Abstract

Public research institutions are critical actors in driving innovation through publicly funded research. They need to build and deploy their core assets of human capital for knowledge production, yet they often operate with constrained autonomy. This study examines how financial management autonomy shapes talent strategies and, in turn, research productivity in China’s leading research institutions. Exploiting a quasi-natural experiment in which 30% of top institutions were granted autonomy over personnel budgets, we compare divergent pathways linking autonomy to performance. The analysis reveals that institutions with team-based knowledge production models performed better by incentivizing incumbent researchers, while those with individual-based models benefited more from hiring externally. These results highlight the overall value of autonomy in public research institutions, and the contingent nature of its translation into performance: the most effective talent strategy depends on its fit with the institution’s underlying knowledge-production model, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chinese public research institutions have become increasingly important players in global academia, driving substantial research investments and outputs, yet they still face criticism for a lack of breakthrough achievements (Cyranoski, 2014; Yang et al., 2023). Some attribute this shortfall to stringent and highly detailed government controls over research budgets, which limit research institutions’ ability to reallocate resources in response to evolving research needs (Cao et al., 2018). Such inflexibility often prevents research institutions from directing funds toward emerging opportunities with high scientific potential, or offering competitive remuneration to attract and retain leading scholars—both of which are widely recognized as critical to achieving major scientific breakthroughs (Jabrane, 2022). In response, the Chinese government launched the Green Channel Reform in 2018, granting 60 leading research institutes and universities greater autonomy in managing both budgetary subsidies and research funds.

However, although financial autonomy constitutes an important influencer on research performance (Sandström and Van den Besselaar, 2018), its effects remain contested (Enders et al., 2013; Gornitzka and Maassen, 2017; Jongbloed and Vossensteyn, 2016; Sandström and Van den Besselaar, 2018). Advocates argue that institutional managers, with their localized knowledge and real-time information, can allocate resources more effectively than government agencies (Bjørnholt et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2019). Conversely, critics emphasize the risks of moral hazard, advocating for transparency, accountability and legitimacy in fund management (Dal Molin et al., 2017; Rasul et al., 2021). Some cross-country comparative studies, which did not include China in the analysis, suggest that financial autonomy may prove counterproductive in developing countries lacking a robust tradition of autonomy (Bezes and Jeannot, 2018; Hanushek et al., 2013). This raises the question of whether China’s pilot reform effectively enhanced research performance, particularly in terms of high-quality research.

Moreover, this reform emerged against the backdrop of chronic underinvestment in personnel funding in Chinese research institutions (Cao et al., 2018; Serger et al., 2015). Given the central role of human resources in knowledge production (Enders et al., 2013), the effectiveness of financial management autonomy may depend on how institutions leverage this flexibility to optimize their talent management strategies. These strategies generally fall into two categories: hiring external talent or developing and incentivizing internal staff (Cappelli, 2008). While previous studies indicate that external hires do not always outperform internal hires, evidence has been drawn from commercial organizations (e.g., Bidwell, 2011). The ‘buy or make’ debate (Cooke et al., 2022) has received little attention in the context of public research institutions, which operate under public funding and unique policy constraints. This gap motivates an essential question: When granted financial management autonomy, how can research institutions transform financial capital into talent strategies that drive high-quality knowledge production?

This study examines the efficacy of the Green Channel reform, employing a difference-in-difference (DID) approach to evaluate the impact of increased autonomy in fund management on research performance of research institutes and universities. To uncover the mechanisms linking autonomy and performance, we investigate two distinct talent strategies: an inward-oriented approach by increasing financial incentives for incumbent staff versus an outward-oriented approach by external recruitment and expanding the organization’s talent pool.

This study offers the following contributions. First, it contributes to the research on the autonomy of public research institutions, offering evidence that supports the positive view towards financial management autonomy (De Boer et al., 2010; Kim and Min, 2020; Smith et al., 2011). Specifically, we show that greater autonomy in funding allocation enhances high-quality research performance, addressing concerns about potential trade-offs between quantity and quality. Second, it advances understanding of the ‘buy or make’ dilemma in the public research sector. Prior studies often treat research institutes and universities as homogeneous knowledge producers (Kruss, 2020; Lian et al., 2021), and comparative analyses have largely been limited to functional and structural differences (Cheah et al., 2020). Our findings reveal that the same policy elicited differential responses: in universities where research activities are organized in an individual-based system, external hiring brings new knowledge and boosts performance; in task-oriented and team-based research institutes, enhancing incentives for internal talent is more effective. Aligning with Tung and Qin (2025), who emphasize that organizational talent strategies carry significant implications in an era of intensified global competition for top talent, the insights from this study of an important policy reform affecting leading public research institutions may hold broader relevance beyond the Chinese context.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: “Research setting” introduces the institutional background and the funding autonomy reform. “Literature and hypotheses” proposes research hypotheses. “Research methodology” describes the data, sample and empirical methods. Empirical results of hypothesis testing and their robustness are presented in “Results”. “Discussion and conclusion” discusses the findings, along with theoretical contributions and policy implications.

Research setting

Public research institutes and universities in China

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, public research institutes and universities have played distinct roles: universities primarily focus on education and talent development, while research institutes concentrate on mission-oriented scientific research. Although these roles have overlapped more in recent decades, important differences remain in mission, funding structures, and research types (Kroll and Schiller, 2010; Xue and Li, 2022). By law, research institutes must ‘serve national goals and public interests’, whereas universities engage in research alongside other responsibilities, without an explicit mission directive.

These institutional distinctions are also reflected in funding sources and research activities. Research institutes receive over 80% of their funding from government sources, compared with about 65% for universities. Research institutes allocate only 15% of R&D spending to basic research and over 50% to experimental development, whereas universities devote around 40% to basic research and 50% to applied research (National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022)).

Such institutional distinctions shape how research is organized and, in turn, the talent strategies each type of institution adopts. Public research institutes, with clearly defined missions, tend to organize work in teams where principal investigators (PIs) recruit team members as needed. In universities where basic research predominates, the PI role is less pronounced. Hiring decisions typically occur at the school or departmental level, and are based largely on individual faculty performance (Sahibzada et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019).

Reform in public research funds deployment

The Chinese government provides two main types of R&D funds to public research institutes and universities: fundamental funds from institutional budget appropriations, and project funds awarded to PIs via competitive grants.

Before 2018, strict restrictions applied to both types of funds. Fundamental funds could not be used for salaries or bonuses and were limited to direct research expenses (equipment, consumables, conference, travel, etc.). Project funds were tied to rigid budget accounts with low overhead rates, leaving institutions little flexibility to reallocate resources toward personnel compensation or performance incentives.

