Abstract

This study evaluates the potential of oral rinse-derived and plasma circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) in HPV-negative oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), where early recurrence occurs in a significant proportion of patients, contributing to poor prognosis. Analysis of paired tissue, oral rinse, and plasma samples from 123 patients revealed ctDNA detection rates of 94.3% in oral rinse and 80.5% in plasma samples. Combined testing improved mutation detection sensitivity to 48.6%. A machine learning model integrating seven mutated genes (TP53, TERT, IKZF1, EP300, MYC, EGFR, PIK3CA) and clinical factors demonstrated robust prediction of recurrence (validation AUC: 0.854) and survival outcomes. Integration of pretreatment plasma ctDNA status further enhanced predictive performance. In longitudinal analysis, ctDNA detected recurrence approximately four months before clinical manifestation. These findings suggest that integrated ctDNA analysis offers improved mutation profiling and outcome prediction, potentially enabling earlier interventions in OSCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) constitutes a predominant subtype of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), with ~90% of cases being HPV-negative, occurring mainly in Asian populations1. Globally, OSCC accounted for 377,713 new cases and 117,757 deaths in 20212. Although the incidence of HPV-negative disease is decreasing, its prognosis is significantly worse than that of HPV-positive disease3.

This discrepancy is largely attributed to the absence of reliable biomarkers for HPV-negative OSCC, essential for developing treatment plans and monitoring therapeutic responses4. Currently, the diagnosis and surveillance of OSCC are primarily based on clinical manifestations and radiological examinations. However, the process of early detection of recurrent disease is significantly challenging, especially due to micro metastases in lymph nodes and fibrosis or inflammation caused by radiation therapy or surgery5. These factors can obscure the identification of residual or recurrent tumor tissue, leading to delays in accurate detection6.

Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA), a subset of cfDNA, is released into the bloodstream from apoptotic or necrotic tumor cells and carries tumor-specific genetic alterations. Unlike traditional biopsies, ctDNA reflects tumor heterogeneity more accurately, enhancing the detection of mutations relevant to targeted therapies7. As a critical component of liquid biopsies, ctDNA offers high sensitivity and specificity for monitoring tumor burden, assessing treatment efficacy, and detecting relapse or metastasis, thereby enabling personalized treatment strategies8.

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of liquid biopsy in HNSCC management9,10. Multiple studies have shown that ctDNA detection precedes the clinical manifestation of disease recurrence, offering opportunities for early intervention11,12. Moreover, integrating different sample types has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance detection sensitivity13. For instance, Wang et al. reported that combining oral rinse and plasma samples increased detection rates compared to single-sample testing, with detection patterns varying by clinical stage and tumor location14. That finding was further supported by Ahn et al., who demonstrated improved sensitivity when combining oral rinse and plasma analysis in HNSCC patients15. Those studies highlight the complementary nature of different liquid biopsy samples, yet comprehensive mutation profiling and systematic evaluation of their clinical utility in HPV-negative OSCC remain limited.

Results

Characteristic of the study cohort and experimental design

We enrolled 123 HPV-negative OSCC patients (65 males and 58 females; median age 58 years, range 38–78 years). Among these patients, 68 were diagnosed with early-stage (I/II) and 55 with advanced-stage (III/IV) disease. The primary tumors were predominantly located on the tongue and gingiva, accounting for 61.8% of the cases, followed by occurrences on the buccal mucosa and palate. To comprehensively profile mutations and evaluate their clinical utility, we designed a multi-phase study using a targeted 551-gene NGS panel (Supplementary Data 1). In the discovery phase, we analyzed all patients’ paired tissue, oral rinse, and plasma samples at baseline. Additionally, we conducted longitudinal monitoring in a subset of 30 patients to track disease progression. Baseline characteristics and treatment methods are detailed in Table 1, and the study design and workflow are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Comprehensive mutation profiling across tissue and liquid biopsy samples

In tumor tissue analysis, we identified mutations in all 123 tissue samples, with a median of 10 mutations per sample (range: 2–21). A total of 1284 mutations involving 160 genes were identified in the gDNA of the tumor tissues. The top four highly mutated genes were TP53, TERT, MYC, and PIK3CA, with mutation frequencies of 60.1% (74/123), 50.4% (62/123), 43.1% (53/123), and 39.8% (49/123), respectively (Supplementary Data 2). To validate our findings in an independent cohort, we analyzed mutation data from TCGA-HNSCC database. Within the 508 HNSCC patients with available SNV data, we observed that TP53 mutations occurred at a frequency of 69.3% (352/508), comparable to our cohort (60.1%). However, we noted substantially lower frequencies for EP300 (7.5%, 38/508), IKZF1 (1.4%, 7/508), and particularly TERT mutations (0.6%, 3/508) compared to our findings. Analysis of CNV data revealed notably higher amplification frequencies in the TCGA cohort for PIK3CA (77.1%, 374/485), MYC (76.7%, 372/485), and EGFR (56.7%, 275/485) than in our study population. These differences may be partially attributed to the higher proportion of advanced-stage disease in the TCGA cohort (77.3%, 375/485), as well as potential variations in detection methodologies and population characteristics.

In liquid biopsy analysis, ctDNA detection rates varied between sample types, with mutations detected in 94.3% (116/123) of oral rinse samples and 80.5% (99/123) of plasma samples (p = 0.002). Interestingly, while this difference was significant overall, the detection rates became comparable in advanced clinical stages (stages III or IV) (92.7% [51/55] versus 89.1% [49/55], p = 0.742). Notably, the baseline detection rate of plasma ctDNA was significantly associated with tumor differentiation (p = 0.028), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.007), and clinical stage (p = 0.003), while oral rinse-derived ctDNA detection remained consistent across clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Regarding mutation profiles, we identified 471 somatic mutations involving 109 genes in oral rinse samples (median 2 mutations/sample, range: 0–12) and 430 mutations involving 114 genes in plasma samples (median 1 mutation/sample, range: 0–12). The most frequently mutated genes in oral rinse samples were TP53, TERT, MYC, and EP300 (38.7% [45/116], 30.2% [35/116], 23.3% [27/116], and 23.3% [27/116], respectively), while in plasma samples they were TP53, TERT, MYC, and APC (42.4% [42/99], 30.3% [30/99], 26.3% [26/99], and 21.2% [21/99], respectively). The complete mutation spectra of oral rinse and plasma cfDNA samples are shown in Fig. 2A, B, respectively (mutated genes present in at least two patients).

