Abstract

Emphysema progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presents a notable challenge due to its significant variability among individuals and the current lack of reliable prognostic markers. Given the limited therapeutic options available for emphysema, there is a critical need for early detection and intervention strategies. Identifying individuals at risk of rapid progression is essential to effectively halt or slow the disease’s advancement. This study introduces an innovative approach employing a localized foundational model of density evolution to pinpoint local radiographic embeddings indicative of emphysema progression. Central to our methodology is the Local Emphysema Progression (LEP) score, a novel metric derived from our model that aggregates localized lung tissue activations into a comprehensive, subject-level risk assessment tool. The model’s performance was tested on 3728 COPDGene participants, comparing baseline to 5-year, and 1421 scans taken from the 5-year to 10-year interval period. Additionally, our findings were replicated in 1058 ECLIPSE participants. The model effectively identifies lung regions with emphysema progression, achieving an AUC of 0.88. The LEP risk score shows good correlation with the change in the percentage of low attenuation areas below −950 Hounsfield Units (Δ%LAA-950), with correlation values of 0.50 in the COPDGene cohort and 0.40 in the ECLIPSE cohort among subjects with emphysema progression (Δ%LAA-950 > 0). Furthermore, LEP risk score associates with mortality and several COPD outcomes, underscoring its potential as a valuable tool in clinical prognosis and management of emphysema progression in COPD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emphysema, a lung disease characterized by abnormal and permanent enlargement of the distal airspaces1, exhibits varied extent and distribution within the lung, leading to heterogeneous spatial emphysema distribution 2,3. This destructive process of the lung tissue is thought to afflict over two million people in the US and is the pathobiological basis for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is one of the leading causes of death worldwide4,5. While most commonly due to chronic tobacco smoke exposure, emphysema is increasingly detected in never smokers without clear risks. Further, numerous studies including those reflecting the broader population have demonstrated that people with emphysema are at increased risk of death6,7,8,9. There is, therefore, great interest in developing therapies that target the underlying pathology of emphysema rather than just addressing its physiological symptoms10. However, aside from augmentation therapy for the small subset of people with Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), these efforts have had limited success. Image-based predictions can be a powerful tool to assess lobe-specific emphysema progression and provide lobe-specific treatments such as lung volume reduction.

The tool most commonly used to detect and quantify emphysema is computed tomography (CT) of the chest and extensive investigation has identified several image-based metrics of the lung tissue used in research and clinical care11,12,13. These range from measures of the density of the parenchyma14,15 to more advanced machine learning algorithms that can recognize different forms of disease and its distribution16,17,18,19,20,21,22, Clinical studies of emphysema are, however, challenging to conduct because the evolution of the disease is slow, and the regional heterogeneity of this process limits our ability to identify where in the lung this pathologic remodeling is most active23,24. Moreover, while we generally believe that people with emphysema will develop more emphysema, a therapy to heal destroyed lung tissue is likely more challenging to create than one that prevents its onset. The ability to predict where emphysema will develop in the lung may fill a critical gap that is currently preventing therapeutic development and optimal clinical management of patients at high risk of developing emphysema.

We hypothesized that a CT-based deep learning model could predict where emphysema would develop after learning the features that characterize its radiologic progression. To test this hypothesis, we leveraged longitudinal data from over 5000 people enrolled in one of two observational studies to identify lung-specific “embeddings” that described local emphysema progression (LEP), associated with the local onset of emphysema over a five-year period. A detailed description of the local emphysema progression can be found in the Methods and the Supplementary Fig. 5. These “embeddings” are mathematical representations of patterns embedded in the image, which are not evident on subjective review but are able to identify tissue that is most likely to become emphysematous. Once the embeddings of disease progression were identified, we then sought to test their ability to predict airspace dilation in a new set of longitudinal images that were not used for training.

Our deep learning approach leveraged a local foundational model (FM) of density evolution with an attention and scale mechanism where the model focuses on important details mimicking a cognitive attention mechanism25,26. The training involved: (1) image co-registration27, local densitometric assessment of the parenchyma (percentage of low attenuation areas below −950 Hounsfield Units, %LAA-950), and z-score image normalization. This was followed by (2) a conditional training strategy that balanced encoding emphysema progression information into the embeddings of the local FM, proper local reconstruction of the co-registered follow-up CT scan, and emphysema progression based on the change of %LAA-950 (Fig. 1). Once trained, the algorithm was applied to de-novo baseline CT scans using the following stepwise approach: (1) z-score image normalization; (2) inference of the local emphysema progression; (3) aggregation of the those spatial likelihoods of emphysema progression across the entire lung to create the Local Emphysema Progression Activity Map (Fig. 1), and finally (4) generation of a local emphysema progression score by aggregating local activations. Details are provided in the Methods section. We predicted the amount of emphysema progression each person would experience as well as estimated their clinical impairment due to that progression. We then compared those predicted metrics of progression to the same outcomes ascertained from serial observation.

This workflow diagram illustrates the process of local emphysema progression prediction using a local foundational model of density evolution. Starting with high-resolution CT scans, regions of interest (ROI) are identified and fed into the FM. The encoder part of the autoencoder compresses the ROI into a lower-dimensional representation z, which is then reconstructed back to the original data space by the decoder. The feature vector z is subsequently processed through a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to estimate the progression risk score. The risk score is depicted as the local emphysema progression. The final output includes the localized visualization of emphysema progression on the CT scan, highlighted for clinical assessment.

