Abstract

Although Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) offers transformative opportunities for higher education, its adoption by educators remains limited, primarily due to trust concerns. This systematic literature review aims to synthesise peer-reviewed research conducted between 2019 and August 2024 on the factors influencing educators’ trust in GenAI within higher education institutions. Using PRISMA 2020 guidelines, this study identified 37 articles at the intersection of trust factors, technology adoption, and GenAI impact in higher education from educators’ perspectives. Our analysis reveals that existing AI trust frameworks fail to capture the pedagogical and institutional dimensions specific to higher education contexts. We propose a new conceptual model focused on three dimensions affecting educators’ trust: (1) individual factors (demographics, pedagogical beliefs, sense of control, and emotional experience), (2) institutional strategies (leadership support, policies, and training support), and (3) the socio-ethical context of their interaction. Our findings reveal a significant gap in institutional leadership support, whereas professional development and training were the most frequently mentioned strategies. Pedagogical and socio-ethical considerations remain largely underexplored. The practical implications of this study emphasise the need for institutions to strengthen leadership engagement, align GenAI adoption strategies with educators’ values, and develop comprehensive training frameworks that address ethical and pedagogical concerns. This work contributes a multidimensional view of educators’ trust in GenAI and provides a foundation for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) continues to transform many industry sectors such as healthcare, finance, transportation, and its influence is now increasingly visible in everyday life. In education, AI has the potential to enhance teaching and learning, streamline administrative processes, and support decision-making (Bozkurt et al., 2024; Bhullar et al., 2024). However, the integration of AI in higher education has been relatively slow and cautious, especially among educators (Cukurova et al., 2023; Kizilcec, 2023). This caution exists due to various concerns regarding the complexity of AI systems (Castelvecchi, 2016), trust issues (Gillespie et al., 2023), and insufficient institutional support (Duah & McGivern, 2024; Gimpel et al., 2023). In this study, the term ‘educators’ refers to faculty members, instructors, lecturers, and research staff who engage in teaching activities.

The arrival of Generative AI (GenAI) has intensified research and institutional interest in AI adoption within higher education, generating a mix of reactions that combined enthusiasm about potential benefits with concerns over risks and challenges (Crompton & Burke, 2024; Kasneci et al., 2023). Although GenAI has the capability to augment rather than replace educators’ expertise (Wang et al., 2024), its integration into higher education is still in its early stages (Lee et al., 2024; Ogunleye et al., 2024), mainly because of educators’ perceived benefits and concerns about AI (Viberg et al., 2024). Trust is thus an important yet underexamined factor influencing whether and how educators decide to integrate it into their teaching practices. Nevertheless, ethical issues and uncertainties often undermine trust in this technology (Dabis & Csáki, 2024; Holmes & Porayska-Pomsta, 2023).

Existing research indicates that trust in technology is a dynamic multidimensional concept shaped by personal experiences, technical attributes, and institutional support structures (Kaplan et al., 2021; McKnight et al., 2011). In the context of AI, trust extends beyond interpersonal relationships to include human-AI interaction (Glikson & Woolley, 2020) and serves as a mechanism for dealing with uncertainty and complexity (Bach et al., 2022; Choung et al., 2022). For educators, trust reflects their willingness to rely on AI in ways that are consistent with their professional judgement, pedagogical values, and emotional comfort (Chiu et al., 2023; Crompton & Burke, 2024). The educational context specifically calls for investigations into how institutional policies, leadership approaches, and support structures mediate trust development, a research area that remains largely unexplored (Niedlich et al., 2021). Although many higher education institutions (HEIs) have begun developing policies and support structures to address GenAI (Dabis & Csáki, 2024; Yan et al., 2024), few have implemented comprehensive support systems or incentives to encourage educators’ adoption (Duah & McGivern, 2024; Kamoun et al., 2024; Luo, 2024). However, these efforts reveal a deeper challenge: existing theoretical frameworks for understanding AI trust formation fail to capture the unique dynamics of higher education contexts.

Current trust in AI frameworks (Kaplan et al., 2021; Qin et al., 2020; Li et al., 2024; Yang & Wibowo, 2022; Lukyanenko et al., 2022) conceptualise the multidimensionality of trust in AI in terms of human, technical, and contextual factors but do not sufficiently explain how educators’ pedagogical orientations and institutional strategies interact in higher education (Nazaretsky et al., 2022). With the exception of Lukyanenko et al. (2022), most also neglect ethics as a distinct factor. Moreover, GenAI’s unique ability to generate human-like content raises novel issues of bias, academic integrity, and accountability that models do not fully address (Reinhardt, 2023; Wang et al., 2024).

These research gaps, combined with the absence of systematic studies examining educators’ trust in GenAI adoption, underscore the timeliness and importance of our investigation. Therefore, this study aims to examine how factors from broader AI trust frameworks apply within the distinctive context of GenAI in higher education through the introduction of a new conceptual model. Our model makes three key theoretical contributions: (1) integrating pedagogical elements as educator-specific trust factors, (2) positioning institutional strategies as foundational drivers, and (3) elevating socio-ethical concerns as a distinct analytical dimension. By incorporating these overlooked dimensions, the model captures the interplay between individual, institutional, and socio-ethical factors, offering a more comprehensive lens for analysing educators’ trust in GenAI. As a result, this research contributes a conceptual model of trust in GenAI tailored to higher education, bridging theoretical gaps in existing AI trust frameworks, and providing a foundation for future empirical validation.

Guided by this model, this systematic review aims to address the following research question: What are the factors and institutional strategies influencing educators’ trust in adopting GenAI for educational purposes? To answer this question, the following two specific sub-questions are explored:

-

RQ1. What are the trust factors influencing educators’ GenAI adoption for educational purposes?

-

RQ2. How do institutional strategies, including leadership support, policies, and training, interact with the educators’ trust factors in adopting GenAI in higher education?

The remainder of this paper reviews the literature on trust in AI and education before presenting our proposed conceptual model and systematic review methodology. We then report results addressing our research questions, discuss key findings with their theoretical and practical implications, and conclude by acknowledging study limitations and proposing recommendations for future research.

Literature review

The landscape of trust in AI research draws from diverse academic disciplines, including trust theory, technology acceptance, organisational systems, and educational psychology. Across these areas, scholars widely recognise that trust plays an important role in the acceptance and adoption of technology in real life (Afroogh et al., 2024; Kelly et al., 2023).

Trust in AI

To account for trust as a dynamic multidimensional concept, we use a system-based definition for trust in AI as “a human mental and physiological process that considers the properties of a specific AI-based system, a class of such systems or other systems in which it is embedded or with which it interacts, to control the extent and parameters of the interaction with these systems” (Lukyanenko et al., 2022, p. 12). We adopt this definition since it suggests that trust is a psychological mechanism that helps individuals manage uncertainty and optimise their interactions with AI systems (Lockey et al., 2021). At the institutional level, trust emerges through policies and support structures, which act as assurance mechanisms to manage uncertainty and risk (Mayer et al., 1995; McKnight et al., 2011). For instance, McKnight et al. (2011, p. 8) define structural assurances as “guarantees, contracts, support of other safeguards that exist in the general type of technology that make success likely” as a component of the “institution-based trust in technology”. In this paper, institutional strategies refer to leadership support, policies, guidelines, and professional support to represent the structural assurances for the institution-based trust in GenAI technology. At the individual level, educators’ trust in adopting GenAI for teaching is mediated by these institutional strategies while being shaped by personal experiences and professional judgement (Niedlich et al., 2021; Ofosu-Ampong, 2024). Additionally, trust is a dynamic concept that evolves gradually and changes with interactive experiences (Mayer et al., 1995). Latest research highlights the need to examine trust in AI across two dimensions: cognitive trust and emotional trust (Glikson & Woolley, 2020). Cognitive trust is based on the logical evaluation of AI functions. On the other hand, emotional trust encompasses the affective component of trust, which includes feelings of safety, ease of use, and confidence in technology (Yang & Wibowo, 2022). From the perspective of GenAI in education, we suggest that cognitive trust is built by the analysis of the system’s output and its accuracy with regard to pedagogical practices. In addition, the ease with which educators integrate GenAI into traditional teaching practices and the level of psychological safety they feel when trying out new GenAI tools indicate their emotional trust. Thus, emotional trust is developed over time through positive experiences within supportive institutional environments that address and respond to educators’ concerns.