Heatmap illustrating the mutational profile of 116 oral rinse-derived cfDNA samples (A) and 99 plasma cfDNA samples (B). Each column represents a tumour sample, and each row represents a gene. Only genes mutated in more than two cases are shown. The upper bar indicates the number of mutations per patient, and the right bars show gene mutation frequencies across the cohort. Samples are clustered by pathological subtype. cfDNA cell-free DNA.

Comparative analysis of mutation profiles between tissue and liquid biopsy samples

Analysis of somatic mutations in the 99 patients with paired samples revealed distinct but overlapping mutation patterns. We identified 352 mutations shared between tissue and oral rinse, and 366 between tissue and plasma (Fig. 3A, B). Additionally, 97 mutations were unique to oral rinse-derived ctDNA and 62 to plasma ctDNA, with a total of 544 mutations present in either tissue and oral rinse or tissue and plasma (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that oral rinse and plasma samples can serve as complementary sources for mutation detection may capture different aspects of tumor heterogeneity and can even be enriched in clones with metastatic potential.

A–C Venn diagrams showing the number of mutations in oral rinse-derived cfDNA and tumour gDNA (A), plasma cfDNA and tumour gDNA (B), and those shared between tissue and oral rinse-derived or plasma cfDNA (C). D Bar graph showing the allele frequency of variants in tumour gDNA. Blue bars indicate mutations detected in both tumour gDNA and cfDNA (oral rinse-derived or plasma), while red bars show mutations detected only in tumour gDNA. E Correlation between tumour DNA content in oral rinse and plasma samples. cfDNA cell-free DNA, gDNA genomic DNA.

To further evaluate the genetic correlation and differences between oral rinse and plasma samples, we analyzed the impact of each mutation’s VAF on detection concordance. Using tumor gDNA genotyping as the gold standard, the overall sensitivity was 31.4% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 28.7%–34.3%) for oral rinse-derived cfDNA and 32.7% (95% CI: 30%–35.5%) for plasma cfDNA. Notably, combining both sample types significantly improved the detection sensitivity to 48.6% (95% CI: 45.6%–51.5%). Mutations identified in tumor gDNA but not in plasma or oral rinse-derived cfDNA typically had lower VAFs (mean VAF = 8.4%, Fig. 3D). When patients with low VAF mutations (VAF < 5%) were excluded from tumor biopsy, detection sensitivity increased to 36.5% (95% CI: 33.4%–39.7%) for oral rinse-derived cfDNA and 37.1% (95% CI: 34%–40.4%) for plasma cfDNA, with the combined sensitivity reaching 55.9% (95% CI: 52.6%–59.1%).

Overall, OSCC exhibits genetic heterogeneity, with slight differences in mutation occurrence between oral rinse and plasma. Compared to individual oral rinse or plasma testing, the sensitivity of detecting these biomarkers significantly increases when both oral rinse and plasma are tested simultaneously. Interestingly, we observed no significant correlation between tumor DNA content in oral rinse and plasma samples (correlation coefficient = 0.0468, p = 0.6458; Fig. 3E).

Identification of the features significantly associated with 1-year recurrence

We investigated the relationship between 1-year recurrence and both genetic and clinical characteristics. The cohort was randomly divided at a 2:1 ratio into training (n = 82) and validation (n = 41) sets to develop and validate the prediction model. Through differential mutation analysis between patients with and without 1-year recurrence, we identified seven SNV mutation genes (TP53, TERT, APC, FAT1, VEGFA, IKZF1, and EP300) and three CNV mutation genes (MYC, EGFR, and PIK3CA) with mutation frequencies greater than 10% (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Data 2). Stepwise logistic regression analysis further refined these to seven genes significantly associated with recurrence (TP53, TERT, IKZF1, EP300, MYC, EGFR, and PIK3CA) (Fig. 4B, C; Supplementary Data 3).

A The most frequently mutated genes. B Significantly different SNVs included in the 1-year recurrence model. C Significantly different CNVs included in the 1-year recurrence model. D Differences in clinical characteristics based on 1-year recurrence status. p-values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test. The size of the white dots in (C) represents sample size. SNV single-nucleotide variant, CNV copy number variation.

Considering the potential importance of clinical factors in prognosis, we further compared one-year recurrence among patients grouped by various clinical factors, including gender, age, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, differentiation status, treatment modality, T stage, lymph node metastasis status, and clinical stage as detected by immunohistochemistry. The results showed that patients with advanced clinical stages (69.8% versus 35.9%, p = 0.004), lymph node metastasis (63.6% versus 33.0%, p = 0.018), and advanced T stage (T3, T4) (63.5% versus 36.7%, p = 0.023) had higher one-year recurrence rates. To avoid collinearity among clinical variables, we selected T stage and lymph node metastasis as independent clinical factors for model construction (Fig. 4D).

Machine learning integrates gene mutation status and clinical factors to build a tumour prediction model to predict patient outcomes

In summary, we identified 7 mutated genes and 2 clinical factors associated with 1-year recurrence in patients. The Random Forest model demonstrated not only the highest predictive performance but also the most stable results across both training and validation sets. While XGBoost and GBM showed excellent performance in the training set (AUC: 0.861, 95% CI: 0.781–0.942 and AUC: 0.866, 95% CI: 0.786–0.946, respectively), their performance slightly decreased in the validation set (AUC: 0.827, 95% CI: 0.698–0.957 and AUC: 0.837, 95% CI: 0.714–0.960, respectively). The Elastic Net achieved moderate results in its best feature combination (training set: AUC: 0.807, 95% CI: 0.707–0.906; validation set: AUC: 0.794, 95% CI: 0.659–0.929), but its overall performance was inferior to the other models (Supplementary Table 1). Based on its superior c-index and stability, we selected the Random Forest as our final prediction model. Further analysis revealed that the combined model integrating seven mutated genes and 2 clinical factors demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity in both the training cohort (AUC: 0.869, 95% CI: 0.798–0.950) and the validation cohort (AUC: 0.854, 95% CI: 0.740–0.967) (Fig. 5A). Using nomogram analysis based on multivariate logistic regression, we identified EGFR, PIK3CA, MYC, TP53, and TERT as the strongest predictors among all incorporated features, with EGFR mutation demonstrating the highest predictive weight (Fig. 5B).

A ROC curve for the 1-year recurrence predictive model in the training and validation cohorts. B A nomogram based on stepwise logistic regression to predict 1-year recurrence. C Predicting PFS and OS by combining key mutation and clinical characteristics. D, E Kaplan–Meier curves comparing high- and low-risk groups for PFS (D) and OS (E). PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival.

