Abstract

Live commerce has become one of the mainstream retail channels, and thus the anchor who connects live commerce and customers has become significant in cultivating loyal customers. Unlike existing literature that focuses on the relationship between anchors’ behavioral characteristics and customer attitudes, this study starts with the anchors’ emotional characteristics to investigate the impact of their emotional labor strategies on customer attitude loyalty. Based on ‘emotion as social information theory,’ this study develops a relationship model among customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy, perceived customer orientation and customer attitude loyalty. It also explores the effect of the accuracy of customers’ detection of emotional labor strategy on the relationship among the three variables. This study collected paired questionnaires from 42 anchors and 331 customers engaged in the live commerce industry, and conducted hypothesis testing through regression analysis. The results reveal that in the context of live-commerce: (1) Customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy positively affects customer attitude loyalty, where perceived customer orientation mediates the effect; (2) The accuracy of customers’ detection of deep acting positively moderates the relationship between the detection of the anchor’s deep acting and perceived customer orientation, whereas the accuracy of customers’ detection of surface acting has the opposite effect; (3) The accuracy of customers’ detection of deep acting positively moderates the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation in the relationship between the detection of anchors’ deep acting and customer attitude loyalty, whereas the accuracy of customers’ detection of surface acting has the opposite effect. Taking the perspective of the anchor’s emotional characteristics, this study not only reveals the mechanism and boundary conditions of how the detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy affects customer attitude loyalty, but also provides important practical insights for live commerce companies to cultivate customer loyalty behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Live commerce is one of the mainstream retail channels (Bai et al., 2024), and thus, the anchor who connects live commerce and customers has become significant for cultivating loyal customers (Chen et al., 2024). As of December 2024, the ‘55th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China,’ released by the China Internet Network Information Center, states that the number of webcasting users in China has exceeded 833 million, accounting for 75.2% of the total number of netizens (CNNIC, 2025). This implies that webcasting has become a favored social platform for netizens, and live commerce is expected to drive more consumption. Owing to the virtuality of live commerce, customers cannot touch and feel products immediately (Sarkar et al., 2024; Chu et al., 2025); therefore, the anchor naturally becomes the key person to supplement the full sensory information of the products (Chen et al., 2024). Unlike traditional service situations, the anchor’s description and interactive behavior determine the quantity and quality of product information received by customers in the context of live commerce (Wang et al., 2024b), which implies that the professionalism and interactivity of the anchor will significantly enhance the shopping experience and loyalty of customers (Li et al., 2024; Li et al., 2021). Meanwhile, fast delivery enables customers to receive products quickly (Mridha et al., 2024) and evaluate them according to anchors’ explanations, indicating that anchors need to provide more vivid and detailed explanations to retain customers (Meng et al., 2021). Additionally, existing studies explored the impact of anchors’ behavioral characteristics on consumers’ impulse-buying behavior from the perspective of consumer detection (Li et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2024b). Li et al. (2024) found that the similarity, attractiveness, professionalism, and interactivity of the anchor affect consumers’ impulse purchasing behavior by enhancing their pleasure. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022b) found that the anchor’s professionalism, fame, interactivity, and affinity affect the communication with consumers, thereby affecting the latter’s immediate purchasing behavior. Moreover, Zhang et al. (2024b) found that anchor characteristics, time pressure, and live-streaming activity can induce impulsive purchases by stimulating consumer vulnerability. Therefore, the study of the impact of anchors’ characteristics and interactive behavior on customer attitude and behavior in the context of live commerce has become an important topic in theory as well as practice.

Existing literature focuses primarily on the impact of the anchor’s behavioral characteristics, such as similarity, professionalism, and interactivity, on consumers’ purchasing behaviors (Li et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2024b). However, in the context of live commerce, anchors also have important emotional characteristics (Luo et al., 2024). Moreover, emotional interactions play a dominant role in anchor-customer interactions (Meng et al., 2021), and have a non-negligible impact on customer loyalty behavior (Zhang et al., 2022a). Therefore, this study begins with the following three aspects: (1) the mechanism between anchors’ emotional characteristics and customer loyalty behavior (Shi et al., 2021); (2) the principle of emotional matching between anchors and customers (Shena et al., 2022); and (3) the application of customers’ emotion detection accuracy (Gong et al., 2020).

Based on the ‘emotions as social information theory’, this study explores the relationship between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies and customer attitude loyalty in live commerce, analyzing the mediating role of perceived customer orientation. Further, considering the high emotional contagion in the context of live commerce (Meng et al., 2021), this study considers the accuracy of customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies as a moderating variable and analyzes whether the relationship between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy and customer loyalty is different, and whether perceived customer orientation plays a different mediating role under different emotional detection accuracies.

Theory and hypotheses

Emotions as social information theory

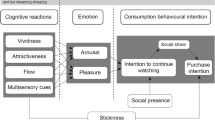

Based on the ‘emotion as social function theory’, Van Kleef (2009) constructed the Emotion as Social Information Model (EASI). The model proposes that people’s emotions can affect others’ cognition and behavior through two paths: the affective reaction and the inferential paths. The former refers to influencing the behavior of emotional observers by providing contextual information, while the latter refers to influencing observers’ behavior by affecting their emotions and their preferences toward the expresser. Based on this model, Wang et al. (2017) found that employees’ emotional intensity affects customer loyalty and purchase decisions mainly through emotional reactions, whereas emotional authenticity affects customers’ loyalty through their inferential process. Liu et al. (2019) also found that while facing emotionally negative customers, the positive personality and effective communication of service employees can alleviate the adverse emotional impact during the service process, thereby improving the overall evaluation of service quality by customers.