In 2018, the State Council piloted a reform that relaxed these rules for 60 top-tier research institutions, including 28 research institutes and 2 universities within Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) system, and 30 universities affiliated with the Ministry of Education (MOE). CAS institutes (105 in total) are regarded as China’s premier research institutes (Yang et al., 2023), and MOE-affiliated universities (75 in total) represent the country’s elite universities (Serger et al., 2015). Thus, the pilot covered about 30% of China’s top tier public research institutions.

The reform introduced two key changes: (1) Research institutions could now use up to 20% of fundamental funds for personnel costs, with full discretion over allocation criteria and recipients; (2) Allowable overhead rates for project funds increased, and budget procedures were simplified. The maximum overhead rate rose from 20% to 30% for projects under 5 million RMB, from 15% to 25% for those between 5 million and 10 million RMB, and from 13% to 20% for those above 10 million RMB. Importantly, project overheads are retained and managed by the host institution, enhancing their ability to reallocate funds in line with their strategic priorities.

Together, these changes expanded financial management autonomy—the institution-level discretion over the deployment of research funding, notably by newly granted ability to channel fundamental funds and increased project overheads toward personnel remuneration and incentives. This shift marked a milestone in China’s research funding management system, moving from centralized control to greater institutional discretion. Given the long-standing constraints on personnel-related spending in Chinese research institutions (Serger et al., 2015), this autonomy represents not merely a quantitative increase in flexible resources, but also a qualitative enhancement of institutions’ capacity to invest in human capital. Such a change is likely to reshape team composition, strengthen talent incentives, and ultimately influence research productivity.

Literature and hypotheses

Effect of autonomy in financial management on research performance

R&D activities entail considerable uncertainties and information asymmetry (Bakker, 2013; Hall, 2009), which creates a fertile ground for agency risk (Eisenhardt, 1989; Jia et al., 2019). In corporate research, the principal-agent theory advocates reducing information asymmetry through result-oriented contracts and establishing information systems to mitigate moral hazards, thereby avoiding agents pursuing quantity of innovation at the expense of novelty (Hoppe and Schmitz, 2013; Husted, 2007). However, in the context of knowledge-producing organizations, empirical studies on agency risk remain limited. Many scholars believe that granting research institutions greater autonomy (rather than strengthening supervision to obtain more information) can stimulate initiative and encourage high-quality research output (Enkel, 2005; Maassen et al., 2017).

Scholars hold that managers of research institutions have better knowledge and more timely information than government funders regarding how to allocate resources. Thus, greater institutional autonomy should lead to more effectively funding allocation and utilization (Bjørnholt et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2019). Public research institutions are highly specialized, and their scientific activities are complex and uncertain (Bakker, 2013; Wang et al., 2024). Governments, as funding entities, face a persistent principal-agent problem in evaluating research institutions’ efforts and performance (Braun and Guston, 2003; Jia et al., 2019; Maassen et al., 2017). Managers of research institutions typically possess specific knowledge about research processes and prospects, along with a deep understanding of the dynamic nature of scientific activities (Ammons and Roenigk, 2020; Bjørnholt et al., 2022). When granted greater autonomy, they can make timely adjustments to the allocation of funds across periods and categories in response to changing demands, thereby enhancing both the efficiency and effectiveness of the research institutions (Jonek-Kowalska et al., 2021; Kenny and Fluck, 2014; Sukirno and Siengthai, 2011).

Comparative studies support this view. Knott and Payne (2004) found that U.S. public universities under less government regulations achieve better research performance. Mitsopoulos and Pelagidis (2008) discovered that institutions with greater financial autonomy are able to better select and reward staff and to manage their financial affairs, which has a positive correlation with scientific output. In Indonesia, Waluyo (2018) reported that the uniform and detailed regulations imposed by the government on research funding reduce resource-use efficiency. In China, prior research has shown that strict budget controls hinder the efficiency of fund utilization. For example, to comply with budget rules, institutions may purchase equipment that is unnecessary for their research needs (Cao et al., 2018), leading to wasteful expenditures that contribute little to research performance. By contrast, greater autonomy allows institutions to allocate resources according to actual needs, which is likely to enhance research performance. Therefore, we propose our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Financial management autonomy positively affects the research performance of public research institutions.

Mediating effects of talent strategies

As for the mechanisms through which financial management autonomy contributes to enhanced research performance, talent strategies are important. There are many ways that an organization can achieve higher performance through better talent strategy (Flink, 2018; Flink and Molina Jr, 2021; Melkers and Willoughby, 2005). Particularly, financial management autonomy allows public research institutions to allocate resources in ways that directly support human capital development—either by expanding their talent pool through external recruitment or by enhancing the performance of existing personnel through targeted financial incentives. We elaborate on these two mechanisms in turn.

External hiring mechanism

Organizations often recruit externally to address emerging opportunities and meet unmet skill demands, thereby boosting productivity. This is particularly relevant when new opportunities arise while the existing stock of human resources falls short in meeting the developmental requirements (Seeck and Diehl, 2017; Walsh and Lee, 2015).

Chinese universities have historically maintained a high student-to-teacher ratio, with faculty growth lagging behind student enrollment (Ding et al., 2021; Levin and Xu, 2005). National strategies such as ‘innovation-driven development’ and the ‘Double First-class’ initiative have posed new demands for Chinese research institutions to expand their talent pool, placing emphasis on the research capabilities of the staff (Serger et al., 2015). On the supply side, China’s national talent recruitment policies and intensifying global competition have prompted return migration of a growing number of overseas Chinese scholars and scientists (Shi et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2020). The expansion of the number of doctoral graduates, from 9409 in 2000 to 72,019 in 2021, has also led to an increase in the supply of domestic scientific researchers. These demand-side and supply-side factors combined create favorable conditions for external recruitment. The reform on financial management autonomy provides financial support for research institutions to do so. After the reform, these institutions are allowed more rights to allocate funds independently, including staff salary expenditure, at the organizational level, and granted direct access to resources to recruit and develop their staff (Zhang, 2014).

Cross-organizational personnel mobility is an important channel for knowledge transfer and learning (see Argote and Fahrenkopf, 2016, for a review). Newly hired staff bring both explicit and tacit knowledge from prior organizations (Berry and Broadbent, 1987), which can be adapted and integrated into new contexts (Allen, 1984). Knowledge transfer occurs when the mover applies what he or she knows to the recipient organization. The hiring organization can access specific knowledge they lack and to fill skill gaps through targeted knowledge acquisition (Almeida et al., 2003; Marx and Timmermans, 2017). This process, known as “learning-by-hiring”, can generate new competitive advantages (Fahrenkopf et al., 2020; Filatotchev et al., 2011; Rosenkopf and Almeida, 2003).