Since patients without 1-year recurrence showed better survival outcomes, we further evaluated the model’s long-term prognostic value. In the follow-up analysis of 113 patients (10 lost to follow-up; median follow-up time 846 days, range 117–1623 days), the model demonstrated good performance in predicting both progression-free survival (PFS, C-index = 0.753, 95% CI: 0.700–0.806, AIC = 576.6, BIC = 597.2) and overall survival (OS, C-index = 0.700, 95% CI: 0.630–0.771, AIC = 471.6, BIC = 490.7) (Fig. 5C). Risk stratification based on the model’s predictions effectively identified patient subgroups with significantly different outcomes: the low-risk group showed markedly better PFS (HR, 4.977; 95% CI, 2.976–8.322; p < 0.001) and OS (HR, 3.644; 95% CI, 2.031–6.538; p < 0.001) than did compared to the high-risk group (Fig. 5D, F). To validate these findings in an external cohort, we constructed a simplified model incorporating T stage, N stage, and three key CNV mutations using the TCGA-HNSCC dataset. This validation model also successfully stratified patients into groups with significantly different survival outcomes (HR = 1.326; 95% CI: 1.009–1.743; p = 0.043), confirming the prognostic utility of combining these clinical and molecular parameters across different patient populations (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Clinical Relevance of Pre-treatment ctDNA Analysis

To evaluate the clinical utility of liquid biopsy, we assessed both ctDNA status and concentration in paired oral rinse and plasma samples from 99 patients. Using our personalized seven-gene panel, samples with at least two detectable somatic variations were classified as ctDNA-positive16. Analysis revealed positive ctDNA in 44.4% (44/99) of oral rinse samples and 36.4% (36/99) of plasma samples (Figs. 6A and 7A).

In univariate analysis, significant associations were observed between positive ctDNA status and both T stage (oral rinse: p = 0.003; plasma: p = 0.029) and lymph node metastasis (oral rinse: p = 0.035; plasma: p = 0.029). However, multiple linear regression modeling for both oral rinse ctDNA (R² = 0.113) and plasma ctDNA (R² = 0.082) status did not demonstrate strong associations between ctDNA status and these clinical features, although T stage remained significant in oral rinse ctDNA (p = 0.012). T stage and lymph node metastasis showed marginal significance in plasma ctDNA multivariate models (p = 0.093) (Supplementary Tables 2,3).

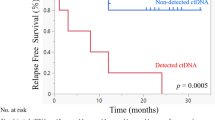

Notably, ctDNA status demonstrated substantial prognostic value. Both sample types significantly associated Positive ctDNA status with inferior survival outcomes. In oral rinse samples, ctDNA positivity predicted shorter PFS (HR, 2.978; 95% CI, 1.791–4.951; p < 0.001) and OS (HR, 1.980; 95% CI, 1.15–3.406; p = 0.014). Similarly, plasma ctDNA positivity was associated with decreased PFS (HR, 3.311; 95% CI, 1.999–5.485; p < 0.001) and OS (HR, 2.111; 95% CI, 1.241–3.591; p = 0.006) (Figs. 6B, C; and 7B, C).

In contrast, quantitative analysis of ctDNA concentration showed limited prognostic value. Pre-treatment ctDNA concentrations averaged 4.23 ng/mL (range 0.89–15.6 ng/mL) in oral rinse and 5.15 ng/mL (range 0.59–16.12 ng/mL) in plasma. Similarly, while univariate analysis revealed associations between ctDNA concentration and clinical features (lymph node metastasis with oral rinse-derived ctDNA, p = 0.012; tumor site and T stage with plasma ctDNA, p = 0.010 and p = 0.032, respectively), multiple linear regression modeling for both oral rinse (R² = 0.109) and plasma (R² = 0.212) ctDNA did not demonstrate strong associations between baseline ctDNA values and these clinical features, although lymph node metastasis remained significant in oral rinse (p = 0.006) and tumor site remained marginally significant in plasma (p = 0.029) multivariate models (Supplementary Tables 4, 5).

When patients were stratified using optimized concentration thresholds (3.59 ng/mL for oral rinse; 3.84 ng/mL for plasma), no significant survival differences were observed between high and low concentration groups in either PFS (oral rinse: HR, 1.343; 95% CI, 0.820–2.199, p = 0.242; plasma: HR, 1.039; 95% CI, 0.636–1.697; p = 0.88) or OS (oral rinse: HR, 1.259; 95% CI, 0.740–2.143, p = 0.396; plasma: HR, 0.868; 95% CI, 0.511–1.476; p = 0.602) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Evaluation of pre-treatment ctDNA status and concentration in early recurrence prediction models

For ctDNA status integration, all models demonstrated robust predictive performance, with AUCs ranging from 0.825 to 0.857. Notably, plasma ctDNA status integration achieved the highest performance (AUC: 0.857; 95% CI: 0.782–0.933), while the tumor prediction model alone and the oral rinse-derived ctDNA integration model showed comparable results (AUC: 0.843; 95% CI: 0.764–0.923 and AUC: 0.825; 95% CI: 0.741–0.909, respectively) (Fig. 8A). However, when incorporating ctDNA concentration data, both plasma and oral rinse-derived ctDNA models (AUC = 0.818; 95% CI: 0.731–0.904 and AUC = 0.824; 95% CI: 0.739–0.908, respectively) showed slightly inferior performance compared to the original tumor prediction model (AUC = 0.830; 95% CI: 0.747–0.913) (Fig. 8B).

A 1-year recurrence prediction based on the combined model incorporating DNA mutations, clinical factors, and ctDNA status from oral rinse and plasma samples. B 1-year recurrence prediction using the combined model with ctDNA concentration from oral rinse and plasma samples. C, D Kaplan–Meier curves comparing high- and low-risk groups for PFS (C) and OS (D). ctDNA circulating tumour DNA, PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival.

In survival outcome analysis, we evaluated the impact of integrating ctDNA status and concentration on model performance. For PFS prediction, the model incorporating plasma ctDNA status (C-index = 0.756; 95% CI: 0.698–0.815; AIC = 477.0; BIC = 498.6) outperformed the baseline model (C-index = 0.730; 95% CI: 0.670–0.790; AIC = 481.3; BIC = 500.7) with improved C-index and lower AIC values. The oral rinse-derived ctDNA status model (C-index = 0.735; 95% CI: 0.677–0.794; AIC = 482.8; BIC = 504.4) showed only slight improvement in C-index but with increased AIC and BIC values (Supplementary Table 6).

In comparison, models incorporating ctDNA concentration for PFS prediction showed similar but generally inferior performance to ctDNA status models. The plasma ctDNA concentration model (C-index = 0.736; 95% CI: 0.676–0.795; AIC = 483.1; BIC = 504.7) and oral rinse-derived ctDNA concentration model (C-index = 0.733; 95% CI: 0.673–0.794; AIC = 480.6; BIC = 502.2) both demonstrated modest improvements in C-index, but their AIC and BIC values suggested potential overfitting (Supplementary Table 6).

