–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04392-5

Azam T, Malik SY, Ren D, Yuan W, Mughal YH, Ullah I, Fiaz M, Riaz S (2022) The moderating role of organizational citizenship behavior toward environment on relationship between green supply chain management practices and sustainable performance. Front Psychol 13:876516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.876516

Babič Š (2014) Ethical leadership and leader member exchange (LMX) theory. CRIS—Bulletin of the Centre for Research and Interdisciplinary Study, 2014 (1): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.2478/cris-2014-0004

Balasubramanian P, Krishnan VR (2012) Impact of gender and transformational leadership on ethical behaviors. Gt Lakes Her 6(1):48–58

Banerjee B (2008) Corporate social responsibility: the good, the bad and the ugly. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920507084623

Bansal J, Kumar D (2018) Is ethical leadership beneficial? Asian J Manag 9(1):539–542. https://doi.org/10.5958/2321-5763.2018.00084.7

Başar U, Sığrı Ü, Nejat Basım H (2018) Ethics lead the way despite organizational politics. Asian J Bus Ethics 7(1):81–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-017-0084-8

Bello F, Isiaka SB, Kadiri IB (2018) Business ethics and employees satisfaction in selected micro and small enterprises in Ilorin Metropolis, Kwara State, Nigeria. KIU J Soc Sci 4(3):177, https://ijhumas.com/ojs/index.php/niujoss/article/view/375

Belwalkar S, Vohra V, Pandey A (2018) The relationship between workplace spirituality, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors—an empirical study. Soc Responsib J 14(2):410–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-05-2016-0096

Bhal KT, Dadhich A (2011) Impact of ethical leadership and leader-member exchange on whistle blowing: the moderating impact of the moral intensity of the issue. J Bus Ethics 103(3):485–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0876-z

Bhatnagar N, Sharma P, Ramachandran K (2020) Spirituality and corporate philanthropy in Indian family firms: an exploratory study. J Bus Ethics 163(4):715–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04394-3

Bolino MC, Klotz AC (2015) The paradox of the unethical organizational citizen: the link between organizational citizenship behavior and unethical behavior at work. Curr Opin Psychol 6:45–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.026

Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA (2005) Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 97(2):117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Çelik S, Dedeoğlu BB, Inanir A (2015) Relationship between ethical leadership, organizational commitment and job satisfaction at hotel organizations. Edge Acad Rev 15(1):53–64

Chatterji M, Zsolnai L (eds) (2016) Ethical leadership: Indian and European spiritual approaches. Springer

Chen A, Treviño LK (2023) The consequences of ethical voice inside the organization: an integrative review. J Appl Psychol 108(8):1316–1335. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001075

Chen C, Ding X, Li J (2021) Transformational leadership and employee job satisfaction: the mediating role of employee relations climate and the moderating role of subordinate gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(1):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010233

Constantinescu M, Kaptein M (2021) Virtue and virtuousness in organizations: guidelines for ascribing individual and organizational moral responsibility. Bus Ethics, Environ Responsib 30(4):801–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12373

Demirtas O, Akdogan AA (2015) The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J Bus Ethics 130(1):59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2196-6

Desai N (2020) Understanding the theoretical underpinnings of corporate fraud. Vikalpa: J Decis Mak 45(1):25–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090920917789

Devine T, Reaves A (2016) Whistleblowing and research integrity: making a difference through scientific freedom. Handbook of academic integrity, 957. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_31

Dey M, Bhattacharjee S, Mahmood M, Uddin MA, Biswas SR (2022) Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J Clean Prod 337:130527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130527

Dhar RL (2016) Ethical leadership and its impact on service innovative behavior: the role of LMX and job autonomy. Tour Manag 57:139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.011

Ed-Dafali S, Mohiuddin M, Al Azad M S, Salamzadeh A (2023) Entrepreneurial leadership and designing industry 4.0 business models: towards an innovative and sustainable future for India. Indian SMEs and Start-Ups: growth through Innovation and Leadership, 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1142/13239

Eliwa Y, Aboud A, Saleh A (2023) Board gender diversity and ESG decoupling: does religiosity matter? Bus Strategy Environ 32(7):4046–4067. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3353

Fernando AC (2009) Business ethics: an Indian perspective. Pearson Education

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382–388

Ganiyu SI, Abdullahi N, Karwai SA (2023) Effect of entrepreneurial competencies and religiousity on the performance of MSMEs in Adamawa State. Afr Sch J Bus Dev Manag Res (JBDMR-7) 29(7):1–18

Gaskin DJ, Richard P (2012) The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain 13(8):715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009

Gebler D (2006) Creating an ethical culture. Strateg Financ 87(11):28

Glover SH, Bumpus MA, Sharp GF, Munchus GA (2002) Gender differences in ethical decision making. Women Manag Rev 17(5):217–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420210433175