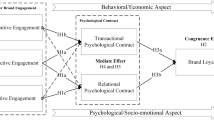

Compared to traditional service contexts, live commerce, with high emotional infectivity, allows greater transmission of emotional information (Meng et al., 2021). In this context, based on the emotional information received from anchors, customers judge whether their emotions are genuine and whether they sincerely provide service. Fake or superficial emotions will cause customers to detect anchors negatively, reducing their willingness to cooperate (Chen et al., 2024; Meng et al., 2021). Meanwhile, the sustainable development of live broadcasting requires shifting the focus from attracting consumers’ short-term purchasing behavior to cultivating long-term loyal behavior (Zhang et al., 2022a; Frennea et al., 2017). Therefore, it is particularly important to study the application of emotion as a social information theory in the context of live commerce. Based on this theory, this study constructs a theoretical model, with the detection of emotional labor strategy as the independent variable, perceived customer orientation as the mediating variable, customer attitude loyalty as the dependent variable, and the detection accuracy of emotional labor strategy as the moderating variable.

Customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy

In the field of organizational behavior, Hochschild (1983) first proposed that an emotional labor strategy is an emotional regulation behavior. It requires employees to follow the specific requirements of the organization for service emotions during the work process to achieve effective management and expression of emotions, and divide the strategy into surface and deep acting behaviors. The former refers to individuals keeping their inner emotions unchanged and only adjusting external emotional expressions. The latter refers to achieving consistency between internal and external emotions through deep inner thought. In the context of live commerce, anchors also need to use appropriate emotional labor strategies to meet customers’ emotional needs (Zhang et al., 2024a). Therefore, this study refers to the definition of Hochschild (1983), Grandey (2000) and Itani et al. (2025) and defines the emotional labor strategy of e-commerce anchors as the process by which they actively regulate and manage their emotions in response to the emotional expression requirements of the organization, adopting a two-dimensional division of surface and deep acting behavior.

Perceived customer orientation

According to Marques (2018), customer orientation refers to the practice of enterprises or organizations to accord significance to customers’ needs, expectations, and satisfaction during their operations and decision-making. This involves actively attending to and responding to customer feedback, opinions, and preferences to provide higher-quality products, services, and experiences. Perceived customer orientation refers to the extent to which customers perceive that service personnel meet their needs within their interactions (Hennig, 2004; Stuhldreier et al., 2024). In the context of live commerce, the high contagiousness of emotions facilitates customers to perceive the anchors’ emotional investment (Meng et al., 2021). Therefore, this study considers that the definitions of Hennig (2004) and Stuhldreier (2024) are also applicable in this context, and proposes perceived customer orientation as the degree to which customers perceive the concern and fulfillment of their needs by the anchor during interactions.

Customer attitude loyalty

Compared with traditional contexts, the high interactivity of live commerce enhances the manifestation of customer attitude loyalty, which includes purchasing the live broadcast products or services and actively recommending them to others (So et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2022a). Based on So et al. (2025) and Zhang et al. (2022a), this study measures customer attitude loyalty in terms of two dimensions: purchase intention and recommendation intention. Meanwhile, we define the purchase and recommendation intentions of customers in the live commerce context as follows. The former refers to the degree to which customers express a desire to purchase live broadcast products or services, and the latter refers to the degree to which customers are willing to recommend live broadcast products or services to others in their social networks.

Customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy and customer attitude loyalty

Different scholars have explained the impact of emotional labor strategies on customer attitudes and behaviors differently (Groth et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2020). Specifically, Groth et al. (2009) found that employee emotional labor affects customer loyalty intention through perceived customer orientation, while Gong et al. (2020) considered that customers’ detection of employees’ emotional labor affects their loyalty through their emotions. There are differences in the mediation in the two studies. Meanwhile, So et al. (2025) pointed out that given the dynamic changes in market environments, measuring attitudinal loyalty can better identify valuable consumers. Based on this, this study believes that in the context of live commerce, compared to behavioral loyalty, attitudinal loyalty can better reflect the long-term loyalty of customers and examines how their detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies influences their attitudinal loyalty.

Emotions as Social Information Theory suggests that the emotional information of the expresser can influence the observer’s behavior through inferential and affective reaction paths (Van Kleef, 2009, 2010). The affective reaction path indicates that when service providers naturally display genuine emotions, customers imitate these, resulting in corresponding emotional experiences (Hofmann et al., 2024). Based on this, we posit that, in the context of live commerce, the positive emotions shown by anchors through deep acting behaviors will spread to customers in the live telecast (Meng et al., 2021), stimulating positive emotions and thereby increasing attitudinal loyalty. Conversely, when anchors adopt surface-acting behaviors, the possibility of emotional contagion decreases. (Meng et al., 2021), making it difficult to arouse customers’ positive emotions. Furthermore, based on the inferential path, we posit that, in the context of live commerce, when customers perceive the anchor’s words and actions as exaggerated, they believe that he/she is not sincerely serving customers and is merely completing their tasks without considering customers’ needs (Wang et al., 2022). Thus, they evaluate the anchor negatively, thereby reducing their attitudinal loyalty. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: The detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior by customers is positively correlated with customer attitude loyalty.

H1b: The detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior by customers is negatively correlated with customer attitude loyalty.

Customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy and perceived customer orientation

Based on the Emotion as Social Information Theory, this study demonstrates the impact of customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies on perceived customer orientation from two aspects. On the one hand, when anchors genuinely express positive emotions to customers, the latter consciously or unconsciously perceive this information (Qureshi et al., 2024), judging whether the anchor truly cares about their needs. This process is enhanced with an increase in the anchor’s emotional authenticity. At the same time, in the “one-to-many” service scenario, customers will evaluate how well the anchor meets the needs of other customers, and the positive emotional information obtained will enhance the perception of customer orientation in the entire live room. This phenomenon is consistent with the conclusion of both Groth and Grandey (2012) that customers act as emotional transmitters in service interactions. On the other hand, when anchors do not express authentic emotions, it may lead customers to question their ability to meet needs, and reduce the probability of “emotional contagion” (Groth et al., 2009), thereby lowering the perception of customer orientation. According to the inferential path of Emotion as Social Information Theory (Van Kleef, 2009, 2010), when customers capture inauthentic emotions, they process the anchor’s emotions as social information, interpreting the latter as merely completing company tasks and not sincerely serving customers. This phenomenon is similar to the findings of Cheshin (2018), who concluded that service personnel’s exaggerated emotions cause customers to view them as insincere. Based on these two aspects, this study posits that customers’ detection of anchors’ deep-acting behavior positively affects perceived customer orientation, whereas customers’ detection of anchors’ surface-acting behavior negatively affects perceived customer orientation. The hypotheses are as follows:

H2a: The detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior by customers is positively correlated with customer attitude loyalty.