For OS prediction, all integrated models showed minimal changes compared to the baseline model (C-index = 0.676; 95% CI: 0.594–0.759; AIC = 409.1; BIC = 427.4). The plasma ctDNA status model (C-index = 0.678; 95% CI: 0.596–0.760; AIC = 410.0; BIC = 430.2) and plasma ctDNA concentration model (C-index = 0.683; 95% CI: 0.601–0.765; AIC = 411.0; BIC = 431.3) slightly improved C-index but increased both AIC and BIC values. The oral rinse-derived ctDNA status model (C-index = 0.670; 95% CI: 0.588–0.752; AIC = 410.8; BIC = 431.1) and oral rinse-derived ctDNA concentration model (C-index = 0.661; 95% CI: 0.573–0.748; AIC = 408.9; BIC = 429.2) showed C-index values slightly lower than or comparable to the baseline model (Supplementary Table 6).

Based on these findings, we further stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. The low-risk group had significantly longer PFS (HR = 3.014; 95% CI: 1.796–5.060; p < 0.001) and OS (HR = 2.977; 95% CI: 1.662–5.333; p < 0.001) than did the high-risk group (Fig. 8C, D).

Mutational profile association with clinicopathological features and impact of treatment on mutation spectrum

In the analysis of the 7-gene panel (TP53, TERT, IKZF1, EP300, MYC, EGFR and PIK3CA) mutation spectrum and clinicopathological features in 123 OSCC patients, we identified two key gene mutations significantly associated with specific clinical characteristics, with an additional gene mutation showing borderline significance. TP53 mutations were significantly increased in advanced T stage (75.0% vs 53.0%, p = 0.030), patients with lymph node metastasis (76.3% vs 52.9%, p = 0.017), and those with advanced clinical stage (78.2% vs 45.6%, p < 0.001). Similarly, EGFR mutations were closely associated with advanced T stage (42.5% vs 20.5%, p = 0.017) and advanced clinical stage (40.0% vs 17.6%, p = 0.008). Furthermore, EP300 mutations exhibited a higher frequency in advanced T stage (47.5% vs 28.9%, p = 0.068), approaching statistical significance.

To investigate the impact of treatment on the 7-gene panel mutation spectrum, we conducted longitudinal monitoring of 30 OSCC patients. Among these patients, 19 ultimately experienced disease recurrence, whilst 11 remained recurrence-free. Following surgical treatment, ctDNA levels in all patients decreased below the detection limit. In subsequent monitoring, ctDNA became detectable again post-treatment in recurrent patients. Comparing the mutation spectrum before and after treatment, we observed high conservation of mutations across the 7-gene panel after treatment. Specifically, in oral rinse analysis, only 3 patients (ID 36, 44 and 117) lacked baseline mutations after treatment; in plasma ctDNA analysis, only 2 patients showed alterations: patient 24 lacked the EGFR amplification present at baseline, whilst patient 118 had no detectable mutations after treatment. All remaining recurrent patients maintained identical 7-gene panel mutation profiles compared to pre-treatment.

To gain deeper insight into the specific effects of treatment on mutation profiles, we conducted a detailed analysis of tissue sample data from a representative recurrent patient. Before treatment, the patient’s primary mutations included a TP53 termination mutation (p.R342*), TERT promoter mutation (c.-124C > T), NOTCH1 splicing variant and FAT1 truncation mutations, with VAF ranging from 5.04–8.37%. At clinical recurrence, these mutations were not only preserved but exhibited significantly increased VAFs, with TP53 reaching 30.03% and TERT reaching 29.71%. More notably, several new key driver events emerged at clinical recurrence, including FGFR1, ZNF703 and NSD3 amplifications, CDKN2A/B deletion, and an additional ATG2A mutation. Chromosome-level changes also underwent significant transformation: multiple chromosomal region deletions present before treatment essentially disappeared at clinical recurrence, whilst new amplifications in the 17q region and deletions in the 9p21.3 region emerged. These findings provide further evidence that treatment may induce tumour clonal composition remodeling and the emergence of new driver events (Supplementary Table 7).

Surveillance

Although not the primary objective of this study, it is interesting to determine whether tumour DNA can be detected in the oral rinse or plasma of patients after tumour resection. To explore the role of ctDNA in disease monitoring, we conducted a longitudinal analysis of ctDNA in 30 patients as a preliminary exploration. Among the 19 patients who experienced recurrence, ctDNA was detected in oral rinse samples from 17 patients an average of 132 days (range: 38-259 days) before clinical recurrence, and in plasma samples from 15 patients an average of 120 days (range: 36-259 days) before clinical manifestation (Fig. 9A, C).

A–D Changes in ctDNA status and concentration from T0 to T2 in the oral rinse recurrence cohort (A), oral rinse non-recurrence cohort (B), plasma recurrence cohort (C), and plasma non-recurrence cohort (D). E, F Monitoring of serial oral rinse-derived (E) and plasma (F) samples from 19 patients, showing ctDNA detection (red circle) and subsequent relapse (yellow triangle). ctDNA was detected at all pre-operative time points (purple square). The dashed line indicates the total follow-up duration. ctDNA circulating tumour DNA.T0, pre-treatment. T1, post-operation. T2 post-operation detectable ctDNA.

The pattern of ctDNA detection varied among patients: three patients showed detectable tumor DNA exclusively in oral rinse, one patient only in plasma, and nine patients demonstrated simultaneous detection in both sample types. Detailed temporal analysis revealed interesting variations in detection timing. For instance, in four patients (patients 6, 15, 48, and 93), oral rinse-derived ctDNA was detected at 84,38, 82, and 539 days post-baseline, with plasma ctDNA detection following 110, 38, 64, and 47 days later, respectively. Conversely, in patient 36, plasma ctDNA was detected first at 76 days post-baseline, followed by oral rinse-derived ctDNA 33 days later (Fig. 9E, F).

Importantly, among patients without disease progression (n = 11), ctDNA remained consistently undetectable during dynamic sampling (Fig. 9B, D), supporting its potential specificity as a monitoring tool.

Discussion

In this study, we used a 551-gene targeted sequencing approach to analyze tumor tissue, plasma, and oral rinse samples from 123 HPV-negative OSCC patients. Through this comprehensive approach, our analysis reveals the molecular characteristics of OSCC and provides a framework for clinical application of liquid biopsy.