Past research has pointed to the importance of recruitment in promoting product innovation in corporate settings (Palomeras and Melero, 2010; Rao and Drazin, 2002; Stoyanov and Zubanov, 2014). External hiring can break path dependence in innovation and promote innovative outcomes (Kalleberg and Mouw, 2018; Tzabbar et al., 2022; Wang, 2015). Studies on the context of universities have also found that new personnel, by bringing new knowledge and skills, are instrumental in exchange of ideas and emergence of new, innovative ideas (Baty et al., 1971; Fahrenkopf et al., 2020). Therefore, we hypothesize that budgetary autonomy will lead to an increase in external recruitment and further enhance the research performance of research institutions.

Hypothesis 2. External recruitment mediates the positive relationship between autonomy in financial management and research performance.

Internal incentive mechanism

Financial management autonomy can also result in higher performance in research institutions through an alternative pathway of allocation of funds for provision of higher financial incentives to their research staff. Providing performance-based financial incentives is a common approach to increase individual motivation, effort, and subsequent performance (Garbers and Konradt, 2014; Govindarajulu and Daily, 2004; Prieto and Pilar Pérez Santana, 2012). The incentives clarify the link between effort, performance, and rewards, and thus, enhance the attractiveness of a performance goal (Anderson et al., 2010; Chiang and Birtch, 2012; Y. Yu et al., 2022). Expectancy theory predicts that increased expectancy about the effort-outcome relationship can boost employees’ motivation and focus their attention (Bonner et al., 2000; Garbers and Konradt, 2014). When rewards are clear and tangible, empolyees are likely to invest additional effort to the task and acquire the skills needed to perform the task so that future performance will be higher (Bonner and Sprinkle, 2002; Gagné, 2018). Goal-setting theory and self-regulation theory also point to the positive link between material incentives and performance. The former argues that financial incentives increase the acceptance of achievement goals, which in turn lead to higher performance (Knight et al., 2001; Locke and Latham, 2002). The latter contends that financial incentives enhance individuals’ sense of valence and efficacy, fostering greater commitment, self-efficacy, and performance (Chiaburu, 2010; Gist, 1987). It is generally believed that higher individual effort and better performance are expected to improve overall organizational performance (Lee and Raschke, 2016; Ployhart, 2021).

A meta-analysis by Kim et al. (2022) found that financial incentives consistently boost performance across varying task characteristics and incentive intensities. Similar conclusions have been found in studies on the impact of internal incentives on university publications. Andersen and Pallesen (2008) showed that financial incentives increased the number of publications for universities. Kim and Bak's (2020) study on Korean universities reported that quantity-based bonuses are at least harmless, and potentially beneficial if perceived as supportive rather than controlling.

In China, academic salaries primarily consist of base pay, determined by job position and professional title, and merit pay, linked to research performance. However, base pay is relatively low compared to the United States and Europe, and the proportion of overhead funds available for performance-based incentives is limited (Serger et al., 2015). This constraint often leads academics to allocate time to external consulting activities at the expense of their core research responsibilities (Mohrman et al., 2011). Granting greater financial autonomy could alleviate these limitations, enabling institutions to allocate a larger share of research funding toward performance-based bonuses. These enhanced internal incentives are likely to increase researchers’ motivation and effort, ultimately promoting higher-quality research outputs.

Hypothesis 3. Internal incentivization mediates the positive relationship between financial management autonomy and research performance.

Research methodology

To test these hypotheses, we operationalize the core constructs and implement a quasi-experimental design. This section describes measures, data, sample construction, and models.

Measures and data

Dependent variables

Research performance

Although the performance measure may vary, publications are important channels for research institutions to distribute knowledge and the outcome of their scientific discoveries (Gu et al., 2021; Kim and Min, 2020). Academic publication is thus the most important type of their research outputs. The quantity of research papers has been widely adopted as a measure of research performance (Andrade et al., 2022; Beerkens, 2013; Huang and Chen, 2017).

We use the annual number of papers indexed in Science Citation Index (SCI) for each research institutes and universities as a measure of their research performance (Variable name: Paper). Taking research quality into consideration, we also use a quality-adjusted paper count indicator: the number of highly cited papers selected by Essential Science Indicators (ESI) (Variable name: ESI Paper).

Publication data come from the SCI-Expanded Database provided by Web of Science (WoS), retrieved in September 2022. Using the search query “Affiliation = institution name” and “Year Published = 2016–2021’ in WOS, the total number of papers published by each research institute or university and the number of ESI highly cited papers were collected on an annual basis.

Independent variables

Financial management autonomy

The key explanatory variable is financial management autonomy, measured by the interaction of a policy dummy and a post-reform dummy (Treatment\(\times\)Post). Institutions included in the 2018 pilot are coded Treatment = 1; others = 0. The pilot began in July 2018; to accommodate publication lags, we define 2016–2018 as pre-reform (Post = 0) and 2019–2021 as post-reform (Post = 1).

External Hiring

When a research organization hires more R&D personnel externally, it leads to an increase in the size of their workforce. Therefore, we proxy external hiring by the annual change in R&D personnel: ∆RandD personnel = R&D Personnelt−R&D Personnelt-1.

Internal incentivization

The internal incentivization strategy means that research institutions allocate the additional autonomously controlled funds towards providing higher remuneration incentives to their own existing employees, which results in an increase in the proportion of personnel expenses within the R&D expenditure. It should be noted that, in Chinese statistics, personnel expenses cover regular R&D staff and exclude postdoctoral researchers and short-term assistants; base pay is fixed, so variation in the ratio of personnel expenses to internal R&D expenditure reflects performance-linked remuneration. External hiring can raise total personnel outlays, but does not raise this ratio, because new hires also require non-personnel spending (e.g., equipment). Thus, the ratio of \(P{ersonnel\; expenses}/I\mathrm{nternal\; R\& D\; expenditures}\) more directly reflects internal incentive strength.

Control variables

We control for institution- and region- level factors that may confound the relation between financial management autonomy and research performance. These variables are also used for propensity-score matching.

Size

The headcount of R&D personnel. We only include R&D personnel in science and technology disciplines for universities. In the case of CAS, all its institutes are in science and technology disciplines. In organizational performance studies, organizational size is said to have a positive effect (Ahuja and Katila, 2001).

R&D expenditure

Natural log of annual R&D expenditure (in RMB). For universities, we exclude humanities and social sciences funds and focus only on science and technology funds to align with SCI paper publication. Because the distribution of R&D funding is highly skewed, we use the logarithm of funding.

Age

Years since founding. According to literature, age is clearly linked to organizational performance, because older organizations accumulate more knowledge and experienced staff (Balsmeier et al., 2017).

Labs

Count of national key laboratories affiliated with the research institute or university, a proxy for research infrastructure. In China, these labs are core platforms for undertaking fundamental and applied research, hosting advanced equipment, and attracting top scientists. Institutions with more national key labs, therefore, have stronger research capacity (Wang et al., 2013).