H2b: The detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior by customers is negatively correlated with customer attitude loyalty.

Perceived customer orientation and customer attitude loyalty

Based on the above measurement of customer attitudinal loyalty, this study reviews existing research to demonstrate the relationship between perceived customer orientation and customer attitude loyalty. For example, Wang (2009) and Rajaobelina et al. (2022) found that positive emotions generated from positive interactions with service personnel significantly increase customers’ satisfaction and patronage intentions, thereby prompting them to be more willing to recommend, purchase, or continue to patronize. Smith (2012) found that customer-oriented employee attitudes and behaviors promote customer loyalty. Reviewing the above research, this study finds a positive correlation between perceived customer orientation and customer attitude loyalty in service interactions. Simultaneously, this study posits that this conclusion is equally applicable to the service context of live commerce; that is, when customers feel that their or others’ needs are cared for and satisfied by the anchor, their purchase and recommendation intentions will significantly increase. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Perceived customer orientation is positively correlated with customer attitude loyalty.

Perceived customer orientation as the mediator

Moreover, this study demonstrates the mediating role of perceived customer orientation through the affective reaction path of the EASI theory. The affective reaction path indicates that people usually consider the emotions of others in the same environment as clues to interpret the environment, using them as a basis for heuristic decision making. For example, people will regard an environment as pleasant and trustworthy if they feel highly positive emotions of others in the current environment, thereby increasing their willingness to cooperate (Van Kleef, 2009). Compared with the general situation proposed by this path, the live commerce context demonstrates more emotional infectiousness (Meng et al., 2021), and the role of the affective reaction path is more significant. Based on this, this study proposes that when customers perceive genuine and positive emotional information from an anchor, they generate positive emotions, regard the live room as friendly and trustworthy. Further, they believe that the anchor’s attitude towards customers is responsible, thereby increasing his/her perceived customer orientation and their purchase and recommendation intentions. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a: Perceived customer orientation mediates the impact of customer detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior on customer attitude loyalty.

H4b: Perceived customer orientation mediates the impact of customer detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior on customer attitude loyalty.

Customers’ emotional labor strategy detection accuracy as the moderator

Based on existing research, this study demonstrates the moderating role of customers’ emotional labor strategy detection accuracy. Liu et al. (2019) found that when customers fully perceive employees’ deep acting behavior, their trust in them increases. Furthermore, customer trust continues to increase when the perception of deep acting behavior exceeds the actual behavior of employees. In contrast, with surface acting behavior, customer trust levels first decrease and then increase as customers perceive more surface acting behavior, resulting in a U-shaped effect. Groth et al. (2009) confirmed that customers’ emotional detection accuracy can moderate the relationship between emotional labor strategies and perceived customer orientation. These studies explain the moderating role of emotional detection accuracy in general service situations and posit that the high frequency of emotional communication between anchors and customers in the live commerce context will make this effect more significant. Therefore, this study proposes that the higher the customers’ emotional detection accuracy, the stronger the positive correlation between their detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior and perceived customer orientation, and the stronger the negative correlation between their detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior and perceived customer orientation. Based on the literature discussed above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a: Customers’ detection accuracy of deep acting behavior can positively moderate the relationship between their detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior and perceived customer orientation. Specifically, the more accurately customers detect deep acting behavior, the stronger the positive relationship between their detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior and perceived customer orientation.

H5b: Customers’ detection accuracy of surface acting behavior can positively moderate the relationship between their detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior and perceived customer orientation. Specifically, the more accurately customers detect surface acting behavior, the stronger the negative relationship between their detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior and perceived customer orientation.

Additionally, based on existing research in the service field (Groth et al., 2009; Winkler et al., 2025; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2006; Gong et al., 2020), this study demonstrates the moderated mediating role of customers’ emotional labor strategy detection accuracy from two aspects. On the one hand, when customers can accurately receive an anchor’s emotional labor strategy, they will have a more accurate understanding of his/her emotional transmission and interaction methods, and they can more keenly capture the emotional signals conveyed (Winkler et al., 2025; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2006; Gong et al., 2020), more accurately understand the anchor’s customer-oriented behavior, and thus are more likely to increase their attitudinal loyalty. Thus, when customers’ emotional labor strategy detection accuracy is higher, the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies and customer attitude loyalty will be stronger. On the other hand, when customers’ detection accuracy is low, they may not be able to identify the anchor’s acting behavior (Groth et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2020), thereby affecting their detection of the anchor’s customer orientation and attitudinal loyalty. In this case, the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between customers’ detection of the anchors’ emotional labor strategies and perceived customer orientation will be relatively weak. Therefore, this study proposes that the accuracy of customers’ emotional labor strategy detection moderates the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies and customer attitude loyalty. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a: The detection accuracy of customers’ deep acting behavior affects the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between their detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior and their attitude loyalty, which is a moderated mediating effect.

H6b: The detection accuracy of customers’ surface acting behavior affects the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between their detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior and their attitude loyalty, which is a moderated mediating effect.

Based on the above assumptions, the model shown in Fig. 1 was constructed.

