Abstract

With the rapid development of digital and immersive technologies, interior design education is shifting from traditional two-dimensional instruction to virtual interactive learning. To overcome the limitations of drawings and physical models in conveying spatial perception and design expression, this study developed a VR-based teaching platform integrating Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC) technologies to enhance spatial cognition and interaction efficiency. Based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), four dimensions—Learning Effectiveness (LE), Ease of Use & Tool Experience (EUTE), Engagement & Involvement (EI), and Continuance Intention (CI)—were compared between VR and traditional teaching. Experimental results show that the VR approach achieved higher scores across all indicators: Learning Effectiveness improved from 83.57 to 90.33, Ease of Use & Tool Experience from 82.82 to 87.88, Engagement & Involvement from 82.61 to 89.63, and Continuance Intention from 84.29 to 89.33. These findings demonstrate that VR-based instruction effectively enhances students’ spatial understanding, learning participation, and creative expression, providing empirical evidence for the digital and immersive transformation of interior design education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of digital and immersive technologies, Interior Design Education (IDE) is undergoing a profound transformation from traditional two-dimensional teaching to multidimensional virtual interactive teaching (Chellappa and Rohatgi, 2025; Meggs et al., 2012). However, mainstream teaching models still primarily rely on static media such as floor plans, renderings, and physical models (Guerin and Thompson, 2004; Fitoz, 2015). These approaches exhibit clear limitations in spatial perception, scale judgment, and functional layout representation, making it difficult to fully convey design intentions and spatial experiences. As a result, students often experience cognitive gaps in spatial understanding and design expression, which constrains both learning efficiency and creative capacity (Guerin, 1991; Weigand and Harwood, 2007). An even more critical issue is that traditional teaching relies on a unidirectional transmission of static images, lacking real-time interaction and perceptual feedback mechanisms. This not only reduces student engagement but also limits teachers’ ability to dynamically guide the learning process (Matthews et al., 2021; Fowles, 1991; Dickinson et al., 2012). Such a results-oriented approach is significantly misaligned with contemporary design education principles that emphasize experiential, interactive, and inquiry-based learning.

In recent years, Virtual Reality (VR) technology has been increasingly introduced into design education due to its immersive, interactive, and visual advantages (Li and Xie, 2022; Guevara et al., 2022; Assali and Alaali, 2024). Research has confirmed VR’s unique potential in spatial representation, design expression, and cognitive training; however, most studies remain focused on technical development or experiential perception, with relatively limited systematic empirical validation of its teaching effectiveness, learning mechanisms, and educational value (Afacan, 2016; Li et al., 2022; Guo and Li, 2025). Particularly, there is a lack of statistically supported research comparing VR teaching with traditional methods in terms of learning performance, emotional experience, and continued learning willingness. In other words, the instructional logic, cognitive pathways, and acceptance mechanisms of VR in interior design education remain an area that requires further in-depth exploration.

In this context, this study developed a VR-based interior design teaching platform that integrates Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC) technologies. The platform aims to create an interactive virtual teaching environment that enhances the integrity of teaching content, improves spatial cognition, increases the accuracy of design expression, and promotes efficient teacher-student interaction. Furthermore, the study incorporates key concepts from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to establish a comprehensive evaluation framework encompassing four dimensions—teaching effectiveness, system usability, immersive experience, and learning continuity—to systematically compare the outcomes of VR-based and traditional teaching methods.

The main innovations of this study are reflected in three aspects:

(1) Methodologically, a multi-scenario VR interactive system was developed, enabling real-time collaboration and instant feedback between teachers and students within a virtual environment, thereby overcoming the spatial constraints of traditional classrooms.

(2) Pedagogically, the study focuses on the role of VR in enhancing teaching interaction and optimizing learning feedback mechanisms, revealing its potential value in stimulating motivation, immersion, and cognitive deepening.

(3) Empirically, through A/B group comparative experiments and multidimensional quantitative evaluation, the study systematically assesses the educational effectiveness of the VR teaching platform, filling the gap in existing literature that lacks comprehensive comparative research.

In summary, this study not only responds to the practical demand for digitalization and immersion in design education but also empirically explores the mechanisms of “how to teach” and “how to learn” within VR-based pedagogical models. The findings are expected to provide new theoretical and methodological references for innovation and digital transformation in interior design education.

Literature review

With the rapid development of Virtual Reality (VR) technology, its application in interior design education has shifted from simple “spatial presentation” to an “immersive learning and cognitive training platform” (Makransky and Petersen, 2021; Beck, 2019). VR provides immersive 3D environments that allow students to explore interior layouts, spatial proportions, material textures, and lighting effects from a first-person perspective. This immersive experience not only enhances spatial understanding but also supports content comprehension and visual processing efficiency, which are critical for effective learning (Kuhail et al., 2022; Dengel and Mägdefrau, 2018). Compared with traditional 2D drawings or static renderings, VR environments can more intuitively convey complex spatial relationships, facilitate understanding of design intent and construction logic, and, to some extent, improve creative thinking and design judgment (Suhaimi et al., 2024; Zhu and Mansor, 2024). Before the widespread adoption of VR, interior design education also utilized other digital technologies, such as CAD modeling, 3D rendering software, and simulation tools, to aid visualization and design exploration. However, these technologies are mostly non-immersive and limited in supporting first-person spatial exploration and real-time interaction, which motivated the need to compare the effectiveness of traditional methods and VR-based learning environments.

Despite these advantages, most existing studies remain largely descriptive, focusing on immersion, visibility, and interactivity, with insufficient investigation into how these features translate into measurable learning outcomes (Bao and Chen, 2024; Zuo and MaloneBeach, 2010; Islamoglu and Deger, 2015). Recent experimental work highlights that visual and cognitive factors play central roles: for example, Makransky et al. (2019) found that reducing visual load in VR environments improves conceptual understanding, while Chao et al. (2019) demonstrated that higher frame rates and visual stability enhance visual search efficiency and reduce cognitive fatigue. These findings indicate that visual and cognitive efficiency mediates the relationship between system performance and learning outcomes.

Given these considerations, it is necessary to examine how system optimization and multidimensional learning outcomes manifest across different disciplinary applications of VR (Table 1). In architecture education, VR has been widely used to enhance students’ spatial judgment, design evaluation skills, and collaboration abilities, providing immersive scenarios to better understand building construction, spatial proportions, and lighting effects (Saleh et al., 2023; Kara, 2015; Özacar et al., 2023). However, these studies often emphasize technical development or perceptual experience, without investigating the causal relationship between system performance optimization and learning outcomes. In engineering design courses, VR supports simulation-based training to improve understanding of design processes, procedural steps, and teamwork (Lampropoulos et al., 2025; Shehadeh and Alshboul, 2025), yet the effects of technical parameters on cognitive performance and decision-making remain underexplored. Similarly, in digital construction and construction management, VR is applied for safety training, construction simulation, and spatial coordination exercises (Ohueri et al., 2025; Omrany et al., 2025), emphasizing operational skills and risk awareness, but systematic research on pedagogical significance and learning mechanisms is limited. Collectively, while cross-disciplinary studies demonstrate VR’s potential in education, empirical work that integrates system-level optimization with teaching effectiveness, including spatial understanding, content comprehension, and visual efficiency, is generally lacking.