Previous systematic reviews

Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses on trust in AI were conducted before the launch of GenAI in November 2022. For instance, Kaplan et al.‘s (2021) meta-analysis of 65 empirical studies, with a revised version in 2023, introduced a tri-dimensional framework categorising trust factors into human (trustor), AI technology (trustee), and contextual categories, but largely overlooked institutional influences. In line with this, Bach et al.‘s (2022) review suggested the need to integrate ethical aspects into technical and individual characteristics. Afroogh et al. (2024) conceptualised trust in the current AI literature and investigated its impact on technology acceptance across various domains. However, none of these studies discussed building trust within the education domain. In the higher education context, Herdiani et al. (2024) conducted a focused narrative review on the technical, ethical, and societal factors that influence trust in AI-based educational systems without addressing specific GenAI issues. Also, Jameson et al. (2023) analysed the institutional dimension, examining trust issues among different categories of educators and staff members in higher education. Although their review did not directly address trust in GenAI, it reviewed how institutional roles and relationships affect trust formation in academic contexts.

To effectively explore how trust influences the adoption of AI in education, previous research has incorporated trust as a central element within technology adoption frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Choung et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2011). For example, Wu et al.’s (2011) meta-analysis explored the impact of trust on TAM utilitarian constructs such as perceived usefulness in the e-commerce context. The results showed that various individuals (trustors) and context types affect the level of trust in the use of new technology, and therefore, educational contexts need dedicated investigations. A recent review from Kelly et al. (2023) identified TAM as the most used framework by researchers across different fields, including education. In contrast, Scherer et al.‘s (2019) meta-analysis on TAM in educational contexts examined contradictory findings surrounding educators’ intentions to use technology.

Moreover, Celik (2023) and Choi et al. (2023) have pointed out that these models fail to capture the nuances of AI adoption in education because of limited pedagogical and ethical awareness. Thus, two pedagogical frameworks that have been considered to address these shortcomings include pedagogical beliefs (Pajares, 1992) and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) (Mishra & Koehler, 2006). In this regard, studies by Liu (2011) and Cambra-Fierro et al. (2024) have shown that educators’ constructivist beliefs enabled them to integrate AI and GenAI successfully. The TPACK framework identifies the different knowledge areas that educators need for the effective integration of digital technology into teaching and learning, and it has been found useful in explaining how educators view GenAI as compatible with their pedagogical approaches (Celik, 2023; Mishra et al., 2024).

Despite these valuable contributions, there is a lack of systematic understanding of how educators’ trust in GenAI develops within the unique pedagogical, ethical, and institutional contexts of higher education, highlighting the need for a focused, systematic literature review investigation.

Trust in GenAI: proposed conceptual model for analysis

This section presents our proposed conceptual model serving as the analytical framework guiding our systematic review methodology.

As mentioned before, several existing theoretical frameworks examine the concept of trust in AI from a multidimensional perspective across different domains. The “foundational trust framework” of Lukyanenko et al. (2022) explains how organisational assurances are important in building trust from a systems theory perspective. Kaplan et al. (2021) and Li et al. (2024) provide a tri-dimensional (trustor, trustee, context-related) framework, which Yang & Wibowo (2022) further develop to include organisational and social factors. Regarding educational systems, Qin et al. (2020) developed a tri-dimensional trust model which consisted of technological elements (such as system functionality), contextual factors (for example, the “benevolence of educational organisations” (p. 1702), and personal factors (such as familiarity and pedagogical beliefs) as key elements for building trust in educational AI systems.

Despite these contributions, existing frameworks exhibit three critical limitations in understanding GenAI trust in higher education: insufficient attention to pedagogical factors unique to educators, a limited examination of institutional strategies, and a failure to address GenAI-specific ethical concerns. Our proposed model builds on these frameworks while addressing these gaps, considering a tri-dimensional structure comprising Trustor/Educator, Socio-Ethical Context, and Trustee (GenAI technology), with Institutional Strategies underpinning these dimensions as enabling conditions (see Fig. 1). Although traditional trust models include trustee (technology) characteristics such as system competence and transparency (Glikson & Woolley, 2020; Gulati et al., 2017), our research questions focus specifically on trustor (educator) factors and institutional strategies. For this reason, the Trustee (GenAI technology) factors are considered outside the scope of this study.

This structure directly addresses our research questions by identifying the factors influencing educators’ trust in GenAI adoption (RQ1) and examining how institutional strategies interact with these factors (RQ2). Together, these dimensions highlight how individual orientations, socio-ethical considerations, and institutional factors intersect in building educators’ trust in using GenAI in their practice.

Institutional Strategies, including leadership support, policies and guidelines, and professional support, are introduced as a foundational component that provides the “structural assurances” for the trust in GenAI factors following McKnight et al.’s (2011) framework. This component aligns with the “foundational trust framework” by Lukyanenko et al. (2022) for exploring how institutional systems interact with other AI systems.

The Trustor (Educator) category builds on the frameworks proposed by Li et al. (2024) and Yang & Wibowo (2022), incorporating the following elements: cognitive trust characteristics (including familiarity, self-efficacy, and sense of control), emotional trust characteristics (such as positive/negative emotional experience and hedonic motivation), and psychological characteristics such as trust propensity. Both Li et al. (2024) and Yang & Wibowo (2022) studies included demographics, familiarity, sense of control, emotional experience, hedonic motivation, and trust propensity as ‘trustor’ factors. We extended this category by integrating pedagogical belief factors (Qin et al., 2020) and pedagogical knowledge represented by the TPACK framework (Mishra et al., 2024) since these are educator-specific factors overlooked by existing frameworks.

The Socio-Ethical Context category is based on the context-related and social factors suggested by Yang & Wibowo’s (2022) framework. For this study, we focus on utilitarian features, such as perceived ease of use and usefulness, and social influence factors, which are recognised as the primary drivers of AI adoption when using the TAM and UTAUT models (Kelly et al., 2023). In educational settings, these features are understood as the ways in which GenAI’s perceived capabilities bring value to educators’ teaching practices. The social influence factors refer to how colleagues, industrial leaders, and professional networks influence an educator’s decision to use GenAI. Noting that trust in GenAI adoption presents nuances that cannot be explained only by utilitarian and social factors, we include ethical use factors (Bach et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2024). In this study, these factors refer to educators’ ethical concerns related to academic integrity, plagiarism, and bias in GenAI-generated content (Bozkurt et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024).

Conceptual framework comparisons

To clarify the distinct contribution of our study, Table 1 compares established trust frameworks with our model. This structured overview demonstrates how our proposed model addresses gaps and advances the field by embedding pedagogical orientations and institutional strategies that prior frameworks overlooked.

These framework differences have practical consequences for institutional GenAI adoption strategies. While traditional models might suggest focusing primarily on system usability and individual training, our framework predicts that institutional leadership engagement and pedagogical alignment are equally critical for trust development.

Methodology

The systematic review methodology used in this study follows the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021) and a structured, systematic approach based on best practices recommended by Alexander (2020), Gough et al. (2017), and Punch & Oancea (2014). This approach includes five main stages: searching, screening, organising, analysing, and reporting. The PRISMA workflow diagram displays the searching and screening stages (see Fig. 2).