HPV-negative OSCC is most common in Asia1, characterized primarily by TP53 mutations and cell cycle regulation abnormalities17, these molecular features resulting in poorer prognosis, thus requiring specific biomarkers for risk stratification. A thorough understanding of the mutation landscape is essential for developing personalized treatment and monitoring methods that can help improve the high recurrence rates and survival outcomes in these patients.

Our study revealed significantly higher ctDNA detection rates in oral rinse (94.3%) compared to plasma (80.5%), consistent with previous findings by Wang et al and Mes et al.14,18. This differential detection efficiency likely stems from fundamental biological mechanisms governing tumor DNA release. Due to direct anatomical proximity, localized shedding of tumor DNA into the oral cavity occurs through processes including direct cellular exfoliation, local microvasculature leakage, and inflammatory cell-mediated clearance. These mechanisms are particularly relevant in early-stage disease, where at this stage tumors have not yet acquired the vascular invasion capabilities that are necessary for efficient systemic DNA release19,20. Notably, we observed that detection rates equalized in advanced disease stages (92.7% vs 89.1%), suggesting that as tumors progress, they develop enhanced capability to shed DNA into both local and systemic circulation. This detection rate convergence can primarily be attributed to the biological evolution of advanced OSCC. Specifically, advanced OSCC typically exhibits enhanced invasiveness, increased angiogenesis, and elevated metastatic potential. Consequently, these characteristics collectively facilitate the release of tumor DNA into systemic circulation21,22.

Our comparative mutation analysis between sample types further established the complementary nature of these liquid biopsy approaches. The distinct yet overlapping mutation profiles between oral rinse and plasma samples likely represent different aspects of tumor spatial heterogeneity and clonal evolution23. Importantly, unique mutations in liquid biopsies not detected in primary tumor tissue may originate from minor subclones or metastatic deposits, reflecting the ability of liquid biopsies to capture tumor heterogeneity more comprehensively than single-site tissue sampling24. This biological heterogeneity provides the rationale for our finding that combined testing significantly improved detection sensitivity to 48.6%, which represents a substantial advance over previous single-sample approaches.11,25, Collectively, these findings emphasize the value of integrated multi-compartment liquid biopsy strategies for comprehensive mutation profiling in OSCC.

We identified seven key mutated genes (TP53, TERT, IKZF1, EP300, MYC, EGFR, and PIK3CA) and two clinical factors (T stage and lymph node metastasis) associated with recurrence risk, validating the model in the TCGA dataset. Among these, EGFR, PIK3CA, MYC, TP53, and TERT emerged as the most significant predictors, highlighting their critical role in OSCC progression. These findings align with existing literature and further elucidate the importance of these genes in the molecular pathological mechanisms of OSCC.

TP53 mutations are the most common genetic alterations in HPV-negative HNSCC, with frequencies ranging from 73% to 100% in published literature26 and 60.1% (74/123) in our cohort, profoundly influencing tumor biology and treatment response. The clinical significance of these mutations stems from their unique molecular pathological mechanisms: mutant p53 not only loses the tumor-suppressive functions of wild-type p53 but also acquires new abilities to actively promote cancer progression. Stein et al. emphasized in their review that this “gain-of-function” makes mutant p53 an important therapeutic target, especially considering that approximately 50% of human cancers carry p53 mutations. At the molecular level, mutant p53 interacts with various transcription factors and effector molecules, creating a molecular environment favorable for tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis27. This concept has been validated in clinical research. In a 7-year prospective multicenter study involving 560 HNSCC patients, Poeta et al. classified TP53 mutations as disruptive or non-disruptive based on the predicted degree of disturbance to protein structure. The results indicated that the presence of any TP53 mutation, compared to wild-type TP53, was associated with decreased overall survival17. Further deepening this finding, Caponio et al. developed a computational algorithm through systematic bioinformatic analysis to precisely classify TP53 mutations into high-risk or low-risk subtypes, confirming that this classification method could effectively predict survival outcomes in HNSCC patients27. Notably, in their follow-up study, they further validated the clinical relevance of this classification system, finding that patients carrying high-risk TP53 mutations showed significantly reduced treatment response, with 3.3 times higher odds of stable disease or progression compared to wild-type patients28. This body of evidence aligns closely with our research results, explaining why TP53 mutations demonstrate such high predictive weight in our prediction model.

In our study, the frequency of TERT promoter mutations (50.4%, 62/123) was significantly higher than that reported in the TCGA-HNSCC database (0.6%, 3/508). Indeed, this disparity may be closely associated with HPV expression. Concurrently, multiple studies have demonstrated that TERT promoter mutations are prevalent in HPV-negative OSCC patients and strongly correlate with adverse prognosis29,30. More importantly, TERT promoter mutations enhance telomerase expression by creating new ETS transcription factor binding sites, thereby conferring cells with unlimited replicative potential31. Moreover, TERT exerts non-telomeric functions through signaling pathways such as WNT/β-catenin, NF-κB, and MYC, further promoting tumor invasion, metastasis, and immune evasion32. Notably, in various cancers, including bladder neuroendocrine carcinoma, metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma, research consistently reveals high mutation rates in TP53 and TERT33,34,35. Furthermore, studies suggest a potential synergistic effect between these gene mutations in tumor progression. Specifically, TP53 mutations may compromise cell cycle regulation and DNA repair mechanisms, while TERT promoter mutations enhance telomerase activity, enabling tumor cells to acquire immortality36,37,38.

Both in our study and in the external validation using TCGA data, EGFR, PIK3CA, and MYC exhibited notably high mutation frequencies. Furthermore, at the molecular signaling pathway level, EGFR, PIK3CA, and MYC collectively form an interconnected signaling network that regulates cellular proliferation and survival39,40,41. EGFR, functioning as an upstream regulator, modulates multiple downstream signaling cascades through its tyrosine kinase activity42,43. When constitutively activated by factors such as gene amplification, EGFR dimerize at the cell membrane, subsequently activating two critical downstream pathways: the MAPK (Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk) pathway and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway encoded by PIK3CA44,45. These pathways promote cellular proliferation by upregulating key genes such as CCND1/cyclin D1, while simultaneously activating MYC transcription through phosphorylation and promotion of Mad1 degradation. As a downstream effector, MYC controls numerous genes involved in cellular growth and metabolism46.

Functional interactions exist among these three genes: EGFR activation enhances MYC expression, while PIK3CA mutations increase MYC protein stability by inhibiting its degradation47,48. PIK3CA mutations generate constitutively active kinase variants, leading to aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway49, which converges with and amplifies EGFR signaling39. This interactive mechanism elucidates why the co-occurrence of these genetic alterations has significant implications for tumor progression.