To address the unclear impact of system performance on learning outcomes, computer graphics has proposed various rendering optimization methods to balance visual quality and system performance in complex scenes (Kobbelt and Botsch, 2004). Among them, Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC) are two representative techniques: the former dynamically adjusts model geometry and material precision based on observer distance to reduce computational load (Abualdenien and Borrmann, 2022; Seo et al., 1999), while the latter removes fully occluded objects to reduce GPU redundancy, thereby improving frame rate and system responsiveness (Lee et al., 2021; Staneker et al., 2006). Although these techniques have been widely implemented in architectural visualization and gaming, systematic empirical studies on how LOD and OC optimizations influence visual efficiency, comprehension, and learning performance in VR-based interior design education remain scarce.

Furthermore, existing VR education studies that attempt to examine the relationship between system performance and learning experience often rely on single scenarios, limited rendering conditions, or primarily subjective questionnaires (Cicek et al., 2021; Tcha-Tokey et al., 2016; Karimian et al., 2023), failing to establish a complete causal chain from technical optimization to learning outcomes. In particular, in high-complexity design teaching contexts, different combinations of rendering strategies (LOD and OC) may significantly affect students’ spatial understanding, content comprehension, and interaction efficiency—an issue that remains largely unexplored.

Based on this, the present study proposes a technology–pedagogy integrated research framework, embedding LOD and OC optimization strategies into a VR interior design teaching platform and systematically testing their impact on rendering performance and educational outcomes across multiple complexity scenarios. The study simultaneously collects system performance metrics (frame rate, latency) and student learning performance (spatial understanding, content comprehension, visual efficiency, design judgment, and interaction efficiency)through experimental methods to reveal the potential mechanisms by which VR system performance optimization enhances educational effectiveness.

Unlike previous research that only focuses on perceptual advantages or system performance, this study integrates technical optimization with educational outcomes, constructing a closed-loop validation model from system mechanisms to learning effectiveness, providing empirical evidence and theoretical support for optimizing immersive interior design teaching platforms. The innovation of this study lies in integrating computer graphics rendering optimization strategies with interior design learning mechanisms to explore how technical performance translates into cognitive benefits and behavioral outcomes in educational contexts. By revealing the combined effect of LOD and OC technologies on learning immersion, interaction efficiency, and spatial understanding, this study not only extends the application boundaries of VR in education but also provides new theoretical perspectives and practical pathways for the development and evaluation of future immersive teaching platforms.

Experimental design process and methodology

Experimental design and procedure

This study aims to investigate the application of Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC) optimization strategies in a VR platform for interior design education and to evaluate their impact on students’ spatial understanding, design judgment, and teacher–student interaction efficiency. The study included 120 second- and third-year undergraduate students majoring in interior design, randomly assigned to ensure a balanced sample distribution across experimental conditions. The experiment was conducted on a self‑developed VR platform built on the Unity engine, capable of simulating interior teaching scenarios of varying complexity, including spatial layout analysis, material selection, lighting observation, and functional optimization tasks. The platform also supports real‑time interaction between students and instructors, recreating the design‑practice context of an actual classroom. The system runs on a computer equipped with a high‑performance GPU (NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070), 32 GB RAM, and an Intel Core i7 (13th generation) processor, and immersive experiences are delivered using the HTC Vive Pro 2 headset.

A multi-condition controlled experimental design was employed. Different combinations of LOD levels and OC strategies were manipulated to create experimental conditions under high-, medium-, and low-complexity scenes. For LOD settings, model precision was dynamically adjusted according to students’ viewing distance: high LOD retained full geometric detail, while medium and low LOD reduced polygon counts to examine how precision variations affected spatial understanding and design judgment. The OC strategy removed objects fully occluded by others to reduce visual interference and assess its influence on cognition and interaction across different complexity scenarios.

During the experiment, students completed design tasks under each condition, engaging in autonomous exploration within the virtual environment and interacting with instructors, ensuring authenticity and continuity of interaction (Fig. 1).

Data collection followed a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative measures included scores from spatial understanding tests (based on 3D spatial positioning and functional layout judgment), design task evaluations (including task quality, functional appropriateness, and creativity), and teacher–student interaction efficiency (interaction frequency, feedback response time, etc). Qualitative data were obtained through experimental observation, behavioral video analysis, and participant interviews to analyze students’ spatial exploration paths, cognitive strategies, design decision-making processes, and dynamic features of teacher–student interaction under different optimization strategies. All experimental tasks were pre-tested and adjusted to ensure appropriate difficulty and comparability across scenes of different complexity.

For data analysis, paired-sample t-tests were conducted to compare quantitative indicators across different LOD and OC strategies, examining the significant effects of optimization strategies on students’ spatial understanding, design judgment, and interaction efficiency. Qualitative observations were combined to interpret and complement the t-test results by analyzing behavioral and strategic differences under different conditions. To reduce individual differences, a crossover design was applied, allowing different student groups to experience each rendering strategy in turn, ensuring that each participant’s performance under all conditions was recorded and analyzed.

This integrated experimental design not only evaluates the practical effects of LOD and OC optimization strategies in VR-based interior design education but also reveals the potential mechanisms by which rendering optimization influences spatial cognition, design decision-making, and teacher–student interaction, providing scientific evidence and practical guidance for the effective use of VR in interior design education.

Principles of LOD and OC technologies

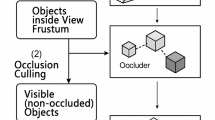

This study introduces Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC) optimization strategies in a VR platform for interior design education, aiming to systematically evaluate their effects on students’ spatial understanding, design judgment, and teacher–student interaction efficiency. LOD dynamically adjusts model precision according to the distance between the observer and objects, thereby reducing visual redundancy and allowing students to focus on key spatial elements (Kim et al., 2007). OC, on the other hand, eliminates the rendering of occluded objects, enhancing visual clarity and interaction efficiency (Sudarsky and Gotsman, 1999). Fundamentally, these optimization strategies aim to improve the allocation of visual load in virtual environments, enabling students to more efficiently acquire spatial information with limited attentional resources, thereby enhancing spatial cognition and the quality of design decision-making.

In Interior Design Education, LOD adjusts model detail based on observer distance, reducing visual clutter. OC culls occluded objects, improving visual clarity and interaction efficiency (Fig. 2).

