Abstract

Glaucoma is a globally prevalent disease that leads irreversible blindness. The visual field (VF) examination is important but time-consuming for visual function evaluation with high requirement of cooperation and reliability of patients. While color fundus photographs (CFPs) are easy to access. Here, we proposed a multi-modal longitudinal estimation deep learning (MLEDL) system, capable of predicting present and future VFs from CFPs and clinical text. This model was developed on 1598 records in cross-sectional and 3278 records in longitudinal dataset, with 446 external testing records. The pointwise mean absolute error across five models ranged from 3.098 to 4.131 dB. Heatmaps demonstrated the spatial relationship between fundus damage and vision loss. VF grading methods were employed for verifying the clinical reliability. Consequently, our MLEDL facilitates VF prediction by CFPs and clinical narratives, offering potential as function assessment tool over the long-duration course of glaucoma and thereby improving clinical practice efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of the irreversible blindness1,2,3,4, characterized by the progressive damage of retinal ganglion cells (RGC), with the corresponding loss in visual field (VF)5. In clinical practice, glaucoma detection usually involves a comprehensive approach, comprised of clinical information collection, intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement, structural evaluations and VF tests6. The color fundus photograph (CFP) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) intuitively present the optic nerve head (ONH) impairment, and standard automated perimetry (SAP) reveals the light sensitivity at different positions in the field of vision7,8. However, SAP requires a high level of patient cooperation and reliability with a relatively lengthy test time, and yields subjective results affected by the test-retest variability9,10,11,12,13,14. Conversely, CFPs offer a quicker method for evaluating RGC loss.

Glaucomatous changes including visual defects, thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), increasing cup-disc ratio (CDR) of ONH, all stem from the pathological losses of RGCs15,16. The structural-functional relationship in glaucoma has long been explored based on statistics models17,18,19,20,21. In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has been widely used22,23,24. Machine learning (ML) has been a strong tool to describe the spatial mapping of different locations in SAP to the ONH25,26,27. This kind of relationship allows VF predicting from fundus structure. Moreover, deep learning (DL), capable of directly analyzing medical images, has been applied on estimating VF from OCT with promising results28,29,30,31,32.

In primary healthcare settings or large-scale eye disease screening scenarios, OCT and SAP are often unavailable, whereas CFPs and the clinical information such as age, sex, simple medical history can be easily acquired, potentially even via smartphone in online medical consultation33. Previous studies have demonstrated a lot about multi-modal DL that integrates diverse data types for more precise diagnosis and prediction34,35,36,37. We also discovered that combined IOP, VF and CFP could markedly improve the performance for diagnosis glaucoma38. It is speculated that predicted VFs from CFPs and medical text through multi-modal DL network could assist ophthalmologists to more accurately estimate the function loss of the glaucoma patients, especially in resource-limited settings.

Due to the difficulty of treatment, glaucoma patients tend to have a prolonged course of disease with regular follow-up visits. However, these visits are fraught with uncertainty, such as patients sometimes missing appointments or even being lost to follow-up. It would be helpful for ophthalmologists to make treatment decisions if subsequent changes could be known at the baseline visit. Several researchers have developed AI models to predict future VF changes through current VF and other biometric parameters39,40,41,42. The easy accessibility of CFPs makes predicting VFs through it of high clinical value for glaucoma management.

In this study, we proposed a multi-modal and longitudinal estimation deep learning (MLEDL) system, utilizing multiple data covering CFPs and clinical text labels in the whole glaucoma follow-up process to realize pointwise SAP sensitivity estimation, either cross-sectional or longitudinal. The structure-function relationship was verified from the arranged heatmaps. Additionally, the authentic and predicted VF images were graded by ophthalmologists to assess the clinical reliability. The MLEDL system could serve as a convenient preliminary evaluation tool for patient without credible VF examinations to determine visual function in the present and future.

Results

Study design

The entire study workflow is shown in Fig. 1. Firstly, we collected VFs, CFPs, IOP, central corneal thickness (CCT), and clinical narratives from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (ZJU) and the Third Hospital of Peking University (PKU) (Fig. 1a). Secondly, CFPs were cropped into region of interest (ROI) images and segmented for optic disc (OD) and optic cup (OC). Part of VFs were converted into Voronoi images (Fig. 1b). Thirdly, clinical text information and CFPs were input into different prediction networks to estimate cross-sectional and longitudinal VFs, validated on external dataset from PKU (Fig. 1c). The estimation models included basic VF estimation deep learning model (EDL) for the original CFPs, ROI images and ROI with OD/OC segmentation images, the multi-modal estimation deep learning model (MEDL) and the longitudinal estimation deep learning model (LEDL). The MEDL applied sex, age, IOP, CCT, medical history characteristics and ROI images as input, shown in Supplementary Fig. 1; while the LEDL used ROI images and time interval as input to predict future VF, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Finally, heatmaps were generated to explore the structure-function relationship and original and predicted VFs were graded by ophthalmologists to verify clinical availability (Fig. 1d, e).

a Different types of data collected from Zhejiang University. b The preprocessing of color fundus photographs (CFPs) and visual field (VF). c The development of 5 prediction models that allows different input format. d heatmaps generated for structure-function relationship exploration.e VFs were graded by 3 ophthalmologists for clinical validation.