Research design

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire used in this study was a paired questionnaire divided into two parts: an anchor questionnaire and a customer questionnaire. The reason for the paired questionnaire was to explore whether there is a congruence between the anchors’ emotional labor strategy and customers’ detection of it. The anchor questionnaire consisted of two sections: the first section collected information on the anchor’s gender, live streaming platform, live streaming time, and product type in the live room, and the second section contained six questions filled out by the anchor regarding deep and surface acting behaviors in emotional labor strategies. The customer questionnaire was divided into three sections: the first section introduced the purpose and process of the study, explained the confidentiality and non-commercial nature of the research, and asked whether the respondents had experience watching live broadcasts and shopping through live streams; if the response was negative, there were no further questions, ensuring that all respondents had experience with live-stream shopping. The second section collected information about the respondents, including gender, age, income, occupation, average duration of watching live streams, interaction frequency during live broadcasts, and the main types of products or services purchased through live streams. The third section measured the main variables, where customers first watched a one to three-minute live stream recording of the anchor, and then filled out the questionnaire based on their true feelings after watching the video. This included three questions about the detection of the anchor’s deep acting behavior, three questions about the detection of the anchor’s surface acting behavior, five questions about perceived customer orientation, and four questions about customer attitude loyalty (purchase and recommendation intentions). Subsequently, the collected questionnaires were paired by matching one anchor with multiple customers to form a complete survey. Questionnaire design referred to mature domestic and international scales, which were scientifically validated through multiple rounds of translation between Chinese and English. Combined with the characteristics of this study, multiple rounds of optimization were conducted by means of localization adjustment and listening to the opinions of scholars and experts to ensure the accuracy of the questionnaire expression.

Data collection

The questionnaire survey was divided into two stages: pre-research and formal research. The pre-research was conducted from May 12 to May 22, 2023, targeting customers with experience in live-stream shopping, and included all the measurement items in this study. A combination of online and offline methods was used to distribute 153 questionnaires, which was more than five times the number of items (Hinkin, 1998). After data collection, 113 valid questionnaires were obtained after excluding respondents who had not watched or used live shopping, with a recovery rate of 73.8%. Through reliability and validity analyses using SPSS 24.0, the scales for deep and surface acting behavior detection, perceived customer orientation, and customer attitude loyalty were found to have high reliability and validity; thus, the questionnaire items were finally determined.

The formal research began on July 1, 2023, and continued until August 17, targeting e-commerce anchors engaged in live-streaming and customers with experience of live-stream shopping. Formal research combined offline visits and online invitations to recruit anchors. The researchers visited several companies in the field and conducted face-to-face communications and extended questionnaire invitations to the anchors of relevant MCN companies. We also cooperated with several companies through which the questionnaires were distributed to the anchors to ensure the diversity and breadth of the anchor sample. Each participating anchor was invited to provide a two to three-minute live video clip. After collecting 42 anchor questionnaires, the study paired and constructed 42 groups of customer questionnaires, with each group requiring participants to watch the corresponding anchor’s live-stream clip before responding, so that the evaluation was based on the actual live-stream content. Questionnaires were distributed through the Wenjuanxing platform, a widely used online survey tool that can efficiently distribute questionnaires to target customer groups and collect data. Each respondent was paid $1 to complete the questionnaire. Considering the reliability and quality of the data, the collection limit for each group of questionnaires was set at 20. After a series of promotions and invitations, the study collected 413 customer questionnaires, of which 82 were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) customers without live-stream shopping experience, (2) questionnaires with large areas of blank space, and (3) questionnaires with regular patterned answers (i.e., all questions selecting the same option), resulting in 331 valid customer questionnaires with an effective rate of 80.1%. The characteristics of the anchor sample and the customer sample were shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Variable measurement

This study used a 7-point Likert scale to measure the main variables, with 1 to 7 indicating “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”(Yadav et al., 2023). Compared with employees and consumers in general situations, anchors in live commerce situations have more emotional infectiousness, customers have more emotional detection (Meng et al., 2021), and it is relatively easier to generate emotional resonance between the two (Ling et al., 2024). Therefore, this study believes that the measurement methods for emotional labor strategies, emotional labor strategy detection, perceived customer orientation, customer attitude loyalty, and customers’ emotional labor strategy detection accuracy in general service situations are equally applicable to live commerce. Based on this, this study adopts the following measurement methods: (1) The measurement of emotional labor strategies mainly refers to Groth’s (2009) research, dividing emotional labor strategies into two dimensions: deep and surface acting behavior, and adjusting the wording according to the research background, forming three items for each, to be filled out by the anchor; (2) The measurement of emotional labor strategy detection also mainly refers to Groth’s (2009) research, dividing emotional labor strategies into two dimensions perceived by customers: deep and surface acting behavior, and adjusting the wording according to the research background, forming three items for each, to be filled out by the customer, to measure their detection of the anchor’s emotional labor strategy while watching the live broadcast; (3) The measurement of perceived customer orientation mainly refers to the studies of Brown (2002), Groth (2009) and Habel et al. (2020), adjusting the wording according to the research background, forming five items to be filled out by the customer; (4) Mainly referring to Gong (2020) and So et al. (2025), customer loyalty attitude was measured through purchase and recommendation intention, and combined with the context of the study to form two sub-dimensions of purchase and recommendation intention, totaling four items, to be filled out by the customer; (5) Customer emotional labor strategy detection accuracy mainly refers to the measurement and calculation method of Groth et al. (2009), and the specific process is as follows: after the anchor and customer questionnaires were filled out, the deviations between the anchor’s deep and surface playing behaviors and the video viewer’s detection were measured. These deviations were classified through the median division method to derive a median value. Based on that, the data were calibrated, and those that were higher than the median value were judged as having lower perceived accuracy (marked as 1), while those below the median were judged as higher (marked as 2). The residual effect of perceived accuracy in the product regression of acting behavior and viewer detection was calculated; the residuals mentioned above were used as a moderating variable to represent the detection accuracy of the deep and surface acting behaviors.