Searching

We conducted electronic searches across five major academic databases that cover multidisciplinary sources relevant to educational research: ERIC, EBSCOhost, Web of Science (WoS), ProQuest, and Scopus, using the following Boolean electronic search query: (“generative AI” OR “artificial intelligence” OR ChatGPT OR “large language models”) AND (“higher education” OR university) AND (trust OR trustworthy). These database searches, executed between July 28 and August 4, 2024, initially retrieved 1380 articles.

Only peer-reviewed journal articles were considered to ensure high confidence in the quality of the studies selected (Gough et al., 2017). Filters for language, publication year (2019-2024), and document type were applied for each database, reducing the results to 447 articles. All searches maintain the same conceptual structure while adapting to database-specific syntax requirements. For example, this query syntax with filters from the Scopus database retrieved 45 articles: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Generative AI” OR “Generative Artificial Intelligence” OR “ChatGPT” OR “Large Language Models” OR LLM) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (trust OR trustworthy) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Higher Education” OR university) AND PUBYEAR AFT 2019 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)). A list of search queries and strategies for each database is provided in Appendix A.

In addition to the electronic database search, a manual search was performed using Google Scholar to locate specific articles through “referential backtracking, researcher checking, and journal scouring or hand searching” (Alexander, 2020, p. 14). This step helped capture the latest research in this rapidly evolving field, yielding 77 relevant journal articles. All search results were exported from each database in RIS format, imported into Zotero and then exported to an Excel file to remove duplicate articles, resulting in 444 articles for further screening.

Screening

At this stage, the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2) were applied consistently to ensure alignment with our objectives and research questions. The screening stage was conducted in several steps and involved a collaborative and iterative process that included all authors. At every step, meetings were held to review and discuss decisions, ensuring consistency and alignment with the research questions. The four screening steps included (1) title and abstract screening, (2) eligibility assessment, (3) full-text screening, and (4) quality appraisal.

First, the title and abstract screening step involved an initial screening done by the first author by reviewing titles and abstracts and classifying them into three groups: include, exclude, and to be reviewed. This step identified studies to be further screened for eligibility, which resulted in 266 articles being excluded due to missing keywords in the title and abstract. Second, for the eligibility assessment step, two independent researchers assessed the eligibility of the remaining articles (n = 178). A scoring mechanism was used to evaluate the quality and relevance of each article. A score of ‘1’ indicated high relevance, signifying a clear focus on trust or adoption for GenAI and higher education, and a score of ‘2’ indicated moderate relevance. Using this scoring system, the research team participated in two rounds of consensus-building discussions to resolve any disagreements. The inter-rater reliability was calculated using both percentage agreement and the chance-corrected reliability using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. This resulted in a 92% agreement rate and substantial agreement beyond change of κ = 77 (Belur et al., 2021).

Third, the full-text screening step involved a third researcher examining the full-text articles with conflicting eligibility assessments (n = 44). This step involved a meticulous review to resolve disagreements, and 37 articles achieved 100% agreement. An example of an ambiguous case was Karkoulian et al. (2024), which examined faculty and student perceptions of ChatGPT and academic integrity. One researcher questioned its inclusion since the focus was on ethics rather than trust, but after discussion with the 3rd researcher, the team agreed to include it, recognising that integrity concerns are important to educators’ trust formation in GenAI.

Finally, for the quality appraisal step, the selected articles were examined using Gough et al.’s (2017) quality standards. The criteria used for this study included four key elements: a clear study objective or research question, a description of the methodology for empirical studies, results, discussion, concluding remarks, and limitations. Each criterion was associated with a score of (1 = yes; 0 = no), and the quality score for each publication was calculated by dividing the study’s score by 4 (maximum score). All 37 articles met the quality appraisal evaluation with a score higher than 0.75 and were included in the review. Only two conceptual papers (Crawford et al., 2023; Hall, 2024) lacked a dedicated methodology section, which lowered their appraisal scores. However, they were included because they offered critical ethical, pedagogical, and socio-political perspectives that directly informed debates on trust in AI in higher education.

Analysis

To analyse the final set of 37 included documents, we used a deductive approach based on the proposed conceptual model described above (Cruzes & Dyba, 2011). The coding scheme (see Appendix C) included operational definitions for all model elements, which are also provided in the description column of the results tables in the next section. The software programme ATLAS.ti v. 25 (available at www.atlasti.com) was used to organise the documents and the corresponding coding scheme needed for the deductive analysis (Paulus et al., 2017). Recent systematic reviews in education have also emphasised structured methodological designs and theory-driven coding. For example, Abuhassna et al. (2024) and Alhammad et al. (2024) demonstrate how the integration of theory and the use of transparent procedures enhance the robustness of SLRs, which informed our own review design and analysis.

Results

This section reports the systematic review findings. It begins with a descriptive overview of the selected studies, followed by a discussion of the findings for each research question.

Descriptive characteristics of included studies

The explosive growth of GenAI research in higher education is evident in our sample of 37 papers, with 73% (n = 27) published within the eight months leading up to August 2024. This surge in research output reflects the urgent need for understanding GenAI integration in higher education, as confirmed by previous studies (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2024; Ogunleye et al., 2024). These studies were published in over 19 countries, with China and India ahead of the USA, Germany, and the UK. The emergence of multinational collaborations (19% of studies) shows an encouraging trend toward collaborative research in this area requiring global perspectives (Ivanova et al., 2024). Furthermore, five journals were found with more than two relevant articles (see Appendix B), including Education and Information Technologies, International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education (n = 3, 8%), and Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, TechTrends, and Education Sciences (n = 2, 5%).

Compared with earlier systematic reviews that focused largely on Western or technical contexts (Kaplan et al., 2021; Yang & Wibowo, 2022), our dataset shows that trust in GenAI is now being examined through diverse methodological lenses across underrepresented regions such as the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America.

Our methodological analysis revealed that despite the importance of understanding educators’ trust in GenAI adoption, no comprehensive literature review has addressed this specific angle. Of the 37 articles analysed, the majority (n = 24, 65%) were empirical studies, including quantitative (n = 14, 38%), qualitative (n = 6, 16%) and mixed-method approaches (n = 4, 10%).

As shown in Fig. 3, the empirical studies’ temporal distribution reveals an increase in the qualitative and mixed-method studies in 2024, addressing the call of several researchers (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2024; Kizilcek, 2023) asking for more qualitative GenAI studies focused on educators and HEIs. The population numbers for these studies range from smaller numbers of less than 50 participants (Espartinez, 2024; Karkoulian et al., 2024) towards studies engaging 150 or more educators (Brandhofer & Tengler, 2024; Chan & Lee, 2023; Kamoun et al., 2024). This combination of deeper qualitative insights and broader quantitative reach suggests the increasing level of enquiry related to GenAI adoption in education. At the same time, clear regional and methodological patterns are visible with studies from India, Oman, and China predominantly using quantitative survey-based approaches, whereas research from Europe and the UK more often relied on qualitative or mixed-method designs (see Appendix B).

Trust factors influencing educators’ GenAI adoption for educational purposes (RQ1)

Our analysis reveals a complex web of trust factors beyond simple technological acceptance. Based on our conceptual model, these factors cluster into two main categories: individual trustor/educator characteristics (see Table 3) and socio-ethical context factors (see Table 4).

Trustor (Educator) factors

Our findings indicate that trust in AI and GenAI varies significantly across demographic factors such as age, gender, and teaching experience, with contradictory results. While Kaplan et al. (2021) found that male users are more likely to trust AI than female users, Cabero-Almenara et al. (2024) reported contrasting results, suggesting that gender is not a decisive factor for educators’ AI acceptance. Regarding age, it has been found that younger people are more likely to trust GenAI than older groups (Chan & Lee, 2023; Jain & Raghuram, 2024), and with respect to teaching experience, Brandhofer & Tengler (2024, p.1110) revealed that the group least inclined to integrate AI are “teachers with between 30 and 39 years of teaching experience, followed by those with 0–9 years”. Our analysis indicates that additional research is needed to help educators and policymakers prioritise tailored training programmes to mitigate demographic trust issues (Jain & Raghuram, 2024; Ofosu-Ampong, 2024; Yusuf et al., 2024).

