Abstract

Tropical convection anomaly could serve as a crucial driver of global atmospheric teleconnections and weather extremes around the world. However, quantifying the dominances of convection anomalies with regional discrepancies, relevant for the variations of global atmospheric circulations, remains challenging. By using a network analysis of observation-based rainfall and ERA5 reanalysis datasets, our study reveals that El Niño-like convection is the most primary rainfall pattern driving the global atmospheric circulation variations. High local concurrences of above-normal rainfall events over equatorial central-eastern Pacific amplify their impacts, even though the most intense rainfall anomalies are observed near the Maritime Continent. Furthermore, we find that the impacts of El Niño-like convection will be tripled by the end of this century, as projected consistently by 23 climate models. Such “rich nodes get richer” phenomenon is probably attributable to the dipolar rainfall changes over the equatorial western-central Pacific. This study highlights the dominant role of El Niño-like convection on the global climate variations, especially under the future changing climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Complex atmospheric circulation variations at global scale can emanate from convection anomalies over the tropics, as an example for global teleconnections in the climate system1,2,3,4. The global conveyance of atmospheric signals triggered by rainfall-related latent heat release could exacerbate extreme weather in other regions including highly populated areas. Directly coupled with the convective activity, the underlying long-lasting sea surface temperature (SST) changes have been recognized as the origin of wide-reaching climate variability and thus used for predictive purposes5,6. In particular, the South Asian summer monsoon tends to be weaker than normal during the El Niño developing summer7,8,9, attributed to associated anomalous Walker circulation10,11. Also, both North and South Americas are influenced by poleward-propagating atmospheric Rossby wave trains, known as the Pacific North American (PNA) and the Pacific South American (PSA) patterns1,12,13,14, in response to anomalous rainfall over the tropical central Pacific (CP) directly linked to El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Similarly, a poleward-propagating wave train toward the Antarctic is induced by the Indian Ocean Dipole15,16. In addition, both the North Atlantic warming17,18 and the Indian Ocean basin warming19,20,21 could modulate climate variations over Southeast Asia and East Asia via eastward-propagating Kelvin waves.

The large-scale teleconnections of tropical ocean-atmosphere coupling are sometimes independent among different oceans since one of them could occur individually22,23,24, but it is more notable that their joint impacts are amplified due to the co-variability of the three tropical oceans25,26,27,28. Therefore, it is of broad interest to study the relative contributions of diverse convection anomalies to global and regional climate variations29,30,31. In particular, taking an index (i.e. a time series) measuring the strength of a certain climate mode as a basis, is commonly adopted for investigating the linear responses through correlation or regression maps. However, this simplified method, based on a few single time series, makes it difficult to reproduce the topological features behind the complex earth system. As reported in previous studies, the commonly used Niño3.4 and Niño3 indices alone are inadequate for representing the complex variations in tropical Pacific SST32,33, such that some crucial characteristics of ENSO’s remote influences are not captured. Furthermore, comparing the teleconnections of different oceans is challenging when the multiple indices are identified in diverse and incompatible ways.

Sensitivity experiments using state-of-the-art climate models are also beneficial for assessing the potential impacts of convection and SST anomalies over various regions3,34,35,36. However, the inherent uncertainties in model parameterizations and the limited resolutions of present climate models may compromise the reliability of the results obtained even in well-designed experiments. For instance, the large biases exhibited by climate models in the equatorial Pacific cold tongue could introduce substantial uncertainties in their skills in simulating ENSO and its global teleconnections37,38,39,40,41,42. In addition, comprehensive ocean-atmosphere coupled experiments using various models are computationally expensive. These emphasize the need for developing a data-based approach suited to assess quantitatively the complex relationships between convection anomalies and atmospheric variations in the observational and reanalysis datasets. In this way, the remote effects of convection anomaly can be quantified over each single grid cell and be compared among different areas.

Complex network analysis has a high potential to uncover complex linkages between abnormal weather events from local to global scales. Previous climate network studies have revealed synchronization features and propagation pathways of extreme rainfall43,44, droughts45, and heatwaves46,47. Moreover, the crucial roles of complex atmospheric circulation patterns on modulating climate extreme teleconnections (i.e. remote simultaneous occurrences) have been emphasized based on network analysis43,44,46,47,48. For instance, the atmospheric Rossby wave trains with a noticeable distance of ~2700 km between high-pressure anomalies (heatwaves) and low-pressure anomalies (cold events) could be captured by network analysis47. Furthermore, propagating atmospheric signals linking tippings between Amazon and Tibetan Plateau49, as well as Arctic activity and mid-latitude weathers50, revealed by network analysis have enhanced our understanding of the complex teleconnections in climate variability.

In this study, we apply a complex network methodology to quantify to what extent the convection anomaly over a grid cell (using a global grid of observational CMAP rainfall51 at a 2.5° × 2.5° resolution and ERA5 reanalysis dataset52 at a 2° × 2° resolution) is linked to global atmospheric circulation variations, called “global climate relevance” hereafter. Considering the more direct linkage between convection and atmospheric circulation, convection is used for constructing climate networks here rather than using SST as in most previous studies (see above). Seven climate networks are constructed based on the temporal similarity between anomalous rainfall and upper tropospheric pressure events at the global scale (see Methods for details). The strength of a link between two grid cells is identified as the number of the concurrent pentads (during the analysis period 1979–2016) when anomalous rainfall events occur over one grid cell and anomalous upper-tropospheric pressure events over the other47 (see Methods for details). Accumulated strengths of all significant links to a specific rainfall grid cell (i.e. in-degree centrality to global circulations) indicate the global climate relevance of the convection anomaly over this grid cell. By using the complex network analysis, the dominance of El Niño-like convection is highlighted in this study. Furthermore, we employ the same kind of analysis onto the model outputs from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)53, and reveal a projected intensification of global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection under the SSP585 and SSP245 scenarios of future global warming.