Demographic and clinical data

An overview of demographic characteristics of this study is described in Table 1. There were three kinds of datasets in this study: cross-sectional dataset, longitudinal dataset and external dataset. The cross-sectional dataset consisted of 1598 records, 1300 for training and 298 for testing. The median mean deviation (MD) is −5.30 dB and square root of loss variance (sLV) is 3.35 dB, reflecting the majority of glaucoma patients in this dataset with VF loss. The longitudinal dataset included 3278 records, 2622 for training and 656 for testing. The median MD is −5.22 dB and sLV is 3.43 dB, similar to the cross-sectional dataset. The external dataset contains 446 records, all used for testing, with median MD of −6.95 dB and sLV of 4.34 dB.

In the cross-sectional dataset, clinical text information was collected, shown in Table 2, including 13 symptoms, 4 past history, 1 family history, 4 categories and 2 measurements. For symptoms, past history and family history, the label was marked as “1” if present in the chief complaint or medical history, and “0” if absent or being denied. The main symptoms for diminution of vision and blurred vision were most recorded. Besides, 4 categories were numbered “0” to “3” for input and measurements were entered as numerical values. Most patients in this study were open angle glaucoma (OAG).

The global index estimation

Mean sensitivity (MS) was regarded as a global index that represented the overall level of VF loss. We tested whether MS of VF could be predicted by five AI models. The predictive error is listed in Table 3. The root mean square error (RMSE) of MS was 3.561, 3.328, 3.481, 2.847 and 2.470 dB for CFP, ROI, OD/OC segmentation, clinical information and longitudinal model, respectively. On account of the model using ROI images showing minimal prediction error among image-only models (EDL), we applied ROI images as the image input section for MEDL and LEDL.

Correlation analysis and Bland-Altman plots for MS assessment are shown in Fig. 2. A linear correlation between predicted and measured MS showed strong associations with a coefficient of determination, R-squared (R2), of 0.773, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) of 0.884 and mean absolute error (MAE) of 2.465 dB for ROI model (Fig. 2b), showing the best performance among image-only inputs. The MEDL performed better, with R2 of 0.834, PCC of 0.916 and MAE of 2.099 dB (Fig. 2d). For the longitudinal dataset, the LEDL achieved R2 of 0.839, PCC of 0.920 and MAE of 1.666 dB (Fig. 2e).

a–e Correlation analysis of actual MS and predicted MS from the original color fundus photographs (CFPs), region of interest (ROI) of CFPs, ROI of CFPs with optic disc (OD) and optic cup (OC) segmentation, ROI and clinical information, ROI and follow-up interval years. f–j Bland-Altman plots for the agreement between actual MS and predicted MS from the original CFPs, ROI of CFPs, ROI of CFPs with OD and OC segmentation, ROI and clinical information, ROI and follow-up interval years.

We applied Bland-Altman plots to evaluate the agreement level between predicted MS and measured MS. The models all performed strong prediction ability, with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.840, 0.862, 0.858, 0.903, 0.918 for CFP model, ROI model, OD/OC segmentation model, the MEDL and the LEDL, respectively (Fig. 2f–j). Besides, five Bland-Altman plots showed a negative linear fit slope, demonstrating that these models tend to underestimate the MS values at high values.

Pointwise VF values estimation

Light sensitivity values at each point displayed the specific distribution of VF defects. The average predict error is shown in Table 3 (marked as Pointwise). The RMSE of pointwise VFs was 5.724, 5.353, 5.496, 4.984 and 4.391 for CFP, ROI, OD/OC segmentation, clinical information and longitudinal model, respectively. Furthermore, we calculated the predictive error between the average value of predicted pointwise VFs and the original mean, listed in Table 3 as well (marked as Pointwise-mean).

Pointwise MAE values are drawn at their original position on VF reports in Fig. 3, with right eye format. For the EDL, the MAE of CFP model, ROI model and OD/OC segmentation model was within the scope of 3.1–5.0 dB (Fig. 3a), 3.0–4.8 dB (Fig. 3b), and 3.0–5.0 dB (Fig. 3c), respectively. The MAE of the MEDL was within the range of 2.7–4.4 dB (Fig. 3d), and the LEDL showed an MAE ranging from 2.4 to 3.7 dB (Fig. 3e). The MAE was most elevated at the nasal field, especially superior nasal field, and was lowest at inferior paracentral area in the above models. Besides, we calculated the difference between ROI model and clinical information model (Fig. 3f). It could be found that the prediction error of each VF point was reduced after the addition of clinical information, with the greatest reduction at the superior nasal region and minimal change in the inferior temporal area.

a–e The pointwise mean absolute error (MAE) of the original color fundus photographs (CFPs), region of interest (ROI) of CFPs, ROI of CFPs with optic disc and optic cup segmentation, ROI and clinical information, ROI and follow-up interval years. f The difference between MAE of ROI with clinical information and MAE of ROI.