LOD (Level of Detail) and OC (Occlusion Culling) are core rendering optimization techniques in virtual interior design teaching platforms. They are integrated to enhance students’ spatial understanding and design decision-making abilities within virtual environments. The basic principle of LOD is to dynamically adjust a 3D model’s geometric complexity and detail level based on the observer’s distance \(d\) from the model. Let the number of vertices at the highest detail level be \({V}_{\max }\) and at the lowest detail level be \({V}_{\min }\); then, the number of vertices \(V(d)\) at the current observation distance can be approximately calculated as:

Here, \({d}_{\min }\) and \({d}_{\max }\) represent the minimum and maximum observation distances for LOD switching, respectively. Using this formula, as the student’s viewpoint moves away from the target object, the number of model vertices automatically decreases, thereby reducing the rendering load and improving interaction smoothness, while maintaining visual fidelity when observed up close.

The OC technique reduces rendering burden by culling models that are completely occluded by other objects. Its principle can be expressed using the Visible Set (VS). Let the set of models in the scene be \(M=\{{m}_{1},{m}_{2},\ldots {m}_{n}\}\), and the visibility of each model is determined by the function \({f}_{vis}({m}_{i})\):

If \({m}_{i}\) is within the view frustum and not occluded, then \({f}_{vis}({m}_{i})\)=1; if \({m}_{i}\) is outside the view frustum or completely occluded, then \({f}_{vis}({m}_{i})\)=0.The Visible Set (\(VS\)) is then defined as:

In this study, LOD and OC are used in combination through a coordinated logic. LOD dynamically adjusts model complexity based on the observation distance, while OC further culls models that are occluded and not within the student’s direct line of sight, thereby minimizing rendering load and optimizing visual information. Considering both factors, the actual number of rendered vertices (\({V}_{render}\))can be expressed as:

Here, \(V({d}_{i})\) represents the number of vertices of model \({m}_{i}\) at observation distance \({d}_{i}\), and \(VS\) denotes the Visible Set. Using this formula, the system ensures detailed rendering of key spatial elements while reducing rendering of non-critical areas, thereby optimizing students’ cognitive efficiency and interaction experience. In the experiment, students completed interior design tasks under different combinations of conditions (high LOD + OC, low LOD + OC, and no optimization), with quantitative measures including spatial comprehension test scores, design task ratings, and teacher–student interaction efficiency.

Interactive teaching interface and real-time response

In this study’s VR interior design teaching platform, the interactive teaching interface serves as the core channel through which students engage with and learn from the virtual space. Its design goal is to enable students to actively manipulate the virtual environment. The platform supports multi-modal input methods, including gesture recognition, touch devices, and VR controllers. Through these interaction modes, students can freely rotate, scale, move, and edit 3D models, allowing them to intuitively explore spatial layouts, material selections, and lighting effects within the virtual environment (Fig. 3).

The platform’s real-time response mechanism ensures low latency and high consistency between students’ actions and feedback from the virtual scene. When students adjust models using gestures or VR controllers, the system immediately updates the view and object states, making the operation and visual feedback nearly synchronous. Let the input vector be \({I}_{t}\) and the current scene state be \({S}_{t}\); then the scene update after each operation can be expressed by the following formula:

In this process, the function \(f(\cdot )\) converts the user’s operation commands into model transformations, including position, rotation, scaling, and material adjustments. During these operations, the system dynamically applies LOD and OC optimization strategies to ensure smooth scene rendering while preserving detail in key areas, allowing students to experience a continuous, intuitive, and immersive interaction with the virtual space.

To enhance teaching interaction, the platform also integrates real-time annotation and feedback features. Teachers can instantly view students’ design modifications, providing guidance through virtual pointers, annotations, or voice prompts, while students can immediately respond and adjust their design plans. This two-way, real-time interaction not only improves communication efficiency between teachers and students but also encourages students to actively think about design logic and spatial relationships during operation, achieving a “learning by doing” effect.

Overall, this study’s multi-modal interaction design—incorporating gesture recognition, touch devices, and VR controllers—enables students to actively manipulate the design environment within the virtual space. Combined with the real-time response mechanism and LOD/OC optimization strategies, the platform delivers an immersive, intuitive, and efficient learning experience, promoting spatial cognition and design skills while providing teachers with technical support for real-time monitoring and guidance, thereby establishing an interactive ecosystem for virtual interior design education.

Cloud collaboration and remote teaching

To meet the demands of modern interior design education for cross-location and cross-device teaching, the VR platform in this study integrates cloud collaboration features, allowing teachers and students to simultaneously enter the same virtual space from different locations for design activities and instructional interactions. By managing the shared state of the virtual scene via cloud servers, students’ operations, design modifications, and spatial explorations are synchronized in real time across all students’ terminals, enabling immediate feedback and interaction in a multi-user collaborative environment. Teachers can remotely monitor students’ design progress and provide targeted guidance and annotations, while students can simultaneously view teachers’ demonstrations or comments, maintaining high levels of teacher–student interaction under remote conditions (Fig. 4).

The platform’s cloud collaboration mechanism employs intelligent data transmission and state synchronization to reduce network bandwidth pressure, while ensuring immersion and smooth interaction within the virtual environment. In multi-user collaborative mode, students can not only complete design tasks independently but also share spaces with group members, review each other’s designs, engage in discussions, and make improvements, thereby enhancing spatial understanding and design decision-making skills through collaborative learning.

In remote teaching practice, the cloud collaboration feature allows teachers to demonstrate spatial layouts, material selections, and lighting effects virtually, while students can simultaneously imitate, adjust, and innovate, achieving an immersive “learning by doing” teaching experience (Dong and Xie, 2025). This mechanism effectively overcomes physical space limitations, allowing VR teaching to extend beyond laboratories or classrooms to students’ homes, training sites, or other remote learning scenarios.

Overall, by combining cloud collaboration and remote teaching, the platform establishes a highly interactive, scalable, and flexible virtual teaching ecosystem. Within this environment, students can actively manipulate the virtual space, engage in collaborative exploration, and receive immediate feedback from teachers, while teachers can comprehensively monitor student activities and provide effective guidance. This setup enables efficient, immersive, and practice-oriented interior design education.

Platform interface design

The VR platform interface is designed based on LOD (Level of Detail) and OC (Occlusion Culling) technologies, aiming to provide an efficient, smooth, and immersive virtual environment for interior design instruction and spatial exploration. Functionally, the interface supports rapid switching between multiple rooms as well as real-time replacement of materials and lighting. Users can conveniently navigate to different rooms through a spatial navigation panel, with the system instantly loading the corresponding scene to help students compare different spatial layouts and design logics within the virtual environment. The material and lighting adjustment features allow students to freely change wall materials, floor textures, or lighting types, and instantly observe how these changes affect spatial atmosphere and visual effects, thus providing a more intuitive understanding of the relationships between color, lighting, and texture (Fig. 5).