Results

Observed dominance of El Niño-like convection relevant for global circulation variations

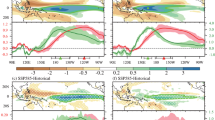

We construct seven climate networks based on the number of concurrent pentads among above-normal rainfall, below-normal rainfall, above-normal upper-tropospheric pressure events, and below-normal upper-tropospheric pressure events (see Methods for details). Through analyzing the in-degree centralities to global circulations of the four convection-circulation networks (see Methods for details), we quantify the global climate relevance of anomalous rainfall events over different areas (Fig. 1). Specifically, the in-degree centralities to global anomalous pressure events indicate to what extent the convection anomaly over a specific grid cell is relevant for global circulation variations. According to our analysis, convective anomalies over the Maritime Continent (MC) and the equatorial CP exhibit the strongest linkage with global circulation variations, as shown by the summed in-degree centralities of the four networks (Fig. 1a).

In-degree centrality to global anomalous pressure events (units: ×10,000) summed for a all four convection-circulation networks, b two networks based on above-normal rainfall events, and c two networks based on below-normal rainfall events. Two networks in (b) include extreme concurrences between (1) above-normal rainfall and high-pressure events, and between (2) above-normal rainfall and low-pressure events, while the other two in (c) between (3) below-normal rainfall and high-pressure events, and between (4) below-normal rainfall and low-pressure events. High-value regions in (a–c) indicate where anomalous rainfall events are highly concurrent with global anomalous atmospheric pressure events at 300 hPa. The Maritime Continent (10°S–10°N, 90°–160°E) and equatorial central Pacific (10°S–10°N, 170°E–120°W) are outlined by the colored boxes in (a–c). The network results are based on pentad-mean CMAP rainfall and ERA5 geopotential height at 300 hPa during 1979–2016.

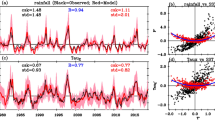

To exhibit the rainfall patterns explicitly, the network results based on above- and below-normal rainfalls are presented separately in the following. Variations in global atmospheric circulation are strongly linked to both the above-normal rainfall over the equatorial CP (Fig. 1b) and the below-normal rainfall over the MC (Fig. 1c). It is important to emphasize that these two anomalous rainfall events are strongly interconnected, rather than occurring independently. Based on the cross-degree centralities in the networks between above-normal and below-normal rainfall events, we find that above-normal rainfall over CP is highly concurrent with below-normal rainfall over MC at the synoptic time scale (Fig. 2a, b). Such west-east dipole of convection anomalies over CP and MC closely resembles the El Niño-like convection pattern observed on interannual time scales3,4. Even though El Niño exhibits remarkable influences on the interannual time scale, the annual frequencies of synoptic convection events over the equatorial Pacific are significantly modulated by El Niño-like SST anomalies, especially for eastern-type El Niño (Fig. 2c, d; see Supplementary Table S1). This is because the slowly evolving SST anomalies related to ENSO provide a persistent large-scale background that can modulate convection events on synoptic time scales54,55. Sub-seasonal systems, such as the Madden-Julian oscillation (MJO), may also modulate the convection activities over MC. However, the cumulative effects of this dipolar pattern exhibit a more pronounced relationship with El Niño. On the other hand, previous studies proposed that ENSO can also significantly modulate the atmospheric convection on sub-seasonal timescales, including the MJO-related convection56,57,58. Therefore, we recognize the above-normal rainfall over CP and the below-normal rainfall over MC as El Niño-like convection in this study.

Above-normal rainfalls over equatorial central Pacific (CP) and below-normal rainfalls over Maritime Continent (MC) recognized as El Niño-like convection. Cross-degree centralities of a below-normal rainfall events inside above-normal rainfall events over equatorial CP, and b above-normal rainfall events inside below-normal rainfall events over MC. Interannual correlation coefficients of sea surface temperature onto c annual frequency of above-normal rainfalls over CP, and d annual frequency of below-normal rainfalls over MC. High-value regions in (a, b) indicate where anomalous rainfall events are highly concurrent with the opposite rainfall events over the corresponding boxes. All plotted correlation coefficients in (c, d) are significant (p < 0.05). The equatorial CP (10°S–10°N, 170°E–120°W) and MC (10°S–10°N, 90°–160°E) are outlined by the colored boxes in (a, c) and (b, d), respectively.

Highly connected to global circulations, El Niño-like convection is equivalent to the “rich nodes” in network science, reaching the highest global climate relevance around the world (Fig. 1b, c). In contrast, the convections over the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean show relatively weaker connections with global circulations (Fig. 1b, c). The occurrences of above-normal rainfall over MC and below-normal rainfall over CP are also closely related to La Niña-like convection (see Supplementary Fig. S1). These findings highlight the essential modulations of the tropical Pacific ocean-atmosphere coupling on global climate variations. In addition, it is noteworthy that the dominant global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection does not change when the ERA5 precipitation is used (see Supplementary Fig. S2), or anomalous convection events are identified based on outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) anomaly (see Supplementary Fig. S3), which is a commonly used indicator of the strength of tropical convective activity.