Based on these demographic patterns, our study found several studies suggesting that familiarity with GenAI (n = 9, 24%) and self-efficacy factors (n = 7, 19%) connect demographic characteristics and actual use and trust formation. For example, Brandhofer & Tengler (2024) and Chan & Lee (2023) discovered that familiarity is linked with teaching experience and generational differences. Likewise, research showed that individuals with higher self-efficacy in using GenAI tend to trust the technology and adopt it for their teaching practices (Bhaskar & Rana, 2024; Bhat et al., 2024), backing up previous research in this area (Nazaretsky et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021).

Findings from several studies (Cambra-Fierro et al., 2024; Hyun Baek & Kim, 2023; Salah, 2024) suggest that the success of GenAI integration depends less on the technology itself and more on the educator’s perceived sense of control, mainly through human-in-the-loop approaches. For example, Salah’s (2024) empirical study revealed that feeling in control of GenAI has a big impact on both trust development and psychological well-being, particularly for individuals experiencing job anxiety. Supporting these findings, Yan et al.‘s (2024) systematic review indicated that the limited involvement of educators in GenAI development made them feel that they had less sense of control, hindering trust formation.

Although familiarity, self-efficacy and sense of control show the cognitive aspect of trust, our analysis looked at twenty-two (n = 22, 59.5%) studies (emotional experience, n = 7; hedonic motivation, n = 6; and trust propensity, n = 8) that explored how emotional and psychological factors affect educators’ decisions to adopt and trust GenAI. A comprehensive sentiment analysis of 3559 educators’ social media comments by Mamo et al. (2024) found that 40% expressed positive emotional responses toward ChatGPT, with trust and joy emerging as the main sentiments. These results align with studies on emotional factors in technology adoption (Fütterer et al., 2023; Ghimire et al., 2024), which have shown that feelings of safety, ease, and confidence play a crucial role in establishing trust. Also, hedonic motivation, a UTAUT construct referring to the perception of GenAI as enjoyable and engaging, is positively correlated with educators’ adoption (Bhat et al., 2024; Kelly et al., 2023). Furthermore, our findings show that trust propensity, a key psychological factor, differs among educators, with tech-savvy individuals and those with positive prior experiences showing a higher propensity to trust (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2024; Wölfel et al., 2023). In their study, Wölfel et al. (2023) proved the importance of using teaching-specific data, like lecture materials, to create custom GenAI agents that can be trusted. These findings suggest that institutions can cultivate trust in GenAI by developing training programmes that not only teach technical skills but also create positive emotional experiences with the technology.

Our proposed conceptual model included pedagogical beliefs and pedagogical knowledge factors based on the adoption models proposed by Celik (2023) and Choi et al. (2023). In their empirical studies, Choi et al. (2023) and Cabero-Almenara et al. (2024) established that educators with constructivist teaching philosophies are more likely to integrate AI into their teaching practice. This suggests that constructivist educators may see GenAI as a tool that supports active learning and collaboration for students (Bozkurt et al., 2024). Also, Cabero-Almenara et al. (2024) pointed out that the difference between educators with constructivist and transmissive beliefs could be explained by their different expectations of how GenAI would impact or affect their roles. Although Jain & Raghuram (2024) confirmed that educators’ technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge (TPACK) significantly influences their trust in GenAI, our analysis suggests that traditional TPACK competencies may not be enough. Instead, as Mishra et al. (2024, p. 207) argue, GenAI requires educators to develop “new mindsets and contextual knowledge” that transcend traditional TPACK frameworks. Therefore, trust in GenAI requires an extension of existing pedagogical expertise to include AI literacy, defined as the need to develop the knowledge and skills to use GenAI responsibly and effectively in their teaching practices, including understanding the principles and ethics surrounding the use of AI (Long & Magerko, 2020; Yang et al., 2025).

Socio-Ethical Context factors

While individual characteristics and pedagogical factors create the foundation for trust, this review analysed three key socio-ethical context factors (Table 4).

Drawing from ten studies (n = 10, 27%), our analysis reveals that the TAM/UTAUT utilitarian factors can either amplify or diminish the impact of individual trust factors. For instance, Brandhofer & Tengler (2024) and Jain & Raghuram (2024) found that perceived usefulness was more likely to be associated with increased trust when aligned with educators’ existing pedagogical beliefs and sense of control. Additionally, the interaction between individual and utilitarian factors becomes even more evident when considering social influence, identified in eight studies (n = 8, 21.6%). Studies on GenAI adoption in higher education (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2024; Ofosu-Ampong, 2024) indicate that peer influence and institutional policies play a more significant role compared to traditional educational technologies. This means that the experiential knowledge of trusted colleagues serves as evidence for managing GenAI challenges and concerns in actual classroom settings. The empirical results from (Bhaskar et al., 2024; Bhat et al., 2024; Camilleri, 2024) confirm this finding and reinforce the emphasis on social influence factors in existing AI trust frameworks (Yang & Wibowo, 2022).

Finally, our analysis revealed unprecedented scrutiny regarding the ethical use of GenAI in HEIs, driven by educators’ concerns (Bhaskar & Rana, 2024; Yusuf et al., 2024). These ethical concerns emerge as fundamental barriers to trust that cannot be resolved by social influence or ease of use alone. Yusuf et al. (2024) emphasise the need for educational strategies and ethical guidelines to accommodate cultural diversity, while Bhaskar & Rana (2024) highlight educators’ responsibility to prevent AI misuse in academic settings.

Institutional strategies influencing educators’ trust in adopting GenAI (RQ2)

Our analysis of institutional strategies (see Table 5) reveals that meaningful leadership engagement remains absent despite widespread policy development and training initiatives.

Leadership support, including transparent communication and active involvement in GenAI-driven projects, was identified in only four (n = 4, 10%) out of 37 studies. This signals a fundamental weakness in current implementation approaches (Chan, 2023; Ofosu-Ampong, 2024) that undermines the factors identified in RQ1. For instance, Chan (2023) stressed that “senior management will be the initiator […] developing and enforcing policies, guidelines, and procedures that address the ethical concerns surrounding AI use in education” (p. 21). However, studies suggest this leadership role often remains conceptual rather than enacted, leaving educators uncertain about institutional support for GenAI adoption. Moreover, emotional and psychological factors, as well as pedagogical beliefs, require institutional validation through active leadership support (Crawford et al., 2023; Espartinez, 2024).

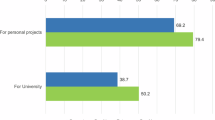

Despite the leadership gap, institutions are making substantial efforts in policy development. Several institutional policies and guidelines have emerged as a primary trust-building mechanism (Aler Tubella et al., 2024; Bannister et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). For example, Bannister et al. (2024) reported that “clear institutional policies and guidelines enhance trust by addressing educators’ ethical concerns, such as fears about bias and inequality in student evaluations and grading” (p. 14). Additionally, Aler Tubella et al. (2024) provided practical recommendations for both educators and policymakers on implementing AI trust principles. However, our findings from twelve studies (n = 12, 32%) reveal a collective call for HEIs to provide clear policies and guidelines to help educators cope with the GenAI rapid developments (Chan, 2023; Duah & McGivern, 2024). Furthermore, traditional institutional structures, characterised by slow-moving policy development processes, struggle to keep pace with technological changes, creating a disconnect between policy frameworks and practical needs, potentially undermining trust (Luo, 2024; Xiao et al., 2023). Therefore, a gradual implementation approach should be considered (Kurtz et al., 2024). While policies provide a foundation, our analysis reveals that educators require professional support and training to effectively integrate GenAI into their teaching (Kamoun et al., 2024; Kurtz et al., 2024), with seventeen selected studies (n = 17, 45%) reflecting this need. However, empirical evidence suggests an important implementation gap. For instance, Kamoun et al. (2024) found that “63.4% of surveyed faculty reported that they lack the requisite training and resources to integrate ChatGPT into their pedagogical practices” (p. 9). This difference between recognised need and actual implementation suggests that institutions should address educators’ AI literacy and pedagogical issues, such as authentic digital assessments (Lelescu & Kabiraj, 2024). Additionally, educators need to be proactive in finding GenAI training opportunities that align with their pedagogical goals (Chan, 2023). Nevertheless, our findings indicate that well-designed training programmes can positively influence educators’ trust factors, although future interdisciplinary research is needed to understand their effectiveness (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2024; Mamo et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024).