Regions

Dummies for the central and western regions, using the eastern region as the reference group. China’s regional classification reflects both geography and economic development: the eastern region is the most developed, followed by the central, and then the western (Chen and Zheng, 2008; Zhang et al., 2012). Regional differences shape research capacity because developed regions attract more productive scientists and provide richer resources.

The data for R&D expenditure, R&D personnel, external hiring, and internal incentivizing are obtained from Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Academy of Sciences for research institutes and Compilation of Basic Statistical Data of Universities Directly under the Ministry of Education for universities.

Sample selection

Raw sample

The 2018 “Green Channel” pilot reform expanded financial management autonomy for 60 top-tier institutions: 28 CAS research institutes, 2 CAS universities, and 30 MOE-affiliated universities. Because many faculty of CAS universities hold dual appointments with CAS institutes, attribution of outputs is ambiguous; we therefore exclude the two CAS universities and retain the 28 CAS institutes and 30 MOE-affiliated universities.

To form a comparison group, we add all remaining non-pilot CAS institutes (77) and MOE-affiliated universities (45). We then exclude (i) 13 research institutes that underwent mergers or splits between 2015 and 2021; and (ii) 7 research institutes and 11 universities with missing R&D expenditure data. The final raw sample comprises 85 research institutes (23 treated, 62 control) and 64 universities (29 treated, 35 control).

Matching

Given that pilot assignment was non-random, we mitigate selection bias by matching treated institutions to comparable controls. Because research institutes and universities differ in mission and activities, matching is conducted within type: each treated institute (university) is matched only to other institutes (universities).

Propensity score matching (PSM) approach was applied (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983), performed by Stata 17 using the Matching package. After applying logistic regression and caliper matching (with caliper = 0.05), the appropriateness of the matching was assessed with a paired t-test for indicator variables (Table 1). Balance improves substantially, and there are no significant differences in covariate means after matching. We drop unmatched units, yielding a final sample of 58 institutes (18 treated, 40 control) and 39 universities (14 treated, 25 control).

Common trend test

To verify the parallel-trends assumption underlying the difference-in-differences design, we compare the publication trajectories of treated and control institutions before and after the Green Channel Reform. As shown in Fig. 1, both groups exhibit similar performance trends prior to 2018, suggesting no systematic pre-reform differences. Following the reform, however, the trajectories begin to diverge, with treated institutions experiencing a noticeable increase in research performance, particularly in the number of highly cited papers.

Model specification

This paper employs a DID approach to identify the causal effect of financial management autonomy. DID is appropriate here because the reform was introduced in 2018 to a subset of institutions, creating a natural treatment-control contrast. By comparing changes in outcomes over time between treated and untreated institutions, DID controls for both time-invariant institutional characteristics and common temporal shocks, allowing us to isolate the policy’s net effect. We lagged our independent variables and control variables by one year, considering that publication usually shows a certain delay (Yu et al., 2022).

In the first step of analysis, several regression models were applied to test the effects of financial management autonomy on research performance of different types of research institutions. Each of the baseline model with individual-fixed effects and year-fixed effects is specified as follows:

where \({y}_{{it}}\) is the research performance of institution \(i\) (\(i\) = 1,2, …, N) in year \(t\) (\(t\) = 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021); \({X}_{{it}-1}\) is the vector of lagged controls; \({\mu }_{i}\) and \({\gamma }_{t}\) are institution and year fixed; \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) is an error term; \({\beta }_{0}\) is a constant term. The coefficient \({\beta }_{1}\) is the DID estimator, indicating the degree of change in institutions that have implemented financial autonomy compared to those that have not. Our observation window ends in 2021, when the reform expanded nationwide to all CAS institutes and MOE-affiliated universities; beyond 2021, no untreated comparison group remains, which would violate parallel-trends and bias DID estimates.

In the second step, we apply Eqs (2) and (3) to establish the path model, from which we test the mediating effect of external hiring and internal incentivizing:

where \({mediator}\) is external hiring or internal incentivizing. Here, \({\gamma }_{1}\) represents the direct effect from the policy change, \({\gamma }_{3}\) is the effect of mediating variable on research performance, and \({\gamma }_{3}\times {\alpha }_{1}\) corresponds to the indirect effect of the policy through the mediators.

Results

A statistical portrait of two types of research institutions

When comparing research institutes and universities in China, universities have larger and faster-growing research workforces and devote a lower share of R&D to personnel. By contrast, research institutes maintain more stable headcounts and allocate a higher personnel share (Fig. 2). In our final sample, the average research personnel size in universities is 1304, exceeding the 555 in research institutes. Universities’ headcounts grow by 10.35% per year (about 163 researchers), whereas research institutes grow by 1.04% (about 5 researchers). Universities receive substantially larger R&D expenditure, averaging RMB 996 million annually, compared to RMB 642 million for research institutes. Personnel costs only account for 18% of university R&D expenditure, but 40% for research institutes.

The box plot presents the descriptive statistics of 58 Public Research Institutes (RI) and 39 Universities (U) pre- and post-reform. Panel a shows institutional size, b R&D expenditure, c external hiring, d internal incentivizing, e number of papers, and f number of ESI papers. Significance markers denote pre-post differences from paired t-tests (***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1).

In terms of performance, universities publish 2977 papers per year on average, with 1.8% of outputs classified as ESI highly cited. Research institutes publish 521 papers, with 2.3% highly cited. Thus, universities are larger and more productive in quantity, while institutes show a higher proportion of high-impact outputs.

A positive autonomy-performance link

Power checks indicate adequate sample sizes. For universities, the minimum observations for 0.9 power are 148 for papers and 186 for ESI highly cited papers, and those for research institutes are 82 and 54, respectively. In all cases, the sample sizes in our study exceed these requirements. A Hausman test favors fixed effects; therefore, we use institution and year fixed effects in all models.

Table 2 reports standardized DID estimates. Models (1)-(2) were for all research institutions, added with different dependent variables: Paper and ESI Paper, respectively. Models (3)-(4) were for research institutes, and Models (5)-(6) were for universities.

The reform led to an additional 13.2% increase in the total number of publications (p = 0.002) and an additional 26.5% increase in the number of ESI papers (p = 0.001). Specifically, in research institutes, the coefficients are 0.125 (p = 0.020) for papers and 0.301 (p < 0.001) for ESI papers. In universities, the coefficients are 0.183 (p = 0.009) and 0.321 (p = 0.016) respectively. Given that R&D expenditure is controlled in the DID, improvements are attributable to enhanced autonomy rather than larger budgets. Hence, H1 is supported: financial management autonomy increases research performance of research institutions.