How is the El Niño-like convection significantly linked to the variations in global atmospheric circulation? Network-derived out-degree centralities from the Pacific anomalous rainfalls exhibit global teleconnection patterns related to El Niño (see Supplementary Fig. S4a, b): (1) east-west shift of the tropical Walker circulation, and (2) poleward-propagating Rossby wave trains including the PNA and PSA patterns. Similar but less significant results obtained from the regression maps onto Pacific pentad-mean rainfall anomaly (see Supplementary Fig. S4c, d), indicate a reliable physical representation based on the network metrics used in this study. As the physical mechanisms of ENSO teleconnections have been well established in the previous literature3,13,14, they are not the focus of this study.

Pronounced climate relevance linked to high local concurrences of anomalous rainfall events

Although previous studies have reported the pronounced impacts of El Niño on the global climate, the strong climate relevance of anomalous convection over equatorial CP and MC remains to be thoroughly understood. For both above-normal and below-normal rainfall events, the most intense precipitation anomalies are observed near the maritime continent (Fig. 3a, b). The key region (i.e. equatorial CP) of above-normal rainfall events is located farther east than the areas with strong rainfall anomalies. With relatively weak rainfall anomalies, how can above-normal rainfall events over CP strongly modulate the global atmospheric circulation variations? Based on the results of network between anomalous rainfalls, we find that above-normal rainfalls are likely to occur simultaneously within 1500 km (Fig. 3c). Therefore, these large-scale concurrent events over the CP exert pronounced impacts, even though each event is of moderate intensity. On the other side of the Pacific, both the high intensities and local concentrations of below-normal events over the equatorial MC contribute to the region’s high climate relevance (Fig. 3b, d).

Averaged precipitation anomalies (units: mm day−1) of a all above-normal rainfall events, and b below-normal rainfall events, during the period 1979–2016. Degree centralities of c above-normal rainfall events inside above-normal rainfall events over surrounding areas (<1500 km), and d below-normal rainfall events inside below-normal rainfall events over surrounding areas (<1500 km). High-value regions in (c, d) indicate where the local occurrences of anomalous rainfall events within 1500 km are highly simultaneous. Areas are masked and dotted in (c) and (d), where the absolute values of average precipitation anomalies are less than 3 mm day−1 for above-normal rainfall events, and less than 2 mm day−1 for below-normal rainfall events, respectively. The equatorial central Pacific (10°S–10°N, 170°E–120°W) and Maritime Continent (10°S–10°N, 90°–160°E) are outlined by the red boxes in (a, c) and (b, d), respectively.

Compared with El Niño-like convection, the modulations of La Niña-like convections are weaker, especially for the out-degree centralities from the below-normal rainfalls over CP (see Supplementary Fig. S5), probably due to their weak intensity and low local concurrences (Fig. 3b, d). This might be related to the weaker precipitation anomalies over CP and MC induced by La Niña than those caused by El Niño due to the asymmetry in ENSO amplitude59,60 and the nonlinear response of convection to SST anomalies61,62,63. Pantropical climate interactions among the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans can also be observed in the network analysis (see Supplementary Figs. S6, S7). In addition, the relatively high global relevance of extratropical North Atlantic rainfalls compared with other extratropical areas also exhibits a strong linkage with the circum-global teleconnections in the Northern Hemisphere, but a very weak linkage is detected in the Southern Hemisphere (see Supplementary Fig. S8). The high global climate relevance of tropical convection is probably attributed to its modulations on the climate variations in both hemispheres, instead of either hemisphere.

Projected intensified global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection in the future

Before investigating the future changes projected by multiple CMIP6 models, we examine the models’ performance in simulating the historical-period relationships between El Niño-like convection and global circulation variations. The multi-model mean of 23 models could reliably simulate the high concurrences between above-normal rainfalls over the equatorial CP and global anomalous pressure events, although it slightly underestimates the significance of the below-normal rainfalls over MC (see Supplementary Fig. S9a, b). Overall, the CMIP6 models could reproduce the dominant global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection. Furthermore, the east-west shift of the tropical Walker circulation and the PNA and PSA patterns also exhibit a significant linkage with El Niño-like convection in the historical simulations during 1979–2014 (see Supplementary Fig. S9c, d).

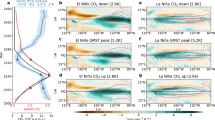

It is remarkable that strong increases in annual rainfall are projected over the equatorial CP by most (>82%) of the 23 CMIP6 models at the end of the 21st century under the future SSP585 scenario (Fig. 4a). In contrast, rainfall decreases slightly over the MC. Such dipolar rainfall changes are linked to the El Niño-like SST changes in the tropical Pacific64,65,66, with a significant correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) among the models (Fig. 4b, c). The zonal mean of SST changes is removed to exclude the effects of relatively uniform warming by climate change66. Such relative SST changes can also better capture the changes in SST-convection relationship, since the SST threshold for triggering deep convection is approximately equal to the tropical-mean SST67,68. Therefore, the sensitivity of atmospheric deep convection to SST anomalies is expected to increase over the equatorial central-eastern Pacific due to the El Niño-like SST changes64,65.