Empirical analysis and results

Reliability and validity analysis

The study initially employed SPSS 24.0, to conduct reliability and validity assessments on all latent variables; the results are presented in Table 3. The Cronbach’s α values and Composite Reliability (CR) values were all greater than 0.7, indicating good internal consistency and construct reliability within the sample. All item loadings were above 0.7, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.5, suggesting that the scales demonstrated good convergent validity. Subsequently, AMOS 24.0 was utilized to perform a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the model, comparing the baseline model with four-factor, three-factor, two-factor, and single-factor models, as shown in Table 4. Compared to the other models, the baseline model demonstrated a higher degree of fit, with the following overall measurement indices: χ²/df = 3.003, RMSEA = 0.078, NFI = 0.938, IFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.944, and CFI = 0.957. In summary, the results indicate that the questionnaire design and structural model of this study reached a satisfactory level.

Correlation analysis

The correlation between variables was measured using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and the results are shown in Table 5. No strong correlation was observed among the variables, and the correlation analysis results were in line with theoretical expectations, providing preliminary evidence for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Main effects and mediation effects testing

As demonstrated by the test results of Table 6, the detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior by customers has a significant positive impact on customer attitude loyalty (recommendation and purchase intention) (β = 0.172, p < 0.001; β = 0.147, p = 0.002). The detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior by customers does not have a negative impact and the positive impact on recommendation intention is not significant (β = 0.06, p = 0.129). The detection of anchors’ surface acting behavior by customers has a significant positive impact on purchase intention (β = 0.092, p = 0.025), so Hypothesis H1a is supported, while Hypothesis H1b is not supported.

This study employed a bootstrapping method to calculate the mediation effect by performing 5000 resampling iterations to enhance the reliability of the results. According to the test results shown in Table 6, perceived customer orientation played a significant mediating role between the detection of deep acting behavior and recommendation purchase intention (indirect effect values: 0.515 and 0.507; confidence intervals: 0.423~0.639 and 0.415~0.630, both not including 0), with both direct effects being significant (p = 0.002; p < 0.001). Therefore, perceived customer orientation partially mediates the impact of deep acting behavior detection on recommendation purchase intention, supporting Hypothesis H4a; perceived customer orientation played a significant mediating role between the detection of surface acting behavior and recommendation purchase intention (indirect effect values: 0.351 and 0.336; confidence intervals: 0.209~0.486 and 0.205~0.472, both excluding 0), with the former direct effect being insignificant (p = 0.129) and the latter direct effect being significant (p = 0.025). Therefore, perceived customer orientation fully mediates the impact of surface acting behavior detection on recommendation intention and partially mediates the impact of surface acting behavior detection on purchase intention, respectively, supporting Hypothesis H4b. The confidence intervals of the four paths of total and indirect effects are all greater than 0, hence deep and surface acting behavior detection positively affects perceived customer orientation which, in turn, positively affects customer attitude loyalty, supporting Hypotheses H2a and H3; H2b is not supported.

Moderation effects testing

As shown by the test results of Table 7, the interaction term coefficient between the detection of deep acting behavior and accuracy of customers’ detection of deep acting behavior is significantly positive (β = 0.100, p < 0.001), and the latter has a significant positive impact on perceived customer orientation (β = 0.688, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H5a. The interaction term coefficient between the detection of surface acting behavior and the accuracy of customers’ detection of surface acting behavior is significantly negative (β = −0.194, p < 0.001), and the detection of surface acting behavior has a significant positive impact on perceived customer orientation (β = 0.362, p < 0.001). Hypothesis H5b is not supported.

Moderated mediation effects testing

According to the test results shown in Table 8, the accuracy of customers’ detection of anchors’ deep acting behavior significantly moderated the mediating role of perceived customer orientation in the relationship between the detection of deep acting behavior and customer attitude loyalty (recommendation and purchase intention) (confidence intervals: 0.029~0.145 and 0.032~0.140, both not including 0). The moderation at a high degree of customers’ accuracy of detection of deep acting behavior was higher than at a lower degree(effect values: 0.671 > 0.496, 0.661 > 0.489), hence the accuracy of customers’ detection of deep acting behavior positively moderated the mediating role of perceived customer orientation in the relationship between the detection of deep acting behavior and customer attitude loyalty (recommendation and purchase intention), supporting Hypothesis H6a. The accuracy of customers’ detection of surface acting behavior significantly moderated the mediating role of perceived customer orientation in the relationship between the detection of surface acting behavior and customer attitude loyalty (recommendation and purchase intention) (confidence intervals: −0.337~−0.052 and −0.313~−0.048, both excluding 0). The moderation effect at a high degree of customers’ accuracy of detection of surface acting behavior was insignificant (confidence intervals: −0.052~0.366 and −0.053~0.354, both including 0), and at a low degree of customers’ accuracy of detection of surface acting behavior, it was significant (confidence intervals: 0.352~0.732 and 0.339~0.696, both excluding 0). Therefore, the accuracy of customers’ detection of surface acting behavior negatively moderated the mediating role of perceived customer orientation in the relationship between the detection of surface acting behavior and customer attitude loyalty (recommendation intention and purchase intention). This implies that the lower the accuracy of customers’ detection of surface acting behavior, the stronger the mediating role of perceived customer orientation in the relationship between the detection of surface acting behavior and customer attitude loyalty (recommendation and purchase intention), supporting Hypothesis H6b.