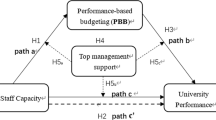

Distinct pathways to enhanced research productivity

We further investigate how research institutes and universities adopt different talent strategies to enhance performance, using a path analysis framework. The results for research institutes are shown in Panel a, Fig. 3. Financial management autonomy is associated with a 32.0% increase in headcount (marginally significant, p = 0.071) and a 36.6% increase in internal incentive expenditure (p = 0.038). Yet, only internal incentives significantly predict research outputs, raising total papers by 4.2% (p = 0.018) and ESI papers by 9.4% (p = 0.001). In contrast, external hiring shows no significant association with outputs (β = −0.006, p = 0.662 for papers; β = −0.006, p = 0.772 for ESI papers). These results indicate that, after gaining financial management autonomy, research institutes primarily channel discretionary funds into internal incentives rather than expanding headcount. This strategy effectively enhances both the quantity and quality of research outputs. By contrast, external hiring, though adopted to some extent, yields weaker significance levels and does not translate into improved performance.

The results for universities are shown in Panel b, Fig. 3. Financial management autonomy increased headcount by 89.6% (p < 0.001), and this expansion significantly predicts research outputs, both the total number of publications (β = 0.092, p < 0.001) and high-impact ones (β = 0.132, p = 0.002). However, the impact of financial autonomy on internal incentives is not significant (β = 0.113, p = 0.577). These results suggest that after gaining higher financial management autonomy, universities prioritize external hiring, and this strategy raises both quantity and quality of their publications.

Robustness check of the direct effect

Placebo test

To address concerns about unobserved factors that might simultaneously influence both the assignment of autonomy and research performance, we conduct a placebo test. Following previous studies (e.g., La Ferrara et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016), we implement placebo DID tests by repeatedly (500 times) assigning institutions to “fictitious” treated and control groups of the same sizes as the real sample and re-estimating Eq. (1). The placebo coefficients for Treatment × Post are centered near zero, and the actual estimate (vertical dashed line) lies in the tails of the placebo distribution (See Fig. 4). Most placebo p values exceed 0.10 (horizontal dashed line), indicating no spurious effects. These patterns support the interpretation that the main DID results are policy-driven rather than artifacts of omitted factors.

Alternative estimators, measures, and samples

We conduct four sets of robustness checks, and the results are reported in Table 3. In Model 7A-7F, we re-estimate the model using Poisson regression, given that our dependent variables are count measures. In Models 8A-8F, we replace the dependent variable with publications per person rather than total publications. In Model 9A-9F, we winsorize the sample at the top and bottom1%, since research performance is unevenly distributed, with some organizations publishing disproportionately many papers while others publish very few. In Models 10A-10F, we re-match the treated and control groups using kernel matching as an alternative PSM method, which produces a new sample of 76 research institutes and 45 universities.

The results from all four sets of robustness checks remain consistent with the baseline regressions, reinforcing the positive effects of greater financial management autonomy. The only exception is that the effect on publications per person becomes insignificant for universities. A plausible explanation is that universities often improve research performance not by intensifying per capita output, but by expanding their faculty through external recruitment—a mechanism that we explicitly test in the path analysis. Hence, the lack of significance in per-person outputs does not undermine our findings; rather, it provides additional support for the mediating role of talent strategies.

Heterogeneity by organizational size and region

To further assess the stability and variation of the results across different types of organizations, we examine heterogeneity by institutional size and regional location (See Table 4). Models 11A–11D present scale heterogeneity. We divide the sample into small-scale and large-scale institutions based on staff size, and then estimate the effects separately. Although the reduced sample sizes within each subgroup weaken statistical significance, the direction of the coefficients remains consistent with the baseline models.

Models 12A–12D show regional heterogeneity. Considering both sample sizes and the structural differences across regions, we categorize institutions into eastern (more developed) and central/western (less developed) regions. The results suggest that the positive effects of financial management autonomy are stronger for institutions in central and western regions, while in the more developed eastern region, the reform mainly promotes the production of highly cited papers without significantly increasing the number of general publications.

Discussion and conclusion

Our empirical analysis demonstrates that the Green Channel pilot reform targeting at leading national research institutes and universities has yielded some promising results. Greater financial management autonomy improved research performance, enhancing both the quantity and quality of research outputs, with particularly strong effects on high-quality publications. Moreover, the analysis reveals contrasting strategies in how research institutes and universities leverage their autonomy, reflecting fundamental differences in talent strategies between the two types of research institutions.

Drivers for different paths for research institutes and universities

The findings show that universities and research institutes adopted different approaches in utilizing the granted autonomy: universities enhanced performance by expanding external recruitment, whereas research institutes focused on internal incentivization. These contrasting strategies, along with their varying degrees of success, are likely shaped by distinct knowledge production models and compensation structures.

In universities, research staff are typically hired, evaluated, and promoted at the school or departmental level on the basis of individual performance. Most top-tier Chinese universities now operate a tenure-track system, under which faculty are hired on fixed-term contracts with specific research performance targets. At the end of the contractual period, renewal or termination is decided primarily on individual basis (Serger et al., 2015). While collaboration among faculty is common, each researcher essentially enters and advances within the university as an individual—manifesting in an individual-based model of knowledge production. This system facilitates high cross-organizational mobility and open labor market of universities (Mawdsley and Somaya, 2016), enabling them to acquire new expertise and skills through external hiring. As a result, when financial management autonomy expanded after the Green Channel Reform, universities were institutionally positioned to prioritize external recruitment as a central talent strategy.

By contrast, research institutes in the CAS system have a clear mission orientation of advancing application-oriented basic research and cutting-edge technologies research. To fulfil this mission, research activities are primarily organized through PI-led teams. PIs have substantial authority to recruit and retain team members, with selection guided not only by candidates’ qualifications but also by their fit with the team’s research objectives, workflow, and required capabilities (Zweig et al., 2020). Evaluation and career advancement for team members are closely tied to team performance, and the division of labor within teams is highly specialized. Given this team-based knowledge production model, external hires may lack the precise expertise needed for ongoing projects and face steep learning curves (Fahrenkopf et al., 2020). Consequently, research institutes have adopted a more conservative talent strategy. When provided with greater financial management autonomy, they tended to retain and incentivize existing members rather than expand through large-scale recruitment.