Future changes are calculated as the differences between the period 2070–2099 under the SSP585 scenario and the period 1981–2010 under the historical simulations. Future changes in the multi-model mean of 23 CMIP6 models for a annual rainfall (units: mm day−1), and b eddy sea surface temperature (SST), equal to SST removing zonal mean (units: K). Hatched areas in (a, b) show where at least 19 models (>82% of the total 23 models) project the changes with the same signs. c Inter-model regressions of eddy SST changes onto rainfall changes over the equatorial central Pacific (CP). Significant regression coefficients at the 95% confidence level are hatched in (c). Time series of the multi-model averaged number of d above-normal rainfall events averaged over the equatorial CP, and e below-normal rainfall events averaged over the Maritime Continent during the period 1979–2099 under the historical simulations (1979–2014) and SSP585 scenario (2015–2099). Gray shadings in (d, e) indicate the range of one standard deviation deviated from the multi-model mean of the 23 models. The equatorial CP (10°S–10°N, 170°E–120°W) is outlined by the red box in (a).

As a result of zonally asymmetric changes in Pacific SST and annual-mean convection, above-normal rainfall events are projected to increase significantly over the equatorial CP (Fig. 4d). Similarly, significant but weaker upward trends are also projected for the below-normal rainfall events over the equatorial MC in this century (Fig. 4e). According to previous studies69,70, ENSO variability is projected to become stronger in the future. This also indicates increases in anomalous rainfall events over CP and MC due to enhanced rainfall variability. Overall, El Niño-like convection is projected to intensify continuously until the end of this century, in agreement across most (>82%) of the 23 climate models.

Will the intensified El Niño-like convection encourage a stronger global climate relevance of the Pacific convection? The most significant projected changes in the global climate relevance (i.e. in-degree centralities to global circulations) are located on both the MC and the CP (Fig. 5a, b). Specifically, El Niño-like convection exhibits a stronger linkage with global circulation variations in the long-term future (2070–2099) under the SSP585 scenario, compared with the historical period 1981–2010 (Fig. 5a, b). This feature indicates that powerful El Niño-like convection is projected to become more powerful in the warmer future, in agreement with more than 82% of the models. In particular, the intensified out-degree centralities from both the above-normal rainfalls over equatorial CP and the below-normal rainfalls over MC (Fig. 5a, b) are consistent with the stronger modulations of El Niño-like convection on the west-east shifts of the tropical Walker circulations and the poleward propagating atmospheric Rossby wave trains (Fig. 5c, d). This is probably ascribed to the increases in accumulated impacts of Pacific convection anomalies directly linked to the increases in the above-normal rainfalls over equatorial CP and the below-normal rainfalls over MC (Fig. 4d, e). Previous study also emphasizes that future El Niño-like SST and convection changes aggravate the heat-dome-like circulations over western Asia and western North America through the tropical Walker circulations and PNA-related wave trains66. An increase in Pacific Meridional Mode (PMM) events has been revealed to be projected with ENSO events66,71. However, the associated changes in the global impacts from the subtropical North Pacific are not as pronounced as those from the tropical Pacific (Fig. 5a, b). Similar but weaker intensifications of the global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection are projected for both the long-term future (2070–2099) under the SSP245 scenario (see Supplementary Fig. S10) and the mid-term future (2036–2065) under the SSP585 scenario (see Supplementary Fig. S11).

Projected changes are calculated as the differences between the period 2070–2099 under the SSP585 scenario and the period 1981–2010 under the historical simulations. Projected changes in the in-degree centrality to global anomalous pressure events (units: ×1000) summed for a two networks based on above-normal rainfall events, and b two networks based on below-normal rainfall events. Projected changes in out-degree centrality differences (shadings; units: ×100) between high-pressure-included network and low-pressure-included network, from c above-normal rainfalls over the equatorial central Pacific (CP), and from d below-normal rainfalls over the Maritime Continent (MC). Hatched areas in (a–d) show where at least 19 models (>82% of the total 23 models) project the changes with the same signs. The MC (10°S–10°N, 90°–160°E) and equatorial CP (10°S–10°N, 170°E–120°W) are outlined by red boxes in (a–d).

Furthermore, the in-degree centralities to global circulations of the convection nodes in the four convection-circulation networks exhibit a distribution close to a “power-law” distbution43, when the in-degree centrality to global circulations is larger than 80,000 (Fig. 6). In the future, the proportions of grid cells with high global climate relevance are projected to increase compared with the historical simulations, suggesting “rich nodes get richer” in the future. Specially, the changes in above-normal rainfall nodes are significantly greater than those in below-normal rainfall nodes, which is proably due to more rapid increases in both anomalous rainfall events and SST over CP compared with MC (Fig. 4). The El Niño-like convection with anomalous rainfall events over MC and CP, is identified as the key areas with “rich” grid cells and high global climate relevance. Specially, the in-degree centralities to global circulations of above-normal rainfalls over CP (29.1) and the below-normal rainfalls over MC (12.5) reach relatively high values compared with other regions in the historical simulations, and they are projected to be doubled and even tripled by the end of the century under the SSP585 scenario (Fig. 6b, c).