A key interactive feature of the interface is the status display area located in the lower-left corner. This area provides real-time feedback on user actions and system performance information, such as current position, viewing direction, rendering load, and lighting mode. When users adjust materials or lighting, the status display dynamically updates parameter changes, enabling students to clearly understand the current design state and system response. This feature effectively enhances operational transparency and learning control, helping students develop more accurate spatial cognition and design awareness during exploration.

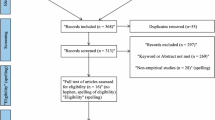

A/B comparative testing of VR and traditional teaching methods

Experimental design and testing methods

To validate the effectiveness of the VR platform based on LOD + OC technology in interior design education, this study employed an A/B testing approach to evaluate teaching outcomes. The participants were undergraduate students majoring in design, randomly divided into two groups: Group A, the traditional teaching group, and Group B, the VR teaching group.

In Group A, teaching content was delivered through conventional 2D drawings, model photographs, and instructor explanations, with students mainly relying on observation, discussion, and planar reasoning to understand spatial layouts and lighting relationships. Group B, under the same content and time conditions, used the VR platform developed in this study for learning and practice. Students independently navigated different rooms via the VR interface, adjusted materials and lighting configurations, and observed in real time how these design changes affected spatial perception and visual atmosphere.

Feedback from both groups was collected through structured questionnaires with identical frameworks. To ensure comparability, the dimensions used for assessment, the scoring system (0–100 points), and the number of items in each dimension remained consistent for both groups. Although some questions were rephrased to suit specific teaching contexts, the fundamental indicators remained unchanged, allowing for accurate measurement and comparison of learning outcomes between traditional and virtual reality-assisted learning.

The primary goal of the experiment was to compare the two teaching approaches across four aspects: teaching effectiveness, operational and usage experience, learning engagement, and willingness to continue learning. After instruction, data were collected through questionnaires, classroom performance evaluations, and analysis of student work. A comprehensive comparison between Groups A and B was conducted to assess the impact of VR teaching on these dimensions.

This study employed a 100-point questionnaire scoring system to quantitatively evaluate the experimental results. A total of 120 students participated, with 60 in Group A (traditional teaching) and 60 in Group B (VR teaching). After the experiment, both groups completed questionnaires covering the four key aspects of the study: teaching effectiveness, operational and usage experience, learning engagement, and willingness to continue learning, with each item scored on a 100-point scale. The use of a 100-point scale aimed to enhance the precision and comparability of the assessment. Compared to commonly used 5-point or 7-point scales, the 100-point system allows finer differentiation of students’ subjective perceptions, capturing subtle variations in cognition, engagement, and experience. Additionally, the percentile scale aligns more closely with students’ everyday evaluation habits, making it easier for them to intuitively understand and accurately express their perceptions of teaching effectiveness and learning experience.

Moreover, the continuous nature of the 100-point scale facilitates subsequent statistical analysis and significance testing. Methods such as ANOVA or t-tests can operate on higher-resolution data, thereby improving statistical power and reliability. Using this scoring system, the study comprehensively assessed differences between VR and traditional teaching across the four experimental aspects, providing robust data support for optimizing teaching methods.

Finally, after all questionnaires were collected, ten research team members were responsible for data aggregation and score calculation. The team summarized and verified scores for each item, excluded invalid or anomalous data, and computed both item-wise and overall average scores, which served as the primary basis for comparing the teaching effectiveness of the two groups.

Participant selection

All students recruited for this study possessed basic spatial comprehension skills and experience with digital design tools. To ensure representativeness and comparability of the experiment, the sample was balanced in terms of gender, grade level, age, and design experience. Based on an expected medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a significance level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.8, the minimum required sample size per group was calculated. The results indicated that at least 50 students per group were needed to meet statistical requirements. Therefore, this study selected 60 students per group (a total of 120 students) to ensure sufficient statistical power and reliability of the results.

All experiments were conducted in a standardized VR laboratory at the design school, with a duration of 4 weeks. Each student completed five VR design sessions, with each immersive experience lasting 30 min (including 5 min for adaptive adjustment), resulting in a total of 150 min of exposure. Students were randomly selected based on age, gender, educational background, and interior design experience. All research procedures strictly adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations, and the experimental protocol was approved by the authors’ institution. This study aims to establish a reproducible VR design education evaluation framework through systematic data collection and analysis, providing empirical evidence for the application of virtual reality technology in interior design education. The basic information of the students is shown in Table 2.

A total of 120 undergraduate students majoring in interior design or related fields were selected as students. All students volunteered and received standardized instructions prior to the experiment. To ensure representative and statistically valid sampling, the study maintained a relatively balanced distribution in terms of gender, age, grade level, and design experience.

Regarding gender, males and females each accounted for 50% of the sample (60 students per gender), ensuring a balanced gender ratio. Most students were aged 22–23 (96 students, 80%), while 24 students (20%) were 24 years or older, reflecting the typical age range of upper-level undergraduate students.

In terms of grade distribution, 66 students were sophomores (55%) and 54 students were juniors (45%). This distribution captures differences between students at different learning stages and allows comparison of the VR teaching platform’s effectiveness across varying levels of academic maturity.

Regarding design practice experience, 38 students (32%) had participated in design projects once or less, 43 students (35%) had 2–3 experiences, and 39 students (33%) had 4 or more design experiences. This relatively balanced distribution allows analysis of performance differences between students with varying levels of design experience under traditional and VR teaching conditions.

Indicator selection

Based on the theoretical framework of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and considering the characteristics of virtual reality (VR) teaching and its application in interior design education, this study constructed a more targeted and comprehensive evaluation system. The original dimensions of the TAM model were extended and redefined to form four core aspects: teaching effectiveness, operational and usage experience, learning engagement and involvement, and continuance intention. By evaluating these four dimensions, the system aims to comprehensively reflect the applicability and teaching effectiveness of different instructional methods in design education (Fig. 6).

First, Teaching Effectiveness focuses on assessing students’ actual improvements in knowledge comprehension, skill acquisition, and spatial cognition. Evaluation indicators include “design accuracy,” “task completion efficiency,” “spatial understanding ability,” and “innovation expression level,” which can be used to compare learning outcomes between traditional teaching and VR-based teaching.

Second, Operational and Usage Experience evaluates the convenience and usability of the instructional tools or platform from the student’s perspective. Indicators include “ease of operation,” “clarity of functions,” “stability of the tool or platform,” and “coordination and usability of different components.” This dimension reflects the VR platform’s operational experience and is also comparable to the use of traditional classroom materials, drawing tools, or physical models, enabling cross-method comparisons.

Third, Learning Engagement and Involvement focuses on students’ attention, interest, and interactive experience during the learning process. Its indicators include “degree of engagement,” “immersiveness in classroom or virtual environment,” “positive emotional state,” and “smoothness of interaction with instructors or peers.” This dimension allows assessment of both traditional classroom participation and VR-based immersive learning experiences.