In oral diseases, research demonstrates that these molecular alterations are closely associated with disease progression and treatment response. Atrophic/erosive oral lichen planus exhibits significantly higher EGFR expression compared to control groups, suggesting a greater potential for malignant transformation50. PIK3CA mutations play a crucial role in the progression of oral potentially malignant disorders to invasive carcinomas, with evidence indicating that these mutations can emerge during early transformation51,52.

Regarding treatment response, EGFR mutations and chromosome 11q13 amplifications (encompassing CCND1, FGF3, FGF4, and FGF19) are significantly associated with decreased PFS in HNSCC patients receiving PD-1 inhibitor immunotherapy, serving as potential biomarkers for identifying patients unsuitable for immunotherapy53. However, although EGFR-targeted therapies show efficacy in a subset of HNSCC patients, PIK3CA mutations frequently cause primary or acquired resistance. This explains why strategies targeting these pathways in combination demonstrate superior efficacy in preclinical models54,55, providing a theoretical foundation for future molecularly-guided personalized treatment approaches.

Based on the comprehensive understanding of these functionally relevant driver gene alterations, researchers have integrated these molecular markers into predictive models, creating analytical tools capable of capturing the biological complexity of OSCC. This integrative approach significantly improves the accuracy of recurrence risk stratification (training cohort AUC: 0.869, validation cohort AUC: 0.854), establishing a foundation for precision medicine in OSCC based on molecular characteristics.

The integration of pre-treatment plasma ctDNA status significantly enhanced our model’s predictive capability, consistent with emerging evidence that ctDNA can capture aspects of tumor biology that may not be readily apparent in single-site tissue sampling56. Notably, while ctDNA positive status was significantly associated with adverse clinical outcomes, ctDNA concentration measurements demonstrated limited predictive value, reflecting their distinct biological implications—the former indicates the presence of driver mutations, while the latter primarily reflects overall tumor burden57,58. Our findings demonstrate concordance with the studies by Cui et al. and Dal Secco et al., providing supporting evidence for the potential utility of ctDNA in monitoring the recurrence of OSCC. Our longitudinal monitoring suggested that ctDNA detection may precede clinical recurrence by approximately four months (132 days in saliva samples and 120 days in plasma samples), which aligns with observations by Cui et al., who reported that ctDNA detection potentially anticipated recurrence by 4.4 months (average 2.4 vs. 6.8 months)59. Similarly, Dal Secco et al. indicated that ctDNA detection might identify clinical recurrence several months in advance60. Additionally, our research noted that combining plasma and saliva analysis may enhance detection sensitivity, while Cui et al. also observed that integrating saliva and plasma samples could potentially improve overall tumor monitoring performance. Collectively, these findings suggest that ctDNA monitoring might serve as a complementary approach to routine clinical surveillance, providing auxiliary information for follow-up management of oral cancer patients.

More importantly, we uncovered patterns of treatment-induced molecular evolution suggesting a two-phase model of recurrence: initial persistence of founding driver mutations followed by acquisition of additional alterations that enhance fitness and treatment resistance. The significant increase in VAF of key driver genes such as TP53 and TERT at recurrence (reaching 30.03% and 29.71%, respectively) indicates expansion of resistant clones, while newly acquired FGFR1, ZNF703, and NSD3 amplifications and CDKN2A/B deletion provide complementary oncogenic advantages. These molecular dynamics highlight the importance of adaptive treatment strategies based on sequential liquid biopsies that can identify resistance mechanisms before clinical recurrence.

Several limitations in our study warrant consideration. Although our cohort of 123 patients provided meaningful insights, a larger sample size would strengthen the generalizability of our findings. The 551-gene panel, while comprehensive, was not specifically designed for OSCC, potentially missing some disease-specific mutations. Technical factors, including sample quality and extraction methods, might have influenced ctDNA detection sensitivity, particularly in oral rinse samples. Additionally, our predictive models, though promising, require validation in independent cohorts. Future studies should focus on developing OSCC-specific gene panels, optimizing detection methods, and conducting multicenter validations with longer follow-up periods.

Methods

Patient enrollment

This prospective cohort study was conducted at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China, between January 2019 and March 2024. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Scientific Research Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (approval number: SB20190200). All research involving human participants was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrollment in the study.

Patients were enrolled based on the following criteria: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) histologically confirmed HPV-negative primary OSCC; (3) no prior radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery; (4) agreement to follow-up protocols; and (5) no history of synchronous or metachronous cancers.

All patients had pathological examinations to confirm the diagnosis. HPV status was determined by p16 immunohistochemistry, with negative p16 expression confirming HPV-negative status.

Tumor staging was performed according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification system61. Following National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, patients with positive cervical lymph nodes, perineural invasion, or close surgical margins received postoperative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy62.

For external validation, we analyzed data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-HNSCC dataset (single-nucleotide variants (SNV) data: n = 508; copy number variations (CNV) data with survival information: n = 485).

Sample collection and DNA extraction

We collected paired tissue, oral rinse, and plasma samples from all patients at baseline before any treatment initiation. Longitudinal monitoring was performed in a subset of 30 patients, with samples collected at pre-defined time points: one-month post-surgery (before adjuvant therapy), and then every three months during follow-up until disease progression was confirmed by RECIST 1.1 criteria63.

Fresh tissue samples were split for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) confirmation and genomic DNA extraction.

Oral rinse and plasma samples were collected in the morning after overnight fasting. For oral rinse collection, patients first rinsed their mouth with mouthwash or purified water to remove debris. Under unstimulated conditions, patients were instructed to rinse with 10 mL of 0.9% saline solution for 30 seconds, then expectorate into cfDNA collection tubes. This process was repeated twice, yielding a total volume of approximately 20 mL of oral rinse64. Plasma samples were collected using Apostle tubes. All samples were transported at 2–8 °C and subsequently stored at -80 °C until analysis.

For DNA extraction, oral rinse samples were first centrifuged (1600 × g, 15 minutes, 4 °C) to separate the supernatant and pellet fractions. The supernatant was processed for cfDNA extraction using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), while the pellet was used for genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Plasma cfDNA was isolated using MagMAX DNA Multi-Sample Ultra Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA quantification was performed on the Qubit fluorometer with dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and fragment analysis was conducted using Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Library construction

Probe hybridization capture was employed for library construction. Initially, 15 ng to 200 ng of gDNA was fragmented into 200–350 bp fragments using a Covaris S2 instrument. For library construction, 20–60 ng of cfDNA was used. The fragmented DNA and cfDNA underwent end repair, A-tailing, and adaptor ligation using the KAPA HyperPlus DNA Library Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States) and the VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China), respectively. Unligated adaptors were removed via size selection with Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, California, United States). The ligated products were PCR amplified to construct the precapture library. The final library was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a Qubit fluorometer, and its quality was assessed with the Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies). Commercial reagents and custom probes were used for library construction and hybridization capture.