Probability density functions (PDF) in in-degree centralities to global circulations in the historical simulations (1981–2010; orange solid lines), mid-term future (2036–2065; pink dashed lines), and long-term future (2070–2099; red dashed lines) under the SSP585 scenario summed for a all four convection-circulation networks, b two networks based on above-normal rainfall events, and c two networks based on below-normal rainfall events. The units for x-axis are ×10,000, while the units for y-axis are 1. Orange vertical thick lines in (c) and (d) indicate historically simulated averaged in-degree centralities to global circulations for above-normal rainfalls over the equatorial central Pacific (CP) and for below-normal rainfalls over the Maritime Continent (MC), respectively. Pink and red vertical thick lines in (c, d) are similar to the orange ones, but for the projected in-degree centralities to global circulations during the period 2036–2065 and 2070–2099 under the SSP585 scenario, respectively.

Discussion

Our complex network analysis improves understanding and predicting variations in global atmospheric circulation and potentially related climate extremes, as largely driven by El Niño-like convection. In additional to detecting the strongest impacts of El Niño-like convection, we also find that it is likely to intensify in the future, as consistently projected by 23 CMIP6 climate models under the SSP585 and SSP245 scenarios. In both observational data and model output, above-normal rainfalls over equatorial CP and below-normal rainfalls over MC are identified as the primary rainfall patterns (the richest grid cells) relevant for global circulation variations, indicating the dominance of El Niño-like convection for these variations. Intensified global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection projected by the end of the 21st century, equivalent to ‘rich nodes get richer’ phenomenon in network science, is attributable to future El Niño-like SST changes in the Pacific.

We note some limitations of this study, as follows. We analyze the simultaneous occurrences between anomalous rainfall and pressure events, but do not consider lead-lag relationships. Further research using advanced network-based machine learning approaches including time delays, may improve our understanding and eventually assist in sub-seasonal forecasts of global weather changes72. In addition, the climate networks analyzed in this study are based on anomalous rainfall events rather than anomalous SST events. As shown in Figs. 2c–d and 4c, El Niño-like convection is closely linked to the underlying SST anomalies. Tropical SST anomalies possess a long memory and a high potential to predict global climate variations5,6. A thorough network analysis of the synoptic synchronizations between anomalous SST events (including oceanic heatwaves and cold events) and global terrestrial weather extremes is thus desirable for further scientific studies, and it may improve the ability to predict extreme events that possibly lead to high-risk disasters66.

Methods

Datasets

Pentad-mean rainfall derived from the CMAP precipitation dataset51, with an original horizontal resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°, is analyzed in this study. Hourly geopotential height at 300 hPa, precipitation, and OLR derived from the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) datasets52, are interpolated to 2° × 2°, and averaged into 5-day mean before further analysis. The study period for observational analysis is limited to 73 pentads × 38 years (1979–2016).

In addition, daily precipitation and geopotential height at 250 hPa from the CMIP6 historical simulations53 during 1979–2014, and SSP585 and SSP245 scenarios during 2015–2100 are examined in this study. The SSP585 (SSP245) scenario is the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5 (2) climate change scenario with a climate forcing of 8.5 (4.5) W m−2. The output of each model simulation is averaged into 5-day means and interpolated into 5° × 5° before network analysis. Twenty-three CMIP6 models are included in this study: ACCESS-CM2, BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, CESM2-WACCM, EC-Earth3, EC-Earth3-Veg, FGOALS-g3, GFDL-CM4, HadGEM3-GC31-LL, HadGEM3-GC31-MM, IITM-ESM, INM-CM4-8, INM-CM5-0, IPSL-CM6A-LR, KACE-1-0-G, MIROC6, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, MRI-ESM2-0, NorESM2-LM, NorESM2-MM, TaiESM1, and UKESM1-0-LL (see Supplementary Table 2). HadGEM3-GC31-MM is not provided under the SSP245 scenario, and therefore, only 22 models are included under this scenario.

Definition of anomalous weather events

To ensure that the number of anomalous events at each grid cell is approximately equal, we identify an anomalous event based on the 90th or 10th percentile thresholds of the standardized anomalies. The standardized anomaly for each pentad is calculated by subtracting the climatology of the corresponding pentads during the period 1981–2010, and then dividing by the standard deviations of same corresponding pentads. For example, precipitation anomaly on the 21st pentad is obtained by subtracting the climate mean and then dividing by the standard deviations of the values on the 21st pentad during 1981–2010.

An above-normal rainfall event is identified when the standard anomaly of pentad-mean precipitation is greater than the 90th percentile threshold in totally 2774 pentads during 1979–2016, while a below-normal rainfall event is recognized when the standard anomaly is smaller than the 10th percentile threshold. Similarly, a high-pressure (low-pressure) event is picked out when the standard anomaly of the eddy geopotential height at 300 hPa (H300) is greater than the 90th (smaller than the 10th) threshold. Eddy H300 is the deviation of H300 from the zonal mean. For each pentad, the climate mean and the standard deviation are derived from a 30-year time series (1981–2010).