Finally, Continuance Intention measures students’ willingness to continue using or recommend the instructional method after experiencing it. Evaluation indicators include “intention to reuse,” “willingness to recommend to others,” and “overall satisfaction,” which assess the long-term acceptance and appeal of both traditional and VR teaching approaches.

Comparison process between virtual reality and traditional teaching methods

To systematically compare the differences and advantages of VR-based teaching and traditional teaching in interior design education, this study employed an A/B controlled experimental design. Both groups were taught by the same instructor, with identical teaching content, task requirements, and assessment criteria; the only differences were in the instructional medium and learning approach. The experiment lasted 4 weeks and included three stages: instructional guidance, task practice, and learning evaluation.

(1) Group A: Traditional teaching process

Group A followed a conventional classroom model. Teaching activities were mainly conducted in classrooms and physical model laboratories, using materials such as 2D drawings, perspective renderings, physical models, and PowerPoint presentations (Fig. 7).

-

Instructional guidance stage: The instructor used case analyses and board explanations to help students understand spatial layouts, lighting changes, and material coordination principles (Fig. 7a).

-

Task practice stage: Students completed floor plans and elevations using 2D drawing software according to the design brief. Some students also created physical models to support spatial understanding (Fig. 7b).

-

Learning evaluation stage: The instructor assessed students’ submitted drawings and models, and questionnaires were used to collect students’ feedback on content mastery, learning satisfaction, and self-perceived understanding (Fig. 7c).

(2) Group B: VR teaching process

Group B used a VR teaching platform based on LOD (Level of Detail) and OC (Occlusion Culling) technologies. The platform provides smooth real-time rendering through automatic detail optimization and occlusion culling, while supporting multi-user collaboration (Fig. 8).

-

Instructional guidance stage: The instructor demonstrated the interior design process within the VR environment. Students wore head-mounted displays to enter the virtual classroom, where they learned key concepts through observation, interaction, and discussion (Fig. 8a).

-

Task practice stage: Students independently completed tasks such as building interior spaces, replacing materials, and configuring lighting. The interface allowed rapid switching between different room scenes and provided real-time visualization of material, lighting, and scale changes (Fig. 8b). A status feedback window in the lower-left corner of the interface reflected students’ operation progress, enabling the instructor to provide individualized guidance and real-time corrections.

-

Learning evaluation stage: Students submitted their virtual design projects, while the system recorded operation paths, time spent, and the number of modifications (Fig. 8c). Instructors and evaluators assessed the work based on both the submissions and system-recorded data. Additionally, questionnaires were used to collect students’ subjective feedback on ease of operation, immersion, and overall experience.

Qualitative interview design

To further supplement the experimental data and gain deeper insight into students’ authentic experiences and perceptions under different teaching modes, this study conducted qualitative interviews following the questionnaires and experimental evaluations. Thirty students were randomly selected from the total 120 students for semi-structured interviews, with 15 from Group A (traditional teaching) and 15 from Group B (VR teaching). The selected interviewees were balanced in terms of gender, grade level, and design experience to ensure the representativeness and comparability of the results. The interview focused on four main aspects:

-

1.

Changes in learning interest and attention.

-

2.

Perceived improvement in spatial understanding and design thinking.

-

3.

Teacher-student interaction and classroom participation experience.

-

4.

Overall satisfaction with the teaching method and suggestions for improvement.

Each interview lasted ~30–40 min. The research team recorded and organized the main responses to extract key insights and common feedback.

The significance of these interviews lies in their ability to supplement and validate the quantitative experimental results with qualitative data, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of how VR teaching influences the learning process. For instance, interviews can reveal subtle changes in spatial perception, learning motivation, and emotional engagement that are difficult to capture through questionnaires alone. In addition, students’ subjective evaluations of the teaching experience provide directional guidance for system optimization and future instructional design. By integrating quantitative and qualitative findings, the study offers a more comprehensive assessment of the educational effectiveness of VR teaching and provides empirical evidence and recommendations for the digital transformation of design education.

Results

Descriptive statistics

In this experimental study, we systematically analyzed students’ performance under traditional teaching and VR-based teaching methods. A total of ten evaluators independently scored 12 student works each, assessing key instructional and design indicators, including spatial understanding, visual expression, functional layout, and interactive participation. First, the mean scores and standard deviations for each indicator were calculated for both teaching methods, followed by descriptive statistical analysis to compare central tendencies and variability. Subsequently, independent-samples t-tests were conducted to verify the statistical significance of differences between the two groups. The results indicated that, in aspects such as Learning effectiveness(LE),Ease of use & tool experience(EUTE),Engagement & involvement(EI),Continuance intention(CI). VR-based teaching scores were significantly higher than those of traditional teaching. Overall, the statistical results suggest that VR teaching effectively enhances students’ spatial cognition and learning engagement. The score distributions and means for traditional and VR teaching are illustrated in Fig. 9.

In Fig. 9, the horizontal axis represents the evaluation dimensions, while the vertical axis shows the score levels. For the four core dimensions, the average scores under the traditional design method were: Learning Effectiveness 83.57, Ease of Use & Tool Experience 82.82, Engagement & Involvement 82.61, and Continuance Intention 84.29. For the VR-based design method, the corresponding average scores were: Learning Effectiveness 90.33, Ease of Use & Tool Experience 87.88, Engagement & Involvement 89.63, and Continuance Intention 89.33. Overall, VR teaching outperformed traditional methods across all dimensions, with the greatest differences observed in learning effectiveness and engagement & involvement.

According to Table 3, the scores across the four core dimensions reveal clear differences between traditional and VR teaching. In terms of Learning Effectiveness, traditional teaching averaged 83.57, while VR teaching scored 90.33, with a standard deviation of 6.76, indicating that VR instruction provides greater advantages in enhancing students’ design skills, task completion efficiency, and spatial understanding. For Ease of Use & Tool Experience, traditional teaching scored 82.82, whereas VR teaching scored 87.88 (SD = 5.06), highlighting superior usability, functionality integration, and operational smoothness in the VR platform. Regarding Engagement & Involvement, traditional teaching averaged 82.61, while VR teaching reached 89.63 (SD = 7.02), demonstrating that students in VR environments experience higher immersion and attention, leading to increased participation and task engagement. For Continuance Intention, traditional teaching scored 84.29, compared to 89.33 (SD = 5.03) for VR teaching, suggesting that VR instruction more effectively motivates students’ willingness to reuse, recommend, and overall satisfaction.

In summary, VR teaching outperforms traditional methods across all four dimensions, with the most pronounced advantages in Learning Effectiveness and Engagement & Involvement, demonstrating its significant value in enhancing learning outcomes, participation experience, and long-term acceptance.