Comparison with other network structure models

To explore whether ResNet-50 we used is the best predictive model, we applied a basic model comparison experiment. Two common other CNN models, DenseNet-121 and MobilNet-V3-large, and a Linear Regression model were constructed to compare with the EDL. The comparison result was depicted in Supplementary Table 1, the RMSE of MS was 3.563, 3.866and 5.724 dB for DenseNet-121, MobilNet-V3-large, and Linear Regression model, and the RMSE of point-wise VF values was 5.749, 5.887, 8.053 dB for these models, all performing worse than ResNet-50.

Prediction performance on the external dataset

The EDL was applied on the external dataset of PKU, with the prediction errors shown in Table 3. The RMSE of MS was 3.958, 3.714 and 4.018 dB for CFP, ROI, OD/OC segmentation model, and the RMSE of pointwise VFs was 6.421, 5.575 and 6.007 dB, respectively. For this external dataset, correlation analysis and Bland-Altman plots for MS assessment are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The PCC of these three models was 0.714, 0.739, 0.751 (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c), and the ICC was 0.714, 0.735, 0.751 (Supplementary Fig. 3d–f), respectively.

Pointwise MAE values for external dataset are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4. The MAE ranged from 3.2 to 6.4 dB for the CFP model (Supplementary Fig. 4a), 3.2–5.4 dB for the ROI model (Supplementary Fig. 4b), and 3.5–5.8 dB for the OD/OC segmentation model (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

Heatmaps and structure-function relationship

Glaucoma-related VF defects are caused by optic nerve damage, which mainly manifest on the ONH in CFPs. To explain the “black box” effect of DL systems and validate the structure-function mapping in glaucoma, the heatmaps of ROI models were generated and analyzed, as shown in Fig. 4. Previous studies have already revealed the relationship between Octopus VF and ONH damage, with both VF and ONH divided into 10 regions for one-to-one correspondence (Fig. 4a)19. The heatmaps covering ROI images of the EDL were arranged in the original VF points (Fig. 4b). To visualize the features, all heatmaps were organized according to their location in divided regions in VF (Fig. 4c). It could be found that the prediction of superior and inferior area of VFs (region 2,3,4,7,8,9) by the ROI model complied with existing rules, although predictions for nasal and temporal regions (region 1,5,6,10) were less accurate.

Clinical grading validation

To verify the clinical practicability of the MLEDL, we employed two methods to grade the original and predicted VF, with classification results shown in Table 4. We graded predicted VFs from EDL and MEDL using cross-section dataset. For the Hoddap-Parrish-Anderson (HPA) method, the accuracy was 0.82 and 0.83 for the EDL and the MEDL, respectively. For the Voronoi method, the accuracy was 0.66 and 0.70 for the EDL and the MEDL, respectively, probably because the Voronoi method is more sophisticated. The accuracy of the EDL was only 0.53 for the category Moderate in the HPA method, and was only 0.55-0.61 for the category Mild and Moderate in the Voronoi method. It indicates that there is a great difference between the prediction ability for different severity of VF defect and the model performed worst when estimating moderate VF defect.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a glaucoma VF prediction model, named MLEDL, utilizing CFPs and clinical information generated during follow-up visits of glaucoma patients. The MLEDL comprised three subsystems: the EDL for original and processed fundus images, the MEDL for ROI images with clinical information, and the LEDL for ROI images with follow-up interval years. All five models achieved good performance, with pointwise MAE 4.131, 3.903, 3.980, 3.575 and 3.098 dB, and were validated on an external dataset from PKU. Heatmaps were employed to elaborate the structure-function relationship. Besides, the grading validation was conducted by ophthalmologists to demonstrate the potential of MLEDL in clinical practice. The system aids in evaluating visual function in glaucoma patients throughout the whole disease course.

VF examination is crucial for assessing the visual damage progression of glaucoma patients. However, due to the unreliability, instability and inconvenience of SAP, reliable VFs acquisition can be challenging. Previous studies have used OCT images or measurements to cross-sectionally estimate VF values and applied past VFs to predict future VFs with satisfactory results28,29,30,31,32,43,44. We compared current studies of VF prediction with our models in Supplementary Table 2. Compared to existing researches, our study applied CFPs instead of OCT or past VFs as input, easier for acquisition and with a wider range of clinical application. Besides, we applied smaller number of input data and additionally included clinical information and time interval to train MLEDL with relatively comparable predictive performance (pointwise MAE of 3.575 dB for MEDL and 3.098 dB for LEDL). The MLEDL simulates real clinical application and might be more favorable for preliminary assessment of patients with suspected glaucoma in primary health care facilities.