Theoretical contributions

This research contributes to public science management studies in two key ways. First, it provides empirical evidence for the longstanding debate over autonomy versus control in public research institutions (Capano and Pritoni, 2020; Enders et al., 2013). Government oversight of funding aims to ensure transparency and accountability, but our findings support the view that financial management autonomy enhances performance (Dasgupta and Paul, 1994; Shin and Jung, 2014). Notably, the improvement appears to be more pronounced in high-quality research outputs, highlighting the distinct advantages of autonomy in fostering excellence in academic achievements. This suggests that granting autonomy enables research institutions to leverage their specialized knowledge and allocate resources more effectively, in line with the complex and dynamic nature of scientific activities. Direct government management, by contrast, can be constrained by information asymmetry and the inherent uncertainties of research processes. Overall, the results imply that reducing administrative restrictions and empowering the agency may be a more effective way to support knowledge production.

Second, this study extends research on talent management in public research institutions. Prior work has focused on corporate contexts, showing that external hires bring new skills while internal incentives motivate value creation (Bidwell, 2011; Gerhart and Feng, 2021; Kalleberg and Mouw, 2018). However, limited attention has been paid to how organizational context shapes the effectiveness of these strategies. By comparing universities and research institutes, this study suggests that success depends on knowledge production models: task-oriented and team-based research institutes tend to benefit more from internal incentives, while universities, with individual-based systems and open labor markets, may gain more from external recruitment. This underscores the critical role of contextual factors in determining talent strategy outcomes, offering new insights into managing human capital in public research institutions.

Policy implications

Although the Chinese government is known for its proactive and detailed management of R&D funds (Cao et al., 2018), stringent oversight of public R&D funding is not unique to China. Many governments worldwide face similar pressures to ensure transparency, accountability, and legitimacy in allocating research funds (Dal Molin et al., 2017). In this broader context, and amid intensifying global competition for top talent (Tung and Qin, 2025), the insights of this study may have broader relevance beyond the Chinese context.

First, in an era of stagnating or declining R&D budgets (O’Grady, 2022; Owens, 2022), financial autonomy could serve as a cost-effective policy tool. It allows research institutions to optimize resource allocation, tailoring strategies to their unique contexts and research priorities. This approach may enhance research performance without requiring additional investment.

Second, for universities, external recruitment has become especially valuable, as the rapid renewal of knowledge and the growing importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration (Leahey and Barringer, 2020). Policymakers should therefore support open labor markets that enhance mobility and enable universities to attract diverse talent.

Third, as emerging fields like artificial intelligence and biotechnology demand rapid progress and specialized expertise, governments worldwide are transitioning from large-scale national laboratories to smaller, mission-oriented research institutes. In this context, it is critical to design incentive packages to attract, retain, and motivate research teams. The incentive mechanisms should balance creative exploration with the accumulation of specialized knowledge needed to achieve mission-specific goals.

Limitations and future research directions

This study has several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, it does not capture the long-term effects of financial management autonomy. After three years of pilot implementation, the Green Channel Reform was scaled up to all CAS institutes and MOE-affiliated universities, eliminating the untreated comparison group required for a DID design and thereby constraining our observation window. Future studies could adopt alternative identification strategies to assess the reform’s lasting consequences.

Second, due to the use of institutional-level data, our measures of mediating talent strategies—external hiring and internal incentives—capture scale but not quality dimensions, such as seniority of recruits or specific incentive structures. The dataset also lacks disciplinary breakdowns, which may shape research practices and outcomes. Future research linking individual- and institutional-level microdata could provide richer insights into these strategies and their heterogeneous effects.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VCFYGW.

References

Ahuja G, Katila R (2001) Technological acquisitions and the innovation performance of acquiring firms: a longitudinal study. Strategic Manag J 22(3):197–220

Allen TJ (1984) Managing the flow of technology: technology transfer and the dissemination of technological information within the R&D organization. MIT Press

Almeida P, Dokko G, Rosenkopf L (2003) Startup size and the mechanisms of external learning: increasing opportunity and decreasing ability? Res Policy 32(2):301–315

Ammons DN, Roenigk DJ (2020) Exploring devolved decision authority in performance management regimes: the relevance of perceived and actual decision authority as elements of performance management success. Public Perform Manag Rev 43(1):28–52

Andersen LB, Pallesen T (2008) ‘Not just for the money?’ How financial incentives affect the number of publications at Danish research institutions. Int Public Manag J 11(1):28–47

Anderson SW, Dekker HC, Sedatole KL (2010) An empirical examination of goals and performance-to-goal following the introduction of an incentive bonus plan with participative goal setting. Manag Sci 56(1):90–109

Andrade EP, Pereira JdS, Rocha AM, Nascimento MLF (2022) An exploratory analysis of Brazilian universities in the technological innovation process. Technol Forecast Soc Change 182:121876

Argote L, Fahrenkopf E (2016) Knowledge transfer in organizations: the roles of members, tasks, tools, and networks. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 136:146–159

Bakker G (2013) Money for nothing: How firms have financed R&D-projects since the Industrial Revolution. Res Policy 42(10):1793–1814

Balsmeier B, Fleming L, Manso G (2017) Independent boards and innovation. J Financ Econ 123(3):536–557

Baty GB, Evan WM, Rothermel TW (1971) Personnel flows as interorganizational relations. Adm Sci Q 16(4):430–443

Beerkens M (2013) Facts and fads in academic research management: the effect of management practices on research productivity in Australia. Res Policy 42(9):1679–1693

Berry DC, Broadbent DE (1987) The combination of explicit and implicit learning processes in task control. Psychol Res 49(1):7–15

Bezes P, Jeannot G (2018) Autonomy and managerial reforms in Europe: let or make public managers manage? Public Adm 96(1):3–22

Bidwell M (2011) Paying more to get less: the effects of external hiring versus internal mobility. Adm Sci Q 56(3):369–407

Bjørnholt B, Boye S, Mikkelsen MF (2022) Balancing Managerialism and Autonomy: a panel study of the link between managerial autonomy, performance goals, and organizational performance. Public Perform Manag Rev 45(1):1–29

Bonner SE, Hastie R, Sprinkle GB, Young SM (2000) A review of the effects of financial incentives on performance in laboratory tasks: Implications for management accounting. J Manag Acc Res 12(1):19–64

Bonner SE, Sprinkle GB (2002) The effects of monetary incentives on effort and task performance: theories, evidence, and a framework for research. Acc Organ Soc 27(4-5):303–345

Braun D, Guston DH (2003) Principal-agent theory and research policy: an introduction. Sci Public Policy 30(5):302–308

Cao C, Li N, Li X, Liu L (2018) Reform of China’s science and technology system in the Xi Jinping Era. China Int J, 16(3):120–141

Capano G, Pritoni A (2020) Exploring the determinants of higher education performance in Western Europe: a qualitative comparative analysis. Regul Gov 14(4):764–786

Cappelli P (2008) Talent management for the twenty-first century. Harv Bus Rev 86(3):74–81

Cheah SL-Y, Yuen-Ping H, Shiyu L (2020) How the effect of opportunity discovery on innovation outcome differs between DIY laboratories and public research institutes: the role of industry turbulence and knowledge generation in the case of Singapore. Technol Forecast Soc Change 160:120250