Goodarzi SM, Salamzadeh Y, Salamzadeh A (2018) The impact of business ethics on entrepreneurial attitude of manager. Competitiveness in emerging markets: market dynamics in the age of disruptive technologies, pp 503–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71722-7_25

Gu Q, Tang TLP, Jiang W (2015) Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader–member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. J Bus Ethics 126(3):513–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1967-9

Hair JFH Jr, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Sarstedt M (2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivar Data Anal 1(2):107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

Hattiambire DT, Harkal P (2022) Challenges and future prospects for the Indian MSME sector: a literature review. J Manag Entrep 16(1):2022

Hosseini M, Shahri A, Phalp K, Ali R (2018) Four reference models for transparency requirements in information systems. Requir Eng 23(2):251–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00766-017-0265-y

Huhtala M, Feldt T, Lämsä AM, Mauno S, Kinnunen U (2011) Does the ethical culture of organizations promote managers’ occupational well-being? Investigating indirect links via ethical strain. J Bus Ethics 101(2):231–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0719-3

Huhtala M, Kangas M, Lämsä AM, Feldt T (2013) Ethical managers in ethical organisations? The leadership‐culture connection among Finnish managers. Leadersh Organ Dev J 34(3):250–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731311326684

Ikhram WMAD, Fathoni RAR (2022) The effect of transformational leadership style on performance and satisfaction of MSME employees mediated through leader member exchange. Manaj Bisnis 12(1):94–101. https://doi.org/10.22219/mb.v12i01.21746

Iyer CH, Ravindran G (2013) A study on ethical aspects of accounting profession-an exploratory research in MSMES. CLEAR Int J Res Commer Manag 4(3):1−6

Jafari Navimipour NJ, Soltani Z (2016) The impact of cost, technology acceptance, and employees’ satisfaction on the effectiveness of the electronic customer relationship management systems. Comput Hum Behav 55:1052–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.036

Jibril AB, Amoah J, Panigrahi RR and Gochhait S (2024) Digital transformation in emerging markets: the role of technology adoption and innovative marketing strategies among SMEs in the post – pandemic era, International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi-org.elibrary.siu.edu.in/10.1108/IJOA-05-2024-4509

Joseph S, Jadhav A, Nagendra A (2020) An empirical study of the impact of ethical leadership on employee job satisfaction (study of MSMEs in India). Indian J Ecol 47(spl):1–7

Joseph S, Jadhav A, Vispute B (2022) Role of ethical organizational culture on employee job satisfaction: an empirical study. Int J Bus Gov Ethics 16(3):337–354. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBGE.2022.123672

Joseph S, Nagendra A, Kulkarni AV (2020) Giving voice to values: a study of the leadership role in creating a value culture in the MSME sector in India. Int J Soc Sustain Econ Soc Cult Context 17(1):27–52. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1115/CGP/v17i01/27-52

Judge TA, Weiss HM, Kammeyer-Mueller JD, Hulin CL (2017) Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: a century of continuity and of change. J Appl Psychol 102(3):356–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000181

Kalshoven K, Den Hartog DN, De Hoogh AHB (2011) Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadersh Q 22(1):51–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007

Kancharla R, Dadhich A (2021) Perceived ethics training and workplace behavior: the mediating role of perceived ethical culture. Eur J Train Dev 45(1):53–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-03-2020-0045

Kaptein M (2008) Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: the corporate ethical virtues model. J Organ Behav 29(7):923–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.520

Kar S (2014) Ethical leadership: best practice for success. IOSR J Bus Manag 1(14):112–116

Kaushal N, Mishra S (2017) Comprehensive interpretation of leadership from the narratives in literature. J Entrep Bus Econ 5(2):64–86. http://scientificia.com/index.php/JEBE/article/view/71

Khademian N (2016) The effect of leadership style on professional ethical behavior: an empirical study in cement factory. J Entrep Bus Econ 4(1):128–147. http://scientificia.com/index.php/JEBE/article/view/40

Khuntia R, Suar D (2004) A scale to assess ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. J Bus Ethics 49(1):13–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000013853.80287.da

Kim D, Vandenberghe C (2021) Ethical leadership and organizational commitment: the dual perspective of social exchange and empowerment. Leadersh Organ Dev J 42(6):976–987. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2020-0479

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd edn. The Guilford Press

Kumar S, Sahoo S, Lim WM, Dana LP (2022) Religion as a social shaping force in entrepreneurship and business: insights from a technology-empowered systematic literature review. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 175:121393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121393

Lasthuizen K, Badar K (2023) Ethical reasoning at work: a cross-country comparison of gender and age differences. Adm Sci 13(5):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13050136

Li Q (2024) Ethical leadership, internal job satisfaction and OCB: the moderating role of leader empathy in emerging industries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03367-w