To complement the tabular data, Fig. 4 presents a heatmap-style treemap illustrating the frequency of trust factors across the three dimensions of our conceptual model.

The visualisation highlights professional support and training (n = 17) and policies and guidelines (n = 12 emerged most frequently, whereas leadership support had the lowest mentions. The trustor (educator) factors show a balanced distribution with a total of 10 studies related to pedagogical aspects. Socio-ethical concerns remain prominent, with utilitarian value (n = 10), social influence (n = 8), and ethical use (n = 6) showing their relevance to educators’ trust formation.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify the factors and institutional strategies influencing educators’ trust in adopting GenAI for educational purposes. Our analysis of 37 studies from 19 countries reveals multiple interactions between individual trust factors and institutional approaches that extend beyond conventional technology acceptance models, challenging how we conceptualise GenAI integration in higher education.

Summary of key findings

Our investigation reveals that educators’ trust in GenAI emerges from an interconnected dynamic system that includes individual characteristics, pedagogical values, socio-ethical contexts, and institutional strategies. Unlike previous research, our findings, which focused on higher education educators, demonstrate that trust formation is context-dependent and pedagogically mediated. This study managed to demonstrate that trust in GenAI involves a complex socio-technical system requiring ongoing interactions between human values, institutional structures, and technological capabilities.

Addressing our first research sub-question (RQ1) on the trust factors influencing educators’ adoption of GenAI, four categories are used to describe the individual trust factors. Demographic factors show contradictory patterns across studies, with inconsistent findings regarding gender influences (Cabero-Almenara et al., 2024; Kaplan et al., 2021) and complex relationships between teaching experience and trust (Brandhofer & Tengler, 2024). These contradictions suggest that demographic factors operate differently across institutional and cultural contexts, highlighting the need for context-specific approaches rather than broad demographic generalisations. Specifically, institutional context variations may play a significant role, as studies from institutions with strong AI support policies, such as those examined by Chan (2023) and Kurtz et al. (2024), showed weaker demographic effects compared to studies conducted in less supportive environments. Also, disciplinary differences matter considerably, with STEM-focused studies (Jain & Raghuram, 2024) exhibiting different demographic patterns than studies with multidisciplinary representation (Yusuf et al., 2024). Similarly, national policy contexts create additional variation, as studies from countries having established AI frameworks (Chan & Lee, 2023), like in China, showed more consistent trust patterns than those in Oman, for instance (Bhat et al., 2024).

Cognitive factors (familiarity, self-efficacy, sense of control) emerged as bridges between demographics and trust formation, with our findings revealing that a perceived sense of control through human-in-the-loop approaches significantly influences trust development (Salah, 2024). This suggests that preserving educators’ professional autonomy is very important for successful GenAI integration. The emotional-psychological factors of trust (examined in 59.5% of studies) demonstrated that trust-building strategies should incorporate opportunities for positive emotional engagement with technology, moving beyond purely technical training approaches (Bhat et al., 2024; Mamo et al., 2024). Particularly noteworthy is that pedagogical factors emerge as an important factor in trust formation, suggesting that institutional strategies should focus on aligning GenAI integration with educators’ pedagogical goals.

Furthermore, the socio-ethical context shapes educators’ trust formation, with utilitarian factors translating to increased trust only when aligned with pedagogical beliefs (Jain & Raghuram, 2024). This finding helps explain the contradictory results we observe across studies examining perceived usefulness as a trust predictor. Studies that explicitly measured pedagogical alignment alongside utilitarian perceptions (Choi et al., 2023; Jain & Raghuram, 2024) consistently found strong usefulness-trust relationships, while those treating usefulness as an independent factor (Bhat et al., 2024; Camilleri, 2024) showed weak or inconsistent effects. A particularly revealing example comes from Choi et al. (2023), who found that constructivist educators showed strong correlations between perceived usefulness and trust, while those with transmissive pedagogical beliefs showed minimal relationships despite having similar technology exposure. This pattern suggests that traditional technology acceptance models may produce misleading results when applied without considering the pedagogical factors that mediate the relationship between utility and trust.

Social influence mechanisms (identified in 21.6% of studies) suggest that peer networks function as trust intermediaries, while ethical considerations form fundamental barriers to trust that cannot be overcome through traditional adoption incentives alone (Bhaskar & Rana, 2024; Yusuf et al., 2024).

Regarding the second research sub-question (RQ2) on institutional strategies, our analysis identified several gaps in the interactions between institutional strategies and educators’ trust factors in GenAI adoption. Although leadership support is a critical trust element that can validate educators’ emotional experiences and reinforce pedagogical factors, it is not adequately addressed (Ofosu-Ampong, 2024). Institutional policies and guidelines aim to address academic misconduct and ethical concerns, which are particularly important for educators with lower trust propensity but fail to account for demographic differences and pedagogical diversity (Bannister et al., 2024; Jain & Raghuram, 2024). Finally, the training initiatives demonstrate the potential of several interactions with educators’ trust factors by enhancing familiarity, self-efficacy, and sense of control while creating positive emotional experiences with GenAI. However, the effectiveness of these interactions is compromised by significant implementation gaps (Kamoun et al., 2024).

Summing up, our findings support the relevance of the proposed conceptual framework and its novelty in addressing persistent gaps in existing AI trust models. While the deductive structure of the review reflects the framework’s coherence with current literature, its empirical validation remains a task for future studies. The prominence of pedagogical considerations (27% of studies) and the notable leadership gap (10.8% of studies) highlight dimensions that prior models inadequately address. These findings suggest that trust in educational AI contexts operates differently from general technology adoption, requiring domain-specific theoretical approaches that account for professional identity, pedagogical values, and institutional mediation.

Theoretical implications

From a theoretical perspective, this review challenges the adequacy of existing AI trust and acceptance models, suggesting the need for new conceptual models that better account for the role of pedagogical philosophy and institutional strategies in understanding trust in GenAI. This review contributes to trust theory by developing an integrated framework that addresses three critical limitations identified in existing AI trust models: insufficient attention to pedagogical factors, limited examination of institutional strategies and failure to address GenAI ethical concerns.

Unlike prior frameworks, which primarily investigated technical AI trust factors (e.g., competence, privacy, explainability), our conceptual model considers higher education institutional strategies as the key structural assurances (McKnight et al., 2011) that interact with educators’ trust factors in GenAI. Our evidence shows that professional support appears in 45.9% of studies, while leadership support appears in only 10.8% demonstrating that institutional strategies operate unevenly in practice. This gap between theoretical importance and empirical attention suggests that future trust models must account for implementation challenges within institutional hierarchies, not just the presence or absence of policies.

Our Trustor (Educator) category extended traditional frameworks by integrating pedagogical belief and knowledge as educator-specific factors overlooked by existing models (Cabero-Almenara et al., 2024; Choi et al., 2023). The finding that perceived usefulness correlates with trust only when aligned with pedagogical beliefs challenges the universal applicability of TAM/UTAUT models. This suggests that trust frameworks for professional contexts require integration of domain-specific identity factors that mediate relationships between utility perceptions and trust formation.