Results

Study participants

A total of 10,198 smokers with and without COPD were enrolled in the COPDGene27 study at phase 1 baseline (P1), and over 6000 participants came back for a second visit (P2) 5 years later. Our training and testing data consisted of 4712 COPDGene27 participants with complete data at baseline and the 5-year follow-up. This cohort included 1882 participants with Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) COPD grades I-IV expiratory airflow obstruction28 and 2805 smokers with normal lung function and preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm). For this study, we utilized the primary COPDGene spirometry data, which employed race-adjusted equations based on post-bronchodilator spirometry values, using NHANES race-specific equations and the 2023 GOLD criteria28. The local FM and LEP models were developed using 6.888 million lung patches of 32 by 32 pixels (0.64 mm2) from 984 randomly selected COPDGene participants at P1P2 with complete data (only 7000 patches by participant). Subjects were selected to keep the same GOLD severity distribution observed in our entire cohort (see Table 1). The LEP model’s performance was locally tested on 981.5 million patches from 795 COPDGene participants randomly selected from the test data at P1P2 (Supplementary Fig. 1—Local Reconstruction). In addition, LEP reproducibility was tested on a subset of COPDGene participants at phase 2 with a high- and low-dose protocol (n = 1421 and n = 41, Table 1) and complete data at 10-year later (P3), and 1058 ECLIPSE29 participants with complete data at baseline and 3-year follow-up. Details of these populations can be found in Table 1 and in the Supplementary Fig. 1.

Local prognostic model performance and reproducibility

We first studied the mean absolute error (std) of the LEP model predictions on 981.5 million patches from 795 randomly selected COPDGene participants from phase 1 to phase 2 (P1P2) not included in the training dataset (around 1.23 million patches by participant). In general, the LEP prediction shows a small MAE = 4.4% (7.7%). This error increased along with the COPD status with values of 1.6% (4.7), 2.9% (6.5%), 6.1% (8.8%), 5.8% (8.3%), 9.1% (8.8%) and 10.7% (8.8%) for PRISm, controls, GOLD 1 to 4, respectively.

Then, we explored the performance of the LEP model to determine whether the model could effectively discriminate between regions of lung tissue stability and those showing emphysema progression (regions with > 5% LEP voxels, i.e. voxels than transition from tissue to air). Analyzing the patches described before (981.5 million patches from 795 COPDGene participants P1P2), our model demonstrated a robust Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.88. At an operating point that maximizes the Youden’s index on the training dataset (probability th = 0.158), the model’s sensitivity (Sens.), positive predictive value (PPV), accuracy (ACC), F1-score, and Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (K) were Sens. = 0.55, PPV = 0.60, ACC = 0.85, F1 = 0.58, and K = 0.49, respectively.

When the model was applied to COPDGene participants from phase 2 to phase 3 (P2P3) under a high-dose protocol (n = 2464 million patches, 1.3 million patches by participant), the model’s performance metrics remained consistent (AUC = 0.88, Sens.=0.64, PPV = 0.53, ACC = 0.85, F1 = 0.59, and K = 0.50). However, in the subset evaluated with a low-dose protocol at P2P3, a slight reduction in performance was observed (AUC = 0.84, Sens. = 0.61, PPV = 0.45, ACC = 0.83, F1 = 0.52, and K = 0.42) with decrements of 4.5%, 4.7%, 15%, 2.3%, 11.8% and 16% in AUC, sensitivity, PPV, ACC, F1-score, and K, respectively.

Additionally, we observed that the performance of our model was generally consistent across different baseline disease severities, except in the case of severe emphysema. We categorized the subjects into four groups based on baseline emphysema severity (no emphysema 0-5% (n = 563), mild 5-10% (n = 109), moderate 10-20% (n = 70), and severe ≥ 20% (n = 53)) and generated Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for each group by aggregating the per-subject ROC curves within the same emphysema severity group measured at baseline. These curves demonstrated an AUC ≥ 0.78 for the milder groups (no emphysema, mild, and moderate) in high-dose CT scans with a slight drop in performance for subjects with advanced emphysema at baseline (Fig. 2a, b), and an AUC of ≥0.73 for low dose scans (Fig. 2c).

The LEP model was evaluated on test subjects from the COPDGene cohort with high-dose CT scans from phase 1 to phase 2 (P1P2) and phase 2 to phase 3 (P2P3). We also evaluated the model robustness in 41 participants with low-dose CT scan from Phase 2 to Phase 3. ROC curves for the detection of local emphysema progression. Local emphysema progression was defined as more than 5% of the pixels within a local patch transitioning from tissue (CT density > -950 HU) to air (CT density <=-950 HU). LEP Local Emphysema progression, E Emphysema measured at baseline.

To enhance the interpretability of our model, we conducted a visual evaluation of the local FM predictions, which reconstructed the 5-year CT patches from the baseline scans. The results for various patches, representing subjects with differing disease burdens and progression rates, are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Local emphysema progression activity maps

We computed subject-level maps of emphysema progression activity by sequentially running the LEP model across the lung parenchyma and aggregating the probability outputs of local progression. Figure 3a shows the LEP activity maps for four subjects with different degrees of severity. Our model is able to detect incipient regions of the parenchyma most likely to progress to emphysema in a subject without emphysema at baseline and without change in their clinical staging by GOLD guidelines (GOLD stage 2) during the 5-year follow-up (Fig. 3 (a-No Emphysema). Figure 3 (a-Mild) shows a strong spatial correlation between the model’s LEP prediction and the measurement at 5-year, where the model effectively identifies specific regions in the lung where the progression activity is concentrated. Additionally, Fig. 3a shows that the model is not merely identifying local regions with emphysema at baseline (Mild and Severe). A visual inspection of several patches confirms the same local behavior (see Supplementary Note and Supplementary Fig. 2). In cases with more advanced disease stages (moderate to severe emphysema and GOLD stages 2 and 3), the LEP activity maps were also able to capture the heterogenous pattern of emphysema progression (Fig. 3 (a -Moderate and Severe). This visual demonstration underscores the model’s precision in predicting emphysema progression, highlighting its potential clinical utility.

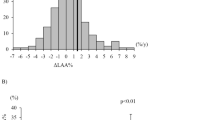

a LEP Activity Maps for four subjects with different degrees of severity. The model’s prediction (i.e., LEP activity map) is plotted over the co-registered CT scan in purple (bottom row), while the observed emphysema at baseline is depicted in brown in the first row. The observed emphysema progression based on the change in CT density of %LAA-950 between baseline and follow-up is depicted in green in the second row. LEP: Local Emphysema Progression; EP: Emphysema Progression. b Distribution of the LEP risk score on subjects at P1P2 stratify by Pre-COPD (excluding PRISm) and GOLD stages; and c by Low/High %LAA-950.