Discussion and implications

Based on the EASI theory, this study conducted an empirical analysis of the relationship between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies and customer attitude loyalty in the context of live commerce. The results show:

First, customers’ detection of the anchors’ emotional labor strategies positively affects their perceived customer orientation and loyalty. Specifically, regardless of whether customers perceive the anchors’ acting behaviors as deep or surface, they still believe that the latter serves them with sincerity and is genuinely customer-centric, enhancing their willingness to purchase as well as recommend the anchor’s products or services. This result is mostly inconsistent with previous research findings, which found that customers’ detection of surface acting behavior negatively affects perceived customer orientation and customer loyalty (Groth et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2020). The reasons for the discrepancy may be: (1) Different research contexts. Most previous studies were based on offline contexts (Groth et al., 2009; Gabriel et al., 2015; Grant et al., 2013), whereas this study was conducted in the context of live commerce. Chen et al.’s (2024) research found that this context cannot provide customers with direct tactile perception of products or services. Therefore, customers mainly focus on the auditory-visual information of the product or service in the live room to supplement the tactile information with associations (Chen et al., 2024). The emotional information of the anchor may not be the main factor influencing customers to make evaluations, although they can perceive it. (2) Different cultural backgrounds. Most previous research on emotional labor strategies has been conducted in Western cultures (Groth et al., 2009; Meng et al., 2021), whereas this study is based primarily on the Eastern cultural context. In China, service personnel often display exaggerated enthusiasm when facing customers; this kind of behavior is not insincere but is intended to provide a good consumer experience through enthusiasm (Grayson, 1998). Customers also understand this behavior, viewing it as an expression of service personnel’s warm emotions, thus positively evaluating the service personnel (Lin et al., 2011). Therefore, when an anchor meets basic service requirements, even though perceiving surface acting behavior, customers still understand and make positive evaluations and purchase recommendations. This finding is mostly consistent with Xu et al.’s (2020) explanation of the differences between Eastern and Western cultural contexts. (3) The entertainment of live commerce. Wang et al. (2024a) found that in live commerce, audiences often watch live broadcasts for entertainment and interaction, and are more likely to be attracted to anchors with rich emotional expressiveness. Anchors’ surface acting behavior is seen as a form of entertainment and is more easily accepted by the audience (Xu et al., 2020), leading to positive evaluations and purchase recommendations.

Second, perceived customer orientation plays a mediating role between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies and customer attitude loyalty. Specifically, customers judge whether the anchor is genuinely concerned about their needs and preferences by detecting his/her emotional labor strategies, which affect their willingness to purchase and recommend products or services. This result confirms the conclusion of Groth et al. (2009) that perceived customer orientation mediates the relationship between emotional labor strategies and customer loyalty intentions, which also holds true in the context of live commerce. Additionally, in the context of live commerce, Zhang et al. (2022a) and Wongkitrungrueng and Assarut (2020) found that seller-customer interaction and seller characteristics can cultivate online trust among customers, which further determines customer purchasing behavior. Based on the above research on the impact of anchors’ behavior characteristics on customer purchasing behavior, this study provides a beneficial supplement to the mechanism between anchors’ emotional characteristics and customers’ long-term loyalty in the context of live commerce.

Finally, customers’ emotional labor strategy detection accuracy moderates the effect of customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy on perceived customer orientation, as well as the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategy and customer attitude loyalty. Higher accuracy of deep acting behavior detection allows customers to perceive the anchor’s higher authenticity of emotions more genuinely, making it easier for them to perceive that the anchor is sincerely serving and considering customers (Gong et al., 2020), thereby increasing their willingness to purchase and recommend products or services. Lower accuracy makes it more difficult for customers to realize that the anchor is engaging in surface acting behavior, leading them to believe that the anchor is sincerely serving and considering customers (Gabriel et al., 2015), thereby increasing their willingness to purchase and recommend products or services. The moderating effect of the accuracy of deep acting behavior detection is mainly consistent with the findings of Gong et al. (2020) in the traditional service context, whereas that of surface acting behavior detection is inconsistent with the findings of Groth et al. (2009) and Gong et al. (2020). The reasons for the inconsistency are as follows: (1) The lack of tactile information of products or services in the context of live commerce makes customers focus more on product and service information rather than emotional information of anchors (Chen et al., 2024); (2) In the context of Chinese culture, when the anchor meets the basic service requirements, even though customers perceive the anchor’s surface acting behavior, they still show understanding (Xu et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2011); (3) The entertainment aspect of live commerce makes customers regard the surface acting behavior of anchors entertaining behavior (Wang et al., 2024a).

Theoretical implications

First, this study mainly enriches research on emotional interactions between anchors and customers in the context of live commerce (Li and Shao, 2024; Zhang et al., 2023). Existing studies have mostly analyzed the behavioral interaction between anchors and customers, but the mechanism behind the emotional interaction remains unclear (Chen et al., 2024). Based on this, our study includes customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies, explores the research mechanism of its impact on customer attitude loyalty, thereby supplementing existing interactive research literature in the field of live commerce.

Second, this study generally extends the application of the Emotions as Social Information Theory from the traditional service context to live commerce (Groth et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2017). According to Emotions as Social Information Theory, this study mainly investigates how the manner by which anchors convey emotional information in the context of live commerce affects customer attitude loyalty, which helps us better understand and apply this theory.

Finally, this study mainly introduces customer attitude loyalty as a result variable, innovatively applying the concept of long-term loyalty to research in the field of live commerce (Zhang et al., 2022a). In the context of live commerce, this study generally considers customer attitude loyalty to be long-term and verifies that it is a core element for the sustainable development of live commerce, enhancing our understanding of the process by which customers form long-term loyalty.

Practical implications

First, companies should encourage anchors to express their genuine emotions and attitudes. Based on statistical analysis, this study found that despite differences in emotional recognition abilities among individuals, most customers possess a keen ability to perceive the authenticity of anchors’ emotional labor strategies. Therefore, companies can emphasize psychological adjustment before, during, and after live broadcasting while training and guiding anchors to ensure that they present a real and positive emotional state to customers and attract them to watch the live broadcast for longer.

Second, companies should encourage anchors to match customer emotions. Compared with traditional service situations, customers’ emotions in the live commerce context are more likely to be inspired and driven. Therefore, in the live-broadcast process, companies can encourage anchors to match their emotions with those of customers, understand the emotional needs of customers, and tailor the emotional expression, which can strengthen their emotional connection with customers, thereby shaping their long-term loyalty.