Chen M, Zheng Y (2008) China’s regional disparity and its policy responses. China World Econ 16(4):16–32

Chiaburu DS (2010) Chief executives’ self-regulation and strategic orientation: a theoretical model. Eur Manag J 28(6):467–478

Chiang FF, Birtch TA (2012) The performance implications of financial and non‐financial rewards: an Asian Nordic comparison. J Manag Stud 49(3):538–570

Cooke GB, Chowhan J, Mac Donald K, Mann S (2022) Talent management: four “buying versus making” talent development approaches. Pers Rev 51(9):2181–2200

Cyranoski D (2014) Chinese science gets mass transformation: teamwork at centre of Chinese Academy of Sciences reform. Nature 513(7519):468–470

Dal Molin M, Turri M, Agasisti T (2017) New public management reforms in the Italian universities: Managerial tools, accountability mechanisms or simply compliance? Int J Public Adm 40(3):256–269

Dasgupta P, Paul AD (1994) Toward a new economics of science. Res Policy 23(5):487–521

De Boer HF, Jongbloed B, Enders J, File J (2010) Progress in higher education reform across Europe (Governance reform 1: Executive summary and main report). European Commission

Ding Y, Wu Y, Yang J, Ye X (2021) The elite exclusion: stratified access and production during the Chinese higher education expansion. High Educ 82:323–347

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):57–74

Enders J, De Boer HF, Weyer E (2013) Regulatory autonomy and performance: the reform of higher education re-visited. High Educ 65(1):5–23

Enkel M (2005) Academic identity and autonomy in a changing policy environment. High Educ 49:155–176

Fahrenkopf E, Guo J, Argote L (2020) Personnel mobility and organizational performance: the effects of specialist vs. generalist experience and organizational work structure. Organ Sci 31(6):1601–1620

Filatotchev I, Liu X, Lu J, Wright M (2011) Knowledge spillovers through human mobility across national borders: evidence from Zhongguancun Science Park in China. Res Policy 40(3):453–462

Flink CM (2018) Ordering chaos: the performance consequences of budgetary changes. Am Rev Public Adm 48(4):291–300

Flink CM, Molina Jr AL (2021) Improving the performance of public organizations: financial resources and the conditioning effect of clientele context. Public Adm 99(2):387–404

Gagné M (2018) From strategy to action: transforming organizational goals into organizational behavior. Int J Manag Rev 20:S83–S104

Garbers Y, Konradt U (2014) The effect of financial incentives on performance: a quantitative review of individual and team‐based financial incentives. J Occup Organ Psychol 87(1):102–137

Gerhart B, Feng J (2021) The resource-based view of the firm, human resources, and human capital: progress and prospects. J Manag 47(7):1796–1819

Gist ME (1987) Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Acad Manag Rev 12(3):472–485

Gornitzka Å, Maassen P (2017) European Flagship universities: autonomy and change. High Educ Q 71(3):231–238

Govindarajulu N, Daily BF (2004) Motivating employees for environmental improvement. Ind Manag Data Syst 104(4):364–372

Gu H, Yu H, Sachdeva M, Liu Y (2021) Analyzing the distribution of researchers in China: an approach using multiscale geographically weighted regression. Growth Change 52(1):443–459

Hall BH (2009) The financing of innovation. In: Shane S (ed) The handbook of technology and innovation management. Wiley-Blackwell, pp 409–430

Hanushek EA, Link S, Woessmann L (2013) Does school autonomy make sense everywhere? Panel estimates from PISA. J Dev Econ 104:212–232

Hoppe EI, Schmitz PW (2013) Contracting under incomplete information and social preferences: an experimental study. Rev Econ Stud 80(4):1516–1544

Huang M-H, Chen D-Z (2017) How can academic innovation performance in universit-industry collaboration be improved? Technol Forecast Soc Change 123:210–215

Husted BW (2007) Agency, information, and the structure of moral problems in business. Organ Stud 28(2):177–195

Jabrane L (2022) Individual excellence funding: effects on research autonomy and the creation of protected spaces. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–9

Jia N, Huang KG, Man Zhang C (2019) Public governance, corporate governance, and firm innovation: an examination of state-owned enterprises. Acad Manag J 62(1):220–247

Jonek-Kowalska I, Musio-Urbańczyk A, Podgórska M, Wolny M (2021) Does motivation matter in evaluation of research institutions? Evidence from Polish public universities. Technol Soc 67:101782

Jongbloed B, Vossensteyn H (2016) University funding and student funding: international comparisons. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 32(4):576–595

Kalleberg AL, Mouw T (2018) Occupations, organizations, and intragenerational career mobility. Annu Rev Socio 44:283–303

Kenny JDJ, Fluck AE (2014) The effectiveness of academic workload models in an institution: a staff perspective. J High Educ Policy Manag 36(6):585–602

Kim DH, Bak H-J (2020) Reconciliation between monetary incentives and motivation crowding-out: the influence of perceptions of incentives on research performance. Public Perform Manag Rev 43(6):1292–1317

Kim JH, Gerhart B, Fang M (2022) Do financial incentives help or harm performance in interesting tasks? J Appl Psychol 107(1):153

Kim W, Min S (2020) The effects of funding policy change on the scientific performance of government research institutes. Asian J Technol Innov 28(2):272–283

Knight D, Durham CC, Locke EA (2001) The relationship of team goals, incentives, and efficacy to strategic risk, tactical implementation, and performance. Acad Manag J 44(2):326–338

Knott JH, Payne AA (2004) The impact of state governance structures on management and performance of public organizations: a study of higher education institutions. J Policy Anal Manag 23(1):13–30

Kroll H, Schiller D (2010) Establishing an interface between public sector applied research and the Chinese enterprise sector: preparing for 2020. Technovation 30(2):117–129

Kruss G (2020) Balancing multiple mandates: a case study of public research institutes in South Africa. Sci Public Policy 47(2):149–160

La Ferrara E, Chong A, Duryea S (2012) Soap operas and fertility: evidence from Brazil. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(4):1–31

Leahey E, Barringer SN (2020) Universities’ commitment to interdisciplinary research: to what end? Res Policy 49(2):103910

Lee MT, Raschke RL (2016) Understanding employee motivation and organizational performance: arguments for a set-theoretic approach. J Innov Knowl 1(3):162–169

Levin HM, Xu Z (2005) Issues in the expansion of higher education in the People’s Republic of China. China Rev 5(1)33–59

Li P, Lu Y, Wang J (2016) Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J Dev Econ 123:18–37

Lian X, Guo Y, Su J (2021) Technology stocks: a study on the characteristics that help transfer public research to industry. Res Policy 50(10):104361