Association of LEP risk score and emphysema progression

The LEP activity maps serve as the foundation for creating a subject-level emphysema progression risk metric known as the LEP score. The score is calculated as the mean binary local activation at the threshold that maximizes Youden’s index (probability th = 0.158) across the entire lung parenchyma. A comprehensive explanation of the LEP risk score methodology is detailed in the Methods section.

We examined the relationship of the LEP risk score and emphysema progression, quantified as the change of %LAA-950 (Δ%LAA-950), in 3728 COPDGene participants at P1P2, and in 1058 participants of our replication cohort, ECLIPSE. A positive change of the %LAA-950 (indicative of progression) signals an increase of the emphysema by P2, whereas a negative change corresponds to an increase in voxels above the −950 HU threshold at P2. While emphysema is understood as an irreversible process, lung density can increase due to technical and physiological factors like scanner parameters, inflation levels, smoking resumption and underlying inflammatory processes during disease activity that could potentially lead to emphysema. On the other hand, higher LEP scores indicate a greater risk of emphysema progression.

The correlation between the LEP score and Δ%LAA-950 among participants with emphysema progression (Δ%LAA-950 > 0%) was 0.59, and −0.57 among those with an increase in lung density (i.e., Δ%LAA-950 ≤ 0) (see Supplementary Fig. 3). In the ECLIPSE replication cohort, the corresponding correlations were 0.40 and −0.44, respectively, further supporting our findings in COPDGene. This pattern suggests that the LEP score captures not only emphysema progression but also potential inflammatory or reparative processes that may precede or counteract tissue destruction. The variability in model correlation observed between the COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts (−27.5%) is primarily attributed to differences in CT acquisition protocols—including noise characteristics—and scanner manufacturers. To further investigate this, we assessed the model’s performance across different scanner brands within the COPDGene cohort. The correlation between the LEP score and Δ%LAA-950 varied by scanner type, with values of −8.6% for Siemens, 10.4% for GE, and 14.3% for Philips scanners, relative to the correlation computed across all COPDGene participants (see Supplementary Table 2). This comparison provides useful insights into the potential influence of scanner-related variability on model performance; however, because the same subjects were not scanned across different scanner manufacturers, definitive conclusions about the effect of scanner type on variability cannot be drawn.

We then stratified the correlation between the LEP score and Δ%LAA-950 by COPD severity (GOLD 0–IV) among COPDGene participants. For those with emphysema progression (Δ%LAA-950 > 0), the correlations were 0.33 for GOLD 0, 0.33 for GOLD I, 0.49 for GOLD II, 0.34 for GOLD III, and 0.27 for GOLD IV. Among participants with stable or increasing lung density (Δ%LAA-950 ≤ 0), the corresponding correlations were −0.65, −0.45, −0.54, −0.47, and −0.09 for GOLD stages 0 through IV, respectively.

Additionally, when stratifying participants based on Δ%LAA-950 quartiles in the COPDGene dataset, the correlation values were −0.48 for Δ%LAA-950 < −0.87% (25th percentile), −0.26 for values between −0.87% and 0.00% (25th to 50th percentile), 0.26 for values between 0.00% and 1.07%, and 0.47 for values ≥ 1.07% (75th percentile). In the ECLIPSE replication cohort, the corresponding correlations were −0.48, −0.26, 0.25, and 0.47, respectively.

Association of local emphysema progression risk score with prospective outcomes

In the COPDGene LEP Score test group (P1P2, n = 3728), we examined the association of LEP risk scores and Δ%LAA-950 with various COPD outcomes by fitting a multivariate linear model adjusted by the following covariate variables measured at baseline: age, gender, race, emphysema, BMI, TLC, smoking status, and packs per year (see Data and statistical analyses section on Online Methods). Emphysema progression was classified as “fast” or “slow” based on %LAA-950 changes above 0.66%. Emphysema progression risk was categorized as “high-risk” or “low-risk” using an LEP score threshold above 0.15. We established these thresholds at the 70th percentile of the participants in the “LEP score” test.

LEP scores were significantly correlated with COPD severity, increasing from 0.065 in smoking controls to 0.49 in GOLD 4. As expected, LEP risk scores also rose with emphysema progression from 0.099 (slow) to 0.236 (fast) (see Fig. 3b, c). The mean (std) LEP values for slow and fast progressors according to Δ%LAA-950 were 0.06 (0.10) and 0.08 (0.11) for smoking controls, 0.16 (0.17) and 0.21 (0.19) for GOLD 1, 0.14 (0.17) and 0.24 (0.21) for GOLD 2, 0.30 (0.23) and 0.40 (0.23) for GOLD 3, and 0.45 (0.20) and 0.50 (0.20) for GOLD 4.

Table 2 summarizes the associations between the LEP risk score and Δ%LAA-950 across various COPD outcomes. Statistically significant differences were observed in the 5-year FEV1/FVC ratio and DLCO between low and high-risk groups for the LEP score and slow vs fast progressors for Δ%LAA-950 (p < 0.001). Patients classified as high risk based on their LEP score showed lower FEV1/FVC ratios and DLCO values. Additionally, the high-risk group, as per LEP scores, exhibited a greater decline in FEV1 (approximately 12 ml/y; −46.51 vs. −34.80, p < 0.001) and a larger decrease in exercise capacity (about 40 feet; −168 vs. −127.4, p < 0.001) than low-risk subjects, indicating a worsening of their disease condition. In contrast, Δ%LAA-950 showed a less pronounced impact on those outcomes between slow and fast progressors (approximately 0.31 ml/y in the difference of FEV1 change, p = 0.03; and about 26 feet in the exercise capacity, p = 0.83). Additionally, Table 3 shows the outcome distribution of four risk groups defined according to the quartiles Q1 = 0%–25%, Q2 = 25%–50%, Q3 = 50%–75%, and Q4 = 75%–100%.

Survival analysis

Lastly, we evaluated the prognostic utility of the LEP risk score by conducting a survival analysis. Kaplan-Meier estimator was utilized to delineate survival trajectories, and the Cox proportional hazard model assessed the significance of the risk stratification. Adjustments in the Cox model accounted for an array of covariates measured at baseline including age, gender, race, emphysema, body mass index (BMI), total lung capacity (TLC), smoking status, and pack-years of smoking. A second survival model included those covariates and FEV1.