The socio-ethical context category, including social influence and ethical considerations, further extends existing theoretical frameworks by addressing GenAI in educational settings (Bhaskar et al., 2024; Yan et al., 2024). Unlike technical AI frameworks that treat ethics as system characteristics, our findings show that ethical concerns (16.2% of studies) operate as fundamental barriers that cannot be overcome through traditional adoption incentives.

These theoretical contributions suggest that trust in professional AI contexts requires frameworks that integrate professional identity, institutional mediation, and value alignment as core constructs rather than contextual considerations. However, our deductive approach limits claims about theoretical innovation. Future work should test whether this integrated framework provides better predictive power than existing models or whether the added complexity obscures more fundamental trust mechanisms.

Next, we discuss how higher education institutions and policymakers can translate these findings into strategies for trustworthy GenAI adoption.

Implications for policy and practice

To support institutions and educators, five possible key policy actions could be derived from the analysed articles: (1) strengthen institutional leadership and structural assurances by closing leadership gaps, fostering positive social influence mechanisms, and co-creating policies with educators to ensure pedagogical and ethical relevance (Bhat et al., 2024; Crawford et al., 2023; Yusuf et al., 2024); (2) adopt phased and inclusive GenAI integration strategies that allow gradual experimentation across disciplines while embedding safeguards for academic integrity, data ethics, and cultural inclusivity (Karkoulian et al., 2024; Dabis & Csáki, 2024); (3) promote active educator participation in governance by involving faculty in committees and policy design processes, which strengthens both individual trust and institutional legitimacy (Chan, 2023; Yan et al., 2024); (4) establish clear institutional policies on academic integrity and ethical GenAI use, including guidelines on plagiarism, citation of AI-generated content, and culturally sensitive data practices (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2024; Dabis & Csáki, 2024); and (5) consider aligning higher education policy with global trustworthy AI frameworks and adapt them to local educational and cultural contexts (Aler Tubella et al., 2024).

The prominence of training initiatives mentioned in our analysis shows that building trust depends on educators’ capacity to evaluate, adapt, and responsibly apply GenAI in their teaching. Our findings suggest the need to develop dedicated AI literacy policies, as the UNESCO AI Competency Frameworks for Teachers (UNESCO, 2024) also recommends. Thus, the following actions might be considered: (1) develop AI ethics and bias awareness training for educators, mandated as part of professional development (Bozkurt et al., 2024; Cukurova et al., 2023); (2) integrate AI literacy into curricular standards and accreditation requirements to ensure that both staff and students achieve baseline competencies (Yang et al., 2025), and (3) encourage train-the-trainer models, where early adopters mentor peers and build collective capacity (Long & Magerko, 2020).

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

This systematic review examined trust factors influencing higher education educators’ adoption of GenAI through an analysis of 37 peer-reviewed studies published between 2019 and August 2024. Our research contributes to advancing a trust-centred approach to GenAI integration in HEIs by proposing a new conceptual model that extends existing AI frameworks, emphasising the interaction between educators’ trust factors and institutional strategies. This model positions trust as an ongoing relational process between educators, technology, and institutional context, challenging approaches that treat GenAI integration as merely a technical implementation challenge.

Study limitations

Despite the strengths of the proposed model, our study has limitations. First, the focus on English-language publications published after 2019 yielded several findings on ChatGPT, the most used GenAI application in education during this time (Wang et al., 2024). This approach may have excluded perspectives from non-English speaking contexts and specific findings about other GenAI tools (e.g., Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot). Nevertheless, we believe this review’s conclusions apply to GenAI tools other than ChatGPT because our analysis was focused on trust factors rather than specific technical aspects of a particular tool. Second, our deductive coding methodology may have missed new trust factors that are particular to GenAI. Future research should employ inductive approaches to better capture educators’ GenAI perceptions and their impact on trust formation. Third, the contradictory demographic patterns we observed suggest our framework may oversimplify how individual characteristics operate across different institutional and cultural contexts. Our finding that leadership support appears in only 10.8% of studies, despite being theoretically positioned as foundational, raises questions about whether our theoretical emphasis matches empirical reality or reveals a significant research gap. Finally, a broader methodological limitation arises from the fast-evolving nature of GenAI itself. The rapid pace of technological innovation and institutional responses means that findings represent a snapshot in time and may need continual updating as new tools, policies, and practices emerge. This volatility highlights the importance of ongoing empirical research to ensure that trust frameworks remain relevant and responsive to the changing educational landscape.

Recommendations for future research

As previously mentioned, one important direction is to provide empirical evidence of the model’s robustness. This requires the identification and development of survey instruments that operationalise constructs such as familiarity, self-efficacy, sense of control, and ethical concerns across higher education. The quantitative insights should be complemented by qualitative case studies involving interviews and focus groups with educators and institutional leaders to understand how institutional policies, training programmes, and leadership approaches shape trust development over time. Given the leadership gap we identified, comparative case studies examining different institutional approaches to GenAI adoption would provide evidence about which combinations of leadership support, policies, and professional development most effectively build trust. Future research should investigate targeted interventions aimed at strengthening institutional capacity (Luo, 2024). For instance, evaluating the effectiveness of AI literacy initiatives (UNESCO, 2024), policy frameworks, and professional development programmes can provide evidence-based strategies for institutions to build sustainable trust in GenAI (Li et al., 2024). Furthermore, research should investigate how trust formation varies across disciplinary contexts, pedagogical approaches, and institutional types to determine whether our framework applies broadly or requires context-specific modifications. This disciplinary analysis would be particularly valuable for understanding how STEM versus humanities educators respond differently to GenAI integration.

An equally important direction involves ethnographic studies that examine how educators navigate challenges related to academic integrity, bias, and fairness in real classroom settings, providing insights into the practical operation of our socio-ethical context dimension. These studies should focus on documenting decision-making processes when educators encounter ethical dilemmas with GenAI, informing both theoretical refinement and evidence-based policy development that support trust-based GenAI integration.

These research priorities ultimately serve a broader purpose by enabling higher education to navigate GenAI integration as a thoughtful process of trust building rather than a race towards technological adoption. Our findings demonstrate that successful institutions are those that invest in building authentic trust through alignment with educators’ professional identities and institutional support. This trust-centred approach promises a fundamental reconceptualisation of GenAI’s role in education, transforming it from a mere tool into a collaborative partner in the educational process, guided by human wisdom and pedagogical purpose.

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Aler Tubella A, Mora-Cantallops M, Nieves JC (2024) How to teach responsible AI in higher education: challenges and opportunities. Ethics Inf Technol 26(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-023-09733-7

Abuhassna H, Adnan MABM, Awae F (2024) Exploring the synergy between instructional design models and learning theories: a systematic literature review. Contemp Educ Technol 16(2):ep499. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/14289

Afroogh S, Akbari A, Malone E, Kargar M, Alambeigi H (2024) Trust in AI: progress, challenges, and future directions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1568. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04044-8

Alexander PA (2020) Methodological guidance paper: the art and science of quality systematic reviews. Rev Educ Res 90(1):6–23. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319854352

Alhammad N, Yusof AB, Awae F, Abuhassna H, Edwards BI, & Adnan MABM (2024) E-learning platform effectiveness: theory integration, educational context, recommendation, and future agenda: a systematic literature review. In: Edwards et al. (eds.), Reimagining transformative educational spaces. Lecture notes in educational technology. Springer

Ivanova M, Grosseck G, Holotescu C (2024) Unveiling insights: A bibliometric analysis of artificial intelligence in teaching. In Inform 11(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics11010010