Locke EA, Latham GP (2002) Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol 57(9):705–717

Maassen P, Gornitzka Å, Fumasoli T (2017) University reform and institutional autonomy: a framework for analysing the living autonomy. High Educ Q 71(3):239–250

Marx M, Timmermans B (2017) Hiring molecules, not atoms: comobility and wages. Organ Sci 28(6):1115–1133

Mawdsley JK, Somaya D (2016) Employee mobility and organizational outcomes: an integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J Manag 42(1):85–113

Melkers J, Willoughby K (2005) Models of performance‐measurement use in local governments: understanding budgeting, communication, and lasting effects. Public Adm Rev 65(2):180–190

Mitsopoulos M, Pelagidis T (2008) Comparing the administrative and financial autonomy of higher education institutions in 7 EU countries. Intereconomics 43(5):282–288

Mohrman K, Geng Y, Wang Y (2011) Faculty life in China. The NEA 2011 Almanac of Higher Education. National Education Association

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022). China statistical yearbook on science and technology [M]. Beijing: China Statistics Press [In Chinese]

O’Grady C (2022) Upheaval in Norwegian science funding threatens grants. Science 376(6597):1031–1031

Owens B (2022) In Canada, scientists are struggling with stagnant funding. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/canada-scientists-are-struggling-stagnant-funding. Accessed 22 Oct 2025

Palomeras N, Melero E (2010) Markets for inventors: learning-by-hiring as a driver of mobility. Manag Sci 56(5):881–895

Ployhart RE (2021) Resources for what? Understanding performance in the resource-based view and strategic human capital resource literatures. J Manag 47(7):1771–1786

Prieto IM, Pilar Pérez Santana M (2012) Building ambidexterity: the role of human resource practices in the performance of firms from Spain. Hum Resour Manag 51(2):189–211

Rao H, Drazin R (2002) Overcoming resource constraints on product innovation by recruiting talent from rivals: a study of the mutual fund industry, 1986-1994. Acad Manag J 45(3):491–507

Rasul I, Rogger D, Williams MJ (2021) Management, organizational performance, and task clarity: evidence from Ghana’s civil service. J Public Adm Res Theory 31(2):259–277

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

Rosenkopf L, Almeida P (2003) Overcoming local search through alliances and mobility. Manag Sci 49(6):751–766

Sahibzada UF, Jianfeng C, Latif KF, Sahibzada HF (2020) Fueling knowledge management processes in Chinese higher education institutes (HEIs): the neglected mediating role of knowledge worker satisfaction. J Enterp Inf Manag 33(6):1395–1417

Sandström U, Van den Besselaar P (2018) Funding, evaluation, and the performance of national research systems. J Informetr 12(1):365–384

Seeck H, Diehl M-R (2017) A literature review on HRM and innovation—taking stock and future directions. Int J Hum Resour Manag 28(6):913–944

Serger SS, Benner M, Liu L (2015) Chinese university governance: tensions and reforms. Sci Public Policy 42(6):871–886

Shi D, Liu W, Wang Y (2023) Has China’s Young Thousand Talents program been successful in recruiting and nurturing top-caliber scientists? Science 379(6627):62–65

Shin JC, Jung J (2014) Academics job satisfaction and job stress across countries in the changing academic environments. High Educ 67:603–620

Smith S, Ward V, House A (2011) ‘Impact’ in the proposals for the UK’s Research Excellence Framework: shifting the boundaries of academic autonomy. Res Policy 40(10):1369–1379

Stoyanov A, Zubanov N (2014) The distribution of the gains from spillovers through worker mobility between workers and firms. Eur Econ Rev 70:17–35

Sukirno DS, Siengthai S (2011) Does participative decision making affect lecturer performance in higher education? Int J Educ Manag 25(5):494–508

Tung RL, Qin F (2025) Hyperglobalization at a crossroads: revisiting research on global mobility. J Int Bus Stud. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-025-00792-0

Tzabbar D, Lee J, Seo D (2022) Collaborative structure and post‐mobility knowledge spillovers: a dyadic approach. Strateg Manag J 43(9):1728–1762

Walsh JP, Lee Y-N (2015) The bureaucratization of science. Res Policy 44(8):1584–1600

Waluyo B (2018) Balancing financial autonomy and control in agencification: issues emerging from the Indonesian higher education. Int J Public Sect Manag 31(7):794–810

Wang D (2015) Activating cross-border brokerage: interorganizational knowledge transfer through skilled return migration. Adm Sci Q 60(1):133–176

Wang QM, Zhao XN, Zhang LL (2013) A novel thought and method of university evaluation. Int J Educ Manag Eng 3(2):59–65

Wang Y, Li P, Gao H, Li M (2024) Do the elite university projects promote scientific research competitiveness: evidence from NSFC grants. Res Policy 53(10):105074

Xue E, Li J (2022) Cultivating high-level innovative talents by integration of science and education in China: a strategic policy perspective. Educ Philos Theory 54(9):1419–1430

Yang X, Zhou X, Cao C (2023) Remaking the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science 379(6629):240–243

Yu N, Dong Y, De Jong M (2022) A helping hand from the government? How public research funding affects academic output in less-prestigious universities in China. Res Policy 51(10):104591

Yu Y, Khern-am-nuai W, Pinsonneault A (2022) When paying for reviews pays off: the case of performance-contingent monetary rewards. MIS Q 46(1):599–630

Zhang J (2014) Developing excellence: Chinese university reform in three steps. Nature 514(7522):295–296

Zhang R, Sun K, Delgado MS, Kumbhakar SC (2012) Productivity in China’s high technology industry: regional heterogeneity and R&D. Technol Forecast Soc Change 79(1):127–141

Zhang Y, Chen K, Fu X (2019) Scientific effects of Triple Helix interactions among research institutes, industries and universities. Technovation 86:33–47

Zhao Z, Bu Y, Kang L, Min C, Bian Y, Tang L, Li J (2020) An investigation of the relationship between scientists’ mobility to/from China and their research performance. J Informetr 14(2):101037

Zweig D, Siqin K, Huiyao W (2020) ‘The best are yet to come:’ state programs, domestic resistance and reverse migration of high-level talent to China. J Contemp China 29(125):776–791

Acknowledgements

Dingyi You acknowledges support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 72304264), and Ke Wen from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 71974185).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: DY, KW, FQ; methodology: DY, LT; investigation: DY, KW; visualization: DY, DS; writing—original draft: DY, FQ, DS; writing — review & editing: DY, FQ, LT, KW; supervision: KW; project administration: KW.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, D., Wen, K., Qin, F. et al. Divergent pathways from autonomy to performance: talent strategies in top Chinese public research institutions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1902 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06168-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06168-x