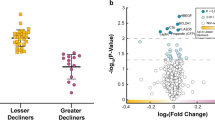

As depicted in Fig. 4a, our analysis within the COPDGene test cohort (P1P2, n = 3728). revealed distinct survival trajectories that paralleled the classification of patients with fast/slow Δ%LAA-950 progression and high/low LEP risk. Notably, individuals presenting with high LEP scores or those exhibiting a rapid increase in Δ%LAA-950 were associated with an elevated risk of mortality when compared to their respective reference cohorts. Hazard ratios were notably higher in these groups, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.56 for high LEP scores and 1.37 for fast Δ%LAA-950 progression, underscoring the predictive relevance of these biomarkers in survival outcomes (refer to Fig. 4b and c). While smoking status exhibits a consistent influence across both models, the LEP score emerges as a particularly significant determinant in the context of emphysema progression and its impact on mortality. Additionally, when the Cox model is adjusted for spirometric measures, such as FEV1, the significance of LEP and Δ%LAA-950 is lost (LEP score p value = 0.06 and Δ%LAA-950 p value = 0.22) because the impact of spirometric measures on mortality is greater than that of emphysema—particularly due to PRISm participants. However, in subjects with high emphysema percentage, for example, %LAA-950 > 10%, the impact of emphysema on mortality increases. This is illustrated in Fig. 5b where the LEP score emerges as a particularly significant determinant of mortality impact when stratified by emphysema severity. Additionally, Supplementary Fig. 4 presents a survival analysis restricted to the pre-COPD group (excluding PRISm) and GOLD 1–2 stages, in which the LEP score remains significantly associated with mortality even after adjusting the cox model for FEV1. This may appear to contrast with earlier analyses suggesting that the prognostic performance of our model declines as emphysema severity increases. Nevertheless, this can be explained by considering both the structural limitations in advanced disease and the shifting contributions of different risk factors to mortality. As baseline emphysema severity increases, the amount of preserved lung tissue available for prediction decreases. Severely emphysematous regions are less likely to undergo further progression, meaning they contain less information about future structural decline. As demonstrated in the local prediction analyses, this reduction in viable tissue reduces the model’s precision for predicting local emphysema progression, with the mean absolute error (MAE) increasing from 1.6% in Prism participants (mean emphysema = 1.51%) to 10.7% in GOLD 4 participants (mean emphysema = 23%) (section “Local Prognostic Model Performance and Reproducibility”). Despite this decline in predictive precision, the LEP score remains associated with mortality in individuals with greater emphysema burden, because the relative contribution of emphysema to mortality increases as its extent grows. While spirometric measures (such as FEV₁) generally have a stronger influence on mortality than emphysema alone, in subjects with more extensive emphysema—such as those with %LAA-950 greater than 10% (mean emphysema values for GOLD 3 and GOLD 4 in COPDGene are 13% and 23%)—emphysema becomes a more prominent driver of mortality risk. In this setting, the LEP score continues to reflect clinically meaningful risk, even if its ability to predict future tissue destruction is reduced. To further support this point, Fig. 6 presents the association between the LEP score and mortality specifically in GOLD 4 participants. To ensure sufficient statistical power, we defined the at-risk population as those with LEP scores above the mean, identifying 42 high-risk individuals out of 84 GOLD 4 participants. Using a higher percentile threshold (e.g., the 70th percentile) would have reduced the number of events and limited the power of the Cox proportional hazards model. As expected, the results show that the LEP score retains its prognostic value, while FEV₁ loses its statistical significance—likely due to reduced power—despite maintaining a high hazard ratio. These findings affirm the prognostic significance of the LEP score in identifying patients at a higher risk of adverse outcomes, thus offering a potent tool for personalized patient management and intervention strategies.

a Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrating the differential impact of Δ%LAA-950 and LEP score categories on the survival of patients in the COPDGene study (n = 3728). Patients were stratified into two groups based on Δ%LAA-950 (slow and fast emphysema progression) and into two groups based on LEP scores (low and high risk). Forest plot of the Cox model for Δ%LAA-950 (b) and LEP score (c) adjusted for baseline covariates, showing the log(HR) for mortality risk associated with fast progressors and high-risk after adjustment for clinical and demographic factors. Both models underscore the enhanced risk of mortality associated with higher LEP scores and faster emphysema progression, independent of other risk factors.

Cox Proportional-Hazards analysis for high/low LEP risk and fast/slow emphysema progression in (a) the COPDGene study (n = 3728) and (b) on COPDGene participants with emphysema at baseline higher than 10% (n = 576). The Cox model is adjusted for baseline covariates including FEV1, showing the log(HR) for mortality risk associated with fast progressors and high-risk after adjustment for clinical and demographic factors.

Discussion

In this study, we introduce a novel Localized Emphysema Progression (LEP) model, utilizing a temporal autoencoder with an attention mechanism to define and evaluate image embeddings, or “deep features”, as potential tools for use in more advanced prognostic models to predict COPD outcomes, such as changes in %LAA-950. Our model uses baseline CT images to predict future progression, and it highlights the potential of utilizing baseline imaging data to anticipate disease trajectory. The LEP score may prove to be an invaluable tool for monitoring disease progression and informing treatment strategies for patients with COPD. The study’s findings also open avenues for future research. For example, this approach can be integrated with follow-up exams in future models to enhance monitoring capabilities and treatment planning, representing a significant step towards more sophisticated and practical prognostic tools in clinical settings.

Our intent is not to provide the most finely tuned prognostic model or an activity map of lung destruction. The necessity of our model being a true auto-encoder is crucial; it must have a bottleneck to ensure that the encoded information of the evolution of emphysema progression (EP) is entirely encapsulated in the latent space (image embeddings) rather than being distributed across multiple layers. The U-Net architecture does not adhere to this requirement, as information flows through the skip connections at various levels, which could dilute the purpose of encoding progression into a compact latent representation.