Data analysis

In this study, to compare the differences in scores between traditional teaching and VR-based teaching across the four dimensions, independent-samples t-tests were conducted. The independent-samples t-test is a widely used statistical method for assessing whether the mean difference between two unrelated groups is statistically significant. This method assumes that both groups are drawn from normally distributed populations and evaluates significance by comparing the mean difference relative to the variability within each sample (Table 4).

Based on the analysis using independent-samples t-tests, all four core dimensions showed significant differences between VR teaching and traditional teaching. In terms of learning effectiveness, traditional teaching averaged 83.57 ± 2.40, while VR teaching scored 90.33 ± 2.01 (t = 7.48, p < 0.001), indicating that VR instruction significantly improves students’ design skills, task completion efficiency, and spatial understanding. For ease of use and tool experience, traditional teaching scored 82.82 ± 1.87, whereas VR teaching scored 87.88 ± 1.49 (t = 7.32, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the VR platform provides greater operational convenience and functional integration compared with traditional methods. Regarding engagement and involvement, traditional teaching averaged 82.61 ± 2.52, while VR teaching scored 89.63 ± 2.72 (t = 4.54, p < 0.001), indicating that students are more immersed and actively engaged in the VR learning environment. Finally, for continuance intention, traditional teaching averaged 84.29 ± 3.27, compared with 89.33 ± 1.46 for VR teaching (t = 4.87, p < 0.001), showing that VR instruction better motivates students to continue using the method and increases overall satisfaction. Overall, the results indicate that VR teaching significantly outperforms traditional teaching across all four dimensions, with particularly pronounced advantages in learning effectiveness and engagement and involvement, highlighting the VR platform’s effectiveness in enhancing learning outcomes, participation, and long-term acceptance.

Focus group discussion: comparison of traditional methods and VR methods

To further understand students’ real experiences and learning perceptions under different teaching methods, this study conducted focus group interviews. Focus groups allow guided discussions and interactions to capture students’ subjective evaluations, emotional responses, and subtle changes in learning motivation, which are difficult to measure through questionnaires alone. In addition, focus groups help identify potential issues, generate improvement suggestions, and provide qualitative support to experimental results, offering a more comprehensive analytical perspective (Table 5).

The interviews focused on students’ learning interest and classroom attention, their perceived improvement in spatial understanding and design thinking, classroom interaction experiences and teacher–student communication efficiency, and their overall satisfaction with the teaching method as well as suggestions for improvement.

Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the effectiveness of VR-based teaching in interior design education by combining quantitative data with focus group interview results and comparing it with traditional teaching. The findings indicate that VR teaching significantly outperforms traditional teaching across teaching effectiveness, ease of use and operation experience, learning engagement and involvement, and continuance intention (p < 0.001). Moreover, the interview feedback further revealed the underlying educational mechanisms and advantages of VR-based instruction.

From the perspective of cognitive and skill development, VR teaching significantly enhanced students’ spatial understanding and design expression abilities. In the quantitative analysis, the VR group scored an average of 90.33 in teaching effectiveness, significantly higher than the traditional group’s 83.57. This demonstrates the clear advantage of the VR platform in knowledge acquisition, task completion efficiency, and spatial cognition. Interviews revealed that students could intuitively observe spatial layouts, lighting changes, and material combinations in 3D scenarios, allowing for more accurate judgment of design solutions. This aligns with cognitive psychology theories of “situated learning” and ‘reduced cognitive load through visualization,” which suggest that presenting complex spatial information in an immersive environment can lower cognitive load and facilitate understanding and application (Mukasheva et al., 2023; Giamellaro, 2014).

In terms of operational experience and system usability, VR teaching provided highly controllable and intuitive interactions. The VR group scored 87.88 on ease of use and tool experience, higher than the traditional group’s 82.82. Interview feedback indicated that students could switch between spaces, replace materials, and adjust lighting in real time, with the lower-left status feedback window clearly displaying their progress and operational state. This immediate feedback mechanism not only improved operational efficiency but also increased opportunities for self-directed exploration, thereby enhancing learning motivation (Wang et al., 2024). By contrast, traditional teaching relied on 2D drawings and physical models, limiting interaction and providing delayed feedback, which hindered a continuous engagement experience (Wu et al., 2012).

Regarding learning engagement and involvement, VR teaching significantly boosted students’ initiative and classroom participation. The VR group scored 89.63 on this dimension, compared with 82.61 for the traditional group. Interviews showed that students in VR environments experienced higher immersion, greater focus, and a stronger willingness to experiment with different solutions and design parameters. In traditional classrooms, students generally reported limited participation, distracted attention, and low motivation for exploration (Abdel Meguid and Collins, 2017). These findings suggest that VR technology provides a highly immersive and interactive learning environment that enhances psychological motivation and engagement, consistent with experiential learning theory.

In terms of continuance intention and long-term acceptance, VR teaching also showed advantages. The VR group scored 89.33 in continuance intention, higher than the traditional group’s 84.29. Interview results indicated that most VR students expressed a willingness to use the platform again and to recommend it to peers, highlighting the platform’s potential for sustained use in future teaching. Consistent with the TAM model’s concept of continuance intention, VR teaching enhances students’ positive attitudes and behavioral intentions through improved learning experience and operational convenience, providing a foundation for ongoing pedagogical optimization.

Additionally, the study found that VR teaching has unique value for teacher-student interaction. Traditional teaching is limited by physical space, making it difficult for instructors to provide real-time guidance for every student. In contrast, the VR platform’s status feedback window and multi-user collaboration features allowed teachers to observe students’ learning states instantly and provide targeted guidance. Interviews revealed that group collaboration and class discussions were more efficient, and problems could be addressed promptly, which is important for fostering teamwork and design thinking.

It is worth noting that this study also considered the potential impact of VR system performance on learning outcomes. To ensure immersive experiences and smooth interaction in complex scenarios, LOD (Level of Detail) and OC (Occlusion Culling) techniques were combined to optimize virtual environment rendering performance. This integration allowed the VR platform to maintain high frame rates and real-time responsiveness in highly complex scenes, ensuring smooth spatial exploration, design operations, and multi-scene transitions. Such technical support not only enhanced immersion and operational experience but also contributed to improved spatial cognition, design judgment, and learning engagement.

However, several deeper limitations and considerations emerge from the study. First, while students were second- and third-year undergraduates, prior experience with VR varied among students, potentially introducing a performance bias. Students familiar with immersive technologies may have navigated the environment more efficiently, affecting task completion times and engagement levels. This suggests that individual differences in technological literacy should be controlled or accounted for in future studies to isolate the effect of VR pedagogy itself.

Second, the VR teaching experiment lasted 4 weeks, which provides only a short-term view of learning outcomes. Longitudinal effects, such as retention of spatial understanding, transfer of design skills to real-world projects, and sustained engagement, remain untested. Future studies could incorporate follow-up assessments or repeated measures to examine whether the observed advantages persist over time and translate into professional competencies.