For the EDL, we input the original CFPs, ROI of CFPs and ROI with OD/OC segmentations of CFPs, with pointwise MAE of 4.131, 3.903 and 3.980 dB. The comparison experiment has validated the excellence of its network structure. Compared with the original CFPs, the prediction ability was significantly improved with ROI images, because of emphasizing the main characteristic damage on the ONH. However, prediction effect decreased with OD/OC segmentation labeled compared with only ROI images. It was speculated that the network had already recognized the features of OD and OC, and some important features were blocked by the contour lines. And the potential biases of drawing boundaries might also be a cause for the performance degradation. It demonstrated that the EDL, just combined with existing ROI cropped algorithm, can predict VF automatically, achieving optimal predictions without expert labeling.

We tested the EDL on the external validation dataset from PKU, with pointwise MAE of 4.860, 4.417 and 4.684 dB for the original CFPs, ROI of CFPs and ROI with OD/OC segmentations of CFPs input, respectively. It seems that the best result was also obtained with ROI images input. Compared to the internal dataset, the estimation performance decreased, especially for the pointwise R2 of the original CFPs. It might due to differentiated data distribution of the external dataset from different clinical scenarios. Another reason for performance reduction may be the difference of data collection equipment, image quality, and demographic characteristics. Larger external dataset and image enhancement methods may be applied to resolve the heterogeneity problem of input data in the further research.

Medical text information is important for clinical decision-making in addition to imaging examinations. It records symptoms, past medical history and other relevant history that ophthalmologists could assess the preliminary condition of one patient. With advancements in semantic extraction and natural language processing, clinical text has gradually gained attention45,46,47. In this study, although the free text was not directly input, we summarized medical history into 19 labels with the measurements (IOP and CCT) and basic information (sex and age) to input. It more comprehensively described the condition of patients, and effectively enhanced the predictive performance, with pointwise MAE of 3.575 dB, better than using only fundus images. Therefore, medical text information, easily obtained in a simple outpatient conversation, would improve the efficiency of vision evaluation of glaucoma patients.

Longitudinal prediction is a critical research focus in glaucoma. Numerous studies paid attention on progression prediction utilizing VFs and other parameters at baseline39,40,41,42, some listed in Supplementary Table 2. Li et al. effectively predicted VF progression by CFPs with satisfactory results48. In our study, we further input CFPs and interval years to estimate pointwise VF values intuitively with MAE of 3.098 dB. The presented future VF changes can guide patient management and promote treatment compliance.

Glaucoma affects both VF and fundus structure, so it is crucial to explore the function-structure relationship in glaucoma. Based on the connection proposed by previous study18,49,50,51, we arranged heatmaps covering ROI images on each VF point, and divided them into ten clusters and compared them with corresponding fundus partition. This relationship can serve as strong evidence when predicting VF from CFPs, and further proves the one-to-one mapping rule between fundus structure and visual function.

Previous study has founded the published VF prediction models tended to underestimate worsening of VF loss52. Clinical grading validation was conducted to assess clinical relevance. Predicted and original VFs were graded according to two methods, the HPA method and the Voronoi method. It could be seen that they were highly consistent on the basis of the HPA methods, with accuracy of 0.82 and 0.83 for the EDL and the MEDL, which indicates that the MLEDL could basically meet the needs of preliminary visual function assessment without misestimate the severity of glaucoma. However, the classification accuracy for moderate cases of HPA method was only 0.53 and 0.56 for the EDL and the MEDL, respectively. We speculated that this is mainly because that extreme cases are relatively easy to spot. Moderate VFs need more precise identification for screening and prognostication in the future research, with better algorithm and a more rigorous clinical validation method. Nevertheless, for completely precise severity grading, referral to the hospital with SAP examination would be a better choice.

There were several limitations in our study. Firstly, the datasets are relatively small. Although the accuracy of results is comparable to those of OCT studies with large amounts of data, it is still prone to the problem of data bias. Secondly, MEDL and LEDL were not validated on external dataset for clinical and longitudinal information lacking. Larger datasets containing ethnically diverse populations and text information should be applied in further study. Thirdly, the classification accuracy of moderate cases in clinical validation was unsatisfactory. A more precise prediction algorithm with large amount of multi-center data would be required. Finally, the specific IOP controlled medications information was lacked as a predictive factor for the long-term follow up, and it will be incorporated for more consummate prognostic predictions in the future research.

In general, we designed a glaucoma VF estimation DL-assisted system, named MLEDL, capable of predicting current and future VF by CFPs and text information, with clinical validation. Heatmaps were used to verify function-structure relationship. This system is valuable for vision function assessment throughout the long-duration course of glaucoma.

Methods

The ethical approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of ZJU (No. Y2023–1073) and the Peking University Third Hospital (No. 2022-065-02), and individual informed consent for retrospective study was waived. The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Health Portability and Accessibility Act.