The model’s ability to accurately predict 5-year local emphysema progression from baseline CT scans underscores its potential in early identification of patients at elevated risk. Its capacity to localize the evolution of emphysema and detect subjects on a rapid progression trajectory is a distinctive feature, offering invaluable insight not easily attained by other methodologies30. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are currently no existing models specifically designed to predict regional or lobar emphysema progression without follow-up imaging, and therefore no established baseline for direct comparison. We acknowledge this as a limitation. Nonetheless, the proposed LEP model may serve as an initial reference framework for future research aiming to develop and validate standardized benchmarks. Establishing such benchmarks will be essential for enabling comprehensive evaluation and comparison of emerging methodologies in this field.

We propose an emphysema risk score—referred to as the LEP score—by aggregating localized progression data generated by our model to provide a subject-level risk score. A key finding of our study is that high LEP scores are associated with both increases and decreases in %LAA-950 over five years, reflecting the underlying heterogeneity of COPD phenotypes. Specifically, a high LEP score accompanied by an increase in %LAA-950 is indicative of true emphysema progression, likely driven by localized parenchymal destruction and consistent with biological mechanisms such as protease-antiprotease imbalance, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation. In contrast, a high LEP score accompanied by a decrease in %LAA-950 may reflect airway-predominant phenotypes or PRISm, non-parenchymal remodeling, underlying inflammation, or technical factors such as variability in lung inflation during image acquisition. This seemingly counterintuitive finding is consistent with emerging theories that emphasize disease activity and unregulated inflammatory responses as central to emphysema progression24,31. In such cases, increased inflammation may transiently elevate lung density, thereby reducing %LAA-950 and potentially masking true structural decline on longitudinal imaging32,33. Notably, the LEP score appears capable of identifying these individuals despite misleading imaging trends. Integrating additional clinical and imaging biomarkers—such as gas trapping, airway wall thickness, and spirometry—may further improve the interpretability of LEP-based predictions and enhance our ability to distinguish between emphysema- and airway-predominant phenotypes.

Our findings also suggest that in high-risk individuals, a lung function decline which is more pronounced in high-risk groups identified by the LEP score compared to slow and fast progressors identified by Δ%LAA-950 (−46.1 vs. −38.2 and −38.5). While some changes may not indicate clinical improvement per se, they can reflect an underlying trend toward worsening condition—such as dyspnea—particularly when evaluated across groups stratified by risk. For example, in Table 2, the mMRC change from Q1 to Q4 of the LEP score (from −0.1 to 0.2) suggests a progressive increase in perceived breathlessness. This supports the notion that higher LEP scores are associated with a trajectory of worsening respiratory symptoms, even if the magnitude of change falls below the MCID threshold. These findings underscore the nuanced capability of our model in differentiating progression trajectories in COPD patients and highlight the potential of the LEP model in recognizing patients who might benefit from early interventions.

Model performance declined with increasing COPD severity as defined by GOLD stages. Although this may appear counterintuitive, advanced COPD—particularly at GOLD 4—is characterized by extensive parenchymal destruction and markedly reduced lung tissue density. This loss of density limits the information available for prediction, making it more difficult for the model to correlate LEP scores with emphysema progression. The non-linear trend in correlations across disease stages reflects the progressive degradation of lung structure and the resulting loss of distinct density patterns essential for accurate predictions. Despite the reduced predictive precision at later stages, the LEP score remains associated with mortality in individuals with greater emphysema burden, as the impact of emphysema on mortality increases with disease extent. To enhance model performance in advanced disease, we are investigating an extension of our local foundational model to a fully 3D representation of the lung, which may better capture the spatial complexity of severe emphysema. However, such a transition would require a larger sample size to avoid overfitting and ensure generalizability.

Fast-slow and high-low risk categories for emphysema progression were initially defined at the 70th percentile of participants in the “LEP score” test, though alternative thresholds are possible. We decided to use this percentile rather than the median value (50%) for two main reasons: (1) to define a population at higher risk than just the mean value and (2) to define a population with a reasonable prevalence of 30%. However, the 75th percentile with a lower prevalence (25%) is also a valid approach. Using the 75th percentile we observed a decline in the model’s performance by approximately 3% due to the reduced prevalence of subjects in the fast-low and high-low risk categories for emphysema progression.

Effects of variability, such as CT scanner type, acquisition and reconstruction, will influence our method to predict emphysema progression. Our findings indicate that reduced dose impacts the accuracy of the method by approximately 10%. To address the variability introduced by different CT scanner types, we trained our model using a multicenter cohort. This approach helps to mitigate this issue by encompassing a diverse range of scanner types and settings, enhancing the generalizability and robustness of our model across different clinical environments. The method used for co-registration was specifically designed to be robust against large deformations, with an error below 1.3 mm on the DIR-Lab dataset (expiration to inspiration)34. Additionally, our registration is inherently less challenging since we are aligning longitudinal inspiration images, where the degree of lung volume change is less significant than in expiration to inspiration. Evaluating all possible confounders is challenging, as it would require scanning several patients with varying COPD statuses on different scanners and using different kernels. To overcome this limitation, we studied the effect of high and low doses to provide an idea of the impact of these confounders on our method. The data presented on reproducibility under significant changes in protocol show that the model is robust to changes in noise. To further investigate the impact of variability due to CT scanner type, we evaluated the model’s performance across different scanner brands within the COPDGene cohort. The correlation between the LEP score and Δ%LAA-950 varied by approximately 12% relative to the correlation computed across all COPDGene participants. However, because the same subjects were not scanned across different scanner manufacturers, definitive conclusions regarding the effect of scanner type on variability cannot be drawn. Nonetheless, this comparison provides useful insights into the potential influence of scanner-related variability on model performance.

Clinical implications and integration into practice

Risk Stratification and Prognosis: The LEP score offers an objective, imaging-based biomarker for identifying individuals at elevated risk of emphysema progression without the need for longitudinal studies. This is particularly important in early stages of COPD (GOLD 1–2) and Pre-COPD (excluding PRISm), where traditional spirometry may not fully capture the risk of structural lung damage. By quantifying the likelihood of progression before significant lung function decline occurs, the LEP score enables early identification of high-risk individuals who may benefit from closer monitoring and earlier intervention.