Library sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

DNA libraries were sequenced on NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with 150 bp paired-end reads. Raw sequencing data were processed through a standardized bioinformatics pipeline. Briefly, reads were quality-filtered using Fastp (v2.20.0) for adapter trimming and low-quality bases65. BWA-MEM algorithm (v0.7.17) performed alignment to the human reference genome hg19 GRCh37. PCR duplicates were removed using Dedup66.

Variant calling was performed using VarDict (v1.5.7), with variant filtering based on the 1000 Genomes Project (August 2015) and ExAC (v0.3) browser67,68. Variants were annotated using InterVar. CNVs were identified using CNVkit (v1.1), and fusions were detected using Factera (v1.4.4)69.

VAF was defined as the percentage of mutant reads among the total reads. ctDNA concentration was calculated in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL), determined as the product of the total cfDNA concentration and the maximum VAF of somatic mutations70.

Model development and validation

For predictive model construction, the cohort was randomly divided into training (n = 82) and validation (n = 41) sets. Feature selection involved three steps: (1) differential mutation analysis identified genes with >10% mutation frequency, (2) stepwise logistic regression selected significant mutations, and (3) univariate analysis identified significant clinical factors.

Four different machine learning approaches: Random Forest, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting Machine and Elastic Net were performed. For each model type, we constructed seven feature combinations:(1) clinical features only, (2) SNV features only, (3) CNV features only, (4) combined SNV and CNV features, (5) combined SNV and clinical features, (6) combined CNV and clinical features, and (7) integrated SNV, CNV, and clinical features.

For external validation, we constructed a simplified prognostic model in the TCGA-HNSCC cohort, incorporating T stage, N stage, and key CNV mutations identified in our study. This model was evaluated for its ability to stratify patients by overall survival using Cox proportional hazards regression.

For model performance assessment, we employed different evaluation metrics based on the nature of the outcome. For binary outcomes (such as 1-year recurrence), model performance was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with area under the curve (AUC) as the primary metric. For time-dependent survival outcomes (progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)), we employed Harrell’s concordance index (C-index), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) as evaluation metrics. Internal validation was performed through tenfold cross-validation, and external validation was conducted in the validation cohort.

Statistical analysis and model construction

Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Fisher’s exact test (with Chi-square test when expected frequencies ≥5). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for two-group comparisons and one-way ANOVA for multiple groups. Correlations were evaluated using Pearson correlation coefficient. Associations between clinical features and ctDNA status were analyzed through univariate analysis, followed by multivariate logistic regression with Nagelkerke’s R² for significant variables (p < 0.05). For analyzing associations between ctDNA concentrations and clinical parameters, univariate and multiple linear regression analyses were used.

For ctDNA concentration, Univariate and multiple regression analyses were used to analyze potential associations between ctDNA concentrations and clinical parameters [Box–Cox transformation was applied to normalize distributions when the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test failed; adjusted Exp(β) was reported]. Survival outcomes were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using log-rank tests. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models.

All the statistical analyses and plotting were performed using R software version 4.4 (https://www.r-project.org/). A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance for all analyses.

Data availability

The data generated in this study comprised clinically annotated medical records by treating investigators. While these data are not publicly available to protect patient privacy, they are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The custom code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Katirachi, S. K., Grønlund, M. P., Jakobsen, K. K., Grønhøj, C. & von Buchwald, C. The prevalence of HPV in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Viruses 15, 451 (2023).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Gormley, M., Creaney, G., Schache, A., Ingarfield, K. & Conway, D. I. Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: definitions, trends and risk factors. Br. Dent. J. 233, 780–786 (2022).

Gatta, G. et al. Prognoses and improvement for head and neck cancers diagnosed in Europe in early 2000s: The EUROCARE-5 population-based study. Eur. J. Cancer 51, 2130–2143 (2015).

de Bree, R. et al. Detection of locoregional recurrent head and neck cancer after (chemo)radiotherapy using modern imaging. Oral. Oncol. 45, 386–393 (2009).

Müller, J. et al. The value of (18) F-FDG-PET/CT imaging in oral cavity cancer patients following surgical reconstruction. Laryngoscope 125, 1861–1868 (2015).

García-Pardo, M., Makarem, M., Li, J. J. N., Kelly, D. & Leighl, N. B. Integrating circulating-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis into clinical practice: opportunities and challenges. Br. J. Cancer 127, 592–602 (2022).

Sanz-Garcia, E., Zhao, E., Bratman, S. V. & Siu, L. L. Monitoring and adapting cancer treatment using circulating tumor DNA kinetics: Current research, opportunities, and challenges. Sci. Adv. 8, eabi8618 (2022).

Galot, R. et al. Liquid biopsy for mutational profiling of locoregional recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 104, 104631 (2020).

Egyud, M. et al. Plasma circulating tumor DNA as a potential tool for disease monitoring in head and neck cancer. Head. Neck. 41, 1351–1358 (2019).

Hilke, F. J. et al. Dynamics of cell-free tumour DNA correlate with treatment response of head and neck cancer patients receiving radiochemotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 151, 182–189 (2020).

Mydlarz, W. K., Hennessey, P. T., Wang, H., Carvalho, A. L. & Califano, J. A. Serum biomarkers for detection of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head. Neck. 38, 9–14 (2016).

Tivey, A., Church, M., Rothwell, D., Dive, C. & Cook, N. Circulating tumour DNA - looking beyond the blood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 600–612 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Detection of somatic mutations and HPV in the saliva and plasma of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 293ra104 (2015).

Ahn, S. M. et al. Saliva and plasma quantitative polymerase chain reaction-based detection and surveillance of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 140, 846–854 (2014).

Bratman, S. V. et al. Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis as a predictive biomarker in solid tumor patients treated with pembrolizumab. Nat. Cancer 1, 873–881 (2020).

Poeta, M. L. et al. TP53 mutations and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2552–2561 (2007).

Mes, S. W. et al. Comprehensive multiparameter genetic analysis improves circulating tumor DNA detection in head and neck cancer patients. Oral. Oncol. 109, 104852 (2020).

Chaudhuri, A. A. et al. Early detection of molecular residual disease in localized lung cancer by circulating tumor DNA profiling. Cancer Discov. 7, 1394–1403 (2017).

Bettegowda, C. et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ra224 (2014).

Wan, J. C. M. et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 223–238 (2017).

Abbosh, C. et al. Corrigendum: Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature 554, 264 (2018).

Mattox, A. K. et al. Applications of liquid biopsies for cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. eaay1984 (2019).