Third, scalability and cost remain critical practical considerations. High-performance VR hardware, such as advanced GPUs and headsets, may not be readily available in all educational institutions, limiting broader implementation. Additionally, integrating VR platforms into curricula requires training instructors, maintaining hardware, and updating software, all of which involve institutional investment. Evaluating cost-benefit trade-offs and exploring more accessible VR solutions could inform practical adoption strategies.

Finally, while the VR environment allowed for immersive interaction, it is still an abstraction of real-world interior design practice. Factors such as tactile feedback, material behavior under natural conditions, and social interactions in physical spaces cannot be fully replicated. Recognizing these limitations highlights the need to combine VR with complementary teaching approaches, such as studio practice or physical model exercises, to achieve holistic skill development.

In conclusion, the quantitative data and qualitative interview results consistently indicate that VR teaching outperforms traditional teaching in enhancing spatial cognition, operational experience, learning engagement, and long-term learning intention. At the same time, careful consideration of participant differences, long-term effects, cost, scalability, and ecological validity is necessary to contextualize these findings and guide the future design of VR-based learning environments. The findings not only validate the practical value of VR technology in design education but also provide theoretical foundations and practical guidance for optimizing immersive, digital teaching models.

Conclusion

This study systematically evaluated the application of virtual reality (VR) teaching versus traditional teaching in interior design education through an empirical experiment involving 120 undergraduate students and focus group interviews with 30 students. A comprehensive evaluation system was established, centered on teaching effectiveness, operational experience, learning engagement, and continuance intention. The results indicate that VR teaching significantly outperforms traditional methods in enhancing students’ spatial cognition, design expression, and task completion efficiency. Additionally, the immersive experience and multi-scene operations provided by VR improve operational convenience, system usability, and students’ ability to explore independently. Compared to traditional 2D teaching, the VR platform offers more intuitive spatial perception and real-time feedback, enabling students to better understand lighting changes, material combinations, and spatial layouts, thereby significantly improving learning efficiency and design accuracy.

Focus group data further revealed that VR teaching not only increases students’ engagement and classroom interaction but also promotes proactive learning and teamwork skills. In the virtual environment, students can instantly observe and adjust design solutions, and this high degree of operational freedom enhances motivation, stimulates creative thinking, and allows design ideas to be more accurately expressed and validated. Notably, in terms of continuance intention, students demonstrated a high willingness to reuse and recommend the platform, suggesting that VR teaching has potential advantages in fostering long-term learning behaviors and supporting autonomous learning.

Importantly, the study also highlights concrete limitations and practical considerations. First, students’ prior VR experience and individual technical proficiency likely influenced engagement and performance, indicating that preparatory training or gradual acclimation may be necessary for equitable outcomes. Second, the experiment lasted only 4 weeks, leaving long-term retention, skill transfer, and sustained motivation unexamined. Third, hardware costs, device comfort, and VR system realism remain barriers for broader adoption in educational institutions. These factors suggest that successful implementation requires careful planning, including phased integration with traditional teaching, cost-effective hardware solutions, and iterative system design to enhance usability and realism.

For future research, these findings point to actionable directions: investigating hybrid teaching models that combine VR and traditional approaches to balance immersion and practical hands-on experience; testing haptic feedback, AI-driven personalization, or adaptive guidance to further tailor VR experiences; and conducting longitudinal studies to measure knowledge retention, design skill transfer, and sustained engagement. Such work will provide educators with concrete evidence on how to implement VR effectively, optimize learning outcomes, and scale immersive teaching in interior design and related disciplines.

Overall, this study not only demonstrates VR’s potential to transform interior design education but also provides a practical roadmap for integrating immersive technologies into curriculum design, teaching strategies, and student learning support, offering a grounded foundation for both pedagogical innovation and scalable implementation.

Data availability

The data used in the research can be made available upon request by contacting the authors.

References

Abdel Meguid E, Collins M (2017) Students’ perceptions of lecturing approaches: traditional versus interactive teaching. Adv Med Educ Pract 229–241. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S131851

Abualdenien J, Borrmann A (2022) Levels of detail, development, definition, and information need: a critical literature review. J Inf Technol Constr 27. https://doi.org/10.36680/j.itcon.2022.018

Afacan Y (2016) Exploring the effectiveness of blended learning in interior design education. Innov Educ Teach Int 53(5):508–518

Assali I, Alaali A (2024) Integrating technology into interior design education: A paradigm shift in teaching and learning. In: Board diversity and corporate governance. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53877-3_45

Bao S, Chen W (2024) Innovative applications of augmented reality technology in interior design education and the impact on learner experience. J Comput Methods Sci Eng 14727978251322337. https://doi.org/10.1177/14727978251322337

Beck D (2019) Augmented and virtual reality in education: Immersive learning research. J Educ Comput Res 57(7):1619–1625

Chao CJ, Yau YJ, Lin CH, Feng WY (2019) Effects of display technologies on operation performances and visual fatigue. Displays 57:34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2019.03.003

Chellappa V, Rohatgi T (2025) Students’ perceptions towards sustainability in interior design education. Int J Technol Des Educ 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-025-09965-2

Cicek I, Bernik A, Tomicic I (2021) Student thoughts on virtual reality in higher education—a survey questionnaire. Information 12(4):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12040151

Dengel A, Mägdefrau J (2018) Immersive learning explored: Subjective and objective factors influencing learning outcomes in immersive educational virtual environments. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE international conference on teaching, assessment, and learning for engineering (TALE). IEEE, pp 608–615. https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE.2018.8615281

Dickinson JI, Anthony L, Marsden JP (2012) A survey on practitioner attitudes toward research in interior design education. J Inter Des 37(3):1–22

Dong X, Xie Y (2025) Research on cloud computing network security mechanism and optimization in university education management informatization based on OpenFlow. Syst Soft Comput 200225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sasc.2025.200225

Fitoz I (2015) Interior design education programs during historical periods. Proc Soc Behav Sci 174:4122–4129

Fowles DL (1991) Interior design education in the year 2000: A challenge to change. J Inter Des Educ Res 17(2):17–24

Giamellaro M (2014) Primary contextualization of science learning through immersion in content-rich settings. Int J Sci Educ 36(17):2848–2871

Guerin DA (1991) Issues facing interior design education in the twenty–first century. J Inter Des Educ Res 17(2):9–16

Guerin DA, Thompson JAA (2004) Interior design education in the 21st century: An educational transformation. J Inter Des 30(2):1–12

Guevara D, de Laski-Smith D, Ashur S (2022) Interior design students’ perception of virtual reality. SN Soc Sci 2(8):152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00423-7

Guo J, Li C (2025) Effect of virtual reality intelligent interior design platform on interior design education at the junior college level. Int J Sociol Anthropol Sci Rev 5(2):439–448. https://doi.org/10.60027/ijsasr.2025.5756