Personalized Treatment Planning: The LEP activity maps generated by our model offer valuable insight into the spatial distribution of emphysema progression, thus offering a more comprehensive understanding of the disease. These maps could help clinicians understand lobe-specific patterns of disease progression, potentially enabling the development of personalized treatment strategies before irreversible damage occurs—for example, lobe-targeted interventions such as lung volume reduction. Additionally, our model opens new avenues for the mechanistic understanding of emphysema progression through imputed phenotypes. While new molecular platforms, such as spatial transcriptomics, are offering unique insights into the mechanisms underlying various diseases35 destructive nature of longitudinal sampling. However, our model circumvents this limitation by providing an alternative, non-invasive means of assessing emphysema progression, leveraging spatial data without the need for repeated lung biopsies.

Clinical Trials and Drug Development: In research and drug development contexts, the LEP score could serve as an enrichment tool for clinical trials targeting emphysema-modifying therapies. By selecting participants with higher predicted progression rates, trials can improve statistical power and evaluate therapeutic effects more efficiently. Additionally, the score could potentially serve as a surrogate endpoint to assess treatment response in early-phase studies.

While our study benefits from a large sample size that includes a substantial proportion of African American participants (30%), other racial and ethnic groups remain underrepresented. Moreover, our replication cohort consists predominantly of Non-Hispanic White individuals. These factors may limit the generalizability of our findings, particularly to populations not adequately represented in our training and validation cohorts. Future studies should aim to include more diverse populations to ensure equitable applicability of predictive models across all patient groups.

In addition, while our findings support the clinical potential of the LEP score, it is important to note that the model was trained and evaluated primarily on cohorts of smokers. As such, its applicability to non-smoker phenotypes—such as those observed in individuals with Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency or biomass exposure—remains to be validated. Ensuring relevance across the full spectrum of COPD phenotypes will require extending model development to include a broader range of exposure profiles and clinical characteristics.

Variability introduced by technical factors—such as differences in CT scanner type, acquisition protocols, and reconstruction algorithms—may also influence our model’s ability to predict emphysema progression. Addressing these sources of heterogeneity will be critical for translating our findings into clinical practice—for example, through image harmonization techniques.

The heterogeneity and often non-linear nature of COPD progression underscore the importance of incorporating both imaging and functional markers when interpreting model predictions. Future work will aim to further investigate the biological mechanisms underlying our findings by integrating additional imaging features—such as gas trapping and airway wall metrics—alongside molecular and clinical data, to more precisely characterize the pathophysiological basis of the model’s predictions across diverse COPD phenotypes. Expanding the size and diversity of the study population will also create opportunities to extend our local foundational model to a fully 3D representation of the lung. This advancement could enhance predictive accuracy, particularly in individuals with advanced disease (e.g., GOLD 4), by capturing the complex spatial patterns of parenchymal destruction that are often missed in lower-dimensional models.

Methods

Local emphysema progression (LEP) definition and ground truth generation

The method proposed was designed to identify local deep phenotypes by learning the local emphysema evolution according to the percentage of low-attenuation area (%LAA-950). In this way, we defined the Local Emphysema Progression (LEP) as those pixels that change from lung tissue at baseline CT scan to air at a 5-year follow-up co-registered CT scan, i.e. the pixel density decays from a value of > −950 HU at baseline to a value of ≤ −950 HU at 5-year follow-up co-registered CT scan. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows an example of the LEP definition where the pixels that change from lung tissue at baseline (a) to air (b) are plotted in green over the follow-up co-registered CT scan (c).

Deep local emphysema progression model

The method proposed for predicting the local evolution of the emphysema at 5-years combines a local foundational model of density evolution with a multilayer perceptron (Fig. 1)36. The local FM is fitted to encode useful information about the evolution of the local density patterns at a 5-year follow-up co-registered CT scan. In particular, the local FM is trained in a neighborhood of 32 by 32 pixels (0.64 mm2) to reconstruct the same neighborhood in a 5-year follow-up co-registered CT scan. Using 2D patches instead of 3D patches allowed us to leverage a larger amount of training data, which is crucial for building a robust model. The trade-off between the complexity of predicting local 3D volumes and the training data requirements was carefully considered. Given the current computational constraints and the complexity of 3D reconstruction over a five-year period, we determined that a 2D approach would be more effective and stable for our purposes. It is worth noting that our results based on a 2D local autoencoder are quite promising. Once the foundational model was successfully trained (examples of the reconstruction can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 2), a multilayer perceptron (MLP) was trained to regress the local emphysema progression or LEP, according to the %LAA-950. This process is carried out using a conditional strategy in three stages, i.e., for each batch in a particular epoch, the whole model is fitted in three sequential steps as follows:

-

First, the MLP is fitted with the embeddings from the local FM, i.e., the output of the encoder (see Fig. 1).

-

Second, the encoder part of the local FM is fine tunned to improve the embeddings representation of emphysema progression. In this step, the decoder part of the FM and the MLP model are not trained; they remain fixed.

-

Third, the local FM is re-trained to maintain an acceptable local reconstruction. In this step the MLP model remains fixed.

The conditional training strategy allows the LEP model to keep a balance between encoding useful information of the emphysema progression into the embeddings, z, the local density reconstruction in the follow-up CT scan, and the predicted LEP. The reconstruction loss function, i.e., the local FM loss, is defined to incorporate information about the emphysema measured at the 5-year follow-up, the emphysema progression and the emphysema subtypes measured at baseline. The rationale for introducing emphysema subtyping is to acknowledge that different subtypes exhibit distinct patterns of progression based on their severity. The subtype masks are pre-computed at the pixel level using a local histogram-based emphysema (LHE) method described in refs. 37,38. These masks are only used for computing the loss function and are not involved in the inference process.