Lelescu A, Kabiraj S (2024) Digital Assessment in Higher Education: Sustainable Trends and Emerging Frontiers in the AI Era. In: Grosseck G, Sava S, Ion G, Malita L (eds) Digital Assessment in Higher Education. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-6136-4_2

Bach TA, Khan A, Hallock H, Beltrão G, Sousa S (2022) A systematic literature review of user trust in AI-enabled systems: an HCI perspective. Int J Human–Comput Interact 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2138826

Baig MI, Yadegaridehkordi E (2024) ChatGPT in the higher education: a systematic literature review and research challenges. Int J Educ Res 127:102411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102411

Bannister P, Alcalde Peñalver E, Santamaría Urbieta A (2024) Transnational higher education cultures and generative AI: a nominal group study for policy development in English medium instruction. J Multicult Educ 18(1/2):173–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-10-2023-0102

Belur J, Tompson L, Thornton A, Simon M (2021) Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociol Methods Res 50(2):837–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799372

Bhaskar P, Rana S (2024) The ChatGPT dilemma: unravelling teachers’ perspectives on inhibiting and motivating factors for adoption of ChatGPT. J Inf Commun Ethics Soc 22(2):219–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-11-2023-0139

Bhaskar P, Misra P, Chopra G (2024) Shall I use ChatGPT? A study on perceived trust and perceived risk towards ChatGPT usage by teachers at higher education institutions. Int J Inf Learn Technol 41(4):428–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-11-2023-0220

Bhat Mohd A, Tiwari CK, Bhaskar P, Khan ST (2024) Examining ChatGPT adoption among educators in higher educational institutions using extended UTAUT model. J Inf Commun Ethics Soc. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-03-2024-0033

Bhullar PS, Joshi M, Chugh R (2024) ChatGPT in higher education—a synthesis of the literature and a future research agenda. Educ Inf Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12723-x

Bozkurt A, Xiao J, Farrow R, Bai JYH, Nerantzi C, Moore S, Dron J, Stracke CM, Singh L, Crompton H, Koutropoulos A, Terentev E, Pazurek A, Nichols M, Sidorkin AM, Costello E, Watson S, Mulligan D, Honeychurch S, Asino TI (2024) The manifesto for teaching and learning in a time of generative AI: a critical collective stance to better navigate the future. Open Prax 16(4):487–513. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.4.777

Brandhofer G, Tengler K (2024) Acceptance of artificial intelligence in education: opportunities, concerns and need for action. Adv Mob Learn Educ Res 4(2):1105–1113. https://doi.org/10.25082/AMLER.2024.02.005

Castelvecchi D (2016) The Black Box of AI. Nat N. 538(7623):20

Cabero-Almenara J, Palacios-Rodríguez A, Loaiza-Aguirre MI, Rivas-Manzano MdRd (2024) Acceptance of educational artificial intelligence by teachers and its relationship with some variables and pedagogical beliefs. Educ Sci 14(7):740. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070740

Cambra-Fierro JJ, Blasco MF, López-Pérez M-EE, Trifu A (2024) ChatGPT adoption and its influence on faculty well-being: an empirical research in higher education. Educ Inf Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12871-0

Camilleri MA (2024) Factors affecting performance expectancy and intentions to use ChatGPT: using SmartPLS to advance an information technology acceptance framework. Technol Forecast Soc Change 201:123247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123247

Celik I (2023) Towards Intelligent-TPACK: an empirical study on teachers’ professional knowledge to ethically integrate artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools into education. ComputHum Behav 138:107468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107468

Chan CKY (2023) A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 20(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00408-3

Chan CKY, Lee KKW (2023) The AI generation gap: are Gen Z students more interested in adopting generative AI such as ChatGPT in teaching and learning than their Gen X and millennial generation teachers? Smart Learn Environ 10(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-023-00269-3

Chatterjee S, Bhattacharjee KK (2020) Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: a quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling. Educ Inf Technol 25(5):3443–3463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10159-7

Chiu TKF, Xia Q, Zhou X, Chai CS, Cheng M (2023) Systematic literature review on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. Comput Educ Artif Intell 4:100118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100118

Choi S, Jang Y, Kim H (2023) Influence of pedagogical beliefs and perceived trust on teachers’ acceptance of educational artificial intelligence tools. Int J Hum–Comput Interact 39(4):910–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2049145

Choung H, David P, Ross A (2022) Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. Int J Hum–Comput Interact 39(9):1727–1739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2050543

Crawford J, Cowling M, Allen K-A (2023) Leadership is needed for ethical ChatGPT: character, assessment, and learning using artificial intelligence (AI). J Univ Teach Learn Pract 20(3). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.3.02

Crompton H, Burke D (2024) The educational affordances and challenges of ChatGPT: state of the field. TechTrends 68(2):380–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00939-0

Cruzes DS, Dyba T (2011) Recommended steps for thematic synthesis in software engineering. In 2011 International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement. pp. 275–284. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ESEM.2011.36

Cukurova M, Miao X, Brooker R (2023) Adoption of artificial intelligence in schools: unveiling factors influencing teachers engagement. International Conference of Artificial Intelligence in Education 2023, pp 151–163. Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36272-9_13

Dabis A, Csáki C (2024) AI and ethics: investigating the first policy responses of higher education institutions to the challenge of generative AI. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1006. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03526-z

Duah JE, McGivern P (2024) How generative artificial intelligence has blurred notions of authorial identity and academic norms in higher education, necessitating clear university usage policies. Int J Inf Learn Technol 41(2):180–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-11-2023-0213

Espartinez AS (2024) Exploring student and teacher perceptions of ChatGPT use in higher education: a Q-methodology study. Comput Educ Artif Intell 7:100264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100264

Fütterer T, Fischer C, Alekseeva A, Chen X, Tate T, Warschauer M, Gerjets P (2023) ChatGPT in education: global reactions to AI innovations. Sci Rep. 13(1):15310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42227-6

Ghimire A, Prather J, Edwards J (2024) Generative AI in education: a study of educators’ awareness, sentiments, and influencing factors. In 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). pp. 1–9. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE61694.2024.10892891

Gillespie N, Lockey S, Curtis C, Pool J, Ali Akbari (2023) Trust in artificial intelligence: a global study. The University of Queensland, KPMG Australia

Gimpel H, Hall K, Decker S, Eymann T, Lämmermann L, Mädche A, er R, Maximilian R, Caroline S, Manfred S, Mareike U, Nils V, Rik S (2023) Unlocking the power of generative AI models and systems such as GPT-4 and ChatGPT for higher education: a guide for students and lecturers. Hohenheim Discussion Papers in Business, Economics and Social Sciences. Universität Hohenheim, Stuttgart. https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:100-opus-21463

Glikson E, Woolley AW (2020) Human trust in artificial intelligence: review of empirical research. Acad Manag Ann 14(2):627–660. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0057

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S (2017) An introduction to systematic reviews. Sage Publications

Gulati S, Sousa S, Lamas D (2017) Modelling trust: an empirical assessment. In: Bernhaupt R, Dalvi G, Joshi A, Balkrishan DK, O’Neill J, Winckler M (eds.). Human-Computer Interaction—INTERACT 2017 (10516, pp. 40–61). Springer International Publishing

Hall R (2024) Generative AI and re-weaving a pedagogical horizon of social possibility. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 21(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00445-6

Herdiani A, Mahayana D, Rosmansyah Y (2024) Building trust in an artificial intelligence-based educational support system: a narrative review. J Sosioteknologi 23(1):101–119

Holmes W, Porayska-Pomsta K (Eds.). (2023) The ethics of artificial intelligence in education: Practices, challenges, and debates. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

Hyun Baek T, Kim M (2023) Is ChatGPT scary good? How user motivations affect creepiness and trust in generative artificial intelligence. Telemat Inform 83:102030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2023.102030