Lin WL, Yip N, Ho JA, Sambasivan M (2020) The adoption of technological innovations in a B2B context and its impact on firm performance: an ethical leadership perspective. Ind Mark Manag 89:61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.12.009

Maheshwari M, Samal A, Bhamoriya V (2020) Role of employee relations and HRM in driving commitment to sustainability in MSME firms. Int J Prod Perform Manag 69(8):1743–1764. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-12-2019-0599

Mayer DM, Aquino K, Greenbaum RL, Kuenzi M (2012) Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad Manag J 55(1):151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276

Mayer DM, Kuenzi M, Greenbaum R, Bardes M, Salvador RB (2009) How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 108(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002

Mitonga-Monga J, Cilliers F (2016) Perceived ethical leadership in relation to employees’ organisational commitment in an organisation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Afr J Bus Ethics 10(1). https://doi.org/10.15249/10-1-122

Mitonga-Monga J, Flotman AP, Moerane EM (2019) Influencing ethical leadership and job satisfaction through work ethics culture. J Contemp Manag 16(2):673–694. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-19f0aeacdd 10.35683/jcm19048.52

Naiyananont P, Smuthranond T (2017) Relationships between ethical climate, political behavior, ethical leadership, and job satisfaction of operational officers in a wholesale company, Bangkok Metropolitan region. Kasetsart J Soc Sci 38(3):345–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2016.07.005

Nastiezaie N, Bameri M, Salajage S (2016) Predicting employees’ trust and organizational commitment based on the ethical leadership style. Int Bus Manag 10(16):3479–3485

Omeihe I, Harrison C, Simba A, Omeihe K (2023) The role of the entrepreneurial leader: a study of Nigerian SMEs. Int J Entrep Small Bus 49(2):187–215. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2023.132439

Pandey A, Tiwari D, Singh R (2023) Environmental social and governance reporting in Indian: an overview. EPRA Int J Multidiscip Res 9(8):47–51

Panya F (2024) Paternalism as a positive way of HRM in MSMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Empl Relat 46(1):147–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2022-0395

Pettijohn C, Pettijohn L, Taylor AJ (2008) Salesperson perceptions of ethical behaviors: their influence on job satisfaction and turnover intentions. J Bus Ethics 78(4):547–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9367-7

Prochazkova K, Micak P (2023) CEO gender and its effect on corporate social responsibility and perception of business ethics. Econ Manag Spectr 17(1):29–38

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879

Qian Y, Jian G (2020) Ethical leadership and organizational cynicism: the mediating role of leader-member exchange and organizational identification. Corp Commun: Int J 25(2):207–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-06-2019-0069

Riivari E, Lämsä AM (2019) Organizational ethical virtues of innovativeness. J Bus Ethics 155(1):223–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3486-6

Román S, Luis Munuera J (2005) Determinants and consequences of ethical behavior: an empirical study of salespeople. Eur J Mark 39(5/6):473–495. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560510590674

Roodt G, Rieger HS, Sempane ME (2002) Job satisfaction in relation to organizational culture. SA J Ind Psychol 28(2):23–30. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC88907

Roseni E (2015) Curricular objectives of measurement and evaluation in the reformed process of digital school in Albania. In Edulearn15 proceedings. IATED, pp 5737–5743

Roy ES (2022) An assess on the performance of MSMEs in India. Shanlax Int J Manag 10(1):21–24. https://doi.org/10.34293/management.v10i1.4942

Saha R, Shashi Cerchione R, Singh R, Dahiya R (2020) Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: a systematic review. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(2):409–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1824

Schminke M, Ambrose ML, Neubaum DO (2005) The effect of leader moral development on ethical climate and employee attitudes. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 97(2):135–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.006

Schwartz MS (2013) Developing and sustaining an ethical corporate culture: The core elements. Bus Horiz 56(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2012.09.002

Schwepker JrCH, Dimitriou CK (2021) Using ethical leadership to reduce job stress and improve performance quality in the hospitality industry. Int J Hosp Manag 94:102860

Shelly R, Sharma T, Bawa SS (2020) Role of micro, small and medium enterprises in Indian economy. Int J Econ Financl Issues 10(5):84–91. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.10459

Singh D, Khamba JS, Nanda T (2018) Problems and prospects of Indian MSMEs: a literature review. Int J Bus Excell 15(2):129–188. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2018.091923

Sipahi Dongul E, Artantaş E (2023) Exploring the link between social work, entrepreneurial leadership, social embeddedness, social entrepreneurship and firm performance: a case of SMES owned by Chinese ethnic community in Turkey. J Enterp Communities People Places Glob Econ 17(3):684–707

Sorenson RL (2000) The contribution of leadership style and practices to family and business success. Fam Bus Rev 13(3):183–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00183.x