Finally, companies should scientifically arrange the live broadcast process of anchors; after significant emotional labor, anchors are prone to emotional fatigue. Therefore, companies can scientifically and reasonably arrange the live broadcast process to ensure that anchors have sufficient rest time after high-intensity emotional output. It can help anchors constantly demonstrate a positive mental state, generate a good experience for customers, and cultivate their long-term loyalty.

Limitations and future research

The study demonstrates certain limitations. First, most studies on emotional labor strategies invite employees and customers to complete questionnaires immediately after the service is completed (Li et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2024b). However, this study is limited by reality and cannot collect customers’ information the first time after live shopping, so it is difficult to capture their immediate emotions and behaviors. Future studies can further supplement real-time information about customers watching live broadcasts to improve the timeliness of samples.

Second, this study analyzes the mechanism of customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies affecting customer attitude loyalty in the context of live commerce using questionnaire data. Currently, there is a large amount of real-time data in live commerce, such as user stay time, number of danmaku, and number of people sending danmaku (Zhang et al., 2024a). Therefore, future research can observe the anchor-customer interactions, collect data from a third-party perspective, and conduct research with secondary data and other methods to enrich the research results.

Finally, this study only considers the influence mechanism of customers’ detection of anchors’ emotional labor strategies on customer attitude loyalty. Future research can incorporate live broadcast scenes, product elements, and customer characteristics into the model as a way to improve the influence of the mechanism of customer attitude loyalty and provide more effective suggestions for companies to cultivate customers’ long-term loyalty.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available as a form of supplementary file and/or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bai X, Aw ECX, Tan GWH, Ooi KB (2024) Livestreaming as the next frontier of e-commerce: A bibliometric analysis and future research agenda. Electron Commer Res Appl 65:101390

Brown TJ, Mowen JC, Donovan DT et al. (2002) The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self-and supervisor performance ratings. J Mark Res 39(1):110–119

Chen A, Chen Y, Li R, Lu Y (2024) The interaction between the anchor and customers in live-streaming E-commerce. Ind Manag Data Syst 124(6):2151–2179

Cheshin A, Amit A, Van Kleef GA (2018) The interpersonal effects of emotion intensity in customer service: Perceived appropriateness and authenticity of attendants’ emotional displays shape customer trust and satisfaction. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 144:97–111

Chu Q, Zhang Z, Wu TJ, Zhang Z (2025) Interaction between online retail platforms’ private label brand introduction and manufacturers’ channel selection. J Retail Consum Serv 84:104208

CNNIC (2025) The 55th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. https://cnnic.cn/n4/2025/0117/c208-11228.html

Frennea CM, Mittal V (2017) Customer satisfaction, loyalty behaviors, and firm-financial performance: what 30 years of research tells us. Mark Lett 34(2):171–187

Gabriel AS, Daniels MA, Diefendorff JM, Greguras GJ (2015) Emotional labor actors: a latent profile analysis of emotional labor strategies. J Appl Psychol 100(3):863–879

Gong T, Park J, Hyun H (2020) Customer response toward employees’ emotional labor in service industry settings. J Retail Consum Serv 52:101899

Grandey AA (2000) Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 5(1):95

Grant AM (2013) Rocking the boat but keeping it steady: The role of emotion regulation in employee voice. Acad Manag J 56(6):1703–1723

Grayson K (1998) Customer responses to emotional labor in discrete and relational service exchange. Int J Serv Ind Manag 9(2):126–154

Groth M, Grandey A (2012) From bad to worse: Negative exchange spirals in employee–customer service interactions. Organ Psychol Rev 2(3):208–233

Groth M, Hennig-Thurau T, Walsh G (2009) Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Acad Manag J 52(5):958–974

Habel J, Kassemeier R, Alavi S et al. (2020) When do customers perceive customer centricity? The role of a firm’s and salespeople’s customer orientation. J Personal Sell Sales Manag 40(1):25–42

Hennig-Thurau T (2004) Customer orientation of service employees: Its impact on customer satisfaction, commitment, and retention. Int J Serv Ind Manag 15(5):460–478

Hennig-Thurau T, Groth M, Paul M, Gremler DD (2006) Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. J Mark 70(3):58–73

Hinkin TR (1998) A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ Res Methods 1(1):104–121

Hochschild AR (1983) The Managed Heart. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

Hofmann V, Stokburger-Sauer NE, Wetzels M (2024) The role of a smile in customer–employee interactions: Primitive emotional contagion and its boundary conditions. Psychol Mark 41:2181–2196

Itani OS, Gabler CB, Kalra A, Bakeshloo KA, Agnihotri R (2025) The interplay of morality, emotional labor, and customer injustice: How salesperson experiences shape job satisfaction. Ind Mark Manag 124:162–174

Li L, Chen X, Zhu P (2024) How do e-commerce anchors’ characteristics influence consumers’ impulse buying? An emotional contagion perspective. J Retail Consum Serv 76:103587

Li Q, Shao X (2024) The impact of anchor characteristics on customers’ sustainable follow in e-commerce live broadcast—based on the survey of TikTok users in China. Int J Bus Soc 25(1):354–367

Li Y, Li X, Cai J (2021) How attachment affects user stickiness on live streaming platforms: A socio-technical approach perspective. J Retail Consum Serv 60:102478

Lin JSC, Lin CY (2011) What makes service employees and customers smile: Antecedents and consequences of the employees’ affective delivery in the service encounter. J Serv Manag 22(2):183–201

Ling S, Zheng C, Cho D, Kim Y, Dong Q (2024) The Impact of Interpersonal Interaction on Purchase Intention in Livestreaming E-Commerce: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav Sci 14:320

Liu XY, Wang J, Zhao C (2019) An examination of the congruence and incongruence between employee actual and customer perceived emotional labor. Psychol Mark 36(9):863–874

Luo L, Xu M, Zheng Y (2024) Informative or affective? Exploring the effects of streamers’ topic types on user engagement in live streaming commerce. J Retail Consum Serv 79:103799