Jain KK, Raghuram JNV (2024) Gen-AI integration in higher education: predicting intentions using SEM-ANN approach. Educ Inf Technol 29(13):17169–17209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12506-4

Jameson J, Barnard J, Rumyantseva N, Essex R, Gkinopoulos T (2023) A systematic scoping review and textual narrative synthesis of trust amongst staff in higher education settings. Stud High Educ 48(3):424–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2145278

Kamoun F, El Ayeb W, Jabri I, Sifi S, Iqbal F (2024) Exploring students’ and faculty’s knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions towards ChatGPT: a cross-sectional empirical study. J Inf Technol Educ: Res 23:004. https://doi.org/10.28945/5239

Kaplan AD, Kessler TT, Brill JC, Hancock PA (2021) Trust in artificial intelligence: meta-analytic findings. Hum Factors J Hum Factors Ergonom Soc 65(2):337–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187208211013988

Karkoulian S, Sayegh N, Sayegh N (2024) ChatGPT unveiled: understanding perceptions of academic integrity in higher education—a qualitative approach. J Acad Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09543-6

Kasneci E, Sessler K, Küchemann S, Bannert M, Dementieva D, Fischer F, Gasser U, Groh G, Günnemann S, Hüllermeier E, Krusche S, Kutyniok G, Michaeli T, Nerdel C, Pfeffer J, Poquet O, Sailer M, Schmidt A, Seidel T, Kasneci G (2023) ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn Individ Differ 103:102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274

Kelly S, Kaye S-A, Oviedo-Trespalacios O (2023) What factors contribute to the acceptance of artificial intelligence? A systematic review. Telemat Inform 77:101925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101925

Kizilcec, RF (2023) To advance AI use in education, focus on understanding educators. Int J Artif Intell Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00351-4

Kurtz G, Amzalag M, Shaked N, Zaguri Y, Kohen-Vacs D, Gal E, Zailer G, Barak-Medina E (2024) Strategies for integrating generative AI into higher education: navigating challenges and leveraging opportunities. Educ Sci 14(5):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050503

Lee D, Arnold M, Srivastava A, Plastow K, Strelan P, Ploeckl F, Lekkas D, Palmer E (2024) The impact of generative AI on higher education learning and teaching: a study of educators’ perspectives. Comput Educ Artif Intell 6:100221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100221

Li Y, Wu B, Huang Y, Luan S (2024) Developing trustworthy artificial intelligence: insights from research on interpersonal, human-automation, and human-AI trust. Front Psychol 15:1382693. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1382693

Liu S-H (2011) Factors related to pedagogical beliefs of teachers and technology integration. Comput Educ 56(4):1012–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.12.001

Lockey S, Gillespie N, Holm D, Someh IA (2021) A review of trust in artificial intelligence: challenges, vulnerabilities and future directions. Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 5463–5472. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2021.664

Long D, Magerko B (2020) What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–16. ACM Digital Library. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376727

Lukyanenko R, Maass W, Storey VC (2022) Trust in artificial intelligence: from a foundational trust framework to emerging research opportunities. Electron Mark 32(4):1993–2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-022-00605-4

Luo (Jess), J (2024) A critical review of GenAI policies in higher education assessment: a call to reconsider the “originality” of students’ work. Assess Eval High Educ 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2309963

Mamo Y, Crompton H, Burke D, Nickel C (2024) Higher education faculty perceptions of ChatGPT and the influencing factors: a sentiment analysis of X. TechTrends 68(3):520–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00954-1

Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD (1995) An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad Manag Rev 20(3):709. https://doi.org/10.2307/25879

Mcknight DH, Carter M, Thatcher JB, Clay PF (2011) Trust in a specific technology: an investigation of its components and measures. ACM Trans Manag Inf Syst 2(2):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/1985347.1985353

Mishra P, Koehler MJ (2006) Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teach Coll Rec 108:1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Mishra P, Oster N, Henriksen D (2024) Generative AI, teacher knowledge and educational research: bridging short- and long-term perspectives. TechTrends 68(2):205–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00938-1

Nazaretsky T, Ariely M, Cukurova M, Alexandron G (2022) Teachers’ trust in AI-powered educational technology and a professional development program to improve it. Br J Educ Technol 53(4):914–931. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13232

Niedlich S, Kallfaß A, Pohle S, Bormann I (2021) A comprehensive view of trust in education: conclusions from a systematic literature review. Rev Educ 9(1):124–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3239

Ofosu-Ampong K (2024) Beyond the hype: exploring faculty perceptions and acceptability of AI in teaching practices. Discov Educ 3(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00128-4

Ogunleye B, Zakariyyah KI, Ajao O, Olayinka O, Sharma H (2024) A systematic review of generative AI for teaching and learning practice. Educ Sci 14(6):636. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060636

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pajares MF (1992) Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: cleaning up a messy construct. Rev Educ Res 62(3):307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

Paulus T, Woods M, Atkins DP, Macklin R (2017) The discourse of QDAS: Reporting practices of ATLAS.ti and NVivo users with implications for best practices. Int J Soc Res Methodol 20(1):35–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1102454

Punch K, Oancea A (2014) Introduction to research methods in education (2nd edn). Sage Publications. https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5019136

Qin F, Li K, Yan J (2020) Understanding user trust in artificial intelligence‐based educational systems: evidence from China. Br J Educ Technol 51(5):1693–1710. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12994

Reinhardt K (2023) Trust and trustworthiness in AI ethics. AI Ethics 3(3):735–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00200-5

Salah M (2024) Chatting with ChatGPT: decoding the mind of Chatbot users and unveiling the intricate connections between user perception, trust and stereotype perception on self-esteem and psychological well-being. Curr Psychol 43(9):7843–7858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04989-0

Scherer R, Siddiq F, Tondeur J (2019) The technology acceptance model (TAM): a meta-analytic structural equation modelling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Comput Educ 128:13–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.009

UNESCO (2024) AI competency framework for teachers. UNESCO https://doi.org/10.54675/ZJTE2084

Viberg O, Cukurova M, Feldman-Maggor Y, Alexandron G, Shirai S, Kanemune S, Wasson B, Tømte C, Spikol D, Milrad M, Coelho R, Kizilcec RF (2024) What explains teachers’ trust in AI in education across six countries? Int J Artif Intell Educa. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-024-00433-x

Wang N, Wang X, Su Y-S (2024) Critical analysis of the technological affordances, challenges and future directions of Generative AI in education: a systematic review. Asia Pacific J Educ 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2024.2305156

Wang Y, Liu C, Tu Y-F (2021) Factors affecting the adoption of AI-based applications in higher education: an analysis of teachers’ perspectives using structural equation modeling. Educ Technol Soc 24(3):116–129. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27032860

Wölfel M, Shirzad MB, Reich A, Anderer K (2023) Knowledge-based and generative-AI-driven pedagogical conversational agents: a comparative study of grice’s cooperative principles and trust. Big Data Cogn Comput 8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc8010002

Wu K, Zhao Y, Zhu Q, Tan X, Zheng H (2011) A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. Int J Inf Manag 31(6):572–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.03.004

Xiao P, Chen Y, Bao W (2023) Waiting, banning, and embracing: an empirical analysis of adapting policies for generative AI in higher education. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4458269

Yan L, Sha L, Zhao L, Li Y, Martinez‐Maldonado R, Chen G, Li X, Jin Y, Gašević D (2024) Practical and ethical challenges of large language models in education: a systematic scoping review. Br J Educ Technol 55(1):90–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13370

Yang R, Wibowo S (2022) User trust in artificial intelligence: a comprehensive conceptual framework. Electron Mark 32(4):2053–2077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-022-00592-6

Yang Y, Zhang Y, Sun D, He W, Wei Y (2025) Navigating the landscape of AI literacy education: insights from a decade of research (2014–2024). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12(1):374. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04583-8