Model Architecture

The MLP is defined as a sequence of four dense blocks with 300 neurons and one with 200 neurons. Each block consists of a dense layer, a batch normalization and a dropout strategy with a ratio of 40%. According to the results described in ref. 39 we decided to use the swish function as activation. The output of the MLP corresponds to a sigmoid function, and the mean absolute error was proposed as a loss function to regress the LEP. In contrast to the simplicity of the MLP model, the autoencoder proposed makes use of two Kernel Sharing Atrous Convolution (KSAC)26 with rates of 2 and 4, and five Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM)25 with different strides. These attention blocks are critical for capturing detailed information about emphysema progression and lung density decline. This mechanism is not required in the decoder path because our primary objective is not image reconstruction or segmentation but rather encoding useful information about density evolution and emphysema progression. This design choice allows us to focus on capturing detailed information about the formation process of parenchymal destruction without the influence of global features that could bias the results and reduce interpretability. A detailed description of this architecture can be found in the Supplementary Table 1. Like the MLP, the local FM uses the swish function as activation for all the layers except for the embeddings, z, and the output, where a linear activation is used. After each convolution, including those in KSAC and CBAM, a batch normalization strategy is applied.

Emphysema subtype specific loss function

The reconstruction loss function, i.e. the FM loss, is defined to incorporate information about the local emphysema measured at the 5-years follow-up, its subtypes measured at baseline and its progression. Let y(i) a patch of 32 by 32 pixels in a 5-years co-register follow-up scan, and \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{y}}}\) (i) its predicted reconstruction. Then, the FM loss is defined as follows:

where Lr corresponds to the mean absolute error

And \({L}_{{\rm{r||}}(.)}\) corresponds to the mean absolute error of the pixels with emphysema progression (\({L}_{{\rm{r||lep}}}\)), emphysema at 5-year (\({L}_{{\rm{r||e}}}\)), lung tissue (\({L}_{{\rm{r||e}}}\)), i.e., > -950HU, pixels predicted as emphysema (\({L}_{{\rm{r||e}}}\)), i.e. \(\le\)-950 HU, or pixels with a particular emphysema subtype (\({L}_{{\rm{r||s}}}\)). We propose to use the emphysema subtype37,38 to weight each patch, \({{\boldsymbol{y}}}^{\left(i\right)}\), according to the weights, \({S}_{{\rm{w}}}\), as follows: 0.4, 0.8, 1, 0.3, 0.2 and 0.2 for paraseptal emphysema, centrilobular emphysema (mild, moderate, and severe), panlobular emphysema and normal parenchyma respectively. The notion for introducing emphysema subtype is to acknowledge that different subtypes have different patterns of progression based on their severity. The weights were set a priori to reflect that severity, so different local patches belonging to different emphysema subtypes would be a different evolution.

Training

Our model was trained using 6.888 millon of lung patches of 32 by 32 pixels (0.64 m2) from 984 COPDGene participants randomly selected from our cohort (only 7000 patches by participant) keeping a balance between neighborhoods with a high/low number of pixels with emphysema progression (high > 25%). A z-score normalization was applied to the lung regions according to the mean and std values of the training dataset. The optimization was performed using a stochastic gradient descent (Adaptive Moment Estimation) with a learning rate of 5 ×10−5 for pre-training training the AE, and the learning rates used in the conditional training strategy were set to 1 ×10−4, 1 ×10−5, and 1 ×10−5 for the MLP (stage 1), the encoder (stage 2) and the AE (stage 3) respectively.

Data augmentation was used to teach the model the desired invariance and robustness properties. Heterogeneity in the neighborhoods is needed for the network to learn flips and rotation. With this intention, the input of the network was randomly deformed by means of spatial flips (both axes) and a rotation of ±90°. One or more deformation can be sequentially combined during the training and no interpolation is needed.

Local emphysema progression activity map

The inference of the LEP activity map is done by sliding the encoder plus the MLP across the whole lung with a stride of 4 pixels and aggregating the predicted probabilities. Finally, the local emphysema activity map is normalized according to the overlapping due to the sliding process.

Local emphysema progression (LEP) risk score

The LEP risk score is defined according to the following procedure: (1) the local emphysema progression at 5-year is estimated across the entire lung parenchyma with a stride of 4 pixels using the temporal encoder; (2) each region is defined as stable or progressing according to the threshold that maximizes the Youden’s index on the training population (probability th = 0.158); (3) The LEP score is computed as the number of regions within the lung parenchyma predicted to progress at 5 years, as defined in (2), normalized by the total number of regions in the lung. This value ranges from 0, indicating that no regions are predicted to progress, to 1, indicating that all regions are predicted to progress. It represents the proportion of lung tissue at risk of future emphysema progression.

Data and statistical analyses

Multivariate linear models were used to explore the association of the LEP risk score and the change of the %LAA-950 (Δ%LAA-950) in relation to various COPD outcomes. The linear models were adjusted using baseline covariate variables commonly applied in studies of emphysema progression, such as the one described in10: age, gender, race, emphysema, BMI, TLC, smoking status, and packs per year. Results were reported as the adjusted covariance means and the ordinary least square difference (Diff.) for each group (low/high risk of LEP, and slow/fast progressors according to Δ%LAA-950). Statistically significant results are considered with p-value ≤ 0.05 on a Student’s t-test. All data are presented as the mean (SD).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available because they are the property of the COPDGene study. However, researchers can request access to the data upon request.

Code availability

The source code for deep-phenotypes detection and validation will be incorporated into the Chest Imaging Platform (www.chestimagingplatform.org) –the open-source software library that we have developed in our group over the last ten years and continue to support.

References

Marin, L., Colombo, P., Bebawy, M., Young, P. M. & Traini, D. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: patho-physiology, current methods of treatment and the potential for simvastatin in disease management. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 8, 1205–1220 (2011).

Valipour, A. et al. Patterns of emphysema heterogeneity. Respiration 90, 402–411 (2015).

Castaldi, P. J. et al. Heterogeneity and progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: emphysema-predominant and non–emphysema-predominant disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 192, 1647–1658 (2023).

World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd). 12, 2025 (2024)

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Martinez, F. J. et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with emphysema and severe airflow obstruction. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 173, 1326–1334 (2006).

Gietema, H. A. et al. Distribution of emphysema in heavy smokers: Impact on pulmonary function. Respir. Med 104, 76–82 (2010).