Network analysis

There are seven kinds of networks: (1) above-normal rainfall and high-pressure events, (2) above-normal rainfall and low-pressure events, (3) below-normal rainfall and high-pressure events, and (4) below-normal rainfall and low-pressure events, (5) above-normal rainfall and above-normal rainfall events, (6) below-normal rainfall and below-normal rainfall events, and (7) above-normal rainfall and below-normal rainfall events. For each network \(i\), the strength of a link between grid cells \(a\) and \(b\) is denoted as \({L}_{i,\,(a,{b})}\). It is determined as the total number of concurrent pentads when an anomalous rainfall event occurs over \(a\) and an anomalous pressure event occurs over \(b\) simultaneously, similar to previous studies47. In this study, when counting the number of concurrent pentads between anomalous events over the two grid cells, we do not consider time lag (i.e. time lag = 0) to simplify the computation process. We shuffle the time series of pentad-mean events (presence as 1 or absence as 0) 1000 times for each grid cell, and then calculate the 99th percentile of \({L}_{i,\,(a,{b})}\) for each pair of grid cells \((a,b)\) from the shuffled time series. Then, we perform a significant test for the links in the seven concurrence networks. When the real \({L}_{i,\,(a,{b})}\) is lower than the 99th percentile threshold derived from the shuffle data, this link is identified as nonsignificant and will be removed (i.e. \({L}_{i,\,(a,{b})}\) being set to 0). In addition, if the \({L}_{i,\,(a,{b})}\) lower than 5, it is recognized as a weak link and will also be removed.

Degree centrality47 is used to describe the topological characteristics of convection-atmospheric circulation relationship in this study. In-degree centrality to global circulation variations (i.e. global anomalous pressure events) is the sum of strength of all significant links to the grid cells:

Here, \({L}_{m,\,(a,{b})}\) is the link strength of the network with high-pressure events over grid cell \(b\), while \({L}_{n,\,(a,{b})}\) is the link strength of the network with low-pressure events over grid cell \(b\). High in-degree centralities to global circulation variations indicate the key areas of rainfall anomalies relevant for global circulation variations. Similarly, out-degree centrality from above-normal rainfalls over the equatorial CP (below-normal rainfalls over the MC) is the sum of strength of all significant links to the grid cells within the corresponding region:

In particular, \({L}_{i,\,(a,{b})}\) is the link strength of the network with above-normal (below-normal) rainfalls over grid cell \(a\), for network \(i\).

Sensitivity test

We also use ERA5 data to recognize anomalous rainfall events during the period 1979–2023, and the global climate relevance of El Niño-like convection is also pronounced in ERA5 data (see Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition to the rainfall data, OLR from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset is also used to measure the strength of the convective activity. An above-normal convection event is identified when standardized pentad-mean OLR anomaly is smaller than the 10th percentile threshold, while a below-normal convection event is recognized when standardized OLR anomaly is larger than the 90th percentile threshold. Similar network analysis is employed for anomalous convection events based on OLR, as the network analysis for anomalous rainfall events. The network results for OLR-based convection are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The main conclusion is not sensitive to the definition of anomalous convection events, and the El Niño-like convection reaches the highest dominances relevant for the global atmospheric circulation variations (see Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3).

Inter-pentad regression

Pentad-mean time series of standardized CMAP rainfall and ERA5 eddy H300 are derived after removing the climate mean of 1981–2010 and divided by the standard deviation of 1981–2010. In the following, we obtain the two pentad-mean time series of standardized rainfall averaged over the equatorial CP (10°S–10°N, 170°E–120°W) and the MC (10°S–10°N, 90°–160°E). Then we calculate regression coefficients of global pentad-mean eddy H300 onto these two pentad-mean time series (see Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). The regression coefficients are significant, when the corresponding correlation coefficients exceed the 95% confidence level based on the Student’s t test. The degree of freedom for the significant test is defined as the minimum of the two effective degrees of freedom of the two corresponding pentad-mean time series. The effective degrees of freedom is the number of independent values in a series of correlated values.

Data availability

The ERA5 multi-level variables and the CMAP precipitation dataset could be freely downloaded from https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6 and https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cmap.html, respectively. The outputs of CMIP6 simulations could be freely obtained from https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/.

Code availability

The codes used to generate the results of this study are available on request from the authors.

References

Horel, J. D. & Wallace, J. M. Planetary-scale atmospheric phenomena associated with the Southern Oscillation. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 813–829 (1981).

Jin, F. & Hoskins, B. J. The direct response to tropical heating in a baroclinic atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 52, 307–319 (1995).

Hoerling, M. P. & Kumar, A. Atmospheric response patterns associated with tropical forcing. J. Clim. 15, 2184–2203 (2002).

Alexander, M. A. et al. The atmospheric bridge: the influence of ENSO teleconnections on air-sea interaction over the global oceans. J. Clim. 15, 2205–2231 (2002).

Trenberth, K. E. et al. Progress during TOGA in understanding and modeling global teleconnections associated with tropical sea surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 103, 14291–14324 (1998).

Shukla, J. et al. Dynamical seasonal prediction. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 81, 2593–2606 (2000).

Rasmusson, E. M. & Carpenter, T. H. The relationship between eastern equatorial Pacific sea surface temperatures and rainfall over India and Sri Lanka. Mon. Weather Rev. 111, 517–528 (1983).

Webster, P. J. & Yang, S. Monsoon and ENSO: selectively interative systems. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 118, 877–926 (1992).

Lin, S. et al. Atmospheric–oceanic processes over the Pacific involved in the effects of the Indian summer monsoon on ENSO. J. Clim. 36, 6021–6043 (2023).

Ju, J. & Slingo, J. The Asian summer monsoon and ENSO. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 121, 1133–1168 (1995).

Kumar, K. K., Rajagopalan, B., Hoerling, M., Bates, G. & Cane, M. Unraveling the mystery of Indian monsoon failure during El Niño. Science314, 115–119 (2006).