Marques GS, Correia A, Costa CM (2018) The influence of customer orientation on emotional labour and work outcomes: a study in the tourism industry. Eur J Tour Res 20:59–77

Meng LM, Duan S, Zhao Y, Lü K, Chen S (2021) The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming E-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. J Retail Consum Serv 63:102733

Mridha B, Sarkar B, Cárdenas-Barrón LE, Ramana GV, Yang L (2024) Is the advertisement policy for dual-channel profitable for retailing and consumer service of a retail management system under emissions-controlled flexible production system. J Retail Consum Serv 78:103662

Qureshi AW, Monk RL, Quinn S, Gannon B, McNally K, Heim D (2024) Catching a smile from individuals and crowds: evidence for distinct emotional contagion processes. J Personal Soc Psychol: Interpers Relat Group Process 127(1):132–152

Rajaobelina L, Brun I, Kilani N, Ricard L (2022) Examining emotions linked to live chat services: The role of e-service quality and impact on word of mouth. J Financ Serv Mark 27:232–249

Sarkar B, Kar S, Pal A (2024) Does the bullwhip effect really help a dual-channel retailing with a conditional home delivery policy. J Retail Consum Serv 78:103708

Shena H, Zhao C, Fan DXF, Buhalis D (2022) The effect of hotel livestreaming on viewers’ purchase intention: Exploring the role of parasocial interaction and emotional engagement. Int J Hosp Manag 107:103348

Shi Y, Ma C, Zhu Y (2021) The impact of emotional labor on user stickiness in the context of livestreaming service—evidence from China. Front Psychol 12:698510

Smith I (2012) ‘Meeting Customer Needs’, Routledge

So KKF, Yang Y, Li X (2025) Fifteen years of research on customer loyalty formation: A meta-analytic structural equation model. Cornell Hosp Q 66(2):253–272

Stuhldreier SM (2024) Unlocking (re)purchase potential through corporate responsiveness on social networks: The role of perceived customer orientation. J Retail Consum Serv 81:104041

Van Kleef GA (2009) How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (EASI) model. Curr Direct Psychol Sci 18(3):184–188

Van Kleef GA (2010) An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making: The emotions as social information model. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 42:1–62

Wang ES-T (2009) Displayed emotions to patronage intention: consumer response to contact personnel performance. Serv Ind J 29(3):317–329

Wang Q, Li X, Yan X, Li R (2024a) How to enhance consumers’ purchase intention in live commerce? An affordance perspective and the moderating role of age. Electron Commer Res Appl 67:101438

Wang Y, Lu Z, Cao P, Chu J, Wang H, Wattenhofer R (2022) How live streaming changes shopping decisions in E-commerce: A study of live streaming commerce. Comput Support Cooperative Work 31(4):701–729

Wang Z, Luo C, Luo XR, Xu X (2024b) Understanding the effect of group emotions on consumer instant order cancellation behavior in livestreaming E-commerce: Empirical evidence from TikTok. Decis Support Syst 179:114147

Wang Z, Singh SN, Li YJ et al. (2017) Effects of employees’ positive affective displays on customer loyalty intentions: An emotions-as-social-information perspective. Acad Manag J 60(1):109–129

Winkler AD, Pihan N, Zapf D, Kern M (2025) Serving with masks: a comparative analysis of flight attendants’ emotional labor between normal and COVID-19 times. Serv Bus 19(1):15

Wongkitrungrueng A, Assarut N (2020) The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers J Bus Res 117:543–556

Xu Y, Ye Y (2020) Who watches live streaming in China? Examining viewers’ behaviors, personality traits and motivations. Front Psychol 11:1607

Yadav N, Shankar R, Singh SP (2023) Customer satisfaction – dilemma of comparing multiple scale scores. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 34(1-2):32–56

Zhang M, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhao L (2022a) How to retain customers: Understanding the role of trust in live streaming commerce with a socio-technical perspective. Comput Hum Behav 127:107052

Zhang Y, Zhang D, Zhang Y, Xie Y, Xie B, Jiang H (2023) A comprehensive review of simulation software and experimental modeling on exploring marine collision analysis. ENG Trans 4:1–7

Zhang Y, Li K, Qian C, Li X, Yuan Q (2024a) How real-time interaction and sentiment influence online sales? Understanding the role of live streaming danmaku. J Retail Consum Serv 78:103793

Zhang Y, Zhang T, Yan X (2024b) Understanding impulse buying in short video live E-commerce: The perspective of consumer vulnerability and product type. J Retail Consum Serv 79:103853

Zhang Z, Zhang N, Wang J (2022b) The influencing factors on impulse buying behavior of consumers under the mode of hunger marketing in live commerce. Sustainability 14(4):2122

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Chinese Social Science Foundation (Grant number 21BGL116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.X.L. and W.T.J.; Methodology: P.X.L. and C.Y.H.; Formal analysis and investigation: C.Y.H. and L. F.Y.; Writing - original draft preparation: C.Y.H. and L.F.Y.; Writing - review and editing: P.X.L. and W.T.J.; Funding acquisition: P.X.L.; Resources: P.X.L.; Supervision: W.T.J. All authors have read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Huaqiao University on May 6, 2023 (Number: 20230202, May 6, 2023).

Informed consent

The researchers informed participants about the study’s objectives and overall nature both verbally and with written statements. Informed consent was obtained offline and online platform from every participant before they could access the survey. A questionnaire provided to the participants had a cover letter detailing the study’s purpose, procedures, confidentiality measures, and participant rights. The letter clearly stated that participation was voluntary and that all responses would remain confidential. Participants were also informed of their right to withdraw at any point. To ensure confidentiality, no personally identifiable information was collected in the survey. Informed consent was documented via a time-stamped entry in the survey log between May 12 to May 22, 2023.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pei, XL., Cai, YH., Lyu, FY. et al. How to cultivate loyal online customers: the role of emotional labor strategy detection in the context of live-commerce. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1935 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06224-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06224-6