Patients and datasets

We retrospectively collected 1598 records in cross-sectional dataset and 3278 records from longitudinal dataset from 633 patients. All patients underwent the examination at the Eye Center at the Second Affiliated Hospital School of Medicine of ZJU, a comprehensive hospital, mostly at glaucoma outpatient clinics. The included patients were diagnosed with glaucoma or determined to be normal by the qualified glaucoma specialists, based on abnormities in the IOP, VFs, CFP, OCT, and medical history. We excluded patients combined other eye diseases that would have a considerable impact on the quality of VF and CFPs. The exclusion criteria are: (1) patients with other optic nerve diseases; (2) patients with macular diseases or other severe retinal diseases (e.g. vitreous hemorrhage and retinal detachment); (3) patients with severe dioptric media turbidity. Both established and new patients with glaucoma were included, with their first recorded visit serving as the baseline.

VFs were measured by two experienced technicians using G1 program test pattern with stimulus size III by the OCTOPUS 900 perimeter (HAAG-STREIT, Switzerland). We only included reliable VFs with false-negative rate ≤30% and false-positive rate ≤30%9,53.

CFPs were obtained by CR-2 PLUS AF Digital Non-Mydriatic Retinal Camera (CANON, Japan). CFPs with poor quality (vessels within 1-disc diameter of the OD margin cannot be identified, 50% of the area is obscured and only part of OD is visible in the image) were excluded.

IOP and CCT were both acquired by non-contact tonometer NT-530P (NIDEK, Japan). We collected age, sex, medical history from Electronic Health Record system, that recorded by ophthalmologists from outpatient or inpatient visits.

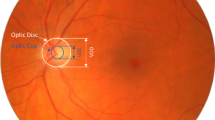

Image preprocessing

The ONH area was cropped as a square ROI to concentrate on the major glaucoma structure impairment, without featured RNFL defect. Generally, the ONH centered in the clipped image; meanwhile, we preserved the large extent of parapapillary atrophy. We chose a square selection box and limited the ratio of the selection box to the overall image size. Since standard CFPs were acquired with a 45° field of view, it ensured that the ratio of the range of ROI images relative to the whole fundus is consistent for CFPs with different sizes measured by different machines.

To singularize the feature of CDR increasing and OD rim narrowing, two ophthalmologists drew contours of OD and OC using a labeling tool on ROI of CFPs. Three types of images were used as input, including CFPs, ROI of CFPs, and ROI with OD/OC segmentation. Finally, the sizes of 3 types of images were adjusted to 224 × 224 × 3 when input to the network.

Clinical information preprocessing

Clinical information was collected from the previous visit records of patients, including sex, age, IOP, CCT, and the features of medical history. Sex was coded as “0” for male and “1” for female, Age was input as an integer, and IOP and CCT were input as consecutive numbers. For the medical history, since it is often impossible to extract a complete formatted medical history in most outpatient situations, we extracted the following labels from free-text narratives in the following categories: (1) Symptoms: Diminution of vision, Blurred vision, Dry eye, Foreign body sensation, Eye swelling, Eye fatigue, Ophthalmodynia, Swelling pain at the root of nose, Lacrimation, Constriction of visual field, Red eye, Black shadows fluttered and Photophobia; (2) Past history: Cataract surgery, Glaucoma surgery, Complicated with other retinal eye diseases and Eye traumas; (3) Family history: Is there family history; (4) Diagnosis category: Normal, OAG, Angle closure glaucoma (ACG) and Glaucoma of other types. The presence of symptoms, past history and family history was labeled as “1” if confirmed, and “0” if absent or not mentioned. Besides, different diagnosis categories were coded as “0” to “3” for model input. “0” stands for Normal, “1” for OAG, “2” for ACG, and “3” for Glaucoma of other types.

Network development and comparison

The MLEDL contains three types of five networks to process different types of input. The model structure is depicted in Fig. 5. The detailed inputs, components and outputs of each network were summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

a–c basic VF estimation deep learning models (EDL) using color fundus photographs (CFPs), region of interest (ROI) of CFPs, ROI with optic disc and optic cup segmentation. d multi-modal VF estimation deep learning model (MEDL) using ROI and clinical information. e longitudinal VF estimation deep learning model (LEDL) using ROI and interval years for future VF prediction.

1) EDL: Basic EDL used only images as input to predict light sensitivity values and global indices of VF. The network structures for prediction based on original CFPs, ROI images and ROI with OD/OC segmentation images are shown in Fig. 5a-c, respectively. Specifically, ResNet-50 served as the backbone to extract image features54. A regression head, constructed as a single hidden layer neural network, is attached to the end of the backbone. The input image features extracted by ResNet-50 became a 2048-dimensional vector after global average pooling, which would be fed into the above-mentioned regression head to output a 59-dimensional vector that represents the prediction of VF. We also applied two other common CNN models, MobilNet-V3-large55 and DenseNet-12156, and one Linear Regression model for comparison with ResNet-50. They all used ROI images as input to predict MS and point-wise light sensitivity.