Karoly, D. J. Southern hemisphere circulation features associated with El Niño-Southern Oscillation events. J. Clim. 2, 1239–1252 (1989).

Feldstein, S. B. Fundamental mechanisms of the growth and decay of the PNA teleconnection pattern. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 128, 775–796 (2002).

Mo, K. C. & Higgins, R. W. The Pacific-South American modes and tropical convection during the Southern Hemisphere winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 1581–1596 (1998).

Cai, W., van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. Teleconnection pathways of ENSO and the IOD and the mechanisms for impacts on Australian rainfall. J. Clim. 24, 3910–3923 (2011).

Nuncio, M. & Yuan, X. The influence of the Indian Ocean dipole on Antarctic sea ice. J. Clim. 28, 2682–2690 (2015).

Lu, R. & Dong, B. Impact of Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies on the summer climate in the western North Pacific during 1997–1998. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, 1–11 (2005).

Rong, X. Y., Zhang, R. H. & Li, T. Impacts of Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies on Indo-East Asian summer monsoon-ENSO relationship. Chin. Sci. Bull. 55, 2458–2468 (2010).

Yang, J., Liu, Q., Xie, S. P., Liu, Z. & Wu, L. Impact of the Indian Ocean SST basin mode on the Asian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 1–5 (2007).

Li, S., Lu, J., Huang, G. & Hu, K. Tropical Indian Ocean basin warming and East Asian Summer Monsoon: a multiple AGCM study. J. Clim. 21, 6080–6088 (2008).

Xie, S. P. et al. Indian Ocean capacitor effect on Indo-Western pacific climate during the summer following El Niño. J. Clim. 22, 730–747 (2009).

Hong, C. C., Lu, M. M. & Kanamitsu, M. Temporal and spatial characteristics of positive and negative Indian Ocean dipole with and without ENSO. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, 1–15 (2008).

Sun, S., Lan, J., Yue Fang, T. & Gao, X. A triggering mechanism for the Indian Ocean dipoles independent of ENSO. J. Clim. 28, 5063–5076 (2015).

Handoh, I. C., Matthews, A. J., Bigg, G. R. & Stevens, D. P. Interannual variability of the tropical Atlantic independent of and associated with ENSO: Part I. The North Tropical Atlantic. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 1937–1956 (2006).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z., Saji, N. H. & Yamagata, T. Individual and combined influences of ENSO and the Indian Ocean Dipole on the Indian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 17, 3141–3155 (2004).

Wang, J.-Z. & Wang, C. Joint boost to super El Niño from the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. J. Clim. 34, 4937–4954 (2021).

Zhang, P., Duan, A. & Hu, J. Combined effect of the Tropical Indian Ocean and Tropical North Atlantic Sea surface temperature anomaly on the Tibetan Plateau precipitation anomaly in late summer. J. Clim. 35, 3899–3918 (2022).

Cai, W. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav4236 (2019).

Lee, S. K., Wang, C. & Mapes, B. E. A simple atmospheric model of the local and teleconnection responses to tropical heating anomalies. J. Clim. 22, 272–284 (2009).

Cai, F., Yang, S., Wang, Z. & Hua, W. Quantitative study of the interannual variability of South Asian summer monsoon rainfall regulated by SST. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3457–3468 (2021).

Peng, P., Wang, W. & Kumar, A. Seasonal tropical–extratropical teleconnections originating from tropical rainfall modes independent of the Niño-3.4 Index in Northern Winters. J. Clim. 36, 5713–5728 (2023).

Ren, H. L. & Jin, F. F. Niño indices for two types of ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 2–6 (2011).

Hu, C. et al. Reinspecting two types of El Niño: a new pair of Niño indices for improving real-time ENSO monitoring. Clim. Dyn. 47, 4031–4049 (2016).

Ngar-Cheung, L. & Nath, M. J. A modeling study of the relative roles of tropical and extratropical SST anomalies in the variability of the global atmosphere-ocean system. J. Clim. 7, 1184–1207 (1994).

Fletcher, C. G. & Cassou, C. The dynamical influence of separate teleconnections from the Pacific and Indian Oceans on the Northern Annular Mode. J. Clim. 28, 7985–8002 (2015).

Chen, J., Hu, X., Yang, S., Lin, S. & Li, Z. Influence of convective heating over the maritime continent on the West Antarctic Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 1–10 (2022).

Latif, M. et al. ENSIP: The El Niño simulation intercomparison project. Clim. Dyn. 18, 255–276 (2001).

Guilyardi, E. et al. Understanding El Niño in ocean-atmosphere general circulation models: progress and challenges. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 90, 325–340 (2009).

Kim, S. T., Cai, W., Jin, F. F. & Yu, J. Y. ENSO stability in coupled climate models and its association with mean state. Clim. Dyn. 42, 3313–3321 (2014).

Bayr, T., Lübbecke, J. F., Vialard, J. & Latif, M. Equatorial Pacific Cold Tongue Bias degrades simulation of ENSO Asymmetry due to underestimation of strong Eastern Pacific El Niños. J. Clim. 1, 6167–6182 (2024).

Lin, S., Dong, B., Yang, S., He, S. & Hu, Y. Causes of diverse impacts of ENSO on the southeast Asian summer monsoon among CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 37, 419–438 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. CMIP6 Models Underestimate ENSO Teleconnections in the Southern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110738 (2024).