Islamoglu OS, Deger KO (2015) The location of computer aided drawing and hand drawing on design and presentation in the interior design education. Proc Soc Behav Sci 182:607–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.792

Kara L (2015) A critical look at the digital technologies in architectural education: when, where, and how. Proc Soc Behav Sci 176:526–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.506

Karimian Z, Barkhor A, Mehrabi M, Khojasteh L (2023) Which virtual education methods do e-students prefer? Design and validation of Virtual Education Preferences Questionnaire (VEPQ). BMC Med Educ 23(1):722. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04687-2

Kim H, Yoon Y, Park H (2007) Adaptation Method for Level of Detail (LOD) of 3D contents. In: Proceedings of the 2007 IFIP international conference on network and parallel computing workshops (NPC 2007). IEEE, pp 879–884. https://doi.org/10.1109/NPC.2007.82

Kobbelt L, Botsch M (2004) A survey of point-based techniques in computer graphics. Comput Graph 28(6):801–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2004.08.009

Kuhail MA, ElSayary A, Farooq S, Alghamdi A (2022) Exploring Immersive Learning Experiences: A Survey. Informatics 9(4):75

Lampropoulos G, Fernández-Arias P, de Bosque A, Vergara D (2025) Virtual reality in engineering education: A scoping review. Educ Sci 15(8):1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081027

Lee GB, Jeong M, Seok Y, Lee S (2021) Hierarchical raster occlusion culling. Comput Graph Forum 40(2):489–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.142649

Li W, Xue Z, Li J, Wang H (2022) The interior environment design for entrepreneurship education under the virtual reality and artificial intelligence-based learning environment. Front Psychol 13:944060

Li C, Xie G (2022) The application of virtual reality technology in interior design education: A case study exploring learner acceptance. In: Proceedings of the 2022 2nd international conference on consumer electronics and computer engineering (ICCECE). IEEE, pp 680–684. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCECE54139.2022.9712831

Makransky G, Petersen GB (2021) The cognitive affective model of immersive learning (CAMIL): A theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educ Psychol Rev 33(3):937–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09586-2

Makransky G, Borre‐Gude S, Mayer RE (2019) Motivational and cognitive benefits of training in immersive virtual reality based on multiple assessments. J Comput Assist Learn 35(6):691–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12375

Matthews C, Brown N, Brooks M (2021) Confronting lack of student diversity in interior design education. J Inter Des 46(4):3–11

Meggs SM, Greer A, Collins S (2012) Virtual reality in interior design education: Enhanced outcomes through constructivist engagement in Second Life. Int J Web-Based Learn Teach Technol 7(1):19–35. https://doi.org/10.4018/jwltt.2012010102

Mukasheva M, Kornilov I, Beisembayev G, Soroko N, Sarsimbayeva S, Omirzakova A (2023) Contextual structure as an approach to the study of virtual reality learning environment. Cogent Educ 10(1):2165788

Ohueri CC, Masrom MAN, Lohana S (2025) Advances in immersive virtual reality–based construction management student learning. J Constr Eng Manag 151(1):03124009. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-1534

Omrany H, Al-Obaidi KM, Ghaffarianhoseini A, Chang RD, Park C, Rahimian F (2025) Digital twin technology for education, training and learning in construction industry: implications for research and practice. Eng Constr Archit Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2024-1376

Özacar K, Ortakcı Y, Küçükkara MY (2023) VRArchEducation: Redesigning building survey process in architectural education using collaborative virtual reality. Comput Graph 113:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2023.04.008

Saleh MM, Abdelkader M, Hosny SS (2023) Architectural education challenges and opportunities in a post-pandemic digital age. Ain Shams Eng J 14(8):102027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2022.102027

Seo J, Kim GJ, Kang KC (1999) Levels of detail (LOD) engineering of VR objects. In: Proceedings of the ACM symposium on Virtual reality software and technology. pp 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1145/323663.323680

Shehadeh A, Alshboul O (2025) Enhancing engineering and architectural design through virtual reality and machine learning integration. Buildings 15(3):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030328

Staneker D, Bartz D, Straßer W (2006) Occlusion-driven scene sorting for efficient culling. In: Proceedings of the 4th international conference on Computer graphics, virtual reality, visualisation and interaction in Africa, pp 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1145/1108590.1108607

Sudarsky O, Gotsman C (1999) Dynamic scene occlusion culling. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 5(1):13–29

Suhaimi MS, Mahamarowi NH, Azli AF, Narizal MNI (2024) The intersection of technology and education: An immersive interior design digital application as an innovative teaching tool. In: Proceedings of the 2024 20th IEEE international colloquium on signal processing & its applications (CSPA). IEEE, pp 242–247. https://doi.org/10.1109/CSPA60979.2024.10525462

Tcha-Tokey K, Loup-Escande E, Christmann O, Richir S (2016) A questionnaire to measure the user experience in immersive virtual environments. In: Proceedings of the 2016 virtual reality international conference, pp 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1145/2927929.2927955

Wang WS, Pedaste M, Huang YM (2024) The impact of feedback mechanism in VR learning environment. In: Proceedings of the international conference on innovative technologies and learning. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65884-6_14

Weigand J, Harwood B (2007) Defining graduate education in interior design. J Inter Des 33(2):3–10

Wu PH, Hwang GJ, Milrad M, Ke HR, Huang YM (2012) An innovative concept map approach for improving students’ learning performance with an instant feedback mechanism. Br J Educ Technol 43(2):217–232

Zhu H, Mansor M (2024) Exploring the intersection of virtual reality and interior design: A literature review of emerging trends. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 14(11):1801–1819. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v14-i11/23448

Zuo Q, MaloneBeach EE (2010) A comparison of learning experience, workload, and outcomes in interior design education using a hand or hybrid approach. Fam Consum Sci Res J 39(1):90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-3934.2010.02047.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L., P.W. and W.Z.; software, P.W., Y.L. and D.X.; formal analysis, P.W., Y.L. and W.Z.; writing—review and editing, P.W.; project administration, P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Daegu University (approval number: 20240311) on March 11, 2024. The approval covers all experiments, questionnaires, and interviews involving human participants in this study. The study was officially launched after ethical approval, and no data collection was performed before approval was obtained. The entire research process strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical standards to ensure that the rights, safety, and privacy of all participants were fully protected.

Informed consent

Prior to the commencement of the study on March 14, 2024, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research team provided a clear explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, data usage, and participants’ rights. Consent was obtained in writing after ensuring that participants fully understood the information. This study is non-interventional, and all participants were explicitly informed that their personal information would remain strictly anonymous, data would be used solely for academic purposes, participation was entirely voluntary, and they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. The study did not involve minors or other vulnerable groups.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, P., Zhang, W., Xu, D. et al. From two-dimensional representation to immersive interaction: the VR-driven transformation of interior design pedagogy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06258-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06258-w