2) MEDL: On the basis of the EDL, the MEDL fuses the ROI images with clinical text information simultaneously to predict VF. The structure of this fusion model is displayed in Fig. 5d. The image processing part still used ResNet-50 as the feature extractor, similar to EDL. The clinical information, after preprocessing, consisting of a series of discrete and continuous attributes, was represented by a 31-dimensional vector. After projected by the fully-connected network (FCN), clinical and image information were fused through the Transformer decoder architecture57. The clinical features acted as target tokens, while the image features served as memory tokens. Inside the decoder, clinical information was first processed by a multi-head self-attention block. After that, the clinical features and the image features were fused through the multi-head cross-attention mechanism. The output of the Transformer decoder, containing both image and clinical information, was then fed into a regression head to complete the VF prediction task. We raised an example in Supplementary Fig. 1 to help understand this multi-modal network.

3) LEDL: For longitudinal prediction, as shown in Fig. 5e, the LEDL received both ROI images and follow-up year as inputs. The image was still processed by the ResNet-50, outputting a 128-dimensional vector as image features. The follow-up year, a positive number, was simply projected into a 128-dimensional vector through an FCN. Extracted image features and temporal features were directly concatenated to form a 256-dimensional vector, encompassing both image and follow-up year information. Finally, the concatenated vector served as input for the regression head to predict the VF values. Similarly, an application example in the Supplementary Fig. 2 could assist comprehension for this longitudinal model.

External evaluation

An external dataset retrospectively collected from the Eye Center of the Third Hospital of PKU, another comprehensive hospital, was employed to validate the generalization ability. This dataset contained 446 pairs of Octopus VFs and CFPs of 157 eyes of 92 patients from April 25, 2013 to March 28, 2023, without clinical information included. The VFs in this dataset were also measured using G1 program test pattern with stimulus size III by the OCTOPUS 900 perimeter (HAAG-STREIT, Switzerland). The CFPs were captured by CR-2 AF Digital Non-Mydriatic Retinal Camera (CANON, Japan). The preprocess procedures for these data mirrored those of the internal dataset, which were already mentioned above.

The structure-function relationship validation

In this study, heatmaps were generated for the EDL using ROI images to discover the contributing region on the ONH for estimating VF. These heatmaps presented a rainbow color scale, with red for the most contributing and blue for the least. We adjusted the transparency of heatmaps to 50% and covered them on ROI images. The heatmaps overlaying ROI images were arranged according to the original positions of test points on the VF reports. Following the function-structure relationship proposed by the previous study18, the ROI images arranged on VF points were divided into ten clusters. We observed whether the most contributing regions on heatmaps in each cluster were consistent with the corresponding ONH partitions.

Clinical grading assessment

In order to validate the clinical effects for the predicted VFs, the original VFs, the predicted VFs from EDL with ROI images, and the predicted VFs from MEDL were graded using two methods, the HPA method and the Voronoi method. The HPA method, acceptable to most glaucoma specialists, classified glaucoma severity based on MD values: mild (MD < 6 dB), moderate (-12 dB <MD ≤ –6 dB), and severe (MD ≤ –12 dB)58. Since the HPA method directly classifies the VF severity based on MD values, no further grading applied by glaucoma specialists is required.

For the Voronoi method, VFs were converted into the Voronoi images and graded as our previous article59. VF values were arranged into a certain order as a vector \({\boldsymbol{x}}=[{x}_{1},\,{x}_{2},\cdots {x}_{k}]\), with \(k\) being the number of test points in the Octopus. The vector \({\boldsymbol{x}}\), mapped to the eight-bit grayscale of \([0,255]\), was converted into the vector \({\boldsymbol{y}}\). Then we built a new \(224\times 224\) blank image, in which the tangential circle represented the central 30° of VF. At last, the values in vector \({\boldsymbol{y}}\) were assigned to their original VF test position, while the grayscale of other points was equal to the closest points60. These Voronoi VFs were random permutation and classified into five grades from mild to severe by one senior ophthalmologist and two junior ophthalmologists, accordance with the standard described in our previous study. The Voronoi grading standard is detailed in Supplementary Table 4.

Statistics analysis

The performance was evaluated by R2, MAE, RMSE, and the relevant calculating equations were showed in Eqs. (1)–(5)). For global indices prediction, we also applied PCC and ICC. Clinical assessment employed overall accuracy (ACC), with a two-tailed paired-sample t-test on the ACC to identify significant differences between original and predicted VF values. Normality test were conducted to assess the distribution of variables. Variables with a normal distribution were characterized by mean (standard deviation), while those without were characterized by median (interquartile range). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v26.0, IBM), Python (v3.6.8, Python Software Foundation) and R (v4.1.2, RStudio). A confidence level was designated at 95%, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Equations (1)–(5): mean square error (MSE), RMSE, MAE, Variance (Var), R2:

\({y}_{i}\) represents for the true value and \(\hat{{y}_{i}}\) represents for the predicted value.

Data availability

The data used in this article cannot be totally shared publicly due the violation of patient privacy and being lack of informed consent for data sharing. A portion of data is available from the GRAPE dataset in Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6406319.v1) that described in our previous article61. Other data could be acquired from the Eye Center, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (contact J.Y., yejuan@zju.edu.cn, and K.J., jinkai@zju.edu.cn) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Code availability

The codes could also be acquired from the Eye Center, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (contact J.Y., yejuan@zju.edu.cn, and K.J., jinkai@zju.edu.cn), for researchers who meet the criteria and accept our user license.