Lynch, D. A. et al. CT-based visual classification of emphysema: Association with mortality in the COPDGene study. Radiology 288, 859–866 (2018).

Tang, X. et al. Emphysema is an independent risk factor for 5-year mortality in patients with bronchiectasis. Clin. Respiratory J. 11, 887–894 (2017).

Ash, S. Y. et al. Relationship between emphysema progression at CT and mortality in ever-smokers: results from the COPDGene and ECLIPSE Cohorts. Radiology 299, 222–231 (2021).

Newell, J. D., Hogg, J. C. & Snider, G. L. Report of a workshop: quantitative computed tomography scanning in longitudinal studies of emphysema. Eur. Respiratory J. 23, 769–775 (2004).

Gietema, H. A. et al. Monitoring of smoking-induced emphysema with CT in a lung cancer screening setting: detection of real increase in extent of emphysema. Radiology 244, 890–897 (2007).

Milne, S. & King, G. G. Advanced imaging in COPD: Insights into pulmonary pathophysiology. J. Thorac. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.11.30 (2014).

Parr, D. G., Sevenoaks, M., Deng, C., Stoel, B. C. & Stockley, R. A. Detection of emphysema progression in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency using CT densitometry; Methodological advances. Respir. Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-9-21 (2008).

Dirksen, A. et al. Exploring the role of CT densitometry: a randomised study of augmentation therapy in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Eur. Respiratory J. 33, 1345–1353 (2009).

van Ginneken, B. Fifty years of computer analysis in chest imaging: rule-based, machine learning, deep learning. Radio. Phys. Technol. 10, 23–32 (2017).

Uppaluri, R., Mitsa, T., Sonka, M., Hoffman, E. A. & McLennan, G. Quantification of pulmonary emphysema from lung computed tomography images. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156, 248–254 (1997).

Ginsburg, S. B., Lynch, D. A., Bowler, R. P. & Schroeder, J. D. Automated texture-based quantification of centrilobular nodularity and centrilobular emphysema in chest CT images. Acad. Radio. 19, 1241–1251 (2012).

Serrano, G. G., Washko, G. R. & Estépar, R. S. J. Deep learning for biomarker regression: application to osteoporosis and emphysema on chest CT scans, in Medical Imaging 2018: Image Processing, E. D. Angelini and B. A. Landman, Eds., SPIE, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2293455.

Singla, S. et al. Subject2Vec: generative-discriminative approach from a set of image patches to a vector. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention MICCAI 2018, Springer International Publishing, 2018, 502–510.

Gorbunova, V. et al. Early detection of emphysema progression. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention MICCAI 2010, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010, 193–200.

Staring, M. et al. Towards local estimation of emphysema progression using image registration, in SPIE Proceedings, J. P. W. Pluim and B. M. Dawant, Eds., SPIE, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.811576.

Coxson, H. O. et al. The presence and progression of emphysema in COPD as determined by CT scanning and biomarker expression: a prospective analysis from the ECLIPSE study. Lancet Respir. Med. 1, 129–136 (2013).

Tanabe, N. et al. Longitudinal study of spatially heterogeneous emphysema progression in current smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044993 (2012).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J. Y. & Kweon, I. S. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. CoRR http://arxiv.org/abs/1807.06521 (2018)

Huang, Y. et al. See more than once: Kernel-sharing atrous convolution for semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 443, 26–34 (2021).

Regan, E. A. et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 7, 32–43 (2010).

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, Global strategy for the diagnosis, mangement, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2023 report. Available at: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/GOLD-2023-ver-1.1-2Dec2022_WMV.pdf (Accessed: 12 August 2025).

JVestbo J. et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE). Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00111707 (2008).

Tsutsumi, A. et al. Characteristics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with robust progression of emphysematous change. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87724-8 (2021).

Shaker, S. B. et al. Factors influencing the decline in lung density in a Danish lung cancer screening cohort. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00207911 (2012).

Jobst, B. J. et al. Effect of smoking cessation on quantitative computed tomography in smokers at risk in a lung cancer screening population. Eur. Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-017-5030-6 (2018).

Shaker, S. B., Stavngaard, T., Laursen, L. C., Stoel, B. C. & Dirksen, A. Rapid fall in lung density following smoking cessation in COPD. COPD: J. Chronic Obstruct. Pul. Dis https://doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2010.541306 (2011).

Tian, L. et al. GradICON: approximate diffeomorphisms via gradient inverse consistency. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 18084–18094 (2023).

Zhou, R., Yang, G., Zhang, Y. & Wang, Y. Spatial transcriptomics in development and disease. Mol. biomedicine 4, 32 (2023).

Curiale, A. H. & San Jose Estepar, R. Detection of local emphysema progression using conditional CNN, in SPIE Medical Imaging (San Diego, 2024).

Castaldi, P. J. et al. Distinct quantitative computed tomography emphysema patterns are associated with physiology and function in smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 188, 1083–1090 (2013).

Mendoza, C. S. et al. Emphysema quantification in a multi-scanner HRCT cohort using local intensity distributions. 9th IEEE Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging (ISBI) 2012, 474–477 (2012).

Ramachandran, P., Zoph, B. & Le, Q. V. Searching for activation functions, arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.05941 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1R01HL149877 and Alpha-1 Foundation grant 1037165.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: A.H.C. and R.S.J. E.A. cquisition, analysis, or interpretation: A.H.C., C.P, R.S.J.E, A.D, G.W. and R.S.J.E. Drafting of the manuscript: A.H.C. and R.S.J.E. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: A.H.C., C.P., R.S.J.E., A.D., G.W. and R.S.J.E. Statistical analysis: A.H.C. and R.S.J.E. Read and approved the manuscript: A.H.C., C.P., R.S.J.E., A.D., G.W. and R.S.J.E. A.H.C. and R.S.J.E. had full access to data included in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Curiale, A.H., Pistenmaa, C., San José Estépar, R. et al. Emphysema progression risk in COPD using a localized foundational model of density evolution. npj Digit. Med. 8, 556 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01917-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01917-3