Tang TLP, Li Z, Özbek MF, Lim VKG, Teo TSH, Ansari MA, Sutarso T, Garber I, Chiu RKK, Charles-Pauvers B, Urbain C, Luna-Arocas R, Chen J, Tang N, Tang TLN, Arias-Galicia F, De La Torre CG, Vlerick P, Akande A, Pereira FJC (2023) Behavioral economics and monetary wisdom: a cross‐level analysis of monetary aspiration, pay (dis) satisfaction, risk perception, and corruption in 32 nations. Bus Ethics, Environ Responsib 32(3):925–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12505

Tang TLP, Sutarso T, Ansari MA, Lim VKG, Teo TSH, Arias-Galicia F, Garber IE, Chiu RKK, Charles-Pauvers B, Luna-Arocas R, Vlerick P, Akande A, Allen MW, Al-Zubaidi AS, Borg MG, Canova L, Cheng BS, Correia R, Du LZ, Tang NY (2018a) Monetary intelligence and behavioral economics across 32 cultures: good apples enjoy a good quality of life in good barrels. J Bus Ethics 148(4):893–917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2980-y

Tang TLP, Sutarso T, Ansari MA, Lim VKG, Teo TSH, Arias-Galicia F, Garber IE, Chiu RKK, Charles-Pauvers B, Luna-Arocas R, Vlerick P, Akande A, Allen MW, Al-Zubaidi AS, Borg MG, Cheng BS, Correia R, Du LZ, Garcia de la Torre C, Adewuyi MF (2018b) Monetary intelligence and behavioral economics: the Enron Effect—love of money, corporate ethical values, Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), and dishonesty across 31 geopolitical entities. J Bus Ethics 148(4):919–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2942-4

Taştan SB, Davoudi SMM (2019) The relationship between socially responsible leadership and organizational ethical climate: in search for the role of leader’s relational transparency. Int J Bus Gov Ethics 13(3):275–299. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBGE.2019.099368

Tin TT et al. (2024) Exploring the factors affecting mental health and digital cultural dependency among university students. Pak J Life Soc Sci 22(2):16062–16080. https://doi.org/10.57239/PJLSS-2024-22.2.001163

Trevino LK, Brown ME (2005) The role of leaders in influencing unethical behavior in the workplace. Manag Organ Deviance 5:69–87

Treviño LK, Hartman LP, Brown M (2000) Moral person and moral manager: how executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. Calif Manag Rev 42(4):128–142. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166057

Vachhrajan M, Singh S, Rai H (2020) The mediating role of justice perceptions in the linkage between ethical leadership and employee outcomes: a study of Indian professionals. Int J Indian Cult Bus Manag 20(4):488–509. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJICBM.2020.108924

Valentine S, Greller MM, Richtermeyer SB (2006) Employee job response as a function of ethical context and perceived organization support. J Bus Res 59(5):582–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.06.004

Villaluz VC, Hechanova MRM (2019) Ownership and leadership in building an innovation culture. Leadersh Organ Dev J 40(2):138–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-05-2018-0184

Yadav S (2017) Employment, production and working conditions in MSMEs after economic reforms: India and Gujarat. J Reg Dev Plan 6(2):53

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shaji Joseph: Methodology, Performed experiments, Software, Visualization. Anil Jadhav: Conceptualization, Writing—Original draft preparation, Validation. Saikat Gochhait: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Ayodeji Olalekan Salau: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology and Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Until 29 April 2025, ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) at Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India, was not mandatory for studies based entirely on written sources. Ethical approval for this research was granted by the Academic Integrity Committee (AIC) of the university (Ref. No.: SCIT/2023/01/01, dated 10 January 2023) for a duration of 2 years. On 30 April 2025, the university regulations changed, and IEC approval became mandatory for such studies. The present research was completed prior to this regulatory change. The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants, who participated voluntarily and retained the right to withdraw at any time. All data were anonymized and processed in accordance with university and applicable data protection regulations.

Informed consent

In accordance with national regulations and institutional ethical standards, the first author obtained written informed consent from 210 participants representing micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) affiliated with the SME Chamber of India. The process was conducted between October 5th and December 5th, 2022. Participants, and where applicable, their companies’ representatives, received clear information on the study’s purpose, procedures, voluntary nature, and their right to withdraw. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured, with no personally identifiable information collected. Data were collected through anonymous paper-based questionnaires and used solely for academic research, with no commercial application. The study involved MSME companies from both manufacturing (auto parts, plastics, heating equipment, food processing) and service sectors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joseph, S., Jadhav, A., Gochhait, S. et al. Exploring the influence of ethical leadership and culture on employee job satisfaction: the moderating effects of age, gender, tenure, and organizational age. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06167-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06167-y