References

Bourne, R. R. et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 1, e339–e349 (2013).

Jonas, J. B. et al. Glaucoma. Lancet 390, 2183–2193 (2017).

Stevens, G. A. et al. Global prevalence of vision impairment and blindness: magnitude and temporal trends, 1990-2010. Ophthalmology 120, 2377–2384 (2013).

Tham, Y. C. et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 121, 2081–2090 (2014).

Weinreb, R. N., Aung, T. & Medeiros, F. A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 311, 1901–1911 (2014).

Weinreb, R. N. & Khaw, P. T. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet 363, 1711–1720 (2004).

Agis Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 1. Study design and methods and baseline characteristics of study patients. Controlled Clin. trials 15, 299–325 (1994).

Jampel, H. D., Friedman, D. S., Quigley, H. & Miller, R. Correlation of the binocular visual field with patient assessment of vision. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 1059–1067 (2002).

Lee, M., Zulauf, M. & Caprioli, J. The influence of patient reliability on visual field outcome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 117, 756–761 (1994).

Newkirk, M. R., Gardiner, S. K., Demirel, S. & Johnson, C. A. Assessment of false positives with the Humphrey Field Analyzer II perimeter with the SITA Algorithm. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 4632–4637 (2006).

Gardiner, S. K., Swanson, W. H., Goren, D., Mansberger, S. L. & Demirel, S. Assessment of the reliability of standard automated perimetry in regions of glaucomatous damage. Ophthalmology 121, 1359–1369 (2014).

Agis Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 130, 429–440 (2000).

Bengtsson, B. & Heijl, A. False-negative responses in glaucoma perimetry: indicators of patient performance or test reliability?. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2201–2204 (2000).

Artes, P. H., Iwase, A., Ohno, Y., Kitazawa, Y. & Chauhan, B. C. Properties of perimetric threshold estimates from full threshold, SITA standard, and SITA fast strategies. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 2654–2659 (2002).

Harwerth, R. S., Wheat, J. L., Fredette, M. J. & Anderson, D. R. Linking structure and function in glaucoma. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 29, 249–271 (2010).

Kwon, Y. H., Fingert, J. H., Kuehn, M. H. & Alward, W. L. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 1113–1124 (2009).

Raza, A. S. & Hood, D. C. Evaluation of the structure-function relationship in glaucoma using a novel method for estimating the number of retinal ganglion cells in the human retina. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56, 5548–5556 (2015).

Naghizadeh, F., Garas, A., Vargha, P. & Holló, G. Structure-function relationship between the octopus perimeter cluster mean sensitivity and sector retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured with the rtvue optical coherence tomography and scanning laser polarimetry. J. Glaucoma 23, 11–18 (2014).

Holló, G. Comparison of structure-function relationship between corresponding retinal nerve fibre layer thickness and Octopus visual field cluster defect values determined by normal and tendency-oriented strategies. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 150–154 (2017).

Wollstein, G. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer and visual function loss in glaucoma: the tipping point. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 96, 47–52 (2012).

Gardiner, S. K., Johnson, C. A. & Cioffi, G. A. Evaluation of the structure-function relationship in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 3712–3717 (2005).

Yew, S. M. E. et al. Ocular image-based deep learning for predicting refractive error: A systematic review. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res 4, 164–172 (2024).

Kong, X., Jiang, X., Song, Z. & Ge, Z. Data ID extraction networks for unsupervised class- and classifier-free detection of adversarial examples. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2025.3572245 (2025).

Kong, X., He, Y., Song, Z., Liu, T. & Ge, Z. Deep probabilistic principal component analysis for process monitoring. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 36, 7422–7436. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3386890 (2025)

Zhu, H. et al. Predicting visual function from the measurements of retinal nerve fiber layer structure. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 5657–5666 (2010).

Guo, Z. et al. Optical coherence tomography analysis based prediction of humphrey 24-2 visual field thresholds in patients with glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58, 3975–3985 (2017).

Wong, D. et al. Comparison of machine learning approaches for structure-function modeling in glaucoma. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1515, 237–248 (2022).

Asaoka, R. et al. A joint multitask learning model for cross-sectional and longitudinal predictions of visual field using OCT. Ophthalmol. Sci. 1, 100055 (2021).

Christopher, M. et al. Deep learning approaches predict glaucomatous visual field damage from OCT optic nerve head en face images and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness maps. Ophthalmology 127, 346–356 (2020).

Hashimoto, Y. et al. Deep learning model to predict visual field in central 10 degrees from optical coherence tomography measurement in glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 105, 507–513 (2021).

Hemelings, R. et al. Pointwise visual field estimation from optical coherence tomography in glaucoma using deep learning. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 22 (2022).

Kihara, Y. et al. Policy-driven, multimodal deep learning for predicting visual fields from the optic disc and OCT imaging. Ophthalmology 129, 781–791 (2022).