Boers, N. et al. Complex networks reveal global pattern of extreme-rainfall teleconnections. Nature 566, 373–377 (2019).

Li, K. et al. Key propagation pathways of extreme precipitation events revealed by climate networks. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–8 (2024).

Mondal, S., K Mishra, A., Leung, R. & Cook, B. Global droughts connected by linkages between drought hubs. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–13 (2023).

Cai, F., Liu, C., Yang, S., Deng, K. & Kurths, J. Linkage between European and East Asian heatwaves on synoptic scales. J. Trop. Meteorol. 30, 97–105 (2024).

Cai, F. et al. Sketching the spatial disparities in heatwave trends by changing atmospheric teleconnections in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 15, 8012 (2024).

Fan, J., Meng, J., Ashkenazy, Y., Havlin, S. & Schellnhuber, H. J. Network analysis reveals strongly localized impacts of El Niño. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 7543–7548 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Teleconnections among tipping elements in the Earth system. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 67–74 (2023).

Meng, J., Fan, J., Bhatt, U. S. & Kurths, J. Arctic weather variability and connectivity. Nat. Commun. 14, 6574 (2023).

Xie, P. & Arkin, P. A. Global precipitation: a 17-year monthly analysis based on gauge observations, satellite estimates, and numerical model outputs. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 78, 2539–2558 (1997).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Yoshida, S., Morimoto, T., Ushio, T. & Kawasaki, Z. ENSO and convective activities in Southeast Asia and western Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 1–6 (2007).

Yang, G. Y. & Hoskins, B. ENSO impact on Kelvin waves and associated tropical convection. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 3513–3532 (2013).

Hendon, H. H., Zhang, C. & Glick, J. D. Interannual variation of the Madden-Julian oscillation during austral summer. J. Clim. 12, 2538–2550 (1999).

Chen, X., Ling, J. & Li, C. Evolution of the Madden-Julian oscillation in two types of El Niño. J. Clim. 29, 1919–1934 (2016).

Wang, L., Li, T., Chen, L., Behera, S. K. & Nasuno, T. Modulation of the MJO intensity over the equatorial western Pacific by two types of El Niño. Clim. Dyn. 51, 687–700 (2018).

Burgers, G. & Stephenson, D. B. The “normality” of El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 1027–1030 (1999).

Hoerling, M. P., Kumar, A. & Zhong, M. El Niño, La Niña, and the nonlinearity of their teleconnections. J. Clim. 10, 1769–1786 (1997).

Lin, S. et al. Attribution of the seasonality of atmospheric heating changes over the western tropical Pacific with a focus on the spring season. Clim. Dyn. 58, 2575–2592 (2022).

Graham, N. E. & Barnett, T. P. Sea surface temperature, surface wind divergence, and convection over tropical oceans. Science. 238, 657–659 (1987).

Lau, K. M., Wu, H. T. & Bony, S. The role of large-scale atmospheric circulation in the relationship between tropical convection and sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 10, 381–392 (1997).

Huang, P. & Xie, S. Mechanisms of change in ENSO-induced tropical Pacific rainfall variability in a warming climate. Nat. Geosci. 8, 922–927 (2015).

Lin, S., Dong, B. & Yang, S. Enhanced impacts of ENSO on the southeast Asian summer monsoon Under global warming and associated mechanisms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, 1–11 (2024).

Cai, F. et al. Pronounced spatial disparity of projected heatwave changes in the Northern Hemisphere linked to heat domes and soil moisture-temperature coupling. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 225 (2024).

Vecchi, G. A. & Soden, B. J. Effect of remote sea surface temperature change on tropical cyclone potential intensity. Nature 450, 1066–1070 (2007).

Johnson, N. C. & Xie, S. P. Changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection. Nat. Geosci. 3, 842–845 (2010).

Lopez, H., Lee, S. K., Kim, D., Wittenberg, A. T. & Yeh, S. W. Projections of faster onset and slower decay of El Niño in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–13 (2022).

Hong, J. S. et al. Projected increase in ENSO-induced US winter extreme hydroclimate events in SPEAR large ensemble simulation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 1–10 (2025).

Fan, H., Yang, S., Wang, C., Wu, Y. & Zhang, G. Strengthening amplitude and impact of the Pacific meridional mode on ENSO in the warming climate depicted by CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 35, 5195–5213 (2022).

Trok, J. T., Barnes, E. A., Davenport, F. V. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Machine learning-based extreme event attribution. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl3242 (2024).

Acknowledgements

S.Y. is supported by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (Grant 2020B0301030004), the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (SML2023SP209), and the Guangdong Province Key Laboratory for Climate Change and Natural Disaster Studies (2023B1212060019). X.J. is supported by the Youth Innovation Team of China Meteorological Administration “Climate change and its impacts in the Tibetan Plateau” (CMA2023QN16). F.C. and Z.S. are supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.C., S.L., S.Y., and J.K. conceived and designed the study. F.C. conducted the analysis. F.C. and S.L. drafted the manuscript. D.G., S.Y., X.J., Z.S., and J.K. provided comments and revised the manuscript. F.C., S.L., D.G., S.Y., X.J., Z.S, and J.K. discussed the scientific interpretation of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, F., Lin, S., Gerten, D. et al. Intensified dominance of El Niño-like convection relevant for global atmospheric circulation variations. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01140-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01140-7