Abbosh, C. et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature 545, 446–451 (2017).

van Ginkel, J. H., Huibers, M. M. H., van Es, R. J. J., de Bree, R. & Willems, S. M. Droplet digital PCR for detection and quantification of circulating tumor DNA in plasma of head and neck cancer patients. BMC Cancer 17, 428 (2017).

Tokheim, C. J., Papadopoulos, N., Kinzler, K. W., Vogelstein, B. & Karchin, R. Evaluating the evaluation of cancer driver genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14330–14335 (2016).

Stein, Y., Rotter, V. & Aloni-Grinstein, R. Gain-of-function mutant p53: all the roads lead to tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 6197 (2019).

Caponio, V. C. A. et al. High-risk TP53 mutations predict poor primary treatment response of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Dis. 30, 2018–2026 (2024).

Saito, Y. et al. TERT promoter mutation positive oral cavity carcinomas, a clinically and genetically distinct subgroup of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Head. Neck. 45, 3107–3118 (2023).

Vinothkumar, V. et al. TERT promoter hot spot mutations are frequent in Indian cervical and oral squamous cell carcinomas. Tumour Biol. 37, 7907–7913 (2016).

Horn, S. et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science 339, 959–961 (2013).

Hafezi, F. & Perez Bercoff, D. The solo play of TERT promoter mutations. Cells 9, 749 (2020).

Ohmoto, A. et al. Genomic features of bladder neuroendocrine carcinoma with composite histology. Histol. Histopathol. 18887 (2025).

Moussa, M. J. et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic variant histology (non-clear cell) renal cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 13, e010958 (2025).

Rizzo, M. et al. The genomic landscape of metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma and its prognostic value: a comprehensive analysis of a large real-world clinico-genomic database. ESMO Open. 10, 104294 (2025).

Sullivan, K. D., Galbraith, M. D., Andrysik, Z. & Espinosa, J. M. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by p53. Cell Death Differ. 25, 133–143 (2018).

Hernández Borrero, L. J. & El-Deiry, W. S. Tumor suppressor p53: Biology, signaling pathways, and therapeutic targeting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1876, 188556 (2021).

Roake, C. M. & Artandi, S. E. Regulation of human telomerase in homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 384–397 (2020).

Hynes, N. E. & Lane, H. A. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 341–354 (2005).

Fruman, D. A. et al. The PI3K Pathway in Human Disease. Cell 170, 605–635 (2017).

Dang, C. V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149, 22–35 (2012).

Wee P. & Wang Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers 9, 52 (2017).

Yarden, Y. & Sliwkowski, M. X. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 127–137 (2001).

Normanno, N. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene 366, 2–16 (2006).

Ramos-García, P. et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of cyclin D1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral. Oncol. 83, 96–106 (2018).

Zhu, J., Blenis, J. & Yuan, J. Activation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways regulates Myc-mediated transcription by phosphorylating and promoting the degradation of Mad1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA105, 6584–6589 (2008).

Sears, R. et al. Multiple Ras-dependent phosphorylation pathways regulate Myc protein stability. Genes Dev. 14, 2501–2514 (2000).

Bouchard, C., Marquardt, J., Brás, A., Medema, R. H. & Eilers, M. Myc-induced proliferation and transformation require Akt-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO proteins. EMBO J. 23, 2830–2840 (2004).

Engelman, J. A. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 550–562 (2009).

Keshani, F., Kargahi, N., Nikbakht, M. H., Najafi, S. & Fallah, F. Expression of epithelial growth factor receptor as a protein marker in oral reticular and erosive lichen planus. BMC Oral. Health 24, 726 (2024).

Lui, V. W. et al. Frequent mutation of the PI3K pathway in head and neck cancer defines predictive biomarkers. Cancer Discov. 3, 761–769 (2013).

Wood, H. M. et al. The clonal relationships between pre-cancer and cancer revealed by ultra-deep sequencing. J. Pathol. 237, 296–306 (2015).

Dou, S. et al. EGFR mutation and 11q13 amplification are potential predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 813732 (2022).

Licitra, L. et al. Evaluation of EGFR gene copy number as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: EXTREME study. Ann. Oncol. 22, 1078–1087 (2011).

Vermorken, J. B. et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 1116–1127 (2008).

Liu, Z. et al. Construction of a risk stratification model integrating ctDNA to predict response and survival in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer. BMC Med. 21, 493 (2023).

Cescon, D. W., Bratman, S. V., Chan, S. M. & Siu, L. L. Circulating tumor DNA and liquid biopsy in oncology. Nat. Cancer 1, 276–290 (2020).

Chen, B. et al. Predictive role of ctDNA in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma receiving definitive chemoradiotherapy combined with toripalimab. Nat. Commun. 15, 1919 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. Longitudinal detection of somatic mutations in saliva and plasma for the surveillance of oral squamous cell carcinomas. PLoS ONE16, e0256979 (2021).

Dal Secco, C. et al. Longitudinal detection of somatic mutations in the saliva of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma–affected patients: a pilot study. Front. Oncol. 14, 1480302 (2024).

American Joint Committee on C. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York: Springer (2017).

National Comprehensive Cancer N. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and Neck Cancers: National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2023).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Chuang, A. Y. et al. Presence of HPV DNA in convalescent salivary rinses is an adverse prognostic marker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 44, 915–919 (2008).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Hwang, K. B. et al. Comparative analysis of whole-genome sequencing pipelines to minimize false negative findings. Sci. Rep. 9, 3219 (2019).

Li, Q. & Wang, K. InterVar: Clinical Interpretation of Genetic Variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP Guidelines. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 267–280 (2017).

Lai, Z. et al. VarDict: a novel and versatile variant caller for next-generation sequencing in cancer research. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e108 (2016).

Newman, A. M. et al. FACTERA: a practical method for the discovery of genomic rearrangements at breakpoint resolution. Bioinformatics 30, 3390–3393 (2014).

He, M. M. et al. Variant Interpretation for Cancer (VIC): a computational tool for assessing clinical impacts of somatic variants. Genome Med. 11, 53 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was not supported by any specific funding outside of in-kind assay support from Simcere, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C. assisted in conceptualizing the study, and Z.C., L.H., P.X. and J.Q. undertook the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. S.Z. and Z.C. collected the assay samples and clinical information. A.L. and Y.L. aided in editing the manuscript. B.Q. designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Chen, L., Li, S. et al. Integrated analysis of oral rinse-derived and plasma circulating tumour DNA for mutation profiling and outcome prediction with oral squamous cell carcinoma. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 183 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00976-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00976-9

This article is cited by

-

Saliva-based molecular diagnostics in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC): a non-invasive frontier in oncology

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2025)