Wintergerst, M. W. M., Jansen, L. G., Holz, F. G. & Finger, R. P. Smartphone-based fundus imaging-where are we now? Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. (Philos.) 9, 308–314 (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. ICSDA: a multi-modal deep learning model to predict breast cancer recurrence and metastasis risk by integrating pathological, clinical and gene expression data. Brief. Bioinform 23, bbac448 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Multi-modal deep learning model for auxiliary diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurocomputing 361, 185–195 (2019).

Yan, Q. et al. Deep-learning-based prediction of late age-related macular degeneration progression. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 141–150 (2020).

Xiong, J. et al. Multimodal machine learning using visual fields and peripapillary circular OCT scans in detection of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology 129, 171–180 (2022).

Xue, Y. et al. A multi-feature deep learning system to enhance glaucoma severity diagnosis with high accuracy and fast speed. J. Biomed. Inf. 136, 104233 (2022).

Dixit, A., Yohannan, J. & Boland, M. V. Assessing glaucoma progression using machine learning trained on longitudinal visual field and clinical data. Ophthalmology 128, 1016–1026 (2021).

Daneshvar, R. et al. Prediction of glaucoma progression with structural parameters: Comparison of optical coherence tomography and clinical disc parameters. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 208, 19–29 (2019).

Gordon, M. O. et al. Evaluation of a primary open-angle glaucoma prediction model using long-term intraocular pressure variability data: A secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 780–788 (2020).

Nouri-Mahdavi, K. et al. Prediction of visual field progression from OCT structural measures in moderate to advanced glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 226, 172–181 (2021).

Wen, J. C. et al. Forecasting future Humphrey Visual Fields using deep learning. PLoS One 14, e0214875 (2019).

Tian, Y. et al. Glaucoma progression detection and humphrey visual field prediction using discriminative and generative vision transformers. Ophthalmic Med. Image Anal. 14096, 62–71 (2023).

Hu, W. & Wang, S. Y. Predicting glaucoma progression requiring surgery using clinical free-text notes and transfer learning with transformers. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 37 (2022).

Fan, Y., Zhou, S., Li, Y. & Zhang, R. Deep learning approaches for extracting adverse events and indications of dietary supplements from clinical text. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. : JAMIA 28, 569–577 (2021).

Sugimoto, K. et al. Extracting clinical terms from radiology reports with deep learning. J. Biomed. Inf. 116, 103729 (2021).

Li, F. et al. A deep-learning system predicts glaucoma incidence and progression using retinal photographs. J. Clin. Invest 132, e157968 (2022).

Hollo, G. Comparison of structure-function relationship between corresponding retinal nerve fibre layer thickness and Octopus visual field cluster defect values determined by normal and tendency-oriented strategies. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 150–154 (2017).

Garway-Heath, D. F., Poinoosawmy, D., Fitzke, F. W. & Hitchings, R. A. Mapping the visual field to the optic disc in normal tension glaucoma eyes. Ophthalmology 107, 1809–1815 (2000).

Naghizadeh, F. & Holló, G. Detection of early glaucomatous progression with octopus cluster trend analysis. J. Glaucoma 23, 269–275 (2014).

Eslami, M. et al. Visual field prediction: Evaluating the clinical relevance of deep learning models. Ophthalmol. Sci. 3, 100222 (2023).

Johnson, C. A. et al. Baseline visual field characteristics in the ocular hypertension treatment study. Ophthalmology 109, 432–437 (2002).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770-778 (2016).

Howard, A. et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 1314-1324 (2019).

Huang, G. et al. Densely connected convolutional networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 4700-4708 (2017).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Hodapp, E., Parrish, R. K. & Anderson, D. R. Clinical decisions in glaucoma. Mosby Incorporated (1993).

Huang, X. et al. A structure-related fine-grained deep learning system with diversity data for universal glaucoma visual field grading. Front Med. (Lausanne) 9, 832920 (2022).

Aurenhammer, F. Voronoi diagrams—a survey of a fundamental geometric data structure. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 23, 345–405 (1991).

Huang, X. et al. GRAPE: A multi-modal dataset of longitudinal follow-up visual field and fundus images for glaucoma management. Sci. Data 10, 520 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82330032), National Natural Science Foundation Regional Innovation and Development Joint Fund (U20A20386), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2024C03204), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFC0118400) and Natural Science Foundation of China (82201195). We thank the Eye Center of the Third Hospital of Peking University for the contribution of the external dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.H., K.J. and J.Y. contributed to the conception and design of the study. X.H. and X.K. developed the methodology. X.H., Y.Y., Z.G., Z.L. and C.Z. performed the data acquisition and analysis. X.K. designed algorithm and program. X.H. and X.K. drafted the manuscript. K.J. and J.Y. were responsible for project administration, supervision and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Kong, X., Yan, Y. et al. Interpretable longitudinal glaucoma visual field estimation deep learning system from fundus images and clinical narratives. npj Digit. Med. 8, 389 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01750-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01750-8